ABSTRACT

Although adenoviruses (AdVs) have been found in a wide variety of reptiles, including numerous squamate species, turtles, and crocodiles, the number of reptilian adenovirus isolates is still scarce. The only fully sequenced reptilian adenovirus, snake adenovirus 1 (SnAdV-1), belongs to the Atadenovirus genus. Recently, two new atadenoviruses were isolated from a captive Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum) and Mexican beaded lizards (Heloderma horridum). Here we report the full genomic and proteomic characterization of the latter, designated lizard adenovirus 2 (LAdV-2). The double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) genome of LAdV-2 is 32,965 bp long, with an average G+C content of 44.16%. The overall arrangement and gene content of the LAdV-2 genome were largely concordant with those in other atadenoviruses, except for four novel open reading frames (ORFs) at the right end of the genome. Phylogeny reconstructions and plesiomorphic traits shared with SnAdV-1 further supported the assignment of LAdV-2 to the Atadenovirus genus. Surprisingly, two fiber genes were found for the first time in an atadenovirus. After optimizing the production of LAdV-2 in cell culture, we determined the protein compositions of the virions. The two fiber genes produce two fiber proteins of different sizes that are incorporated into the viral particles. Interestingly, the two different fiber proteins assemble as either one short or three long fiber projections per vertex. Stoichiometry estimations indicate that the long fiber triplet is present at only one or two vertices per virion. Neither triple fibers nor a mixed number of fibers per vertex had previously been reported for adenoviruses or any other virus.

IMPORTANCE Here we show that a lizard adenovirus, LAdV-2, has a penton architecture never observed before. LAdV-2 expresses two fiber proteins—one short and one long. In the virion, most vertices have one short fiber, but a few of them have three long fibers attached to the same penton base. This observation raises new intriguing questions on virus structure. How can the triple fiber attach to a pentameric vertex? What determines the number and location of each vertex type in the icosahedral particle? Since fibers are responsible for primary attachment to the host, this novel architecture also suggests a novel mode of cell entry for LAdV-2. Adenoviruses have a recognized potential in nanobiomedicine, but only a few of the more than 200 types found so far in nature have been characterized in detail. Exploring the taxonomic wealth of adenoviruses should improve our chances to successfully use them as therapeutic tools.

INTRODUCTION

Adenoviruses (AdVs) occur commonly in humans and in a large spectrum of animals representing every major class of vertebrates (1). Individual AdV types are generally restricted to a single host species, suggesting a long common evolutionary history. Nonetheless, numerous examples of hypothesized host switches have also been described (2). The family Adenoviridae is currently divided into five officially approved genera (1). The Mastadenovirus and Aviadenovirus genera include AdVs infecting only mammals and birds, respectively. The most recently approved genus, Ichtadenovirus, was established for the single known fish AdV, isolated from white sturgeon (3). The two additional genera Atadenovirus and Siadenovirus contain viruses found in more divergent hosts, so their names reflect characteristic features other than a particular vertebrate class. The origin of siadenoviruses, named after the unique presence of a sialidase-like gene close to their left genome end, has yet to be clarified (4). Atadenoviruses are thought to represent the AdV lineage cospeciating with squamate reptiles (2, 5), although the first members of the genus were found in ruminants and birds. They were noted for the strikingly high A+T content of their DNA, hence the genus name (6–8). The genome of the first fully sequenced reptilian AdV (snake adenovirus 1 [SnAdV-1]) showed a characteristic atadenoviral gene arrangement (9), albeit with an equilibrated G+C content (5, 10). The analysis of short sequences from the DNA-dependent DNA polymerase (pol) gene of further, newly reported AdVs from a number of additional animals in the order Squamata, confirmed the balanced G+C content and the phylogenetic place in the Atadenovirus genus for all of these snake and lizard viruses (11–13).

Members of the Adenoviridae family present linear double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) genomes ranging from 26 to 48 kb in size (1). Comparative analysis of genes across this family has identified conserved protein-encoding regions, which have been classified into genus-common and genus-specific genes (14). Genus-common genes are centrally located in the genome, encoding proteins with functions involved in DNA replication (pol, terminal protein precursor [pTP], and DNA-binding protein [DBP]), DNA encapsidation (52K and IVa2), and the architecture of the virion (pIIIa, penton base, pVII, pX, pVI, hexon, protease, 100K, 33K, pVIII, and fiber). Genus-specific genes are mainly located near the ends of the genome, except for mastadenovirus protein V. Minor coat polypeptide IX and core polypeptide V are unique to mastadenoviruses. In atadenovirus virions, the genus-specific structural polypeptides are LH3 and p32K (15, 16). Another variable in AdV genome and virion architecture is the number of fiber proteins. Most mastadenoviruses sequenced so far possess a single gene coding for fiber protein, except members of the species Human mastadenovirus F and G (HAdV-F and HAdV-G), as well as a number of unclassified simian adenoviruses, which have two fiber genes. The products of these genes appear in the virions as a single fiber per penton (17–20). Contrarily, in several poultry AdVs, classified into the Aviadenovirus genus, two fibers per penton are often observed, regardless of the presence of one or two different fiber genes in the genome (21–24).

The AdV fiber is a main determinant of viral tropism. All fiber proteins characterized so far form trimers with three differentiated structural domains. Short N-terminal peptides (one per fiber monomer) form the frayed end of the trimer that joins the fiber to the capsid, by interacting with clefts between monomers of penton base, in a 3:5 symmetry mismatch (25, 26). The three fiber monomers then intertwine to form the shaft domain, made up of a variable number of 15- to 20-residue pseudorepeats, which in turn result in a variable number of structural repeats and variable fiber lengths, depending on the particular virus type (27, 28). Fibers also vary in flexibility; occasional disruptions of the sequence repeat pattern result in shaft kinks (29). Finally, the distal C-terminal head domain (knob) attaches to the primary receptor at the host cell membrane (30), after which AdV is internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis. In the majority of AdVs characterized so far, internalization is mediated by interaction of an RGD sequence in the penton base with integrins in the cell surface (31). Fiber length and flexibility differences most likely reflect differences in viral attachment and internalization mechanisms (32, 33).

The first AdV-like particles in lizards of different species were described based on microscopy studies several decades ago (34–36). Although the frequent occurrence of AdV in different reptilian specimens was well documented (37, 38), for a long time, only a few cases of successful isolation and in vitro propagation were known (39, 40). A consensus nested PCR, targeting a conserved region of the DNA-dependent DNA polymerase gene (pol) of AdVs, has been used successfully to detect novel atadenoviruses in lizards of six different species (11). The isolation of the first three AdV strains originating from lizards was reported more recently (12). Two of these strains seemed to be identical and were obtained from oral swabs taken from apparently healthy Gila monsters (Heloderma suspectum) during a follow-up study after a serious disease outbreak in a Danish zoo. Their pol sequence was identical also to that of the helodermatid AdV described previously in the United States (11). A third strain, with a slightly divergent pol sequence, was isolated from the homogenate of internal organs (intestines, liver, and heart) of a Mexican beaded lizard (Heloderma horridum) that had been kept in the same enclosure with the Gila monsters and died with several other Mexican beaded lizards during the disease outbreak. The isolates seemed to represent two types of a new AdV species and have been described as helodermatid adenoviruses 1 and 2, representing the Gila monsters and the Mexican beaded lizard, respectively (12). More recently however, a closely related pol sequence, showing 100% amino acid (aa) and 99% nucleotide (nt) identity with the helodermatid AdV-2, was obtained from a Western bearded dragon (Pogona minor minor) in Australia (13). This finding indicated that the helodermatid isolates might not be strictly host specific. A less exclusive name, such as “lizard adenovirus,” seemed to be more appropriate for viruses of a seemingly broader host spectrum. Extensive characterization of these first lizard adenovirus (LAdV) isolates appeared intriguing.

