Abstract

Antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR) is the leading cause of kidney allograft loss. We investigated whether the addition of gene expression measurements to conventional methods could serve as a molecular microscope to identify kidneys with ABMR that are at high risk for failure. We studied 939 consecutive kidney recipients at Necker Hospital (2004–2010; principal cohort) and 321 kidney recipients at Saint Louis Hospital (2006–2010; validation cohort) and assessed patients with ABMR in the first 1 year post-transplant. In addition to conventional features, we assessed microarray-based gene expression in transplant biopsy specimens using relevant molecular measurements: the ABMR Molecular Score and endothelial donor-specific antibody-selective transcript set. The main outcomes were kidney transplant loss and progression to chronic transplant injury. We identified 74 patients with ABMR in the principal cohort and 54 patients with ABMR in the validation cohort. Conventional features independently associated with failure were donor age and humoral histologic score (g+ptc+v+cg+C4d). Adjusting for conventional features, ABMR Molecular Score (hazard ratio [HR], 2.22; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.37 to 3.58; P=0.001) and endothelial donor-specific antibody-selective transcripts (HR, 3.02; 95% CI, 1.00 to 9.16; P<0.05) independently associated with an increased risk of graft loss. The results were replicated in the independent validation group. Adding a gene expression assessment to a traditional risk model improved the stratification of patients at risk for graft failure (continuous net reclassification improvement, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.57 to 1.46; P<0.001; integrated discrimination improvement, 0.16; P<0.001). Compared with conventional assessment, the addition of gene expression measurement in kidney transplants with ABMR improves stratification of patients at high risk for graft loss.

Kidney transplantation is the preferred treatment for patients with ESRD, and it is routinely performed in more than 80 countries.1 The current standard of care in transplant medicine is largely based on biopsy assessment by histology and immunochemistry supported by laboratory tests, such as HLA antibody measurements.

A key role of the biopsy is to diagnose rejection, particularly antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR), which is the leading cause of kidney transplant failure.2–4 Kidney allograft loss is now acknowledged to lead to increased morbidity, mortality, and cost.5,6 In ABMR, the conventional assessment by histopathology, despite its clinical use, faces serious limitations in terms of diagnostic accuracy and risk prediction, which is illustrated by the call for action raised during the International Banff Allograft Rejection Classification meeting held in Brazil in 2013 for the development of complementary approaches in the field of allograft rejection.

ABMR reflects the need for more diagnostic support than is provided by the conventional histologic assessment, but improvements are not likely to be associated with additional adjustments to this existing technique, indicating the need for new technologies. The limitations of conventional tests can be addressed by introducing molecular biopsy measurements developed using data from well defined cohorts, which is illustrated by the experiences in cancer medicine, where molecular biopsy measurements using scores derived from well defined cohorts now provide new levels of information7–9 and have changed clinical practice.7–9 In transplant medicine, molecular profiling strategies using microarrays have shown promise as a new dimension for assessing transplant biopsies, which was recently shown by the development of a microarray-based molecular microscope system for testing of biopsies for T cell–mediated rejection,10 ABMR,11,12 and AKI.13 However, to date, studies11,12 focused on late ABMR (the prevalence of early ABMR in these low-risk cohorts is less than 2% of biopsies with molecular assessment). Moreover, there was heterogeneity in the clinical and therapeutic management of the patients and superimposed diseases in late cases, precluding any conclusions about the clinical relevance of the molecular microscope in early ABMR. As in cancer, homogenous and well phenotyped cohorts are needed to ascertain whether the molecular microscope strategy could be helpful and add to the conventional assessments. To achieve this goal, we used a unique model of early disease (early biopsy-proven ABMR) with intensive follow-up and standardized management with Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–recommended therapeutic strategies.14 This model led us to focus on the disease progression related to the ongoing humoral process without the interference from superimposed diseases seen in late ABMR cases.

In the present study, we applied the molecular microscope system in addition to conventional clinical histologic and immunologic features to evaluate the potential impact of this approach in terms of prediction of the risk of graft loss and disease progression.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the Kidney Transplant Recipients

Among 939 patients who received a kidney transplant in the Necker Hospital between 2004 and 2010, 472 patients had 583 biopsies performed in the first 1 year post-transplant. In all, 77 samples (13.2%) showed acute tubular necrosis, 48 samples (8.2%) had isolated interstitial fibrosis tubular atrophy, 51 samples (8.7%) had T cell–mediated rejection, 43 samples (7.4%) had borderline lesions, 48 samples (8.2%) had calcineurin inhibitor toxic effects, 26 samples (4.4%) had recurrent diseases, 23 samples (3.9%) had BK virus nephropathy, and 56 samples (9.6%) had other diagnoses. Biopsy-proven ABMR was diagnosed in 101 of 939 patients in the first 1 year, representing an incidence of 10.7%. Among these 101 ABMR patients, 74 patients (73.3%) had suitable material for a molecular assessment and were enrolled in this study. Table 1 shows the characteristics at transplantation and the time of biopsy for 74 patients who had an episode of ABMR diagnosed in the first 1 year post-transplant at a median of 3.1 (interquartile range [IQR]=0.2–12.0) months post-transplant. All the patients were sensitized before transplantation with lymphocytotoxic panel-reactive antibodies ranging from 5% to 100%. At the time of transplantation, 68 of 74 patients (91.9%) had detectable donor-specific antibodies (DSAs), with 44 patients (64.7%) having 1 DSA and 24 patients (35.3%) having ≥2 DSAs (range=2–4). The immunodominant mean fluorescence intensity DSA (DSA MFImax) was class I in 25 of 68 patients (36.8%) and class II in 43 of 68 patients (63.2%), and the mean DSA MFImax was 5548±562. The median follow-up time after transplantation was 59.3 (IQR=47–79) months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the ABMR population

| Patient Demographics (n=74) | |

|---|---|

| Mean recipient age, yra | 48.4±13 |

| Cold ischemia time, ha | 21.4±12 |

| Serum creatinine at the time of donation, µmol/La | 83.8±41 |

| Delayed graft function, n | 27 (36.4%) |

| Number of dialyses post-transplanta | 1.2±1.9 |

| Rank of transplantation (>1) | 34 (48.6%) |

| Deceased donor, n | 67 (90.5%) |

| Primary disease | |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 1 (1.3%) |

