Summary

This study identified PKCα as a new target of miR-200b showing that miR-200b suppresses TNBC metastasis by targeting PKCα. It provided mechanistic insights for observed high PKCα levels in metastatic TNBC suggesting that miR-200b/PKCα represent promising targets for metastatic TNBC.

Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive subtype of breast cancer with poor prognosis and lacks effective targeted therapies. The microRNA-200 (miR-200) family is found to inhibit or promote breast cancer metastasis; however, the underlying mechanism is not well understood. This study was performed to investigate the effect and mechanism of miR-200b on TNBC metastasis and identify targets for developing more efficient treatment for TNBC. We found that miR-200 family expression levels are significantly lower in highly migratory TNBC cells and metastatic TNBC tumors than other types of breast cancer cells and tumors. Ectopically expressing a single member (miR-200b) of the miR-200 family drastically reduces TNBC cell migration and inhibits tumor metastasis in an orthotopic mouse mammary xenograft tumor model. We identified protein kinase Cα (PKCα) as a new direct target of miR-200b and found that PKCα protein levels are inversely correlated with miR-200b levels in 12 kinds of breast cancer cells. Inhibiting PKCα activity or knocking down PKCα levels significantly reduces TNBC cell migration. In contrast, forced expression of PKCα impairs the inhibitory effect of miR-200b on cell migration and tumor metastasis. Further mechanistic studies revealed that PKCα downregulation by miR-200b results in a significant decrease of Rac1 activation in TNBC cells. These results show that loss of miR-200b expression plays a crucial role in TNBC aggressiveness and that miR-200b suppresses TNBC cell migration and tumor metastasis by targeting PKCα. Our findings suggest that miR-200b and PKCα may serve as promising therapeutic targets for metastatic TNBC.

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a unique subtype of breast cancer that is histologically defined by the absence of the estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and lack of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her2) overexpression (1,2). TNBC is often a highly invasive and metastatic form of breast cancer with an overall poorer prognosis compared with other breast cancer subtypes. This is partly due to TNBC usually displaying more aggressive behavior and lacking effective targeted therapies (3,4). Chemotherapy is currently the only treatment option for metastatic TNBC and is only effective at the initial treatment stage (5,6). There is an urgent need to better understand the underlying mechanism of TNBC aggressive behavior and identify novel targets for developing more efficient therapies for TNBC.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a large class of small non-coding RNAs and regulate gene expression through binding to the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of their target mRNAs, resulting in mRNA degradation or translation inhibition (7,8). miRNAs are found to be critically involved in many fundamental processes of cancer (8,9), although the underlying mechanisms have not been well understood for the majority of miRNAs. In breast cancer, miRNAs are shown to affect cancer cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, migration, invasion and metastasis (10–12). However, fewer studies on the role of miRNAs in TNBC have been done compared with other breast cancer subtypes. Further studying miRNA function in TNBC may lead to identification of novel therapeutic targets for TNBC.

Human miRNA-200 (miR-200) family consists of five members divided into two groups: the miR-200b/-200a/-429 group located on chromosome 1 and the miR-200c/-141 group located on chromosome 12 (13,14). Alternatively, the miR-200 family can be classified into two functional clusters based on the identities of their seed sequences: the miR-200b/-c/-429 cluster and the miR-200a/-141 cluster. The miR-200 family members are among the first miRNAs reported to function as potent inhibitors of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and as regulators of epithelial plasticity of cancer by directly targeting EMT-inducing transcription factors zinc-finger E-box-binding homeobox factor 1 (ZEB1) and 2 (ZEB2; 15–21). Despite its well-established role in inhibiting EMT (15–19), a process thought to be important in cancer metastasis (22), the effect of miR-200 family on cancer metastasis has been shown to be controversial. Ectopic expression of either one group of miR-200 or the entire miR-200 family in cancer cells is able to suppress (23) or promote cancer metastasis (24,25). Moreover, relatively few studies have been done on the effect of a single member of miR-200 family on cancer metastasis. In addition, the mechanism of miR-200 function has not been well understood and only a limited number of miR-200 target genes that promote cell migration and cancer metastasis have been identified (26–28). It is essential to further investigate the effect of miR-200 family on cancer metastasis and identify their new targets that play crucial roles in cancer metastasis.

Protein kinase Cα (PKCα) is a member of PKC family of serine/threonine kinases containing 10 isozymes, playing important roles in regulating cell migration and cancer metastasis (29,30). Particularly, recent studies revealed that PKCα functions as a central signaling node in breast cancer stem cells and has been proposed to be a valuable therapeutic target for certain breast cancer subtypes (31,32). Moreover, recent studies also showed that high PKCα levels were most commonly detected in high-grade TNBC tumors (32,33). However, little is known about the mechanism of PKCα dysregulation in breast cancer.

In this study, we identified PKCα as a new direct target of miR-200b and showed that miR-200b suppresses TNBC cell migration and metastasis by targeting PKCα, which in turn reduces Rac1 activation. The findings from this study not only provide mechanistic insights for recent observations showing that metastatic TNBC tumors have high PKCα levels, but also suggest that miR-200b and PKCα may serve as promising therapeutic targets for metastatic TNBC.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

MCF-7, T-47D, BT-474, MDA-MB-453, SKBR-3, MDA-MB-468, BT-20, Hs578T and BT-549 cell lines were purchased from and validated by American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). These cells were cultured following instructions from ATCC and used within 6 months of purchases. MDA-MB-231 cells, provided by Dr Suyun Huang (M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX) and authenticated by M.D. Anderson Cancer Center based on short tandem repeats, were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F-12 supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Pen/Strep) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). SUM-149 and SUM-159 cells, obtained from Dr Stephen Ethier (Wayne State University, Detroit, MI) who developed these cell lines, were cultured in F-12 supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 1% Pen/Strep. All cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Quantitative PCR analysis

Cellular total RNAs were extracted using QIAGEN miRNeasy mini kit (Valencia, CA) for quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) analysis, which was carried out in ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System using TaqMan gene expression assays for the miR-200 family (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). U6 snRNA was used to normalize relative miR-200 expression levels as described previously (34).

Generation of miR-200b stably expressing cell lines

Vector control (green fluorescent protein, GFP) and miR-200b stably expressing cells were generated by transducing cells with control (pMIRNA-GFP) or miR-200b precursor-expressing (pMIRNA-GFP-200b) lentiviral particles (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA), respectively, as described previously (34). The miR-200b stably expressing cell clones were selected by Q-PCR analysis of miR-200b levels in clones grown from series dilution culture of cells transduced with miR-200b precursor-expressing lentiviral particles.

Generation of miR-200b and PKCα double stably expressing cells

Human PKCα full-length complementary DNAs lacking the 3′UTR was purchased from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD) and cloned into pLenti6.3⁄V5-DEST™ vector (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Vector control (pLenti6.3) and PKCα-expressing (pLenti6.3-PKCα) lentiviral particles were packaged as described previously (35). To establish vector control, miR-200b and PKCα double stably expressing cells, miR-200b stably expressing cells were transduced with vector control (pLenti6.3) or PKCα-expressing (pLenti6.3-PKCα) lentiviral particles, respectively, and selected with Blasticidin.

