Abstract

Monooxygenase (MO) enzymes initiate the aerobic oxidation of alkanes and alkenes in bacteria. A cluster of MO genes (smoXYB1C1Z) of thus-far-unknown function was found previously in the genomes of two Mycobacterium strains (NBB3 and NBB4) which grow on hydrocarbons. The predicted Smo enzymes have only moderate amino acid identity (30 to 60%) to their closest homologs, the soluble methane and butane MOs (sMMO and sBMO), and the smo gene cluster has a different organization from those of sMMO and sBMO. The smoXYB1C1Z genes of NBB4 were cloned into pMycoFos to make pSmo, which was transformed into Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2-155. Cells of mc2-155(pSmo) metabolized C2 to C4 alkanes, alkenes, and chlorinated hydrocarbons. The activities of mc2-155(pSmo) cells were 0.94, 0.57, 0.12, and 0.04 nmol/min/mg of protein with ethene, ethane, propane, and butane as substrates, respectively. The mc2-155(pSmo) cells made epoxides from ethene, propene, and 1-butene, confirming that Smo was an oxygenase. Epoxides were not produced from larger alkenes (1-octene and styrene). Vinyl chloride and 1,2-dichloroethane were biodegraded by cells expressing Smo, with production of inorganic chloride. This study shows that Smo is a functional oxygenase which is active against small hydrocarbons. M. smegmatis mc2-155(pSmo) provides a new model for studying sMMO-like monooxygenases.

INTRODUCTION

Monooxygenases (MOs) are involved in biodegradation, biosynthesis, and detoxification, and they catalyze key steps in both the carbon and nitrogen cycles (1–4). The MO enzymes are valuable for biotechnology because they can functionalize inert substrates, they have a broad substrate range, and they are sometimes highly enantioselective (5–7). The major types of MOs seen in bacteria can be categorized as soluble flavin (FMO) (8), soluble heme containing (p450) (9), soluble di-iron (SDIMO) (1), soluble pterin (10), soluble cofactor independent (11), membrane di-iron (AlkB) (12), and membrane copper (CuMMO) (13).

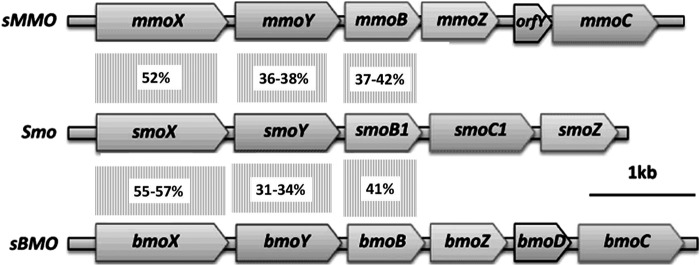

Mycobacterium sp. strains NBB3 and NBB4 were isolated on ethene (14), and they can also grow on gaseous alkanes (C2 to C4) but not on methane (15). A novel type of SDIMO gene cluster (smoXYB1C1Z) exists in the genomes of NBB3 and NBB4 (15), and the inferred Smo proteins have 30 to 60% amino acid identity to their closest homologs, which are the soluble methane MO (sMMO) (16, 17), and the soluble butane MO (sBMO) (18, 19) (Fig. 1; also see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Together, these three MO types make up a distinctive clade that has been designated the group 3 SDIMOs (14, 20). Although Smo is clearly a homolog of sMMO and sBMO, the smo genes have a peculiar arrangement relative to the other group 3 SDIMOs; the positions of the reductase (smoC1) and gamma subunit (smoZ) genes are reversed, and there is no orfY/bmoD homolog (21).

FIG 1.

Comparison of arrangement of the smo, mmo, and bmo genes. The predicted monooxygenase subunits of Smo are as follows: SmoX, α-hydroxylase; SmoY, β-hydroxylase; SmoB1, coupling/effector protein; SmoC1, γ-hydroxylase; and SmoZ, reductase. The level of predicted amino acid identity between three of the hydroxylase subunits is indicated in the boxes between the open reading frames.

The smo genes are located 7 kb from the hmoCAB genes, which encode a CuMMO involved in oxidation of C2 to C4 alkanes (15). The smo and hmo genes in NBB4 are found on the 615-kb plasmid pMYCCH.01 (GenBank accession number CP003054), in a catabolic gene region that also contains genes for alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases, coenzyme A (CoA) synthetases, and CoA transferases. In strain NBB3, a very similar catabolic gene region exists, but this is chromosomal (GenBank accession number CP003169). A close homolog of hmoCAB (bmoCAB) is found in Nocardioides strain CF8 (22), but it is not clear yet from the draft genome (GenBank accession number CM001852) whether smo genes are also present in CF8. The gene sequence comparisons and genomic context both suggest that Smo is involved in alkane oxidation, but to date, no experiments have been able to confirm this.