| Hypertension/large vessel disease | 4 (5.4%) |

| GN/v | 21 (28.4%) |

| Interstitial nephritis/pyelonephritis | 13 (17.6%) |

| Others | 11 (14.9%) |

| Unknown etiology | 24 (32.4%) |

| Mean donor age, yra | 51.1±14 |

| Donor sex, n (men) | 43 (58.1%) |

| Immunology | |

| HLA-A mismatcha | 0.8±0.6 |

| HLA-B mismatcha | 1.1±0.7 |

| HLA-DR mismatcha | 0.8±0.6 |

| DSA status on the day of transplantation | |

| Lymphocytotoxic PRA, % (mean)a | 27±29 |

| cPRA, % (mean)a | 73 |

| Circulating DSA, n | 68 (91.9%) |

| Number of DSA (=1; ≥2) | 44 (64.7%); 24 (35.3%) |

| DSAmax class (class I/class II), n | 25 (36.8%)/43 (63.2%) |

| Class I DSAmax MFIb | 2641±410 |

| Class II DSAmax MFIb | 3783±602 |

| Class I or II DSAmax MFIb | 5548±562 |

| Characteristics at the time of biopsy | |

| Serum creatinine, µmol/La | 203±142 |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2a | 44.8±17 |

| Proteinuria, g/La | 0.31±0.58 |

| Patients with urine protein>0.15 g/L | 38 (51%) |

| Circulating DSA, n | 74 (100%) |

| Number of DSA (=1; ≥2) | 56 (75.7%); 18 (24.3%) |

| DSAmax class (class I/class II) , n | 26 (35.1%); 48 (64.9%) |

| Class I DSAmax MFIb | 2315±568 |

| Class II DSAmax MFIb | 3732±641 |

| Class I or II DSAmax MFIb | 3859±471 |

Calculated panel-reactive antibody (cPRA) assessed in patients transplanted after January 1, 2009, n=11.

Continuous variables expressed as the mean±SD.

Continuous variables expressed as the mean±SEM.

Histologic and Immunologic Features of Acute ABMR

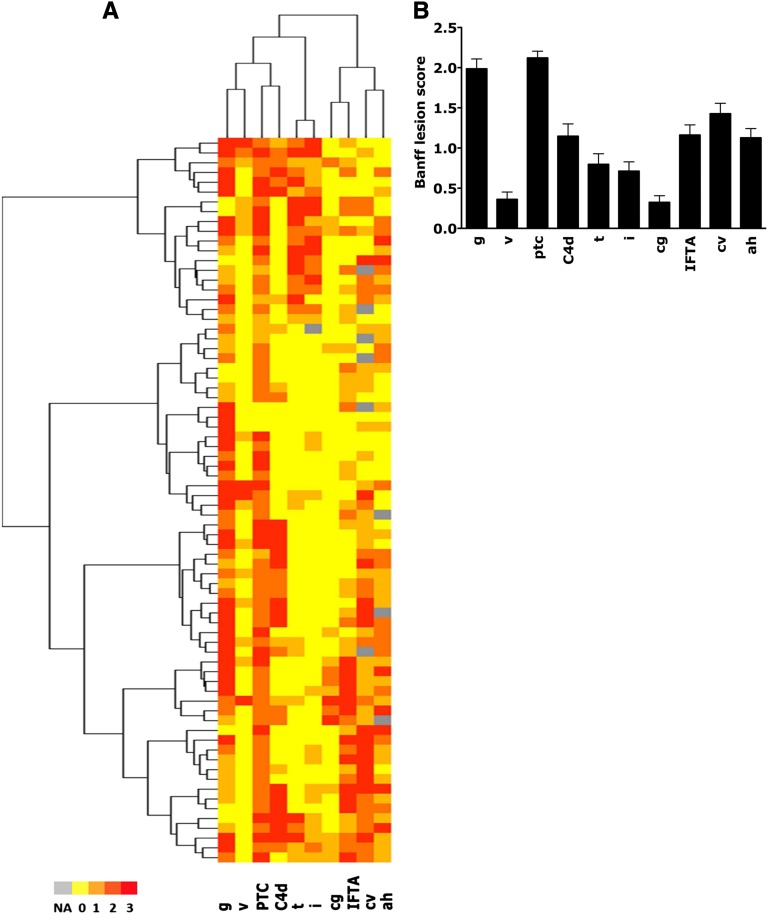

By histology, all 74 biopsies at the time of diagnosis of ABMR showed intense microvascular inflammation, with a mean glomerulitis (g) score of 1.9±1.1 and mean peritubular capillary inflammation (ptc) score of 2.1±0.7. The complement split product C4d deposition in the peritubular capillaries was present in 34 of 74 patients (45.9%). At the time of diagnosis, 46 of 74 (62.2%) kidneys had some atrophy-fibrotic lesions. Of 68 patients with arteries suitable for analysis, 52 patients (76.4%) had evidence of fibrous intimal thickening in the small arteries (arteriosclerosis), with 21 cases (30.8%) being moderate or severe arteriosclerosis (cv Banff score≥2). Figure 1 depicts the kidney allograft histopathology at the time of rejection. The immunodominant DSA at the time of biopsy-proven ABMR was class I in 26 of 74 patients (35.1%) and class II in 48 of 74 patients (64.9%), with a mean class I or II DSA MFImax of 3859±471.

Figure 1.

Kidney allograft histopathology at the time of rejection showing the distribution of graft injury lesions in the overall cohort of patients with ABMR. Note that all patients have intense microcirculation injury. Heat map is colored by thresholds representing (A) the histologic characteristics of patients with ABMR and (B) the mean Banff scores. ah, arteriolar hyalinosis; C4d, complement split product; cg, transplant glomerulopathy; cv, arterial fibrous intimal thickening score; g, glomerulitis; i, interstitial inflammation score; IFTA, interstitial fibrosis–tubular atrophy; ptc, peritubular capillary; t, tubulitis score; v, vasculitis.

