Abstract

Bone fractures are a major consequence of osteoporosis. There is a direct relationship between serum estrogen concentrations and osteoporosis risk. Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) greatly decrease serum estrogen levels in postmenopausal women, and increased incidence of fractures is a side effect of AI therapy. We performed a discovery case-cohort genome-wide association study (GWAS) using samples from 1071 patients, 231 cases and 840 controls, enrolled in the MA.27 breast cancer AI trial to identify genetic factors involved in AI-related fractures, followed by functional genomic validation. Association analyses identified 20 GWAS single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) signals with P < 5E-06. After removal of signals in gene deserts and those composed entirely of imputed SNPs, we applied a functional validation “decision cascade” that resulted in validation of the CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E, TRAM2-TMEM14A, and MAP4K4 genes. These genes all displayed estradiol (E2)-dependent induction in human fetal osteoblasts transfected with estrogen receptor-α, and their knockdown altered the expression of known osteoporosis-related genes. These same genes also displayed SNP-dependent variation in E2 induction that paralleled the SNP-dependent induction of known osteoporosis genes, such as osteoprotegerin. In summary, our case-cohort GWAS identified SNPs in or near CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E, TRAM2-TMEM14A, and MAP4K4 that were associated with risk for bone fracture in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients treated with AIs. These genes displayed E2-dependent induction, their knockdown altered the expression of genes related to osteoporosis, and they displayed SNP genotype-dependent variation in E2 induction. These observations may lead to the identification of novel mechanisms associated with fracture risk in postmenopausal women treated with AIs.

Osteoporosis is a common disease that involves reduced bone mineral density (BMD) and increased risk of fractures (1). There is a direct relationship between decreased serum estrogen concentrations and osteoporosis risk (2). Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are a major class of drugs used in the adjuvant endocrine therapy of postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer. AIs inhibit cytochrome P450 CYP19A1 (aromatase), the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of androgens to estrogens (3). AI therapy decreases serum estrogen levels by more than 98% (4) and is associated with bone loss (5). As a result, women receiving adjuvant AI therapy for breast cancer are at increased risk for the occurrence of fractures relative to those treated with tamoxifen (6), which is the alternative endocrine therapy for these women.

Clinical trials designed to determine the efficacy of AIs in the treatment of breast cancer are the major source of information on the incidence of bone fractures during AI therapy (7). For example, the Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination trial compared the AI anastrozole with the selective ER modulator tamoxifen, and significantly more fractures were seen during treatment in the anastrozole group (14.6% vs 11.3%, odds ratio 1.33, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.15–0.155; P < .0001) (8). In the International Breast Cancer Study Group BIG I-98 clinical trial, the incidence of fractures during 5 years of treatment with the AI letrozole was significantly higher than for tamoxifen therapy (9.3% vs 5.8%; P = .0002) (9). A metaanalysis of 7 trials comparing AIs with tamoxifen in the treatment of postmenopausal women with early stage breast cancer reported that treatment with AIs significantly increased risk for bone fractures (odds ratio 1.47, 95% CI 1.34–1.61) (10).

The DNA samples used in our study were obtained from MA.27, a phase III adjuvant trial of 5 years of therapy of postmenopausal patients with ER-positive breast cancer with 2 different AIs, exemestane and anastrozole. MA.27 is the largest trial examining AIs as adjuvant therapy for early stage breast cancer (n = 7576 patients). Of those patients, 72% (n = 5427 patients) contributed DNA for use in genetic studies. The final analysis of MA.27 data showed no differences in efficacy between exemestane and anastrozole. Specifically, at median follow-up of 4.1 year, 4-year event-free survival was 91.0% for exemestane and 91.2% for anastrozole (stratified hazard ratio 1.02, 95% CI 0.87–1.18; P = .85). Overall, distant disease-free survival and disease-specific survival were similar for both drugs. Self-reported osteoporosis was more frequent with anastrozole than exemestane (35% vs 31%; P = .001), but there was no difference between the 2 agents in terms of fragility fractures (14% and 13%, respectively) (11). This very large clinical trial provided a unique opportunity to identify genes associated with bone fracture risk after the striking reduction in serum estrogen levels produced by the treatment of postmenopausal women with AIs.

Specifically, we performed a discovery genome-wide association study (GWAS) in an attempt to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with fragility fractures in women enrolled in the MA.27 trial. We then pursued those signals with a series of functional genomic studies, because we knew that the GWAS would result in the identification of many false positive signals. This strategy is identical to one that we applied, successfully, in a GWAS for an adverse reaction to AI therapy using DNA samples from the MA.27 study. That GWAS identified SNP signals near the TCL1A gene that, in a series of subsequent publications, we showed to be associated with a novel estrogen-dependent, SNP-dependent mechanism for the regulation of cytokine and chemokine expression (12–14).

