Abstract

We sequenced 175 Clostridium botulinum type E strains isolated from food, clinical, and environmental sources from northern Canada and analyzed their botulinum neurotoxin (bont) coding sequences (CDSs). In addition to bont/E1 and bont/E3 variant types, neurotoxin sequence analysis identified two novel BoNT type E variants termed E10 and E11. Strains producing type E10 were found along the eastern coastlines of Hudson Bay and the shores of Ungava Bay, while strains producing type E11 were only found in the Koksoak River region of Nunavik. Strains producing BoNT/E3 were widespread throughout northern Canada, with the exception of the coast of eastern Hudson Bay.

INTRODUCTION

Botulism, a rare and severe disease characterized by a descending flaccid paralysis, is caused by botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT), the most potent toxin known. BoNT is produced by phylogenetically distinct anaerobic spore-forming bacteria grouped under the taxonomic designation of Clostridium botulinum. Rare botulinogenic strains of related clostridia, such as C. baratii, C. butyricum, and C. argentinense, have also been observed (1, 2). Seven serologically distinct BoNTs (A to G) can be distinguished based on neutralization of toxicity with specific antisera. Recently, a strain of C. botulinum producing botulinum neurotoxin type B (BoNT/B) and another BoNT that is not neutralized by antitoxins to BoNTs A to G has been isolated from a case of infant botulism (3). It has been proposed that this novel neurotoxin is an eighth serotype, BoNT/H (3, 4). The botulinum neurotoxins are comprised of three structural domains (translocation [HN], receptor binding [HC], and catalytic [LC]). These toxins target different SNARE (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor-attachment protein-receptor) proteins in the neuromuscular junction to block neurotransmitter release (5, 6).

Heterogeneity within the BoNTs has led to a classification of BoNTs into subtypes. Within a toxin serotype, differences in amino acid sequences can range from 0.9% to 25% (2, 7). Hill and Smith (8) point out that the newer subtypes have been defined based on their DNA sequence and propose the use of the term “subtype/genetic variant” to avoid confusion with the historical use of “subtype,” utilized to designate immunological or enzymatic differences among neurotoxins. Two approaches have been used to define new BoNT variants. The first uses a cutoff value of 2.5% difference in amino acid composition (9–11), whereas the second relies on a phylogenetic approach in which variants correspond to clades formed by the clustering of bont sequences (1, 7, 12) Based on these methods, bont/A1 to bont/A5, bont/B1 to bont/B7, bont/E1 to bont/E9, and bont/F1 to bont/F7 gene variants have been described (1, 2, 8, 10, 12–17).

In Canada, C. botulinum type E is the predominant BoNT serotype associated with food-borne botulism, accounting for 86.2% of all laboratory-confirmed food-borne botulism outbreaks reported between 1985 and 2005 (18). Although variant types E1, E3, and E7 have been identified in three separate Canadian isolates (2), little is known about BoNT/E variants involved in the majority of Canadian outbreaks.

In this study, the bont/E variant coding sequences (CDSs) for 175 C. botulinum type E isolates derived from food, clinical, and environmental sources were obtained using shotgun next-generation sequencing and compared to previously determined bont/E variants. Here, we present phylogenetic and sequence identity analyses of bont/E variants and report on the identification of two new variants, types E10 and E11. We also describe the geographic distribution of strains carrying these bont/E variants and the involvement of these strains in food-borne botulism incidents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture conditions, DNA isolation, and genome sequencing.

A total of 175 C. botulinum group II strains were cultured at room temperature for 48 to 72 h in an atmosphere of 10% H2, 10% CO2, and 80% N2 using 1.5% McClung-Toabe agar (Difco, Tucker, GA), supplemented with 5% egg yolk extract, and 5% yeast extract (Difco). Single colonies were inoculated into 10 ml of TPGY (5% [wt/vol] tryptone [Difco], 0.5% [wt/vol] peptone [Difco], 0.4% [wt/vol] glucose [Difco], 2% [wt/vol] yeast extract [Difco], and 0.1% sodium thioglycolate [Sigma, St. Louis, MO]) medium for 24 h. Genomic DNA from C. botulinum strains listed in Table 1 was extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Mississauga, Canada), and 16S rRNA sequencing was performed to verify homology to C. botulinum group II species (data not shown). Paired-end libraries were prepared using the Nextera or TruSeq kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). Library insert lengths (range, 200 bp to 1,000 bp) were estimated using an Agilent bioanalyzer (Agilent, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Sequencing was performed using paired-end sequencing by synthesis (run parameters: 2 × 25 to 2 × 250 cycles) on a GAIIx or MiSeq instrument according to the manufacturer protocols (Illumina). Reads were trimmed (Phred score < 25; trim ≤ 5 nucleotides [nt]) and filtered to include reads ≥25 nt long with a q-score of ≥30 (CG-Pipeline r432, http://sourceforge.net/projects/cg-pipeline). Average read coverage for all isolates exceeded 50-fold based on an average 3.8-Mb genome.

TABLE 1.

Clostridium botulinum group II BoNT/E strains studieda

| Isolate | OB | BoNT | Year | Sample type | Origin | Region | Location | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 211 VH Dolman | 1 | E3 | 1949 | Clinical | Pickled herring | PAC | Vancouver, BC | NML (35, 36) |

| E1 Dolman | 2 | E1 | <1980 | Clinical | ND | PAC | ND | NML (35) |

| E-RUSS | 3 | E1 | ∼1936 | Clinical | Sturgeon intestine | UKR | Sea of Azov, Ukraine | BRS (30, 36–39) |

| MU9708EJG-F235 | 15 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Muktuk | NWT | Aklavik, NT | BRS |

| MU9708EJG-F236 | 15 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Muktuk | NWT | Aklavik, NT | BRS |

| MU0103EMS | 24 | E3 | 2001 | Clinical | Muktuk oil | NWT | Aklavik, NT | BRS |

| FE9909ERG | 22 | E3 | 1999 | Clinical | Feces | NWT | Inuvik, NT | BRS (37, 38) |

| FE0005EJT | 23 | E3 | 2000 | Clinical | Feces | NWT | Inuvik, NT | BRS (37, 38) |

| MU0005EJT | 23 | E3 | 2000 | Clinical | Muktuk | NWT | Inuvik, NT | BRS (37, 38) |

| MU8903E | 6 | E3 | 1989 | Clinical | Muktuk | NWT | Paulatuk, NT | BRS |

| SO301E | E10 | 2001 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | EHB | Kuujjuaraapik, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SO303E1 | E10 | 2001 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | EHB | Umiujaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SO303E3 | E10 | 2001 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | EHB | Umiujaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SO303E4 | E10 | 2001 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | EHB | Umiujaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SO303E5 | E10 | 2001 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | EHB | Umiujaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SO304E1 | E10 | 2003 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | EHB | Inukjuak, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SO304E2 | E10 | 2003 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | EHB | Inukjuak, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SO305E1 | E10 | 2003 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | EHB | Inukjuak, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SO305E2 | E10 | 2003 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | EHB | Inukjuak, QC | BRS(27) | |

| SO307E1 | E10 | 2003 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | EHB | Puvirnituq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SO309E2 | E10 | 2003 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | EHB | Puvirnituq, QC | BRS (27, 37, 38) | |

