Abstract

It is generally accepted that silica (SiO2) is not toxic. But the increasing use of silica nanoparticles (SiO2NPs) in many different industrial fields has prompted the careful investigation of their toxicity in biological systems. In this report, we describe the effects elicited by SiO2NPs on animal and cell physiology. Stable and monodisperse amorphous silica nanoparticles, 25 nM in diameter, were administered to living Hydra vulgaris (Cnidaria). The dose-related effects were defined by morphological and behavioral assays. The results revealed an all-or-nothing lethal toxicity with a rather high threshold (35 nM NPs) and a LT50 of 38 h. At sub lethal doses, the morphophysiological effects included: animal morphology alterations, paralysis of the gastric region, disorganization and depletion of tentacle specialized cells, increase of apoptotic and collapsed cells, and reduction of the epithelial cell proliferation rate. Transcriptome analysis (RNAseq) revealed 45 differentially expressed genes, mostly involved in stress response and cuticle renovation. Our results show that Hydra reacts to SiO2NPs, is able to rebalance the animal homeostasis up to a relatively high doses of SiO2NPs, and that the physiological modifications are transduced to gene expression modulation.

Keywords: amorphous silica nanoparticles, Hydra, extracellular matrix homeostasis, GSH response, RNAseq, nanotoxicity

Introduction

Silicon is an abundant element in the earth’s crust and biota. Starting from the prehistoric flints, humans have used materials containing natural silicon and its compound to build artifacts. Today, silica-based components are present in every digital devices that enhance the modern human activities. In the near future, nano-biotechnological approaches will deliver many nanoscale smart sensors and drugs to solve biomedical issues and there is a great expectation on silica-based nanostructures. Amorphous silica can be of natural origin (Diatoms) or synthetic (silica-gel, colloidal). Aggregates of amorphous silica of micrometer size have been used for years in oral and dermatological formulations, medicines, food, and cosmetics; hence, new nanomaterials containing SiO2 are considered low toxic and moderately biocompatible. However, the fast growing knowledge in the nanoscience fields has confirmed that, at nano-dimension, materials can acquire new features (Napierska et al., 2010). This is true also for the amorphous silica: in fact, if nanoparticle aggregates ranging from a few micrometers up to millimeter are rather irritant but non-toxic, on the other hand, SiO2 nanoparticles (SiO2NPs) show a dose-related toxicity in in vitro experiments (Napierska et al., 2010). In water, SiO2 surface exhibits silanol groups (Si–O–H). At nanoscale, the high density of silanol groups on SiO2NPs form several siloxane framework architectures making SiO2NPs extremely reactive and prone to be modified by environmental factors. These architectures are combinations of closed siloxane rings, along with the spatial arrangement, pattern, and degree of hydrogen bonding that terminate the siloxane rings at the silica NP surface; in addition, some scientists have also hypothesized surface-associated radicals inducing ROS species (Gazzano et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012).

In recent years, many new synthetic routes to produce amorphous silica stabilized nanoparticles have been developed and a few publications describe that even the synthetic procedure can influence their effects on cells (Zhang et al., 2012) and living systems, therefore, the assessment of the structure–activity relationships for amorphous silica is problematic. While crystalline silica is structurally well-defined, amorphous silica lack long-range order, and, due to a flat energy landscape, their structures are strongly dependent on synthetic procedures. Therefore, it is necessary to associate to each synthetic procedure an exhaustive description of the effects produced in living organisms: (i) to explain the mechanism of action of new materials, (ii) to open new ways on novel material application potentialities, (iii) to create a database of material/living-systems interactions.

The aim of this study is to investigate the possible toxicity of SiO2NPs at animal level. Malvindi et al. (2012) synthesized, through the microemulsion methodology, stable and monodisperse silica nanoparticles, and accurately characterized their physico/chemical properties. Through an in vitro approach, they described (within the picomolar–nanomolar range) the cellular uptake and the absence of toxic effects. Here, we describe the effects of SiO2NPs, synthesized following the same procedure, on a small model organism, the coelenterate Hydra vulgaris.

Hydra is a freshwater invertebrate; organized in two epithelia (ectoderm, endoderm) whose cells originate from three cell lineages that differentiate in more than 15 types of specialized cells (armed, secretory, digestive, nervous, myoepithelial) (Hobmayer et al., 1990). Cell type composition follows defined proportions and can be analyzed by macerating the animals in fixed cell suspensions (David, 1973). Hydra anatomy can be summarized as a hollow tube with a tentacles crown. As for many other animals, Hydra is covered by a cuticle, an extracellular matrix secreted by ectodermal cells that forms the distal interface with the environment. It has been shown that Hydra cuticle proteins from the PPOD and SWT families are associated with chondroitin and chondroitin 6-sulfate (Bottger et al., 2012). The behavior of Hydra is well characterized; the gastric region expands and contracts spontaneously with a defined pace (Ruggieri et al., 2004). Hydra undertakes active feeding, and this behavior that can be mimicked by Glutathione (GSH) (Lenhoff, 1961; Westfall and Kinnamon, 1984). These two peculiar aspects of Hydra biology are considered in this work in the context of interaction with new nanomaterials; traditionally used in developmental, regenerative, and evolutionary research contexts (Galliot et al., 2009; Bode, 2011) Hydra is actually a good biological indicator for environmental studies (Karntanut and Pascoe, 2002). In addition, stress response genes are conserved and at least in part characterized (Martinez and Bridge, 2012). In previous works, we have successfully exploited the potential of Hydra to describe the mechanisms of action underlying the interaction of nanoparticles with living organisms and the animal toxicity of new materials establishing reliable methods to evaluate at multiple levels their toxic effect (Tortiglione et al., 2007, 2009; Malvindi et al., 2008; Ambrosone et al., 2012; Ambrosone and Tortiglione, 2013; Marchesano et al., 2013).

Here, we determined a wide array of toxicity endpoints caused by SiO2NPs, spanning from behavior, morphology, population growth rate, cell proliferation/apoptosis balance up to gene expression profiling. Hydra transcriptomic changes further suggested that even in absence of severe alterations, treatment with SiO2NPs causes effects that can be transduced to the nucleus and influence gene expression to ultimately modify principal cell functions such as cuticle renovation and response to stress.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of SiO2NPs in a ternary w/o microemulsion (25 nm)

SiO2NPs were prepared by following recently optimized synthesis procedure (Malvindi et al., 2012). The ternary microemulsion synthesis permits to obtain 25 nM SiO2NPs highly monodispersed and stable. The ultrasonic treatment was used to completely disperse the SiO2NPs before the treatments. The surface of the nanoparticles was modified with amine groups using 5% (v/v) solution of aminopropyltrietoxysilane (APTES, Sigma Aldrich) and 1 mM acetic acid (99.7%, Sigma Aldrich) and stirring for 60 min. Fluorescent SiO2NPs were prepared adding to the microemulsion 50 μL of Rhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC) dye, previously modified as above described, so TRITC was covalently linked inside SiO2NPs (Guarnieri et al., 2014).

Culture of test organisms

Hydra vulgaris were cultured in Hydra medium consisting of 1 mM calcium chloride, 0.1 mM sodium hydrogen carbonate, pH 7 (Loomis and Lenhoff, 1956). Animals were fed on alternate days with Artemia nauplii at 18°C with a 12:12 hours light:dark regime. Polyps from homogeneous populations, 3-weeks-old and carrying one or two buds, were selected for the experiments.

Morphological and behavioral assays

Toxicity tests

Toxicity tests were carried out on groups of 25 polyps for 24, 44, 48, 50, 72 h at SiO2NP concentrations of 10, 15, 25, 35, 50 nM. Either control or treated animals were placed into plastic multiwells refreshing the medium every 24 h. The morphophysiological effects were recorded by microscopic examination of each polyp and used to extrapolate the score key reported in Table 1, ranging from 7 for a normal polyp to 1 for polyps irreversibly damaged to death. The median scores were analyzed at 24, 44, and 50 h for each concentration of SiO2NPs. On the base of these outcomes, lethal dose and lethal time were calculated by applying the trimmed Spearman–Karber method (Hamilton et al., 1977).

