Abstract

Objective

National guidelines recommend ‘early’ coronary angiography within 96 h of presentation for patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTE-ACS). Most patients with NSTE-ACS present to their district general hospital (DGH), and await transfer to the regional cardiac centre for angiography. This care model has inherent time delays, and delivery of timely angiography is problematic. The objective of this study was to assess a novel clinical care pathway for the management of NSTE-ACS, known locally as the Heart Attack Centre-Extension or HAC-X, designed to rapidly identify patients with NSTE-ACS while in DGH emergency departments (ED) and facilitate transfer to the regional interventional centre for ‘early’ coronary angiography.

Methods

This was an observational study of 702 patients divided into two groups; 391 patients treated before the instigation of the HAC-X pathway (Pre-HAC-X), and 311 patients treated via the novel pathway (Post-HAC-X). Our primary study end point was time from ED admission to coronary angiography. We also assessed the length of hospital stay.

Results

Median time from ED admission to coronary angiography was 7.2 (IQR 5.1–10.2) days pre-HAC-X compared to 1.0 (IQR 0.7–2.0) day post-HAC-X (p<0.001). Median length of hospital stay was 3.0 (IQR 2.0–6.0) days post-HAC-X v 9.0 (IQR 6.0–14.0) days pre-HAC-X (p<0.0005). This equates to a reduction of six hospital bed days per NSTE-ACS admission.

Conclusions

The introduction of this novel care pathway was associated with significant reductions in time to angiography and in total hospital bed occupancy for patients with NSTE-ACS.

Keywords: HEALTH ECONOMICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Delivery of early coronary angiography for patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTE-ACS) remains a problem within the UK.

We describe the introduction of a clinical pathway aimed to facilitate early coronary angiography and reduced length of hospital admission for patients with NSTE-ACS.

Our ‘real world’ data demonstrates that this streamlined care pathway can dramatically cut inpatient waiting times for coronary angiography with a resultant reduction in length of hospital admission.

Importantly this is not randomised data. The study describes our management of patients with NSTE-ACS before and after the introduction of this clinical pathway. As with all observational studies it is open to residual bias and potential confounding.

Introduction

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) encompass a spectrum of clinical presentations that include ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-STEMI (NSTEMI), and unstable angina. In recent years, patients who present with STEMI have benefited from a shift from thrombolytic therapy to primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).1 2 The latest Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) data demonstrates that this change in practice has been implemented remarkably quickly across most parts of the UK so that the majority of patients with STEMI are now treated with primary PCI.3 Targets supported by the Health Care Commission based on time from symptom onset to opening of the infarct-related artery set a standard against which models of care for patients with STEMI are measured and these targets have driven reductions in treatment times and improved clinical outcomes.3

Non-ST elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS) accounts for a far greater proportion of ACS admissions than STEMI each year.3 NSTE-ACS is considered a ‘high-risk’ clinical condition, associated with 1 year mortality rates greater than or equal to those seen after STEMI.4 International treatment guidelines recommend that patients with NSTE-ACS are managed with immediate medical therapy followed by early coronary angiography (and PCI if appropriate) within 72–96 h of hospital admission,5 and within 24 h for the highest risk patients.5 Despite these guidelines recommending early invasive management of patients with NSTE-ACS, standard care pathways rarely achieve these evidence-based treatment timeframes.

The delivery of care for patients with NSTE-ACS has changed little in the past 10 years. Most patients with NSTE-ACS present to a hospital without a cardiac catheter laboratory where they wait for transfer to the regional interventional cardiac centre for coronary angiography.6 This model of care results in unacceptable delays to treatment7 which are detrimental to patient outcomes and which waste healthcare resources. A systematic approach to early diagnosis, risk stratification and ‘direct’ transfer to an interventional cardiac centre has the potential to minimise unnecessary delays for coronary angiography, to reduce hospital stays and to prevent recurrent ischaemic cardiac events in higher risk patients.

