Abstract

Objective

The underutilisation of venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis is still a problem in the UK despite the emergence of national guidelines and incentives to increase the number of patients undergoing VTE risk assessments. Our objective was to examine the reasons doctors gave for not prescribing enoxaparin when recommended by an electronic VTE risk assessment alert.

Design

We used a qualitative research design to conduct a thematic analysis of free text entered into an electronic prescribing system.

Setting

The study took place in a large University teaching hospital, which has a locally developed electronic prescribing system known as PICS (Prescribing, Information and Communication System).

Participants

We extracted prescription data from all inpatient admissions over a 7-month period in 2012 using the audit database of PICS.

Intervention

The completion of the VTE risk assessment form introduced into the hospital-wide electronic prescribing and health records system is mandatory. Where doctors do not prescribe VTE prophylaxis when recommended, they are asked to provide a reason for this decision. The free-text field was introduced in May 2012.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Free-text reasons for not prescribing enoxaparin when recommended were thematically coded.

Results

A total of 1136 free-text responses from 259 doctors were collected in the time period and 1206 separate reasons were analysed and coded. 389 reasons (32.3%) for not prescribing enoxaparin were coded as being due to ‘clinical judgment’; in 288 (23.9%) of the responses, doctors were going to reassess the patient or prescribe enoxaparin; and in 245 responses (20.3%), the system was seen to have produced an inappropriate alert.

Conclusions

In order to increase specificity of warnings and avoid users developing alert fatigue, it is essential that an evaluation of user responses and/or end user feedback as to the appropriateness and timing of alerts is obtained.

Keywords: AUDIT

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study addresses an important topic, as venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis is not always prescribed as recommended in secondary care.

The hospital in the study has its own locally developed electronic prescribing system with embedded Clinical Decision Support (CDS) in which alerts are specifically designed to encourage VTE prophylaxis (eg, prescribing of enoxaparin).

The study used data collected immediately after the implementation of a unique free-text feature within the CDS system, in which doctors can provide reasons for not prescribing enoxaparin.

The data have allowed us to highlight a number of strengths and limitations of using CDS to encourage doctors to appropriately prescribe enoxaparin in secondary care.

However, we are unable to determine whether the responses that were provided were reliable and we were also unable to take into account cases in which no free-text response was provided.

Introduction

The early identification of patients at risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and prescription of prophylaxis, where appropriate, are important measures in preventing the morbidity and mortality associated with hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism. VTE contributes to up to 10% of hospital deaths,1 2 and it is estimated that 25 000 people in the UK die each year from preventable hospital-acquired VTE.3 In the past decade, evidence-based guidelines outlining the importance of VTE prevention have been published internationally.4–7 In England, there has been an increased emphasis on programmes to educate clinicians and to incentivise hospital trusts to increase VTE risk assessment completion on admission. From June 2010, the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) payment framework required all acute trusts in the UK to assess 90% of patients admitted for the risk of VTE in order to receive 1.5% of their funding.8 The Care Quality Commission is responsible for monitoring National Health Service (NHS) trusts’ performance on the new Quality Standards throughout the UK and collects data each month on the number of VTE risk assessments completed.9 Despite the increase in VTE risk assessment completion, VTE prophylaxis is still underutilised and there is some evidence of poor adherence to the published guidelines.10–13

In the UK, computer-based rather than paper-based Clinical Decision Support (CDS) is gaining popularity as a way of prompting or guiding clinicians in the secondary care setting to prescribe appropriately. Changes to physicians' adherence to processes of care by computer reminders have been found to be modest on the whole,14 but electronic alerts and computerised CDS have been found to increase the prescription of thromboprophylaxis in hospitalised medical patients.15–18 While other studies have been undertaken to understand why physicians do not follow clinical guidelines19 and VTE prophylaxis guidelines specifically,20 few have been able to ask clinicians why prophylaxis has not been prescribed at the point of recommendation.

In this study, we were interested in doctors’ responses to a mandatory free-text field completion when acknowledging a decision support alert specific to the circumstance when a VTE risk assessment suggests prophylaxis but no prescription was completed. Nearly every patient (99%) admitted to this hospital now has their risk of developing VTE assessed on admission.21 However, the trust quality report from 2012 to 2013 identified that enoxaparin was not prescribed in 34.1% of cases when recommended by electronic risk assessment.22 We wanted to identify cases where the system was alerting inappropriately and we wished to identify where the system could lead to user frustration and ‘workarounds’ being employed to save time and ease the workload.

