Abstract

Schizophrenia is thought to arise due to a complex interaction between genetic and environmental factors during early neurodevelopment. We have recently shown that partial genetic deletion of the schizophrenia susceptibility gene neuregulin 1 (Nrg1) and adolescent stress interact to disturb sensorimotor gating, neuroendocrine activity and dendritic morphology in mice. Both stress and Nrg1 may have converging effects upon N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) which are implicated in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, sensorimotor gating and dendritic spine plasticity. Using an identical repeated restraint stress paradigm to our previous study, here we determined NMDAR binding across various brain regions in adolescent Nrg1 heterozygous (HET) and wild-type (WT) mice using [3H] MK-801 autoradiography. Repeated restraint stress increased NMDAR binding in the ventral part of the lateral septum (LSV) and the dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus irrespective of genotype. Partial genetic deletion of Nrg1 interacted with adolescent stress to promote an altered pattern of NMDAR binding in the infralimbic (IL) subregion of the medial prefrontal cortex. In the IL, whilst stress tended to increase NMDAR binding in WT mice, it decreased binding in Nrg1 HET mice. However, in the DG, stress selectively increased the expression of NMDAR binding in Nrg1 HET mice but not WT mice. These results demonstrate a Nrg1-stress interaction during adolescence on NMDAR binding in the medial prefrontal cortex.

Keywords: schizophrenia, neuregulin 1, adolescence, stress, NMDA, medial prefrontal cortex, lateral septum, hippocampus

Introduction

Schizophrenia is thought to arise due to a complex interaction between genetic and environmental factors during critical early periods of neurodevelopment that result in disease onset in late adolescence/early adulthood (Weinberger, 1987; Murray et al., 1991; Lewis and Levitt, 2002; Van Winkel et al., 2008; Jaaro-Peled et al., 2009; Van Winkel et al., 2010; Van Os et al., 2010). Ionotropic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) mediate activity-dependent plasticity of glutamatergic synapses (Wenthold et al., 2003; Bennett, 2009) and play a key role in normal brain development through regulation of memory, attention and learning processes (Hudspith, 1997; Lieth et al., 2001; Bennett, 2009; Kantrowitz and Javitt, 2010).

Hypofunction of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the form of abnormal functioning of NMDARs in corticolimbic regions of the brain may explain the symptoms of schizophrenia (Carlsson and Carlsson, 1990; Bennett, 2009). For example, the administration of NMDAR antagonists such as phencyclidine (PCP) to humans induces most of the positive and negative symptom, as well as cognitive impairments observed in schizophrenia patients (Javitt, 1987). Similarly, administration of NMDAR antagonists like MK-801 in rodents, particularly during neurodevelopment, promotes lasting schizophrenia-relevant behavioral phenotypes such as locomotor hyperactivity, prepulse inhibition of startle (PPI) deficits, social withdrawal and cognitive dysfunction (Facchinetti et al., 1993; Sircar, 2000; Wang et al., 2001; Harris et al., 2003; Wiley et al., 2003; Andersen and Pouzet, 2004; Stefani and Moghaddam, 2005; Du Bois et al., 2008). Furthermore, post-mortem schizophrenia brain tissue studies have reported an increased binding of the radiolabelled NMDAR ligand MK-801 in the frontal cortex and caudate-putamen (Kornhuber et al., 1989; Newell et al., 2005). Although, reduced NMDAR sub-unit expression has recently been reported in schizophrenia brains which was accompanied by a reduced concentration of NMDA (Errico et al., 2013).

The neurotrophic factor neuregulin 1 (NRG1), is a widely accepted schizophrenia susceptibility gene which plays a significant role in normal brain maturation by influencing neuronal migration, myelination, and synaptic plasticity (Pearce et al., 1987; McDonald and Johnston, 1990; Stefansson et al., 2002; Harrison and Law, 2006; Mei and Xiong, 2008; Barros et al., 2009; Bennett, 2009, 2011). Interestingly, schizophrenia patients show altered expression of both the ErbB family of receptors for NRG1 and NMDARs (Stefansson et al., 2002; Chong et al., 2008; Alaerts et al., 2009; Hatzimanolis et al., 2013). The shared regulation of neuronal plasticity through the Nrg1-ErbB receptor and NMDARs systems has been demonstrated through an interaction in the post synaptic density (PSD) via the anchoring protein PSD-95 (Garcia et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2000; Bao et al., 2004; Murphy and Bielby-Clarke, 2008). Interestingly partial genetic deletion of Nrg1 hypophosphorylates NR2B subunits of NMDARs (Bjarnadottir et al., 2007) and promotes subtle changes in NMDAR binding in a number of schizophrenia relevant brain regions in adult rodents (Dean et al., 2008; Long et al., 2013; Newell et al., 2013).

Schizophrenia etiology also consists of an environmental component. Early life stress might be the common denominator linking several environmental risk factors including urbanicity, cannabis use, migration, childhood trauma and obstetric complications (Geddes and Lawrie, 1995; Dalman, 2003; Myin-Germeys et al., 2003; Corfas et al., 2004; Glaser et al., 2006; Henquet et al., 2008; Walker et al., 2008; Van Os et al., 2010). Indeed, adolescence is a period of heightened risk to develop schizophrenia (Walker and Bollini, 2002; Costello et al., 2003; Paus et al., 2008). Increased stress reactivity during adolescence coincides with normal maturation of cognitive abilities, and rapid development of the prefrontal cortex (Leussis et al., 2008; Rahdar and Galvan, 2014) and stabilization of the hippocampus (Leussis et al., 2008). Both the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus are vulnerable to the negative effects of stress (Jinks and McGregor, 1997; Sullivan and Gratton, 1999; Buijs and Van Eden, 2000; McEwen, 2007). Moreover, these regions display schizophrenia brain pathology such as a reduced density of dendritic spines, small protrusions which support excitatory synapses in neuronal circuits (Weinberger and Lipska, 1995; Velakoulis et al., 1999; Eichenbaum, 2000; Glantz and Lewis, 2000; Preston et al., 2005; Von Bohlen Und Halbach et al., 2006; Lawrie et al., 2008; Ebdrup et al., 2010). Stress hormone exposure during adolescence in mice, alters the expression of NMDAR subunits in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus (Lee et al., 2003; Sterlemann et al., 2010; Buret and Van Den Buuse, 2014), regions that regulate cognitive and sensorimotor gating, and are sensitive to stress-induced loss of dendritic spine density and gray matter losses (Kassem et al., 2013). No prior study has directly examined the effects of adolescent restraint stress on [3H] MK-801 binding in rodents. In adult rats chronic variable stress increased [3H] MK-801 binding in the prefrontal cortex and decreased binding in the hippocampus (Lei and Tejani-Butt, 2010). Given that both neuregulin and stress impact upon NMDARs in their own right, this opens the possibility that neuregulin might confer vulnerability to the effects of stress on NMDAR expression.

Nrg1 confers vulnerability to the effects of environmental challenges of relevance to schizophrenia. Our laboratory has shown that partial genetic deletion of neuregulin 1 increases sensitivity to the neurobehavioral actions of cannabinoids (Boucher et al., 2007a,b, 2011; Long et al., 2010, 2012, 2013; Spencer et al., 2013) and methamphetamine (Spencer et al., 2012), both of which are drugs of abuse known to activate stress systems in the brain including the HPA axis (Gerra et al., 2003; Huizink et al., 2006; King et al., 2010; Van Leeuwen et al., 2011). We and others have also recently demonstrated that genetic variation in Nrg1 confers vulnerability to the neurobehavioral effects of stress and modifies neuronal signaling pathways sub serving the stress response. For example, rats heterozygous for type II Nrg1 display altered expression of glucocorticoid receptors in the pituitary, hippocampus and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (Taylor et al., 2010). Partial genetic deletion of Nrg1 conferred vulnerability to the effects of adolescent social defeat stress on spatial working memory function and modulation of inflammatory cytokines in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus (Desbonnet et al., 2012). We have also recently shown that partial genetic deletion of Nrg1 altered neurobehavioral responses to repeated adolescent restraint stress (Chohan et al., 2014). Repeated adolescent stress selectively impaired the development of normal sensorimotor gating in Nrg1 heterozygous (Nrg1 HET) mice which correlated with a dysregulation in stress-induced corticosterone release. Furthermore, pyramidal neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex of Nrg1 HET mice exposed to repeated adolescent restraint stress had shorter dendritic lengths and complexity, as well as an increased dendritic spine density. Here we hypothesize that repeated restraint stress, coupled with disrupted Nrg1-ErbB4 signaling during adolescence, might interact to alter NMDAR binding in the mouse brain.

