ABSTRACT

Following retrovirus entry, the viral capsid (CA) disassembles into its component capsid proteins. The rate of this uncoating process, which is regulated by CA-CA interactions and by the association of the capsid with host cell factors like cyclophilin A (CypA), can influence the efficiency of reverse transcription. Inspection of the CA sequences of lentiviruses reveals that several species of simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) have lost the glycine-proline motif in the helix 4-5 loop important for CypA binding; instead, the helix 4-5 loop in these SIVs exhibits an increase in the number of glutamine residues. In this study, we investigated the role of these glutamine residues in SIVmac239 replication. Changes in these residues, particularly glutamine 89 and glutamine 92, resulted in a decreased efficiency of core condensation, decreased stability of the capsids in infected cells, and blocks to reverse transcription. In some cases, coexpression of two different CA mutants produced chimeric virions that exhibited higher infectivity than either parental mutant virus. For this complementation of infectivity, glutamine 89 was apparently required on one of the complementing pair of mutants and glutamine 92 on the other. Modeling suggests that glutamines 89 and 92 are located on the distal face of hexameric capsid spokes and thus are well positioned to contribute to interhexamer interactions. Requirements to evade host restriction factors like TRIMCyp may drive some SIV lineages to evolve means other than CypA binding to stabilize the capsid. One solution used by several SIV strains consists of glutamine-based bonding.

IMPORTANCE The retroviral capsid is an assembly of individual capsid proteins that surrounds the viral RNA. After a retrovirus enters a cell, the capsid must disassemble, or uncoat, at a proper rate. The interactions among capsid proteins contribute to this rate of uncoating. We found that some simian immunodeficiency viruses use arrays of glutamine residues, which can form hydrogen bonds efficiently, to keep their capsids stable. This strategy may allow these viruses to forego the use of capsid-stabilizing factors from the host cell, some of which have antiviral activity.

INTRODUCTION

The primate immunodeficiency viruses are a subgroup of lentiviruses that include the human (HIV) and simian (SIV) immunodeficiency viruses (HIV type 1 [HIV-1], HIV-2, and various SIVs) (1). Many species of feral monkeys in Africa carry SIVs of a specific lineage, in most cases with minimal pathological consequences (2). Pathogenic primate immunodeficiency viruses arose as a result of transmission of these African monkey SIVs into new primate host species. SIV of chimpanzees (SIVcpz) is thought to have arisen through a recombination of two SIVs from greater spot-nosed monkeys and red-capped mangabeys (3). Multiple independent cross-species events of transmission of SIVcpz into humans engendered HIV-1 of distinct lineages, with group M HIV-1 causing most cases of AIDS in humans (4). HIV-2 infections in humans arose from transmission of SIVsmm from sooty mangabeys in West Africa. SIVsmm was also introduced into Asian macaques in primate centers in the United States, giving rise to different SIVmac, SIVsm, SIVstm, and SIVmne variants, some of which cause AIDS-like diseases in these animals (5, 6).

Like all retroviruses, lentiviruses commandeer host molecules to assist their replication. Host restriction factors have evolved to limit retrovirus replication. Primate immunodeficiency viruses adapt to both positive and negative factors in their preferred host species. Introduction into new species requires adjustments in the viral components that interact with such species-specific host factors.

Following entry into the host cell, retroviruses must negotiate several early-phase events, including uncoating of the viral capsid (CA), reverse transcription of the RNA genome, introduction of the preintegration complex into the nucleus, and integration of the viral DNA into the host chromosome (1). The lentivirus capsid, a conical protein shell of ∼1,500 capsid proteins, performs multiple functions in these early events. The CA proteins of retroviruses oligomerize into hexamers by virtue of interactions among the N-terminal domains, and additional interactions involving the C-terminal and N-terminal domains promote interhexamer interactions that contribute to capsid assembly and stability (7–10). In addition to these CA-CA associations, the interactions of the capsid with both stabilizing and destabilizing host proteins can influence the rate of uncoating. Alterations in the uncoating rate, in either a positive or negative direction, can result in decreases in reverse transcription or aberrant autointegration, respectively (11–15). The import of the preintegration complex into the nucleus, which contributes to the ability of lentiviruses to infect resting cells, can also be affected by changes in capsid stability. Host proteins that bind CA and can stabilize the capsid include cyclophilin A (CypA), PDZD8, and cytoplasmically localized CPSF6 (12, 16–18). Other capsid-binding proteins, TRIM5α and TRIMCyp, prematurely accelerate uncoating and thus block reverse transcription and infection (19–22).

Consistent with its diverse roles in the cells of multiple host species, the retroviral CA protein exhibits both conserved and type-dependent features. The CA fold and major homology region are conserved in retroviruses. In contrast, the helix 4-5 loop, which is exposed on the surface of the assembled capsid, exhibits considerable variability among the lentiviruses. The helix 4-5 loop of HIV-1 binds CypA, a prolyl cis-trans isomerase, usually resulting in capsid stabilization and a positive effect on infection (16, 23–26). The CypA domain of the nuclear pore protein Nup358 has been implicated in nuclear targeting of HIV-1 preintegration complexes (27, 28), and changes in the helix 4-5 loop can influence HIV-1 sensitivity to Nup358 knockdown (13, 28). The helix 4-5 loop of primate immunodeficiency virus CA proteins determines virus susceptibility to restriction mediated by TRIMCyp, a fusion protein of TRIM5 and CypA expressed in some monkey species (21, 29–31).

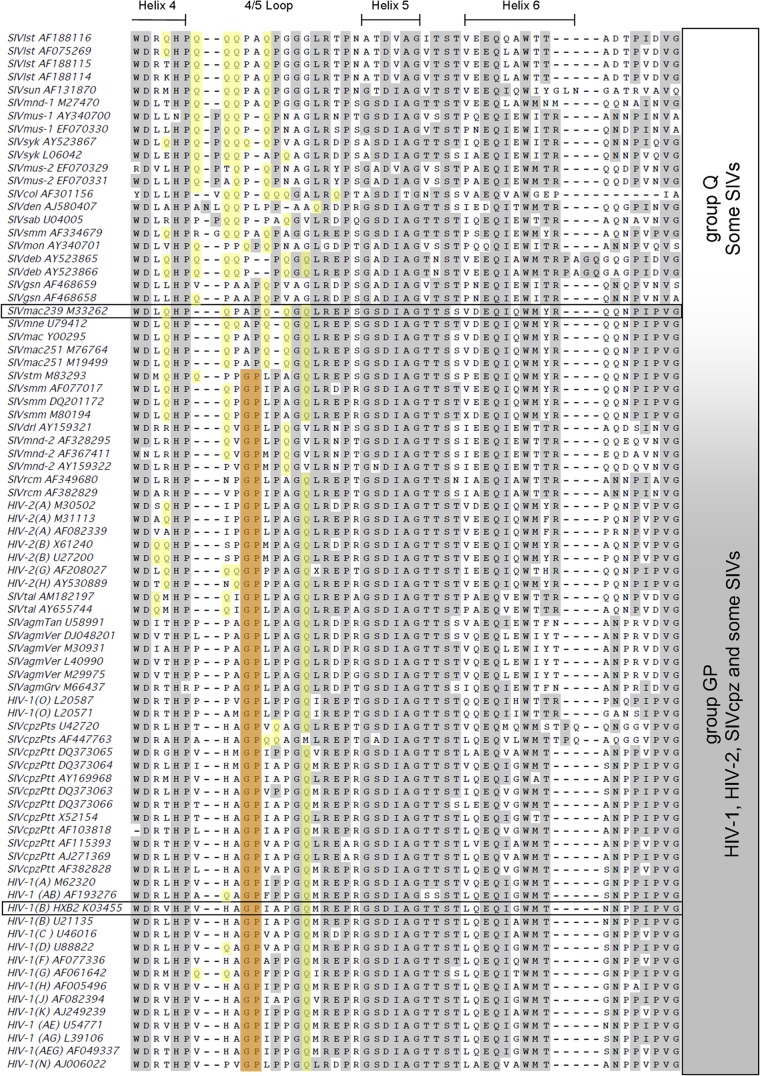

The potential for the helix 4-5 loop of the capsid to interact with both positive and negative host cell factors suggested that this region might exhibit changes conducive to primate immunodeficiency virus adaptation to various host species. Indeed, inspection of this CA region sequence from primate immunodeficiency viruses (Fig. 1) reveals two patterns. (i) One group of viruses (herein referred to as group GP viruses) contains a glycine-proline pair, which is a recognition motif for CypA (7–10). The group GP viruses include the human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV-1 and HIV-2), SIVcpz, and the SIVs of several monkey species (SIVagm, SIVrcm, SIVmnd and SIVsmm). There is a strong, but not absolute, correlation between the presence of the GP motif in the helix 4-5 loop and the interaction of the primate immunodeficiency virus capsid with Cyp A and/or TRIMCyp (13, 16, 32–38). (ii) The second group of viruses (herein referred to as group Q viruses) lacks the glycine-proline pair and instead exhibits a glutamine-rich sequence. The group Q viruses include the SIVs of several feral monkey species as well as the SIVs introduced into Asian monkeys in captivity.

FIG 1.

Alignment of primate immunodeficiency virus sequences from the region surrounding the helix 4-5 loop. Eighty complete CA sequences from the HIV Sequence Compendium were aligned using ClustalW and ordered using PHYLIP. Two groups of helix 4-5 loop sequences are apparent: group GP loops, containing a potential cyclophilin A binding motif GP (highlighted in orange), and group Q loops, which are rich in glutamine residues (highlighted in yellow). The former group contains HIV-1, HIV-2, SIVcpz, and some other SIV strains, the last consisting of SIVmac239 and several SIV lineages.

The helix 4-5 loop of CA in the group Q viruses apparently lacks an optimal binding motif for CypA, a known capsid-stabilizing host cell factor (31–34, 39, 40). Glutamine clusters exhibit a high potential to form hydrogen bond networks that promote protein-protein interactions (41, 42). We hypothesized that the glutamine residues in the helix 4-5 loop of the group Q viruses play a role in capsid interactions important for function. In this study, we tested this hypothesis by analyzing the phenotypes of a panel of SIVmac239 capsid mutants in which the glutamine residues of the helix 4-5 loop have been altered, either individually or in combination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture.

