Abstract

Patient: Male, 58

Final Diagnosis: Intrahepatic splenosis

Symptoms: —

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Hepatectomy

Specialty: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Intrahepatic splenosis (IHS) is the autotransplantation of splenic tissue that mostly develops after abdominal injury and is often misdiagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) because of similarities in radiological features. We had an opportunity to treat an extremely rare case of intrahepatic splenosis, which were found in a patient without any history of splenic injury. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the world.

Case Report:

A 58-year-old man with chronic hepatitis C was referred to our hospital for further examination of liver function abnormality. Abdominal ultrasonography incidentally revealed a low echoic tumor in the posterior segment of the liver, with high echoic capsule, which is possibly different from tumor capsule of HCC, known as halo. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography and gadoxetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging showed that the tumor had an inhomogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase and diminished enhancement in the equilibrium phase, diagnosed as HCC. The patient underwent right lateral segmentectomy of the liver, and histopathological study confirmed a diagnosis of intrahepatic splenosis.

Conclusions:

This case presents a new understanding of IHS in a patient without any splenic injury. We also focused on the differences in echo patterns of the tumor capsule between HCC and IHS, which can be used to efficiently diagnose IHS.

MeSH Keywords: Hepatitis, Chronic, Liver Neoplasms, Splenosis

Background

Splenosis is the heterotopic autotransplantation of splenic tissue throughout the peritoneal cavity, which frequently seeds onto exposed vascularized peritoneal surfaces in up to 67% of patients following splenic trauma or surgery [1,2]. However, there are few reports in the literature regarding intrahepatic splenosis (IHS), which can be mistaken for a hepatic tumor, and surgical intervention has been reported to be unnecessarily performed to arrive at a correct diagnosis [3–5]. We treated a chronic hepatitis C patient with IHS but no history of splenic trauma or surgery, who was preoperatively diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Here, we summarize the clinical course and radiological findings of our patient and discuss possible causes of this lesion. We also include a literature review.

