Abstract

Objectives

Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). However, most sufferers do not have access to this treatment. One way to increase access to CBT is to administer treatment remotely via the Internet. This study piloted a novel therapist-supported, Internet-based CBT program for BDD (BDD-NET).

Design

Uncontrolled clinical trial.

Participants

Patients (N=23) were recruited through self-referral and assessed face to face at a clinic specialising in obsessive–compulsive and related disorders. Suitable patients were offered secure access to BDD-NET.

Intervention

BDD-NET is a 12-week treatment program based on current psychological models of BDD that includes psychoeducation, functional analysis, cognitive restructuring, exposure and response prevention, and relapse prevention modules. A dedicated therapist provides active guidance and feedback throughout the entire process.

Main outcome measure

The clinician-administered Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale for BDD (BDD-YBOCS). Symptom severity was assessed pretreatment, post-treatment and at the 3-month follow-up.

Results

BDD-NET was deemed highly acceptable by patients and led to significant improvements on the BDD-YBOCS (p=<0.001) with a large within-group effect size (Cohen's d=2.01, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.97). At post-treatment, 82% of the patients were classified as responders (defined as≥30% improvement on the BDD-YBOCS). These gains were maintained at the 3-month follow-up. Secondary outcome measures of depression, global functioning and quality of life also showed significant improvements with moderate to large effect sizes. On average, therapists spent 10 min per patient per week providing support.

Conclusions

The results suggest that BDD-NET has the potential to greatly increase access to CBT, at least for low-risk individuals with moderately severe BDD symptoms and reasonably good insight. A randomised controlled trial of BDD-NET is warranted.

Trial registration number

Clinicaltrials.gov registration ID NCT01850433.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, PSYCHIATRY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to explore the feasibility and acceptability of a novel therapist-guided Internet-based (ICBT) program designed to dramatically increase access to CBT for patients with BDD.

The uncontrolled nature of the study limits the possibility to make causal inferences as to what caused the observed changes.

All participants were self-referred and hence particularly motivated for treatment.

Introduction

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is characterised by an intense preoccupation with perceived defects in physical appearance that is accompanied, at some point during the occurrence of the disorder, by repetitive behaviours or mental acts, such as excessive mirror checking, in response to appearance concerns. These concerns cause clinically significant distress or functional impairment and are not better explained by an eating disorder.1 BDD is common, debilitating, associated with relatively high rates of psychiatric hospitalisation and suicidality, and has a chronic and unremitting course if left untreated.2–8 People suffering from BDD often seek non-psychiatric care due to perceived appearance flaws, such as dermatological treatment or plastic surgery.9 However, these treatments rarely work, and can even result in the deterioration of the BDD symptoms.9 10

One treatment modality that has shown promise for BDD is cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT).11 12 To the best of our knowledge, only four randomised controlled trials (RCT) have been published to date. In the mid-1990s, Rosen et al13 investigated the effect of group CBT, and Veale et al14 conducted a study of individual CBT for BDD with response rates of 81.5% and 78%, respectively. Recently, Wilhelm et al15 developed and published a multimodal treatment manual specifically designed for BDD that has been tested in one open trial and one wait-list controlled trial with large within-group effect sizes and response rates around 80–81%.16 17 In the only RCT to employ an active comparison group, Veale et al18 recently reported superiority of CBT compared to anxiety management, a credible psychological intervention primarily consisting of progressive muscle relaxation and breathing techniques, and a 52% response rate for CBT after 16 therapy sessions.

Despite the growing support for CBT and readily available treatment manuals,15 19 numerous barriers to treatment exist. One of the biggest challenges of CBT is the restricted access, partly due to a lack of trained therapists, but also due to the direct and indirect costs associated with treatment.20–22 In two online surveys, only 10–17% of people with body dysmorphic concerns reported that they had received an empirically supported psychotherapy (ie, CBT), with a majority reporting that a major contributing factor for not seeking help was shame associated with talking openly about one's appearance concerns.21 23 Furthermore, treatment barriers such as a lack of a specialised healthcare provider close by and logistic problems such as having to take time off work in order to attend therapy were also reported.21 23 Therefore, alternative ways of improving access to CBT are sorely needed.

One way to increase access to CBT is to administer treatment using the Internet.24 25 In the last decade, there has been a rapid development of Internet-based CBT (ICBT) programs, with over 100 published RCTs since 2001 for a wide range of psychiatric disorders, such as obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), major depressive disorder (MDD) and panic disorder.26–28 There are two main forms of ICBT: open access programs without any therapist guidance, and programs with therapist support that try to closely mimic the process of face-to-face CBT.29 In the latter modality of ICBT, the treatment is presented online as a series of modules accompanied by homework assignments, reflecting the content of a traditional face-to-face therapy session. During the entire treatment, an identified therapist provides guidance and gives feedback through a built-in email system. Thus, the therapeutic aim of ICBT is to cultivate new behaviours and thinking patterns, just as in traditional CBT, the only difference being the way care is delivered. There is evidence that ICBT that incorporates therapist support may result in better treatment effects when compared to ICBT provided without such guidance.30–32 Furthermore, in a recent meta-analysis of 13 RCTs directly comparing ICBT with face-to-face CBT, there was no significant difference between the two treatment modalities, suggesting the non-inferiority of ICBT.33 In some countries such as Sweden, the Netherlands and Australia, ICBT has already been implemented as part of their regular healthcare systems.34–36

With the primary aim of increasing access to evidence-based treatment for BDD, we developed BDD-NET, a structured and interactive therapist-supported ICBT program based on existing manuals,15 19 and tested its feasibility and efficacy in an uncontrolled clinical trial. We hypothesised that BDD-NET would be acceptable to patients, lead to a reduction of BDD and other psychiatric symptoms, and require minimal therapist input.