In previous work (23), we showed that smoX in NBB4 was transcribed under all growth conditions tested but that none of the Smo proteins could be detected by two-dimensional (2D) SDS-PAGE. Neither of these results match the predictions from sequence analysis, i.e., that the Smo mRNA and protein would be specifically detected in alkane-grown cells. A different approach is needed to clarify the function of Smo, such as gene knockout or heterologous expression. Knockout experiments with smo or other MO genes in NBB4 have been unsuccessful to date (unpublished data), leaving heterologous expression as the most useful approach to attempt to confirm the activity of Smo.

Neither sMMO or sBMO has been functionally expressed in Escherichia coli. sMMO can be expressed in methanotrophs that normally lack sMMO (24, 25), which has allowed site-directed mutagenesis (26), but the system has limitations; e.g., the particulate methane MO (pMMO) is also present, and the system is under complex regulatory control (27). sMMO can also be expressed, albeit with very low activity, in Pseudomonas (28) and Rhizobium (29). In the case of sBMO, genetic work has been enabled via homologous recombination in the natural host (Thauera butanivorans) (22), but this approach has some limitations similar to those of the homologous sMMO expression systems; e.g., it requires a gaseous inducer.

In this study, we tested expression of the smoXYB1C1Z genes in Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2-155 (30) under the control of the acetamidase regulatory system (31, 32). Our aims were to confirm that Smo was a functional oxygenase, to test its substrate range, and to gain insights into its physiological role and possible applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media, strains, and culture conditions.

E. coli EPI300 [Epicentre Biotechnologies; F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara, leu)7697 galU galK λ− rpsL (Strr) nupG trfA dhfr] was grown at 37°C in LB medium. M. smegmatis mc2-155 (30) was grown at 30°C, either in 1/10-strength Trypticase soy glucose medium (1/10-TSG) (14) for routine growth or in minimal salts medium (MSM) (33) containing 20 mM glucose and 2% (wt/vol) acetamide for MO expression (15). Tween 80 (0.05% [vol/vol]) was added to all broths of mc2-155 to minimize clumping. Kanamycin (Km) was added to EPI300 cultures at 50 μg/ml and to mc2-155 cultures at 20 μg/ml where required, to select pMycoFos and pSmo. Both E. coli and Mycobacterium broths were incubated aerobically with shaking at 200 rpm.

Construction of pSmo plasmid.

The smoXYB1C1Z gene cluster was amplified from genomic DNA of Mycobacterium NBB4 using Phusion polymerase (Finnzymes), with the primers JO1F (AAAGCTAGCGCCACCGTTTATGAAGTTG) and JO2R (AAAGCTAGCGGCCTACCGTTCCATTG). Thermocycling conditions for this and other PCRs are available on request. The primers JO1F and JO2R introduced NheI restriction sites at the ends of the PCR product. The PCR product was purified with the SureClean Plus kit (Bioline, United Kingdom), digested with NheI, and purified again. The vector pMycoFos was digested with NheI, dephosphorylated with Antarctic phosphatase, and purified with the same kit. The smo PCR product was ligated to pMycoFos using T4 DNA ligase at a 3:1 molar ratio of insert to vector DNA. The ligation mixture was transformed by heat shock into chemically competent EPI300 cells, and the mixture was plated on LB-Km agar (50 μg/ml of kanamycin).

E. coli clones carrying the correct construct were identified by PCR using primer pairs that spanned the left-hand and right-hand ligation junctions; these were JO7-JO8 (GGCTCTACCTGTTCGGCTTCACC and GTCGTCCTTCTCCCCTTCCATCC) and JO9-JO10 (GCCAATCTCTTTCTGCCCACCG and GCCAGCGCATCAACAATATTTTCACC). One clone yielding the expected-size products in both PCRs was retained for further analysis. Plasmid DNA extracted from this clone was subjected to restriction digestion with NdeI, and the insert DNA region was completely sequenced using Sanger dye terminator sequencing (Australian Genome Research Facility). This plasmid was named pSmo.

Expression of Smo in mc2-155.