Generation of PKCα shRNA stable knockdown cells

Vector control and PKCα stable knockdown cells were generated by transducing cells with control (pLKO.1-puro) or PKCα short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expressing (pLKO.1-puro-PKCα-shRNA) lentiviral particles, respectively. The control and PKCα shRNA lentiviral constructs were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO) and the lentiviral particles were packaged as described previously (35). Cells were transduced with vector control or PKCα shRNA-expressing lentiviral particles and selected with puromycin.

Generation of PKCα 3′UTR luciferase reporter wild-type and mutant-type vectors and dual luciferase reporter assays

A fragment of human PKCα 3′UTR containing nucleotide 1–1825 was synthesized by Blue Heron Biotech (Bothell, WA) and cloned into pMirTarget vector (OriGene Technologies), which served as the wild-type PKCα 3′UTR luciferase vector containing the miR-200b putative binding site. To generate the mutant-type PKCα 3′UTR luciferase vector, the same fragment of PKCα 3′UTR was synthesized with the miR-200b putative binding site completely mutated. The mutated PKCα 3′UTR fragment was similarly cloned into pMirTarget, which served as the mutant-type PKCα 3′UTR luciferase vector. Dual luciferase reporter assays were performed as described previously (34). The relative luciferase reporter activity was calculated as the ratio of the wild-type or mutant-type PKCα 3′UTR firefly luciferase activity divided by the Renilla luciferase activity.

Wound healing and Transwell cell migration assays

Cell migration was determined by a wound healing assay and/or Transwell cell migration assay as described previously (36). A proliferation inhibitor mitomycin C (1 µg/ml) (Sigma) and GO6976 (1 µM) (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol) were added into the medium when the wound was created.

Orthotopic mouse mammary xenograft tumor model studies

Six-week-old female nude mice (Nu/Nu, Charles River Laboratories) were used and maintained under regulated pathogen-free conditions. Animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were anesthetized before injections of 1 × 106 cells (MDA-MB-231-GFP, MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b, MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3 or MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3-PKCα) into the fourth mammary fat pad in 0.1ml of 1:1 growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences). Animals injected with MDA-MB-231-GFP or MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b cells (eight mice in each group) were euthanized 8–10 weeks after injection (mice with tumors exceeding 1.0cm limit were killed at week 8). Animals injected with MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3 or MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3-PKCα cells (five mice in each group) were killed 12 weeks after injection. For determining cell proliferation in mammary tumor tissues, mice were injected [intraperitoneal (i.p.)] with 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (70mg/kg) 2h before killing. Mammary tumors and lungs were harvested, fixed with 10% formalin solution, paraffin embedded for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence staining.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence staining of mouse mammary tumor and lung sections

Mouse mammary tumor and lung sections were prepared and subjected to H&E staining as described previously (37). The immunohistochemistry staining of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine in mammary tumor sections was carried out using the ABC kit from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA) as described previously (37). The presence of GFP in mouse lung sections was determined by performing GFP immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence staining, or by staining sections with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) followed by directly viewing GFP fluorescence under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U, Nikon, Melville, NY). The captured GFP fluorescent images were overlaid with the blue fluorescent images (nucleus DAPI staining) using MetaMorph software.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed using Tris–sodium dodecyl sulfate and sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electorphoresis was used as described previously (34). These primary antibodies were used: anti-ZEB1, anti-E-cadherin, anti-PKCα (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), anti-PKCβI (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-Rac1 (Millipore, Temecula, CA) and anti-β-Actin (Sigma).

Rac1-GTP pulldown assay

Rac1-GTP pulldown assays were carried out to analyze active Rac1 levels following previously described protocol (38). Rac1-GTP levels were quantified using ImageJ software and the quantifications are presented as the relative Rac1-GTP levels (ratio of Rac1-GTP levels divided by the corresponding total Rac1 levels).

MTT assay and soft agar colony formation assay

The tetrazolium dye colorimetric test (MTT assay) was used to measure cell growth indirectly. Briefly, cells were cultured in 96-well plates (3–5×104 cells/well in 100 μl of complete culture medium) for 24, 48, or 72h, respectively. At the end of culture, 50 μl of the MTT reagent (5mg/ml) was added to each well and incubated for 4h. Then, 200 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to each well and incubated for another hour. The plate was read using a microplate reader (SpectraMAX Plus, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at a wavelength of 570nm. Soft agar colony formation assay was performed as described previously (34). Colony formation in the agar was photographed and counted (if >100 µm) under a phase-contrast microscope after 4 week incubation.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses for the significance of differences in numerical data (mean ± SD) were carried out by testing different treatment effects via analysis of variance (ANOVA) using a general linear model [Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC]. Differences between treatment groups were determined using a two sample t-test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The miR-200 family levels are extremely low in basal mesenchymal-like TNBC cells and metastatic TNBC tumors and are inversely correlated with TNBC cell migratory abilities