Method

Participants

The study included 23 self-referred adults with a primary DSM-5 diagnosis of BDD. Participant demographics and clinical characteristics are presented in table 1. The most common body areas of concern reported by at least 50% of the participants at baseline included: face (ie, shape or size) 18 (78%), skin 14 (61%), part of the face (eg, nose, ears, eyes) 14 (61%), hair 13 (57%) and weight 12 (52%).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample (N=23)

| Variable | Mean/n | SD/% |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean, SD) | 30.3 | (6.3) |

| Female (n, %) | 16 | (70) |

| Employment status (n, %) | ||

| Employed | 14 | (61) |

| Unemployed | 4 | (17) |

| Student | 5 | (22) |

| Married (n, %) | 7 | (30) |

| Education (n, %) | ||

| High school | 16 | (70) |

| University college | 7 | (30) |

| Previous psychological treatment (n, %) | 12 | (52) |

| Previous use of psychotropic medication (n, %) | 11 | (48) |

| Current use of psychotropic medication (n, %) | 7 | (30) |

| Years with BDD symptoms (mean, SD) | 15.3 | (8.1) |

| Number of body areas of concern (mean, SD) | 6 | (3) |

| BDD-5 insight specifier (n, %) | ||

| Good or fair insight | 10 | (43) |

| Poor insight | 11 | (48) |

| Absent/delusional beliefs | 2 | (9) |

| Current comorbidity (n, %) | ||

| Major depressive disorder | 10 | (43) |

| Panic disorder | 1 | (4) |

| Social anxiety disorder | 5 | (22) |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 2 | (9) |

| Bulimia nervosa | 2 | (9) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 1 | (4) |

BDD, body dysmorphic disorder.

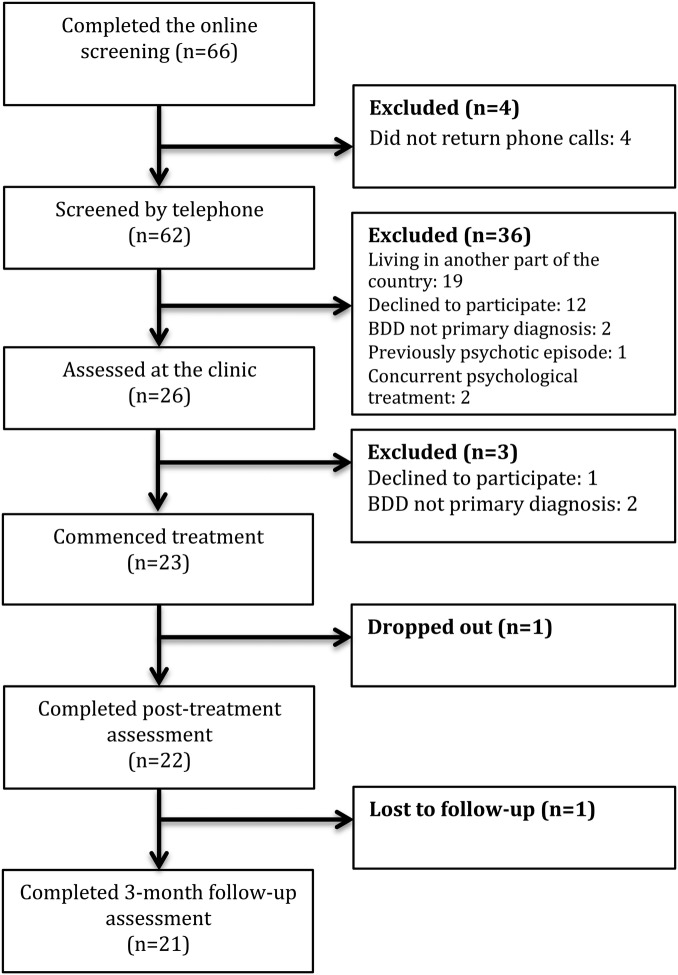

Information about the study was posted on the official web page of the clinic (http://www.internetpsykiatri.se), and flyers were distributed to mental health professionals. The study was also mentioned in a national newspaper that ran a three-part article series about BDD. A total of 66 individuals were considered for eligibility (see figure 1). To be eligible for the study, participants had to be at least 18 years of age, outpatients and diagnosed with primary DSM-5 BDD, and currently living in Stockholm or Uppsala county. As this was a pilot study exploring the feasibility of BDD-NET, geographic proximity was required to facilitate in-person assessments and an opportunity to intervene in case of safety concerns.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the study.

Exclusion criteria were psychotropic medication changes within 2 months prior to enrolment, completed CBT for BDD within the past 12 months, a score on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD-YBOCS) of ≤16, current substance dependence, a lifetime bipolar disorder or psychosis, acute suicidal ideation, a personality disorder that could jeopardise treatment participation (eg, borderline personality disorder with self-harm) or concurrent psychological treatment. Participants who were taking psychotropic medication and had been on a stable dose for at least 2 months prior to enrolment were asked not to change their medication during the study period. After a complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Clinicaltrials.gov registration ID: NCT01850433.

Procedure

In the first stage of the recruitment process, potential participants were instructed to complete an online screening consisting of the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, self-report (MADRS-S),37 Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT),38 Drug User Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT),39 Dysmorphic Concerns Questionnaire (DCQ)40 and Body Dysmorphic Disorder Dimensional Scale (BDD-D).41 All participants who completed the screening were contacted by telephone and assessed for BDD. Twenty-six individuals were invited to the clinic for an in-person assessment by either a psychiatrist or a licensed psychologist. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)42 was used to determine the presence of any DSM-IV-TR Axis-I disorders. A more in-depth interview with the BDD Diagnostic Module was conducted to establish the diagnosis of DSM-5 BDD.43 The questions used in this semistructured interview were originally designed for DSM-IV-TR criteria and are similar to those used in the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I).44 A question about the presence of repetitive behaviours was added to reflect the DSM-5 criteria for BDD and the new DSM-5 insight specifiers were also used to determine the degree of insight regarding body dysmorphic beliefs (ie, good or fair insight, poor insight and absent insight/delusional beliefs). The assessors had several years of experience administering structured interviews, such as the BDD-YBOCS, and had undergone extensive training in using the MINI. However, the inter-rater reliability of the BDD-YBOCS was not established in this study.

