Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE:

Susceptibility to encapsulated bacteria is well known in sickle cell disease (SCD). Hydroxyurea use is common in adults and children with SCD, but little is known about hydroxyurea’s effects on immune function in SCD. Because hydroxyurea inhibits ribonucleotide reductase, causing cell cycle arrest at the G1–S interface, we postulated that hydroxyurea might delay transition from naive to memory T cells, with inhibition of immunologic maturation and vaccine responses.

METHODS:

T-cell subsets, naive and memory T cells, and antibody responses to pneumococcal and measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines were measured among participants in a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of hydroxyurea in infants and young children with SCD (BABY HUG).

RESULTS:

Compared with placebo, hydroxyurea treatment resulted in significantly lower total lymphocyte, CD4, and memory T-cell counts; however, these numbers were still within the range of historical healthy controls. Antibody responses to pneumococcal vaccination were not affected, but a delay in achieving protective measles antibody levels occurred in the hydroxyurea group. Antibody levels to measles, mumps, and rubella showed no differences between groups at exit, indicating that effective immunization can be achieved despite hydroxyurea use.

CONCLUSIONS:

Hydroxyurea does not appear to have significant deleterious effects on the immune function of infants and children with SCD. Additional assessments of lymphocyte parameters of hydroxyurea-treated children may be warranted. No changes in current immunization schedules are recommended; however, for endemic disease or epidemics, adherence to accelerated immunization schedules for the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine should be reinforced.

Keywords: sickle cell disease, hydroxyurea, immunology, vaccines

What’s Known on This Subject:

Hydroxyurea is a treatment option for young patients with sickle cell disease (SCD). Establishing the safety of hydroxyurea is of paramount importance. The effect of hydroxyurea on immune function and immunizations in SCD has not been studied previously.

What This Study Adds:

Children with SCD receiving hydroxyurea have lower lymphocyte, CD4, and memory T-cell counts compared with those receiving placebo, but still in the range for healthy children. Despite slower response to measles vaccine, measles, mumps, and rubella and pneumococcal vaccines are effective.

The use of hydroxyurea to treat sickle cell disease (SCD) has become common in children. A recent National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute consensus statement concluded that there is strong evidence to support the use of hydroxyurea in adults but that the evidence for efficacy of hydroxyurea for children is not as strong; additional studies were recommended.1 The recently completed BABY HUG study explored the safety and efficacy of hydroxyurea in infants and toddlers with HbSS and HbS-β0 thalassemia, with safety being of paramount importance.2

Susceptibility to infection with encapsulated bacteria, particularly Streptococcus pneumoniae, is well known in SCD, because of defects in splenic function and serum opsonic activity.3 This susceptibility is most marked early in life, at the age of patients enrolled in the BABY HUG trial (9–18 months at study entry). Older children and adults develop protective antibodies against pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides that compensate in part for the immunologic defects in SCD. Immunizations against encapsulated bacteria and penicillin prophylaxis are mainstays in the prevention of serious infection in SCD.4–6

Despite this need for immunizations and the known susceptibility of patients with SCD to infections, remarkably little evidence exists about the effects of hydroxyurea on immune function in people with SCD. Lowering of white blood cell and granulocyte counts by hydroxyurea in adults7,8 and children2,9,10 with SCD has been documented, but no studies have reported specific effects on lymphocyte number or immunologic function. Hydroxyurea reversibly inhibits ribonucleotide reductase, leading to cell cycle arrest at the G1–S interface.11 Because infants and young children are immunologically immature and their primary lymphoid organs must produce large numbers of naive T and B lymphocytes, the effects of hydroxyurea could be greater in this age group than in older children and adults. We hypothesized that hydroxyurea might delay the normal progression from naive to memory T cells, causing a delay in immunologic maturation, with deleterious effects on antibody responses to vaccines.

Chemotherapeutic agents can reduce the initial efficacy of immunizations and pose risks for immunization with live, attenuated viral or bacterial vaccines.12–14 In addition, waning vaccine-related antibody titers have been documented after treatment of childhood leukemia,15,16 although this is probably also influenced by the underlying disease and intensity of chemotherapy. Recommendations for patients and physicians regarding hydroxyurea include cautions about vaccine efficacy and safety. The American Cancer Society and other sources of consumer information include SCD as an indication for hydroxyurea but provide warnings about receiving immunizations during or after treatment without physician advice and about the need to avoid people who have recently received certain live vaccines.17 Despite these concerns, there are no specific recommendations for immunization of children receiving hydroxyurea for SCD.

The BABY HUG trial provided a unique opportunity to explore these issues.

Methods

Patients and Timing of Samples

This study involved participants in the previously published multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of hydroxyurea in infants and young children with sickle cell anemia, which was conducted from 2003 to 2009.2 Participants were screened between 7 and 18 months of age and followed for a period of 2 years. Blood was collected for T-cell subsets at entry, age 24 months, and exit. Blood for pneumococcal antibody levels was collected at entry and before and 2 to 8 weeks after administration of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV-23, given at ∼24 months of age) and at study exit. Blood for measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) antibodies was collected 2 to 10 weeks after the MMR vaccine (at ∼12 months, the usual age for MMR in the United States), at age 24 months, and at study exit. Acute response to MMR vaccine was evaluated for participants who were enrolled before MMR vaccination and had a blood sample within the required time frame after MMR vaccination. This study was approved by institutional review boards at each study site and the coordinating center (Clinical Trials and Surveys Corp) as part of the BABY HUG study.2

