ABSTRACT

Rhesus macaque rhadinovirus (RRV) is a gammaherpesvirus of rhesus macaque (RM) monkeys that is closely related to human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)/Kaposi's Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), and it is capable of inducing diseases in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected RM that are similar to those seen in humans coinfected with HIV and HHV-8. Both HHV-8 and RRV encode viral CD200 (vCD200) molecules that are homologues of cellular CD200, a membrane glycoprotein that regulates immune responses and helps maintain immune homeostasis via interactions with the CD200 receptor (CD200R). Though the functions of RRV and HHV-8 vCD200 molecules have been examined in vitro, the precise roles that these viral proteins play during in vivo infection remain unknown. Thus, to address the contributions of RRV vCD200 to immune regulation and disease in vivo, we generated a form of RRV that lacked expression of vCD200 for use in infection studies in RM. Our data indicated that RRV vCD200 expression limits immune responses against RRV at early times postinfection and also impacts viral loads, but it does not appear to have significant effects on disease development. Further, examination of the distribution pattern of CD200R in RM indicated that this receptor is expressed on a majority of cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, including B and T cells, suggesting potentially wider regulatory capabilities for both vCD200 and CD200 that are not strictly limited to myeloid lineage cells. In addition, we also demonstrate that RRV infection affects CD200R expression levels in vivo, although vCD200 expression does not play a role in this phenomenon.

IMPORTANCE Cellular CD200 and its receptor, CD200R, compose a pathway that is important in regulating immune responses and is known to play a role in a variety of human diseases. A number of pathogens have been found to modulate the CD200-CD200R pathway during infection, including human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), the causative agent of Kaposi's sarcoma and B cell neoplasms in AIDS patients, and a closely related primate virus, rhesus macaque rhadinovirus (RRV), which infects and induces disease in rhesus macaque monkeys. HHV-8 and RRV encode homologues of CD200, termed vCD200, which are thought to play a role in preventing immune responses against these viruses. However, neither molecule has been studied in an in vivo model of infection to address their actual contributions to immunoregulation and disease. Here we report findings from our studies in which we analyzed the properties of a mutant form of RRV that lacks vCD200 expression in infected rhesus macaques.

INTRODUCTION

CD200 is an immunomodulatory protein known to be important in the regulation and fine control of immune responses, and it is thought to play a critical role in helping to maintain immune homeostasis. CD200 is a membrane glycoprotein that is capable of inducing signaling in cells expressing its cognate cell surface receptor, the CD200 receptor (CD200R). Both CD200 and CD200R are single transmembrane type 1 proteins of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily and possess two extracellular Ig-like domains. CD200 itself contains a short cytoplasmic tail not capable of signaling, while CD200R possesses a cytoplasmic tail with a signaling motif (NPXY) that can become tyrosine phosphorylated upon CD200 binding, thus initiating downstream signaling events in cells expressing the receptor. CD200/CD200R has been extensively studied in mice and humans (1, 2), and in general, it has been found that CD200 is broadly expressed on numerous cell types, while the distribution of CD200R is often described as being restricted mainly to cells of the myeloid lineage (3–5). However, more recently, a wider array of cell types have been found to express CD200R, including T and B lymphocytes, further expanding the possible repertoire of immune cells regulated by CD200 (2, 5–7). The overall view of the CD200-CD200R interaction is that of an immune-inhibitory mechanism, with signaling events in CD200R-expressing cells as a result of CD200 binding leading to an inhibition of cellular activation, decreased cytokine production, and overall diminished inflammatory responses (1, 2). Although CD200 largely functions as an inhibitory molecule, CD200R signaling has also been found to be potentially activating in some scenarios (8), which implies that more complicated patterns of regulation are likely to exist, depending on the exact context and timing of the interaction, that allow for further levels of fine-tuning of immune responses.

Due to its central role in negatively regulating immune cells and inflammatory responses, the involvement of CD200/CD200R in a variety of human diseases has been widely suggested. Indeed, the spectrum of diseases potentially affected by CD200 is quite broad, including autoimmune diseases such as arthritis (9), neurodegenerative disorders such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, and Alzheimer's disease (10–12), and a wide variety of human cancers, ranging from solid tumors to hematopoietic disorders (2, 13–15). With regard to its role in cancer, increased CD200 expression by tumor cells is thought to allow for their enhanced growth and survival (16), and the potential significance of this is underscored by the fact that CD200 expression has been demonstrated to be a strong prognostic marker in some human malignancies, such as acute myeloid leukemia and multiple myeloma (17, 18).

The CD200/CD200R pathway has also been found to be an important regulator of host immune responses during in vivo infection with a variety of pathogens, including bacteria, parasites, and viruses (19–25). Though increased CD200R signaling is generally envisioned to be beneficial to the host in situations where it plays a role in dampening potentially damaging inflammatory responses induced by infection, in some cases it has been found that CD200-mediated inhibition of immune responses can actually result in a decrease in pathogen clearance and increased disease development. For example, in vivo studies have indicated that the CD200-CD200R interaction is critical for limiting inflammation and lung disease in mice infected with influenza virus (20, 21), while alternatively, CD200R activation is capable of enhancing replication and virulence of pathogens such as Leishmania amazonensis (26) and mouse hepatitis coronavirus (MHV) (22). Further, although immunomodulation seems to be the main mechanism by which CD200/CD200R regulates infectious diseases, recent studies of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) infection in mice also suggest that CD200R may be capable of directly impacting viral replication independently of its effects on inflammatory responses (27). Thus, the contributions of CD200/CD200R signaling to the regulation of microbial infections and disease have the potential to be rather complex and are also likely specific to the pathogen and host species in question.

The importance of the CD200/CD200R pathway to immunoregulation during microbial infection is also underscored by the fact that some pathogens have been shown to affect expression levels of CD200 and CD200R in vivo (19, 21, 23, 25), and further, that some viruses actually encode homologues of cellular CD200 that are capable of regulating CD200R signaling. Specifically, some members of the Poxviridae, Adenoviridae, and Herpesviridae families of double-stranded DNA viruses have been found to encode viral CD200 (vCD200) proteins (7, 28–31), and examination of the function of several of these molecules has indicated that they possess the potential to bind to CD200R and regulate cells expressing this receptor (7, 28, 29, 32–35). The most extensively studied vCD200 molecule is that encoded by HHV-8/Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), a gammaherpesvirus that is commonly associated with development of diseases in humans coinfected with HIV, including Kaposi's sarcoma, B cell lymphoproliferative disorders (LPD), primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and multicentric Castleman's disease (MCD), and also some non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (36–39).

In several in vitro studies, HHV-8 vCD200 has been shown to inhibit the activation of macrophages (29), basophils (7), neutrophils (40), and more recently, antigen-specific T cells (41), strongly suggesting that this molecule may play a central role in inhibiting the development of immune responses against HHV-8 in vivo. Interestingly, however, HHV-8 vCD200 has also been shown to possess stimulatory properties under certain experimental conditions, findings that indicate the activation status of the target cell may help determine whether vCD200 binding induces a pro- or anti-inflammatory response (34, 42). Despite this information, it is important to note that due to the lack of a suitable animal model that supports HHV-8 infection and disease development, HHV-8 vCD200 has only been examined alone in in vitro models of expression. Thus, although a possible role for gammaherpesvirus vCD200 molecules in regulating immune responses and disease development in vivo has been proposed, this has never been specifically investigated.

Rhesus macaque rhadinovirus (RRV) is a gammaherpesvirus of rhesus macaques (RM) that is closely related to HHV-8 and encodes a vCD200 homologue with similarity to HHV-8 vCD200 (31). Open reading frame R15 (ORFR15) encodes the RRV vCD200 protein and is transcribed as the first ORF in a bicistronic transcript that also contains the downstream ORF74, which encodes the viral G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) (43). Similar to cellular CD200 and HHV-8 vCD200, the full-length form of RRV vCD200 exists as a membrane-bound molecule and possesses two extracellular IgG domains, a transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic tail. In addition to the full-length membrane-bound form of RRV vCD200, we have also previously identified a secreted form of this protein that lacks the transmembrane domain and is simultaneously produced in RRV-infected cells as the result of unique transcript splicing patterns for R15-ORF74 (43). Prior in vitro studies of RRV vCD200 indicated that this protein functions similarly to HHV-8 vCD200 and is capable of inhibiting the activation of macrophages in vitro (35); however, the functions of RRV vCD200 during in vivo infection are yet to be examined.

Importantly, RRV is capable of inducing diseases in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected RM that display similarity to those observed in humans coinfected with HIV and HHV-8, including B cell hyperplasia, B cell lymphoma, an LPD that resembles MCD, and retroperitoneal fibromatosis (44, 45). Further, it has been demonstrated that RRV naturally infects B cells in vivo, where the virus is capable of establishing latency (46). The availability of an infectious and pathogenic RRV bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone also provides the ability to rapidly generate recombinant forms of RRV (47, 48) and allows for the direct testing of the roles of individual viral genes and putative pathogenic determinants in RRV-associated disease (49). Thus, RRV provides a highly relevant model system in which the contributions of gammaherpesvirus vCD200 molecules to immunoregulation and pathogenesis can be examined during in vivo infection.

In order to directly assess the contributions of RRV vCD200 to infection, pathogenesis, and immunoregulation in vivo, we generated a mutant form of RRV that lacks expression of vCD200 and performed comparative experimental infection studies in RM. Our findings indicate that RRV vCD200 expression limits T cell responses at early times postinfection, while also having a negative impact on viral loads. However, expression of vCD200 does not appear to have observable effects on disease development in RRV-infected animals. In addition, analysis of the distribution pattern of CD200R in RM indicates that CD200R is expressed on a majority of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), including B and T cells, suggesting a wider regulatory role for both CD200 and vCD200 in immune function in vivo that is not strictly limited to myeloid lineage cells. We also demonstrate that RRV infection affects CD200R expression levels in RM PBMC, though vCD200 expression does not appear to play a role in this phenomenon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus production.

Primary rhesus fibroblasts (RF) were grown in Dulbecco's modification of Eagle's medium (DMEM; Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Logan, UT). Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were grown in Ham's F-12-K medium (Mediatech) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. RRV stocks were grown in primary rhesus fibroblasts and were purified and concentrated by centrifugation through a 30% sorbitol cushion. Titers of viral stocks were assessed by plaque assay on primary rhesus fibroblasts. The wild-type (WT) BAC RRV used in these studies has been described previously (47).