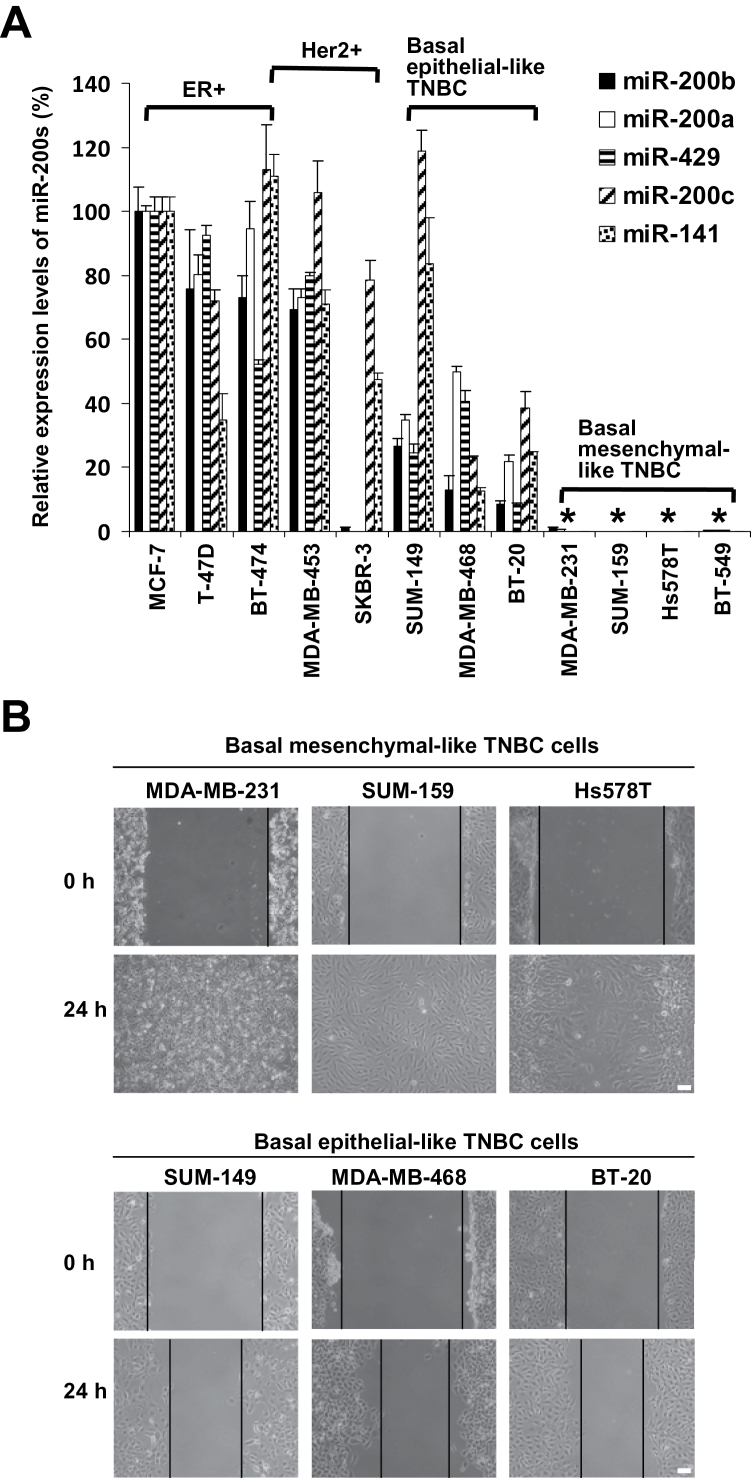

Although abnormal expression of miR-200 family has been observed in various types of cancers (26–28), their expression levels among different kinds of breast cancer cells and different subtypes of breast tumors are not well known. We first determined miR-200 family levels among 12 kinds of breast cancer cells. The basic features of these commonly used breast cancer cell lines were described previously (39). Compared with other breast cancer cells, the basal mesenchymal-like TNBC cells have extremely low levels of miR-200s (Figure 1A). The only exception is that the Her2+ SKBR3 cells have very low levels of the miR-200b/-200a/-429 group (Figure 1A). Moreover, we also compared miR-200 levels among different subtypes of breast cancers including ER+, Her2+, non-metastatic TNBC and metastatic TNBC tumors by analyzing a published breast cancer tissue miRNA microarray data set in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). We found that metastatic TNBC tumors have the lowest levels of miR-200 family (Supplementary Figure 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Fig. 1 .

The miR-200 family levels in breast cancer cells are inversely correlated with their migratory capabilities. (A) Q-PCR analysis of miR-200 expression levels in breast cancer cells. The levels of miR-200 family are expressed relative to that of MCF-7 cells and are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, compared with other types of breast cancer cells. (B) Comparison of TNBC cell migration by wound healing assay. Scale bar = 100 µm. Similar results were obtained in two repeated experiments.

Basal epithelial-like TNBC cells display a differentiated and epithelial-like morphology and express high levels of E-cadherin (data not shown). In contrast, basal mesenchymal-like TNBC cells exhibit a fibroblast-like morphology and their E-cadherin expression is undetectable by western blot (data not shown). We examined and compared the migratory capabilities of different kinds of TNBC cells using a wound healing assay. As shown in Figure 1B, while basal mesenchymal-like TNBC cells are able to fully close the wound within 24h, basal epithelial-like TNBC cells close the wound marginally, indicating that basal mesenchymal-like TNBC cells migrate significantly faster than basal epithelial-like TNBC cells. Collectively, these results show that miR-200 levels in TNBC cells are inversely correlated with their migratory abilities.

Stably re-expressing miR-200b in basal mesenchymal-like TNBC cells significantly reduces their migration and suppresses mammary tumor lung micrometastasis

To determine the effect of miR-200 on basal mesenchymal-like TNBC cell migratory behavior in vitro and metastatic capability in vivo, we chose to ectopically express a single member (miR-200b) of miR-200 family in two TNBC cells (MDA-MB-231 and SUM-159). This is due to the fact that limited studies have been done on the effect of a single member of miR-200 family, particularly miR-200b, on cancer metastasis. In contrast to GFP control cells that still exhibit mesenchymal-like morphology, miR-200b stably expressing cells display epithelial-like morphology as viewed under a bright light (Supplementary Figure 2A, available at Carcinogenesis Online) or fluorescent microscope (Supplementary Figure 2B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Multiple miR-200b stably expressing clones were established, all having similar epithelial-like morphology and expressing high levels of E-cadherin, but low levels of ZEB1 (Supplementary Figure 2C, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Q-PCR analysis showed that miR-200b levels in miR-200b stable expression cell clones are about 3-fold higher than MCF-7 cells, and about 1.7-fold higher than immortalized non-transformed human mammary epithelial cells (Supplementary Figure 2D, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Four miR-200b stably expressing clones for each cell line were pooled together and used as miR-200b stably expressing cells for all subsequent experiments.

