Abstract

A high-throughput test to detect varicella-zoster virus (VZV) antibodies in varicella vaccine recipients is not currently available. One of the most sensitive tests for detecting VZV antibodies after vaccination is the fluorescent antibody to membrane antigen (FAMA) test. Unfortunately, this test is labor-intensive, somewhat subjective to read, and not commercially available. Therefore, we developed a highly quantitative and high-throughput luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) assay to detect antibody to VZV glycoprotein E (gE). Tests of children who received the varicella vaccine showed that the gE LIPS assay had 90% sensitivity and 70% specificity, a viral capsid antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) had 67% and 87% specificity, and a glycoprotein ELISA (not commercially available in the United States) had 94% sensitivity and 74% specificity compared with the FAMA test. The rates of antibody detection by the gE LIPS and glycoprotein ELISA were not statistically different. Therefore, the gE LIPS assay may be useful for detecting VZV antibodies in varicella vaccine recipients. (This study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under registration no. NCT00921999.)

INTRODUCTION

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes both chickenpox and zoster. A live attenuated varicella vaccine derived from the Oka strain of the virus was developed by Takahashi and colleagues in the 1970s and was licensed for routine use in the United States in 1995. One of the most sensitive tests for detecting VZV antibodies after vaccination is the fluorescent antibody to membrane antigen (FAMA) test. For this test, serial dilutions of human serum are incubated with live VZV-infected human fibroblasts, incubated with fluorescein-tagged anti-human immunoglobulin, and examined by fluorescence microscopy (1). The test detects antibodies to surface glycoproteins on live VZV-infected cells. While the FAMA test is highly predictive of protection from varicella infection after vaccination (2), the test is labor-intensive and somewhat subjective to read. Therefore, the FAMA assay is not applicable for large-scale or commercial testing, nor is it readily available.

Most laboratories use commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) to determine VZV seropositivity. A comparison of the commercially available ELISA with the FAMA test in recipients of the varicella vaccine indicates that the ELISA has a sensitivity of 74% and a specificity of 89% (3) (assuming that the FAMA has 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity). Thus, the ELISA is not considered sufficiently sensitive for reliably detecting antibodies after varicella immunization. Several studies have reported failures to seroconvert after immunization even after 2 doses, based on ELISA (4), and these are thought to represent a failure to detect antibody responses rather than a failure of the vaccine.

Modified FAMA tests have been developed, including ones that use fixed cells (5) and a flow cytometry-based FAMA assay using virus-infected cells (6). The fixed-cells test is subjective to read, and the flow cytometry-based test uses live virus-infected cells; however, neither test is commercially available. Other tests have been developed in an attempt to replace the FAMA test. A glycoprotein (gp) ELISA containing purified VZV-infected cell glycoproteins (including gE, gB, and gH) was developed by Merck to measure antibodies after vaccination (7); however, this test is not commercially available. In a recent study in Europe (8), a different commercially available gpELISA and a whole-cell ELISA had 92% and 96% sensitivity, respectively, compared to that of the FAMA test for detecting VZV antibodies in vaccine recipients. A time-resolved fluorescence immunoassay (TRFIA) showed 83% sensitivity and 88% specificity in vaccine recipients compared with those of the FAMA test (9). A comparison of a latex agglutination test, which is no longer marketed, with the FAMA test in recipients of the varicella vaccine indicated that the latex agglutination assay had a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 94% (3).

Serological testing after vaccination is not recommended, because commercially available tests are not sensitive enough to detect antibodies and may lack specificity (10, 11). Concerns persist about vaccine responses in women who may become pregnant and in health care workers, especially those who care for patients with varicella and zoster infection. All of these individuals have an increased risk for developing severe varicella infection. Therefore, a sensitive and specific reliable test for measuring VZV antibodies on a large-scale basis would be clinically useful. We developed a new assay based on a highly quantitative immunoprecipitation assay format (12) and compared it to the standard ELISA, FAMA test, and gpELISA for VZV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Serum samples were obtained from three sources, and all assays were performed in a blinded fashion. Archived serum from South Korea and New York were anonymized, and the use of samples was deemed exempt by the Office of Human Subjects Research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The subjects at NIH gave informed consent and the study (ClinicalTrials.gov under registration no. NCT00921999) was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The initial cohort of 40 samples from New York included 11 serum samples from healthy patients (mostly adults) obtained prior to developing varicella infection (all with negative FAMA titers), 11 serum samples from patients after proven varicella infection (all with positive FAMA titers), and 18 serum samples from healthy recipients of the varicella vaccine (78% with positive FAMA titers) Two additional independent cohorts were tested, one with 18 adult varicella vaccine recipients enrolled at NIH and one with 93 children who received the varicella vaccine in South Korea.