Adherent cell lines used in this study were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; high glucose) (Invitrogen; catalog number 11965) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Suspension cells were grown in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen; catalog number 11875) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. HEK293T/17 cells (ATCC; catalog number CRL-11268) and HeLa cells (ATCC; catalog number CCL-2) are of human origin. Cf2Th cells are of canine origin.

Production of single-round viruses expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP).

Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-based pSIVmac239ΔnefΔenvEGFP was derived from pSIVΔnefEGFP (43) (a kind gift from Ronald Desrosiers, HMS). Env sequences were deleted by first changing the ATG start codon to TCC to create a BspE1 site. The 1.1-kb fragment between this and the native BspE1 site at position 8013 (GenBank accession number M33262.1) was excised, leaving Tat, Rev, and the Rev-responsive element intact. This construct and derivative mutants were cotransfected into the desired cell type with a Rev-expressing plasmid and pHCMV-G, a plasmid that expresses the vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein (VSV-G), at a 20:1:2 ratio, as described previously (35). HEK293T/17 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine Plus or Lipofectamine 2000 by following the recommended protocol. To make chimeric viruses, constructs were mixed at 9:1, 6:1, 3:1, and 1:1 or finer gradations, of 2:1, 1.6:1, 1.3:1, and 1:1, to create master mixes. Construct master mixes were then cotransfected with the Rev- and VSV-G-expressing plasmids at the same ratio as that used for the single constructs. Viral products were filtered with a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane, and titers were determined by reverse transcriptase (RT) assay, as previously described (44). If necessary, viruses were concentrated by polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation using PEG-it (SBI; catalog number LV810A) and resuspended in an appropriate volume of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

SIV capsid mutants.

All SIV CA mutants were created by site-directed mutagenesis of either the full-length pSIVmac239ΔnefΔenvEGFP or the shuttle vector SGag3 (45), utilizing PFU Ultra Hotstart 2× master mix (Stratagene; catalog number 600630-51), 125 ng of each mutagenic primer, and the following cycling protocol: 95°C for 1 min, 18 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for either 12 min (full length) or 5.5 min (SGag3), with a final 1-min extension at 72°C. SGag3 sequences were then pasted into the full-length vector by DraIII/SbfI digestion and ligation with T4 DNA ligase. The presence of all mutations was verified by DNA sequencing. Mutagenic primers were ordered from IDT. The integrase-defective virus contains the D64V change in integrase. The plasmids expressing the capsid mutants were created using variants of the forward wild-type sequence GCAGCACCCACAACCAGCTCCACAACAAGGACAACTTAGG.

Infection assays.

HeLa and Cf2Th cells were seeded 1 day prior to infection into 24-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 to 3 × 105 cells/ml. On the day of infection, virus was added at the desired titer as determined by RT activity, expressed in counts per minute (cpm). The medium was changed 2 to 4 h after the addition of virus, and after 48 h of virus-cell incubation, the percentage of GFP-positive cells and median fluorescence were determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

Gag processing assay.

293T/17 cells were transfected with the SIVmac239 Gag-expressing constructs in 24-well plates. Sixteen hours posttransfection, the medium was replaced with DMEM plus 10% dialyzed FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1× l-glutamine, 1× nonessential amino acids, and 100× diluted [35S]Met/Cys labeling mix (NEG072). Forty-eight hours posttransfection, viruses were purified by filtration with a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane, followed by pelleting through 20% sucrose for 1 h at 100,000 × g. Approximately 25,000 cpm of 35S activity was loaded into each well of a 12% bis-Tris gel, which was run and analyzed.

Electron microscopy (EM) and quantitation of virion core morphology.

Envelope-free viruses were produced and purified by anion-exchange chromatography, as described previously (46). Purified virions were prepared for thin-section microscopy by the Harvard Medical School Electron Microscopy Facility. Fields containing multiple identifiable virions were selected for analysis. Virions were binned into one of three categories based upon the shape of their electron-dense cores in the sectioning plane: conical cores, well-defined round cores, and unidentifiable “other.”

Fate-of-capsid assays.

Cf2Th cells were seeded into 75-cm2 flasks to achieve 80 to 90% confluence at the time of infection. Flasks were prechilled on ice for 10 min prior to addition of 5 million cpm (RT units) of viruses in a 4-ml volume. Cells and virus were kept at 4°C for a half hour and then transferred to a 37°C incubator (at time zero). The cells were washed and fresh was medium added 4 h after infection. At designated intervals, flasks were chilled on ice and washed three times with ice-cold 1× PBS. Cells were released from the flask by pronase digestion (1 ml of 7-μg/ml pronase in 1× PBS for 5 min at 37°C), transferred to 15-ml conical tubes, and washed three times with 10 ml of cold PBS. The pellet was resuspended in 250 μl of cold hypo-lysis solution (10 mM Tris [pH 8], 10 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA), transferred to Eppendorf tubes, and kept on ice for 15 min. Cells were then mechanically disrupted for 1 min using a pellet pestle (Kontes; catalog number K49540), and the cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 3 min. The resulting supernatant was mixed with 250 μl of fresh hypo-lysis buffer. A 400-μl aliquot of the cell lysate mixture was layered atop a 7-ml column of 50% sucrose–1× PBS in an ultraclear SW41 tube (Beckman Coulter; catalog number 344059), and the remaining lysate was preserved in 1× Laemmli buffer. The column was centrifuged for 2 h at 125,000 × g. The top 100 μl was collected, the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of 1× PBS, and both were brought to a 1× final concentration of Laemmli buffer. Samples were run on 4 to 12% bis-Tris gels, transferred, and probed with a 1:1,000 dilution of an anti-SIVmac251 polyclonal serum (AIDS reagent program number 2773) and a 1:40,000 dilution of goat anti-human horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Sigma; catalog number A0293), followed by detection with femtosensitivity chemiluminescence reagent (Thermo Scientific; catalog number 34095). Densitometry was performed using ImageQuantTL, using a consistent 50-pixel rolling-ball background reduction.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

HeLa cells were seeded into 6-well plates to achieve 80% confluence at the time of infection. Viral suspensions were treated with DNase Turbo (Ambion; catalog number AM2238) according to the manufacturer's protocol for 1 h at 37°C, and then titers were determined by RT assay. Approximately 100,000 cpm of virus, expected to represent a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ∼0.5, was added to each well at time zero. Control viruses were heat inactivated at 56°C for 1 h and then maintained in 100 μM zidovudine (AZT) for the duration of the experiment. Unbound virus was washed off the cells 2 h postinfection. Cells were collected by trypsin digestion 2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h postinfection. Total DNA was extracted by the Wizard SV 96 Genomic System (Promega; catalog number A2371) and quantitated on a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. DNA was diluted to a final concentration of 10 ng/μl using double-distilled autoclaved water. Each quantitative PCR (qPCR) mixture contained 100 ng of total DNA in a 50-μl reaction volume. The accumulation of product was assayed by TaqMan probe on an Applied Biosystems model 7300 apparatus. The primers for each stage of reverse transcription were as follows: early forward, GTC AAC TCG GTA CTC AAT AAT AAG; early reverse, GCG CCA ATC TGC TAG GGA T; early probe, 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-CTG TTA GGA CCC TTT CTG CTT TGG GAA ACC GAA G-6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA); late forward, TTG GGA AAC CGA AGC AGG; late reverse, TCT CTC ACT CTC CTT CAA GTC CCT; late probe, FAM-AAA TCC CTA GAC GAT TGG CGC CTG AA-TAMRA; 2-LTR forward, GGA AAC CGA AGC AGG AAA AT; 2-LTR reverse, CTG TGC CTC ATC TGA TAC; 2-LTR standard probe, FAM-ATT GGC AGG ATT ACA CCT CAG GAC CAG-TAMRA; and 2-LTR junction probe, FAM-ATT CCC TAG CAG ATA CTG GAA GGG AT-TAMRA.

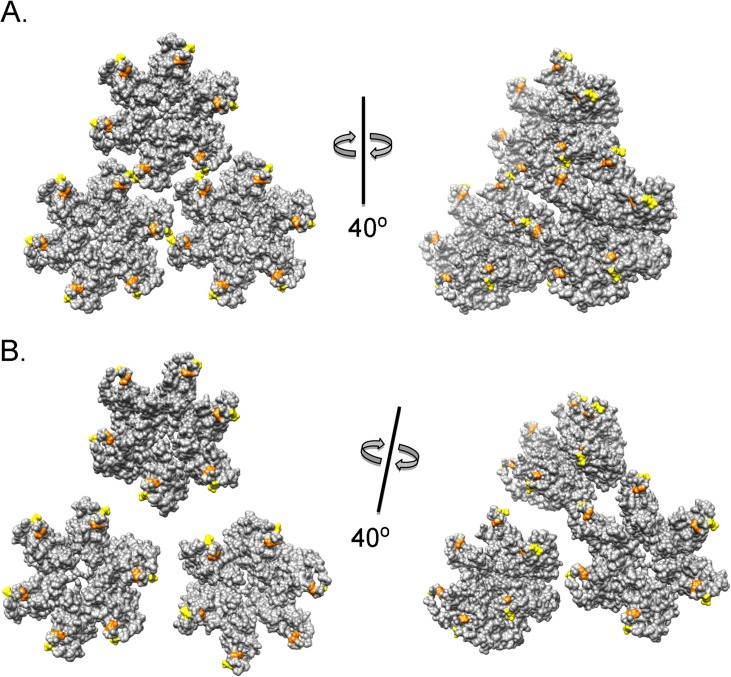

Molecular modeling.