Gene Expression Assessment in Patients with Acute ABMR

We compared the molecular phenotype with the conventional parameters (Table 2). The ABMR Molecular Score and endothelial DSA-selective transcripts correlated strongly with each other (r=0.74, P<0.001) and with the natural killer (NK) transcripts (r=0.84, P<0.001). The ABMR Molecular Score correlated with the level of circulating DSA at the time of ABMR diagnosis (r=0.44, P=0.01) and with C4d deposition within the peritubular capillaries (r=0.33, P=0.01). The endothelial DSA-selective transcripts showed correlations with the transplant glomerulopathy (cg) score (r=0.24, P=0.04) and mesangial matrix expansion (r=0.29, P=0.04). There was little correlation between the ABMR Molecular Score or the endothelial DSA-selective transcripts and histologic lesions showing microvascular inflammation and interstitial inflammation or tubulitis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Molecular microscope results at the time of rejection and correlations with concurrent clinical, histologic, and immunologic parameters

| Parameters | ABMR Molecular Score | Endothelial DSA-Selective Transcripts |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical parameters | ||

| eGFR at time of biopsy, µmol/L | 0.002 | 0.009 |

| Proteinuria at the time of biopsy, g/L | 0.030 | 0.076 |

| Immunologic parameters | ||

| Class II or I DSA MFImax at the time of rejection | 0.442a | 0.273b |

| Histologic parameters | ||

| g score | 0.036 | 0.030 |

| ptc score | 0.171 | 0.207 |

| Interstitial inflammation score | −0.087 | −0.031 |

| Tubulitis score | −0.227 | −0.094 |

| Interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy score | 0.247b | 0.119 |

| Arterial fibrous intimal thickening score | 0.112 | −0.084 |

| cg score | 0.135 | 0.242b |

| Mesangial matrix expansion score | 0.254b | 0.287b |

| C4d deposition in graft capillaries (C4d Banff score) | 0.328b | 0.181 |

| Humoral histologic score (g+ptc+v+cg+C4d) | 0.069 | 0.163 |

| Molecular parameters | ||

| ABMR Molecular Score | 1.000 | 0.737a |

| Endothelial DSA-selective transcripts | 0.737a | 1.000 |

| NK transcripts | 0.841a | 0.613a |

| T-cell transcripts | 0.123 | 0.172 |

| AKI score | 0.171 | 0.125 |

P<0.01 (Spearman correlations with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons).

P<0.05 (Spearman correlations with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons).

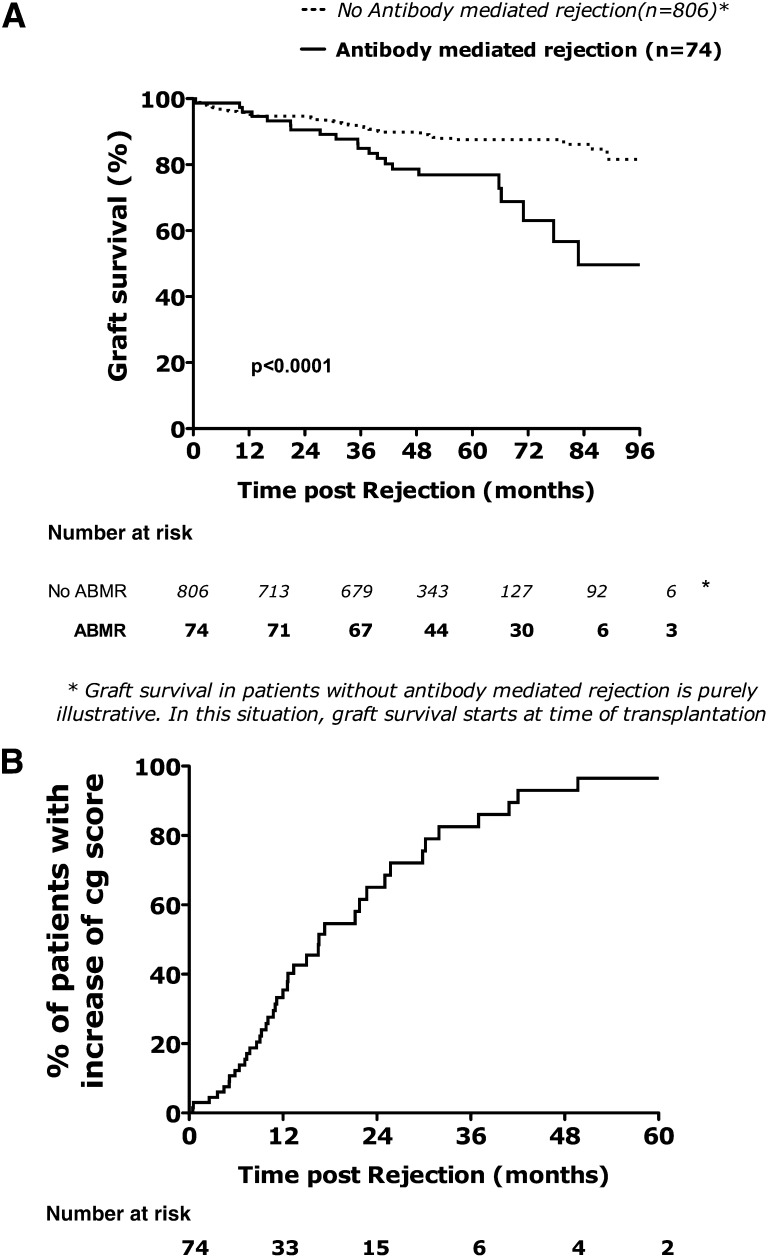

Determinants of Kidney Allograft Loss

Twenty-one kidneys failed after a median follow-up post-ABMR diagnosis of 54 (IQR=38–66) months. Death-censored graft survival was 90.5%, 63.0%, and 49.6% at 2, 6, and 8 years, respectively, after the diagnosis of ABMR (Figure 2A). Univariate Cox analysis of the conventional features (Table 3) showed that the donor age, eGFR at the time of ABMR diagnosis, interstitial fibrosis–tubular atrophy scores, cg score, and C4d deposition were significantly associated with kidney transplant loss. The humoral histologic score was also associated with increased risk of graft loss. The molecular parameters associated with failure were the ABMR Molecular Score and endothelial DSA-selective transcripts. The T-cell burden score and the AKI score (injury-repair response associated transcript) were not associated with risk of allograft loss.

Figure 2.

(A) Time to kidney transplant loss and (B) time to the progression of cg lesions after ABMR.

Table 3.