Construction of a vCD200 nonsense (vCD200 NS) mutant RRV.

To generate a mutant form of RRV lacking expression of vCD200, we utilized the RRV17577 BAC (47) in conjunction with a galK positive/negative selection system (50) to engineer stop codons into the 5′ sequence of R15 that prevent expression of vCD200 protein from R15-containing transcripts. Briefly, a clone of Escherichia coli strain SW105 containing the RRV17577 BAC was induced to express recombination genes and then electroporated with a DNA fragment containing the galK expression cassette flanked with RRV genomic sequence derived from either side of R15-ORF74. The primers utilized to generate this cassette include 40 nucleotides (nt) of RRV genomic sequence directly flanking either the 5′ end of the R15 start codon (nt 122826 to nt 122865) or the 3′ end of the ORF74 stop codon (nt 124992 to nt 124953), linked to sequence specific for amplification of the galK cassette from the plasmid pGalK (R15 5′-flanking primer sequence, 5′-CCGGGTGTTAAGCACCAACACCGACCGTGCGTTTTCAATTCCTGTTGACAATTAATCATCGGCA-3′; ORF74 3′-flanking primer sequence, 5′-AATGTACACAAACAATCCAACCAAGTGTCGCGTGAGTGTCTCAGCACTGTCCTGCTCCTT-3′; sequences homologous to the galK cassette sequence are underlined). Recombination of this PCR product with WT RRV BAC in E. coli results in the complete deletion of R15-ORF74 region and its replacement with galK expression cassette. To identify a clone with R15-ORF74 deleted, DNA was purified from BAC clones by standard alkaline lysis methods and digested with BamHI, samples were run on a 0.7% agarose gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and Southern blot analysis was performed using DNA probes specific to galK or RRV ORF74 sequence that were labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) by using a DIG-High Prime kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). A clone identified in this fashion was then picked, and the correct deletion of R15-ORF74 was confirmed by PCR and sequencing of the deleted region.

Next, a repair cassette containing the complete R15-ORF74 region with stop codons in all three reading frames of the 5′ coding region of R15 was generated by standard PCR-based mutagenesis with overlapping primer sets, using wild-type RRV17577 DNA as a template for PCR. This product also possesses ORF74 sequence engineered to possess a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag coding sequence at the C terminus and is flanked by 200 bp of RRV genomic sequence on either side of R15-ORF74 to allow for recombination with the R15-ORF74 galK knockout (KO) BAC. The primers used to amplify the 5′ region of R15 contained engineered base changes from nt 122866 to nt 122867 (AT to TA) that result in replacement of the R15 start codon with a TAG stop codon, as well as a single base change at nt 122882 (C to A) that results in the insertion of a stop codon (TAA) into the third reading frame of the sequence, while a TAA stop codon is naturally present in the second reading frame, from nt 122885 to nt 122887 (R15 stop forward primer, 5′-TCAATTTAGTCGGGAGGAATTAAATTAACGCTG-3′; R15 stop reverse primer, 5′-CAGCGTTAATTTAATTCCTCCCGACTAAATTGA-3′; the mutated R15 start codon is italicized, introduced base changes are in bold, and stop codons in all three reading frames are underlined). The primers used to insert the HA epitope tag at the C terminus of the ORF74 coding region contain the HA coding sequence directly before the TGA stop codon (ORF74+HA forward primer, 5′-TACCCATACGACGTCCCAGACTACGCTTGAGACACTCACGCGACACTT-3′; ORF74+HA reverse primer, 5′-AGCGTAGTCTGGGACGTCGTATGGGTATAAACTACCTGAAGTGGAAAA-3′; the HA epitope tag sequence is underlined and stop codon is italicized). The primers used to amplify the entire R15-ORF74 region with flanking sequence bind 200 bp upstream of R15 and 200 bp downstream of ORF74, and they also contain engineered restriction sites for cloning purposes (200 bp upstream R15+XhoI primer, 5′-CGCCTCGAGGTTAACCCGTAAATCTGGAAA-3′; 200 bp downstream ORF74+EcoRI, 5′-GCGAATTCTGACGTTCCACCCCTGGCAGT-3′; restriction sites are italicized and the RRV genomic sequence is underlined). The final 2.5-kbp product of the overlapping PCRs was purified, digested with XhoI and EcoRI, and ligated into plasmid pSP73 (Promega, Madison, WI) cut with the same enzymes, and a clone containing the insert was identified and sequenced. Relative to the WT RRV genomic sequence, the resulting mutated repair cassette contains the engineered stop mutations in the R15 sequence and the HA epitope tag sequence at the 3′ end of ORF74, as well as a single silent mutation at nt 31 of R15 (T to C), one single-base difference upstream of R15 (nt 122737, A to G), and two single-base differences in the intergenic region between R15 and ORF74 (nt 123759, C to T; nt 123810, A to G).

To generate a BAC clone containing stop codons in the R15 sequence, the mutated repair cassette was isolated from pSP73 by digestion with XhoI and EcoRI, gel purified, and used to electroporate competent SW105 E. coli containing the R15-ORF74 galK KO RRV BAC that had been induced to express recombination genes. An RRV BAC clone with the galK cassette replaced by the mutated R15-ORF74 repair cassette was then identified and DNA was purified. To confirm the correct insertion of the mutated repair cassette into this BAC clone, Southern blot analysis was performed by digesting purified BAC DNA with BamHI, running samples on a 0.7% agarose gel, transferring DNA to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probing with RRV ORF74 and galK-specific DNA probes that were labeled with digoxigenin. To further confirm the correct insertion of the repair cassette into this BAC clone, PCR was performed to amplify across the repaired region and the product was subjected to direct sequencing. This clone was denoted vCD200 nonsense (vCD200 NS) RRV BAC.

The resulting vCD200 NS RRV BAC clone was utilized to make infectious vCD200 NS virus by following methods described previously (47). Briefly, purified BAC DNA was transfected into primary rhesus fibroblasts, and the virus produced by these cells was collected and passed twice through primary rhesus fibroblasts transfected with a plasmid expressing CRE recombinase to allow removal of the BAC cassette via recombination of loxP sites within the BAC cassette. The resulting virus pool was then utilized in a plaque assay on primary rhesus fibroblasts, multiple plaque isolates were picked and grown in primary rhesus fibroblasts, and a BAC-derived virus isolate lacking the BAC cassette was identified via PCR screening. This virus was then subjected to two rounds of plaque purification, and a stock of the virus was grown in primary rhesus fibroblasts and purified twice by ultracentrifugation through a 30% sorbitol cushion. The purified BAC-derived mutant virus was denoted vCD200 nonsense (vCD200 NS) RRV.

Confirmation of the sequence and integrity of the entire vCD200 NS RRV genome was achieved by subjecting purified viral DNA to comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) using an RRV17577-specific array as described previously (47).

To demonstrate lack of expression of vCD200 protein from vCD200 NS N.S., primary rhesus fibroblasts were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 with either vCD200 NS or WT BAC, lysates were collected after 72 h, and vCD200 was immunoprecipitated from equivalent amounts of each sample by using an RRV vCD200-specific mouse monoclonal antibody (35). Next, equivalent amounts of each sample were run on a 10% acrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and the membrane was probed using the same RRV vCD200 antibody used for immunoprecipitation. A sample of each lysate was also run on a 10% acrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with a mouse monoclonal antibody specific to RRV glycoprotein B (gB) to demonstrate equal infection levels by both viruses.

Experimental animal infections.

All aspects of the experimental animal studies were performed according to institutional guidelines for animal care and use at the Oregon National Primate Research Center, Beaverton, OR. Expanded-specific-pathogen-free (eSPF) juvenile RM sero-negative for RRV, rhesus cytomegalovirus, SIV, simian retrovirus type D, simian virus 40 (SV40), and herpes B virus were inoculated intravenously with 5 × 106 PFU of purified BAC-derived RRV. Four separate cohorts of animals were infected during the course of this study, with a total of 11 RM receiving WT BAC (animal numbers 25631, 25650, 24807, 24896, 24996, 21963, 26473, 29119, 27386, 29000, and 25617) and 12 RM receiving vCD200 NS (animal numbers 25608, 26001, 25639, 25645, 27003, 27009, 27011, 27100, 26430, 25662, 28902, and 28834). Cohort I animals were first inoculated intravenously with 5 ng of SIVmac239 p27 antigen containing cell-free supernatants, followed 7 weeks later by infection with WT BAC (animals 25631 and 25650) or vCD200 NS (animals 25608 and 26001). Cohort II animals were first infected with WT BAC (animals 24807, 24896, and 24996) or vCD200 NS (animals 25639 and 25645), followed 10 weeks later by infection with 5 ng of SIVmac239 p27 antigen-containing cell-free supernatants. Animals in cohorts III and IV were infected only with BAC-derived RRV. Cohort III consisted of animals that received WT BAC (animals 21963 and 26473) or vCD200 NS (animals 27003, 27009, 27011, and 27100); cohort IV was animals that received WT BAC (animals 29119, 27386, 29000, and 25617) or vCD200 NS (animals 26430, 25662, 28902, and 28834).

Whole blood (WB) and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples were collected from all animals at time points prior to and the day of infection (day 0) and then weekly thereafter for the duration of the study. PBMC were isolated from WB by centrifugation over lymphocyte separation medium (Mediatech, Manassas, VA). Total cells were isolated from BAL fluid samples by centrifugation followed by resuspension in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin (Pen/Strep). In addition to standard sampling procedures, cohort IV animals were also subjected to lymph node (LN) biopsies at days 0, 14, 21, and 28, as well as maximum blood draws at day 28.

Measurement of viral loads in whole blood.