Table 1.

Description of morphological traits and vital states of SiO2NPs treated Hydra and corresponding score key.

| Score | Morphology | Vital state |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | Normal hydra | Active |

| 6 | Bumped gastric region, normal tentacles | Active |

| 5 | Inverted-cone gastric region; shortened tentacles | Whitening, gastric region paralyzed, slow tentacles |

| 4 | Inverted-cone gastric region, short tentacles | Paralyzed, rigid tentacles |

| 3 | Gastric region reduced in size, crushed tentacles | Permanently damaged to death |

| 2 | Further reduced gastric region, without tentacles | Abundant cell loss |

| 1 | Irregular shape | Death |

| 0 | Dispersed cell clumps and debris | Disintegrated |

Tentacle structure and battery cell complex organization

Tentacle structure and battery cell complex organization were evaluated by toluidine-blue staining. Animals were relaxed for 1 min in a drop of 2% urethane in culture solution and fixed by pouring 99.5% ethanol. Five minutes later, the animals were rinsed several times in distilled water to remove the ethanol and then stained with 0.05% toluidine blue in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5). The animals were rinsed several times to remove an excess of dye and dehydrated stepwise with 50, 75, and 95% ethanol and twice in 100% ethanol. The animals were cleared in xylene and mounted in DPX, a non-aqueous mounting medium (Fujisawa, 1992). Stained tentacles were observed under bright field and phase-contrast microscopy (Axiovert 100, Zeiss) equipped with a digital color camera (Olympus, DP70). Morphological observation and quantitative analysis of isolated battery cell complexes was carried out on DAPI counterstained macerates obtained as described below.

Feeding assay

Fifteen polyps either showing the inverted-cone (score 5) morphophysiology or untreated, were fed with living artemia or treated with GSH (10 μM). The feeding behavior and the GSH response were examined under a stereomicroscope equipped with a CCD camera (Olympus).

Macerates, BrdU assay, and assessment of apoptosis

Macerates

Hydra tissues were dissociated in a modified maceration solution containing glycerol: acetic acid: water (1:1:7) at room temperature. Identification of cell types was also done according to the classification given by David (1973). Through this method, every cell type can be easily identified and investigated.

BrdU assay

To estimate the cell proliferation rate, intact Hydra, untreated or treated with 25 nM SiO2NPs, were continuously incubated with 5 nM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) (Sigma) for 12, 24, 48 h. Animals were macerated as described above, immediately fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and the cells spread on microscope slides. Incorporation of BrdU in proliferating cells was detected by immunolocalization using mouse anti BrdU monoclonal antibody (1:500, Sigma), and Novolinker polymer detection system (Novocastra) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Epithelial and interstitial BrdU-labeled cells were observed and counted under bright field and phase-contrast microscopy (Axiovert 100, Zeiss) equipped with a digital color camera (Olympus, DP70).

Apoptosis

As apoptotic hallmark, pyknotic nuclei were evaluated by DAPI (4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining. Briefly, untreated and SiO2NPs treated polyps (24 h; 10, 25 nM) were macerated as above described. After extensive washing in PBS, macerates were stained with DAPI for 2 min and washed in PBS. Slides were observed with phase-contrast and fluorescent microscopy to detect pyknotic nuclei. Three hundred epithelial cells were counted for each treatment and the percentage of apoptotic nuclei was determined.

Estimation of the Silicon content by optical microscopy and by ICP-AES

Living Hydra exposed to Rhodamine-labeled SiO2NPs (25 nM) were observed under fluorescent microscopy after 24 h of treatment.

To estimate the intracellular Silicon, replicates of 150 Hydra were either exposed to 10 and 25 nM SiO2NPs (experiment) or maintained in culture solution (control) for 24 h. The incubations were carried out in 10 mL. Samples were washed and digested by the addition of HCl/HNO3 3:1 (v/v) solution. The incubation media were recovered and digested as for samples. The resulting solutions were directly analyzed to evaluate the Si concentration through elemental analysis that was carried out by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) with a Varian Vista AX spectrometer.

Hydra growth rates and regeneration

Growth curve

Groups of five Hydra (with one bud) were treated with 10, 25 nM of SiO2NPs for 24 h or untreated, washed, and the following day placed in 12-well plates (1 Hydra/well). Hydra were fed once daily for 18 days. The growth rate constants (k) for the three populations were determined, as previously described (Ambrosone et al., 2012), from ln(n/n0) = kt, where n is the number of animals at time t and n0 the number of animal at t0. For n/n0 = 2, t = T2, the doubling time of the population. T2 was determined by linear regression (Bosch and David, 1984).

Regeneration assay

Regeneration assay groups of 25 polyps were bisected in the upper gastric region and incubated in presence of 10 and 25 nM SiO2NPs. The regenerating polyps, monitored through a stereomicroscope, were grouped into three stages according to progressive tentacle morphogenesis (Ambrosone et al., 2012).

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA from treated and untreated animals was extracted using Trizol (Life Technologies) and further purified by silica-cartridge purification protocol from the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Ambion). RNA concentration was determined on the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). The first-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out by High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems), using 0.5 μg of DNA-free RNA in a final volume of 25 μl according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in 25 μl of reaction mixture consisting of 1× Express Sybr® GreenER qPCR SuperMix with premixed ROX (Invitrogen), serial cDNA dilutions, and 0.3 μM of each primer. The reactions were processed using the Step One Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystem) under the following fast cycling steps: initial denaturation for 2 min at 94°C, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 2 s and 59°C for 30 s. In addition, melting curves (20 min; from 59 to 90°C) were generated to check any spurious amplification products. To normalize RNA levels, Hydra Elongation factor 1α gene (HyEf-1α, GenBank Accession no. Z68181.1) was employed as internal calibrator. Nucleotide sequences and alignments were obtained from Hydra genome database1 and European Nucleotide Archive (ENA)2. Specific primers of Hydra homologs genes were designed using Primer3 software3 and are listed in the Table S1 in Supplementary Material). Gene expression was evaluated in SiO2NPs treated and untreated polyps; at least three technical repeats from three biological replicates were carried out. Herein, the delta–delta Ct (2−ΔΔCT) method, for comparing relative expression results between treatments, was applied (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

RNA-seq analysis

Prior to sequencing, RNA amount and quality were quantified by capillary electrophoresis on a microchip device (BioAnalyzer 2100, Agilent). Samples with the RNA integrity number (RIN) of at least nine were chosen for further analysis. RNA sequencing was carried out at the Institute of Applied Genomics (IGA, Udine, Italy) on an Illumina Genome Analyzer, Hi-Seq2000, performing 100 bp-paired end sequencing in a single lane according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The sequenced reads resulting from this run were separated into 12 libraries (representing three related but different projects) according to their indexes (de-multiplexing) and stored as FASTQ files. The SiO2NPs treated and control Hydra libraries yielded a total of 30 million reads. Specifically, these libraries included (in millions of reads): 13.5 and 16.5 for SiO2NPs treatment and control, respectively.

Raw RNA-Seq reads were trimmed according to base calling quality prior to analysis. Quality filtering was performed using FastQC4. Based on quality statistics, RNA-Seq reads were not trimmed (Phred scores >Q25). RNA-Seq reads were mapped to the reference using the BWA alignment program (Li and Durbin, 2009) according to default parameters5. A well annotated Hydra transcriptome, which has recently been deposited at the ENA under the project number PRJEB445 and with accession numbers from HAAC01000001–HAAC01045269 (Wenger and Galliot, 2013) was used as reference to calculate transcript coverage. Specifically, the coverage of each transcript (i.e., the number of reads mapped to it) was computed using BEDtools software. Counting the number of aligned reads per transcript per sample was performed BEDTools “multicov” tool with the −D flag, thus enabling counting of reads that were mapped to more than one transcript with the same primary alignment score. Raw read counts and normalized counts were extracted from files using the multicov option of BEDtools (Quinlan and Hall, 2010). The count data produced from mapped reads were then processed with the DESeq R package (Anders and Huber, 2010), which tests for differential expression based on the negative binomial distribution while normalizing the raw counts to account for variable library sizes. Differentially expressed (DE) genes were identified through comparison of a SiO2NP-treated sample to an untreated control as reference group. Comparisons were kept at a significance level cut-off of α = 0.05 adjusted to match a 20% false discovery rate using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. An additional minimum threshold of fold change of two was also used. A consensus list of DE genes was generated from the latter. The Blast2GO software suite (Gotz et al., 2008) was then used to predict transcript function and assign Gene Ontology (GO) terms (Ashburner et al., 2000; Gene Ontology, 2008) for significantly up and down regulated transcripts without annotation. Blast2GO parameters included BLASTX against the GenBank non-redundant (nr) database hosted by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)6 while applying a minimum E-value cut-off score of 1.0E−06 and retrieving a maximum of 30 blast hits for each transcript. GO functional terms and Interpro domain annotations to each of the mapped un-annotated sequences were conducted using the Blast2GO default parameter settings.