The present GWAS used a case-cohort design, with 231 cases and 840 controls. Cases were MA.27 patients who experienced a fragility fracture, defined as a fracture occurring in the spine, forearm, humerus, or proximal femur with mild to moderate trauma. Even though our patients were obtained from the largest adjuvant AI trial available, we understood that the study was not optimally powered; so, as mentioned earlier, we established a “cascade” of functional validation tests for the signals identified. To do that, we took advantage of information from previous GWAS for osteoporosis risk, studies that predominately used BMD as a phenotype rather than bone fractures (15). Of equal importance, we used a genome data-rich lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) model system that we have shown repeatedly to be a powerful tool both for generating pharmacogenomic hypotheses (16–18) and for the pursuit of hypotheses identified in the course of clinical GWAS like the present study (19–21). It should be pointed out that pharmacogenomic GWASs present unique challenges, but they also have unique advantages. Specifically, once a large clinical trial like MA.27 (total cost more than $35 million over a 10-y time period) (22) is completed, it is impractical or even unethical to “repeat” it, thus making replication a challenge. However, a great advantage of pharmacogenomic studies is the fact that we understand the drug mechanism of action. In the present case, AIs inhibit estrogen biosynthesis (3). As a result, we are able to take advantage of previous biological and pharmacologic knowledge to use functional validation to pursue signals identified during genome-wide studies, as demonstrated in the present study.

The use of this approach allowed us to identify candidate SNP signals in or near the CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E, TRAM2-TMEM14A, and MAP4K4 genes, all of which displayed SNP-dependent variation in estrogen induction which paralleled that of genes previously identified during osteoporosis risk GWAS, even though the SNPs were in or near CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E, TRAM2-TMEM14A, and MAP4K4. As a result, the present study not only resulted in the identification of potential novel SNP biomarkers for fracture risk in postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with AIs, but it also may contribute to our understanding of mechanisms involved in bone biology in the setting of the striking pharmacologically induced reduction in estrogen levels that occurs in patients with ER-positive breast cancer who are exposed to 5 years of clinically indicated adjuvant AI therapy.

Materials and Methods

Source of patients and description of MA.27

Cases and controls were obtained from the MA.27 trial conducted by the NCIC Clinical Trials Group (coordinating group), Cancer and Leukemia Group B, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), North Central Cancer Treatment Group, Southwest Oncology Group, and the International Breast Cancer Study Group (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00066573). Details of MA.27 have been published previously (11). In brief, MA.27 recruited postmenopausal women with histologically confirmed and completely resected stage I–III breast cancer (AJCC version 6) that was ER and/or progesterone receptor positive. Patients were randomized to 5 years of anastrozole or exemestane. Accrual of 6827 North American patients occurred between May 2003 and July 2008, with most patients providing DNA and consent for genetic testing. Non-North American patients (n = 693) entered by the International Breast Cancer Study Group did not contribute DNA. MA.27 initially included a second randomization to celecoxib (400 mg twice daily) or placebo, but this step was discontinued in December 2004 after the entry of 1622 patients because of reports of cardiovascular adverse events associated with celecoxib. The final results from MA.27, as mentioned previously (11), revealed no difference in efficacy between anastrozole and exemestane. We defined cases as patients who experienced a new fragility fracture at any time while they were on the trial that might be due to AI-related bone effects, specifically those in the spine, forearm, humerus, or proximal femur, from whom DNA was available and consent for genetic testing was given. The cases were selected by a committee (P.E.G., J.N.I., J.-A.W.C., L.E.S., S.K.) that included a specialist in osteoporosis (S.K.).

The case-cohort design was chosen so that future GWAS on different phenotypes would be economical by reusing a randomly chosen subcohort from the main clinical trial. The random subcohort included 876 randomly chosen subjects, of whom 36 had a fracture; all remaining 195 fracture cases were also included in analyses.

Genotypes and quality control

Of the 1071 subjects included in the study, 184 had been genotyped previously for a study of musculoskeletal adverse events (MS-AEs) using Illumina Human610-Quad BeadChips (12), and the remaining 887 subjects for this study were genotyped using Illumina OmniExpress BeadChips. A total of 729 758 SNPs were genotyped with OmniExpress, but 37 489 (5.1%) of the SNPs were considered failures by the laboratory. Of the remaining 692 269 SNPs, 61 081 SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.01 were excluded because of limited power for association analyses. An additional 1394 SNPs were removed based on the Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium exact test in PLINK based on controls only. For 2 pairs of duplicate samples, the percentage of discordant genotypes was less than 1.4E-3%, whereas 1 duplicate had 42% discordant genotypes, suggesting a sample mix-up and was excluded from further analyses. The percentage of Mendelian transmission errors was 4.3E-2%.

Because subjects had been genotyped on 2 different platforms, imputation was used to create a common set of SNPs for all subjects. The 1094 subjects from the “1000 Genome” reference population (11/23/2010 release) were used as reference. The software BEAGLE v3.3.1 was used, with 20-MB regions with 1-MB buffer on each side. Imputed genotypes with a dosage R2 < 0.3 were excluded from analyses. The total number of typed and imputed SNPs for the present fractures genotype study was 7 926 078. A similar process was used to impute SNPs for the previous MS-AE study (12), resulting in a total of 7 458 289 typed and imputed SNPs. After merging the 2 studies, the number of measured and imputed SNPs with MAF > 1% used for analysis was 7 560 631 SNPs.

Statistical analyses

To control for potential population stratification, SNPs were chosen that were uncorrelated with each other to avoid local genomic linkage disequilibrium having undesirable impact on global genomic estimates of population stratification. SNPs were considered uncorrelated when the absolute value of the Pearson correlation was less than 0.063. This resulted in the use of 6476 SNPs to evaluate population structure. Eigenvectors and eigenvalues for the SNP correlations were computed by EIGENSTRAT (23). Eigenvectors corresponding to eigenvalues determined to be statistically different from 0 based on Tracy-Widom test (P < .05) were included as covariates in the analysis (24). This resulted in 5 potential eigenvectors to adjust for substructure and population stratification.

