ABSTRACT

Viral infectivity factor (Vif) is required for lentivirus fitness and pathogenicity, except in equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV). Vif enhances viral infectivity by a Cullin5-Elongin B/C E3 complex to inactivate the host restriction factor APOBEC3. Core-binding factor subunit beta (CBF-β) is a cell factor that was recently shown to be important for the primate lentiviral Vif function. Non-primate lentiviral Vif also degrades APOBEC3 through the proteasome pathway. However, it is unclear whether CBF-β is required for the non-primate lentiviral Vif function. In this study, we demonstrated that the Vifs of non-primate lentiviruses, including feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), bovine immunodeficiency virus (BIV), caprine arthritis encephalitis virus (CAEV), and maedi-visna virus (MVV), do not interact with CBF-β. In addition, CBF-β did not promote the stability of FIV, BIV, CAEV, and MVV Vifs. Furthermore, CBF-β silencing or overexpression did not affect non-primate lentiviral Vif-mediated APOBEC3 degradation. Our results suggest that non-primate lentiviral Vif induces APOBEC3 degradation through a different mechanism than primate lentiviral Vif.

IMPORTANCE The APOBEC3 protein family members are host restriction factors that block retrovirus replication. Vif, an accessory protein of lentivirus, degrades APOBEC3 to rescue viral infectivity by forming Cullin5-Elongin B/C-based E3 complex. CBF-β was proved to be a novel regulator of primate lentiviral Vif function. In this study, we found that CBF-β knockdown or overexpression did not affect FIV Vif's function, which induced polyubiquitination and degradation of APOBEC3 by recruiting the E3 complex in a manner similar to that of HIV-1 Vif. We also showed that other non-primate lentiviral Vifs did not require CBF-β to degrade APOBEC3. CBF-β did not interact with non-primate lentiviral Vifs or promote their stability. These results suggest that a different mechanism exists for the Vif-APOBEC interaction and that non-primates are not suitable animal models for exploring pharmacological interventions that disrupt Vif–CBF-β interaction.

INTRODUCTION

The APOBEC3 family comprises several cytidine deaminases encoded by human cells that block retrovirus replication, including human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (1–11). HIV-1 viral infectivity factor (Vif) is essential for viral infectivity because it recruits the host restriction factor APOBEC3G (A3G) to the E3 ligase complex, which consists of the scaffold protein Cullin5 (CUL5) and substrate adaptors Elongin B/C and Rbx, to induce A3G polyubiquitination and degradation, thereby suppressing A3G-mediated antiviral activity (6, 12–28). Recent studies have shown that the transcription cofactor core-binding factor subunit beta (CBF-β) is a key factor in Vif function (29, 30). CBF-β interacts with HIV-1 Vif to enhance Vif's biosynthesis and facilitate Vif folding and stability, thereby enhancing the nucleation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, promoting A3G degradation, and supporting viral infectivity (31–38).

Human CBF-β is present in two isoforms because of alternative splicing (33, 39, 40), and they differ at their C termini and share the same 165 amino acids at their N termini. CBF-β is recognized as a non-DNA binding subunit of the core binding factor family of transcription factors (41, 42). CBF-β forms heterodimers with RUNX proteins (RUNX1, RUNX2, and RUNX3), which makes RUNX proteins more stable and enhances the affinity of RUNX to the core binding sites of various promoters and enhancers (43, 44). This is thought to occur through changes in the conformation of RUNX and the removal of the autoinhibition of RUNX protein. CBF-β–RUNX interaction can activate or repress the transcription of various genes that are important for hematopoiesis and osteogenesis, thereby affecting the regulation of cell differentiation or proliferation (45, 46).

Both CBF-β isoforms can stabilize HIV-1 Vif to degrade A3G and rescue viral infectivity (33). Vif alleles of HIV-1 subtypes A, B, C, D, AE, F, and G are all sensitive to CBF-β (33). CBF-β increases the steady-state level of all HIV-1 Vifs and promotes increased A3G degradation, indicating the conserved features of the dependency of HIV-1 Vifs. In addition to A3G degradation, degradations of other human APOBEC3 family members (including A3C, A3D, A3F, and A3H) induced by HIV-1 Vif also require CBF-β. Similarly, SIVmac Vif requires CBF-β to induce rhesus macaque APOBEC3 protein degradation and increase SIVmac infectivity (33).

The Vifs of non-primate lentiviruses, such as feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), bovine immunodeficiency virus (BIV), and maedi-visna virus (MVV), also mediate APOBEC3 downregulation (47, 48), but their precise mechanisms are incompletely understood. FIV Vif interacts with CUL5 and Elongin B/C to form an E3 complex that degrades feline APOBEC3 through a proteasome-dependent pathway (49). This is very similar to the action of HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) Vif. The specific FIV Vif-E3 (especially CUL5) complex interactions are still unclear. It remains to be elucidated whether all lentiviral Vifs, including caprine arthritis encephalitis virus (CAEV) Vif, could induce APOBEC3 degradation, and moreover, whether CBF-β is necessary for the function of FIV and other non-primate lentivirus (BIV/CAEV/MVV) Vifs to neutralize APOBEC3.

In this study, we cloned the CBF-β gene from a Chinese domestic cat. The amino acid sequences of cat CBF-β and human CBF-β were identical. The depleting of endogenous CBF-β expression and CBF-β overexpression did not affect the action of non-primate lentiviral Vif-mediated APOBEC3 degradation. CBF-β does not interact with FIV/BIV/CAEV/MVV Vifs and does not increase their steady-state levels. Furthermore, CBF-β altered the multimerization of HIV-1 Vif but not FIV Vif when overexpressed. In summary, we found that CBF-β is important for primate lentiviral Vif function, but CBF-β is not necessary for non-primate lentiviral Vif function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Proteasome inhibitor MG132, cycloheximide (CHX), and puromycin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. TRIzol was purchased from Invitrogen.

Antibodies and cell lines.

HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO) and 100 U of penicillin-streptomycin (GIBCO) and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cells were passaged every 2 days when confluent. The antibodies used in this study were rabbit antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) polyclonal antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), anti-CBF-β antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), anti-myc antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany), anti-Flag antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, Israel, Australia), mouse anti-HA antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), anti-V5 antibody (Invitrogen), anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), Alexa Fluor 800-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG or Alexa Fluor 700-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD), and anti-Flag M2 beads (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Plasmids.

The total RNA was extracted from cat blood using TRIzol reagent and subjected to reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). The CBF-β gene was cloned into a modified VR-1012 vector (VR-linker) with a tandem myc-Flag tag at the C terminus, named VR-CBF-mf. The oligonucleotide primers were as follows: forward, Cat-CBF-β-BamHI-F (5′-ATGGGATCCATGCCGCGCGTCGTGCCTGACCAGAGAAGCAAGTTC-3′), and reverse, Cat-CBF-β-NotI-R (5′-TAAAGCGGCCGCGTAGGGTCTTGTTGTCTTCTTGCCAGTTAC-3′). Cat-A3Z2-Z3 was cloned into pCDNA3.1 (+) with double HA tags in its C terminus using the following primers: forward, cat-A3Z2-Z3-BamHI-F (5′-ATGGGATCCATGGAGCCCTGGCGCCCCAGCCCAAGAAAC-3′), and reverse, cat-A3Z2-Z3-NotI-R (5′-TAAAGCGGCCGCTGATTCAAGTTTCAAATTTCTGAAGTCATTCC-3′). HIV-1 vif (GenBank accession number [GB] AF324493), SIVmac vif (GB AY588946), FIV vif (NC001482), BIV vif (GB M32690), CAEV vif (NC001463), MVV vif (GB M60610), cow A3Z3 (GB EU864536), and sheep A3Z3 (GB EU864543) cDNAs were codon optimized and synthesized by Shanghai Generay Biotech Co. and then cloned into pCDNA3.1 (+) with double HA tags in the C terminus. Human A3G (A3G) (GB NM_021822), chimpanzee A3G (A3Gcpz) (GB AY639868), and macaque A3G (A3Gmac) (GB JX915798) have been previously described (26, 27).

CBF-β-KD 293T cell generation.

