Summary

This study includes 20 patients with 21 spinal perimedullary fistulae. There were nine Type IVa (42.8%) lesions, ten Type IVb (47.6%) and two Type IVc (9.5%) lesions. The dominant arterial supply was from the anterior spinal artery (47.6%), posterior spinal artery (19%) and directly from the radiculomedullary artery (28.5%). Sixteen lesions in 15 patients were treated by endovascular route using n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. Endovascular treatment was not feasible in five patients. Of the ten patients with microfistulae, catheterization failed/was not attempted in 40%, complete obliteration of the lesion was seen in 60% but clinical improvement was seen in 40% of patients. Catheterization was feasible in all ten patients with macrofistulae (nine type IVb and two type IVc lesions). Complete obliteration of the lesions was seen in 60% and residue in 30%. Clinical improvement was seen in 80% and clinical deterioration in 10%. In conclusion, endovascular glue embolization is safe and efficacious in type IVb and IVc spinal perimedullary fistulae and should be considered the first option of treatment. It is also feasible in many of the type IVa lesions.

Keywords: perimedullary arteriovenous fistula, spinal cord, embolization

Introduction

Perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas (PMAVFs) of the spinal cord are intradural vascular malformations located either on the surface of the cord or just under the pia and consist of a direct arteriovenous fistula without an intervening nidus 1. PMAVFs constitute 8-19% of spinal vascular malformations and are predominantly found in the thoracolumbar region, either on the anterior, lateral or posterior surface of the cord 2. The arterial supply usually comes from the anterior spinal arteries (ASA), and less commonly from a posterior spinal artery (PSA) 3. This type was first described by Djindjian et al. 4 in 1977, and subsequently classified as type IV spinal arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) by Heros et al. 5. According to the generally accepted Anson and Spetzler classification, three subtypes are identified according to shunt flow and degree of vascular enlargement. In type IVa PMAVF, there is a slow-flow single shunt between a non-dilated anterior or posterolateral spinal artery and a spinal vein. Type IVb lesions show greater flow than in type IVa and an ampullary dilatation of the venous side of the shunt. Increased shunt flow causes dilated tortuous intradural veins. PMAVFs generally have more than one feeder, usually a dilated anterior spinal artery and one or two posterior spinal arteries. Type IVc PMAVFs, called giant perimedullary AVFs, have multiple high-flow dilated feeding arteries and gross dilatation of draining veins; varices or true venous aneurysms are encountered either near the shunt or more distally 6. Sometimes there is difficulty in accurate labelling type IVa and IVb lesions. A revised classification by Rodesch et al. 1 simplifies the task and separates PMAVFs into macro-AVF and micro-AVF. Macro-AVFs are high-flow direct shunts fed by one or more spinal cord arteries ending in a venous ectasia with secondary perimedullary venous drainage. Micro-AVFs are small lesions fed by one or more slightly enlarged arteries draining into veins that are not ectatic 1. Few reports of PMAVFs have appeared in the literature. The treatment strategy has evolved since the report of Mourier et al. 7, but is still not uniformly practised. Several authors consider that endovascular treatment stabilizes or improves neurological symptoms in these patients at long-term follow-up 1. We studied 20 patients with type IV perimedullary spinal arteriovenous malformations. Of these, 15 patients were treated by endovascular route using n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA). We document our observations and impressions as regards the angio-architecture, classification and glue embolization in the light of available literature.

Patients and Methods

Medical records of 20 patients with 21 PMAVFs managed at our institution between 2002 and March 2013 were studied. Pertinent patient information is summarized in Table I. Eleven patients were male and nine were female, with an age range of two to 52 years (mean age, 28 years). Four PMAVFs were diagnosed and treated in the paediatric population (<15 years of age, in one patient two fistulae were seen). None of them had a history of trauma or spinal surgery. There was no family history in any of the patients. Clinically, 15 patients presented with slowly progressive motor weakness of both lower limbs. Rapidly progressive deficit with paraplegia was seen in two patients and monoparesis involving a lower limb in three patients. Additional features were paraesthesia (five patients), backache and bowel/bladder incontinence (three patients). In one patient a large epidermal vascular naevus was seen in the neck region.

Table 1.