Serological assays.

The FAMA assay was performed using live cells, as described previously in New York (1) and Korea (13). The ELISA used for the serum samples from South Korea was performed using the VaccZyme VZV glycoprotein enzyme immunoassay (gpEIA) kit (The Binding Site, United Kingdom); an antibody titer of <50 mIU/ml was interpreted as seronegative (13). The ELISA used for the serum samples from the NIH was performed using the Trinity Biotech Captia VZV IgG kit, which uses inactivated VZV antigen. To compare the diagnostic performance of the tests, equivocal samples were called positive.

LIPS antigens and testing.

The extracellular domain of VZV glycoproteins gB, gC, gE, gH, gI, gK, gL, gM, and gN or the glycoproteins lacking the N-terminal signal sequence were cloned into pREN2 and pREN3S plasmids, respectively, to generate Renilla luciferase fusion proteins containing N- or C-terminal VZV proteins (12). The final gE construct contained amino acids 1 to 536 fused to Renilla luciferase and was constructed by PCR amplification of a VZV cosmid clone by PCR using two primer adapters: 5′-CCGCTCGAGATGGGGACAGTTAATA AACCTGTG-3′ and 5′-CCCAAGCTTCGTAGAAGTGGTGACGTTCCG-3′. The PCR products for the various glycoproteins, including for gE, were digested with XhoI and HindIII and inserted into XhoI-HindIII-digested pREN3S. Plasmid DNAs were prepared, and the integrity of the constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Antibodies to the various VZV glycoprotein constructs were measured by the luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) assay (12). Briefly, COS cells were transfected with VZV protein-Renilla luciferase fusion protein constructs, and lysates were prepared. From transfection, the activity of the COS cell lysates containing the different VZV fusions was determined by luminometry and expressed as luminometer units (LU) per ml. To measure VZV gE antibody levels, serum was diluted 1:10, and 10 μl was added to 1 × 106 LU of transfected COS cell extract. Immunoprecipitations were performed by adding protein A/G beads, and the LU were determined by luminometry. All LU data shown represent the averages of the data from at least two independent experiments.

Statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA) was used for statistical analyses. The antibody levels for the different samples are reported as the median with the interquartile range (IQR) values. A cutoff value was based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and was based on the gE test having 100% specificity with the initial test cohort. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used for a comparison of the antibody levels in the different groups. The area under the curve (AUC) was used as a global index of diagnostic accuracy.

RESULTS

Development of a gE VZV diagnostic LIPS assay and comparison with FAMA test.

An evaluation of the utility of the LIPS assay for serological diagnosis of VZV began by screening serum samples from 16 healthy blood donors for antibodies against nine different VZV surface glycoproteins. When LIPS assays to detect antibodies to VZV gE, gH, gI, gK, gL, gM, and gN were used to test the serum samples, only the VZV gE LIPS assay detected antibodies in all 16 serum samples (data not shown); therefore, all additional tests were performed using the gE LIPS assay.