In the present article, molecular analyses, including the full genome sequence and proteome analysis of LAdV-2, are described. The presence of two fiber genes and the unexpected architecture of the pentons, consisting of either one short or three long fiber projections per penton base, were the most interesting findings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus propagation and purification.

The LAdV-2 strain was isolated and initially propagated as previously described (12). For the sequencing experiments, virus purification and concentration were performed by pelleting with an ultracentrifuge (Beckman Ti90 rotor). After a freeze-thaw cycle, cell debris was first removed from the cell culture supernatants by low-speed centrifugation (1,500 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and then viruses were concentrated by ultracentrifugation (120,000 × g, 3 h, 4°C). Supernatants were decanted, and pellets were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

For large-scale virus propagation and purification, iguana heart epithelial cells (IgH-2; ATCC CCL-108) (41) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 U/ml penicillin, 10 μg/ml streptomycin, and 1× Sigma nonessential amino acid solution and maintained at 28°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cells were seeded in 10-cm-diameter tissue culture dishes and split at a ratio of 1:3. When the cell monolayers reached 70% confluence, virus-infected supernatant was added. The infection was carried out at 28°C. The cells were collected when substantial cytopathic effect was observed, from 3 to 5 days postinfection.

Virus purification was carried out following protocols similar to those used for HAdV. Infected IgH-2 cells from 200 Falcon 100-mm-diameter tissue culture dishes were collected and centrifuged for 10 min at 800 rpm and 4°C. The cells were then resuspended in 35 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1) and lysed by four freeze-thaw cycles. Cell lysates were clarified to remove cellular debris by centrifugation in a Heraeus Megafuge 1.0R at 3,000 rpm for 60 min at 4°C. The supernatant was layered onto a discontinuous gradient of 1.2 g/ml - 1.45 g/ml CsCl in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1) and centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 120 min at 4°C in a Beckman SW28 swinging bucket rotor. The low- and high-density viral particle bands from each tube were separately collected, pooled, mixed with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), layered on a second CsCl gradient, and centrifuged overnight at 20,000 rpm and 4°C in a Beckman SW40 Ti swinging bucket rotor. The virus bands from each tube were collected and pooled. The final virus pool was loaded into Bio-Rad Econo-Pac 10 DG disposable chromatography columns with a 6,000-Da molecular mass cutoff for buffer exchange to 20 mM HEPES–150 mM NaCl (pH 7.8). The virus concentration (in virus particles [vp]/ml) was determined by absorbance as described previously (42). Purified virus was stored at −80°C after addition of glycerol to a final concentration of 10%.

PCR and molecular cloning.

Genomic DNA was extracted from LAdV-2 particles concentrated by ultracentrifugation with the Qiagen DNeasy tissue kit (Hilden, Germany). Initially, random cloning of the HindIII- and PstI (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany)-digested viral DNA into phagemid pBluescript II KS(+/−) (Stratagene, Ltd., Santa Clara, CA) was performed. The cloned fragments were identified by sequence analysis. The sequences of additional genome regions were obtained from the genes of the IVa2 and penton base proteins after PCR amplification with degenerate consensus primers. A consensus primer was also designed based on the known adenoviral inverted terminal repeat (ITR) sequences. With this, the left genome end encompassing a part of the IVa2 gene was amplified and sequenced. A specific leftward primer was designed from the sequence of the putative p32K gene. The exact sequence of the left ITR was determined after a unidirectional PCR with this p32K-specific primer. With the use of the terminal transferase from the 5′/3′ 2nd-generation rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) kit (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany), a poly(A) tail was added to the 3′ end of the single-stranded PCR product. This molecule was then PCR amplified using the p32K-specific and poly(T) primers. Additional specific PCR primers were designed to amplify regions between the genome fragments already sequenced. Amplification of the genome part rightwards from the fiber genes was facilitated by the sequences of several smaller fragments obtained from the random cloning. For PCR amplification of fragments shorter than 1,000 bp, DreamTaq Green DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific Baltics UAB, Vilnius, Lithuania) was applied, whereas for larger fragments, Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase from Finnzymes (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Espoo, Finland) was used. Annealing temperatures and elongation times were adjusted according to the primers used and the expected lengths of the PCR products.

Sequencing and sequence analysis.

To confirm their identity and homogeneity, each PCR product was first sequenced using the respective PCR primers. The sequencing reactions were set up with the use of the BigDye Terminator V3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) and run on an ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer by a commercial service. The programs applied for bioinformatics analyses have been described in detail recently (43). Raw nucleotide sequences were handled with the BioEdit program. To detect the homology and identity of the sequenced gene fragments, different BLAST algorithms at the NCBI server were used. Sequence editing and assembly were performed manually or with the Staden sequence analysis package. Genome annotation was carried out with the CLC Main Workbench, version 6.9. Protein sequences were analyzed using SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de).

Phylogenetic tree reconstruction.

Multiple amino acid alignments from the hexon and protease sequences were prepared with ClustalX 2.1. Several representatives from all five officially approved AdV genera were included. Phylogenetic tree reconstructions were performed by maximum likelihood (ML) analysis (44). Model selection was carried out by ProtTest 2.4, based on the guide tree constructed by the protdist and fitch algorithms (Jones-Taylor-Thornton [JTT] model and global rearrangements) of the Phylip package (version 3.69). For the hexon tree, the LG + G model was used with an alpha value (gamma distribution shape parameter) of 0.61. For construction of the protease-based tree, LG + I + G was applied (proportion of invariant sites: 0.06, gamma distribution shape parameter, 1.13). ML with bootstrapping (100 samples) was performed by the phyml algorithm, provided at the Mobyle portal (http://mobyle.pasteur.fr). FigTree v1.3.1 was used for visualization of the phylogenetic trees.

Characterization of purified virus and disassembly products by protein electrophoresis and electron microscopy.

For SDS-PAGE, samples were incubated at 95°C in loading buffer containing 2% SDS, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) and loaded into either 15% or 4 to 20% (Bio-Rad Mini-PROTEAN TGX precast gradient) acrylamide gels that were silver stained according to standard protocols. To estimate the relative amounts of fiber proteins, band intensities in silver-stained gel images were measured with ImageJ (45). To avoid interference in the measured values for protein fiber1 due to the proximity of the intense LH3 band, only gels where a clear separation between the two bands was observed were used for quantitation. Moreover, only the area below the half peak away from the closest neighbor was measured, after correction for the background intensity.

For negative-staining electron microscopy (EM), 5-μl sample drops were incubated on glow-discharged collodion/carbon-coated grids for 5 min and stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 45 s. Grids were air dried and examined in a JEOL 1011 transmission electron microscope at 100 kV. Measurements of viral particle diameter and fiber length were carried out using ImageJ, on micrographs digitized on a Zeiss SCAI scanner with a sampling step of 7 μm/pixel (px), giving sampling rates of 4.67 Å/px for the virus and 3.5 Å/px for the fibers. Fiber shaft length was measured between the edge of penton base and the broadening indicating the C-terminal knob domain.

