ABSTRACT

Flaviviruses are thought to sample an ensemble of structures at equilibrium. One consequence of a structurally dynamic virion is the observed time-dependent increases in neutralization sensitivity that can occur after prolonged incubation with antibody. Differences in how virus strains “breathe” may affect epitope exposure and contribute to the underlying mechanisms of strain-dependent neutralization sensitivity. Beyond the contribution of structural dynamics, flaviviruses exist as a structurally heterogeneous population due to an inefficient virion maturation process. Here, we investigate the interplay between virion maturation and structural dynamics that contributes to antibody-mediated neutralization. Using West Nile (WNV) and dengue (DENV) viruses produced under conditions that modify the extent of virion maturation, we investigated time-dependent changes in neutralization sensitivity associated with structural dynamics. Our results identify distinct patterns of neutralization against viruses that vary markedly with respect to the extent of virion maturation. Reducing the efficiency of virion maturation resulted in greater time-dependent changes in neutralization potency and a marked reduction in the stability of the particle at 37°C compared to more mature virus. The fact that the neutralization sensitivity of WNV and DENV did not increase after prolonged incubation in the absence of antibody, regardless of virion maturation, suggests that the dynamic processes that govern epitope accessibility on infectious viruses are reversible. Against the backdrop of heterogeneous flavivirus structures, differences in the pathways by which viruses “breathe” represent an additional layer of complexity in understanding maturation state-dependent patterns of antibody recognition.

IMPORTANCE Flaviviruses exist as a group of related structures at equilibrium that arise from the dynamic motion of E proteins that comprise the antigenic surface of the mature virion. This process has been characterized for numerous viruses and is referred to as viral “breathing.” Additionally, flaviviruses are structurally heterogeneous due to an inefficient maturation process responsible for cleaving prM on the virion surface. Both of these mechanisms vary the exposure of antigenic sites available for antibody binding and impact the ability of antibodies to neutralize infection. We demonstrate that virions with inefficient prM cleavage “breathe” differently than their more mature counterparts, resulting in distinct patterns of neutralization sensitivity. Additionally, the maturation state was found to impact virus stability in solution. Our findings provide insight into the complex flavivirus structures that contribute to infection with the potential to impact antibody recognition.

INTRODUCTION

Flaviviruses are small, enveloped, single-stranded RNA viruses that cause significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. West Nile (WNV) and dengue (DENV) viruses are members of this genus that are transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected mosquito. While the majority of WNV infections are subclinical, symptomatic disease ranges from mild fever to potentially fatal neurological complications. Endemic in many parts of the world, WNV was introduced into North America in 1999 and has become the leading cause of arbovirus-related neuroinvasive disease in the United States, responsible for ∼3,000 cases in 2012 alone (1, 2). Approximately 3.6 billion people live in areas of DENV endemicity, resulting in an estimated 390 million infections each year (3, 4). While the majority of these infections are also subclinical, clinically apparent cases range from a self-limiting severe fever (dengue fever [DF]) to life-threatening vascular leakage syndromes (dengue hemorrhagic fever and shock syndrome [DHF/DSS]) (5). Recent estimates suggest that 96 million people develop symptomatic infections each year (3, 4). Currently, there are no licensed human vaccines or treatments for either of these viruses.

Flavivirus virions are comprised of three structural proteins (capsid [C], precursor-to-membrane [prM], and envelope [E]) that coordinate the encapsidation of the ∼11-kb viral genomic RNA within an endoplasmic-reticulum-derived lipid membrane. Maturation of the virus particle from a noninfectious immature form to an infectious mature virion occurs during viral egress from an infected cell. Immature virions incorporate 60 icosahedrally arranged trimeric spikes of E-prM dimers (6, 7). The defining event of the flavivirus maturation process is the cleavage of the prM protein by a furin-like serine protease within the trans-Golgi network. For this to occur, the E proteins of immature virions undergo a low-pH-mediated structural rearrangement that exposes a furin cleavage site within prM (8). The cleaved “pr” portion of prM remains associated with the virion until release from the cell, where it dissociates in the neutral pH of the extracellular space. Fully mature virions incorporate E proteins as 90 homodimers arranged in a herringbone configuration and contain no uncleaved prM protein (9, 10). Several lines of evidence indicate that prM cleavage may be inefficient and that infectious virions released from cells may retain uncleaved prM (11). The extent of prM cleavage required for the transition from a noninfectious immature virus particle to an infectious virion is unknown.

The generation of a protective neutralizing antibody response is a primary goal of vaccine development efforts for numerous flaviviruses (12). The major target of neutralizing anti-flavivirus antibodies is the E protein (13). Antibodies that bind to prM have also been identified, although they generally display weak neutralizing activity in vitro (14, 15). Flavivirus neutralization is a “multiple-hit” mechanism that requires binding of a critical number of antibody molecules to an individual virion (16–18). The dense arrangement of E proteins on the virion introduces significant complexity for antibody recognition; epitope accessibility may vary as a function of the location of an E protein on the virus particle (19, 20). Many epitopes are not predicted to be exposed on the virion in sufficient numbers to reach the neutralization threshold (21–24). This provides an explanation for the observation that high-affinity interactions are not always a predictor of potent neutralization (24–27). Epitope accessibility may be impacted by the presence of uncleaved prM on the virion (23). Many antibodies display markedly increased neutralization potency against viruses that retain significant uncleaved prM (24, 28–30).

Recent evidence suggests that flaviviruses explore an ensemble of conformations at equilibrium, referred to as viral structural dynamics, or “breathing” (28, 31, 32). The structural dynamics of several classes of viruses have been documented (33, 34). For both WNV and DENV, increasing the time or temperature of the incubation of virions and antibody results in increased neutralization potency (22, 28). The structural dynamics of the virion provides an explanation for this increase in neutralization activity; epitopes may be differentially accessible among members of a structural ensemble. The structural heterogeneity arising from incomplete cleavage of prM raises the possibility that partially mature virions have distinct structural ensembles or pathways by which these viruses “breathe”. In this study, we investigate the interplay of structural dynamics and virion maturation on antibody-mediated neutralization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

Cell lines were maintained at 37°C in the presence of 7% CO2. HEK-293T cells were grown in complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing Glutamax (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 7% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT) and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (PS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). When producing virus particles, a low-glucose formulation of DMEM containing HEPES (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), also supplemented with 7% FBS and 100 U/ml PS, was substituted. Use of this medium lowers the rate of medium acidification, which has the potential to prematurely trigger (and thus inactivate) flaviviruses. Raji cells expressing the attachment factor DC-SIGNR (Raji-DCSIGNR) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing Glutamax (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and supplemented with 7% FBS and 100 U/ml PS.

Production of WNV and DENV RVPs.

Reporter virus particles (RVPs) are pseudoinfectious virions produced by genetic complementation of a viral subgenomic replicon with the structural genes in trans. RVPs are capable of only a single round of infection (35, 36). WNV RVPs were generated by cotransfection of HEK-293T cells with a plasmid carrying the structural genes (C-prM-E) of WNV lineage I strain NY99 and a WNV lineage II replicon that expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) (using a 3:1 ratio of plasmid DNA by mass). DENV RVPs were produced by swapping the WNV structural-gene plasmid for one that encodes the C-prM-E of the DENV serotype 2 (DENV2) strain 16681 or serotype 1 (DENV1) strain Western Pacific-74 (WP) or 16007. Transfected cells were incubated at either 37°C (WNV RVPs) or 30°C (DENV RVPs). RVP-containing supernatants were harvested between 24 and 96 h posttransfection, filtered over a 0.2-μM membrane, and frozen in aliquots at −80°C.

Manipulating the efficiency of prM cleavage.