The primary amino acid sequence of the CA protein of HIV-2 isolate D194 was aligned with that of SIVmac239 using ClustalW. This alignment was input into the Match→Align tool in the UCSF Chimera suite (47), utilizing the crystal structure of the HIV-2D194 CA N-terminal domain (2WLV) (34). The resulting SIVmac239 CA model was then aligned to two different HIV-1 capsid hexamer structures (3H4E and 3J34) (7, 48) using Matchmaker (47). The hexameric SIVmac239 capsid model was aligned by hand to match precisely the C-terminal interactions of the published CA lattice without regard to positioning of the N-terminal domains. Molecular graphics images were produced using the UCSF Chimera package from the Computer Graphics Laboratory, University of California, San Francisco.

RESULTS

Mutagenesis of the SIVmac239 CA helix 4-5 loop.

The sequences of primate immunodeficiency virus CA proteins in the helix 4-5 loop are compared in Fig. 1. The group Q viruses lack a glycine-proline pair, which serves as a motif for CypA binding, in this region; however, compared with the group GP viral capsids, the CA helix 4-5 loop of the group Q viruses is rich in glutamine residues. For example, for the primate immunodeficiency viruses listed in Fig. 1, 26.8% of the 13 to 16 residues that constitute the helix 4-5 loop of group Q viruses are glutamine residues, whereas only 9.3% of these residues are glutamine in the group GP viruses. Obviously, these exact percentages are dependent on the particular sample of viruses included in the comparison. Moreover, sequence-based classification may not fully reflect the functional properties of the helix 4-5 loop; for example, the presence of a glycine-proline pair does not guarantee CypA binding. Nonetheless, this comparison serves to call attention to the high frequency of glutamine residues in the CA protein helix 4-5 loop of some SIV strains, particularly in those without a glycine-proline motif.

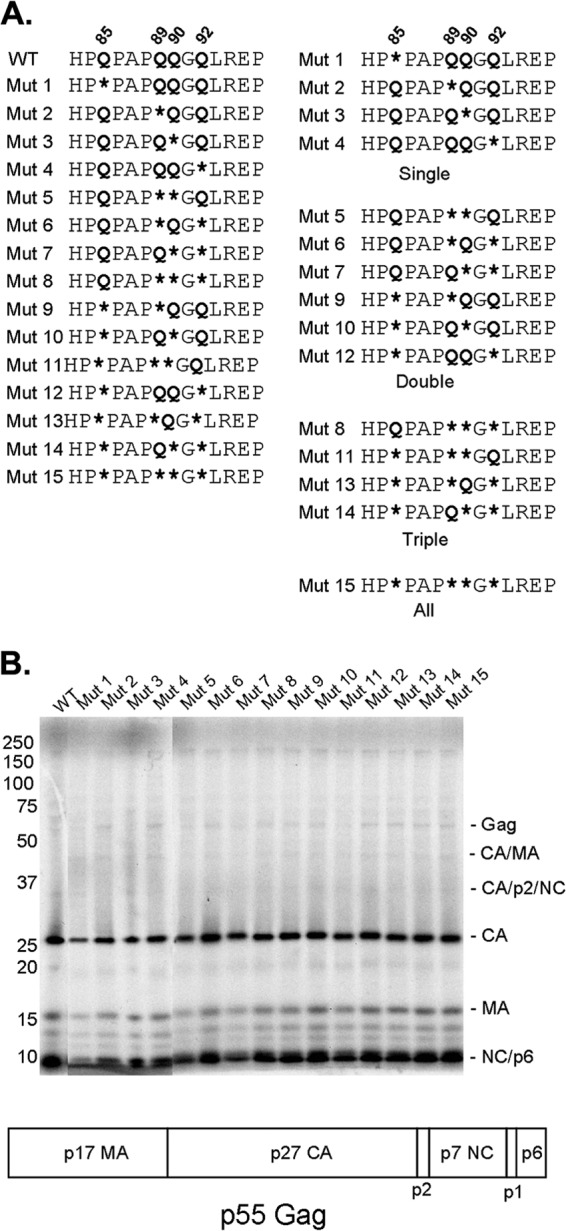

Expression and infectivity of SIVmac239 CA mutants.

We created a panel of SIVmac239 capsid mutants in which the glutamine residues of the helix 4-5 loop were altered to glycine residues, either individually or in combination (Fig. 2A). Glycine substitution was chosen for this study because glycine residues are accommodated well in a surface loop like the helix 4-5 loop. All of the mutant Gag polyproteins were expressed and processed comparably to that of wild-type SIVmac239 (Fig. 2B). The wild-type and mutant proteins produced equivalent levels of virions in the supernatant of expressing cells (Fig. 2B); consistent with this result, similar levels of RT were measured in the supernatant of the cells expressing wild-type and mutant SIVmac239 Gag-Pol polyproteins (data not shown). Thus, none of the CA changes apparently affects the expression or processing of the Gag or Gag-Pol polyproteins or the release of virion particles.

FIG 2.

Expression and processing of SIVmac239 helix 4-5 loop CA mutants. (A) Site-directed mutagenesis was used to alter, singly or in combination, each of four glutamine residues in the SIVmac239 helix 4-5 loop to glycines (represented by asterisks). The glutamine residues (Q85, Q89, Q90, and Q92) are numbered using SIVmac239 residue positions, according to current convention (57). The CA mutants are shown in numerical order in the column on the left; in the column on the right, the mutants are organized according to the number of glutamine residues altered. (B) The processing of the Gag precursor polyprotein was examined by metabolically labeling transfected 293T cells producing wild-type (WT) and mutant SIVmac239 virions. Secreted viruses were collected, purified over a 20% sucrose column, and run on a 12% bis-Tris gel. Loading was normalized by the amount of 35S label. The domain organization of the SIVmac239 p55 Gag precursor polyprotein is illustrated beneath the gel.

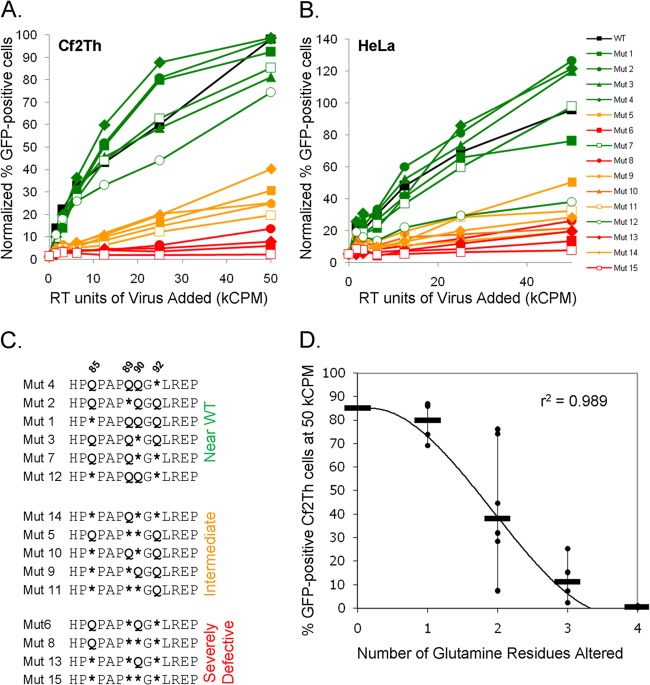

The VSV G-pseudotyped SIVmac239 variants were tested for infectivity on human HeLa cells (Fig. 3A) and canine Cf2Th cells (Fig. 3B). The mutant viruses exhibited a wide range of infectivities, with the infectivity of each mutant consistent for the HeLa and Cf2Th target cells. The mutant viruses were grouped into three classes: those with an infection efficiency close to that of the wild-type SIVmac239, those with intermediate levels of infection, and those exhibiting severely compromised infection efficiency (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that the glutamine residues in the CA helix 4-5 loop play a role in SIVmac239 infection.

FIG 3.

Infection efficiency of mutant viruses. (A and B) VSV-G pseudotypes of the indicated wild-type and mutant SIVmac239 viruses were manufactured in HEK293T cells, normalized for RT activity, and serially diluted before infection of Cf2Th cells (A) and HeLa cells (B). The GFP-positive cells from five independent infections were counted and normalized to the values observed for 50,000 RT units of the wild-type (WT) virus. The infection efficiency of each mutant virus was classified as near wild type (green), intermediate (orange), or severely defective (red). (C) SIVmac239 CA mutants grouped according to infection efficiency. (D) Infection efficiency inversely correlates with the number of altered glutamines. Mutants with two altered glutamines exhibit a wide range of phenotypes. The bar indicates the median for each category. Third-order polynomial regression (r2) was 0.989.

The observed decreases in infectivity were related to the number of glutamine residues altered (Fig. 3D). The wide range of infectivities exhibited by the mutants with two of the helix 4-5 loop glutamine residues altered suggests that specific glutamine residues may be more important than others. Of the four glutamine residues in the helix 4-5 loop of the SIVmac239 CA protein, Gln 89 makes the biggest contribution to infectivity. When Gln 89 was altered to glycine, a glutamine residue at position 92 was apparently required for retention of infectivity (Fig. 3C). The glutamine residues at 89 and 92 independently contributed to SIVmac239 infectivity, suggesting that they perform nonredundant functions. Thus, the glutamine residues in the helix 4-5 loop of the SIVmac239 CA protein contribute in aggregate, and in some cases individually, to virus infectivity.