The end point for GWAS analyses was time from randomization to fracture, allowing for censored times. The Cox regression model (coxph in R software) with weights and robust variance estimates was used for the case-cohort design, as described by Therneau and Li (25). The next covariates were evaluated for their association with time to fracture: treatment (exemestane vs anastrazole), previous chemotherapy (yes vs no), age (<65 vs 65+ y), ECOG performance status (0, 1, and 2), previous surgery (mastectomy vs partial mastectomy), study (MS-AE vs current study), previous fractures (yes vs no), use of raloxifene (yes vs no), use of bisphosphonate (yes vs no), BMI (quantile cutpoints of 24.8, 28.4, and 32.2), TNM (tumor, nodes, metastases) stage (I, II, and III), and the first 5 eigenvectors (chosen because each had Tracy-Widom P < .05). After backward selection of covariates (P < .05), the following remaining covariates were used in the GWAS adjusted analyses: age, previous fractures, bisphosphonate use, and the first 3 eigenvectors.

Patient characteristics

From the initial sample of 1115 subjects, 44 were removed for the following reasons: failed genotyping (5), sample mix-up (2), cancer recurrence before fracture (11), unknown date of fracture (25), and no follow-up after randomization (1). Among the 1071 subjects included in the analyses, 231 had a fracture and 840 were free of fracture.

Cell lines

We used the Coriell Institute Human Variation Panel of LCLs obtained from 100 European-American (EA), 100 African-American (AA), and 100 Han Chinese-American healthy subjects to perform many of the functional genomic studies. These cell lines were generated from blood samples obtained by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, followed by deposit in the Coriell Institute. We had previously genotyped DNA from these cell lines for genome-wide SNPs using Illumina 550K and 510S SNP BeadChips (Illumina). The Coriell Institute genotyped DNA from the same cell lines using the Affymetrix SNP Array 6.0 (Affymetrix), for a total of approximately 1.3 million unique genotyped SNPs per cell line (17). In addition, 1000 Genome data were used to impute approximately 7 million SNPs per cell line. We also generated basal Affymetrix U133 2.0 Plus GeneChip expression array data for all of the cell lines. This genomic data-rich LCL genomic model system has been described in detail elsewhere (17). The microarray and SNP data for these LCLs have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ under SuerSeries [GEO:GSE24277].

The human fetal osteoblast (hFOB)-ERα cell line was generated by stably transfecting hFOB cells with ERα constructs in the laboratory of Thomas Spelsberg, PhD, at the Mayo Clinic (Dr Spelsberg generously provided these cells for use in our studies). John Hawse, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic, provided consultative advice with regard to the hFOB-ERα cell line (26).

Estradiol (E2) induction

Subconfluent cultures of hFOB-ERα cells were incubated in serum-free medium (DMEM) for 24 hours, followed by DMEM with 5% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (FBS) for another 48 hours. Before exposure to E2, cells were grown in DMEM without serum for 24 hours, followed by 0.1 nmol/L E2 for 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 40, and 48 hours. Total RNA was then isolated from the cells with the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN). Two hundred nanograms of total RNA were used to perform quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) with primers for TH1L, CTSZ, ATP5E, SLMO2, TRAM2, TMEM14A, and MAP4K4 (QIAGEN) as well as primers for β-actin (QIAGEN) as a control. All gene expression data was “normalized” on the basis of β-actin expression in the hFOB-ERα cells.

LCL culture

Three LCLs from EA subjects homozygous for variant genotypes as well as 3 homozygous for wild type (WT) sequences for the CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E rs10485828 SNP, 3 LCLs from EA subjects homozygous for variant genotypes as well as 3 homozygous for WT sequences for the TRAM2-TMEM14A rs6901146 SNP, and 3 LCLs from AA subjects homozygous for variant as well as 3 homozygous for WT sequences for the MAP4K4 rs4550690 SNP were selected for SNP-dependent induction analyses. These LCLs were cultured in RPMI 1640 media containing 15% (vol/vol) FBS. Before E2 treatment, 5E-06 cells for each cell line were cultured for 24 hours in RPMI 1640 containing 5% (vol/vol) charcoal-stripped FBS (Invitrogen), followed by culture in the same medium without FBS for an additional 24 hours. All cells were then cultured for 24 hours in 12-well plates with RPMI 1640 medium that contained 0nM, 0.01nM, 0.1nM, 1nM, and 10nM E2. Total RNA was isolated from the cells with the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN). Two hundred nanograms of total RNA were then used to perform qRT-PCR with CTSZ, SLMO2, ATP5E, TH1L, TRAM2, TMEM14A, MAP4K4, osteoprotegerin (OPG), RANK, and RANKL primers (QIAGEN). All gene expression levels were normalized on the basis of ERα expression in each of the cell lines studied.

Gene knockdown

To perform knockdown studies, hFOB-ERα cells were transfected with CTSZ, SLMO2, ATP5E, TH1L, TRAM2, TMEM14A, and MAP4K4 small interfering RNA smart pools and negative small interfering RNA (Dharmacon) using lipofectamin 2000 (Invitrogen) for 48 hours. Total RNA was isolated from the hFOB-ERα-transfected cells using the Quick RNA miniprep kit (Zymo Research), and 200 ng of that RNA were used to perform qRT-PCR with primers for all 91 genes on the “vitamin D receptor in regulation of genes involved in osteoporosis” panel (Bio-Rad).

