Abstract

Purpose of Review

It has been argued, that the existing epidemiologic data are insufficient to establish a causal link between acute kidney injury (AKI) and subsequent development or progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD), especially given that risk factors for the development of AKI overlap with those for progressive CKD.

Recent Finding

Multiple studies published over the past 5 years have demonstrated a strong epidemiologic association between episodes of AKI and subsequent development or progression CKD, including evidence that severity of AKI and repeated episodes of AKI are associated with increased risk of CKD. In addition, animal models have provided evidence for a biological basis linking episodes of AKI with CKD

Summary

The preponderance of data support a causal link between episodes of AKI and subsequent development or progression of CKD

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Chronic kidney disease, Epidemiology

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common complication of hospitalization, particularly in the setting of critical illness, occurring during up to 20% of hospital admissions (1, 2). It is well recognized that AKI is associated with significant short-term morbidity and mortality, with hospital mortality rates exceeding 50% when severe AKI complicates critical illness (3). The effect of AKI on longer-term outcomes has been less well elucidated, but has received increasing attention over the course of the past decade. In addition, the use of consensus definitions for AKI that have standardized categorization of less severe decrements in kidney function has facilitated the analysis of milder degrees of AKI on long-term kidney function (4-6). These analyses have challenged the classic teaching that the majority of patients who survive an episode of AKI have near complete recovery of kidney function and an excellent long-term prognosis (7) and have demonstrated a strong association between episodes of AKI and subsequent development of and progression of CKD (8, 9). It has been argued, however, that the existing epidemiologic data are insufficient to establish causality, especially given that risk factors for the development of AKI overlap with those for progressive CKD (10). In this review we summarize both the epidemiologic and experimental data relating AKI to CKD and assess the strength of the data supporting a causal association.

Case Series Describing the Outcome of Severe AKI

Case series dating back to the 1950s described residual functional abnormalities among patients surviving episodes of dialysis-requiring AKI. For example, in a study published in 1952, Lowe evaluated 14 patients who survived episodes of acute tubular necrosis (ATN) and reported that 3 out of 8 patients had a creatinine clearance of <80 ml/min despite the absence of evidence of baseline renal impairment, and attributed the renal dysfunction to “scarring or vascular damage” (11). Similarly, in 1956, Finkenstaedt and Merrill provided follow-up on16 patients who survived severe AKI at 13-76 months (12). Six of the 16 patients were found to have inulin clearances of <70 ml/min despite having no evidence of prior renal dysfunction concluding that the AKI “resulted in more chronic renal damage than would be expected,” and speculating that the chronic dysfunction resulted from nephron loss, basement membrane rupture and abnormal epithelial regeneration. Subsequent studies demonstrated residual defects in tubular function, including acidification defects, tubular wasting of electrolytes and renal concentrating defects (13, 14). Based on these early studies, classic textbook teaching had been that the majority of patients surviving an episode of severe AKI resulting from acute tubular necrosis had a good prognosis, with statements such as “…the vast majority of patients who survive an episode of ATN achieve clinically normal function and maintain it indefinitely, despite the persistence of subtle functional defects in many” (15).

Several case series have highlighted a high mortality rate in patients surviving an episode of AKI and have suggested an increased risk for progressive kidney disease. Liano and colleagues followed a cohort of 187 consecutive patients from Madrid, Spain for up to 22 years (median 7.2 years) after surviving an episode of severe AKI attributable to ATN (16).Ninety-five patients (51%) died during follow-up with Kaplan-Meir estimates of survival of50% at 10 years and 40% at 15 years. Fifty-seven of the surviving patients (62%) had their kidney function assessed; the vast majority were characterized as having normal kidney function, although 15.8% had mild and 3.5% had moderate impairment of kidney function and 3 patients (1.7%) had developed a need for chronic dialysis, at 6, 11 and 12 years of follow-up. Schiffl and colleagues provided long-term follow-up of a cohort of 425 critically ill patients with severe AKI secondary to ATN from a single center (17). The overall in-hospital mortality was 47%; among survivors, recovery of kidney function at hospital discharge was complete (defined as GFR within 10% of baseline) in 57%, and partial in 43%.None of the surviving patients needed dialysis at the time of discharge. After five-years of follow-up only 25% of the initial cohort remained alive. Of the surviving patients, 86% had normal kidney function, 5% had developed ESRD and 9% had impaired kidney function.