Measures

Participants were assessed with both clinician and self-report measures at pretreatment, post-treatment and at the 3-month follow-up. In addition, the BDD-D and MADRS-S were administered weekly to monitor progress and suicide risk. Questionnaires used in this trial have previously been translated into Swedish and also gone through a rigorous back-translation process to check for any inconsistencies.

The primary outcome of interest was BDD symptom severity as measured with the clinician-administered BDD-YBOCS. The self-report measures were administered online, a method which has previously been shown to be as reliable and valid as pen-and-paper administration.45–47

Clinician-rated instruments

Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for BDD

The BDD-YBOCS48 can be considered the gold standard for assessing symptom severity and impairment associated with BDD. It is a clinician-administered, semistructured interview consisting of 12 items; each rated on a scale from 0 to 4, which measures symptom severity during the past 7 days, in the form of intrusive thoughts (5 items), compulsions (5 items), insight (1 item) and avoidance (1 item). The total score on the BDD-YBOCS ranges from 0 to 48, with a higher score indicating more severe symptoms. The BDD-YBOCS has shown high test–retest reliability (r=0.88) and internal consistency (α=0.80).48 An empirically defined cut-off point of a 30% reduction on the BDD-YBOCS was used to determine responder status at post-treatment.49 To investigate specific treatment effects on insight, the item of the BDD-YBOCS relating to insight was also reported separately.

Clinical Global Impression

The Clinical Global Impression (CGI)50 is a clinician-rated measure of clinical global severity of illness (CGI-S) and clinical global improvement (CGI-I). The CGI-S scores range from 1 (not at all ill, normal) to 7 (extremely ill), and the CGI-I scores range from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse) and a score of 4 means unchanged. A score of 1 or 2 on the CGI-I was determined to indicate responder status in this study. CGI has shown good reliability and validity for a range of psychiatric disorders.51 52

Global Assessment of Functioning

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)53 is a clinician-rated measure consisting of a numerical scale that ranges from 0 to 100 and is used to assess social, occupational and psychological functioning, with a higher score indicating better health. Overall reliability of the GAF is good, but questions regarding its validity have been raised (see Aas54 for a review).

Self-administered measures

Body Dysmorphic Dimensional Scale

The BDD-D41 is a self-report measure of symptom severity developed alongside the DSM-5 criteria for BDD. It consists of five items measuring time occupied by thoughts and repetitive behaviours, distress, control over symptoms, avoidance and interference, each rated on a scale from 0 (none) to 4 (extreme), with a total score ranging from 0 to 20. High internal consistency has been reported (α=0.80), though further validation work is warranted.41

Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, self-report

The MADRS-S37 is a self-report version of the MADRS,55 and measures severity of depression. The scale consists of nine items, each measuring a different symptom (mood, feelings of unease, sleep, appetite, ability to concentrate, initiative, emotional involvement, pessimism and suicidal ideation) on a seven-point scale with a total score ranging from 0 to 54. Good to excellent test–retest reliability has been reported (r=0.80–0.94),37 as well as a high correlation (r=0.87) between the MADRS-S and the Beck Depression Inventory in a comparative study.56

Skin Picking Scale Revised

As skin picking is common among persons diagnosed with BDD, we used the Skin Picking Scale Revised (SPS-R)57 to assess skin picking severity and impairment. The SPS-R is a self-report measure that consists of eight items that are rated on a five-point scale from 0 (eg, none) to 4 (eg, extreme). Good internal consistency (α=0.83), as well as discriminant and convergent validity, has been reported.57

Body Image Quality of Life Inventory

The Body Image Quality of Life Inventory (BIQLI)58 is a self-report measure that consists of 19 items with a seven-point scale ranging from −3 (very negative effect) to 3 (very positive effect) that assesses the impact of the body image on various aspects of life (eg, sexuality, emotional well-being and relations). The total score ranges from −57 to 57. A positive score indicates that one's body image has a positive impact on quality of life, and vice versa. High test–retest (r=0.79) and internal consistency (α=0.94–95) have been reported.58 59

Safety procedures and adverse events

As mentioned earlier, participants with active suicidal ideation were not included in the trial. However, suicidal ideation is common among patients diagnosed with BDD and the following precautions were taken in order to detect patients who could deteriorate during treatment. All participants underwent a structured clinical interview assessing suicidal ideation before starting treatment. Throughout the entire treatment, MADRS-S was administered weekly and participants who, at any time throughout the treatment period, scored >4 on item 9, which measures suicidal ideation, were immediately contacted by their therapist. If the patient were in need of additional care, an appointment was made with either a senior psychiatrist at the clinic, or at an emergency psychiatric unit.

Adverse events (AEs) were recorded mid-treatment and at post-treatment in accordance with guidelines presented by Rozental et al.60 AE were defined as negative events that could have occurred due to treatment participation (eg, deterioration of target symptoms, worse sleep and general negative well-being such as stress). Participants were asked if they had experienced any AE that they associated with the intervention (yes/no). If yes, the participants were asked to describe the event in their own words, and rate the impact of the AE on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (no impact) to 3 (severely negative impact) at the time that the AE had occurred (retrospective self-reports), and if the AE still had a negative impact on well-being at present. A licensed psychologist reviewed the AE reported.