| SP417E-Alc | E10 | 2001 | Environmental | Coastal rock | EHB | Puvirnituq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SP417E-NT | E10 | 2001 | Environmental | Coastal rock | EHB | Puvirnituq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| BE9708E1 | 14 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Beluga | WHB | Arviat, NU | BRS |

| CA9708E1 | 14 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Caribou | WHB | Arviat, NU | BRS |

| FE9708E1JI | 14 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Feces | WHB | Arviat, NU | BRS |

| FE9708E1PI | 14 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Feces | WHB | Arviat, NU | BRS |

| GA0811E1IT | 30 | E3 | 2008 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | BI | Baffin Island, NU | BRS |

| FE0801E1IT | 30 | E3 | 2008 | Clinical | Feces | BI | Kimmirut, NU | BRS |

| Bennett | 5 | E3 | 1976 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | LAB | Happy Valley, NL | BRS (37, 38) |

| FE9908EDL | 21 | E3 | 1999 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Aupaluk, QC | BRS |

| FE9507EEA | 7 | E3 | 1995 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS (37, 38) |

| MI9507E | 7 | E3 | 1995 | Clinical | Seal misiraq | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS (37, 38) |

| FE9709EBB | 17 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS (37, 38) |

| FE9709ECB | 17 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| FE9709ELB | 17 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS (37, 38) |

| GA9709EHS | 17 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS (37, 38) |

| GA9709EJA | 17 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS (37, 38) |

| GA9709ENS | 17 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS (37, 38) |

| FE9709EBB2 | 18 | E10 | 1997 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| FE9709EKA | 18 | E10 | 1997 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| MI19709E | 18 | E10 | 1997 | Clinical | Seal igunaq | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| MI59709E | 18 | E10 | 1997 | Clinical | Seal igunaq | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| MI69709E | 18 | E10 | 1997 | Clinical | Seal igunaq | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| INGR16-02E1 | E3 | 2002 | Marine mammal | Seal intestine | UB | Kangiqsualujjuaq, QC | BRS | |

| INWB2202E1 | E3 | 2002 | Marine mammal | Seal intestine | UB | Kangiqsujuaq, QC | BRS | |

| SO321E1 | E3 | 2001 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kangirsuk, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SO322E1 | E10 | 2001 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kangirsuk, QC | BRS (27) | |

| Gordon | 4 | E3 | 1975 | Clinical | Clinical specimen | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (37, 38) |

| F9508EMA | 8 | E3 | 1995 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (37, 38) |

| VI9508E | 8 | E3 | 1995 | Clinical | Seal igunaq | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (37, 38) |

| S9510E | 10 | E3 | 1995 | Clinical | Seal meat | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (37, 38) |

| GA9811E1MS | 19 | E3 | 1998 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| GA9811E2MS | 19 | E3 | 1998 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| V9804E | 20 | E3 | 1998 | Clinical | Seal meat | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| FE0211E1DK | 27 | E3 | 2002 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| GA0702E1 | 29 | E3 | 2007 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| GA0702E1CS | 29 | E3 | 2007 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| ME0702E1CS | 29 | E3 | 2007 | Clinical | Seal meat in oil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| GA0808EPA | 31 | E3 | 2008 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| FE1010E1JL | 32 | E3 | 2010 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| GA1010E1JL | 32 | E3 | 2010 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| ME1010E1JL | 32 | E3 | 2010 | Clinical | Meat | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| GA1101E1BB | 33 | E10 | 2011 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS |

| SE9908E | E3 | 1999 | Marine mammal | Seal intestine | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS | |

| IN01SE63E1 | E3 | 2001 | Marine mammal | Seal intestine | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| MSKR5102E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Marine sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| MSKR5102E2 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Marine sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| PBKR-41E1 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Peat bog | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSKR40E1 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSKR4802E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWKR02E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWKR11E1 | E10 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSK02-01E2 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSK02-01E3 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSK02-02E1 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSK02-03E1 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSK02-04E1 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSK02-05E1 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSK02-05E2 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSK02-06E1 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSK02-06E2 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSK02-07E1 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSK02-07E2 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSK02-08E1 | E10 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FWSKR1302E1 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| RSKR-68E1 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Coastal rock | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| RSKR-68E2 | E10 | 2004 | Environmental | Coastal rock | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| RSKR-68E3 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Coastal rock | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SO329E1 | E11 | 2001 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27, 37, 38) | |

| SO329E2 | E11 | 2001 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-14E1 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-14E3 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-18E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-19E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-20E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-22E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-22E3 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-23E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Marine sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27, 37, 38) | |

| SOKR-23E3 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Marine sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-24E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Marine sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-24E2 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Marine sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-24E3 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Marine sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-25E2 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-25E3 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-27E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-27E3 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-29E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27, 37, 38) | |

| SOKR-29E2 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-33E1 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Peat bog | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-34E1 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-34E5 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-35E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-35E3 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-37E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Freshwater sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-38E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Marine sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-38E2 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Marine sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-38E3 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Marine sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-42E1 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-43E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-43E2 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-44E1 | E11 | 2002 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-44E2 | E11 | 2002 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-44E3 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-46E1 | E11 | 2004 | Environmental | Marine sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-46E3 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Marine sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-49E1 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-49E2 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Sediment | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-50E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SOKR-50E2 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SP455–456E2 | E11 | 2002 | Environmental | Coastal rock | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27, 37, 38) | |

| SP457–458E | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Coastal rock | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SW279E | E3 | 2001 | Environmental | Seawater | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SW280E | E11 | 2001 | Environmental | Seawater | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27, 37, 38) | |

| SWKR0402E1 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Seawater | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SWKR0402E2 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Seawater | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SWKR07E1 | E3 | 2004 | Environmental | Seawater | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SWKR24E1 | E11 | 2004 | Environmental | Seawater | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SWKR38E1 | E10 | 2004 | Environmental | Seawater | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SWKR38E2 | E10 | 2004 | Environmental | Seawater | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| TRK02-02E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| TRK02-02E2 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| TRK02-03E2 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| TRK02-04E1 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| TRK02-04E3 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| TRK02-06E2 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| TRK02-06E3 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| TRK02-07E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| TRK02-08E1 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| TRK02-08E2 | E11 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| TRK02-08E3 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| TRK0208E3 | E10 | 2002 | Environmental | Terrestrial soil | UB | Kuujjuaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| FE9604ENT | 11 | E3 | 1996 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Quaqtaq, QC | BRS |

| GA9604EAK | 11 | E3 | 1996 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Quaqtaq, QC | BRS |

| GA9604ESM | 11 | E3 | 1996 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Quaqtaq, QC | BRS |

| F9508EPB | 9 | E3 | 1995 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS (37, 38) |

| MI9608ESM | 12 | E3 | 1996 | Clinical | Seal meat | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| GA9608EPB | 13 | E3 | 1996 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| VI9608EPB | 13 | E3 | 1996 | Clinical | Seal meat | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| GA9706EMA | 16 | E10 | 1997 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| MI9706E | 16 | E3 | 1997 | Clinical | Igunaq | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| GA0108EJC | 25 | E3 | 2001 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| FE0201E1BC | 26 | E3 | 2002 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| FE0202E1TC | 26 | E3 | 2002 | Clinical | Feces | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| GA0202E1TS | 26 | E3 | 2002 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| IG0201E2BC | 26 | E3 | 2002 | Clinical | Walrus igunaq | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| IG0202E1 | 26 | E3 | 2002 | Clinical | Walrus igunaq | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| VO0202E1TC | 26 | E3 | 2002 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| GL0410E1LC | 28 | E3 | 2004 | Clinical | Gastric liquid | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| IG0410E2LC | 28 | E3 | 2004 | Clinical | Igunaq | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| IG0410E3LC | 28 | E3 | 2004 | Clinical | Igunaq | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS |

| SO325E | E3 | 2001 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS (27) | |

| SO325E1 | E3 | 2001 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS (27, 37, 38) | |

| SO326E1 | E3 | 2001 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS (27, 37, 38) | |

| SOKR-3602E1 | E3 | 2002 | Environmental | Shoreline soil | UB | Tasiujaq, QC | BRS (27) |