To measure viral loads in infected RM, DNA was purified from WB by using a Puregene DNA purification kit (Gentra Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN), and 100 ng of DNA was analyzed by real-time PCR with a primer and probe set specific for RRV ORF3 (viral macrophage inflammatory protein [vMIP]). The sequences of the primers used were as follows: vMIP-1, 5′-CCTATGGGCTCCATGAGC-3′; vMIP-2, 5′-ATCGTCAATCAGGCTGCG-3′. The vMIP probe sequence was 5′-TCATCTGCCGCCACCCGGTTTA-3′. Reactions were run on an ABI Prism 7700 DNA sequence detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). To determine viral DNA loads in lymph node biopsy samples, LN samples were homogenized and total cells were collected and lysed with TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to isolate DNA. Equivalent volumes of LN DNA samples were then subjected to real-time PCR analysis with RRV vMIP (RRV genome copies) and RM glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) primer and probe sets. RRV genome copy numbers were normalized to GAPDH copy numbers to determine the relative amount of RRV genome in each sample of DNA. Levels of infectious virus in PBMC from infected RM were also assessed by coculture analysis with primary rhesus fibroblasts as described previously (47).

Magnetic bead isolation and real-time PCR analysis of PBMC subsets.

Maximum blood draws were obtained from cohort IV animals at day 28 postinfection, PBMCs were isolated from WB, and 4 × 107 to 10 × 107 PBMCs were subjected to separation using magnetic beads specific for nonhuman primate CD20, CD3, and CD14 (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). After separation, cell samples were counted and divided equally into triplicates, and DNA was isolated from each sample by using an ArchivePure DNA isolation kit (5 Prime Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Each triplicate DNA sample was subjected to real-time PCR analysis to determine RRV genome copy number (RRV vMIP primers and probe) and GAPDH copy numbers (GAPDH primer and probe set), and the ratio of RRV genome copies to GAPDH copies was then calculated. The resulting triplicate values were then averaged to determine the overall RRV genome copies/GAPDH copy number ratio for each cell subset.

Flow cytometry analysis.

Where indicated, PBMC and BAL cells were stained with surface antibodies directed against CD20 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA), IgD (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL), and CD27 (BioLegend) to delineate total, naive, marginal zone-like (MZ-like), and memory B cells, or with surface antibodies directed against CD4 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), CD8β (Beckman Coulter, Inc.), CD28 (BioLegend), and CD95 (BioLegend) to delineate total CD4 and CD8 T cells, as well as central memory (CM) and effector memory (EM) T cell subsets. Antibodies directed against CD14 (Biolegend) and HLA-DR (Biolegend) were used to define monocytes and dendritic cells (DCs), respectively. For Ki67 analysis, surface-stained cells were fixed and the nuclear membrane was permeabilized with permeabilization wash buffer (BioLegend) before further staining with an antibody directed against Ki67 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Intracellular cytokine staining (ICCS) was carried out as previously described (49). Briefly, PBMC and BAL cells were stimulated with dimethyl sulfoxide (negative control), WT BAC RRV (MOI, 1), or anti-CD3 (positive control) overnight, and then brefeldin A was added for an additional 6 h. Next, cells were stained with surface antibodies directed against CD4, CD8β, CD28, and CD95, and cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with an antibody directed against gamma interferon (IFN-γ; eBioscience).

CD200R expression analysis was performed with PBMC purified from preinfection WB samples (day −7 and day 0) obtained from all animals in cohorts II, III, and IV. Samples from RM in cohort IV were also stained throughout the study period at defined weekly sampling time points. PBMC were stained for CD200R expression by using an anti-human CD200R antibody that cross-reacts with RM CD200R (clone OX-108; BioLegend), with gating for each sample adjusted above background staining levels using an isotype-matched control antibody (IgG1, κ; BioLegend). Cells stained for CD200R were also simultaneously stained with surface antibodies to determine the percentage of each cell type within PBMC expressing the receptor. All samples were acquired using an LSRII instrument (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA), and data were analyzed by using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Measurement of RRV-specific antibody responses.

To measure anti-RRV antibody responses, plasma was collected weekly from infected RM, and antiviral IgG levels were measured in circulating plasma by using a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (49). For these experiments, serial 3-fold dilutions of plasma were incubated in duplicate on RRV virus lysate-coated ELISA plates for 1 h prior to washing, staining with detection reagents (horseradish peroxidase [HRP]-conjugated anti-IgG), and addition of chromogen substrate to allow for detection and quantitation of bound antibody molecules. Log-log transformation of the linear portion of the curve was then performed, and 0.15 optical density units were used as the cutoff point to calculate endpoint titers. Each plate included a positive control sample used to normalize the ELISA titers between assays and a negative control sample to ensure the specificity of the assay conditions.

Immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, and immunofluorescence.

Tissue samples from a pancreatic mass identified in animal 26001 were collected at necropsy, and sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue were stained using methods described previously (45). Immunohistochemistry tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to define tissue architecture. In situ hybridization was performed with biotinylated RRV cosmid DNA, visualized with diaminobenzidine, and stained with Gill's hematoxylin counterstain. Immunofluorescence was performed with an anti-RRV viral interleukin-6 (vIL-6) mouse monoclonal antibody to identify RRV, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody to identify B cells, and Hoechst dye to stain nuclei. Stained tissue sections were examined using a Zeiss Axioscope 2 Plus microscope equipped with a Zeiss Axiocam camera (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Images were acquired using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) or OpenLab 4.0.3 (Improvision, Waltham, MA) and were processed with Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

RM CD200R cloning and analysis of RRV vCD200 binding to CD200R.

cDNA expressing full-length RM CD200R was isolated from total RNA derived from PBMC from an eSPF RM (animal number 30656) by using a SuperScript III One-Step reverse transcription-PCR kit (Invitrogen) and primers specific for the 5′ and 3′ ends of the coding sequence of the predicted Macaca mulatta cell surface glycoprotein CD200 receptor 1-like, transcript variant 1 mRNA (GenBank accession number XM_002802646). Primers were engineered to contain restriction sites for cloning purposes (RM CD200R 5′ primer plus XbaI, 5′-GTTCTAGAATGCTCTGCCCTTGGAGAAC-3′; RM CD200R 3′ primer plus XhoI, 5′-ATCTCGAGTTATAAAGTATGGAGGTCTG-3′; restriction sites are italicized, the genomic sequence is underlined, and start and stop codons are in bold), and the resulting product was cloned into expression vector pCDNA3.1(-) (Invitrogen) and sequenced to confirm its identity. This cDNA clone was found to encode a protein with 98% amino acid identity to the predicted RM CD200R1 protein. The sequence of this cDNA clone is available in GenBank under accession number KM030065. CHO cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1(-) expressing RM CD200R, or empty vector as a control, by using TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio, Madison, WI). Cells were incubated for 48 h, detached using 10 mM EDTA, stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibody against CD200R (clone OX-108; BioLegend), and incubated with 125 ng of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled recombinant RRV vCD200 protein fused in frame to human IgG1 (vCD200-Fc) or 125 ng of FITC-labeled human Fc protein as a control. RRV vCD200-Fc protein was produced and purified as described previously (35), and human IgG Fc control protein was obtained from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Fc proteins were labeled by using a FITC conjugation kit (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry by using an LSRII instrument (BD Bioscience) and FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Statistical analysis.

Unpaired t tests were performed with Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Generation of vCD200 nonsense mutant RRV.

To generate a form of RRV lacking expression of vCD200, we utilized the RRV17577 BAC (47) in conjunction with the galK recombination system (50) to introduce stop mutations into the RRV genome that prevented vCD200 protein expression from transcripts containing R15 sequence. Since R15 is transcribed during RRV infection as the first ORF of a spliced bicistronic message with the downstream ORF74 that encodes the viral GPCR (43), the complete R15-ORF74 region was initially deleted from the RRV genome and replaced with a galK cassette, resulting in the isolation of an R15-ORF74 galK KO BAC clone that served as a target for insertion of mutated forms of R15-ORF74 sequence into the viral genome (Fig. 1A). To generate a vCD200 nonsense (vCD200 NS) RRV BAC, a repair cassette encompassing the entire R15-ORF74 region, and containing stop codons in all three reading frames in the 5′ region of R15 was generated by PCR-based mutagenesis for use in recombination with the R15-ORF74 galK KO BAC clone. The start codon of R15 was mutated to a stop codon (TGA) in the cassette, thus preventing vCD200 production from R15 upon insertion of this sequence into the viral genome. Further, a single base mutation was also made in the third reading frame of R15 to introduce a stop codon (TAC to TAA), while the second reading frame contained a naturally occurring stop codon (TAA), ensuring the lack of protein translation initiation from the 5′ region of R15 sequence. In addition, the ORF74 sequence was engineered to encode an HA epitope tag at the C terminus of the vGPCR for detection purposes, and sequence directly flanking either side of R15-ORF74 was also included to allow for recombination with the R15-ORF74 galK KO BAC clone. The resulting PCR product was cloned and sequenced, and the repair cassette was then isolated by restriction digestion and purified for use in recombination with the R15-ORF74 galK KO BAC. Following recombination in E. coli, galK-negative BAC clones were identified, and BAC DNA was isolated and screened for the presence of the mutated R15-ORF74 sequence by restriction digestion and Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1B). PCR and direct sequencing across the R15-ORF74 region also confirmed the correct insertion of the mutated R15-ORF74 cassette (data not shown). A single BAC clone identified in this fashion was then picked, and purified BAC DNA from this clone was transfected into primary RF to produce infectious virus. After obtaining vCD200 NS virus, the BAC cassette was removed from the genome by passage of the virus through RF transfected with a plasmid expressing CRE recombinase, resulting in the deletion of the BAC cassette and leaving a single loxP site at the location of BAC cassette insertion. The resulting vCD200 NS virus was then plaque purified in order to obtain a single purified viral isolate. In order to confirm the sequence of the entire viral genome, viral DNA was purified from this isolate for analysis via comparative genome hybridization using methods described previously (47). This analysis revealed that aside from the anticipated nucleotide changes resulting from insertion of the R15-ORF74 repair cassette, no other mutations were present in the remainder of the viral genome when directly compared to the genomic sequence of WT BAC-derived RRV (data not shown).

