Abstract

Objectives

We hypothesise that there is an association between an elevated pulmonary artery/aorta (PA/A) and World Trade Center-Lung Injury (WTC-LI). We assessed if serum vascular disease biomarkers were predictive of an elevated PA/A.

Design

Retrospective case-cohort analysis of thoracic CT scans of WTC-exposed firefighters who were symptomatic between 9/12/2001 and 3/10/2008. Quantification of vascular-associated biomarkers from serum collected within 200 days of exposure.

Setting

Urban tertiary care centre and occupational healthcare centre.

Participants

Male never-smoking firefighters with accurate pre-9/11 forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) ≥75%, serum sampled ≤200 days of exposure was the baseline cohort (n=801). A subcohort (n=97) with available CT scans and serum biomarkers was identified. WTC-LI was defined as FEV1≤77% at the subspecialty pulmonary evaluation (n=34) and compared with controls (n=63) to determine the associated PA/A ratio. The subcohort was restratified based on PA/A≥0.92 (n=38) and PA/A<0.92(n=59) to determine serum vascular biomarkers that were predictive of this vasculopathy.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of this study was to identify a PA/A ratio in a cohort of individuals exposed to WTC dust that was associated with WTC-LI. The secondary outcome was to identify serum biomarkers predictive of the PA/A ratio using logistic regression.

Results

PA/A≥0.92 was associated with WTC-LI, OR of 4.02 (95% CI 1.21 to 13.41; p=0.023) when adjusted for exposure, body mass index and age at CT. Elevated macrophage derived chemokine and soluble endothelial selectin were predictive of PA/A≥0.92, (OR, 95% CI 2.08, 1.05 to 4.11, p=0.036; 1.33, 1.06 to 1.68, p=0.016, respectively), while the increased total plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 was predictive of not having PA/A≥0.92 (OR 0.88, 0.79 to 0.98; p=0.024).

Conclusions

Elevated PA/A was associated with WTC-LI. Development of an elevated PA/A was predicted by biomarkers of vascular disease found in serum drawn within 6 months of WTC exposure. Increased PA/A is a potentially useful non-invasive biomarker of WTC-LI and warrants further study.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Well-phenotyped cohort with lung function tests prior to exposure available.

Identification of a viable pulmonary artery to aorta (PA/A) ratio (0.92) as a biomarker associated with World Trade Center (WTC)-Lung Injury.

Identification of biomarkers predictive of PA/A vasculopathy.

Limited generalisability because of the unique WTC-related exposure.

Retrospective study design and logistic regression implies only associated findings, and does not reflect causality.

Background

Development of lung disease after the World Trade Center (WTC) exposure has been a common finding among exposed workers, volunteers and lower Manhattan residents. In rescue/recovery workers from the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY), WTC exposure led to WTC-Lung Injury (WTC-LI).1 2 Our group has previously defined WTC-LI as the chronic inflammatory lung dysfunction experienced by a subcohort of firefighters with intense exposure to WTC dust.1 2 It is characterised by primarily obstructive respiratory dysfunction with substantial and persistent losses in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)% predicted to ≤77% in the subsequent 6.5 years postexposure. In addition, systemic biomarkers of inflammation, metabolic derangement and cardiovascular disease (CVD) predict WTC-LI.2–4

One of the hallmarks of particulate matter exposure is systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and subsequent end-organ damage. High ambient particulate matter exposures significantly decrease FEV1 in a period as short as 5–7 days. Epidemiological investigation has documented associations between increased ambient particulates, lung disease and CVD. Systemic inflammation produces vascular endothelial injury and subsequent vascular disease. Recent studies associate systemic vascular involvement with lung disease and prospective studies have demonstrated an association between impaired lung function and central arterial stiffness even before the development of frank vascular disease, with systemic inflammation contributing to this association.5–7

Pulmonary vascular injury occurs early in smoking-related chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with pulmonary perfusion abnormalities and reduced blood return to the heart is observed prior to development of WTC-LI.8–10 A similar pathophysiology most likely occurs in irritant induced lung disease. Pulmonary arteriopathy was present in 58% of lung biopsies from non-FDNY-WTC exposed individuals and in 74% with constrictive bronchiolitis after inhalational exposures during military service in Iraq and Afghanistan.11 12 An increased ratio of the pulmonary artery to aorta (PA/A) diameter measured by CT has been associated with pulmonary hypertension and poor outcomes in various disease states. Additionally, an elevated PA/A has been associated with past and future exacerbations in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD.13 The PA/A has been associated with a decreased FEV1 in the same population. Multiple serum biomarkers have been identified that predict vascular disease and several have been incorporated into clinical practice. To date, there have been no serum biomarkers identified that predict an enlarged PA/A in obstructive lung disease.

