Abstract

Nitrite anion has been demonstrated to be a prodrug of nitric oxide (NO) with positive effects on tissue ischemia/reperfusion injury, cytoprotection, and vasodilation. However, effects of nitrite anion therapy for ischemic tissue vascular remodeling during diabetes remain unknown. We examined whether sodium nitrite therapy altered ischemic revascularization in BKS-Leprdb/db mice subjected to permanent unilateral femoral artery ligation. Sodium nitrite therapy completely restored ischemic hind limb blood flow compared with nitrate or PBS therapy. Importantly, delayed nitrite therapy 5 days after ischemia restored ischemic limb blood flow in aged diabetic mice. Restoration of blood flow was associated with increases in ischemic tissue angiogenesis activity and cell proliferation. Moreover, nitrite but not nitrate therapy significantly prevented ischemia-mediated tissue necrosis in aged mice. Nitrite therapy significantly increased ischemic tissue vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) protein expression that was essential for nitrite-mediated reperfusion of ischemic hind limbs. Nitrite significantly increased ischemic tissue NO bioavailability along with concomitant reduction of superoxide formation. Lastly, nitrite treatment also significantly stimulated hypoxic endothelial cell proliferation and migration in the presence of high glucose in an NO/VEGF-dependent manner. These results demonstrate that nitrite therapy effectively stimulates ischemic tissue vascular remodeling in the setting of metabolic dysfunction that may be clinically useful.

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a chronic arterial occlusive disorder of the lower extremities due to atherosclerosis and is characterized by high cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (1). Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) frequently present with PAD, and the incidence continues to increase due to advancing age and DM diagnosis (2). Type 2 DM enhances the pathology of atherosclerosis, including endothelial dysfunction, glycosylation of extracellular matrix proteins, and vascular denervation. Cellular and metabolic dysfunction associated with atherosclerosis further contributes to impaired ischemic vascular remodeling and collateral formation due to vascular damage (3). Moreover, diabetic PAD often progresses to critical limb ischemia, a common cause of nontraumatic amputation (2). Therapeutic angiogenesis leading to tissue cytoprotection may be one of the best options for this population of patients (4); however, effective approaches to accomplish this remain unrealized. Numerous mediators, including growth factors, transcription factors, and signaling molecules, have been reported to augment chronic ischemia-induced angiogenesis in animal models (5). However, clinical trials targeting these pathways for PAD/critical limb ischemia have been disappointing, possibly due to secondary complications found in DM patients that were not present in preclinical models.

It is now clear that vascular remodeling involving angiogenesis, arteriogenesis, and vasculogenesis are all significantly impaired during diabetic tissue ischemia (6–9). Angiogenesis is also delayed in aged subjects as well as those presenting with hypercholesterolemia (9,10). To realize successful therapeutic revascularization approaches in clinical settings, it is imperative that disease models manifesting these complicating factors be employed to identify new, effective therapeutic approaches.

Nitric oxide (NO) has been identified as a key regulator of vascular health and remodeling responses; however, NO production is impaired in disease models such as diabetes and naturally diminishes with age, leading to endothelial cell dysfunction (11,12). Moreover, nitrite (the oxidation product of NO) levels are reduced in the plasma of patients with diabetic vascular disease and are associated with poor arterial function (13). Considering that NO plays a large role in angiogenesis and arteriogenesis and that it is a very reactive and short-lived molecule, a therapy to augment NO levels in the form of a prodrug format may be beneficial for diabetic ischemic vascular remodeling responses. Previous work from our laboratory revealed that sodium nitrite stimulates ischemic vascular remodeling in healthy mice; however, its utility in diabetic animals is unknown (14). In this study, we report the effect of sodium nitrite therapy on ischemic vascular remodeling with confounding conditions of metabolic dysfunction and age.

Research Design and Methods

Reagents

Ki67 antibody was obtained from Abcam. CD31 antibody was obtained from BD Biosciences. Vectashield plus DAPI was obtained from Vector Laboratories. All secondary fluorophore-conjugated antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) ELISA kits were purchased from Bio-Rad, and BrdU reagents were purchased from Calbiochem; both assays were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Febuxostat was purchased from Takeda Pharmaceuticals America, Inc.

Animals and Experimental Procedures

Three-month-old and nine-month-old BKS-Leprdb/db male mice were used for experiments in this study. Mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, housed at the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, an internationally accredited Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center–Shreveport animal resource facility, and maintained in accordance with the National Research Council’s Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animal studies were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

Mouse Hind Limb Ischemia Model and Treatment Profiles

Chronic hind limb ischemia due to unilateral femoral artery ligation was induced in BKS-Leprdb/db male mice as we have previously reported (15,16). Mice were anesthetized with inhaled isofluorane, and aseptic surgery was performed by a linear incision in the left groin, then the left common femoral artery ligated distal to the profunda femoris artery was cut and excised to obtain severe hind limb ischemia. Immediate pallor was observed in the distal hind limb following ligation of the artery and vein using 5–0 silk. Following surgery, the mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups and treated by an independent researcher for 3 weeks. Groups included control (PBS), nitrite (sodium nitrite; 165 μg/kg), or nitrate (sodium nitrate; 165 μg/kg). Nitrite and nitrate were administered intraperitoneally twice daily until the end of the study.

Blood Chemistry

Blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus two times during the course of the study: prior to beginning therapy and again at the end of the study. Collected blood was sent to the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center clinical laboratory for blood glucose, cholesterol, and triglyceride measurements. Body weights were also recorded at these time points.

Laser Doppler Measurements

Laser Doppler blood flows were measured using a Vasamedics Laserflow BPM2 device as previously reported in the gastrocnemius preligation, postligation, and on days 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, and 21 postligation (14,16). Blood vessels visible through the skin were avoided to limit signal noise. Measurements were recorded as milliliter of blood flow per 100 g of tissue per minute. Percent blood flows were calculated as:

|

where a = ischemic limb average flow and b = nonischemic limb average flow.

