Abstract

Renal cystic diseases are a leading cause of renal failure. Mutations associated with renal cystic diseases reside in genes encoding proteins that localize to primary cilia. These cystoproteins can disrupt ciliary structure or cilia-mediated signaling, although molecular mechanisms connecting cilia function to renal cystogenesis remain unclear. The ciliary gene, Thm1(Ttc21b), negatively regulates Hedgehog signaling and is most commonly mutated in ciliopathies. We report that loss of murine Thm1 causes cystic kidney disease, with persistent proliferation of renal cells, elevated cAMP levels, and enhanced expression of Hedgehog signaling genes. Notably, the cAMP-mediated cystogenic potential of Thm1-null kidney explants was reduced by genetically deleting Gli2, a major transcriptional activator of the Hedgehog pathway, or by culturing with small molecule Hedgehog inhibitors. These Hedgehog inhibitors acted independently of protein kinase A and Wnt inhibitors. Furthermore, simultaneous deletion of Gli2 attenuated the renal cystic disease associated with deletion of Thm1. Finally, transcripts of Hedgehog target genes increased in cystic kidneys of two other orthologous mouse mutants, jck and Pkd1, and Hedgehog inhibitors reduced cystogenesis in jck and Pkd1 cultured kidneys. Thus, enhanced Hedgehog activity may have a general role in renal cystogenesis and thereby present a novel therapeutic target.

Cystic kidney disease represents a wide disease spectrum characterized by fluid-filled cysts, which destroy surrounding renal parenchyma. The spectrum affects adults in the most common life-threatening hereditary disease, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), as well as children in the form of autosomal recessive PKD (reviewed by Torres and Harris1). Infantile or juvenile cystic kidney disease is also manifested in disease syndromes caused by mutation of ciliary genes that are collectively termed ciliopathies. These include nephronophthisis, Bardet-Biedl syndrome, Meckel-Gruber syndrome, Jeune syndrome, and Joubert syndrome.2 PKD genes encode proteins that also localize to primary cilia.3 Together, these findings have led to the proposition that perturbed cilia function may be a unifying etiologic basis for cystic kidney disease.

Primary cilia project from the apical surface of renal tubular epithelial cells and have been proposed to function as mechanosensors, bending in response to urine flow and initiating signaling cascades.4 Intraflagellar transport (IFT), the bidirectional transport of multiprotein complexes along the ciliary microtubule-based core, builds and maintains cilia and is integral to signaling.5 Anterograde IFT delivers proteins to the ciliary distal tip and is mediated largely by the kinesin motor and IFT complex B proteins, while retrograde IFT returns proteins to the base and is mediated by the cytoplasmic dynein-2 motor and IFT complex A proteins.

In mice, loss of IFT proteins causes cilia structural defects, which affect regulation of Hh signaling,6 a pathway fundamental to proper development and tissue maintenance.7 Three mammalian Hh ligands—Sonic Hh, Indian Hh, and Desert Hh—can initiate signaling upon binding the 12-transmembrane receptor, Patched, in the cilium. Upon being bound, Patched exits the cilium, enabling ciliary translocation of the seven-transmembrane signal transducer, Smoothened (SMO).8,9 Within the cilium, SMO is activated, which culminates in activation of full-length glioblastoma (GLI1, GLI2, GLI3) transcription factors. In most tissues, GLI2 acts as the primary transcriptional activator (reviewed by Eggenschwiler and Anderson10), although in certain tissues, GLI3 activator (GLI3A) or GLI3 repressor (GLI3R), which is formed by cleavage of the full-length GLI3 protein, plays a predominant role because of redundancy and/or tissue specificity of the GLI proteins.11,12 Nonetheless, the balance between activity of GLI activators and GLI3 repressor determines level of Hh signaling output within a cell.10,13

Despite the connection between primary cilia and Hh signaling, a role for Hh signaling in cystic kidney disease has not been studied extensively. Yet the few studies implicating Hh signaling in cystic kidney disease are quite compelling. In the first, 50% of Shh-null mouse embryos formed a single, ectopic, dysplastic kidney.14 In the second, loss of the transcription factor, Glis2, a member of the Kruppel-like C2H2 zinc finger protein subfamily, which includes the GLI proteins, resulted in nephronophthisis in humans and mice.15 Expression profiling of Glis2−/− kidneys revealed an upregulation of Gli1, a direct target of the pathway, suggesting upregulated Hh signaling. Finally, a study examining the effects of corticosteroid overexposure on metanephric development found that adding hydrocortisone to a metanephros organ culture unexpectedly caused renal cysts as well as upregulated Ihh transcripts.16 Addition of Hh inhibitor, cyclopamine, reduced hydrocortisone-induced cysts without affecting organ growth, implicating increased Hh signaling in this mechanism of cystogenesis.

We identified an N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea–derived, developmental mouse mutant, alien (aln), as the first IFT complex A mammalian mutant.17 This defect impaired retrograde IFT, causing accumulation of proteins in bulb-like structures at the ciliary distal tips and increased Hh signaling mediated by enhanced GLI2 and GLI3 activator transcriptional activities resulting in limb and neural tube patterning defects. The genetic lesion in alien results in the absence of Thm1 (TPR-containing Hh modulator 1; also termed Ttc21b), an ortholog of Chlamydomonas complex A protein, IFT139. Another IFT complex A mouse mutant, sob/IFT122, also exhibits upregulated Hh signaling18; this contrasts with most IFT and cilia mutants, which lose the capacity to respond to the Hh signal (reviewed by Eggenschwiler and Anderson10). Deficiency of murine IFT complex B genes, including a hypomorphic allele of Ift8819 and renal-specific ablation of Ift20 or of Kif3a, which encodes a kinesin subunit, causes renal cysts.20–22 Because loss of complex B proteins results in loss of Hh response, this may account in part for why Hh signaling has not been studied extensively in cystic kidney disease.

One report has characterized the role of IFT complex A proteins in renal function; kidney-specific deletion of Ift140 caused renal cysts.23 However, THM1 mutations have been reported in 5% of patients with ciliopathies, rendering THM1 the most commonly mutated gene in ciliopathies24 and thereby implicating this gene in renal disease. We investigated the consequences of Thm1 deletion in renal cystogenesis using the Thm1aln/aln developmental mutant and a newly developed Thm1 conditional knockout mouse. We further examined a direct role of Hh signaling in this and two other orthologous cystic kidney disease mouse mutants, in part by examining effects of Hh inhibitors on cystogenic potential of mutant kidneys cultured with cAMP, an assay proposed as a general model of cystic kidney disease25 and useful for testing efficacy of potential pharmaceutical therapies.26