Epidemiological Associations between AKI and Development of CKD in Adults

A series of epidemiologic studies published since 2009 have demonstrated a strong association between AKI and CKD. Using administrative data from a 5%sample of Medicare beneficiaries and linking to data from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), Ishani and colleagues observed a hazard of developing ESRD during two years of follow-up approximately 6.5-times greater (95% CI: 5.9 – 7.7) in patients who had a discharge diagnosis of AKI as compared to patients without AKI (18). When stratified based on the presence of underlying CKD, the hazard for developing ESRD was 13-times higher (95% CI: 10.6-16.0) in patients with de novo AKI and approximately 41-times higher (95% CI: 34.6 – 49.1) in patients with acute-on-chronic kidney disease as compared to matched patients surviving acute illness with no diagnoses of acute or chronic kidney disease. In contrast, the 2-year hazard of developing ESRD in patients with CKD but no AKI was 8.4-times (95% CI: 7.4 – 9.6) that of patients with no underlying kidney disease (18).

In a retrospective study using data from the Kaiser Permanente of Northern California Health System on 343 patients who survived an episode of dialysis-requiring AKI and remained dialysis independent for at least 30 days after hospital discharge and 3430 matched patients without AKI, Lo and colleagues reported a 28-fold increased risk of developing advanced CKD (95% CI: 21.1 – 37.6) following an episode AKI (19) The hazard was even higher in patients with baseline preserved kidney function (HR: 54.0; 95% CI: 34.3 – 85.1). During 10,344 person-years of follow up, 322 patients developed progressive CKD, defined as an estimated GFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2, and 41 patients progressed to ESRD, giving an event rate for progressive CKD of 47.9 per 100-person years for AKI patients compared to 1.7 per 100-person years for non-AKI patients.

Using provincial health registry data from Ontario, Canada, Wald and colleagues observed an incidence rate for ESRD of 2.63 cases per 100 person-years over 10 years of follow-up in patients surviving an episode of dialysis-requiring AKI and who remained dialysis-independent 30 days after hospital discharge as compared to 0.91 cases per 100 person-years in a matched cohort of patients who did not have AKI (hazard ratio 3.2; 95% CI: 2.7-3.9) (20). In a subsequent analysis of patients who had non-dialysis-requiring AKI, the corresponding incidence rates for ESRD were 1.8 and 0.7 cases per 100 person-years (HR: 2.7; 95% CI: 2.4-3.0) (21).

Amdur and colleagues assessed long-term kidney function in patients with no prior history of CKD who were hospitalized with AKI, using an electronic database from the United Sates Department of Veterans Affairs and comparing outcomes to patients without evidence of kidney disease who were hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction or pneumonia (22). They also found that AKI was associated with an increased risk for development of advanced CKD and reduced survival as compared to controls. In a subsequent analysis, the authors reported that severity of AKI was a robust predictor of risk for development and progression of CKD (23). Other predictors of progression in this cohort that excluded patients with underlying CKD were advanced age, low serum albumin levels and a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus.

In 2012, Coca et al. published a systematic review and meta-analysis of the epidemiologic studies that addressed the risk CKD after AKI (8). They reported a pooled incidence of CKD in the 13 included studies of 25.5 cases per 100-person years (range 3.4-72.2) an adjusted hazard ratio for development of CKD of 8.8 (95% CI: 3.0 – 25.5). Similarly, the pooled incidence of ESRD was 8.6 cases per 100-person years (range 0.6-28.1) giving an adjusted hazard ratio of 3.1 (95% CI: 1.9-5.0).