Electrocompetent mc2-155 cells were prepared and transformed with plasmids pSmo and pMycoFos by methods described in an earlier work (15). Transformed cells were plated on 1/10-TSG-Km plates and incubated for 7 days, and then Kmr colonies from one plate were pooled, inoculated into 500 ml of 1/10-TSG-Km broth, and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0. Cells were washed twice in KP-Tween buffer (20 mM K2HPO4, 0.05% Tween 80 [pH 7.0]) by centrifugation and resuspension, divided into single-use 100-μl aliquots (OD600, approximately 30) in the same buffer, and stored at −80°C. Freezer stocks of mc2-155(pMycoFos) or mc2-155(pSmo) were inoculated into MSM-glucose-acetamide-Km broths (300 ml) at an initial OD600 of 0.05 and grown to an OD600 of 1.0 ± 0.2, corresponding to late exponential phase. Cells were washed twice in KP-Tween buffer and then used immediately for activity assays, as described below.

Alkane and alkene metabolism assays using GC.

Gaseous substrates (0.5 μmol = 200 μl of a 6.25% [vol/vol] gas mixture in air) were added to 16-ml crimp-sealed bottles containing 3.8 ml of KP-Tween containing 20 mM glucose. The bottles were laid flat (horizontally) in the shaker to facilitate gas transfer and were equilibrated with shaking (200 rpm) for 30 min at 30°C; then reactions were initiated by addition of washed cells (200 μl) to give OD600 values of 10 to 15. The bottles were shaken vigorously by hand for 10 s, a zero time headspace sample (250 μl) was taken immediately, and the bottles were returned to the shaker. Further headspace samples were taken at intervals for gas chromatography (GC) analysis by an HP series Plus 5890 II gas chromatograph with an HP-PLOT/Q column (15-m length, 0.53-mm diameter, 40-μm film) using helium as the carrier gas and flame ionization detection. The injector temperature was set at 200°C, the detector temperature was 250°C, and the oven temperature was 200°C. The machine was run in splitless mode. Apparent specific activities were calculated for ethane, propane, butane, and ethene from the initial linear portion of the substrate depletion curves. The substrate depletion rate was calculated by correcting for physical losses incurred by headspace sampling (2.08% volume at each sample point), and then the substrate depletion rate was converted to an apparent specific activity (nmol/min/mg of protein). Protein content was calculated from the OD600, using a previously determined standard curve for M. smegmatis (15).

Detection of epoxides using NBP reagent.

Washed cells (200 μl) were added to 2-ml vials, which were crimp sealed. Alkenes were added as 200 μl of neat gas or 1 μl of neat liquid, and then the cell suspensions were incubated with shaking for 6 h (vials laid horizontally, as described above). The 4-(4-nitrobenzyl) pyridine (NBP) reagent [500 μl of 100 mM 4-(4-nitrobenzyl) pyridine in ethylene glycol] was added directly to the cell suspensions, and the mixtures were heated for 1 h at 95°C and then centrifuged (5 min at 13,000 × g). The supernatants (500 μl) were removed and mixed with 1:1 triethylamine-acetone (500 μl), and the absorbances were measured immediately at 600 nm. Absorbance values were converted to epoxide concentrations using the Beer-Lambert law (A = εcl), with extinction coefficients determined as described below.

Calculation of extinction coefficients for NBP-epoxide conjugates.

An acetone stock solution of epoxyethane (0.64 M) was used to prepare standard solutions (0.5, 5, 10, and 20 mM) in KP buffer. Standard solutions of 1,2-epoxybutane were prepared similarly, except that neat epoxybutane was used as the source, and standards were made at 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 mM. A sample (200 μl) of each epoxide standard was added to separate 2-ml crimp-sealed vials. Subsequent processing of the samples with heat, NBP, and triethylamine was done as described above. The absorbances at 600 nm for each epoxide standard were plotted against the concentrations, and the extinction coefficients (M−1cm−1) were obtained from the gradient of this plot. In the case of epoxypropane, an extinction coefficient was estimated based on the value obtained experimentally in this study for 1,2-epoxybutane, multiplied by the ratio of the extinction coefficients for epoxypropane and 1,2-epoxybutane seen in a previous study (34) (the 1,2-epoxypropane coefficient from the prior study could not be used directly in this work due to different experimental methodologies).

Analysis of metabolism of organochlorines by gas chromatography and chloride assay.

Chlorinated substrates (6 to 8 μmol) were added to 16-ml crimp-sealed vials containing 3.68 ml or 3.8 ml of KP-Tween-glucose (for dichloroacetate [DCA] and vinyl chloride [VC], respectively). For each combination of substrate and cell type, duplicate vials were prepared. Substrates were added as 200 μl of neat gas (VC) or 320 μl of a 25 mM aqueous solution (DCA). The vials were allowed to equilibrate for 30 min at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm), and then washed cells (200 μl) were added to give final OD600 values of 10 to 15. Headspace sampling for GC was done immediately (as described above) to determine the initial amount of organochlorine present, and one vial from each pair was sacrificed immediately to determine the initial chloride concentration. The chloride assay was done by the colorimetric method of Bergman and Sanik, as described previously (35). The remaining vial from each experimental condition was incubated at 30°C with shaking for 6 h and then again sampled for organochlorines by headspace analysis and for chloride by colorimetric assay.