Summary of treated patients with PMAVFs.

| No | demo | Clinical |

Aminoff Logue scale |

Site& subtype AVF |

Micro/ Macro* |

Segmental artery supply |

Feeders from |

Occlusion success |

Result after 3 months** (mRS)*** |

| 1 | 45 F | Backache& paraparesis | G3M0B0 | Conus IVb | Macro | Rt L4& Lt D11 | RMA ASA |

Small residue | Improved (2) |

| 2 | 8 M | Paraparesis | G2M0B1 | Dorsal IVb | Macro | Rt D6& Rt D10 | ASA | Complete | Improved (1) |

| 3 | 5 F | Paraparesis | G3M0B0 | Dorsal IVb &c multiple |

Macro | Lt D4 ---- Rt D5 ---- |

PSA ASA |

Complete | Complication- paraplegia deterioration (4) |

| 4 | 2 F | Paraparesis | − | Dorsal IVb | Macro | Rt D8 | RMA | Complete | Good Improvement (1) |

| 5 | 16 M | Monoparesis of RLL | G3M0B1 | Dorsal IVb | Macro | Lt D7, D12& L1 | ASA PSA |

Complete | Improved residual spasticity (2) |

| 6 | 36 M | Backache& lt monoparesis |

G3M0B0 | Lumbar IVb | Macro | Lt D10 | ASA | Small residue | Improved (2) |

| 7 | 23 M | Paraparesis & bld/bw incont |

G3M2B1 | Lumbar IVa | Micro | Lt L2 | RMA | Complete | Complete recovery (0) |

| 8 | 36 F | Backache Paraparesis |

G3M0B0 | Dorsal IVa | Micro | Lt D12& Lt L1 | PSA | Complete | Improved (2) |

| 9 | 45 M | Paraplegia | G5M3B2 | Cervical IVa | Micro | Rt thyrocervical | ASA | Complete | No improvement (4) |

| 10 | 36 F | Paraparesis | G3M0B0 | Dorsal IVb | Macro | Rt vertebral D4 | PSA | Small residue | Improved (2) |

| 11 | 37 M | Paraparesis | G3M0B0 | Lumbar IVa Filum terminale |

Micro | L1 | ASA | Failed, Referred for surgery |

− |

| 12 | 52 M | Backache Paraparesis |

G3M0B0 | Cervical IVa | Micro | Rt vertebral, Rt thyrocervical recurrence |

ASA | Complete | Improved (2) |

| 13 | 24 F | LLL monoparesis, epidermal nevus |

G3M0B0 | Cervical IVb | Macro | Lt vertebral | RMA | Complete | Good improvement (1) |

| 14 | 46 F | Spastic paraparesis paraesthesia |

G4M1B1 | Lumbar IVa, conus lesion |

Micro | Lt D9 | ASA | Failed, Referred for surgery |

No improvement (4) |

| 15 | 35 M | Paraparesis paraesthesia, backache, urinary symptoms |

G3M2B1 | Dorsal IVb | Micro | Lt D10 | RMA + PSA, feeder aneurysm, branch to ASA |

Complete, (required 3 sittings) |

Improved Needs self urinary catheterization (1) |

| 16 | 15 M | Paraparesis | G2M2B1 | Lumbar IVa, conus lesion |

Micro | Lt L1 | ASA | Referred for surgery | − |

| 17 | 25 F | Mild paraparesis | G2M0B0 | Lower dorsal IVb |

Macro | D7 and D12 | PSA + ASA | Microcatheterization failed, treated surgically |

Improved (1) |

| 18 | 6 F | Paraparesis, incontinence | G4M2B1 | Lumbar IVc | Macro | Lt L1 and L2 | ASA + PSA | Complete | Improved (1), residual urinary incontinence |

| 19 | 32 M | Paraparesis | G2M1B1 | Conus lesion IVa | Micro | Lt D10 | ASA | Referred for surgery | − |

| 20 | 35 M | Paraparesis, incontinence | G4M3B2 | Lumbar L3/4 IVa | Micro | Lat sacral br. of Int Iliac | RMA | Complete | Same after 3 months (4) |

| * micro/macro = microfistula, macrofistula (Rodesch et al.) ** Improved& good improvement = 1, 2 or more points improvement of MRS grade respectively *** mRS = Modified Rankin Scale for disability. | |||||||||

The evidence of spinal vascular malformation was demonstrated on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in all patients. Nine lesions were located in the thoracic region and three in the cervical region. Of the nine lumbar lesions, four were around the conus medullaris and one was a tiny lesion anterior to the filum terminale at L4 level. MRI revealed flow voids over the surface of the cord in all. A partially thrombosed venous sac compressing the cord was seen in one patient with a type IVc lesion. Cord oedema was seen in most of the patients and focal cord widening in three patients. Apart from clinical follow-up in the treated patients, follow-up MRI was available to monitor residual lesions.

Pretreatment clinical status was defined by the Aminoff Logue scale. Clinical improvement was labelled with one point improvement and good clinical improvement was labelled with two or more points improvement on the mRS scale.

Results

In the 20 patients in our study, there were nine type IVa (35%) lesions, ten type IVb (55%) and two type IVc (10%) lesions. One patient had a type IVb and a type IVc lesion, both in the thoracic region (Table 1).