Methods

This study was conducted under the umbrella of a larger research project funded by the National Institute for Health Research, for which ethical approval was gained. This study involved the use of secondary data collected in the course of normal care and had no patient identifiers or patient-sensitive information, so it was anonymised to the researchers at the point of access.

Setting

This study was conducted in a large NHS university hospital, which has a locally developed electronic prescribing system known as PICS (Prescribing, Information and Communication System). PICS is in operation throughout all (approximately 1200) inpatient beds and for all prescribing. The system was first installed in the renal unit 15 years ago23 and now covers general and specialist medical and surgical specialties. For the purpose of this study, a key feature of the system is that all information about prescriptions and dose administrations are exported to a comprehensive audit database on a weekly basis.

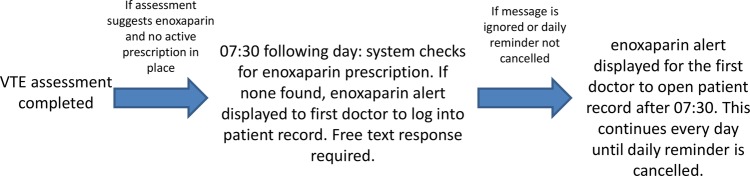

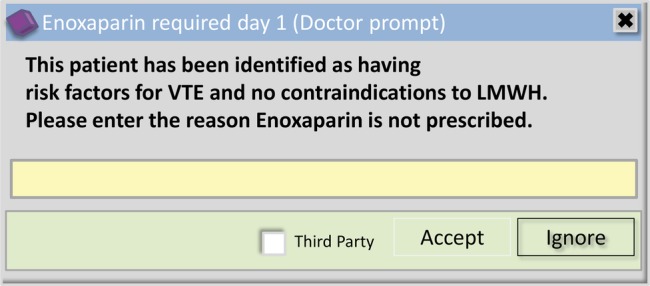

The hospital has prioritised measures to reduce the occurrence of hospital-acquired VTE over the past few years. In June 2008, a VTE risk assessment tool was introduced into PICS with an alert issued to remind doctors if the risk assessment was not completed. From June 2010, in line with the national guidelines and data collection, the completion of VTE risk assessment within the trust became mandatory for every admitted patient. The assessment has to be completed before the patient record and drug prescribing is enabled for that admission. Following the completion of the risk assessment, a scheduled decision support rule is run in PICS that reviews the current prescriptions for each patient and automatically generates an alert where, as indicated by the risk assessment, enoxaparin should be prescribed but is not currently prescribed. This initial alert is displayed to the first prescriber to view the patient's medical records on PICS (this process is summarised in figure 1) and requires a written free-text response to explain why enoxaparin has not been prescribed (see figure 2). Further details about the electronic VTE risk assessment process are provided in online supplementary appendix A.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of venous thromboembolism (VTE) alert production.

Figure 2.

Initial enoxaparin alert (free-text alert; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; VTE, venous thromboembolism).

Data capture

Our outcome was the reason given for not prescribing enoxaparin where recommended by the VTE risk assessment. These responses were obtained from the enoxaparin free-text alert shown in figure 2. Data were extracted from the PICS audit database on all enoxaparin alerts generated between 1 June 2012 and 31 December 2012. The anonymised data were extracted into Excel for analysis.

Analysis

Four reviewers (UN, HB, SR and LM) independently conducted preliminary content analysis of the respondents’ reasons for not prescribing enoxaparin. Themes were allowed to emerge from the data in an iterative process, with initial themes informing and contextualising subsequent themes and vice versa. The reviewers then met to discuss their analyses and sought to reach consensus where the reasons were unclear. A consultant physician (JJC) provided clinical context to reasons that the reviewers found difficult to categorise. The four reviewers then independently coded the data. Whole group discussion was used to refine coding and to identify overarching themes which helped to group subordinate themes, until consensus was reached. Representation of each theme is given as the actual number of reasons observed (some responders gave more than one reason) and percentage of total reasons provided.