Pedal Necrosis Assay

Gross examination of ischemic and nonischemic feet was scored based on the following criteria (by number): 1, no visible necrosis; 2, minor necrosis of nail bed; 3, necrosis affecting all digits; 4, necrosis involving loss of at least one digit; and 5, severe necrosis, loss of two or more digits or significant foot necrosis.

Vascular Density Measurement

Vascular density measurements were performed as we have previously reported (14,16). Gastrocnemius muscles from ischemic and nonischemic hind limbs were removed, dissected, and embedded in OCT freezing medium. Frozen tissue blocks were cut into 5-µm sections and prepared for immunohistochemistry. A primary antibody against platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 was added at 37°C for 1 h followed with a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody added at room temperature for 1 h. Slides were washed and mounted with coverslips using Vectashield DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Images were captured using a Nikon TE-2000 epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at ×200 original magnification for CD31 and DAPI staining. Simple PCI software version 6.0 (Hamamatsu Inc., Sewickly, PA) was used to measure CD31 and DAPI area staining (angiogenesis index). Tissue angiogenic index was determined as the ratio between CD31-positive areas and DAPI-positive regions.

Cellular Proliferation Measurement

Immunofluorescent staining of the cell proliferation protein Ki67 was used to identify proliferating cells (anti-Ki67) from other cells (DAPI staining) as previously reported (14,16). Images acquisition was performed as described above. Cellular proliferation index was determined as the ratio between regions positive for Ki67 and DAPI-positive areas (proliferation index).

Blood and Tissue Total Nitrite Measurement

Total NO bioavailability (NOx) levels were measured using a chemiluminescent NO analyzer (GE Healthcare) as we have previously published (14,16). Tissue and blood were then added to a 500-µl solution containing 800 mmol/L potassium ferricyanide, 17.6 mmol/L N-ethylmaleimide, and 6% Nonidet P-40. Tissue was homogenized and lysates snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Measurement of Growth Factor Expression with Nitrite Treatment

VEGF protein levels were measured from gastrocnemius tissues using an ELISA kit from R&D Biosciences. Briefly, PBS- or nitrite-treated mice were killed at days 7, 11, and 15, and gastrocnemius muscle tissues were harvested.

Measurement of Superoxide-Specific 2-OH-Ethidium

Tissue superoxide production was measured using the hydroethidine reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method, as we have previously reported (15). On days 7 and 15 postischemia, mice were injected i.p. with 300 µl of hydroethidine (1 µg/µL). One hour after injection, blood was taken from the retro-orbital sinus and the animals were killed to remove the gastrocnemius muscle tissue from both hind limbs. Blood was centrifuged for 5 min at 5,000 rpm to isolate plasma. Protein was precipitated from the muscle tissue using acidified methanol and 2-OH-ethidium (2-OH-E)+ enriched using a microcolumn preparation of Dowex 50WX-8 cation exchange resin and eluted with 10 N HCl. 2-OH-E+ product was measured using fluorescence detection (excitation 490 nm; emission 567 nm) with a Shimadzu HPLC system (Shimadzu Corporation). 2-OH-E+concentration was normalized to total protein and reported as picomoles per milligram of protein for tissue and nanomole concentrations for plasma.

Bromodeoxyuridine Endothelial Cell Proliferation Assay

MS1 cells were incubated in 96-well plates in alfa-minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 21% O2, for 4 h and then either maintained at these culture conditions or moved into hypoxic chamber at 37°C, 1% O2 and 5% CO2 for 20 h. Endothelial cells were exposed to either mannitol (25 mmol/L) osmotic control or high glucose (30 mmol/L) during the incubation period. Sodium nitrite (10 μmol/L) was then added to certain wells and incubated under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 4 h. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation over the 4-h period was measured using a commercial ELISA kit.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls posttest. A P < 0.05 value was used to indicate significance. Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.0 software. The n values per experimental cohorts are reported in the figure legends.

Results

Nitrite Therapy Has No Effect on Metabolic Parameters

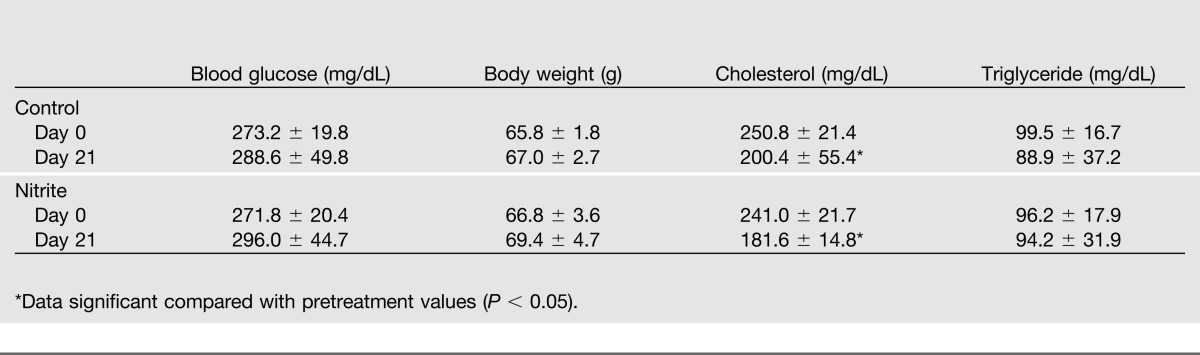

Table 1 reports that sodium nitrite therapy did not significantly alter blood glucose or body weight compared with control PBS therapy in db/db diabetic mice. Plasma triglyceride levels also remained unchanged; however, total cholesterol levels were reduced at the end of the treatment regimen for both PBS- and nitrite-treated groups. These data indicate that nitrite therapy itself did not alter metabolic function of db/db diabetic mice.

Table 1.