In our study group, ten patients had 11 macrofistulae and ten patients had micro-fistulae. Out of 11 macrofistulae, nine were type IVb and two were type IVc lesions; among ten micro-fistulae, nine were type IVa and one was a type IVb lesion.

The dominant arterial supply was from the ASA in ten lesions (47.6%), from the PSA in four lesions (19%) whereas one type IVc lesion was fed by enlarged anterior as well as posterior spinal arteries. Interestingly, the direct dominant supply from the radiculo-medullary branch (RMA) of the intercostal artery was seen in six lesions (28.5%), exclusively in two IVb and one IVa lesions. Many of the type IVb lesions showed minor supply from other arteries. A feeder vessel aneurysm on RMA was seen in two type IVb lesions. In one patient the RMA supplied a twig to the anterior spinal axis and then continued with fusiform ectasia to supply the lesion.

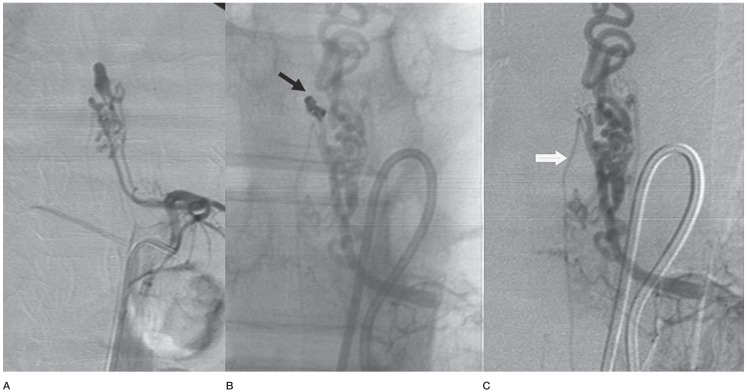

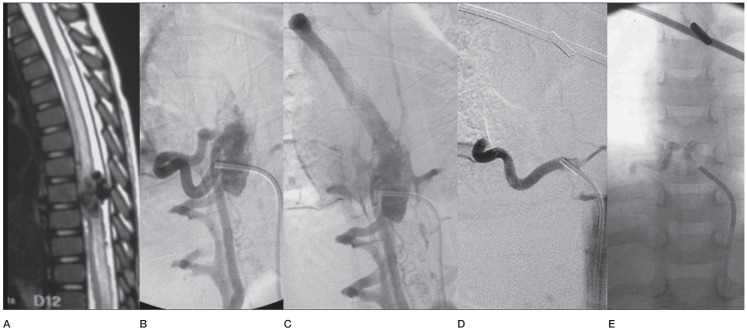

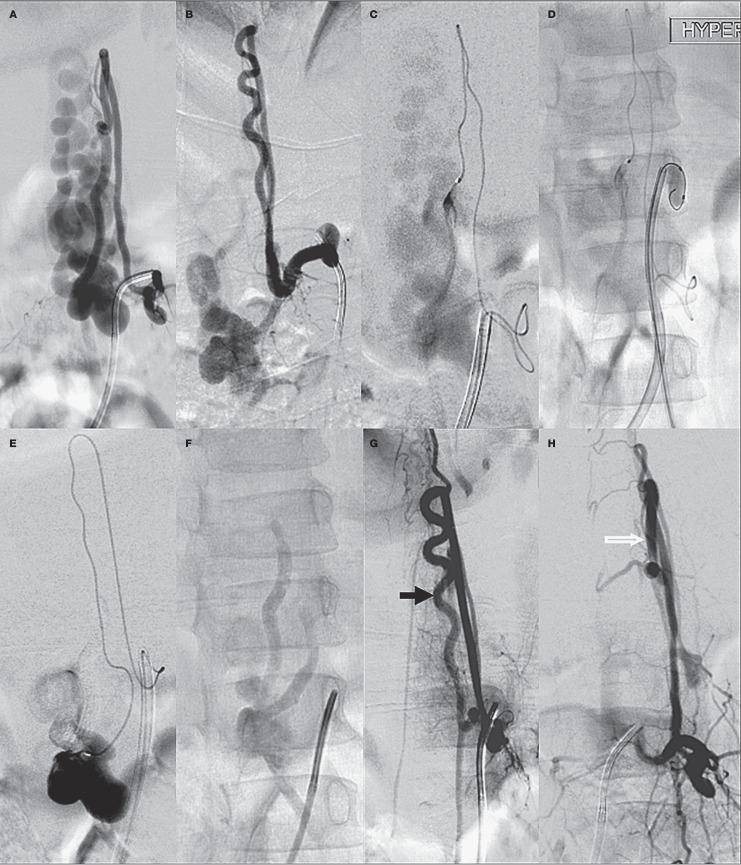

Embolization was attempted under general anaesthesia in 18 patients, but distal microcatheterization failed in three patients (two type IVa and one type IVb lesion) (Figure 1A,B). In the type IVb lesion with a failed endovascular attempt, we attended the surgical procedure to assist in interpreting and correlating imaging with surgical appearances. This helped in accurately localizing the fistula leading to a good clinical outcome. Two patients with a tiny conus lesion fed by ASA were directly referred for surgery due to anticipated difficulty of microcatheterization. One patient treated with surgery 20 years earlier for a cervical lesion fed by an ASA showed recurrence of symptoms after ten years. A small feeder from the thyrocervical artery was seen feeding the residual lesion which was embolized with glue (Figure 2A-E). Sixteen lesions in 15 patients were embolized with NBCA glue and lipiodol mixture delivered through a microcatheter (Tracker 10/Spinnaker 1.5 Boston Scientific, Ultraflow or Echelon or Marathon ev3, MTI, Irvine, CA, USA) after reaching close to the fistulous sites and were supported with a 0.008-inch guidewire (Mirage, ev3, MTI, Irvine, CA, USA) or Traxcess 14 more recently (Microvention). The concentration of glue/lipiodol mixture (33% to 66%) was modified as per flow situation. We used adjuvant techniques to facilitate the endovascular treatment. In one high-flow type IVc lesion we temporarily occluded the ASA feeder intercostal artery with a balloon while embolizing the PSA feeder along with systemic hypotension. In one patient aneurysmal ectasia of one of the feeder branches was protected with coiling (Figure 3A-C). A 5F angiographic RDC or MP curve (after exchange) catheter was used in most patients for access. In one patient an RDC curve 7F guiding catheter was required for support. Three sittings were required in one patient and two attempts were required in one patient. The mean follow-up period was 24 months and the patients were evaluated at three to six month intervals during the follow-up period. Two patients were lost to follow up after six months and one patient has a recent three months post-procedure follow-up.