Controlled disruption of virions.

A virus disruption protocol based on hypotonic dialysis followed by centrifugation (46) was used to obtain a sample enriched on viral vertex components. Purified virus was dialyzed against 5 mM Tris-maleate (pH 6.3)–1 mM EDTA for 24 h at 4°C and centrifuged at 20,200 × g for 60 min at 4°C. The supernatant was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and negative-staining EM as described above.

MS analyses.

The proteins present in purified LAdV-2 virions were determined by in-solution digestion and liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI MS/MS) analysis, as follows. Samples were dissolved in 8 M urea–25 mM ammonium bicarbonate, reduced, and alkylated with 50 mM iodoacetamide. The urea concentration was reduced to 2 M with 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Trypsin (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was added in a 25:1 (wt/wt) ratio, and incubation proceeded overnight at 37°C. Nano-LC-ESI MS/MS analysis of the digested samples was performed using an Eksigent 1D-nano-high-performance liquid chromatography (nano-HPLC) device coupled via a nanospray source to a 5600 TripleTOF quadrupole time of flight (QTOF) mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA). The analytical column used was a silica-based reversed-phase column, Eksigent chromXP (75 μm by 15 cm, 3-μm particle size, 120-Å pore size). The trap column was chromXP, with a 3-μm particle diameter and 120-Å pore size. The loading pump delivered a solution of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in 98% water–2% acetonitrile (LabScan, Gliwice, Poland) at 30 μl/min. The nanopump provided a flow rate of 300 nl/min, using 0.1% formic acid (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) in water as mobile phase A and 0.1% formic acid in 80% acetonitrile–20% water as mobile phase B. Gradient elution was performed as follows: isocratic conditions of 96% A–4% B for 5 min, a linear increase to 40% B in 60 min, a linear increase to 95% B in 1 min, isocratic conditions of 95% B for 7 min, and a return to initial conditions in 10 min. The injection volume was 5 μl. Automatic data-dependent acquisition using dynamic exclusion allowed the acquisition of both full-scan (m/z 350 to 1,250) MS spectra followed by tandem MS collision-induced dissociation (CID) spectra of the 25 most abundant ions. MS and MS/MS data were used to search against a customized database containing all of the LAdV-2 protein sequences derived from the genome, using MASCOT v.2.2.04. The search parameters were carbamidomethyl cysteine as a fixed modification and oxidized methionine as a variable one. Peptide mass tolerance was set at 25 ppm and 0.6 Da for the MS and MS/MS spectra, respectively, and 1 missed cleavage was allowed.

For in-gel protein digestion and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–tandem TOF (MALDI-TOF/TOF) protein band identification, silver- or Coomassie-stained bands were excised, deposited in 96-well plates, and processed automatically in a Proteineer DP (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). The digestion protocol used was based on that described in reference 47, with minor variations. After in-gel digestion, 20% of each peptide mixture was deposited onto a 386-well OptiTOF plate (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA) and allowed to dry at room temperature. A 0.8-μl aliquot of matrix solution (3 mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in MALDI solution) was then added, and after drying at room temperature, samples were automatically analyzed in an ABI 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA) working in the positive-ion reflector mode (ion acceleration voltage of 25 kV for MS acquisition and 1 kV for MS/MS). Peptide mass fingerprinting and MS/MS fragment ion spectra were smoothed and corrected to zero baseline using routines embedded in the ABI 4000 Series Explorer software v3.6. Internal and external calibration was allowed to reach a typical mass measurement accuracy of <25 ppm. To submit the combined peptide mass fingerprinting and MS/MS data to MASCOT software v.2.1 (Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom), GPS Explorer v4.9 was used, searching in the customized protein database containing all of the LAdV-2 protein sequences derived from the genome.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The full sequence of LAdV-2 has been deposited in GenBank and assigned accession no. KJ156523.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General features of the genome.

The genome of LAdV-2 consists of 32,965 bp, with an average G+C content of 44.2%. The genome is flanked by inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) of 127 bp, the longest known to date in the Atadenovirus genus. Figure 1A shows a schematic of the LAdV-2 genetic map, with 34 putative genes. Of these, 30 were identified based on homology with adenoviral genes described earlier. In the highly variable right end of the genome, four additional open reading frames (ORF2, -3, -4, and -5) capable of coding for proteins with a minimum length of 50 aa were found. The average distance between two genes was short—generally less than 50 bp, with only four exceptions. On the other hand, 11 gene overlaps were detected. The proportion coding region is 95.5%.

FIG 1.

Genomic characterization of LAdV-2. (A) Schematics of the LAdV-2 genetic map. Shading of the arrows marks the specificity of the genes. The G+C content of the genomic DNA is shown under the genome map. (B) Phylogeny reconstructions based on the hexon and protease amino acid sequences. Unrooted calculations were done by the ML method.

The first gene at the left end of the genome was the p32K gene on the l (leftward-transcribed) strand. This protein is a unique characteristic of the Atadenovirus genus. Rightwards, the homologues of three LH (left-hand) genes, another special attribute of atadenoviruses (48), were identified. The orientations and sizes of these ORFs were similar to those of their homologues in SnAdV-1 (5).

The organization of the highly conserved central part of the LAdV-2 genome is largely concordant with that in all AdVs. On the l strand, the general AdV pattern of the E2A and E2B regions was found, with homologues for the genes of DNA-binding protein (DBP), terminal protein precursor (pTP), pol, and IVa2, as well as a putative homologue of the atadenoviral U-exon (5, 14). On the r strand, 14 conserved genes were identified. Unexpectedly, at the right end of this (supposedly late) transcription unit, two fiber genes of different sizes were found in tandem (Fig. 1A). The first fiber gene (fiber1), highly similar to the fiber gene of SnAdV-1, was shorter (996 bp), whereas the second one (fiber2) encompassed 1,302 bp. In accordance with previous findings (14), neither gene homologues for the mastadenoviral structural protein V and IX genes nor a region corresponding to the mastadenoviral E3 were found.

At the right-hand side of the LAdV-2 genome, a typical atadenoviral E4 region was identified, with homologues for all three E4 genes (E4.1 to E4.3) of SnAdV-1 in the same position, as well as a homologue of the SnAdV-1 URF1 on the l strand (named ORF6 in Fig. 1A). Also as in SnAdV-1, a single right-hand (RH) gene was identified, followed by a putative gene (ORF5) capable of coding for a protein of 416 aa with no detectable homology to any known proteins. Further rightwards on the r (rightward-transcribed) strand, an ORF with homology to the unique ORF1 of duck adenovirus 1 (DAdV-1) was found and consequently also named ORF1. Another putative gene (ORF2), predicted to code for a protein of 97 aa of unknown function, was found as the last ORF on the r strand. On the l strand, a homologue of the 105R gene was found. This hypothetical gene was first described in the tree shrew AdV-1 (49), then a homologue was identified in the SnAdV-1 genome (50). The last two short ORFs (ORF3 and ORF4 in Fig. 1A) on the l strand closest to the right ITR showed no detectable homology to any known genes in GenBank. None of these ORFs (ORF1 to -6) have been experimentally confirmed to be functional genes.

