Abstract

Heroin continues to be the main drug used in Malaysia, while amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) have been recently identified as a growing problem. A cumulative total of 300,241 drug users were detected between 1988 and 2006. It is also estimated that Malaysia has 170,000 injecting drug users. HIV prevalence among drug users in the country ranges from 25% to 45%. Currently, there are approximately 380 general medical practice offices that offer agonist maintenance treatments for approximately 10,000 patients. There are 27,756 active patients in 333 general medical practice offices and government-run methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) centers. The Needle Syringe Exchange Program (NSEP) reached out to 34,244 injection drug users (IDUs) in 2011. In the last 2 years (2011 and 2012) the number of detected drug addicts decreased from 11,194 to 9015. The arrests made by the police related to opiate and cannabis use increased from 41,363 to 63,466 between the years 2008 and 2010, but decreased since 2010. An almost four-fold increase in the number of ATS and ketamine users was detected from 2006 (21,653 users) 2012 (76,812). Between 2004 and 2010, the yearly seizures for heroin ranged between 156 to 270 kg. However, in 2010 and 2011, heroin seizures showed a significant increase of 445kg and 410.02 kg, respectively. There has been a seizure of between 600 to 1000kg of syabu yearly from 2009 to 2012. Similar to heroin, increased seizures for Yaba have also been observed over the last 2 years. A significant increase has also been recorded for the seizures of ecstasy pills from 2011 (47,761 pills) to 2012 (634,573 pills). The cumulative number of reported HIV infections since 1986 is 94,841. In 2011, sexual activity superseded injection drug use as the main transmission factor for the epidemic. HIV in the country mainly involves males, as they constitute 90% of cumulative HIV cases and a majority of those individuals are IDUs. However, HIV infection trends are shifting from males to females. There are 37,306 people living with HIV (PLHIV) who are eligible for treatment, and 14,002 PLHIV were receiving antiretroviral treatment (ART) in 2011. The decreasing trend of heroin users who have been detected and arrested could be due to the introduction of medical treatments and harm reduction approaches for drug users, resulting in fewer drug users being arrested. However, we are unable to say with certainty why there has been an increase in heroin seizures in the country. There has been an increasing trend in both ATS users and seizures. A new trend of co-occurring opiate dependence and ATS underscores the need to develop and implement effective treatments for ATS, co-occurring opiate and ATS, and polysubstance abuse disorders. The low numbers of NSEP clients being tested for HIV underscores our caution in interpreting the decline of HIV infections among drug users and the importance of focusing on providing education, prevention, treatment, and outreach to those who are not in treatment.

Keywords: drug user, heroin, opiates, amphetamine type stimulants (ATS), HIV

1. Introduction

Malaysia is an Islamic country in Southeast Asia with a population of 29,703,240 [1]. It is situated close to the golden triangle and, historically, opium was used in Malaysia largely by the Chinese immigrants. In 1929, it had 52,313 registered opium users. By 1941, there were 75,000 opium users. The “hippy culture” in the 1970s and the Vietnam War resulted in the introduction of cannabis and heroin to Malaysia [2]. Heroin is commonly smoked or injected in Malaysia. Recently, amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS), including crystal methamphetamine and various other methamphetamine and/or amphetamine-containing substances/pills, have been identified as a growing problem, not only in Malaysia but throughout the Southeast Asia Region [3-5]. In our previous study, approximately 60% of opioid injecting drug users (IDUs) in Malaysia reported lifetime use of ATS, with 29% also reporting lifetime injection of ATS [6].

Between 1988 and 2006, a cumulative total of 300,241 drug users were detected, representing about 1.1% of the total population [7]. It is estimated that there are 170,000 IDUs in the country [8]. HIV prevalence among drug users in Malaysia ranges from 25% to 45% [9]. In another previous study of ours, HIV prevalence of 43.9% was reported among IDUs not in treatment [6].