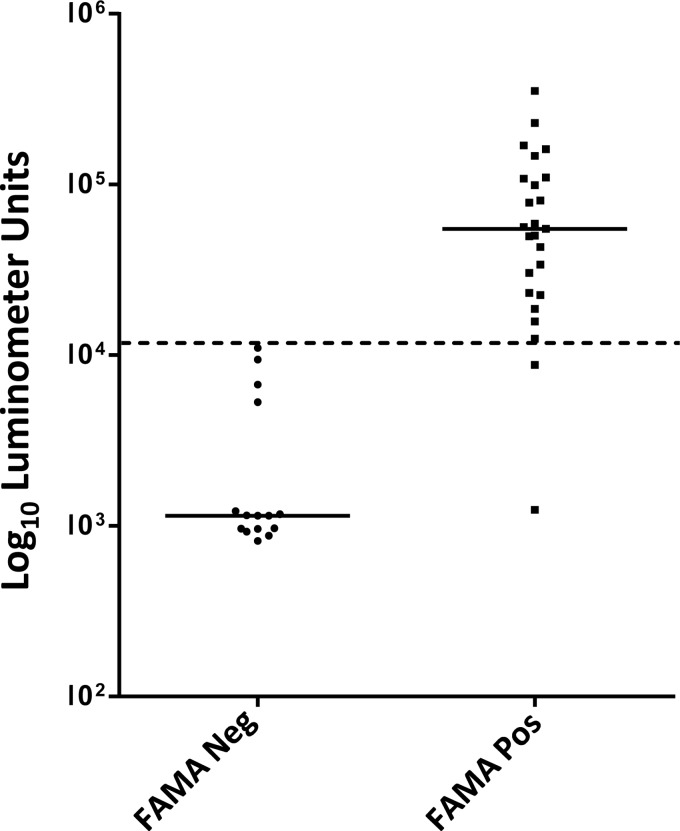

Using an independent set of 40 serum samples with known VZV serological status based on the FAMA test performed at Columbia University, the potential of the gE LIPS test for VZV diagnosis was evaluated in a blinded fashion. This cohort of samples included vaccine recipients and subjects before and after varicella infection. From the average of the data from these two independent tests, the anti-gE antibody levels in the subjects showed a wide dynamic range of detection spanning from 817 to 353,400 LU (Fig. 1). In the FAMA-negative samples, the median gE antibody level was 1,148 LU (interquartile range [IQR], 960 to 5,313), while the FAMA-positive samples had a 40-fold-higher median level of 55,100 LU (IQR, 22,840 to 109,100), and this difference in antibody levels between these two groups was highly statistically significant (Mann Whitney U test, P < 0.0001).

FIG 1.

Detection of anti-VZV gE antibody by luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) assay. The subjects in the validation cohort included persons prior to varicella vaccination, recipients of the varicella vaccine, and naturally infected persons. Each symbol represents an individual serum sample from a subject whose serum tested negative (Neg) or positive (Pos) in the FAMA assay. The antibody titers were measured in luminometer units. The dotted line represents the cutoff level for determining sensitivity and specificity, and the solid horizontal lines represent median values.

In order to compare the sensitivity and specificity of the LIPS assay with those of the FAMA test, a diagnostic cutoff value of 12,000 LU was assigned, which was derived from the ROC curve for an antibody test that was 100% specific for the healthy subjects. Using this cutoff value, the gE LIPS test compared to the FAMA test with all of the Columbia University samples (n = 40) showed 92% sensitivity and 100% specificity (Table 1). In the 11 healthy subjects with natural VZV infection, the gE LIPS test showed 91% sensitivity for all of these FAMA-positive samples. The gE LIPS test had 93% sensitivity and 100% specificity for the healthy vaccine recipients. Of the 11 unvaccinated healthy subjects, the gE LIPS test showed 100% specificity for all of these FAMA-negative samples. The promising results suggested that the gE LIPS test might be highly useful for detecting VZV antibodies following VZV vaccination.

TABLE 1.

Antibody results for varicella-zoster virus in different cohorts

| Cohort (n) | % (no. identified/total no.) ina: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIPS |

VCA ELISA |

gpELISA |

||||

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| New York (40) | 92 (23/25) | 100 (15/15) | ||||

| Vaccinated (18) | 93 (13/14) | 100 (4/4) | ||||

| Prior to varicella (11) | NAb | 100 (11/11) | ||||

| History of varicella (11) | 91 (10/11) | NA | ||||

| NIH vaccinees (18) | 90 (9/10) | 63 (5/8) | 90 (9/10) | 38 (3/8) | ||

| Korean vaccinees (93) | 90 (63/70) | 70 (16/23) | 67 (47/70) | 87 (20/23) | 94 (66/70) | 74 (17/23) |

VCA, viral capsid antigen; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; gpELISA, glycoprotein ELISA.

NA, not applicable.

Comparison of the VZV gE LIPS test with FAMA test, VCA ELISA, and gpELISA.