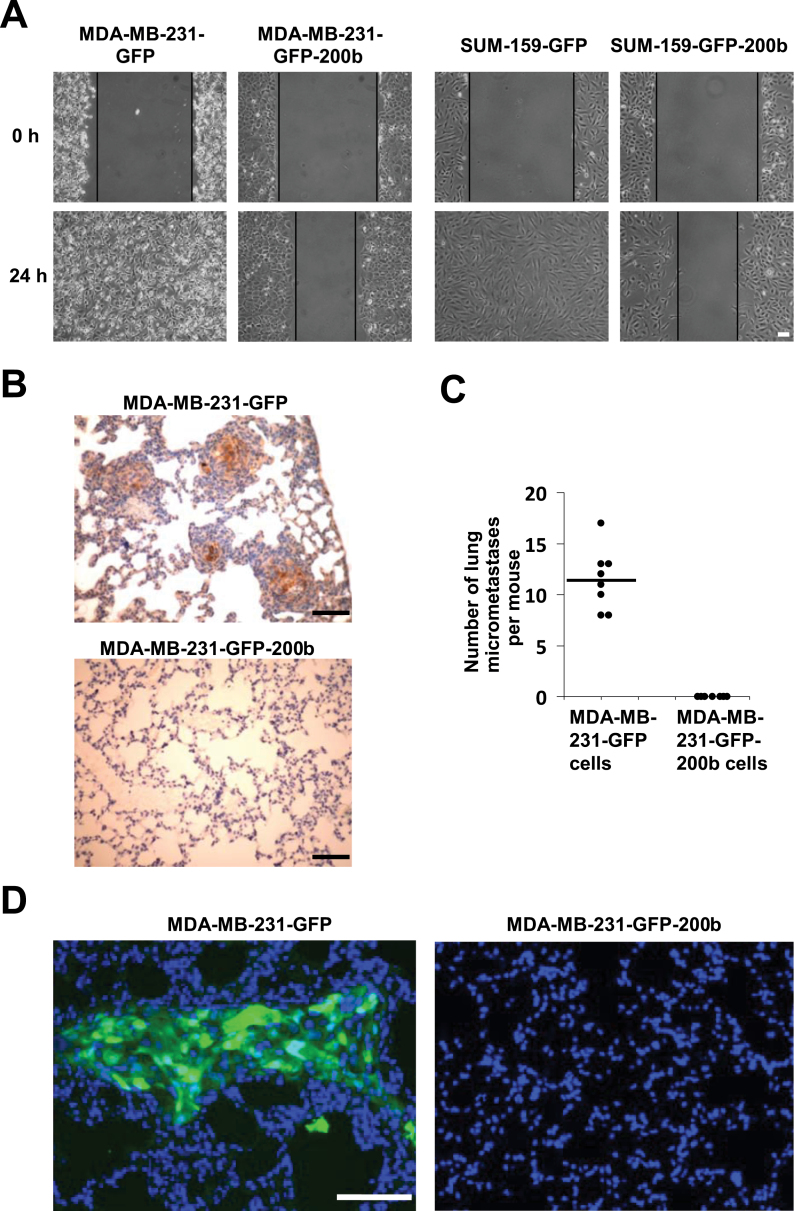

Re-expressing miR-200b significantly reduces MDA-MB-231 and SUM-159 cell proliferation (Supplementary Figure 3A, available at Carcinogenesis Online) as well as soft agar colony formation (Supplementary Figure 3B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Wound healing assays revealed that while GFP control cells are able to fully close the wound within 24h, the miR-200b expressing cells only close the wound about 30% (Figure 2A). These results show that re-expressing miR-200b is able to drastically reduce TNBC cell migration, suggesting that loss of miR-200b expression plays an important role in the enhanced migratory behavior of basal mesenchymal-like TNBC cells. The inhibitory effect of stably expressing miR-200b on breast cancer cell migration is further confirmed by using another cell migration assay—Transwell cell migration assay (Supplementary Figure 4A and B, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Fig. 2.

Stably expressing miR-200b in basal mesenchymal-like TNBC cells drastically reduces cell migration and inhibits mammary tumor metastasis. (A) Wound healing cell migration assay for GFP control and miR-200b stably expressing cells. (B) Representative images of GFP immunohistochemistry staining of lung sections from mice with mammary fat pad injection of MDA-MB-231-GFP or MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b cells as described in Materials and methods. Brownish color inside the foci indicates GFP-positive staining. (C) Quantifications of GFP-positive immunohistochemistry staining foci in lung sections from mice with mammary fat pad injection of MDA-MB-231-GFP or MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b cells. (D) Representative overlaid images of GFP fluorescence (green color) and nuclear DAPI (blue color) staining in lung sections from mice with mammary fat pad injection of MDA-MB-231-GFP or MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b cells. Lung sections were first stained with DAPI, then viewed and photographed under a fluorescence microscope. Scale bar = 100 µm.

To determine the effect of miR-200b on TNBC metastatic behavior in vivo, we performed a mouse orthotopic mammary xenograft tumor model study by injecting MDA-MB-231-GFP or MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b cells into the mammary fat pad. All eight mice injected with MDA-MB-231-GFP cells, and seven out of eight mice injected with MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b cells produced mammary tumors, which displayed a similar histology of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma as revealed by H&E staining (Supplementary Figure 5A, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Mammary tumors produced by MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b cells are significantly smaller than those of MDA-MB-231-GFP cells (Supplementary Figure 5B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Significantly less 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine positive staining is observed in mammary tumor tissues produced by miR-200b expressing cells (Supplementary Figure 5C–D, available at Carcinogenesis Online), indicating that re-expressing miR-200b reduces tumor cell growth in vivo. Immunohistochemistry staining of GFP in lung sections showed that all mice injected with MDA-MB-231-GFP cells have GFP-positive staining foci, indicating the occurrence of lung micrometastasis (Figure 2B and C). In striking contrast, no lung sections from mice injected with MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b cells have any detectable GFP-positive staining (Figure 2B and C). Moreover, the presence of GFP in lung sections was further demonstrated by directly viewing GFP fluorescence under a fluorescence microscope (Figure 2D). Together, these results indicate that stably expressing miR-200b is able to suppress mouse mammary xenograft tumor lung micrometastasis.

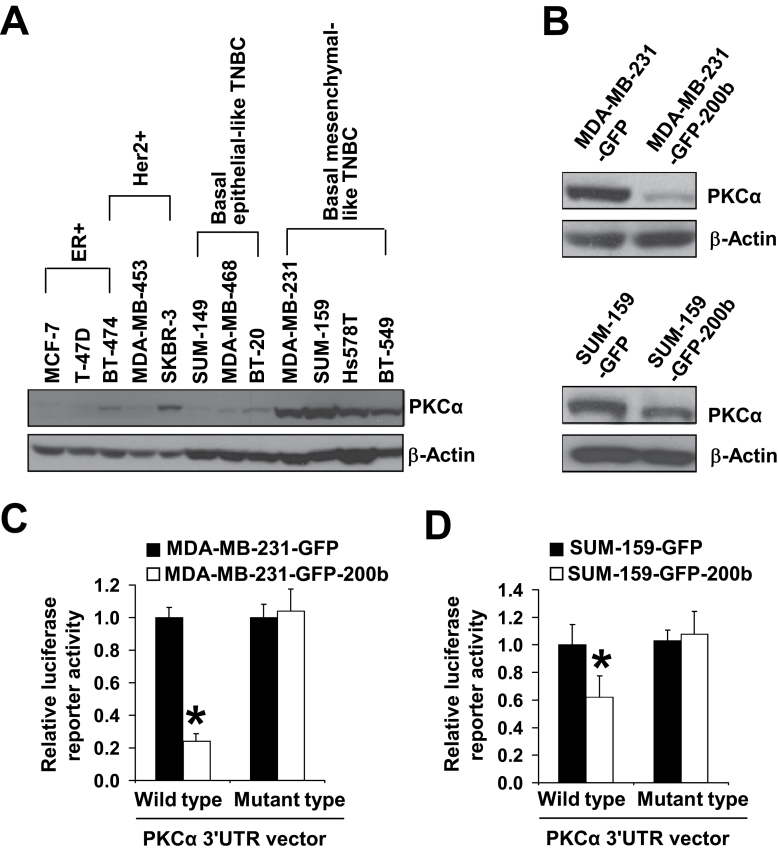

PKCα is a direct target of miR-200b

We next wanted to investigate the underlying mechanism of miR-200b suppressing TNBC cell migration and tumor metastasis. Previous studies showed that EMT-inducing transcription factors ZEB1 and ZEB2 are direct targets of miR-200 family (15–19), implying that downregulation of ZEB1/2 by miR-200 may play an important role in its inhibitory effect on metastasis. However, a recent study reported that ZEB1 knockdown marginally reduces TNBC cell migration and that miR-200 could repress tumor metastasis through ZEB1-independent mechanisms (40). To identify miR-200b new targets that may play crucial roles in its inhibitory effect on TNBC cell migration and tumor metastasis, we performed a bioinformatic analysis. Among the predicted targets of miR-200b, we are particularly interested in PKCα based on recent studies showing its critical role in regulating breast cancer cell stemness, mouse mammary tumor metastasis and the association of its expression with high grade of TNBC (31–33). We first compared the expression levels of PKCα among 12 kinds of breast cancer cells. Western blot analysis showed that PKCα protein levels are remarkably higher in basal mesenchymal-like highly migratory TNBC cells than the weakly migratory ER+, Her2+ and basal epithelial-like TNBC cells (Figure 3A), which is inversely correlated with miR-200b levels among these cells (Figure 1A). Moreover, re-expressing miR-200b in basal mesenchymal-like TNBC cells drastically reduces the protein level of PKCα (Figure 3B) but has no effect on the levels of other PKC isozymes (Supplementary Figure 6, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Fig. 3.

