Abstract

Purpose

Partial nephrectomy may be underutilized in elderly patients due to concerns of higher complication rates compared with radical nephrectomy. We sought to determine if the association between age and perioperative outcomes differed between types of nephrectomy.

Materials and Methods

We identified patients who underwent radical or partial nephrectomy between January 2000 and October 2008. Using multivariable methods, we determined whether the relationship between age and risk of postoperative complications, estimated blood loss, or operative time differed by type of nephrectomy.

Results

Of 1,712 patients, 651 (38%) underwent radical nephrectomy and 1061 (62%) underwent partial nephrectomy. Patients treated with partial nephrectomy had higher complication rates than those treated with radical nephrectomy (20% vs 14%). In a multivariable model, age was significantly associated with a small increased risk of having a complication (OR for 10-year age increase: 1.17; 95% CI, 1.04-1.32; p = 0.009). When including an interaction term between age and procedure type, the interaction term was not significant (p = 0.09), indicating there was no evidence the risk of complications associated with a partial versus a radical nephrectomy increased with advancing age. We found no evidence that age was significantly associated with estimated blood loss or operative time.

Conclusions

We found no evidence that elderly patients experience a proportionally higher rate of complications, longer operative times, or higher estimated blood loss from partial nephrectomy than do younger patients. Given the advantages of renal function preservation, we should expand the use of nephron-sparing treatment for renal tumors in elderly patients.

Keywords: Carcinoma, renal cell; Kidney neoplasms; Nephrectomy; Urologic surgical procedures; Postoperative complications

INTRODUCTION

PN is underutilized for the surgical treatment of renal tumors, especially among elderly patients.1-3 Reasons for this underutilization are not fully understood, but many urologic surgeons view increasing patient age as a relative contraindication to PN. There is an “old urologic wives’ tale”, that older, sicker renal mass patients should undergo an RN instead of a PN, ensuring patients have a faster operation and lower complication risk. This historic viewpoint assumes the difference in operative times and complication rates is clinically significant and fails to consider the deleterious effects of iatrogenic renal loss.

What then are the barriers to the use of PN? For appropriately selected patients, oncologic control should not be a concern. Several studies have demonstrated equal 5-year oncologic outcomes between RN and PN for tumors less than 7 cm.4-8 A more formidable barrier is the fear of increased complications from PN, which is often viewed as a more technically challenging procedure. The literature is somewhat conflicting on this matter: Some studies report similar complication rates between PN and RN,7, 9-10 while others suggest slightly higher rates with PN.11-12 We believe this fear of complications is a major factor limiting the expansion of PN, especially in elderly patients.

We sought to test the hypothesis that older patients are better served by RN in terms of complications, blood loss, and operative time. Several prior studies have directly compared complication rates between patients who had PN versus those who had RN.7, 9-10, 12-13 Our aim was to determine if the risk of complications, levels of blood loss, and operative time increased with advancing patient age, and if the relationship between age and these outcomes differed by whether patients underwent a PN or RN procedure.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

After Institutional Review Board approval, we queried the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center renal surgery database for patients undergoing nephrectomy (radical or partial) from 1/2000 – 10/2008 and found 2,048 patients. Those with clinical features that might have routinely resulted in an RN (tumors > 10 cm, n = 221) or a PN (tumor in a solitary kidney, n=50; eGFR< 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, n = 18) were excluded. Those treated by a general surgeon (n = 11) were excluded. Finally, patients with missing information on age, eGFR, ASA score, or tumor size (n = 36) were excluded, leaving 1,712 patients available for analysis.

We collected patient/operative characteristics and 90-day postoperative complications. Postoperative complications are prospectively recorded in our renal surgery database and captured by a dedicated postoperative morbidity and mortality database. Complications within 90 days of surgery were graded and categorized in a similar manner to that described by Clavian et al and Shabsigh et al.14-16 (Table 1) Pathologic tumor size was used as a surrogate for preoperative size, typically determined by imaging.17 The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation was used to determine preoperative eGFR.18

Table 1.