Results

During the 7-month time period, there were 37 737 admissions to the hospital. On the basis of figures from the Trust quality account, approximately 37 340 (99%) would have received a VTE risk assessment. A total of 1136 free-text responses were provided from 259 doctors in response to the enoxaparin alert, which equates to 9% of the approximately 12 740 (34.1%) who were not prescribed enoxaparin when recommended. Some responses contained multiple reasons. As such, a total of 1206 reasons were recorded and coded.

Six main themes were identified from the reasons provided for not having prescribed enoxaparin. These themes and the number of reasons coded within each theme are displayed in table 1.

Table 1.

Frequency of reasons for not prescribing enoxaparin by theme

| Reasons for not prescribing enoxaparin (by theme) | Number of responses | Percentage of all responses (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical judgment | 389 | 32.3 |

| Positive response initiated | 287 | 23.8 |

| System | 246 | 20.4 |

| Surgery | 139 | 11.5 |

| Ambiguous | 81 | 6.7 |

| Drug contraindication | 64 | 5.3 |

| Total | 1206 | 100 |

The reviewers coded 23.8% of the responses provided as ‘positive response initiated’. Here, doctors indicated that they would go on to prescribe enoxaparin after having read the message or that they would review the patient's VTE risk as a result of the message. Examples of responses are: “will review”; “will prescribe”; “oversight—prescribed by myself today.”

The most common type of reason given for not prescribing enoxaparin was due to ‘clinical judgment’, and represents 32.3% of the reasons given. The ‘clinical judgment’ theme can be further broken down into five main categories: clinical reason; patient mobile; patient discharged or soon to be discharged; patient at risk of bleeding; and patient at risk of falls. The distribution of these reasons (as a percentage of all clinical judgment coded reasons) can be seen in table 2. The category of ‘clinical reason’ refers to a broad range of reasons which are either:

An explicit clinical judgment, for example, “not required,” “end of life care. no benefit from enoxaparin” and “consultant decision”;

Situation-specific such as “liver failure,” “stroke” and “bleeding ulcer” or

Where further information was needed before a full assessment could be made, for example, “clinical information still pending,” “awaiting blood results” and “low Hb? cause.”

Table 2.

Frequency of reasons for not prescribing enoxaparin within the theme ‘clinical judgment’

| Clinical judgment reasons for not prescribing enoxaparin | Number of responses | Percentage of all responses (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical reason | 120 | 30.8 |

| Patient mobile | 111 | 28.5 |

| Discharge* | 84 | 21.6 |

| Risk of bleeding† | 64 | 16.5 |

| Falls risk | 10 | 2.6 |

| Total | 389 | 100 |

*Patient about to be discharged or had been discharged by the time of the alert.

†Patient under investigation for bleeding risk or known condition.

A fifth of the free-text reasons were coded as ‘system’ and reflect those alerts deemed as being generated inappropriately or caused by a system error which led to the production of the alert. Responses coded as ‘system’ often reflected cases where enoxaparin had been prescribed after the alert had been generated on day 1, but before a reason had been given. If the rules-based alert is ignored or closed, it will continue to appear to subsequent prescribers logging on to the patient record. Currently, the rules-base alert is not cancelled by the system automatically if an appropriate prescription is made in the interim. Examples of free-text responses include “already prescribed,” “it is,” “has been” and “enoxaparin prescribed.” In some cases, the free-text reason was indicative of users’ frustrations with these persistent alerts. For example, this was demonstrated by the use of multiple exclamation marks in 29 out of 246 (11.8%) ‘system’ reasons. Furthermore, some users overtly stated their frustration with the alert. For example, “It’s been prescribed so this message is something of a frustration” and “It is prescribed—PICS giving false warning x 3.”

The theme ‘surgery’ (11.5% of reasons given) refers to the patient being in the perioperative period or undergoing a specific surgical procedure where it was thought that prescribing enoxaparin was not appropriate. For example, free-text responses included “not meant to have enox until 12 hours post surgery—according to protocol,” “post operative—for review” and “on theatre list today.” Additionally, some reasons alluded to inappropriate prescribing of enoxaparin as a result of the patient's postoperative condition: “late operation yesterday with post-op haematoma” and “Post neurosurgery. Bleeding around EVD site.”