Case Report

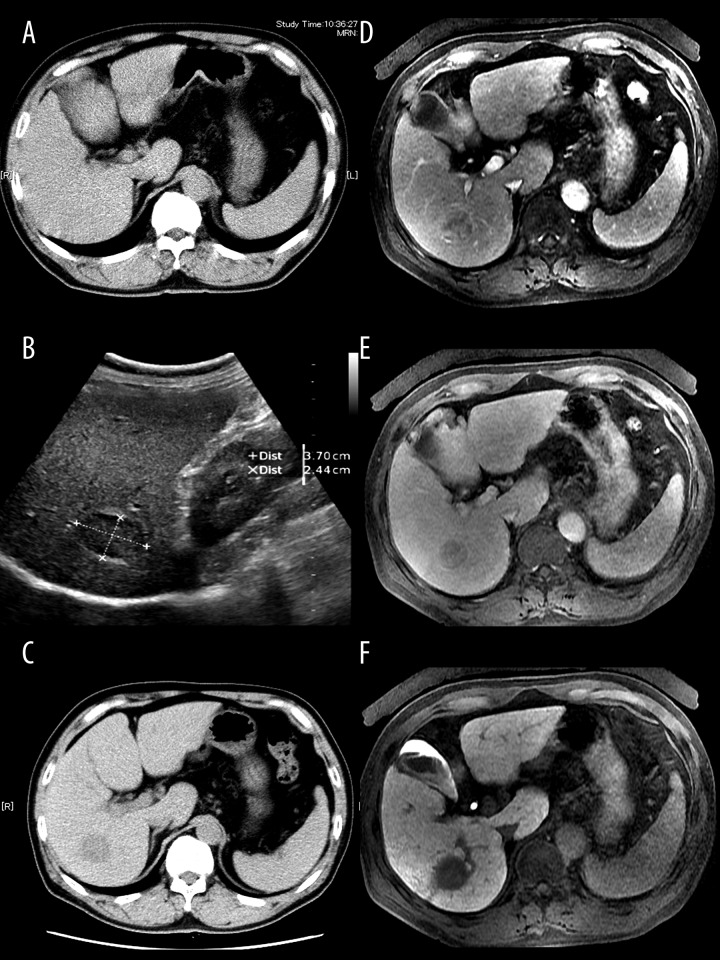

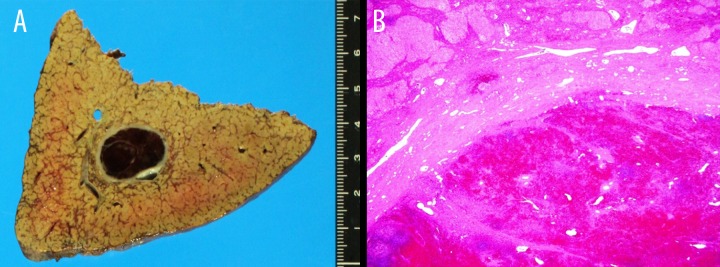

A 58-year-old man was referred to our hospital for further examination of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection because of elevated liver enzymes. He had a medical history of hypertension, but not of abdominal trauma, and his family history was non-specific. Since diagnosed as a carrier of HCV 10 years before, our patient underwent regular medical examinations every few years in a private hospital, which included ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), and positron emission tomography (PET), but he was never treated with anti-HCV agents. His last routine abdominal CT 4 years ago indicated no hepatic lesions (Figure 1A). Liver function test and platelet count 1 year ago were within normal ranges [aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 19 IU/l; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 23 IU/l; prothrombin time (PT), 88%; platelet count, 11.0×104/μl]. On his first visit to our hospital, the patient had no primary complaints, and physical examination results were unremarkable. However, a blood examination revealed slightly elevated levels of hepatic enzymes (AST, 144 IU/l, ALT, 118 IU/l) and α-fetoprotein (24.9 ng/ml) and decreased PT (79%) and platelet number (6.5×104/μl). Serology analysis was positive for HCV antibody (Ab), but negative for the hepatitis B virus surface antigen. Indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min was 11% and the Child-Pugh score was 5. Abdominal US incidentally revealed a low-echoic lesion with a 37-mm diameter and a hyperechoic rim of the right lobe of the liver (Figure 1B). Abdominal contrasted CT revealed a well-circumscribed, low-density mass measuring 36×32 mm in the subcapsular region of the posterior segment of the liver (Figure 1C). A dynamic study showed that the lesion had slightly inhomogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase and diminished enhancement in the equilibrium phase. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed hyperintensity of the lesion on T2-weighted images. The lesion had the same enhancement behavior on gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI (Gd-EOB-MRI) as in the dynamic CT study (Figure 1D, 1E). In the Gd-EOB-enhanced hepatobiliary phase MR image at 20 min, the hepatic lesion was clearly hypointense compared with the surrounding liver parenchyma (Figure 1F). On the basis of characteristic enhancements of the CT and Gd-EOB-MRI findings, HCC could not be ruled out; therefore, we performed a right lateral segmentectomy of the liver. During surgery, the external liver surface was slightly rough and solid, suggesting liver cirrhosis. Serial sections of the resected liver revealed an, encapsulated, dark red mass, 3.9×3.0 cm in size, embedded in the cirrhotic parenchyma (Figure 2A). A pathological examination demonstrated lymphoid follicular aggregates, a sinusoidal structure, and small fibrous bands from the outer capsule resembling trabeculae (Figure 2B). The histological findings confirmed that the lesion was composed of typical splenic tissue. Moreover, some erythroblasts were found in the ectopic splenic tissue within the liver, suggesting splenic extramedullary hematopoiesis. The patient’s clinical course after surgery was uneventful and he was discharged on postoperative day 16. Since the surgery, the patient has continued anti-HCV therapy and no new hepatic lesions were detected at a 1-year follow-up.

Figure 1.

Imaging of IHS in the patient. Abdominal plane computed tomography (CT) revealed a low-density mass in the posterior segment of the liver (C), whereas CT imaging 4 years previously detected no abnormal lesions (A). Ultrasonography revealed a hypoechoic heterogeneous mass 37×24 mm in size, with a hyperechoic rim in the right lobe of the liver (B). A dynamic study using gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI revealed slightly inhomogeneous enhancement of the lesion in the arterial phase (D) and diminished enhancement in the equilibrium phase (E). In the hepatobiliary phase, the lesion become hypointense compared with the surrounding liver parenchyma (F).

Figure 2.