Utilising a nested case–control design, we investigated if an elevated PA/A was associated with WTC-LI in a population that also had serum biomarkers. We then determined the ability of vasoactive serum biomarkers drawn within 6 months of 9/11/2001 to predict the eventual development of an elevated PA/A.

Methods

Study design

Annual physicals occurred prior to 9/11/2001, and active-duty firefighters had normal lung function testing, ECG assessment and measures of exercise capacity. Those with abnormal cardiopulmonary testing were placed on medical leave and were not part of the rescue and recovery efforts.

WTC exposed FDNY firefighters (N=1720) entered the FDNY-WTC Health Program and had spirometry at entry into medical monitoring as previously described.1 Symptomatic participants referred for subspecialty pulmonary evaluation (SPE) between 10/1/2001 and 3/10/2008 underwent specialised pulmonary function testing as previously described.1 Inclusion criteria were applied to the symptomatic cohort. In total, N=801/1720 (47%) were never-smokers, male, had reliable National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) normative data for the FEV1% predicted, entered FDNY-WTC Health Program within 200 days of 9/11/2001 and had pre-9/11 FEV1>75% predicted. All participants signed an informed Institutional Review Board approved consent at the time of enrolment allowing analysis of their information and samples for research (Montefiore Medical Center; #07-09-320 and New York University; #11-00439).

FEV1% predicted at SPE was used as a measurable, phenotypic marker of WTC-LI. Cases represented those who had continued lung dysfunction that we termed WTC-LI, whereas controls represented those who did not have WTC-LI. Cases (N=100) were defined as being within one SD of the lowest FEV1% predicted of the cohort at SPE (FEV1≤77%). Controls (N=153) were those who had FEV1>77% and were randomly selected after stratification based on body mass index (BMI) and FEV1 as previously defined.1

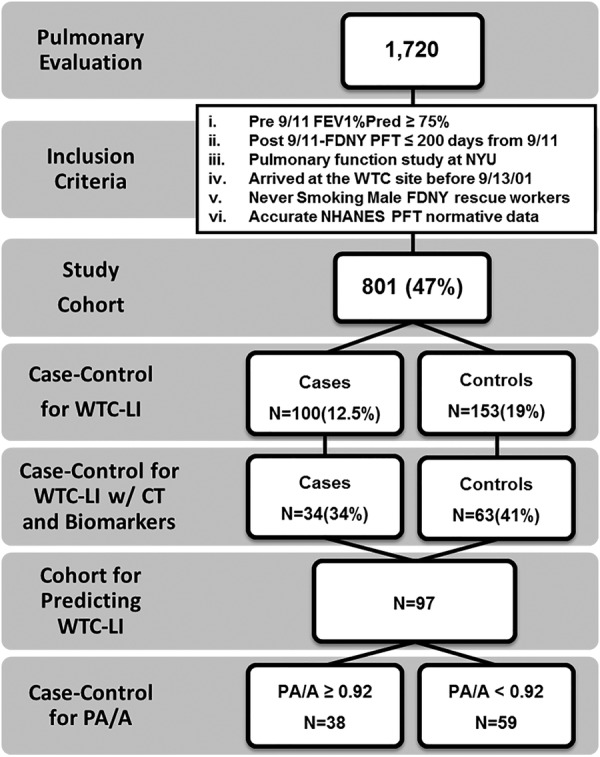

CT scans were administered as standard of care measures to the population, but only a subset was available at the single centre where this research was conducted. Serum biomarkers and CT scans were available for N=34/100 cases and N=63/153 controls (figure 1). The population was then restratified by the PA/A ratio using a cut-off of 0.92 for analysis of biomarkers predictive of PA/A.

Figure 1.

Study design. Participants in the FDNY-WTC Health Program presented for pulmonary evaluation (SPE). The baseline cohort met the listed inclusion criteria. Cases (N=34) and controls (N=63) had CT and biomarkers available. A, aorta; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FDNY, Fire Department of the City of New York; WTC-LI, World Trade Center-Lung Injury; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NYU, New York University; PA, pulmonary artery; PFT, pulmonary function test.