Grading system for post-nephrectomy complications*

| Complication Grade | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1 | Use of oral medication or bedside intervention |

| 2 | Use of intravenous medication, total parenteral nutrition enteral supplementation, or blood transfusion |

| 3 | Requires invasive procedure (interventional radiology, therapeutic endoscopy, intubation, angiography, or operation) |

| 4 | Residual and lasting disability requiring major rehabilitation or organ resection |

| 5 | Death |

Adapted from Shabsigh et al. 16

Statistical methods

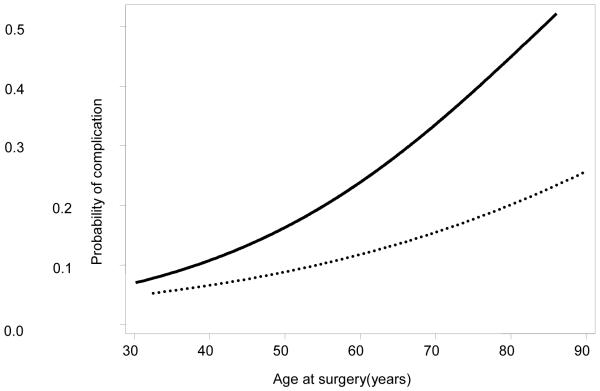

Our first aim was to evaluate the relationship between age and risk of postoperative complication overall. We created a multivariable logistic regression model that included as predictors: age, comorbidity (ASA score 3/4 vs 1/2), preoperative eGFR, open or laparoscopic procedure, procedure type (RN or PN), race (white non-Hispanic vs other), and pathologic tumor size. We originally planned to include restricted cubic spline terms for age to allow for a nonlinear relationship between age and complications; however, there was no evidence of a nonlinear relationship, so we entered age as a linear term. To test whether the association between age and complication rates differed significantly between PN and RN, we included an interaction term between age and procedure type in the model. If a significant interaction existed, one would expect the risk of complications to increase more rapidly with age for patients who underwent a PN rather than an RN (fig. 1 shows a hypothetical example of such an interaction). To illustrate the relationship between age and complications in our cohort, we created 2 multivariable logistic regression models, separately by procedure (RN and PN), and plotted the adjusted risk of complications by age from these models.

Figure 1. Hypothetical figure of probability of complication by age.

If there was a significant interaction between age and partial procedures, we would expect the predicted probability of complication to increase much more steeply with age for patients receiving a PN (solid line) than those receiving an RN (dotted line).

Our second aim was to determine if the relationship between age and operative time or EBL differed by procedure (RN or PN). Patients who were missing information on EBL (n = 25) or operative time (n = 240) were excluded, leaving 1,447 patients available for these analyses. We created a multivariable linear regression model for each outcome using the same predictors as the complication analysis. As these outcomes tend to be surgeon specific, we also corrected for surgeon by specifying the cluster option in Stata. The adjusted operative times by age were plotted by fitting models separately by procedure.

Currently the literature supports the use of elective partial nephrectomy in lesions up to 7 cm,6, 8, 19 but emerging data will likely continue to expand the indications for partial nephrectomy. We repeated the above analyses on a subgroup of our cohort restricted to patients with lesions 7 cm or less. Statistical tests were two-sided, and p values < 0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were conducted using Stata 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Of 1,712 patient, 651 (38%) underwent an RN and 1061 (62%) underwent a PN; characteristics of patients are shown in table 2. Patients who were treated with a radical procedure tended to be slightly older (median age, 63 vs 61 years) and have larger tumors (median size, 5.7 vs 2.8 cm) than those who underwent a PN.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Patient Characteristics | PN n= 1061 |