The miR-30 expression cassette sequences from pSM2 were cloned into the pMD18-T Simple vector. Next, we replaced the two cloning sites XhoI and EcoRI with MluI and BamHI, respectively, to clone the stem-loop coding region. The primers used for stem-loop cloning were as follows: forward, MluI-5′miR30-F (5′-TCGACACGCGTAAGGTATATTGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCG-3′), and reverse, BamHI-3′miR30-R (5′-AATTGGGATCCTCCGAGGCAGTAGGCA-3′). Then, the miR-30 precursor cassette was cloned into pLPCX using the following primers: forward, XhoI-miR30-F (5′-GGCAGCACCTCGAGGTCGACTAGGGATA-3′), and reverse, NotI-miR30-R (5′-CAATGCGGCCGCAAGTGATTTAATTTATAC-3′). The cassette was then subjected to XhoI/NotI digestion, thereby generating pLPCX-shRNA. Finally, the CBF-β-specific sequence (5′-GCCGAGAGTATGTCGACTTAG-3′) and a control sequence (5′-CCGCCTGAAGTCTCTGATTAA-3′) were inserted into pLPCX-shRNA to yield pLPCX-sh-cbf and pLPCX-sh-con, respectively. Then, 293T cells were transduced with pLPCX-sh-cbf or pLPCX-sh-con and selected using 1 μg/ml of puromycin. The expression of CBF-β in the stable depleted 293T cell line was checked by Western blotting.

Transfection and Western blotting.

The transfections accomplished in 293T cells used the standard calcium phosphate method as previously described (50, 51). The cells were harvested 2 days after transfection. The lysis buffer contained 150 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM Na2EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100. The samples were separated on a 12% gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore). The membrane was blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing 5% dry milk for 2 h at room temperature, probed with primary antibodies for 2 h, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 800-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG or Alexa Fluor 700-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Finally, the protein expression levels were determined and quantified using an Odyssey system (LI-COR).

Coimmunoprecipitation assay.

293T cells were transfected with VR-CBF-mf and different lentiviral Vif constructs. Control vectors were added when needed. Cells were collected 48 h after transfection and lysed in lysis buffer containing 150 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM Na2EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Promega) for 10 min. The supernatant was clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Aliquots of cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting and the immunoprecipitation assay. For the immunoprecipitation assay, cell lysates were incubated with 50 μl of anti-Flag M2 beads at 4°C for 4 h. The beads were then washed five times with the lysis buffer at 4°C, and the bound protein was verified by Western blotting. Vifs were checked by rabbit anti-HA antibody, and CBF-β was detected by anti-Flag antibody.

Sucrose gradient centrifugation.

HIV-1 Vif or FIV Vif expression vector was transfected with VR-CBF-mf or control vectors into 293T cells in 10-cm dishes. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, the cells were harvested and lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer containing 150 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM Na2EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Promega). The clarified cell lysates were laid on 10% to 50% sucrose cushions and centrifuged at 163,000 × g for 45 min at 4°C in an SW55 rotor. Sample fractions were collected from the top to the bottom and analyzed by Western blotting. Vifs and CBF-β were detected by anti-HA antibody or anti-Flag antibody, respectively. The cells transfected with A3G construct were lysed and treated or not with RNase A (Promega) for 30 min at 4°C. The cell lysate was then centrifuged and analyzed as described above. A3G was checked by anti-V5 antibody.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The CBF-β gene sequence was submitted to GenBank under accession number KM250107.

RESULTS

CBF-β is not required for FIV Vif-mediated cat A3Z2-Z3 degradation.

CBF-β plays an important role in primate lentiviral Vif-CUL5-Elongin B/C mediated APOBEC3 degradation. FIV Vif, similar to HIV/SIV Vifs, has been shown to induce cat APOBEC3 degradation in human 293T cells through recruitment of the CUL5-Elongin B/C-based E3 ligase complex (49, 52). To test if feline CBF-β interacts with FIV Vif, we first cloned the CBF-β gene from a Chinese domestic cat. We found that the amino acid sequence of cat CBF-β was 100% identical to that of human CBF-β. Thus, to assess the requirement of CBF-β for FIV Vif function, we first attempted to silence the CBF-β gene in 293T cells and determine whether FIV Vif-mediated APOBEC3 degradation could be interrupted. A miR-30-derived microRNA (miRNA) expression cassette based on the pLPCX vector was constructed to express CBF-β-specific miRNA (pLPCX-sh-cbf) and a control miRNA (pLPCX-sh-con) (Fig. 1A). After transducing the vectors into 293T cells, we obtained a stable CBF-β knockdown (CBF-β-KD) cell line in which CBF-β expression was reduced by approximately 60% compared with that in the control cell line, as detected by Western blotting (Fig. 1B). We next determined the effects of CBF-β-KD on HIV-1 or FIV Vif-mediated APOBEC3 degradation in these cells. We found that HIV-1 Vif induced A3G degradation through the proteasome pathway, as observed in the control cells (Fig. 1C, lanes 4 to 6). In addition, we detected a reduction in A3G degradation in the CBF-β-KD cell line (Fig. 1C, compare lane 2 with lane 5). Moreover, CBF-β-KD also reduced HIV-1 Vif expression (Fig. 1C). In contrast, although FIV Vif induced cat A3Z2-Z3 degradation through the proteasome pathway (Fig. 1D, lanes 4, 5, and 6), CBF-β-KD did not affect the steady-state level of FIV Vif, and cat A3Z2-Z3 was effectively downregulated in the CBF-β-KD cell line as in the control cells despite repeated attempts (Fig. 1D, compare lane 2 with lane 5). Therefore, we noticed that in contrast to the case with HIV-1/SIV Vif, CBF-β-KD did not affect FIV Vif-mediated cat A3Z2-Z3 degradation.

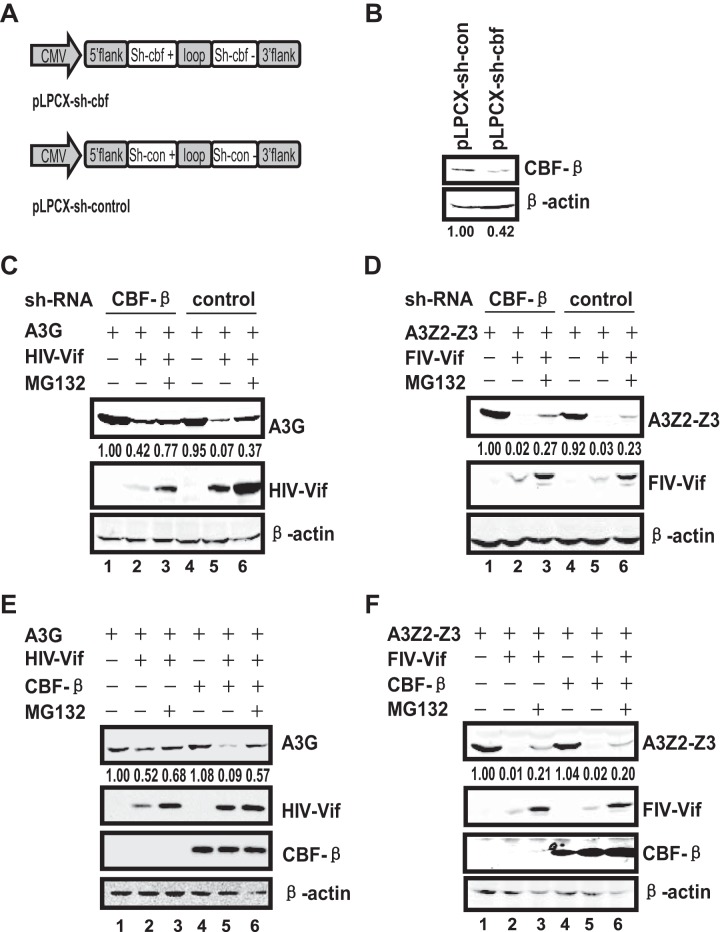

FIG 1.