Results

Loss of THM1 Causes Renal Cysts

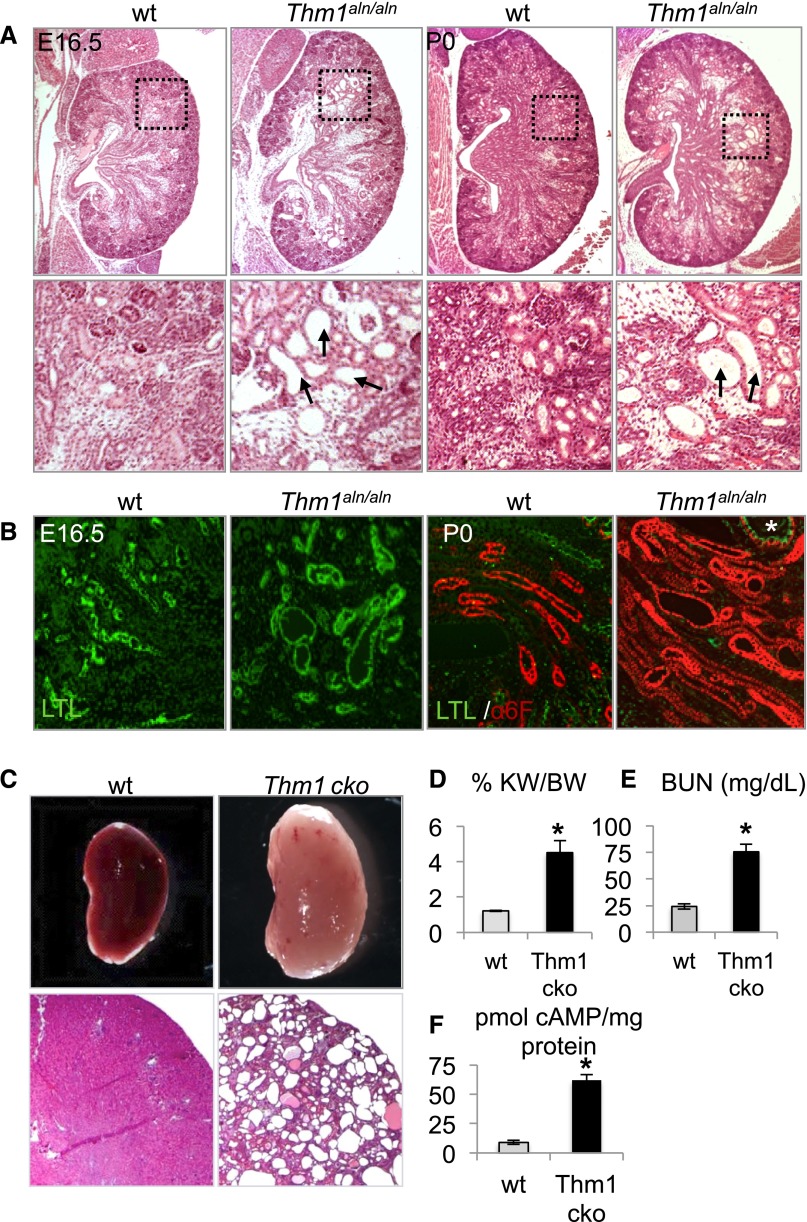

To explore a role for Thm1 deletion in renal cystogenesis, we examined the kidneys in Thm1aln/aln mice during late embryogenesis. At E16.5 and P0, the last day on which Thm1aln/aln mutants survive, histologic analysis of the kidneys revealed cystic dilations of glomeruli and surrounding tubules (Figure 1A). Coimmunostaining of kidney sections for Lotus tetragonolobus lectin (LTL) and Na+K+ ATPase (α6F) demonstrated that Thm1aln/aln renal tubular dilations originate in proximal tubules and ascending loops of Henle (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Loss of THM1 causes renal cysts. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin images of E16.5 and P0 wt and Thm1aln/aln kidneys. Black dotted squares on first-row panels are shown at higher magnification than in the second-row panels. Arrows point to dilated tubules in Thm1aln/aln kidneys. (B) Marker analysis of wt and Thm1aln/aln nephron segments. Kidney sections were co-immunostained for fluorescein-conjugated LTL (green) and for Na+K+ adenosine triphosphatase (red). (C) Whole-mount and histologic sections of 6-week-old wt and Thm1 cko kidneys. (D) %KW/BW, (E) BUN levels, and (F) cAMP levels of 6-week-old wt and Thm1 cko kidneys. Bars represent mean±SEM of 4 wt mice and 3 Thm1 cko mice. *P<0.05.

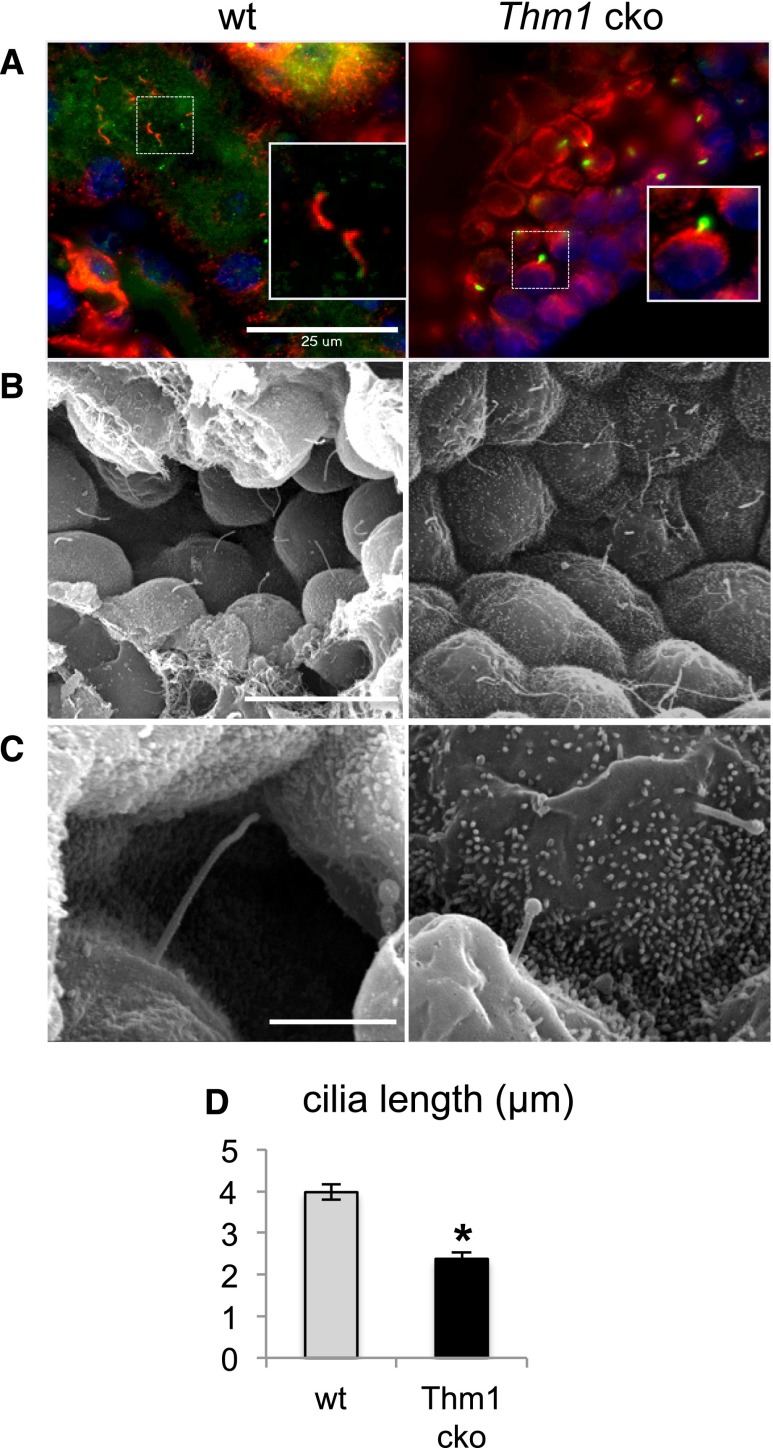

Because Thm1aln/aln mutants die shortly after birth, we generated Thm1 conditional knockout (cko) mice to analyze the role of THM1 in maintaining renal tubular integrity. Ubiquitous deletion of Thm1 at E17.5 resulted in cystic kidney disease in 6-week-old Thm1 cko mice (Figure 1C), with elevated ratios of percentage kidney weight to body weight (%KW/BW) and BUN levels (Figure 1, D and E). Levels of cAMP were also higher in Thm1 cko cystic kidneys (Figure 1F), similar to other mouse models, such as the cpk autosomal recessive PKD model and the Pkd1 orthologous ADPKD model. Thm1 cko renal cysts labeled positively for LTL, Tamms–Horsfall protein (THP), and Dolichus biflorus agglutinin (DBA), indicating that cysts originate from proximal tubules, loops of Henle, and collecting ducts, respectively (Figure 2, B–D). In kidneys of Thm1 cko mice, primary cilia were stunted and showed accumulation of IFT88 protein in bulb-like structures at the distal tips (Figure 3, A–C), characteristic of the IFT complex A mutant phenotype. Scanning electron microscopy revealed that in collecting ducts, Thm1 cko primary cilia length is 60% that of wild-type (wt) (Figure 3D).

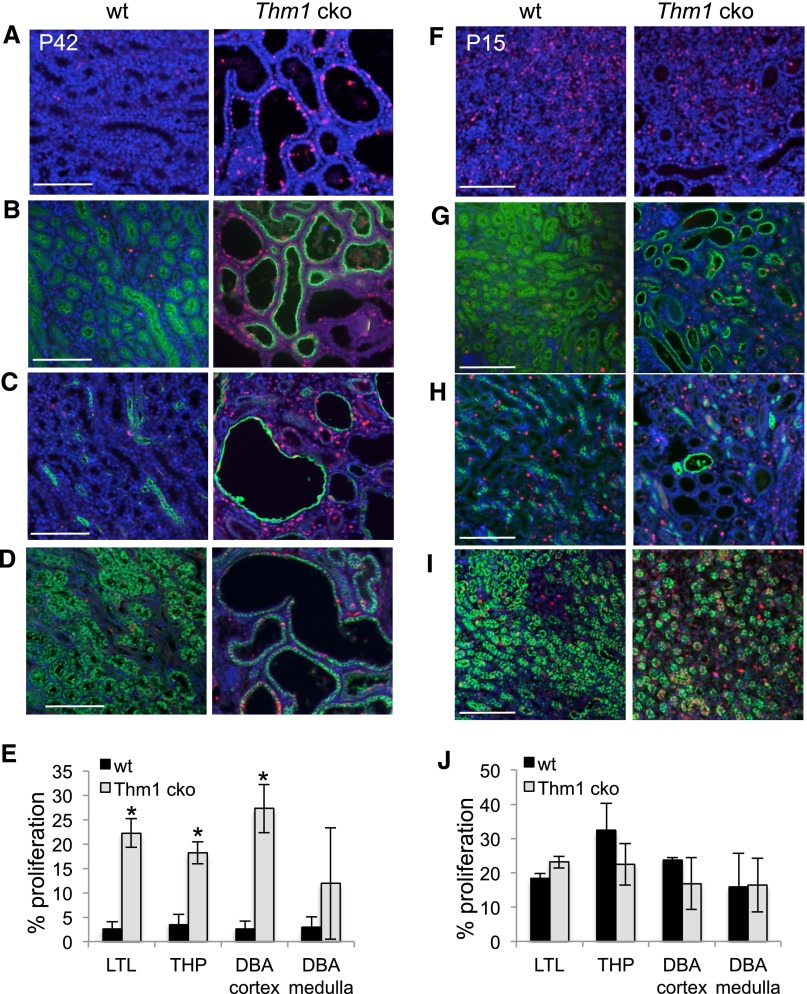

Figure 2.