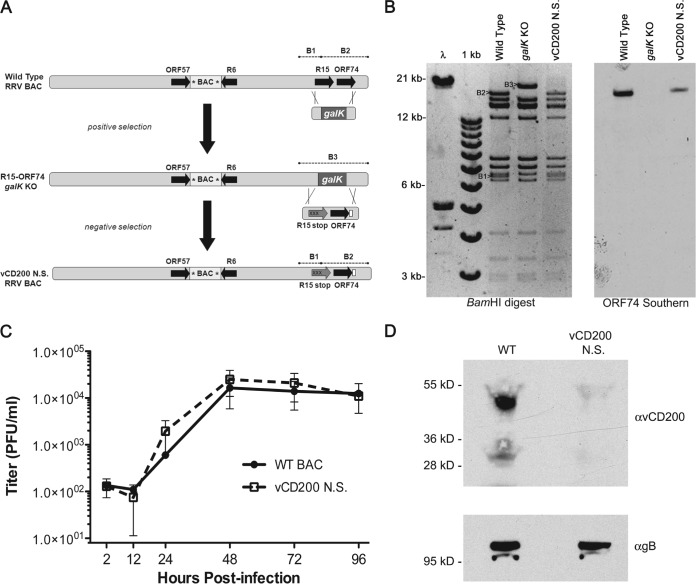

FIG 1.

Generation of a vCD200 NS BAC-derived virus. (A) General overview of the strategy utilized to introduce stop mutations into the R15 sequence of RRV by using the RRV BAC and galK selection system. The removal of R15-ORF74 was accomplished by targeting this region for deletion with a positive selection step with a galK cassette containing 40 bp of genomic flanking sequence from either side of the respective ORFs, resulting in an R15-ORF74 galK knockout BAC clone that then served as a target for a negative selection with an R15-ORF74 repair cassette containing 3 stop mutations in the 5′ region of R15 (Xs) and an HA tag at the 3′ end of ORF74 (white box). The location of the BAC cassette within the RRV BAC is indicated and loxP sites are denoted by asterisks, while dashed lines indicate BamHI restriction fragments in the R15-ORF74 region. (B) Restriction enzyme digestion and Southern blot analysis of RRV BAC vCD200 NS clone. Insertion of a galK cassette into the RRV BAC results in loss of a BamHI site located within R15 and the fusion of restriction fragments B1 and B2 into the larger fragment B3, while replacement of galK with the mutated R15-ORF74 repair cassette restores the digestion pattern seen in WT RRV BAC DNA. Southern blot analysis of the digested DNA with an ORF74-specific probe demonstrated the loss of the R15-ORF74 genomic sequence in the galK KO clone and restoration of this sequence in the repaired vCD200 NS BAC clone. (C) Single-step growth curve analysis of vCD200 NS virus in primary rhesus fibroblasts. Cells were infected at an MOI of 2.5, and samples were harvested at the indicated time points for plaque assay analysis on primary rhesus fibroblasts. (D) Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis of vCD200 expression in WT BAC- and vCD200 NS-infected rhesus fibroblasts. Lysates from infected RF were immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal antibody directed against RRV vCD200 and subjected to Western blot analysis with the same antibody (top). Equivalent amounts of each lysate were also subjected to Western blot analysis with a monoclonal antibody directed against RRV gB as a control (bottom). The predominant band of ∼50 kDa corresponds to the predicted glycosylated form of vCD200, while the ∼30-kDa product represents the core unmodified vCD200 protein.

To confirm that the introduced nucleotide changes in the R15-ORF74 region did not alter the growth kinetics of RRV, a single-step in vitro growth curve was prepared for RF. Results from this indicated that the vCD200 NS virus grows with similar kinetics to WT BAC-derived RRV in vitro (Fig. 1C). Finally, to demonstrate that replacement of the R15 start codon with a stop codon does in fact prevent expression of vCD200, RF were infected with WT BAC- or vCD200 NS BAC-derived virus, and lysates were collected and analyzed for the presence of vCD200 protein. These results indicated that vCD200 protein were detected in RF infected with WT BAC, while vCD200 was not produced in cells infected with vCD200 NS, confirming that the mutated virus no longer expressed any form of vCD200 (Fig. 1D).

In vivo infection studies.

To better understand the effects that vCD200 may have on RRV infection in vivo, four separate cohorts of RM were inoculated with either vCD200 NS (12 animals) or WT BAC (11 animals) (Table 1). In an attempt to assess the potential effects of vCD200 expression on RRV-associated disease development in the context of SIV infection, animals in cohort I and II were inoculated with SIVmac239 in addition to BAC-derived RRV viruses. Specifically, cohort I animals were infected first with SIVmac239, followed 7 weeks later by RRV, while cohort II animals received SIVmac239 10 weeks post-RRV infection. Although underlying immunosuppression due to prior SIV infection prevented the accurate assessment of immunological responses against RRV in cohort I, the latter infection protocol allowed for the examination of the primary anti-RRV immune response in immunocompetent animals, while also providing the opportunity to assess the potential for RRV-associated disease development in immunocompromised RM coinfected with SIV. Finally, animals in cohorts III and IV were infected only with BAC-derived RRV, and analyses in these groups were focused on the primary immune responses generated against RRV. All RRV inoculations were performed with 5 × 106 PFU of purified virus. WB and BAL samples were collected on a weekly basis at time points both pre- and postinfection, animals were observed daily for any apparent signs of disease associated with viral infection, and at time of necropsy, all animals were thoroughly examined for the presence of any abnormal pathologies.

TABLE 1.

Description of RM cohorts for the in vivo infection study

| Cohort | Animal no. | Sexa | Primary inoculation | Secondary inoculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 25631 | M | SIV | WT BAC |

| 25650 | M | SIV | WT BAC | |

| 25608 | M | SIV | vCD200 NS | |

| 26001 | M | SIV | vCD200 NS | |

| II | 24807 | M | WT BAC | SIV |

| 24896 | M | WT BAC | SIV | |

| 24996 | M | WT BAC | SIV | |

| 25639 | M | vCD200 NS | SIV | |

| 25645 | M | vCD200 NS | SIV | |

| III | 21963 | F | WT BAC | None |

| 26473 | M | WT BAC | None | |

| 27003 | M | vCD200 NS | None | |

| 27009 | F | vCD200 NS | None | |

| 27011 | M | vCD200 NS | None | |

| 27100 | F | vCD200 NS | None | |

| IV | 29119 | F | WT BAC | None |

| 27386 | F | WT BAC | None | |

| 29000 | F | WT BAC | None | |

| 25617 | F | WT BAC | None | |

| 26430 | F | vCD200 NS | None | |

| 25662 | F | vCD200 NS | None | |

| 28902 | F | vCD200 NS | None | |

| 28834 | F | vCD200 NS | None |

M, male; F, female.

Effects of vCD200 on RRV-associated disease development.

RRV infection of SIV+ RM can promote the development of HHV-8-like malignancies, including a lymphoproliferative disorder similar to MCD in humans, lymphoma, and less frequently RF, a KS-like proliferative mesenchymal lesion (44, 45). The time required for manifestation of these diseases in infected animals can be lengthy and is also quite variable, with the overall frequency of development being approximately 20 to 30%. Examination of disease manifestations in animals from cohorts I and II, which received SIV in addition to RRV, did not indicate any notable differences in the disease promoting potential between WT BAC or vCD200 NS viruses, with at least two animals infected with either of the viruses developing possible lymphoma by the end of the study period (WT BAC animals 24807 and 25650; vCD200 NS animals 25608 and 25645) (data not shown). In addition, staining of a pancreatic tissue mass that was identified at necropsy in animal 26001 demonstrated the development of a virus-associated B cell LPD in an RM infected with vCD200 NS (Fig. 2), further indicating that vCD200 expression is not required for the development of RRV-associated malignancies typically observed in RRV/SIV coinfected animals (44).

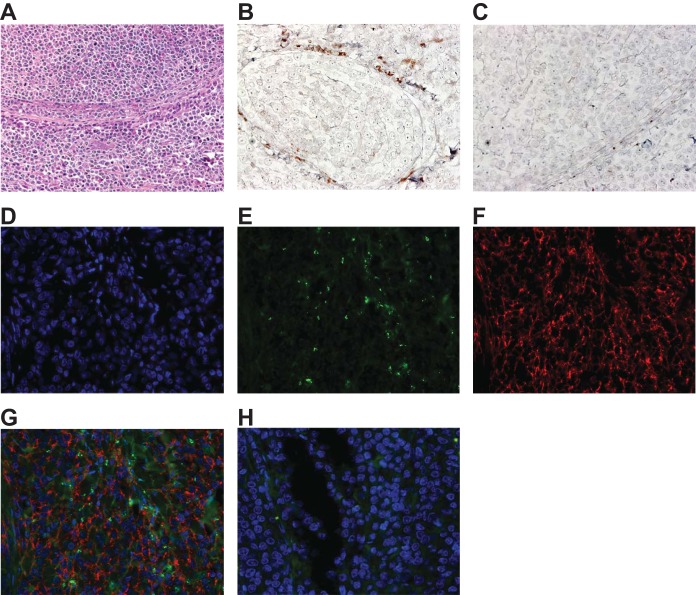

FIG 2.

Staining of a pancreatic tissue mass from vCD200 NS-infected animal 26001. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Original magnification, ×200. (B and C) In situ hybridization performed with an RRV cosmid DNA probe (B; brown) or cosmid vector control DNA (C), indicating the presence of viral DNA within the tissue lesion. Original magnification, ×400. (D to G) Immunofluorescence staining of a single tissue section using Hoechst dye for nuclei (D; blue), anti-RRV vIL-6 monoclonal antibody (E; green), and anti-CD20 antibody (E; red), demonstrating the colocalization of vIL-6 and infiltrating CD20+ B cells within the lesion. A merged image is shown in panel G. Original magnification, ×400. (H) Control for immunofluorescence staining using IgG isotype control antibodies for vIL-6 and CD20 and Hoechst dye for nuclei (blue). Original magnification, ×400.