Malaysia drug policy was largely shaped from a security standpoint, with the Ministry of Home Affairs being responsible for dealing with issues related to drug use and drug trafficking. Subsequently, this meant that the problem of drug use was largely seen as a threat to national security. Severe criminal penalties were given to drug users, which often included prison sentences. In regard to drug treatment, only mandatory institutional drug rehabilitation for a period of 2 years was provided through the criminal justice system. These mandatory institutional facilities did not provide medically assisted treatment programs and were more geared towards rehabilitating the physical aspects of the drug user. This program was not successful and resulted in high relapse rates, ranging from 70% to 90% within the first year following discharge [10].

In response to the continuing problems with heroin dependence and the emerging HIV/AIDS epidemic resulting from injecting drug use, Malaysia introduced opiate agonist maintenance treatment (OMT). Buprenorphine and methadone were approved in 2002 and 2003, respectively. Besides introducing OMT, Malaysia also implemented a needle syringe exchange program (NSEP) and started restructuring its mandatory institutional rehabilitation program. Currently, approximately 380 general medical practice offices offer agonist maintenance treatments for approximately 10,000 patients. There are 27,756 active patients in 333 general medical practice offices and government-run methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) centers. MMT programs were also introduced into prisons, beginning with one prison in 2008 and expanding to 18 MMTs in prisons by 2011. Twenty-one government-run compulsory drug rehabilitation centers are still open (including one center for females), with a total of 5,102 residents/inmates undergoing rehabilitation in 2012. Forty-two voluntary government treatment and rehabilitation centers, known as Cure and Care Service Centres, had 1,836 residential and 176,929 non-residential inmates/patients in 2012. The needle syringe exchange program (NSEP) started in 2006 and has reached out to 34,244 IDUs, with an average distribution of needle/syringe sets of about 116 per IDU per year (2011).

In this paper, we will describe and discuss the trends of substance abuse and HIV in Malaysia.

2. Method

Secondary data were collected by the authors mainly from the National Anti Drug Agency, which manages the national database on drug abuse in Malaysia, the Royal Malaysian Police, which maintains all drug seizure data, and the Ministry of Health, which maintains the HIV/AIDS database in the country. In addition to local databases, country data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and UN country reports were used. A literature search using the Web was conducted to identify other relevant published studies.