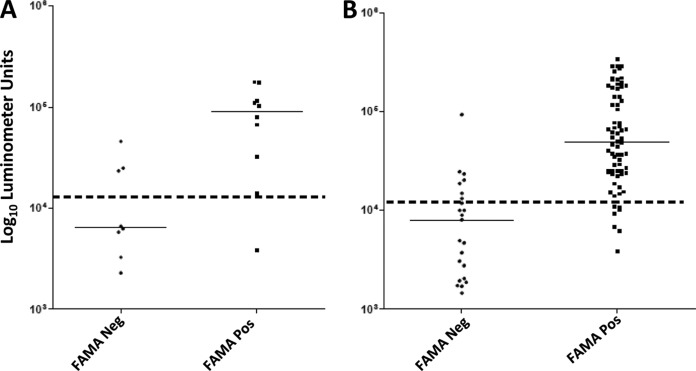

The diagnostic potential of the gE LIPS assay compared to that of the FAMA test and additional ELISA-based serological assays were evaluated in two additional cohorts. Eighteen adults who were enrolled at the NIH Clinical Center and had received the varicella vaccine several years earlier were tested using the FAMA assay, which showed that 10 subjects were seropositive and 8 were seronegative. LIPS testing of the NIH cohort employing the 12,000-LU cutoff demonstrated 90% sensitivity (9/10) and 63% specificity (5/8) (Fig. 2A). In comparison, the viral capsid antigen (VCA) ELISA in this cohort showed 90% sensitivity and 38% specificity. Of note, the same low-seropositive subject, with a FAMA test titer of 1:2, was missed by both the LIPS assay and VCA ELISA.

FIG 2.

Comparison of anti-VZV gE antibody by luciferase immunoprecipitation system (LIPS) assay with the fluorescent antibody to membrane antigen (FAMA) test. (A) Adults who received the varicella vaccine several years earlier. (B) Children who recently received the varicella vaccine. Each symbol represents an individual serum sample from a subject. The dotted line represents the cutoff level for determining sensitivity and specificity. Neg, negative; Pos, positive.

A second larger cohort of samples from South Korean children (n = 93) was also evaluated by the LIPS assay and compared with the FAMA test, VCA ELISA, and gpELISA. FAMA testing of the samples showed that 23 were seronegative and 70 were seropositive (Fig. 2B). The LIPS test indicated that the median gE antibody level in the seronegative Korean samples was 8,000 LU (interquartile range [IQR], 1,451 to 14,860) and was 49,070 LU (IQR, 24,130 to 147,850) in the seropositive samples, which were statistically different (P < 0.0001). Using the assigned cutoff value, the gE LIPS assay had 90% sensitivity (63/70) and 70% specificity (16/23). In comparison, the VCA ELISA showed 67% sensitivity (47/70) and 87% specificity (20/23). The gpELISA, which uses lectin-purified VZV glycoprotein in ELISA, showed 94% sensitivity (66/70) and 74% specificity (17/23). The LIPS assay and gpELISA had several of the same false negatives, and false-positive samples and ROC analysis of the LIPS assay and gpELISA showed no significant statistical difference in diagnostic performance, with AUC values of 0.91 (confidence interval [CI], 0.84 to 0.97; P > 0.0001) and 0.89 (CI, 0.81 to 0.97, P > 0.0001), respectively.

DISCUSSION

While the FAMA test is considered one of the most sensitive standard serological tests for detecting VZV antibodies, the test is labor-intensive and has a low throughput. This study demonstrated that the gE antigen in the LIPS format can robustly detect antibody titers for VZV diagnosis with good sensitivity and specificity. Unlike existing serological tests, such as FAMA, whole-cell ELISA, and gpELISA, which employ multiple natural VZV antigens, the LIPS test used a single recombinant gE antigen. gE is the most abundant VZV glycoprotein on the surface of virus-infected cells and is a major target of neutralizing antibodies.

Compared with the FAMA test in the three cohorts of varicella vaccine recipients, the gE LIPS assay had a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 71%. In contrast, compared with the FAMA test in two cohorts in which both tests were performed, the VCA ELISA had a sensitivity of 70% and a specificity of 74%. A comparison of the diagnostic performance of the gE LIPS test with that of the gpELISA showed that they behaved similarly. While the gE LIPS test had modest specificity compared to the FAMA assay in vaccine recipients (and it is possible that this was an artifact due to the greater sensitivity of the gE LIPS than the FAMA test), the two tests had a similar number of positive results (83 serum LIPS positive and 81 FAMA positive) in the two test cohorts of vaccine recipients (NIH and Korea).