Isolates (n = 175) were derived from samples collected during an outbreak (OB) investigation. Abbreviations: PAC, Pacific Coast; UKR, Ukraine; WHB, West Hudson Bay Coast; EHB, East Hudson Bay Coast; UB, Ungava Bay Coast; LAB, Labrador; BI, Baffin Island; QC, Quebec, Canada; ND, no details; BRS, Botulism Reference Service, Health Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; NML, National Microbiology Laboratory, Public Health Agency of Canada, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. References are indicated (parentheses).

Mouse bioassay.

Mouse lethal dose (MLD) titers of botulinum neurotoxin were determined using 10-fold dilutions of culture supernatants in gelatin phosphate buffer according to standard methods (19).

bont coding sequence (CDS) determination and analysis.

SMALT v0.6.4 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/software/smalt/) was used to map reads to a genomic bont/E sequence (GenBank accession number EF028403) which included 2-kb flanking genomic region from Alaska E43 (NC_010723), and a Perl script using SamTools was used to obtain bont/E consensus CDS (filters: mapping q-score ≥ 20; base pair q-score ≥ 30; pileup ≥ 2) (20). Regions with gaps/low coverage were closed using PCR sequencing as described previously (1). Manual confirmation of variants was performed using IGV v2.0.24 (21) and Tablet v1.12.12.05 (22). Unique bont/E CDSs and translated bont/E amino acid sequences were identified using CD-Hit v4.6 (length/identity = 100%) (23). Illustrative multiple sequence alignments (see Fig. 2) were constructed in CLC Genomics Workbench v6.0.2.

FIG 2.

CDS alignment depicting the distribution of nucleotide substitutions within bont/E1, bont/E3, and bont/E10 variants. Nucleotide substitutions (|), silent substitutions (×), and codon deletions (△) identified among bont/E variant CDSs indicated on the left (E1, italics; E3, regular font; E10, underlined) compared against reference sequences (E1, accession number X62683; E3, accession number EF028403; and E10, accession number KF861887) are shown.

Phylogeny analysis.

Maximum likelihood analysis of alignment files from ClustalW (v2.1) (24) was performed with RAxML (v7.2.8) (25) using a JTT+G substitution model for amino acids, and images were rendered in FigTree (v1.3.1) (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All bont CDSs (accession numbers in Table 2) identified in this study have been deposited in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Reference sequences for each bont/E gene variant were as follows: bont/E1, X62683; bont/E2, EF028404; bont/E3, EF028403; bont/E4, X62088; bont/E5, AB037711; bont/E6, AM695759; bont/E7, JN695729; bont/E8, JN695730; and bont/E9, JX424534. Unless otherwise specified, all accession numbers in this article are GenBank accession numbers.

TABLE 2.