The efficiency of virion maturation (prM cleavage) during RVP production was altered using modifications of previously described methods (24, 28, 29, 37). RVPs with low to undetectable levels of uncleaved prM (referred to here as WNV-furin and DENV-furin) were produced by including a plasmid expressing human furin in complementation experiments (at a ratio of 3:1:1 [by mass] of plasmids carrying the structural, replicon, and furin genes, respectively). WNV RVPs that retain significant uncleaved prM (WNV-prM+) were produced by supplementing the media of producer cells with the weak base ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) to a final concentration of 20 mM. The presence of NH4Cl inhibits prM cleavage by raising the internal pH of the cell and preventing the low-pH-dependent exposure of the furin cleavage site within prM (38). For unknown reasons, NH4Cl treatment during production of DENV RVPs resulted in titers that were insufficient for use in neutralization studies. Instead, DENV-prM+ RVPs produced in the presence of 25 μM Dec-RVKR-CMK furin inhibitor (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY) were used for the experiments described below.

Determining the titer and specific infectivity of RVPs.

Titer data were obtained by infecting Raji-DCSIGNR cells with serial 2-fold dilutions of RVPs at 37°C. Infection was assessed by GFP expression 48 h postinfection using flow cytometry. Quantitation of RNA was performed by extraction of viral RNA using the QIAamp Viral RNA minikit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), followed by quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR using primers specific for the WNV lineage II replicon (24). Virus specific infectivity was analyzed by comparing titer and RNA data obtained from equivalent dilutions of virus.

Analysis of the maturation state of RVPs.

To evaluate the efficiency of prM cleavage in WNV RVP preparations, aliquots of WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin RVPs were partially purified by centrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion; lysed in buffer containing 1% Triton, 100 mM Tris, 2 M NaCl, and 100 mM EDTA; and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting. WNV E protein was detected with the monoclonal antibody (MAb) 4G2 (1 μg/ml), whereas prM and M were detected using a commercial anti-WNV reactive polyclonal antibody (1:250 dilution) that is specific for residues 8 to 27 of the WNV M protein (Imgenex, San Diego, CA). To complement this approach, neutralization studies were performed using MAbs shown previously to be sensitive to the maturation state of the virion (24). Western blot analysis of DENV RVP preparations was not possible due to the lack of a suitable anti-DENV prM antibody. The efficiency of prM cleavage on infectious DENV RVPs was assessed functionally using maturation state-sensitive neutralizing antibodies.

RVP intrinsic-decay curves.

For intrinsic-decay experiments, RVPs were diluted to the same level of infection as used in neutralization assays described below. After preincubating diluted RVP stocks at 37°C for 1 h, samples were further incubated at 37°C for up to 4 days. At the indicated times, aliquots were removed and frozen at −80°C. All frozen samples from a given experiment were thawed simultaneously and used to infect Raji-DCSIGNR cells in triplicate. Infectivity was determined 48 h postinfection by flow cytometry and normalized to levels obtained immediately after the preincubation step. The results were fitted with a single-phase exponential-decay curve to estimate the half-life of infectivity (Prism; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Neutralization dose-response studies.

The neutralization activities of MAbs were measured using WNV and DENV RVPs as described previously (24, 28, 29). RVPs were sufficiently diluted to ensure antibody excess at informative points of the dose-response curve and incubated with nine serial dilutions of the indicated MAbs for 1 h at room temperature (WNV) or 37°C (DENV). The use of a 37°C preincubation for DENV experiments reflects the finding that certain DENV-specific antibodies may require elevated temperature to bind the virus (31). In both instances, this preincubation has been shown to be sufficient to allow steady-state binding (28). After preincubation, antibody-virus complexes were either immediately used to infect Raji-DCSIGNR cells or further incubated at 37°C for incremental lengths of time before the addition of cells. As previously described, increasing the length of the incubation allows assessment of the effects of the structural dynamics of the virion on virus-antibody interactions (28). In some experiments, RVPs were incubated alone at 37°C for the indicated lengths of time, followed by the addition of serial dilutions of MAb 1 h prior to infection of target cells. In all experiments, Raji-DCSIGNR infections were carried out at 37°C and infectivity was monitored by flow cytometry 48 h later. Dose-response profiles generated from cells infected with virus-antibody complexes immediately after the preincubation are referred to as reference curves. Neutralization results were analyzed by nonlinear regression (using a variable slope) to estimate the 50% effective concentration (EC50) (Prism; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Manipulating the levels of uncleaved prM in populations of WNV RVPs.

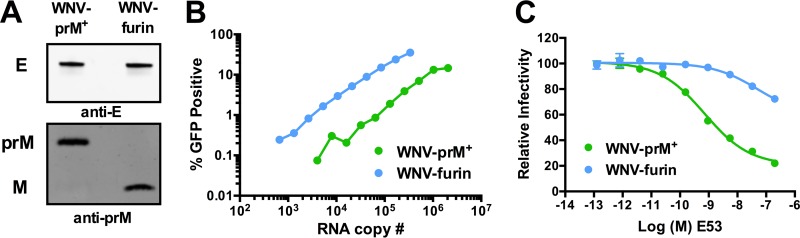

To study how changes in the maturation state of WNV impact the ensemble of structures recognized by antibodies, we created WNV RVPs that varied significantly with respect to the efficiency of prM cleavage. WNV RVPs were produced by cotransfection of a WNV replicon with the viral structural genes in trans. In order to decrease the efficiency of virion maturation, RVPs were produced in the presence of NH4Cl and are referred to here as WNV-prM+. Relatively homogeneous populations of RVPs with undetectable levels of uncleaved prM (WNV-furin) were produced in cells that overexpress human furin. Differences in the efficiencies of virion maturation between these RVP populations were confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 1A). A comparison of RVP infectivity versus viral RNA genome copies revealed the expected reduction in specific infectivity associated with a decrease in the efficiency of virion maturation (Fig. 1B) (24, 29, 39). The reduced specific infectivity of WNV-prM+ reflects the presence of virions in the supernatant that are either fully immature or retain levels of uncleaved prM that preclude infectivity; such virions are invisible in functional assays. A significant difference in specific infectivity of WNV-furin and WNV-prM+ was observed among three independent preparations (P = 0.04), consistent with numerous prior studies from our laboratory (24, 29, 39). To further confirm differences in the maturation states of infectious RVPs, we performed neutralization studies with the maturation state-sensitive neutralizing MAb E53 (Fig. 1C). Structural and functional studies of MAb E53 have demonstrated that the E protein domain II fusion loop epitope bound by the antibody is accessible only on the trimeric E proteins present on immature and partially mature virions (23, 24). As anticipated, E53 efficiently neutralized WNV-prM+, but not WNV-furin.

FIG 1.

Manipulation of the levels of uncleaved prM to generate WNV RVPs in differing maturation states. WNV RVPs were produced in HEK-293T cells by cotransfection of a WNV subgenomic replicon that expresses GFP and a second plasmid carrying the WNV structural genes. RVPs were produced in the presence of either ammonium chloride or an overexpression of furin to yield virions with high (WNV-prM+) or undetectable (WNV-furin) levels of uncleaved prM, respectively. (A) Differences in the extents of prM cleavage between the two RVP populations were confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using WNV E- and prM-specific Abs. (B) The RVP infectious titer was measured by infecting Raji-DCSIGNR cells with serial 2-fold dilutions of virus supernatant in duplicate. Infectivity was monitored 48 h later by flow cytometry. The average infectivity, as measured by the percentage of cells expressing GFP, is shown relative to the viral RNA genome content, measured by qRT-PCR. The results are representative of data obtained with three independent preparations of WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin produced in parallel. (C) WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin were incubated with serial dilutions of the maturation state-sensitive MAb E53 for 1 h at room temperature to allow the binding reaction to reach equilibrium, followed by infection of Raji-DCSIGNR cells and further incubation at 37°C. Infectivity was monitored 48 h later by flow cytometry. The error bars indicate the range of duplicate infections. The results are representative of two independent experiments.

The infectious half-life of WNV in solution is impacted by the extent of virus maturation.