The theme ‘ambiguous’ (6.7% of responses) refers to cases which did not relate to a clinical indication or process such as “not yet reviewed” or “patient not known to me” or simply “don't know.” Finally, 5.3% of the reasons were coded as ‘drug contraindication’ as the patient had (since the VTE risk assessment) been prescribed a drug with a similar action, such as warfarin or heparin. The rules-base does not check for such prescriptions, as the risk assessment is specific in recommending enoxaparin.

Discussion

In a quarter of cases where a free-text response was provided, the system succeeded in prompting either a repeat review of the patient or a prescription of enoxaparin where it had been overlooked or delayed. In these cases, the alert produced the positive response that was intended by its implementation.

The main reasons for not prescribing enoxaparin when recommended were due to ‘clinical judgment’. As the use of any such tool is not intended to replace clinical judgment, we would have expected that clinicians would delay or avoid prescribing VTE prophylaxis until the patient has been fully assessed. The tool is, however, designed to provide decision support deemed appropriate for the majority of cases. It may be prudent to wait until test results return and a more complete picture emerges of the patient's condition. Clearly, complete compliance with the recommendations before all information is assessed would be just as dangerous as poor compliance.

Where the system or process does not seem to work as well is when it produces a seemingly inappropriate alert. Of concern were the responses (20.4%) that indicated doctors felt there had been a system error which had led to inappropriate or inaccurate alert generation. A lack of specificity in the alerting process can result in doctors unnecessarily being alerted when, for example, a patient has already been prescribed a lower than recommended dose of enoxaparin as per their therapeutic needs or where enoxaparin is not prescribed as the patient is to undergo surgery.

Despite the risk assessment algorithm incorporating details of the surgery the patient was about to have (alongside the likely duration and likelihood of decreased mobility), 11% of the reasons for not prescribing were due to the timing of the surgery and the type of surgery. Surgical VTE risk assessments require a complex algorithm to capture the types of surgery, the patient's condition and risks of bleeding therein. The electronic risk assessment is completed within the first few hours of admission and it would seem from the responses that the delay or avoidance in prescribing enoxaparin stems from the perceived risk of major bleeding linked with certain surgical procedures and with the timing of the alert. When alerts are produced preoperatively, there may be an expectation that VTE prophylaxis will be given in theatre after surgery or, in cases where the alert is read postoperatively, the patient has returned to the ward after having been administered VTE prophylaxis as per protocol or indeed may have postoperative complications that rule out pharmacological prophylaxis. An established parallel system exists for surgical patients outside of the ward area, and the timing of the free text and daily reminder alerts produced will not be sensitive to timing issues (eg, delayed theatre list) or changes in a patient's risk of bleeding (eg, postoperative complications).

This lack of specificity of the alerts produced by VTE risk assessment leads to the question of whether is it better to have irrelevant alerts rather than no alerts. Specificity could be increased by including a check for prescriptions of warfarin or unfractionated heparin as contraindications to prescribing enoxaparin or preventing the generation of the alert no matter what dosage of enoxaparin is prescribed. This would reduce the number of alerts produced where an alternative anticoagulant is already prescribed or where enoxaparin is prescribed at a different dosage, thereby reducing inappropriate alerting. It is noteworthy that a prescription of warfarin or a patient being already given anticoagulants is part of the VTE risk assessment process—and the correct recording of this would contraindicate enoxaparin and suppress subsequent alerts.