In a subsequent study that was not included in this meta-analysis, Bucaloiu and colleagues interrogated the electronic medical records from the Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania to examine the risks for death and de novo CKD in patients with no history of kidney disease who developed AKI with subsequent complete recovery of kidney function (defined as an eGFR of at least 90% of baseline) within 90 days (24). They observed a hazard for development of de novo CKD over a follow-up period of up to 6 years of 1.9 (95% CI: 1.8 – 2.1) as compared to patients with no history of either AKI or CKD, with a hazard for death of 1.5 (95% CI: 1.2 – 1.8). Of note, however, there was significant interaction between risk for development of CKD and mortality risk; after adjusting for development of CKD, the hazard for death was attenuated and was no longer statistically significant.

Two subsequent analyses have also demonstrated associations between severity or recurrent episodes of AKI and subsequent CKD. Using the Department of Veterans Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database, Ishani and colleagues observed a progressive risk for development of CKD with graded severity of post-cardiac surgery AKI, using definitions based on maximal increases in serum creatinine ranging from < 25% (no AKI) to > 100% (25). In another study utilizing VA data, Thakar and colleagues observed a relationship between the number of episodes of AKI and subsequent development of stage 4 CKD in a cohort of 3,679 patients with diabetes mellitus at a single VA Medical Center (26). The hazard for development of stage 4 CKD is patients with AKI was 3.6 (95% CI: 2.8-4.6) as compared to patients with no AKI, and doubled with each episode of AKI (HR 2.0; 95% CI: 1.8 – 2.3).

While these studies all demonstrate a similar strong association between AKI and subsequent CKD, they are unable to establish an etiologic association. In addition to underlying CKD being a risk factor for AKI, underlying hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease are implicated as risk factors for both AKI and CKD. Although adjustment for these factors in multivariable statistical models can attempt to adjust for this, residual confounding cannot be ruled out. Thus it remains possible that rather than being a mediator for the development of CKD, episodes of AKI are merely markers of risk, reflecting the severity of other underlying etiologic factors.

Associations between AKI and Development of CKD in Children

Unlike a large proportion of adults who develop AKI superimposed on a substrate of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic vascular disease and underlying CKD, these factors generally do not underlie the development of AKI in children.(2). Thus, the subsequent development of CKD in children surviving an episode of AKI is more readily attributable to residual kidney injury for the AKI. Askenazi and colleagues have reported on the longitudinal follow-up of 174 children from a single tertiary care center of who had AKI between 1998 and 2001 and survived to hospital discharge (27). The majority of these children had complete recovery of kidney function, although 24 (14%) incomplete recovery of kidney function and 11 (5%) were dialysis-dependent at hospital discharge (28). During the subsequent follow-up, 35 children (21.1%) died and 16 (9.2%) progressed to ESRD. Twenty-nine surviving children without ESRD underwent formal renal functional testing. Seventeen of the 29 (58.6%) children had evidence of chronic kidney injury; six were hypertensive, eight had albuminuria, and nine had hyperfiltration (creatinine clearance >150 ml/min/1.73 m2) and four had reduced GFR (creatinine clearance <90 ml/min/1.73 m2).Although these findings must be interpreted with caution since only a minority of the surviving children were evaluated, and there was overrepresentation of children with underlying renal and urologic disease, these studies do suggest a significant burden of chronic kidney disease on pediatric survivors of AKI.

Follow-up of children who developed enterotoxigenic hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) as the result of contamination of a municipal water supply with E. coli O157:H7 also provides insight into the effect of AKI on subsequent kidney function (29). Of 28 children who developed HUS, one child had pre-existent proteinuria and one child died. Nineteen of the remaining 26 children underwent follow-up evaluation for 5 years after the outbreak. Three of 15 (20%) of the children who had HUS had elevated urine albumin excretion as compared to 2 of 60 (3%) of unaffected children (relative risk: 6.0; 95% CI: 1.1 – 32.8). Although there was no difference in serum creatinine levels, the children who had HUS had higher serum cystatin C concentrations (0.93±0.1 vs. 0.86±0.1, p=0.01) and lower cystatin C-based estimated GFRs (100±12.2 vs. 110±15.5, p=0.02) as compared to unaffected controls. Thus, in this cohort of children with no prior history of kidney disease, AKI due to HUS is associated with residual kidney damage; however these findings may not be generalizable to other etiologies of AKI.