RESULTS

Heterologous expression of Smo in mc2-155.

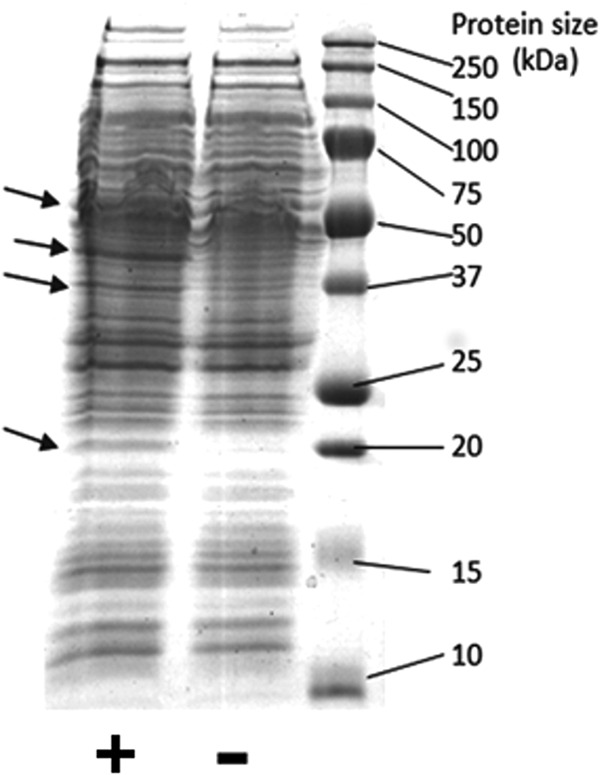

The smoXYB1C1Z gene cluster (5.4 kb) was amplified by PCR and cloned into the shuttle vector pMycoFos (36) to yield the plasmid pSmo. The correct structure of pSmo was confirmed by complete sequencing of the insert DNA (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). The plasmid pSmo contained a single copy of the smoXYB1C1Z genes, cloned in pMycoFos in the correct orientation with respect to the acetamide-inducible promoter, and there were no mutations detected relative to the expected sequence. SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2) showed that proteins corresponding to the sizes of the predicted Smo proteins were overexpressed in cell extracts of mc2-155(pSmo) compared to mc2-155(pMycoFos).

FIG 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of Smo proteins. Cell extract from mc2-155(pSmo) is indicated with a plus sign, while cell extract from the vector-only control is indicated with a minus sign. The arrows indicate four bands in mc2-155(pSmo) which are notably increased in expression compared to mc2-155(pMycoFos). The predicted sizes of the Smo proteins (in kDa) are as follows: SmoX, 58; SmoY, 44; SmoC1, 19; SmoB1, 38; and SmoZ, 20. Note that SmoZ and SmoC1 would be expected to appear as a single band due to their very similar sizes.

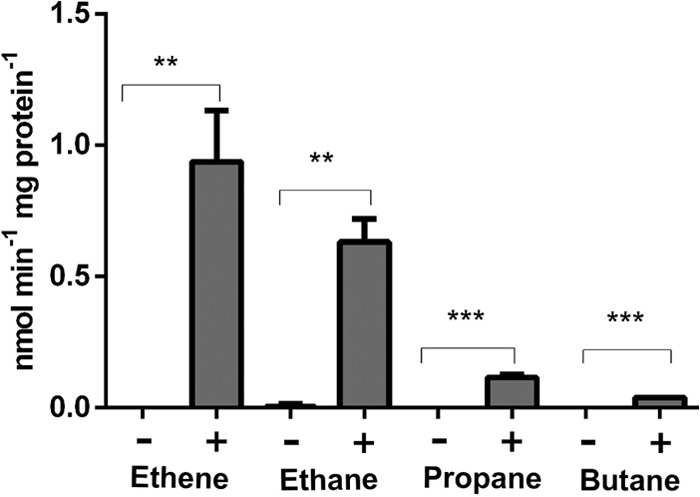

Smo acts on C2 to C4 hydrocarbons.