Samples Available for Analysis

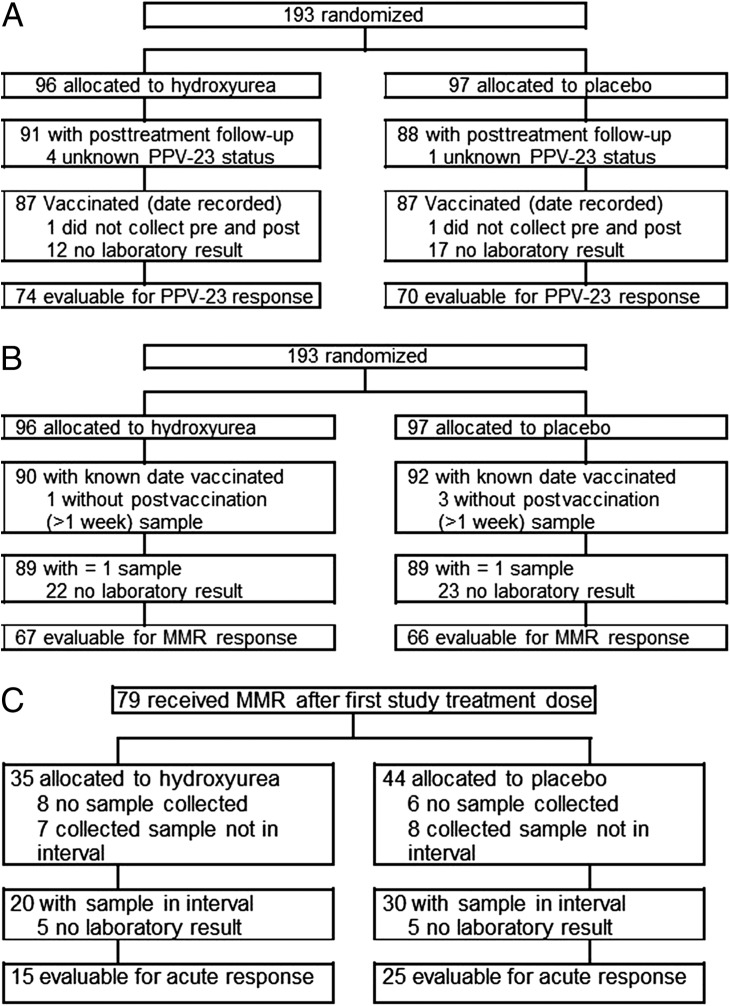

All BABY HUG participants who were randomly assigned to study treatment underwent immunology studies. Different numbers of samples were available for the various tests of immune function (Fig 1 and Table 1). A participant’s lymphocyte analyses were included if there was ≥1 sample available after study treatment. These criteria were achieved for 91 participants in the hydroxyurea group and 88 in the placebo group, for a total of 179 (92.7%) of 193 randomly assigned participants in the BABY HUG trial. For analyses of antibody responses to PPV-23, we included participants with a known date of that immunization for whom a prestudy treatment sample or a preimmunization sample at 24 months and ≥1 postimmunization (age 26 months, or end of study) sample were assayed (74 in the hydroxyurea group and 70 in the placebo group, for a total of 144 [74.6%] of 193 randomly assigned participants, Fig 1A and Table 1). For assessment of antibody responses to the MMR vaccine, we included participants who had a known date of immunization and a postimmunization blood specimen (67 in the hydroxyurea group and 66 in the placebo group, for a total of 133 [68.9%] of the 193 randomly assigned participants, Fig 1B and Table 1). To assess the effect of study treatment on the acute response to the MMR vaccine, we included only participants for whom a blood sample was collected between 2 and 10 weeks after immunization (Fig 1C and Table 1). Results are presented separately for patients immunized before and after beginning their randomly assigned treatment. This subset included 15 of 35 (43%) participants in the hydroxyurea group and 25 of 44 (57%) participants in the placebo group (Fig 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Samples available for study. A, Patients evaluable for PPV-23 response (vaccinated with PPV-23 with ≥1 preimmunization and 1 postimmunization sample for measurement of pneumococcal antibody levels). B, Vaccinated participants with ≥1 blood sample after immunization for measurement of MMR antibody levels. C, Patients who received randomized treatment before MMR vaccination and evaluable for acute MMR response (with ≥1 blood sample for measurement of MMR antibody levels within the 2- to 10-week acute response window).

TABLE 1.

Summary of Groups Used for Analyses

| FACS | Pneumococcal | MMR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HU = 91 | Placebo = 88 | HU = 74 | Placebo = 70 | HU = 67 | Placebo = 66 | |

| Boys | 45% | 42% | 45% | 47% | 43% | 47% |

| Study visit | ||||||

| Pretreatment (N) | 91 | 88 | 73 | 69 | — | — |

| Age, mo (SD) | 12.5 (2.6) | 12.8 (3.1) | 12.9 (2.6) | 13.1 (2.7) | — | — |

| 2–10 wk after MMR (N) | — | — | — | — | 40 | 38 |

| Age, mo (SD) | — | — | — | — | 14.7 (3.1) | 15.0 (1.9) |

| Days after vaccination [min, max] | — | — | — | — | 36 [11, 73] | 37 [12, 75] |

| 2–10 wk after MMR on treatmenta (N) | — | — | — | — | 15 | 25 |

| Age, mo (SD) | — | — | — | — | 15.7 (3.1) | 15.3 (2.0) |

| Days after vaccination [min, max] | — | — | — | — | 33 [13, 61] | 38 [14, 75] |

| Age 24 mo (N) | 74 | 72 | 65 | 59 | 62 | 60 |

| Age, mo (SD) | 24.1 (1.1) | 24.4 (1.5) | 24.0 (1.1) | 24.1 (1.1) | 24.0 (1.1) | 24.2 (1.3) |

| Age 26 mo (PPV-23) (N) | — | — | 63 | 56 | — | — |

| Age, mo (SD) | — | — | 26.4 (2.2) | 26.3 (2.6) | — | — |

| End of study (N) | 86 | 86 | 66 | 62 | 59 | 58 |

| Age, mo (SD) | 37.8 (2.8) | 37.5 (2.9) | 37.9 (2.9) | 37.9 (3.0) | 37.8 (2.7) | 37.4 (2.8) |

FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; HU, hydroxyurea.

Includes only participants vaccinated after receiving first dose of study treatment.

— indicates not applicable to study design.

T-Cell Subsets

Expression of CD45RA (naive) and CD45RO (memory) T-cell subsets was determined by 4-color flow cytometry using the combination CD45RA-FITC/CD45RO-PE/CD4-PerCPCy5.5/CD8-APC (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA). T-cell subsets were determined by standard methods, using combinations of CD3/4/8 and CD45.