3. Results

3.1 Drug use

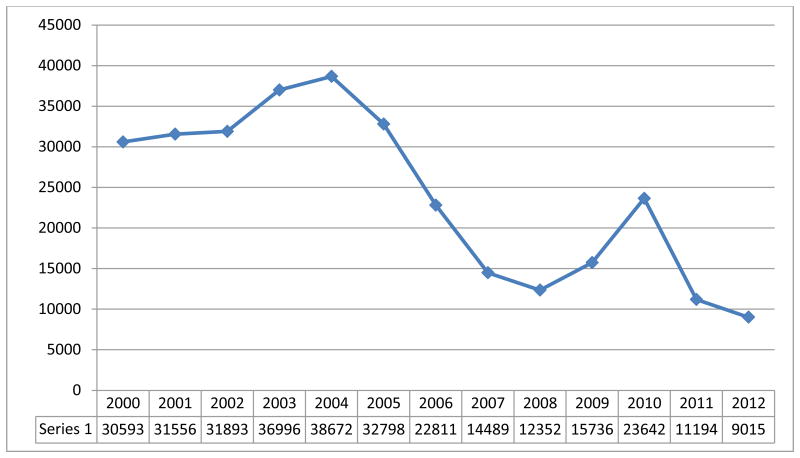

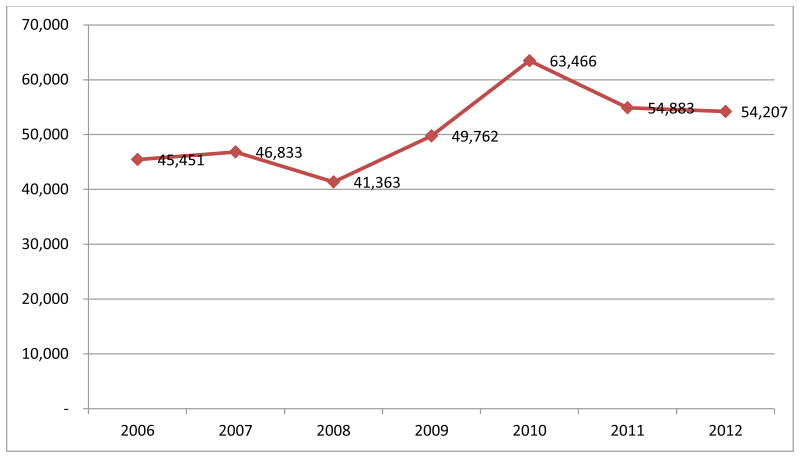

Similar trends in the number of drug addicts detected and number of drug users arrested are observed in Figures 1 and 2: there was an increase between 2008 and 2010 and a decrease from 2010 to 2012.

Figure 1. Number of drug addicts detected from year 2000 -2012.

Source: National Anti Drug Agency (2013)

Figure 2. Arrest under section 3(1) Drug Dependents Act (Treatment and Rehabilitation) 1983, related to opiate and cannabis drug use from 2006 – 2012.

Source: Royal Malaysia Police (2012)

In Figure 2, the “section 3(1) Drug Dependents Act (Treatment and Rehabilitation) 1983” refers to drug users who were arrested by the police. They tested positive for opiates or cannabis but had not been determined to be addicted to drugs; whereas in Figure 1, the data provided by the National Anti Drug Agency are for those who have been medically certified to be addicted to drugs. We could not obtain data from 2000 to 2005 for arrests made under section 3(1) Drug Dependents Act to compare with the number of detected drug users detected shown in Figure 1.

Approximately 30,000 to 40,000 drug addicts were detected annually from 2000 to 2005. The number of drug addicts detected between 2004 and 2008 decreased considerably (from 38,672 to 12,352) and slightly increased (from 15,736 to 23,642) in 2009 and 2010. Similarly, in the last two years (2011 and 2012), the number of drug addicts detected by the National Anti Drug Agency decreased from 11,194 to 9015 (Figure 1).

In terms of arrests made by the police under section 3(1) (Figure2) related to opiate and cannabis use, there was an increase from 41,363 arrests to 63,466 arrests between 2008 and 2010, whereas a decrease has been observed since 2010.

The decrease in the number of detected drug addicts can be attributed to the introduction of needle exchange programs and also the availability of medical treatments by private general practitioners (GPs). Prior to the implementation of these programs, GPs were not allowed to treat drug addicts but were required to report drug addicts to the government, which mandated them to undergo compulsory institutional rehabilitation. Currently, private GPs who treat drug addicts are not required to inform the government; hence, we think that this is the reason for the lower number of drug addicts being detected in the country.