The London Chest Hospital is a regional interventional cardiac centre serving a population of approximately 1.8 million in North East London. The hospital provides coronary angiography, PCI and cardiac surgery for six district general hospitals (DGH) in the region. We have devised a new clinical pathway for the management of patients with NTE-ACS that built on our experience from developing a network-wide STEMI service. This new pathway known locally as the Heart Attack Centre Extension or ‘HAC-X’ service aims to transfer those patients with NSTE-ACS who can be diagnosed within 4 h of presentation directly from the ED to the regional interventional cardiac centre avoiding unnecessary admission to the local hospital.

This article represents a prospective study that monitored the implementation of this novel clinical HAC-X pathway for the management of patients with NSTE-ACS. The aim of the HAC-X pathway was to facilitate the early invasive management of patients with NSTE-ACS. Potentially this streamlined approach to NSTE-ACS management would represent a more efficient use of NHS resources.

Methods

We have undertaken a prospective observational study of the management of patients with NSTE-ACS treated at our institution between October 2009 and October 2010. This study period represents the last 6 months of our previous NSTE-ACS care model and the first 6 months of the new HAC-X pathway.

Study population

Patients were eligible for inclusion in this study if they presented to a DGH ED participating in the HAC-X project and were subsequently transferred to our institution for further management.

Inclusion criteria for the HAC-X clinical pathway (box 1) and therefore study inclusion criteria were an admission diagnosis of NSTE-ACS with chest pain within 24 h of presentation plus either an elevated blood troponin T or troponin I concentration, or ECG changes compatible with ischaemia (defined as ST-segment depression ≥1 mm or T-wave inversion ≥2 mm in two contiguous leads, or biphasic ST/T wave segments indicative of a critical stenosis in the left anterior descending artery). Patients were excluded if they had a contraindication to early interventional management including major medical comorbidity, unexplained anaemia (haemoglobin concentration <10 g/dL), acute renal failure, recent traumatic injury or loss of consciousness (except when secondary to cardiac arrhythmia), overt sepsis or unexplained hypoxia.

Box 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for HAC-X clinical pathway.

Inclusion criteria

Symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischaemia

With a positive troponin assay

OR ECG changes including:

ST depression;

T wave inversion in V1-4;

Dynamic T wave changes

Exclusion criteria

Unexplained anaemia (haemoglobin <10 g/dL)

Hypoxia

Acute renal failure

Loss of consciousness (unless secondary to cardiac arrhythmia)

Recent trauma

Overt sepsis

During the 12-month study period, 702 patients with NSTE-ACS were treated at our institution. These patients were divided into two groups for subsequent analysis; 391 patients treated before the instigation of the HAC-X pathway (pre-HAC-X), and 311 patients treated via the novel pathway (post-HAC-X).

Study protocol

The London Chest Hospital is a ‘stand-alone’ regional interventional cardiac centre. It has no onsite emergency department (ED) and only patients with suspected STEMI are admitted directly to the hospital. All patients with suspected NSTE-ACS must first be seen at a DGH before transfer.

During the first 6 months of the study period (pre-HAC-X) the model of care for patients with NSTE-ACS involved admission to their local DGH for ‘medical stabilisation’ pending availability of a bed at the regional interventional cardiac centre for transfer for coronary angiography (and/or PCI). Clinical instability prompted more urgent transfer and patients were usually transferred back to their local hospital for discharge following invasive cardiac treatment.

After the initiation of the HAC-X pathway in April 2010 (post HAC-X) patients diagnosed with NSTE-ACS in the DGH ED, and meeting the inclusion criteria for the HAC-X pathway (box 1) received protocol driven evidence-based medical therapy (box 2) and were transferred to our institution directly within 1 h of diagnosis. There was no requirement for ECG review or prior notification of the patient's transfer to our centre but clinical advice could be sought in cases of diagnostic uncertainty. If the admission diagnosis of NSTE-ACS was confirmed at our centre, coronary angiography was performed; unstable patients were taken directly for coronary angiography. Stable patients had coronary angiography scheduled for later the same day, or if the patient arrived outside of standard working hours, coronary angiography took place on the next available routine list. All subsequent cardiac care was undertaken at the regional cardiac centre. We aimed to discharge patients within 48 h of their admission. Patients requiring surgical revascularisation remained at our centre until surgery was performed.