Proliferation is increased in Thm1 cko cystic kidneys. (A) Immunostaining of 6-week-old wt and Thm1 cko kidneys for PCNA alone or in combination with (B) LTL, (C) THP, or (D) DBA. (E) Proliferation rates of 6-week-old wt and Thm1 cko kidneys. Number of PCNA+ cells was divided over number of DAPI cells for a particular tubule. (F) Immunostaining of P15 wt and Thm1 cko kidneys for PCNA alone or in combination with (G) LTL, (H) THP, or (I) DBA. (J) Proliferation rates of P15 wt and Thm1 cko kidneys. All scale bars represent 500 μm. n=3 wt; n=3 Thm1 cko for each time point.

Figure 3.

Thm1 cko renal primary cilia show IFT complex A mutant phenotype. (A) Immunostaining of wt and Thm1 cko renal primary cilia for acetylated α-tubulin (red) and IFT88 (green). Scale bar represents 25 μm. (B) Scanning electron micrographs of wt and Thm1 cko collecting ducts (original magnification, ×2000). Scale bar represents 15 μm. (C) Scanning electron micrographs of wt and Thm1 cko collecting duct primary cilia (original magnification, ×15,000). Scale bar represents 3 μm. (D) Lengths of wt and Thm1 cko collecting duct primary cilia. Bars represent mean±SEM of n=23 cilia from three wt mice and n=25 cilia from two Thm1 cko mice. *P<5×10−8.

A cellular hallmark of PKD is increased proliferation of cyst-lining epithelial cells. Using proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) immunostaining to evaluate proliferation, we observed markedly higher levels of PCNA+ cells in Thm1 cko cystic kidneys (Figure 2A). A similar percentage of PCNA+ cells was observed across Thm1 cko LTL, THP, and cortical DBA–labeled tubules (Figure 2, B–E), suggesting that increased proliferation did not correlate with a specific renal tubule.

To determine when cystic kidney disease initiates, we examined Thm1 cko kidneys at earlier time points and observed that by P15, dilations of proximal tubules and loops of Henle in the cortex were present (Figure 2, G and H, Supplemental Figure 1). Because proliferation has been proposed as an initiating factor in renal cystogenesis, we immunostained P15 and P20 kidneys for PCNA. At P15, the percentage of PCNA+ cells was similar between wt and Thm1 cko kidneys (Figure 2J). From P15 to P20, PCNA+ cells were markedly reduced in wt renal medulla, but not in Thm1 cko medulla (Supplemental Figure 2). These data suggest that the ciliary defect may delay maturation of the kidney, prolonging the kidney in a developing state.

The developmental state of a kidney has been proposed to have a significant role in predisposing to cystogenesis because loss of cystoproteins before P12–P14 results in severe cystic kidney disease, while loss of cystoproteins after this window causes very mild cystic kidney disease evident only after 6 months.27,28 To determine whether THM1 loss is similarly sensitive to the developmental state, we ablated Thm1 at 5 weeks of age. As with all other cystoproteins reported, Thm1 deletion at a mature stage did not result in cysts after 3 months (Supplemental Figure 3).

Genetic and Pharmacologic Inhibition of Hh Signaling Reduces Renal Cystogenic Potential of Thm1aln/aln Cultured Kidneys

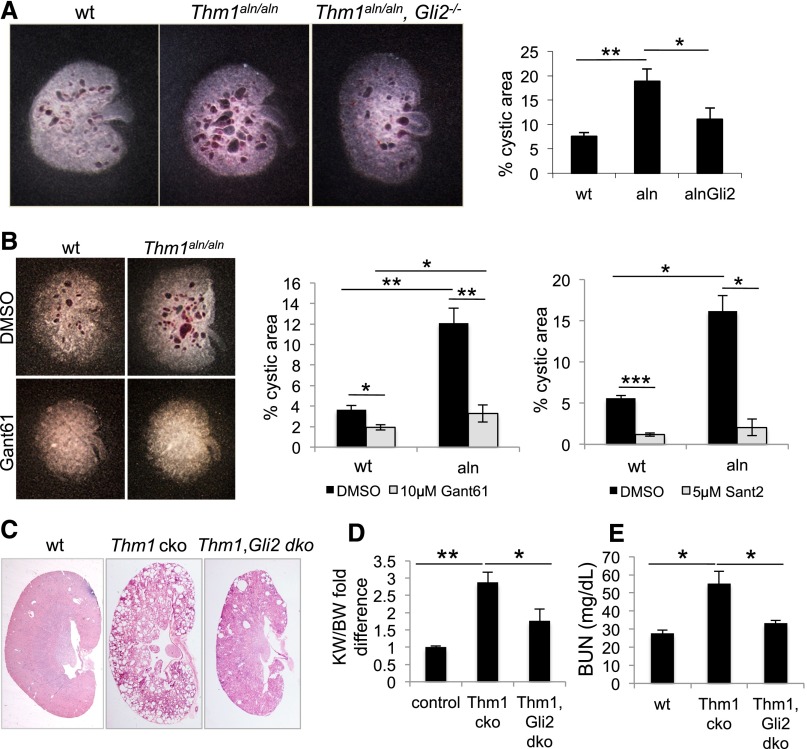

Previously, we observed that the floor plate of the Thm1aln/aln neural tube is dorsally expanded, reflecting increased GLI2 activity.17 Consistent with this, Gli2 deletion in Thm1aln/aln embryos reversed the effect of the aln mutation in the floor plate, establishing THM1 as a negative regulator of Hh signaling. We queried whether Gli2 deficiency could similarly rescue the Thm1aln/aln kidney phenotype and examined Thm1, Gli2 genetic interaction using an embryonic kidney culture assay.25 E13.5 wt, Thm1aln/aln and Thm1aln/aln,Gli2−/− kidneys were cultured in the presence of cystogenic reagent, 8-Br-cAMP, for 4 days. Thm1aln/aln kidneys showed a 3-fold greater cystogenic potential than wt (Figure 4A), consistent with a role for THM1 loss in renal cystogenesis. Importantly, Thm1aln/aln,Gli2−/− kidneys showed a 2-fold lower cystogenic potential than Thm1aln/aln kidneys, suggesting that increased GLI2 activity mediates Thm1aln/aln renal cystogenesis.

Figure 4.

Genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of Hh signaling reduces cystogenesis in Thm1aln/aln kidney explants and Thm1 cko kidneys. (A) E13.5 wt, Thm1aln/aln, and Thm1aln/aln, Gli2−/− kidneys were incubated with 100 μM of 8-bromo-cAMP for 4 days. Quantitative assessment of kidney images showed a 3-fold greater cystogenic potential in Thm1aln/aln kidneys than wt and a 2-fold decrease in cystogenic potential of Thm1aln/aln, Gli2−/− kidneys relative to Thm1aln/aln kidneys. Bars represent mean±SEM of 4 wt, 6 Thm1aln/aln, and 8 Thm1aln/aln, Gli2−/− kidneys from two experiments. (B) E13.5 wt and Thm1aln/aln kidneys were cultured in presence of 100 μM 8-bromo-cAMP, in combination with 10 μM Gant61, 5 μM Sant2, or control DMSO for 4 days. Graphs represent quantitative assessment of kidney images following 4-day culture. Gant61 or Sant2 reduces cystogenic potential of both normal and aln kidneys. Bars represent mean±SEM of 11 control and 7 Thm1aln/aln kidneys from 3 experiments for Gant61, and 9 control and 3 Thm1aln/aln kidneys from 3 experiments for Sant2. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of kidney sections of 6-week-old wt, Thm1 cko, and Thm1;Gli2 double cko mice. (D) KW/BW fold difference of 24 wt, 11 Thm1 cko, and 7 Thm1;Gli2 double cko mice. (E) BUN of 8 wt, 6 Thm1 cko, and 3 Thm1;Gli2 double cko mice. *P<0.05; **P<0.005; ***P<0.0005.

To determine the contribution of GLI2 and GLI3 proteins to Thm1aln/aln renal cystogenesis, we assayed protein extracts of E13.5 Thm1aln/aln cultured kidneys and E18.5 Thm1aln/aln kidneys for GLI1, GLI2, and GLI3. However, examination of these whole kidney extracts did not show obvious differences in GLI levels between wt and Thm1aln/aln kidneys (Supplemental Figure 4).

