Abstract

Background

Previous qualitative research has examined male sex workers in the Czech Republic, but this mapping study is the first to investigate male sex work in a quantitative research design and focus on the mental health of these sex workers. This study also examines male sex workers’ mental health problems in relation to their sexual identity or orientation.

Material/Methods

A sample of Czech male sex workers (N=40) were examined on a range of sexual and psychological variables using a quantitative survey administered face-to-face. The study employed locally validated versions of Beck’s Depression Inventory and Zung’s Self-Report Anxiety Scale.

Results

The results indicate that for homosexuals, working as a male sex worker is not related to any serious mental health problems. However, those identifying as heterosexual and bisexual more frequently reported symptoms of depression and bisexuals showed significantly more anxiety.

Conclusions

These findings suggest sexual identity is an important issue to consider when addressing the mental health needs of this population.

MeSH Keywords: Anxiety, Depression, Sex Workers

Background

The Czech Republic is among the more sexually tolerant countries in Europe and because prostitution is decriminalized and wages are low, the country has also become a popular sex tourism destination among foreigners seeking sex with men [1]. This reputation is maintained by an aggressive gay pornography industry that markets Czech boys as sex objects throughout Europe and North America and beyond. For many young men, this type of work is a means of survival and it is seen as easy money, so it is attractive to any young man who finds himself in financial difficulty, whether gay, straight, or bisexual.

The main purpose of this study was to investigate the extent to which male sex workers experience psychological distress in the form of mood or anxiety disorders. The relationship between sex work and poor mental health among female sex workers has long been established, with studies finding as many as two-thirds of these women have symptoms of PTSD, in addition to increased depression [2]. Problems with substance abuse are also common [3]. Many of these symptoms are the result of the high proportion of female sex workers who are victims of human trafficking, but even in studies where the majority of participants were engaged in sex work of their own volition, many symptoms of mental illness are still reported [4]. Approximately 1 in 5 female sex workers report symptoms of clinical depression [5] and they also have higher rates of suicide [6]. Less research has focused on the mental health issues of male sex workers, with the focus being traditionally on HIV transmission, as detailed in Aggleton’s comprehensive review [7]. This review does suggest, however, that sexual identity plays a key role in the overall psychological well-being of the male sex worker.

In previous research regarding sexual identity among male sex workers, researchers in the USA typically find a high percentage of bisexuals in their samples, ranging from 20% [8] to nearly 40% [9,10]. Studies of female prostitutes in the Czech Republic have also found a much higher incidence of bisexuality among female sex workers [11] than in the general population [12]. Half of all female sex workers reported same-sex sexual experience, 6% considered themselves lesbian, and 13% considered themselves bisexual [11]. For this reason, we expect our findings will support the anecdotal evidence from qualitative research [1] that the percentage of bisexual males who are engaging in sex work in the Czech Republic is disproportionately larger than in the general population.

Recent studies that considered male sexual identity in the general population have found a high level of sexual compulsivity in both gay and bisexual men [13,14]. Sexual compulsivity has long been associated with psychological distress, such as mood and anxiety disorders [15]; therefore, we consider sexual identity as an important mediating variable to consider when assessing the mental health of sex workers.

Material and Methods

The study was conducted in cooperation with the Sexology Institute of the 1st Medical Faculty, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic and was funded by the University of New York in Prague.

The sample was collected in 2 phases: the first by contacting internet escorts offering their services in Prague, and the second through repeated site visits to various bars and clubs that cater exclusively to male sex workers (MSW) and their clients. This was in order to obtain the broadest picture of MSW in the Czech Republic (although participants in our sample came from regions across the country, MSW typically relocate to Prague, as it is the center of the sex industry). A total of 40 MSW completed the survey instrument and had a mean age of 23.5 (SD=3.5).

The survey contained several demographic questions, including sexual orientation, sexual behavioral reports regarding sexual activity with their partners as well as casual sex, modeled after a national study of sexual behavior [12], as well as their experiences as MSW modeled after previous studies of female sex workers in the Czech Republic [11]. We measured depression using the Czech-validated version of Beck’s Depression Inventory [16] and anxiety symptoms using the Czech-validated version of Zung’s Self-Report Anxiety Scale [17].