Box 2. Evidence based immediate medical therapy for patients with NSTEMI treated via the HAC-X clinical pathway.

Immediate evidence based therapy given at DGH included

Aspirin 300 mg

Clopidogrel 600 mg

Fondaparinux 2.5 mg

Eptifibatide bolus (180 mg/kg) as long as no contraindications

Outcome measures

Our primary study end point was time to coronary angiography for patients with NSTE-ACS (defined as the time of registration at the DGH ED to beginning of the angiogram procedure). We also measured length of hospital stay (defined as the time from registration at the DGH ED to final hospital discharge). In addition, we have assessed the need for angiography and/or coronary revascularisation, along with discharge diagnosis of the post-HAC-X group.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data with a normal distribution are reported as mean±SD. Skewed data are reported as median and IQR. Categorical data are expressed as percentages. Continuous variables with a normal distribution were compared by Student's t test. Skewed data were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared by the χ2 or Fisher exact test. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

In total 702 patients with NSTE-ACS were treated at our institution during the study period (table 1). Three hundred and ninety-one (55.7%) patients were treated in the 6 months pre-HAC-X, and 311 (44.3%) patients were treated in the 6 months post-HAC-X.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the study cohort

| Variables | Pre-HAC-X n=391 |

Post-HAC-X n=311 |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.2±12.6 | 57.0±13.9 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.884 | ||

| Male (%) | 70.8 | 70.0 | |

| Female (%) | 29.2 | 30.0 | |

| Smoking status: | 0.009 | ||

| Current (%) | 18.2 | 29.6 | |

| Ex-smoker (%) | 30.4 | 31.9 | |

| Never (%) | 51.4 | 41.2 | |

| Diabetes: | 0.205 | ||

| Insulin requiring (%) | 6.1 | 9.7 | |

| Non-Insulin requiring (%) | 24.8 | 22.6 | |

| Not diabetic (%) | 69.1 | 67.7 | |

| Hypertension (%) | 62.7 | 59.7 | 0.241 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia (%) | 46.0 | 51.3 | 0.001 |

| Previous myocardial infarction (%) | 30.7 | 34.9 | 0.29 |

| Previous PCI (%) | 14.1 | 25.5 | <0.001 |

| Previous CABG (%) | 11.5 | 11.2 | 0.994 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) | 1.5 | 6.0 | 0.003 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 6.7 | 8.1 | 0.58 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; HAC-X, Heart Attack Centre-Extension.

Patients in the post-HAC-X group were younger (57.0 vs 65.2 years; p<0.001) and were more likely to be or have been smokers (58.8% vs 48.6%; p=0.009). Hypercholesterolaemia (51.3% vs 46.0%; p<0.001), peripheral vascular disease (6.0% vs 1.5%; p=0.003) and previous PCI (25.6 vs 14.1%; p<0.001) were also observed more frequently in the post-HAC-X group.

Outcome of invasive investigation

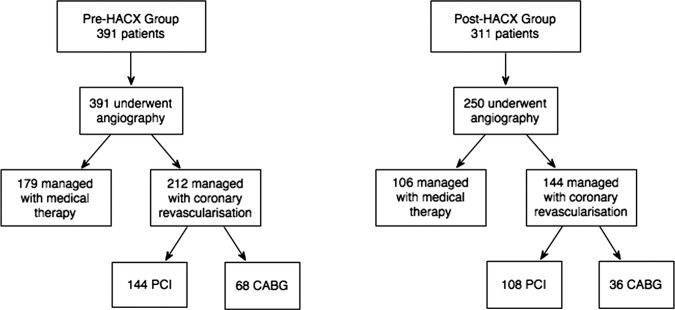

Pre-HAC-X patients had the diagnosis of NSTE-ACS confirmed by a local cardiologist prior to transfer. Therefore all of these patients underwent coronary angiography (figure 1). Of these, 212 (54.2%) patients subsequently underwent coronary revascularisation; 144/212 (67.9%) patients underwent PCI and 68/212 (32.1%) patients were referred for coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. 179 of 391 (45.8%) patients did not receive either PCI or CABG, but had coronary disease requiring ongoing medical therapy.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes treated before (Pre-HAC-X, Heart Attack Centre-Extension) and after (Post-HAC-X) the initiation of the HAC-X clinical pathway describing access to coronary angiography and subsequent management strategy. CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Post-HAC-X 250 of the 311 (80.4%) patients transferred to our centre by the new pathway underwent coronary angiography. Of these, 144/250 (57.6%) subsequently underwent coronary revascularisation; 108/144 (75.0%) patients underwent PCI and 36/144 (25.0%) patients were referred for CABG surgery, and 106/250 (42.4%) patients were treated with medical therapy alone.