bont/E CDS accession numbers of C. botulinum group II strains studied

| Isolate | bont/E CDS GenBank accession no. | Variant type |

|---|---|---|

| E-RUSS | KF861870 | E1 |

| E1 Dolman | KF861868 | E1 |

| FE9709EBB2 | KF861917 | E10 |

| FWKR11E1 | KF861887 | E10 |

| FWSKR40E1 | KF861906 | E10 |

| GA1101E1BB | KF861907 | E10 |

| GA9706EMA | KF861885 | E10 |

| MI19709E | KF861914 | E10 |

| MI59709E | KF861915 | E10 |

| MI69709E | KF861919 | E10 |

| PBKR-41E1 | KF861912 | E10 |

| SO301E | KF861902 | E10 |

| SO303E1 | KF861901 | E10 |

| SO303E3 | KF861900 | E10 |

| SO303E4 | KF861899 | E10 |

| SO303E5 | KF861897 | E10 |

| SO304E1 | KF861908 | E10 |

| SO304E2 | KF861909 | E10 |

| SO305E1 | KF861910 | E10 |

| SO307E1 | KF861918 | E10 |

| SO309E2 | KF861892 | E10 |

| SO322E1 | KF861893 | E10 |

| SOKR-33E1 | KF861891 | E10 |

| SOKR-34E1 | KF878263 | E10 |

| SOKR-34E5 | KF861895 | E10 |

| SOKR-49E1 | KF861896 | E10 |

| SP417E-Alc | KF861898 | E10 |

| SP417E-NT | KF861894 | E10 |

| SWKR38E1 | KF861888 | E10 |

| SWKR38E2 | KF861889 | E10 |

| TRK02-03E2 | KF861904 | E10 |

| TRK02-04E1 | KF861905 | E10 |

| TRK02-08E1 | KF861921 | E10 |

| TRK02-08E3 | KF861922 | E10 |

| TRK0208E3 | KF861886 | E10 |

| FE9709EKA | KF861916 | E10 |

| SOKR-49E2 | KF861890 | E10 |

| FWSK02-08E1 | KF861903 | E10 |

| SO305E2 | KF861911 | E10 |

| RSKR-68E2 | KF861913 | E10 |

| SOKR-42E1 | KF878264 | E10 |

| SO329E1 | KF861875 | E11 |

| SO329E2 | KF861882 | E11 |

| SOKR-44E1 | KF861872 | E11 |

| SOKR-44E2 | KF861874 | E11 |

| SOKR-46E1 | KF861883 | E11 |

| SP455-456E2 | KF861876 | E11 |

| SW280E | KF861877 | E11 |

| SWKR24E1 | KF861873 | E11 |

| TRK02-08E2 | KF861871 | E11 |

| BE9708E1 | KF719438 | E3 |

| Bennett | KF719445 | E3 |

| CA9708E1 | KF719439 | E3 |

| F9508EMA | KF719431 | E3 |

| F9508EPB | KF719430 | E3 |

| FE0005EJT | KF719347 | E3 |

| FE0201E1BC | KF719412 | E3 |

| FE0202E1TC | KF719420 | E3 |

| FE0211E1DK | KF719349 | E3 |

| FE0801E1IT | KF719342 | E3 |

| FE1010E1JL | KF719341 | E3 |

| FE9507EEA | KF719443 | E3 |

| FE9604ENT | KF719428 | E3 |

| FE9708E1JI | KF719441 | E3 |

| FE9708E1PI | KF719440 | E3 |

| FE9709EBB | KF719328 | E3 |

| FE9709ECB | KF719324 | E3 |

| FE9709ELB | KF719329 | E3 |

| FE9908EDL | KF719333 | E3 |

| FE9909ERG | KF719330 | E3 |

| FWKR02E1 | KF719350 | E3 |

| FWSK02-01E3 | KF719386 | E3 |

| FWSK02-02E1 | KF719403 | E3 |

| FWSK02-03E1 | KF719401 | E3 |

| FWSK02–04E1 | KF719361 | E3 |

| FWSK02-05E1 | KF719365 | E3 |

| FWSK02-05E2 | KF719366 | E3 |

| FWSK02-06E1 | KF719415 | E3 |

| FWSK02-06E2 | KF719409 | E3 |

| FWSK02-07E1 | KF719408 | E3 |

| FWSK02-07E2 | KF719407 | E3 |

| FWSKR1302E1 | KF719404 | E3 |

| FWSKR4802E1 | KF719336 | E3 |

| GA0108EJC | KF719411 | E3 |

| GA0202E1TS | KF719419 | E3 |

| GA0702E1CS | KF719327 | E3 |

| GA0808EPA | KF719343 | E3 |

| GA0811E1IT | KF719346 | E3 |

| GA1010E1JL | KF719339 | E3 |

| GA9604EAK | KF719427 | E3 |

| GA9604ESM | KF719426 | E3 |

| GA9608EPB | KF719435 | E3 |

| GA9709EJA | KF719326 | E3 |

| GA9709ENS | KF719325 | E3 |

| GA9811E1MS | KF719422 | E3 |

| GA9811E2MS | KF719421 | E3 |

| Gordon | KF719444 | E3 |

| IG0201E2BC | KF719413 | E3 |

| IG0202E1 | KF719417 | E3 |

| IG0410E2LC | KF719348 | E3 |

| IG0410E3LC | KF719410 | E3 |

| IN01SE63E1 | KF719370 | E3 |

| INWB2202E1 | KF719369 | E3 |

| ME0702E1CS | KF719345 | E3 |

| ME1010E1JL | KF719340 | E3 |

| MI9608ESM | KF719437 | E3 |

| MI9706E | KF719425 | E3 |

| MSKR5102E1 | KF719406 | E3 |

| MSKR5102E2 | KF719405 | E3 |

| MU0005EJT | KF719331 | E3 |

| MU0103EMS | KF719423 | E3 |

| MU8903E | KF719322 | E3 |

| MU9708EJG-F235 | KF719436 | E3 |

| RSKR-68E1 | KF719334 | E3 |

| RSKR-68E3 | KF719335 | E3 |

| S9510E | KF719429 | E3 |

| SE9908E | KF719372 | E3 |

| SO325E | KF719376 | E3 |

| SO325E1 | KF719394 | E3 |

| SO326E1 | KF719395 | E3 |

| SOKR-14E1 | KF719357 | E3 |

| SOKR-14E3 | KF719356 | E3 |

| SOKR-18E1 | KF719368 | E3 |

| SOKR-20E1 | KF719362 | E3 |

| SOKR-22E1 | KF719383 | E3 |

| SOKR-22E3 | KF719384 | E3 |

| SOKR-23E1 | KF719392 | E3 |

| SOKR-23E3 | KF719397 | E3 |

| SOKR-24E1 | KF719390 | E3 |

| SOKR-24E2 | KF719402 | E3 |

| SOKR-24E3 | KF719414 | E3 |

| SOKR-25E2 | KF719400 | E3 |

| SOKR-25E3 | KF719399 | E3 |

| SOKR-27E1 | KF719323 | E3 |

| SOKR-27E3 | KF719364 | E3 |

| SOKR-29E1 | KF719389 | E3 |

| SOKR-29E2 | KF719396 | E3 |

| SOKR-35E1 | KF719373 | E3 |

| SOKR-35E3 | KF719374 | E3 |

| SOKR-3602E1 | KF719337 | E3 |

| SOKR-38E1 | KF719355 | E3 |

| SOKR-38E2 | KF719354 | E3 |

| SOKR-38E3 | KF719353 | E3 |

| SOKR-43E1 | KF719387 | E3 |

| SOKR-43E2 | KF719380 | E3 |

| SOKR-44E3 | KF719391 | E3 |

| SOKR-46E3 | KF719351 | E3 |

| SOKR-50E1 | KF719381 | E3 |

| SOKR-50E2 | KF719382 | E3 |

| SW279E | KF719367 | E3 |

| SWKR0402E1 | KF719338 | E3 |

| SWKR0402E2 | KF719393 | E3 |

| SWKR07E1 | KF719332 | E3 |

| TRK02-02E1 | KF719358 | E3 |

| TRK02-02E2 | KF719359 | E3 |

| TRK02-04E3 | KF719360 | E3 |

| TRK02-06E2 | KF719377 | E3 |

| TRK02-06E3 | KF719320 | E3 |

| V9804E | KF719424 | E3 |

| VI9508E | KF719432 | E3 |

| VI9608EPB | KF719434 | E3 |

| VO0202E1TC | KF719416 | E3 |

| GA0702E1 | KF719352 | E3 |

| SO321E1 | KF719398 | E3 |

| SOKR-37E1 | KF719344 | E3 |

| MI9507E | KF719433 | E3 |

| SP457-458E8 | KF719375 | E3 |

| 211 VH Dolman | KF719447 | E3 |

| MU9708EJG-F236 | KF719418 | E3 |

| GL0410E1LC | KF719446 | E3 |

| FWSK02-01E2 | KF719385 | E3 |

| INGR16-02E1 | KF719371 | E3 |

| SOKR-19E1 | KF719378 | E3 |

| TRK02-07E1 | KF719379 | E3 |

| GA9709EHS | KF878262 | E3 |

RESULTS

BoNT/E variant analysis.

The rate of food-borne botulism is notably high in certain northern communities (18, 26). Frequent, distinct botulism type E outbreaks in the Ungava Bay region have been reported (18), and a costal environmental sampling study has shown that C. botulinum spore counts can range from 270 to 1,800/kg in this area (27).

A total of 175 full-length bont/E CDSs were determined for clinical (n = 45), food (n = 21), marine mammal (n = 4), and environmental (n = 105) C. botulinum type E isolates from northern Canada (primarily from the banks of East Hudson Bay and Ungava Bay) (27), as well as isolates from the Pacific coast (211 VH Dolman, E1 Dolman) and the littoral of the Sea of Azov (E-RUSS) (Tables 1 and 2).

Sequence analysis of bont/E CDSs show clustering with previously described bont/E1 and bont/E3 variant types, as well as two distinct clades, termed E10 and E11; none of the other variants (E2 and E4 to E9) were represented. For the 175 type E isolates compared, 1.1% (n = 2) of the bont/E sequences cluster with E1, 71.4% (n = 125) with E3, 22.3% (n = 39) with E10, and 5.1% (n = 9) with E11 (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Dendrogram comparing unique full-length bont/E CDSs from the current study to sequences of known bont/E variants (*) using RAxML (1,000 bootstraps). Accession numbers of the bont/E CDSs used for analysis are shown. Two clusters are distinct from bont/E variants E1 to E9 and are termed E10 and E11. The occurrence of each sequence is indicated (parentheses).