CBF-β is critical for HIV Vif but not FIV Vif function. (A) Construction of CBF-β-KD 293T cell lines using a stably integrated small hairpin RNA (shRNA) based on the human microRNA miR-30a expression cassette. The shRNA of CBF-β targets both isoforms of human CBF-β mRNA. (B) 293T cells were transfected with the indicated shRNA expression vectors, followed by selection with puromycin. The expression of CBF-β in CBF-β-KD and control cells was analyzed by Western blotting using polyclonal antibodies against CBF-β. (C) The silencing of endogenous CBF-β expression in 293T cells impairs HIV Vif-mediated degradation of A3G. A3G (3 μg) was cotransfected with 3 μg of HIV-1 Vif expression vectors or control vector into stable CBF-β-KD 293T cells or control cells. MG132 (7.5 μM) was added 24 h after transfection. Cell lysates were prepared 48 h after transfection and analyzed by Western blotting. Anti-V5 antibody was used for detection of A3G, anti-HA antibody for HIV-1 Vif, and anti-actin for β-actin. β-Actin was used as the internal control. (D) The knockdown of endogenous CBF-β expression in 293T cells does not affect FIV Vif-mediated downregulation of cat A3Z2-Z3. Stable CBF-β-KD 293T cells or control cells were transfected with 3 μg of A3Z2-Z3 and 3 μg of FIV Vif expression vectors or control vector. MG132 (7.5 μM) was added 24 h after transfection. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody against cat A3Z2-Z3 and FIV Vif. (E) CBF-β overexpression in CBF-β-KD cells restored HIV-1 Vif function. A3G (3 μg) was cotransfected with 2.7 μg of HIV-1 Vif expression vector or control vector in the presence or absence of 0.3 μg of VR-CBF-mf into stable CBF-β-KD 293T cells. After 1 day, MG132 was added to the cells. Anti-Flag antibody was used to detect CBF-β ectopic expression. (F) CBF-β overexpression in CBF-β-KD cells did not affect FIV Vif function. Stable CBF-β-KD 293T cells were transfected with 3 μg of A3Z2-Z3 and 2.7 μg of FIV Vif expression vectors in the presence or absence of 0.3 μg of VR-CBF-mf. MG132 (7.5 μM) was added to cells 24 h after transfection. The numbers indicate the ratio of the gray value of CBF-β (B) and APOBEC3 (C, D, E, and F) to β-actin. The data represent the results of one of three replicate experiments.

To further confirm the lack of effect of CBF-β on FIV Vif-mediated cat A3Z2-Z3 degradation, we overexpressed CBF-β in CBF-β-KD cells to assess HIV-1 and FIV Vif functions. As shown in Fig. 1C, A3G was moderately downregulated in CBF-β-KD cells, and it was further depleted when CBF-β was overexpressed with HIV-1 Vif (Fig. 1E, lanes 2 and 5), even in the presence of MG132 (Fig. 1E, lanes 3 and 6). Moreover, the increased A3G degradation did not depend on CBF-β overexpression (Fig. 1E, lanes 1 and lane 4). In contrast, the steady-state level of FIV Vif remained constant irrespective of CBF-β knockdown or overexpression. Furthermore, FIV Vif-mediated cat A3Z2-Z3 degradation was unaffected by CBF-β knockdown and overexpression (Fig. 1F). Cat A3Z2-Z3 could only be weakly detected upon FIV Vif expression irrespective of CBF-β depletion. Thus, we concluded that CBF-β is required for HIV-1 Vif function but is not essential for FIV Vif-mediated cat A3Z2-Z3 degradation.

CBF-β did not promote FIV Vif cellular stability.

A previous study proposed that CBF-β promotes steady-state levels of HIV-1 Vif through the effect on HIV-1 Vif metabolism and biosynthesis (38). As mentioned above, we noticed that the steady-state level of HIV-1 Vif was sensitive to CBF-β depletion (Fig. 1C) or overexpression (Fig. 1E) but that of FIV Vif was not affected by CBF-β (Fig. 1D and F). Because the results were obtained when APOBEC3 was coexpressed, we could not exclude the possible influence of APOBEC3 on the steady-state level of Vifs. Therefore, to precisely determine the effect of CBF-β on the cellular steady-state level of Vifs, we transfected CBF-β vectors in 293T cells at increasing doses of HIV-1 Vif or FIV Vif constructs and monitored the expression of Vifs. HIV-1 Vif was barely detected in low doses when transfected alone (Fig. 2A), and CBF-β coexpression obviously improved its levels at all doses (Fig. 2A). Because CBF-β was inherently expressed in 293T cells, our results implied that endogenous CBF-β was not sufficient to guarantee the overexpressed HIV-1 Vif function. However, when FIV Vif and CBF-β were coexpressed, we found that the signal of FIV Vif improved at increasing doses of plasmids but was not affected by CBF-β overexpression (Fig. 2B).

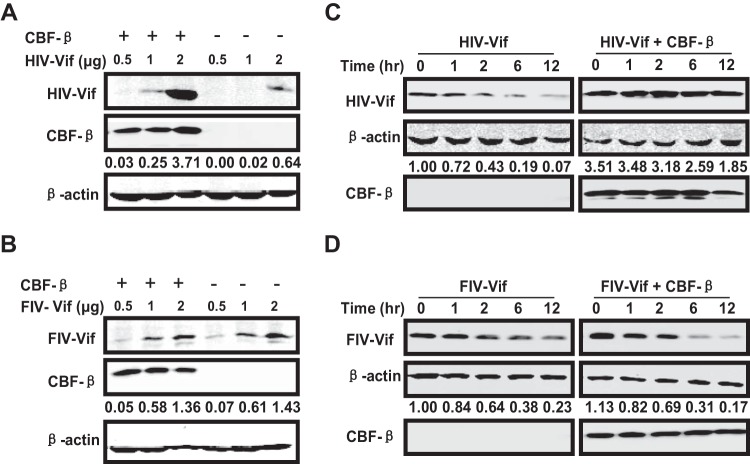

FIG 2.

CBF-β promoted HIV-1 Vif but not FIV Vif stability. (A and B) The indicated doses of HIV-1 (A) or FIV (B) Vif constructs were cotransfected with 0.3 μg of VR-CBF-mf or control vector in 293T cells. Cell lysates were collected 36 h after transfection. Vifs were detected using anti-HA antibody, and CBF-β was detected using anti-Flag antibody. (C and D) HIV-1 Vif (3 μg) (C) or FIV Vif (3 μg) (D) was cotransfected with 0.3 μg of VR-CBF-mf or control vector into 293T cells. After 24 h posttransfection, cells were treated with CHX (100 μg/ml) at the indicated time points. The samples were analyzed with the indicated antibodies. The numbers indicate the ratios of the gray value of Vifs to β-actin.

To exclude the possible effects of artificial transfection and confirm the promotion of stability of HIV-1 Vif but not FIV Vif by CBF-β, we performed a cycloheximide (CHX) stability assay with 293T cells in the presence or absence of CBF-β overexpression. CHX could inhibit protein synthesis but had no effect on protein degradation. After CHX treatment, the levels of HIV-1 Vif decreased by more than 50% within 2 h, and they remained less than 10% after 12 h, indicating that HIV-1 Vif decayed fast when expressed alone in 293T cells (Fig. 2C). In contrast, CBF-β overexpression significantly enhanced the levels of HIV-1 Vif (Fig. 2C). The cellular half-life of HIV-1 Vif was less than 2 h when Vif was expressed alone, but it increased to about 12 h when CBF-β was overexpressed. However, in the case of FIV Vif, we obtained different results. The stability of FIV Vif was constant irrespective of CBF-β overexpression (Fig. 2D). Moreover, the half-life of FIV Vif in 293T cells was longer than that of HIV-1 Vif. Collectively, our results suggested that CBF-β promoted HIV-1 Vif stability but not FIV Vif stability, which corresponded to HIV-1 Vif but not FIV Vif being required for APOBEC3 degradation.

CBF-β impaired the oligomerization of HIV-1 Vif but not FIV Vif.

HIV-1 Vif was proposed to form multimers, which are necessary for the binding of Vif to viral RNA and packaging into virions. Disturbing HIV-1 Vif multimerization limited its function in the cells (53–55). Because CBF-β interacts with HIV-1 Vif to form a CUL5-based E3 ligase complex to induce APOBEC3 degradation (56), we questioned how HIV-1 Vif exerted its function in the multimeric form. Therefore, we speculated that CBF-β bound to HIV-1 Vif, decreasing Vif oligomerization and regulating Vif folding for the formation of a stable hexamer complex.