Resting cells of acetamide-induced mc2-155(pSmo) could metabolize a range of small hydrocarbons, but suspensions of mc2-155(pMycoFos) cells did not display this ability. The initial rates of substrate loss were used to calculate apparent specific activities. Comparison of these activities revealed a clear correlation with the substrate size, with the highest activities (0.5 to 0.9 nmol/min/mg protein) seen with ethane and ethene, lower activity with propane (0.1 nmol/min/mg protein), and very low activity with butane (0.04 nmol/min/mg of protein) (Fig. 3; see also Fig. S3 and S4 in the supplemental material). Methane was not metabolized at detectable levels (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Based on results from C2 compounds, it could be inferred that Smo has higher activity on alkenes than alkanes, but this difference was significant only at a P value of <0.1.

FIG 3.

Metabolism of hydrocarbons by cells of mc2-155 (pSmo) and mc2-155(pMycoFos). A plus sign indicates cells containing Smo, while a minus sign indicates cells containing vector only. Data are shown as the means of three independent experiments, with error bars indicating SEMs. **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.0005 (t test).

It is worth pointing out that the mc2-155 host cells did not significantly metabolize the test alkanes or alkenes under the standard assay conditions used in this work, despite the fact that mc2-155 possesses a group 5 SDIMO (MimABCD), which can oxidize propane and other substrates (37) and which enables weak growth on propane. Prolonged incubation did reveal some metabolism of butane in cell suspensions of mc2-155(pMycoFos), but this did not manifest until 8 to 12 h after butane addition (data not shown). In contrast, activity arising from pSmo was apparent immediately.

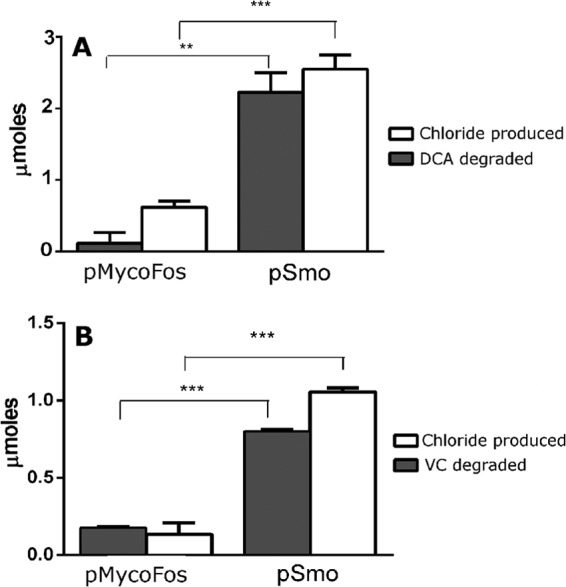

Smo can biodegrade organochlorines.

The potential of Smo for bioremediation was examined by testing activity against two common groundwater contaminants, 1,2-dichloroethane (DCA) and vinyl chloride (VC). Significantly greater biodegradation of both organochlorines and significantly greater production of inorganic chloride were seen in cell suspensions of mc2-155(pSmo) compared to mc2-155(pMycoFos) (Fig. 4). Biodegradation of DCA was 2-fold more extensive than biodegradation of VC. The reaction stoichiometries were 1.34 ± 0.27 and 1.38 ± 0.19 mol of chloride produced per mole of pollutant degraded for DCA and VC, respectively. While there is a fairly large error in these measurements, these data suggest removal of one chlorine per molecule for both VC and DCA, which is consistent with oxidation by MOs (38, 39).

FIG 4.

Biodegradation of organochlorines by cells of mc2-155(pSmo). (A) DCA as the substrate. (B) VC as the substrate. Data are shown as the means of three independent experiments, with error bars indicating SEMs. **, P < 0.005; ***, P < 0.0001 (t test).

Smo makes epoxides from small alkenes.

The biocatalytic potential of Smo was examined by testing epoxidation of a range of alkenes (Table 1). Cells of mc2-155(pSmo) made epoxides from ethene, propene, and 1-butene but not from 1-octene or styrene. Ethene was the preferred substrate, yielding approximately 10-fold more epoxide than propene and 40-fold more epoxide than butene. No epoxide was detected in cell suspensions of mc2-155(pMycoFos) (data not shown). The mc2-155(pSmo) cells did not react visibly with indole; this gives indigoid pigments in the case of many oxygenases (40–42).

TABLE 1.