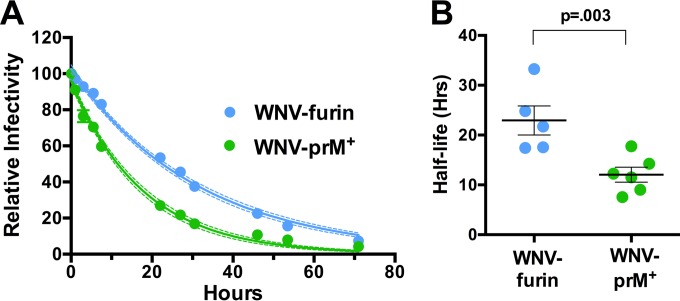

Incubation of viruses in solution results in a loss of infectivity that we refer to as intrinsic decay; the structural basis of this phenomenon for flaviviruses is unknown. We hypothesized that the intrinsic decay of WNV may be a product of the structural dynamics of the virion. On a dynamic virus particle, E proteins may sample conformations for which it is energetically unfavorable to return to the previous state. These “dead-end” structures may no longer be compatible with infectivity and therefore become invisible in functional assays. A similar phenomenon has been observed and extensively characterized with picornaviruses, resulting in the formation of the A particle (40). We have shown previously that not all flaviviruses share the same intrinsic-decay rate (35). To explore whether the maturation state impacts the functional stability of WNV, WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin RVPs were allowed to equilibrate at 37°C for 1 h, after which samples were harvested and frozen at the indicated time points. The infectivity of individual samples was determined by infecting Raji-DCSIGNR cells, and the resulting data were fitted to a one-phase decay curve to estimate the half-life of infectivity (Fig. 2A). We observed that WNV-prM+ decays at a rate that is ∼1.8-fold higher than that of WNV-furin (average half-life, 12.7 and 22.9 h, respectively; P = 0.003) (Fig. 2B). This result suggests that WNV becomes less stable in solution as the levels of uncleaved prM remaining on the virion increase.

FIG 2.

Intrinsic decay of WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin infectivity. (A) Populations of WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin were equilibrated to 37°C, after which samples were harvested and frozen at the indicated times. The infectivity at each point was determined by infection of Raji-DCSIGNR cells and monitored by flow cytometry 48 h postinfection. The data are normalized to the infectivity of RVPs at the initial time point (after a 1-h 37°C preincubation) and fitted to a single-phase exponential-decay curve to obtain the half-life of virus infectivity. For the representative experiment shown, the dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals of the regression analysis and the error bars represent the standard errors of triplicate measurements. (B) The results of individual experiments (n = 5 for WNV-furin; n = 6 for WNV-prM+), each performed in triplicate, are shown. The error bars represent the standard errors, and the horizontal lines show the means of all experiments. The P value was determined using Student's t test.

Neutralization potency against WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin at the kinetic limit.

We have previously shown that the neutralization potency of anti-flavivirus antibodies is enhanced by increasing the length or temperature of virus-antibody interactions (28). Importantly, time-dependent increases in neutralization are finite. At the “kinetic limit,” continued incubation of antibody and virus does not result in further increases in neutralization potency, consistent with the interpretation that changes in neutralization activity correspond to the time required for exposure of a threshold number of epitopes on each virion. Measurements of the kinetic limit provide a reproducible method for comparing the impacts of structural dynamics on antibody recognition among virus preparations and MAbs.

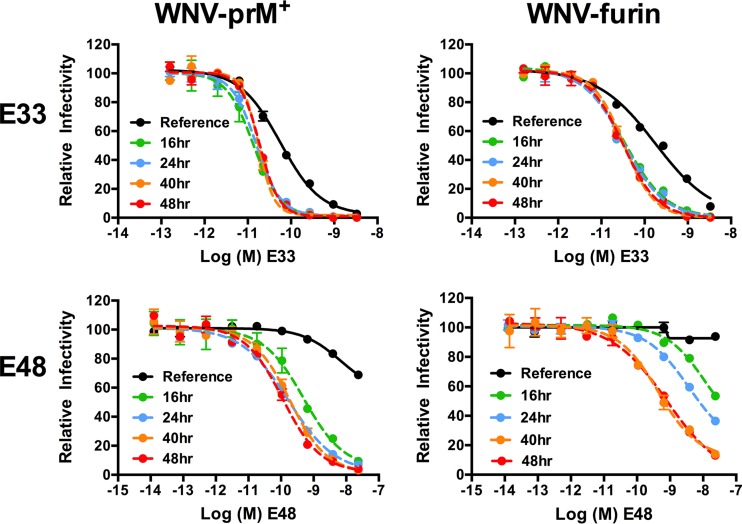

Using a panel of six MAbs representing various specificities within the E protein (20, 41–43), we performed dose-response neutralization studies to explore the limits of time-dependent neutralization against WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin (Fig. 3 and data not shown). After a 1-h preincubation of virus with antibody at room temperature to allow the binding reaction to reach steady state, antibody-virus complexes were either immediately added to Raji-DCSIGNR cells (Fig. 3, reference neutralization curve) or further incubated at 37°C for incremental lengths of time before the addition of cells (Fig. 3, dashed lines). The reference curves and neutralization profiles generated after 16, 24, 40, and 48 h of incubation at 37°C are shown for two MAbs (E33 and E48) (Fig. 3). In concordance with our previous findings, prolonged incubation of WNV with antibody resulted in large increases in neutralization potency, consistent with a requirement for the exposure and subsequent antibody binding of otherwise inaccessible epitopes (28). While the length of incubation required to reach the kinetic limit varied with the MAb and the maturation status of the virus preparation, no further increases in neutralization were detected after ∼40 h at 37°C (Fig. 3). The fact that a 40-h incubation was sufficient to reach the kinetic limit was confirmed for the remaining four MAbs in the panel (E16, E22, E60, and E121) (data not shown). At this incubation time, all epitopes capable of being exposed in the structural ensemble of an infectious WNV virion have become available for antibody recognition.

FIG 3.

Limits of a kinetic impact on patterns of WNV neutralization. WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin RVPs were incubated with serial dilutions of the indicated MAbs for 1 h at room temperature, followed by infection of Raji-DCSIGNR cells to generate reference neutralization curves (solid black lines). Additional antibody-RVP complexes were further incubated at 37°C for the indicated lengths of time before the addition of cells. Infectivity was assessed 48 h postinfection by flow cytometry. The results from a representative experiment are displayed relative to the infectivity in the absence of antibody at each individual time point. The error bars display the range of duplicate or triplicate infections. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