Results

Determination of toxicity endpoints

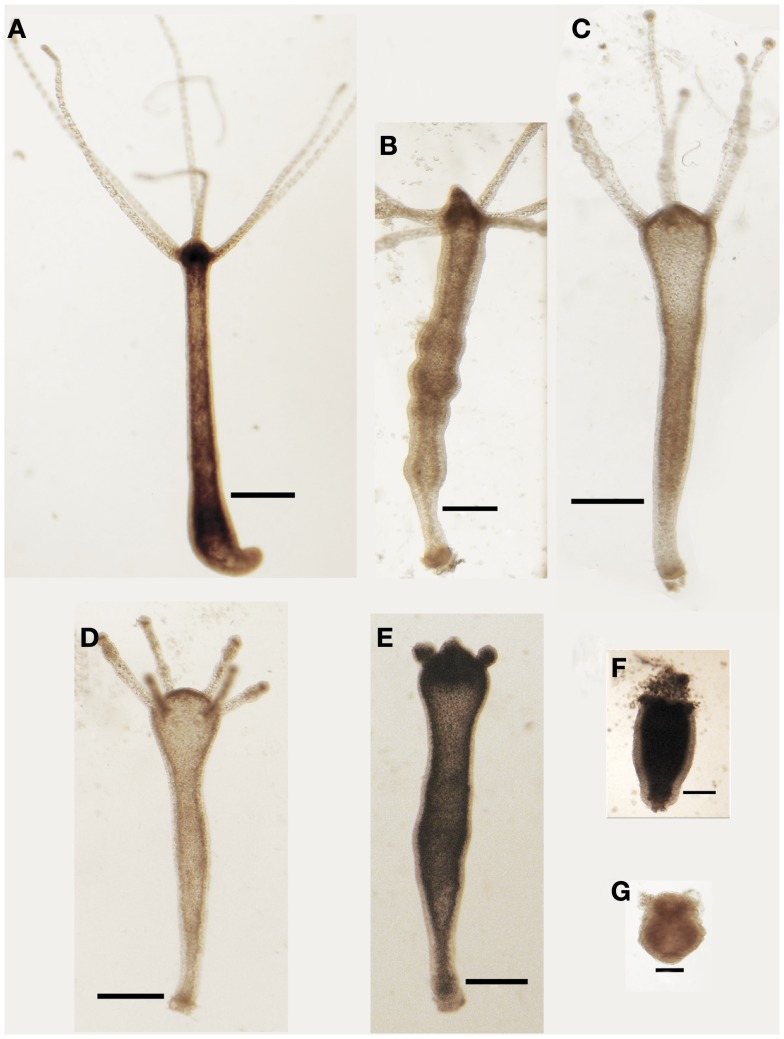

Living animals were soaked in culture medium supplemented with increasing SiO2NPs doses (from 10 to 50 nM) and monitored from 24 to 72 h of incubation; progressive morphological damages were observed, as shown by representative images of Figure 1. The treatment induced an inverted-cone shaped body, whitening, and paralysis, followed by whole polyp disintegration and death.

Figure 1.

Effects SiO2NPs treatment on Hydra morphology. Representative in vivo images of major features of morphological alterations (see Table 1) induced by continuous exposure to SiO2NPs are reported into the figures. Bar in (A–E), 1 mm; in (F,G), 0.5 mm.

We classified these new features using a new score key (Table 1) ranging from 7 (indicative of healthy condition) to 1 (damaged to death). In Table 1, the morphological, behavioral, and vital-states indicators toward the matching scores are described in detail.

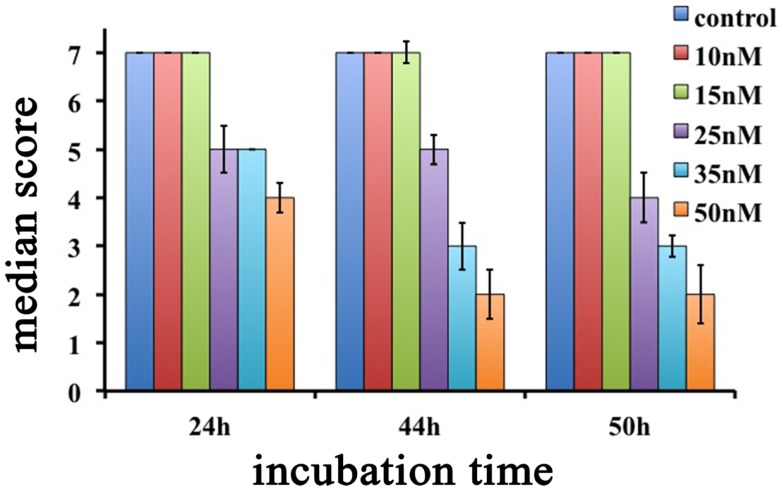

Interestingly, Hydra exhibiting scores 6, 5, and 4 were found able to revert to normal upon SiO2NPs removal, while those showing score 3, 2, and 1 were irreversibly damaged to death. SiO2NPs functionalized with NH2 groups were also tested within the same concentration range. These NPs, even at highest concentration, did not induce recognizable effects, paralleling with data obtained from cell culture experiments (Malvindi et al., 2012). According to the key described above, the dose and incubation time effects of SiO2NPs were analyzed (Figure 2). Up to reasonably high concentration (15 nM), even after prolonged exposure (72 h), no toxicity was detected (data not shown). By contrast, at 25 nM Hydra morphology and contractility were affected though able to revert to normal condition upon SiO2NPs withdrawal even after prolonged incubation times (72 h) (not shown). SiO2NPs doses above 35 nM severely affected Hydra morphology causing irreversible damages after prolonged incubation (above 40 h) up to animal death. In order to determine the lethal condition, morphological scores were further analyzed. The dose response experiments showed an all-or-nothing effect with a threshold of 35 nM SiO2NPs at 44 h: above this concentration, the scores drop below 3 (indicating animal death) while at lower concentrations and/or shorter incubation times, the polyps never reach the lethality. At the threshold condition (35 nM), we calculated the LT50 by applying the trimmed Spearman–Karber method, which offers good statistics, is easy to use, and is recommended for accurate and precise calculation of LT50 values and their 95% confidence interval end points (Hamilton et al., 1977). The estimated LT50 was 38 h (lower confidence 33 h upper confidence 44 h) clearly indicating a toxic effect around this temporal window.

Figure 2.

Dose response effects of SiO2NPs treatments on Hydra morphology are shown. Median scores were obtained from groups of 20 Hydra incubated for 24, 44, and 50 h with increasing concentrations of SiO2NPs from 10 to 50 nM.

Overall, the two different methods, based on morphophysiological changes and on lethality, enabled us to determinate sub-lethal doses to assess SiO2NPs sub-acute effects.