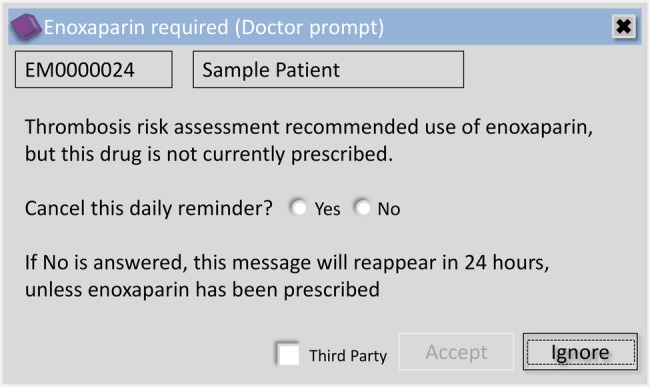

The timing of the alert can be an issue, for example, when clinicians are presented with the free-text alert even when an enoxaparin prescription is visible on the system. To the clinician, the alert has been generated inappropriately, but this does not provide a full picture. Of note, the system only cross-checks for an enoxaparin prescription once per day at 07:30. Therefore, when the free-text alert (figure 2) is bypassed on day 1 (so-called ‘third-party ignore’), it will be shown again on day 1 to other (or the same) clinicians who next access the patient's record regardless of whether enoxaparin has since been prescribed. For example, if an enoxaparin prescription has been written during the morning ward round and no response is entered to the free-text alert, the alert will still be shown the next time the patient's record is accessed. As long as no free-text response is entered that day and enoxaparin has not been prescribed, the daily reminder (figure 3) and the free-text alert will reappear on day 2 when the system cross-checks the prescription data. Despite causing some frustration, allowing third-party dismissal of alerts means that it can still be visible to clinicians directly responsible for the patient's care. This frustration may be unavoidable in some cases as the alert is presented to anyone with authorisation to prescribe. In the case of bank/locum doctors or those who are not familiar with the patient, they may be unaware of the reason that enoxaparin has not been prescribed and therefore may not respond appropriately (eg, they may just be logging on to PICS to familiarise themselves with the patient prior to meeting them). The only way to truly avoid this is to change the system to check for a prescription prior to each presentation of the alert.

Figure 3.

Subsequent enoxaparin alert.

What is of concern is the likelihood of fatigue due to excessive alerts and workarounds, especially when the mechanisms behind the alert generation are not understood. We found four examples in the data of clinicians entering full stops in the free-text field to make the alert recede (3 by the same clinician). Frustration is often secondary to inappropriate use of the system, for example, failure to acknowledge alerts even when doing the correct thing or not noting options in the risk assessment which would suppress future alerts.

Limitations

In this research, we have obtained information regarding the real-time reasons and feedback from responses left during the workflow. This allows for a deeper understanding of user experiences and how the VTE alerts within the electronic prescribing system are received. What is particularly useful is that we have examined data regarding the free-text alerts for the first 7 months after its initial implementation, meaning that our findings will allow us to give feedback and make changes to the system if and where appropriate. This evaluation of our own system may lead to improvements which we can then share with other system providers.

Nonetheless, in this study, we are unable to take into account those cases in which no free-text response was provided at all. The system was effective in prompting doctors to provide a reason for not prescribing enoxaparin in 1136 cases. In the remaining approximately 11 600 cases where no free-text response was obtained, this may be attributed to patients being discharged prior to the free-text alert being triggered. Furthermore, from our data, we are unable to determine whether the responses that are provided by doctors are reliable (ie, honest) or if there are more complex reasons behind not having prescribed enoxaparin. For example, some responses are written in capital letters and it is not possible to tell whether this is done due to frustration or whether it is a default by the keyboard that the doctor is using. Other incomplete responses meant that we were not provided with information that we could utilise in our analysis. We are also unable to determine whether a prescription was actioned even when a positive response to the free-text alert was given. Finally, the single site nature of the study further limits the generalisability of the findings.

To follow on from this research, it would be useful to organise discussion groups or forums in which doctors can verbally discuss their perceptions of the VTE alerts (and perhaps decision support warnings more generally) and provide some more context to their responses. Alternatively, it may be interesting to shadow doctors on the ward and observe their response as they use the system and as alerts are generated. Furthermore, it might be useful to investigate the process of VTE assessment and appropriate anticoagulant prescription for surgical patients in more detail. This might help to establish whether it may be necessary to design a parallel system for these patients, which may lead to the prescription being made/decision not to prescribe due to the time of surgery. It might be interesting to utilise stealth alerts/stealth processes24 through a third party in order to alert the patient's regular doctor/consultant to a lack of VTE prophylaxis or, for example, alert a pharmacist to check the dose where an enoxaparin prescription is present but the dose is not what would normally be recommended.

The ultimate aim of using the electronic prescribing system is to improve patient safety by receiving appropriate VTE risk assessment and treatment. Since this study was conducted, the system has been updated so that doctors are now automatically taken to a blank prescription page if enoxaparin is recommended following the VTE risk assessment. System improvements such as this are required to support the assessment processes, prescriber engagement and education to take the appropriate action.