Treatment

The BDD-NET program was delivered via a tailored online platform, using a dedicated server with encrypted traffic and a strong authentication login function, in order to guarantee participant confidentiality. The user interface of the platform used for BDD-NET has been designed so that it can be used in any language. The 12-week long treatment was based on a CBT model for BDD, emphasising the role of avoidance and safety behaviours as maintaining factors of BDD.15 Most existing treatment protocols for BDD involve a larger number of face-to-face sessions, ranging from 12 to 22.17 18 However, considering the format of ICBT (where therapists often make several contacts during the week), as well as previous ICBT research in OCD showing that 10 weeks of treatment yields the same results as 15 weeks of treatment, a 12-week long treatment was deemed appropriate.26 61

A central part of the treatment was a self-help text of 104 pages divided into 8 modules (with modules 1–4 containing the core treatment components). The self-help text underwent several revisions, and was reviewed by licensed psychologists with previous experience of either ICBT or OCD and related disorders. Each module was devoted to a special theme and included information and homework assignments. Participants were given consecutive access to the next module after correctly answering a quiz about the material that they had read, as well as filling out at least one worksheet corresponding to the homework assignment given in the module. See table 2 for a summary of the treatment modules and the number of participants completing each module. The participant had contact with an identified therapist throughout the whole treatment using a built-in email system on the BDD-NET webpage. The two therapists providing the treatment were both licensed psychologists with several years of experience in treating OCD and related disorders. To ensure treatment integrity and adherence to protocol, a licensed psychologist monitored the messages sent by the therapists throughout the entire treatment. Participants had unlimited access to the therapist and could use the email system at any time. The role of the therapist was mainly to guide and coach the participant through the treatment, provide feedback on homework assignments, answer questions from the participants, and consecutively grant access to the next treatment module. The therapist also acted proactively by sending emails to participants asking them to report on treatment progress. The participants were notified by an automated text message (SMS) when they had a new email in the treatment platform. All homework assignments and questions from the participants were reviewed and answered within 36 h, except on weekends. Participants were randomised using random.org to one of two therapists, both licensed psychologists, with previous experience of treating OCD and related disorders. The duration of therapist contact was automatically recorded by the ICBT platform. None of the participants had face-to-face contact with a therapist.

Table 2.

Description of consecutive treatment modules and the number of participants completing each module

| Module | Contents | Number of participants* |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Psychoeducation: Introduction to the treatment and information about BDD such as prevalence, known aetiology and common symptoms. Different fictional patient characters are introduced and used as examples to help clarify the treatment components throughout the treatment. Participants begin to register BDD-related behaviours and thoughts in an online diary | 22 (96%) |

| 2 | A cognitive–behavioural conceptualisation: Explanation of how self-defeating thoughts and BDD-related avoidance and safety behaviours maintain appearance concerns and fears. Participants learn how to conduct a functional analysis of how their own BDD symptoms are maintained | 21 (91%) |

| 3 | Cognitive restructuring: A more in-depth rationale for how self-defeating thoughts and maladaptive thinking maintain BDD symptoms. Participants evaluate negative thoughts and engage in cognitive restructuring using online worksheets | 21 (91%) |

| 4 | ERP: Explanation of exposure and different strategies for conducting response prevention is presented. Participants set treatment goals and conduct their first in vivo ERP exercise. ERP continues during the remainder of treatment, and participants continuously assess the outcome of ERP using an online worksheet | 19 (83%) |

| 5 | More on ERP: Different aspects of ERP are highlighted and a more in-depth explanation is given on how to work with ERP over time | 14 (61%) |

| 6 | Values-based behaviour change: Participants identify values-based long-term goals within the domains of relationships, career and leisure activities. An accepting stance towards negative thoughts and experiences is proposed as an alternative to attempts to control these experiences, while at the same time engaging in meaningful values-based activities | 13 (57%) |

| 7 | Difficulties during treatment: Commonly encountered difficulties during treatment such as loss of motivation and problems in integrating exercises into the daily schedule are presented and discussed, as well as common obstacles associated with ERP and how to overcome them | 10 (44%) |

| 8 | Relapse prevention: How to handle relapses into avoidance behaviours and repetitive behaviour. The participants also summarise the main lessons learnt, what has been gained through the treatment and their future plans | 6 (27%) |

*Defined as doing the homework associated with each module.

BDD, body dysmorphic disorder; ERP, exposure and response prevention.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were done according to intention-to-treat (ITT) including the full sample of 23 participants. Missing data at post-treatment and follow-up assessment were deemed to be missing at random (using logistic regression models, as well as inspecting correlations between indicator variables of missingness and other variables from the data set that might predict missingness) and imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations.62 All estimates with SEs were pooled from five imputations using ‘Rubin's rules’63 and the small sample correction for pooled degrees of freedom.64 Paired t tests were performed to assess if changes from pretreatment to post-treatment and pretreatment to follow-up were statistically significant. Paired t tests comparing post-treatment to follow-up were also performed to test for maintenance of the therapeutic gains. Within-group effect sizes were calculated by dividing the difference between pretreatment and post-treatment scores by the within-group pooled SD.65 Fisher's exact test was used to examine whether there was an association between the occurrence of an AE and treatment responder status, and independent t tests were used to examine specific therapist effects. All data were analysed with Stata statistical software, V.13.166 and the threshold for statistical significance was set at the standard 5%.

Results

Attrition

The participant flow throughout the trial is shown in figure 1. One participant terminated treatment during the first week due to reported personal problems and did not complete any of the modules and was therefore regarded as a dropout, but was kept in the primary analysis according to the ITT principles. The post-treatment and 3-month follow-up assessments were completed by 22 (96%) and 21 (91%) participants, respectively. Self-rated questionnaires administered online were completed by 20 (87%) participants at post-treatment, and by 19 (83%) participants at the 3-month follow-up.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Means, SDs and within-group effect sizes, including CIs, for all assessment points with missing values replaced by multiple imputation are reported in table 3. Paired t tests showed significant changes on all measures from pretreatment to post-treatment (t(df=13.72–20.15)=3.10–7.54, all p values <0.01), and from pretreatment to follow-up (t(df=10.96–19.24)=3.13–8.66, all p values <0.01). On the main outcome measure (BDD-YBOCS), the pretreatment to post-treatment effect size was d=2.01, and the pretreatment to follow-up effect size indicated sustained effects (d=2.04).