Within the bont/E3 cluster, nine unique CDSs were observed, the predominant one being identical to the publicly available sequence of strain Alaska E43 (accession number EF028403). Two bont/E3 CDSs (accession numbers KF719446 and KF719385) maintain the predicted amino acid sequence reported for Alaska E43, while five (accession numbers KF719418, KF719371, KF719378, KF719379, and KF878262) encode single amino acid substitutions and one (accession number KF719447) encodes two amino acid substitutions (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Amino acid variation within predicted BoNT/E3 variants is <0.2% (1 or 2 nucleotide substitutions; 0 to 2 amino acid substitutions). The variability does not appear localized to any domain.

Six different full-length CDS variants were identified in the bont/E10 cluster. The dominant form (corresponding to accession number KF861887) was highly represented (n = 33), while other forms were observed at a low frequency (Fig. 1). Predicted BoNT/E10 amino acid sequences varied by ≤0.56% (1 to 7 nucleotide substitutions; 1 to 7 amino acid substitutions) and are primarily localized to the receptor-binding domain (Fig. 2). A polymorphic site was also observed at position 3647/3648. No sequence variation was observed for bont/E CDSs in the E1 or E11 clusters.

At the amino acid level, the variant types E10 and E11 vary from all other E variants by 2.1 to 11.0%. The translated amino acid sequence of bont/E10 (accession number KF861887) resembles most closely variant E8, found present in an isolate from Lake Erie (2) (97.9%). When variant BoNT/E10 domains are considered separately, they are most similar to those of variant E8 (97.9%, 99.5%, and 96.4% identity for LC, HN, and HC, respectively). The overall translated amino acid sequence of bont/E11 is the most similar to BoNT/E10 (95.7% identity). At the level of the functional domains, BoNT/E11 domains are similar to those of BoNT/E10 (95.0% and 97.1% identical for LC and HC, respectively) and BoNT/E6 (95.2% identical for HN). A complete amino acid sequence identity comparison between BoNT variants E1 to E11 is presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Nucleic acid and amino acid comparison of BoNT/E variantsa

| Domain | % identity |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BoNT variant | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | E8 | E9 | E10 | E11 | |

| Holotoxin (1-3,756 nt/1-1,252 aa) | E1 | 99.4 | 99.3 | 98.5 | 98.2 | 98.5 | 99.1 | 97.9 | 94.1 | 97.6 | 96.8 | |

| E2 | 99.1 | 98.7 | 98.2 | 97.9 | 98.3 | 98.5 | 98.5 | 94.0 | 97.9 | 97.1 | ||

| E3 | 98.2 | 97.4 | 97.8 | 97.6 | 98.0 | 98.8 | 97.6 | 93.9 | 97.3 | 96.4 | ||

| E4 | 97.3 | 97.0 | 95.6 | 97.1 | 98.3 | 98.1 | 97.9 | 94.5 | 97.4 | 96.6 | ||

| E5 | 96.9 | 96.3 | 95.1 | 94.9 | 97.2 | 97.3 | 96.9 | 94.3 | 96.7 | 96.0 | ||

| E6 | 97.0 | 96.8 | 95.9 | 96.9 | 94.8 | 98.2 | 98.3 | 93.7 | 97.8 | 96.8 | ||

| E7 | 97.9 | 97.1 | 97.4 | 96.2 | 94.8 | 96.4 | 98.8 | 94.0 | 98.3 | 96.9 | ||

| E8 | 96.2 | 97.0 | 95.7 | 96.1 | 94.1 | 96.8 | 98.3 | 94.0 | 99.0 | 97.4 | ||

| E9 | 89.1 | 89.3 | 88.7 | 89.9 | 89.4 | 88.2 | 89.1 | 89.4 | 94.1 | 94.3 | ||

| E10 | 95.4 | 95.8 | 94.7 | 94.8 | 93.4 | 95.6 | 96.8 | 97.9 | 89.4 | 97.9 | ||

| E11 | 93.4 | 93.8 | 92.6 | 92.7 | 91.9 | 93.1 | 93.5 | 94.4 | 89.0 | 95.7 | ||

| LC (1-1,260 nt/1-420 aa) | E1 | 99.9 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 98.7 | 98.7 | 97.4 | 97.4 | 95.4 | 97.3 | 96.7 | |

| E2 | 99.8 | 97.9 | 97.8 | 99.9 | 98.6 | 97.4 | 97.4 | 95.3 | 97.2 | 96.6 | ||

| E3 | 94.8 | 94.5 | 95.9 | 97.9 | 97.2 | 96.5 | 96.5 | 94.8 | 96.3 | 95.6 | ||

| E4 | 96.0 | 95.7 | 91.0 | 97.9 | 96.8 | 96.8 | 96.8 | 96.5 | 96.6 | 96.0 | ||

| E5 | 100.0 | 99.8 | 94.8 | 96.0 | 98.7 | 97.4 | 97.4 | 95.4 | 97.3 | 96.7 | ||

| E6 | 96.7 | 96.4 | 93.3 | 93.6 | 96.7 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 94.7 | 97.6 | 96.3 | ||

| E7 | 94.0 | 94.0 | 92.4 | 92.9 | 94.0 | 95.0 | 100.0 | 95.5 | 99.3 | 97.0 | ||

| E8 | 94.0 | 94.0 | 92.4 | 92.9 | 94.0 | 95.0 | 100.0 | 95.5 | 99.3 | 97.0 | ||

| E9 | 90.5 | 90.2 | 89.3 | 92.4 | 90.5 | 88.8 | 91.0 | 91.0 | 95.4 | 95.2 | ||

| E10 | 93.8 | 93.6 | 91.9 | 92.1 | 93.8 | 94.3 | 97.9 | 97.9 | 90.7 | 97.7 | ||

| E11 | 92.4 | 92.1 | 90.0 | 90.7 | 92.4 | 91.2 | 92.9 | 92.9 | 89.5 | 95.0 | ||

| HN (1,261-2,499 nt/421-833 aa) | E1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.0 | 98.6 | 98.1 | 99.8 | 98.4 | 95.8 | 98.7 | 97.0 | |

| E2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.0 | 98.6 | 98.1 | 99.8 | 98.4 | 95.8 | 98.7 | 97.0 | ||

| E3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.0 | 98.6 | 98.1 | 99.8 | 98.4 | 95.8 | 98.7 | 97.0 | ||

| E4 | 98.3 | 98.3 | 98.3 | 98.5 | 98.4 | 98.8 | 98.8 | 96.4 | 99.1 | 97.4 | ||

| E5 | 97.8 | 97.8 | 97.8 | 98.1 | 97.7 | 98.4 | 97.9 | 96.3 | 98.2 | 96.6 | ||

| E6 | 97.1 | 97.1 | 97.1 | 97.8 | 96.9 | 98.1 | 98.9 | 95.6 | 99.1 | 97.6 | ||

| E7 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 98.1 | 97.6 | 96.9 | 98.6 | 95.6 | 98.9 | 97.0 | ||