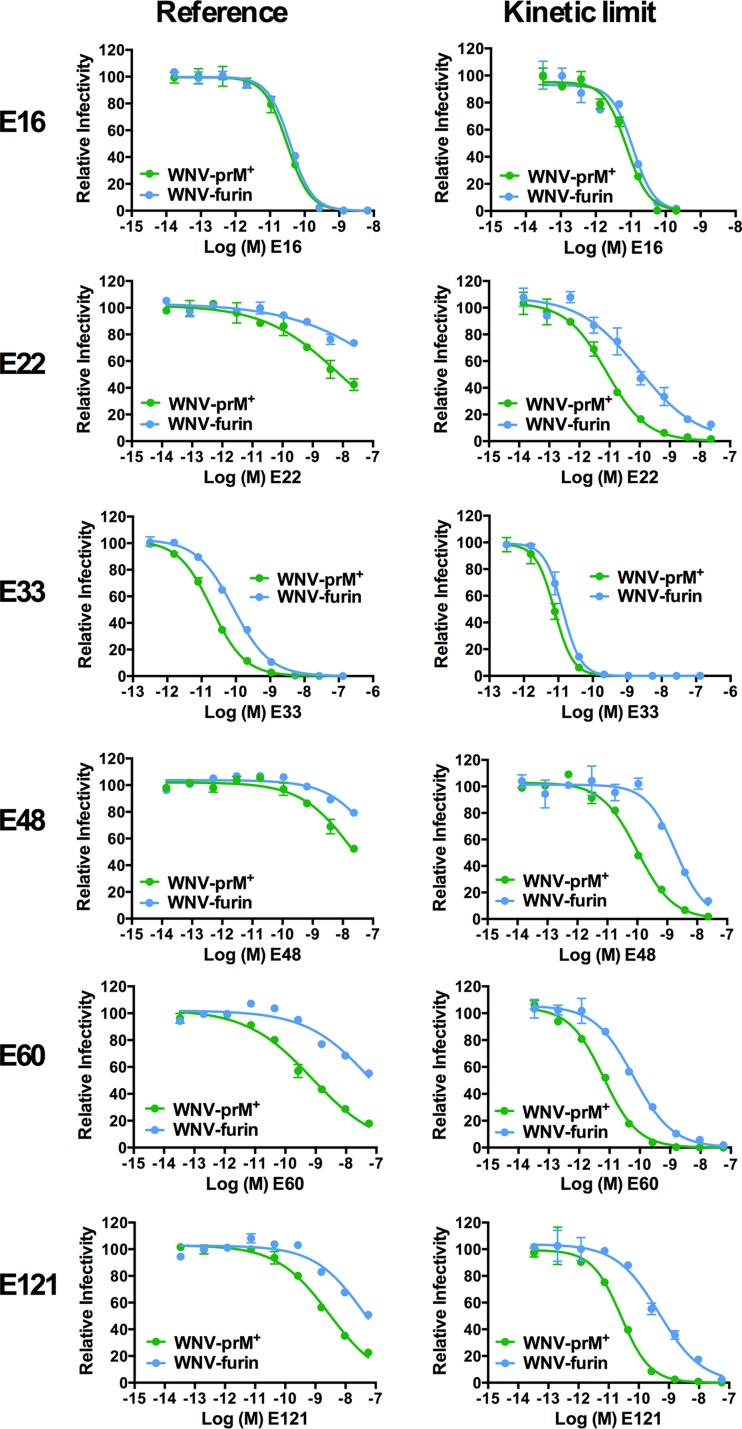

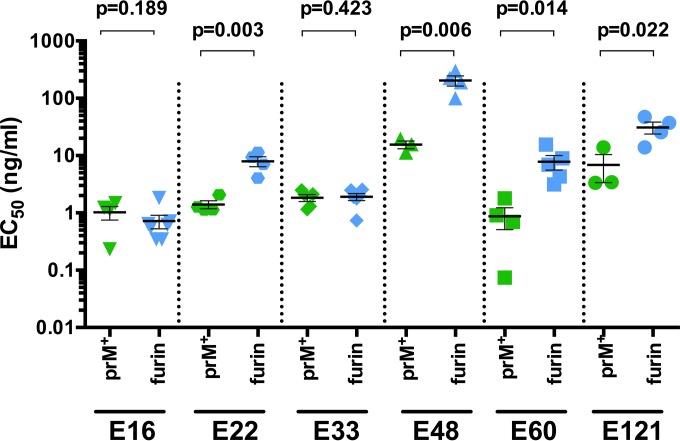

For all six MAbs, antibody dose-response curves at the reference time point (infection of Raji-DCSIGNR cells after a 1-h preincubation at room temperature) and the kinetic limit (infection after preincubation plus an additional ≥40 h at 37°C) were compiled for WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin (Fig. 4). Antibodies that bind the solvent-accessible lateral ridge of E domain III (E-DIII-LR) have been shown to be only modestly (MAb E33) or not at all (MAb E16) sensitive to the maturation state of WNV (24, 41). The maturation state dependence of MAb E33 reflects steric hindrance of the Fc region of the antibody, as opposed to differences in the solvent accessibility of the E-DIII-LR epitope between WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin (41). E16 and E33 neutralize WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin equivalently at the kinetic limit (Fig. 4). This is further confirmed by comparison of the EC50s calculated at the kinetic limit against WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin (Fig. 5) (P = 0.189 and P = 0.423 for MAbs E16 and E33, respectively). The remaining four MAbs (E22, E48, E60, and E121) have previously been mapped to epitopes not predicted to be fully accessible on the surface of the mature virion (42, 43). As anticipated, all were significantly sensitive to the maturation state of WNV at the reference time point; in each instance, WNV-prM+ was more susceptible to neutralization than WNV-furin (Fig. 4) (24, 29). Furthermore, for these four MAbs, the sensitivities of WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin RVPs at the kinetic limit remained significantly different (Fig. 4 and 5). These results suggest that the presentations of epitopes on the structural ensembles sampled by WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin are distinct.

FIG 4.

Prolonged incubation reveals distinct patterns of neutralization of WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin RVPs. WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin RVPs were incubated with serial dilutions of the indicated MAbs for 1 h at room temperature, followed by infection of Raji-DCSIGNR cells to generate reference neutralization curves (left). Additional antibody-RVP complexes were further incubated at 37°C for ≥40 h before the addition of Raji-DCSIGNR cells to generate kinetic-limit neutralization curves (right). Infectivity was assessed 48 h postinfection by flow cytometry. The results from a representative experiment are displayed relative to the infectivity in the absence of antibody at each time point. The error bars display the range of duplicate or triplicate infections. The results are representative of three to seven independent experiments. The panel of MAbs is specific for epitopes on the E-DI lateral ridge (E121), E-DII central interface (E48), E-DII fusion loop (E60), E-DIII lateral ridge (E16 and E33), and E-DIII outside the lateral ridge (E22) (20, 41–43).

FIG 5.

Neutralization potency against WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin at the kinetic limit. EC50s were calculated from neutralization curves generated after incubation of WNV-prM+ or WNV-furin with serial dilutions of the indicated MAbs for ≥40 h at 37°C before infection of Raji-DCSIGNR cells, as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The results of three to seven individual experiments for each virus-MAb pair are shown. The horizontal lines and error bars depict the means and standard errors, respectively. The EC50s at the kinetic limit for WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin were compared using Student's t test.

Changes in neutralization sensitivity following prolonged incubation in the absence of antibody.