Table 3.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

| Measure | |

|

|

Within-group effect size d |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment |

Post-treatment |

3-Month follow-up* |

Pretreatment to post* |

Pretreatment to follow-up* |

Post-treatment to follow-up* |

||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | d | CI− | CI+ | d | CI− | CI+ | d | CI− | CI+ | |

| BDD-YBOCS | 30.78 | 6.24 | 15.70 | 8.48 | 13.85 | 9.57 | 2.01 | 1.05 | 2.97 | 2.04 | 1.18 | 2.91 | 0.20 | −0.14 | 0.54 |

| BDD-YBOCS i | 2.17 | 0.89 | 1.42 | 0.83 | 1.22 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.34 | 1.42 | 1.07 | 0.39 | 1.74 | 0.23 | −0.24 | 0.70 |

| BDD-D | 13.09 | 3 | 7.67 | 4.03 | 6.38 | 4.19 | 1.51 | 0.62 | 2.41 | 1.82 | 0.96 | 2.68 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.61 |

| MADRS-S | 17.91 | 8.22 | 10.23 | 7.52 | 11.74 | 10.17 | 0.97 | 0.47 | 1.48 | 0.65 | 0.18 | 1.11 | −0.15 | −0.42 | 0.11 |

| SPS-R | 8.83 | 7.31 | 4.91 | 6.78 | 4.53 | 6.31 | 0.55 | 0.15 | 0.96 | 0.63 | 0.18 | 1.07 | 0.06 | −0.14 | 0.25 |

| BIQLI† | −27.26 | 13.38 | −10.83 | 17.36 | −11.11 | 19.66 | 1.05 | 0.35 | 1.75 | 0.96 | 0.17 | 1.75 | −0.02 | −0.32 | 0.29 |

| GAF | 49.87 | 7.23 | 61.75 | 8.85 | 63.21 | 9.05 | 1.47 | 0.69 | 2.25 | 1.62 | 0.90 | 2.33 | 0.16 | −0.09 | 0.42 |

Effect sizes are reported with 95% CIs.

*Pooled estimates based on multiple imputation.

†Higher scores indicate better health. Sign of effect sizes changed for clarity.

BDD-D, Body Dysmorphic Disorder Dimensional Scale; BDD-YBOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for BDD; BDD-YBOCS i, BDD-YBOCS insight item; BIQLI, Body Image Quality of Life Inventory; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning Scale; MADRS-S, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, self-report; SPS-R, Skin Picking Scale Revised.

At post-treatment, 82% of completers were responders (≥30% decrease on the BDD-YBOCS), and the mean decrease of the BDD-YBOCS score from pretreatment to post-treatment was 51% (mean difference=15.08, 95% CI 10.86 to 19.30).

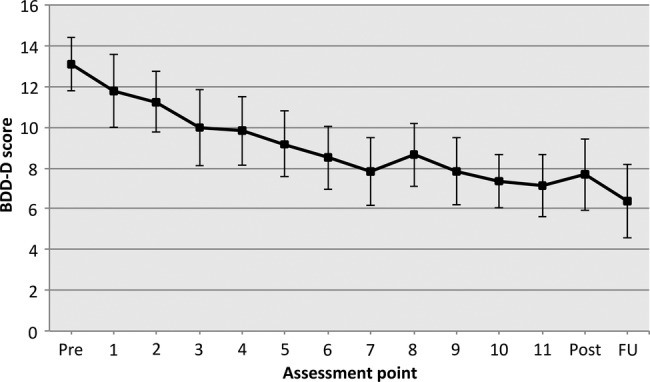

The significant pretreatment to post-treatment improvement on the BDD-YBOCS insight item was in the large range (t(18.44)=4.30, p=<0.001, d=1.07). Weekly scores and follow-up data on the self-reported BDD-D are presented in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Weekly scores on the self-administered Body Dysmorphic Disorder Dimensional Scale, BDD-D (including 95% CIs).

The distribution of CGI-I scores for completers at post-treatment and follow-up, respectively, was as follows: very much improved, 41% and 52%; much improved, 23% and 19%; minimally improved, 27% and 19%; no change, 5% and 10%. At post-treatment and follow-up, 64% and 71% were responders (very much or much improved), respectively.

On the other outcome measures, the within-group effect sizes from pretreatment to post-treatment and from pretreatment to follow-up were in the moderate to large range (d=0.55–1.82).

Adverse events

In total, 11 (48%) participants reported that they had experienced AE during the course of treatment. The most frequent side effect was the emergence of new symptoms (43%, eg, nightmares, depressive symptoms and worse sleep), followed by a deterioration of symptoms (29%, eg, more frequent negative thoughts about appearance and/or focus on appearance) and general negative well-being (29%, eg, stress). The AE reported occurred mostly during the first part of the treatment, and most participants rated the negative impact of the AE as moderate (median=2, M=1.8, SD=1.1) when they occurred, and as no longer having a negative impact at post-treatment (median=0, M=0.7, SD=1.6) with the exception of one participant who reported that the treatment had led to an increase in appearance concerns and more frequent intrusive thoughts compared to baseline, and was classified as a non-responder at post-treatment. The occurrence of AE during treatment was unrelated to responder status at post-treatment, with 8 (44%) of the responders reporting an AE compared to 3 (75%) of the non-responders (Fisher's exact test=0.59).

During treatment, one participant became increasingly depressed and was referred for a detailed psychiatric evaluation and was prescribed an selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (week 9), after which treatment continued.

Treatment activity and acceptability

The mean number of messages that the participants sent to and received from their therapist was 22.6 (SD=12.2, range 0–47) and 30.2 (SD=11.3, range 3–51), respectively, and the therapists spent a weekly mean of 10.3 min (SD=6.7, range 1.8–35.2) per participant. No significant differences were noted in time spent providing support (t(21)=1.19, p=0.25, d=0.5 95% CI −0.39 to 1.39), or in treatment effects between the two therapists (t(21)=−0.60, p=0.56, d=−0.26 95% CI −1.11 to 0.60).

In total, 19 (83%) participants completed the core components of the treatment programme (modules 1–4), and six participants completed all eight of the modules (26%). The mean number of completed modules was 5.5 (SD=2.35, range 0–8). Most participants spent 2–7 h/per week (retrospective self-reports) on the treatment, for example, doing exercises in vivo and reading material online.

At post-treatment, 6 (30%) participants reported that they were very pleased with the treatment provided; 11 (55%) that they were pleased; 1 (5%) was somewhat pleased; 1 (5%) was neither pleased nor displeased; and 1 (5%) was somewhat displeased with the treatment provided. One participant did not answer the satisfaction question.