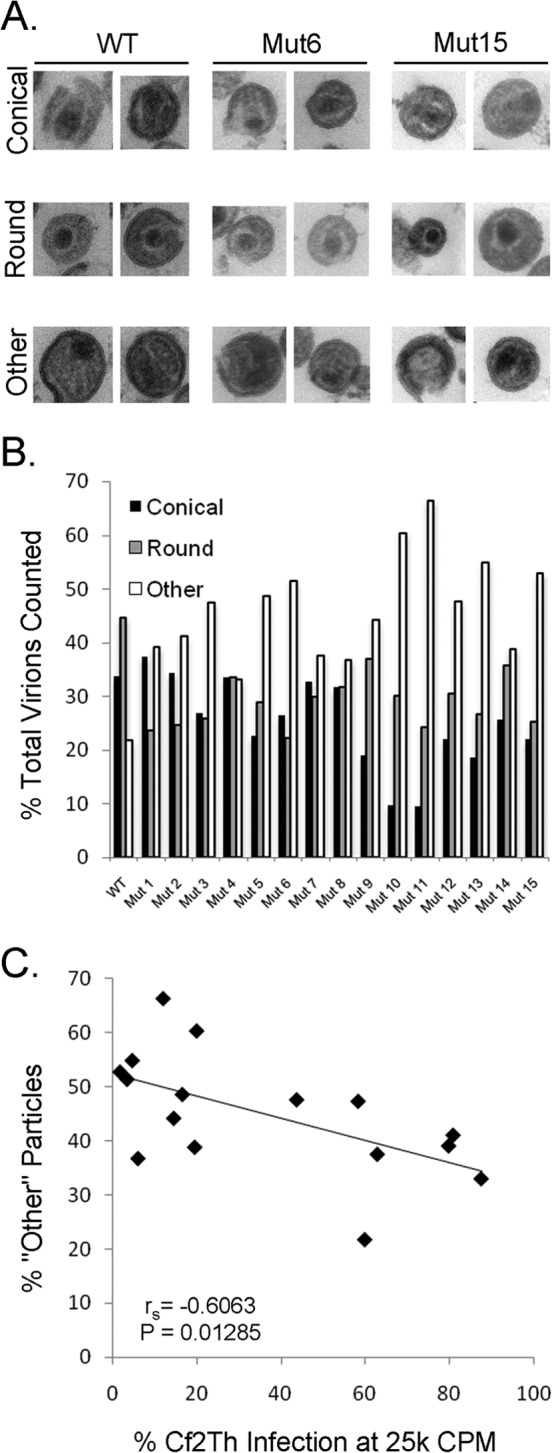

Capsid morphology.

The morphology of the wild-type and mutant capsids was examined by electron microscopy (EM). Virions were produced in 293T cells and purified by anion-exchange chromatography, a method known to preserve infectivity (46). The purified virions were pelleted, stained, and sectioned for transmission EM. Fields containing viruses were imaged, and individual virion particles were classified as containing either well-defined conical or round cores, or as “other” when such cores were not apparent (Fig. 4A). All of the mutant viruses exhibited increased counts of other particles at the expense of those with defined conical or round cores (Fig. 4B). The percentage of other particles was inversely related to the infectivity of the viruses (Spearman rank correlation coefficient [rS] = −0.6063; P = 0.01285 [two-tailed test]) (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that the glutamine residues in the CA helix 4-5 loop contribute to the condensation of the SIVmac239 capsid, which, in turn, is important for the infectivity of the viruses.

FIG 4.

Capsid morphology of the SIVmac239 mutants. (A) Viruses lacking envelope glycoproteins were manufactured, purified, and stained for EM imaging, as detailed in Materials and Methods. The morphology of the virion cores was analyzed. If a virion was sectioned to reveal a conical core in a particle ∼100 nm in diameter, it was scored as conical. If the virion section revealed a well-defined core that was not conical, it was scored as round. If the sectioned virion contained no defined core, or a core of improper size, it was scored as “other.” Examples of conical, round, and other cores for WT and selected mutant virions are shown. (B) Distribution of core morphologies for WT and mutant virions. For WT virions, n = 166; between 162 and 297 virion particles were scored for each mutant. (C) Inverse correlation between the percentage of virion particles scored as other and the replication efficiency of the mutants in Cf2Th target cells (for an input of 25,000 RT units of virus). Spearman rS = −0.6063; P = 0.01285 (two-tailed test).

Fate of the capsid in infected cells.

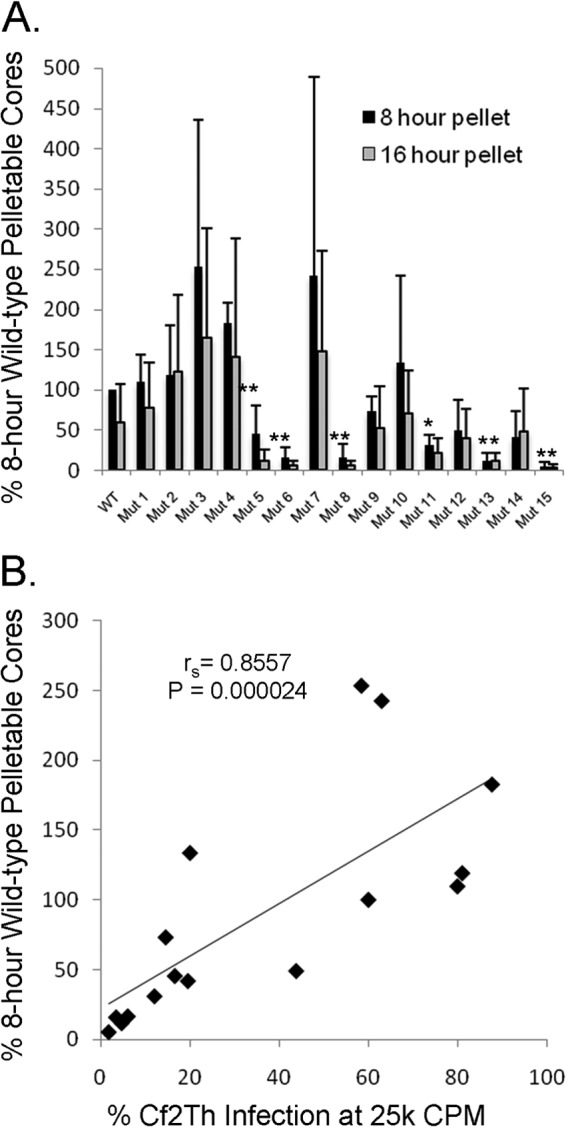

The fate of the wild-type and mutant capsids in the cytosol of cells infected 8 or 16 h previously was examined. Viruses with “near-wild-type” levels of infectivity exhibited capsid stabilities similar to those observed in wild-type SIVmac239-infected cells (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the “severely defective” viruses Mut 6, Mut 8, Mut 13, and Mut 15 all exhibited significantly less pelletable capsid at 8 and 16 h postinfection. “Intermediate” viruses Mut 5 and Mut 11 also exhibited less pelletable capsid than wild-type SIVmac239. The amount of particulate capsid in the cytosol of infected cells correlated with viral infectivity (Spearman rS = 0.8557; P = 0.000024 [two-tailed test]) (Fig. 5B). Thus, the glutamine residues in the helix 4-5 loop of the SIVmac239 CA protein contribute to capsid stability in infected cells.

FIG 5.

Fate-of-capsid assay. (A) Cf2Th cells were infected by wild-type and mutant viruses, as described in Materials and Methods. At 8 and 16 h after infection, cells were disrupted and the amount of pelletable CA protein in cytosolic lysates was measured. Results from three independent infections were normalized to those obtained for the wild-type virus at 8 h after infection. Significant differences in the amount of pelletable CA protein between WT and mutant viruses are indicated by single asterisks for a P value of <0.05 and double asterisks for a P value of <0.01. (B) Correlation between the amount of pelletable CA protein at 8 h after infection and the infectivity of the viruses in Cf2Th cells. Spearman rS = 0.8557; P = 0.000024 (two-tailed test).

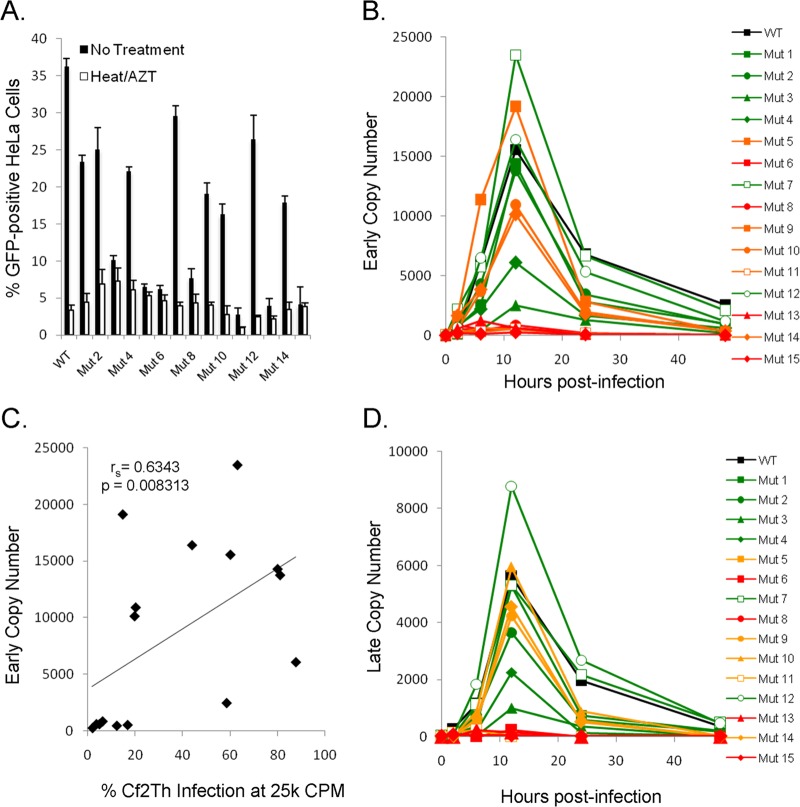

Reverse transcription and nuclear import of viral cDNA.

Decreases in the stability of retroviral capsids often result in defective reverse transcription of viral genomic RNA (11, 14). We followed the progress of reverse transcription in cells infected by the wild-type and mutant viruses. We controlled for any contaminating carryover DNA from the transfected, virus-producing cells by including a parallel experimental arm in which the viruses were heat inactivated and the cells were AZT treated (Fig. 6A). The infectivity of most of the mutant viruses was consistent with that in previous experiments, although Mut 3, Mut 5, and Mut 11 exhibited lower infectivity in these experiments (Fig. 6A). None of the “severely defective” viruses produced detectable levels of “early” strong-stop viral cDNA or “late” complete genomic cDNA (Fig. 6B and D). The infectivity of the entire panel of SIVmac239 variants correlated with the level of early reverse transcripts at 12 h postinfection (Spearman rS = 0.6343; P = 0.008313 [two-tailed test]) (Fig. 6C). These results indicate that some alterations of the glutamine residues in the helix 4-5 loop of the SIVmac239 CA protein result in reverse transcription defects.