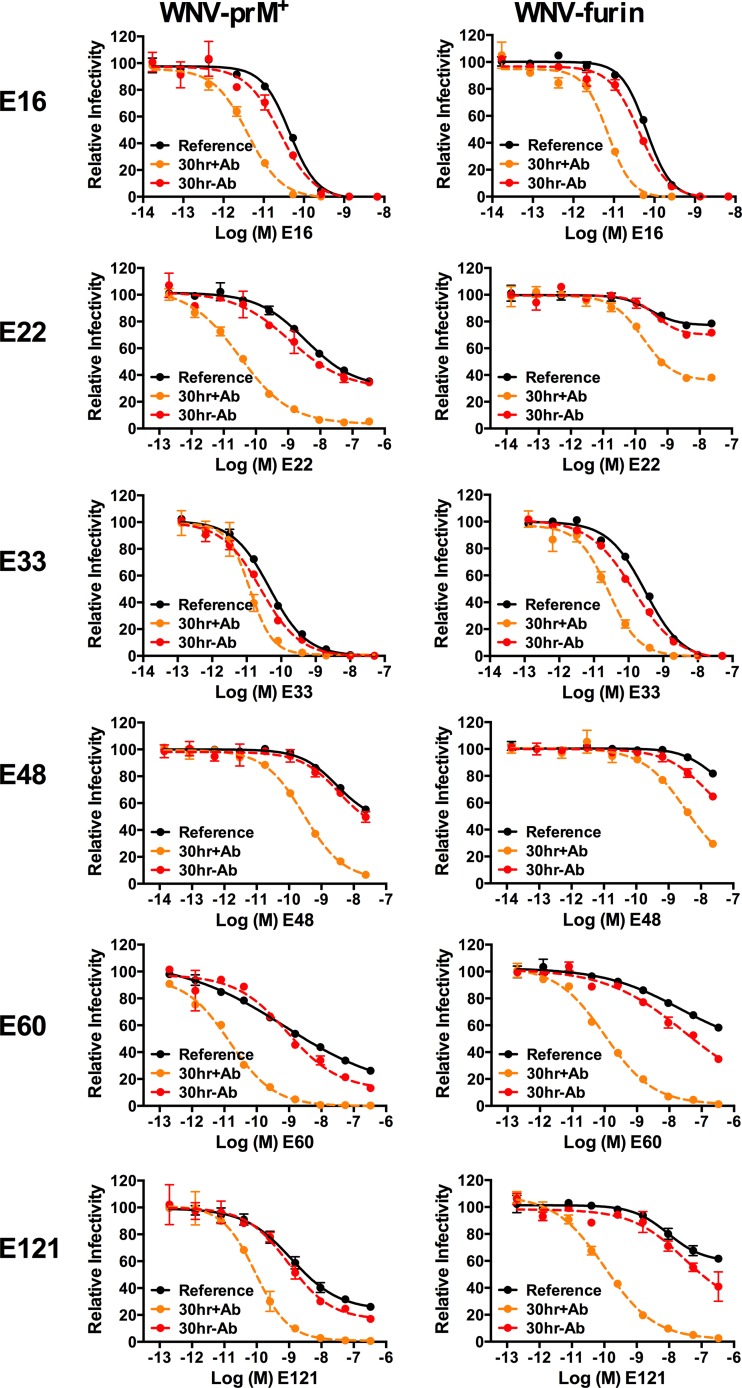

We hypothesize that changes in the surface of the virion that occur during viral “breathing” have the potential to impact antibody recognition (28). In this model, antibodies bind (and therefore trap) epitopes as they are displayed differentially by members of a structural ensemble at equilibrium. If this is true, antibody must be present during the prolonged incubations required to reveal time-dependent patterns of neutralization. An alternative model is that changes in the virus structure occurring with time are irreversible and do not reflect a reversible viral “breathing” process (40). To investigate this model, neutralization studies were performed using WNV-prM+, WNV-furin, and the panel of MAbs described above. RVPs were incubated for 30 h at 37°C in the absence of antibody, followed by the addition of serial dilutions of MAb approximately 1 h prior to infection of Raji-DCSIGNR cells. Experiments with both WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin demonstrated only modest (<2-fold) increases in neutralization potency compared to the reference condition (no prolonged incubation) run in parallel (Fig. 6, compare solid black to dashed red lines). Notably, this small increase in potency was nevertheless reproducible and significant for the majority of MAb-virus pairs (Table 1). In comparison, the same 30-h prolonged incubation in the presence of antibody resulted in large increases in neutralization activity, as expected (Fig. 6, compare solid black to dashed orange lines, and Table 1). The requirement for the presence of antibody during the prolonged incubations used to detect time-dependent changes in neutralization potency indicates that changes in the structure of infectious virions that contribute to neutralization sensitivity are reversible.

FIG 6.

Kinetic changes in patterns of WNV neutralization sensitivity following prolonged incubations in the presence and absence of antibody. WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin RVPs were incubated with serial dilutions of the indicated MAbs for 1 h at room temperature, followed by infection of Raji-DCSIGNR cells to generate reference neutralization curves (solid black lines). Additionally, RVP-antibody complexes were incubated for an additional 30 h at 37°C before infecting target cells (dashed orange lines) or RVPs were incubated alone for 29 h at 37°C, followed by the addition of serial dilutions of antibody for a 1-h incubation prior to infection of target cells (dashed red lines). Infectivity was assessed 48 h postinfection by flow cytometry. The results from a representative experiment are displayed relative to the infectivity in the absence of antibody at each individual time point. The error bars display the range of duplicate or triplicate infections. The results are representative of four to six independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

Changes in neutralization potency against WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin after prolonged incubation in the presence or absence of antibody

| Incubation | WNV-prM+ |

WNV-furin |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAb | Fold decrease in infectivity/EC50a | P valueb | MAb | Fold decrease in infectivity/EC50a | P valueb | |

| 30 h + Ab | E16 | 6.06 | 0.013 | E16 | 6.89 | 0.017 |

| E22 | 6.24 | 0.002 | E22 | 3.72 | <0.001 | |

| E33 | 3.23 | 0.044 | E33 | 6.85 | 0.016 | |

| E48 | 26.08 | <0.001 | E48 | 4.20 | <0.001 | |

| E60 | 134.38 | 0.001 | E60 | 21.47 | 0.003 | |

| E121 | 38.12 | 0.002 | E121 | 12.82 | 0.003 | |

| 30 h − Ab | E16 | 1.34 | 0.042 | E16 | 1.29 | 0.019 |

| E22 | 1.21 | 0.042 | E22 | 1.20 | 0.022 | |

| E33 | 1.90 | 0.056 | E33 | 1.89 | 0.032 | |

| E48 | 1.35 | 0.095 | E48 | 1.18 | 0.006 | |

| E60 | 1.55 | 0.003 | E60 | 1.47 | 0.002 | |

| E121 | 1.22 | 0.041 | E121 | 1.41 | 0.011 | |

The fold decrease in neutralization potency compared to the reference neutralization curve is reported as the fold change in EC50 (E16 or E33) or, for MAbs for which the EC50 could not be calculated with confidence (E22, E48, E60, and E121), the fold change in infectivity at the peak antibody concentration evaluated. The results are the average of four to six individual experiments.

P values were determined using Student's t test.

Structural dynamic characteristics of DENV-prM+ and DENV-furin are also distinct.

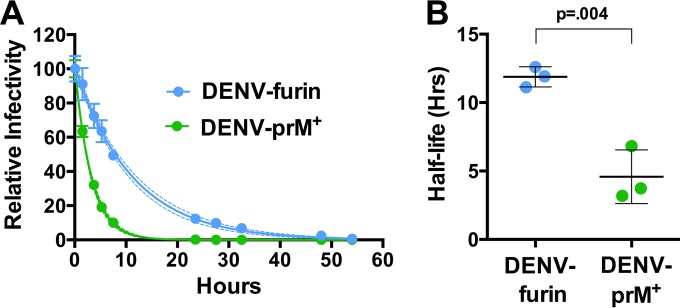

To extend our conclusions to other flaviviruses, we performed analogous studies with DENV RVPs. Populations of DENV RVPs that differ significantly with respect to the efficiency of virion maturation were produced using the structural proteins of the DENV2 strain 16681. In agreement with experiments with WNV, analysis of the intrinsic decay revealed that DENV-prM+ decays at a higher rate than DENV-furin (∼2.8-fold difference; average, 4.58- versus 11.88-h half-life, respectively; P = 0.004) (Fig. 7). Overall, the intrinsic decay of DENV infectivity in solution was considerably more rapid than that of WNV.

FIG 7.

Intrinsic decay of DENV-prM+ and DENV-furin infectivity. (A) Populations of DENV-prM+ and DENV-furin RVPs expressing the structural proteins of serotype 2 strain 16681 were equilibrated to 37°C, after which samples were harvested and frozen at the indicated times. The infectivity at each point was determined by infection of Raji-DCSIGNR cells and monitored by flow cytometry 48 h postinfection. The data are normalized to the infectivity of RVPs at the initial time point (after the 1-h 37°C preincubation) and fitted to a single-phase exponential-decay curve to obtain the half-life. For the representative experiment shown, the dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals of the regression analysis, and the error bars represent the standard errors of triplicate measurements. (B) The results of three individual experiments, each performed in triplicate, are summarized. The error bars represent the standard errors, and the horizontal lines show the means of all experiments. The P value was determined using Student's t test.