All participants on psychotropic medication prior to treatment had kept their dose stable during treatment, and none had received any other type of psychological intervention. In total, 5 (22%) participants reported that they had received additional care at the 3-month follow-up. Of the participants receiving additional care, four were non-responders according to the CGI-I at post-treatment, and all endorsed a score above 20 on the BDD-YBOCS at follow-up. The other participant was classified as a responder at post-treatment and follow-up, endorsing a score of 4 on the BDD-YBOCS. Two participants had received one and five sessions of face-to-face CBT, respectively, two participants had been prescribed a serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI, of which one was prescribed for an indication other than BDD), and one participant had increased the dose of current SRI.

Discussion

This study explored the feasibility and acceptability of a novel therapist-guided ICBT program designed to increase access to CBT for patients with BDD. In general, the participants felt that BDD-NET was highly acceptable. A significant improvement was seen on the main outcome measure (clinician-rated BDD-YBOCS), with a large effect size, and 82% of the participants classed as responders at post-treatment. These treatment effects were maintained at the 3-month follow-up. The clinician-rated insight also improved from pretreatment to post-treatment. Secondary outcome measures of depression, skin picking, global functioning and body image-related quality of life showed significant improvements from pretreatment to post-treatment, and from pretreatment to follow-up, with moderate to large effect sizes.

In general, the results are in line with other trials investigating the effects of individual CBT for BDD delivered in specialised clinic settings.16–18 However, direct comparisons with previous trials should be made with caution, because ours was a self-referred and moderately ill patient group with relatively good insight. Some research has shown that the source of patient referral may have a bearing on the types of patients seen and on the degree of clinical improvement with computerised or internet-based therapies, with patients referred by mental health professionals having more comorbidity, being less motivated for treatment and achieving more modest outcomes, compared to self-referrals or referrals from general practitioners.67

A comparison of the demographic and clinical characteristics of our sample with those of two recently published RCTs appears in table 4. A cut-off of 16 on the BDD-YBOCS was used for entry into the study, which would represent minimal symptoms. However, only one participant had a score on the BDD-YBOCS below 22; the range of baseline BDD-YBOCS scores was 16–42, and the score median was 30. Thus, our sample had moderate to severe symptoms. Despite having moderate to severe BDD symptoms, our predominantly female, self-referred sample might have been particularly motivated to engage in psychological treatment, compared to the patient with average BDD seen in specialist settings. The proportion of patients with absent or delusional insight also appears to be lower in this sample compared to the proportions seen in specialist clinic samples. Furthermore, although the rates of comorbid disorders were similar, on average, our participants endorsed mild depressive symptoms, compared to the moderate to severe depressive symptoms reported in the trials published by Wilhelm et al17 and Veale et al.18

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the current study, compared to two recent RCTs of CBT for BDD

| Variable | BDD-NET | Veale et al18 | Wilhelm17* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 30.3 (6.3) | Median=30 | 33.2 (11.4) |

| Female (%) | 70 | 57 | 53 |

| Employed (%) | 61 | 46 | 65 |

| Referral | Self-referred | Primary or secondary care | Self-referred |

| BDD-YBOCS | 30.78 (6.24) | 35.48 (6.61)* | 32.5 (3.2) |

| Delusional BDD (%) | 9 | 54 | NA |

| BABS | NA | 18.24 (4.68)* | 14.1 (3.9) |

| MADRS | 17.91 (8.22) | 28.57 (10.69)* | n/a |

| BDI | NA | NA | 22.4 (14) |

| Current comorbidity (%) | |||

| MDD | 43 | 44 | 47 |

| SAD | 22 | 11 | 24 |

| OCD | 9 | 4 | 6 |

| Current use of medications (%) | 30 | 46 | 71 |

Values denote means±SD unless otherwise specified.

*Participant characteristics of those randomised to CBT.

BABS, Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale; BDD, body dysmorphic disorder; BDD-NET, Internet-based CBT program for BDD; BDD-YBOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for BDD; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; NA, not applicable; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SAD, social anxiety disorder.

ICBT should not be seen as a substitute for traditional face-to-face treatment, but rather a clinician extender that may substantially increase access to evidence-based treatment for a large proportion of sufferers who are not currently receiving it. Clearly, ICBT will not be indicated for all BDD patients, and specialist input will be required for complex patients who have poor insight and high suicide risk. In this regard, BDD-NET may be particularly useful in the context of stepped care for BDD, where low-risk patients with reasonably good insight are offered ICBT and non-responders or more complex and risky patients are offered more intensive, clinic-based CBT alone or in combination with medication.

Participants in this trial made marked improvements despite no face-to-face contact, beyond the baseline, post-treatment and follow-up assessments. Although the treatment is Internet-based, the mechanisms of change may be the same as in traditional CBT (ie, behaviour change/habituation through exposure and response prevention (ERP)) as the participant is still instructed to expose himself or herself to feared stimuli in vivo without using maladaptive coping strategies. Each participant had the same identified therapist throughout the entire treatment, and although therapist contact was only around 10 min per participant per week, the therapist sent a mean number of 30.2 messages per participant, which averages out to 2–3 contacts per week. Messages sent from the therapist were usually short, with prompts to the participant to engage in ERP and report the outcome, allowing for adjustment of exposure strategies when needed. Thus, the therapist was proactive and had shorter, but more frequent, contact with participants compared to traditional CBT, where sessions usually are held once a week. Despite minimal therapist contact, participants often report the feeling of a therapist presence; the therapists’ frequent encouragement to engage in daily ERP may be a critical component of the intervention.32

In total, 48% of the participants experienced an AE during treatment. However, the AEs were mostly mild, and non-enduring, and a vast majority of participants were very pleased or pleased with the treatment provided. Most (83%) of the participants completed all of the core treatment components and engaged in ERP, suggesting that the treatment was engaging and highly acceptable. The treatment completion rate is in line with previous ICBT studies of various disorders, suggesting that ICBT is as acceptable for patients with BDD as it is for other patient groups (eg, OCD, SAD and MDD).26 27

