Abstract

Background:

Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (HDP) represent a group of conditions associated with high blood pressure during pregnancy. It is an important cause of feto-maternal morbidity and mortality, particularly in developing countries. The aims of the study were to find the prevalence of hypertensive disorders and its associated risk factors among women attending the antenatal clinic of Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital,(UDUTH) Sokoto.

Materials and Methods:

A longitudinal study of 216 consecutively recruited women that were less than 20 weeks pregnant at booking was carried out. Blood pressure was measured for each woman at booking and at subsequent visits. Urinalysis was done at booking and whenever blood pressure was elevated. Patients were followed-up to delivery and 6 weeks postpartum. Data entry and analysis was done using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) statistical package.

Results:

The prevalence of HDP in the study was 17% while preeclampsia was 6%. Previous history of preeclampsia (P < 0.001; Relative risk (RR) 4.2; conficence interval (CI) 2.144-6.812), multiple gestation (P < 0.03; RR 3.8; CI 1.037-6.235), gestational diabetes (P < 0.02; RR 4.8; CI 1.910-6.751) and obesity (P < 0.002; RR 2.7; CI 1.373-5.511) were the significant risk factors in the development of HDP among the study population.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of HDP in the study group is high. Therefore, paying attention to the risk factors will ensure early detection and prevention of the progression of the disease and its sequelae.

Keywords: Hypertension, pre-eclampsia, pregnancy, prevalence, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Hypertensive disorders represent one of the most common problems of pregnancy and lead to increased maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. Hypertension may be pre-existent, may be induced by the pregnancy or both types may co-occur, and their influence on the outcome of the pregnancy is different depending on the type of disorder concerned. Further, hypertension in the presence of proteinuria indicates more severe maternal and foetal consequences.1,2

The causes of pregnancy-induced hypertension and the risk factors associated with it are largely unknown. Apart from nulliparity and previous history of preeclampsia in multiparas, few other risks are universally agreed upon.3

There are many attributes that have been reported to be related to preeclampsia: maternal age, familial aggregation, race, smoking, socioeconomic level, diet, season and climate, quite apart from the geographical area.4

The incidence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy varies in the range of 1-35% around the world.3 There are several causes of the differences, including variations in the definitions of the disorders and the methods of diagnosis. Also, many reports are based on hospital populations, which may be influenced by the special nature of the health services and do not reflect the situation in the whole population of a defined geographical area. In Nigeria, it is estimated that 5-10% of pregnancies are complicated by hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (HDP)5,6,7,8,9,10,11 and it results in more admissions in the antenatal period than any other disorder.7

Hypertensive disorder in pregnancy is one of the leading cause of maternal mortality in this centre.8

The objectives of this work were to determine the prevalence of HDP and the risk factor associated with the development of the disease.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This was a longitudinal study where 216 women were recruited. Pregnant women who were less than 20 weeks of gestation at booking in antenatal care clinic at Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital Sokoto were recruited. A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was filled for all the participants, to obtain information on age, educational status, parity, occupation, ethnic group, gestational age, maternal smoking, body mass index (BMI) and cell phone number. Urinalysis for protein and glucose was done at booking and at subsequent visits when blood pressure was found to be elevated, i.e., 140/80 mmHg. The blood pressure was measured in a sitting position with sphygmomanometer after at least 10 minutes of rest. Systolic blood pressure was recorded at the appearance of K1 sound, and diastolic blood pressure at the disappearance of K5. All pregnant women were followed-up to delivery and 6 weeks post partum. Information on the age, parity, time of diagnosis, mode of delivery and foetal outcome were recorded. There were some patients who were recruited for the study also developed gestational diabetes or were known diabetic or hypertensive. The data analysis was done using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) statistical package. The chi-square and fisher's exact tests, t test and analysis of variance were used to determine level of statistical significance set at P value equal to or less than 0.05. The relative risk and 95% confidence interval were also determined.

Study period was from March 2011 to December 2011. Sample size was determined using the the prevalence rate of HDP 11% from Ibadan.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in verbal form. The exclusion criterion was those who were more than 20 weeks of gestation at booking. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital (UDUTH) Ethical and Research Committee.