Epoxidation of terminal alkenes by cells of mc2-155(pSmo)a

| Substrate | Predicted product | Epoxide produced (μmol) | % conversion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethene | Epoxyethane | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 70.6 ± 8.0 |

| 1-Propene | Epoxypropane | 0.58 ± 0.07 | 7.3 ± 0.8 |

| 1-Butene | 1,2-Epoxybutane | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| 1-Octene | 1,2-Epoxyoctane | 0 | 0 |

| Styrene | Styrene oxide | 0 | 0 |

Data are the means and SEMs from 3 independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

We have confirmed that the smoXYB1C1Z genes encode a functional oxygenase and that this enzyme is active on small alkanes, alkenes, and their chlorinated derivatives. Smo activity decreased as substrate size increased from C2 to C3 to C4. Chlorinated substrates were metabolized more slowly than nonchlorinated hydrocarbons; the activities on DCA and VC estimated from endpoint assays are 3-fold and 6-fold lower, respectively, than the activity on ethene. No activity was seen on methane, 1-octene, styrene, or indole. Taken together, the data indicate that Smo prefers small substrates, and C2 is optimal. Determination of the affinity constants (KS) is needed to more accurately define the preferred substrate of Smo.

The overall activity of mc2-155(pSmo) cells on hydrocarbons was low compared to the activity of wild-type NBB4 or mc2-155 cells expressing other MOs from the same promoter. Cells of NBB4 have 60-fold-higher activity on ethane than do cells of mc2-155(pSmo), and cells of mc2-155 expressing HmoCAB have 3-fold-higher activity on ethane than mc2-155(pSmo). These observations may reflect the true enzymology of Smo in NBB4, or they could be artifacts of the heterologous expression system. For example, a chaperonin, MmoG, is required for expression of sMMO genes in the normal host (43, 44); is a chaperonin also needed for optimal expression of Smo in NBB4 or mc2-155?

Ethene was the best substrate for Smo, and both NBB3 and NBB4 grow on ethene. However, we believe that Smo does not play a significant role in growth on ethene in these bacteria, for the following reasons. First, both NBB3 and NBB4 contain the etnABCD genes (encoding a group 4 SDIMO), which have been previously strongly linked to growth on ethene based on reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) and proteomics experiments with NBB4 (23) and other bacteria (45). Second, M. smegmatis mc2-155 cells expressing EtnABCD have much higher activity on ethene (24 nmol/min/mg of protein; V. McCarl, personal communication) than mc2-155(pSmo) (0.9 nmol/min/mg; this study). Finally, the genomes of other ethene oxidizers (JS60, JS614, JS617, and JS623) do not contain smo genes.

The overlapping substrate ranges of Smo and Hmo and their colocation in the genome suggest that Smo is an alternative gaseous alkane MO. By analogy with methanotrophs, NBB3 and NBB4 may switch the Smo and Hmo enzymes based on copper availability (21). There are problems with this hypothesis, however; smoX was transcribed in copper-containing medium (23), growth of NBB4 on C2 to C4 alkanes was almost entirely inhibited in copper-free medium or in the presence of allylthourea (ATU), a copper chelator (15), and the Smo gene cluster lacks an mmoD homolog, which is involved in copper regulation (21). Alternatively, Smo/Hmo may be a high-affinity/low-affinity pair. There is precedent for this also in methanotrophs (46), but this still does not explain why copper-free medium or allylthourea would so strongly inhibit growth of NBB4 on C2 to C4 alkanes: should not Smo enable growth under these conditions? The relationship between Smo and Hmo remains unclear at this stage.

sMMO can be expressed at high levels in heterologous methanotrophs (24, 25) and at very low levels in a few other hosts (28, 29), but to date, sMMO has not been functionally expressed in E. coli. This limitation has hindered research on this important enzyme. The work reported here provides a new example of functional expression of a group 3 SDIMO in a heterologous host. Strain mc2-155(pSmo) provides a new model system for studying SDIMO biochemistry and identifying factors limiting heterologous expression of the group 3 SDIMOs in E. coli.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The University of Sydney supported the consumables costs of this work.