| E8 | 97.3 | 97.3 | 97.3 | 98.1 | 97.1 | 98.3 | 97.6 | 95.6 | 99.7 | 97.3 | ||

| E9 | 93.5 | 93.5 | 93.5 | 94.7 | 93.7 | 93.0 | 93.2 | 93.2 | 95.8 | 95.6 | ||

| E10 | 97.8 | 97.8 | 97.8 | 98.6 | 97.6 | 98.8 | 98.1 | 99.5 | 93.7 | 97.5 | ||

| E11 | 94.2 | 94.2 | 94.2 | 94.4 | 94.0 | 95.2 | 94.0 | 94.9 | 92.0 | 94.9 | ||

| HC (2,500-3,756 nt/834-1,252 aa) | E1 | 98.3 | 100.0 | 98.6 | 96.2 | 98.7 | 100.0 | 97.9 | 91.0 | 96.8 | 96.6 | |

| E2 | 97.6 | 98.3 | 98.0 | 95.2 | 98.1 | 98.3 | 99.6 | 90.9 | 97.8 | 97.7 | ||

| E3 | 100.0 | 97.6 | 98.6 | 96.2 | 98.7 | 100.0 | 97.9 | 91.0 | 96.8 | 96.6 | ||

| E4 | 97.6 | 97.1 | 97.6 | 95.1 | 99.6 | 98.6 | 98.1 | 90.6 | 96.6 | 96.4 | ||

| E5 | 92.8 | 91.4 | 92.8 | 90.7 | 95.3 | 96.2 | 95.4 | 91.3 | 94.7 | 94.8 | ||

| E6 | 97.4 | 96.9 | 97.4 | 99.3 | 90.9 | 98.7 | 98.2 | 91.0 | 96.7 | 96.6 | ||

| E7 | 100.0 | 97.6 | 100.0 | 97.6 | 92.8 | 97.4 | 97.9 | 91.0 | 96.8 | 96.6 | ||

| E8 | 97.4 | 99.8 | 97.4 | 97.4 | 91.2 | 97.1 | 97.4 | 91.0 | 98.2 | 97.9 | ||

| E9 | 83.3 | 84.3 | 83.3 | 82.6 | 84.2 | 82.8 | 83.3 | 84.0 | 91.2 | 92.0 | ||

| E10 | 94.5 | 96.2 | 94.5 | 93.8 | 88.8 | 93.8 | 94.5 | 96.4 | 83.8 | 98.5 | ||

| E11 | 93.6 | 95.2 | 93.6 | 92.8 | 89.5 | 93.1 | 93.6 | 95.5 | 85.4 | 97.1 | ||

Percent identity of nucleotide (boldface) and amino acid (lightface) sequences for bont/E CDS variants. Comparative values for the BoNT/E holotoxin and each domain (light chain [LC], translocation [HN], and receptor-binding [HC]) are presented. Strains (with sequences and accession numbers in parentheses) used for comparison are as follows: Beluga (E1, X62683), CDC5247 (E2, EF028404), Alaska E43 (E3, EF028403), BL5262 (E4, X62088), LCL155 (E5, AB037711), K35 (E6, AM695759), IBCA97-0192 (E7, JN695729), NYDH Bac-02-06430 (E8, JN695730), CDC66177 (E9, JX424534), FWKR11E1 (E10, KF861887), and SW280E (E11, KF861877). aa, amino acids.

Multiple-sequence alignments of variant bont/E CDSs were analyzed to examine the distribution of nucleotide substitution events (Fig. 3). The differences between bont/E10 and bont/E11 variant sequences and the other bont/E variant subtypes display a nonrandom substitution pattern. Extensive portions of the LC and HC are identical in bont/E10 and bont/E11 variants. Likewise, a significant region of the HN of bont/E10 was identical in all other bont/E variants except bont/E9 and bont/E11.

FIG 3.

bont/E CDS alignment depicting the distribution of nucleotide substitutions among variants. The reference sequence used for each of the 11 alignments is indicated (left and Table 3), and horizontal tracks represent the alignment for each variant sequence (right). A scale bar denoting nucleotide position and catalytic light chain (LC), translocation (HN), and receptor binding (HC) domains is shown. The vertical lines plotted along the tracks indicate nucleotide substitutions (A, red; C, blue; G, yellow; T, green).

Geographic distribution of BoNT/E variants.

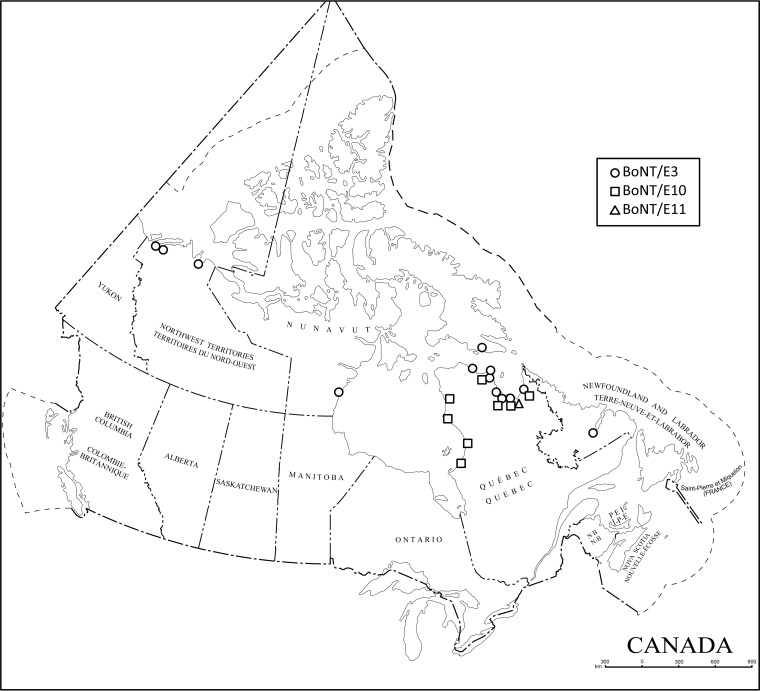

BoNT/E3 variant-carrying strains were isolated from outbreak-related clinical and/or food samples originating from British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut (West Hudson Bay and Baffin Island), Labrador, and Quebec (Ungava Bay) (Fig. 4 and Table 1). BoNT/E3 environmental isolates were also obtained from the seaside along the Ungava Bay but were completely absent from the four East Hudson Bay shoreline sites surveyed. Only E10 isolates were identified from environmental samples collected from the eastern strand of East Hudson Bay. Although the Botulism Reference Service for Canada obtained positive results from clinical isolates related to a botulism case in this area in 1996, no isolates were recovered. E10 strains were also isolated from environmental samples from the Ungava Bay region where E10-related outbreaks were reported. The E11 variant was identified exclusively in environmental samples from the surroundings of the Koksoak River, a tributary of Ungava Bay, despite an extensive sampling effort along the Nunavik coastline. Moreover, no E11 strains were associated with a botulism outbreak.

FIG 4.

Distribution of BoNT/E C. botulinum. The locations of origin for Canadian BoNT/E C. botulinum characterized in this study (Table 1) are shown. The BoNT/E variant type is indicated (legend, inset). Map source: Natural Resources Canada (http://atlas.gc.ca).

Toxicity of C. botulinum BoNT/E11-producing strains.