In all phylogeny reconstructions performed, LAdV-2 clearly clustered among members of the Atadenovirus genus. The ML trees based on the hexon and protease protein sequences are presented in Fig. 1B. LAdV-2 always appeared as a sister branch to SnAdV-1. There was no significant difference in the topologies of trees resulting from the different genes. Branching of the five genera was supported with maximal or high bootstrap values.

Large-scale propagation and purification of LAdV-2.

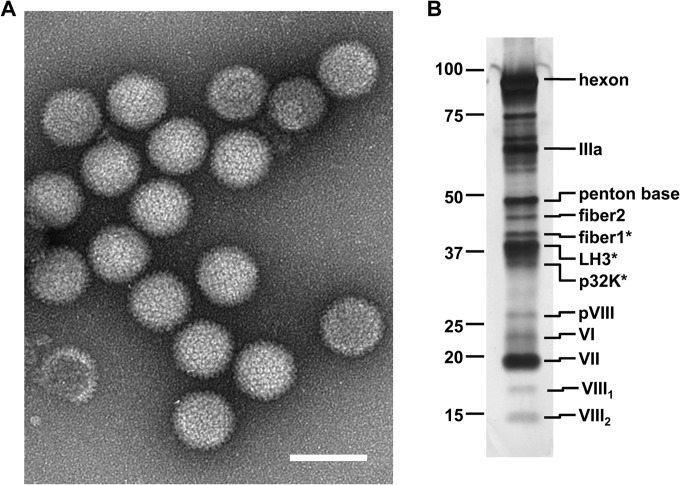

Initial seeds consisted of supernatants from IgH-2 cells infected with LAdV-2 isolated from a Mexican beaded lizard (Heloderma horridum) (12), containing approximately 105 virus particles (vp)/ml. Serial amplification was used to achieve enough infective supernatant for large-scale virus production. After four rounds of amplification, a viral concentration of 1.5 × 1012 vp/ml was obtained, indicating that LAdV-2 can be propagated and purified by a double CsCl gradient from cell culture with yields similar to those of other well-characterized AdVs, such as HAdV-5. EM analyses showed the expected morphology for an atadenovirus (Fig. 2A), with particles 84 ± 6 nm in diameter (n = 50) and an icosahedral but less-faceted shape than HAdV (16).

FIG 2.

Molecular composition of purified LAdV-2. (A) Negative-staining EM image showing the general morphology of the LAdV-2 capsid. The bar represents 100 nm. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified virions in a 4 to 20% gradient gel. Labels on the left-hand side indicate the positions of standard molecular mass markers (kDa). Labels on the right indicate the positions of virion proteins. Asterisks denote bands where protein identification was carried out by MS/MS.

Molecular composition of purified LAdV-2.

After full sequencing of the LAdV-2 genome, we sought experimental confirmation of the expression and incorporation into the virion of the predicted structural proteins. Table 1 summarizes the proteins identified when samples of purified LAdV-2 were subject to nano LC-ESI MS/MS analysis. Expected virion components, by analogy with human AdV, were detected: hexon, penton base, IIIa, IVa2, VI, VII, VIII, terminal protein, and protease. The product of the 52K gene was also detected in nonnegligible amounts. In HAdV-5, the equivalent protein, L1 52/55K, is removed from the capsid during packaging and maturation (51, 52). Therefore, the detection of 52K in LAdV-2 points to the presence of a minor population of immature virus particles (young virions) in the CsCl gradient heavy band. In addition, the specific gene products from Atadenovirus LH3 and p32K were found. Small traces of 33K and 100K proteins were also present in the samples.

TABLE 1.

Proteome of purified LAdV-2 virions

| Protein | Predicted molecular mass (Da) of immature proteina | Calculated pI | Total no. of peptides (no. of significant) matches | Sequence coverage (%) | MASCOT scoreb | emPAI value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexon | 102,040 | 5.44 | 404 (399) | 73 | 21,650 | 24.08 |

| pIIIa | 66,941 | 5.89 | 140 (138) | 62 | 7,919 | 15.25 |

| pVI | 24,075 | 9.73 | 90 (87) | 83 | 5,186 | 16.43 |

| Penton base | 50,713 | 5.75 | 71 (69) | 69 | 3,666 | 7.19 |

| LH3 | 41,838 | 6.59 | 77 (75) | 61 | 3,516 | 6.63 |

| pVIII | 30,750 | 5.78 | 51 (51) | 71 | 2,993 | 7.65 |

| pVII | 15,239 | 12.23 | 47 (46) | 55 | 1,848 | 11.31 |

| fiber1 | 34,826 | 5.15 | 29 (28) | 44 | 1,465 | 2.37 |

| p32K | 40,025 | 11.02 | 32 (32) | 36 | 1,327 | 3.90 |

| Protease | 23,245 | 9.32 | 28 (28) | 50 | 1,150 | 5.08 |

| IVa2 | 48,186 | 8.53 | 23 (22) | 46 | 1,128 | 1.42 |

| fiber2 | 45,930 | 5.55 | 22 (21) | 40 | 776 | 1.53 |

| 52K | 37,765 | 5.56 | 14 (14) | 27 | 648 | 1.84 |

| pTP | 69,780 | 7.71 | 10 (10) | 15 | 448 | 0.42 |

| pX | 10,080 | 12.8 | 11 (10) | 17 | 233 | 1.34 |

| 100K | 77,178 | 6.07 | 3 (3) | 8 | 125 | 0.13 |

| 33K | 20,321 | 6.36 | 5 (5) | 17 | 71 | 0.80 |

The cleavage specificity of the atadenovirus protease is not well defined yet.

The identified proteins are sorted by MASCOT score, as described in reference 67.

The LAdV-2 genome contained two different genes coding for fiber, with predicted products of 35 kDa (fiber1) and 46 kDa (fiber2). The MS/MS analysis revealed that both fiber gene products are expressed and incorporated into the virions. This is the first case reported of an atadenovirus with two different fibers. Figure 2B shows the SDS-PAGE characterization of purified virions. Bands for hexon (102 kDa), IIIa (67 kDa), penton base (51 kDa), and fiber2 were observed at the positions expected for their molecular mass. Bands in the 35- to 40-kDa range were excised and analyzed by MS/MS. Interestingly, the band identified as containing the 35-kDa fiber1 protein had a slower electrophoretic mobility than LH3 (42 kDa) and p32K (40 kDa). This anomalous electrophoretic mobility may indicate posttranslational modifications in LAdV-2 fiber1. Protein p32K is considerably larger in reptilian AdVs than its homologue in the prototype atadenovirus ovine adenovirus 7 (OAdV-7) (32 kDa) (9) and is highly basic (pI 11) (Table 1), suggesting its ability to bind to the viral genome and play a role similar to that of mastadenovirus-specific polypeptide V (16). We interpret an ∼30-kDa band as the precursor of polypeptide VIII (pVIII), probably coming from the immature particles present in the purification. The next band, running at ∼25 kDa, was assigned to polypeptide VI based on both its molecular mass and MS/MS identification (described below). A band running close to the 20-kDa marker was assigned to polypeptide VII on the basis of its abundance, although the protein molecular mass is much lower (15 kDa). The 13-kDa OAdV-7 polypeptide VII has also been reported to have a lower electrophoretic mobility than expected (9, 15). Finally, two bands in the 15- to 18-kDa range could correspond to the maturation products of polypeptide VIII, as previously reported for OAdV-7 (15). If we consider the consensus cleavage patterns for the HAdV-2 protease (53), possible cleavage sites at position 121-122 (LHGGA) in LAdV-2 polypeptide VIII would lead to a 14-kDa fragment and a 17-kDa fragment consistent with the two observed bands.