RESULTS

Of the 216 antenatal women that were recruited during the antenatal period and longitudinally followed-up till 6 weeks postpartum, 36 developed HDP giving a prevalence rate of 17% while 180 (83%) were normotensive. [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Distribution of the study groups

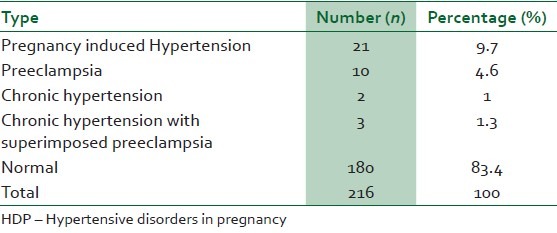

Preeclampsia was recorded in 13 patients (6%), i.e., Preeclampsia and chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution based on type of HDP

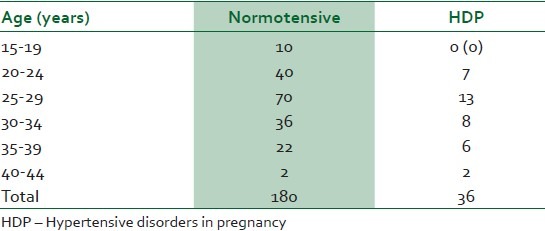

It is noteworthy that no woman in the age range of 15-19 years developed HDP [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of the age of normotensive women and HDP patients

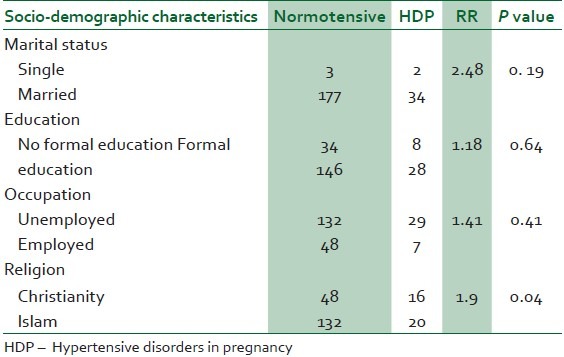

Marital status, level of education, occupation, tribe and religion showed relative risk greater than 1; however, they were not found to be the statistically significant risk factors in the development of hypertensive disorder in pregnancy [Table 3].

Table 3.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the normotensive women and HDP patients

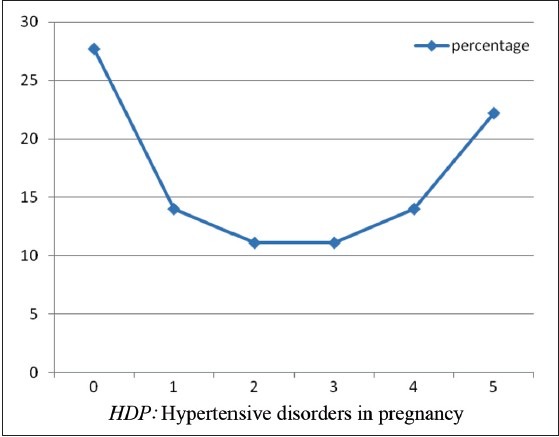

Among the study group, nulliparous and grandmultiparous women had the highest incidence of HDP of 27.7% and 22.2%, respectively [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Trend of HDP with parity

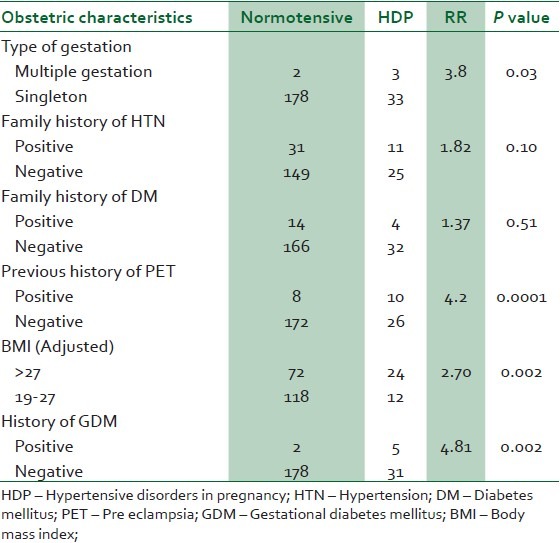

Multiple pregnancy, previous history of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes and BMI greater than 27 were found to be the significant risk factors in the development of hypertension during pregnancy [Table 4].

Table 4.

Obstetrics characteristics of the study group

In this study, women with multiple pregnancy and gestational diabetes had a four- and fivefold risk of developing HDP, respectively. Also, women with previous history of preeclampsia had a fourfold risk of developing hypertensive disorder in pregnancy in their subsequent pregnancy [Table 4].

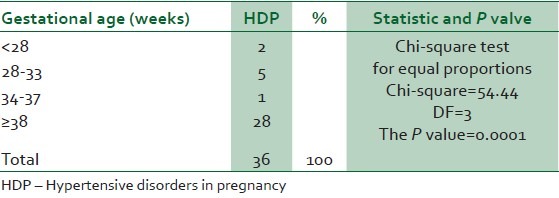

Eighty percent of those that developed HDP occurred at term. This was found to be statistically significant. All the patient delivered at term from 37 weeks and above. [Table 5].

Table 5.