FIG 6.

Viral cDNA synthesis. (A) Three independent wells of HeLa cells were infected with wild-type and mutant GFP-expressing viruses at an MOI of 0.5. Total DNA was extracted from the cells at 0, 2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h following infection. Cells were assessed by FACS for GFP expression at 48 h postinfection. (B) One hundred nanograms of total DNA was used in quantitative real-time PCR assays. The early primer set measures the amount of plus-strand strong-stop DNA. The symbols for the mutants are colored according to replication efficiency, as in Fig. 3C. The correlation between the level of early reverse transcripts at 10 h postinfection and virus infection efficiency is shown. Spearman rS = 0.6343; P = 0.008313 (two-tailed test). (D) The late primer set measures the amount of completely reverse-transcribed genomes.

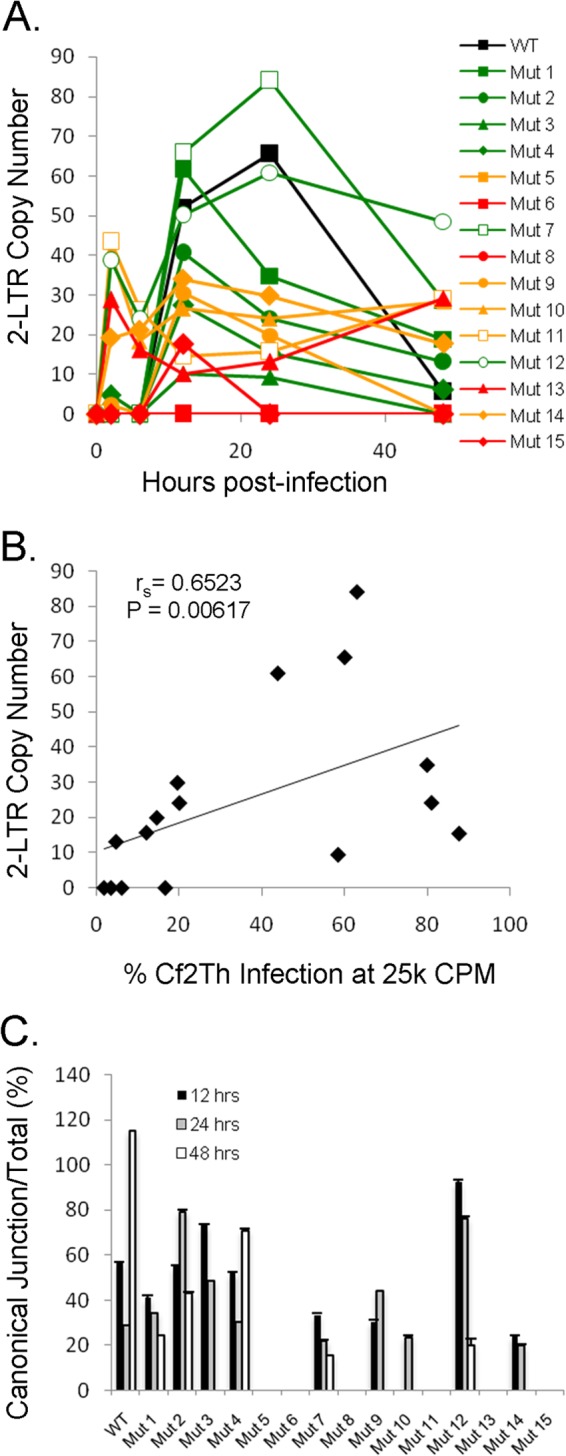

The levels of 2-LTR circular viral DNA products were reduced for the severely defective viral mutants compared with those of the wild-type virus (Fig. 7A). The number of copies of 2-LTR circles in the infected cells correlated with the infectivity of the panel of SIVmac239 variants (Fig. 7B).

FIG 7.

Production of 2-LTR circles of viral DNA. (A) HeLa cells infected with wild-type and mutant GFP-expressing viruses were used as a source of DNA for quantitative real-time PCR assays, as described in the legend to Fig. 6. The 2-LTR primer set measures the amount of viral 2-LTR junctions, autointegrants, and minigenomes present in the cell. (B) Correlation between the level of 2-LTR DNA products at 25 h after infection and viral infection efficiency. Spearman rS = 0.6523; P = 0.00617 (two-tailed test). (C) The percentage of canonical 2-LTR junctions, compared with the standard, amplified at 12, 24, and 48 h after infection is shown. All viruses that completed reverse transcription produced canonical junctions.

Our previous studies indicated that the standard 2-LTR primer set does not discriminate between true 2-LTR circles and episomal reverse-transcribed products that arise as a result of other processes, notably autointegration (15). To determine if the altered viruses produce canonical 2-LTR circles, we performed an assay for 2-LTR circles using a probe that spans the 2-LTR junction that results from properly processed and ligated double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) genomes. In previous work (15), we found that the population of 2-LTR circles at the 24-h peak of copy number from a wild-type SIVmac239 infection contains about 20 to 30% canonical junctions, and this was corroborated in this set of experiments (Fig. 7C). In the present study, those viruses with measurable 2-LTR circles exhibited a percentage of canonical 2-LTR circles consistent with that of the wild-type virus (Fig. 7C). Thus, we found no evidence of increased autointegration, failure to properly process the viral cDNA genome, or failure to enter the nucleus for the subset of altered viruses that successfully negotiated the early phase of infection.

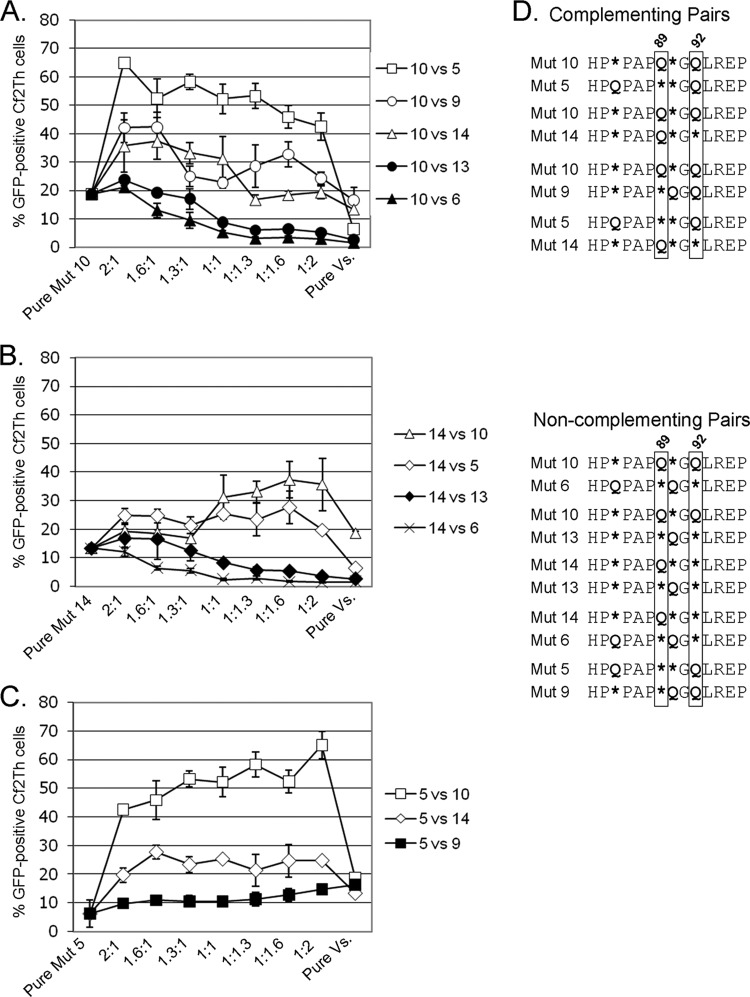

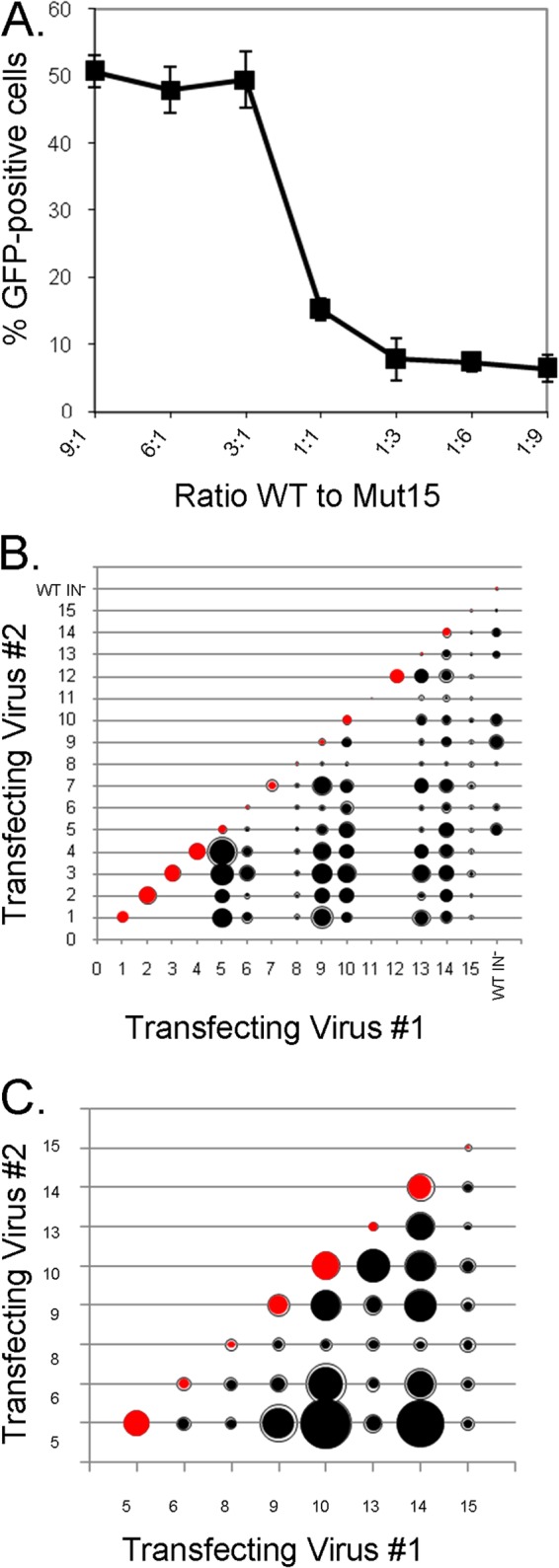

Complementation of mutants.