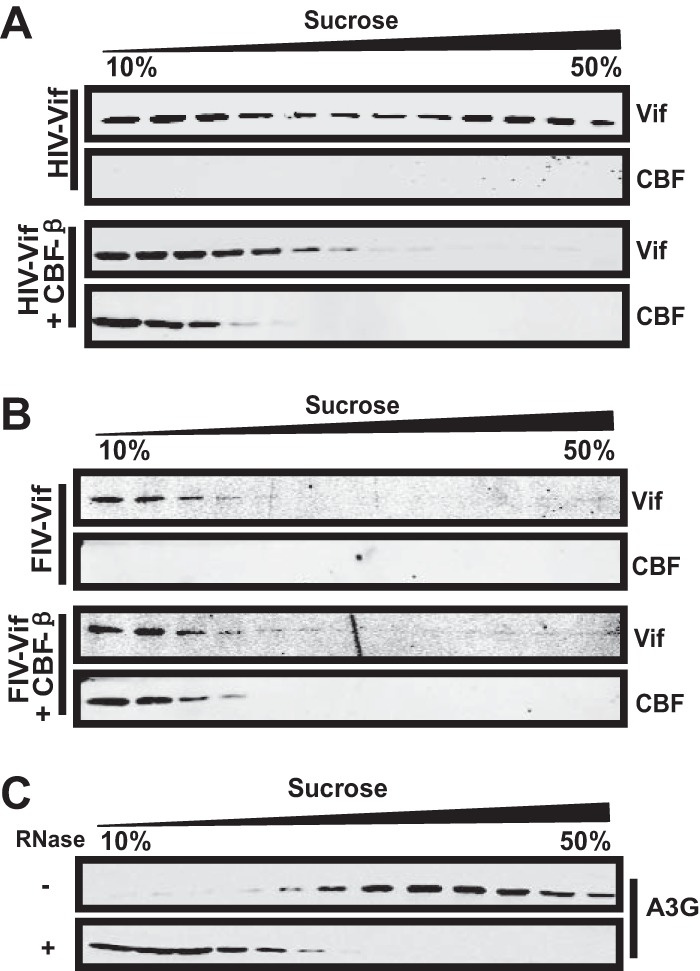

To verify our hypothesis, HIV-1 vif or FIV vif constructs in the presence of a control vector or a CBF-β-expressing construct were transfected in 293T cells and analyzed by sucrose gradient centrifugation to investigate their oligomerization status. HIV-1 Vif was detected in both the high-density and low-density sucrose cushions, indicating that HIV-1 Vif existed both in the multimeric form and as a low-molecular mass protein (Fig. 3A). In contrast, FIV Vif was mainly detected in the low-density sucrose fraction and at low levels in the high-density sucrose fraction (Fig. 3B). CBF-β decreased the level of the high-molecular-mass complex of HIV-1 Vif and increased the portion of the low-molecular-mass protein when cotransfected (Fig. 3A). However, the concentration of the complex of FIV Vif was not affected by CBF-β overexpression (Fig. 3B). As a control, human A3G, which forms an RNase-sensitive high-molecular-mass complex in the cells (57), was transiently overexpressed in 293T cells. The level of oligomerization of A3G treated or not with RNase A was assessed. We indeed confirmed the oligomerization of A3G and found that RNase treatment disturbed the formation of the oligomers of A3G under the same experimental conditions (Fig. 3C). Therefore, we concluded that CBF-β coexpression disturbed the oligomerization status of HIV-1 Vif but not that of FIV Vif.

FIG 3.

CBF-β altered the oligomerization status of HIV-1 Vif but not FIV Vif. (A and B) CBF-β decreased the oligomerization of HIV-1 Vif but not FIV Vif. The HIV-1 Vif (A) or FIV Vif (B) construct (18 μg) was transfected with 2 μg of VR-CBF-mf or control vector into 293T cells. After 2 days, the cell lysate was subjected to sucrose gradient centrifugation and proteins were detected by Western blotting. HIV-1 Vif was detected using anti-HA antibody and CBF-β using anti-Myc antibody. (C) 293T cells were transfected with 15 μg of A3G vector for 48 h. The cell lysates were either treated with RNase A (10 μg/ml) for 30 min or left untreated before being subjected to sucrose gradient centrifugation. A3G was detected using anti-V5 antibody.

CBF-β is required for the function of primate lentiviral Vif but not for that of non-primate lentiviral Vif.

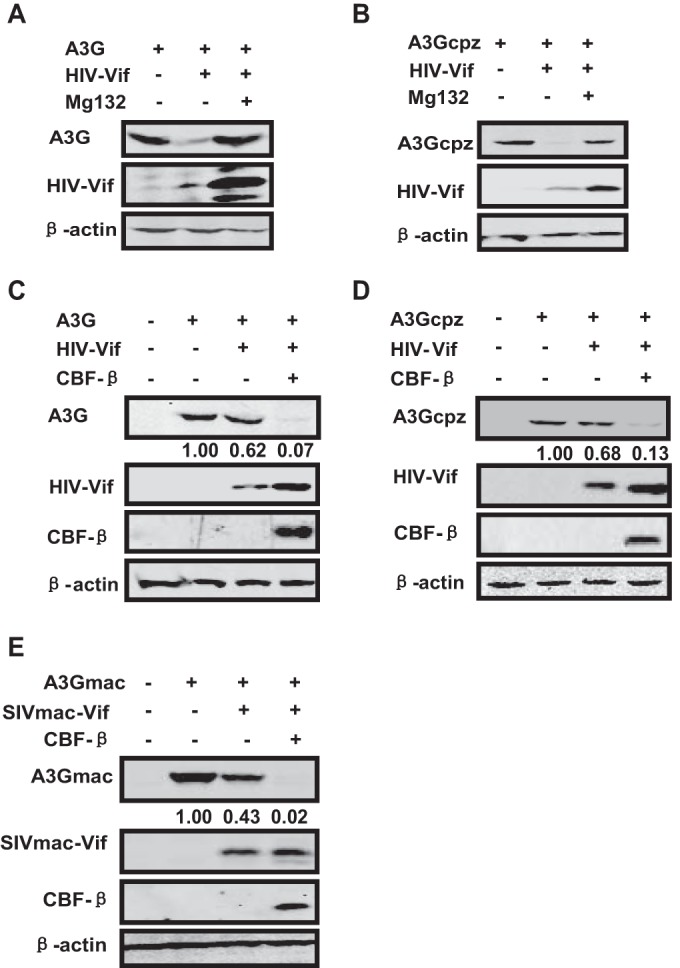

CBF-β is required for HIV-1 and SIVmac Vif functions to induce human and macaque Vif-sensitive APOBEC3 degradation, respectively. Chimpanzee A3G (A3Gcpz) is also sensitive to HIV-1 Vif. To determine whether HIV-1 Vif-mediated APOBEC3 depletion in other species also requires CBF-β assistance, we assessed the effects of CBF-β on A3Gcpz degradation in the presence of HIV-1 Vif. HIV-1 Vif degraded A3Gcpz through the proteasome pathway in a manner similar to that of A3G degradation (Fig. 4A and B). Similarly, CBF-β overexpression in CBF-β-silenced cells promoted HIV-1 Vif-mediated A3Gcpz degradation (Fig. 4D) in a manner similar to that of HIV-1 Vif-mediated A3G degradation (Fig. 4C). Moreover, CBF-β promoted SIVmac Vif-mediated A3Gmac degradation as described previously (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, as others proposed (29), the influence of CBF-β on the stability of SIVmac Vif was not as obvious as that of HIV-1 Vif (Fig. 4E), indicating that CBF-β enhances the ability of SIVmac Vif as for HIV-1 Vif (38). Thus, CBF-β is necessary for primate lentiviral Vif function.

FIG 4.

Primate lentiviral Vif-mediated degradation of A3G requires CBF-β. (A and B) HIV-1 Vif induces the degradation of human A3G (A3G) or chimpanzee A3G (A3Gcpz) in a proteasome-dependent manner. A3G or A3Gcpz (3 μg) was transfected with 3 μg of HIV-1 Vif construct or control plasmid in 293T cells. MG132 was added 24 h after transfection, and cells were collected for Western blot analysis 48 h after transfection. (C to E) CBF-β overexpression enhances HIV-1/SIV Vif-mediated APOBEC3 degradation in CBF-β-KD cells. APOBEC3 (3 μg) was cotransfected into stable CBF-β-KD 293T cells with 2.7 μg of Vif expression vectors or control vector in the presence or absence of 0.3 μg of VR-CBF-mf. APOBEC3 and Vifs were detected using anti-V5 antibody and anti-HA antibody, respectively. CBF-β was detected using anti-Flag antibody. The numbers indicated the ratios of the gray value of APOBEC3 to β-actin.