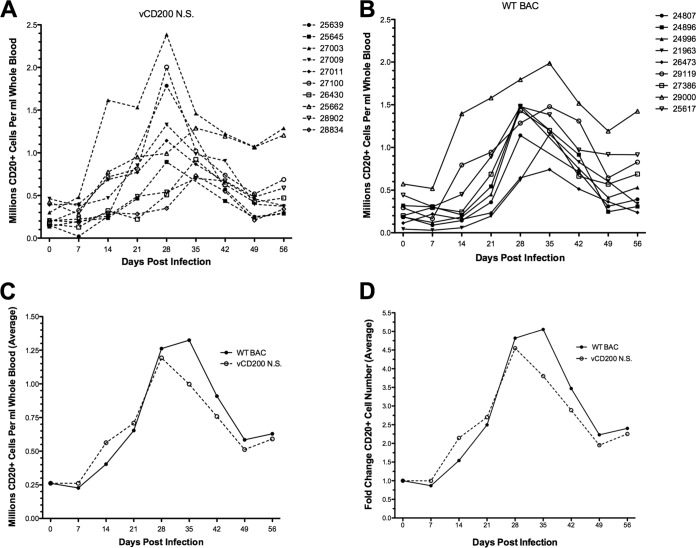

Another hallmark of RRV infection in RM is the development of B cell hyperplasia, which is characterized by a 2-fold or higher increase in B cell numbers in peripheral blood following inoculation. Analysis of total CD20+ B cell numbers in PBMC from immunocompetent animals (cohorts II to IV) following primary infection with WT BAC or vCD200 NS revealed that both viruses are equally capable of inducing B cell hyperplasia in infected RM (Fig. 3). Despite animal-to-animal variation, the general pattern of B cell hyperplasia observed in all RRV-infected animals began with a gradual increase in total CD20+ B cells from 7 to 28 days postinfection (dpi), with peak levels occurring at 28 to 35 dpi and then declining from 35 to 49 dpi but remaining elevated above baseline levels for the remainder of the study (Fig. 3A and B). Comparison of the average number of total CD20+ B cells (Fig. 3C) and average fold change in CD20+ B cells (Fig. 3D) among animals infected with the same virus further indicated that no notable difference exists between vCD200 NS and WT BAC viruses with regard to their ability to induce alterations in CD20+ B cell numbers in infected RM. Taken together, these data indicate that RRV vCD200 does not affect the development of B cell hyperplasia in RRV-infected animals.

FIG 3.

Development of B cell hyperplasia in infected RM. (A and B) vCD200 NS-infected (A) and WT BAC-infected (B) animals were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the total number of CD20+ B cells per ml of whole blood. (C) Averages of total B cell numbers in the virus infection groups displayed in panels A and B. (D) Fold change over day 0 baseline levels of average B cell numbers in the virus infection groups displayed in panels A and B.

RRV vCD200 affects viral loads in vivo.

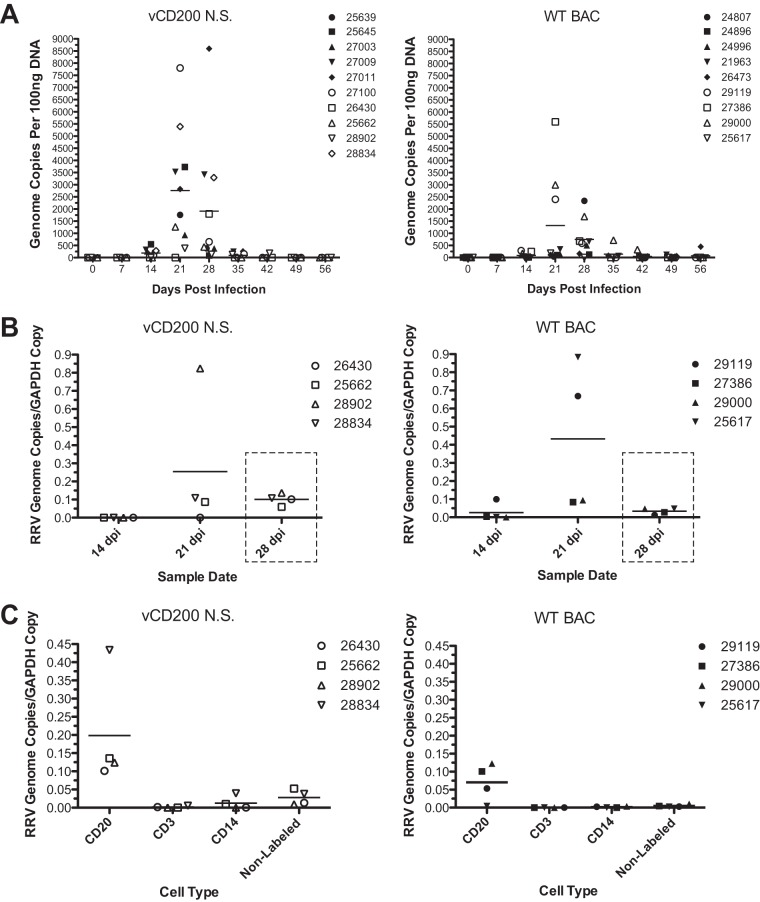

To assess the potential effects of RRV vCD200 on viral replication levels in vivo, real-time PCR analysis was performed using DNA isolated from WB samples collected from RM in cohorts II to IV during the course of infection (Fig. 4A). Although variability in genome copies existed between individual animals, a relatively rapid increase in viral DNA loads was detected by 21 to 28 dpi in most animals, with levels returning to near baseline by 35 dpi. Peak viral loads occurred at either 21 or 28 dpi in all animals; however, in vCD200 NS-infected animals, the peak viral loads occurred sooner overall, with 8 of 10 (80%) vCD200 NS-infected and 4 of 9 (44.4%) WT BAC-infected animals demonstrating peak viral loads at 21 dpi. Further, the average viral load detected in vCD200 NS-infected animals at 21 dpi was approximately double that detected in WT BAC-infected animals (2,874.2 copies versus 1,321.8 copies, respectively), although this difference was not found to be statistically significant. The highest individual viral loads were also detected in vCD200 NS-infected animals 27011 and 27100, with 8,602.6 and 7,805.4 genome copies, respectively, while the highest viral load detected in any WT BAC-infected RM was only 5,598.0 genome copies in animal 27386. Although a significant difference in viral loads was not demonstrated between virus infection groups, these data nevertheless indicate that vCD200 NS-infected animals display a trend toward an earlier increase and elevated levels of viral loads compared to WT BAC-infected animals, suggesting that vCD200 expression has inhibitory effects on RRV replication levels in vivo.

FIG 4.

Measurement of viral DNA loads in whole blood, LN biopsy samples, and sorted PBMCs. (A) DNA was purified from whole blood collected from each animal at the indicated time points postinfection, and 100 ng of each DNA sample was utilized to measure viral genome copies via real-time PCR analysis with a primer and probe set specific for the RRV vMIP sequence. Individual animal numbers are indicated, and horizontal lines represent average values for each time point. (B) LN biopsy samples were collected from group IV animals at 14, 21, and 28 dpi, and DNA was isolated from LN cells for use in real-time PCR analysis to determine the RRV genome copy numbers (RRV vMIP primer and probe set) and GAPDH copy numbers (GAPDH primer and probe set) present in each sample. The ratio of RRV genome copy number to GAPDH copy number was calculated for each sample. Values for individual animals are indicated, and horizontal lines represent average values of all animals at each time point. Dashed boxes denote that a significant difference in the average number of genome copies was detected between WT BAC-infected and vCD200 NS-infected animals at 28 dpi (P = 0.0093, unpaired t test). (C) PBMC were purified from maximum blood draws obtained from group IV animals at 28 dpi and were subjected to sequential sorting with magnetic beads to obtain purified CD20+, CD3+, and CD14+ cell populations. Nonlabeled cells represent the remainder of each PBMC sample depleted of CD20+, CD3+, and CD14+ cells. Sorted cells were divided equally into triplicates, DNA was isolated from each sample, and real-time PCR analysis was performed to determine RRV genome copy numbers and GAPDH copy numbers. The ratio of RRV genome copy number to GAPDH copy number was calculated for each sample, and the average of triplicate values for each cell type is reported for each animal. Horizontal lines represent the average values among all animals at each time point.

In addition to weekly WB sampling, lymph node biopsy specimens were also obtained from cohort IV animals at defined dates postinfection (14, 21, and 28 dpi), and DNA was isolated from cells purified from these tissues for use in real-time PCR analysis to determine RRV genome copy numbers. Due to variations in LN biopsy tissue sample sizes and the inherent variability in the cell numbers isolated from each sample, the level of GAPDH copies in individual samples was simultaneously determined as an internal control, allowing for the determination of a ratio of RRV genome copy number to GAPDH copies in each tissue sample. Examination of the RRV genome copies/GAPDH copy number ratios indicated that, similar to what was seen in WB samples, in most animals little or no viral DNA was detectable at 14 dpi, with viral DNA loads increasing to detectable levels by day 21 dpi and then declining but remaining elevated above baseline levels in both vCD200 NS-infected and WT BAC-infected animals by 28 dpi (Fig. 4B). The highest levels of detectable viral loads occurred in 21-dpi LN samples from both vCD200 NS-infected and WT BAC-infected animals, though there was some variability in genome copy levels detected in each infection group and no significant difference existed in the average ratios between infection groups at this time point. However, although the genome copy/GAPDH copy ratios declined in all animals by 28 dpi, vCD200 NS-infected animals possessed a higher average viral load than WT BAC-infected animals at this same time point (0.1015 versus 0.03359), a difference that was found to be statistically significant (P = 0.0093, unpaired t test). These data closely correlate with the observed differences in average levels of viral DNA loads in WB samples from infected animals in cohorts II to IV and further demonstrate that vCD200 expression in vivo results in lower viral loads in RRV-infected animals during acute infection.

In an attempt to also assess the possible effects of RRV vCD200 on virus tropism and replication in PBMC during in vivo infection, PBMC were isolated from WB obtained from maximum blood draws of cohort IV animals taken at 28 dpi, a time at which viral loads in WB were found to be elevated in both vCD200 NS-infected and WT BAC-infected RM. The isolated PBMC were subjected to sequential sorting using NHP-specific magnetic beads, resulting in the isolation of CD20+ B cells, CD3+ T cells, and CD14+ myeloid cells and also producing a nonlabeled cell fraction that represented all remaining cell types in PBMC samples. After sorting, the resulting samples were evenly split into triplicates, DNA was isolated from each, and real-time PCR was performed to determine the levels of both RRV genome copies and GAPDH copies. The RRV genome copy-to-GAPDH copy ratio was then calculated, and the values for triplicate samples were averaged to determine the relative amount of viral genomes present in sorted cell types from each animal sample (Fig. 4C). These data indicated that, as expected, CD20+ B cells harbored the majority of RRV genomic DNA in RM PBMC, with essentially no viral DNA being detected in any other cell types in these samples. Thus, RRV vCD200 does not appear to have a major impact on viral tropism, at least in PBMC. Also, similar to what was seen in WB samples, the average level of viral genome copies in CD20+ cells was slightly elevated in samples from vCD200 NS-infected versus WT BAC-infected RM, although this difference was not statistically significant.