PKCα is a direct target of miR-200b. (A) Western blot analysis of PKCα protein levels in 12 kinds of breast cancer cells. (B) Western blot analysis of PKCα protein levels in GFP control and miR-200b stably expressing cells. (C, D) Quantifications of PKCα 3′UTR wild-type and mutant-type vector luciferase reporter activity in GFP control and miR-200b stably expressing cells. The luciferase reporter activity (mean ± SD, n = 3) is expressed relative to control cells. *P < 0.05, compared with control cell group. Similar results were obtained in two repeated experiments.

A putative conserved binding site for miR-200b at nucleotide position 1319–1325 of human PKCα 3′UTR is predicted by two miRNA target-predicting software (TargetScan and DIANA-MICROT). We then generated the wild-type and mutant-type of PKCα 3′UTR luciferase reporter vectors. Dual luciferase reporter assays showed that re-expressing miR-200b in MDA-MB-231 and SUM-159 cells significantly reduces PKCα wild-type 3′UTR luciferase reporter activity (Figure 3C) but has no effect on the mutant-type 3′UTR luciferase reporter activity (Figure 4D). Collectively, these findings indicate that PKCα is a direct target of miR-200b.

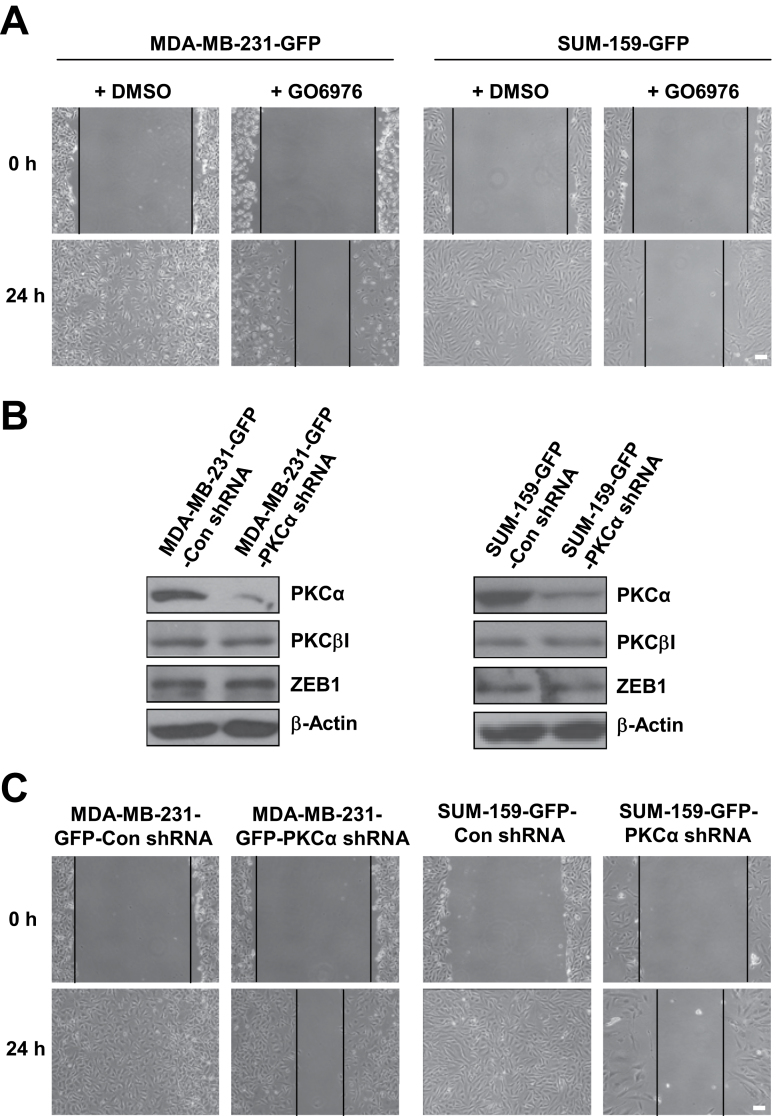

Fig. 4.

Inhibiting PKCα activity or knocking down PKCα expression reduces basal mesenchymal-like TNBC cell migration. (A) Effect of GO6976 (1 µM) treatment on basal mesenchymal-like TNBC cell migration determined by wound healing assay. (B) Western blot analysis of PKCα, PKCβI and ZEB1 protein level in control and PKCα shRNA knockdown cells. (C) Wound healing cell migration assay for control and PKCα shRNA knockdown cells. Scale bar = 100 µm. Similar results were obtained in two repeated experiments.

Inhibiting or knocking down PKCα reduces TNBC cell migration and forced expression of PKCα impairs the inhibitory effect of miR-200b on cell migration and tumor metastasis

We next wanted to determine whether downregulation of PKCα plays a role in the inhibitory effect of miR-200b on TNBC cell migration and tumor metastasis. We first used the inhibitor GO6976 that specifically inhibits PKCα and PKCβI activity. Wound healing assays showed that GO6976 treatment remarkably reduces MDA-MB-231 and SUM-159 cell migration (Figure 4A), suggesting that PKCα may play an important role in TNBC cell migration. To further demonstrate this point, we generated PKCα shRNA stable knockdown cells. Western blot analysis revealed that PKCα level is drastically reduced, but PKCβI and ZEB1 levels are unchanged in PKCα stable knockdown cells (Figure 4B). PKCα knockdown reduces cell proliferation by about 20% (Supplementary Figure 7A, available at Carcinogenesis Online). However, wound healing assays showed that PKCα knockdown drastically reduces cell migration (Figure 4C). Together, these results indicate that PKCα is essential for TNBC cell migration and downregulation of PKCα may play an important role in the inhibitory effect of miR-200b on TNBC cell migration.

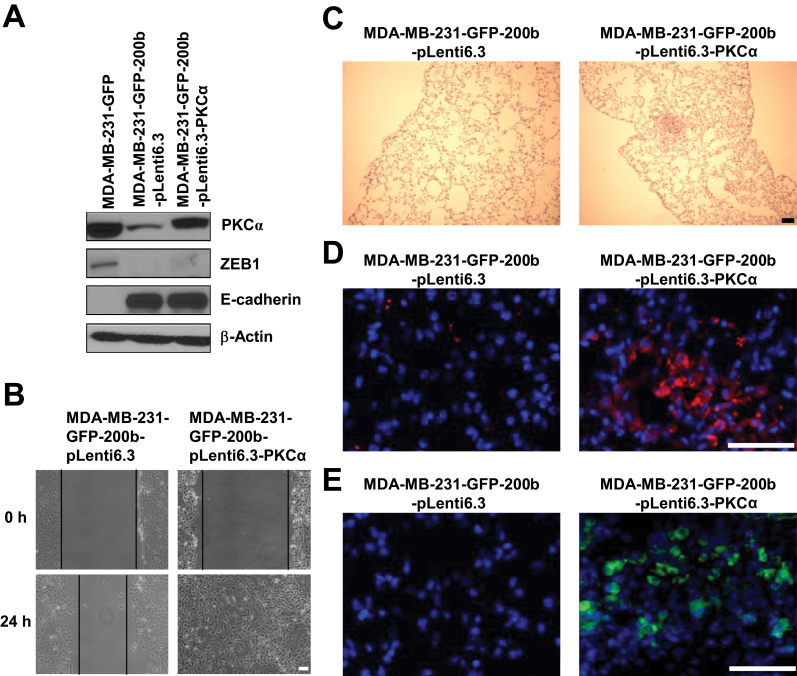

To further determine the role of PKCα in the inhibition of TNBC cell migration by miR-200b, we next overexpressed PKCα in miR-200b stable expression cells and generated PKCα-miR-200b double-stable expression cells. Forced expression of PKCα in MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b cells was confirmed by western blot (Figure 5A). Forced expression of PKCα does not significantly change the levels of ZEB1, E-cadherin and miR-200b (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure 7C, available at Carcinogenesis Online), and only increases cell proliferation by about 25% (Supplementary Figure 7B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). However, forced expression of PKCα in miR-200b expressing cells overcomes the inhibitory effect of miR-200b on cell migration as revealed by wound healing assays (Figure 5B). Collectively, these results further indicate that downregulation of PKCα plays a key role in the inhibitory effect of miR-200b on TNBC cell migration.