Penton architecture in LAdV-2.

Previously reported AdVs with two fiber genes present two different types of penton architecture: either the two fibers bind to different penton bases, as in HAdV-40 and HAdV-41 (17, 19, 20), or both fibers bind to the same penton base, as in FAdV-1 (CELO virus, species Fowl adenovirus A) (23), FAdV-4, and FAdV-10 (Fowl adenovirus C) (24, 54). Fibers are difficult to visualize in negatively stained EM images of complete virions, due to their large difference in size with the capsid. Therefore, to ascertain which of the two arrangements was present in LAdV-2, we subjected the purified virus to controlled disruption based on a protocol previously shown to cause penton and peripentonal hexon release in HAdV (46). In this way, a preparation enriched in LAdV-2 vertex components was obtained. SDS-PAGE analysis together with MS protein identification of the gel bands (Fig. 3A) showed the two fiber proteins, as well as penton base, hexon, and protein VI, consistent with the preparation containing pentons and peripentonal hexons together with associated polypeptide VI.

FIG 3.

LAdV-2 penton architecture. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of the vertex-enriched preparation obtained after mild disruption using hypotonic dialysis and centrifugation. Asterisks indicate protein identification by MS/MS of excised gel bands. (B) Gallery of negative-staining EM images showing examples of a single fiber bound to one penton base, as represented by the drawing in panel C. (D) Gallery of pentons with three fibers attached to a single penton base, as illustrated by the drawing in panel E. In panels B and D, the scale bar represents 20 nm, and white arrowheads point to kinks in the fiber shafts. (F) Examples of negatively stained viral particles showing a fiber triplet. In the top row, arrows indicate the fiber knobs, while the trajectory of the shafts is highlighted with white curves in the bottom row. The bar represents 50 nm. (G and H) Prediction of structural domains in fiber1 (G) and fiber2 (H). The shaft pseudorepeats are aligned, and those with the largest departures from the repeating pattern that could originate kinks are highlighted in gray. The putative penton base binding peptide is underlined. On the right-hand side of each panel, a drawing shows the predicted number of structural repeats in the fiber shafts, and arrows indicate the locations of the predicted kinks.

When imaged at the EM, some of the vertex complexes showed a single fiber (Fig. 3B and C), while others, surprisingly, presented three longer fibers attached to a single penton base (Fig. 3D and E). Long fiber triplets could also be discerned on negatively stained purified virus (Fig. 3F). Measurements on the negative-staining EM images of vertices indicated that the short fiber shaft is 180 ± 30 Å long (n = 110), while the long fiber shafts measure 260 ± 30 Å (n = 237 fibers; 79 penton complexes). The presence of the three domains, namely, the N-terminal tail, the shaft, and the C-terminal knob of the LAdV-2 fiber proteins, was predicted by manual alignment of the amino acid sequence with the model proposed by van Raaij et al. (28), as shown in Fig. 3G and H. The tail region is longer for fiber1 than for fiber2 (38 and 30 residues, respectively), while the head domains contain 123 (fiber1) and 120 (fiber2) residues, predicting smaller knobs than those found in mastadenoviruses (∼180 aa in HAdV-2) or aviadenoviruses (over 200 aa for both fiber knobs of FAdV-1) (28, 55, 56). Small fiber heads seem to be a common trait in atadenoviruses: the SnAdV-1 fiber head is predicted to have 111 residues (57), and the OAdV-7 fiber head is also smaller, as observed by EM (16). Both fibers include a conserved penton base binding motif in their N-terminal tails (Fig. 3G and H) (25). The LAdV-2 fiber1 shaft is predicted to consist of 10 repeats, while fiber2 would have 15. Given the fiber length measured from the EM images, the repeats would be spaced by 18 Å in fiber1 and 17 Å in fiber2, slightly larger in both cases than the spacing observed in the structure of the HAdV-2 fiber shaft (13 Å) (28). Disruptions of the pattern sequence suggest possible sites for shaft kinks in the third repeat of fiber1 (counting from the head) and in the 5th, 7th, and 11th repeats in fiber2 (black arrows in Fig. 3G and H). In agreement with these predictions, EM images of penton complexes often showed long fibers with sharp kinks occurring at different distances from the knob, while short fibers appeared more rigid, with an occasional kink close to the head domain (arrowheads in Fig. 3B and D). All together, these observations indicate that in LAdV-2 there are two different kinds of vertices (Fig. 3C and E): some with a triplet of the long fiber (fiber2) and some with a single, short fiber coded for by the fiber1 gene. There is no previous evidence of any AdV with three fibers per penton or with two different fiber/penton ratios in the same virion.

The presence of a triple fiber raises a new question regarding the interaction with the penton base. In vertices with single fibers, each one of the three N-terminal fiber tails can bind to each one of the five penton base clefts, adopting a 3:5 symmetry mismatched arrangement (25). By comparison with all other characterized AdV fibers, the LAdV-2 fiber2 triplet should have 9 N-terminal tails, all with the same ability to bind to only 5 sites in the penton base oligomer. How can this 9:5 symmetry mismatch be solved? One possibility is that the five binding sites in penton base are filled by fiber tails randomly—that is, one fiber would occupy three sites and the other two only one each, or two fibers would occupy two binding sites and the third the last one. This binding pattern would seem too prone to instability and fiber loss. Another possibility is that the fibers interact with each other independently of penton base. This option is supported by the occasional observation of groups of three fibers without any associated penton base in heat-disrupted LAdV-2 preparations (Fig. 4A). Although at this point, we cannot rule out that these formations arise from unspecific interactions between fibers when separated from the penton base, their appearance suggests a structural arrangement in which fibers interact with each other by their N-terminal tails. Figure 4B shows two alternative ways in which a fiber triplet, assembled as an independent complex, could interact with a penton base maintaining a 3:5 symmetry mismatch equivalent to that of a single fiber. One possibility is that for each fiber trimer, two of the three N-terminal tails are engaged in interactions with the other fiber molecules forming a dimeric tail, while the third one is free to bind to penton base. Alternatively, all N-terminal tails might be interacting among themselves, forming three trimeric tails, each one interacting with a penton base cleft. Further structural work is required to solve this puzzle.

FIG 4.

Symmetry mismatches in the LAdV-2 penton organization. (A) Gallery of negative-staining EM images showing examples of triple fibers forming a complex in the absence of the penton base, observed in purified LAdV-2 preparations after heating at 50°C. The size bar represents 20 nm. (B) Drawings depicting different ways to fulfill the fiber-penton base symmetry mismatches. For a single fiber, each of the three N-terminal tails binds to one of the five equivalent interfaces between penton base monomers. For the LAdV-2 triple fibers, two possibilities are envisaged. First, each fiber uses two N-terminal tails to bind to its two partners and the third to bind to the penton base in a similar way as for the single fiber. Alternatively, all N-terminal tails associate as triplets, and each triplet binds to the penton base. Zigzag lines (continuous, dashed, or dotted) represent the three N-terminal tails of each trimeric fiber. Short transversal lines between zigzags indicate interactions between N-terminal tails of different fibers. The penton base pentamer is represented as a pentagon. (C) Example of purified LAdV-2 protein bands in a 10% acrylamide gel used for estimation of the fiber1/fiber2 ratio by densitometry. (D) A model for the distribution of the two different types of vertices in the LAdV-2 virion with a fiber1/fiber2 ratio of 1.6.