Antibodies to Pneumococcal Polysaccharides

Type-specific antipneumococcal immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody levels were measured by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, modified from the method of Koskela.18 Types 26 (6B) and 51 (7F) pneumococcal polysaccharides and C-polysaccharide were from the American Type Culture Collection. All sera were premixed with pneumococcal C-polysaccharide to minimize nonspecific binding. For each serotype, 4 2.5-fold dilutions of serum were prepared; samples were assayed in duplicate. Dilutions of the Food and Drug Administration pneumococcal reference serum lot 89-SF19 were tested in parallel. We compared patient and reference sera by using a 4-parameter logistic-log function.20 Levels of protection of ≥0.35 and ≥1.0 μg/mL were considered separately.

Antibodies to MMR

IgG antibodies to each virus were measured with commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (Bio-Quant, San Diego, CA). Antibody levels were calculated in comparison with a standard reference serum control curve supplied with each kit, using a 4-parameter logistic-log function.20 Antibody levels of ≥1.1 index were considered protective.

Statistical Analysis

T-cell subset percentages and log-transformed counts were compared with the 2-sample Student’s t test, evaluated at α = .05 significance level for the 2-sided test. Mean percentages and geometric mean counts are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

T-Cell Subsets in Children With Sickle Cell Disease

| Entry | Age 24 mo | Exit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HU | Placebo | P | HU | Placebo | P | HU | Placebo | P | |

| Number of participants | 91 | 88 | 74 | 72 | 86 | 86 | |||

| Lymphocytes/mm3a | 6776 (0.67) | 7106 (0.67) | .494 | 5218 (0.66) | 6550 (0.68) | .003 | 4386 (0.67) | 5219 (0.67) | .012 |

| CD3 %b | 53 (11) | 54 (12) | .936 | 56 (10) | 51 (11) | .016 | 55 (10) | 52 (11) | .064 |

| CD3 #a | 3527 (0.67) | 3739 (0.66) | .394 | 2859 (0.65) | 3288 (0.66) | .040 | 2384 (0.67) | 2670 (0.67) | .096 |

| CD4 %b | 36 (10) | 36 (10) | .856 | 34 (8) | 33 (9) | .185 | 32 (8) | 32 (9) | .653 |

| CD4 #a | 2357 (0.67) | 2572 (0.67) | .199 | 1770 (0.65) | 2068 (0.66) | .022 | 1365 (0.67) | 1584 (0.67) | .031 |

| Naive CD4+CD45RA+ %b | 77 (9) | 78 (8) | .482 | 71 (10) | 70 (10) | .455 | 68 (11) | 66 (11) | .150 |

| Naive CD4+CD45RA+ #a | 1795 (0.69) | 1986 (0.69) | .195 | 1249 (0.68) | 1437 (0.69) | .084 | 916 (0.71) | 1022 (0.71) | .199 |

| Memory CD4+CD45RO+ %b | 17 (8) | 16 (7) | .595 | 22 (10) | 23 (8) | .513 | 26 (10) | 27 (10) | .212 |

| Memory CD4+CD45RO+ #a | 347 (0.73) | 374 (0.75) | .422 | 359 (0.66) | 445 (0.67) | .003 | 324 (0.67) | 409 (0.66) | <.001 |

| CD8 %b | 15 (6) | 15 (7) | .950 | 18 (7) | 16 (7) | .112 | 19 (7) | 17 (6) | .070 |

| CD8 #a | 978 (0.70) | 1053 (0.73) | .389 | 882 (0.70) | 975 (0.70) | .267 | 782 (0.71) | 847 (0.70) | .334 |

| Naive CD8+CD45RA+ %b | 85 (9) | 85 (10) | .922 | 84 (10) | 82 (12) | .309 | 85 (7) | 82 (9) | .026 |

| Naive CD8+CD45RA+ #a | 824 (0.70) | 884 (0.73) | .406 | 735 (0.69) | 792 (0.68) | .370 | 661 (0.71) | 691 (0.70) | .590 |

| Memory CD8+CD45RO+ %b | 9.00 (8) | 9.40 (8) | .754 | 9.50 (9) | 11 (8) | .417 | 8.80 (6) | 11 (6) | .031 |

| Memory CD8+CD45RO+ #a | 66 (0.99) | 76 (0.94) | .336 | 63 (0.99) | 82 (0.98) | .110 | 57 (0.86) | 78 (0.80) | .008 |

HU, hydroxyurea.

Counts are summarized by geometric means (coefficient of variation) and t test to compare log-transformed counts.

Percentages are summarized by treatment means (SD) and t test.

We compared proportions of patients with protective antipneumococcal IgG antibody levels by using Fisher’s exact test, evaluated at α = .05 significance level for the 2-sided test. Median antibody levels are also reported. Separate analyses of antibodies to MMR were performed for participants who received the MMR vaccine before or after the first dose of randomized treatment. We compared proportions of patients with protective antibody levels by using Fisher’s exact test, evaluated at α = .05 significance level for the 2-sided test. Analysis of covariance with effects of treatment, log-transformed days after treatment, and the interaction effect was used to evaluate log-transformed antibody levels evaluated 2 to 10 weeks after MMR immunization.