Determinants of kidney transplant graft outcome after acute ABMR: univariate analysis

| Parameters | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical parameters | |||

| Recipient age, yr | 1.02 | 0.98 to 1.06 | 0.31 |

| Cold ischemia time, min | 1.01 | 0.97 to 1.05 | 0.71 |

| Donor age, yr | |||

| <60 | 1 | — | |

| ≥60 | 3.58 | 1.45 to 8.87 | 0.01 |

| Proteinuria at biopsy, g/L | |||

| <0.15 | 1 | — | |

| ≥0.15 | 1.52 | 0.82 to 2.81 | 0.18 |

| Immunologic parameters | |||

| Immunodominant DSA MFI at the time of rejection | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.42 |

| Functional parameters | |||

| eGFRa at 1 yr | |||

| eGFR≥30 | 1 | — | |

| eGFR<30 | 3.04 | 1.28 to 7.22 | 0.01 |

| Histologic parameters | |||

| Arterial fibrous intimal thickening score | 0.96 | 0.64 to 1.44 | 0.86 |

| cg score | 1.85 | 1.18 to 2.90 | 0.01 |

| Interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy score | 1.84 | 1.21 to 2.78 | 0.01 |

| Interstitial inflammation score | 0.75 | 0.45 to 1.24 | 0.26 |

| Tubulitis score | 0.66 | 0.39 to 1.11 | 0.12 |

| v scoreb | 1.20 | 0.45 to 3.08 | 0.13 |

| g score | 1.45 | 0.89 to 2.35 | 0.13 |

| ptc score | 1.99 | 0.97 to 4.07 | 0.06 |

| C4d Banff score | 1.47 | 1.03 to 2.08 | 0.03 |

| Humoral histologic scorec | 1.36 | 1.08 to 1.71 | 0.01 |

| Molecular parameters | |||

| ABMR Molecular Score | 8.82 | 1.82 to 42.73 | 0.01 |

| Endothelial DSA-selective transcripts | 2.94 | 1.00 to 8.69 | 0.05 |

| NK transcripts | 1.61 | 0.81 to 3.22 | 0.18 |

| T-cell transcripts | 0.93 | 0.50 to 1.73 | 0.83 |

| AKI score | 1.17 | 0.63 to 2.18 | 0.61 |

eGFR using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula.

Note that all ABMR episodes with v lesions in the present study were treated by antibody-targeting strategies.2

Humoral histologic score defined by g+ptc+v+cg+C4d Banff scores.

In the multivariate Cox model, the factors independently associated with graft loss were certain conventional features (donor age, the humoral histologic score [g+ptc+vasculitis (v) score+cg+C4d], and the ABMR molecular score [hazard ratio (HR), 2.22; 95% confidence interval (95% CI), 1.37 to 3.58; P=0.001]) (Table 4) and the endothelial DSA-selective transcripts (HR, 3.02; 95% CI, 1.0 to 9.16; P<0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Determinants of kidney transplant graft outcome after acute ABMR (multivariate models) using the ABMR Molecular Score and endothelial DSA-selective transcripts

| Parameters | Number of Patients | Number of Events | HR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 with ABMR Molecular Score | |||||

| Donor age, yr | |||||

| <60 | 54 | 11 | 1 | — | — |

| ≥60 | 20 | 10 | 3.84 | 1.48 to 9.96 | 0.01 |

| eGFRa (ml/min) at the time of rejection | |||||

| ≥30 | 52 | 10 | 1 | ||

| <30 | 22 | 11 | 1.74 | 0.70 to 4.35 | 0.23 |

| Humoral histologic score (g+ptc+v+cg+C4d) | 74 | 21 | 1.43 | 1.09 to 1.90 | 0.01 |

| ABMR Molecular Score | 74 | 21 | 2.22 | 1.37 to 3.58 | 0.001 |

| Model 2 with endothelial DSA-selective transcripts | |||||

| Donor age, yr | |||||

| <60 | 54 | 11 | 1 | — | — |

| ≥60 | 20 | 10 | 3.03 | 1.16 to 7.90 | 0.02 |

| eGFRa (ml/min) at the time of rejection | |||||

| ≥30 | 52 | 10 | 1 | ||

| <30 | 22 | 11 | 2.07 | 0.74 to 5.84 | 0.17 |

| Humoral histologic score (g+ptc+v+cg+C4d) | 74 | 21 | 1.22 | 0.94 to 1.60 | 0.14 |

| Endothelial DSA-selective transcripts | 74 | 21 | 3.02 | 1.00 to 9.16 | <0.05 |

eGFR using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula.

Determinants of Progression to Chronic Allograft Injury

This analysis integrated the follow-up biopsies performed after the initial diagnosis of ABMR. At 1 and 2 years after ABMR, 35% and 68% of patients had an increase of cg lesions defined by an increase of cg Banff score≥1 (Figure 2B).

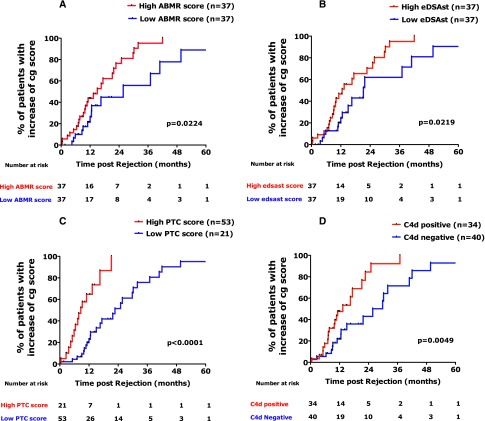

The median time to cg Banff score increase was 16.6 months after the initial diagnosis of ABMR. Kaplan–Meier analysis shows that the ABMR molecular score, endothelial DSA-selective transcripts, peritubular capillaritis score, and C4d deposition were associated with the time to increase of cg lesions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Time of progression of cg lesions after acute ABMR according to (A) ABMR Molecular Score, (B) endothelial DSA-selective transcripts, (C) ptc Banff score, and (D) C4d deposition in the peritubular capillaries. Progression of transplant glomerulopathy lesions is defined by increase of cg Banff score≥1. High and low ABMR Molecular Scores and the endothelial DSA-selective transcripts were defined using the median values for the ABMR and endothelial DSA-selective transcripts as thresholds. A high ptc score was defined by a ptc Banff score≥2 compared with a low ptc score (<2). C4d staining was graded from zero to three by the percentage of ptc having linear staining, with grades 2 or 3 considered to be positive. eDSAst, endothelial DSA-selective transcripts.