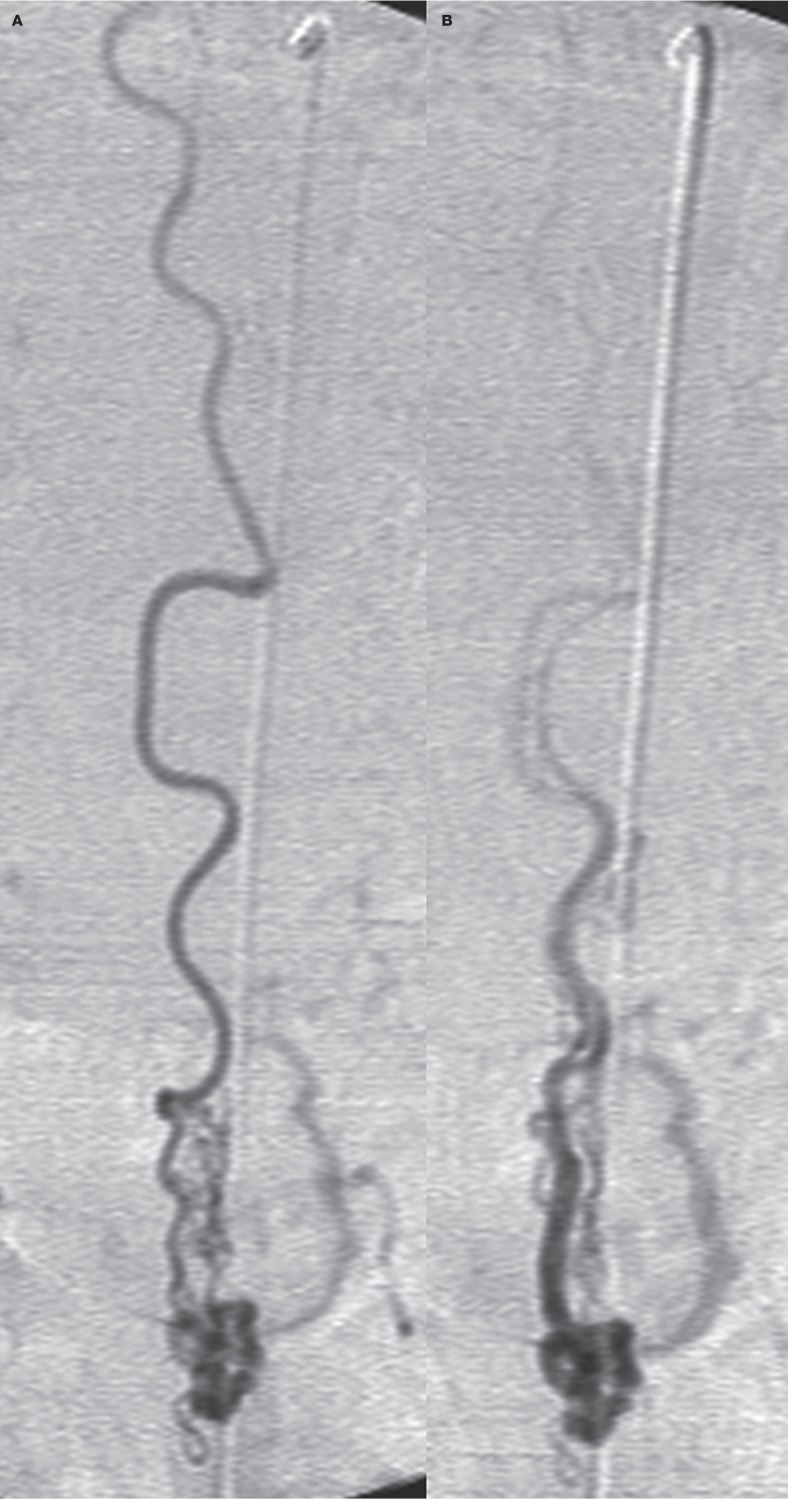

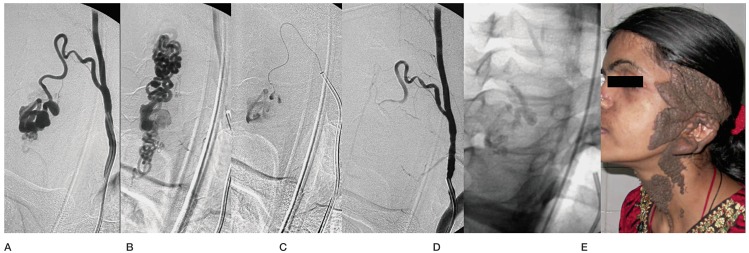

Figure 1.

A type IVa lesion of the conus region in a 46-year-old woman shows the long course of the anterior spinal artery feeding a small AVF (A) and the accompanying vein (B). Distal microcatheterization failed in this case.

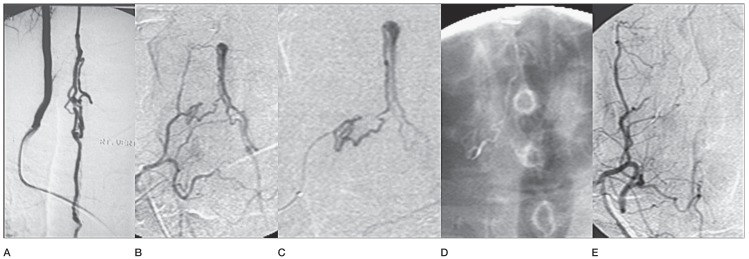

Figure 2.

A cervical type IVa lesion fed by the anterior spinal artery treated surgically 20 years earlier in a 52-year-old man. A) Rt vertebral angiography before surgery. B) Recurrence fed by Rt thyrocervical branch. C) The microcatheter tip is a little far from the fistula. D) Adequate glue cast reaching to the foot of the vein. E) Angiographic check in Rt thyrocervical trunk.

Figure 3.

Case No. 15. A radiculomedullary artery feeding a type IVb lesion shows an aneurysmal dilatation close to the lesion. A) It also sends a twig to the descending anterior