Demographics

Age, gender and years of service at FDNY were obtained from the FDNY-WTC Health Program database. Degree of exposure was self-reported at the first FDNY-WTC monitoring examination and was categorised using the FDNY-WTC Exposure Intensity Index (arrival time): present on the morning of 9/11/2001 or arrived after noon on 9/11/2001.1 Those arriving after day 3 were excluded from the analysis as a result of their low numbers in this sample. Height and weight were measured at the SPE.

Lung function measures and CT

Pulmonary function testing was performed according to American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) guidelines as described. The first available post-9/11 CT was retrieved for the 34 cases and 63 controls. Contrast studies and CT scans obtained after 2009 were not included. Bronchial wall thickening (BWT) and air trapping (AT) were previously assessed.1 Inspiratory images, collected with a BF40 algorithm and viewed on standard mediastinal windows, were reviewed using iSite PACS (Philips iSite Enterprise, V.3.6.114; http://www.healthcare.philips.com). The diameter of the main PA at the level of its bifurcation and the diameter of the ascending A in its maximum dimension were recorded using the same image, online supplementary figure S1. The reader, trained by a board certified radiologist in this method, was blinded to the case status.13 14

Serum sampling and analysis

Fasting blood was drawn at the first post-9/11 FDNY-WTC monitoring examination, processed and stored (Bio-Reference Laboratories, Inc, Elmwood Park, New Jersey, USA) as previously described.

The serum was analysed using a CVD-1(HCVD1-67AK) and a 39-Plex Human Pro-inflammatory Panel according to the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) on a Luminex 200IS (Luminex Corporation, Austin, Texas, USA).

Data were analysed with the MasterPlex QT software (V.1·2; MiraiBio, Inc). Each batch of the samples processed contained controls and cases in an approximate 12/7 ratio as previously described.4

Statistical analysis

SPSS 20 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) and STATA V.12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA) were used for database management and statistics. Demographics, CT data and analyte levels were compared by the Student t test, Mann-Whitney U test and χ2 test where appropriate. The cut-off point of the PA/A ratio that maximised the value of the Youden index (sensitivity+specificity−1) was used for predicting the development of WTC-LI.15 Logistic regression was used to first see if the PA/A ratio was a marker of WTC-LI. Then a separate logistic regression was used to analyse if serum biomarkers could predict the PA/A ratio. Variables identified as potential confounding factors in previous studies and those with a p<0.20 in the univariable analysis were included in the multivariable logistic regression model. A backward stepwise approach was used to determine the most parsimonious model for the serum biomarkers, with a prespecified p<0.10. Hosmer-Lemeshow's goodness-of-fit test was used to assess calibration of the model. The model discrimination was evaluated through the receiver operating characteristic area under the curve (AUC). To test the robustness of the serum biomarker models, internal validation was performed using bootstrapping (10 000 bootstrap samples). Data are expressed as the mean (SD), median (IQR) or OR (95% CI), unless otherwise stated. A two-sided p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographics of the case–control study

This case–control study was drawn from a population of 801 never-smokers with normal pre-9/11 lung function. In total, 253/801 individuals had serum available from their first post-9/11 monitoring examination. Non-contrast chest CT was available for review from 97 participants (34/100 cases and 63/153 controls). The demographics of individuals with available serum and CTs are summarised in table 1. The control and case groups had similar WTC exposure: time from 9/11 to the first post-9/11 monitoring examination, time from 9/11 to SPE, years of service and age at 9/11. BMI, body surface area (BSA) and height of cases were higher than controls at SPE.

Table 1.

Demographics, CT and pulmonary function test data

| Event | Measure | Cases | N | Controls | N | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-9/11 | FVC (%) | 84 (80–94) | 34 | 97 (89–111) | 63 | <0.001 |