Stigma, shame and logistic barriers can be a hindrance for persons with BDD to seek treatment.21 23 An advantage of BDD-NET is that all therapist contact is online; this could reduce the initial shame and stigma associated with openly talking about one's appearance concerns. BDD-NET also eliminates the need for weekly visits to the clinic while receiving CBT and has the potential to minimise logistic barriers and increase access to evidence-based care in rural areas or where trained therapists are not available. Furthermore, one therapist can have more patients in treatment at the same time compared to face-to-face therapy, while spending less time per patient as the routine aspects of treatment are delegated to the computerised platform. Thus, the ICBT format has the potential to lower the severity threshold for people with BDD to seek and receive adequate treatment. Expert clinicians can dedicate more time and resources to complex, for example, suicidal, cases. Another advantage of BDD-NET is that the treatment is protocol based and delivered as a series of modules online. This greatly reduces the risk of therapist drift,68 and ensures that all patients receive exactly the same treatment. The control over content delivered also opens up for dismantling studies, as modules can easily be added or taken out to test the specific effect of a treatment component, as shown by Ljótsson et al69 where the specific effect of systematic exposure on Irritable Bowel Syndrome symptoms was tested.

This study has several limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. First and foremost, this was an uncontrolled trial. This limits the possibilities to make causal inferences as to what caused the observed changes. The improvements observed over the course of treatment could have been due to the mere passage of time. However, when considering the chronicity of BDD,8 70 we regard it as unlikely that the treatment effects in this trial could be entirely explained by spontaneous remission. Furthermore, the improvements observed could also be due to unspecific factors, such as caregiver attention. However, the maintenance of improvement from post-treatment to follow-up indicates that the treatment gains were temporally stable, and that the majority of participants did not receive any further treatment. Owing to safety concerns, the presence of severe suicidal ideation and substance dependence, both of which are common comorbidities in BDD, was a criterion for exclusion. Thus, it is unknown if BDD-NET would be appropriate for patients with these comorbidities. The insight item on the BDD-YBOCS was used to assess change in insight before and after treatment; other available instruments, such as the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS),71 may have provided a more precise and sensitive measure of overvalued ideation. Both therapists in the study had previous experience of treating BDD, and although the essential components of the treatment are delivered as online modules, there could be a specific therapist factor as the therapists answered questions and gave treatment guidance through the integrated email system. It is unknown if the same outcomes would be obtained with less experienced therapists.

Despite the limitations of this uncontrolled trial, the results suggest that BDD-NET has the potential to reduce symptoms and increase access to CBT for a large majority of moderately ill patients with BDD who are motivated to receive treatment. A randomised controlled trial of BDD-NET is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Monica Hellberg, Sofia Eriksson, Vania Panes Lundmark and Kayoko Isomura for their invaluable help.