PBMC samples from all infected animals were also subjected to coculture analysis by incubation with primary rhesus fibroblasts. Supernatants of representative coculture samples that developed cytopathic effect (CPE) were screened for the presence of input virus via PCR spanning the R15-ORF74 region followed by direct sequencing of the resulting PCR products. These findings confirmed that the virus isolated from individual animals corresponded to the respective input virus used for the initial inoculations and also indicated that the vCD200 NS virus maintained the mutated R15 sequence during in vivo infection (data not shown).

Effects of vCD200 on immune responses in infected RM.

The expression of vCD200 molecules during in vivo infection has been hypothesized to have immunosuppressive effects that can diminish immune responses directed against viruses expressing these proteins. Thus, we sought to examine the effects that lack of vCD200 expression may have on the development of adaptive immune responses directed against RRV. For these analyses, data from cohorts II, III, and IV were directly compared, while those from cohort I were excluded due to the primary SIV inoculation status of these animals.

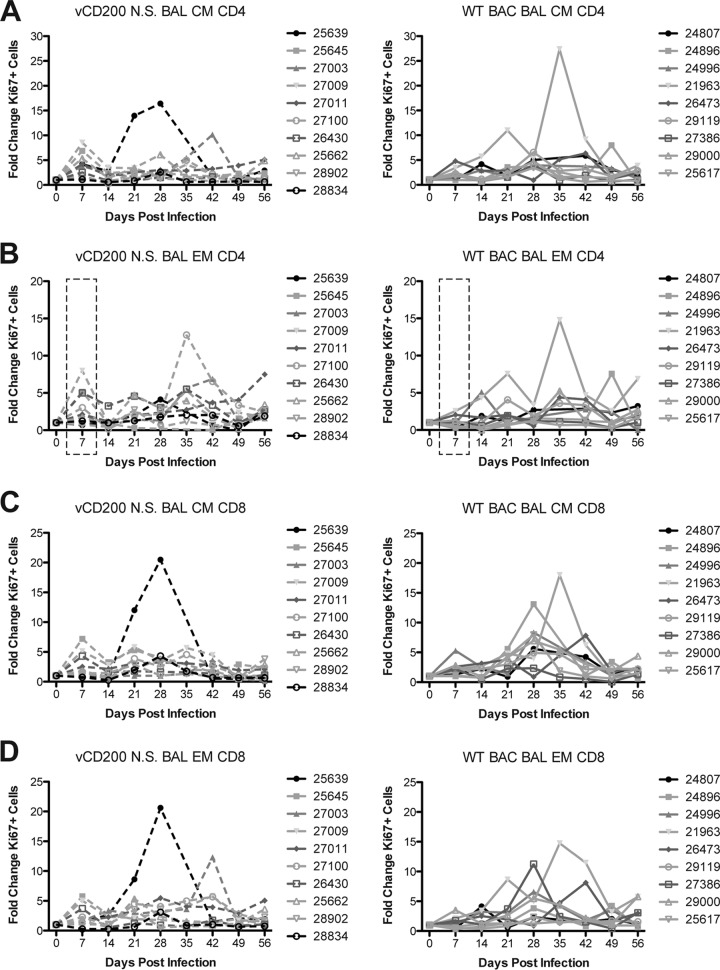

As an initial measure of immune responses in infected animals, PBMC and BAL cells were stained for Ki67, a nuclear protein whose expression indicates recent entry into the cell cycle, as well as a panel of antibodies to define naive (IgD+ CD27−), marginal zone-like (MZ-like; IgD+ CD27+), and memory (IgD− CD27+) B cell subsets, as well as central memory (CM; CD28+ CD95+) and effector memory (EM; CD28− CD95+) CD4 and CD8 T cells. This analysis allows for a general measure of B and T cell proliferative responses that occur in infected animals due to RRV infection. Upon examination of CD20 subsets in both PBMC and BAL, no differences were noted between virus infection groups in regard to B cell proliferation patterns at any time point or in any subset, and in general, B cell proliferation patterns were largely variable (data not shown). Changes in Ki67 levels in T cells from PBMC were also variable overall in all subsets examined, with a general elevation in the number of proliferating cells occurring from 7 to 14 dpi and fluctuations thereafter until 49 to 56 dpi, at which time the levels of proliferating cells declined to or near-preinfection levels in all animals (data not shown). Conversely, Ki67 levels in T cells from BAL, though lower in overall intensity than those seen in PBMC, demonstrated observable differences in proliferative patterns between viruses at early time points postinfection. Specifically, a defined peak of elevated proliferation was observed at 7 dpi in CM and EM subsets of both CD4 and CD8 T cells in BAL from vCD200 NS animals, which was not as pronounced in WT BAC-infected animal samples from this same time point (Fig. 5). This elevated proliferative response in vCD200-infected animals declined in all subsets by 14 dpi, before a more variable pattern of proliferation ensued during the remainder of the infection period. Notably, a significant difference in the average fold change of Ki67+ cells was detected at 7 dpi in EM CD4 subsets in BAL (Fig. 5B), with a higher number of proliferating cells being present in vCD200 NS-infected animals. The lack of a defined early proliferative peak at 7 dpi in BAL samples from WT BAC-infected animals implies that vCD200 expression inhibits CD4 and CD8 T cell proliferation early after RRV infection, although this effect is eventually overcome as the infection progresses.

FIG 5.

T cell proliferative responses in BAL fluid of infected RM. T cell proliferation in BAL samples was measured by staining cells for expression of nuclear protein Ki67 and surface antibodies to define central memory (CM; CD28+ CD95+) and effector memory (EM; CD28− CD95+) CD4 and CD8 T cells. The fold increase over the day 0 baseline sample value is reported for each animal. (A) CM CD4; (B) EM CD4; (C) CM CD8; (D) EM CD8. Dashed boxes in panel B indicate that a significant difference (P = 0.0386, unpaired t test) in average proliferation levels was detected at 7 dpi between WT BAC-infected and vCD200 NS-infected animals in EM CD4 T cells.

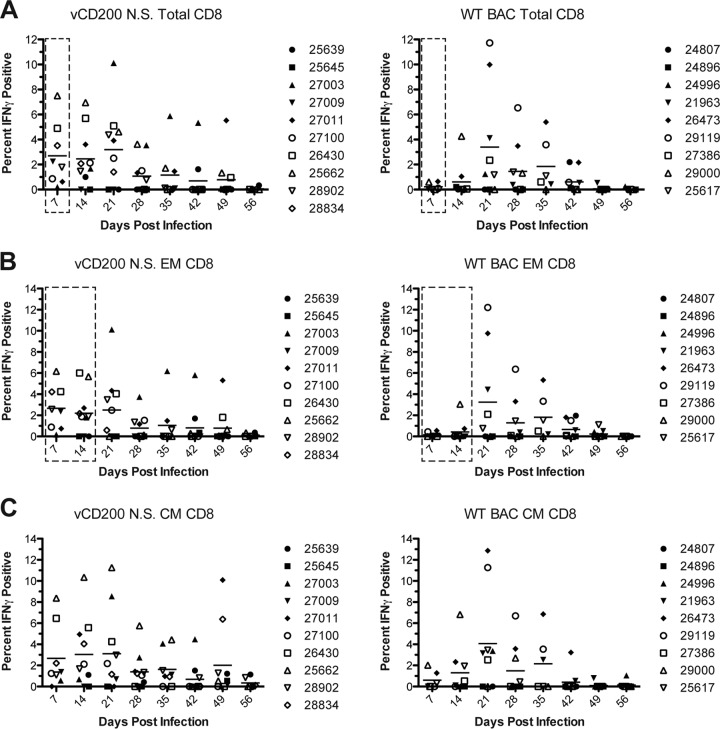

A major question we also wished to address was whether or not vCD200 affects the development of RRV-specific T cell responses in vivo, which could have a direct impact on viral immunity, control of infection, and pathogenesis. Thus, to determine the level of RRV-specific T cell responses in infected RM, in vitro ICCS assays were performed. For these experiments, purified PBMC or BAL cells from infected RM were stimulated with WT RRV BAC in vitro, followed by staining of cells with antibodies directed against CD4, CD8, CD28, and CD95, and IFN-γ, to determine the percentage of responsive T cells present in each sample. In PBMC samples, the overall levels of responses detected for all T cell subsets examined were low, and there was a large variability of responses in all animals (data not shown). Further, no specific patterns were observed in T cell responses in PBMC, and no difference in responses between viruses was noted. However, unlike PBMC, BAL samples are enriched for a higher number of responding memory cells and therefore provide a source of more readily detectable T cell responses. Indeed, RRV-specific CD8 and CD4 T cell responses were detectable in BAL samples from all infected animals (Fig. 6 and 7), with an increase in the number of responding IFN-γ+ cells observed following RRV infection and generally returning to near baseline levels by 56 dpi. Importantly, however, notable differences in T cell responses between virus infections were also apparent, with the detection of stronger CD8 and CD4 responses in vCD200 NS-infected animals at early times postinfection. Specifically, examination of CD8 responses revealed that little to no RRV responsive cells were detected in WT BAC-infected animals at 7 and 14 dpi, while a majority of vCD200 NS-infected animals possessed detectable levels of IFN-γ+ RRV-specific cells at these same time points. Further, compared to WT BAC-infected animals, on average, vCD200 NS-infected animals possessed a higher percentage of responding total CD8 cells (Fig. 6A), as well as EM and CM CD8 cells (Fig. 6B and C), at both 7 and 14 dpi. Most notably, significant differences between the average responses of vCD200 NS-infected and WT BAC-infected animals were observed in total CD8 cells at 7 dpi (P = 0.0337) and in EM CD8 cells at 7 and 14 dpi (P = 0.0372 and P = 0.0134, respectively). Although a similar trend appeared to exist in CD4 T cells from BAL samples (Fig. 7), the differences between viruses were not as well defined and no statistically significant differences in responses were identified. Interestingly, the observed differences in T cell responses between WT BAC and vCD200 NS-infected animals were only apparent at early times postinfection (i.e., 7 and 14 dpi), since by 21 dpi the average responses for vCD200 NS-infected and WT BAC-infected animals were similar and remained so throughout the rest of the infection period. Taken together, these data indicate that vCD200 is capable of inhibiting the development of T cell responses induced by RRV infection in vivo, although the inhibitory effects of vCD200 were only apparent at early times postinfection (7 and 14 dpi), with responses in animals infected with vCD200 NS eventually becoming comparable to those in WT BAC-infected animals by 21 dpi. This suggests that the regulatory effects of RRV vCD200 on the development of T cell responses are functional mainly early during in vivo infection and that the effects of this regulation are overcome as the infection progresses.