| FEV1 (%) | 86 (82–95) | 34 | 104 (93–114) | 63 | <0.001 | |

| FEV1/FVC | 84 (79–87) | 34 | 85 (82–89) | 63 | 0.960 | |

| At 9/11 | Present at collapse* | 12 (35) | 34 | 18 (29) | 63 | 0.494 |

| Arrived later* | 22 (65) | 34 | 45 (71) | 63 | ||

| Years of service | 15 (7–20) | 34 | 13 (6–18) | 63 | 0.317 | |

| SPE | 9/11 to SPE (months) | 34 (25–52) | 34 | 33 (24–57) | 63 | 0.928 |

| FVC (%) | 76 (72–86) | 34 | 96 (90–104) | 63 | <0.001 | |

| FEV1 (%) | 72 (64–74) | 34 | 96 (90–102) | 63 | <0.001 | |

| FEV1/FVC | 74 (65–78) | 34 | 78 (75–82) | 63 | 0.004 | |

| BD response | 15 (6–25) | 30 | 4 (1–9) | 33 | 0.001 | |

| TLC (%) | 86 (80–101) | 28 | 105 (98–112) | 32 | <0.001 | |

| FRC (%) | 84 (76–100) | 28 | 102 (91–109) | 32 | 0.002 | |

| RV (%) | 130 (107–145) | 28 | 129 (115–141) | 32 | 0.859 | |

| DLCO (%) | 95 (85–106) | 27 | 106 (99–113) | 31 | 0.006 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31 (29–34) | 34 | 29 (27–31) | 63 | 0.004 | |

| CT | PA† | 29.22 (3.24) | 34 | 28.19 (3.23) | 63 | 0.138 |

| A† | 32.09 (3.68) | 34 | 31.95 (3.19) | 63 | 0.850 | |

| PA/A† | 0.92 (0.11) | 34 | 0.89 (0.10) | 63 | 0.151 | |

| PA/A≥0.92* | 18 (53) | 34 | 20 (32) | 63 | 0.042 | |

| BWT* | 12 (36) | 33 | 21 (34) | 61 | 0.851 | |

| Air trapping* | 19 (58) | 33 | 25 (41) | 61 | 0.124 | |

| Age | 47 (41–51) | 34 | 46 (42–51) | 63 | 0.791 | |

| Height (cm) | 182 (178–183) | 34 | 178 (173–183) | 63 | 0.041 | |

| BSA (m2) | 2.24 (2.17–2.43) | 34 | 2.09 (2.01–2.28) | 63 | 0.001 |

Expressed as median (IQR) except *Expressed as N (%), †Expressed as mean (SD). A, aorta; BSA, body surface area; BD, bronchodilator; BMI, body mass index; BWT, bronchial wall thickening; DLCO, diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; FRC, functional residual capacity; PA, pulmonary artery; RV, residual volume; SPE, pulmonary evaluation; TLC, total lung capacity.

Lung function

Cases had a lower FEV1 than controls at pre-9/11 and at SPE (table 1). Cases also had a lower FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio, total lung capacity, functional residual capacity and diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide at SPE. Cases had an increased bronchodilator response. At pre-9/11 testing, the FEV1/FVC ratio was similar. FEV1 in cases and controls declined from pre-9/11 to SPE (104–96% and 86–72%, respectively; p<0.001 all comparisons). FVC demonstrated a similar pattern. To confirm that the median FEV1 difference represented individual changes, we used patients as their own controls. The mean ratio of FEV1 was 0.92 vs 0.77 in controls versus cases, respectively, between pre-9/11 and SPE testing, p<0.001, demonstrating a significantly greater loss of lung function in cases as compared with controls, even when analysed individually.

CT scan measurements

PA and A measurements on available CTs from cases and controls are outlined in table 1. The PA diameter was modestly correlated with BSA and BMI (r=0.219, 0.265; p=0.031, 0.009, respectively), but did not vary with height or age. The A diameter demonstrated modest correlation with age and BMI (r=0.376, 0.284; p<0.001, 0.005, respectively). The measured PA/A declined with increased age (r=−0.256, p=0.011) but was not significantly associated with height, BSA or BMI, which is similar to reported associations in a larger cohort study.16 The mean PA/A in cases was 0.92, similar to the 90% upper limit of normal in the Framingham Heart Study.16 Cases had similar proportions of AT and BWT to controls.

PA/A as a biomarker of WTC-LI

After calculating the Youden index, a PA/A value of 0.92 was selected as the cut-off for predicting the development of WTC lung injury in a logistic regression analysis. After adjusting for age at CT, pre-9/11 FEV1, BMI at SPE and exposure, the odds of having a low FEV1 at SPE in patients with a value of PA/A≥0.92 were 4.02 (95% CI 1.21 to 13.41; p=0.023) times larger than the odds of those patients with a value <0.92 (AUC=0.854 (95% CI 0.773 to 0.934); Hosmer-Lemeshow's p=0.55).

Vascular disease biomarkers and PA/A association

CT measurements across the PA/A of 0.92 are displayed in online supplementary table S1. There were 38 individuals with a ratio ≥0.92 and 59 with a ratio <0.92. There was a higher proportion of measured BWT in the low ratio group. There was a similar amount of AT in both groups. Age and time since 9/11 were similar in both groups. Height, age, BSA, BMI and exposure intensity were similar across the PA/A ratio of 0.92 (data not shown).