Time to coronary angiography

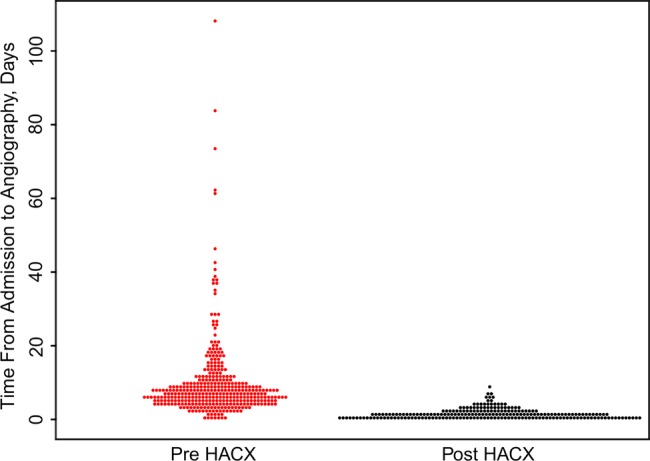

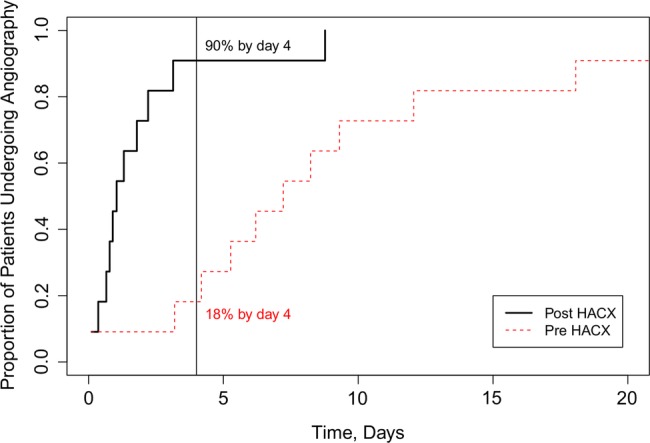

The initiation of the HAC-X pathway led to significant reductions in the median waiting time from DGH ED admission to coronary angiography for patients with NSTE-ACS. Pre-HAC-X time to angiography was 7.2 (IQR 5.1–10.2) days; post-HAC-X this had reduced to 1.0 (IQR 0.7–2.0) days (p<0.001; figure 2). Pre-HAC-X only 18% of patients with NSTE-ACS underwent coronary angiography within the recommended 96 h from presentation. Post-HAC-X 90% of patients underwent coronary angiography within this timeframe (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Bee swarm boxplot demonstrating the time the emergency departments admission to coronary angiography for patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes treated before (Pre-HAC-X, Heart Attack Centre-Extension) and after (Post-HAC-X) the initiation of the HAC-X clinical pathway. Each point represents the time taken to undergo coronary angiography for an individual patient.

Figure 3.

The proportion of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes undergoing coronary angiography within recommended 96 h of hospital admission before (Pre-HAC-X, Heart Attack Centre-Extension) and after (Post-HAC-X) the initiation of the HAC-X clinical pathway.

Length of hospital stay

Median length of hospital stay reduced significantly from 9.0 (IQR 6.0–14.0) days pre-HAC-X to 3.0 (IQR 2.0–6.0) days post-HAC-X (p<0.001). This equates to a saving of six hospital bed days per NSTE-ACS admission. As 311 patients with NSTE-ACS were treated according the HAC-X pathway during its first 6 months of operation we estimated that 1866 hospital bed days were saved during this period.