To determine if the apparent lack of an outbreak associated with E11 strains was related to their toxicity, 10-fold dilutions of culture supernatants from selected BoNT/E variants were assayed using the mouse bioassay. C. botulinum strains harboring BoNT/E1 (n = 2) and BoNT/E3 (n = 9) variants produced 103 to 105 and 102 to 105 mouse lethal doses (MLDs) per 0.5 ml of culture supernatant, respectively. BoNT/E11 (n = 7) and BoNT/E10 (n = 19) demonstrated reduced toxicity, with 102 to 104 and 101 to 103 MLDs per 0.5 ml (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Mouse lethal doses of BoNT/E variants

| Strain | BoNT variant | MLDa |

|---|---|---|

| E-RUSS | E1 | 104–105 |

| E1 Dolman | E1 | 103–104 |

| Bennett | E3 | 104–105 |

| Gordon | E3 | 104–105 |

| RSKR-68E1 | E3 | 104–105 |

| FE0005EJT | E3 | 103–104 |

| FE9708E1PI | E3 | 103–104 |

| GA9608EPB | E3 | 103–104 |

| MU8903E | E3 | 103–104 |

| INGR16-02E1 | E3 | 103–104 |

| FE9604ENT | E3 | 102–103 |

| SO329E1 | E11 | 103–104 |

| SOKR-44E1 | E11 | 103–104 |

| SW280E | E11 | 103–104 |

| SOKR-44E2 | E11 | 102–103 |

| SOKR-46E1 | E11 | 102–103 |

| SWKR24E1 | E11 | 102–103 |

| TRK02-08E2 | E11 | 102–103 |

| SO301E | E10 | 102–103 |

| SO303E5 | E10 | 102–103 |

| SO322E1 | E10 | 102–103 |

| SOKR-49E1 | E10 | 102–103 |

| SP417E-NT | E10 | 102–103 |

| SWKR38E1 | E10 | 102–103 |

| TRK02-04E1 | E10 | 102–103 |

| SO305E2 | E10 | 102–103 |

| RSKR-68E2 | E10 | 102–103 |

| FWKR11E1 | E10 | 101–102 |

| GA1101E1BB | E10 | 101–102 |

| MI69709E | E10 | 101–102 |

| SO303E1 | E10 | 101–102 |

| SO303E4 | E10 | 101–102 |

| SOKR-34E5 | E10 | 101–102 |

| SOKR-46E2 | E10 | 101–102 |

| SOKR-49E2 | E10 | 101–102 |

| TRK02-03E2 | E10 | 101–102 |

| FE9709EKA | E10 | 101–102 |

MLD per 0.5 ml of supernatant.

DISCUSSION

BoNT CDS variant determination was performed using phylogeny and further analyzed by nucleotide and amino acid identity analysis. E1 and E3, as well as two new toxin variants which we termed E10 and E11, were identified. Differences between newly identified bont/E10 and bont/E11 sequences and the other bont/E variants were not randomly distributed. For instance, the translocation domain of E10 is highly homologous to that found in all variants except E9 and E11, while large portions of its catalytic and receptor-binding domains are identical to those of E11. Such patterns suggest the occurrence of recombination events and have been previously reported for other bont genes, including bont/E variants, and toxin gene clusters (2, 9, 15, 28). The frequency of nucleotide substitutions observed within variants E10 (1 to 7 nucleotides) and E3 (1 or 2 nucleotides) is similar to that reported for variant B4 (1 to 5 nucleotides), a toxin variant generally associated with nonproteolytic C. botulinum (29).

Considering such a broad distribution, it is noteworthy that only 2 of the 175 strains included in our study (E1 Dolman, Pacific coast [30] E-RUSS, Sea of Azov [31]) encode BoNT/E1. E1 strains have been previously isolated in Washington State, Alaska, Labrador, Greenland, Denmark, Finland, and Japan (2, 12, 32). The vast majority of strains included in this study encode the BoNT/E3 variants, which were observed in environmental isolates from Ungava Bay as well as clinical and/or food isolates from British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, West Hudson Bay, Baffin Island, Labrador, and Ungava Bay. This widespread distribution throughout Canada is consistent with reports of E3 identification in samples from Alaska, the Great Lakes, Illinois, Finland, France, and Japan (2, 12, 14, 33). No E3 variants were identified among the 13 environmental isolates from four East Hudson Bay locales, which were all E10 variants. The latter were also observed in clinical and environmental samples from the Ungava Bay region. E11 isolates, however, were identified exclusively in environmental samples collected in the vicinity of the Koksoak River. The environmental survey focused on the Nunavik region (27); variants E10, E11, and other variant subtypes may be present in other areas of Canada.

Curiously, no outbreaks were associated with the BoNT/E11 variant. Intrinsic differences between C. botulinum type E strains, such as growth rate, toxin secretion, and toxin efficacy, may be responsible for the toxicity ranges observed. No game animals, to be used in the preparation of high-risk traditional aged-meat dishes, were butchered in the area where E11 strains were collected (18, 34). No high-risk traditional aged-meat dishes implicated in type E outbreaks from Kuujjuaq or the Ungava Bay area were found to be contaminated with E11 strains. BoNT/E3 strains were also found in the environment of the three butchering sites where BoNT/E11 were isolated (18, 34). The predominance and widespread distribution of other variants in the environment, in particular BoNT/E3, may explain the lack of human E11 cases reported to date. Likewise, no human botulism cases have been linked to strains harboring bont/E8 or bont/E9; these variants were identified in environmental isolates from the Great Lakes (2) and Dolavon, Chubut, Argentina, respectively (14). The identification and distribution of BoNT variants can provide insights during clinical investigations and can be applied to develop robust therapeutic and diagnostic technologies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Canadian Safety and Security Program project 07-219RD from Defense Research and Development Canada.