Effects of sodium nitrite therapy on blood glucose, body weight, cholesterol, and triglycerides compared with control PBS therapy in db/db diabetic mice

Nitrite Therapy Restores Blood Flow and Promotes Health in Ischemic Limbs

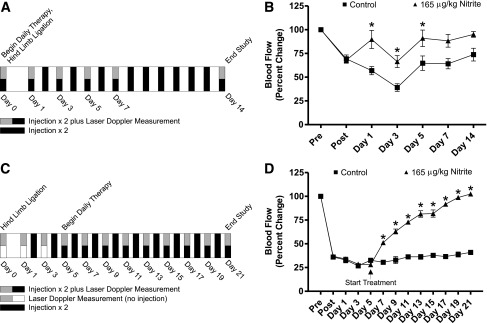

Figure 1A shows the experimental model regimen using young mice (3 months old) to evaluate the effect of nitrite therapy on hind limb ischemia. Femoral artery ligation was performed as described in the Research Design And Methods and either PBS or nitrite therapy began after the animals had recovered from surgery. Light gray blocks depict days that laser Doppler was performed and nitrite treatment was administered twice daily for the duration of the study. Figure 1B illustrates ischemic hind limb blood flow changes using young db/db diabetic mice. Nitrite therapy (165 μg/kg) significantly prevented a loss of hind limb blood flow compared with PBS treatment. Figure 1C shows the experimental design for delayed nitrite therapy studies using 9-month-old db/db mice, which were used for the remainder of experiments described in the study. Nitrite therapy was begun on day 5 postligation to emulate the fact that clinical presentation of peripheral vascular disease typically occurs after the onset of tissue ischemia. The gray blocks depict days that laser Doppler was performed, whereas black bars indicate nitrite administration regimens. Ligation of 9-month-old db/db mice resulted in a more severe loss of hind limb blood flow (Fig. 1D). Nonetheless, delayed nitrite therapy (165 μg/kg) stimulated a significant restoration of blood flow just 2 days after beginning therapy that progressively restored ischemic hind limb blood flow to 100% by day 21 postligation (day 16 after beginning treatment). These data demonstrate that nitrite therapy is effective in both immediate and delayed therapeutic modalities.

Figure 1.

Sodium nitrite therapy increases diabetic ischemic hind limb blood flow. A: Panel shows the protocol schematic for acute sodium nitrite therapy in 3-month-old diabetic mice. B: Panel reports hind limb blood flow data following induction of ischemia and nitrite treatment protocol illustrated in panel A. C: Panel illustrates the protocol schematic for delayed sodium nitrite therapy in 9-month-old diabetic mice. D: Panel represents hind limb blood flow data following induction of ischemia and nitrite treatment protocol illustrated in panel C. n = 6/cohort. *P < 0.05.

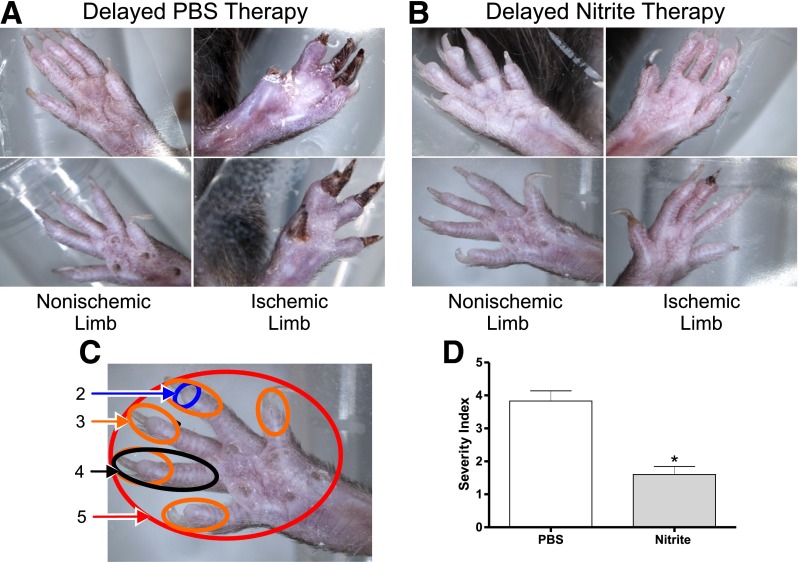

Importantly, pedal necrosis was evident in aged diabetic mice due to unilateral femoral artery ligation and subsequent limb ischemia. Figure 2 shows representative images of tissue necrosis between delayed PBS and nitrite therapy groups. Figure 2A illustrates the effect of PBS control therapy on ischemic and nonischemic limb foot necrosis. Figure 2B shows the effect of delayed nitrite therapy (165 μg/kg) on ischemic and nonischemic limb foot necrosis. A pedal necrosis index (1–5: none to severe) was established in order to objectively evaluate for differences in tissue necrosis between PBS and nitrite therapy as shown in Fig. 2C. Figure 2D demonstrates that pedal necrosis was significantly prevented in delayed nitrite-treated animals compared with delayed PBS therapy. Together, data in Figs. 1 and 2 clearly demonstrate that sodium nitrite therapy is effective in restoring blood flow and preserving tissue viability in ischemic limbs of diabetic mice.

Figure 2.

Nitrite therapy prevents diabetic ischemic tissue necrosis. A: The panels illustrate representative limb necrosis in both ischemic and corresponding nonischemic limbs from delayed PBS therapy. The darkened toes of the ischemic limbs are indicative of necrosis. B: The delayed nitrite therapy panels illustrate ischemic limbs and the corresponding nonischemic limbs. C: The panel provides a visual scoring system for the pedal necrosis measurement described in the research design and methods. D: The panel is a graphical representation of necrosis severity index of diabetic hind limbs from PBS and sodium nitrite–treated cohorts. n = 6/cohort. *P < 0.05.