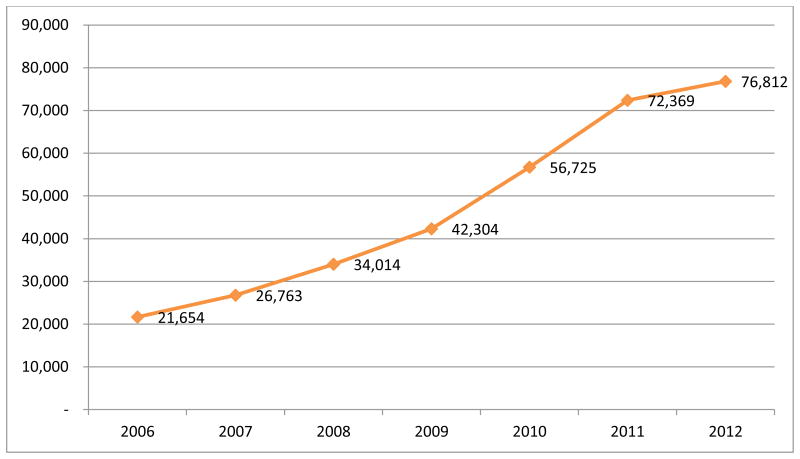

Figure 3 shows arrests made under section 15 (1) of the Dangerous Drug Act of 1952 This act applies when an individual tests positive for using dangerous drugs and does not need to be medically certified as being drug dependent. In Malaysia, mostly ATS and ketamine users are charged under this section. There was almost a four-fold increase in the number of ATS and ketamine users detected from 2006 to 2012 (21,653 to 76,812).

Figure 3. Arrest under section 15(1)(a) Dangerous Drug Act 1952 (DDA) related to party drugs use from 2006 – 2012.

Source: Royal Malaysia Police (2013)

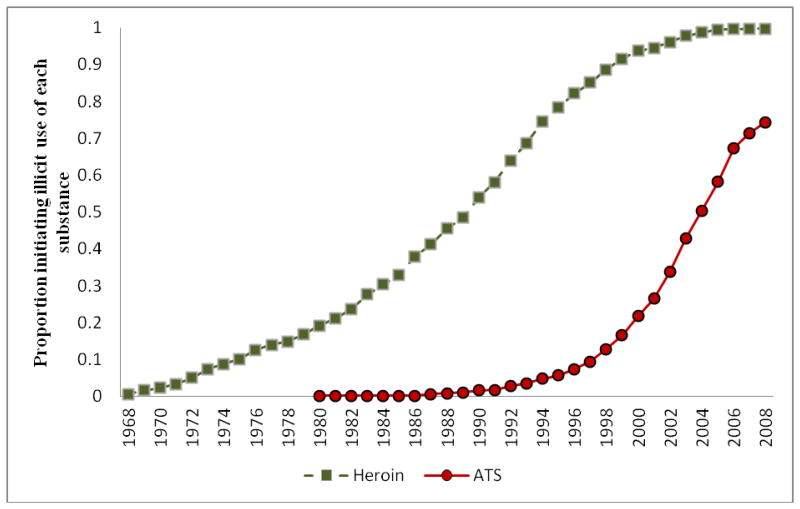

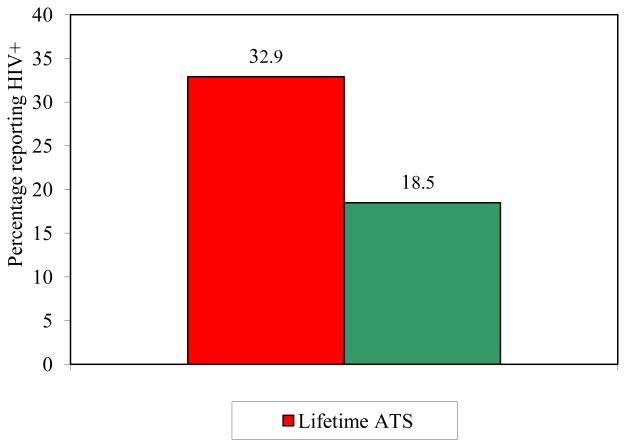

This increase, which was documented by the national database, is also supported by surveys conducted by the authors as shown in Figure 4's timelines of initiation of illicit use of heroin and ATS in a sample of 732 not-in-treatment active opiate injectors in Kuala Lumpur, Johor Bahru, and Penang, Malaysia [11]. Figure 4 illustrates that the cumulative proportion of individuals initiating heroin use increased steadily beginning in the late 1960s. ATS use was negligible until 1987 (only one person reported initiation of ATS before 1987). The number of participants initiating ATS use increased slowly over the next several years, before rising rapidly after 1997. By 2008, 75% of the participants had initiated ATS use. In this sample, we also observed a strong association between lifetime ATS use and HIV infection rates (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Onset of ATS abuse in Malaysia (Chawarski et al., 2012).