Additive Value of the Molecular Microscope for Predicting Kidney Allograft Loss

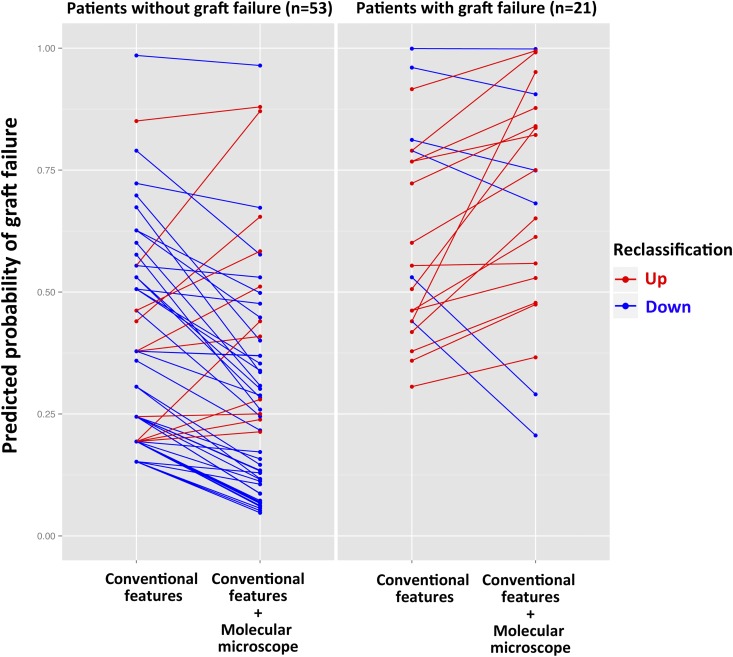

The inclusion of the ABMR molecular score in the reference model was found to significantly improve the discriminative ability of the model (i.e., its capacity to discriminate between patients who have lost their graft and patients who have not), because the C statistic increased significantly from 0.77 to 0.81 (bootstrap mean difference=0.0496505; 95% CI, 0.0473 to 0.0519). Similarly, the inclusion of the ABMR molecular score in the reference model adequately reclassified patients at lower (no events) or higher (events) risk of graft loss, which was shown by a continuous net reclassification index of 1.0135 (95% CI, 0.57 to 1.46; P<0.001). The addition of the molecular microscope reclassified 42 of 53 patients (79.2%) in the right direction in the no event group, whereas it reclassified 15 of 21 patients (71.4%) in the event group (graft loss) (Figure 4). The integrated discrimination improvement was 0.1579 (P<0.001).

Figure 4.

Additive value of the molecular microscope (ABMR Molecular Score) for reclassification of risk of allograft failure (continuous net reclassification improvement). Blue lines in patients without graft failure indicate that the molecular microscope moved risk prediction in the correct (downward) direction (42/53=79.2%). Conversely, red lines in patients with graft failure indicate a correct (upward) change in risk assessment when using the molecular microscope (15/21=71.4%).

These analyses show that the addition of the ABMR Molecular Score to kidney biopsies improved the stratification of patients at risk for graft failure.

External Validation

The external validation cohort was composed of 321 kidney recipients transplanted at Saint Louis Hospital between January 1, 2006, and January 1, 2010, with 54 who had biopsy-proven early ABMR with suitable material for microarray analysis. The baseline characteristics and immunologic characteristics for the validation set are detailed in Supplemental Table 4. The median follow-up time after transplantation was 54.5 (IQR=42–69) months. Both the ABMR Molecular Score and endothelial DSA-selective transcripts were independently associated with graft loss (HR, 4.45; 95% CI, 1.01 to 19.95; P=0.05 for the ABMR Molecular Score [Supplemental Table 5A] and HR, 6.68; 95% CI, 1.36 to 32.93; P=0.02 for the endothelial DSA-selective transcripts [Supplemental Table 5B]).

Discussion

In a carefully phenotyped population of kidney recipients with early biopsy-proven ABMR, we assessed the use of transcript measurement for the molecular interrogation of biopsies. Compared with the traditional approach for predicting graft loss, which is based only on histology and the presence of donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies, the new approach, which combines the traditional approach with gene expression profiling in the kidney allografts, provides a more accurate prediction of graft loss.

Molecular phenotyping of kidney transplant biopsies has provided clues as to the mechanisms of disease independent of conventional assessments. The lack of correlation of the ABMR Molecular Score or endothelial DSA-selective transcripts with the conventional features and the independent correlations of these molecular data with the outcomes establish an independent value for molecular phenotyping in risk assessment, most likely because the ABMR Molecular Score and endothelial DSA-selective transcripts set reflects a change in the microcirculatory endothelium that conventional assessments cannot detect.

Our study is the first to examine the risk of graft loss in a large population of early ABMR patients with extensive follow-up and standardized management using an FDA-approved therapeutic strategy,14 in which we used contemporary tools for precise allograft phenotyping together with a systematic gene expression assessment in the allograft to represent the full spectrum of ABMR. The present study used a model of early disease using a very high-risk cohort with early ABMR, which led us to focus on the disease progression related to ongoing humoral process without interference with superimposed diseases seen in late ABMR cases.11,15

This paper shows the predictive performance of the molecular microscope inside the ABMR disease, where all patients have stereotypical histologic presentation and all have anti-HLA antibodies. We are not using the molecular microscope to confirm the ABMR diagnosis, which has been the subject of previous works,11,15 but, rather, address a major clinical problem of how to stratify the risk in individuals with early ABMR (i.e., inside the disease).

We used, in the present study, a methodological approach16 for the reclassification, discrimination, and performance analyses to evaluate the benefit of the molecular microscope system over conventional tools, showing a net individual benefit of the molecular microscope approach when added to the conventional features. Conventional assessment permits to diagnose ABMR but is insufficient for prediction of outcome and risk assessment in patients with ABMR.17

Our hypothesis is that the ABMR Molecular Score and the endothelial transcripts reflect active remodeling of the microcirculation because of relatively recent antibody-mediated damage, implying the action of the antibody and its effector mechanism, and thus, can be used as a companion to the conventional features, such as histopathology. The ABMR Molecular Score is the weighted average of a larger set of genes selected using a simple t test comparing two classes of biopsies and then fine tuned using linear discriminant analysis, whereas the endothelial DSA-selective transcripts score is the unweighted average of a gene set selected using domain-specific knowledge of transplant biology. The overlap in these gene sets reflects the convergence of the methods on a similar biology and highlights the important, but not exclusive, participation of antibody-mediated endothelial activation.

This study reinforces the notion that the classic histologic activity criteria including g, capillaritis, C4d, and endarteritis, which are part of the diagnostic criteria of ABMR, may not be as accurate for stratifying the risk inside the disease. This situation clearly differs from the comparison of sick versus well (ABMR versus everything else), where these parameters are consistently and strongly associated with increased risk of graft loss.