Levels of analytes across the ratio of 0.92 are displayed in table 2. The results of multivariable logistic analysis using the backward stepwise approach are shown in table 3. For each 1 ng/mL increase of serum macrophage derived chemokine (MDC), the odds of having a subsequent PA/A ratio ≥0.92 increased by 2.08-fold (95% CI 1.05 to 4.11). For each 10 ng/mL increase in soluble endothelial selectin (sE-selectin) and total plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (tPAI-1), the odds of having a PA/A ratio ≥0.92 increased by 33% (95% CI 6% to 68%) and decreased by 12% (95% CI 2% to 21%), respectively.

Table 2.

Biomarker PA/A relationship

| Analyte ng/mL |

PA/A |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥0.92 N=37 |

<0.92 N=59 |

||

| MDC | 1.51 (1.21–2.01) | 1.41 (0.99–1.77) | 0.101 |

| Adiponectin | 12 770 (9510–20 941) | 13 218 (10 037–18 537) | 0.789 |

| sE-selectin | 49.7 (36.5–63.2) | 42.8 (35.3–56.1) | 0.153 |

| tPAI-1 | 119.8 (84.5–152.4) | 139.7 (119.5–173.3) | 0.057 |

| MMP-9 | 345.7 (265.8–465.3) | 352.4 (267.9–517.9) | 0.949 |

| MPO | 141.0 (104.3–226.1) | 135.3 (95.1–289.0) | 0.865 |

| sICAM-1 | 165.2 (130.4–197.4) | 157.8 (136.1–201.8) | 0.952 |

| sVCAM-1 | 1355 (1119–1679) | 1335 (1108–1602) | 0.617 |

Values expressed as median (IQR). MDC, macrophage derived chemokine; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MPO, myeloperoxidase; sE-selectin, soluble endothelial selectin; sICAM, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule; sVCAM, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule; tPAI, total plasminogen activator inhibitor.

Table 3.

Serum biomarker models predicting pulmonary artery/aorta ≥0.92

| Model | Analytes | Crude |

Adjusted* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| Univariable | MDC | 1.70 (0.90 to 3.19) | 0.100 | 1.78 (0.93 to 3.37) | 0.080 |

| sE-selectin | 1.18 (0.97 to 1.44) | 0.093 | 1.20 (0.98 to 1.47) | 0.075 | |

| tPAI-1 | 0.92 (0.84 to 1.01) | 0.093 | 0.93 (0.85 to 1.03) | 0.148 | |

| Multivariable | MDC | 1.99 (1.02 to 3.88) | 0.043 | 2.08 (1.05 to 4.11) | 0.036 |

| sE-selectin | 1.32 (1.05 to 1.65) | 0.018 | 1.33 (1.06 to 1.68) | 0.016 | |

| tPAI-1 | 0.87 (0.78 to 0.97) | 0.013 | 0.88 (0.79 to 0.98) | 0.024 | |

Per 1 ng/mL MDC, per 10 ng/mL sE-selectin, tPAI-1.

X2 (5)=15.69, p=0.008. Hosmer–Lemeshow's goodness-of-fit test p=0.25.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve=0.728 (0.623–0.834).

*Adjusted for age at the CT and exposure group. MDC, macrophage derived chemokine; sE-selectin, soluble endothelial selectin; tPAI, total plasminogen activator inhibitor.