The sample of internet escorts was obtained by contacting men who maintain escort profiles on the gay social networking site www.gayromeo.com, which is the main site of its kind in the Czech Republic, with more than 200 escort profiles for the Prague region. The escorts were contacted via their profile by logging onto the site at 6 random times (evenly distributed across morning, afternoon, and evening in order to reach a broader range of MSW). In each case, a request for their participation in the study was sent to the first 5 users returned in a random search of users currently online. From the 30 escorts who were originally contacted, subjects were asked if they had had at least 1 client in the past month in order to qualify them for the research, of which 3 did not. Thus, of the 27 eligible for the study, 20 agreed to participate and meet with the principal investigator at a location of their choice to complete the survey. This resulted in a response rate of 74% for this method of sampling.

MSW in bars/clubs were recruited during a 3-month period in 2011 in 3 Prague bars/clubs selected because they cater exclusively to MSW and their clients. The visits were during both daytime and nighttime opening hours, and on each occasion the researcher approached all of the MSW present at the time to inform them of the possibility of participating in the research. The researcher then agreed on a time to meet later in a public place of their choosing, where they would complete the survey. In total, 25 MSW were approached and all agreed to schedule a follow-up meeting, but only 20 of these participants actually arrived at their appointment and completed the survey, resulting in a response rate of 80% for this method of sampling.

All participants from both groups chose to meet to complete the survey in a restaurant or cafe. When the MSW arrived, they were informed of the nature of the study and gave consent to participate. The paper-based survey took approximately 1 hour, and after they completed it, they sealed it in an envelope provided and received compensation of 500 CZK (approximately 20 EURO) for their participation.

Results

The participants were all similar in regards to demographic variables such as education (all had completed high school) and childhood sexual abuse, which was reported by 5% of respondents, consistent with the prevalence rate in the general population [12]. The subjects self-identified their sexual identity as heterosexual (n=17), homosexual (n=9), or bisexual (n=14); all subjects selected only 1 orientation. Self-reports of sexual identity were further confirmed by the responses to the question about their relationships and casual sexual encounters, all of which were consistent with their reported sexual identity.

Overall, 43% of respondents reported at least mild symptoms of depression and 18% reported symptoms of anxiety. Homosexuals reported the fewest symptoms, with a third reporting mild depression and none reporting any anxiety, while heterosexuals reported the most depression and bisexuals reported the most anxiety (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sexual identity of the male sex workers with percent of respondents reporting clinical levels of depression (Becks >10) and anxiety (Zung’s >45).

| Homosexual | Bisexual | Heterosexual | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 33% | 42% | 47% |

| Anxiety | 0% | 28% | 17% |

Because we predicted that psychological distress would be mediated by the sexual identity of the MSW, Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to test for significant differences between these groups for depression and anxiety. A non-significant trend for depression was observed with lower scores for homosexuals and higher for heterosexuals and bisexuals, but the variability within groups was too great to draw firm conclusions.

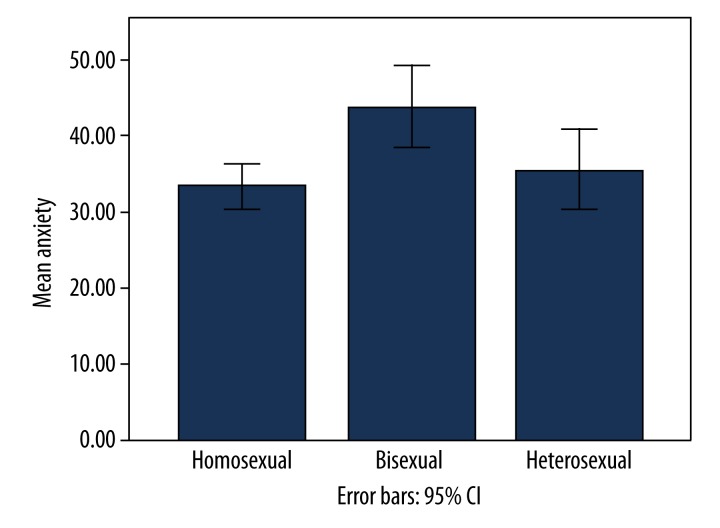

For the significant effect of anxiety, H (2)=9.71, p=.008, further post-hoc Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare bisexuals to both homosexuals and heterosexuals, using the Bonferroni correction (α=0.017, 2-tailed). Bisexuals showed significantly more general symptoms of anxiety than homosexuals (U=14.50, z=−2.96, p=0.002) and heterosexuals (U=51.50, z=−2.48, p=0.012). The results of this statistical analysis can be found in Figure 1. SPSS for Windows version 18 was used for all analyses.