Stoichiometry of fibers.

The exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) parameter obtained in LC-MS/MS analyses is linearly related to the relative abundance of each protein in the sample (58). For each protein in the sample, the ratio between the number of observed and observable peptides (PAI) is calculated, and the emPAI value is given by emPAI = 10PAI − 1. In the proteome analysis of purified virions (Table 1), the emPAI values were 2.37 for fiber1 and 1.53 for fiber2, suggesting that fiber1 is more abundant that fiber2, with a fiber1/fiber2 ratio of approximately 1.5. A repetition of the LC-MS/MS with a different viral preparation gave emPAI values of 1.60 (fiber1) and 0.59 (fiber2)—that is, an estimated fiber1/fiber2 ratio of 2.7. The intensity of fiber1 bands in SDS-PAGE of either vertex preparations (Fig. 3A) or purified virus (Fig. 2B) also appeared slightly stronger than that of fiber2. Gel band densitometry under conditions where silver staining was not saturated (Fig. 4C) gave a 2.0 ± 1.0 (n = 3) fiber1/fiber2 ratio. The exact fiber stoichiometry cannot be derived from either of the two estimations described above. However, the fact that they all indicate a higher copy number for fiber1 than for fiber2, together with the constraints imposed by icosahedral geometry, provide a narrow set of possibilities for the arrangement of the two different kinds of vertices in the LAdV-2 virion.

Let us call the number of vertices with a single fiber1 projection V1, and the number of vertices with a triplet of fiber2 V2. Since all previously described AdV fibers form trimers, we assume that both fiber1 and fiber2 form trimers also. Therefore, the total number of fiber1 molecules (f1) in the virion will be f1 = 3 × V1, and the total number of fiber2 molecules will be f2 = 3 × 3 × V2. From the LC-MS/MS emPAI and the gel band densitometry estimations, we know that f1 > f2, and therefore V1 > 3 × V2. On the other hand, an icosahedron has a total of 12 vertices, therefore V1 + V2 = 12. It is clear that these two conditions can only be fulfilled for V2 values lower than 3. Therefore, our results indicate that each LAdV-2 virion has only one or two vertices harboring a triplet of long fibers. The first possibility, V2 = 1, would give an f1/f2 ratio of 11:3 = 3.67, while the second one, V2 = 2, would give f1/f2 = 10:6 = 1.67. The LC-MS/MS and gel band densitometry estimations give a range of f1/f2 values around 2, favoring the solution where V2 = 2. A model for this peculiar vertex arrangement is shown in Fig. 4D. However, it must be considered that the data presented do not rule out the possibility that the actual vertex distribution varies between viral particles. Interestingly, a similar situation may be present in the enteric virus HAdV-41, for which it has been reported that the short fiber is approximately 6 times more abundant than the long one in virions (19). Therefore, to fulfill the icosahedral geometry, the long fiber should be present in only two vertices per HAdV-41 virion.

Biological significance of the unusual LAdV-2 penton architecture.

The LAdV-2 genome differs from those of all previously characterized members of the Atadenovirus genus in that it contains two different genes coding for fiber proteins. LAdV-2 not only has two fibers with different lengths and flexibility, but surprisingly, we observe that one of the fibers associates in triplets with a single penton base, in only a few vertices per virion. Neither triple fibers nor a mixed number of fibers per vertex had previously been described for any AdV. These first observations on the architecture of LAdV-2 open intriguing questions for future structural studies. At this point, it is not known what the spatial distribution of the different vertices in the virion is, if this distribution is the same in all particles, or what its determinant factors are. For HAdV-41, it has been reported that different expression levels for the two fiber proteins correlate with their stoichiometry in the capsid (19). In LAdV-2, the ability of fiber2 to assemble in triplets in the absence of the penton base introduces a new variable.

AdV fiber proteins are responsible for receptor attachment, thus determining tissue tropism. Most of the well-characterized AdVs use cell surface protein CAR as a primary receptor. CD46, DSG-2, and sialic acid are also known receptors for HAdVs (59). Regarding the AdVs with more than one fiber gene, it is known that the long fiber of species HAdV-F members can bind CAR (60). The FAdV-1 long fiber, which is dispensable for infection in chicken cells, is required for infection of CAR-expressing mammalian cells, although direct binding has not been proved (55, 61). No receptor has been identified for the short fibers in either HAdV-40 or -41 or FAdV-1. In mastadenoviruses, fiber knobs binding sialic acid tend to have high isoelectric points (beyond 8 for canine AdV-2, HAdV-19, and HAdV-37). The two predicted LAdV-2 fiber heads (Fig. 3G and H) have lower pIs (4.69 for fiber1 and 6.76 for fiber2), closer to those of viruses using CAR (e.g., HAdV-2, pI ∼6), or CD46 (pI ∼5 or even lower for HAdV-11, -21, and -35) as receptors. Apart from the receptor binding properties of the knob, the length and flexibility of the shaft also play a role during entry (33). For example, the fiber of HAdV-37 (species HAdV-D) has a CAR binding knob, but its short (8 repeats), rigid shaft hinders efficient entry using CAR (32). On the other extreme, engineering an extra-long fiber (32 repeats, 10 more than in the native fiber) reduced CAR-dependent infectivity in HAdV-5 (62). These studies suggest that fiber length and flexibility modulate the virus-cell surface distance upon attachment to its primary receptor (e.g., CAR), to ensure the correct molecular interaction between other capsid proteins (e.g., penton base) and a second cellular receptor (integrin), triggering virus endocytosis.

What, then, are the roles of the two different fibers in LAdV-2? Since the LAdV-2 penton base lacks an integrin-binding RGD loop, it is possible that the two different fiber heads are needed for binding two different receptors: one for attachment and one for internalization. Remarkably, HAdV-40 and -41 (species HAdV-F), which also have two different fibers, are the only known HAdVs lacking an RGD motif in their penton base. The peculiar triple fiber, unique so far among all described AdVs, might be involved in clustering cell membrane factors required for viral entry. Alternatively, the presence of two different fiber heads may expand the viral tropism, allowing propagation in two different types of cells or tissue. An LAdV-2-like virus with a single nucleotide difference in the sequence of the PCR-amplified pol fragment has been described recently in a sample from a Western bearded dragon (13). Thus, the provenance of LAdV-2 concerning its original host remains unclear. In the seemingly relaxed host specificity of LAdV-2, the presence of the two types of fiber genes and different penton architectures certainly plays a crucial role that deserves further scrutiny. It would also be interesting to sequence and compare the genome of LAdV-1, whereas targeted surveys may help find out if lizards of any additional species can be infected by LAdV-2.