Results

MA.27 bone fracture GWAS

The final GWAS involved 231 cases with fragility fractures and 840 controls. The characteristics of these patients are listed in Table 1. GWAS genotyping was performed using the Illumina Omni Express for 887 patients (83%). As described in Materials and Methods, GWAS genotyping for 184 of the patients (17%) (12) had been performed previously with the Human610 Quad Beadchip. Even though we used samples from the largest adjuvant AI clinical trial available, we assumed that many of the “signals” observed during the GWAS would be false positives, so we planned from the beginning to apply a series of predetermined functional genomic criteria that narrowed our initial list of “SNP signals” to a final group of signals that met the criteria of a functional genomic “decision cascade” that we established, thus opening the way for future exploration of the possible role of these genes in bone biology and in the pathophysiology of osteoporosis.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Cases (n = 231) | Controls (n = 840) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 68.7 | 64.2 |

| Range | 46.1-89.8 | 35.9-88.9 |

| Body mass index | ||

| Number with data | 227 | 836 |

| Median | 28.6 | 28.4 |

| Quartile 1, quartile 4 | 24.8, 32.4 | 24.9, 32.2 |

| Range | 17.4-66.8 | 16.5-61.3 |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 2 (0.9%) | 12 (1.4%) |

| Black | 5 (2.2%) | 22 (2.6%) |

| Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.4%) |

| White | 224 (97.0%) | 802 (95.5%) |

| Previous fracture | ||

| No | 186 (80.5%) | 758 (90.2%) |

| Yes | 45 (19.5%) | 82 (9.8%) |

| Previous chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 57 (24.7%) | 255 (30.4%) |

| No | 174 (75.3%) | 585 (69.6%) |

| Surgery | ||

| Mastectomy | 75 (32.5%) | 274 (32.6%) |

| Partial mastectomy | 156 (67.5%) | 566 (67.4%) |

| Treatment | ||

| Exemestane | 116 (50.2%) | 420 (50.0%) |

| Anastrozole | 115 (49.8%) | 420 (50.0%) |

| ECOG performance score | ||

| 0 | 178 (77.1%) | 699 (83.2%) |

| 1 | 51 (22.1%) | 132 (15.7%) |

| 2 | 2 (0.9%) | 9 (1.1%) |

| TNM stage | ||

| I | 126 (54.5%) | 502 (59.8%) |

| II | 81 (35.1%) | 270 (32.1%) |

| III | 19 (8.2%) | 51 (6.1%) |

| T1-3NXM0 | 5 (2.2%) | 13 (1.5%) |

| TXN0M0 | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (0.5%) |

| Previous raloxifene | ||

| Ever | 4 (1.7%) | 14 (1.7%) |

| Never | 227 (98.3%) | 819 (97.5%) |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 7 (0.8%) |