We thank Greg Sanders for technical assistance in performing mouse neutralization assays and members of the Genomics Core Services Group at the National Microbiology Laboratory (Winnipeg, Manitoba), headed by Morag Graham, for sequencing runs performed on the GAIIx instrument.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 August 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Hill KK, Smith TJ, Helma CH, Ticknor LO, Foley BT, Svensson RT, Brown JL, Johnson EA, Smith LA, Okinaka RT, Jackson PJ, Marks JD. 2007. Genetic diversity among botulinum neurotoxin-producing clostridial strains. J. Bacteriol. 189:818–832. 10.1128/JB.01180-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macdonald TE, Helma CH, Shou Y, Valdez YE, Ticknor LO, Foley BT, Davis SW, Hannett GE, Kelly-Cirino CD, Barash JR, Arnon SS, Lindstrom M, Korkeala H, Smith LA, Smith TJ, Hill KK. 2011. Analysis of Clostridium botulinum serotype E strains by using multilocus sequence typing, amplified fragment length polymorphism, variable-number tandem-repeat analysis, and botulinum neurotoxin gene sequencing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:8625–8634. 10.1128/AEM.05155-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barash JR, Arnon SS. 2014. A novel strain of Clostridium botulinum that produces type B and type H botulinum toxins. J. Infect. Dis. 209:183–191. 10.1093/infdis/jit449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dover N, Barash JR, Hill KK, Xie G, Arnon SS. 2014. Molecular characterization of a novel botulinum neurotoxin type H gene. J. Infect. Dis. 209:192–202. 10.1093/infdis/jit449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossetto O, Megighian A, Scorzeto M, Montecucco C. 2013. Botulinum neurotoxins. Toxicon 67:31–36. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tighe AP, Schiavo G. 2013. Botulinum neurotoxins: mechanism of action. Toxicon 67:87–93. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raphael BH, Choudoir MJ, Luquez C, Fernandez R, Maslanka SE. 2010. Sequence diversity of genes encoding botulinum neurotoxin type F. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:4805–4812. 10.1128/AEM.03109-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill KK, Smith TJ. 2013. Genetic diversity within Clostridium botulinum serotypes, botulinum neurotoxin gene clusters and toxin subtypes. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 364:1–20. 10.1007/978-3-642-33570-9_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter AT, Paul CJ, Mason DR, Twine SM, Alston MJ, Logan SM, Austin JW, Peck MW. 2009. Independent evolution of neurotoxin and flagellar genetic loci in proteolytic Clostridium botulinum. BMC Genomics 10:115. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith TJ, Lou J, Geren IN, Forsyth CM, Tsai R, LaPorte SL, Tepp WH, Bradshaw M, Johnson EA, Smith LA, Marks JD. 2005. Sequence variation within botulinum neurotoxin serotypes impacts antibody binding and neutralization. Infect. Immun. 73:5450–5457. 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5450-5457.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arndt JW, Jacobson MJ, Abola EE, Forsyth CM, Tepp WH, Marks JD, Johnson EA, Stevens RC. 2006. A structural perspective of the sequence variability within botulinum neurotoxin subtypes A1-A4. J. Mol. Biol. 362:733–742. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Korkeala H, Aarnikunnas J, Lindstrom M. 2007. Sequencing the botulinum neurotoxin gene and related genes in Clostridium botulinum type E strains reveals orfx3 and a novel type E neurotoxin subtype. J. Bacteriol. 189:8643–8650. 10.1128/JB.00784-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins MD, East AK. 1998. Phylogeny and taxonomy of the food-borne pathogen Clostridium botulinum and its neurotoxins. J. Appl. Microbiol. 84:5–17. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raphael BH, Lautenschlager M, Kalb SR, de Jong LI, Frace M, Luquez C, Barr JR, Fernandez RA, Maslanka SE. 2012. Analysis of a unique Clostridium botulinum strain from the Southern hemisphere producing a novel type E botulinum neurotoxin subtype. BMC Microbiol. 12:245. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill KK, Xie G, Foley BT, Smith TJ, Munk AC, Bruce D, Smith LA, Brettin TS, Detter JC. 2009. Recombination and insertion events involving the botulinum neurotoxin complex genes in Clostridium botulinum types A, B, E and F and Clostridium butyricum type E strains. BMC Biol. 7:66. 10.1186/1741-7007-7-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skarin H, Hafstrom T, Westerberg J, Segerman B. 2011. Clostridium botulinum group III: a group with dual identity shaped by plasmids, phages and mobile elements. BMC Genomics 12:185. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skarin H, Segerman B. 2011. Horizontal gene transfer of toxin genes in Clostridium botulinum: involvement of mobile elements and plasmids. Mob. Genet. Elements 1:213–215. 10.4161/mge.1.3.17617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leclair D, Fung J, Isaac-Renton JL, Proulx J, May-Hadford J, Ellis A, Ashton E, Bekal S, Farber JM, Blanchfield B, Austin JW. 2013. Foodborne botulism in Canada, 1985–2005. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19:961–968. 10.3201/eid1906.120873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin JW, Sanders G. 2009. Detection of Clostridium botulinum and its toxins in suspect foods and clinical specimens. HPB method MFHPB-16. Health Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/res-rech/analy-meth/microbio/volume2-eng.php . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. 2013. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief. Bioinform. 14:178–192. 10.1093/bib/bbs017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milne I, Bayer M, Cardle L, Shaw P, Stephen G, Wright F, Marshall D. 2010. Tablet-next generation sequence assembly visualization. Bioinformatics 26:401–402. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W. 2012. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28:3150–3152. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu K, Linder CR, Warnow T. 2011. RAxML and FastTree: comparing two methods for large-scale maximum likelihood phylogeny estimation. PLoS One 6:e27731. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Austin JW, Leclair D. 2011. Botulism in the North: a disease without borders. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:593–594. 10.1093/cid/ciq256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leclair D, Farber JM, Doidge B, Blanchfield B, Suppa S, Pagotto F, Austin JW. 2013. Distribution of Clostridium botulinum type E strains in Nunavik, Northern Quebec, Canada. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:646–654. 10.1128/AEM.05999-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang D, Baudys J, Rees J, Marshall KM, Kalb SR, Parks BA, Nowaczyk L, II, Pirkle JL, Barr JR. 2012. Subtyping botulinum neurotoxins by sequential multiple endoproteases in-gel digestion coupled with mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 84:4652–4658. 10.1021/ac3006439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stringer SC, Carter AT, Webb MD, Wachnicka E, Crossman LC, Sebaihia M, Peck MW. 2013. Genomic and physiological variability within group II (non-proteolytic) Clostridium botulinum. BMC Genomics 14:333. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dolman CE, Chang H. 1953. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of type E and fishborne botulism. Can. J. Public Health 44:231–244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dolman CE, Murakami L. 1961. Clostridium botulinum type F with recent observations on other types. J. Infect. Dis. 109:107–128. 10.1093/infdis/109.2.107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hielm S, Hyytia E, Andersin AB, Korkeala H. 1998. A high prevalence of Clostridium botulinum type E in Finnish freshwater and Baltic Sea sediment samples. J. Appl. Microbiol. 84:133–137. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsukamoto K, Mukamoto M, Kohda T, Ihara H, Wang X, Maegawa T, Nakamura S, Karasawa T, Kozaki S. 2002. Characterization of Clostridium butyricum neurotoxin associated with food-borne botulism. Microb. Pathog. 33:177–184. 10.1006/mpat.2002.0525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leclair D. 2008. Molecular epidemiology and risk assessment of human botulism in the Canadian Arctic. Ph.D. thesis University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hielm S, Bjorkroth J, Hyytia E, Korkeala H. 1998. Genomic analysis of Clostridium botulinum group II by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:703–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dolman CE, Chang H, Kerr DE, Shearer AR. 1950. Fish-borne and type E botulism: two cases due to home-pickled herring. Can. J. Public Health 41:215–229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paul CJ, Twine SM, Tam KJ, Mullen JA, Kelly JF, Austin JW, Logan SM. 2007. Flagellin diversity in Clostridium botulinum groups I and II: a new strategy for strain identification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:2963–2975. 10.1128/AEM.02623-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leclair D, Pagotto F, Farber JM, Cadieux B, Austin JW. 2006. Comparison of DNA fingerprinting methods for use in investigation of type E botulism outbreaks in the Canadian Arctic. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1635–1644. 10.1128/JCM.44.5.1635-1644.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gunnison JB, Cummings JR, Meyer KF. 1936. Clostridium botulinum type E. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 35:278–280. 10.3181/00379727-35-8938P [DOI] [Google Scholar]