Animal Data Supporting an Etiological Association between AKI and CKD

Data from experimental models of AKI provide insight into biological mechanisms by which AKI contributes to subsequent CKD and support an etiologic relationship (9, 30). A detailed discussion of this data is beyond the scope of this review and is provided elsewhere in this issue (31). Among the implicated mechanisms has been vascular rarefaction, as demonstrated by studies which showed a 30-50% reduction in peritubular capillary density in the inner stripe of the outer medulla following ischemia reperfusion injury (32). This loss of vascularity is hypothesized to lead to tubulointerstitial hypoxia, tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis. It has been shown that recovery from AKI is characterized by proliferation of tubular epithelial cells (33). However, with severe AKI there is an increase in the number of proximal tubule epithelial cells arrestedin the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (33, 34). Cell cycle arrest is associated with increased production of profibrotic cytokines including transforming growth factor β-1 (TGF β-1) and connective tissue growth factor (33, 34).

Conclusion

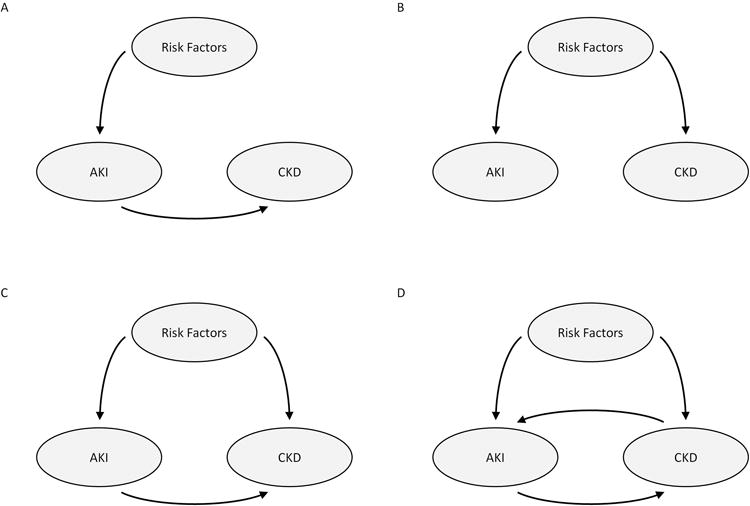

Despite the strong epidemiologic association between AKI and subsequent development or progression of CKD these studies alone cannot establish causality (10). Many of the risk factors for AKI are also independent risk factors for the development or progression of CKD (Figure 1). Although statistical models can be used to adjust for these common risks, there is significant potential for residual confounding. The preponderance of evidence, however, supports the presence of a causal link between AKI and CKD (35). Nine criteria (Table 1) have generally been accepted as necessary for inference of causality in observational associations (36); to some extent, all nine of these are fulfilled in evaluating AKI as a cause for CKD. In laying out these criteria in his address to the Royal Society of Medicine, Sir Austin Bradford Hill cautioned that none of these criteria “…can bring indisputable evidence for or against the cause-and-effect hypothesis and none can be required as a sine qua non” (36).

Figure 1. Potential Models for the Association between AKI and CKD.

A. Risk factors contribute to the development of AKI which is on the causal path to development of or progression of CKD

B. Risk factors independently contribute to the development of both AKI and CKD and AKI is not on the causal path for the development of CKD

C. Risk factors contribute independently to the development of both AKI and CKD and AKI is on the causal path for development of CKD

D. Risk factors contribute independently to the development of both AKI and CKD; AKI is on the causal path for development of CKD; and CKD is a risk factor for the development of AKI

Table 1. Criteria for Inference of Causality for Observational Associations.