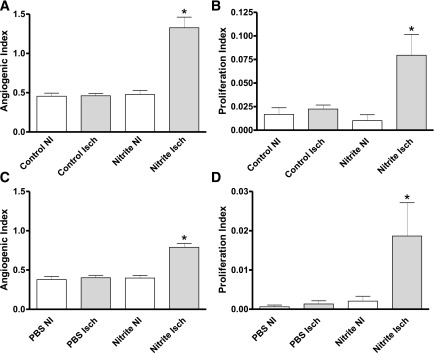

Nitrite Therapy Stimulates Ischemic Tissue Angiogenesis and Cell Proliferation

Revascularization in patients with diabetes complicated by PAD could mean the difference between amputation and the restoration of healthy limb function. Our gross examination of the limbs of treated animals demonstrated that sodium nitrite therapy was successful in restoring ischemic tissue blood flow and preventing ischemic tissue necrosis. We next performed immunohistochemical measurement of ischemic tissue vascular density in the gastrocnemius muscles of treated animals as we have previously reported (15,16). Figure 3A shows that nitrite therapy significantly enhances CD31/DAPI tissue vascular density ratios 14 days following ischemia in the young diabetic mouse model. This increase in vascular density is concomitant with an increase in cellular proliferation (Ki67/DAPI ratio) (Fig. 3B). Figure 3C further illustrates that delayed nitrite therapy in aged diabetic mice also enhances vascular density 21 days following ischemia, which was also associated with a significant increase in ischemic tissue cellular proliferation (Fig. 3D). These data demonstrate that enhanced ischemic tissue blood flow of nitrite-treated animals and the decrease in visible necrosis is associated with enhanced vascular density and cellular proliferation.

Figure 3.

Quantitative measurement of sodium nitrite–mediated vascular density and cell proliferation. A: The panel reports quantitative measurement of the angiogenic index (CD31/DAPI ratio) from gastrocnemius muscle of ischemic (Isch) and nonischemic (NI) control (PBS)- and sodium nitrite (Nitrite)–treated diabetic mice from Fig. 1A, protocol schematic. B: The panel shows the quantitative measurement of the proliferation index (Ki67/DAPI ratio) from gastrocnemius muscle of Isch and NI control (PBS)- and sodium nitrite (Nitrite)–treated diabetic mice from Fig. 1A, protocol schematic. C: The panel reports the angiogenic index (CD31/DAPI ratio) from gastrocnemius muscle of Isch and NI control (PBS)- and sodium nitrite (Nitrite)–treated diabetic mice from Fig. 1C, protocol schematic. D: The panel illustrates the proliferation index (Ki67/DAPI ratio) from gastrocnemius muscle of Isch and NI control (PBS)- and sodium nitrite (Nitrite)–treated diabetic mice from Fig. 1C, protocol schematic. n = 10/cohort. *P < 0.05.

To confirm the nitrite-dependent endothelial cell proliferation effects observed in Fig. 3 could occur with endothelial cells, in vitro BrdU cell proliferation assays were performed under both normoxic (21% oxygen) and hypoxic (1% oxygen) conditions with or without high glucose (30 mmol/L). Supplementary Fig. 1A illustrates endothelial cell proliferation under normoxic conditions in response to control, mannitol (25 mmol/L) osmotic control, high glucose, 10 μmol/L sodium nitrite, or sodium nitrite plus high glucose. High glucose or nitrite treatments alone blunted basal endothelial cell proliferation; however, the combination of hyperglycemia plus nitrite stimulated a small but significant increase in endothelial cell proliferation. Supplementary Fig. 1B shows the effect of the various treatment conditions on endothelial cell proliferation under hypoxic conditions. Hypoxia significantly increased basal endothelial cell proliferation compared with normoxia, which was blunted by high glucose. However, nitrite treatment significantly increased endothelial cell proliferation, which was not prevented by high glucose conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1C and D). Likewise, nitrite therapy also significantly increased endothelial cell migration in the hypoxic condition, which was not prevented by high glucose (Supplementary Fig. 1E and F). Importantly, use of the NO scavenger carboxy-2-phenyl-4,4,5,5,-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl 3-oxide or VEGF164 aptamer inhibited nitrite-mediated endothelial cell proliferation and migration. These data demonstrate that nitrite therapy can significantly increase hypoxic endothelial cell proliferation under hyperglycemic conditions.

Reports have suggested that nitrate anion (a one-electron oxidation product of nitrite) could increase plasma nitrite levels through the enterosalivary pathway, thus serving as another modality to modulate plasma and tissue nitrite levels (17). Therefore, we compared nitrite (165 μg/kg) versus nitrate (165 μg/kg) therapy in aged diabetic animals beginning immediately after femoral artery ligation. Supplementary Fig. 2 illustrates that sodium nitrate therapy was unable to significantly restore ischemic limb blood flow in diabetic animals (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Additionally, nitrate therapy was unable to confer protection against pedal necrosis or stimulate increases in ischemic vascular density or cellular proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 2B–D). These data show that only nitrite therapy is effective at restoring diabetic ischemic tissue perfusion and viability versus nitrate therapy.

Nitrite Therapy Augments Ischemic Limb Blood Flow in a Xanthine Oxidase–Dependent Manner

Nitrite reduction back to NO can occur through various mechanisms including acidic disproportionation, heme-dependent pathways, and xanthine oxidoreductase (XO) activity (17). Importantly, oxidative stress involving XO expression and activity has been implicated during diabetes (18,19). Experiments were performed using the XO inhibitor febuxostat in conjunction with nitrite therapy. Figure 4A shows that XO inhibition prevented nitrite-mediated restoration of ischemic limb reperfusion. Additionally, Fig. 4B and C illustrate that XO inhibition also prevented nitrite-mediated ischemic tissue angiogenesis and cellular proliferation. Together, these data demonstrate that XO activity is important for nitrite beneficial effects on ischemic tissue protection in aged db/db diabetic animals.

Figure 4.

XO inhibition blunts nitrite-dependent restoration of diabetic ischemic tissue perfusion. A: The panel reports the effect of febuxostat treatment on nitrite-dependent ischemic hind limb blood flow over time. B: The panel shows the effect of febuxostat (Febux) on sodium nitrite–mediated angiogenic index of ischemic gastrocnemius tissue. C: The panel illustrates the effect of Febux on sodium nitrite–dependent proliferation index of ischemic gastrocnemius tissue. n = 10/cohort. *P < 0.05 vs. postligation or PBS treatments, #P < 0.05 vs. nitrite therapy.