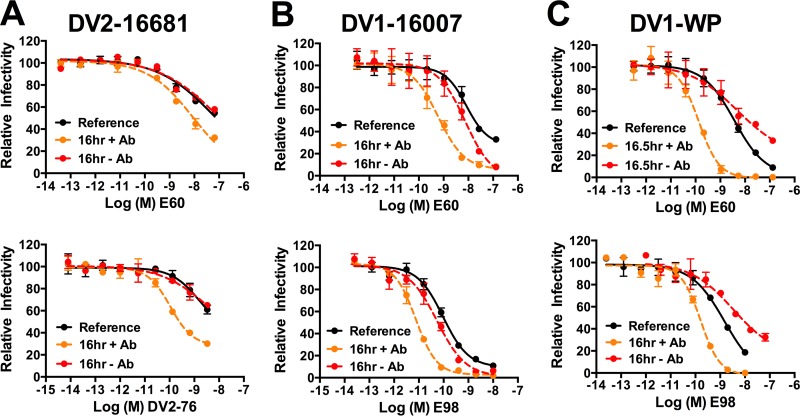

Unfortunately, the low infectivity of DENV-prM+ preparations, combined with a relatively rapid intrinsic decay, inhibited our ability to perform rigorous time-dependent neutralization studies. Thus, we were unable to compare patterns of neutralization against DENV-furin and DENV-prM+ in this setting. Similar to what was observed for WNV (Fig. 6), time-dependent increases in neutralization were observed when DENV-furin RVPs were incubated in the presence of antibody for an extended period. A 16-h incubation of mature preparations of DENV2 16681 with the E-DII fusion loop-reactive MAb E60 and the E-DIII type-specific MAb DV2-76 resulted in increased neutralization activity compared to the reference condition (Fig. 8A, compare the dashed orange line to the solid black line). Analogous results were obtained with RVPs produced using the structural genes of the DENV1 strains 16007 (Fig. 8B) and WP (Fig. 8C) and incubated with E60 or the DENV1 E-DIII type-specific MAb E98. Unexpectedly, we observed varied results when DENV-furin was incubated for 16 h in the absence of antibody. Compared to the reference neutralization profile, we observed either no change (strain 16681) or a modest increase in neutralization sensitivity (strain 16007) when the prolonged incubation was performed in the absence of antibody, similar to our results with WNV. Curiously, experiments with DENV1 WP revealed a reproducible decrease in neutralization sensitivity following this incubation (Fig. 8, compare the dashed red lines to the solid black lines). While the biological significance of this difference remains to be established, these results further support the hypothesis that strain-dependent differences in viral “breathing” exist, as first noted in studies of the sensitivities of these two DENV1 strains to neutralization by the type-specific MAb E111 (22). Overall, our results with DENV provide further evidence of a role for structural dynamics in regulating antibody recognition and neutralization of flaviviruses and highlight potential variation between different serotypes and strains of DENV.

FIG 8.

Kinetic changes in patterns of DENV-furin neutralization sensitivity following prolonged incubations in the presence and absence of antibody. DENV-furin RVPs representing virus strains (A) DENV2 16681, (B) DENV1 16007, and (C) DENV1 WP were incubated with serial dilutions of the indicated MAbs for 1 h at 37°C, followed by infection of Raji-DCSIGNR cells to generate reference neutralization curves (solid black lines). Additionally, RVP-antibody complexes were incubated for an additional 16 h at 37°C before infecting target cells (dashed orange lines) or RVPs were incubated alone for 15 h at 37°C, followed by addition of serial dilutions of antibody 1 h prior to infection of target cells (dashed red lines). Infectivity was assessed 48 h postinfection by flow cytometry. The results from a representative experiment are displayed relative to the infectivity in the absence of antibody at each individual time point. The error bars display the range of duplicate infections. The results are representative of two independent experiments. DENV-furin: DV2-16681, DENV serotype 2 strain 16681; DV1-16007, DENV serotype 1 strain 16007; DV1-WP, DENV serotype 1 strain Western Pacific-74. MAbs: E60, WNV-specific MAb that binds an epitope near the E-DII fusion loop and is cross-reactive for DENV; DV2-76, DENV serotype 2-specific MAb that binds E-DIII; E98, DENV serotype 1-specific MAb that binds E-DIII.

DISCUSSION

High-resolution structures of virus particles, revealed using X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), provide unique and valuable insights into the biology of viruses. One limitation of these techniques is that they generally capture a single prevalent state of the virion under defined experimental conditions. Viruses likely exist as an ensemble of conformations at equilibrium. This dynamic process has been referred to as viral “breathing” and may be an essential aspect of the life cycle of many viruses (33). For example, limited proteolysis studies of Flock House virus and human rhinovirus 14 (HRV14) identified portions of internal capsid proteins exposed transiently to the exterior of the particle (44, 45). Of interest, the potent antiviral compound WIN 52084, which binds under a canyon at the 5-fold symmetry axis of the HRV14 virion, functions in part by stabilizing an otherwise dynamic capsid structure (45, 46).

Studies with antibodies have played a critical role in the identification of unexpected virion structures arising from viral “breathing.” Early studies with the influenza virus-specific MAb Y8-10C2 revealed a striking temperature dependence of hemagglutination-inhibition activity; maximum inhibition with this MAb required incubation of virus with antibody for more than 15 h (47). This MAb was mapped to an inaccessible epitope buried within the interface of the hemagglutinin (HA) trimer. Similarly, antibodies specific for the HRV14 VP4 protein neutralize infection when incubated with the virus at 37°C, but not room temperature (48). Temperature-dependent changes in epitope accessibility have also been reported for flaviviruses (22, 28). For example, the DENV E-specific MAb 1A1D-2 maps to an epitope partially occluded from antibody binding in all three E protein symmetry environments, consistent with an inability of the MAb to bind the mature virion at 4°C. However, incubation at 37°C allows 1A1D-2 binding and is associated with a structural rearrangement of E proteins, as determined by cryo-EM (31).

How antibodies bind cryptic (nonaccessible) epitopes on flavivirus virions has been clarified by several recent findings. First, the structural heterogeneity of flaviviruses arising from incomplete prM cleavage impacts recognition by many antibodies (11). Partially mature flaviviruses are prM-containing virus particles characterized by structural features of both mature and immature virus particles. The structures and proportions of partially mature virions produced in vitro and in vivo are incompletely understood (23), as is the role of this heterogeneous group of virions in pathogenesis. The proportion of partially mature virions released from cells has the potential to vary considerably among cell types (30, 49), at different times after infection, and due to factors that modulate the level of furin expression (50). At present, the stoichiometric requirements of prM cleavage for the production of infectious virus are unknown. The process of virion maturation decreases sensitivity to neutralization, as many antibodies are incapable of binding the mature virion with a stoichiometry sufficient to exceed the critical number required for neutralization (18, 23, 24). Of the WNV-specific MAbs characterized to date, the majority are maturation state sensitive.

In addition, the structural dynamics, or “breathing,” of E proteins on flaviviruses increases neutralization sensitivity by modulating exposure of poorly accessible epitopes. Time- and temperature-dependent patterns of neutralization are a common characteristic of anti-flavivirus antibodies (22, 28, 30, 51). In the present study, we investigated the interplay between flavivirus virion maturation and viral “breathing.” We hypothesized that the differences in virion structure required to accommodate uncleaved prM on the virus particle may shape the ensemble of conformations sampled via structural dynamics, or viral “breathing.” To address this question, we employed a panel of WNV E-specific MAbs to assess differences in time-dependent neutralization of WNV-prM+ and WNV-furin. Our analysis focused on neutralization profiles generated after extended incubation at 37°C (the kinetic limit), when the extent of MAb neutralization was shown experimentally to be insensitive to further incubation. At the kinetic limit, MAbs that bound the solvent-accessible DIII-LR epitope (E16 and E33) neutralized WNV equivalently irrespective of the prM content of the virion. In comparison, maturation state-dependent MAbs that bind epitopes predicted to be poorly exposed on the mature virion revealed differences in the sensitivities of WNV-furin and WNV-prM+ RVPs. These results suggest that the presence of prM alters the manner in which these epitopes are displayed by the structural ensemble. Changes in the structural ensemble may contribute to increased neutralization potency via alterations in epitope accessibility with the potential to modulate the number of antibodies bound to the virion and antibody-virion affinity, as well as the introduction of bivalent modes of recognition.

Our results also have implications for the structure of a heterogeneous and dynamic virion. The first high-resolution structure of DENV revealed a relatively smooth virus particle on which the E protein was arranged in a dense pseudoicosahedral fashion (10). Two recent studies report the structure of DENV2 exposed to 37°C (52, 53). Of interest, these studies reveal a markedly different, “bumpy” structure at physiological temperature due to a reorientation of the E proteins so that domain II moves away from the membrane. This temperature-dependent change in structure was hypothesized to alter epitope accessibility. It has been suggested that the transition from the smooth to the bumpy form of the virion is rapid and irreversible and represents a step down a pathway that leads to the triggering of the viral fusion machinery (53). Our data suggest that the formation of a bumpy conformation is not sufficient to explain the interaction of viruses with antibody. First, changes in neutralization sensitivity occur over longer intervals than the very rapid transition (30 min of incubation at 37°C) captured by these two structural studies. Second, prolonged incubation of virions in the absence of antibody does not markedly change their sensitivity to neutralization. Our results suggest that even the “bumpy” structure undergoes reversible conformational changes that have the potential to increase epitope accessibility. Of note, DENV serotypes 1 and 4 were not observed to adopt a “bumpy” conformation at 37°C, indicating variability among strains (54). Furthermore, although cryo-EM constructions of immature DENV incubated at room temperature and 37°C are similar (53), our studies demonstrate that preparations of virions that retain significant levels of uncleaved prM also sample an ensemble of conformations with the potential to alter neutralization sensitivity. The structural basis of the structural ensembles sampled by virions with and without prM remains unclear and will undoubtedly be difficult to resolve due to the significant heterogeneity of flaviviruses and the presence of both infectious and noninfectious forms of the virion (in changing proportions).