Fig. 5.

Forced expression of PKCα impairs the inhibitory effect of miR-200b on cell migration and tumor metastasis. (A) Western blot analysis of PKCα, ZEB1 and E-cadherin levels in MDA-MB-231-GFP, MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3 and MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3-PKCα cells. (B) Wound healing cell migration assay for MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3 and MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3-PKCα cells. Scale bar = 100 µm. (C) Representative images of H&E staining of lung sections from mice with mammary fat pad injection of MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3 or MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3-PKCα cells. Scale bar = 100 µm. (D) Representative overlaid images of immunofluorescence staining of GFP (red color) with nuclear DAPI staining (blue color) in lung sections from mice with mammary fat pad injection of MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3 or MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3-PKCα cells. Scale bar = 50 µm. (E) Representative overlaid images of GFP direct fluorescence (green color) with nuclear DAPI staining (blue color) in lung sections from mice with mammary fat pad injection of MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3 or MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-pLenti6.3-PKCα cells. Scale bar = 50 µm.

To investigate whether forced expression of PKCα is able to impair the inhibitory effect of miR-200b on tumor metastasis, vector control and PKCα-miR-200b double-stable expression cells were injected into mouse mammary fat pad. Similar histology of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma is observed in mammary tumors produced by vector control (MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-plenti6.3) and PKCα-miR-200b double-stable expression (MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b-plenti6.3-PKCα) cells (Supplementary Figure 8A, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Moreover, forced expression of PKCα has no significant effect on mammary tumor growth (Supplementary Figure 8B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). In line with results shown in Figure 2B–D, no micrometastasis is observed in lung sections from mice injected with cells stably expressing miR-200b alone (Figure 5C–E and Supplementary Figure 8C, available at Carcinogenesis Online). In striking contrast, micrometastatic foci revealed by H&E staining (Figure 5C), GFP immunofluorescence staining (Figure 5D) and directly viewing GFP under a fluorescence microscope (Figure 5E), are observed in lung sections from mice injected with PKCα-miR-200b double-stable expression cells. Quantifications of lung micrometastatic foci are shown in Supplementary Figure 8C (available at Carcinogenesis Online). Together, these results indicate that forced expression of PKCα is able to impair the inhibitory effect of miR-200b on mammary tumor metastasis.

Downregulation of PKCα by miR-200b reduces the Rho GTPase Rac1 activation

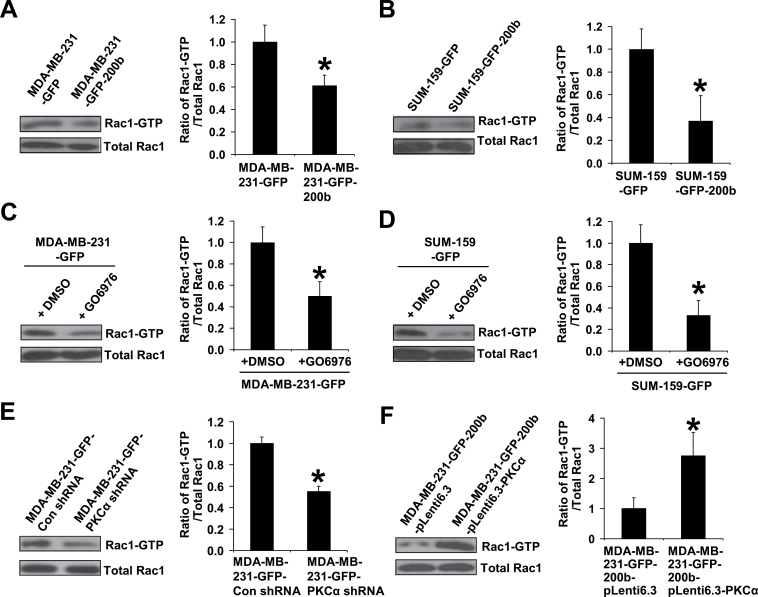

Finally, we wanted to further determine the mechanism through which PKCα downregulation by miR-200b suppresses TNBC cell migration and tumor metastasis. One mechanism of PKCα promoting cell migration is via activating the Rho GTPases Rac and Cdc42, master regulators of cell migration (41,42). Studies showed that Rac is overexpressed and highly activated in invasive breast cancer and inhibiting Rac activity blocks the spread of breast cancer (43,44). We then determined whether re-expressing miR-200b has an effect on Rac1 activation in TNBC cells. Consistent with the reduced migration observed in miR-200b expressing cells, the active Rac1 (Rac1-GTP) levels are significantly lower in MDA-MB-231-GFP-200b and SUM-159-GFP-200b cells than their control counterparts (Figure 6A and B), indicating that miR-200b is able to reduce Rac1 activation in TNBC cells.

Fig. 6.

Downregulation of PKCα by miR-200b reduces activation of the Rho GTPase Rac1. Rac1-GTP pulldown assay and quantifications for GFP control and miR-200b stably expressing cells (A and B), for GFP controls cells treated with dimethyl sulfoxide or GO6976 (1 µM) (C and D), for shRNA vector control and PKCα shRNA cells (E), and for miR-200b stably expressing alone and PKCα-miR-200b double stably expressing cells (F). Subconfluent cells were serum starved 24h, and then incubated in fresh medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum for 1h and collected for Rac1-GTP pulldown assay. Rac1-GTP and total Rac1 levels were quantified using ImageJ software and the quantifications are presented as the ratio of Rac1-GTP levels divided by the corresponding total Rac1 levels (mean ± SD, n = 3) relative to that of control cells. *P < 0.05, compared with control cell or dimethyl-sulfoxide-treated group.

We next wanted to determine whether miR-200b suppresses Rac1 activation via downregulating PKCα. We found that inhibiting PKCα activity or knocking down PKCα expression both significantly reduce Rac1-GTP levels in MDA-MB-231 and SUM-159 cells (Figure 6C–E). In sharp contrast, forced expression of PKCα in miR-200b stably expressing cells significantly increases Rac1-GTP levels (Figure 6F). Collectively, these results indicate that miR-200b suppresses Rac1 activation by targeting PKCα.