spinal artery before the fusiform aneurysm. B) Also note a posterior spinal feeder arising from the same intercostal artery, the aneurysm was coiled (black arrow). C) Check angiography shows a residual AVF and descending anterior spinal artery. The lesion required two subsequent sessions to complete the obliteration.

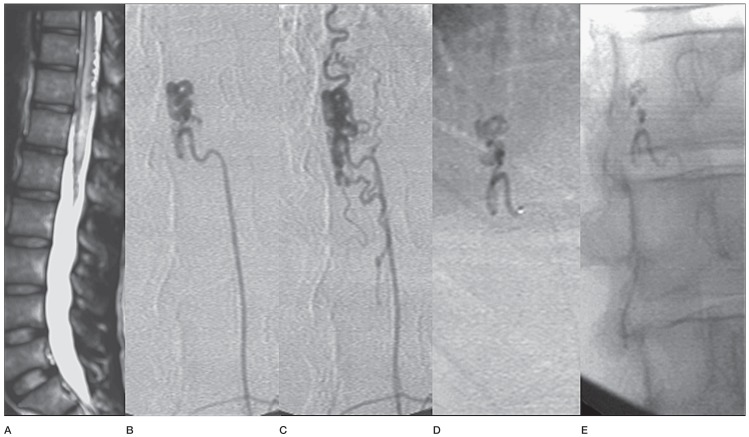

Results of NBCA glue embolization are summarized in Table 2. Of ten patients with micro-fistulae (nine type IVa lesions and one type IVb lesion), complete angiographic obliteration of the lesion was obtained in five (55.5%) type IVa lesions (Figure 4A-E) and one type IVb lesion, the latter requiring three sittings. Four of these patients (40%) showed good neurological improvement on follow-up. One patient with a cervical type IVa lesion fed by the thyrocervical branch showed no improvement in paraplegia despite a very precise embolic obliteration.