Methods

Mice

Adolescent (PND 35-49) male Nrg1 HET mice (C57BL/6JArc background strain) and wild-type (WT) littermates were used. The mice were bred in our animal house, sourced from a total of 9 litters and intermixed at weaning on postnatal day (PND) 21. Genotypes were determined after weaning at PND 21 as previously described (Karl et al., 2007). The mice were housed (4–5 animals per homecage) in a room on a 12:12 h light:dark reverse light schedule with food and water available ad libitum. Animals had access to environmental enrichment including a cardboard toilet roll, igloo, sunflower seeds, tissue paper and running wheels. Environmentally enriched housing is beneficial when exploring gene and environment interactions (G × E) in mice because it better approximates human cognitive and sensorimotor development than standard housing (Burrows et al., 2011). Nrg1 HET mice were generated by Prof Richard Harvey (Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute, Sydney) using a targeting vector in which most of exon 11, which encodes the transmembrane domain, was replaced by a neomycin resistance gene cassette (Stefansson et al., 2002). All research and animal care procedures were approved by the University of Sydney's Animal Ethics Committee and were in agreement with the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and use of Animals for Scientific Purposes.

Experimental design

Male mice were subjected to 30 min/day of restraint stress for 14 days from PND 36 to PND 49 as described in our previous study (Chohan et al., 2014). Restraint stress was chosen as it is a well-characterized physical stressor in rodents that activates the HPA axis and increases anxiety-related behavior (Eiland and McEwen, 2010; Sutherland et al., 2010; Sutherland and Conti, 2011; Chesworth et al., 2012). Non-stressed animals (WT and Nrg1 HET) did not receive restraint stress and remained undisturbed in their homecages, similar to prior methods (Eiland and McEwen, 2010; Eiland et al., 2012; Hill et al., 2013; Kwon et al., 2013). Stressed mice were placed in a restraint device (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA), which consisted of a close-ended clear perspex cylinder (9.5 × 2.5 cm). Mice were handled daily for 7 days prior to the commencement of experimentation and randomly allocated to 4 experimental groups: (1) WT-no stress (WT NS, n = 6); (2) WT-stress (WT S, n = 7); (3) Nrg1 HET-no stress (Nrg1 HET NS, n = 6), and (4) Nrg1 HET-stress (Nrg1 HET S, n = 5). Homecage controls and restraint stressed animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation immediately following their final 30 min restraint stress episode on day 14 (PND 49) and their brains were extracted, snap frozen and stored at −80°C prior to sectioning.

NMDA receptor autoradiography

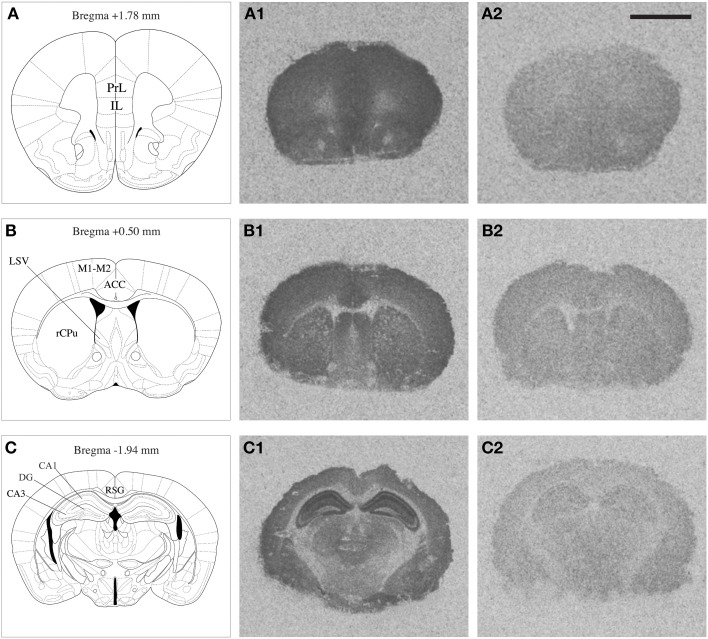

NMDAR autoradiography was conducted on brains extracted from the same mice that were used to determine corticosterone levels reported previously by our research group (Chohan et al., 2014). In these mice a differential effect of repeated stress was observed between Nrg1 HET and WT mice on plasma corticosterone concentrations. The whole brain was coronally sectioned at 20 μm on a cryostat, thaw-mounted onto polysine slides and stored at −80°C until use. Brain regions selected for quantification were identified based on a standard mouse brain atlas (Paxinos, 2004) at bregma levels +1.78 [containing prelimbic (PrL) and infralimbic (IL) cortices); +0.50 (containing anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), rostral caudate-putamen (rCPu), motor cortex (M1-M2), ventrolateral septum (LSV)]; and −1.94 (containing retrosplenial granular cortex (RSG), and subregions of the hippocampus including dentate gyrus (DG), CA1 (cornu ammonis area 1) and CA3 (cornu ammonis area 3) stratum radiatum layers (Figure 1). Our prior work showed that Nrg1 hypomorphism alone and in combination with stress affected dendritic morphology in the medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus (Chohan et al., 2014) and so these regions were consequently analyzed for MK-801 binding in the present study. Furthermore, the medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus are strongly implicated in the neurobiology of schizophrenia and stress (Michelsen et al., 2007; Radley et al., 2008; Alfarez et al., 2009). The caudal ACC region was examined, as it has been shown previously by our group to be affected by stress (Kassem et al., 2013) and is a point of comparison to another MK-801 binding study performed in Nrg1 HET mice (Newell et al., 2013). Further, we examined the LSV at it is thought to mediate stress and anxiety-related behavior (Dielenberg et al., 2001; Sheehan et al., 2004) and was shown to be dysregulated in our prior work on Nrg1-cannabinoid interactions (Boucher et al., 2007b, 2011).

Figure 1.

Mouse brain atlas adapted from Paxinos (2004), indicating the brain regions quantified (A,B,C); PrL: prelimbic cortex, IL: infralimbic cortex, rCPu: rostral caudate putamen, M1-M2: motor cortex, ACC: anterior cingulate cortex, LSV: ventrolateral septum, RSG: retrosplenial granular cortex, DG: dentate gyrus, CA1 and CA3 subregions of the hippocampus. Representative autoradiograms of coronal brain sections showing total [3H] MK-801 binding (A1,B1,C1) and non-specific [3H] MK-801 binding (A2,B2,C2). Scale bar = 2.5 mm.

The sections were incubated in 30 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.45) containing 23 nM [3H] MK-801 (specific activity 27.5 Ci/mmol, PerkinElmer, USA), 100 μM glycine, 100 μM L-glutamate and 1 mM EDTA for 2.5 h at room temperature. Non-specific binding was determined by incubating adjacent sections with [3H] MK-801 in the presence of 200 μM (ketamine hydrochloride, National Measurement Institute, Sydney, Australia). Following the incubation, the sections were washed twice for 20 min each at 4°C in 30 mM HEPES containing 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.45) and rapidly dried under a stream of cool air.

Quantitative analysis of autoradiographic images

Following the binding assays, all sections were placed on Kodak BioMax MR Film along with a [3H] autoradiographic standard (Amersham, UK) for 4 or 6 weeks. Some of the samples from the CA1 region of the hippocampus were re-exposed for 4 weeks due to initial oversaturation of the films, to allow them to fall within the normal pseudolinear response range. Films were developed using Kodak GBX developer/fixer (Sigma-Aldrich, NSW, Australia). Films were scanned using a BioRad GS-800 calibrated densitometer, and quantification of mean density performed in each brain region [average optical density over three adjacent brain sections, for total binding and non-specific binding, using ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij)]. Using density values for calibrated [3H] autoradiographic standards, radioactive concentrations were derived for all density values using a standard curve, and converted into fmol per mg tissue equivalent (fmol/mg). All regions quantified were analyzed blind to treatment group. Specific in vitro binding of [3H] MK-801 was calculated by subtraction of non-specific from total binding values. For each brain region, 6 frozen sections (3 total binding and 3 non-specific binding were selected per animal. Due to sectioning problems some of the sections were torn and unsuitable for processing. Therefore, for some of the brain regions the final value represents an average from five animals only.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM, IL, USA) or Statview (SAS Institute Inc) software. Statistically significant variation in radioligand binding was identified by Two-Way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with genotype or stress as factors. Planned Bonferroni comparisons were conducted to further analyze differences between experimental groups on all measures using the following four specific comparisons (WT-no stress vs. Nrg1 HET-no stress, WT-stress vs. Nrg1 HET-stress, WT-no stress vs. WT-stress, and Nrg1 HET-no stress vs. Nrg1 HET stress). The results of all analyses were deemed significant at p < 0.05.