RN n= 651 |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative characteristics | ||

| Age at surgery (years) | 61 (52, 70) | 63 (54, 72) |

| Pathologic tumor size (cm)* | 2.8 (2.0, 3.8) | 5.7 (4.0, 7.5) |

| eGFR | 66 (58, 76) | 65 (56, 75) |

| ASA score | ||

| 1 | 53 (5%) | 19 (3%) |

| 2 | 601 (57%) | 357 (55%) |

| 3 | 405 (38%) | 269 (41%) |

| 4 | 2 (0.2%) | 6 (1%) |

| Male | 668 (63%) | 395 (61%) |

| Pathologic/operative characteristics | ||

| Open surgery | 909 (86%) | 540 (83%) |

| Lymph node dissection | 64 (6%) | 330 (51%) |

| Unadjusted outcomes | ||

| Any complication | 212 (20%) | 93 (14%) |

| EBL(cc) | 300 (200, 500) | 250 (150, 450) |

| Operative time (min) | 165 (134, 200) | 156 (119, 205) |

All values are median (IQR) or frequency (proportion).

GFR, glomerular filtration rate; ASA=American Society of Anesthesiologists

Pathologic tumor size used as surrogate for preoperative size from imaging (which was not available on clinical records)

Overall, 305 (18%) of 1,712 patients had a complication within 90 days of nephrectomy; 83% (253/305) only had 1 complication and 17% (52/305) had more than 1, for a total of 366 complications. Patients who were treated with an RN had a lower overall complication rate than those who were treated with a PN (14%;93/651 vs 20%;212/1061, respectively). A detailed listing of all 90-day postoperative complications experienced by patients in this cohort http://www.mskcc.org/postnephrectomycomplications/journalofurology.

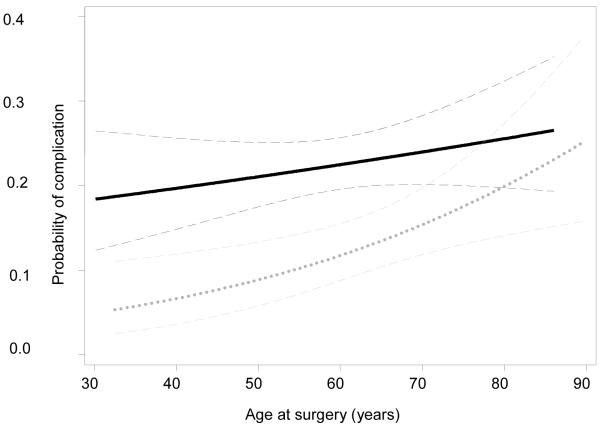

On univariate analysis, there was a small but statistically significant association between age and risk of complications (OR for 10-year increase in age: 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; p = 0.005), irrespective of procedure type. On multivariable analysis, age remained significantly associated with a small increased risk of having a complication, ), irrespective of procedure type. (OR for 10-year increase in age: 1.17; 95% CI, 1.04--1.32; p = 0.009). As the association between age and complications was modest, we did not expect to see large differences in the association between age and complications by procedure type (RN or PN). Figure 2 shows the age-adjusted complication rates by procedure type, separately for patients who were treated with either RN or PN. In a multivariable model that included an interaction term between age and procedure type, the interaction term was not significant (OR for interaction term between age and PN: 0.98; p = 0.09), indicating that there was no evidence of a differential effect of age on complications by procedure type.

Figure 2. Probability of complication by age.

Predicted probability of complication by age for patients receiving a PN (solid line) or RN (dotted line), adjusted for ASA score, eGFR, tumor size, race, and open vs laparoscopic procedure. N=1,712 Dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

We were concerned that our analysis was underpowered to detect a significant interaction, as only 40% (692/1712) and 13% (n/1712) of patients were older than 65 and 75 years, respectively. We saw no evidence that the risk of complications associated with a PN versus an RN increased with advancing age. The association was in the opposite direction of that hypothesized: The effect of age appeared to be stronger among patients who were treated with RN than among those treated by PN. For example, in men younger than 75 years, the OR for PN versus RN was 1.64 (95% CI, 1.22-2.21) compared to 1.12 (95% CI, 0.59-2.13) for men older than 75. If we set the age cutoff point at 65 years, we note a similar distribution of complications between young and older patients. Table 3 summarizes the highest grade complications for patients older and younger than 65 years, separately by procedure type.