| Bisphosphonate use | ||

| Ever | 122 (52.8%) | 270 (32.1%) |

| Never | 94 (40.7%) | 507 (60.4%) |

| Missing | 15 (6.5%) | 63 (7.5%) |

Functional genomic studies

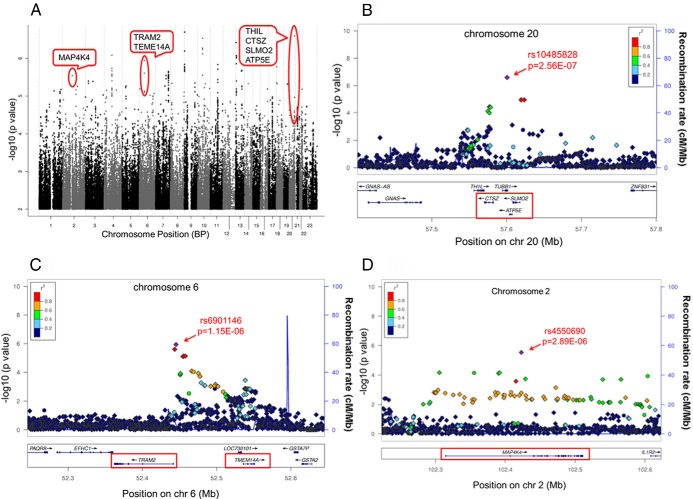

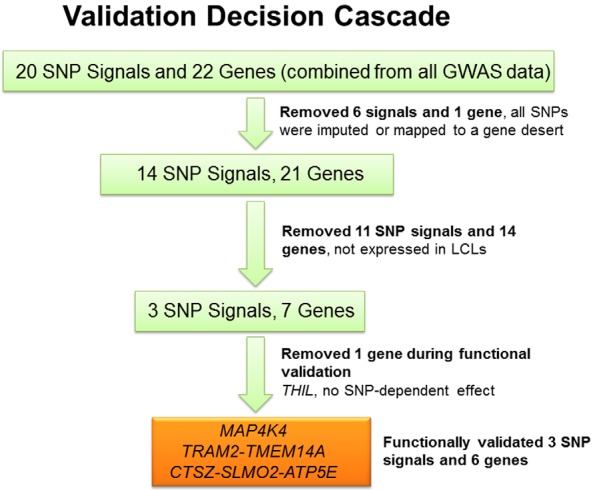

As a first step in the functional validation process for GWAS signals, we selected the “top” SNP signals from the Manhattan plot shown in Figure 1A. The quantile-quantile plot for these data is shown in Supplemental Figure 1. In Figure 1A, we have highlighted the SNP signals and associated genes that passed through the decision cascade successfully. There were a total of 20 signals with P < 5E-06 and 22 genes that mapped in or near those signals (Table 2). If the SNP signal was over a gene cluster, we listed all of the genes in that cluster in Table 2, eg, CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E-TH1L for the chromosome 20 SNP signal. Figure 1, B–D, shows LocusZoom plots for the 3 SNP signals and related genes that subsequently were validated functionally. None of the original 20 SNP signals met the generally accepted value for genome-wide significance of 5.0E-08, which was not surprising because of the relatively small number of “cases” in the trial, even though MA.27 represented the largest adjuvant AI trial available. It should be emphasized that we have previously pursued GWAS SNP signals that were not genome-wide significant to successfully demonstrate the biological importance of those signals (12, 21) but always with the understanding that many of these signals may represent false positives. Based on that experience, we developed a series of criteria for functional pursuit of the signals observed in the present study (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

A, GWAS Manhattan plot GWAS performed with P values adjusted for age, previous fracture, bisphosphonate use, and the first 3 eigenvectors. The 3 SNP signals that underwent functional genomic validation are highlighted. B, LocusZoom plot of the chromosome 20 region surrounding the THIL-TUBB1-CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E genes showing a plot of −log10 (P values) for observed (circles) and imputed SNPs (diamonds). C, LocusZoom plot of the chromosome 6 region surrounding the TRAM2-TMEM14A genes. D, LocusZoom plot of the chromosome 2 region surrounding the MAP4K4 gene.

Table 2.

GWAS Signals and Related Genes from the MA.27 GWAS

| Top SNPs in Signals | Chr | P Values | Genes | Validation Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. rs10967942 | Chr 9 | 2.01E-07 | KCNV2 | Not expressed in LCLs | |

| 2. rs10485828 | Chr 20 | 2.56E-07 | TH1L, TUBB1, | CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E final validated genes, | |

| CTSZ, SLMO2, | TUBB1 not expressed in LCLs, | ||||

| ATP5E | TH1L failed functional validation | ||||

| 3. rs12248467 | Chr 10 | 2.93E-07 | PRKG1 | Not expressed in LCLs | |

| 4. rs76996285 | Chr 13 | 3.81E-07 | PABPC3 | All SNPs were imputed | |

| 5. rs8092654 | Chr 18 | 4.41E-07 | DLGAP1 | Not expressed in LCLs | |

| 6. rs6842571 | Chr 4 | 8.32E-07 | ANTXR2, PRDM8 | Not expressed in LCLs | |

| 7. rs66520040 | Chr 13 | 8.52E-07 | FLT3 | Not expressed in LCLs | |

| 8. rs6901146 | Chr 6 | 1.15E-06 | TRAM2, TMEM14A | TRAM2-TMEM14A final validated genes | |

| 9. rs6591876 | Chr 11 | 1.47E-06 | Gene desert | ||

| 10. rs112830684 | Chr 3 | 1.57E-06 | ASB14, DNAH12 | Not expressed in LCLs | |

| 11. rs7999876 | Chr 13 | 2.10E-06 | Gene desert | ||

| 12. c13.82322180.B37P0 | Chr 13 | 2.19E-06 | Gene desert | ||

| 13. rs73728712 | Chr 7 | 2.25E-06 | DGKI | Not expressed in LCLs | |

| 14. rs61399156 | Chr 7 | 2.87E-06 | DOCK4 | Not expressed in LCLs | |

| 15. rs4550690 | Chr 2 | 2.89E-06 | MAP4K4 | MAP4K4 final validated gene | |

| 16. rs35112095 | Chr 21 | 4.02E-06 | SLC37A1 | Not expressed in LCLs | |

| 17. rs9878448 | Chr 3 | 4.02E-06 | GADL1 | Not expressed in LCLs | |

| 18. rs17015762 | Chr 3 | 4.11E-06 | Gene desert | ||

| 19. rs73511817 | Chr 9 | 4.54E-06 | Gene desert | ||

| 20. rs117996576 | Chr 8 | 4.64E-06 | TUSC3 | Not expressed in LCLs | |

Abbreviation: Chr, chromosome. The table lists the 20 candidate SNP signals selected from our discovery GWAS analyses for pursuit using the Validation Decision Cascade depicted graphically in Figure 2. For each signal, the top SNP is listed, the chromosomal location of the signal, the P value for the top SNP, genes in or near the signal, and the outcome of functional testing, as described in detail in the text. The 3 signals and 6 genes that were validated functionally have been boxed in red.

Figure 2.

Validation decision cascade used to test GWAS signals. The association analysis shown graphically in the Manhattan plot in Figure 1A resulted in the identification of 20 SNP signals with P < 5E-06. The figure depicts graphically the process for SNP signal and associated gene functional validation.

Several of the steps in the validation cascade depicted graphically in Figure 2 were based on our practical ability to experimentally test genes identified during the GWAS using cell line systems, especially our genomic data-rich LCL model system that has repeatedly demonstrated its power both to generate and test pharmacogenomic hypotheses (16–21). One of the major advantages of the LCL system is the ability that it gives us to test common SNP genotypes, because each cell line has been genotyped for approximately 1.3 million SNPs, with a final total of 7 million SNPs after imputation. This LCL system also makes it possible to correlate expression among candidate genes and genes known to play a role in disease pathophysiology or drug response. However, the LCL system, despite its repeated success, also has limitations, including the fact that these are not osteoblastic cells. Therefore, we also used additional cell line systems, eg, hFOB cells (osteoblasts), in our studies. Finally, we were also able to take into account the possible relationship of genes identified in our GWAS to genes identified during previous osteoporosis GWAS performed using postmenopausal women who had not been exposed to AIs.