Figure 1.

Male sex workers (N=40) scores on Zung’s Self Report Anxiety Scale, with scores of 45 or greater indicating clinically significant levels of anxiety.

Discussion

In our sample, the majority of male sex workers investigated were heterosexual or bisexual, not homosexual. Homosexuals offering sexual services in this sample did so exclusively via the internet, whereas heterosexuals were more likely to be found in the clubs where clients go to seek out these services. Bisexual men offered their services on the internet and in bars and clubs. Future research should investigate the reasons for this disparity.

Although great care was taken that any man engaged in sex work at the time had a chance to be selected for the study and response rates were high, it is never possible to obtain a representative sample with this type of population, preventing formation of firm conclusions about the exact percentages of gay-for-pay sex workers in the Czech Republic, although our percentages are also similar to that of previous research [8–11].

Many of these bisexual men reported levels of anxiety that can be classified as moderate to severe, much higher than that reported by their homosexual and heterosexual peers.

Nothing in the study suggested an alternative explanation for these differences in negative outcomes other than their sexual identity.

One interpretation of these results is that these bisexuals are in fact ego-dystonic homosexuals, resulting in increased stress and leading to greater symptoms of anxiety. This would be consistent with the finding that homosexuals who had previously identified as bisexuals were consistently less positive about their sexual identity and less comfortable with others knowing their identity than those who developed a homosexual identity directly [18]. Bisexual men have also been found to hold more homophobic attitudes, and perceive others as less accepting of homosexual activity than do homosexual men [19]. Previous research has also suggested increased depression and anxiety are more typical of bisexuals who later move towards identification as homosexual (approximately two-thirds of a sample of over 500 American bisexuals), than among those whose bisexual identity remained stable [20]. This could partly explain our findings, but a longitudinal study would be necessary to substantiate this hypothesis of ego-dystonic homosexuality, and to assume this to be the only reason would likely be an oversimplification.

Another explanation for anxiety in bisexual male sex workers may come from the general theory of minority stress [21]. Because homosexuality and bisexuality are viewed less favorably by society [22], those individuals who identify with these groups have increased stress due to the vigilance necessary to deal with this prejudice. However, this effect is reduced among people who make a positive identification with others in their group and take advantage of the extra support their community offers. For bisexuals, seeking support can be a catch-22 since the dominant heterosexual culture still rejects them by grouping them together with homosexuals [23], while the gay community may regard them as in denial about their homosexuality. Further ethnographic research on the interpersonal dynamics between the sex workers, especially in these clubs, may provide a clearer picture of how they view their own sexual identity and how they want to be viewed by others.

It seems that in our sample, these bisexual male sex workers may fear that they would be ostracized by their heterosexual peers as being homosexuals if it were discovered that they engage in non-commercial sex with men, while at the same time they may distance themselves from the gay community by emphasizing their desire for sex with women and playing a macho and homophobic role. It would therefore seem that their bisexual identity offers them none of the support of belonging to a sexual minority, but incurs the greatest prejudice against them. It remains to be established if this is due to the low number of bisexuals in the Czech population [12], the lack of organizations supporting bisexuals in the Czech Republic, or perhaps because bisexuals rarely share their identity in the same way as homosexuals. It could be this self-imposed isolation from other self-identified bisexuals leads to their high degree of alienation and anxiety.

This raises several important factors to consider for future studies of male sex workers. It is essential to assess their attitudes towards their own sexual identity, establish the attitudes towards homosexuality and bisexuality in the general cultural context of the research and for the individual in terms of internalized homophobia. It is also important to establish the extent of LGBT groups or services provided for and utilized by bisexual sex workers and their attitudes towards these groups.