Results

T-Cell Subsets

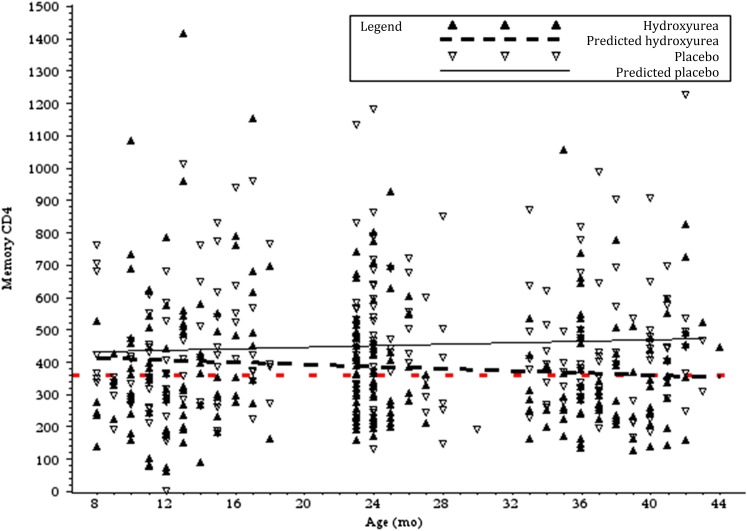

At study entry, there were no significant differences between the hydroxyurea and placebo groups in absolute lymphocyte count or the percentages or absolute numbers of any of the T-lymphocyte subsets (Table 2). At age 24 months, both groups showed an expected age-related decline in absolute lymphocyte count, but there were statistically significant differences in the absolute lymphocyte number (P = .003), absolute T-cell (CD3) count (P = .040), absolute CD4 count (P = .022), and memory CD4+CD45RO+ count (Fig 2; P = .003) between the 2 groups. Similar findings were seen at study exit, with absolute lymphocyte number (P = .012), absolute CD4 count (P = .031), and memory CD4+CD45RO+ count (P < .001) significantly lower in the hydroxyurea group. In addition, there were statistically significant differences in naive and memory CD8 cells, with a higher percentage of naive cells (P = .026), lower percentage of memory cells (P = .031), and lower absolute number of memory cells (P = .008) in the hydroxyurea group. However, none of the lymphocyte counts or subsets were below normal values for similarly aged normal children.21

FIGURE 2.

Effects of hydroxyurea on the absolute number of memory CD4 T cells. Reference line (red dashes) indicates baseline geometric mean (360 cells/mm3, slope = 0). Linear regression lines show slopes (cells/mm3 per month): hydroxyurea, −1.6 and placebo, +1.1.

Antibody to Pneumococcal Polysaccharide

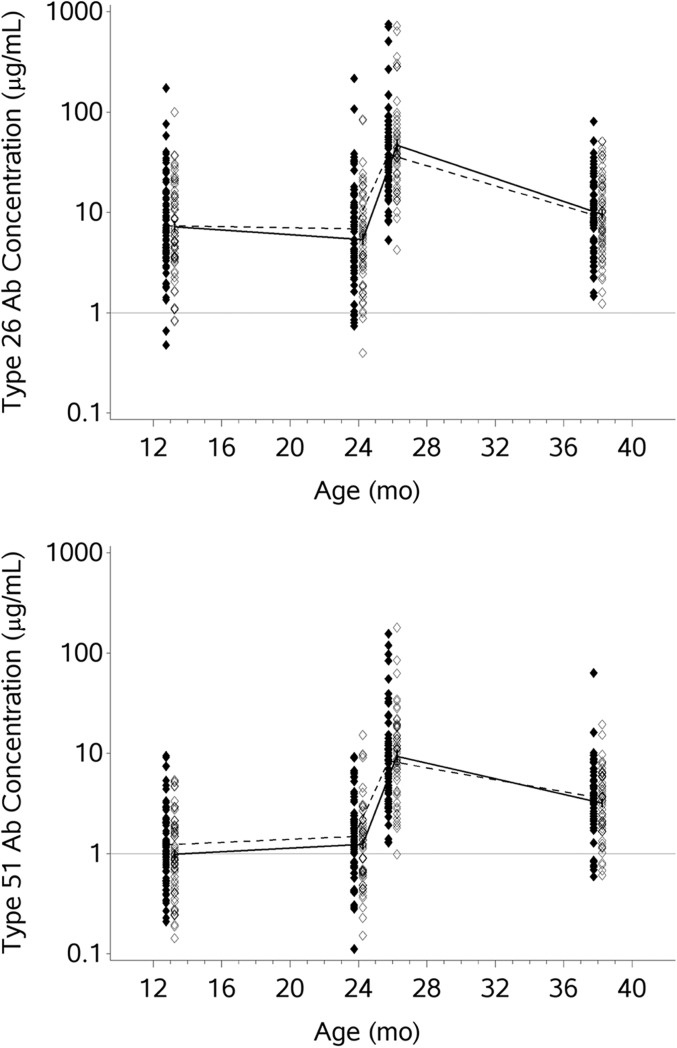

We chose to test for IgG antibodies to type 26 because it is included in the T-dependent 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate (PCV-7) vaccine that was administered to all participants before entry and randomization and because there is a booster immunization with the T-independent PPV-23 vaccine administered to children at age 24 months, many months after randomization. We chose to test for antibodies to type 51 because it is a T-independent (polysaccharide) antigen in PPV-23, to which children were exposed only after randomization. (This study occurred before the licensure of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [PCV-13] in 2010; PCV-13, but not PCV-7 [Prevnar-7], includes the pneumococcal serotype 51 polysaccharide/protein conjugate.) IgG antibody levels were measured at entry (after the standard series of 3 immunizations with PCV-7 at ages 2, 4, and 6 months). By age 23 months, before PPV-23 immunization, 80% of the hydroxyurea and 88% of the placebo patients had received at least 3 PCV-7 immunizations; 96% and 99%, respectively, had received ≥2 PCV-7 vaccinations. There was no statistical difference between the hydroxyurea and placebo groups in the time to completion of the PCV-7 series. PCV-7 vaccine includes pneumococcal polysaccharide type 26 but not 51. At entry, the geometric mean IgG antibody level to type 26 was 7.3 μg/mL (Table 3). For type 51, the geometric mean level of IgG antibody was 1.1 μg/mL. The proportions of participants with a protective antibody level (when defined as either ≥0.35 μg/mL or ≥1.0 μg/mL) in the hydroxyurea and placebo groups were not significantly different at entry or at any of the other time points (Fig 3, Table 3). Differences were not seen in the persistence of antibody to the T-dependent serotype 26 polysaccharide/protein conjugate antigen, to which participants were immunized before enrollment in this trial; the acute booster response to the T-independent serotype 26 polysaccharide in PPV-23; or the T-independent serotype 51 polysaccharide, to which patients were exposed for the first time through PPV-23 at 24 months of age. Furthermore, the pneumococcal antibody levels persisted until study exit, at a mean age of 37.9 months. There was no statistical relationship between the CD3, CD4, or CD4+CD45RO+ numbers and the pneumococcal antibody levels in either the hydroxyurea or placebo group. There were no statistically significant differences in pneumococcal antibody responses between children who had received all of their PCV-7 immunizations on time and those whose immunizations were late, but this conclusion is limited by the small number of subjects who had delayed immunizations.

TABLE 3.