Clinical efficacy of HAC-X pathway

In total 85.5% of patients admitted directly via the HAC-X pathway had a cardiological diagnosis. NSTE-ACS was the discharge diagnosis for 235 (75.5%) of the 311 patients treated according to the HAC-X pathway. A further 31/311 (10%) patients had another cardiac cause for chest pain (including pericarditis or myocarditis) whereas 45/311 (14.5%) of patients had a non-cardiac cause for their symptoms.

Discussion

The introduction of the HAC-X pathway led to a significant decrease in time from hospital admission to coronary angiography for patients with NSTE-ACS. Furthermore, the proportion of patients with NSTE-ACS treated within the 96 h guideline target increased dramatically from 18% pre-HAC-X to 90% post-HAC-X. This novel clinical pathway facilitated the rapid, efficient management of patients with NSTE-ACS, which has translated into a two-thirds reduction in length of hospital stay.

Direct transfer of patients from the DGH to the regional cardiac centre has proved a far more streamlined approach to NSTE-ACS care. Not only was the length of hospital stay decreased, but all patients managed via the HAC-X pathway also avoided an unnecessary admission to their local DGH. The HAC-X pathway was only feasible because all parties involved (cardiac centre, DGHs and local healthcare commission) were motivated to contribute to the project. The benefit of the HAC-X pathway to the referring DGH is immediately evident. Direct transfer of patients with NSTE-ACS results in a huge reduction in ‘wasted’ hospital bed days. Furthermore, the HAC-X pathway has an additional cost benefit as it avoids local healthcare commissioners from having to fund two admission tariffs for the same index event. Prior to the initiation of the HAC-X the local healthcare commission was paying admission tariffs to the DGH and the regional cardiac centre. Alternative transfer strategies for patients with NSTE-ACS, such as regional transfer units,8 and same day ‘repatriation’ of patients to the referring hospital after PCI,9 have been described, and result in more efficient bed usage and reduced time to angiography in patients with NSTE-ACS. However, these management strategies require admission tariffs at the referring DGH and also the cardiac centre. The HAC-X service did require the cardiac centre to invest in more bed capacity that inevitably increased the cost of the pathway to the cardiac centre.

The success of this pathway, which aims to transfer patients to a specialist centre without admission to the local hospital is critically dependent on an accurate early diagnosis both for obvious clinical reasons and, in the UK, to facilitate transfer out of the ED within the 4 h target. Patients with NSTE-ACS form a heterogenous group yet the simple inclusion criteria for the HAC-X pathway of clinical symptoms of ACS plus either a positive point of care troponin assay or ECG changes consistent with myocardial ischaemia enabled an accurate diagnosis to be achieved in more than three-quarters of patients. This is comparable with diagnostic accuracy rates for patients delivered to Heart Attack Centres for acute STEMI management.

The proportion of patients undergoing coronary revascularisation post-HAC-X is in line with contemporary observational data of NSTE-ACS management.10 It is also similar to our historical revascularisation rates for patients with NSTE-ACS. Therefore, diagnostic criteria for the HAC-X pathway appear to perform as well the traditional model of care in their ability to identify patients with NSTE-ACS who will benefit from revascularisation. Importantly these diagnostic criteria identify these patients more quickly. This is key to the success of a model that aims to transfer patients direct from the ED to the cardiac centre in a systematic way.

The inclusion criteria for the pre-HAC-X and post-HAC-X cohorts are subtly different. Pre-HAC-X, patients with suspected NSTE-ACS were admitted to the DGH for medical stabilisation and cardiology review. If a local cardiologist confirmed the diagnosis of NSTE-ACS, and felt coronary angiography was appropriate, then the patients were transferred to the interventional cardiac centre for invasive investigation and management. Thus the pre-HAC-X cohort consisted only of patients with confirmed NSTE-ACS undergoing coronary angiography. The post-HAC-X cohort consisted of patients with suspected NSTE-ACS transferred directly from the ED. The diagnosis of NSTE-ACS was not confirmed until cardiology review at the cardiac centre, and inevitably the post-HAC-X cohort contained some patients who proved to have an alternate diagnosis and did not undergo coronary angiography.