Table 2.

NBCA glue embolization in spinal PMAVFs.

|

Microfistulae (10; 9 IVa& 1 IVb type in 10 patients) |

Macrofistulae (11; 9 IVb& 2 IVc type, in 10 patients) |

|

| Number of patients | 10 | 10 |

|

Failed catheterization or not attempted |

4 (40%) | 1 (10%) |

|

Complete endovascular occlusion |

6 (60%) | 6 (60%) |

|

Partial endovascular occlusion |

– | 3 (30%) |

| Clinical improvement | 4 (40%) | 8 (80%) |

| No clinical improvement | 2 (20%) | – |

| Clinical deterioration | – | 1 (10%) |

Figure 4.

Case No. 7. A) MRI T2 weighted image in a 23-year-old man shows cord oedema and flow voids in the subarachnoid space in the thoracolumbar region. B) Left L2 injection shows ascending limb of RMA supplying a type IVa lesion. C) Venous phase. D) Microcatheter close to the fistula site. E) Precise glue cast taking the distal part of the feeder, the fistula and early part of the vein.

Of the 11 macrofistulae (nine type IVb lesions and two type IVc lesions in ten patients) attempted for endovascular glue embolization, six lesions showed total obliteration (60%) (Figures 5-7). Good clinical improvement was seen in five patients (50%). In one patient the poor outcome was related to a complication while treating the associated type IVc lesion. In three other patients there was a small angiographic residue after treatment. However clinical improvement was seen. These patients are on follow-up and we have not aggressively pursued the completion of endovascular obliteration in these patients. Overall, 80% patients showed clinical improvement.

Figure 5.

A cervical type IVb lesion fed by the RMA from the left vertebral artery (A) in a 24-year-old woman. B) Venous phase. C) Microcatheter close to the fistula. D) Post-embolization check angiogram. E) Glue cast. F) Large linear epidermal naevus on the neck and face.

Figure 6.

MRI in a 2-year-old girl shows cord oedema and flow voids (A). B) Angiography reveals a large RMA feeder from the rt D8 intercostal artery. C) Venous drainage flows inferiorly and then exists the dural sac to flood the vertebral venous plexus and azygous system. D) Check angiogram after embolization. E) Glue cast.

Figure 7.

A large type IVc lumbar lesion in a 6-year-old girl fed by a PSA feeder from the left L2 level (A). B) An ASA feeder from left L1 level. C) Microcatheter injection in the PSA feeder. D) Hyperform balloon inflated in the left L1 lumbar artery to reduce flow. E) Microcatheter injection in the ASA feeder after glue injection in the PSA feeder, F) Glue cast in the sac as well as the distal part of feeders. Check angiography shows preserved ASA axis (black arrow) (G) and PSA (white arrow) (H).

Total occlusion was seen in both of the type IVc lesions. However, one patient showed neurological deterioration. In the other patient enlarged ASA and PSA supplied the fistula sac in the lumbar region. This patient showed an excellent improvement at one-year follow-up, although with residual urinary incontinence (Figure 7A-H).

Complications and technical difficulties

Microcatheterization failed in three patients (two type IVa microfistulae and one type IVb macrofistula). Two patients with type IVa microfistulae were referred directly for surgery due to anticipated difficulty in microcatheterization. Extravasation or perforation was not encountered in any of the patients. Glue reflux into the anterior spinal artery occurred in one patient. In this patient there was neurological deterioration. Venous passage of glue mixture was more than desired in one patient, but there was no related clinical deterioration.

Discussion

PMAVF is a distinct category of spinal vascular malformations. The lack of a nidus differentiates these lesions from the type II and III spinal AVMs and the intradural location of the arteriovenous shunt with the involvement of arteries feeding the cord differentiate it from dural AVFs 1,3,8. PMAVFs are thought to be congenital, sometimes in association with subcutaneous vascular nevi as seen in our case 13 (Figure 5). Metameric AVMs affect two or more tissues derived from the same metamere. More often these are arteriovenous malformations and rarely in the form of PMAVF 9,10. However, a few reports provide evidence that some of these may be acquired as post-traumatic or post-surgical lesions 11.