Recombinant HAdVs are widely used as vehicles for gene transfer, oncolysis, and vaccination (63–65). However, their successful use in humans requires surmounting a series of problems, among them the need to reprogram the natural tropism of the vector. A whole field of AdV retargeting by modification of outer capsid proteins is devoted to solve this problem (66). Further characterization of the LAdV-2 receptor binding properties may open the possibility to target tissues and cell types inaccessible at present to existing vectors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by grants from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain (BFU2010-16382 and BFU2013-41249-P to C.S.M., BFU2011-24843 to M.J.v.R., and the Spanish Interdisciplinary Network on the Biophysics of Viruses [Biofivinet], FIS2011-16090-E), the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA K100163 to M.B.), the Morris Animal Foundation (to R.E.M), and a Spanish MICINN-German DAAD travel grant (DE2009-0019 to C.S.M. and R.E.M.). R.M.-C. was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III of Spain (FI08/00035), as well as an EMBO short-term fellowship (ASTF 445-2009). T.H.N. is a recipient of a Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology-Spanish CSIC joint fellowship.

We gratefully acknowledge María Angeles Fernández-Estévez, Silvia Juárez, and Rosana Navajas (CNB-CSIC) for expert technical help.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 23 July 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Harrach B, Benkő M, Both G, Brown M, Davison A, Echavarría M, Hess M, Jones M, Kajon A, Lehmkuhl H, Mautner V, Mittal S, Wadell G. 2011. Family Adenoviridae, p 95–111 In King A, Adams M, Carstens E, Lefkowitz E. (ed), Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses. Ninth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benkő M, Harrach B. 2003. Molecular evolution of adenoviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 272:3–36. 10.1007/978-3-662-05597-7_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benkő M, Doszpoly A. 2011. Ichtadenovirus. Adenoviridae, p 29–32 In Tidona CA, Darai G. (ed), The Springer index of viruses. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovács ER, Benkő M. 2011. Complete sequence of raptor adenovirus 1 confirms the characteristic genome organization of siadenoviruses. Infect. Genet. Evol. 11:1058–1065. 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farkas SL, Harrach B, Benkő M. 2008. Completion of the genome analysis of snake adenovirus type 1, a representative of the reptilian lineage within the novel genus Atadenovirus. Virus Res. 132:132–139. 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benkő M, Harrach B. 1998. A proposal for a new (third) genus within the family Adenoviridae. Arch. Virol. 143:829–837. 10.1007/s007050050335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrach B. 2000. Reptile adenoviruses in cattle? Acta Vet. Hung. 48:485–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benkő M, Élő P, Ursu K, Ahne W, LaPatra ES, Thomson D, Harrach B. 2002. First molecular evidence for the existence of distinct fish and snake adenoviruses. J. Virol. 76:10056–10059. 10.1128/JVI.76.19.10056-10059.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vrati S, Brookes DE, Strike P, Khatri A, Boyle DB, Both GW. 1996. Unique genome arrangement of an ovine adenovirus: identification of new proteins and proteinase cleavage sites. Virology 220:186–199. 10.1006/viro.1996.0299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farkas SL, Benkő M, Elő P, Ursu K, Dán A, Ahne W, Harrach B. 2002. Genomic and phylogenetic analyses of an adenovirus isolated from a corn snake (Elaphe guttata) imply a common origin with members of the proposed new genus Atadenovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2403–2410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wellehan JF, Johnson AJ, Harrach B, Benkő M, Pessier AP, Johnson CM, Garner MM, Childress A, Jacobson ER. 2004. Detection and analysis of six lizard adenoviruses by consensus primer PCR provides further evidence of a reptilian origin for the atadenoviruses. J. Virol. 78:13366–13369. 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13366-13369.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papp T, Fledelius B, Schmidt V, Kaján GL, Marschang RE. 2009. PCR-sequence characterization of new adenoviruses found in reptiles and the first successful isolation of a lizard adenovirus. Vet. Microbiol. 134:233–240. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyndman T, Shilton CM. 2011. Molecular detection of two adenoviruses associated with disease in Australian lizards. Aust. Vet. J. 89:232–235. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2011.00712.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davison AJ, Benkő M, Harrach B. 2003. Genetic content and evolution of adenoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 84:2895–2908. 10.1099/vir.0.19497-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorman JJ, Wallis TP, Whelan DA, Shaw J, Both GW. 2005. LH3, a “homologue” of the mastadenoviral E1B 55-kDa protein is a structural protein of atadenoviruses. Virology 342:159–166. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pantelic RS, Lockett LJ, Rothnagel R, Hankamer B, Both GW. 2008. Cryoelectron microscopy map of Atadenovirus reveals cross-genus structural differences from human adenovirus. J. Virol. 82:7346–7356. 10.1128/JVI.00764-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kidd AH, Chroboczek J, Cusack S, Ruigrok RWH. 1993. Adenovirus type 40 virions contain two distinct fibers. Virology 192:73–84. 10.1006/viro.1993.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovács GM, Harrach B, Zakhartchouk AN, Davison AJ. 2005. Complete genome sequence of simian adenovirus 1: an Old World monkey adenovirus with two fiber genes. J. Gen. Virol. 86:1681–1686. 10.1099/vir.0.80757-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song JD, Liu XL, Chen DL, Zou XH, Wang M, Qu JG, Lu ZZ, Hung T. 2012. Human adenovirus type 41 possesses different amount of short and long fibers in the virion. Virology 432:336–342. 10.1016/j.virol.2012.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Favier A-L, Schoehn G, Jaquinod M, Harsi C, Chroboczek J. 2002. Structural studies of human enteric adenovirus type 41. Virology 293:75–85. 10.1006/viro.2001.1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiocca S, Kurzbauer R, Schaffner G, Baker A, Mautner V, Cotten M. 1996. The complete DNA sequence and genomic organization of the avian adenovirus CELO. J. Virol. 70:2939–2949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaján GL, Davison AJ, Palya V, Harrach B, Benkő M. 2012. Genome sequence of a waterfowl aviadenovirus, goose adenovirus 4. J. Gen. Virol. 93:2457–2465. 10.1099/vir.0.042028-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hess M, Cuzange A, Ruigrok RWH, Chroboczek J, Jacrot B. 1995. The avian adenovirus penton: two fibres and one base. J. Mol. Biol. 252:379–385. 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marek A, Nolte V, Schachner A, Berger E, Schlotterer C, Hess M. 2012. Two fiber genes of nearly equal lengths are a common and distinctive feature of Fowl adenovirus C members. Vet. Microbiol. 156:411–417. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zubieta C, Schoehn G, Chroboczek J, Cusack S. 2005. The structure of the human adenovirus 2 penton. Mol. Cell 17:121–135. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu H, Wu L, Zhou ZH. 2011. Model of the trimeric fiber and its interactions with the pentameric penton base of human adenovirus by cryo-electron microscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 406:764–774. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green NM, Wrigley NG, Russell WC, Martin SR, McLachlan AD. 1983. Evidence for a repeating cross-β sheet structure in the adenovirus fibre. EMBO J. 2:1357–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Raaij MJ, Mitraki A, Lavigne G, Cusack S. 1999. A triple β-spiral in the adenovirus fibre shaft reveals a new structural motif for a fibrous protein. Nature 401:935–938. 10.1038/44880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chroboczek J, Ruigrok RW, Cusack S. 1995. Adenovirus fiber. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 199:163–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Louis N, Fender P, Barge A, Kitts P, Chroboczek J. 1994. Cell-binding domain of adenovirus serotype 2 fiber. J. Virol. 