(A) An encapsulated dark red mass was embedded in the cirrhotic liver parenchyma. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the lesion showed sinusoidal structures and lymphoid follicular aggregates with well-developed fibrous capsules with many small vascular channels.

Discussion

IHS is an extremely rare autotransplantation of viable splenic cells through the portal vein into the liver [6]. There are fewer than 20 reported cases of IHS in the English-language literature [5] and all had past medical histories of splenic rupture by trauma or underwent splenectomy. To the best of our knowledge, the present report is the first to describe a case of IHS without a history of splenic trauma or surgery. Hence, this case presents a new concept of autotransplantation of splenic tissue migration to the liver without splenic injury or surgery.

Splenosis is recognized as the heterotopic autotransplantation of splenic tissue following splenic trauma or surgery, where the disrupted splenic fragments seed the peritoneal surface, acquire a vascular supply, and become clinically evident as a result of regrowth at the implantation sites. Histologically, splenosis usually has no hilus and its blood supply is derived from surrounding tissues and vessels. Such implants are rarely of clinical significance and are often incidentally detected at autopsy or during abdominal surgery [7]. However, IHS is not widely recognized by most physicians; therefore, its incidence may be underestimated. Splenosis can occur with either single or multiple nodules, upward to 400 in some cases, and found throughout the peritoneal cavity but most often in the mesentery and omentum of the peritoneum [8]. Extraperitoneal locations of fragment growth, such as the retroperitoneal, thoracic, subcutaneous, and intrahepatic regions, have rarely been reported in cases of severe or multiple organ injuries with splenic rupture [9].

Splenosis should be distinguished from an accessory spleen, which is a congenital condition caused by embryologic failure of the fusion of the splenic primordium characterized by a dense, syncytial-like, mesenchymal thickening of the dorsal mesogastrium during fetal development [10]. Splenosis is different from an accessory spleen in many aspects, such as the amount of ectopic splenic tissue, common sites, histological findings, and blood supply [8]. An accessory spleen is usually solitary, but rarely exceeds 6 in number, and is most commonly located on the left side of the dorsal mesogastrium in the region of the splenopancreatic or gastrosplenic ligaments. Histologically, accessory spleens resemble the normal spleen, which contains a hilus, and always receive a blood supply from branches of the splenic artery. We reasonably assumed that our patient was not a case of an accessory spleen because he had no abnormal hepatic mass 4 years before, further indicating that the lesion was recently acquired.

The mechanism of splenic autotransplantation and regeneration is not well understood. Previous reports state that IHS displays 2 interesting characteristics. First, the latency period between splenic injury and IHS discovery/diagnosis appears to be relatively long, with an average duration of 28.2 years (range, 15–46 years) in 19 reported cases. Second, in more than half of the reports, IHS was associated with chronic hepatitis C or B infection [11,12]. On the basis of the susceptibility of the liver to splenic erythropoiesis and the inevitability of hypoxia caused by aging and pathological changes, Kwok et al. [6] hypothesized that 2 events can promote IHS development: (1) the migration of erythrocytic progenitor cells through the portal vein following traumatic splenic rupture and (2) erythropoiesis induction by local hypoxia of the liver. In the present case, our patient had no abnormal hepatic lesions at the last routine imaging performed 4 years before; however, his liver function worsened since an examination 1 year ago, indicating that his chronic HCV infection may have progressed in the meantime. His clinical course supports the hypothesis that erythropoiesis induced by local hypoxia of the liver with progression of chronic hepatitis C may trigger the rapid growth of splenic implants.

IHS often complicates the diagnosis of a hepatic lesion, thus many cases may be misdiagnosed as hepatic tumors, such as in HCC [1,3,4], metastatic tumors [13], or neuroendocrine neoplasms [14]. The primary reason for misdiagnosis is that IHS often develops in patients with chronic hepatitis, and the radiographic features are quite similar to those of HCC, showing early enhancement in the arterial phase and washout in the equilibrium phase [3–5]. Standard imaging modalities, such as CT or/and Gd-EOB-MRI, often cannot differentiate IHS from HCC. Unfortunately, in cases misdiagnosed as HCC, liver resection was often performed [3–5,13,14].