Relationship between gestational age and the development of HDP

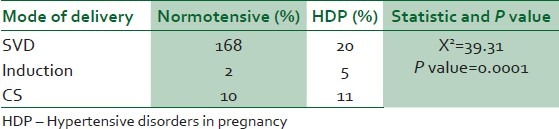

Women with hypertensive disorder were more likely to have a caesarean section and induction/SVD than normotensive women. This relationship was statistically significant with P value of 0.0001. [Table 6].

Table 6.

Mode of delivery

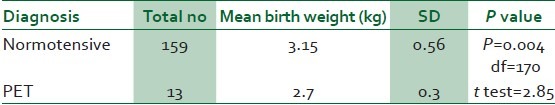

The mean birth weight of babies of the normotensive (3.15 kg) was compared with mean birth weight of those whose mothers had PET (2.7 kg). This was found to be statistically significant with P value = 0.004 [Table 7].

Table 7.

Comparison of birth weight among normotensive with PET

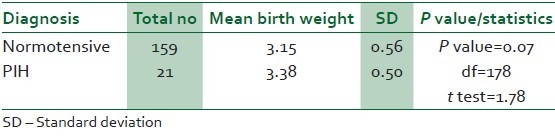

The mean birth weight of PIH (3.38 kg) was compared with normotensive (3.15 kg). This was not found to be statistically significant with P value 0.075 [Table 8].

Table 8.

Comparison of birth weight among normotensive with PIH

DISCUSSION

This longitudinal study provided an opportunity to study maternal background factors such as socio-demographic, obstetric and familial factors, which were known at booking and their associations with the occurrence of the hypertensive disorders in pregnancy.

The prevalence of the hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (17 %) found in this study was similar to 21.6% and 17.2% that had been reported from south-eastern Nigeria and Finland, respectively.12,13 However, it was greater than 10% and 11.6% that had been reported from Ibadan and Benin City.11,14 The factor that may be responsible for the high prevalence of hypertensive disorder in our hospital could be due to the fact that it is a referral centre for the catchment areas.

In this study, the prevalence of preeclampsia and chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia was 6%. This agrees with the 5-10% prevalence of other studies carried out in Lagos, Ibadan, Calabar, Kano and other parts of the world.5,6,7,8,9,10

The age and parity distribution of the cases in this study were also similar to those in other reports.6,8,15

The prevalence of HDP declined with parity, reaching its lowest in women who were para 2 and 3 and then increased markedly after Para 4. Nulliparous and grandmultiparous women had been reported in previous studies to be at increased risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, especially PIH and PET.5,6,7,8 This was also the finding in this study. This could be because increasing maternal age and grandmultiparity are associated with medical disorders of pregnancy, especially the risk of essential hypertension. Also, grandmultiparity and increasing maternal age are usually common among the low socioeconomic class and this could be because among them large family size is the norm. This coupled with poor acceptance and utilisation of modern family planning methods, unemployment and usually low literacy level16 may be confounding factors in the development of HDP in this group of women.

In this study, being unmarried emerged as a risk factor and predictor of HDP. Although marital status is rarely reported as a risk factor in the literature, a possible explanation in a resource poor country like ours could be due to anxiety about the financial burden of single parenting in our environment which lacks any form of child welfare support. Moreover the stigma of having a child outside wedlock is a potential source of concern and anxiety. In addition, recent studies had highlighted immunological intercourse as the prevention of this maternal-foetal conflict called pregnancy induced hypertension.17 There is an association of pregnancy-induced hypertension with duration of sexual co-habitation before the first conception. Male ejaculate is said to help protect a woman if she has been repeatedly exposed to it.17 In our environment, being a single mother could be by chance, viz, a single intercourse. Thus, the single mother, because of short duration of the relationship may develop HDP.

A positive family history of hypertension was found to be a significant risk factor for developing HDP in this study. Women whose mothers suffered from PIH were three times more likely to develop PIH than other women.18,19

Multiple pregnancy, gestational diabetes and previous history of preeclampsia were significant risk factors for developing HDP in this study. This findings were same as in other studies.5,7,20,21 These are consistent with the hypothesis that immune maladaptation might play a role in triggering the development of HDP.17

It was also found that BMI >27 kg/m2 was associated significantly with the risk of the development of HDP. It has been observed that obese women were more likely to have increased levels of serum triglycerides, very low-density lipoproteins and formation of small, dense low-density lipoprotein particles w19x. Such lipid alterations have been suggested to promote oxidative stress, caused by either ischaemia-reperfusion mechanism or activated neutrophils and lead to endothelial cell dysfunction.18

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy were noted to be associated with high obstetric intervention rates in this study. The induction of labour/caesarean section rates among the women that developed HDP in this study were 5 times higher than that of normotensive women (36% vs. 8%). Early intervention and higher caesarean section rates have been reported from other studies and this supports the high incidence of induction and caesarean delivery.6,22

It is noteworthy that none of the women who developed HDP in this study progressed to eclampsia. This must be due to the close monitoring and early intervention instituted. This proves that community-based measures that promote earlier and wider utilisation of antenatal care services will lead to earlier presentation, diagnosis and intervention in cases of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. This will in turn go a long way in reducing the current high maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with the disease.