Results

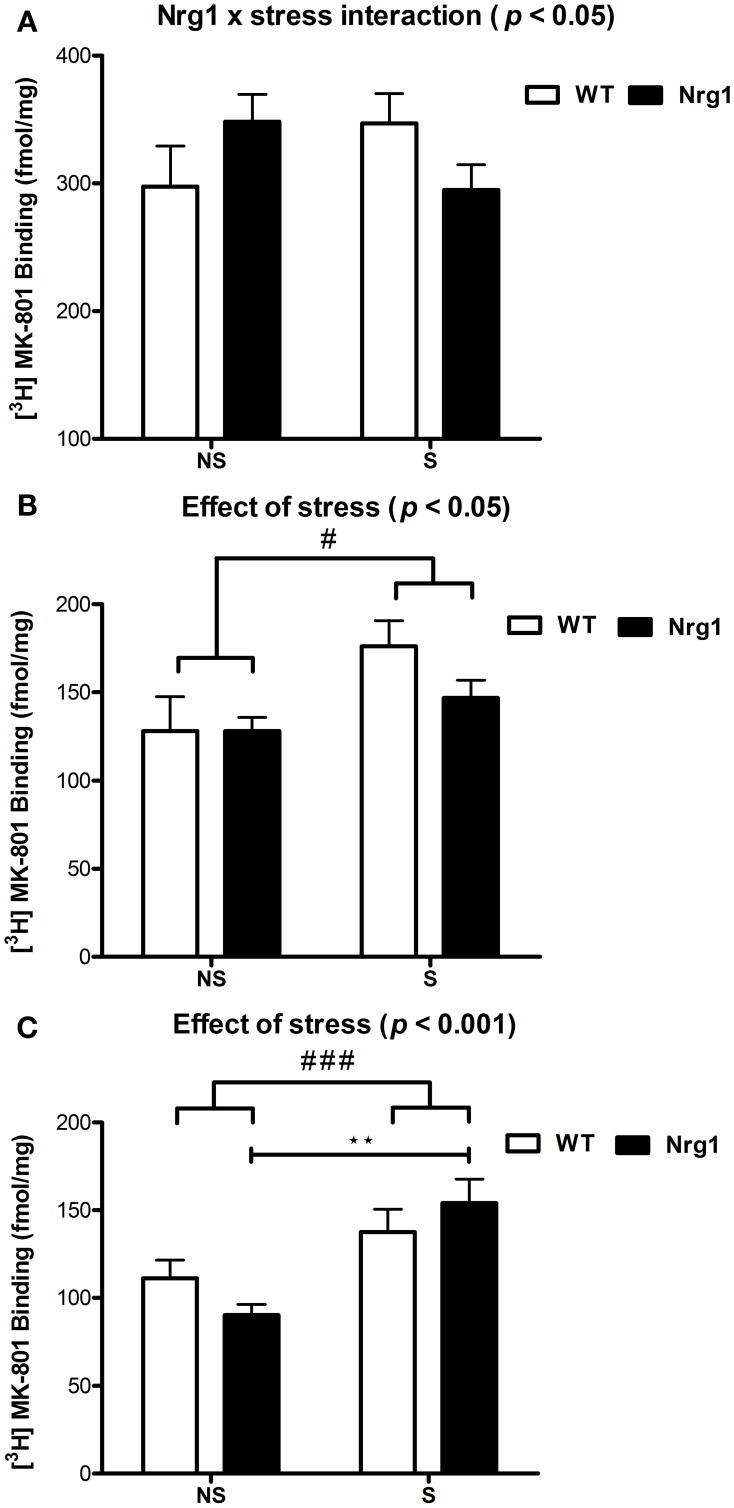

In all groups, the highest density of specific binding was distinctly observed in the hippocampus (CA1 & CA3 subregions). Moderately high levels of [3H] MK-801 binding were observed in the PrL, IL and anterior cingulate cortices. The rCPu, RSG, M1-M2, DG and LSV subdivisions displayed moderate-low levels of [3H] MK-801 binding. Two factor ANOVA revealed a significant genotype by stress interaction (F(1, 18) = 4.53, p < 0.05) in the IL cortex (Table 1, Figure 2A). A significant effect of stress was found for [3H] MK-801 binding in the LSV (F(1, 19) = 5.58, p < 0.05) and DG (F(1, 20) = 15.51, p < 0.001), demonstrating that restraint stress significantly increased NMDAR expression in these regions independent of genotype (Table 1 and Figure 2B). Planned Bonferroni comparisons revealed that stressed Nrg1 HET mice exhibited greater MK-801 binding in the DG compared with their non-stressed counterparts (p < 0.01). There were no main effects of genotype or stress, or genotype by stress interactions for NMDAR binding in any other brain regions examined (Table 1). No significant NMDAR binding differences between specific experimental groups in the other brain regions were observed (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Specific NMDAR binding densities in repeatedly stressed and non-stressed WT and Nrg1 HET mice.

| Brain | WT | Nrg1 HET | Two-Way ANOVA | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regions | No Stress | Stress | No Stress | Stress | Genotype | Condition | G × E | |||||||

| Mean | s.e.m. | Mean | s.e.m. | Mean | s.e.m. | Mean | s.e.m. | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | |

| PrL | 314.975 | ±26.642 | 342.732 | ± 22.813 | 349.642 | ±13.966 | 308.860 | ±23.018 | F(1, 18) = 0.0004 | 0.986 | F(1, 18) = 0.090 | 0.768 | F(1, 18) = 2.493 | 0.132 |

| IL | 297.697 | ±31.497 | 347.315 | ±23.179 | 348.422 | ±21.457 | 295.171 | ±19.492 | F(1, 18) = 0.001 | 0.977 | F(1, 18) = 0.006 | 0.941 | F(1, 18) = 4.527 | 0.047 |

| rCPu | 160.311 | ±18.842 | 200.519 | ±9.704 | 169.193 | ±11.588 | 160.594 | ±11.154 | F(1, 19) = 1.469 | 0.240 | F(1, 19) = 1.523 | 0.232 | F(1, 19) = 3.630 | 0.072 |

| M1-M2 | 247.933 | ±16.090 | 264.826 | ±9.768 | 236.519 | ±11.668 | 224.474 | ±20.893 | F(1, 19) = 3.223 | 0.088 | F(1, 19) = 0.028 | 0.868 | F(1, 19) = 1.007 | 0.328 |

| ACC | 291.354 | ±26.510 | 324.255 | ±16.283 | 281.255 | ±11.494 | 262.916 | ±14.381 | F(1, 20) = 3.744 | 0.067 | F(1, 20) = 0.156 | 0.697 | F(1, 20) = 1.926 | 0.181 |

| RSG | 171.369 | ±11.506 | 169.808 | ±14.702 | 143.954 | ±9.942 | 184.995 | ±16.380 | F(1, 20) = 0.207 | 0.654 | F(1, 20) = 2.156 | 0.158 | F(1, 20) = 2.511 | 0.129 |

| LSV | 127.992 | ±19.497 | 176.069 | ±14.489 | 128.175 | ±7.725 | 146.736 | ±10.233 | F(1, 19) = 1.068 | 0.314 | F(1, 19) = 5.584 | 0.029 | F(1, 19) = 1.095 | 0.308 |

| CA1 | 610.541 | ±27.062 | 619.457 | ±17.838 | 640.685 | ±23.267 | 678.384 | ±35.213 | F(1, 20) = 3.072 | 0.095 | F(1, 20) = 0.842 | 0.367 | F(1, 20) = 0.321 | 0.577 |

| CA3 | 459.248 | ±42.928 | 458.411 | ±41.408 | 416.045 | ±23.161 | 443.388 | ±32.370 | F(1, 19) = 0.640 | 0.434 | F(1, 19) = 0.133 | 0.720 | F(1, 19) = 0.150 | 0.703 |

| DG | 111.176 | ±10.369 | 137.475 | ±13.169 | 90.114 | ±6.194 | 153.924 | ±13.829 | F(1, 20) = 0.041 | 0.842 | F(1, 20) = 15.510 | 0.0008 | F(1, 20) = 2.688 | 0.117 |

Data expressed as mean fmol/mg tissue ± s.e.m. for all brain regions examined (n = 5–7/group). Significant values are highlighted in bold. PrL, prelimbic cortex; IL, infralimbic cortex; rCPu, rostral caudate putamen; M1-M2, motor cortex; ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; LSV, ventrolateral septum; RSG, retrosplenial granular cortex; DG, dentate gyrus; CA1 and CA3 subregions of the hippocampus.