To pharmacologically replicate the Thm1, Gli2 genetic interaction, we assessed the effects of small molecule GLI antagonist, Gant61, on wt and Thm1aln/aln kidneys cultured in the presence of 8-Br-cAMP. At a concentration of 10 μM, Gant61 prevented tubular dilations in Thm1aln/aln cultured kidneys (Figure 4B). To further explore the role of Hh signaling in renal cystogenesis, we also examined the effect of the small molecule SMO antagonist, Sant2. Similarly to Gant61, 5 μM Sant2 prevented cysts in mutant kidneys cultured with 8-Br-cAMP (Figure 4B). Thus, Hh inhibitors acting at two different steps in the signaling pathway could counteract the effects of cAMP and abrogate cyst formation.

To assess a functional role for GLI2 in renal cystogenesis in vivo, we deleted Thm1 and Gli2 simultaneously at E17.5. At 6 weeks of age, Thm1; Gli2 double cko mice showed milder cystic kidney disease than did Thm1 cko mice (Figure 4C), with reduced KW/BW ratios (Figure 4D) and BUN levels (Figure 4E), supporting a role for increased GLI2 activity in Thm1 cko renal cystogenesis in vivo.

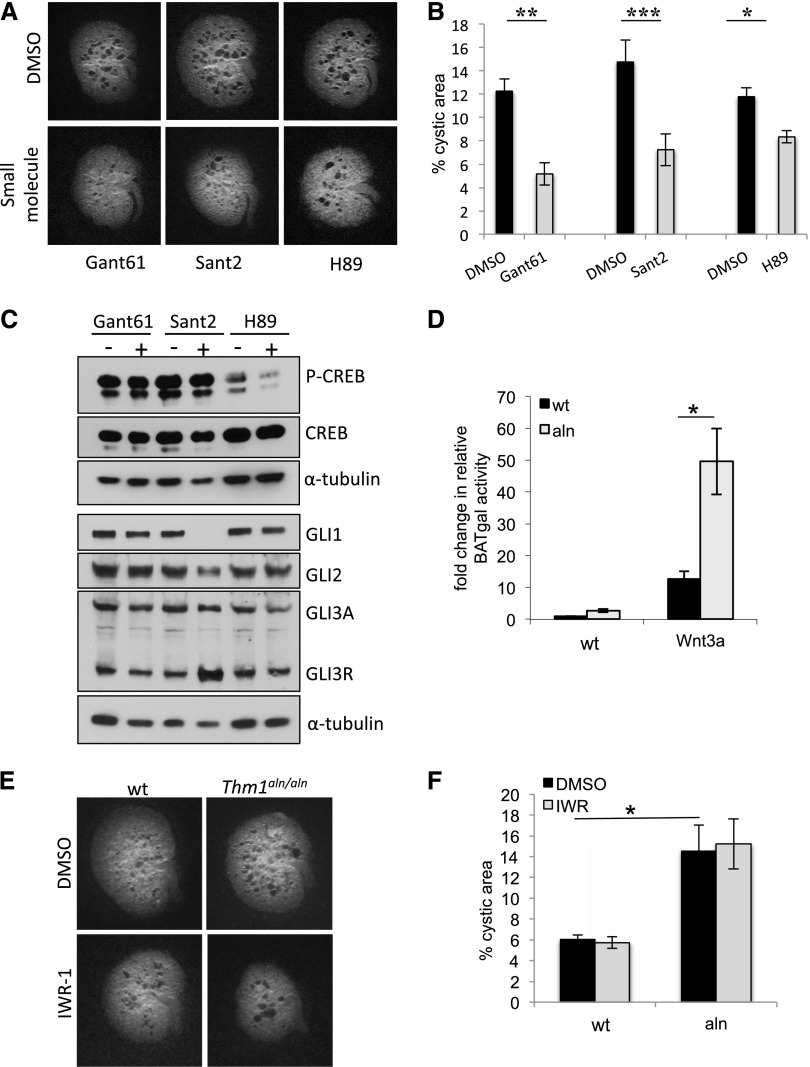

Small Molecule Hh Inhibitors Do Not Act Through Protein Kinase A or Wnt Signaling to Reduce Cystogenic Potential

A role for the Hh pathway in cAMP signaling leading to cyst formation is unknown. Levels of cAMP are elevated in PKD-affected kidneys,29–31 which leads to activation of protein kinase A (PKA). This in turn phosphorylates and activates cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), driving Cl− ions out into the lumen, which is accompanied by fluid secretion, a major cellular abnormality in PKD. Accordingly, addition of the PKA inhibitor H89 or of the CFTR inhibitor 172 to kidneys cultured with 8-Br-cAMP abrogated cyst formation.25 To determine whether the effect of Hh inhibitors was mediated through this pathway, we examined the effect of the PKA inhibitor H89 relative to Gant61 and Sant2 on wt CD1 kidneys cultured in the presence of 8-Br-cAMP. We found that the Hh inhibitors prevented cysts to an extent similar to that of H89 (Figure 5, A and B). To examine the effect of the Hh inhibitors on PKA activity, we analyzed treated kidneys for levels of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and phospho-CREB (P-CREB), a target of PKA. As expected, we found high levels of P-CREB in kidneys cultured with cAMP, while P-CREB levels were dramatically reduced in extracts of kidneys cultured with both cAMP and H89. In contrast, P-CREB levels were not reduced in kidneys treated with Gant61 or Sant2 (Figure 5C). Thus these data suggest that, despite reduced cyst formation, Gant61- and Sant2-treated kidneys have high levels of PKA activity.

Figure 5.

Small molecule Hh inhibitors act independently of PKA and Wnt inhibitors to reduce cystogenic potential of kidney explants. (A) E13.5 CD1 kidneys were cultured in the presence of 100 μM 8-bromo-cAMP, in combination with DMSO, 10 μM Gant61, 5 μM Sant2, or 10 μM of PKA inhibitor H89 for 4 days. Untreated contralateral kidneys were used as control. (B) Quantitative assessment of kidney images following 4-day culture. Bars represent mean±SEM; n=6 kidneys for each small molecule. (C) Western blot for P-CREB, CREB, GLI1, GLI2, and GLI3. Cultured kidneys were pooled and homogenized to form protein lysates. H89-treated kidneys show a dramatic decrease in P-CREB. In contrast, Gant61- and Sant2-treated kidneys do not show this decrease. Sant2-treated kidneys show a reduction of GLI1, slight reduction of GLI2, and increased GLI3R. Gant61-treated kidneys do not show alteration of GLI protein levels. H89-treated kidneys show slight reduction of GLI1 and GLI3A. (D) MEFs derived from E14.5 wt and Thm1aln/aln mice harboring the BAT-gal allele were treated with L- (control) or Wnt3a-conditioned media overnight and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. Bars represent mean±SEM of 3 experiments. aln MEFs show elevated response to Wnt3a ligand. (E) Treatment of cultured Thm1aln/aln kidneys with 40 μM IWR-1 does not reduce cystogenic potential. (F) Quantification of kidney images following 4-day culture. Bars represent mean±SEM; n=8 control and n=3 Thm1aln/aln from 2 experiments. *P<0.05; **P<0.005; ***P<0.0005.

PKA activity is required to process full-length GLI3 proteins to form GLI3 repressor (GLI3R).11 To determine whether the Hh inhibitors were acting by increasing GLI3R levels, we examined GLI protein levels in treated cultured kidneys. In Sant2-treated kidneys, GLI1 was markedly reduced, GLI2 was slightly reduced, and GLI3R was increased (Figure 5C). These changes in GLI protein levels are consistent with downregulation of the Hh pathway at the level of SMO. Increased GLI3R is also consistent with the notion that higher levels of PKA activity enable enhanced GLI3 processing. Gant61, which inhibits at the level of GLI1- and GLI2-mediated transcriptional activity,32 did not show changes in GLI protein levels (Figure 5C). Interestingly, GLI1 and GLI3 activator levels were reduced in protein extracts of kidneys treated with the PKA inhibitor H89 (Figure 5C). Thus, in addition to H89 inhibiting the CFTR molecule responsible for fluid secretion,25 H89 may also partially inhibit Hh activity.

In contrast to Hh signaling, Wnt signaling has been studied extensively in cystic kidney disease, with the suggestion that overactive canonical Wnt signaling contributes to renal cystogenesis.22,33 Disruption of IFT in Kif3a−/− mutants or in cells of hypomorphic complex B IFT88orpk/orpk mutants can result in upregulated canonical Wnt signaling.34 However, the role of cilia in mediating Wnt signaling remains controversial because IFT mutant embryos show Hh mutant phenotypes rather than phenotypes characteristic of misregulated Wnt signaling (reviewed by Eggenschwiler and Anderson10). Currently, a role for an IFT complex A protein in Wnt signaling has not been reported, and the contrasting Hh phenotype of Thm1aln/aln from IFT complex B and motor mouse mutants further compelled us to examine the effect of THM1 on canonical Wnt signaling. We generated wt and Thm1aln/aln mice that harbor the β-catenin activated transgene (BAT)-gal Wnt reporter allele and created mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) lines. In the presence of Wnt3a ligand, Thm1aln/aln MEF showed higher β-galactosidase activity than wt cells (Figure 5D). Thus, cells lacking THM1 respond to Wnt ligand in a fashion similar to that of cells deficient in Kif3a and IFT88.