For a differential diagnosis of IHS among various hepatic lesions, De Vuysere et al. [15] reported that the administration of super-paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO), which is taken up by reticuloendothelial cells in the liver and spleen, presents a novel technique for the diagnosis of splenosis. According to literature, intrahepatic splenic nodes remain hyperintense on imaging relative to the liver parenchyma after SPIO administration, whereas HCC becomes hypointense. Furthermore, the most efficient and specific diagnostic method is scintigraphy using heat-denatured technetium-99 m-labeled red blood cells [7]. This modality, however, is not useful in diagnosis of hepatic masses or lesions and therefore should not be performed unless IHS is suspected. A key point to consider in a suspected case of IHS is the patient’s medical history because splenic injury obviously has a causal role in splenic autotransplantation, although our case is an exception.

In cases with no previous history of abdominal injury, it is obviously unusual to suspect and/or difficult to diagnose IHS. When we carefully re-examined the echo pattern of the tumor capsule in our patient, a hyperechoic rim was noted (Figure 1A). A pathological examination revealed that this hyperechoic area corresponded to a well-developed fibrous capsule with many small vascular channels. On the other hand, typical HCC is usually associated with a hypoechoic capsule, called a halo, which ordinarily has no vascular component. It is presumed that differences in echo patterns may be helpful in distinguishing IHS from HCC.

Conclusions

IHS occurs frequently in subjects with a history of splenic injury, although it is occasionally difficult to differentiate IHS from HCC by standard imaging modalities, such as contrasted CT and MRI, because of similarities in radiographic features. The most important key for diagnosis is to suspect IHS in patients with a history of splenic trauma or surgery. Our case showed that hyperechoic patterns of tumor capsule can also be used to efficiently diagnose IHS.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this study.

References:

- 1.Abu Hilal M, Harb A, Zeidan B, et al. Hepatic splenosis mimicking HCC in a patient with hepatitis C liver cirrhosis and mildly raised alpha feto protein; the important role of explorative laparoscopy. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming CR, Dickson ER, Harrison EG. Splenosis: autotransplantation of splenic tissue. Am J Med. 1976;61:414–19. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshimitsu K, Aibe H, Nobe T, et al. Intrahepatic splenosis mimicking a liver tumor. Abdom Imaging. 1993;18:156–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00198054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JB, Ryu KW, Song TJ, et al. Hepatic splenosis diagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32:180–82. doi: 10.1007/s005950200016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu H, Xia L, Li T, et al. Intrahepatic splenosis mimicking hepatoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009 doi: 10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0230. pii: bcr06.2008.0230. Erratum in: BMJ Case Rep. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwok CM, Chen YT, Lin HT, et al. Portal vein entrance of splenic erythrocytic progenitor cells and local hypoxia of liver, two events cause intrahepatic splenosis. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:1330–32. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grande M, Lapecorella M, Ianora AA, et al. Intrahepatic and widely distributed intraabdominal splenosis: multidetector CT, US and scintigraphic findings. Intern Emerg Med. 2008;3:265–67. doi: 10.1007/s11739-008-0112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fremont RD, Rice TW. Splenosis: a review. South Med J. 2007;100:589–93. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318038d1f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khosravi MR, Margulies DR, Alsabeh R, et al. Consider the diagnosis of splenosis for soft tissue masses long after any splenic injury. Am Surg. 2004;70:967–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varga I, Galfiova P, Adamkov M, et al. Congenital anomalies of the spleen from an embryological point of view. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15(12):RA269–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Costanzo GG, Picciotto FP, Marsilia GM, Ascione A. Hepatic splenosis mis-interpreted as hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients referred for liver transplantation: report of two cases. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:706–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi GH, Ju MK, Kim JY, et al. Hepatic splenosis preoperatively diagnosed as hepatocellular carcinoma in a patient with chronic hepatitis B: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23:336–41. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.2.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang KC, Cho GS, Chung GA, et al. Intrahepatic splenosis mimicking liver metastasis in a patient with gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2011;11:64–68. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2011.11.1.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leong CW, Menon T, Rao S. Post-traumatic intrahepatic splenosis mimicking a neuroendocrine tumour. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007885. pii: bcr2012007885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Vuysere S, Van Steenbergen W, Aerts R, et al. Intrahepatic splenosis: imaging features. Abdom Imaging. 2000;25:187–89. doi: 10.1007/s002619910042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]