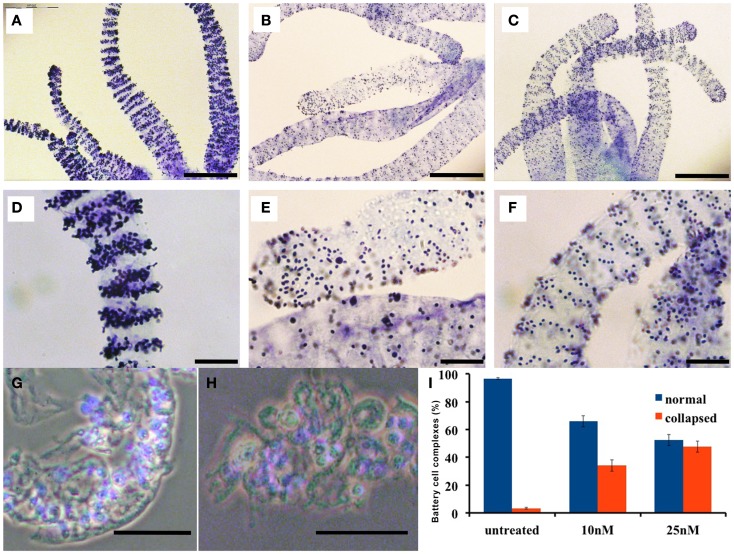

SiO2NPs affect distribution but not functionality of tentacle cells

In order to test whether anatomical and contractility modifications induced by SiO2NPs impaired also feeding behavior, we analyzed the ability of treated Hydra to catch the prey and respond to GSH. The feeding behavior starts with the prey capture by cnidocytes-armed tentacles followed by mouth opening and insertion of the prey-loaded tentacle into the mouth (Movie M1 in Supplementary Material). This multistep behavior can be mimicked by the tripeptide GSH. Within the 1–10 μM range, Hydra undergoes the GSH-response: during first step (10 s), a characteristic tentacles-writhing toward the central vertical axis of the animal takes place, followed by the second step when the tentacles bend toward the mouth culminating in mouth opening (30 s) (Movie M3 in Supplementary Material) (Lenhoff, 1961; Pierobon et al., 2001, 2004; Tortiglione et al., 2007). Treated Hydra (25 nM, 24 h) were challenged either with food (swimming Artemia salina nauplii) or GSH. In the presence of living nauplii, polyps thought paralyzed at gastric region and presenting the inverted-cone morphology, were still able to capture the prey; nevertheless, tentacles could not bend and mouth opening was prevented (Movie M2 in Supplementary Material). Similarly, the GSH response was impaired showing a slow tentacle-writhing activity, tentacle rigidity, and inhibition of mouth opening (Movie M4 in Supplementary Material). These results besides showing the feeding behavior impairment, revealed through the untangling of the prey capture from mouth opening that, as previously suggested by in vitro experiments (Thurm et al., 2004), the nematocysts discharge (the ability to catch the prey) is not sufficient to induce mouth opening. In addition, here we show that the ability of gastric region to contract must have a role in the accomplishment of feeding behavior. Since battery cell complexes are considered as the cellular correlates to food recognition, we analyzed the morphology of these cells in treated polyps by toluidine-blue staining and visualization of their nematocytes content and spatial distribution.

In normal Hydra, Toluidine-blue contrast highlights transversal punctuated stripes around the tentacles (Figures 3A,D), treated animals (inverted-cone stage corresponding to score 5) revealed a severe depletion of nematocytes, and a disorganization of the battery cells throughout the tentacles see Figures 3B,E. On Hydra macerates, the damaged battery cells lose the crescent-shaped morphology resulting shrunken, rounded, and reduced in dimension (see Figures 3G,H). In order to quantify the damage entity, we counted the number of collapsed battery cell complexes. The quantitative analysis showed that after 24 h of treatment, 50% of battery cell complexes lose their typical shape (Figure 3I). Remarkably, following SiO2NPs removal, Hydra rescues the anatomical and cellular features within 48 h (Figures 3C,F) while other important impaired traits (i.e., whitening and contractility of the gastric region) were restored even faster (1 h).

Figure 3.

Effects of SiO2NPs on tentacle structure are shown. Nematocytes, packed into tentacle battery cell complexes, were stained with toluidine blue. Battery cell complexes distribution in normal tentacles (A,D). Distribution of battery cell complexes in animals treated 24 h with 25 nM SiO2NPs (B,E). The abnormal distribution of the complexes is recovered within 48 h from stimulus removal as shown in (C,F). Effects of SiO2NPs on battery cell morphology cell. Isolated normal battery cell complex (G), battery cell complex from treated animal (H). (I) Quantitative estimation of the aberrant battery cells. The graph represents the percentage of collapsed battery cell complexes (red bar) at 10 and 25 nM SiO2NPs after 24 h incubation compared to control relative to a sample of 100 battery cells complexes; data are means of three independent experiments; vertical bars indicate the standard deviation. In (G–I), either treated and control animals were macerated and the nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Bar in (A–C) 200 μm; (D–H) 50 μm.

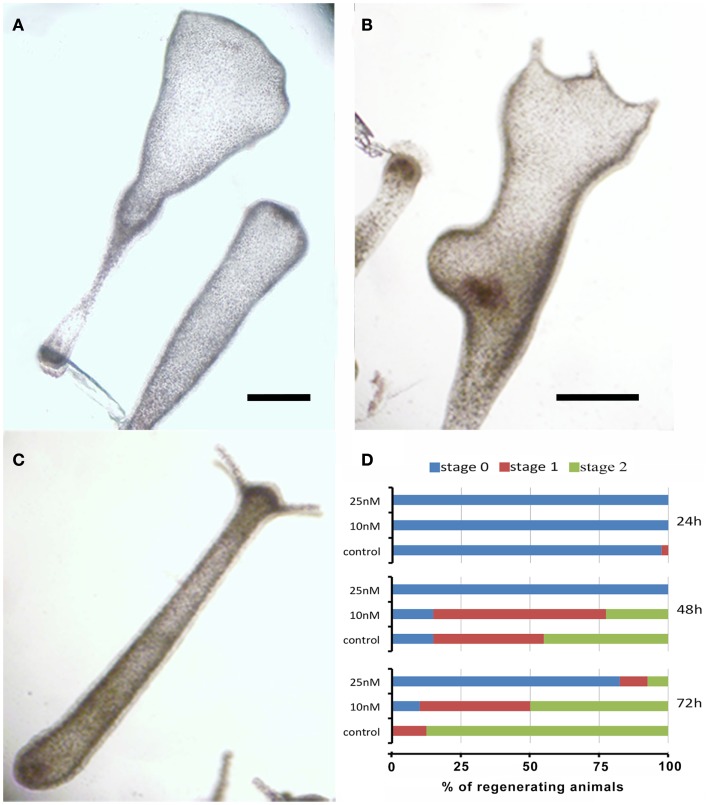

SiO2NPs treatments undermine Hydra regenerative potential

The remarkable capability of Hydra to regenerate missing body parts following amputation is controlled by tightly regulated processes, whose dynamics can be affected by environmental stress and profoundly altered due to failure of the differentiation, proliferation, and migration of different cell types. To test the effects of SiO2NPs on the polyp regeneration potential, treated adults were amputated at sub-hypostomal region and the head regeneration followed for 72 h in presence of SiO2NPs. The treatment severely impaired the morphology and kinetic of regeneration. Figures 4A,B show the aberrant process of treated polyps compared to control (Figure 4C); the graph in Figure 4D shows the distribution of the progressive regenerating stages: we found 50% impairment of regeneration process at 48 and 72 h post amputation (p.a.) at 10 nM, while at 25 nM, this percentage increased to 90, indicating a profound effect of SiO2NPs on this physiological process.

Figure 4.

Effects of SiO2NPs on Hydra regeneration. Forty eight-hours-regenerating Hydra treated with 25 nM SiO2NPs (A); 48 h-regenerating Hydra treated with 10 nM SiO2NPs (B); untreated 48 h-regenerating Hydra (C). In (D), the histogram shows the distribution of polyps developmental stages; stage 0 indicates absence of tentacles; stage 1 indicates the presence of tentacle buds; stage 2 indicates new emerging tentacles. Animals treated with 25 nM SiO2NPs are significantly impaired in the regeneration process. Data are means of three independent experiments. Twenty-five animals for each experiment were employed. Bar (A–C), 1 mm.