Geometric Mean and Protective Pneumococcal IgG Antibody Levels

| Entry | 24 mo (Before PPV-23) | 26 mo (After PPV-23) | Exit | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HU (n = 73) | Placebo (n = 69) | Pa | HU (n = 65) | Placebo (n = 58) | Pa | HU (n = 63) | Placebo (n = 56) | Pa | HU (n = 66) | Placebo (n = 62) | Pa | |

| Serotype 26 (6B) | ||||||||||||

| Geometric mean antibody (μg/mL) | 7.4 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 5.4 | 37.9 | 46.6 | 9.4 | 9.6 | ||||

| 95% CI | [5.7–9.5] | [5.7–9.2] | [5.1–9.3] | [4.2–7.0] | [29.6–48.6] | [35.3–61.4] | [7.6–11.7] | [7.6–12.0] | ||||

| % Protective (≥1.0 μg/mL) | 97.3 | 97.1 | >.999 | 92.3 | 94.8 | .721 | 100 | 100 | — | 100 | 100 | — |

| 95% CI | [90.5–99.7] | [89.9–99.7] | [83.0–97.5] | [85.6–98.9] | [94.3–100.0] | [93.6–100.0] | [94.6–100.0] | [94.2–100.0] | ||||

| % Protective (≥0.35 μg/mL) | 100.0 | 100.0 | — | 100.0 | 98.3 | .471 | 100 | 100 | — | 100 | 100 | — |

| 95% CI | [95.1–100.0] | [94.8–100.0] | [94.5–100.0] | [90.8–100.0] | [94.3–100.0] | [93.6–100.0] | [94.6–100.0] | [94.2–100.0] | ||||

| Serotype 51 (7F) | ||||||||||||

| Geometric mean antibody (μg/mL) | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 8.4 | 9.4 | 3.7 | 3.2 | ||||

| 95% CI | [1.0–1.5] | [ 0.8–1.2] | [1.2–1.9] | [0.9–1.5] | [6.4–11.0] | [7.2–12.2] | [3.0–4.5] | [2.6–3.9] | ||||

| % Protective (≥1.0 μg/mL) | 60.3 | 47.8 | .177 | 72.3 | 58.6 | .129 | 100 | 98.2 | .47 | 90.9 | 93.5 | .745 |

| 95% CI | [48.1–71.6] | [35.7–60.2] | [59.8–82.7] | [44.9–71.4] | [94.3–100.0] | [90.5–100.0] | [81.3–96.6] | [84.3–98.2] | ||||

| % Protective (≥0.35 μg/mL) | 91.8 | 85.5 | .292 | 93.8 | 94.8 | >.999 | 100 | 100 | — | 100 | 100 | — |

| 95% CI | [83.0–96.9] | [75.0–92.8] | [85.0–98.3] | [85.6–98.9] | [94.3–100.0] | [93.6–100.0] | [94.6–100.0] | [94.2–100.0] | ||||

CI, confidence interval; HU, hydroxyurea.

No P value calculated (—) when hydroxyurea and placebo % protected = 100%.

Fisher’s exact test.

FIGURE 3.

Semilogarithmic plot of IgG antibody concentrations to pneumococcal polysaccharide serotypes 26 (6B) and 51 (7F). Individual patients are represented by scatterplot symbols corresponding to their IgG antibody concentration at pretreatment, age 24 months, age 26 months, and end of study. Plot symbols of patients randomly assigned to hydroxyurea are offset left solid diamonds, with geometric means connected by dashed line. Plot symbols of patients randomly assigned to placebo are offset right open diamonds, with geometric means connected by unbroken line.

Antibody to MMR

When the MMR vaccine was administered to participants before randomized treatment, there were no differences between the hydroxyurea and placebo groups in the percentage of participants who were immune to MMR (Table 4). When MMR vaccine was administered to participants after randomized treatment, the percentage of participants immune to measles 2 to 10 weeks after immunization was lower in the hydroxyurea group than in the placebo group (hydroxyurea 10/14 [71.4%] vs placebo 24/24 [100%]; P = .014). There were similar findings in the protective responses to mumps (hydroxyurea 11/14 [78.6%] vs placebo 22/24 [91.7%]) and rubella (hydroxyurea 10/15 [66.7%] vs placebo 23/25 [92%]), although the results did not reach statistical significance. By age 24 months, the differences between treatment groups in percentage of participants immune to MMR were not significant (87%–100% for individual vaccines and 81%–96% for immunization to all 3).

TABLE 4.

MMR Protective Antibody Levels

| Antibody | MMR Before Randomized Treatment? | Visit | Number (%) of Participants With Protective Antibody Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HU | Placebo | P (Fisher’s exact test) | |||

| Measles | Yes | 2–10 wk after MMR | 23/24 (95.8) | 10/11 (90.9) | .536 |

| Age 24 mo | 40/40 (100.0) | 31/31 (100.0) | — | ||

| End of study | 36/36 (100.0) | 28/29 (96.6) | .446 | ||

| No | 2–10 wk after MMR | 10/14 (71.4) | 24/24 (100.0) | .014 | |

| Age 24 mo | 18/19 (94.7) | 28/28 (100.0) | .404 | ||

| End of study | 21/21 (100.0) | 27/27 (100.0) | — | ||

| Mumps | Yes | 2–10 wk after MMR | 23/24 (95.8) | 9/11 (81.8) | .227 |

| Age 24 mo | 40/41 (97.6) | 27/31 (87.1) | .158 | ||

| End of study | 37/38 (97.4) | 26/29 (89.7) | .308 | ||

| No | 2–10 wk after MMR | 11/14 (78.6) | 22/24 (91.7) | .337 | |

| Age 24 mo | 19/21 (90.5) | 28/29 (96.6) | .565 | ||

| End of study | 19/21 (90.5) | 28/30 (96.7) | .561 | ||

| Rubella | Yes | 2–10 wk after MMR | 24/25 (96.0) | 10/13 (76.9) | .107 |

| Age 24 mo | 36/36 (100.0) | 24/24 (100.0) | — | ||

| End of study | 33/33 (100.0) | 22/22 (100.0) | — | ||

| No | 2–10 wk after MMR | 10/15 (66.7) | 23/25 (92.0) | .081 | |

| Age 24 mo | 15/16 (93.8) | 26/26 (100.0) | .381 | ||

| End of study | 17/18 (94.4) | 26/26 (100.0) | .409 | ||

HU, hydroxyurea.