FIG 6.

RRV-specific CD8 T cell responses in BAL samples from infected RM. The percentages of RRV-specific total (A), effector memory (B), and central memory (C) RRV-specific CD8 T cells in BAL samples were determined by performing ICCS to measure the number of T cells in each sample that produced IFN-γ in response to RRV antigen exposure in vitro. The percentage of IFN-γ+ cells in each sample was determined after subtracting baseline (day 0) staining levels, and values from 7 to 56 dpi are reported. Individual values are displayed for each animal, and the average for each time point is denoted by a horizontal line. Compared to WT BAC-infected animals, on average, CD8 T cell responses were elevated at early times postinfection (7 and 14 dpi) in vCD200 NS-infected animals in all subsets. Dashed boxes in panels A and B indicate that significant differences in average responses were detected at 7 dpi in total CD8 (P = 0.0337; unpaired t test) and at both 7 and 14 dpi in EM CD8 (P = 0.0134 and P = 0.0372, respectively; unpaired t test).

FIG 7.

RRV-specific CD4 T cell responses in BAL samples of infected RM. The percentages of RRV-specific total (A), effector memory (B), and central memory (C) RRV-specific CD4 T cells in BAL samples were determined by performing ICCS as described in the legend for Fig. 6. Individual values are displayed for each animal, and the average for each time point is denoted by a horizontal line.

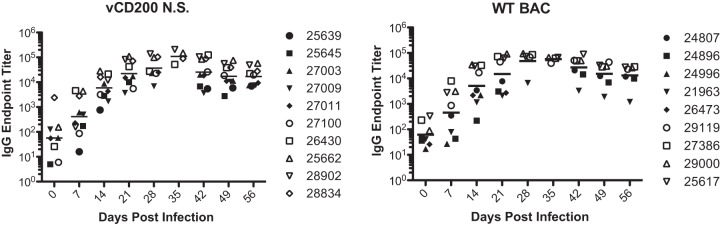

Finally, RRV-specific antibody responses in animals from cohorts II to IV were also measured. These results indicated that after infection with either WT BAC or vCD200 NS, antibody levels steadily climbed from 0 dpi to 28 dpi in all animals, at which point they plateaued and remained relatively steady (Fig. 8). The average responses for animals infected with WT BAC versus vCD200 NS were similar at all times postinfection, and no measurable difference in responses was detected between viruses. Therefore, vCD200 expression does not impact the development of an RRV-specific antibody response in vivo.

FIG 8.

Anti-RRV IgG responses in infected RM. IgG endpoint titers in plasma obtained from group II to IV animals were determined in an RRV-specific ELISA. Values for individual animals are indicated, and the average response at each time point is indicated by a horizontal line.

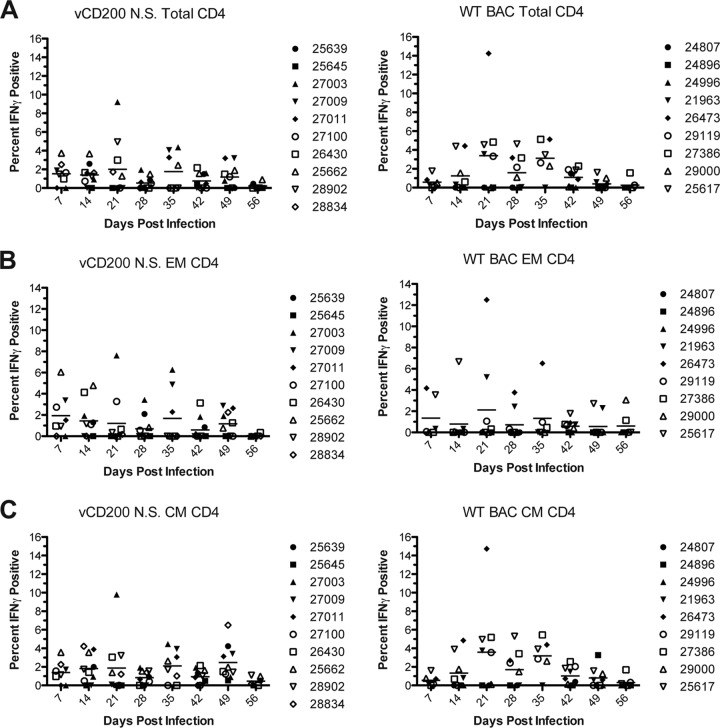

CD200 receptor expression in RM PBMC.

CD200R has generally been considered expressed predominantly on cells of the myeloid lineage, of which CD200 has been implicated as a major regulator of activation (2, 4, 51). However, the putative expression profile of CD200R has more recently widened, as it has also been reported to be detectable on several other cell types, including T cells and B cells in both mice and humans (5, 6). Despite this information, the CD200R expression pattern in RM has not yet been fully examined, and thus, in an attempt to gain more insight into the distribution profile of this receptor in RM and also help identify potential cellular targets of RRV vCD200 binding and regulation in vivo, analyses were undertaken to assess the location of the receptor in RM PBMC. To identify the location of CD200R, PBMC were isolated from preinfection WB samples of all animals in cohorts II to IV and stained with an anti-human CD200R antibody that cross-reacts with RM CD200R. Samples were also costained with a panel of antibodies to define the relative amounts of CD200R expression on CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD20+ B cells, dendritici cells (DCs; CD14− HLA-DR+), and monocytes (CD14+ HLA-DR+).

Although we anticipated that CD200R expression in RM PBMC might be limited mainly to myeloid lineage cells in our staining panel (i.e., monocytes and DCs), the results obtained indicated that CD200R was detectable to some level on all cell types examined in RM peripheral blood, including lymphocytes (Fig. 9A). Despite the variability among individual animals, on average, CD200R levels were found to be highest on DCs, followed next by B cells, CD4 T cells, monocytes, and CD8 T cells. Overall, this information suggests that CD200R is likely to be involved in the regulation of a variety of different immune cells in RM, and consequently, that RRV vCD200 may be capable of directly regulating these same cells during in vivo RRV infection.

FIG 9.

CD200R expression patterns in naive RM PBMC and assessment of RRV vCD200 binding to RM CD200R. (A) PBMCs purified from preinfection whole blood samples (day −7 and day 0) obtained from animals in cohorts II, III, and IV were stained with surface antibodies to delineate CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, CD20+ B cells, DCs, and monocytes, as well as an antibody directed against CD200R, to determine the percentage of each cell type expressing the receptor. The average values obtained for day −7 and day 0 samples are presented for each individual animal, and the average level of staining observed for each subset is noted by a horizontal line. (B and C) CHO cells were transfected with a vector expressing full-length RM CD200R, or with empty vector as a control, incubated for 48 h, and collected for flow cytometry analysis. Cells were stained with a PE-conjugated antibody against CD200R and incubated with recombinant RRV vCD200-Fc fusion protein or Fc control protein conjugated to FITC. (B) CD200R staining of cells transfected with RM CD200R (solid line) or empty vector control (dashed line). (C) Percent of vCD200-Fc binding to RM CD200R-expressing cells and vector control cells. Percent vCD200-Fc binding was calculated for each sample by subtracting the background staining levels obtained with Fc control protein from vCD200-Fc staining levels. Data represent the averages of duplicate experiments, and error bars indicate standard errors of the means.

Despite the fact that RRV vCD200 has previously been shown to regulate cells expressing CD200R in vitro (35), it is yet to be directly demonstrated that RRV vCD200 is capable of binding to RM CD200R. Therefore, cDNA expressing full-length RM CD200R was isolated from RNA derived from RM PBMC and cloned into an expression vector to allow for analysis of vCD200 binding in vitro. CHO cells were transfected with the RM CD200R expression vector, or empty vector as a control, and then cells were collected and stained with antibody directed against CD200R to confirm expression of the receptor (Fig. 9B). Cells were also incubated with FITC-labeled vCD200-Fc protein to assess the ability of RRV vCD200 to directly bind RM CD200R expressed on the cell surface (Fig. 9C). These data indicated that only cells expressing RM CD200R exhibit binding of vCD200-Fc and demonstrated that RRV vCD200 specifically binds to RM CD200R.