Venous hypertension with congestive myelopathy, vascular steal, mass effect from large venous sacs and less commonly haemorrhage are usually responsible for symptoms 11-14.

PMAVFs are located on the surface of the cord subpially 6,13 anterior, posterior or lateral to the cord 7. The blood supply is from the extramedullary pial arteries that arise from branches of PSA and/or the lateral branches of ASA 8,13. Direct supply from the RMA is not mentioned in the available literature. In our case material, we found a dominant supply directly from the RMA in five lesions. In these cases the ascending limb of the artery supplied the lesion and it did not take the characteristic hairpin bend to fill the anterior or posterior spinal artery segment.

In general, the location and size of the fistula dictates the treatment strategy. The tiny filum terminale lesions appear to be a good indication for surgical treatment owing to accessibility problems with the endovascular approach. However, surgical treatment is no less challenging as sometimes a fistula embedded between congested veins is difficult to find intra-operatively and localization and eradication of the shunt may become very difficult 7.

For endovascular treatment good angiographic assessment is important. It helps decide on feasibility, approach and hardware. It is important to make a distinction between a type II intramedullary AVM and a microfistula, the difficulty sometimes encountered is succinctly mentioned by Rodesch et al. 1. In type IVa PMAVFs, it is usually difficult to advance the microcatheter close enough to the fistulous point due to the tortuous and long course of the feeding pedicles. A tiny conus or filum terminale lesion is a good example. Currently, with improvements in microcatheter technology, more lesions can be effectively treated via the endovascular route 1,15. It cannot be overemphasized that safe and distal microcatheterization for spinal endovascular procedures demands adequate training and experience. Embolization of the fistulous shunt by glue cast including the distal portion of the feeding artery, the arteriovenous communication, and the proximal portion of the draining vein cures the lesion permanently. The point is well illustrated in a cervical lesion treated by us. Fed by the ASA from the vertebral artery, the lesion was treated surgically 20 years earlier. The recurrence was just distal to the surgical clip fed by a branch of the thryrocervical artery. This was effectively treated with glue embolization (Figure 2).

Although precise embolization is essential to minimize collateral damage to the adjacent cord, it in itself does not guarantee an improvement in neurological deficits. Thus with a precise delivery of glue material, good clinical improvement was seen in cases 7 and 13, but case 9 did not show any improvement. Factors influencing recovery after embolization in spinal vascular lesions are discussed by Xianli et al. 16. Clinical recovery is likely to depend on many factors like initial degree and duration of neurological deficit and previous cord damage due to either haemorrhage, compressive myelopathy or chronic congestive myelopathy. On the other hand, reduction in vascular steal, reduction in the size and pulsatile pressure of large venous sacs and reduction in venous hypertension after treatment may allow a significant clinical improvement. In that sense early detection and treatment are likely to be beneficial. In addition, our limited material also suggests that PMAVFs with posterior spinal artery or direct radiculomedullary artery supply are likely to fare well. A cautious approach is desirable in the lesions fed by the ASA.

Although not universally accepted, surgery should be considered only when embolization seems to be very hazardous or impossible because of small and tortuous feeders or remote location of the shunt as in filum terminale lesions or where expertise in endovascular therapy is unavailable. The endovascular approach is usually the first-line treatment in patients with type IVb and type IVc PMAVF as the feeding arteries are usually large enough to allow distal microcatheter placement near the fistula 12,15.

To obtain a lasting effect, liquid embolic agents are preferable and NBCA glue appears to be effective 1,17. Polyvinyl alcohol particles 18, detachable and non-detachable latex balloons 19, and coils 20 are unlikely to provide complete obliteration. Clinical complications, recanalization and formation of the collateral circulation are likely to be more frequent with these embolic agents when used alone. A recent report suggests that combined use of coils and onyx may be effective in these lesions 16. Rodesch et al. 1 reported in their large series an angiographic cure rate of 66% in macro-AVFs and 36% in micro-AVFs with glue embolization. Our results compare well with these showing a complete obliteration rate of 60% and a major obliteration as well as clinical improvement in 80% of the patients with macrofistulae. Residual lesions pose a difficulty. Where feasible, further endovascular treatment should be carried out. We agree with Rodesch et al. 1 in not pursuing residual lesions aggressively with follow-up surgery. In general, clinical evaluation and MR imaging follow-up is considered adequate. If the clinical condition is stabilized further treatment is warranted only in case of aggravation of symptoms.