Given the oligomeric nature of the assembled capsid and the apparent involvement of the helix 4-5 loop glutamines in capsid condensation and stability, we tested the hypothesis that the CA mutants could complement one another in trans. To that end, we cotransfected the mutants pairwise to produce chimeric viruses and tested their infectivity. In a pilot experiment, we made several chimeric viruses containing wild-type SIVmac239 CA and Mut 15 at different ratios to determine if any resulting trans-complementation was cooperative (Fig. 8A). At 3:1 and 1:3 ratios of wild-type to Mut 15 CA proteins, and at the more extreme ratios, the chimeric viruses exhibited the phenotype of the majority capsid. The inflection between the 3:1 and 1:3 ratios suggested that the phenotype being assessed was cooperative and sensitive to disruption by less-than-equimolar amounts of the defective CA protein.

FIG 8.

Complementation analysis. (A) In a pilot experiment, chimeric viruses were produced by transfecting the indicated ratios of wild type to Mut 15 virus DNA into HEK293T cells. The VSV-G-pseudotyped hybrid viruses were used to infect Cf2Th cells. GFP was measured in the cells 48 h later. (B) Three independent 1:1 transfections of the indicated mutants or of mutant and wild-type integrase-deficient pSIVmac239ΔnefΔenvEGFP DNA into HEK293T cells were performed to make hybrid viruses, and 12,500 cpm (RT units) of each virus preparation was used to infect Cf2Th cells. The relative infection efficiency of the mutants is proportionate to the diameter of the inner circle. Standard deviations, where large enough to be visible, are represented as an exterior ring. (C) The infection efficiencies are depicted (as in panel B) for hybrid viruses composed of 1:1 ratios of CA mutants with intermediate or severely defective infection efficiencies.

We then tested 1:1 ratios of CA from intermediate and severely defective viruses with similarly defective and “near-wild-type” viruses. We also evaluated the infection efficiency of viruses made by coexpression of helix 4-5 mutants with an integrase-defective (D64V) virus that had a wild-type CA to assess whether the virion particles generated by cotransfection were indeed chimeric. Chimeras between the intermediate mutants (Mut 5, Mut 9, and Mut 10) and the D64V virus were more infectious than either parent virus, indicating that their cores had been assembled from both constructs. As observed with the pilot experiment with wild-type and Mut 15 capsids, the presence of the severely defective Mut 8 or Mut 15 at a 1:1 ratio poisoned the infectivity of the chimeric capsid, although the severely defective Mut 6 and Mut 13 capsids exhibited a low level of complementation by the wild-type CA (Fig. 8B). To identify complementation groups of the mutant CA proteins, we focused on the chimeras between capsids of viruses with intermediate or severely defective phenotypes, looking for infectivity that exceeded that of either parent virus (Fig. 8C). We selected the mutant pairs Mut 5/Mut 9, Mut 5/Mut 10, Mut 5/Mut 14, Mut 6/Mut 10, Mut 6/Mut 14, Mut 9/Mut 10, Mut 10/Mut 13, Mut 10/Mut 14, and Mut 13/Mut 14 for further study.

To verify the mutant complementation and to examine the sensitivity of any observed cooperativity to the ratios of the mutants, we performed the complementation experiment using a range of mutant ratios. Mut 10 had the most complementation partners. Pairing Mut 10 with Mut 5 produced the highest level of infection efficiency above the parental viruses, and both Mut 9 and Mut 14 were also Mut 10 complementation partners (Fig. 9A). On the other hand, neither Mut 6 nor Mut 13 efficiently complemented Mut 10. Mut 14 was another broadly complementing virus; Mut 14 was complemented by Mut 5 and Mut 10, though not by Mut 6 or Mut 13 (Fig. 9B). The infectivity of the complementing chimeras with Mut 14 appeared to benefit from higher ratios of Mut 5 and Mut 10. Finally, as shown above, Mut 5 was strongly complemented by Mut 10 and less so by Mut 14; Mut 5 was not complemented by Mut 9 (Fig. 9C).

FIG 9.

Infectivity complementation over a range of mutant ratios. (A) Mut 10 DNA was cotransfected at the indicated ratios with DNA for Mut 5, 6, 9, 13, and 14 into HEK293T cells. Hybrid viruses were used to infect Cf2Th cells and 48 h later, GFP expression in the target cells was measured. (B) The complementation of Mut 14 and Mut 10, 5, 13, and 6 was examined, as described for panel A. (C) The complementation of Mut 5 and Mut 10, 14, and 9 was examined, as described for panel A. (D) Analysis of the complementing pairs suggests that having Q89 available on one of the capsids and Q92 on the other leads to complementation. Mutant pairs that rely upon a single mutant to provide both Q89 and Q92, or pairs that lack either one, do not complement.

We aligned the helix 4-5 loop sequences of complementing and noncomplementing mutant CA pairs to determine if rules to explain the observed phenotypes could be deduced. Complementing viruses apparently require one capsid with glutamine 89 and the other capsid with glutamine 92 (Fig. 9D). Having both of these glutamine residues on the same chain in cis, as in the chimeric Mut 6/Mut 10 virus, is not sufficient for effective complementation. Complementing viruses do not require glutamine 85 or glutamine 90. These results underscore the importance of the glutamine residues at positions 89 and 92 in the CA helix 4-5 loop, both of which are lacking in the severely defective subset of mutants.

Capsid modeling.

The severely defective phenotype of Q89G/Q92G viruses suggested that these residues play a critical role in the stability of the SIVmac239 capsid. To understand these phenotypes at the structural level, we modeled the SIVmac239 capsid by threading the sequence into the published structure of the HIV-2 capsid (34), using the Match→Align feature in UCSF Chimera (47). In the resulting model, glutamine 92 is within H-bonding distance of glutamine 119, which is located on the loop between helices 6 and 7. The interaction between glutamine 92 and glutamine 119 supports the entire helix 4-5 loop on the CA N-terminal domain. In contrast to glutamine 92, glutamine 89 is solvent exposed and does not have an obvious partner on the same CA monomer. However, a plausible role for glutamine 89 became apparent when six SIVmac239 CA monomers were modeled onto HIV-1 hexamer structures (7, 48), using the Matchmaker tool in Chimera. In the context of the capsid lattice, glutamine 89 and glutamine 92 are located at the distal end of the hexameric spokes and thus are well situated to promote interhexamer interactions (Fig. 10). Loss of interactions involving glutamine 89 and glutamine 92 may be compensated by other helix 4-5 loop interactions, as Mut 2 (Q89G) and Mut 4 (Q92G) efficiently support viral infection. Glutamine 90 might partially compensate for the absence of glutamine 89 in some contexts; for example, of the severely defective mutants, Mut 6 and Mut 13 appear to be slightly more amenable to complementation than Mut 8 and Mut 15, perhaps due to their preservation of glutamine 90. Consistent with the possibility that glutamine 90 can compensate to some degree for the absence of glutamine 89, Mut 5 and Mut 11, which exhibit the lowest levels of particulate capsid in infected cells among the intermediate viruses, lack both glutamine 89 and glutamine 90. Thus, in our model, loss of both inter- and intrahexamer interactions involving these residues cripples SIVmac239 by denying the capsid the necessary cohesion to negotiate the early postentry events that lead to the initiation of reverse transcription.

FIG 10.

Structural explanation for the SIVmac239 CA mutant phenotypes. The amino acid sequence of the SIVmac239 CA protein was threaded into the crystal structure of the HIV-2 capsid (2WLV) (34). This structure was then aligned with models of the HIV-1 hexamer (3H4E [A] and 3J34 [B] [7, 48]) using the Matchmaker tool in Chimera (47). SIVmac239 hexamers were assembled into a lattice by alignment with the HIV-1 capsid models, matching critical interactions between the CA C-terminal domains. In panel A, the interactions of the capsid hexamers occur in a plane orthogonal to the axis of 3-fold pseudosymmetry. In panel B, the capsid model exhibits curvature, as might be seen in the mature assembled capsid. Both models are shown from two perspectives to emphasize the differing hexamer relationships. Glutamine residues 89 (yellow) and 92 (orange) could contribute to interhexamer interactions around the 3-fold pseudosymmetry axis that stabilize the capsid lattice. Such interactions may be particularly important during initial nucleation of the capsid assembly in the virion, as in panel A.

DISCUSSION

The helix 4-5 loop of retroviral CA proteins is exposed on the surface of the mature assembled capsid and thus can potentially contribute to interactions between CA proteins and between CA and host cell factors. This study was motivated by the observation that the helix 4-5 loop of primate immunodeficiency virus CA proteins could be classified into two groups: (i) group GP CA proteins with a glycine-proline pair, which is often used by CypA as a binding site (23), and (ii) group Q CA proteins lacking a glycine-proline pair but rich in glutamine residues. We show that some alterations of the glutamine residues in SIVmac239, a group Q virus, resulted in decreased capsid condensation, decreased levels of particulate capsids in the cytosol of infected cells, and reduced efficiency of reverse transcription and infection. These phenotypes can be explained by a decrease in capsid stability, possibly through a loss of interactions between CA molecules or between CA and a host capsid-stabilizing factor. Alteration of the glutamine residues in the helix 4-5 loop did not affect virus assembly, virion release, or the proteolytic processing of the Gag precursor. However, at the point where the mature wild-type SIVmac239 CA proteins condense into a dense conical core, the glutamine mutants apparently pack less efficiently, leading to virions with a lower frequency of well-defined cores. Following virus entry, several of the glutamine mutants exhibited decreased levels of particulate capsids in the cytosol of infected cells, a phenotype consistent with decreased capsid stability. These capsid stability-related phenotypes were inversely correlated with viral infectivity. Alterations in capsid structure could hypothetically affect multiple steps in the early phase of SIVmac239 infection. As previously seen (11, 14), significant decreases in SIVmac239 capsid stability were associated with inefficient reverse transcription, providing a likely explanation for the replication defects. For the partially replication-defective mutants that formed some reverse transcripts, no obvious abnormalities in 2-LTR circles were evident, suggesting that nuclear import was successful and autointegration was kept within normal limits.