Increasing the length of virus incubation is associated with a gradual decrease in infectivity, referred to here as intrinsic decay. To explain this phenomenon, we hypothesize that a subset of dynamics-mediated structural changes are irreversible and result in noninfectious structures on which the E proteins are no longer capable of mediating fusion. A similar phenomenon has been described for the nonenveloped coxsackievirus B3. The altered particle, or “A particle,” represents a noninfectious structure that can no longer bind the cellular receptor; this transition can occur spontaneously in solution, presumably due to virus “breathing” (40). The rates at which these noninfectious virions are formed may differ among structural ensembles of virions. We observed distinct infectivity decay rates in comparisons of WNV and DENV and for each virus when the maturation state was altered. We further demonstrate that in the subset of virions that maintain infectious potential, structural changes associated with virus “breathing” may be reversible (Fig. 6 and 8). The use of neutralization assays that report the biology of only infectious virions provides a functional probe for the way in which the antigenic surface of infectious virions changes with time. These approaches should be of significant utility in studies designed to probe the viral determinants that govern the dynamics of the virus particle, which appear to vary among virus types (28, 54) and even viral strains (22). One intriguing hypothesis is that the contribution of interactions that form the mature virion (e.g., the dimer interface) may differ among viruses (55) or may be impacted by variation within a virus population. The difference in oligomeric structure of the E proteins on partially mature virions would certainly alter these interactions further. Structural methods, while important, lack the ability to differentiate between infectious and noninfectious populations and should be complemented by experiments that probe the biology of the virion.

Our results highlight the existence of a complex interplay between antibody specificity, virion structural heterogeneity, and virus “breathing.” The recent failure of a phase 2b tetravalent DENV vaccine emphasizes the need for enhanced understanding of the details of antibody recognition and the characteristics associated with an effective immune response (56). Our findings highlight differences in how antibodies interact with flaviviruses that represent different strains or maturation states. Future studies of how virus “breathing” and structural heterogeneity impact antibody recognition will guide our understanding of natural infection and vaccination.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 July 2014