We thank Andrew Holmes, Elissa Liew, and Samantha Cheung for helpful discussions and input into supervision of K.E.M. and J.O.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 July 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01338-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leahy JG, Batchelor PJ, Morcomb SM. 2003. Evolution of the soluble diiron monooxygenases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:449–479. 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00023-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nebert DW, Wikvall K, Miller WL. 2013. Human cytochromes P450 in health and disease. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 368(1612):20120431. 10.1098/rstb.2012.0431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ensign SA. 2001. Microbial metabolism of aliphatic alkenes. Biochemistry 40:5845–5853. 10.1021/bi015523d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.You J, Das A, Dolan EM, Hu Z. 2009. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea involved in nitrogen removal. Water Res. 43:1801–1809. 10.1016/j.watres.2009.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallagher SC, Cammack R, Dalton H. 1997. Alkene monooxygenase from Nocardia corallina B-276 is a member of the class of dinuclear iron proteins capable of stereospecific epoxygenation reactions. Eur. J. Biochem. 247:635–641. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00635.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmid A, Dordick JS, Hauer B, Kiener A, Wubbolts M, Witholt B. 2001. Industrial biocatalysis today and tomorrow. Nature 409:258–268. 10.1038/35051736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ensign SA, Hyman MR, Arp DJ. 1992. Cometabolic degradation of chlorinated alkenes by alkene monooxygenase in a propylene-grown Xanthobacter strain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3038–3046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray KA, Pogrebinsky OS, Mrachko GT, Xi L, Monticello DJ, Squires CH. 1996. Molecular mechanisms of biocatalytic desulfurization of fossil fuels. Nat. Biotechnol. 14:1705–1709. 10.1038/nbt1296-1705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grogan G. 2011. Cytochromes p450: exploiting diversity and enabling application as biocatalysts. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 15:241–248. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzpatrick PF. 1999. Tetrahydropterin-dependent amino acid hydroxylases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68:355–381. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen B, Hutchinson CR. 1993. Tetracenomycin F1-monooxygenase—oxidation of a naphthacenone to a naphthacenequinone in the biosynthesis of tetracenomycin-c in Streptomyces glaucescens. Biochemistry 32:6656–6663. 10.1021/bi00077a019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smits THM, Balada SB, Witholt B, van Beilen JB. 2002. Functional analysis of alkane hydroxylases from gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 184:1733–1742. 10.1128/JB.184.6.1733-1742.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zahn JA, DiSpirito AA. 1996. Membrane-associated methane monooxygenase from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath). J. Bacteriol. 178:1018–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman NV, Bui NB, Holmes AJ. 2006. Soluble di-iron monooxygenase gene diversity in soils, sediments and ethene enrichments. Environ. Microbiol. 8:1228–1239. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman NV, Le NB, Ly MA, Ogawa HE, McCarl V, Wilson NL, Holmes AJ. 2012. Hydrocarbon monooxygenase in Mycobacterium: recombinant expression of a member of the ammonia monooxygenase superfamily. ISME J. 6:171–182. 10.1038/ismej.2011.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hakemian AS, Rosenzweig AC. 2007. The biochemistry of methane oxidation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76:223–241. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.061505.175355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson RS, Hanson TE. 1996. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 60:439–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sluis MK, Sayavedra-Soto LA, Arp DJ. 2002. Molecular analysis of the soluble butane monooxygenase from ‘Pseudomonas butanovora.' Microbiology 148:3617–3629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brzostowicz PC, Walters DM, Jackson RE, Halsey KH, Ni H, Rouviere PE. 2005. Proposed involvement of a soluble methane monooxygenase homologue in the cyclohexane-dependent growth of a new Brachymonas species. Environ. Microbiol. 7:179–190. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00681.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes AJ, Coleman NV. 2008. Evolutionary ecology and multidisciplinary approaches to prospecting for monooxygenases as biocatalysts. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 94:75–84. 10.1007/s10482-008-9227-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semrau JD, Jagadevan S, DiSpirito AA, Khalifa A, Scanlan J, Bergman BH, Freemeier BC, Baral BS, Bandow NL, Vorobev A, Haft DH, Vuilleumier S, Murrell JC. 2013. Methanobactin and MmoD work in concert to act as the ‘copper-switch' in methanotrophs. Environ. Microbiol. 15:3077–3086. 10.1111/1462-2920.12150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sayavedra-Soto LA, Hamamura N, Liu CW, Kimbrel JA, Chang JH, Arp DJ. 2011. The membrane-associated monooxygenase in the butane-oxidizing Gram-positive bacterium Nocardioides sp. strain CF8 is a novel member of the AMO/PMO family. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 3:390–396. 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coleman NV, Yau S, Wilson NL, Nolan LM, Migocki MD, Ly M-A, Crossett B, Holmes AJ. 2011. Untangling the multiple monooxygenases of Mycobacterium chubuense strain NBB4, a versatile hydrocarbon degrader. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 3:297–307. 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lloyd JS, De Marco P, Dalton H, Murrell JC. 1999. Heterologous expression of soluble methane monooxygenase genes in methanotrophs containing only particulate methane monooxygenase. Arch. Microbiol. 171:364–370. 