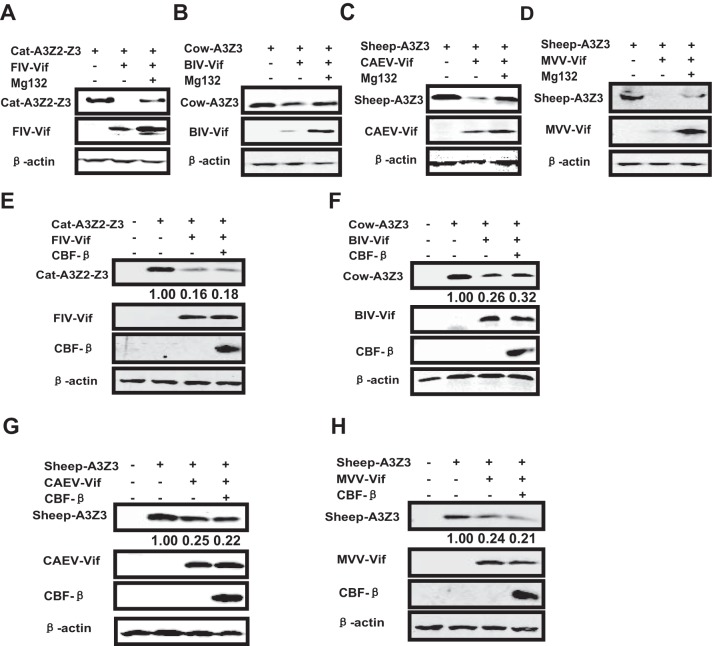

Non-primate lentiviruses include FIV, BIV, CAEV, MVV, and equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV). Among these, FIV, BIV, CAEV, and MVV express the vif gene. A previous study showed that FIV, BIV, and MVV Vifs induce feline, cow, and sheep APOBEC3 degradation, respectively (48). However, there are no reports about the degradation of APOBEC3 induced by CAEV Vif. To comprehensively analyze the requirement of CBF-β for non-primate lentiviral Vif function, we synthesized all the non-primate lentiviral vif genes and performed Vif-mediated APOBEC3 depletion experiments with CBF-β-silenced cells in the presence or absence of CBF-β. First, we found that CAEV Vif could also induce sheep A3Z3 degradation through the proteasome pathway, which was also the case for the FIV, BIV, and MVV Vif functions (Fig. 5A to D). CBF-β overexpression did not promote non-primate lentivirus-mediated APOBEC3 degradation (Fig. 5E to H). This result is in agreement with a previous report showing that BIV Vif-mediated bovine APOBEC3 degradation was unaffected by CBF-β silencing (30). Thus, our results demonstrate that CBF-β is required for primate lentiviral Vif function but not for non-primate lentiviral Vif function.

FIG 5.

Non-primate lentiviral Vif-mediated degradation of A3G does not require CBF-β. (A to D) FIV/BIV/CAEV/MVV Vif induce the degradation of cat A3Z2-Z3/cow A3Z3/sheep A3Z3 in a proteasome-dependent manner. Different APOBEC3 constructs (3 μg) were cotransfected with 3 μg of Vif constructs or control vector into 293T cells. MG132 (7.5 μM) was added 24 h after transfection, and cells were collected 2 days later to perform Western blotting. Non-primate APOBEC3 and non-primate lentiviral Vifs were detected using anti-HA antibody. (E to H) CBF-β overexpression does not enhance non-primate lentiviral Vif-mediated APOBEC3 degradation in CBF-β-KD cells. Different non-primate APOBEC3 vectors (3 μg) were cotransfected with 2.7 μg of the indicated Vif expression vectors in the presence or absence of 0.3 μg of VR-CBF-mf in stable CBF-β-KD 293T cells. APOBEC3 and Vifs were detected using anti-HA antibody. CBF-β was detected using anti-Flag antibody. The numbers indicated the ratios of the gray value of APOBEC3 to β-actin.

CBF-β did not interact with non-primate lentiviral Vifs and had no effect on their cellular stability.

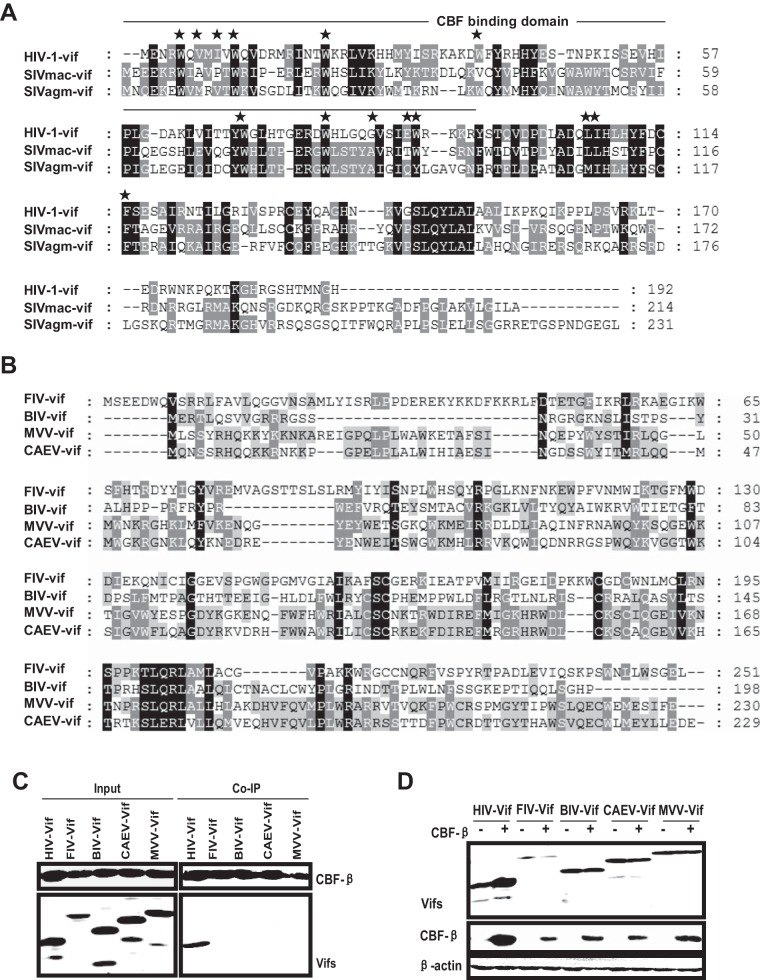

The CBF-β–HIV-1 Vif interaction is necessary for the molecular chaperone role of CBF-β in facilitating the HIV-1 Vif function, and a binding-failure mutant (CBF-β F68D) lacked the capacity to support the Vif function (31, 58). The N terminus of HIV-1 Vif, particularly the amino acids W5, V7, I9, W11, W21, W38, G84, E88, W89, L106, and I107 (Fig. 6A), was critical for CBF-β binding (30, 56, 58–61). These amino acids were almost conserved among primate lentiviral Vifs (Fig. 6A). However, the amino acids important for CBF-β binding were not found in the corresponding sites of the non-primate lentiviral Vifs (Fig. 6B). Because CBF-β was dispensable for non-primate lentivirus-mediated APOBEC3 degradation, we suspected that there was no interaction between CBF-β and non-primate lentiviral Vifs. Thus, we examined CBF-β–non-primate lentiviral Vif interactions by cotransfecting Flag-tagged CBF-β and HA-tagged Vifs in 293T cells and subjecting the cells to anti-Flag coimmunoprecipitation. As previously described, HIV-1 Vif precipitated with CBF-β (Fig. 6C, lane 6). However, there was no high affinity between CBF-β and non-primate lentiviral Vifs (Fig. 6C, lanes 7, 8, 9, and 10).

FIG 6.

Non-primate lentiviral Vifs do not interact with CBF-β. (A) Amino acid alignment of primate lentiviral Vifs using Clustal W. Identical amino acids are highlighted in black. The N terminus of HIV-1 Vif is critical for CBF-β binding. Stars indicate the hydrophobic amino acids required for CBF-β interaction. (B) Amino acid alignment of non-primate lentiviral Vifs. (C) HIV-1 or non-primate lentiviral Vif (3 μg) was cotransfected with 0.5 μg of VR-CBF-mf in 293T cells. A portion of the cell lysate was collected to analyze the expression of proteins, and the remaining cell lysate was mixed with anti-Flag beads. Bound proteins were detected using rabbit anti-HA antibody. (D) CBF-β does not promote the stability of non-primate lentiviral Vifs in 293T cells. The indicated Vifs (3 μg) were transfected with 0.6 μg of CBF-β or control vector, and after 48 h, the cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting with antibodies against HA (Vifs) or Flag (CBF-β).