As diagrammed graphically in Figure 2, if a signal was composed entirely of imputed SNPs or if it mapped to a gene desert (no annotated genes within ±100 kb), we did not pursue it, reducing the number of signals from 20 to 14 and the number of genes to 21 (Figure 2). We next removed 11 SNP signals and 14 genes from consideration that were not expressed in our LCL model system, making it impossible to take advantage of the power of this cell line system to perform functional genomic studies, leaving 3 SNP signals and 7 genes. The 7 remaining genes were then subjected to a series of functional genomic tests, resulting in a final group of 3 SNP signals and 6 genes that were identified during the GWAS and that also successfully passed through the validation cascade (Table 2). All 6 of those genes were induced by E2 (ie, they were linked to the drug action), their expression paralleled the expression of known osteoporosis related genes (ie, they were linked to the known biology of osteoporosis), and their E2 induction occurred in a SNP genotype-dependent fashion, thus linking them to the GWAS SNP signals that originally resulted in their identification. Subsequent paragraphs will describe each these steps in detail.

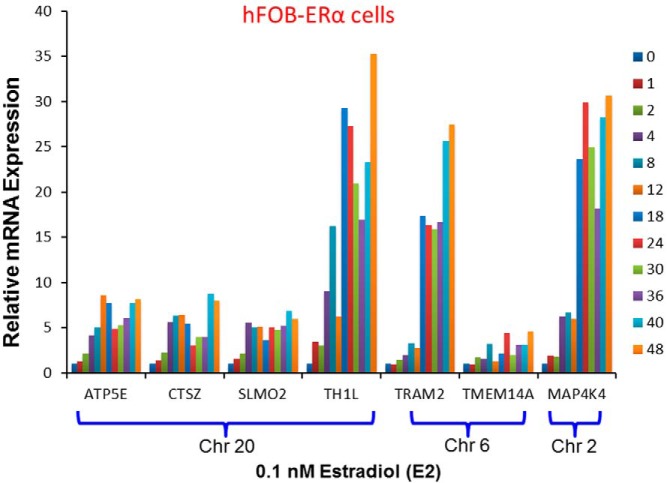

Genes that displayed estrogen-dependent induction

The patients enrolled in MA.27 had been treated with AIs to block estrogen synthesis. Therefore, as a first step in our functional pharmacogenomic studies, we took advantage of the known drug effect to determine whether mRNA expression for TH1L-CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E, TRAM2-TEME14A, or MAP4K4 might be E2 dependent, thus linking the candidate genes identified during the GWAS to the drug effect. These experiments involved exposing hFOB cells stably transfected with ERα (hFOB-ERα) to 0.1 nmol/L E2 for varying times. We observed a greater than 8-fold increase in ATP5E (ATP synthase, H+ transporting mitochondrial F1 complex, Epsilon Subunit) expression, an 8-fold increase in cathepsin Z (CTSZ) expression, a 7-fold increase in Slowmo Homolog 2 (Drosophila) (SLMO2) mRNA expression, a 35-fold increase in Trihydrophobin 1 (TH1L) mRNA expression, a 27-fold increase in Translational associated membrane protein 2 (TRAM2) mRNA expression, a 5-fold increase in transmembrane protein 14A (TMEM14A) mRNA expression, and a 31-fold increase in MAPK kinase kinase kinase 4 (MAP4K4) mRNA expression after 48 hours of incubation with 0.1nM E2 (Figure 3). The results shown in Figure 3 demonstrated that the expression of these 7 genes, ATP5E, CTSZ, SLMO2, TH1L, TRAM2, TMEM14A, and MAP4K4 in hFOB-ERα cells was estrogen dependent, so all of these genes were moved to the next step in the functional validation process. By using the TRANSFAC-AliBaba 2.1 and ENCODE databases, we were unable to identify any estrogen response elements that were disrupted or created by the top SNPs in these 3 SNP signals (see Supplemental Table 1). The mechanism(s) responsible for the E2-dependent induction of the expression of these 7 genes remains unclear.

Figure 3.

E2 induction time course for THIL, CTSZ, SLMO2, ATP5E, TRAM2, TEME14A, and MAP4K4 mRNA expression in hFOB-ERα cells exposed to 0.1 nmol/L E2 for differing periods of time. The values shown represent means of duplicate assays.