Discussion

Metastatic TNBC is a very aggressive subtype of breast cancer with poor prognosis and without efficient targeted therapies, underscoring the need for identifying novel targets to develop better treatment. In this study we found that miR-200 family levels are extremely low in highly migratory TNBC cells and metastatic TNBC tumors compared with other breast cancer subtypes. Moreover, we showed that ectopically expressing a single member (miR-200b) of the miR-200 family drastically reduces TNBC cell migration and suppresses mouse mammary tumor metastasis. We identified PKCα as a new direct target of miR-200b and found that PKCα levels are inversely correlated with the levels of miR-200b among 12 kinds of breast cancer cells. Inhibiting PKCα activity or knocking down PKCα expression in TNBC cells significantly reduces their migratory capabilities. In contrast, forced expression of PKCα in miR-200b stably expressing cells overcomes the inhibitory effect of miR-200b on TNBC cell migration and tumor metastasis, indicating a critical role of downregulation of PKCα in miR-200b inhibition of TNBC cell migration and tumor metastasis.

Despite the well-established role of miR-200 in inhibiting EMT, the reported effects of miR-200 on cancer metastasis are controversial. Our finding that ectopic expression of miR-200b inhibits TNBC cell migration and metastasis is consistent with a recent study showing that members of miR-200b/-c/-429 cluster repressed tumor metastasis (40), but contrasts with previous studies showing that miR-200 promoted metastasis (24,25). We think this inconsistency could be due to (i) differential targets and functions among individual members of, or between the two functional clusters of, the miR-200 family. Although there is only one nucleotide difference between the seed sequences of the two miR-200 functional clusters (miR-200b/-c/-429 and miR-200a/-141), these two clusters have been shown to have different targets and functions. For example, Uhlmann et al. reported that the miR-200b/-c/-429 cluster, but not the miR-200a/-141 cluster, efficiently reduced phospholipase C γ1 expression; and the miR-200b/-c/-429 cluster exhibited a much stronger inhibitory effect on breast cancer cell invasion than the other cluster (45). Similarly, Li et al. found that ectopically expressing members from the miR-200b/-c/-429 cluster, but not from the miR-200a/-141 cluster, reduced breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis (40). The promoting effect of miR-200 on tumor metastasis was observed in mouse mammary tumor 4T07 cells overexpressing miR-200c/-141 group or miR-200c/-141 plus miR-200b/-a/-429 group (24,25). No metastatic promoting effect was observed in 4T07 cells overexpressing the miR-200b/-a/-429 group alone (25). Instead, Gibbons et al. (23) reported that overexpression of miR-200b/-a/-429 group inhibited tumor metastasis. Of note, forced expression of miR-200b/-a/-429 group did not significantly increase the level of miR-141 (23,25). Together, these findings clearly show differential effects of individual miR-200 family members or two functional clusters on tumor metastasis despite their high seed sequence homology. And (ii) cancer subtype-specific effect of the miR-200 family. In this study, we found that ER+, PR+ and Her2+ human breast cancer cells and tumors had significantly higher levels of miR-200 than aggressive TNBC cells and tumors, which is consistent with the findings from Korpal et al. showing that high miR-200 family level was associated with ER-positive status and correlated with poor distant relapse-free survival only in the ER-positive tumors but not in the ER-negative tumors (25).

Cancer metastasis is a multistep process. When cancer cells obtain migratory and invasive capabilities, they migrate away from the primary tumor site and initiate the metastatic process (46). Inhibition of cancer cell migration can therefore be crucial in reducing cancer metastasis. Cell migration is a dynamic process involving actin cytoskeleton reorganization mediated by actin cytoskeleton-associated proteins and their regulators (42). In this study, we showed that PKCα is a new direct target of miR-200b and downregulation of PKCα plays a key role in the inhibitory effect of miR-200b on TNBC cell migration. Early studies showed that miR-200 may inhibit cancer cell migration by targeting certain actin cytoskeleton-associated proteins such as moesin and WAVE3 (Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein family member 3; 40,47,48). Our mechanistic study revealed that downregulation of PKCα by miR-200b inhibits TNBC cell migration probably through reducing the activation of Rac1, a key player in regulating actin cytoskeleton-associated proteins. Further studies are needed to determine the mechanism by which miR-200b reduces Rac1 activation. Our findings along with others indicate that miR-200 is capable of regulating actin cytoskeleton organization at multiple levels, which play critical roles in its inhibitory effect on cancer cell migration and metastasis.

The identification of PKCα as a new target of miR-200b is novel and important. In this study we found that (i) PKCα is a direct target of miR-200b; (ii) miR-200 expression is depleted in highly migratory TNBC cells and metastatic TNBC tumors; and (iii) the highest levels of PKCα are observed in highly migratory TNBC cells. These findings not only provide mechanistic insights for recent observations showing that high PKCα levels were most commonly detected in high-grade TNBC tumors (32,33), but also imply that our findings are potentially clinically relevant. PKCα was previously evaluated for breast cancer therapy, however only modest response to PKCα treatment was observed (49). We believe that the modest response to PKCα treatment may be largely due to lack of preselection of recruited patients for high expression of PKCα. Taken together, the findings from this study along with others strongly support the notion that PKCα could be a very promising target for treating metastatic TNBC, and PKCα should therefore be re-evaluated as a valid therapeutic target for metastatic TNBC. In addition, due to the high homology of kinase domains among PKC isozymes, targeting a specific PKC isozyme by small molecule inhibitors has been shown to be a huge challenge (50). Our finding that miR-200b specifically targets PKCα but not other PKC isozymes provides an alternative approach for targeting PKCα. Moreover, previous studies revealed that EMT-inducing transcription factors ZEB1 and ZEB2 are direct targets of miR-200 family (15–19), implicating an important role of downregulation of ZEB1/2 by miR-200 in its inhibitory effect on cancer metastasis. In this study, we found that PKCα is a direct target of miR-200b and stably expressing PKCα impairs the inhibitory effect of miR-200b on breast cancer metastasis with no significant effects on ZEB1 and E-cadherin levels. These findings provided additional evidence supporting the idea that miR-200 could repress cancer metastasis through ZEB1-independent mechanisms (40).

In summary, we found that miR-200 level is extremely low in highly migratory TNBC cells and metastatic TNBC tumors. Stably expressing a single member (miR-200b) of miR-200 family greatly reduces TNBC cell migration and suppresses tumor metastasis. We identified PKCα as a new direct target of miR-200b and found that miR-200b suppresses TNBC cell migration and tumor metastasis by downregulating PKCα, which in turn reduces Rac1 activation. Our findings suggest that miR-200b and PKCα may represent promising targets for developing novel therapies for metastatic TNBC.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Figures 1–8 can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

National Institutes of Health (R01ES017777 to C.Y.) and National Science Foundation (DMS-1209112 to Y.C.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Suyun Huang (The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX) for providing MDA-MB-231 cells; Dr Stephen Ethier (Wayne State University, Detroit, MI) for providing SUM-149 and SUM-159 cells; and Dr Sandra O’Reilly (Department of Physiology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI) for excellent help with mouse injections.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- EMT

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- ER

estrogen receptor

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- H&E staning

hematoxylin and eosin

- Her2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- miRNAs

MicroRNAs

- miR-200

microRNA-200

- PKCα

protein kinase Cα

- Q-PCR

quantitative PCR

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

- UTR

untranslated region

- ZEB1

zinc-finger E-box-binding homeobox factor 1

- ZEB2

zinc-finger E-box-binding homeobox factor 2.