As discussed above, CBF-β was not essential for the FIV Vif function and did not enhance the cellular stability of FIV Vif (Fig. 2D). Therefore, we investigated the steady-state level of BIV/CAEV/MVV Vifs in the presence or absence of CBF-β overexpression. Compared with HIV-1 Vif, our results showed that the cellular stabilities of all non-primate lentiviral Vifs were invariable, irrespective of the presence or absence of CBF-β coexpression (Fig. 6D). We also observed that the steady-state level of CBF-β increased in the presence of HIV-1 Vif compared with that of non-primate lentiviral Vif (Fig. 6D), thereby indicating that HIV-1 Vif–CBF-β interaction may reinforce the stability of the complex. Overall, these results suggest that non-primate lentiviral Vifs do not require CBF-β to degrade APOBEC3.

DISCUSSION

The APOBEC3 family members are cytidine deaminases that block the replication of HIV-1 and other lentiviruses. With the exception of EIAV, most lentiviruses encode Vif proteins that bind APOBEC3 and facilitate proteasomal degradation. Recent studies have shown that CBF-β is necessary for HIV-1 Vif- or SIV Vif-mediated APOBEC3 degradation. However, the mechanism of APOBEC3 degradation by Vifs from non-primate lentiviruses, e.g., FIV, BIV, CAEV, and MVV, is not completely understood. In the present study, we analyzed the requirement of CBF-β in non-primate lentiviral Vif function. First, we found that ectopically expressed CBF-β promoted HIV-1 Vif- and SIV Vif-mediated A3G degradation in CBF-β-KD cells, as previously described (Fig. 4C and E). Second, we found that human and chimpanzee A3Gs were sensitive to HIV-1 Vif-mediated depletion in the presence of CBF-β (Fig. 4D). In contrast, non-primate lentiviral Vif-mediated APOBEC3 degradation did not require CBF-β in all cases (Fig. 5). Third, HIV-1 Vif interacted with CBF-β with a high affinity, whereas non-primate lentiviral Vifs did not (Fig. 6C). Next, CBF-β promoted the cellular stability of HIV-1 Vif, but CBF-β had no effect on the stability of non-primate lentiviral Vifs. We found that HIV-1 Vif exhibited obvious multimerization in cells and that CBF-β impaired Vif multimerization when coexpressed (Fig. 3A). In contrast, we found no obvious multimers of FIV Vif (Fig. 3B), and CBF-β coexpression did not affect the level of oligodimers of FIV Vif (Fig. 3B) or other non-primate lentiviral Vifs (data not shown).

Previous studies have shown that HIV-1 Vif forms oligomers or multimers in cells (53–55). The oligomerization of HIV-1 Vif into high-molecular-mass complexes is crucial for inducing Vif folding and binding onto HIV-1 genomic RNA, thereby enhancing HIV-1 Vif packaging into viral particles. A3G was found to be a regulator that strongly interferes with HIV-1 Vif multimerization to limit Vif function (55). It has also been proposed that CBF-β inhibits HIV-1 Vif oligomerization to promote the assembly of a well-ordered Vif-E3 complex (36). In the present study, we used sucrose gradient centrifugation to show that CBF-β perturbs HIV-1 Vif oligomerization in cells. Given the important roles of CBF-β in HIV-1 Vif function, we propose that oligomerization is involved in Vif binding to genomic RNA, while removing oligomerization might be important for HIV-1 Vif function in suppressing the antivirus activity of A3G.

Our experiments demonstrated that CBF-β was not required for non-primate lentiviral Vif-induced APOBEC3 degradation. Interestingly, during the preparation of the manuscript, we found that another group (54) showed that BIV Vif- and FIV Vif-induced APOBEC3 depletions were unaffected by CBF-β. Initially, we hypothesized that the CBF-β sequences were not conserved among species. However, we found that the amino acid sequences of both isoforms of cat CBF-β and human CBF-β were identical. Furthermore, recently published data demonstrated that CBF-β from diverse animal species can support HIV-1 Vif function (59), thereby indicating that HIV-1 Vif hijacks CBF-β for its function as an evolution result.

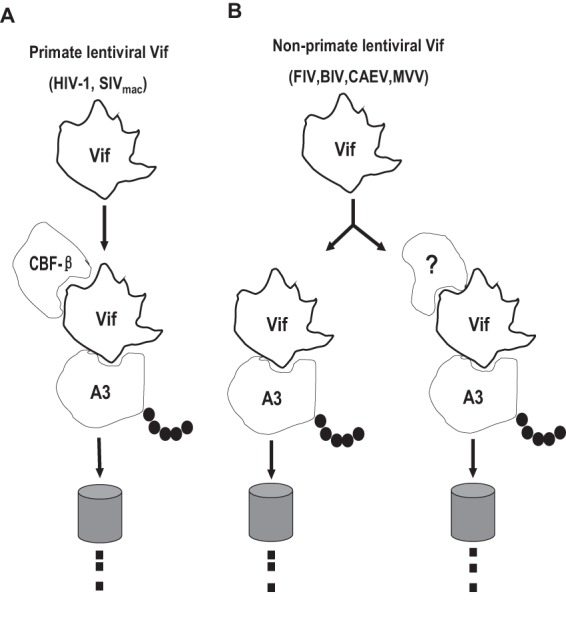

Numerous studies have demonstrated that CBF-β is necessary for the HIV-1 and SIV Vif functions, but the precise mechanisms are not fully understood. Thus, the nonrequirement of CBF-β in Vif-mediated APOBEC3 degradation by non-primate lentiviruses could provide a good model for uncovering why CBF-β is necessary for primate lentiviral Vif function. The compositions of primate APOBEC3 family members are far more complex than those of non-primate APOBEC3 family members. It is possible that during long-term virus-host interaction and coevolution, it was difficult for a single Vif to counter several APOBEC3 family members in primate lentiviruses (62). Thus, Vif may have gradually changed its structure and lost its ability to fold well and stabilize. Therefore, primate lentiviral Vifs may have evolved to depend on regulation by cellular factors such as CBF-β. The situation may have been different for non-primate lentiviruses. The environments of non-primate lentiviruses were milder, so Vifs could function without regulation by CBF-β. However, it is uncertain whether non-primate lentiviral Vifs can function on their own, so we propose a new model for the action of Vifs and cellular factors (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

Possible model of the relationship between primate and non-primate lentiviral Vifs and CBF-β. Non-primate lentiviral Vifs degrade APOBEC3 through different mechanisms. Primate lentiviral Vif, but not non-primate lentiviral Vif, needs CBF-β to degrade APOBEC3.

Furthermore, evidence is increasingly highlighting the important role of HIV-1 Vif in the interaction with CUL5 in the presence of CBF-β. Primate lentiviral Vif assembles with CUL5 through a conserved HCCH Zn finger motif (21, 56). However, non-primate lentiviral Vif-CUL5 interactions have been rarely studied. Interestingly, the HCCH motif is absent from non-primate lentiviral Vifs (21). In addition, BIV Vif and MVV Vif inefficiently interact with CUL5 (21). Although FIV Vif could coprecipitate with CUL5, the direct interaction between FIV Vif and CUL5 is unclear (49). Thus, it needs to be determined whether FIV Vif can directly recruit CUL5 or whether the interaction is mediated by Elongin B/C. In this respect, we inferred that there was no efficient interaction between non-primate lentiviral Vif and CUL5, which is why CBF-β is not needed to promote non-primate lentiviral Vif-CUL5 assembly.

More importantly, CBF-β is critical for the primate lentivirus function, and the domains of CBF-β that are required for the Vif or RUNX interaction partially overlap (31, 56). Therefore, the interruption of CBF-β–Vif interaction may be a crucial target for designing anti-HIV-1 drugs with no negative effects on the CBF-β–RUNX functions in cells (58). Non-primate lentiviral Vifs are insensitive to CBF-β, thereby indicating that non-primates are not suitable animal models for detecting the effects of these types of HIV-1 inhibitors. We propose that primates such as macaques would be more suitable candidates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yonghui Zheng for providing the plasmids expressing human A3G (A3G), chimpanzee A3G (A3Gcpz) and macaque A3G (A3Gmac).