We next examined whether small molecule Wnt inhibitors might reduce Thm1aln/aln renal cystogenic potential. In cultured cells, nanomolar amounts of inhibitor of Wnt production-2 (IWP-2) and inhibitor of Wnt response-1 (IWR-1) inhibited production of the Wnt ligand and the Wnt response, respectively, while 10 μM IWR-1 suppressed tailfin regeneration in zebrafish, which requires canonical Wnt activity.35 In our initial analysis, 10 μM, 20 μM, and 40 μM of IWR-1 or IWP-2 did not reduce, but rather increased, tubular dilations in CD1 kidneys cultured with 8-Br-cAMP (Supplemental Figure 5). Moreover, 40 μM of IWR-1 did not reduce cystogenic potential of cultured Thm1aln/aln kidneys (Figure 5, E and F).

Small Molecule Hh Inhibitors Reduce Renal Cystogenic Potential of Cultured jck/jck and Pkd1m1Bei/m1Bei Kidneys

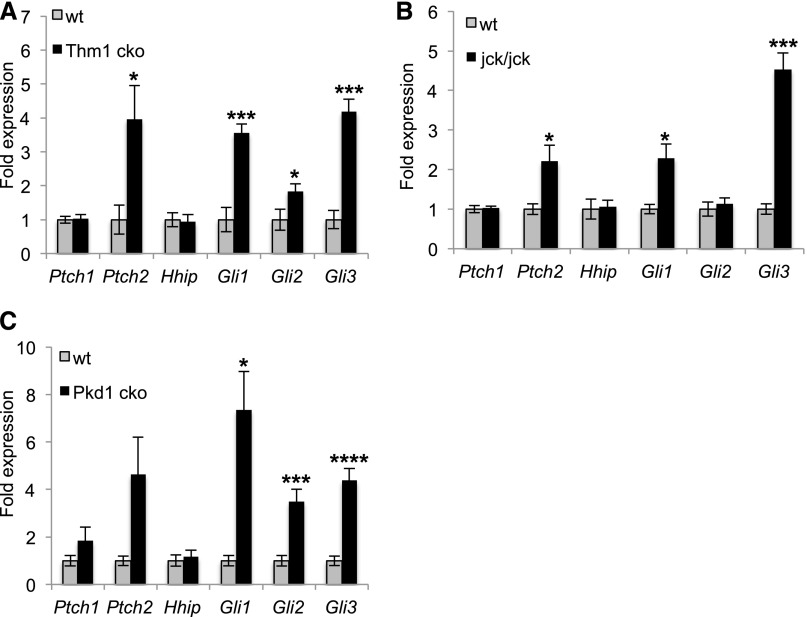

Intriguingly, Hh inhibitors Gant61 and Sant2 prevented tubular dilations not only in Thm1aln/aln kidneys but in wt kidneys as well (Figure 4B, Supplemental Figure 6 [Sant1]), suggesting a general role for Hh activity in cAMP-induced cystogenesis. We therefore questioned whether the Hh pathway could be implicated in other models of cystic kidney disease. Using quantitative RT-PCR, we observed increased expression of Ptch2, Gli1, Gli2, and Gli3 in kidneys of 6-week-old Thm1 cko mice (Figure 6A). Similarly, we examined Gli expression in jck and Pkd1 mutants. The jck mutant phenotypically resembles ADPKD29 and carries a mutation in the Nek8 kinase.36 Mutations in NEK8 have been identified in patients with nephronophthisis-937 and in the Lewis PKD rat.38 At 7 weeks of age, jck/jck mice showed a mean (±SEM) %KW/BW of 4.9±0.33 (n=11) compared with 1.3±0.04 in wt mice (n=19). Quantitative RT-PCR using RNA lysates from 7-week-old wt and jck/jck kidneys showed increased expression of Hh target genes, Ptch2, Gli1, and Gli3, in jck/jck cystic kidneys (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Expression of Hh signaling genes is increased in Thm1 cko, jck, and Pkd1 cko cystic kidneys. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis using RNA lysates of 5 wt and 5 Thm1 cko kidneys, of (B) 5 wt and 5 jck kidneys, or of (C) 5 wt and 4 Pkd1 cko kidneys. Bars represent mean±SEM of Ptch and Gli fold expression, normalized to housekeeping gene Oaz1, proposed as one of the more stable, reliable control genes for quantitative PCR.44 *P<0.05; ***P<0.0005; ****P<0.00005.

Using a conditional allele of Pkd1, together with a ubiquitous tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase, we deleted Pkd1, ortholog of the most commonly mutated gene in ADPKD, at P2. At P23, %KW/BW of wt (n=11) and Pkd1 cko mice (n=4) were 1.80±0.21 and 7.60±1.55, respectively. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed increased expression of Gli1, Gli2, and Gli3 in Pkd1 mutant kidneys (Figure 6C), suggesting upregulated Hh signaling.

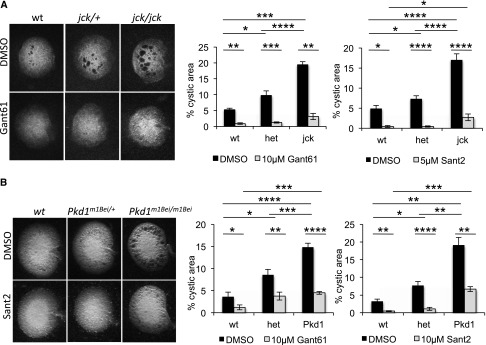

Next we examined whether Hh inhibitors could reduce cystogenic potential of cultured jck/jck mutant kidneys, which have shown increased cyst formation in the cAMP kidney explant assay.26 Similarly, we observed 2- and 3-fold higher cystogenic potentials in cultured jck/+ and jck/jck kidneys, compared with wt (Figure 7A). Importantly, this increased cystogenesis was markedly reduced by treatment with Gant61 or Sant2.

Figure 7.

Small molecule Hh inhibitors reduce cystogenic potential of cultured jck/jck and Pkd1m1Bei/m1Bei kidneys. (A) E13.5 jck/jck kidneys and (B) E14.5 Pkd1m1Bei/Pkd1m1Bei were cultured in the presence of 100 μM 8-bromo-cAMP, in combination with 10 μM Gant61, 5 μM or 10 μM Sant2 (for jck/jck or Pkd1m1Bei/Pkd1m1Bei kidneys, respectively), or control DMSO for 4 days. Graphs represent quantification of kidney images following 4-day culture. Bars represent mean±SEM; n=3 wt, n=9 jck/+, and n=5 jck/jck kidneys from 3 experiments for Gant61; n=5 wt, n=9 jck/+, and n=8 jck/jck kidneys from 4 experiments for Sant2; n=6 wt, n=12 Pkd1m1Bei/+, and n=9 Pkd1m1Bei/Pkd1m1Bei from 4 experiments for Gant61; n=7 wt, n=10 Pkd1m1Bei/+ and n=6 Pkd1m1Bei/Pkd1m1Bei from 4 experiments for Sant2. *P<0.05; **P<0.005; ***P<0.0005; ****P<0.00005.

To determine the effect of Hh inhibitors on cultured Pkd1 mutant kidneys, we used the N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea–derived Pkd1m1Bei/m1Bei mouse mutant, which carries a missense mutation in Pkd1.39 Like Pkd1−/− mutants, Pkd1m1Bei/m1Bei embryos are edemic with renal tubular dilations and die during late development. In the cAMP cystogenic assay, the Pkd1m1Bei allele increases cystogenic potential.25 We observed 2- and 3-fold higher cystogenic potentials in cultured Pkd1m1Bei/+ and Pkd1m1Bei/m1Bei kidneys, respectively, relative to wt (Figure 7B). As seen with Thm1aln/aln and jck/jck kidneys, treatment with Gant61 or Sant2 dramatically reduced cystogenic potential of cultured Pkd1m1Bei/m1Bei kidneys.

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate a role for THM1 loss in renal cystogenesis. The Thm1aln allele increases renal cystogenic potential and causes renal tubular dilations in homozygous embryos. This renal phenotype combined with the polydactyly and exencephaly of Thm1aln/aln mutants17 models the clinical trial of Meckel-Gruber syndrome.40 The clinical relevance of THM1 is underscored by the finding that THM1 contributes the most pathogenic alleles in patients with infantile and pediatric ciliopathies.24 Further, Thm1 ablation during late embryogenesis results in cystic kidney disease in adulthood, showing that THM1 loss can cause both pediatric and adult forms of the cystic kidney disease spectrum.