In our study, we found weak correlation between the ABMR Molecular Score or the endothelial DSA-selective transcripts and histologic lesions showing microvascular inflammation (Table 2) and found that ABMR patients with similar histopathology may show different levels of molecular signals, reflecting distinct activity and disease state. In addition, we show that, beyond a humoral histologic score defined by g+ptc+v+cg+C4d Banff score, the molecular microscope assessment brings independent risk prediction and additional value for individual risk reclassification (Figure 4, Table 4).

Although there are no doubts about the unmet medical need for improved diagnostics to allow a more personalized approach to therapy after kidney transplantation, our results go far beyond, bringing a new dimension to diagnosis and risk prediction in other solid organ transplants, such as heart, lung, small bowel, pancreas, and composite tissue. The ability of the ABMR Molecular Score and endothelial transcript measurements to reflect the risk of progression may be warranted for the development of therapeutic strategies that respond to the disease activity and stage.

Our study also has some limitations. It was not designed to determine the potential of the molecular microscope system to monitor the response to therapy. This aim would require additional investigations. Although our study was conducted using a reference platform for gene expression studies (Transplant Applied Diagnostic Centre in Alberta) with 10 years of experience with gene expression in the kidneys, established validation procedures, and a powerful biostatistical platform, multigene testing is strictly quantitative and requires normalization against the results of a standard population; it requires the tests to be conducted by a centralized reading service rather than local pathology laboratories, because a specific numerical value must be interpreted with respect to a defined reference set population. Although this model has its drawbacks, central testing and comparison with a reference set have enabled molecular testing in cancer biopsies to offer new insights into prognosis.7–9 Finally, the costs of microarrays are rapidly dropping; nevertheless, it would be premature to determine whether the molecular microscope strategy is cost-effective until proper pharmacoeconomical studies are done.

The assessment of gene expression in kidney allograft transplant rejection seems to be useful in identifying patients with a high risk for kidney allograft loss. The molecular microscope system provides insight beyond the classic, histology-based approach and allows for risk stratification that may guide clinical management and clinical trials in transplant medicine.

Concise Methods

Participants

From 939 patients who underwent single kidney transplantation at Necker Hospital between January of 2004 and October of 2010, we identified 101 patients (10.7%) with a diagnosis of biopsy-proven ABMR in the first 1 year post-transplant; 27 patients were excluded because of a lack of suitable material for microarray analysis (14 patients had material that did not provide sufficient quality to run microarray and 13 patients did not have extracore performed at the time of diagnosis) (Supplemental Table 1), leaving 74 patients with ABMR as the study sample.

We used an additional independent validation sample of 321 patients who underwent kidney transplantation at Saint Louis Hospital between January 1, 2006, and January 1, 2010. Of these patients, 54 patients (16.8%) had early biopsy-proven ABMR with suitable material for microarray analysis (Supplemental Material). The patients were followed until April 15, 2013.

All of the transplants were ABO-compatible and had current negative IgG T-cell and B-cell complement-dependent cytotoxicity cross-matching at the time of transplantation. The study was approved by the institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from all study patients (registration number 1016618).

Clinical Data

Clinical data for the donors and recipients in the development (Necker Hospital) and validation (Saint Louis Hospital) cohorts were obtained from two national registries, the Données Informatiques Validées en Transplantation (Necker Hospital) and the Agence de la Biomédecine (Saint Louis Hospital), in which data are prospectively entered at specific time points for each patient (0 days, 6 months, and 1 year post-transplantation) and updated annually thereafter18,19 (Supplemental Material). The development and validation cohort data were retrieved from the database on April 15, 2012.

We recorded the data for all patients with ABMR, which was defined as the association of deterioration in function or impaired function and histopathological lesions according to consensus rules represented by the international Banff classification criteria.20 We acknowledged C4d-negative ABMR for patients with histologic evidence of ABMR and the presence of circulating DSA.21

Patients with ABMR received methylprednisolone pulses (500 mg/d for 3 days) and high-dose intravenous Ig (2 g/kg per week for three rounds). Patients on cyclosporine were switched to tacrolimus. In addition, patients received four plasmapheresis cycles and two weekly doses of rituximab (375 mg/m2 body surface area; MabThera; Roche, Meylan, France). The treatment of ABMR episodes was standardized between the centers. The outcomes measured in this study were graft loss defined as the return to dialysis and progression of cg defined as the increase of Banff cg score by optical microscopy of kidney allografts.

Patients with ABMR were retrospectively reassessed for the conventional diagnosis criteria with review of histology and immunochemistry for C4d and identification of circulating donor-specific anti-HLA antibodies on sera saved at time of biopsies as well as microarray-based gene expression in allograft biopsies. In addition to the biopsies at the time of ABMR diagnosis, we determined the time to increase of cg score using 178 follow-up biopsies performed after the diagnosis of ABMR in the development cohort; cg score was defined by the duplication of the basement membrane according to Banff classification.20,22 Electron microscopy was not performed in the present study.

All biopsies were reviewed by two renal pathologists blinded to the clinical information. The biopsies were graded from zero to three according to the Banff20,22 histologic parameters: g, tubulitis, interstitial inflammation, endarteritis, ptc, cg, interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, arterial fibrous intimal thickening, and arteriolar hyaline thickening. C4d staining was performed by immunohistochemistry on paraffin sections using the human C4d polyclonal antibody (Biomedica Gruppe, Austria).23 C4d staining was graded from zero to three by the percentage of peritubular capillaries with linear staining, and grades 2 and 3 were considered to be positive. We integrated humoral parameters (g, ptc, v, cg, and C4d) in a humoral histologic score defined by the sum of these variables.

Presence of circulating DSA at the time of transplantation (day 0) and the time of biopsy was analyzed using single-antigen flow bead assays (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA) on the Luminex platform as previously detailed.24 Beads showing a normalized mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) higher than 500 were considered positive. For each patient, we recorded the number, class, specificities, and MFI of all donor-specific HLA antibodies. The maximum MFI for the DSA (DSA MFImax) was defined as the highest ranked donor-specific bead. HLA typing of donors and recipients was performed using DNA typing (Innolipa HLA Typing Kit; Innogenetics, Belgium).