Conclusions

Our study supported our main hypothesis, that sex work can be associated with mental health problems, but this is mediated by the sexual identity of the sex worker. These findings suggest the issue of conflict over sexual identity is an important issue to consider when addressing the needs of these male sex workers in general, as well as the understanding that bisexual identity can be a simple predictor of other problems when working with these sex workers individually. In conclusion, for homosexuals engaging in sex work in the Czech Republic, the risks to their psychological health are not as extreme as for heterosexuals and bisexuals.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Hall TM. Forms of transactional sex in Prague among young men who have sex with men (1999–2004) Czech Sociol Rev. 2007;43:89–109. [Google Scholar]

- 2.White K. Posttraumatic stress disorder found to be common among prostitutes. J Womens Health. 1998;7:943. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roxburgh A, Degenhardt L, Copeland J. Posttraumatic stress disorder among female street-based sex workers in the greater Sydney area, Australia. BMC Psychiatry. 2006;624:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rössler WW, Koch UU, Lauber CC, et al. The mental health of female sex workers. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122:143–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chudakov B, Ilan K, Belmaker RH, Cwikel J. The motivation and mental health of sex workers. J Sex Marital Ther. 2010;28:305–15. doi: 10.1080/00926230290001439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ling DC, Wong WW, Holroyd EA, Gray S. Silent killers of the night: An exploration of psychological health and suicidality among female street sex workers. J Sex Marital Ther. 2007;33:281–99. doi: 10.1080/00926230701385498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aggleton P, editor. Men who Sell Sex: International Perspectives on Male Prostitution and HIV/AIDS, London. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MD, Gov C, Seal DW. Agency based male sex work: a descriptive focus on physical, personal, and social space. J Mens Stud. 2008;16:193–210. doi: 10.3149/jms.1602.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boles J, Elifson KW. Sexual Identity and HIV: The Male Prostitute. J Sex Res. 1994;31:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross MW, Timpson SC, Williams ML, et al. Stigma Consciousness Concerns Related to Drug Use and Sexuality in a Sample of Street-Based Male Sex Workers. Int J Sex Health. 2007;19:57–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zikmundová M, Weiss P. [Private sexual life of female prostitutes]. Ceska Slov Psychiatr. 2004;100:66–72. [in Czech] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss P, Zvěřina J. [Sexual behavior in the Czech Republic, the situation and trends]. Prague, Portal: 2001. [in Czech] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parsons J, Kelly B, Bimbi D, et al. Explanations for the origins of sexual compulsivity among gay and bisexual men. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37:817–26. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly B, Bimbi D, Nanin J, et al. Sexual compulsivity and sexual behaviors among gay and bisexual men and lesbian and bisexual women. J Sex Res. 2009;46:301–8. doi: 10.1080/00224490802666225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black DW. Compulsive sexual behavior: A review. J Psychiatr Pract. 1998;4:219–30. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preiss M, Vacíř K. [Beckova sebeposuzovací škála depresivity]. Psychodiagnostika, Praha: 1999. (BDI-II translation) [in Czech] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filip V. [Praktický manuál psychiatrických posuzovacích stupnic]. Psychiatrické centrum, Praha: 1997. (Zung’s SAS translation) [in Czech] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosario M, Schrimshaw E, Hunter J, Braun L. Sexual identity development among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Consistency and change over time. J Sex Res. 2006;43:46–58. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stokes J, Vanable P, McKirnan D. Comparing gay and bisexual men on sexual behavior, condom use, and psychosocial variables related to HIV/AIDS. Arch Sex Behav. 1997;26:383–97. doi: 10.1023/a:1024539301997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stokes J, Damon W, McKirnan DJ. Predictors of movement toward homosexuality: A longitudinal study of bisexual men. J Sex Res. 1997;34:304–12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:647–97. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steffens M, Wagner C. Attitudes toward lesbians, gay men, bisexual women, and bisexual men in Germany. J Sex Res. 2004;41:137–49. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eliason M. The prevalence and nature of biphobia in heterosexual undergraduate students. Arch Sex Behav. 1997;26:317–26. doi: 10.1023/a:1024527032040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]