No P value calculated (—) when hydroxyurea and placebo % protected = 100%.

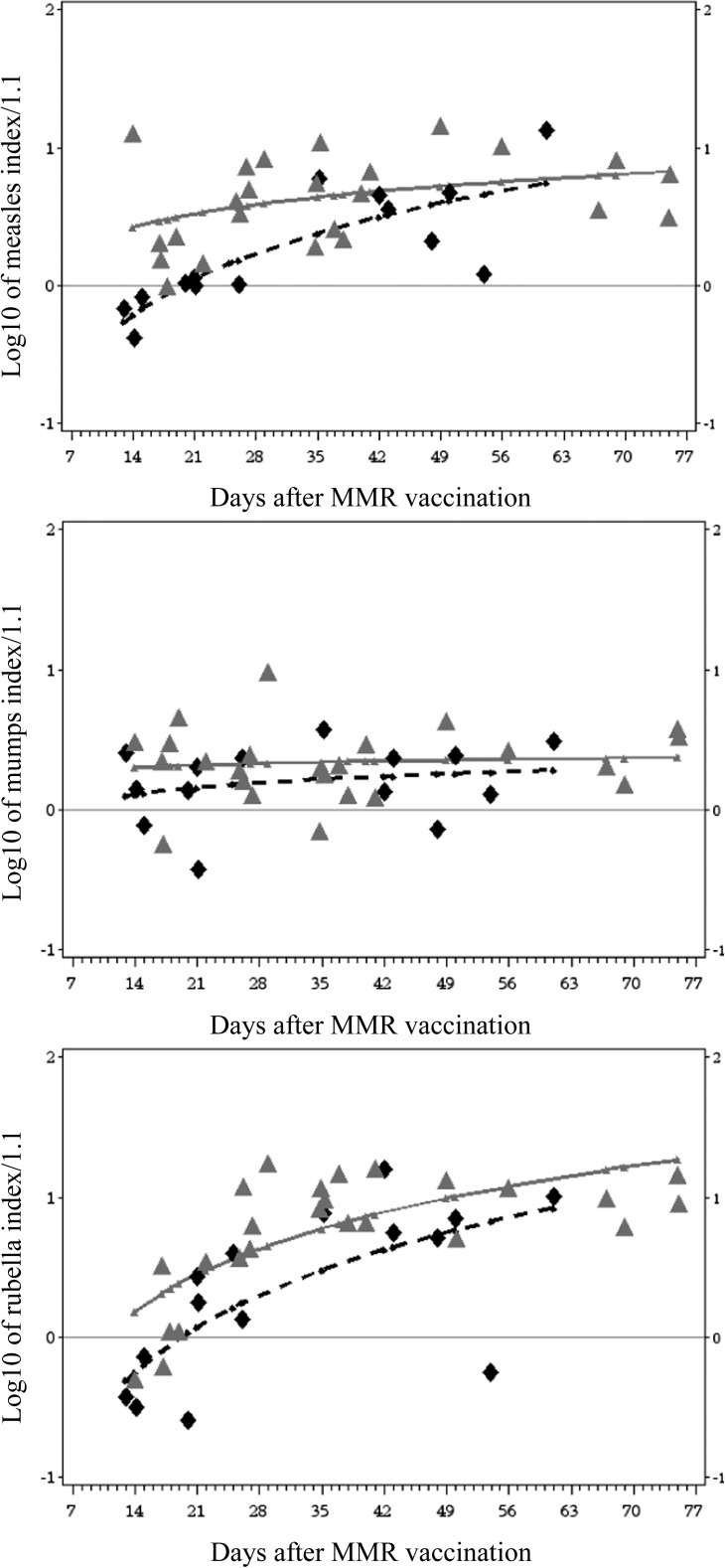

We found additional support for a delayed response to measles vaccine by analyzing log-transformed antibody levels measured 2 to 10 weeks after vaccination versus log of time, revealing a significant difference in percentage immune (P = .032) and mean antibody level (P = .010, Fig 4). The log–log response model for mumps showed no significant treatment difference, and the log–log response model for rubella showed a significant difference in mean antibody level (P = .008) but not in percentage protected. The differences in antibody responses after immunization could not be explained by mean age of participants at immunization or by baseline lymphocyte, CD4, or memory CD4 numbers. The means and distributions of ages of patients in the hydroxyurea and placebo groups for the 2- to 10-week postimmunization group were not significantly different, nor was the number of days after immunization, indicating that the timing of sampling was not responsible for the differences in protective or mean antibody levels.

FIGURE 4.

Log acute antibody levels to MMR. Scatterplot symbols represent log10 (acute response index/1.1) of patients who started randomized treatment before MMR vaccination. Curvilinear lines represent regression of log10 antibody level versus log10 days after MMR vaccination in model that included randomized treatment and treatment by time effects. Horizontal line represents the protective level of antibody. Plot symbols of patients randomly assigned to hydroxyurea are black diamonds with dashed line. Placebo are gray triangles with unbroken lines. Model treatment mean antibody index and rate difference (difference in slope) results were measles, mean P = .010, rate P = .032; mumps, mean P = .516, rate P = .663; rubella, mean P = .008, rate P = .497.

As shown in Fig 1 A and B, there were 29 (12 + 17) participants with no pneumococcal antibody results available and 45 (22 + 23) participants with no MMR antibody results. Some available samples were not analyzed because the participant had no sample collected in the first postimmunization interval. Twenty-five participants enrolled later in the study had no pneumococcal or MMR antibody result because their samples were not available when the laboratory testing was performed. These participants began the study drug 42 to 46 months after the first participant and had a mean age of 12.6 months, compared with 14.0 months for participants enrolled earlier (P = .014). Those who did not have pneumococcal or MMR antibody results were comparable in age at MMR vaccination, baseline lymphocyte, CD4, and memory CD4 counts, suggesting that they did not differ significantly from the population tested, except for age.

Discussion

Because BABY HUG was a placebo-controlled trial in infants who started treatment as early as age 9 months of age, it presented a unique opportunity to examine the effects of hydroxyurea on the developing immune system. We hypothesized that hydroxyurea, by virtue of its antiproliferative effects on lymphocytes, might delay the development of the immunologic repertoire during a crucial period of maturation in the young child, leading to impaired responses to immunization and reduced numbers of memory T cells.