Table 3.

Summary of highest grade complications for younger versus older patients

| Complication | Total n=1712 |

Younger (< 65 years) n = 1020 |

Older (≥ 65 years) n = 692 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RN | |||

| None | 558 (86%) | 324 (89%) | 234 (81%) |

| Low grade (1-2) | 73 (11%) | 29 (8%) | 44 (15%) |

| High grade (3-4) | 17 (3%) | 10 (3%) | 7 (2%) |

| Death (grade 5) | 3 (0.5%) | 0 | 3 (1%) |

| Total RN | 651 | 363 | 288 |

| PN | |||

| None | 849 (80%) | 539 (82%) | 310 (77%) |

| Low grade (1-2) | 151 (14%) | 82 (12%) | 69 (17%) |

| High grade (3-4) | 61 (6%) | 36 (5%) | 25 (6%) |

| Death (grade 5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total PN | 1061 | 657 | 404 |

Our second aim was to determine whether the association between age and EBL or operative time was differential by procedure type. Overall, we did not find any evidence that age was significantly associated with EBL or operative time. We did, however, find a significant interaction between age and procedure type for the outcome of operative time (p = 0.040); we did not find any evidence of an interaction for EBL (p = 0.6). Older patients who underwent an RN tended to have shorter operating times than those who underwent a PN (10-year increase in age was associated with a 6-min shorter operating time; 95% CI, 12-min shorter-5-min longer; p = 0.067); there was no significant association between age and operative time for patients who underwent a PN (p = 0.6).

In the subgroup analysis of tumors ≤ 7 cm, we found no important changes in our results. Patients experienced a similar proportion of complications (14% (RN) and 20% (PN)). Likewise, age had a modest association with risk of complications on multivariable analyses (OR 1.13; p=0.063) and the interaction term between age and type of procedure was not significant (HR 1.01; p=0.4).

DISCUSSION

We found PN had a higher overall complication rate compared with RN (20%;212/1061 vs 14%;93/651, respectively). Urinary fistula was more common in the PN group and is the most striking difference between the PN and RN complications. We saw no evidence that the effect of age on complication rates was differential by procedure type. If anything, our data suggest that the difference in complications between PN and RN narrows with increasing age. Additionally, we found no evidence of a significant association between age and EBL or operative time. Although we found a statistically significant interaction between age and procedure type for the outcome of operative time, this interaction is not likely to be clinically important. For example, the predicted operative times for a 45-year-old man undergoing a PN or RN were 175 and 181 minutes, respectively; for a 70-year-old man they were 161 and 183 minutes. Thus PN (compared to RN) was associated with a 6-minute longer procedure for the 45–year-old compared with a 22-minute longer procedure for the 70-year-old. It is unlikely that such a small difference in time would be clinically significant.

Despite the strong evidence that patients treated with PN have superior renal and cardiovascular outcomes than those treated with RN,20-23 the integration of PN into mainstream urologic practice has been slow. In separate studies using population-based data, investigators from the University of Michigan show that even though the use of PN is increasing, it is still stunningly low.1, 24 Miller et al report a 9.6% PN rate in their SEER cohort of early-stage kidney cancer diagnosed between 1988 and2001.1 Likewise, Hollenbeck et al report a PN rate of 7.5% in a group of renal surgery patients identified from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample between 1988 and 2002.23 In contrast, Thompson et al recently described the utilization of PN at a large, tertiary care center from 2000 through 2007; they showed that 56% of patients undergoing surgery for any size renal cortical tumor had a PN.2