Figure 5. Lifetime ATS use and HIV infection rates.

3.2 Drug seizures

Over the last 2 years, a significant increase in heroin seizures has been observed. Between 2004 and 2010, the yearly seizures for heroin ranged between 156 to 270 kg. However, in 2010 and 2011, heroin seizures showed an increase of 445kg and 410.02 kg, respectively. This is in contrast to the number of drug users detected and arrested for the same period of time (2010 and 2011), when a decreasing trend was observed.

With regard to ATS (yaba, syabu, and ecstasy), there has been a seizure of between 600 to 1000kg of syabu yearly from 2009 to 2012. Similar to heroin, increased seizures for Yaba have also been observed over the last 2 years. A significant increase has also been recorded for the seizures of ecstasy pills—from 47,761 pills in 2011 to 634,573 pills in 2012.

Ketamine seizures have dropped from 378 kg seized in 2010 to 106 kg in 2011 and 118.07 in 2012. Similarly, cannabis seizures also recorded a downward trend from 2010. Table 1 shows the trend of seizures of drugs in Malaysia from 2004 to 2012.

Table 1. Seizures of drugs in Malaysia from 2004 to 2012.

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heroin (kg) | 183 | 221 | 156 | 243 | 270 | 217 | 234 | 445 | 410.02 |

| Cannabis (kg) | 1,031 | 920 | 2,216 | 705 | 751 | 1,734 | 953 | 796 | 751.80 |

| Syabu (kg) | 63 | 37 | 139 | 65 | 355 | 1,093 | 760 | 830 | 608.67 |

| Ketamine (kg) | 11 | 396 | 190 | 178 | 241 | 378 | 268 | 106 | 118.07 |

| Yaba (pil) | 92,549 | 108,430 | 242,732 | 121,629 | 197,343 | 107,573 | 107,963 | 364,87 | 521,384 |

| Ecstasy (pil) | 103,895 | 114,887 | 252,231 | 151,211 | 80,800 | 67,775 | 60,713 | 47,761 | 634,573 |

Source: Royal Malaysia Police (2013)

3.3 HIV/AIDS situation

The cumulative number of reported HIV infections since 1986 is 94,841. Table 2 provides an overview of the HIV epidemic in Malaysia. In the 1990s, about 70% to 80% of HIV infections in the country were attributed to injecting drug users (IDUs). However, in 2011, HIV infection rates among IDUs declined to 38.7%. This is due to the implementation of harm reduction programs in 2005. These rates are projected to drop to 10% in 2015 [12]. In 2011, sexual transmission superseded injecting drug use as the main factor for the epidemic, with a ratio of 6 sexual transmissions for every 4 injecting drug use transmissions reported. HIV in the country also mainly affects males, who make up 90% of cumulative HIV cases, and the majority of these individuals are IDUs. However, a growing number of females are being infected with HIV. The trend of the male-to-female ratio of HIV infection shifted from 1:99 in 1990 to 1:10 in 2000 and 1:4 in 2011 [12].

Table 2. Overview of the HIV epidemic in Malaysia 2011.

| Indicator | Number/percentage |

|---|---|

| Cumulative no. of reported HIV infections since first detection in 1986 | 94,841 |

| Cumulative no. of reported AIDS since 1986 | 17,686 |

| Cumulative no. of reported deaths related to HIV/AIDS since 1986 | 14,986 |

| Estimated no. PLHIV [EPP 2011] | 81,000 |

| New HIV infections detected in 2011 | 3,479 |

| Notification rate of HIV (per 100,000) in 2011 | 12.18 |

| Women reported with HIV in 2011 | 735 |

| Cumulative no. of women reported with HIV as of December 2011 | 9,494 |

| Children aged below 13 with HIV in 2011 | 65 |

| Cumulative no. of children under 13 with HIV as of December 2011 | 974 |

| Estimated no. PLHIV eligible for treatment [EPP 2011] | 37,306 |

| No. PLHIV receiving ART (surveillance data) as of December 2011 | 14,002 |

Source: Ministry of Health Malaysia (2012)

There are 37,306 people living with HIV (PLHIV) who are eligible for treatment, and 14,002 PLHIV were receiving antiretroviral treatment (ART) in 2011. Malaysia provides first-line ART for free, and ART treatment is also made available for incarcerated populations. The second-line protease inhibitor (PI)-based regimens regime is also subsidized by the government [12].