Internalized SiO2NPs are confined into the ectoderm and affects the cell proliferation/apoptosis balance

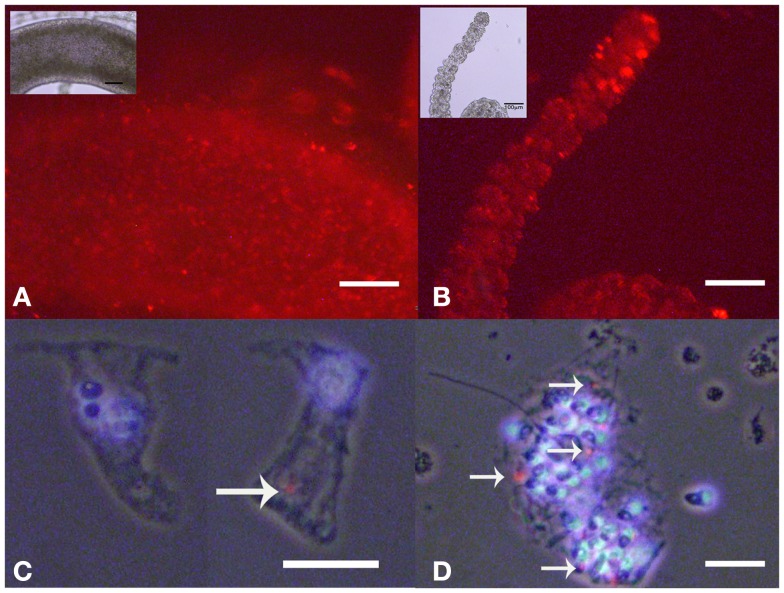

As internalized SiO2NPs in Hydra do not give any specific contrast under bright field or fluorescence microscope, imaging of the SiO2NPs internalization was carried out by fluorescently labeled SiO2NPs obtained by incorporating the dye Rhodamine B into the silica framework during the synthesis of the nanoparticles. Living Hydra were treated with 25 nM SiO2NPs labeled with rhodamine and, after 24 h, observed under fluorescent microscope. The fluorescence pattern appeared dotted and confined to the ectoderm along the tentacles and gastric region (Figures 5A,B).

Figure 5.

Living Hydra treated with 25 nM rhodamine-labeled-SiO2 NPs. Fluorescent microscopy in vivo images of gastric region (A) and tentacles (B); the insets are the corresponding bright field images. Localization of SiO2NPs on cell maceration of Hydra treated as above; epitheliomuscolar cell (C); battery cell complex (D). Nuclei are contrasted with DAPI; SiO2NPs/rhodamine (arrowed red spot) localize in the apical part of epithelial cell (C) or tied into the nematocytes inserted into the battery cell complex (D). (C,D) Phase contrast, DAPI, and rhodamine triple merged images. Bar in (A,B) 100 μm; in (C,D) 25 μm.

The analysis of isolated macerated cells confirmed that fluorescent SiO2NPs localize into the cytoplasm of ectodermal epithelial cells and battery cell complexes (Figures 5C,D, respectively). To estimate the internalization rate of SiO2NPs, we performed inductively coupled plasma spectroscopy (ICP) measurements; replicates of 150 Hydra were either exposed to SiO2NPs (experiment) or maintained in culture solution (control) for 24 h and processed for elemental analysis. The ICP measurement confirmed Silicon presence in Hydra, but showed similar internalization rate at both tested SiO2NPs concentrations (see Table 2). This suggesting that the dose response traits described above, might concern, besides the internalized moiety, an additional fraction of SiO2NPs acting extracellularly.

Table 2.

Content of Si (element) in treated Hydra and incubation medium (S/N). The data are expressed as nanomoles.

| SiO2NPs (nM) | Hydra | Medium |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 52.3 ± 3.6 | 272.7 ± 28.5 |

| 25 | 41.7 ± 0.8 | 614.6 ± 17.8 |

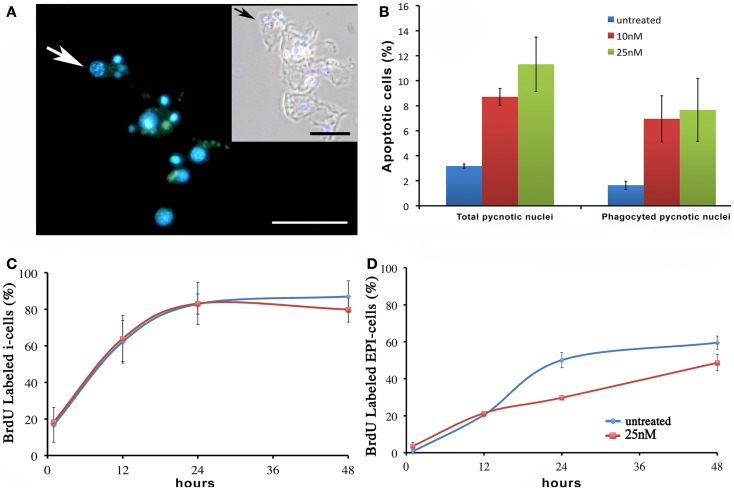

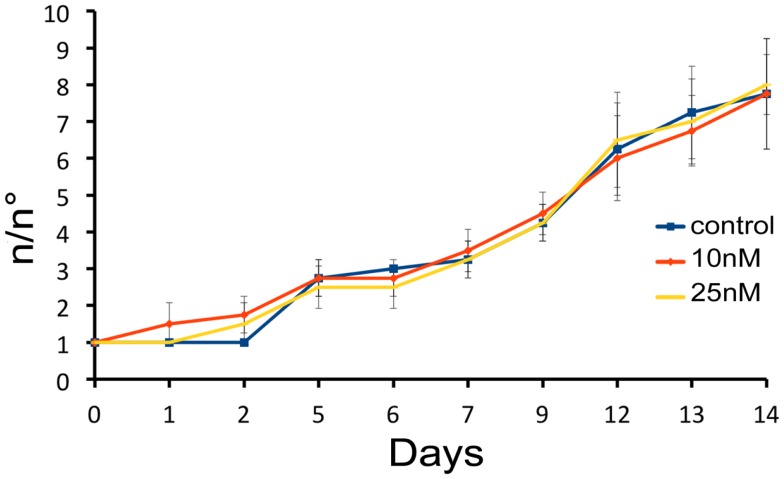

We next investigated the influence of SiO2NPs treatment on cell cycle and apoptotic/proliferating balance. DAPI counterstaining on treated Hydra showed that the amount of phagocytosed and pyknotic nuclei was about fourfold higher compared to untreated animals (Figures 6A,B). The proliferation assay by means of BrdU labeling showed that the SiO2NPs treatment does not influence interstitial cell proliferation (Figure 6C) while affecting this process in epithelial cells (Figure 6D) though limited at 24 h. As the cell proliferation may affect the reproductive rate of the polyp (occurring through mitotic asexual reproduction), we assessed whether the decreased epithelial cell proliferation could influence the population growth rate. To this aim, the progeny of five treated polyps (considered as the population founders), was monitored along 2 weeks, under normal feeding regime. As shown in Figure 7, treatments with two sub lethal SiO2NP doses (10 and 25 nM; 24 h) did not influence the population growth rate according to T2 of 4.8 days (day 14) and k values corresponding to 0.50, 0.45, 0.50, respectively to control, 10 and 25 nM treatments. These data indicate that short-term SiO2 treatment does not affect reproductive capabilities.

Figure 6.

Effect of SiO2NPs on cell proliferation and death. (A,B) Cellular assessment of apoptosis induction by SiO2NPs. Following 24 h in 25 nM SiO2NPs, polyps were macerated and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by counting the DAPI-stained fragmented nuclei [arrow in (A)]. Scale bar: 50 μm. Inset in (A): phase contrast–DAPI merged of the same image. The arrow in the inset shows a pyknotic nucleus. The graph in (B) shows the percentage of total pyknotic nuclei and phagocytic moiety in normal and treated conditions. Cell cycling activity of interstitial stem cells (i-cells) (C) and of epithelial cells (EPI) (D) were estimated in untreated and 25 nM SiO2NPs treated animals by continuous incubation with BrdU, followed by maceration of 10 animals at the indicated time points followed by colorimetric immunostaining. SiO2NPs impaired the proliferating activity of epithelial, as shown by the lower percentage of BrdU labeled nuclei. In (B–D) data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments; 100 cells were counted for each experiment.