68:4104–4106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wickham TJ, Mathias P, Cheresh DA, Nemerow GR. 1993. Integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell 73:309–319. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90231-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu E, Pache L, Von Seggern DJ, Mullen TM, Mikyas Y, Stewart PL, Nemerow GR. 2003. Flexibility of the adenovirus fiber is required for efficient receptor interaction. J. Virol. 77:7225–7235. 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7225-7235.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shayakhmetov DM, Lieber A. 2000. Dependence of adenovirus infectivity on length of the fiber shaft domain. J. Virol. 74:10274–10286. 10.1128/JVI.74.22.10274-10286.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobson ER, Gardiner CH. 1990. Adeno-like virus in esophageal and tracheal mucosa of a Jackson's chameleon (Chamaeleo jacksoni). Vet. Pathol. 27:210–212. 10.1177/030098589002700313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Julian AF, Durham PJ. 1982. Adenoviral hepatitis in a female bearded dragon (Amphibolurus barbatus). N. Z. Vet. J. 30:59–60. 10.1080/00480169.1982.34880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinsel MJ, Barbiers RB, Manharth A, Murnane RD. 1997. Small intestinal adeno-like virus in a mountain chameleon (Chameleo montium). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 28:498–500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Essbauer S, Ahne W. 2001. Viruses of lower vertebrates. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health 48:403–475. 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2001.00473.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marschang RE. 2011. Viruses infecting reptiles. Viruses 3:2087–2126. 10.3390/v3112087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Juhasz A, Ahne W. 1993. Physicochemical properties and cytopathogenicity of an adenovirus-like agent isolated from corn snake (Elaphe guttata). Arch. Virol. 130:429–439. 10.1007/BF01309671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogawa M, Ahne W, Essbauer S. 1992. Reptilian viruses: adenovirus-like agent isolated from royal python (Python regius). Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. B 39:732–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark HF, Cohen MM, Karzon DT. 1970. Characterization of reptilian cell lines established at incubation temperatures of 23 to 36 degrees. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 133:1039–1047. 10.3181/00379727-133-34622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maizel JV, Jr, White DO, Scharff MD. 1968. The polypeptides of adenovirus. I. Evidence for multiple protein components in the virion and a comparison of types 2, 7A, and 12. Virology 36:115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doszpoly A, Wellehan JF, Jr, Childress AL, Tarján ZL, Kovács ER, Harrach B, Benkő M. 2013. Partial characterization of a new adenovirus lineage discovered in testudinoid turtles. Infect. Genet. Evol. 17:106–112. 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.03.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guindon S, Gascuel O. 2003. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52:696–704. 10.1080/10635150390235520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9:671–675. 10.1038/nmeth.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prage L, Pettersson U, Höglund S, Lonberg-Holm K, Philipson L. 1970. Structural proteins of adenoviruses. IV. Sequential degradation of the adenovirus type 2 virion. Virology 42:341–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M. 1996. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68:850–858. 10.1021/ac950914h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Both GW. 2011. Atadenovirus. Adenoviridae, p 1–12 In Tidona CA, Darai G. (ed), The Springer index of viruses. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schöndorf E, Bahr U, Handermann M, Darai G. 2003. Characterization of the complete genome of the Tupaia (tree shrew) adenovirus. J. Virol. 77:4345–4356. 10.1128/JVI.77.7.4345-4356.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farkas SL, Harrach B, Benkő M. 2008. Completion of the genome analysis of snake adenovirus type 1, a representative of the reptilian lineage within the novel genus Atadenovirus. Virus Res. 132:132–139. 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hasson TB, Ornelles DA, Shenk T. 1992. Adenovirus L1 52- and 55-kilodalton proteins are present within assembling virions and colocalize with nuclear structures distinct from replication centers. J. Virol. 66:6133–6142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pérez-Berná AJ, Mangel WF, McGrath WJ, Graziano V, Flint SJ, San Martín C. 2014. Processing of the L1 52/55k protein by the adenovirus protease: a new substrate and new insights into virion maturation. J. Virol. 88:1513–1524. 10.1128/JVI.02884-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Webster A, Russell S, Talbot P, Russell WC, Kemp GD. 1989. Characterization of the adenovirus proteinase: substrate specificity. J. Gen. Virol. 70:3225–3234. 10.1099/0022-1317-70-12-3225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gelderblom H, Maichle-Lauppe I. 1982. The fibers of fowl adenoviruses. Arch. Virol. 72:289–298. 10.1007/BF01315225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guardado-Calvo P, Llamas-Saiz AL, Fox GC, Langlois P, van Raaij MJ. 2007. Structure of the C-terminal head domain of the fowl adenovirus type 1 long fiber. J. Gen. Virol. 88:2407–2416. 10.1099/vir.0.82845-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.El Bakkouri M, Seiradake E, Cusack S, Ruigrok RW, Schoehn G. 2008. Structure of the C-terminal head domain of the fowl adenovirus type 1 short fibre. Virology 378:169–176. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh AK, Menendez-Conejero R, San Martin C, van Raaij MJ. 2013. Crystallization of the C-terminal domain of the fibre protein from snake adenovirus 1, an atadenovirus. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 69:1374–1379. 10.1107/S1744309113029308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ishihama Y, Oda Y, Tabata T, Sato T, Nagasu T, Rappsilber J, Mann M. 2005. Exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) for estimation of absolute protein amount in proteomics by the number of sequenced peptides per protein. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 4:1265–1272. 10.1074/mcp.M500061-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arnberg N. 2012. Adenovirus receptors: implications for targeting of viral vectors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 33:442–448. 10.1016/j.tips.2012.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roelvink PW, Lizonova A, Lee JGM, Li Y, Bergelson JM, Finberg RW, Brough DE, Kovesdi I, Wickham TJ. 1998. The coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor protein can function as a cellular attachment protein for adenovirus serotypes from subgroups A, C, D, E, and F. J. Virol. 72:7909–7915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tan PK, Michou AI, Bergelson JM, Cotten M. 2001. Defining CAR as a cellular receptor for the avian adenovirus CELO using a genetic analysis of the two viral fibre proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 82:1465–1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seki T, Dmitriev I, Kashentseva E, Takayama K, Rots M, Suzuki K, Curiel DT. 2002. Artificial extension of the adenovirus fiber shaft inhibits infectivity in coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor-positive cell lines. J. Virol. 76:1100–1108. 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1100-1108.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lasaro MO, Ertl HC. 2009. New insights on adenovirus as vaccine vectors. Mol. Ther. 17:1333–1339. 10.1038/mt.2009.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gonçalves MAFV, de Vries AAF. 2006. Adenovirus: from foe to friend. Rev. Med. Virol. 16:167–186. 10.1002/rmv.494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamamoto M, Curiel DT. 2010. Current issues and future directions of oncolytic adenoviruses. Mol. Ther. 18:243–250. 10.1038/mt.2009.266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khare R, Chen CY, Weaver EA, Barry MA. 2011. Advances and future challenges in adenoviral vector pharmacology and targeting. Curr. Gene Ther. 11:241–258. 10.2174/156652311796150363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. 1999. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis 20:3551–3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]