10.1007/s002030050723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith TJ, Slade SE, Burton NP, Murrell JC, Dalton H. 2002. Improved system for protein engineering of the hydroxylase component of soluble methane monooxygenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5265–5273. 10.1128/AEM.68.11.5265-5273.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borodina E, Nichol T, Dumont MG, Smith TJ, Murrell JC. 2007. Mutagenesis of the “leucine gate” to explore the basis of catalytic versatility in soluble methane monooxygenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:6460–6467. 10.1128/AEM.00823-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Theisen AR, Ali MH, Radajewski S, Dumont MG, Dunfield PF, McDonald IR, Dedysh SN, Miguez CB, Murrell JC. 2005. Regulation of methane oxidation in the facultative methanotroph Methylocella silvestris BL2. Mol. Microbiol. 58:682–692. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04861.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jahng D, Wood TK. 1994. Trichloroethylene and chloroform degradation by a recombinant pseudomonad expressing soluble methane monooxygenase from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2473–2482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jahng D, Kim C, Hanson R, Wood T. 1996. Optimization of trichloroethylene degradation using soluble methane monooxygenase of Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b expressed in recombinant bacteria. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 51:349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snapper SB, Melton RE, Mustafa S, Kieser T, Jacobs WR. 1990. Isolation and characterization of efficient plasmid transformation mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 4:1911–1919. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Triccas JA, Parish T, Britton WJ, Gicquel B. 1998. An inducible expression system permitting the efficient purification of a recombinant antigen from Mycobacterium smegmatis FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 167:151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parish T, Turner J, Stoker N. 2001. amiA is a negative regulator of acetamidase expression in Mycobacterium smegmatis. BMC Microbiol. 1:19. 10.1186/1471-2180-1-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman NV, Mattes TE, Gossett JM, Spain JC. 2002. Biodegradation of cis-dichloroethene as the sole carbon source by a beta-proteobacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2726. 10.1128/AEM.68.6.2726-2730.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheung S, McCarl V, Holmes AJ, Coleman NV, Rutledge PJ. 2013. Substrate range and enantioselectivity of epoxidation reactions mediated by the ethene-oxidising Mycobacterium strain NBB4. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97:1131–1140. 10.1007/s00253-012-3975-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le NB, Coleman NV. 2011. Biodegradation of vinyl chloride, cis-dichloroethene and 1,2-dichloroethane in the alkene/alkane-oxidising Mycobacterium strain NBB4. Biodegradation 22:1095–1108. 10.1007/s10532-011-9466-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ly MA, Liew EF, Le NB, Coleman NV. 2011. Construction and evaluation of pMycoFos, a fosmid shuttle vector for Mycobacterium spp. with inducible gene expression and copy number control. J. Microbiol. Methods 86:320–326. 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furuya T, Hirose S, Osanai H, Semba H, Kino K. 2011. Identification of the monooxygenase gene clusters responsible for the regioselective oxidation of phenol to hydroquinone in mycobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:1214–1220. 10.1128/AEM.02316-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hage JC, Hartmans S. 1999. Monooxygenase-mediated 1,2-dichloroethane degradation by Pseudomonas sp. strain DCA1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2466–2470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hartmans S, De Bont JA. 1992. Aerobic vinyl chloride metabolism in Mycobacterium aurum L1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:1220–1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ensley BD, Ratzkin BJ, Osslund TD, Simon MJ, Wackett LP, Gibson DT. 1983. Expression of naphthalene oxidation genes in Escherichia coli results in the biosynthesis of indigo. Science 222:167–169. 10.1126/science.6353574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McClay K, Boss C, Keresztes I, Steffan RJ. 2005. Mutations of toluene-4-monooxygenase that alter regiospecificity of indole oxidation and lead to production of novel indigoid pigments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5476–5483. 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5476-5483.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosic NN. 2009. Versatile capacity of shuffled cytochrome P450s for dye production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 82:203–210. 10.1007/s00253-008-1812-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stafford GP, Scanlan J, McDonald IR, Murrell JC. 2003. rpoN, mmoR and mmoG, genes involved in regulating the expression of soluble methane monooxygenase in Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Microbiology 149:1771–1784. 10.1099/mic.0.26060-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Csáki R, Bodrossy L, Klem J, Murrell JC, Kovacs KL. 2003. Genes involved in the copper-dependent regulation of soluble methane monooxygenase of Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath): cloning, sequencing and mutational analysis. Microbiology 149:1785–1795. 10.1099/mic.0.26061-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coleman NV, Spain JC. 2003. Epoxyalkane:coenzyme M transferase in the ethene and vinyl chloride biodegradation pathways of Mycobacterium strain JS60. J. Bacteriol. 185:5536–5545. 10.1128/JB.185.18.5536-5545.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dam B, Dam S, Kube M, Reinhardt R, Liesack W. 2012. Complete genome sequence of Methylocystis sp. strain SC2, an aerobic methanotroph with high-affinity methane oxidation potential. J. Bacteriol. 194:6008–6009. 10.1128/JB.01446-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.