Patients with a final non-cardiac diagnosis comprised about 15% of post-HAC-X patients. This group incorporated both patients who failed to meet the pathway's inclusion criteria who were transferred inappropriately and patients who had chest pain with an abnormal ECG but who were subsequently shown to have a negative troponin measured 12 h after onset of symptoms. In patients in whom myocardial infarction was suspected at presentation, the rapid access to coronary angiography and early demonstration of unobstructed coronary arteries allowed other cardiac diagnoses to be considered. In patients with a ‘non-coronary’ cardiac diagnosis, such as myocarditis, the early access to advanced non-invasive cardiac imaging at the cardiac centre undoubtedly streamlined their hospital admission, allowing earlier diagnosis and treatment. The small proportion of patients transferred with a non-cardiac diagnosis could be treated then discharged rapidly and safely from the cardiac centre, meaning that they were little burden on our resources. Although we strived to manage the vast majority of post-HAC-X patients exclusively at the cardiac centre, a small proportion of patients with a non-cardiac diagnosis were ‘repatriated’ to their district hospital for specialised further management of their condition.

It should be noted that direct comparison of pre-HAC-X and post-HAC-X patients is problematic. Inclusion to the study occurred once patients were transferred to the cardiac centre (for coronary angiography in pre-HAC-X patients, and with suspected NSTE-ACS for assessment and/or coronary angiography in post-HAC-X patients) rather than at the district hospital. As a result, a proportion of patients in the post-HAC-X group, after review at the cardiac centre were thought to have a non-coronary diagnosis, and did not undergo coronary angiography. Undoubtedly, before the initiation of the HAC-X pathway a number of patients were admitted to the district hospital with suspected NSTE-ACS, but this diagnosis was discounted after local cardiology review. These patients initially suspected to have NSTE-ACS, but later proven to have a non-coronary diagnosis, while still in their district hospital were not included in the pre-HAC-X cohort. Furthermore, there are important differences in the baseline demographics between the patient cohorts (table 1). Post-HAC-X patients were younger, more likely to be current smokers and more commonly had a history of hypercholesterolaemia, previous PCI and peripheral vascular disease. There are several potential explanations for these differences in cohort demographics. First, the presence of coronary risk factors or a history of previous PCI in patients presenting to the ED with chest pain is likely to stimulate early cardiac investigations. Inclusion criteria for the HAC-X pathway were diagnosis of NSTE-ACS while in the ED. Older patients with a paucity of coronary risk factors and no cardiac history may have had a delayed NSTE-ACS diagnosis meaning they could not be transferred directly from the ED via the HAC-X pathway. Second, patients with major medical comorbidities that precluded early angiography were specifically excluded from the HAC-X pathway. This is likely to introduce a degree of selection bias within the cohorts. The post-HAC-X cohort was generally younger and fitter, and this may have facilitated early discharge and a reduced length of hospital stay. Importantly, patients with NSTE-ACS with exclusions to the HAC-X pathway who were clinically unstable were always transferred to the interventional centre for further management, although these patients are not represented in this study.