The average birth weight of the babies born to normotensive mothers was 3.15 kg while that for preeclamptic and chronic hypertensive mothers was 2.7 kg. Women who had preeclampsia delivered lighter babies than the normotensive mothers, and this was statistically significant and agrees with previous studies. On the contrary, those women that developed PIH had babies whose average birth weight were similar to those of normotensive women (3.58 kg vs. 3.14 kg). The explanation could be that in this study most of the women develop their disease at term when the foetus had already achieved its growth potential. This is also supported by the study that was done in Ghana.22

Only few women developed preeclampsia at an early gestational age (<28 weeks) and their babies were ≤2.5 kg. The presence of proteinuria in association with hypertension is known to increase the risk of intrauterine growth restriction and prematurity, probably this could be one of the reasons for the low birth weight in the preeclamptic patients.

Twenty one of the patients had their babies elsewhere hence their intrapartum and 1 hour postpartum blood pressure could not be monitored. However, they were traced and had their blood pressure taken within one week of delivery and all were within the normal range. This was one limitation that was encountered in this study.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of HDP found in this study was 17%. There is need to increase awareness among medical and paramedical personnel on the need for early referral of women with previous history of preeclampsia, multiple gestation, gestational diabetes and obesity for specialist care as they have a higher risk of developing HDP. Single mothers should be given special consideration and provided with social and economic welfare as these interventions may reduce their risk of developing HDP.

It might be worthwhile to further study those that developed PIH and PET so as to determine the proportion that may later develop chronic hypertension.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Dr. A Singh who assisted me in the statistical analysis of the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sibai BM, Abdella TN, Anderson GD. Pregnancy outcome in 211 patients with mild chronic hypertension. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;61:571–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gleicher N, Boler LR, Jr, Norusis M, Del Grando A. Hypertensive diseases of pregnancy and parity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:1044–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90747-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesley LC. Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. New York: Appleton-Century- Crofts; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies AM, Dunlop W. Hypertension in pregnancy. In: Barron SL, Thomson AM, editors. Obstetrical Epidemiology. London: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 167–208. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emuveyan E. Pregnancy induced hypertension. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;12:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itam IH, Ekabule JE. A review of pregnancy outcome in women with eclampsia at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;18:66–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers JE, Baxer PN. Hypertension diseases and eclampsia. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;14:119–25. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200204000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Audu LR, Ekele BA. A ten-year review of maternal mortality in Sokoto, northern Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2002;21:74–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omole-Ohonsi A, Shehu I. Value of antenatal care in the management of pre-eclampsia/eclampsia-light of healing. J Islam Med Assoc. 2001;1:36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayman R. Hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;14:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salako BL, Aimakhu CO, Odukogbe AA, Olayemi O, Adedapo KS. A review of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2004;33:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National study on essential obstetric care facilities in Nigeria. Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria. 2003:37. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartikainen AL, Riita HA, Paula TR. A cohort study of epidemiological associations and outcomes of pregnancies with hypertensive disorders. Hypertens Pregnancy. 1998;17:31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebeigbe PN, Iberase GO, Aziken ME. Hypertensive disorder in pregnancy: Experience with 442 recent consecutive cases in Benin City, Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2007;48:94–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olusanya BO, Solanke OA. Perinatal outcomes associated maternal hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in a developing country. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2012;31:120–30. doi: 10.3109/10641955.2010.525280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okonofua FE, Abejide A, Makanjuola RA. Maternal mortality in Ile-Ife, Nigeria: A study of risk factors. Stud Fam Plann. 1992;23:319–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zusterzeel PL, te Morsche R, Raijmakers MTM, Roes EM, Peters WH, Steegers EA. Paternal contribution to the risk for pre-eclampsia. J Med Genet. 2002;39:44–5. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laresgoiti-Servitje E, Gomez-Lopez N, Olson DM. An immunological insight into the origins of pre-eclampsia. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:510–24. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skjaerven R, Vatten LJ, Wilcox AJ, Rønning T, Irgens LM, Lie RT. Recurrence of preeclampsia across generations: Exploring foetal and maternal genetic components in a population based cohort. BMJ. 2005;331:877. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38555.462685.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odum CU. Multiple pregnancy. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;12:12–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Obed S, Aniteye P. Pregnancy following eclampsia: A longitudinal study at korle- bu teaching hospital. Ghana Med J. 2007;14:139–43. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v41i3.55282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Obed SA, Aniteye P. Birth weight and ponderal index in pre-eclampsia: A comparative study. Ghana Med J. 2006;40:8–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]