Figure 2.

[3H] MK-801 binding to NMDARs (fmol/mg tissue) in (A) infralimbic cortex (IL), (B) ventrolateral septum (LSV) and (C) dentate gyrus (DG) in repeatedly stressed (S) and non-stressed (NS) wild type-like (WT) and Nrg1 HET mice; n = 5–7/group. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. Significant effects are indicated by #p < 0.05 and ###p < 0.001 (main effects of stress); **p < 0.01 [planned Bonferroni comparison, Nrg1 HET (NS) vs. Nrg1 HET (S)].

Discussion

Here we show that in adolescence partial genetic deletion of Nrg1 promoted an idiosyncratic change in medial prefrontal cortex NMDAR binding in response to repeated stress. Repeated stress exposure tended to decrease [3H] MK-801 binding in Nrg1 HET mice whilst promoting an increase in binding in WT mice in the IL cortex, a subregion of the medial prefrontal cortex. In the DG region of the hippocampus, stress significantly increased NMDAR binding. Interestingly, stressed Nrg1 HET mice displayed significantly higher NMDAR binding than non-stressed Nrg1 HET mice, an effect that was absent in WT mice. In addition, we report for the first time that restraint stress increased [3H] MK-801 binding levels in the LSV.

Partial genetic deletion of Nrg1 failed to significantly alter NMDAR binding in the other brain regions examined (PrL, rCPu, RSG, ACC, motor cortex & CA1/CA3 regions of the hippocampus) when measured in late adolescence (PND 49). Prior studies have shown that adult Nrg1 HET mice (> PND 60) display unaltered [3H] MK-801 binding in the cortex, caudate putamen, hippocampus and the septum (Dean et al., 2008; Long et al., 2013). Inconsistent with our present findings in late adolescent mice, adult Nrg1 HET mice exhibited increased NMDAR binding in the ACC and motor cortex compared to WT mice (Newell et al., 2013). The differences observed between the current study and the findings of Newell et al. (2013) may be explained by the different developmental period examined between the studies. As NMDARs undergo significant changes across development (Scheetz and Constantine-Paton, 1994; Cull-Candy et al., 2001; Haberny et al., 2002) and the locomotor hyperactivity phenotype of Nrg1 HET mice develops over time (Karl et al., 2007), it is possible that the effect of partial genetic deletion of Nrg1 on NMDAR binding might also follow a developmental trajectory and become significant in adulthood.

Here we show for the first time that repeated restraint stress in adolescence increased NMDAR binding in the LSV. The LSV is responsible for promoting active behavioral responses in stressful situations (De Oca and Fanselow, 2004; Sheehan et al., 2004) and its ablation provoked septal rage and exaggerated defensive behaviors (Brady and Nauta, 1953). These findings imply that the integrity of the lateral septum is vital for the inhibition of excessive fear and anxiety. New evidence however indicates that the role of the lateral septum in controlling fear and anxiety is more complex than this, as infusion of CRF type 2 receptor agonists or optogenetic transient activation of CRF type 2 receptors in the lateral septum promoted anxiety-related behaviors (Henry et al., 2006; Anthony et al., 2014). Little research has examined the role of NMDARs in the lateral septum in the control of defensive behaviors. NMDAR knockout mice display reduced aggressive behavior and swim-stress induced Fos expression in the lateral septum than WT mice (Duncan et al., 2009).

The ability to directly compare studies examining the effects of stress on NMDARs is limited by factors including the diversity of stress paradigms implemented, differences in post-stress washout periods, and the multitude of methods used to analyse NMDAR expression. Most studies have explored the effect of stress on NMDAR subunit protein & mRNA expression, rather than total NMDAR binding as measured with [3H] MK-801 autoradiography (Sterlemann et al., 2010; Buret and Van Den Buuse, 2014). No prior study has directly examined the effects of adolescent restraint stress on [3H] MK-801 binding in rodents. In adult rats chronic variable stress increased [3H] MK-801 binding in the prefrontal cortex, caudate putamen, nucleus accumbens and basolateral amygdala, while decreasing binding in the hippocampus (Lei and Tejani-Butt, 2010). Here we could only discern measurable effects of stress on the LSV and DG, which might be explained by our use of a relatively mild restraint stress paradigm (30 min per day for 14 days). To resolve the effects of stress on NMDAR binding in other brain regions might require a more intense stress regimen like the classic paradigm of 6 h per day for 21 days that reliably induces retraction of dendrites and loss of gray matter (Radley et al., 2004, 2006, 2008; Magarinos et al., 2011; Kassem et al., 2013). Alternatively, it is possible that earlier application of the stressor (i.e., from PND 28) might have been more effective as recent data suggests that peripubertal stressor exposure (i.e., encompassing the juvenile through to pubertal period, PND 28-42 in rats) is critical to provoking neurobiological changes in stress circuits including increased NMDAR expression (Tzanoulinou et al., 2014).

Using an identical adolescent stress protocol we recently reported that partial genetic deletion of Nrg1 and repeated stress interacted to offset the normal development of sensorimotor gating and blunted stress-induced corticosterone levels (Chohan et al., 2014). We also provided evidence of abnormal dendritic morphology in the medial prefrontal cortex of Nrg1 HET mice exposed to stress. Specifically, unlike WT mice whose dendritic morphology was unaffected by stress, repeated stress in Nrg1 HET mice reduced the length of dendrites and their complexity, and promoted an increase in dendritic spine density in pyramidal neurons of layers II/III of the anterior cingulate and PrL cortices of the medial prefrontal cortex. Given that Nrg1 and stress both influence NMDARs (Garcia et al., 2000; Bjarnadottir et al., 2007; Law et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007; Chong et al., 2008; Bennett, 2009; Cohen et al., 2010; Bennett et al., 2011; Buret and Van Den Buuse, 2014) and that NMDARs regulate the density of dendritic spines (Alvarez et al., 2007; Hayashi-Takagi et al., 2010) we hypothesized that Nrg1 and stress might interact to alter NMDAR binding specifically in the anterior cingulate and PrL cortices.

Therefore, it was surprising to observe in the present study that the Nrg1-stress interaction on NMDAR binding occurred in the IL cortex rather than the PrL cortex. The IL cortex shares reciprocal connections with the PrL cortex (Gabbott et al., 2003, 2005; Jones et al., 2005; Hoover and Vertes, 2007; Gutman et al., 2012) and the IL and PrL regions of the medial prefrontal cortex cooperate to produce an integrated response to stress (McDougall et al., 2004). Therefore, it is possible then that the changes in dendritic morphology in the anterior cingulate and PrL cortices in our previous study (Chohan et al., 2014) may be a cause or consequence of the Nrg1-stress interaction on NMDAR binding in the IL cortex we observed here. Indeed, perturbation of activity in the IL has flow on effects on the PrL cortex, as activation of IL cortex output via optical stimulation in adult rats inhibits PrL pyramidal neurons (Ji and Neugebauer, 2012). Here, there was a tendency toward reduced [3H] MK-801 binding in the medial prefrontal cortex of Nrg1 HET mice which accords with the general view of NMDAR hypofunction in schizophrenia as well as research showing that NMDAR expression is reduced in the schizophrenia brain (Errico et al., 2013). Although, this contradicts studies that report [3H] increased MK-801 binding in post-mortem schizophrenia brains (Kornhuber et al., 1989; Newell et al., 2005).