Because THM1 negatively regulates Hh signaling,17 we investigated a role for increased Hh signaling in renal cystogenesis, which has been largely unexplored. Reducing Gli2 dosage or culturing with Hh inhibitors reduced renal cystogenic potential in Thm1aln/aln kidneys and deleting Gli2 attenuated cystic kidney disease of Thm1 cko mice, implicating a causal role for increased Hh signaling in Thm1 renal cystogenesis. In mice, loss of GLI2 does not result in a renal phenotype, but increased expression of GLI3R in a mouse model of Pallister-Hall syndrome causes nonobstructive hydronephrosis.12 These findings suggest redundancy among the GLI activators in the kidney and highlight the essential function of GLI3R in maintaining appropriate Hh activity levels. Because GLI2 normally does not show a functional role in kidney development, attenuation of Thm1 renal cystogenesis by loss of GLI2 suggests that the Thm1 ciliary defect enhances GLI2 function in the postnatal kidney. Similarly, enhanced GLI2 activity is evident and causative of the neural tube defects in the Thm1aln/aln developmental mutant. Enhanced GLI3A activity also contributes to the Thm1aln/aln neural tube defects, and Western blot analyses of Thm1aln/aln anterior limb buds revealed that loss of THM1 increases GLI3A levels, without altering GLI3R levels.17 Such differences in GLI protein levels were not detectable in whole kidney extracts. It is possible that assaying whole kidney extracts dilutes expression differences that might occur in a cell type–specific manner. Finally, Hh inhibitors also prevented cysts in jck and Pkd1m1Bei cultured kidneys, suggesting that increased Hh signaling may have a general role in renal tubular dilation and cyst formation.

Like IFT complex B mutant cells, Thm1-null cells showed an elevated response to Wnt3a ligand, reflecting upregulated canonical Wnt signaling. However, small molecule Wnt inhibitors did not reduce cysts in the kidney explant assay. Two reports suggest that overactive canonical Wnt signaling does not contribute to renal cystogenesis in Pkd1, Pkd2, and inversin mouse mutants.41,42 Thus, our data may reflect the possibility that canonical Wnt signaling does not play a role in cAMP-mediated tubular dilation. Alternatively, our results may suggest that examining the role of Wnt signaling in renal cystogenesis in vivo is more appropriate. Regardless, lack of prevention of renal cysts in this cAMP culture assay suggests that the preventive effect of the Hh inhibitors is not occurring through the canonical Wnt pathway.

The Hh inhibitors also did not exert their beneficial effects by inhibiting PKA. Conversely, the PKA inhibitor H89 decreased levels of GLI1 and GLI3A, suggesting that in addition to regulating CFTR and fluid secretion, H89 may also act by partially inhibiting the Hh pathway. Although Gant61 has been shown to inhibit GLI1 and GLI2 from binding to their target DNA sites32 and prevents GLI2 from localizing to the ciliary distal tip in cellular studies (data not shown), which is required for GLI2 activation,43 Gant61-treated kidneys did not alter GLI protein levels. Aside from the Hh components that are also targets of the pathway, ChIP assays have revealed Pax2 and Cyclin D1 as transcriptional targets of Hh signaling (N. Rosenblum, personal communication). Examination of such targets would help in assessing Gant61 action.

The molecular mechanism by which Hh signaling may contribute to renal cystogenesis remains undefined. It is possible that Hh signaling contributes directly to increased proliferation of cyst-lining epithelial cells. Alternatively, it has been suggested that low levels of Hh activity in mature kidneys maintain renal epithelial cells in a differentiated state.44 Altered Ca2+ homeostasis is another hallmark of PKD, and several studies suggest that Hh signaling modulates Ca2+ levels. In a lung cancer cell line, an SMO inhibitor, GDC-0449, was shown to increase steady-state levels of Ca2+.45 Conversely, SMO may act as a G protein–coupled receptor, and Ca2+ imaging of Xenopus embryonic spinal cells showed Sonic HH ligand acutely increased Ca2+ spike activity through SMO activation.46 Although these studies show different effects of Hh activity on Ca2+, the possibility of an interplay between Hh and Ca2+ signaling in kidney cells may merit investigation.

If increased Hh signaling plays a role in Thm1 renal cystogenesis, then molecular mechanisms must be different between Thm1 and the complex B mutants, which cannot fully activate the Hh pathway (reviewed by Eggenschwiler and Anderson10). Even among IFT complex B mouse mutants, there is variation in which Wnt branch—canonical or noncanonical—is perturbed before cysts arise and once cysts have formed.20,21,33,47–49 Thus, despite a unifying primary cilia hypothesis in renal cystogenesis, differences appear between mouse models in alteration of signaling pathways, which likely reflect heterogeneity of cystic kidney disease pathogenesis. This highlights the importance of better understanding the molecular mechanisms by which cilia/IFT mediate Hh and Wnt signaling.

Cystic kidneys of the complex A IFT140 cko mouse also showed increased Gli expression.23 Thus, data from five mouse models—IFT140,23 Glis2,15 Thm1, jck, and Pkd1—suggest elevated Hh signaling in cystic kidneys. Additionally, a global gene expression analysis of kidneys from patients with ADPKD revealed increased expression of Hh signaling components, including GLI2, Ptch1, and GAS1.50 While the Thm1 ciliary defect, and likely that of IFT140, directly upregulates the Hh pathway and Glis2 represses Hh signaling in the kidney, further investigation will be required to determine the mechanism by which Hh signaling is upregulated in jck and Pkd1 mutant kidneys.

In summary, our data reveal a role for THM1 loss in renal cystogenesis and a protective role for downregulating Hh signaling in the Thm1 cko mouse and in cultured kidneys of three independent genetic mouse models of cystic kidney disease. This compels analysis of whether Hh inhibitors reduce renal cystogenesis in these mouse models in vivo. If these Hh inhibitors are effective in vivo, several Hh inhibitors are being tested in clinical trials for cancer (reviewed by Tran et al.51), which will facilitate translation of these experiments to therapeutic application.

Concise Methods

Generation of Thm1 and Pkd1 conditional knock-out mice

A Thm1-lacZ knockout mouse (Ttc21btm2a(KOMP)Wtsi) was purchased from KOMP (Knockout Mouse Project). The major components of the targeting vector consisted of a LacZ gene flanked by Frt sites in intron 3 of Thm1 and of loxP sites flanking exon 4. To create Thm1flox/flox mice with conditional deletion potential, Thm1-lacZ mice were mated to FLPeR mice (gift from Susan Dymecki, Harvard Medical School), which express FLPe recombinase. Resulting progeny expressing FLPe recombinase showed excision of the Frt-flanked lacZ gene and continued Thm1 transcription from exon 3 to exon 4. These Thm1flox/+ mice were intercrossed to generate Thm1flox/flox mice. The tamoxifen-inducible ROSA26CreERT mouse was purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (004847) and mated to Thm1aln/+ mice to create Thm1aln/+; ROSA26CreERT+ mice. Male Thm1aln/+; ROSA26CreERT+ mice were time-mated with Thm1flox/flox females. E17.5 pregnant females were injected intraperitoneally with tamoxifen (Sigma) at a dose of 9 mg/kg mouse body weight to generate Thm1aln/−; ROSA26CreERT/+ (or Thm1 cko) mice. Alternatively, 5-week-old wt and Thm1aln/−; ROSA26CreERT/+ mice were injected intraperitoneally with tamoxifen to examine the effects of deleting Thm1 in fully developed kidneys.

Pkd1flox/flox mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (010671). Pkd1flox/flox females were mated to Pkd1flox/+; ROSA26-CreERT/+ males to create Pkd1flox/flox; ROSA26-CreERT/+ mice. At P2, Pkd1flox/flox nursing mothers were injected with 10 mg tamoxifen/kg mouse body weight to induce Pkd1 deletion in pups.

Mouse Genotyping

Tail biopsies (1–2 mm) or yolk sacs were used to extract DNA by alkaline lysis. Tails were boiled in 50–200 µl 50 mM NaOH for 10 minutes and briefly vortexed. One tenth the volume of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH, 8.0) was added, followed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 6 minutes. One microliter of supernatant was used for subsequent genotyping. Thm1aln/aln mice were genotyped as described elsewhere,17 using primers alndiag-F and alndiag-R, followed by amplicon digestion with AvaII. jck mice were genotyped using primers jck-F and jck-R and subsequent amplicon digestion with BseYI. Pkd1m1Bei mice were genotyped using a Taqman assay as described previously.25 Pkd1flox allele was genotyped using primers, Pkd1f-F and Pkd1f-R, as described by The Jackson Laboratory. Primer and probe sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Histology

Kidneys were dissected and renal capsules were removed. Kidneys were then bisected longitudinally and fixed in Bouin solution for several days. Tissue was dehydrated through a series of ethanol, xylene (two changes), paraffin (two changes), then embedded in paraffin. Sections of 7 μm were obtained using a microtome and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

BUN and cAMP Measurements

Trunk blood was collected and serum was obtained using Microvette CB 300 Blood Collection System tubes (Kent Scientific). Serum BUN was measured using the QuantiChrom Urea Assay Kit (BioAssay Systems) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Dissected kidneys were halved or quartered and snap-frozen. Kidney pieces were homogenized in 0.1 M HCl using a Bullet Blender Storm (MidSci). Levels of cAMP were obtained from kidney homogenates using the cAMP Enzyme Immunoassay Kit, Direct (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein concentrations of kidney homogenates were obtained using a BCA Protein Assay (Pierce).