We obtained reproducible results over time with different gE-Renilla luciferase fusion protein extracts. The possibility of using gE-Renilla luciferase extract frozen at −80°C may facilitate standardization, but further studies are needed before using the assay for clinical testing. Additional recombinant glycoprotein antigens or different gE constructs with better conformational epitopes due to potentially less interference by Renilla luciferase might further enhance performance. Nonetheless, the gE LIPS assay has a wide dynamic range of detection and can be performed rapidly. A demonstration of the effectiveness of a high-throughput LIPS assay for VZV antibodies in healthy vaccine recipients shows that this approach is feasible for the rapid screening of large numbers of serum samples. Additional experience with the LIPS assay in healthy populations who are known to have had clinical varicella or herpes zoster infection would provide additional information on the utility of this assay for assessing its ability to determine positive responses to the varicella vaccine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the intramural research programs of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 2 July 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Williams V, Gershon A, Brunell PA. 1974. Serologic response to varicella-zoster membrane antigens measured by direct immunofluorescence. J. Infect. Dis. 130:669–672. 10.1093/infdis/130.6.669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michalik DE, Steinberg SP, LaRussa PS, Edwards KM, Wright PF, Arvin AM, Gans HA, Gershon AA. 2008. Primary vaccine failure after 1 dose of varicella vaccine in healthy children. J. Infect. Dis. 197:944–949. 10.1086/529043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saiman L, LaRussa P, Steinberg SP, Zhou J, Baron K, Whittier S, Della-Latta P, Gershon AA. 2001. Persistence of immunity to varicella-zoster virus after vaccination of healthcare workers. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 22:279–283. 10.1086/501900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharrar RG, LaRussa P, Galea SA, Steinberg SP, Sweet AR, Keatley RM, Wells ME, Stephenson WP, Gershon AA. 2000. The postmarketing safety profile of varicella vaccine. Vaccine 19:916–923. 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00297-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaia JA, Oxman MN. 1977. Antibody to varicella-zoster virus-induced membrane antigen: immunofluorescence assay using monodisperse glutaraldehyde-fixed target cells. J. Infect. Dis. 136:519–530. 10.1093/infdis/136.4.519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lafer MM, Weckx LY, de Moraes-Pinto MI, Garretson A, Steinberg SP, Gershon AA, LaRussa PS. 2011. Comparative study of the standard fluorescent antibody to membrane antigen (FAMA) assay and a flow cytometry-adapted FAMA assay to assess immunity to varicella-zoster virus. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 18:1194–1197. 10.1128/CVI.05130-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wasmuth EH, Miller WJ. 1990. Sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for antibody to varicella-zoster virus using purified VZV glycoprotein antigen. J. Med. Virol. 32:189–193. 10.1002/jmv.1890320310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sauerbrei A, Schafler A, Hofmann J, Schacke M, Gruhn B, Wutzler P. 2012. Evaluation of three commercial varicella-zoster virus IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays in comparison to the fluorescent-antibody-to-membrane-antigen test. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 19:1261–1268. 10.1128/CVI.00183-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald SL, Maple PA, Andrews N, Brown KE, Ayres KL, Scott FT, Al Bassam M, Gershon AA, Steinberg SP, Breuer J. 2011. Evaluation of the time resolved fluorescence immunoassay (TRFIA) for the detection of varicella zoster virus (VZV) antibodies following vaccination of healthcare workers. J. Virol. Methods 172:60–65. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marin M, Guris D, Chaves SS, Schmid S, Seward JF. 2007. Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm. Rep. 56(RR04):1–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breuer J, Schmid DS, Gershon AA. 2008. Use and limitations of varicella-zoster virus-specific serological testing to evaluate breakthrough disease in vaccines and to screen for susceptibility to varicella. J. Infect. Dis. 197(Suppl 2):S147–S151. 10.1086/529448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burbelo PD, Hoshino Y, Leahy H, Krogmann T, Hornung RL, Iadarola MJ, Cohen JI. 2009. Serological diagnosis of human herpes simplex virus type 1 and 2 infections by luciferase immunoprecipitation system assay. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:366–371. 10.1128/CVI.00350-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YH, Hwang JY, Shim HM, Lee E, Park S, Park H. 2014. Evaluation of a commercial glycoprotein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for measuring vaccine immunity to varicella. Yonsei Med. J. 55:459–466. 10.3349/ymj.2014.55.2.459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]