RNA Extraction and Microarrays Analyses

An additional 16-gauge biopsy core was obtained at the time of the biopsy and stored at −80°C in ornithine carbamyl transferase for gene expression analysis. All available biopsies performed at the time of the ABMR diagnosis were processed for microarray analysis as described previously.25 RNA extraction, labeling, and hybridization to the HG_U133_Plus_2.0 GeneChip (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The microarrays were scanned using the Gene Array Scanner (Affymetrix) and processed with GeneChip Operating Software Version 1.4.0 (Affymetrix). The microarray expression files are posted on the Gene Expression Omnibus website under the accession number GSE36059.

The microarray data files for 126 biopsies were processed using Robust Multiarray Analysis in Bioconductor.10 The molecular characteristics of the biopsies used pathogenesis-based transcript sets (PBTs) that reflect biologic processes of known relevance for the pathogenesis of renal inflammation and injury in transplants. Here, we applied the following PBTs: the ABMR Molecular Score12 and endothelial DSA-selective transcripts.26,27 The top genes for the ABMR Molecular Score and endothelial DSA-selective transcripts include many endothelial transcripts (e.g., DARC, VWF, and ROBO4), NK transcripts, IFN-γ production and inducing transcripts (e.g., CXCL11), and cytotoxicity-related transcripts (e.g., granulysin26 and FGFBP228), which are summarized in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. In addition, the NK-cell transcript burden,29 T-cell transcript burden,29 and AKI transcripts13 were evaluated. The information on the probe sets and the algorithms for PBT generation are available at http://www.atagc.med.ualberta.ca/Research/GeneLists/Pages/default.aspx.

Statistical Analyses

We provide the mean (SD) values for the description of continuous variables, with the exception of the MFI, for which we use the mean (SEM) because of its wide distribution. We compared the means and proportions of kidney transplant phenotypes using t tests, ANOVAs, and chi-squared tests (or Fisher’s exact tests if appropriate). A Cox proportional hazard model was used to quantify the HRs and 95% CIs for the factors associated with kidney graft loss. Within each group of factors, we performed univariate and multivariate analyses. The selected factors were entered in a single multivariate Cox model (using P value ≤0.10 as a threshold) to identify the most predictive independent factors for kidney graft loss.

We further focused on the improvement in model performance because of inclusion of ABMR gene expression comparing two sets of predictions of 8-year graft loss risk probability: one set of predictions based on a Cox proportional hazards model without ABMR gene expression and one set of predictions based on a model with ABMR gene expression.

The discrimination ability and incremental value of ABMR gene expression were evaluated by C statistics. This analysis was repeated 1000 times using bootstrap samples to derive 95% CIs for the difference in the C statistic between models.

We also used net reclassification improvement and integrated discrimination improvement to quantify the performance and the net benefit of the addition of ABMR Molecular Score to the reference model.30,31

The proportionality assumption for the Cox model was verified using the log graphic method. The association between the molecular features and kidney transplant survival was subsequently replicated and confirmed in the independent validation sample.

The analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS, Cary, NC). All of the tests were two-sided, and P values <0.05 were regarded as significant.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France II. Each patient from the present study has given written informed consent to be included in the French national registry agency (Agence de la Biomédecine) databases CRISTAL (https://www.sipg.sante.fr/portail/) and DIVAT (https://www.divat.fr). The Données informatisées Validées en Transplantation (DIVAT) and CRISTAL database networks have been approved by the National French Commission for bioinformatics data and patients liberty: DIVAT: CNIL, registration number 1016618, validated June 8, 2004; CRISTAL: CNIL, registration number 363505, validated April 3, 1996.

Disclosures

P.F.H. has shares in TSI, a company with an interest in molecular diagnostics; the other authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Vido Ramassar and Anna Hutton for excellent technical support. We thank Juliane Posson for data retrieval and Jerôme Verine from Saint Louis Hospital “Tumorothèque” for providing Hôpital Saint Louis samples. We thank the members of the Laboratory of Excellence, Transplantex for helpful discussions.

This research is supported by funding and/or resources from Novartis Pharma France and Canada and Astellas France. In the past, research was supported by Genome Canada, the University of Alberta Hospital Foundation, Roche Molecular Systems, Hoffmann-La Roche Canada Ltd., the Alberta Ministry of Advanced Education and Technology, the Roche Organ Transplant Research Foundation, and Astellas. P.F.H. held a Canada Research Chair in Transplant Immunology until 2008 and currently holds the Muttart Chair in Clinical Immunology.