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Six-week-old kidneys were dissected in PBS and fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at 4°C. Kidneys were dehydrated in an ethanol series, dried in an EMS Critical Point Dryer, mounted onto metal stubs, and coated in a Pelco SC-6 Sputter Coater. Renal primary cilia were visualized using a Hitachi S-2700 Scanning Electron Microscope equipped with a Quartz PCI digital camera.

Immunofluorescence

After removal of renal capsules, dissected kidneys were bisected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Tissue was dehydrated through a series of ethanol, xylene, and paraffin, and then embedded in paraffin. Sections of 7 μm were obtained using a microtome. Antigen retrieval using sodium citrate buffer (pH, 6) was performed. Tissue was blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 hour, then incubated with lectins, LTL, and DBA (1:50; Vector Laboratories) or primary antibodies against α6F (1:1000; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), Tamms–Horsfall Protein (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PCNA (1:2000; Cell Signaling Technology), acetylated α-tubulin (1:4000; Sigma-Aldrich). Sections were washed three times with PBS, and then incubated with appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to AlexaFluor 488 or AlexaFluor 594. After three washes of PBS, sections were mounted with Vectashield with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories). Staining was visualized using a Zeiss Axiophot fluorescence microscope and imaged with a Leica DFC 350 camera or a Nikon 80i fluorescence microscope equipped with a Nikon DS-Fi1 camera.

Quantification of Proliferation Rates

PCNA+ cells and DAPI-stained nuclei were manually counted using the Cell Counter plug-in of ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Kidney Explant Cultures

Kidneys were dissected from E13.5 Thm1aln/aln or jck/jck embryos or from E14.5 Pkd1m1Bei/m1Bei embryos and cultured on 1-μm pore inserts in a six-well plate with DMEM/F12 media (Life Technologies) containing penicillin and streptomycin. Kidneys were cultured in the presence of 100 μM 8-bromo-cAMP (Sigma-Aldrich), with or without Sant1 (Sigma-Aldrich), Sant2 (Alexis Biochemicals), Gant61 (Alexis Biochemicals), IWR-1 (Sigma-Aldrich), IWP (Sigma-Aldrich), or H89 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 days. Media and small molecules were refreshed daily. Kidneys were imaged using a Leica MZ12.5 stereoscope and a DFC500 camera. Images were quantified using ImageJ software. For each kidney, the cystic areas were calculated and summed, then divided by the total area of the kidney in question.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted using Trizol (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s protocol. One microgram of RNA was converted to cDNA using Quanta Biosciences qScript cDNA Supermix (VWR International). Quantitative PCR analysis was performed using Quanta Biosciences Perfecta qPCR Supermix (VWR International) and a Bio-Rad CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System. Primers used for detection of Ptch1, Gli1, Gli2, Gli3, and housekeeping gene Oaz1 (proposed as one of the more stable, reliable control genes for quantitative PCR)52 were designed using the Roche Applied Science RT-qPCR Assay Design Center (http://www.roche-applied-science.com/shop/CategoryDisplay?catalogId=10001&tab=&identifier=Universal+Probe+Library&langId=-1&storeId=15006). All amplicons span an intron and were annealed at 60°C. Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Western Blot

Protein extracts were obtained by pooling four cultured kidneys and homogenizing them using Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) containing proteinase inhibitor cocktail (Pierce). Western blots were performed as described,17 using primary antibodies against CREB, P-CREB, GLI1 (Cell Signaling Technology), GLI2 (generous gifts from Drs. J. Eggenschwiler and B. Wang), GLI3 (R&D Systems), and α-tubulin (DM1A from Sigma-Aldrich). Signal was detected using SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce).