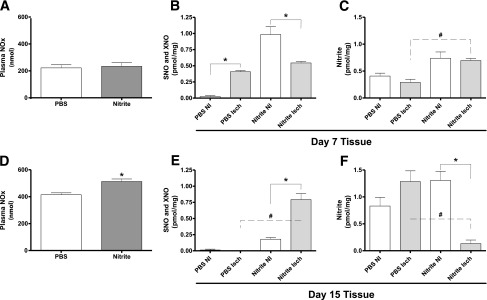

Nitrite Therapy Augments NOx

Having observed significant results in the delayed nitrite therapy of aged diabetic mice, we next examined the effect of sodium nitrite therapy on NOx in diabetic plasma and tissue. Figure 5A illustrates that steady-state plasma total NOx levels were unchanged in the nitrite-treated group at day 7 (2 days after beginning therapy). However, Fig. 5B shows that nitrosothiol and nitrosoheme (SNO/XNO) levels were enhanced in nonischemic limb of the nitrite-treated animal at day 7, supporting previous reports of endocrine nitrite/NO pathways (16,20). Our previous studies found that nitrite production from nonischemic tissue significantly effects distal ischemic tissue function and revascularization in the same animal (16,20). In our present study, we have found that nitrite levels increased in nonischemic tissue (right limb) during nitrite therapy, suggesting a possible repletion of nonischemic tissue nitrite endocrine function as revealed in our previous studies. Importantly, Fig. 5C shows a significant increase in ischemic tissue nitrite levels compared with PBS therapy at day 7. NOx was also examined at day 15 (10 days after beginning nitrite therapy). Figure 5D shows a significant increase in plasma NOx at day 15. Tissue SNO/XNO levels were markedly depleted in the PBS treatment group, whereas nitrite therapy significantly elevated SNO/XNO levels in ischemic and nonischemic limb tissue (Fig. 5E). Interestingly, tissue nitrite levels were significantly reduced in ischemic limbs of nitrite-treated animals but not PBS treatment. These data clearly reveal that nitrite therapy progressively modulates NO metabolism, stimulating an early increase in ischemic tissue nitrite levels that is subsequently followed by later increases in plasma total NO levels and ischemic tissue SNO/XNO levels.

Figure 5.

Plasma and tissue NO metabolite levels during sodium nitrite therapy. A: The panel shows the levels of NOx in plasma 7 days after ischemia and 2 days after beginning therapy. B: The panel shows the SNO and XNO tissue levels in ischemic (Isch)- and nonischemic (NI)-treated limbs 7 days after ischemia and 2 days after beginning therapy. C: The panel illustrates tissue nitrite levels 7 days after ischemia and 2 days after beginning therapy in Isch and NI limbs. D: The panel shows the levels of NOx in plasma 15 days after ischemia and 10 days after beginning therapy. E: The panel shows the SNO and XNO tissue levels in Isch- and NI-treated limbs 15 days after ischemia and 10 days after beginning therapy. F: The panel illustrates tissue nitrite levels 15 days after ischemia and 10 days after beginning therapy in Isch and NI limbs. n = 6/cohort. *P < 0.05 nitrite compared with PBS in panel D, *P < 0.05 NI compared with Isch, #P < 0.05 PBS Isch compared with Nitrite Isch for panels B, C, E, and F.

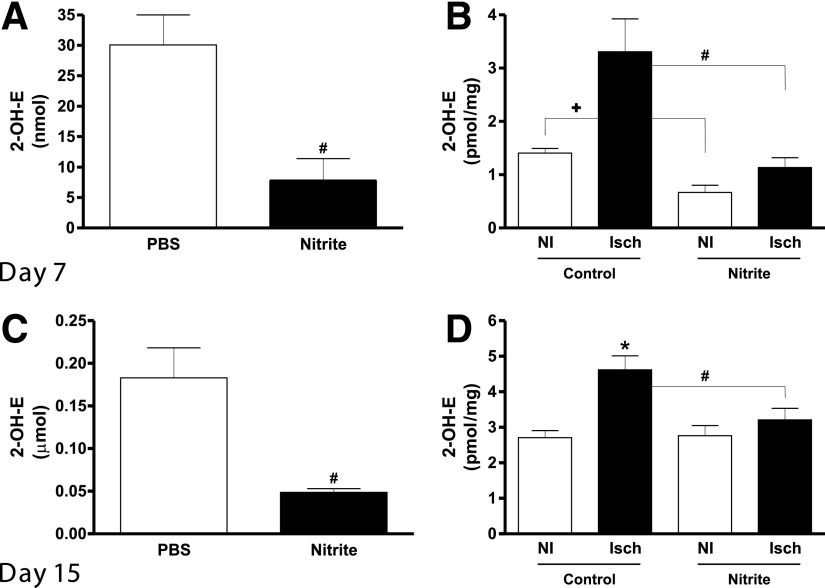

Nitrite Therapy Blunts Diabetic Oxidative Stress

Montenegro et al. (21) have reported that sodium nitrite therapy is capable of attenuating hypertension in a rat model by decreasing NADPH oxidase activity and subsequent oxidative stress. Moreover, diabetic endothelial dysfunction is predominantly due to increased reactive oxygen species and decreased NOx (22). Thus, we next examined whether delayed nitrite therapy in the aged diabetic db/db animals altered plasma and tissue superoxide levels. Figures 6A and B show that at day 7 postischemia (2 days after beginning nitrite therapy), plasma and tissue superoxide levels were significantly reduced in nitrite-treated animals compared with PBS therapy. Importantly, continued nitrite therapy at day 15 (10 days postnitrite therapy) still significantly decreased plasma and ischemic tissue superoxide levels (Fig. 6C and D). These data clearly demonstrate that sodium nitrite therapy quickly reduces diabetic tissue superoxide levels and oxidative stress that is maintained over time.