Of the four glutamine residues in the SIVmac239 CA helix 4-5 loop, alteration of glutamine 89 and glutamine 92 exerted the largest impact on SIVmac239 infectivity. The levels of replication defectiveness of the mutants and the patterns of complementation suggest that glutamine 89 and glutamine 92 play nonredundant roles in CA function. Modeling suggests that glutamine 89 and glutamine 92 are poised to regulate interhexamer interactions (9, 30, 49–51) (Fig. 10). Such interactions may be particularly important during the nucleation of the mature capsid in the virion. As newly formed CA hexamers are added to the growing edge of the capsid, the glutamine residues in the helix 4-5 loops may be positioned so that hexamer-hexamer interactions are promoted (Fig. 10A). As the assembling capsid assumes curvature, the distances between the helix 4-5 loops on adjacent hexamers may increase beyond those that would allow direct interhexamer bonding (Fig. 10B). Nonetheless, the helix 4-5 loops are well positioned to interact with host factors (48). Helix 4-5 loops are often rich in prolines, which opens the possibility of switching conformation by cis-trans isomerization by prolyl isomerases like CypA. Conformational switching may regulate CA-CA interactions in different contexts that require greater or lesser capsid stability.

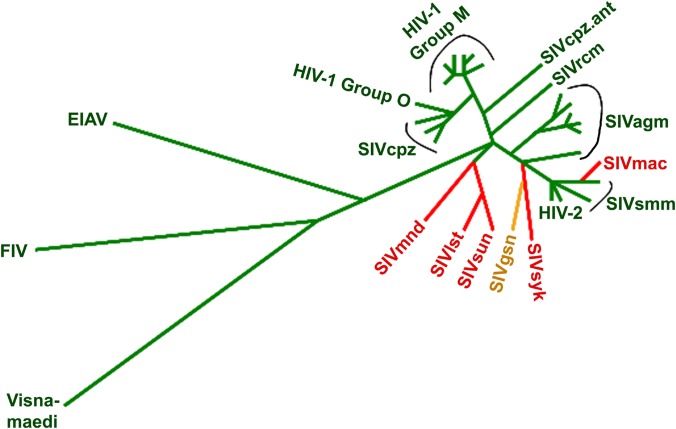

The group GP and group Q viruses do not segregate in a simple pattern on a phylogenetic tree of lentivirus evolution (Fig. 11). How might the evolution of these two CA groups be explained? The presence of glycine-proline pairs and the ability to bind CypA or TRIMCyp are properties of divergent lentiviruses like HIV-1 and feline immunodeficiency virus and thus are likely ancestral (19, 52). Consistent with this, the GP group of primate immunodeficiency viruses is quite diverse. According to this model, certain lineages of SIVs found it advantageous to lose the glycine-proline motif that allows interaction with CypA. As CypA can promote capsid stability (18), these viruses may have had to evolve other means of stabilizing their capsids, such as a glutamine-rich helix 4-5 loop.

FIG 11.

Phylogenetic tree of lentivirus gag genes. The phylogenetic tree of gag gene sequences of the indicated lentiviruses, adapted from reference 57, is shown. Group GP viruses, which contain a glycine-proline pair in the CA helix 4-5 loop, are colored green. Group Q viruses, with a glutamine-rich helix 4-5 loop, are colored red. The SIVgsn helix 4-5 loop cannot be assigned to either group.

What drove the evolution of certain SIV lineages away from the group GP capsids to the group Q capsids? Although we can only speculate about the causes in the case of many SIVs, one well-documented example provides insight. SIVsmm, indigenous to sooty mangabeys in West Africa, was transmitted to captive Asian macaques in recent history, evolving to the pathogenic SIVmac and SIVmne viruses (5, 6). SIVsmm is a group GP virus, with a glycine-proline pair and two glutamine residues in the helix 4-5 loop. SIVmac and SIVmne are group Q viruses in which an alanine-proline pair replaces the glycine-proline pair, with four and five glutamine residues, respectively, in the helix 4-5 loop. Of interest, SIVmac and SIVmne evolved in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) and pigtail macaques (Macaca fascicularis), respectively, two monkey species that express TRIMCyp restriction factors (38, 53–55). One SIVsmm isolate, SIVsmE543, was shown to be restricted by rhesus macaque TRIMCyp, but it became resistant to TRIMCyp when a Q89 Q90 substitution was introduced into its CA protein (36). It is noteworthy that the CA proteins of both SIVmac and SIVmne have the glutamine-glutamine pair at positions 89 and 90. Thus, after cross-species transmission of the group GP SIVsmm, TRIMCyp in the new hosts likely drove the evolution of the group Q SIVmac and SIVmne viruses (56). Restriction factors like TRIMCyp or TRIM5α may likewise have provided selection pressure for the evolution of group Q SIVs in other monkey species.

All of the primate immunodeficiency viruses that infect apes and humans are group GP viruses. These ape and human viruses evolved from SIVs with CA helix 4-5 loop sequences that required little change in adapting to the new host species. SIVsmm, the direct precursor of HIV-2, is already a group GP virus. SIVcpz, the direct precursor of HIV-1, originated through a recombination event in chimpanzees between SIVrcm and SIVgsn (3). Both of these SIVs presumably had to replicate efficiently in chimpanzees to allow this recombination event to occur. SIVrcm is already a group GP virus, so it likely required minimal modification of the helix 4-5 loop for adaptation to chimpanzees. SIVgsn has properties of both group GP and group Q viruses. The SIVgsn helix 4-5 loop lacks a glycine-proline pair but has an alanine-proline pair; unlike the group Q viruses, SIVgsn has only one or two glutamine residues in the helix 4-5 loop and is sensitive to restriction by some TRIMCyp proteins (37). Thus, the helix 4-5 loop of the SIVgsn CA protein would apparently require few modifications to allow adaptation to chimpanzees.