We found that hydroxyurea treatment was associated with statistically significant reductions in absolute lymphocyte, CD4 T-cell, and memory CD4 and CD8 T-cell counts compared with the placebo group; however, the percentages and absolute numbers of each of those lymphocyte subsets remained as high as or higher than in healthy controls of a similar age.21 The delay in transition from naive to memory T cells seen in patients treated with hydroxyurea is consistent with the antiproliferative effects of hydroxyurea, which are caused by inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase and fit the a priori hypothesis of the study. The fact that some effect was observed on vaccinations that are more dependent on T-cell function (MMR) than T-cell independent vaccination (PPV-23) suggests that the effects of hydroxyurea may be more important for T-cell maturation than B-cell maturation. The clinical importance of these findings is not clear. Although the differences are numerically small, the reductions in total lymphocytes and total CD4 cells in the hydroxyurea-treated children suggest that additional studies are warranted in this group and in others who begin hydroxyurea therapy early in life and continue the drug beyond 3 years of age. However, because children with SCD generally have higher lymphocyte counts than controls,22 it is not clear that the observed reduction in the numbers of total and memory CD4 cells and CD8 memory cells will lead to an increased risk of infection or other deleterious immunologic consequences. In fact, reductions in the number of those cells may indicate a benefit through a decreased inflammatory response. If so, the number of CD4 T cells, the number of CD4 and CD8 memory cells, and the ratio of CD4 memory to naive cells could be biomarkers for a beneficial hydroxyurea effect. The data from the placebo group provide additional detailed normative information about T-cell subset development in African American infants and young children with SCD.

There is controversy about the level of pneumococcal IgG antibody that prevents invasive disease (0.35 μg/mL)23 and the level measured acutely after immunization that represents a normal antibody response and predicts long-term protection (1.0–1.3 μg/mL).24 Therefore, we chose to compare the IgG antibody levels and the percentage of subjects reaching levels of 0.35 and 1.0 μg IgG antibody per milliliter between the hydroxyurea and placebo groups. Immunization with the T-independent pneumococcal vaccine PPV-23 was not affected by hydroxyurea therapy, suggesting there should be no increased risk for pneumococcal sepsis in infants and children with SCD who are treated with hydroxyurea. Both absolute antibody levels and the proportion of children with levels of pneumococcal antibody likely to be protective against infection were unaffected by hydroxyurea. This was true for a polysaccharide antigen in PCV-7, to which the participants had been previously vaccinated (serotype 6B), as well as one to which they had not been previously vaccinated (serotype 51).

Our results indicate that there was a delay in achieving protective levels of measles antibody among participants in the hydroxyurea group when compared with the placebo group. There were some similar trends for the response to mumps and rubella, but they did not reach statistical significance. The period of this delay can only be estimated, given the nature of the study design, but it appears to be in the range of 30 to 100 days. We were unable to determine whether the delay in antibody response was caused by an effect on B or T cells, because studies measuring T-cell response were not performed. Such experiments would be useful for future investigation. Importantly, antibody levels to all 3 viruses were similar between groups at exit, indicating that effective immunization with live viral vaccines can be achieved despite hydroxyurea therapy, with levels of antibody to the MMR vaccination at 100 days after immunization comparable to the percentage seen in healthy children.25 However, these results suggest that adherence to currently recommended accelerated immunization schedules for all children (a single dose of vaccine in unimmunized children >6 months old, with reimmunization at age 12 to 15 months and ≥28 days after the first dose of vaccine)26 may be especially important for children with SCD treated with hydroxyurea in the face of a local epidemic of measles, mumps, rubella, or other pathogens for which immunization can provide protection from infection or severe disease. In epidemic situations, it may also be reasonable to provide a hydroxyurea holiday around the time of vaccination. It should also be emphasized that the full immunologic effects of starting hydroxyurea treatment earlier in life or prolonging the treatment beyond the age of 3 years are not known. Additional evaluations of CD4 and memory T cells in particular appear to be warranted.

There are several limitations to this study. First, sample sizes, particularly for the measurements of MMR vaccine responses, were small. Because participants at study entry were 9 to 18 months old, many had already received the MMR vaccination before entry and were beyond the window when samples were to be obtained. In addition, only patients with paired samples before and after vaccination were included. Our analyses of patients who were and were not included in the study did not reveal any important demographic or treatment response differences; therefore, we do not believe that the conclusions were biased. Second, important long-term effects of hydroxyurea could be missed, given the short period of study treatment of each patient (2 years). Third, a fixed dose of 20 mg/kg per day was used in the BABY HUG study, whereas dosing up to 35 mg/kg per day or maximum tolerated dose is commonly used in practice. It is possible that greater effects on the immune system might be seen at these higher doses. Finally, the small number of patients treated with hydroxyurea in the BABY HUG study (96) makes it difficult to exclude low-frequency adverse events and effects.

Conclusions

Overall, we provide additional evidence for the safety of hydroxyurea in the treatment of infants and children with SCD. Our results showed no significant effects of hydroxyurea on recall or primary antibody response to pneumococcal polysaccharides, providing confirmation that the PCV-7 and PPV-23 vaccines given at 2 to 18 months and 24 months, respectively, are immunogenic in infants with SCD. Our findings and previous results from the BABY HUG clinical trial indicate that hydroxyurea therapy, as administered to children ages 9 to 42 months, did not cause a detectable, clinically important immunodeficiency, because there was no increase in any type of infection among participants in the hydroxyurea group.27 Delays in antibody response after vaccination to measles and possibly mumps and rubella were identified, but the ultimate development of immunity over time did not appear to be affected. The implications of these findings for vaccination in endemic areas or during epidemics must be considered, but no immediate safety concerns from hydroxyurea were identified for administration of live viruses or other vaccines according to currently recommended schedules for young children with SCD. Finally, statistically significant differences in CD4 T-cell and memory T-cell numbers between hydroxyurea-treated participants and controls warrant additional study to determine whether they are clinically significant. The data herein represent the best available evidence for health care providers with regard to immunizations of patients receiving hydroxyurea for SCD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the BABY HUG subjects and their families, and we are grateful for the contributions of all who participated in BABY HUG (http://www.c-tasc.com/cms/StudySites/babyhug.htm) and the support of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institutes of Health, with partial support of the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors also thank Catherine DeAngelis, MD, MPH, and John Modlin, MD, for critical review of this manuscript.