|

It is certainly true that many patients who sustain an episode of AKI do not subsequently develop CKD and that the risk of subsequent CKD may vary with both etiology and severity of an acute injury. While a randomized trial of induction of AKI would provide definitive proof of the presence or absence of a causal relationship for subsequent CKD in surviving patients, such a study would be patently unethical. However, demonstration that an intervention that significantly mitigates the risk for AKI also diminishes the risk for subsequent CKD would be strong, albeit less definitive evidence for causation. While more rigorous studies of the long-term sequelae of AKI are needed, and several are underway, the preponderance of data currently support the existence of a causal pathway between episodes of AKI and subsequent development of or progression of CKD. Emphasis should therefore be placed on prevention of AKI, not only to mitigate the short-term morbidity and mortality, but also to diminish the long-term consequences on kidney function.

Key Points.

There is a strong epidemiologic association between development of acute kidney injury and subsequent development and progression of chronic kidney disease

The epidemiologic association is seen across a broad array of clinical settings, with a graded risk with increased severity or increased number of episodes of acute kidney injury

The link between acute kidney injury and subsequent chronic kidney disease is supported by experimental data demonstrating vascular rarefaction and activation of fibrotic pathways following acute kidney injury

Common risk factors for the development of both acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease make it difficult to definitively establish a causal relationship on the basis of epidemiologic data

The preponderance of evidence supports the causal link between acute kidney injury and subsequent chronic kidney disease