Here we report that repeated stress-induced increased NMDAR binding in the DG in Nrg1 HET mice but not in WT mice, which provides some additional support for Nrg1 HET mice being more sensitive to the effects of stress on NMDAR binding. However, this must be interpreted cautiously in the absence of an overall interaction between Nrg1 genotype and stress condition. The DG plays an important role in memory and sensorimotor gating function (Reul et al., 2009; Guo et al., 2013), thus the stress induced increase in NMDAR binding specifically in Nrg1 HET mice observed here may partially explain the spatial memory and PPI deficits observed previously in these mice following adolescent stress (Desbonnet et al., 2012; Chohan et al., 2014). Juvenile stress decreases expression of type III Nrg1 in the hippocampus (Brydges et al., 2014), so it is possible that the effects of stress on an already depleted Nrg1 level in hypomorphic mice is sufficient to then increase [3H] MK-801 binding. Why the DG but not the CA1 or CA3 region is selectively vulnerable to this effect is unclear. It might be partially explained by the DG expressing relatively lower levels of NRG1 than other hippocampal subfields (Law et al., 2004). The mechanisms responsible for the effect of stress on [3H] MK-801 binding in Nrg1 HET mice will need to be specifically addressed in future research including studies which directly examine the expression, internalization and phosphorylation status of NMDAR, and also whether this effect can be magnified by a more intense stress protocol.

Our findings further reinforce research showing that variation in Nrg1 confers vulnerability to the effects of stress. Human studies have shown that a NRG1 polymorphism interacted with psychosocial stress to effect reactivity to expressed emotions in schizophrenia patients (Keri et al., 2009) and that polymorphic variation in NRG1 interacts with job strain to increase the risk of heart disease (Hintsanen et al., 2007). Reduced type II Nrg1 expression in rats induced increased baseline corticosterone levels, a disruption in recovery of stress-induced plasma corticosterone concentrations, as well as elevated levels of glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland (Taylor et al., 2010). Further, complex gender specific interactions of type II Nrg1 genotype and adolescent chronic variable stress were reported on anxiety-related behavior and cued fear conditioning (Taylor et al., 2012). Stress-induced increase in corticosterone was more pronounced in Nrg1 HET mice than WT mice at the younger (3–4 months) but not the older age group (6–7 months) (Chesworth et al., 2012), highlighting the developmental effect of stress and Nrg1 hypomorphism on the HPA axis. Adolescent social defeat stress has also been shown to selectively impair spatial memory and decrease expression of the inflammatory cytokine interleukin 1β in the prefrontal cortex of Nrg1 HET mice, but not WT mice (Desbonnet et al., 2012). The latter finding might be related to the present finding of partial genetic deletion of Nrg1 promoting a unique stress-induced downregulation of NMDAR binding in the prefrontal cortex, as interleukin 1β (IL 1β) has been shown to potentiate NMDA function and reduce the density of synaptic spines (Viviani et al., 2003, 2006). Further, the effects of IL 1β are mediated by interleukin receptor 1 (ILR1) which appear to interact with NR2B subunits of the NMDAR in the postsynaptic density (Gardoni et al., 2011; Viviani et al., 2013).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a University of Sydney Bridging Grant to JCA.