Limitations of study

A number of limitations of this study are worthy of note; first, this was an observational study designed to evaluate the feasibility of a novel change in practice to reduce waiting times for coronary angiography in patients with NSTE-ACS. We did not collect clinical outcome data on the entire cohort and so can only speculate as to whether the initiation of this pathway provided clinical benefit to the patients presenting with NSTE-ACS. Second point of care troponin testing was not available in the ED until the initiation of the HAC-X pathway. Thus pre-HAC-X, patients will have undergone laboratory troponin testing whereas post-HAC-X patients underwent point of care troponin testing. These troponin assays, have differing sensitivity and specificities; for example point of care assays are designed to be highly sensitive, but may lack specificity compared with standard laboratory assays.11 This may predispose to the inclusion of patients with presumed NSTE-ACS who subsequently receive a non-cardiac diagnosis. Despite this limitation inappropriate transfers via the HAC-X pathway were infrequent. The HAC-X clinical pathway was designed to identify patients with NSTE-ACS while they remained in the ED. There are patients with suspected NSTE-ACS with an initially normal ECG and negative point of care troponin that develop ECG abnormalities or a positive troponin assay later in their hospital admission. Thus some patients with NSTE-ACS continued to be admitted to the DGH even after the initiation of the HAC-X pathway. Patients with NSTE-ACS admitted to the DGH, in the post-HAC-X era were managed in a similar fashion to pre-HAC-X patients, with medical stabilisation and transfer to the interventional centre once a bed became available. We have not collected data on this small group of patients. We do not know how the inclusion of these patients may have affected our results. Third, two of the six DGH's served by the London Chest Hospital have on-site cardiac catheterisation laboratories offering diagnostic coronary angiography but not PCI. Potentially, a small number of patients with suspected NSTE-ACS could have undergone diagnostic coronary angiography locally and then either been discharged if no coronary revascularisation was indicated or referred directly for coronary surgery. As patient data for this study were collected only after referral for coronary angiography and/or PCI at the interventional centre these patients with NSTE-ACS bypassed study enrolment and thus are not represented within the study cohort. However, we believe that the standardised transfer criteria for patients with NSTE-ACS central to the HAC-X pathway would make DGH admission and local angiography for patients with NSTE-ACS less common in the post-HAC-X period. Finally, the cardiac centre increased bed capacity, providing a dedicated six bed ward for patients admitted via the HAC-X pathway. The small increase in the total bed capacity of the hospital coupled with more efficient utilisation of inpatient beds allowed the HAC-X pathway to function. Potentially, these changes may confound our results, as they may influence time to coronary angiography and length of hospital stay.

The future

Delivery of coronary angiography within 96 h for patients with NSTE-ACS admitted to hospitals without facilities for invasive cardiac investigations is challenging. The HAC-X pathway is effective in identifying patients with NSTE-ACS for transfer directly to the regional cardiac centre avoiding unnecessary delays in treatment. Use of this model, modified according to local circumstances, could be applied nationally to streamline the management of patients with NSTE-ACS. The investment required for ‘HAC-X’ beds would be more than offset by the resulting savings in hospital bed days.

Conclusion

The introduction of this novel care pathway was associated with significant reductions in time to angiography and in total hospital bed occupancy for patients with NSTE-ACS. We have demonstrated its feasibility in routine clinical practice so this model could be used more widely to streamline the management of patients with NSTE-ACS.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SMG and AKJ conceived and designed the study. SMG, MJL, DAJ, EF, SC, ZB and RAA acquired the data. SMG, MJL, DAJ, and AKJ analysed and interpreted the data. SMG and MJL carried out statistical analysis. SMG, MJL, RAA, AW and AKJ drafted the original manuscript. SG, MJL, DAJ, AW, SC, EJS, RAA, CK, AM, MTR and AKJ critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: City and East REC.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Keeley E, Boura J, Grines C. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet 2003;361:13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van De Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force on the Management of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2008;29:2909–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project: How the NHS cares for patients with heart attack London, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen L, O'Donnell CJ, Camargo CJ, et al. Comparison of long-term mortality across the spectrum of acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 2006;151:1065–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamm C, Bassand J, Agewall S, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011;32:2999–3054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellenger N, Eichhofer J, Crone D, et al. Hospital stay in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Lancet 2004;363:1399–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CHD Collaborative. National Interhospital Transfer Audit. Presented at theCHD national transfer meeting 2004 and the British Cardiac Society annual meeting2004. http://www.heart.nhs.uk

- 8.Bellenger N, Wells T, Hitchcock R, et al. Reducing transfer times for coronary angiography in patients with acute coronary syndromes: one solution to a national problem. Postgrad Med J 2006;82:411–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen J, Klow N, Johansen O. Safe and feasible immediate retransfer of patients to the referring hospital after acute coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary angioplasty for patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2013;2:256–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zia M, Goodman S, Peterson E, et al. Paradoxical use of invasive cardiac procedures for patients with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction: an international perspective from the CRUSADE Initiative and the Canadian ACS Registries I and II. Can J Cardiol 2007;23:1073–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bock J, Singer A, Thode HJ. Comparison of emergency department patient classification by point-of-care and central laboratory methods for cardiac troponin I. Am J Clin Pathol 2008;130:132–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.