Further study of the evolution and function of the CA helix 4-5 loop should provide further insights into its role in primate immunodeficiency virus cross-species transmission and pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yvette McLaughlin and Elizabeth Carpelan for manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant AI063987 and Center for AIDS Research Award AI06354), the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, and the late William F. McCarty-Cooper. C.T. was supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32 AI07245). The Computer Graphics Laboratory, University of California, San Francisco, which is the source of the UCSF Chimera package used in this study, is supported by NIH grant P41 RR-01081.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 2 July 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus H. 1997. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharp PM, Hahn BH. 2011. Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 1:a006841. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailes E, Gao F, Bibollet-Ruche F, Courgnaud V, Peeters M, Marx PA, Hahn BH, Sharp PM. 2003. Hybrid origin of SIV in chimpanzees. Science 300:1713. 10.1126/science.1080657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn BH, Shaw GM, De Cock KM, Sharp PM. 2000. AIDS as a zoonosis: scientific and public health implications. Science 287:607–614. 10.1126/science.287.5453.607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apetrei C, Kaur A, Lerche NW, Metzger M, Pandrea I, Hardcastle J, Falkenstein S, Bohm R, Koehler J, Traina-Dorge V, Williams T, Staprans S, Plauche G, Veazey RS, McClure H, Lackner AA, Gormus B, Robertson DL, Marx PA. 2005. Molecular epidemiology of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsm in U.S. primate centers unravels the origin of SIVmac and SIVstm. J. Virol. 79:8991–9005. 10.1128/JVI.79.14.8991-9005.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apetrei C, Lerche NW, Pandrea I, Gormus B, Silvestri G, Kaur A, Robertson DL, Hardcastle J, Lackner AA, Marx PA. 2006. Kuru experiments triggered the emergence of pathogenic SIVmac. AIDS 20:317–321. 10.1097/01.aids.0000206498.71041.0e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pornillos O, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Kelly BN, Hua Y, Whitby FG, Stout CD, Sundquist WI, Hill CP, Yeager M. 2009. X-ray structures of the hexameric building block of the HIV capsid. Cell 137:1282–1292. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byeon IJ, Meng X, Jung J, Zhao G, Yang R, Ahn J, Shi J, Concel J, Aiken C, Zhang P, Gronenborn AM. 2009. Structural convergence between cryo-EM and NMR reveals intersubunit interactions critical for HIV-1 capsid function. Cell 139:780–790. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mortuza GB, Haire LF, Stevens A, Smerdon SJ, Stoye JP, Taylor IA. 2004. High-resolution structure of a retroviral capsid hexameric amino-terminal domain. Nature 431:481–485. 10.1038/nature02915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganser BK, Cheng A, Sundquist WI, Yeager M. 2003. Three-dimensional structure of the M-MuLV CA protein on a lipid monolayer: a general model for retroviral capsid assembly. EMBO J. 22:2886–2892. 10.1093/emboj/cdg276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hulme AE, Perez O, Hope TJ. 2011. Complementary assays reveal a relationship between HIV-1 uncoating and reverse transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:9975–9980. 10.1073/pnas.1014522108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee K, Ambrose Z, Martin TD, Oztop I, Mulky A, Julias JG, Vandegraaff N, Baumann JG, Wang R, Yuen W, Takemura T, Shelton K, Taniuchi I, Li Y, Sodroski J, Littman DR, Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Unutmaz D, Engelman A, KewalRamani VN. 2010. Flexible use of nuclear import pathways by HIV-1. Cell Host Microbe 7:221–233. 10.1016/j.chom.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaller T, Ocwieja KE, Rasaiyaah J, Price AJ, Brady TL, Roth SL, Hue S, Fletcher AJ, Lee K, KewalRamani VN, Noursadeghi M, Jenner RG, James LC, Bushman FD, Towers GJ. 2011. HIV-1 capsid-cyclophilin interactions determine nuclear import pathway, integration targeting and replication efficiency. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002439. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi J, Zhou J, Shah VB, Aiken C, Whitby K. 2011. Small-molecule inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection by virus capsid destabilization. J. Virol. 85:542–549. 10.1128/JVI.01406-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tipper C, Sodroski J. 2013. Enhanced autointegration in hyperstable simian immunodeficiency virus capsid mutants blocked after reverse transcription. J. Virol. 87:3628–3639. 10.1128/JVI.03239-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Kar AK, Sodroski J. 2009. Target cell type-dependent modulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid disassembly by cyclophilin A. J. Virol. 83:10951–10962. 10.1128/JVI.00682-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henning MS, Morham SG, Goff SP, Naghavi MH. 2010. PDZD8 is a novel Gag-interacting factor that promotes retroviral infection. J. Virol. 84:8990–8995. 10.1128/JVI.00843-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guth CA, Sodroski J. 2014. Contribution of PDZD8 to stabilization of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid. J. Virol. 88:4612–4623. 10.1128/JVI.02945-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz-Griffero F, Kar A, Lee M, Stremlau M, Poeschla E, Sodroski J. 2007. Comparative requirements for the restriction of retrovirus infection by TRIM5alpha and TRIMCyp. Virology 369:400–410. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.08.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stremlau M, Perron M, Lee M, Li Y, Song B, Javanbakht H, Diaz-Griffero F, Anderson DJ, Sundquist WI, Sodroski J. 2006. Specific recognition and accelerated uncoating of retroviral capsids by the TRIM5alpha restriction factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:5514–5519. 10.1073/pnas.0509996103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sayah DM, Sokolskaja E, Berthoux L, Luban J. 2004. Cyclophilin A retrotransposition into TRIM5 explains owl monkey resistance to HIV-1. Nature 430:569–573. 10.1038/nature02777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J, Tipper C, Sodroski J. 2011. Role of TRIM5alpha RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligase activity in capsid disassembly, reverse transcription blockade, and restriction of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 85:8116–8132. 10.1128/JVI.00341-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vajdos FF, Yoo S, Houseweart M, Sundquist WI, Hill CP. 1997. Crystal structure of cyclophilin A complexed with a binding site peptide from the HIV-1 capsid protein. Protein Sci. 6:2297–2307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aberham C, Weber S, Phares W. 1996. Spontaneous mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene that affect viral replication in the presence of cyclosporins. J. Virol. 70:3536–3544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sokolskaja E, Sayah DM, Luban J. 2004. Target cell cyclophilin A modulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity. J. Virol. 78:12800–12808. 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12800-12808.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Javanbakht H, Diaz-Griffero F, Yuan W, Yeung DF, Li X, Song B, Sodroski J. 2007. The ability of multimerized cyclophilin A to restrict retrovirus infection. Virology 367:19–29. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.04.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bichel K, Price AJ, Schaller T, Towers GJ, Freund SM, James LC. 2013. HIV-1 capsid undergoes coupled binding and isomerization by the nuclear pore protein NUP358. Retrovirology 10:81. 10.1186/1742-4690-10-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Nunzio F, Danckaert A, Fricke T, Perez P, Fernandez J, Perret E, Roux P, Shorte S, Charneau P, Diaz-Griffero F, Arhel NJ. 2012. Human nucleoporins promote HIV-1 docking at the nuclear pore, nuclear import and integration. PLoS One 7:e46037. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin DH, Zimmermann S, Stuwe T, Stuwe E, Hoelz A. 2013. Structural and functional analysis of the C-terminal domain of Nup358/RanBP2. J. Mol. Biol. 425:1318–1329. 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mamede JI, Sitbon M, Battini JL, Courgnaud V. 2013. Heterogeneous susceptibility of circulating SIV isolate capsids to HIV-interacting factors. Retrovirology 10:77. 10.1186/1742-4690-10-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Billich A, Hammerschmid F, Peichl P, Wenger R, Zenke G, Quesniaux V, Rosenwirth B. 1995. Mode of action of SDZ NIM 811, a nonimmunosuppressive cyclosporin A analog with activity against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1: interference with HIV protein-cyclophilin A interactions. J. Virol. 69:2451–2461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin TY, Emerman M. 2006. Cyclophilin A interacts with diverse lentiviral capsids. Retrovirology 3:70. 10.1186/1742-4690-3-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thali M, Bukovsky A, Kondo E, Rosenwirth B, Walsh CT, Sodroski J, Gottlinger HG. 1994. Functional association of cyclophilin A with HIV-1 virions. Nature 372:363–365. 10.1038/372363a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Price AJ, Marzetta F, Lammers M, Ylinen LM, Schaller T, Wilson SJ, Towers GJ, James LC. 2009. Active site remodeling switches HIV specificity of antiretroviral TRIMCyp. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16:1036–1042. 10.1038/nsmb.1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owens CM, Song B, Perron MJ, Yang PC, Stremlau M, Sodroski J. 2004. Binding and susceptibility to postentry restriction factors in monkey cells are specified by distinct regions of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid. J. Virol. 78:5423–5437. 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5423-5437.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirmaier A, Wu F, Newman RM, Hall LR, Morgan JS, O'Connor S, Marx PA, Meythaler M, Goldstein S, Buckler-White A, Kaur A, Hirsch VM, Johnson WE. 2010. TRIM5 suppresses cross-species transmission of a primate immunodeficiency virus and selects for emergence of resistant variants in the new species. PLoS Biol. 8:e1000462. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kratovac Z, Virgen CA, Bibollet-Ruche F, Hahn BH, Bieniasz PD, Hatziioannou T. 2008. Primate lentivirus capsid sensitivity to TRIM5 proteins. J. Virol. 82:6772–6777. 10.1128/JVI.00410-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson SJ, Webb BL, Ylinen LM, Verschoor E, Heeney JL, Towers GJ. 2008. Independent evolution of an antiviral TRIMCyp in rhesus macaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:3557–3562. 10.1073/pnas.0709003105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braaten D, Franke EK, Luban J. 1996. Cyclophilin A is required for the replication of group M human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and simian immunodeficiency virus SIV(CPZ)GAB but not group O HIV-1 or other primate immunodeficiency viruses. J. Virol. 70:4220–4227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braaten D, Luban J. 2001. Cyclophilin A regulates HIV-1 infectivity, as demonstrated by gene targeting in human T cells. EMBO J. 20:1300–1309. 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaefer MH, Wanker EE, Andrade-Navarro MA. 2012. Evolution and function of CAG/polyglutamine repeats in protein-protein interaction networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:4273–4287. 10.1093/nar/gks011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhys NH, Soper AK, Dougan L. 2012. The hydrogen-bonding ability of the amino acid glutamine revealed by neutron diffraction experiments. J. Phys. Chem. B 116:13308–13319. 10.1021/jp307442f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alexander L, Veazey RS, Czajak S, DeMaria M, Rosenzweig M, Lackner AA, Desrosiers RC, Sasseville VG. 1999. Recombinant simian immunodeficiency virus expressing green fluorescent protein identifies infected cells in rhesus monkeys. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 15:11–21. 10.1089/088922299311664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rho HM, Poiesz B, Ruscetti FW, Gallo RC. 1981. Characterization of the reverse transcriptase from a new retrovirus (HTLV) produced by a human cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cell line. Virology 112:355–360. 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90642-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Owens CM, Yang PC, Gottlinger H, Sodroski J. 2003. Human and simian immunodeficiency virus capsid proteins are major viral determinants of early, postentry replication blocks in simian cells. J. Virol. 77:726–731. 10.1128/JVI.77.1.726-731.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kutner RH, Zhang XY, Reiser J. 2009. Production, concentration and titration of pseudotyped HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors. Nat. Protoc. 4:495–505. 10.1038/nprot.2009.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1605–1612. 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao G, Perilla JR, Yufenyuy EL, Meng X, Chen B, Ning J, Ahn J, Gronenborn AM, Schulten K, Aiken C, Zhang P. 2013. Mature HIV-1 capsid structure by cryo-electron microscopy and all-atom molecular dynamics. Nature 497:643–646. 10.1038/nature12162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldstone DC, Yap MW, Robertson LE, Haire LF, Taylor WR, Katzourakis A, Stoye JP, Taylor IA. 2010. Structural and functional analysis of prehistoric lentiviruses uncovers an ancient molecular interface. Cell Host Microbe 8:248–259. 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ganser-Pornillos BK, Yeager M, Sundquist WI. 2008. The structural biology of HIV assembly. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18:203–217. 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miyamoto T, Yokoyama M, Kono K, Shioda T, Sato H, Nakayama EE. 2011. A single amino acid of human immunodeficiency virus type 2 capsid protein affects conformation of two external loops and viral sensitivity to TRIM5alpha. PLoS One 6:e22779. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fadel HJ, Poeschla E. 2011. Retroviral restriction and dependency factors in primates and carnivores. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 143:179–189. 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Virgen CA, Kratovac Z, Bieniasz PD, Hatziioannou T. 2008. Independent genesis of chimeric TRIM5-cyclophilin proteins in two primate species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:3563–3568. 10.1073/pnas.0709258105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liao CH, Kuang YQ, Liu HL, Zheng YT, Su B. 2007. A novel fusion gene, TRIM5-cyclophilin A in the pig-tailed macaque determines its susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. AIDS 21(Suppl 8):S19–S26. 10.1097/01.aids.0000304692.09143.1b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brennan G, Kozyrev Y, Hu SL. 2008. TRIMCyp expression in Old World primates Macaca nemestrina and Macaca fascicularis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:3569–3574. 10.1073/pnas.0709511105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu F, Kirmaier A, Goeken R, Ourmanov I, Hall L, Morgan JS, Matsuda K, Buckler-White A, Tomioka K, Plishka R, Whitted S, Johnson W, Hirsch VM. 2013. TRIM5 alpha drives SIVsmm evolution in rhesus macaques. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003577. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Calef C, Mokili J, O'Connor DH, Watkins DI, Korber B. 2001. Numbering positions in SIV relative to SIVmm239. HIV sequence compendium. Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM: http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/HIV/REVIEWS/SIV_NUMBERING2001/SivNumbering.html [Google Scholar]