Figure 7.

Effect of SiO2NPs on Hydra reproduction. Hydra population growth test. The graph shows n/n0 values at each time point. Where n is the total number of polyps, and n0 is the number of founder polyps.

SiO2NPs modulate the gene expression

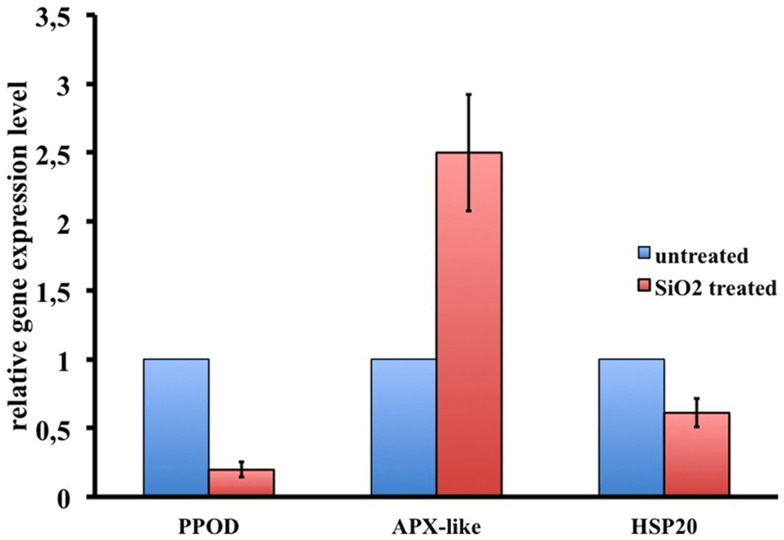

To dissect the genetic effects produced by SiO2NPs, we compared the global gene expression profiles of Hydra treated with sub-lethal dose (25 nM, 24 h) of nanoparticles versus control Hydra. Groups of 25 Hydra showing the inverted-cone morphology (score 5) or untreated were processed for RNA extraction and deep sequencing-based transcriptome analysis by RNAseq technology (Illumina). To calculate transcript coverage and differential gene expression, we employed, as reference, the annotated Hydra transcriptome deposited at the ENA. Ninety-three percent of the 100 base pairs sequencing reads from SiO2NPs treated Hydra were found to be uniquely mapped on the reference set (see “Materials and Methods” for details). Comparative analysis of transcripts indicated 45 DE genes (DE) across treatments. Interestingly, the relatively small number of DE transcripts may denote a low genotoxicity of SiO2NPs. Among these genes, 29 transcripts were upregulated (2-fold to 25-fold) and 16 were down regulated (−2.2-fold to −5-fold). All DE transcripts, their related annotations and increasing or decreasing fold changes are reported in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Some of the modulated transcripts were annotated as related to cellular stress responses suggesting that the treatment effects can be transduced to the nucleus and influence the gene expression. In order to validate the RNAseq results, we selected three DE genes to be further analyzed by qRT-PCR on animals subjected to the same treatment. Figure 8 shows the relative expression level of ppod, apx-like, and hsp16.2 genes obtained by qRT-PCR experiments confirming the expression changes detected by RNAseq (Tables 3 and 4). Interestingly, among the validated transcripts, there is the ppod gene, encoding for the Hydra PPOD: a secreted protein of cuticle (Bottger et al., 2012). This is the first functional evidence for downregulation of the ppod gene in response to external stimulus and its potential involvement in morphological and behavioral stress-related changes.

Table 3.

The table reports the RNAseq results for DE genes with fold changes above 2 (upregulated genes).

| Sequence name | Annotation | Fold change |

|---|---|---|

| ENA|HAAC01032462|HAAC01032462.1 | Pg1 homology to homo sapiens | 25.26 |

| ENA|HAAC01025529|HAAC01025529.1 | Protein | 14.03 |

| ENA|HAAC01028000|HAAC01028000.1 | Orf16–lacz fusion protein | 14.03 |

| ENA|HAAC01044255|HAAC01044255.1 | 60s ribosomal protein l18 | 12.21 |

| ENA|HAAC01033821|HAAC01033821.1 | Conserved protein | 6.40 |

| ENA|HAAC01033389|HAAC01033389.1 | Glycosyl transferase (glycosyl transferase family 2) | 6.31 |

| ENA|HAAC01044227|HAAC01044227.1 | Elongation factor 1-gamma | 5.19 |

| ENA|HAAC01028897|HAAC01028897.1 | Pg1 homology to homo sapiens | 5.05 |

| ENA|HAAC01042994|HAAC01042994.1 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-2-like 1 | 4.75 |

| ENA|HAAC01042461|HAAC01042461.1 | Aminopeptidase n | 4.42 |

| ENA|HAAC01039586|HAAC01039586.1 | Conserved protein | 4.35 |

| ENA|HAAC01018639|HAAC01018639.1 | Conserved protein | 4.33 |

| ENA|HAAC01031633|HAAC01031633.1 | Ascorbate peroxidase-like | 4.04 |

| ENA|HAAC01030032|HAAC01030032.1 | Conserved protein | 4.03 |

| ENA|HAAC01029942|HAAC01029942.1 | Ribosomal protein l44 | 3.95 |

| ENA|HAAC01044395|HAAC01044395.1 | 40s ribosomal protein s4 | 3.72 |

| ENA|HAAC01044240|HAAC01044240.1 | Predicted: uncharacterized protein LOC100207688 | 3.71 |

| ENA|HAAC01044744|HAAC01044744.1 | Arminin-like peptide 27077 | 3.70 |

| ENA|HAAC01043749|HAAC01043749.1 | Predicted: uncharacterized protein LOC100211198 | 3.65 |

| ENA|HAAC01044188|HAAC01044188.1 | Predicted: uncharacterized protein LOC100207688 | 3.60 |

| ENA|HAAC01032676|HAAC01032676.1 | Predicted: uncharacterized protein LOC100200837 | 3.56 |

| ENA|HAAC01017557|HAAC01017557.1 | Ascorbate peroxidase-like | 3.19 |

| ENA|HAAC01043858|HAAC01043858.1 | Lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 2-like | 3.11 |

| ENA|HAAC01000451|HAAC01000451.1 | Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding prot 1 isoform x3 | 3.07 |

| ENA|HAAC01043989|HAAC01043989.1 | Predicted: uncharacterized protein LOC100207688 | 3.00 |

| ENA|HAAC01044084|HAAC01044084.1 | Predicted: uncharacterized protein LOC100203182 | 2.91 |

| ENA|HAAC01022047|HAAC01022047.1 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme e2 g2 | 2.90 |

| ENA|HAAC01045088|HAAC01045088.1 | tpa_exp: minicollagen 7 | 2.85 |

| ENA|HAAC01012792|HAAC01012792.1 | 60 kDa lysophospholipase | 2.34 |

The sequence names are referred to the deposited Hydra transcriptome at European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) with relative annotations and fold changes.

Table 4.