REFERENCES

- 1. Artsob H, Gubler DJ, Enria DA, Morales MA, Pupo M, Bunning ML, Dudley JP. 2009. West Nile Virus in the New World: trends in the spread and proliferation of West Nile Virus in the Western Hemisphere. Zoonoses Public Health 56:357–369. 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2008.01207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. West Nile virus and other arboviral diseases—United States, 2012. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 62:513–517 http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6225a1.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Sankoh O, Myers MF, George DB, Jaenisch T, Wint GR, Simmons CP, Scott TW, Farrar JJ, Hay SI. 2013. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496:504–507. 10.1038/nature12060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gubler DJ. 2012. The economic burden of dengue. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 86:743–744. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Halstead SB. 2007. Dengue. Lancet 370:1644–1652. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61687-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang Y, Kaufmann B, Chipman PR, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2007. Structure of immature West Nile virus. J. Virol. 81:6141–6145. 10.1128/JVI.00037-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang Y, Corver J, Chipman PR, Zhang W, Pletnev SV, Sedlak D, Baker TS, Strauss JH, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2003. Structures of immature flavivirus particles. EMBO J. 22:2604–2613. 10.1093/emboj/cdg270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yu IM, Zhang W, Holdaway HA, Li L, Kostyuchenko VA, Chipman PR, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG, Chen J. 2008. Structure of the immature dengue virus at low pH primes proteolytic maturation. Science 319:1834–1837. 10.1126/science.1153264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mukhopadhyay S, Kim BS, Chipman PR, Rossmann MG, Kuhn RJ. 2003. Structure of West Nile virus. Science 302:248. 10.1126/science.1089316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuhn RJ, Zhang W, Rossmann MG, Pletnev SV, Corver J, Lenches E, Jones CT, Mukhopadhyay S, Chipman PR, Strauss EG, Baker TS, Strauss JH. 2002. Structure of dengue virus: implications for flavivirus organization, maturation, and fusion. Cell 108:717–725. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00660-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pierson TC, Diamond MS. 2012. Degrees of maturity: the complex structure and biology of flaviviruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2:168–175. 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Whitehead SS, Blaney JE, Durbin AP, Murphy BR. 2007. Prospects for a dengue virus vaccine. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:518–528. 10.1038/nrmicro1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Crill WD, Roehrig JT. 2001. Monoclonal antibodies that bind to domain III of dengue virus E glycoprotein are the most efficient blockers of virus adsorption to Vero cells. J. Virol. 75:7769–7773. 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7769-7773.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Calvert AE, Kalantarov GF, Chang GJ, Trakht I, Blair CD, Roehrig JT. 2011. Human monoclonal antibodies to West Nile virus identify epitopes on the prM protein. Virology 410:30–37. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dejnirattisai W, Jumnainsong A, Onsirisakul N, Fitton P, Vasanawathana S, Limpitikul W, Puttikhunt C, Edwards C, Duangchinda T, Supasa S, Chawansuntati K, Malasit P, Mongkolsapaya J, Screaton G. 2010. Cross-reacting antibodies enhance dengue virus infection in humans. Science 328:745–748. 10.1126/science.1185181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Della-Porta AJ, Westaway EG. 1978. A multi-hit model for the neutralization of animal viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 38:1–19. 10.1099/0022-1317-38-1-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dowd KA, Pierson TC. 2011. Antibody-mediated neutralization of flaviviruses: a reductionist view. Virology 411:306–315. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pierson TC, Xu Q, Nelson S, Oliphant T, Nybakken GE, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. 2007. The stoichiometry of antibody-mediated neutralization and enhancement of West Nile virus infection. Cell Host Microbe 1:135–145. 10.1016/j.chom.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaufmann B, Nybakken GE, Chipman PR, Zhang W, Diamond MS, Fremont DH, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2006. West Nile virus in complex with the Fab fragment of a neutralizing monoclonal antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:12400–12404. 10.1073/pnas.0603488103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nybakken GE, Oliphant T, Johnson S, Burke S, Diamond MS, Fremont DH. 2005. Structural basis of West Nile virus neutralization by a therapeutic antibody. Nature 437:764–769. 10.1038/nature03956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stiasny K, Kiermayr S, Holzmann H, Heinz FX. 2006. Cryptic properties of a cluster of dominant flavivirus cross-reactive antigenic sites. J. Virol. 80:9557–9568. 10.1128/JVI.00080-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Austin SK, Dowd KA, Shrestha B, Nelson CA, Edeling MA, Johnson S, Pierson TC, Diamond MS, Fremont DH. 2012. Structural basis of differential neutralization of DENV-1 genotypes by an antibody that recognizes a cryptic epitope. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002930. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cherrier MV, Kaufmann B, Nybakken GE, Lok SM, Warren JT, Chen BR, Nelson CA, Kostyuchenko VA, Holdaway HA, Chipman PR, Kuhn RJ, Diamond MS, Rossmann MG, Fremont DH. 2009. Structural basis for the preferential recognition of immature flaviviruses by a fusion-loop antibody. EMBO J. 28:3269–3276. 10.1038/emboj.2009.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nelson S, Jost CA, Xu Q, Ess J, Martin JE, Oliphant T, Whitehead SS, Durbin AP, Graham BS, Diamond MS, Pierson TC. 2008. Maturation of West Nile virus modulates sensitivity to antibody-mediated neutralization. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000060. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gould LH, Sui J, Foellmer H, Oliphant T, Wang T, Ledizet M, Murakami A, Noonan K, Lambeth C, Kar K, Anderson JF, de Silva AM, Diamond MS, Koski RA, Marasco WA, Fikrig E. 2005. Protective and therapeutic capacity of human single-chain Fv-Fc fusion proteins against West Nile virus. J. Virol. 79:14606–14613. 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14606-14613.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oliphant T, Nybakken GE, Austin SK, Xu Q, Bramson J, Loeb M, Throsby M, Fremont DH, Pierson TC, Diamond MS. 2007. Induction of epitope-specific neutralizing antibodies against West Nile virus. J. Virol. 81:11828–11839. 10.1128/JVI.00643-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Throsby M, Geuijen C, Goudsmit J, Bakker AQ, Korimbocus J, Kramer RA, Clijsters-van der Horst M, de Jong M, Jongeneelen M, Thijsse S, Smit R, Visser TJ, Bijl N, Marissen WE, Loeb M, Kelvin DJ, Preiser W, ter Meulen J, de Kruif J. 2006. Isolation and characterization of human monoclonal antibodies from individuals infected with West Nile virus. J. Virol. 80:6982–6992. 10.1128/JVI.00551-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dowd KA, Jost CA, Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, Pierson TC. 2011. A dynamic landscape for antibody binding modulates antibody-mediated neutralization of West Nile virus. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002111. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mukherjee S, Lin TY, Dowd KA, Manhart CJ, Pierson TC. 2011. The infectivity of prM-containing partially mature West Nile virus does not require the activity of cellular furin-like proteases. J. Virol. 85:12067–12072. 10.1128/JVI.05559-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vogt MR, Dowd KA, Engle M, Tesh RB, Johnson S, Pierson TC, Diamond MS. 2011. Poorly neutralizing cross-reactive antibodies against the fusion loop of West Nile virus envelope protein protect in vivo via Fcgamma receptor and complement-dependent effector mechanisms. J. Virol. 85:11567–11580. 10.1128/JVI.05859-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lok SM, Kostyuchenko V, Nybakken GE, Holdaway HA, Battisti AJ, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Sedlak D, Fremont DH, Chipman PR, Roehrig JT, Diamond MS, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. 2008. Binding of a neutralizing antibody to dengue virus alters the arrangement of surface glycoproteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15:312–317. 10.1038/nsmb.1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rey FA. 2013. Dengue virus: two hosts, two structures. Nature 497:443–444. 10.1038/497443a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Witz J, Brown F. 2001. Structural dynamics, an intrinsic property of viral capsids. Arch. Virol. 146:2263–2274. 10.1007/s007050170001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li Q, Yafal AG, Lee YM, Hogle J, Chow M. 1994. Poliovirus neutralization by antibodies to internal epitopes of VP4 and VP1 results from reversible exposure of these sequences at physiological temperature. J. Virol. 68:3965–3970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ansarah-Sobrinho C, Nelson S, Jost CA, Whitehead SS, Pierson TC. 2008. Temperature-dependent production of pseudoinfectious dengue reporter virus particles by complementation. Virology 381:67-74. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pierson TC, Sanchez MD, Puffer BA, Ahmed AA, Geiss BJ, Valentine LE, Altamura LA, Diamond MS, Doms RW. 2006. A rapid and quantitative assay for measuring antibody-mediated neutralization of West Nile virus infection. Virology 346:53–65. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Davis CW, Nguyen HY, Hanna SL, Sanchez MD, Doms RW, Pierson TC. 2006. West Nile virus discriminates between DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR for cellular attachment and infection. J. Virol. 80:1290–1301. 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1290-1301.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Randolph VB, Winkler G, Stollar V. 1990. Acidotropic amines inhibit proteolytic processing of flavivirus prM protein. Virology 174:450–458. 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90099-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mukherjee S, Dowd KA, Manhart CJ, Ledgerwood JE, Durbin AP, Whitehead SS, Pierson TC. 2014. Mechanism and significance of cell type-dependent neutralization of flaviviruses. J. Virol. 88:7210–7220. 10.1128/JVI.03690-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Organtini LJ, Makhov AM, Conway JF, Hafenstein S, Carson SD. 2014. Kinetic and structural analysis of coxsackievirus B3 receptor interactions and formation of the A-particle. J. Virol. 88:5755–5765. 10.1128/JVI.00299-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee PD, Mukherjee S, Edeling MA, Dowd KA, Austin SK, Manhart CJ, Diamond MS, Fremont DH, Pierson TC. 2013. The Fc region of an antibody impacts the neutralization of West Nile viruses in different maturation states. J. Virol. 87:13729–13740. 10.1128/JVI.02340-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oliphant T, Engle M, Nybakken GE, Doane C, Johnson S, Huang L, Gorlatov S, Mehlhop E, Marri A, Chung KM, Ebel GD, Kramer LD, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. 2005. Development of a humanized monoclonal antibody with therapeutic potential against West Nile virus. Nat. Med. 11:522–530. 10.1038/nm1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oliphant T, Nybakken GE, Engle M, Xu Q, Nelson CA, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Marri A, Lachmi BE, Olshevsky U, Fremont DH, Pierson TC, Diamond MS. 2006. Antibody recognition and neutralization determinants on domains I and II of West Nile Virus envelope protein. J. Virol. 80:12149–12159. 10.1128/JVI.01732-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bothner B, Dong XF, Bibbs L, Johnson JE, Siuzdak G. 1998. Evidence of viral capsid dynamics using limited proteolysis and mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 273:673–676. 10.1074/jbc.273.2.673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lewis JK, Bothner B, Smith TJ, Siuzdak G. 1998. Antiviral agent blocks breathing of the common cold virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:6774–6778. 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roy A, Post CB. 2012. Long-distance correlations of rhinovirus capsid dynamics contribute to uncoating and antiviral activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:5271–5276. 10.1073/pnas.1119174109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yewdell JW, Taylor A, Yellen A, Caton A, Gerhard W, Bachi T. 1993. Mutations in or near the fusion peptide of the influenza virus hemagglutinin affect an antigenic site in the globular region. J. Virol. 67:933–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Katpally U, Fu TM, Freed DC, Casimiro DR, Smith TJ. 2009. Antibodies to the buried N terminus of rhinovirus VP4 exhibit cross-serotypic neutralization. J. Virol. 83:7040–7048. 10.1128/JVI.00557-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Murray JM, Aaskov JG, Wright PJ. 1993. Processing of the dengue virus type 2 proteins prM and C-prM. J. Gen. Virol. 74:175–182. 10.1099/0022-1317-74-2-175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lei RX, Shi H, Peng XM, Zhu YH, Cheng J, Chen GH. 2009. Influence of a single nucleotide polymorphism in the P1 promoter of the furin gene on transcription activity and hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology 50:763–771. 10.1002/hep.23062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sabo MC, Luca VC, Ray SC, Bukh J, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. 2012. Hepatitis C virus epitope exposure and neutralization by antibodies is affected by time and temperature. Virology 422:174–184. 10.1016/j.virol.2011.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fibriansah G, Ng TS, Kostyuchenko VA, Lee J, Lee S, Wang J, Lok SM. 2013. Structural changes in dengue virus when exposed to a temperature of 37°C. J. Virol. 87:7585–7592. 10.1128/JVI.00757-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang X, Sheng J, Plevka P, Kuhn RJ, Diamond MS, Rossmann MG. 2013. Dengue structure differs at the temperatures of its human and mosquito hosts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:6795–6799. 10.1073/pnas.1304300110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kostyuchenko VA, Chew PL, Ng TS, Lok SM. 2014. Near-atomic resolution cryo-electron microscopic structure of dengue serotype 4 virus. J. Virol. 88:477–482. 10.1128/JVI.02641-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Luca VC, AbiMansour J, Nelson CA, Fremont DH. 2012. Crystal structure of the Japanese encephalitis virus envelope protein. J. Virol. 86:2337–2346. 10.1128/JVI.06072-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sabchareon A, Wallace D, Sirivichayakul C, Limkittikul K, Chanthavanich P, Suvannadabba S, Jiwariyavej V, Dulyachai W, Pengsaa K, Wartel TA, Moureau A, Saville M, Bouckenooghe A, Viviani S, Tornieporth NG, Lang J. 2012. Protective efficacy of the recombinant, live-attenuated, CYD tetravalent dengue vaccine in Thai schoolchildren: a randomised, controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet 380:1559–1567. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61428-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]