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest

References

- 1*.Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349–355. doi: 10.1159/000337487. An analysis of data from a single academic medical center to determine the current incidence of acute kidney injury and the associated mortality risk in hospitalized patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2*.Heung M, Chawla LS. Predicting progression to chronic kidney disease and recovery from acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2012;21:628–634. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283588f24. A review of the association between acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3*.Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C. Acute kidney injury. Lancet. 2012;380:756–766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61454-2. A general review of acute kidney injury. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative workgroup. Acute renal failure—definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the second international consensus conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204–R212. doi: 10.1186/cc2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV Acute Kidney Injury Network. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6**.The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Working Group. Definition and classification of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–138. An international clinical practice guideline on the diagnosis and management of acute kidney injury providing the most current consensus definition and staging system for acute kidney injury. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finn WF. Recovery from acute renal failure. In: Brenner BM, Lazerus JM, editors. Acute Renal Failure. W.B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 8**.Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR. Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2012;81:442–448. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.379. A meta-analysis of published studies demonstrating a strong epidemiologic association between acute kidney injury and subsequent chronic kidney disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9**.Chawla LS, Kimmel PL. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease: an integrated syndrome. Kidney Int. 2012;82:516–524. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.208. A review article summarizing the clinical and experimental data supporting a causal association between acute kidney injry and chronic kidney disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10**.Rifkin DE, Coca SG, Kalantar-Zedeh K. Does AKI truly lead to CKD? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:979–984. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011121185. A commentary reviewing the criteria for establishing a causal relationship based on epidemiologic data questioning whether such criteria are met for the association between acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowe KG. The late prognosis in acute tubular necrosis; an interim follow-up report on 14 patients. Lancet. 1952;31(6718):1086–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(52)90744-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkenstaedt JT, Merrill JP. Renal function after recovery from acute renal failure. N Engl J Med. 1956;254:1023–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195605312542203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briggs JD, Kennedy AC, Young LN, Luke RG, Gray M. Renal function after acute tubular necrosis. Br Med J. 1967;3(5564):513–516. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5564.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewers DT, Mathew TH, Maher JF, Schreiner GA. Long-term follow-up of renal function and histology after acute tubular necrosis. Ann Intern Med. 1970;73:523–529. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-73-4-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levinsky NG, Alexander EA, Venkatachalam MA. Acute renal failure. In: Brenner BM, Rector FC Jr, editors. The Kidney. 2nd. W.B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liaño F, Felipe C, Tenorio MT, Rivera M, Abraira V, Sáez-de-Urturi JM, Ocaña J, Fuentes C, Severiano S. Long-term outcome of acute tubular necrosis: a contribution to its natural history. Kidney Int. 2007;71:679–686. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiffl H, Fischer R. Five-year outcomes of severe acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:2235–2241. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishani A, Xue JL, Himmelfarb J, Eggers PW, Kimmel PL, Molitoris BA, Collins AJ. Acute kidney injury increases risk of ESRD among elderly. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:223–228. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007080837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo LJ, Go AS, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordoñez JD, Hsu CY. Dialysis-requiring acute renal failure increases the risk of progressive chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2009;76:893–899. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wald R, Quinn RR, Luo J, Li P, Scales DC, Mamdani MM, Ray JG University of Toronto Acute Kidney Injury Research Group. Chronic dialysis and death among survivors of acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. JAMA. 2009;302:1179–1185. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21*.Wald R, Quinn RR, Adhikari NK, Burns KE, Friedrich JO, Garg AX, Harel Z, Hladunewich MA, Luo J, Mamdani M, Perl J, Ray JG University of Toronto Acute Kidney Injury Research Group. Risk of chronic dialysis and death following acute kidney injury. Am J Med. 2012;125:585–593. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.01.016. An epidemiologic study exploring the association between non-dialysis requiring acute kidney injury and subsequent long-term risk for ESRD and death. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amdur RL, Chawla LS, Amodeo S, Kimmel PL, Palant CE. Outcomes following diagnosis of acute renal failure in U.S. veterans: focus on acute tubular necrosis. Kidney Int. 2009;76:1089–1097. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chawla LS, Amdur RL, Amodeo S, Kimmel PL, Palant CE. The severity of acute kidney injury predicts progression to chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1361–1369. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24**.Bucaloiu ID, Kirchner HL, Norfolk ER, Hartle JE, 2nd, Perkins RM. Increased risk of death and de novo chronic kidney disease following reversible acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;81:477–485. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.405. An epidemiologic study demonstrating an increased risk for subsequent chronic kidney disease in patients with normal baseline kidney function who sustain an episode of acute kidney injury and have complete recovery of kidney function. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishani A, Nelson D, Clothier B, Schult T, Nugent S, Greer N, Slinin Y, Ensrud KE. The magnitude of acute serum creatinine increase after cardiac surgery and the risk of chronic kidney disease, progression of kidney disease, and death. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:226–233. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thakar CV, Christianson A, Himmelfarb J, Leonard AC. Acute kidney injury episodes and chronic kidney disease risk in diabetes mellitus. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2567–2572. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01120211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Askenazi DJ, Feig DI, Graham NM, Hui-Stickle S, Goldstein SL. 3-5 year longitudinal follow-up of pediatric patients after acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2006;69:184–189. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hui-Stickle S, Brewer ED, Goldstein SL. Pediatric ARF epidemiology at a tertiary care center from 1999 to 2001. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:96–101. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garg AX, Salvadori M, Okell JM, Thiessen-Philbrook HR, Suri RS, Filler G, Moist L, Matsell D, Clark WF. Albuminuria and estimated GFR 5 years after Escherichia coli O157 hemolytic uremic syndrome: an update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:435–444. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venkatachalam MA, Griffin KA, Lan R, Geng H, Saikumar P, Bidani AK. Acute kidney injury: a springboard for progression in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F1078–1094. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00017.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonventre JV. Impact of AKI on CKD progression Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 2014 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basile DP, Donohoe D, Roethe K, Osborn JL. Renal ischemic injury results in permanent damage to peritubular capillaries and influences long-term function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F887–899. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.5.F887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang L, Besschetnova TY, Brooks CR, Shah JV, Bonventre JV. Epithelial cell cycle arrest in G2/M mediates kidney fibrosis after injury. Nat Med. 2010;16:535–543. doi: 10.1038/nm.2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wynn TA. Fibrosis under arrest. Nat Med. 2010;16:523–525. doi: 10.1038/nm0510-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35**.Hsu Cy. Yes, AKI truly leads to CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:967–969. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012030222. A response to the commentary by Rifkin, et al (reference 10), arguing that the evidence supports a causal relationship between acute kidney injury and subsequent chronic kidney disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:295–300. doi: 10.1177/003591576505800503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]