References

- Alaerts M., Ceulemans S., Forero D., Moens L. N., De Zutter S., Heyrman L., et al. (2009). Support for NRG1 as a susceptibility factor for schizophrenia in a northern Swedish isolated population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 828–837 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfarez D. N., De Simoni A., Velzing E. H., Bracey E., Joels M., Edwards F. A., et al. (2009). Corticosterone reduces dendritic complexity in developing hippocampal CA1 neurons. Hippocampus 19, 828–836 10.1002/hipo.20566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez V. A., Ridenour D. A., Sabatini B. L. (2007). Distinct structural and ionotropic roles of NMDA receptors in controlling spine and synapse stability. J. Neurosci. 27, 7365–7376 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0956-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J. D., Pouzet B. (2004). Spatial memory deficits induced by perinatal treatment of rats with PCP and reversal effect of D-serine. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 1080–1090 10.1038/sj.npp.1300394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony T. E., Dee N., Bernard A., Lerchner W., Heintz N., Anderson D. J. (2014). Control of stress-induced persistent anxiety by an extra-amygdala septohypothalamic circuit. Cell 156, 522–536 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao J., Lin H., Ouyang Y., Lei D., Osman A., Kim T. W., et al. (2004). Activity-dependent transcription regulation of PSD-95 by neuregulin-1 and Eos. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 1250–1258 10.1038/nn1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros C. S., Calabrese B., Chamero P., Roberts A. J., Korzus E., Lloyd K., et al. (2009). Impaired maturation of dendritic spines without disorganization of cortical cell layers in mice lacking NRG1/ErbB signaling in the central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4507–4512 10.1073/pnas.0900355106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M. (2009). Positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: the NMDA receptor hypofunction hypothesis, neuregulin/ErbB4 and synapse regression. Aust. N.Z. J. Psychiatry 43, 711–721 10.1080/00048670903001943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M. R. (2011). Schizophrenia: susceptibility genes, dendritic-spine pathology and gray matter loss. Prog. Neurobiol. 95, 275–300 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M. R., Farnell L., Gibson W. G. (2011). A model of neuregulin control of NMDA receptors on synaptic spines. Bull. Math. Biol. 74, 717–735 10.1007/s11538-011-9706-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnadottir M., Misner D. L., Haverfield-Gross S., Bruun S., Helgason V. G., Stefansson H., et al. (2007). Neuregulin1 (NRG1) signaling through Fyn modulates NMDA receptor phosphorylation: differential synaptic function in NRG1+/− knock-outs compared with wild-type mice. J. Neurosci. 27, 4519–4529 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4314-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher A. A., Arnold J. C., Duffy L., Schofield P. R., Micheau J., Karl T. (2007a). Heterozygous neuregulin 1 mice are more sensitive to the behavioural effects of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 192, 325–336 10.1007/s00213-007-0721-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher A. A., Hunt G. E., Karl T., Micheau J., McGregor I. S., Arnold J. C. (2007b). Heterozygous neuregulin 1 mice display greater baseline and Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol-induced c-Fos expression. Neuroscience 149, 861–870 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher A. A., Hunt G. E., Micheau J., Huang X., McGregor I. S., Karl T., et al. (2011). The schizophrenia susceptibility gene neuregulin 1 modulates tolerance to the effects of cannabinoids. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 14, 631–643 10.1017/S146114571000091X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady J. V., Nauta W. J. (1953). Subcortical mechanisms in emotional behavior: affective changes following septal forebrain lesions in the albino rat. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 46, 339–346 10.1037/h0059531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brydges N. M., Seckl J., Torrance H. S., Holmes M. C., Evans K. L., Hall J. (2014). Juvenile stress produces long-lasting changes in hippocampal DISC1, GSK3ss and NRG1 expression. Mol. Psychiatry 19, 854–855 10.1038/mp.2013.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs R. M., Van Eden C. G. (2000). The integration of stress by the hypothalamus, amygdala and prefrontal cortex: balance between the autonomic nervous system and the neuroendocrine system. Prog. Brain Res. 126, 117–132 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)26011-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buret L., Van Den Buuse M. (2014). Corticosterone treatment during adolescence induces down-regulation of reelin and NMDA receptor subunit GLUN2C expression only in male mice: implications for schizophrenia. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 17, 1221–1232 10.1017/S1461145714000121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows E. L., McOmish C. E., Hannan A. J. (2011). Gene-environment interactions and construct validity in preclinical models of psychiatric disorders. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 35, 1376–1382 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson M., Carlsson A. (1990). Schizophrenia: a subcortical neurotransmitter imbalance syndrome? Schizophr. Bull. 16, 425–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesworth R., Yulyaningsih E., Cappas E., Arnold J., Sainsbury A., Karl T. (2012). The response of neuregulin 1 mutant mice to acute restraint stress. Neurosci. Lett. 515, 82–86 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chohan T. W., Boucher A. A., Spencer J. R., Kassem M. S., Hamdi A. A., Karl T., et al. (2014). Partial genetic deletion of neuregulin 1 modulates the effects of stress on sensorimotor gating, dendritic morphology, and hpa axis activity in adolescent mice. Schizophr. Bull. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1093/schbul/sbt193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong V. Z., Thompson M., Beltaifa S., Webster M. J., Law A. J., Weickert C. S. (2008). Elevated neuregulin-1 and ErbB4 protein in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenic patients. Schizophr. Res. 100, 270–280 10.1016/j.schres.2007.12.474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. W., Louneva N., Han L. Y., Hodes G., Wilson R. S., Bennett D. A., et al. (2010). Chronic corticosterone exposure alters postsynaptic protein levels of PSD-95, NR1, and synaptopodin in the mouse brain. Synapse 65, 763–770 10.1002/syn.20900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corfas G., Roy K., Buxbaum J. D. (2004). Neuregulin 1-erbB signaling and the molecular/cellular basis of schizophrenia. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 575–580 10.1038/nn1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello E. J., Mustillo S., Erkanli A., Keeler G., Angold A. (2003). Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60, 837–844 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull-Candy S., Brickley S., Farrant M. (2001). NMDA receptor subunits: diversity, development and disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11, 327–335 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00215-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalman C. (2003). [Obstetric complications and risk of schizophrenia. An association appears undisputed, yet mechanisms are still unknown]. Lakartidningen 100, 1974–1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean B., Karl T., Pavey G., Boer S., Duffy L., Scarr E. (2008). Increased levels of serotonin 2A receptors and serotonin transporter in the CNS of neuregulin 1 hypomorphic/mutant mice. Schizophr. Res. 99, 341–349 10.1016/j.schres.2007.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Oca B. M., Fanselow M. S. (2004). Amygdala and periaqueductal gray lesions only partially attenuate unconditional defensive responses in rats exposed to a cat. Integr. Physiol. Behav. Sci. 39, 318–333 10.1007/BF02734170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbonnet L., O'tuathaigh C., Clarke G., O'leary C., Petit E., Clarke N., et al. (2012). Phenotypic effects of repeated psychosocial stress during adolescence in mice mutant for the schizophrenia risk gene neuregulin-1: a putative model of gene x environment interaction. Brain Behav. Immun. 26, 660–671 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dielenberg R. A., Hunt G. E., McGregor I. S. (2001). “When a rat smells a cat”: the distribution of Fos immunoreactivity in rat brain following exposure to a predatory odor. Neuroscience 104, 1085–1097 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00150-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois T. M., Huang X. F., Deng C. (2008). Perinatal administration of PCP alters adult behaviour in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Behav. Brain Res. 188, 416–419 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G. E., Inada K., Farrington J. S., Koller B. H., Moy S. S. (2009). Neural activation deficits in a mouse genetic model of NMDA receptor hypofunction in tests of social aggression and swim stress. Brain Res. 1265, 186–195 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebdrup B. H., Glenthoj B., Rasmussen H., Aggernaes B., Langkilde A. R., Paulson O. B., et al. (2010). Hippocampal and caudate volume reductions in antipsychotic-naive first-episode schizophrenia. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 35, 95–104 10.1503/jpn.090049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H. (2000). A cortical-hippocampal system for declarative memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1, 41–50 10.1038/35036213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiland L., McEwen B. S. (2010). Early life stress followed by subsequent adult chronic stress potentiates anxiety and blunts hippocampal structural remodeling. Hippocampus 22, 82–91 10.1002/hipo.20862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiland L., Ramroop J., Hill M. N., Manley J., McEwen B. S. (2012). Chronic juvenile stress produces corticolimbic dendritic architectural remodeling and modulates emotional behavior in male and female rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37, 39–47 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errico F., Napolitano F., Squillace M., Vitucci D., Blasi G., De Bartolomeis A., et al. (2013). Decreased levels of D-aspartate and NMDA in the prefrontal cortex and striatum of patients with schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 47, 1432–1437 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facchinetti F., Ciani E., Dall'olio R., Virgili M., Contestabile A., Fonnum F. (1993). Structural, neurochemical and behavioural consequences of neonatal blockade of NMDA receptor through chronic treatment with CGP 39551 or MK-801. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 74, 219–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott P. L., Warner T. A., Jays P. R., Bacon S. J. (2003). Areal and synaptic interconnectivity of prelimbic (area 32), infralimbic (area 25) and insular cortices in the rat. Brain Res. 993, 59–71 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott P. L., Warner T. A., Jays P. R., Salway P., Busby S. J. (2005). Prefrontal cortex in the rat: projections to subcortical autonomic, motor, and limbic centers. J. Comp. Neurol. 492, 145–177 10.1002/cne.20738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia R. A., Vasudevan K., Buonanno A. (2000). The neuregulin receptor ErbB-4 interacts with PDZ-containing proteins at neuronal synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3596–3601 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardoni F., Boraso M., Zianni E., Corsini E., Galli C. L., Cattabeni F., et al. (2011). Distribution of interleukin-1 receptor complex at the synaptic membrane driven by interleukin-1beta and NMDA stimulation. J. Neuroinflammation 8:14 10.1186/1742-2094-8-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes J. R., Lawrie S. M. (1995). Obstetric complications and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 167, 786–793 10.1192/bjp.167.6.786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerra G., Bassignana S., Zaimovic A., Moi G., Bussandri M., Caccavari R., et al. (2003). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responses to stress in subjects with 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (“ecstasy”) use history: correlation with dopamine receptor sensitivity. Psychiatry Res. 120, 115–124 10.1016/S0165-1781(03)00175-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz L. A., Lewis D. A. (2000). Decreased dendritic spine density on prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 57, 65–73 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser J. P., Van Os J., Portegijs P. J., Myin-Germeys I. (2006). Childhood trauma and emotional reactivity to daily life stress in adult frequent attenders of general practitioners. J. Psychosom. Res. 61, 229–236 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo N., Yoshizaki K., Kimura R., Suto F., Yanagawa Y., Osumi N. (2013). A sensitive period for GABAergic interneurons in the dentate gyrus in modulating sensorimotor gating. J. Neurosci. 