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31072113 and 31222054) to Xiaojun Wang, a grant from the Central Public Interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (2012ZL080), and grants from the State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Biotechnology (SKLVBP201205 and SKLVBP201304).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 August 2014

REFERENCES

- 1. Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Choi JD, Malim MH. 2002. Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418:646–650. 10.1038/nature00939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mariani R, Chen D, Schrofelbauer B, Navarro F, Konig R, Bollman B, Munk C, Nymark-McMahon H, Landau NR. 2003. Species-specific exclusion of APOBEC3G from HIV-1 virions by Vif. Cell 114:21–31. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00515-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harris RS, Bishop KN, Sheehy AM, Craig HM, Petersen-Mahrt SK, Watt IN, Neuberger MS, Malim MH. 2003. DNA deamination mediates innate immunity to retroviral infection. Cell 113:803–809. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00423-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lecossier D, Bouchonnet F, Clavel F, Hance AJ. 2003. Hypermutation of HIV-1 DNA in the absence of the Vif protein. Science 300:1112. 10.1126/science.1083338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mangeat B, Turelli P, Caron G, Friedli M, Perrin L, Trono D. 2003. Broad antiretroviral defence by human APOBEC3G through lethal editing of nascent reverse transcripts. Nature 424:99–103. 10.1038/nature01709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marin M, Rose KM, Kozak SL, Kabat D. 2003. HIV-1 Vif protein binds the editing enzyme APOBEC3G and induces its degradation. Nat. Med. 9:1398–1403. 10.1038/nm946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang H, Yang B, Pomerantz RJ, Zhang C, Arunachalam SC, Gao L. 2003. The cytidine deaminase CEM15 induces hypermutation in newly synthesized HIV-1 DNA. Nature 424:94–98. 10.1038/nature01707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Newman EN, Holmes RK, Craig HM, Klein KC, Lingappa JR, Malim MH, Sheehy AM. 2005. Antiviral function of APOBEC3G can be dissociated from cytidine deaminase activity. Curr. Biol. 15:166–170. 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Turelli P, Trono D. 2005. Editing at the crossroad of innate and adaptive immunity. Science 307:1061–1065. 10.1126/science.1105964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rose KM, Marin M, Kozak SL, Kabat D. 2004. The viral infectivity factor (Vif) of HIV-1 unveiled. Trends Mol. Med. 10:291–297. 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bieniasz PD. 2004. Intrinsic immunity: a front-line defense against viral attack. Nat. Immunol. 5:1109–1115. 10.1038/ni1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Conticello SG, Harris RS, Neuberger MS. 2003. The Vif protein of HIV triggers degradation of the human antiretroviral DNA deaminase APOBEC3G. Curr. Biol. 13:2009–2013. 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu B, Yu X, Luo K, Yu Y, Yu XF. 2004. Influence of primate lentiviral Vif and proteasome inhibitors on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion packaging of APOBEC3G. J. Virol. 78:2072–2081. 10.1128/JVI.78.4.2072-2081.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mehle A, Strack B, Ancuta P, Zhang C, McPike M, Gabuzda D. 2004. Vif overcomes the innate antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by promoting its degradation in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 279:7792–7798. 10.1074/jbc.M313093200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Malim MH. 2003. The antiretroviral enzyme APOBEC3G is degraded by the proteasome in response to HIV-1 Vif. Nat. Med. 9:1404–1407. 10.1038/nm945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stopak K, de Noronha C, Yonemoto W, Greene WC. 2003. HIV-1 Vif blocks the antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by impairing both its translation and intracellular stability. Mol. Cell 12:591–601. 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00353-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu X, Yu Y, Liu B, Luo K, Kong W, Mao P, Yu XF. 2003. Induction of APOBEC3G ubiquitination and degradation by an HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-SCF complex. Science 302:1056–1060. 10.1126/science.1089591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mehle A, Goncalves J, Santa-Marta M, McPike M, Gabuzda D. 2004. Phosphorylation of a novel SOCS-box regulates assembly of the HIV-1 Vif-Cul5 complex that promotes APOBEC3G degradation. Genes Dev. 18:2861–2866. 10.1101/gad.1249904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yu Y, Xiao Z, Ehrlich ES, Yu X, Yu XF. 2004. Selective assembly of HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-ElonginB-ElonginC E3 ubiquitin ligase complex through a novel SOCS box and upstream cysteines. Genes Dev. 18:2867–2872. 10.1101/gad.1250204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stanley BJ, Ehrlich ES, Short L, Yu Y, Xiao Z, Yu XF, Xiong Y. 2008. Structural insight into the human immunodeficiency virus Vif SOCS box and its role in human E3 ubiquitin ligase assembly. J. Virol. 82:8656–8663. 10.1128/JVI.00767-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luo K, Xiao Z, Ehrlich E, Yu Y, Liu B, Zheng S, Yu XF. 2005. Primate lentiviral virion infectivity factors are substrate receptors that assemble with cullin 5-E3 ligase through a HCCH motif to suppress APOBEC3G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:11444–11449. 10.1073/pnas.0502440102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mehle A, Thomas ER, Rajendran KS, Gabuzda D. 2006. A zinc-binding region in Vif binds Cul5 and determines cullin selection. J. Biol. Chem. 281:17259–17265. 10.1074/jbc.M602413200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Paul I, Cui J, Maynard EL. 2006. Zinc binding to the HCCH motif of HIV-1 virion infectivity factor induces a conformational change that mediates protein-protein interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:18475–18480. 10.1073/pnas.0604150103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xiao Z, Ehrlich E, Yu Y, Luo K, Wang T, Tian C, Yu XF. 2006. Assembly of HIV-1 Vif-Cul5 E3 ubiquitin ligase through a novel zinc-binding domain-stabilized hydrophobic interface in Vif. Virology 349:290–299. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xiao Z, Ehrlich E, Luo K, Xiong Y, Yu XF. 2007. Zinc chelation inhibits HIV Vif activity and liberates antiviral function of the cytidine deaminase APOBEC3G. FASEB J. 21:217–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dang Y, Wang X, Zhou T, York IA, Zheng YH. 2009. Identification of a novel WxSLVK motif in the N terminus of human immunodeficiency virus and simian immunodeficiency virus Vif that is critical for APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F neutralization. J. Virol. 83:8544–8552. 10.1128/JVI.00651-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dang Y, Wang X, York IA, Zheng YH. 2010. Identification of a critical T(Q./D/E)x5ADx2(I/L) motif from primate lentivirus Vif proteins that regulate APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F neutralizing activity. J. Virol. 84:8561–8570. 10.1128/JVI.00960-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu Z, Bergeron JR, Atkinson RA, Schaller T, Veselkov DA, Oregioni A, Yang Y, Matthews SJ, Malim MH, Sanderson MR. 2013. Insight into the HIV-1 Vif SOCS-box-ElonginBC interaction. Open Biol. 3:130100. 10.1098/rsob.130100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jäger S, Kim DY, Hultquist JF, Shindo K, LaRue RS, Kwon E, Li M, Anderson BD, Yen L, Stanley D, Mahon C, Kane J, Franks-Skiba K, Cimermancic P, Burlingame A, Sali A, Craik CS, Harris RS, Gross JD, Krogan NJ. 2012. Vif hijacks CBF-beta to degrade APOBEC3G and promote HIV-1 infection. Nature 481:371–375. 10.1038/nature10693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang W, Du J, Evans SL, Yu Y, Yu XF. 2012. T-cell differentiation factor CBF-beta regulates HIV-1 Vif-mediated evasion of host restriction. Nature 481:376–379. 10.1038/nature10718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hultquist JF, McDougle RM, Anderson BD, Harris RS. 2012. HIV type 1 viral infectivity factor and the RUNX transcription factors interact with core binding factor beta on genetically distinct surfaces. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 28:1543–1551. 10.1089/aid.2012.0142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Salter JD, Lippa GM, Belashov IA, Wedekind JE. 2012. Core-binding factor beta increases the affinity between human Cullin 5 and HIV-1 Vif within an E3 ligase complex. Biochemistry 51:8702–8704. 