The table reports the RNAseq results for DE genes with fold changes below 0.5 (downregulated genes).

| Sequence Name | Annotation | Fold change |

|---|---|---|

| ENA|HAAC01029048|HAAC01029048.1 | Rhamnose-binding lectin-like | 0.44 |

| ENA|HAAC01040476|HAAC01040476.1 | Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein isoform x2 | 0.41 |

| ENA|HAAC01005216|HAAC01005216.1 | Gtp-binding protein rhes-like | 0.40 |

| ENA|HAAC01044402|HAAC01044402.1 | Ppod1 peroxidase | 0.39 |

| ENA|HAAC01043441|HAAC01043441.1 | Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | 0.38 |

| ENA|HAAC01003999|HAAC01003999.1 | Predicted: uncharacterized protein LOC101235185 | 0.37 |

| ENA|HAAC01019715|HAAC01019715.1 | Hsp16.2 | 0.34 |

| ENA|HAAC01029657|HAAC01029657.1 | Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | 0.33 |

| ENA|HAAC01043390|HAAC01043390.1 | Ppod2 | 0.30 |

| ENA|HAAC01031772|HAAC01031772.1 | DNAj homolog subfamily b member 4 | 0.30 |

| ENA|HAAC01018572|HAAC01018572.1 | Hsp16.2 | 0.28 |

| ENA|HAAC01009426|HAAC01009426.1 | Hypothetical protein DAPPUDRAFT_322288 | 0.27 |

| ENA|HAAC01024155|HAAC01024155.1 | Bag family molecular chaperone regulator 3-like | 0.27 |

| ENA|HAAC01031161|HAAC01031161.1 | Family 2 glycosyl transferase | 0.25 |

| ENA|HAAC01028344|HAAC01028344.1 | Predicted: uncharacterized protein LOC100203540 | 0.23 |

| ENA|HAAC01027133|HAAC01027133.1 | Hsp-16.2 | 0.18 |

The sequence names are referred to the deposited Hydra transcriptome at European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) with relative annotations and fold changes.

Figure 8.

RNAseq results validation by qRT-PCR. Relative expression levels of three selected genes are reported. Data represent mean ± SD of three technical repeats from three biological replicates.

Discussion

Previous results (Malvindi et al., 2012) suggest that SiO2NPs internalize into cultured cells and are biocompatible when used at low concentration (up to 2.5 nM). Here, we translated the study of SiO2NPs effects on an animal model analyzing the effects from 10 nM onward: a range reasonably higher in respect to in vitro experiments due to the required mode of NP administration, i.e., in addition to the animal culture medium. Dose response experiments indicated low toxicity up to 10 nM SiO2NPs; additionally, optical microscopy observation and ICP, indicated the ability of SiO2NPs to be internalized by ectodermal cells. Taken together, these results confirm the data produced in vitro (Malvindi et al., 2012). On the other hand, in the same experimental conditions (10 nM SiO2NPs), although in the absence of morphophysiological traits of toxicity, an increase in the apoptotic cell number and an impairment of the ability to regenerate amputated body region was observed. Nowak et al. (2014), in a recent paper, described as the internalization of SiO2NPs may activate survival mechanisms in cultured cells and how this reaction was mediated by augmented autophagy and not by apoptosis. These results suggest, for accurate toxicological investigations, that SiO2NPs can elicit effects even at sub lethal doses. Above 10 nM SiO2NPs, we observed worsening morphophysiological traits. Previous works, to measure the impact of toxicants on Hydra, used a score key based on progressive morphological alteration of animal anatomy that was employed to test water pollution, estrogens, and metal contamination (Wilby and Tesh, 1990; Ambrosone et al., 2012). Taking into account the new morphophysiological traits produced by SiO2NPs on Hydra, here we defined a new score key. The scores formed the raw data to obtain median values and LT50 and consequently delineate the lethal and sub-lethal incubation and concentration ranges. Through this analysis, we defined two frames of SiO2NPs toxicity in Hydra. At intermediate concentration (25 nM), sub lethal reversible effects were recorded as anatomical changes, impairment of feeding behavior, alterations of specialized cell morphology and organization, and global gene expression modulation. We set the inverted-cone (similar to a party hat) morphology as symptom of SiO2NPs sub-lethal toxicity. Remarkably, this condition resulted independent from the incubation time suggesting a low bioaccumulation of amorphous silica nanoparticles in in vivo experiments as described by other groups in in vitro studies (Gazzano et al., 2012). At higher concentration (35 nM) and after prolonged exposure (44 h), we observed irreversible effects and lethality. Interestingly, the sub-lethal toxicity traits do not show a linear correlation with the amount of internalized SiO2NPs. The discrepancy between morphophysiological effects and limited amount of SiO2NPs in Hydra tissues can be explained assuming that the nanoparticles interact with outer animal surface. Recent evidences report that the SiO2NPs in vitro toxicity is mediated by adsorption of nanoparticles to extracellular components as serum proteins (Napierska et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012). It has been demonstrated that the enormous nanoparticles surface area and their concentration of silanol groups enhance the binding of large quantities of proteins and other biomolecules (Izak-Nau et al., 2013). Here we suggest that, this interaction in the case of Hydra, takes place with the external cuticle, a thick multilayered extracellular matrix that selectively protect Hydra tissues from external agents. The subtraction of cuticle components by SiO2NPs, triggers the impairment of the homeostasis of Hydra/environment interface producing the inverted-cone condition described into results, this alters the equilibrium with external environment and influences basic functions as, for example, the effectiveness of feeding behavior and the hydrostatic pressure that mediate the spontaneous Hydra gastric region contractions. Nonetheless, the rather long LT50 could mean that, for about 38 h of continuous exposure to 35 nM SiO2NPs, Hydra can renew the cuticle components replenishing the cuticle components necessary to prevent the direct access of SiO2NPs to ectodermal epithelial cells. Anyway, prolonged exposition to high SiO2NPs concentration (44 h, SiO2NPs above 35 nM), acts irreversibly on Hydra tissue with extensive cell lysis and subsequent reduction of polyps size and irregular shape. Finally, as already described in cell culture experiments (Costantini et al., 2011) and paralleling the effects at the base of the hemolysis activity (Zhang et al., 2012), once extinguished the homeostatic potential of extracellular matrix machine, the direct contact of SiO2NPs with ectodermal epithelial cells, induces the rupture of the plasma membrane resulting in massive cell loss and animal death.

Notwithstanding the widespread use of SiO2NPs in cosmetics, medicine, and foods, a few experimental data are available to date on the effects of SiO2NPs on gene expression modulation (Nowak et al., 2014). We were interested to find at what extent the observed reversible effects elicited by SiO2NPs in Hydra had an echo on global gene expression levels. Transcriptome analysis showed a moderate effect of SiO2NPs treatment on gene expression confirming the overall low toxicity of SiO2NPs. Remarkably, among the genes whose expression was modulated by SiO2NPs treatment, we found out the ppod gene encoding the Hydra protein PPOD a well-known cuticle component (Bottger et al., 2012). Both RNAseq and qRT-PCR showed that the ppod gene transcript level decreases after SiO2NPs treatment. This secreted protein, shows hemagglutination activity and is supposed to be involved in organizing the cuticle glycosaminoglycans. This is a first evidence of ppod gene expression modulation in response to an external stimulus, and suggests a molecular counterpart of the observed morphophysiological modifications. Further studies will also clarify the mechanism underlying the down regulation of the ppod gene transcript as, for example, a putative negative feedback to the stress induced by SiO2NPs treatment. Since the transcriptome analysis was carried out after 24 h of treatments, the gene expression modulation can be considered a hallmark of early response to the toxic stimulus that form a first example of genes involved in dynamic regulation of Hydra with the aquatic environments in mild toxic condition (Nowak et al., 2014). To verify the robustness of RNAseq results, we further validated the expression level changes of the HSP20 and ascorbate peroxidase-like. These genes with other DE genes as, for example, the guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-2-like1 and lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein-2-like genes are connected with cellular response to chemical stimuli, toxicants, and apoptosis, reinforcing the hypotheses of SiO2NPs-induced cellular stress. Finally, in our RNA-seq analysis, a sizeable number of genes remain unknown, providing a valid source of functional information to be further investigated. Future experiments and data analysis will be necessary to place these genes in functional pathways as molecular correlates of the morphophysiological traits reported in this work.

Our results describe new biological impacts from nanoscale materials and the data provide useful evidences for the development of novel atlas for the prediction of effects of nanomaterial interaction with living organisms. These results suggest the necessity to screen multiple experimental models and to apply a wide range of tests to better describe the toxicity endpoints of any new nanomaterial.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://www.frontiersin.org/Journal/10.3389/fbioe.2014.00037/abstract

Acknowledgments

We thank Mario Guarracino for helpful suggestions and Giuseppe Marino for technical support. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Research Council of Italy (CNR), by Italy Israel Joint Innovation Program for Scientific and Technological Cooperation in R&D and by NanoReg project (EU FP7).