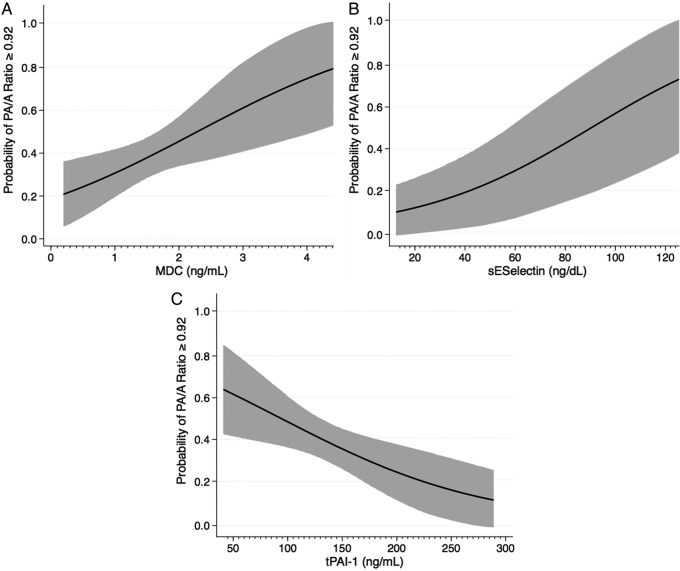

The probability of having a PA/A ratio ≥0.92 was determined for each of our three analytes when holding all other variables in the model constant (figure 2). The probability increased from 0.21 to 0.79 as the concentration of MDC increased from 0.2 to 4.41 ng/mL (figure 2A). The probability of an increased PA/A increased from 0.14 to 0.75 as the concentration of sE-selectin increased from 12.7 to 125.4 ng/mL (figure 2B). An increase in the concentration of tPAI-1 from 41.4 to 288.9 ng/mL decreased the probability of having an increased PA/A ratio from 0.63 to 0.11 (figure 2C). When using biomarkers to predict WTC-LI, MDC remains significant with an OR of 2.1, data not shown. However, sE-selectin and tPAI-1 were not significant predictors of WTC-LI.

Figure 2.

Probability plots. Probability of having pulmonary artery/aorta (PA/A) ratio≥0.92 over the range of macrophage derived chemokine (MDC) (A), soluble endothelial selectin (sE-selectin) (B) and total plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (tPAI-1) (C) are represented when adjusting for the covariates of exposure, and age. Plots express probability isopleths for the development of World Trade Center-Lung Injury (forced expiratory volume in 1 s loss) with all other covariates held constant.

Discussion

We have identified that biomarkers of cardiovascular risk, inflammation and metabolic syndrome expressed within 6 months of 9/11/2001 predict the development of WTC-LI. Vascular changes occur early in COPD, prior to the development of WTC-LI.10 In a recently published analysis of the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE)/COPDGene cohorts, in patients with moderate-to-severe disease, a PA/A>1 was significantly associated with COPD exacerbations.13 A unique advantage to observing the PA/A ratio by non-contrast CT is that it is a non-invasive mechanism that provides insight into the pulmonary and systemic circulation.17 18

In this nested case–control study of our well-phenotyped WTC exposed FDNY cohort, we found that an elevated PA/A≥0.92 was associated with an observed development of WTC-LI, with odds of 4.02. Early levels of MDC, sE-selectin and tPAI-1 showed the ability to predict PA/A≥0.92.

Recently, CT measurements of the PA/A have been associated with outcomes other than pulmonary hypertension. The ECLIPSE/COPDGene cohort examined patients with advanced disease, many requiring supplemental O2.13 Although our cohort's mean PA and A were similar to those measured in the ECLIPSE/COPDGene, 81% of the cohort did not meet the GOLD COPD criteria. Therefore, it was expected that the PA/A would be less than the previously reported ratios of 1. When comparing our cohort with the Framingham Heart Study, we found that our case mean PA/A and PA values are similar to their 90% upper limit of normal. Although we found a similar inverse relationship with PA/A and age, there were only weak associations with height and BSA.16 In a very recent study, an abnormal PA/A has been associated with increased mortality in patients with coronary artery disease.19 Our study would indicate that abnormalities in the PA/A may represent a marker of early vascular injury in particulate matter-related lung disease and is in line with these recent publications.

BWT was also found to be more prevalent in those with PA/A≥0.92. Our previous work has linked this indicator of proximal airway inflammation and/or remodelling with WTC-LI.1 Our new finding may show that BWT is related to early vascular changes. However, it is unclear what the temporal relationship is between BWT and vascular changes.

Our group and others have linked biomarkers of systemic inflammation and vascular disease with COPD. The proposed pathobiological mechanism of this relationship is related to inflammatory loss of lung parenchyma and vascular beds. COPD is a systemic process affecting not only the airways but also the lung parenchyma, vascular structures and other organ systems such as skeletal muscle and adipose tissue.20 Non-invasive biomarkers guiding management and prognostication in COPD are needed.21 22