Figure 6.

Sodium nitrite therapy effects on diabetic plasma and tissue oxidative stress. A: The panel shows the levels of superoxide measured in plasma 7 days after ischemia and 2 days after beginning treatment. B: The panel shows values of superoxide measured in ischemic (Isch) and nonischemic (NI) gastrocnemius tissues taken from control and nitrite-treated animals 7-days postligation (2 days after beginning therapy). C: The panel shows the difference in superoxide levels in the plasma of animals 21-days postligation and 16 days after beginning therapy. D: The panel shows the levels of superoxide measured in Isch and NI gastrocnemius tissue taken from control and nitrite-treated animals 21 days after ligation and 16 days after beginning treatment. n = 4/cohort. #P < 0.05 decreased superoxide between nitrite vs. PBS treatment in panels A and C, +P < 0.05 NI limb comparisons between nitrite vs. PBS treatment in panel B, #P < 0.05 nitrite ischemic limb decreased compared with PBS ischemic limb in panels B and D, *P < 0.05 PBS Isch compared with PBS NI in panel D.

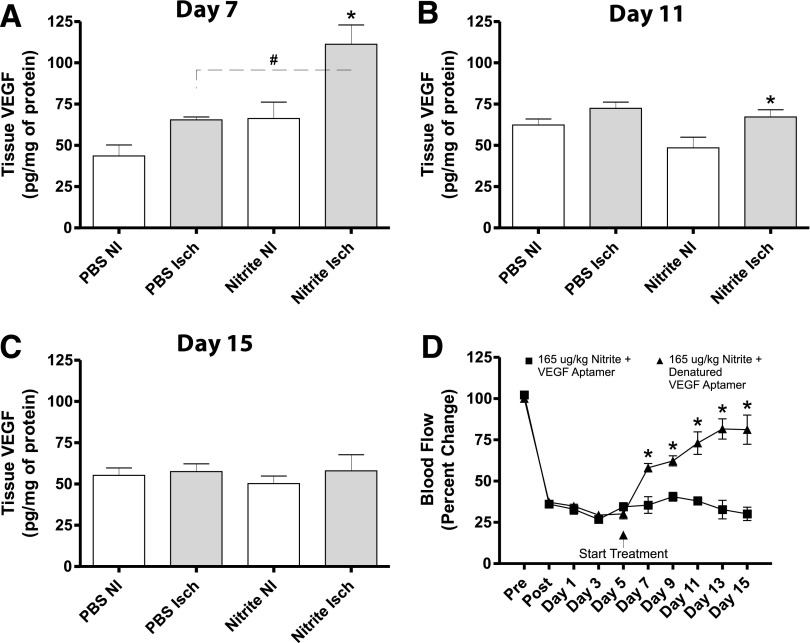

Nitrite Therapy Enhances VEGF Production in Ischemic Tissue

It is well-understood that VEGF production is stimulated in an NO-dependent manner (23). Therefore, we measured tissue VEGF levels at days 7, 11, and 15 following ligation corresponding to days 2, 6, and 10 following nitrite treatment to determine the involvement of ischemic tissue VEGF induction. VEGF protein expression was significantly increased in ischemic limbs of nitrite-treated animals compared with PBS treatment at day 7 (Fig. 7A). At day 11, VEGF levels had substantially dropped but were still significantly greater than nonischemic limb tissue of nitrite-treated mice (Fig. 7B). By day 15, tissue VEGF levels reached steady-state levels and were not significantly different among any treatment cohort (Fig. 7C). To determine the importance of nitrite-mediated ischemic tissue VEGF expression, we used the VEGF164 aptamer to selectively neutralize this isoform, as we have previously reported (24). Figure 7D shows that with nitrite therapy, the VEGF164 aptamer significantly abrogated nitrite restoration of ischemic hind limb blood flow previously noted compared with the heat-inactivated denatured VEGF164 aptamer. Our in vitro studies support our in vivo findings in which VEGF expression was increased in endothelial cells by nitrite therapy in high-glucose and hypoxic conditions, yet blunted by VEGF aptamer and/or carboxy-2-phenyl-4,4,5,5,-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl 3-oxide (NO inhibitor) (Supplementary Fig. 1A and B). These data demonstrate that induction of VEGF expression during nitrite therapy is important for the restoration of ischemic hind limb perfusion.

Figure 7.

Sodium nitrite therapy augments diabetic ischemic limb reperfusion in a VEGF-dependent manner. A: The panel represents tissue VEGF levels at day 7 following ligation (2 days after beginning treatments) between PBS vs. nitrite treatment cohorts. B: The panel illustrates tissue VEGF levels at day 11 following ligation (6 days after beginning treatment) between PBS vs. nitrite treatment cohorts. C: The panel represents day 15 following ligation (10 days after beginning treatments) between PBS vs. nitrite treatment cohorts. D: The panel reports hind limb blood flow of animals treated with sodium nitrite plus VEGF aptamer or sodium nitrite plus denatured VEGF aptamer. n = 5/cohort for panels A–C and n = 6/cohort for panel D. *P < 0.05 nonischemic (NI) vs. ischemic (Isch); #P < 0.05 PBS Isch vs. Nitrite Isch.

Discussion

Historically, PAD has been diagnosed in the elderly population; however, disease incidence in younger patients is increasing and associated with diabetes (25). Patients unresponsive to current treatment such as surgical revascularization are prime candidates for therapeutic angiogenesis. However, clinically beneficial strategies for medical revascularization remain unrealized due to the poorly understood complexities of this process in healthy and diseased tissues (26). These complexities involve stimulation of endothelial cell signal pathway activation, proliferation, extracellular matrix remodeling, and vessel maturation. Thus, there is clear need for new therapeutic approaches that can augment as many of these events as possible. NO has been reported to modulate all of these events, suggesting that NO-based therapy could be a unique and effective modality.