In conclusion, given a safe and effective occlusion of the fistula in a significant number in our cases, we think that endovascular NBCA glue embolization should be discussed as a first option to treat spinal perimedullary arteriovenous fistulae. It is also feasible in many of the type IVa lesions. While angiographic anatomy and the available expertise guide the selection, these are worth one attempt.

References

- 1.Rodesch G, Hurth M, Alvarez H, et al. Spinal cord intradural arteriovenous fistulae: anatomic, clinical, and therapeutic considerations in a series of 32 consecutive patients seen between 1981 and 2000 with emphasis on endovascular therapy. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:973–981. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000181314.94000.cd. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000181314.94000.CD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurst RW. Vascular disorders of the spine and spinal cord. In: Atlas SW, editor. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and spine. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. pp. 1825–1854. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aydin K, Sencer S, Sencer A, et al. Angiography-induced closure of perimedullary spinal arteriovenous ?stula. Br J Radiol. 2004;77:969–973. doi: 10.1259/bjr/30760081. doi: 10.1259/bjr/30760081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Djindjian M, Djindjian R, Rey A, et al. Intradural extramedullay spinal arteriovenous malformations fed by the anterior spinal artery. Surg Neurol. 1977;2(2):85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heros RC, Debrun GM, Ojemann RG, et al. Direct spinal ateriovenous fistula: a new type of spinal AVM. J Neurosurg. 1986;64(1):134–139. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.64.1.0134. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.64.1.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho KT, Lee DY, Chung CK, et al. Treatment of spinal cord perimedullary arteriovenous fistula: embolization versus surgery. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:232–239. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000147974.79671.83. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000147974.79671.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mourier KL, Gobin YP, George B, et al. Intradural perimedullary arteriovenous fistulae: results of surgical and endovascular treatment in a series of 35 cases. Neurosurgery. 1993;32(6):885–891. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199306000-00001. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199306000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hida K, Iwasaki Y, Goto K, et al. Results of the surgical treatment of perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas with special reference to embolization. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(2):198–205. doi: 10.3171/spi.1999.90.2.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berenstein A, Lasjaunias P, ter Brugge K. Spinal arteriovenous malformations. In: Berenstein A, Lasjaunias P, ter Brugge K, editors. Surgical neuroangiography. 2nd. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2004. pp. 737–847. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-18888-6_11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niimi Y, Uchiyama N, Elijovich L, et al. Spinal arteriovenous metameric syndrome: clinical manifestations and endovascular management. Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:457–463. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3212. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrow DL, Colohan ART, Dawson R. Intradural perimedullary arteriovenous ?stulas (type IV spinal cord arteriovenous malformations) J Neurosurg. 1994;81(2):221–229. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.2.0221. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.2.0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ricolfi F, Gobin PY, Aymard A, et al. Giant perimedullary arteriovenous fistulas of the spine: clinical and radiologic features and endovascular treatment. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(4):677–687. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao YH, Ling F. Classification and therapeutic modalities of spinal vascular malformations in 80 patients. Neurosurgery. 1997;40(1):75–81. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199701000-00017. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199701000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodesch G, Hurth M, Alvarez H, et al. Angio-architecture of spinal cord arteriovenous shunts at presentation. Clinical correlations in adults and children. The Bicêtre experience on 155 consecutive patients seen between 1981-1999. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2004;146(3):217–227. doi: 10.1007/s00701-003-0192-1. doi: 10.1007/s00701-003-0192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oran I, Parildar M, Derbent A. Treatment of slow-flow (type I) perimedullary spinal arteriovenous fistulas with special reference to embolization. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(10):2582–2586. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xianli LV, Youxiang LI, Xinjian Y, et al. Endovascular embolization for symptomatic perimedullary AVF and intramedullary AVM: a series and a literature review. Neuroradiology. 2012;54(4):349–359. doi: 10.1007/s00234-011-0880-0. doi: 10.1007/s00234-011-0880-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodesch G, Hurth M, Ducot B, et al. Embolization of spinal cord arteriovenous shunts: Morphological and clinical follow-up and results-review of 69 consecutive cases. Neurosurgery. 2003;53(1):40–50. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000068701.25600.a1. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000068701.25600.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biondi A, Merland JJ, Reizine D, et al. Embolization with particles in thoracic intramedullary arteriovenous malformations: long term angiographic and clinical results. Radiology. 1990;177(3):651–658. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.3.2243964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riché MC, Scialfa G, Gueguen B, et al. Giant extramedullary arteriovenous fistula supplied by the anterior spinal artery: treatment by detachable balloons. Am J Neuroradiol. 1983;4(3):391–394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakstad P, Hald JK, Bakke SJ. Multiple spinal arteriovenous fistulas in Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome treated with platinum coils. Neuroradiology. 1993;35(2):163–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00593978. doi: 10.1007/BF00593978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]