We chose to study a limited number of biologically plausible vasoactive biomarkers, to examine the link between their expression in a serum soon after massive particulate matter exposure and PA/A. MDC, also known as CCL22, is an inflammatory mediator that has been linked to obstructive lung dysfunction by our laboratory and others.23 It is important in platelet activation and has been associated with a systemic vascular phenomenon.24 25 sE-selectin is a member of the selectin family of carbohydrate binding lectins, and is specifically produced by activated endothelial cells.26 It is one of the main endothelial neutrophil adhesion molecules and has been linked to poor CVD outcomes. Additionally, well-known metabolic risk factors for CVD are associated with an increase in the soluble form sE-selectin.27 28 tPAI-1, the main inhibitor of the plasminogen activator, has been associated with lung diseases,29 atherosclerosis, thrombosis and vascular remodelling.30–32 It has been analysed in pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure, although whether it is inhibitory or stimulatory in these disease states has yet to be elucidated and is under investigation.33 34

In our population, we found that elevated levels of MDC, sE-selectin were significantly associated with an increased PA/A ratio. tPAI-1 was inversely related to this ratio. These associations correlate with previous reports on CVD. This association is novel because it is the first time these biomarkers have been associated with a non-invasive marker of vascular injury in lung disease. However, in using biomarkers to predict WTC-LI, only MDC remained a predictive biomarker. This may indicate that sE-selectin and tPAI-1 may be involved with vascular remodelling after exposure, but may not be directly relate to the lung damage seen in those with WTC-LI. The population size may also have limited the ability to find significant differences in the two groups.

There are several limitations to this study. Understandably, this cohort of FDNY firefighters did not have pre-exposure serum banked for future analyses. We did achieve the next best option by obtaining serum samples within a few months postexposure. There were no unexposed or asymptomatic exposed controls in our study. Replication of these findings in other populations with and without particulate matter exposure will be important. We were able to obtain CT images on only 97 participants with the available serum. We do not have longitudinal follow-up data (FEV1, CTs, serum biomarkers) for additional correlation. Finally, we have no data on the prevalence of important comorbidities such as sleep apnoea, left heart failure and thromboembolic disease in this population. Thus, the finding linking an elevated PA/A to a decreased FEV1 may be influenced by the presence of these unaccounted for confounders.

In this nested case-cohort study, we were able to identify cardiovascular-related serum biomarkers drawn within 6 months of 9/11/2001 that predicted an abnormal PA/A ratio. The observation that biomarkers predict changes in PA/A and that PA/A was a non-invasive marker lung injury (FEV1 loss) in this postexposure population provides a novel association with well-characterised processes in vascular biology and inflammation secondary to particulate matter exposure. Importantly, these biomarkers were expressed during the early stages of WTC lung injury and reflect potential processes leading to disease susceptibility. This insight on protein expression and its relationship to FEV1 loss and vascular injury may guide future mechanistic and therapeutic studies in the field.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the firefighters and rescue workers for their participation in this study and for their selfless contributions.