The reason for this slow adoption of PN likely stems from multiple factors. Some urologists may be biased against PN because of lesser familiarity with contemporary PN techniques and concern that the technical challenges presented by some PN will increase complication rates or compromise cancer control. In turn, they may steer their patients toward laparoscopic or open RN. Such concerns for oncologic outcomes are unfounded, as PN has repeatedly been shown to match RN in terms of cancer control for the treatment of small renal masses.4-8, 19, 25 The concern for increased complications after PN is somewhat warranted, as the literature is conflicting on this matter. Some studies report similar complication rates between PN and RN,7, 9-10 while others suggest slightly higher rates with PN.11-12 A review of the literature by Lesage et al compiled studies comparing perioperative outcomes between PN and RN and concluded there was a trend towards a higher complication rate within the PN group, but no statistically significant difference.11 An ongoing Phase III randomized trial comparing PN and RN for the treatment of small renal masses demonstrated a slight increase in perioperative complications for the PN group, with the primary differences being between bleeding (rate of severe hemorrhage (>1 liter) 3.1% for PN vs 1.2% for RN) and urinary fistula rates (4.4% for PN vs 0% for RN).12 Nonetheless, they concluded that PN could be performed safely, with only a slightly higher complication rate than RN.

To our knowledge only 1 prior study examined the effect of age on complications after both PN and RN. Using data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, Joudi et al found that age was a significant predictor of complications among patients who underwent RN, but not those who underwent PN.13 Our results were similar in that advancing age did slightly increase the odds of experiencing a complication overall, but when stratified by procedure type (PN or RN) age was a statistically significant predictor of complications for patients treated with RN; we found no evidence that age was significantly associated with complications after PN.

This study, like all retrospective case series, has limitations, most notably, selection bias. In an attempt to reduce selection bias, we excluded patients with relative, preoperative indications for either PN or RN (tumors ≥ 10 cm, solitary kidney, and eGFR < 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Our series represents the experience of a tertiary care center, and these results may not be generalizable to the community. We realize some complications occurring outside of our institution may go undetected, but we believe our results are robust since unrecognized complications should not differentially affect older versus younger patients. The rigorous and prospective collection of complication data at our institution is a strength of this study. We purposefully did not focus on comparing open to laparoscopic approaches, as this has been exhaustively debated in the literature.26-27 Instead, we believe the focus should be on kidney preservation after oncologic control, regardless of the approach.

Clearly not all patients are candidates for PN despite tumor size, as some tumor locations are not amenable to nephron-sparing treatment. Contemporary treatment of renal masses involves not only surgery, but also surveillance. Some elderly, comorbid patients may be better served with active surveillance rather than curative treatment.28

In sum, we found that PN had slightly higher rates of complications than RN; however, these differences did not appear to increase with advancing age. Thus age alone should not be considered a reason for not offering PN as a treatment option. Given the substantial advantages associated with renal function preservation, we feel our data support expanded use of nephron-sparing approaches for amenable tumors in elderly patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Although there was a slightly higher overall complication rate for the patients who underwent PN compared with those who underwent RN, there was no evidence that this difference in complication rates increased with advancing age. In appropriately selected patients, the concern for increased blood loss, higher rate of complications, or prolonged operative time should not cause urologists to steer patients away from PN solely because of older age.