References

- 1. Criscitiello C., et al. (2012). Understanding the biology of triple-negative breast cancer. Ann. Oncol., 23 (suppl. 6), vi13–vi18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Foulkes W.D., et al. (2010). Triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med., 363, 1938–1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bayraktar S., et al. (2013). Molecularly targeted therapies for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat., 138, 21–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dent R., et al. (2007). Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res., 13 (15 Pt 1), 4429–4434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carey L.A., et al. (2007). The triple negative paradox: primary tumor chemosensitivity of breast cancer subtypes. Clin. Cancer Res., 13, 2329–2334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. André F., et al. (2012). Optimal strategies for the treatment of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer with currently approved agents. Ann. Oncol., 23 (suppl. 6, vi46–vi51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bartel D.P. (2004). MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell, 116, 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sayed D., et al. (2011). MicroRNAs in development and disease. Physiol. Rev., 91, 827–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Di Leva G., et al. (2014). MicroRNAs in cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis., 9, 287–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang L., et al. (2012). MicroRNA-mediated breast cancer metastasis: from primary site to distant organs. Oncogene, 31, 2499–2511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Adams B.D., et al. (2008). Involvement of microRNAs in breast cancer. Semin. Reprod. Med., 26, 522–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yu Z., et al. (2010). microRNA, cell cycle, and human breast cancer. Am. J. Pathol., 176, 1058–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Altuvia Y., et al. (2005). Clustering and conservation patterns of human microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res., 33, 2697–2706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Michael M.Z., et al. (2003). Reduced accumulation of specific microRNAs in colorectal neoplasia. Mol. Cancer Res., 1, 882–891 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bracken C.P., et al. (2008). A double-negative feedback loop between ZEB1-SIP1 and the microRNA-200 family regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res., 68, 7846–7854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gregory P.A., et al. (2008). The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat. Cell Biol., 10, 593–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Korpal M., et al. (2008). The miR-200 family inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer cell migration by direct targeting of E-cadherin transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. J. Biol. Chem., 283, 14910–14914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park S.M., et al. (2008). The miR-200 family determines the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells by targeting the E-cadherin repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Genes Dev., 22, 894–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burk U., et al. (2008). A reciprocal repression between ZEB1 and members of the miR-200 family promotes EMT and invasion in cancer cells. EMBO Rep., 9, 582–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brabletz S., et al. (2010). The ZEB/miR-200 feedback loop–a motor of cellular plasticity in development and cancer? EMBO Rep., 11, 670–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. D’Amato N.C., et al. (2013). MicroRNA regulation of epithelial plasticity in cancer. Cancer Lett., 341, 46–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thiery J.P., et al. (2009). Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell, 139, 871–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gibbons D.L., et al. (2009). Contextual extracellular cues promote tumor cell EMT and metastasis by regulating miR-200 family expression. Genes Dev., 23, 2140–2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dykxhoorn D.M., et al. (2009). miR-200 enhances mouse breast cancer cell colonization to form distant metastases. PLoS One, 4, e7181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Korpal M., et al. (2011). Direct targeting of Sec23a by miR-200s influences cancer cell secretome and promotes metastatic colonization. Nat. Med., 17, 1101–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feng X., et al. (2014). MiR-200, a new star miRNA in human cancer. Cancer Lett., 344, 166–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hill L., et al. (2013). ZEB/miR-200 feedback loop: at the crossroads of signal transduction in cancer. Int. J. Cancer, 132, 745–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Howe E.N., et al. (2012). The miR-200 and miR-221/222 microRNA families: opposing effects on epithelial identity. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia, 17, 65–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Griner E.M., et al. (2007). Protein kinase C and other diacylglycerol effectors in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 7, 281–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Konopatskaya O., et al. (2010). Protein kinase Calpha: disease regulator and therapeutic target. Trends Pharmacol. Sci., 31, 8–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim J., et al. (2011). Sustained inhibition of PKCα reduces intravasation and lung seeding during mammary tumor metastasis in an in vivo mouse model. Oncogene, 30, 323–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tam W.L., et al. (2013). Protein kinase Cα is a central signaling node and therapeutic target for breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Cell, 24, 347–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tonetti D.A., et al. (2012). PKCα and ERβ are associated with triple-negative breast cancers in African American and Caucasian patients. Int. J. Breast Cancer, 2012, 740353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang Z., et al. (2011). Reversal and prevention of arsenic-induced human bronchial epithelial cell malignant transformation by microRNA-200b. Toxicol. Sci., 121, 110–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhao Y., et al. (2011). Inactivation of Rac1 reduces Trastuzumab resistance in PTEN deficient and insulin-like growth factor I receptor overexpressing human breast cancer SKBR3 cells. Cancer Lett., 313, 54–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang Z., et al. (2012). Akt activation is responsible for enhanced migratory and invasive behavior of arsenic-transformed human bronchial epithelial cells. Environ. Health Perspect., 120, 92–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhao Y., et al. (2010). Perfluorooctanoic acid effects on steroid hormone and growth factor levels mediate stimulation of peripubertal mammary gland development in C57BL/6 mice. Toxicol. Sci., 115, 214–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yang C., et al. (2005). Rac-GAP-dependent inhibition of breast cancer cell proliferation by {beta}2-chimerin. J. Biol. Chem., 280, 24363–24370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Neve R.M., et al. (2006). A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell, 10, 515–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li X., et al. (2013). MiR-200 can repress breast cancer metastasis through ZEB1-independent but moesin-dependent pathways. Oncogene (E-pub ahead of print 16. September 2013). 10.1038/onc.2013.370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sugimura R., et al. (2010). Noncanonical Wnt signaling in vertebrate development, stem cells, and diseases. Birth Defects Res. C. Embryo Today, 90, 243–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Burridge K., et al. (2004). Rho and Rac take center stage. Cell, 116, 167–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Katz E., et al. (2012). Targeting of Rac GTPases blocks the spread of intact human breast cancer. Oncotarget, 3, 608–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wertheimer E., et al. (2012). Rac signaling in breast cancer: a tale of GEFs and GAPs. Cell. Signal., 24, 353–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uhlmann S., et al. (2010). miR-200bc/429 cluster targets PLCgamma1 and differentially regulates proliferation and EGF-driven invasion than miR-200a/141 in breast cancer. Oncogene, 29, 4297–4306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hanahan D., et al. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell, 144, 646–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Howe E.N., et al. (2011). Targets of miR-200c mediate suppression of cell motility and anoikis resistance. Breast Cancer Res., 13, R45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sossey-Alaoui K., et al. (2009). The miR200 family of microRNAs regulates WAVE3-dependent cancer cell invasion. J. Biol. Chem., 284, 33019–33029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Roychowdhury D., et al. (2003). Antisense therapy directed to protein kinase C-alpha (Affinitak, LY900003/ISIS 3521): potential role in breast cancer. Semin. Oncol., 30(2 suppl. 3), 30–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mochly-Rosen D., et al. (2012). Protein kinase C, an elusive therapeutic target? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov., 11, 937–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.