10.1021/bi301244z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hultquist JF, Binka M, LaRue RS, Simon V, Harris RS. 2012. Vif proteins of human and simian immunodeficiency viruses require cellular CBFbeta to degrade APOBEC3 restriction factors. J. Virol. 86:2874–2877. 10.1128/JVI.06950-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou X, Evans SL, Han X, Liu Y, Yu XF. 2012. Characterization of the interaction of full-length HIV-1 Vif protein with its key regulator CBFbeta and CRL5 E3 ubiquitin ligase components. PLoS One 7:e33495. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim DY, Kwon E, Hartley PD, Crosby DC, Mann S, Krogan NJ, Gross JD. 2013. CBFbeta stabilizes HIV Vif to counteract APOBEC3 at the expense of RUNX1 target gene expression. Mol. Cell 49:632–644. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhou X, Han X, Zhao K, Du J, Evans SL, Wang H, Li P, Zheng W, Rui Y, Kang J, Yu XF. 2014. Dispersed and conserved hydrophobic residues of HIV-1 Vif are essential for CBFbeta recruitment and A3G suppression. J. Virol. 88:2555–2563. 10.1128/JVI.03604-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fribourgh JL, Nguyen HC, Wolfe LS, Dewitt DC, Zhang W, Yu XF, Rhoades E, Xiong Y. 2014. Core binding factor beta plays a critical role by facilitating the assembly of the vif-cullin 5 e3 ubiquitin ligase. J. Virol. 88:3309–3319. 10.1128/JVI.03824-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Miyagi E, Kao S, Yedavalli V, Strebel K. 2014. CBFbeta enhances de novo protein biosynthesis of its binding partners HIV-1 Vif and RUNX1 and potentiates the Vif-induced degradation of APOBEC3G. J. Virol. 88:4839–4852. 10.1128/JVI.03359-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ito Y. 2008. RUNX genes in development and cancer: regulation of viral gene expression and the discovery of RUNX family genes. Adv. Cancer Res. 99:33–76. 10.1016/S0065-230X(07)99002-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. de Bruijn MF, Speck NA. 2004. Core-binding factors in hematopoiesis and immune function. Oncogene 23:4238–4248. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Klunker S, Chong MM, Mantel PY, Palomares O, Bassin C, Ziegler M, Ruckert B, Meiler F, Akdis M, Littman DR, Akdis CA. 2009. Transcription factors RUNX1 and RUNX3 in the induction and suppressive function of Foxp3+ inducible regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 206:2701–2715. 10.1084/jem.20090596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kitoh A, Ono M, Naoe Y, Ohkura N, Yamaguchi T, Yaguchi H, Kitabayashi I, Tsukada T, Nomura T, Miyachi Y, Taniuchi I, Sakaguchi S. 2009. Indispensable role of the Runx1-Cbfbeta transcription complex for in vivo-suppressive function of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Immunity 31:609–620. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang S, Wang Q, Crute BE, Melnikova IN, Keller SR, Speck NA. 1993. Cloning and characterization of subunits of the T-cell receptor and murine leukemia virus enhancer core-binding factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:3324–3339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pepling ME, Gergen JP. 1995. Conservation and function of the transcriptional regulatory protein Runt. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:9087–9091. 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim WY, Sieweke M, Ogawa E, Wee HJ, Englmeier U, Graf T, Ito Y. 1999. Mutual activation of Ets-1 and AML1 DNA binding by direct interaction of their autoinhibitory domains. EMBO J. 18:1609–1620. 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tang YY, Crute BE, Kelley JJ, Huang X, Yan J, Shi J, Hartman KL, Laue TM, Speck NA, Bushweller JH. 2000. Biophysical characterization of interactions between the core binding factor alpha and beta subunits and DNA. FEBS Lett. 470:167–172. 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01312-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. LaRue RS, Jonsson SR, Silverstein KA, Lajoie M, Bertrand D, El-Mabrouk N, Hotzel I, Andresdottir V, Smith TP, Harris RS. 2008. The artiodactyl APOBEC3 innate immune repertoire shows evidence for a multi-functional domain organization that existed in the ancestor of placental mammals. BMC Mol. Biol. 9:104. 10.1186/1471-2199-9-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Larue RS, Lengyel J, Jonsson SR, Andresdottir V, Harris RS. 2010. Lentiviral Vif degrades the APOBEC3Z3/APOBEC3H protein of its mammalian host and is capable of cross-species activity. J. Virol. 84:8193–8201. 10.1128/JVI.00685-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang J, Zhang W, Lv M, Zuo T, Kong W, Yu X. 2011. Identification of a Cullin5-ElonginB-ElonginC E3 complex in degradation of feline immunodeficiency virus Vif-mediated feline APOBEC3 proteins. J. Virol. 85:12482–12491. 10.1128/JVI.05218-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang X, Abudu A, Son S, Dang Y, Venta PJ, Zheng YH. 2011. Analysis of human APOBEC3H haplotypes and anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity. J. Virol. 85:3142–3152. 10.1128/JVI.02049-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yin X, Hu Z, Gu Q, Wu X, Zheng YH, Wei P, Wang X. 2014. Equine tetherin blocks retrovirus release and its activity is antagonized by equine infectious anemia virus envelope protein. J. Virol. 88:1259–1270. 10.1128/JVI.03148-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zielonka J, Marino D, Hofmann H, Yuhki N, Lochelt M, Munk C. 2010. Vif of feline immunodeficiency virus from domestic cats protects against APOBEC3 restriction factors from many felids. J. Virol. 84:7312–7324. 10.1128/JVI.00209-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yang S, Sun Y, Zhang H. 2001. The multimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type I Vif protein: a requirement for Vif function in the viral life cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 276:4889–4893. 10.1074/jbc.M004895200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yang B, Gao L, Li L, Lu Z, Fan X, Patel CA, Pomerantz RJ, DuBois GC, Zhang H. 2003. Potent suppression of viral infectivity by the peptides that inhibit multimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Vif proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 278:6596–6602. 10.1074/jbc.M210164200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Batisse J, Guerrero SX, Bernacchi S, Richert L, Godet J, Goldschmidt V, Mely Y, Marquet R, de Rocquigny H, Paillart JC. 2013. APOBEC3G impairs the multimerization of the HIV-1 Vif protein in living cells. J. Virol. 87:6492–6506. 10.1128/JVI.03494-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Guo Y, Dong L, Qiu X, Wang Y, Zhang B, Liu H, Yu Y, Zang Y, Yang M, Huang Z. 2014. Structural basis for hijacking CBF-beta and CUL5 E3 ligase complex by HIV-1 Vif. Nature 505:229–233. 10.1038/nature12884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang X, Dolan PT, Dang Y, Zheng YH. 2007. Biochemical differentiation of APOBEC3F and APOBEC3G proteins associated with HIV-1 life cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 282:1585–1594. 10.1074/jbc.M610150200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Du J, Zhao K, Rui Y, Li P, Zhou X, Zhang W, Yu XF. 2013. Differential requirements for HIV-1 Vif-mediated APOBEC3G degradation and RUNX1-mediated transcription by core binding factor beta. J. Virol. 87:1906–1911. 10.1128/JVI.02199-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Han X, Liang W, Hua D, Zhou X, Du J, Evans SL, Gao Q, Wang H, Viqueira R, Wei W, Zhang W, Yu XF. 2014. Evolutionarily conserved requirement for core binding factor beta in the assembly of the human immunodeficiency virus/simian immunodeficiency virus Vif-Cullin 5-RING E3 ubiquitin ligase. J. Virol. 88:3320–3328. 10.1128/JVI.03833-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Matsui Y, Shindo K, Nagata K, Io K, Tada K, Iwai F, Kobayashi M, Kadowaki N, Harris RS, Takaori-Kondo A. 2014. Defining HIV-1 Vif residues that interact with CBFbeta by site-directed mutagenesis. Virology 449:82–87. 10.1016/j.virol.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wang H, Liu B, Liu X, Li Z, Yu XF, Zhang W. 2014. Identification of HIV-1 Vif regions required for CBF-beta interaction and APOBEC3 suppression. PLoS One 9:e95738. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Desimmie BA, Delviks-Frankenberrry KA, Burdick RC, Qi D, Izumi T, Pathak VK. 2014. Multiple APOBEC3 restriction factors for HIV-1 and one Vif to rule them all. J. Mol. Biol. 426:1220–1245. 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]