Decreased NOx during diabetes is well-known and contributes to cardiovascular and endothelial cell dysfunction. Moreover, loss of bioavailable NO also results in increased oxidative stress due to decreased NO-dependent free radical scavenging and antioxidant functions (27). We and others (14,17) have reported that nitrite anion acts as a novel prodrug, undergoing one-electron reduction back to NO under selective conditions such as tissue ischemia. Our results clearly demonstrate that sodium nitrite therapy significantly increases plasma and ischemic tissue NO metabolite accumulation over time in a dynamic fashion. In particular, nitrite therapy significantly increased ischemic tissue nitrite levels while also increasing nonischemic tissue S-SNO/XNO levels. These findings indicate that nitrite therapy works rapidly (within 2 days) to alleviate endogenous NO metabolite deficiency that occurs during diabetes. Sustained nitrite therapy over many days subsequently increased plasma NOx and increased ischemic tissue S-SNO/XNO levels preferentially in ischemic tissue with a concomitant reduction in free nitrite levels. This observation indicates that nitrite therapy works to increase both NO-mediated signaling and repletion of NO biochemical storage forms. Additionally, nitrite-mediated NO repletion was associated with significant inhibition of both plasma and ischemic tissue superoxide levels, unequivocally demonstrating that nitrite decreases diabetic oxidative stress. These findings are important given the clear imbalance between diabetic NOx and oxidative stress, highlighting the utility of nitrite-based therapy.

Ischemic revascularization is significantly impaired in diabetic subjects and in diabetic animal models due to hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia, aging, and oxidative stress due to loss of NO (27,28). Therefore, we used aged db/db diabetic mice that exhibit many key pathological conditions associated with metabolic dysfunction impairment of vascular remodeling. We found that sodium nitrite therapy stimulated ischemic vascular proliferation in young animals that immediately received therapy and older animals that received delayed therapy 5-days postischemia. The beneficial effect of nitrite therapy in both models is important, as it suggests that this modality might be beneficial for subjects across a spectrum of diabetes severity. Moreover, nitrite therapy significantly conveyed tissue cytoprotection and proliferation, as seen by prevention of ischemic necrosis and increased Ki67 staining. These observations are consistent with the fact that nitrite selectively upregulated ischemic tissue VEGF levels, which is known to be deficient and dysfunctional in db/db diabetic ischemic tissue (29–32). However, it is important to consider possible side effects of nitrite therapy such as diabetic retinopathy, in which VEGF expression is associated with retinopathy development (33). It is known that in diabetic conditions, VEGF expression is paradoxically increased in the retina but decreased in peripheral tissues due to hypoxia. However, diabetic endothelial NO synthase knockout mice readily develop retinopathy, suggesting that loss of NOx may be a contributing factor to retinopathy (34). Additional studies will be needed to see whether nitrite therapy alters pathological VEGF expression or function during diabetic retinopathy.

As mentioned previously, nitrite reduction back to NO can occur through various different mechanisms (17). Additionally, XO-dependent nitrite reduction to NO has been suggested to be biologically important, and our data confirm this (35). Our observation that XO inhibition by febuxostat prevents nitrite-mediated benefits for ischemic limb reperfusion and ischemic vascular remodeling indicates that nitrite therapy effects involve XO-dependent metabolism. We also observed that sodium nitrate therapy was not effective in stimulating diabetic ischemic vascular remodeling compared with sodium nitrite. This may be because we did not administer enough nitrate to significantly elevate nitrite levels through the enterosalivary pathway, as larger amounts of nitrate consumption are needed to achieve increases in plasma NO metabolites compared with nitrite (36). Nonetheless, using a comparable dosing regimen over the same time course, we did not observe beneficial effects of nitrate therapy. It may also be that nitrate therapy is not effective under diabetic conditions, as a recent study by Gilchrist et al. (37) revealed that nitrate therapy was unable to alter blood pressure or affect endothelial cell dysfunction as measured by flow-mediated dilation responses in diabetic patients. Our findings are consistent with a companion study by Mohler et al. (38), indicating that sodium nitrite therapy is effective at augmenting diabetic endothelial cell dysfunction and flow-mediated dilation responses.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that sodium nitrite therapy stimulates ischemic vascular growth and tissue cytoprotection in db/db diabetic mice using two different models of tissue ischemia. Rescue of diabetic tissue ischemia involved nitrite augmentation of NO metabolites with concomitant reduction of oxidative stress and ischemic tissue reperfusion in a VEGF-dependent manner. These data highlight the potential utility of nitrite therapy as a useful modality for diabetic peripheral vascular disease.

Supplementary Material

Article Information

Funding. S.C.B. was supported by a fellowship from the Malcolm Feist Cardiovascular Research Endowment, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center–Shreveport.

Duality of Interest. T.G. and C.G.K. are participants on pending U.S. patents for the use of nitrite salts in chronic tissue ischemia, and have commercial interest in TheraVasc, Inc. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. S.C.B. researched data and wrote the manuscript. C.B.P. and G.K.K. researched data and edited the manuscript. S.P. and X.S. researched data. T.G. assisted with experimental design and edited the manuscript. C.G.K. designed experiments, analyzed data, acquired funding, and edited the manuscript. S.C.B., C.B.P., and C.G.K. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

See accompanying commentary, p. 39.

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db13-0890/-/DC1.