Correlation of expression with that of osteoporosis panel genes

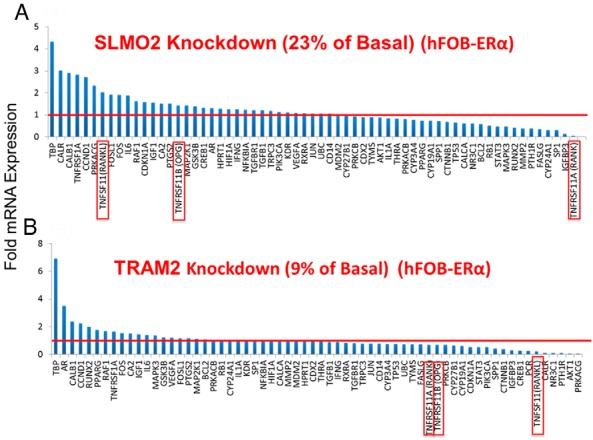

Receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (RANK)-RANK ligand (RANKL)-OPG and the Wnt pathways are all known to play important roles in the pathophysiology of osteoporosis (27), so we used a Bio-Rad Osteoporosis Genes Primer Panel as the next screening test. This panel had been constructed to allow rapid testing of the expression of a group of genes known to play a role in bone biology. For example, when the expression of SLMO2, one of our candidate genes, was knocked down to 23% of its basal level in hFOB-ERα cells, the expression of several osteoporosis-related genes in the panel, but especially that of RANK, displayed a decrease in expression to less than 50% of the basal level, whereas others, including RANKL, increased (Figure 4A). When the expression of TRAM2, another of our candidate genes, was knocked down to 9% of its basal level in the same cells, the expression of RANKL decreased more than 5-fold (Figure 4B). Patterns of expression after the knockdown of the remaining candidate genes in hFOB-ERα cells are shown in Supplemental Figure 2. These results led us to move on to the LCL model system to determine whether there might be a correlation between levels of expression of our 7 GWAS candidate genes with genes that had been identified in the course of previous osteoporosis GWAS performed with postmenopausal women, a setting lacking the striking pharmacological provocation represented by prolonged AI therapy.

Figure 4.

Effect of knockdown of SLMO2 (A) and TRAM2 (B) on the relative mRNA expression of genes involved in the osteoporosis genes primer panel in hFOB-ERα cells. Red lines represent basal control levels of expression. Data for the RANK-RANKL-OPG genes are highlighted with red rectangles.

Genes with expression that correlated with that of osteoporosis-related genes in the Human Variation Panel LCL model system

As the next step in functional validation, we asked whether the expression of genes identified during previous osteoporosis risk GWAS performed using samples from postmenopausal women who had not been exposed to AI therapy (28) might be correlated with variation in the expression of the 7 candidate genes from our AI-associated fracture GWAS, ie, CTSZ, SLMO2, ATP5E, TH1L, TMEME14A, TRAM2, and MAP4K4. To test that possibility, we used baseline mRNA expression data for 54000 Affymetrix gene expression probes for all 300 of the LCLs in the Human Variation Panel. Those data made it possible to determine whether any of the 7 genes identified during our GWAS might have expression that was correlated with the expression of genes identified during previous osteoporosis GWAS (15), with the clear understanding that LCLs are obviously neither osteoblasts nor osteoclasts. By using a cut-off P < 5E-06, all 7 of the remaining MA.27 GWAS genes displayed significant correlations with the expression of genes previously reported to be related to osteoporosis risk (see Table 3). Furthermore, variation in the expression of the many of these genes was highly correlated with that of the RANK-RANKL-OPG genes. In addition, the expression of genes within or near the chromosome 20 SNP signal (CTSZ, SLMO2, and ATP5E) as well as 2 genes near the chromosome 6 SNP signal (TEME14A and TRAM2) were also correlated (Table 4). It of interest that 2 of our final SNP signals involved gene clusters. It is possible that a single SNP signal can be associated with the expression of several genes in such a gene “cluster.” For example, the LCL model system data indicated that ATP5E expression was highly correlated with the expression of 2 other genes, SLMO2 and CTSZ, in the same cluster (Table 4 and Figure 1B). In a similar fashion, TRAM2 expression was highly correlated with the expression of TMEM14A. Both of these genes mapped near the chromosome 6 SNP signal (Table 4 and Figure 1C). As the next step in our analysis, we took advantage of the genome-wide SNP genotype data that we had generated for these 300 LCLs to determine whether different SNP genotypes might be related to variation in expression of the candidate genes during E2 exposure.

Table 3.

Correlation Between the Expression of MA.27 GWAS Candidate Genes and Previously Reported Osteoporosis Risk GWAS Genes in the Human Variation Panel LCL Model System

| Genes | Genes | Spearman ρ | P Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| MA.27 GWAS | Osteoporosis GWAS | ||

| CTSZ | TNFRSF11A (RANK) | −0.3462 | 1.7E-09 |

| CTSZ | SPTBN1 | −0.3341 | 6.6E-09 |

| CTSZ | WNT10B | 0.3079 | 1.0E-07 |

| SLMO2 | FUBP3 | 0.4043 | 1.0E-12 |

| SLMO2 | SPTBN1 | −0.3369 | 4.8E-09 |

| TH1L | C17orf53 | 0.3104 | 7.9E-08 |

| TH1L | TNFRSF11A (RANK) | −0.3179 | 3.7E-08 |

| ATP5E | SPTBN1 | −0.3620 | 3.0E-10 |

| TMEM14A | TNFRSF11A (RANK) | 0.3697 | 1.0E-10 |

| TMEM14A | SLC25A13 | 0.3004 | 2.1E-07 |

| TRAM2 | SPTBN1 | 0.2803 | 1.4E-06 |

| TRAM2 | C18orf192 | −0.2887 | 6.5E-07 |

| TRAM2 | TNFRSF11A (RANK) | −0.3357 | 5.5E-09 |

| TRAM2 | TNFRSF11B (OPG) | −0.2645 | 5.6E-06 |

| TRAM2 | SLC25A131 | −0.3324 | 7.9E-09 |

| MAP4K4 | CTNNB1 | 0.2643 | 5.7E-06 |

| MAP4K4 | WNT6 | 0.3407 | 3.1E-09 |

We have highlighted in red RANK, OPG and SPTBN1, genes with expression that correlated with that of several of our candidate genes.