The authors declare no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationships or activities that could seem to have influenced the submitted work. All authors, external and internal, had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2013111149/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Garcia GG, Harden P, Chapman J, World Kidney Day Steering Committee 2012 : The global role of kidney transplantation. Lancet 379: e36–e38, 2012. 22405254 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lefaucheur C, Loupy A, Vernerey D, Duong-Van-Huyen JP, Suberbielle C, Anglicheau D, Vérine J, Beuscart T, Nochy D, Bruneval P, Charron D, Delahousse M, Empana JP, Hill GS, Glotz D, Legendre C, Jouven X: Antibody-mediated vascular rejection of kidney allografts: A population-based study. Lancet 381: 313–319, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Einecke G, Sis B, Reeve J, Mengel M, Campbell PM, Hidalgo LG, Kaplan B, Halloran PF: Antibody-mediated microcirculation injury is the major cause of late kidney transplant failure. Am J Transplant 9: 2520–2531, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaston RS, Cecka JM, Kasiske BL, Fieberg AM, Leduc R, Cosio FC, Gourishankar S, Grande J, Halloran P, Hunsicker L, Mannon R, Rush D, Matas AJ: Evidence for antibody-mediated injury as a major determinant of late kidney allograft failure. Transplantation 90: 68–74, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nankivell BJ, Alexander SI: Rejection of the kidney allograft. N Engl J Med 363: 1451–1462, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montgomery RA, Lonze BE, King KE, Kraus ES, Kucirka LM, Locke JE, Warren DS, Simpkins CE, Dagher NN, Singer AL, Zachary AA, Segev DL: Desensitization in HLA-incompatible kidney recipients and survival. N Engl J Med 365: 318–326, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartmann S, Gerber B, Elling D, Heintze K, Reimer T: The 70-gene signature as prognostic factor for elderly women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel) 7: 19–24, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed SD, Lyman GH: Cost effectiveness of gene expression profiling for early stage breast cancer: A decision-analytic model. Cancer 118: 6298–6299, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prat A, Parker JS, Fan C, Cheang MC, Miller LD, Bergh J, Chia SK, Bernard PS, Nielsen TO, Ellis MJ, Carey LA, Perou CM: Concordance among gene expression-based predictors for ER-positive breast cancer treated with adjuvant tamoxifen. Ann Oncol 23: 2866–2873, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeve J, Sellarés J, Mengel M, Sis B, Skene A, Hidalgo L, de Freitas DG, Famulski KS, Halloran PF: Molecular diagnosis of T cell-mediated rejection in human kidney transplant biopsies. Am J Transplant 13: 645–655, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halloran PF, Pereira AB, Chang J, Matas A, Picton M, De Freitas D, Bromberg J, Serón D, Sellarés J, Einecke G, Reeve J: Microarray diagnosis of antibody-mediated rejection in kidney transplant biopsies: An international prospective study (INTERCOM). Am J Transplant 13: 2865–2874, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sellarés J, Reeve J, Loupy A, Mengel M, Sis B, Skene A, de Freitas DG, Kreepala C, Hidalgo LG, Famulski KS, Halloran PF: Molecular diagnosis of antibody-mediated rejection in human kidney transplants. Am J Transplant 13: 971–983, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Famulski KS, de Freitas DG, Kreepala C, Chang J, Sellares J, Sis B, Einecke G, Mengel M, Reeve J, Halloran PF: Molecular phenotypes of acute kidney injury in kidney transplants. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 948–958, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Archdeacon P, Chan M, Neuland C, Velidedeoglu E, Meyer J, Tracy L, Cavaille-Coll M, Bala S, Hernandez A, Albrecht R: Summary of FDA antibody-mediated rejection workshop. Am J Transplant 11: 896–906, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sellarés J, de Freitas DG, Mengel M, Reeve J, Einecke G, Sis B, Hidalgo LG, Famulski K, Matas A, Halloran PF: Understanding the causes of kidney transplant failure: The dominant role of antibody-mediated rejection and nonadherence. Am J Transplant 12: 388–399, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr., Steyerberg EW: Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med 30: 11–21, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefaucheur C, Nochy D, Hill GS, Suberbielle-Boissel C, Antoine C, Charron D, Glotz D: Determinants of poor graft outcome in patients with antibody-mediated acute rejection. Am J Transplant 7: 832–841, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Données Informatiques Validées en Transplantation (DIVAT): Available at: http://www.divat.fr/ Accessed April 15, 2012

- 19.Agence Biomédecine: Cristal. Available at: http://www.sipg.sante.fr/portail/ Accessed April 15, 2012

- 20.Sis B, Mengel M, Haas M, Colvin RB, Halloran PF, Racusen LC, Solez K, Baldwin WM, 3rd, Bracamonte ER, Broecker V, Cosio F, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg C, Einecke G, Gloor J, Glotz D, Kraus E, Legendre C, Liapis H, Mannon RB, Nankivell BJ, Nickeleit V, Papadimitriou JC, Randhawa P, Regele H, Renaudin K, Rodriguez ER, Seron D, Seshan S, Suthanthiran M, Wasowska BA, Zachary AA, Zeevi A: Banff ’09 meeting report: Antibody mediated graft deterioration and implementation of Banff working groups. Am J Transplant 10: 464–471, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haas M, Sis B, Racusen LC, Solez K, Glotz D, Colvin RB, Castro MC, David DS, David-Neto E, Bagnasco SM, Cendales LC, Cornell LD, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Farver CF, Farris AB, 3rd, Gibson IW, Kraus E, Liapis H, Loupy A, Nickeleit V, Randhawa P, Rodriguez ER, Rush D, Smith RN, Tan CD, Wallace WD, Mengel M, the Banff Meeting Report Writing Committee : Banff 2013 meeting report: Inclusion of c4d-negative antibody-mediated rejection and antibody-associated arterial lesions. Am J Transplant 14: 272–283, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mengel M, Sis B, Haas M, Colvin RB, Halloran PF, Racusen LC, Solez K, Cendales L, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Farver CF, Rodriguez ER, Wallace WD, Glotz D, Banff Meeting Report Writing Committee : Banff 2011 Meeting report: New concepts in antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant 12: 563–570, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loupy A, Hill GS, Suberbielle C, Charron D, Anglicheau D, Zuber J, Timsit MO, Duong JP, Bruneval P, Vernerey D, Empana JP, Jouven X, Nochy D, Legendre CH: Significance of C4d Banff scores in early protocol biopsies of kidney transplant recipients with preformed donor-specific antibodies (DSA). Am J Transplant 11: 56–65, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lefaucheur C, Loupy A, Hill GS, Andrade J, Nochy D, Antoine C, Gautreau C, Charron D, Glotz D, Suberbielle-Boissel C: Preexisting donor-specific HLA antibodies predict outcome in kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1398–1406, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mueller TF, Einecke G, Reeve J, Sis B, Mengel M, Jhangri GS, Bunnag S, Cruz J, Wishart D, Meng C, Broderick G, Kaplan B, Halloran PF: Microarray analysis of rejection in human kidney transplants using pathogenesis-based transcript sets. Am J Transplant 7: 2712–2722, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hidalgo LG, Sis B, Sellares J, Campbell PM, Mengel M, Einecke G, Chang J, Halloran PF: NK cell transcripts and NK cells in kidney biopsies from patients with donor-specific antibodies: Evidence for NK cell involvement in antibody-mediated rejection. Am J Transplant 10: 1812–1822, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sis B, Jhangri GS, Bunnag S, Allanach K, Kaplan B, Halloran PF: Endothelial gene expression in kidney transplants with alloantibody indicates antibody-mediated damage despite lack of C4d staining. Am J Transplant 9: 2312–2323, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogawa K, Tanaka K, Ishii A, Nakamura Y, Kondo S, Sugamura K, Takano S, Nakamura M, Nagata K: A novel serum protein that is selectively produced by cytotoxic lymphocytes. J Immunol 166: 6404–6412, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hidalgo LG, Sellares J, Sis B, Mengel M, Chang J, Halloran PF: Interpreting NK cell transcripts versus T cell transcripts in renal transplant biopsies. Am J Transplant 12: 1180–1191, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steyerberg EW: Clinical Prediction Models: A Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and Updating, 1st Ed., New York, Springer Science + Business Media, LLC, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB: Overall C as a measure of discrimination in survival analysis: Model specific population value and confidence interval estimation. Stat Med 23: 2109–2123, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.