Glossary

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- MMR

measles, mumps, and rubella

- PCV-7

7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

- PCV-13

13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

- PPV-23

23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine

- SCD

sickle cell disease

Footnotes

Dr Lederman conceptualized and designed the study, performed laboratory experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; Dr Connolly analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript; Drs Kalpatthi, Ware, Wang, and Luchtman-Jones collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, and critically reviewed the manuscript; Drs Waclawiw and Goldsmith analyzed and interpreted data and critically reviewed the manuscript; Ms Swift developed and performed the antibody assays, analyzed the raw data, and reviewed the final manuscript; Dr Casella conceptualized and designed the study, collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

This trial has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00006400).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Dr Casella has received an honorarium and travel expenses in the past and currently receives salary support through Johns Hopkins for providing consultative advice to Mast Pharmaceuticals (previously Adventrx Pharmaceuticals) regarding a proposed clinical trial of an agent for treating vaso-occlusive crisis in sickle cell disease. He is an inventor and a named party on a patent and licensing agreement to ImmunArray for a panel of brain biomarkers for the detection of brain injury. He has filed a provisional patent for a potential treatment of sickle cell disease. Dr Ware is a consultant for Bayer and Novartis but declares no relevance for this study. The other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute/National Institutes of Health contracts N01-HB-07150 to N01-HB-07160. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no other potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Brawley OW, Cornelius LJ, Edwards LR, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement: hydroxyurea treatment for sickle cell disease. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(12):932–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang WC, Ware RE, Miller ST, et al. BABY HUG Investigators . Hydroxycarbamide in very young children with sickle-cell anaemia: a multicentre, randomised, controlled trial (BABY HUG). Lancet. 2011;377(9778):1663–1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett-Connor E. Bacterial infection and sickle cell anemia. An analysis of 250 infections in 166 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1971;50(2):97–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamkiewicz TV, Sarnaik S, Buchanan GR, et al. Invasive pneumococcal infections in children with sickle cell disease in the era of penicillin prophylaxis, antibiotic resistance, and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination. J Pediatr. 2003;143(4):438–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies EG, Riddington C, Lottenberg R, Dower N. Pneumococcal vaccines for sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004; (1):CD003885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adamkiewicz TV, Silk BJ, Howgate J, et al. Effectiveness of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children with sickle cell disease in the first decade of life. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):562–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charache S, Barton FB, Moore RD, et al. The Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia . Hydroxyurea and sickle cell anemia. Clinical utility of a myelosuppressive “switching” agent. Medicine (Baltimore). 1996;75(6):300–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinberg MH, Lu ZH, Barton FB, Terrin ML, Charache S, Dover GJ, Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea . Fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell anemia: determinants of response to hydroxyurea. Blood. 1997;89(3):1078–1088 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferster A, Vermylen C, Cornu G, et al. Hydroxyurea for treatment of severe sickle cell anemia: a pediatric clinical trial. Blood. 1996;88(6):1960–1964 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jayabose S, Tugal O, Sandoval C, et al. Clinical and hematologic effects of hydroxyurea in children with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr. 1996;129(4):559–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donehower RC. Hydroxyurea. In: Chabner, BA, Longo, DL, eds. Cancer Chemotherapy and Biotherapy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:253–260 [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Tilburg CM, Sanders EAM, Rovers MM, Wolfs TFW, Bierings MB. Loss of antibodies and response to (re-)vaccination in children after treatment for acute lymphocytic leukemia: a systematic review. Leukemia. 2006;20(10):1717–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ek T, Josefson M, Abrahamsson J. Multivariate analysis of the relation between immune dysfunction and treatment intensity in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(7):1078–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McFarland E. Immunizations for the immunocompromised child. Pediatr Ann. 1999;28(8):487–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilsson A, De Milito A, Engström P, et al. Current chemotherapy protocols for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia induce loss of humoral immunity to viral vaccination antigens. Pediatrics. 2002;109(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/109/6/e91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ek T, Mellander L, Hahn-Zoric M, Abrahamsson J. Intensive treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia reduces immune responses to diphtheria, tetanus, and Haemophilus influenzae type b. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26(11):727–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Cancer Society Web Site. Available at: www.cancer.org/treatment/treatmentsandsideeffects/guidetocancerdrugs/hydroxyurea

- 18.Koskela M. Serum antibodies to pneumococcal C polysaccharide in children: response to acute pneumococcal otitis media or to vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6(6):519–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quataert SA, Kirch CS, Wiedl LJ, et al. Assignment of weight-based antibody units to a human antipneumococcal standard reference serum, lot 89-S. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2(5):590–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plikaytis BD, Carlone GM, Turner SH, Gheesling LL, Holder PF. Program ELISA User’s Manual. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shearer WT, Rosenblatt HM, Gelman RS, et al. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group . Lymphocyte subsets in healthy children from birth through 18 years of age: the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group P1009 study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(5):973–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong WY, Powars DR, Operskalski EA, et al. The Transfusion Safety Study Group . Blood transfusions and immunophenotypic alterations of lymphocyte subsets in sickle cell anemia. Blood. 1995;85(8):2091–2097 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siber GR, Chang I, Baker S, et al. Estimating the protective concentration of anti-pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide antibodies. Vaccine. 2007;25(19):3816–3826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orange JS, Ballow M, Stiehm ER, et al. Use and interpretation of diagnostic vaccination in primary immunodeficiency: a working group report of the Basic and Clinical Immunology Interest Section of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(3 suppl):S1–S24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson CE, Kumar ML, Whitwell JK, et al. Antibody persistence after primary measles-mumps-rubella vaccine and response to a second dose given at four to six vs. eleven to thirteen years. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15(8):687–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Academy of Pediatrics In: Pickering L, ed. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012:489–499 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornburg CD, Files BA, Luo Z, et al. BABY HUG Investigators . Impact of hydroxyurea on clinical events in the BABY HUG trial. Blood. 2012;120(22):4304–4310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]