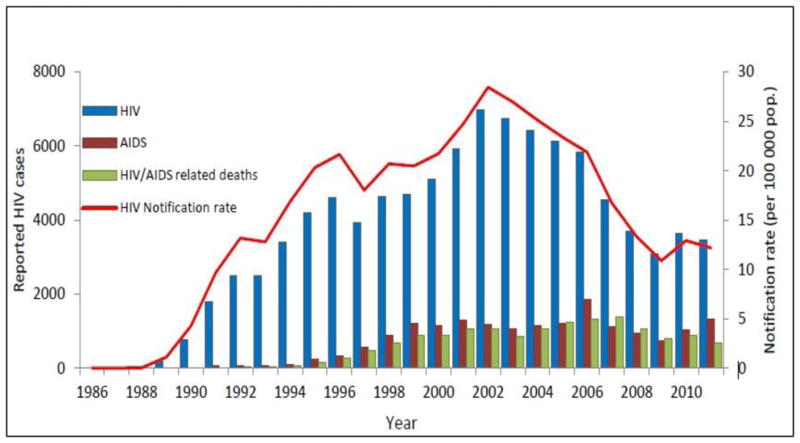

The annual reported number of new HIV infections declined from 6,978 cases in 2002 to 3,479 in 2011. The notification rate of HIV (new and recurrent episodes notified to Malaysian Ministry of Health for a given year, expressed per 100 000 population) also decreased from 28.4 in 2002 to 23.4 in 2005, and to 12.2 cases per 100,000 population in 2011 (Figure 6). Providing free first-line and affordable second-line ART has also resulted in a decline of AIDS-related deaths. In 2011, 14,002 PLHIV were in treatment, which is 37.5% of the estimated PLHIV eligible for ART treatment.

Figure 6. Reported HIV and AIDS related deaths, Malaysia 2006 - 2011.

Source: Ministry of Health Malaysia (2012) [16]

We would like to caution that while declining rates are encouraging, the introduction of harm reduction programs has also resulted in fewer drug users being tested for HIV. Prior to the implementation of harm reduction programs, all detected drug users who were mandated to undergo mandatory institutional rehabilitation were tested upon entry to these centers.

4. Discussion

The numbers of heroin addicts detected (Figure 1) and opiate users arrested (Figure 2) decreased in 2011 and 2012, while the seizures of heroin in the country for the same period almost doubled. We think that the decreasing trend observed in Figures 1 and 2 is due to the introduction of medical treatments and harm reduction approaches for drug users.

We are, however, unable to say for certain why there has been an increase in heroin seizures in the country. The plausible reason is an obvious increase in demand for heroin in the country. As we explained above, the lower number of drug users detected may not necessarily reflect a decreasing trend of drug users in the country. The data provided for heroin seizures in the country is for heroin No. 3, which is for local consumption. Only heroin No. 4 is exported, so the argument that this seized heroin is heading for the international drug market is not plausible. The second potential reason is that Malaysia is often regarded as a transit country for the trafficking of drugs to Australia.

The number of drug users arrested for ATS and ketamine has increased significantly since 2006. Seizures for ATS have also increased, whereas ketamine seizures have decreased over the last 2 years. Amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) abuse and opioid dependence are highly prevalent, frequently co-occur, and are the major drivers of the HIV and other major public health problems in Malaysia and throughout Asia. ATS abuse by methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) patients may also undermine the effectiveness of MMT.