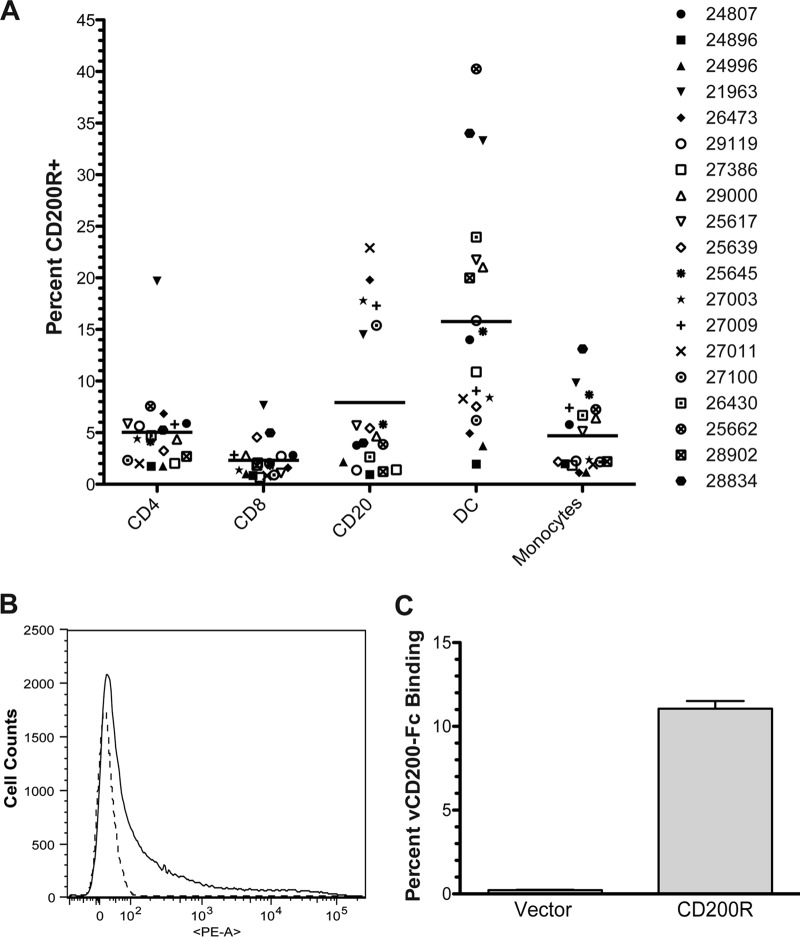

Although our initial CD200R expression screening provided a general background regarding receptor distribution in uninfected RM PBMC, given that a variety of microbial pathogens are known to affect CD200/CD200R expression levels during in vivo infection (19, 21, 23, 25, 52), we sought to determine whether RRV infection has any effects on CD200R expression in RM. In order to directly address this issue, PBMC samples from cohort IV were analyzed throughout the infection study period to assess CD200R expression levels on PBMC subsets. Examination of the staining patterns during acute RRV infection (day 0 to day 56) indicated that changes in CD200R expression levels did indeed occur in different RM PBMC subsets after RRV infection and that these alterations were essentially the same between WT BAC-infected and vCD200 NS-infected animals. In monocytes, slight fluctuations in receptor levels occurred from 0 to 28 dpi in all animals, before a sharp and rapid increase was observed from 28 to 35 dpi, with levels then rapidly declining back to baseline levels by 42 dpi (Fig. 10A). Despite slight variability in preinfection CD200R levels between animals, in DCs there was a noticeable steady decline in CD200R levels from 0 dpi to 28 dpi, followed by a rapid spike to near preinfection levels at 35 dpi and a subsequent decline by 42 dpi (Fig. 10B). Interestingly, the changes in CD200R levels in DCs appeared to be inversely proportional to viral loads through 35 dpi, which suggests that RRV infection results in a repression of CD200R expression in DCs early during infection as viral loads progressively increase, but that as viral infection is later brought under control and viral loads decrease, CD200R levels rapidly rebound before ultimately regaining more stability.

FIG 10.

Effects of RRV infection on CD200R expression patterns in RM PBMC. PBMC purified from weekly WB samples obtained from animals in cohort IV were stained with surface antibodies to delineate monocytes (A), DCs (B), CD4 T cells (C), CD8 T cells (D), and CD20+ B cells (E), as well as an antibody directed against CD200R, to determine the percentage of each cell type that expressed the receptor during acute RRV infection.

In addition to myeloid lineage cells, lymphocytes also demonstrated changes in CD200R levels during RRV infection. Specifically, CD4 and CD8 T cells displayed alterations in overall CD200R levels that appeared to follow a biphasic pattern, with elevations in receptor levels occurring in most animals by 7 dpi followed by a decrease at 14 dpi, and alternating in this manner through approximately 42 dpi (Fig. 10C and D). Staining of total CD20+ B cells indicated more dramatic changes in CD200R levels in response to RRV infection, with all animals displaying a slow elevation in CD200R levels from 0 to14 dpi, followed by a slight decrease at 21 dpi and a second and more robust increase to peak levels for most animals at 35 dpi (Fig. 10E). CD200R levels remained elevated in these cells until 49 dpi, at which point they quickly declined to near baseline levels. The pattern of CD200R expression levels in B cells seems to partly parallel the change in total B cell levels observed in infected animals, which rise to peak levels at 28 and 35 dpi (Fig. 3). It is possible that the observed increase in CD200R levels seen on B cells is due to the preferential expansion of CD200R+ CD20+ cells after RRV infection, or simply an upregulation of CD200R expression on all CD20+ cells, which in either case could result in an increase in the overall percentage of B cells that are positive for CD200R.

Importantly, because the observed changes in CD200R levels in the cell types examined were similar in animals infected with either WT BAC or vCD200 NS virus, vCD200 expression itself does not appear to affect changes in CD200R levels in PBMC in RRV-infected RM. Thus, alterations in CD200R levels in vivo are likely to occur as a general response to RRV infection, although the exact mechanisms that may be involved remain uncertain. Finally, examination of samples up to approximately 1 year postinfection, after virus had become quiescent and was no longer actively replicating, indicated that receptor levels in all cell types remained relatively unchanged in all animals from the levels detected at day 56 (data not shown). Thus, active acute viral replication appears to be required for the observed alterations in CD200R expression levels induced by RRV infection.

DISCUSSION

CD200, together with its receptor CD200R, represents an inhibitory signaling pathway that plays a critical role in maintaining immune homeostasis, and as such, this pathway has been implicated as being involved in modulating a variety of diseases, ranging from cancers to neurodegenerative disorders (2). The importance of CD200 to immunity has been further demonstrated by its central involvement in regulating responses during microbial infections (52), and also by the fact that several viruses of the Poxviridae, Adenoviridae, and Herpesviridae families have been shown to encode functional homologues of this molecule (7, 28–30, 35). These vCD200 proteins are generally thought to be beneficial to viral survival within the host, since targeting of the CD200/CD200R axis is likely to play an important role in regulating the development of immune responses generated against these pathogens. Due to their ability to alter normal immune function, vCD200 proteins have the potential to directly affect virus-associated disease development in vivo (28); however, the precise roles that a majority of vCD200 molecules play in viral pathogenesis are still not fully understood. To further define the function of the vCD200 molecule encoded by RRV and to shed light on the role that gammaherpesvirus vCD200 molecules play in immune regulation and disease development in vivo, we analyzed the activities of a mutant form of BAC-derived RRV lacking expression of vCD200 (vCD200 NS) in an RM infection model.

The CD200/CD200R pathway has been linked to involvement in a variety of B cell neoplasms (14, 15, 53), and in fact, the expression of CD200 has been shown to be a strong prognostic marker for some B cell neoplasms (18). Therefore, we hypothesized that expression of RRV vCD200 has detectable effects on virus-associated disease development in vivo, due to the potential for dysregulation of normal CD200/CD200R function in RRV-infected RM. However, comparison of animals infected with WT BAC and vCD200 NS indicated no differences in disease manifestations between viruses, with all animals developing similar levels and patterns of B cell hyperplasia and no observable variation in occurrence of lymphoma or other neoplasms. Taken together, our data suggest that vCD200 does not strongly affect RRV-associated disease development in RM.

One particularly interesting finding was that RM infected with vCD200 NS possessed higher viral loads than RM infected with WT BAC. Specifically, though the general patterns of viral load development were similar, the average levels detected in WB of vCD200-infected animals were higher, with the highest viral loads overall being detected in two vCD200 NS-infected animals. Further, examination of DNA samples from LN biopsies of infected RM taken near the observed times of peak viral loads in WB demonstrated a significant difference in viral loads between WT BAC and vCD200 NS viruses in these tissues. Taken together, these data suggest that expression of RRV vCD200 has an inhibitory effect on viral replication in vivo, although the exact mechanism involved remains to be elucidated.

Due to its known immune-inhibitory activity in vitro (35), we anticipated that RRV vCD200 expression was likely to affect the development of immune responses against RRV in vivo, and in fact, this was observed. Early after infection, both CD8 and CD4 T cells in vCD200 NS-infected animals displayed a rapid but transitory elevation in proliferation levels which was not observed in animals infected with WT BAC. Furthermore, ICCS analysis indicated that animals infected with WT BAC possess decreased levels of RRV-specific CD8 and CD4 T cells compared to vCD200 NS-infected animals, although this was only observed at early times postinfection (i.e., 7 and 14 dpi). This difference in development of RRV-specific responses was most pronounced in CD8 T cells, and interestingly, this inhibition seemed to be short-lived, as the levels of CD8 responses became relatively equivalent in animals infected with either vCD200 NS or WT BAC at later times during infection. Despite the apparent effects of vCD200 on T cell responses, however, no difference in RRV-specific antibody responses was detected between animals infected with WT BAC or vCD200 NS.

Though CD200R has most often been described as being predominantly expressed on myeloid lineage cells, various reports have shown that the receptor is expressed on a variety of immune cells, including T and B cells (2, 5–7). Indeed, staining of PBMC subsets from naive RM for CD200R expression indicated that the receptor was detectable on all cell types examined, including monocytes, DCs, T cells, and B cells, but that on average, CD200R levels were highest on DCs and B cells. Overall, these data demonstrate that CD200R expression is not strictly limited to myeloid cells in RM, and that CD200 is likely capable of directly regulating a wide array of immune cells in vivo, including T and B cells. In addition, we also found that RRV vCD200 can bind to RM CD200R, indicating that this viral protein is also capable of regulating cell types within the host that express the receptor.

Changes in CD200/CD200R expression levels have been reported to occur after in vivo infection with a variety of microbial pathogens (19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 52), and this also appears to be the case during RRV infection of RM. Specifically, de novo infection of eSPF RM with either WT BAC or vCD200 NS resulted in observable fluctuations in CD200R expression levels in both myeloid cells and lymphocytes in the weeks following infection, with the most notable changes in CD200R levels occurring in DCs, monocytes, and B cells. DCs displayed a steady decline in CD200R levels immediately following infection, followed by a rapid spike at 35 dpi, before returning to near preinfection levels, while monocytes also demonstrated a sharp increase in CD200R levels at 35 dpi. On the other hand, B cells demonstrated a more gradual elevation of CD200R levels throughout the course of the infection, peaking near 35 dpi before ultimately resolving to near preinfection levels. Interestingly, peak levels of CD200R expression in monocytes, DCs, and B cells occurred approximately 1 week after the resolution of viral replication, which is similar to observations made in studies of influenza virus infection in mice (21). Importantly, the observed changes in CD200R levels occurred similarly after infection with either WT BAC or vCD200 NS, demonstrating that this effect is independent of vCD200 expression. Also, following resolution of acute RRV infection in RM, CD200R expression appeared to stabilize to near preinfection levels on all cell types that were examined, indicating that active viral replication is required to affect changes in receptor levels.