Acknowledgment

This project was partially supported by NIH T32 CA82088 Urologic Oncology training grant and the Sidney Kimmel Center for Prostate and Urologic Cancers. We are also indebted to the Stephen Hanson Family Fellowship for their support. We also thank Dagmar Schnau of MSKCC for substantive editing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Note: A detailed listing of all complications experienced by patients in this cohort can be found at http://www.mskcc.org/postnephrectomycomplications/journalofurology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller DC, Hollingsworth JM, Hafez KS, et al. Partial nephrectomy for small renal masses: an emerging quality of care concern? J Urol. 2006;175:853. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson RH, Kaag M, Vickers A, et al. Contemporary use of partial nephrectomy at a tertiary care center in the United States. J Urol. 2009;181:993. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson RH, Ordonez MA, Iasonos A, et al. Renal cell carcinoma in young and old patients--is there a difference? J Urol. 2008;180:1262. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fergany AF, Hafez KS, Novick AC. Long-term results of nephron sparing surgery for localized renal cell carcinoma: 10-year followup. J Urol. 2000;163:442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee CT, Katz J, Shi W, et al. Surgical management of renal tumors 4 cm. or less in a contemporary cohort. J Urol. 2000;163:730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leibovich BC, Blute ML, Cheville JC, et al. Nephron sparing surgery for appropriately selected renal cell carcinoma between 4 and 7 cm results in outcome similar to radical nephrectomy. J Urol. 2004;171:1066. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000113274.40885.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau WK, Blute ML, Weaver AL, et al. Matched comparison of radical nephrectomy vs nephron-sparing surgery in patients with unilateral renal cell carcinoma and a normal contralateral kidney. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:1236. doi: 10.4065/75.12.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patard JJ, Shvarts O, Lam JS, et al. Safety and efficacy of partial nephrectomy for all T1 tumors based on an international multicenter experience. J Urol. 2004;171:2181. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000124846.37299.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corman JM, Penson DF, Hur K, et al. Comparison of complications after radical and partial nephrectomy: results from the National Veterans Administration Surgical Quality Improvement Program. BJU Int. 2000;86:782. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephenson AJ, Hakimi AA, Snyder ME, et al. Complications of radical and partial nephrectomy in a large contemporary cohort. J Urol. 2004;171:130. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000101281.04634.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lesage K, Joniau S, Fransis K, et al. Comparison between open partial and radical nephrectomy for renal tumours: perioperative outcome and health-related quality of life. Eur Urol. 2007;51:614. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Poppel H, Da Pozzo L, Albrecht W, et al. A prospective randomized EORTC intergroup phase 3 study comparing the complications of elective nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy for low-stage renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2007;51:1606. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joudi FN, Allareddy V, Kane CJ, et al. Analysis of complications following partial and total nephrectomy for renal cancer in a population based sample. J Urol. 2007;177:1709. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clavien PA, Sanabria JR, Strasberg SM. Proposed classification of complications of surgery with examples of utility in cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1992;111:518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shabsigh A, Korets R, Vora KC, et al. Defining Early Morbidity of Radical Cystectomy for Patients with Bladder Cancer Using a Standardized Reporting Methodology. Eur Urol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurta JM, Thompson RH, Kundu S, et al. Contemporary imaging of patients with a renal mass: does size on computed tomography equal pathological size? BJU Int. 2009;103:24. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dash A, Vickers AJ, Schachter LR, et al. Comparison of outcomes in elective partial vs radical nephrectomy for clear cell renal cell carcinoma of 4-7 cm. BJU Int. 2006;97:939. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang WC, Elkin EB, Levey AS, et al. Partial Nephrectomy Versus Radical Nephrectomy in Patients With Small Renal Tumors-Is There a Difference in Mortality and Cardiovascular Outcomes? J Urol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang WC, Levey AS, Serio AM, et al. Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:735. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70803-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller DC, Schonlau M, Litwin MS, et al. Renal and cardiovascular morbidity after partial or radical nephrectomy. Cancer. 2008;112:511. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson RH, Boorjian SA, Lohse CM, et al. Radical nephrectomy for pT1a renal masses may be associated with decreased overall survival compared with partial nephrectomy. J Urol. 2008;179:468. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hollenbeck BK, Taub DA, Miller DC, et al. National utilization trends of partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: a case of underutilization? Urology. 2006;67:254. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lerner SE, Hawkins CA, Blute ML, et al. Disease outcome in patients with low stage renal cell carcinoma treated with nephron sparing or radical surgery. J Urol. 1996;155:1868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breda A, Finelli A, Janetschek G, et al. Complications of Laparoscopic Surgery for Renal Masses: Prevention, Management, and Comparison with the Open Experience. Eur Urol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porpiglia F, Volpe A, Billia M, et al. Laparoscopic versus open partial nephrectomy: analysis of the current literature. Eur Urol. 2008;53:732. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jewett MA, Zuniga A. Renal tumor natural history: the rationale and role for active surveillance. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35:627. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]