Conclusion

This study examined the free-text reasons given by doctors when they have not yet prescribed the prophylaxis suggested by the VTE risk assessment tool. The analysis shows that doctors bypass the recommendations because they are rationalising the VTE risk and use of prophylaxis on the emerging picture of the patient's condition on the one hand, and they become frustrated with the system because of lack of training on the other. Understanding why doctors use workarounds will enable healthcare providers to modify systems or training programmes to reduce alert fatigue while optimising the appropriateness of CDS alerts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mariam Afzal, Lina Stezhka and Dave Thompson.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. UN, HB, SR and LM were involved in the study conception and design and the data coding and analysis. UN, HB, SR, LM and JJC were involved in the drafting and revision of the manuscript. JJC was involved in the study conception and design and the data analysis. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript, the interpretation of data and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Birmingham and Black Country (CLAHRC-BBC) programme. This article presents independent research funded by the NIHR.

Competing interests: JJC works within the University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, which is collaborating with CSE Healthcare Systems to commercialise the PICS system in the UK.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Original data containing the free-text responses and codes are available from the corresponding author, JJC (j.j.coleman@bham.ac.uk).

References

- 1.Sandler DA, Martin JF. Autopsy proven pulmonary embolism in hospital patients: are we detecting enough deep vein thrombosis? J R Soc Med 1989;82:203–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen AT, Agnelli G, Anderson FA, et al. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe. The number of VTE events and associated morbidity and mortality. Thromb Haemost 2007;98:756–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.House of Commons Health Committee. The prevention of venous thromboembolism in hospitalised patients. London, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geerts W, Bergqvist D, Pineo G. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition). Chest 2008;133:381S–453S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health Medical Research Council. Clinical practice guideline for the prevention of venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) in patients admitted to Australian hospitals. Melbourne, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health Clinical Excellence. Venous thromboembolism: reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) in patients admitted to hospital. London, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network . Prevention and management of venous thromboembolism. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health. Using the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) payment framework (with addendum for 2010/11) 2009

- 9.Power M, Stewart K, Brotherton A. What is the NHS safety thermometer? Clin Risk 2012;18:163–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen AT, Tapson VF, Bergmann J-F, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet 2008;371:387–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark BM, d'Ancona G, Kinirons M, et al. Effective quality improvement of thromboprophylaxis in acute medicine. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:460–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thavarajah D, Wetherill M. Implementing NICE guidelines on risk assessment for venous thromboembolism: failure, success and controversy. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2012; 25:618–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrne S, Weaver DT. Review of thromboembolic prophylaxis in patients attending Cork University Hospital. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35:439–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shojania KG, Jennings A, Mayhew A, et al. Effect of point-of-care computer reminders on physician behaviour: a systematic review. CMAJ 2010;182:E216–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galanter WL, Thambi M, Rosencranz H, et al. Effects of clinical decision support on venous thromboembolism risk assessment, prophylaxis, and prevention at a university teaching hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2010;67:1265–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucher N, Puck M, Blaser J, et al. Physician compliance with advanced electronic alerts for preventing venous thromboembolism among hospitalized medical patients. J Thromb Haemost 2009;7:1291–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams P, Riggio JM, Thomson L, et al. Clinical decision support systems to improve utilization of thromboprophylaxis: a review of the literature and experience with implementation of a computerized physician order entry program. Hosp Pract (1995) 2012;40:27–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeidan AM, Streiff MB, Lau BD, et al. Impact of a venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis “smart order set”: improved compliance, fewer events. Am J Hematol 2013;88:545–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? JAMA Intern Med 1999;282:1458–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakkar A, Davidson B, Haas S. Compliance with recommended prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism: improving the use and rate of uptake of clinical practice guidelines. J Thromb Haemost 2004;2:221–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Health Service England. VTE Risk Assessment data collection: 2012–13 Quarter 3 data. 01/03/2013 ed London: NHS England, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 22.University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust. Quality Account 2012–13, 2013. http://www.uhb.nhs.uk/Downloads/pdf/QualityAccount12-13.pdf ( accessed 19 Sept 2014)

- 23.Nightingale PG, Adu D, Richards NT, et al. Implementation of rules based computerised bedside prescribing and administration: intervention study. BMJ 2000;2000:750–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koplan KE, Brush AD, Packer MS, et al. “Stealth” alerts to improve warfarin monitoring when initiating interacting medications. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1666–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.