These new trends, particularly in co-occurrence with opiate dependence, underscore the need to develop and implement effective treatments for ATS, co-occurring opiate and ATS use, and polysubstance abuse disorders. The importance of using a medical model for treatment of drug users needs to be emphasized. This should include using medications and psychosocial interventions. Once individuals enter into drug treatment programs, there also is a higher likelihood that those who are HIV-positive will be able to enroll in HIV treatment. While we have shown from our survey data that lifetime ATS use is linked to increased HIV infection rates, more studies and more behavioral data is needed to understand the link between ATS use and HIV infection in local settings. Colfax et al. 2010 [13], and Degenhardt, 2010 [14], have shown that ATS use might contribute to HIV infection through a number of behavioral and biological pathways—increased energy and sexual activity, impaired judgment leading to unsafe sexual practices, increased injecting drug use and sharing of equipment, and more impulse-sharing in high risk situations.

The introduction of NSEP is commendable, considering the barriers that the government and NGOs had to overcome in 2006 to implement the nationwide program [15]. However, after several years of implementation, the proportions of clients being referred to Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) and MMT are low, with only approximately 10% of NSEP clients referred to VCT and about 4% referred to and entering MMT [8]. The low numbers of NSEP clients being tested for HIV underscores our caution in interpreting the decline of HIV infections among drug users and the importance of focusing on providing education, prevention, treatment, and outreach to populations of not-in-treatment current drug users.

As Malaysia has, only over the last several years, allowed private medical practitioners to treat drug users in the country, there is a need to provide training to more physicians, especially trainings on how to dispense medication in a proper way for GPs. Similarly, there is a need to provide counselors with high quality counseling training.

References

- 1.Malaysia population clock. [Accessed May 8, 2013];Country Meters. Available at http://countrymeters.info/en/Malaysia/

- 2.Kamarudin AR. The misuse of drugs in Malaysia: past and present. Jurnal Antidadah Malaysia. 2007;1:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKetin R, Kozel N, Douglas J, et al. The rise of methamphetamine in Southeast and East Asia. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:220–228. doi: 10.1080/09595230801923710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) UNODC world drug report. United Nations publication, sales No. E.10.XI.13.2010. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) UNODC world drug report. United Nations publication, sales No. E.11.XI.10.2011. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vicknasingam B, Narayanan S, Navaratnam V. The relative risk of HIV infection among IDUs not in treatment in Malaysia. AIDS Care. 2009;21:984–991. doi: 10.1080/09540120802657530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nazar M, Ahlam Z. Current trends of drug abuse in Malaysia: its implications for the HIV problems. Paper presented at the WHO Workshop on drug abuse and HIV AIDS; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 3 December; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Global AIDS Response. Country progress report Malaysia. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamarulzaman A. Impact of HIV prevention programs on drug users in Malaysia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;S2:17–19. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bbc9af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid G, Kamarulzaman A, Sran SK. Malaysia and harm reduction: the challenges and responses. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chawarski MC, Vicknasingam B, Mazlan M, et al. Lifetime ATS use and increased HIV risk among not-in-treatment opiate injectors in Malaysia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124:177–180. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.IAS. Fact sheet: HIV and AIDS in Malaysia. 7th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention; 30 June – 3 July; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colfax G, Santos GM, Chu P, et al. Amphetamine-group substances and HIV. Lancet. 2010;376:458–474. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60753-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Degenhardt L, Mathers B, Guarinieri M, et al. Reference group to the United Nations on HIV and injecting drug use meth/amphetamine use and associated HIV: implications for global policy and public health. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21:347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narayanan S, Vicknasingam B, Robson NM. The transition to harm reduction: understanding the role of non-governmental organisations in Malaysia. Int J Drug Policy. 2011;22:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.01.002. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Health Malaysia. HIV/STI Section, Disease Control Division. 2012 [Google Scholar]