Footnotes

Contributors: AN, MDW, EJS and DJP participated in the study conception and design. AN and EJS were the primary investigators. EJS, AN, SK and ALC were responsible for data collection. AN, EJS, FGG and SK were responsible for data validation. AN, EJS and SK participated in data analysis. AN, GCE and EJS undertook the statistical analysis. All authors participated in data interpretation, as well as the writing and revision of the report and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH-NHLBI K23HL084191(AN), NIAID K24A1080298(MDW), NIH-R01HL057879 (MDW), and NIOSH (U10-OH008243, U10-OH008242) and UL1RR029893 (DJP). This work was also partially funded by the NYU-HHC CTSI UL1TR000038 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: NYU and Montefiore IRBs.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Weiden MD, Ferrier N, Nolan A, et al. Obstructive airways disease with air trapping among firefighters exposed to World Trade Center dust. Chest 2010;137:566–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiden MD, Naveed B, Kwon S, et al. Cardiovascular biomarkers predict susceptibility to lung injury in World Trade Center dust-exposed firefighters. Eur Respir J 2013;41:1023–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naveed B, Weiden M, Kwon S, et al. Metabolic syndrome biomarkers predict lung function impairment: a nested case–control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:392–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nolan A, Naveed B, Comfort A, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers predict airflow obstruction after exposure to World Trade Center dust. Chest 2012;142:412–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zureik M, Benetos A, Neukirch C, et al. Reduced pulmonary function is associated with central arterial stiffness in men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:2181–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tockman MS, Pearson JD, Fleg JL, et al. Rapid decline in Fev1. A new risk factor for coronary heart disease mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151(2 Pt 1):390–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mannino DM, Thorn D, Swensen A, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPD. Eur Respir J 2008;32:962–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez-Roisin R, Drakulovic M, Rodriguez DA, et al. Ventilation-perfusion imbalance and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease staging severity. J Appl Physiol 2009;106:1902–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liebow AA. Pulmonary emphysema with special reference to vascular changes. Am Rev Respir Dis 1959;80(1 Pt 2):67–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbera JA, Riverola A, Roca J, et al. Pulmonary vascular abnormalities and ventilation-perfusion relationships in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149(2 Pt 1):423–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caplan-Shaw CE, Yee H, Rogers L, et al. Lung pathologic findings in a local residential and working community exposed to World Trade Center dust, gas, and fumes. J Occup Environ Med 2011;53:981–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King MS, Eisenberg R, Newman JH, et al. Constrictive bronchiolitis in soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. N Engl J Med 2011;365:222–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells JM, Washko GR, Han MK, et al. Pulmonary arterial enlargement and acute exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med 2012;367:913–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahammedi A, Oshmyansky A, Hassoun PM, et al. Pulmonary artery measurements in pulmonary hypertension: the role of computed tomography. J Thorac Imaging 2013;28:96–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fluss R, Faraggi D, Reiser B. Estimation of the Youden index and its associated cutoff point. Biom J 2005;47:458–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truong QA, Massaro JM, Rogers IS, et al. Reference values for normal pulmonary artery dimensions by noncontrast cardiac computed tomography: the Framingham Heart Study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5:147–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devaraj A, Wells AU, Meister MG, et al. Detection of pulmonary hypertension with multidetector Ct and echocardiography alone and in combination. Radiology 2010;254:609–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahammedi A, Oshmyansky A, Hassoun PM, et al. Pulmonary artery measurements in pulmonary hypertension: the role of computed tomography. J Thorac Imaging 2013;28:96–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakanishi R, Rana JS, Shalev A, et al. Mortality risk as a function of the ratio of pulmonary trunk to ascending aorta diameter in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 2013;111:1259–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gan WQ, Man SF, Senthilselvan A, et al. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax 2004;59:574–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koutsokera A, Stolz D, Loukides S, et al. Systemic biomarkers in exacerbations of COPD: the evolving clinical challenge. Chest 2012;141:396–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Celli BR, Locantore N, Yates J, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers improve clinical prediction of mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:1065–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perros F, Hoogsteden HC, Coyle AJ, et al. Blockade of Ccr4 in a humanized model of asthma reveals a critical role for Dc-derived Ccl17 and Ccl22 in attracting Th2 cells and inducing airway inflammation. Allergy 2009;64:995–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gear AR, Suttitanamongkol S, Viisoreanu D, et al. Adenosine diphosphate strongly potentiates the ability of the chemokines Mdc, Tarc, and Sdf-1 to stimulate platelet function. Blood 2001;97: 937–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golledge J, Clancy P, Moran C, et al. The novel association of the chemokine Ccl22 with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Am J Pathol 2010;176:2098–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roldan V, Marin F, Lip GY, et al. Soluble E-selectin in cardiovascular disease and its risk factors. A review of the literature. Thromb Haemost 2003;90:1007–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hwang SJ, Ballantyne CM, Sharrett AR, et al. Circulating adhesion molecules Vcam-1, Icam-1, and E-selectin in carotid atherosclerosis and incident coronary heart disease cases: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (Aric) Study. Circulation 1997;96:4219–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blann AD, Tse W, Maxwell SJ, et al. Increased levels of the soluble adhesion molecule E-selectin in essential hypertension. J Hypertens 1994;12:925–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sisson TH, Simon RH. The plasminogen activation system in lung disease. Curr Drug Targets 2007;8:1016–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flores J, Garcia-Avello A, Flores VM, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator plasma levels as a potential diagnostic aid in acute pulmonary embolism. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2003;127:310–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutte H, Mortensen J, Hag AM, et al. Limited value of novel pulmonary embolism biomarkers in patients with coronary atherosclerosis. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2011;31:452–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tashiro Y, Nishida C, Sato-Kusubata K, et al. Inhibition of Pai-1 induces neutrophil-driven neoangiogenesis and promotes tissue regeneration via production of angiocrine factors in mice. Blood 2012;119:6382–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawut SM, Barr RG, Johnson WC, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 are associated with right ventricular structure and function: the Mesa-Rv Study. Biomarkers 2010;15:731–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diebold I, Kraicun D, Bonello S, et al. The ‘Pai-1 paradox’ in vascular remodeling. Thromb Haemost 2008;100:984–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.