33, 6691–6704 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0032-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman D. A., Keifer O. P., Jr., Magnuson M. E., Choi D. C., Majeed W., Keilholz S., et al. (2012). A DTI tractography analysis of infralimbic and prelimbic connectivity in the mouse using high-throughput MRI. Neuroimage 63, 800–811 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberny K. A., Paule M. G., Scallet A. C., Sistare F. D., Lester D. S., Hanig J. P., et al. (2002). Ontogeny of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor system and susceptibility to neurotoxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 68, 9–17 10.1093/toxsci/68.1.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris L. W., Sharp T., Gartlon J., Jones D. N., Harrison P. J. (2003). Long-term behavioural, molecular and morphological effects of neonatal NMDA receptor antagonism. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18, 1706–1710 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02902.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P. J., Law A. J. (2006). Neuregulin 1 and schizophrenia: genetics, gene expression, and neurobiology. Biol. Psychiatry 60, 132–140 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzimanolis A., McGrath J. A., Wang R., Li T., Wong P. C., Nestadt G., et al. (2013). Multiple variants aggregate in the neuregulin signaling pathway in a subset of schizophrenia patients. Transl. Psychiatry 3:e264 10.1038/tp.2013.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi-Takagi A., Takaki M., Graziane N., Seshadri S., Murdoch H., Dunlop A. J., et al. (2010). Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) regulates spines of the glutamate synapse via Rac1. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 327–332 10.1038/nn.2487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henquet C., Di Forti M., Morrison P., Kuepper R., Murray R. M. (2008). Gene-environment interplay between cannabis and psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 34, 1111–1121 10.1093/schbul/sbn108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry B., Vale W., Markou A. (2006). The effect of lateral septum corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2 activation on anxiety is modulated by stress. J. Neurosci. 26, 9142–9152 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1494-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill M. N., Kumar S. A., Filipski S. B., Iverson M., Stuhr K. L., Keith J. M., et al. (2013). Disruption of fatty acid amide hydrolase activity prevents the effects of chronic stress on anxiety and amygdalar microstructure. Mol. Psychiatry 18, 1125–1135 10.1038/mp.2012.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintsanen M., Elovainio M., Puttonen S., Kivimaki M., Raitakari O. T., Lehtimaki T., et al. (2007). Neuregulin-1 genotype moderates the association between job strain and early atherosclerosis in young men. Ann. Behav. Med. 33, 148–155 10.1007/BF02879896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover W. B., Vertes R. P. (2007). Anatomical analysis of afferent projections to the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Struct. Funct. 212, 149–179 10.1007/s00429-007-0150-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. Z., Won S., Ali D. W., Wang Q., Tanowitz M., Du Q. S., et al. (2000). Regulation of neuregulin signaling by PSD-95 interacting with ErbB4 at CNS synapses. Neuron 26, 443–455 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81176-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudspith M. J. (1997). Glutamate: a role in normal brain function, anaesthesia, analgesia and CNS injury. Br. J. Anaesth. 78, 731–747 10.1093/bja/78.6.731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizink A. C., Ferdinand R. F., Ormel J., Verhulst F. C. (2006). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and early onset of cannabis use. Addiction 101, 1581–1588 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaaro-Peled H., Hayashi-Takagi A., Seshadri S., Kamiya A., Brandon N. J., Sawa A. (2009). Neurodevelopmental mechanisms of schizophrenia: understanding disturbed postnatal brain maturation through neuregulin-1-ErbB4 and DISC1. Trends Neurosci. 32, 485–495 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt D. C. (1987). Negative schizophrenic symptomatology and the PCP (phencyclidine) model of schizophrenia. Hillside J. Clin. Psychiatry 9, 12–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G., Neugebauer V. (2012). Modulation of medial prefrontal cortical activity using in vivo recordings and optogenetics. Mol. Brain 5, 36 10.1186/1756-6606-5-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks A. L., McGregor I. S. (1997). Modulation of anxiety-related behaviours following lesions of the prelimbic or infralimbic cortex in the rat. Brain Res. 772, 181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. F., Groenewegen H. J., Witter M. P. (2005). Intrinsic connections of the cingulate cortex in the rat suggest the existence of multiple functionally segregated networks. Neuroscience 133, 193–207 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz J. T., Javitt D. C. (2010). N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor dysfunction or dysregulation: the final common pathway on the road to schizophrenia? Brain Res. Bull. 83, 108–121 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl T., Duffy L., Scimone A., Harvey R. P., Schofield P. R. (2007). Altered motor activity, exploration and anxiety in heterozygous neuregulin 1 mutant mice: implications for understanding schizophrenia. Genes Brain Behav. 6, 677–687 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00298.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassem M. S., Lagopoulos J., Stait-Gardner T., Price W. S., Chohan T. W., Arnold J. C., et al. (2013). Stress-induced grey matter loss determined by MRI is primarily due to loss of dendrites and their synapses. Mol. Neurobiol. 47, 645–661 10.1007/s12035-012-8365-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keri S., Kiss I., Seres I., Kelemen O. (2009). A polymorphism of the neuregulin 1 gene (SNP8NRG243177/rs6994992) affects reactivity to expressed emotion in schizophrenia. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 150B, 418–420 10.1002/ajmg.b.30812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G., Alicata D., Cloak C., Chang L. (2010). Psychiatric symptoms and HPA axis function in adolescent methamphetamine users. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 5, 582–591 10.1007/s11481-010-9206-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornhuber J., Mack-Burkhardt F., Riederer P., Hebenstreit G. F., Reynolds G. P., Andrews H. B., et al. (1989). [3H]MK-801 binding sites in postmortem brain regions of schizophrenic patients. J. Neural Transm. 77, 231–236 10.1007/BF01248936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon D. H., Kim B. S., Chang H., Kim Y. I., Jo S. A., Leem Y. H. (2013). Exercise ameliorates cognition impairment due to restraint stress-induced oxidative insult and reduced BDNF level. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 434, 245–251 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law A. J., Kleinman J. E., Weinberger D. R., Weickert C. S. (2007). Disease-associated intronic variants in the ErbB4 gene are related to altered ErbB4 splice-variant expression in the brain in schizophrenia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 129–141 10.1093/hmg/ddl449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law A. J., Shannon Weickert C., Hyde T. M., Kleinman J. E., Harrison P. J. (2004). Neuregulin-1 (NRG-1) mRNA and protein in the adult human brain. Neuroscience 127, 125–136 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie S. M., McIntosh A. M., Hall J., Owens D. G., Johnstone E. C. (2008). Brain structure and function changes during the development of schizophrenia: the evidence from studies of subjects at increased genetic risk. Schizophr. Bull. 34, 330–340 10.1093/schbul/sbm158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P. R., Brady D., Koenig J. I. (2003). Corticosterone alters N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit mRNA expression before puberty. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 115, 55–62 10.1016/S0169-328X(03)00180-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y., Tejani-Butt S. M. (2010). N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptors are altered by stress and alcohol in Wistar-Kyoto rat brain. Neuroscience 169, 125–131 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leussis M. P., Lawson K., Stone K., Andersen S. L. (2008). The enduring effects of an adolescent social stressor on synaptic density, part II: poststress reversal of synaptic loss in the cortex by adinazolam and MK-801. Synapse 62, 185–192 10.1002/syn.20483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. A., Levitt P. (2002). Schizophrenia as a disorder of neurodevelopment. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 25, 409–432 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Woo R. S., Mei L., Malinow R. (2007). The neuregulin-1 receptor erbB4 controls glutamatergic synapse maturation and plasticity. Neuron 54, 583–597 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieth E., Lanoue K. F., Berkich D. A., Xu B., Ratz M., Taylor C., et al. (2001). Nitrogen shuttling between neurons and glial cells during glutamate synthesis. J. Neurochem. 76, 1712–1723 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00156.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L. E., Chesworth R., Arnold J. C., Karl T. (2010). A follow-up study: acute behavioural effects of Delta(9)-THC in female heterozygous neuregulin 1 transmembrane domain mutant mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 211, 277–289 10.1007/s00213-010-1896-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L. E., Chesworth R., Huang X. F., McGregor I. S., Arnold J. C., Karl T. (2013). Transmembrane domain Nrg1 mutant mice show altered susceptibility to the neurobehavioural actions of repeated THC exposure in adolescence. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16, 163–175 10.1017/S1461145711001854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L. E., Chesworth R., Huang X. F., Wong A., Spiro A., McGregor I. S., et al. (2012). Distinct neurobehavioural effects of cannabidiol in transmembrane domain neuregulin 1 mutant mice. PLoS ONE 7:e34129 10.1371/journal.pone.0034129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magarinos A. M., Li C. J., Gal Toth J., Bath K. G., Jing D., Lee F. S., et al. (2011). Effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor haploinsufficiency on stress-induced remodeling of hippocampal neurons. Hippocampus 21, 253–264 10.1002/hipo.20744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J. W., Johnston M. V. (1990). Physiological and pathophysiological roles of excitatory amino acids during central nervous system development. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 15, 41–70 10.1016/0165-0173(90)90011-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall S. J., Widdop R. E., Lawrence A. J. (2004). Medial prefrontal cortical integration of psychological stress in rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 2430–2440 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03707.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol. Rev. 87, 873–904 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei L., Xiong W. C. (2008). Neuregulin 1 in neural development, synaptic plasticity and schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 437–452 10.1038/nrn2392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelsen K. A., Van Den Hove D. L., Schmitz C., Segers O., Prickaerts J., Steinbusch H. W. (2007). Prenatal stress and subsequent exposure to chronic mild stress influence dendritic spine density and morphology in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. BMC Neurosci. 8:107 10.1186/1471-2202-8-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S. P., Bielby-Clarke K. (2008). Neuregulin signaling in neurons depends on ErbB4 interaction with PSD-95. Brain Res. 1207, 32–35 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.02.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray R. M., Jones P., O'callaghan E. (1991). Fetal brain development and later schizophrenia. Ciba Found. Symp. 156, 155–163 discussion: 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I., Krabbendam L., Delespaul P. A., Van Os J. (2003). Do life events have their effect on psychosis by influencing the emotional reactivity to daily life stress? Psychol. Med. 33, 327–333 10.1017/S0033291702006785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell K. A., Karl T., Huang X. F. (2013). A neuregulin 1 transmembrane domain mutation causes imbalanced glutamatergic and dopaminergic receptor expression in mice. Neuroscience 248, 670–680 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell K. A., Zavitsanou K., Huang X. F. (2005). Ionotropic glutamate receptor binding in the posterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia patients. Neuroreport 16, 1363–1367 10.1097/01.wnr.0000174056.11403.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T., Keshavan M., Giedd J. N. (2008). Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 947–957 10.1038/nrn2513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G. F. K. B. J. (2004). The Mouse Brain in Sterotaxic Coordinates. 2nd Edn San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Elsevier Science USA [Google Scholar]