Footnotes

Contributors: JE was the project manager and participated in designing the study, analysing the data, providing treatment, and drafting the manuscript and the treatment manual. VZI participated in designing the study, providing treatment and drafting the manuscript and the treatment manual. EA participated in designing the study and drafting the manuscript and the treatment manual. DM-C participated in drafting the manuscript and designing the study. BL participated in designing the study, analysing the data and drafting the manuscript and the treatment manual. CR participated in designing the study and drafting the treatment manual and the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: Financial support was provided through the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between the Stockholm County Council and the Karolinska Institutet (grant number: 20130538). The Swedish Research Council (grant number: K2013-61X-22168-01-3) and the Swedish Society of Medicine (Söderströmska Königska sjukhemmet, grant number: SLS-384451) provided funding for this study.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The regional ethical review board in Stockholm, Sweden approved the study ID: 2013/117-31/2.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edn Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rief W, Buhlmann U, Wilhelm S, et al. . The prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder: a population-based survey. Psychol Med 2006;36:877–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buhlmann U, Glaesmer H, Mewes R, et al. . Updates on the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder: a population-based survey. Psychiatry Res 2010;178:171–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koran LM, Abujaoude E, Large MD, et al. . The prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in the United States adult population. CNS Spectr 2008;13:316–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips KA, Diaz SF. Gender differences in body dysmorphic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997;185:570–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips KA, Coles ME, Menard W, et al. . Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in body dysmorphic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:717–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips KA, Menard W, Fay C, et al. . Psychosocial functioning and quality of life in body dysmorphic disorder. Compr Psychiatry 2005;46:254–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips KA, Menard W, Quinn E, et al. . A 4-year prospective observational follow-up study of course and predictors of course in body dysmorphic disorder. Psychol Med 2013;43:1109–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarwer DB, Crerand CE. Body dysmorphic disorder and appearance enhancing medical treatments. Body Image 2008;5:50–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crerand CE, Phillips KA, Menard W, et al. . Nonpsychiatric medical treatment of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics 2005;46:549–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ipser JC, Sander C, Stein DJ. Pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for body dysmorphic disorder. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2009;1:CD005332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams J, Hadjistavropoulos T, Sharpe D. A meta-analysis of psychological and pharmacological treatments for body dysmorphic disorder. Behav Res Ther 2006;44:99–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen JC, Reiter J, Orosan P. Cognitive-behavioral body image therapy for body dysmorphic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995;63:263–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veale D, Gournay K, Dryden W, et al. . Body dysmorphic disorder: a cognitive behavioural model and pilot randomised controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 1996;34:717–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Steketee G. A cognitive-behavioral treatment manual for body dysmorphic disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Fama JM, et al. . Modular cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder. Behav Ther 2011;42:624–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Didie E, et al. . Modular cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Ther 2014;45:314–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veale D, Anson M, Miles S, et al. . Efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapy versus anxiety management for body dysmorphic disorder: a randomised controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom In press, 2014. doi:10.1159/000360740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veale D, Neziroglu F. Body dysmorphic disorder: a treatment manual. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro DA, Cavanagh K, Lomas H. Geographic inequity in the availability of cognitive behavioural therapy in England and Wales. Behav Cogn Psychother 2003;31:185–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marques L, Weingarden HM, Leblanc NJ, et al. . Treatment utilization and barriers to treatment engagement among people with body dysmorphic symptoms. J Psychosom Res 2011;70:286–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mojtabai R Trends in contacts with mental health professionals and cost barriers to mental health care among adults with significant psychological distress in the United States: 1997–2002. Am J Public Health 2005;95:2009–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buhlmann U Treatment barriers for individuals with body dysmorphic disorder: an internet survey. J Nerv Ment Dis 2011;199:268–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G. Internet-administered cognitive behavior therapy for health problems: a systematic review. J Behav Med 2008;31:169–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedman E Therapist guided internet delivered cognitive behavioural therapy. BMJ 2014;348:g1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersson E, Enander J, Andren P, et al. . Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med 2012;42:2193–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedman E, Ljotsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2012;12:745–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wootton BM, Dear BF, Johnston L, et al. . Remote treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 2013;2:375–84 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersson G Using the Internet to provide cognitive behaviour therapy. Behav Res Ther 2009;47:175–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayo-Wilson E, Montgomery P. Media-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy and behavioural therapy (self-help) for anxiety disorders in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;9:CD005330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berger T, Hammerli K, Gubser N, et al. . Internet-based treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing guided with unguided self-help. Cogn Behav Ther 2011;40:251–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kenwright M, Marks I, Graham C, et al. . Brief scheduled phone support from a clinician to enhance computer-aided self-help for obsessive-compulsive disorder: randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychol 2005;61:1499–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, et al. . Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behaviour therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry In press, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hedman E, Ljotsson B, Kaldo V, et al. . Effectiveness of Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for depression in routine psychiatric care. J Affect Disord 2014;155:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruwaard J, Lange A, Schrieken B, et al. . The effectiveness of online cognitive behavioral treatment in routine clinical practice. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e40089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams AD, Andrews G. The effectiveness of Internet cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) for depression in primary care: a quality assurance study. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e57447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Svanborg P, Åsberg M. A new self-rating scale for depression and anxiety states based on the comprehensive psychopathological rating scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994;89:21–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. . Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. Addiction 1993;88:791–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berman AH, Bergman H, Palmstierna T, et al. . Evaluation of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. Eur Addict Res 2005;11:22–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oosthuizen P, Lambert T, Castle DJ. Dysmorphic concern: prevalence and associations with clinical variables. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1998;32:129–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LeBeau RT, Mischel ER, Simpson HB, et al. . Preliminary assessment of obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorder scales for DSM-5. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 2013;2:114–18 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. . The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phillips KA The broken mirror: understanding and treating body dysmorphic disorder. Revised and expanded edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 44.First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. . Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders (SCID-I) (Swedish Version). Danderyd: Pilgrim Press, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coles ME, Cook LM, Blake TR. Assessing obsessive compulsive symptoms and cognitions on the internet: evidence for the comparability of paper and Internet administration. Behav Res Ther 2007;45:2232–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carlbring P, Brunt S, Bohman S, et al. . Internet vs. paper and pencil administration of questionnaires commonly used in panic/agoraphobia research. Comput Human Behav 2007;23:1421–34 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Enander J, Andersson E, Kaldo V, et al. . Internet administration of the dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale: a psychometric evaluation. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 2012;1:325–30 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Phillips KA, Hollander E, Rasmussen SA, et al. . A severity rating scale for body dysmorphic disorder: development, reliability, and validity of a modified version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Psychopharmacol Bull 1997;33:17–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips KA, Hart AS, Menard W. Psychometric evaluation of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale Modified for Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD-YBOCS). J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 2014;3:205–8 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guy W, ed. Clinical global impressions. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human services, 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zaider TI, Heimberg RG, Fresco DM, et al. . Evaluation of the clinical global impression scale among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Psychol Med 2003;33:611–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kadouri A, Corruble E, Falissard B. The improved Clinical Global Impression Scale (iCGI): development and validation in depression. BMC Psychiatry 2007;7:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4th edn Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aas IH Global assessment of functioning (GAF): properties and frontier of current knowledge. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2010;9:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979;134:382–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Svanborg P, Asberg M. A comparison between the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the self-rating version of the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). J Affect Disord 2001;64:203–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Snorrason I, Ólafsson RP, Flessner CA, et al. . The skin picking scale-revised: factor structure and psychometric properties. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 2012;1:133–7 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cash TF, Fleming EC. The impact of body-image experiences: development of the body image quality of life inventory. Int J Eat Disord 2002;31:455–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cash TF, Jakatdar TA, Williams EF. The body image quality of life inventory: further validation with college men and women. Body Image 2004;1:279–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rozental A, Andersson G, Boettcher J, et al. . Consensus statement on defining and measuring negative effects of Internet interventions. Internet Interv 2014;1:12–19 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andersson E, Ljotsson B, Hedman E, et al. . Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder: a pilot study. BMC Psychiatry 2011;11:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Royston P Multiple imputation of missing values: further update of ice, with an emphasis on interval censoring. Stata J 2007;7:445–64 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-care databases: an overview and some applications. Stat Med 1991;10:585–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barnard RJ, Rubin DB. Miscellanea. Small-sample degrees of freedom with multiple imputation. Biometrika 1999;86:948–55 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. . Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, UK: Wiley, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stata Statistical Software: Release 13 [program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2013

- 67.Mataix-Cols D, Cameron R, Gega L, et al. . Effect of referral source on outcome with cognitive-behavior therapy self-help. Compr Psychiatry 2006;47:241–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Waller G Evidence-based treatment and therapist drift. Behav Res Ther 2009;47:119–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ljótsson B, Hesser H, Andersson E, et al. . Provoking symptoms to relieve symptoms: a randomized controlled dismantling study of exposure therapy in irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Res Ther 2014;55:27–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Phillips KA, Pagano ME, Menard W, et al. . A 12-month follow-up study of the course of body dysmorphic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:907–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eisen JL, Phillips KA, Baer L, et al. . The brown assessment of beliefs scale: reliability and validity. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:102–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.