References

- 1.Aronow WS. Peripheral arterial disease in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging 2007;2:645–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukherjee D. Peripheral and cerebrovascular atherosclerotic disease in diabetes mellitus. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;23:335–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaper NC, Nabuurs-Franssen MH, Huijberts MS. Peripheral vascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2000;16(Suppl. 1):S11–S15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tirziu D, Simons M. Angiogenesis in the human heart: gene and cell therapy. Angiogenesis 2005;8:241–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milkiewicz M, Ispanovic E, Doyle JL, Haas TL. Regulators of angiogenesis and strategies for their therapeutic manipulation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2006;38:333–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivard A, Silver M, Chen D, et al. Rescue of diabetes-related impairment of angiogenesis by intramuscular gene therapy with adeno-VEGF. Am J Pathol 1999;154:355–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abaci A, Oğuzhan A, Kahraman S, et al. Effect of diabetes mellitus on formation of coronary collateral vessels. Circulation 1999;99:2239–2242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bir SC, Fujita M, Marui A, et al. New therapeutic approach for impaired arteriogenesis in diabetic mouse hindlimb ischemia. Circ J 2008;72:633–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suuronen EJ, Hazra S, Zhang P, et al. Impairment of human cell-based vasculogenesis in rats by hypercholesterolemia-induced endothelial dysfunction and rescue with L-arginine supplementation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;139:209–216e202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reed MJ, Edelberg JM. Impaired angiogenesis in the aged. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ 2004;2004:pe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann J, Haendeler J, Aicher A, et al. Aging enhances the sensitivity of endothelial cells toward apoptotic stimuli: important role of nitric oxide. Circ Res 2001;89:709–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruiter MS, van Golde JM, Schaper NC, Stehouwer CD, Huijberts MS. Diabetes impairs arteriogenesis in the peripheral circulation: review of molecular mechanisms. Clin Sci (Lond) 2010;119:225–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen JD, Miller EM, Schwark E, Robbins JL, Duscha BD, Annex BH. Plasma nitrite response and arterial reactivity differentiate vascular health and performance. Nitric Oxide 2009;20:231–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar D, Branch BG, Pattillo CB, et al. Chronic sodium nitrite therapy augments ischemia-induced angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:7540–7545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pattillo CB, Bir SC, Branch BG, et al. Dipyridamole reverses peripheral ischemia and induces angiogenesis in the db/db diabetic mouse hind-limb model by decreasing oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2011;50:262–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venkatesh PK, Pattillo CB, Branch B, et al. Dipyridamole enhances ischaemia-induced arteriogenesis through an endocrine nitrite/nitric oxide-dependent pathway. Cardiovasc Res 2010;85:661–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kevil CG, Kolluru GK, Pattillo CB, Giordano T. Inorganic nitrite therapy: historical perspective and future directions. Free Radic Biol Med 2011;51:576–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen RA, Tong X. Vascular oxidative stress: the common link in hypertensive and diabetic vascular disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2010;55:308–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forbes JM, Coughlan MT, Cooper ME. Oxidative stress as a major culprit in kidney disease in diabetes. Diabetes 2008;57:1446–1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Gundewar S, Bryan NS, Lefer DJ. Nitric oxide promotes distant organ protection: evidence for an endocrine role of nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:11430–11435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montenegro MF, Amaral JH, Pinheiro LC, et al. Sodium nitrite downregulates vascular NADPH oxidase and exerts antihypertensive effects in hypertension. Free Radic Biol Med 2011;51:144–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tousoulis D, Briasoulis A, Papageorgiou N, et al. Oxidative stress and endothelial function: therapeutic interventions. Recent Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov 2011;6:103–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuwabara M, Kakinuma Y, Ando M, et al. Nitric oxide stimulates vascular endothelial growth factor production in cardiomyocytes involved in angiogenesis. J Physiol Sci 2006;56:95–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bir SC, Kolluru GK, McCarthy P, et al. Hydrogen sulfide stimulates ischemic vascular remodeling through nitric oxide synthase and nitrite reduction activity regulating hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent angiogenesis. J Am Heart Assoc 2012;1:e004093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinberger J, Daniels SR, American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young Committee (Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young) American Heart Association Diabetes Committee (Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism) Obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in children: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young Committee (Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young) and the Diabetes Committee (Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism). Circulation 2003;107:1448–1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conway EM, Collen D, Carmeliet P. Molecular mechanisms of blood vessel growth. Cardiovasc Res 2001;49:507–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolluru GK, Bir SC, Kevil CG. Endothelial dysfunction and diabetes: effects on angiogenesis, vascular remodeling, and wound healing. Int J Vasc Med 2012;2012:918267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emanueli C, Monopoli A, Kraenkel N, et al. Nitropravastatin stimulates reparative neovascularisation and improves recovery from limb Ischaemia in type-1 diabetic mice. Br J Pharmacol 2007;150:873–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hazarika S, Dokun AO, Li Y, Popel AS, Kontos CD, Annex BH. Impaired angiogenesis after hindlimb ischemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus: differential regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1. Circ Res 2007;101:948–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Hazarika S, Xie D, Pippen AM, Kontos CD, Annex BH. In mice with type 2 diabetes, a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-activating transcription factor modulates VEGF signaling and induces therapeutic angiogenesis after hindlimb ischemia. Diabetes 2007;56:656–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murohara T, Asahara T, Silver M, et al. Nitric oxide synthase modulates angiogenesis in response to tissue ischemia. J Clin Invest 1998;101:2567–2578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schiekofer S, Galasso G, Sato K, Kraus BJ, Walsh K. Impaired revascularization in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes is associated with dysregulation of a complex angiogenic-regulatory network. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:1603–1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller JW, Le Couter J, Strauss EC, Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor a in intraocular vascular disease. Ophthalmology 2013;120:106–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Q, Verma A, Han PY, et al. Diabetic eNOS-knockout mice develop accelerated retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010;51:5240–5246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cantu-Medellin N, Kelley EE. Xanthine oxidoreductase-catalyzed reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide: Insights regarding where, when and how. Nitric Oxide 2013;34:19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weitzberg E, Lundberg JO. Novel aspects of dietary nitrate and human health. Annu Rev Nutr 2013;33:129–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilchrist M, Winyard PG, Aizawa K, Anning C, Shore A, Benjamin N. Effect of dietary nitrate on blood pressure, endothelial function, and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med 2013;60:89–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohler ER, III, Hiatt WR, Gornik HL, et al. Benefit of sodium nitrite in patients with peripheral artery disease and diabetes mellitus: safety, walking distance and endothelial function. Vasc Med. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.