BAT-gal Assays

Thm1aln/+ heterozygous mice were mated to mice harboring a β-galactosidase transgene (B6.Cg-Tg[BAT-lacZ]3Picc/J; The Jackson Laboratory; Stock 005317). MEFs were then isolated from E14.5 wt; BAT-lacZ and Thm1aln/aln; BAT-lacZ embryos, then treated with either L (control) or Wnt3a-conditioned media as described previously.34 BAT-gal activity was measured using the Galacto-Light Plus System (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significance was calculated using a t test (Excel; Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Barbara Fegley of the University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC) Electron Microscopy Core and Jing Huang of the KUMC Histology Core for their technical assistance. We thank members of the Beier Lab, the Harvard Center for PKD Research, and the KUMC Kidney Institute for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by a Pilot and Feasibility Project Award from the Harvard Center for PKD Research (PI: Jing Zhou), R21DK088048, ASN Gottschalk Research Scholar Award, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (P20-GM104936-06, PI: Dale Abrahamson) and NIH K-INBRE (P20-GM103418, PI: Joan Hunt) to P.V.T., an NIH T32 Postdoctoral Fellowship (DK71496-6 A1, PI: Jared Grantham) to D.T.J., and an R01-HD36404 to D.R.B.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2013070735/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Torres VE, Harris PC: Mechanisms of disease: Autosomal dominant and recessive polycystic kidney diseases. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2: 40–55, quiz 55, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinlan RJ, Tobin JL, Beales PL: Modeling ciliopathies: Primary cilia in development and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol 84: 249–310, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nauli SM, Rossetti S, Kolb RJ, Alenghat FJ, Consugar MB, Harris PC, Ingber DE, Loghman-Adham M, Zhou J: Loss of polycystin-1 in human cyst-lining epithelia leads to ciliary dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1015–1025, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nauli SM, Alenghat FJ, Luo Y, Williams E, Vassilev P, Li X, Elia AE, Lu W, Brown EM, Quinn SJ, Ingber DE, Zhou J: Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nat Genet 33: 129–137, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Q, Pan J, Snell WJ: Intraflagellar transport particles participate directly in cilium-generated signaling in Chlamydomonas. Cell 125: 549–562, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ocbina PJ, Eggenschwiler JT, Moskowitz I, Anderson KV: Complex interactions between genes controlling trafficking in primary cilia. Nat Genet 43: 547–553, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ingham PW, Nakano Y, Seger C: Mechanisms and functions of Hedgehog signalling across the metazoa. Nat Rev Genet 12: 393–406, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corbit KC, Aanstad P, Singla V, Norman AR, Stainier DY, Reiter JF: Vertebrate Smoothened functions at the primary cilium. Nature 437: 1018–1021, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohatgi R, Milenkovic L, Scott MP: Patched1 regulates hedgehog signaling at the primary cilium. Science 317: 372–376, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggenschwiler JT, Anderson KV: Cilia and developmental signaling. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23: 345–373, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang B, Fallon JF, Beachy PA: Hedgehog-regulated processing of Gli3 produces an anterior/posterior repressor gradient in the developing vertebrate limb. Cell 100: 423–434, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cain JE, Islam E, Haxho F, Blake J, Rosenblum ND: GLI3 repressor controls functional development of the mouse ureter. J Clin Invest 121: 1199–1206, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen ST, Ott CM: Cell signaling. A ciliary signaling switch. Science 317: 330–331, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu MC, Mo R, Bhella S, Wilson CW, Chuang PT, Hui CC, Rosenblum ND: GLI3-dependent transcriptional repression of Gli1, Gli2 and kidney patterning genes disrupts renal morphogenesis. Development 133: 569–578, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attanasio M, Uhlenhaut NH, Sousa VH, O'Toole JF, Otto E, Anlag K, Klugmann C, Treier AC, Helou J, Sayer JA, Seelow D, Nurnberg G, Becker C, Chudley AE, Nurnberg P, Hildebrandt F, Treier M: Loss of GLIS2 causes nephronophthisis in humans and mice by increased apoptosis and fibrosis. Nat Genet 39: 1018–1024, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan SK, Riley PR, Price KL, McElduff F, Winyard PJ, Welham SJ, Woolf AS, Long DA: Corticosteroid-induced kidney dysmorphogenesis is associated with deregulated expression of known cystogenic molecules, as well as Indian hedgehog. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F346–F356, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tran PV, Haycraft CJ, Besschetnova TY, Turbe-Doan A, Stottmann RW, Herron BJ, Chesebro AL, Qiu H, Scherz PJ, Shah JV, Yoder BK, Beier DR: THM1 negatively modulates mouse sonic hedgehog signal transduction and affects retrograde intraflagellar transport in cilia. Nat Genet 40: 403–410, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qin J, Lin Y, Norman RX, Ko HW, Eggenschwiler JT: Intraflagellar transport protein 122 antagonizes Sonic Hedgehog signaling and controls ciliary localization of pathway components. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 1456–1461, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoder BK, Tousson A, Millican L, Wu JH, Bugg CE, Jr, Schafer JA, Balkovetz DF: Polaris, a protein disrupted in orpk mutant mice, is required for assembly of renal cilium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F541–F552, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonassen JA, San Agustin J, Follit JA, Pazour GJ: Deletion of IFT20 in the mouse kidney causes misorientation of the mitotic spindle and cystic kidney disease. J Cell Biol 183: 377–384, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel V, Li L, Cobo-Stark P, Shao X, Somlo S, Lin F, Igarashi P: Acute kidney injury and aberrant planar cell polarity induce cyst formation in mice lacking renal cilia. Hum Mol Genet 17: 1578–1590, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin F, Hiesberger T, Cordes K, Sinclair AM, Goldstein LS, Somlo S, Igarashi P: Kidney-specific inactivation of the KIF3A subunit of kinesin-II inhibits renal ciliogenesis and produces polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 5286–5291, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonassen JA, SanAgustin J, Baker SP, Pazour GJ: Disruption of IFT complex A causes cystic kidneys without mitotic spindle misorientation. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 641–651, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis EE, Zhang Q, Liu Q, Diplas BH, Davey LM, Hartley J, Stoetzel C, Szymanska K, Ramaswami G, Logan CV, Muzny DM, Young AC, Wheeler DA, Cruz P, Morgan M, Lewis LR, Cherukuri P, Maskeri B, Hansen NF, Mullikin JC, Blakesley RW, Bouffard GG, Gyapay G, Rieger S, Tonshoff B, Kern I, Soliman NA, Neuhaus TJ, Swoboda KJ, Kayserili H, Gallagher TE, Lewis RA, Bergmann C, Otto EA, Saunier S, Scambler PJ, Beales PL, Gleeson JG, Maher ER, Attie-Bitach T, Dollfus H, Johnson CA, Green ED, Gibbs RA, Hildebrandt F, Pierce EA, Katsanis N: TTC21B contributes both causal and modifying alleles across the ciliopathy spectrum. Nat Genet 43: 189–196, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magenheimer BS, St John PL, Isom KS, Abrahamson DR, De Lisle RC, Wallace DP, Maser RL, Grantham JJ, Calvet JP: Early embryonic renal tubules of wild-type and polycystic kidney disease kidneys respond to cAMP stimulation with cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator/Na(+),K(+),2Cl(-) Co-transporter-dependent cystic dilation. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3424–3437, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natoli TA, Gareski TC, Dackowski WR, Smith L, Bukanov NO, Russo RJ, Husson H, Matthews D, Piepenhagen P, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O: Pkd1 and Nek8 mutations affect cell-cell adhesion and cilia in cysts formed in kidney organ cultures. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F73–F83, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piontek K, Menezes LF, Garcia-Gonzalez MA, Huso DL, Germino GG: A critical developmental switch defines the kinetics of kidney cyst formation after loss of Pkd1. Nat Med 13: 1490–1495, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davenport JR, Watts AJ, Roper VC, Croyle MJ, van Groen T, Wyss JM, Nagy TR, Kesterson RA, Yoder BK: Disruption of intraflagellar transport in adult mice leads to obesity and slow-onset cystic kidney disease. Current biology: CB, 17: 1586-1594, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith LA, Bukanov NO, Husson H, Russo RJ, Barry TC, Taylor AL, Beier DR, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O: Development of polycystic kidney disease in juvenile cystic kidney mice: Insights into pathogenesis, ciliary abnormalities, and common features with human disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2821–2831, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hopp K, Ward CJ, Hommerding CJ, Nasr SH, Tuan HF, Gainullin VG, Rossetti S, Torres VE, Harris PC: Functional polycystin-1 dosage governs autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease severity. J Clin Invest 122: 4257–4273, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torres VE, Wang X, Qian Q, Somlo S, Harris PC, Gattone VH, 2nd: Effective treatment of an orthologous model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Med 10: 363–364, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lauth M, Bergstrom A, Shimokawa T, Toftgard R: Inhibition of GLI-mediated transcription and tumor cell growth by small-molecule antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 8455–8460, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saadi-Kheddouci S, Berrebi D, Romagnolo B, Cluzeaud F, Peuchmaur M, Kahn A, Vandewalle A, Perret C: Early development of polycystic kidney disease in transgenic mice expressing an activated mutant of the beta-catenin gene. Oncogene 20: 5972–5981, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corbit KC, Shyer AE, Dowdle WE, Gaulden J, Singla V, Chen MH, Chuang PT, Reiter JF: Kif3a constrains beta-catenin-dependent Wnt signalling through dual ciliary and non-ciliary mechanisms. Nat Cell Biol 10: 70–76, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen B, Dodge ME, Tang W, Lu J, Ma Z, Fan CW, Wei S, Hao W, Kilgore J, Williams NS, Roth MG, Amatruda JF, Chen C, Lum L: Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat Chem Biol 5: 100–107, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu S, Lu W, Obara T, Kuida S, Lehoczky J, Dewar K, Drummond IA, Beier DR: A defect in a novel Nek-family kinase causes cystic kidney disease in the mouse and in zebrafish. Development 129: 5839–5846, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otto EA, Trapp ML, Schultheiss UT, Helou J, Quarmby LM, Hildebrandt F: NEK8 mutations affect ciliary and centrosomal localization and may cause nephronophthisis. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 587–592, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCooke JK, Appels R, Barrero RA, Ding A, Ozimek-Kulik JE, Bellgard MI, Morahan G, Phillips JK: A novel mutation causing nephronophthisis in the Lewis polycystic kidney rat localises to a conserved RCC1 domain in Nek8. BMC Genomics 13: 393, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herron BJ, Lu W, Rao C, Liu S, Peters H, Bronson RT, Justice MJ, McDonald JD, Beier DR: Efficient generation and mapping of recessive developmental mutations using ENU mutagenesis. Nat Genet 30: 185–189, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parelkar SV, Kapadnis SP, Sanghvi BV, Joshi PB, Mundada D, Oak SN: Meckel-Gruber syndrome: A rare and lethal anomaly with review of literature. J Pediatr Neurosci 8: 154–157, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller MM, Iglesias DM, Zhang Z, Corsini R, Chu L, Murawski I, Gupta I, Somlo S, Germino GG, Goodyer PR: T-cell factor/beta-catenin activity is suppressed in two different models of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 80: 146–153, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugiyama N, Tsukiyama T, Yamaguchi TP, Yokoyama T: The canonical Wnt signaling pathway is not involved in renal cyst development in the kidneys of inv mutant mice. Kidney Int 79: 957–965, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haycraft CJ, Banizs B, Aydin-Son Y, Zhang Q, Michaud EJ, Yoder BK: Gli2 and Gli3 localize to cilia and require the intraflagellar transport protein polaris for processing and function. PLoS Genet 1: e53, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li B, Rauhauser AA, Dai J, Sakthivel R, Igarashi P, Jetten AM, Attanasio M: Increased hedgehog signaling in postnatal kidney results in aberrant activation of nephron developmental programs. Hum Mol Genet 20: 4155–4166, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tian F, Schrodl K, Kiefl R, Huber RM, Bergner A: The hedgehog pathway inhibitor GDC-0449 alters intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and inhibits cell growth in cisplatin-resistant lung cancer cells. Anticancer Res 32: 89–94, 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belgacem YH, Borodinsky LN: Sonic hedgehog signaling is decoded by calcium spike activity in the developing spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 4482–4487, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nishio S, Tian X, Gallagher AR, Yu Z, Patel V, Igarashi P, Somlo S: Loss of oriented cell division does not initiate cyst formation. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 295–302, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simons M, Gloy J, Ganner A, Bullerkotte A, Bashkurov M, Kronig C, Schermer B, Benzing T, Cabello OA, Jenny A, Mlodzik M, Polok B, Driever W, Obara T, Walz G: Inversin, the gene product mutated in nephronophthisis type II, functions as a molecular switch between Wnt signaling pathways. Nat Genet 37: 537–543, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saburi S, Hester I, Fischer E, Pontoglio M, Eremina V, Gessler M, Quaggin SE, Harrison R, Mount R, McNeill H: Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nat Genet 40: 1010–1015, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song X, Di Giovanni V, He N, Wang K, Ingram A, Rosenblum ND, Pei Y: Systems biology of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): Computational identification of gene expression pathways and integrated regulatory networks. Hum Mol Genet 18: 2328–2343, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tran PV, Lachke SA, Stottmann RW: Toward a systems-level understanding of the Hedgehog signaling pathway: Defining the complex, robust, and fragile. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 5: 83–100, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Jonge HJ, Fehrmann RS, de Bont ES, Hofstra RM, Gerbens F, Kamps WA, de Vries EG, van der Zee AG, te Meerman GJ, ter Elst A: Evidence based selection of housekeeping genes. PLoS ONE 2: e898, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.