- Pearce I. A., Cambray-Deakin M. A., Burgoyne R. D. (1987). Glutamate acting on NMDA receptors stimulates neurite outgrowth from cerebellar granule cells. FEBS Lett. 223, 143–147 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80525-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston A. R., Shohamy D., Tamminga C. A., Wagner A. D. (2005). Hippocampal function, declarative memory, and schizophrenia: anatomic and functional neuroimaging considerations. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 5, 249–256 10.1007/s11910-005-0067-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley J. J., Rocher A. B., Miller M., Janssen W. G., Liston C., Hof P. R., et al. (2006). Repeated stress induces dendritic spine loss in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex 16, 313–320 10.1093/cercor/bhi104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley J. J., Rocher A. B., Rodriguez A., Ehlenberger D. B., Dammann M., McEwen B. S., et al. (2008). Repeated stress alters dendritic spine morphology in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 507, 1141–1150 10.1002/cne.21588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley J. J., Sisti H. M., Hao J., Rocher A. B., McCall T., Hof P. R., et al. (2004). Chronic behavioral stress induces apical dendritic reorganization in pyramidal neurons of the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience 125, 1–6 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahdar A., Galvan A. (2014). The cognitive and neurobiological effects of daily stress in adolescents. Neuroimage 92C, 267–273 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reul J. M., Hesketh S. A., Collins A., Mecinas M. G. (2009). Epigenetic mechanisms in the dentate gyrus act as a molecular switch in hippocampus-associated memory formation. Epigenetics 4, 434–439 10.4161/epi.4.7.9806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheetz A. J., Constantine-Paton M. (1994). Modulation of NMDA receptor function: implications for vertebrate neural development. FASEB J. 8, 745–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan T. P., Chambers R. A., Russell D. S. (2004). Regulation of affect by the lateral septum: implications for neuropsychiatry. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 46, 71–117 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sircar R. (2000). Developmental maturation of the N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor channel complex in postnatal rat brain. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 18, 121–131 10.1016/S0736-5748(99)00069-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer J. R., Darbyshire K. M., Boucher A. A., Arnold J. C. (2012). Adolescent neuregulin 1 heterozygous mice display enhanced behavioural sensitivity to methamphetamine. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 39, 376–381 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer J. R., Darbyshire K. M., Boucher A. A., Kashem M. A., Long L. E., McGregor I. S., et al. (2013). Novel molecular changes induced by Nrg1 hypomorphism and Nrg1-cannabinoid interaction in adolescence: a hippocampal proteomic study in mice. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 7:15 10.3389/fncel.2013.00015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani M. R., Moghaddam B. (2005). Transient N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor blockade in early development causes lasting cognitive deficits relevant to schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 57, 433–436 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson H., Sigurdsson E., Steinthorsdottir V., Bjornsdottir S., Sigmundsson T., Ghosh S., et al. (2002). Neuregulin 1 and susceptibility to schizophrenia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 877–892 10.1086/342734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterlemann V., Rammes G., Wolf M., Liebl C., Ganea K., Muller M. B., et al. (2010). Chronic social stress during adolescence induces cognitive impairment in aged mice. Hippocampus 20, 540–549 10.1002/hipo.20655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan R. M., Gratton A. (1999). Lateralized effects of medial prefrontal cortex lesions on neuroendocrine and autonomic stress responses in rats. J. Neurosci. 19, 2834–2840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland J. E., Burian L. C., Covault J., Conti L. H. (2010). The effect of restraint stress on prepulse inhibition and on corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and CRF receptor gene expression in Wistar-Kyoto and Brown Norway rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 97, 227–238 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland J. E., Conti L. H. (2011). Restraint stress-induced reduction in prepulse inhibition in Brown Norway rats: role of the CRF2 receptor. Neuropharmacology 60, 561–571 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. B., Taylor A. R., Koenig J. I. (2012). The interaction of disrupted Type II Neuregulin 1 and chronic adolescent stress on adult anxiety- and fear-related behaviors. Neuroscience 249, 31–42 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.09.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. B., Taylor A. R., Markham J. A., Geurts A. M., Kanaskie B. Z., Koenig J. I. (2010). Disruption of the neuregulin 1 gene in the rat alters HPA axis activity and behavioral responses to environmental stimuli. Physiol. Behav. 104, 205–214 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzanoulinou S., Riccio O., De Boer M. W., Sandi C. (2014). Peripubertal stress-induced behavioral changes are associated with altered expression of genes involved in excitation and inhibition in the amygdala. Transl. Psychiatry 4:e410 10.1038/tp.2014.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen A. P., Creemers H. E., Greaves-Lord K., Verhulst F. C., Ormel J., Huizink A. C. (2011). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reactivity to social stress and adolescent cannabis use: the TRAILS study. Addiction 106, 1484–1492 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03448.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Os J., Kenis G., Rutten B. P. (2010). The environment and schizophrenia. Nature 468, 203–212 10.1038/nature09563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Winkel R., Esquivel G., Kenis G., Wichers M., Collip D., Peerbooms O., et al. (2010). REVIEW: genome-wide findings in schizophrenia and the role of gene-environment interplay. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 16, e185–192 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00155.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Winkel R., Stefanis N. C., Myin-Germeys I. (2008). Psychosocial stress and psychosis. A review of the neurobiological mechanisms and the evidence for gene-stress interaction. Schizophr. Bull. 34, 1095–1105 10.1093/schbul/sbn101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velakoulis D., Pantelis C., McGorry P. D., Dudgeon P., Brewer W., Cook M., et al. (1999). Hippocampal volume in first-episode psychoses and chronic schizophrenia: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 56, 133–141 10.1001/archpsyc.56.2.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viviani B., Bartesaghi S., Gardoni F., Vezzani A., Behrens M. M., Bartfai T., et al. (2003). Interleukin-1beta enhances NMDA receptor-mediated intracellular calcium increase through activation of the Src family of kinases. J. Neurosci. 23, 8692–8700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viviani B., Boraso M., Valero M., Gardoni F., Marco E. M., Llorente R., et al. (2013). Early maternal deprivation immunologically primes hippocampal synapses by redistributing interleukin-1 receptor type I in a sex dependent manner. Brain Behav. Immun. 23, 8692–8700 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viviani B., Gardoni F., Bartesaghi S., Corsini E., Facchi A., Galli C. L., et al. (2006). Interleukin-1 beta released by gp120 drives neural death through tyrosine phosphorylation and trafficking of NMDA receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30212–30222 10.1074/jbc.M602156200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Bohlen Und Halbach O., Zacher C., Gass P., Unsicker K. (2006). Age-related alterations in hippocampal spines and deficiencies in spatial memory in mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 83, 525–531 10.1002/jnr.20759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker E., Bollini A. M. (2002). Pubertal neurodevelopment and the emergence of psychotic symptoms. Schizophr. Res. 54, 17–23 10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00347-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker E., Mittal V., Tessner K. (2008). Stress and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis in the developmental course of schizophrenia. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 4, 189–216 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., McInnis J., Ross-Sanchez M., Shinnick-Gallagher P., Wiley J. L., Johnson K. M. (2001). Long-term behavioral and neurodegenerative effects of perinatal phencyclidine administration: implications for schizophrenia. Neuroscience 107, 535–550 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00384-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger D. R. (1987). Implications of normal brain development for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 44, 660–669 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800190080012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger D. R., Lipska B. K. (1995). Cortical maldevelopment, anti-psychotic drugs, and schizophrenia: a search for common ground. Schizophr. Res. 16, 87–110 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00013-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenthold R. J., Prybylowski K., Standley S., Sans N., Petralia R. S. (2003). Trafficking of NMDA receptors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 43, 335–358 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.135803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley J. L., Buhler K. G., Lavecchia K. L., Johnson K. M. (2003). Pharmacological challenge reveals long-term effects of perinatal phencyclidine on delayed spatial alternation in rats. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 27, 867–873 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00146-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]