Footnotes

References

- Ambrosone A., Mattera L., Marchesano V., Quarta A., Susha A. S., Tino A., et al. (2012). Mechanisms underlying toxicity induced by CdTe quantum dots determined in an invertebrate model organism. Biomaterials 33, 1991–2000 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosone A., Tortiglione C. (2013). Methodological approaches for nanotoxicology using Cnidarian models. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 23, 207–216 10.3109/15376516.2012.747117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Huber W. (2010). Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106. 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M., Ball C. A., Blake J. A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J. M., et al. (2000). Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode H. (2011). Axis formation in hydra. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45, 105–117 10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch T. C., David C. N. (1984). Growth regulation in Hydra: relationship between epithelial cell cycle length and growth rate. Dev. Biol. 104, 161–171 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90045-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottger A., Doxey A. C., Hess M. W., Pfaller K., Salvenmoser W., Deutzmann R., et al. (2012). Horizontal gene transfer contributed to the evolution of extracellular surface structures: the freshwater polyp hydra is covered by a complex fibrous cuticle containing glycosaminoglycans and proteins of the PPOD and SWT (sweet tooth) families. PLoS ONE 7:e52278. 10.1371/journal.pone.0052278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini L. M., Gilberti R. M., Knecht D. A. (2011). The phagocytosis and toxicity of amorphous silica. PLoS ONE 6:e14647. 10.1371/journal.pone.0014647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David C. (1973). A quantitative method for maceration of hydra tissue. W. Roux’ Archiv. f. Entwicklungsmech. 171, 259–268 10.1007/BF00577724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa T. (1992). Homeostatic recovery of interstitial cell populations in Hydra. Dev. Biol. 150, 185–192 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90017-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galliot B., Quiquand M., Ghila L., De Rosa R., Miljkovic-Licina M., Chera S. (2009). Origins of neurogenesis, a Cnidarian view. Dev. Biol. 332, 2–24 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.05.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzano E., Ghiazza M., Polimeni M., Bolis V., Fenoglio I., Attanasio A., et al. (2012). Physicochemical determinants in the cellular responses to nanostructured amorphous silicas. Toxicol. Sci. 128, 158–170 10.1093/toxsci/kfs128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gene Ontology C. (2008). The gene ontology project in 2008. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D440–D444 10.1093/nar/gkm883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz S., Garcia-Gomez J. M., Terol J., Williams T. D., Nagaraj S. H., Nueda M. J., et al. (2008). High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 3420–3435 10.1093/nar/gkn176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnieri D., Malvindi M. A., Belli V., Pompa P. P., Netti P. (2014). Effect of silica nanoparticles with variable size and surface functionalization on human endothelial cell viability and angiogenic activity. J. Nanoparticle Res. 16, 10.1007/s11051-013-2229-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A., Russo R. C., Thurston R. V. (1977). Trimmed Spearman-Karber method for estimating median lethal concentrations in toxicity bioassays. Environ. Sci. Technol. 11, 714–719 10.1021/es60130a004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobmayer E., Holstein T. W., David C. N. (1990). Tentacle morphogenesis in hydra. 2. Formation of a complex between a sensory nerve-cell and a battery cell. Development 109, 897–904 [Google Scholar]

- Izak-Nau E., Voetz M., Eiden S., Duschl A., Puntes V. F. (2013). Altered characteristics of silica nanoparticles in bovine and human serum: the importance of nanomaterial characterization prior to its toxicological evaluation. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 10, 10.1186/1743-8977-10-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karntanut W., Pascoe D. (2002). The toxicity of copper, cadmium and zinc to four different Hydra (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa). Chemosphere 47, 1059–1064 10.1016/S0045-6535(02)00050-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhoff H. M. (1961). Activation of the feeding reflex in Hydra littoralis. I. Role played by reduced glutathione and quantitative assay of the feeding reflex. J. Gen. Physiol. 45, 331–344 10.1085/jgp.45.2.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T)(-Delta Delta C) method. Methods 25, 402–408 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis W. F., Lenhoff H. M. (1956). Growth and sexual differentiation of hydra in mass culture. J. Exp. Zool. 132, 555–573 10.1002/jez.1401320309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malvindi M. A., Brunetti V., Vecchio G., Galeone A., Cingolani R., Pompa P. P. (2012). SiO2 nanoparticles biocompatibility and their potential for gene delivery and silencing. Nanoscale 4, 486–495 10.1039/c1nr11269d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malvindi M. A., Carbone L., Quarta A., Tino A., Manna L., Pellegrino T., et al. (2008). Rod-shaped nanocrystals elicit neuronal activity in vivo. Small 4, 1747–1755 10.1002/smll.200800413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesano V., Hernandez Y., Salvenmoser W., Ambrosone A., Tino A., Hobmayer B., et al. (2013). Imaging inward and outward trafficking of gold nanoparticles in whole animals. ACS Nano 7, 2431–2442 10.1021/nn305747e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D. E., Bridge D. (2012). Hydra, the everlasting embryo, confronts aging. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 56, 479–487 10.1387/ijdb.113461dm [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napierska D., Thomassen L. C. J., Lison D., Martens J. A., Hoet P. H. (2010). The nanosilica hazard: another variable entity. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 7, 39. 10.1186/1743-8977-7-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak J. S., Mehn D., Nativo P., García C. P., Gioria S., Ojea-Jiménez I., et al. (2014). Silica nanoparticle uptake induces survival mechanism in A549 cells by the activation of autophagy but not apoptosis. Toxicol. Lett. 224, 84–92 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierobon P., Minei R., Porcu P., Sogliano C., Tino A., Marino G., et al. (2001). Putative glycine receptors in hydra: a biochemical and behavioural study. Eur. J. Neurosci. 14, 1659–1666 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01792.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierobon P., Sogliano C., Minei R., Tino A., Porcu P., Marino G., et al. (2004). Putative NMDA receptors in hydra: a biochemical and functional study. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 2598–2604 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03759.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A. R., Hall I. M. (2010). BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggieri R. D., Pierobon P., Kass-Simon G. (2004). Pacemaker activity in hydra is modulated by glycine receptor ligands. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 138, 193–202 10.1016/j.cbpb.2004.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurm U., Brinkmann M., Golz R., Holtmann M., Oliver D., Sieger T. (2004). Mechanoreception and synaptic transmission of hydrozoan nematocytes. Hydrobiologia 530, 97–105 10.1007/978-1-4020-2762-8_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tortiglione C., Quarta A., Malvindi M. A., Tino A., Pellegrino T. (2009). Fluorescent nanocrystals reveal regulated portals of entry into and between the cells of Hydra. PLoS ONE 4:e7698. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortiglione C., Quarta A., Tino A., Manna L., Cingolani R., Pellegrino T. (2007). Synthesis and biological assay of GSH functionalized fluorescent quantum dots for staining Hydra vulgaris. Bioconjug. Chem. 18, 829–835 10.1021/bc060355t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger Y., Galliot B. (2013). RNAseq versus genome-predicted transcriptomes: a large population of novel transcripts identified in an Illumina-454 Hydra transcriptome. BMC Genomics 14, 10.1186/1471-2164-14-204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall J. A., Kinnamon J. C. (1984). Perioral synaptic connections and their possible role in the feeding behavior of Hydra. Tissue Cell 16, 355–365 10.1016/0040-8166(84)90055-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilby O. K., Tesh J. M. (1990). The Hydra assay as an early screen for teratogenic potential. Toxicol. In vitro 4, 582–583 10.1016/0887-2333(90)90119-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. Y., Dunphy D. R., Jiang X. M., Meng H., Sun B. B., Tarn D., et al. (2012). Processing pathway dependence of amorphous silica nanoparticle toxicity: colloidal vs pyrolytic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 15790–15804 10.1021/ja304907c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.