Table 4.

Correlations Among the Expression of the 7 MA.27 GWAS Candidate Genes in the Human Variation Panel LCL Model System

| Genes MA.27 GWAS | Genes MA.27 GWAS | Spearman ρ | Prob> ρ |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP5E | SLMO2 | 0.3665 | 1.00E-10 |

| ATP5E | CTSZ | 0.4431 | 3.00E-15 |

| SLMO2 | CTSZ | −0.1883 | 1.30E-03 |

| TMEM14A | TRAM2 | −0.2553 | 1.20E-05 |

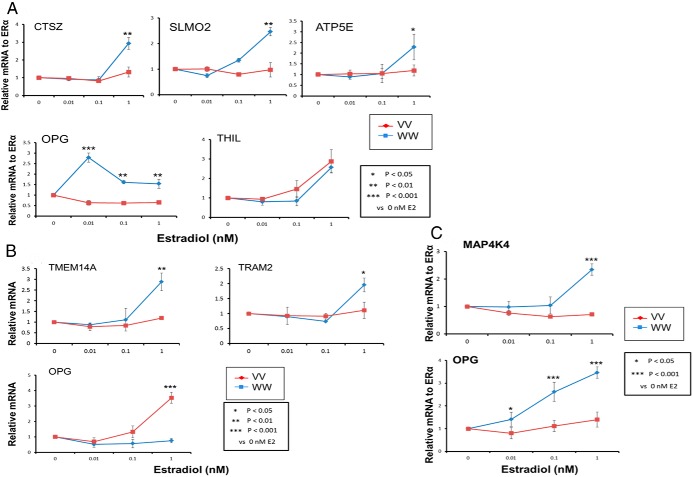

Genes with SNP- and E2-dependent expression correlated with that of osteoporosis-related genes

We next performed an important test of the possible relationship of GWAS SNPs in or near the 7 remaining candidate genes, CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E-TH1L, TRAM2-TMEM14A, and MAP4K4. Specifically, we exposed LCLs from 3 EA subjects who were homozygous for WT SNP genotypes and 3 LCLs that were homozygous for variant genotypes in the signals from the CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E-TH1L gene cluster (see Figure 1B) to increasing concentrations of E2 for 24 hours. We also exposed LCLs from 3 EA subjects who were homozygous for WT SNP genotypes and 3 who were homozygous for variant SNP genotypes for the TRAM2-TMEM14A signal to increasing concentrations of E2 for 24 hours. For the MAP4K4 SNPs, we exposed LCLs from 3 AA subjects who were homozygous for WT SNP genotypes and 3 AA subjects who were homozygous for variant genotypes to increasing concentration of E2 for 24 hours. We used cell lines from AA subjects for the MAP4K4 experiments because of the higher MAF for these SNPs in AA subjects. The purpose of these experiments was to determine whether differences in SNP genotypes might result in differential E2-dependent induction of expression of the candidate genes and, in parallel, the expression of genes known to be related to osteoporosis.

Cell lines homozygous for WT SNP genotypes showed significantly greater E2 dose-dependent induction of CTSZ, SLMO2, and ATP5E expression after exposure to increasing concentrations of E2 than did LCLs homozygous for variant genotypes after exposure to E2 for 24 hours (Figures 5A). However, that was not the case for TH1L. Of importance, the OPG gene also showed greater induction in cell lines that carried the WT genotypes for the CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E gene cluster than did those homozygous for variant SNP genotypes. We included OPG in these experiments because of its important role in bone physiology (29). We should emphasize that the SNPs being studied were in or near the CTSZ, SLMO2, and ATP5E genes. They were not in the OPG gene, which is on a different chromosome, chromosome 8, but these SNP genotypes were associated with differential E2-dependent induction of OPG. Because it failed to display SNP-dependent estrogen induction, we removed TH1L from our list of candidate genes. In a similar fashion, cell lines homozygous for WT genotypes showed significantly greater E2 dose-dependent induction of TMEM14A-TRAM2 expression after exposure to increasing concentrations of E2 than did LCLs homozygous for variant genotypes after 24 hours of E2 exposure (Figure 5B). In this case, the OPG gene showed greater induction in cell lines that carried the variant genotypes for TMEM14A-TRAM2 than did those homozygous for WT SNP genotypes. Finally, cell lines homozygous for WT genotypes for the MAP4K4 SNPs also showed significantly greater E2 dose-dependent induction of MAP4K4 and, in parallel, greater OPG expression after exposure to increasing concentrations of E2 than did LCLs homozygous for variant genotypes after 24 hours (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

LCL SNP-dependent variation of candidate gene expression in response to increasing concentrations of E2 for 3 homozygous W/W (blue lines) and 3 homozygous V/V (pink lines) LCLs. A, Relative CTSZ, SLMO2, and ATP5E mRNA expression (upper panels) and relative mRNA expression for OPG and THIL (lower panels). B, SNP-dependent variation in TMEM14A-TRAM2 expression in response to increasing concentrations of E2 for 3 homozygous W/W (blue lines) and 3 homozygous V/V (pink lines) LCLs (upper panels) and relative mRNA expression level for OPG (lower left panel). C, SNP-dependent variation in MAP4K4 expression in response to increasing concentrations of E2 for 3 homozygous W/W (blue lines) and 3 homozygous V/V (pink lines) AA LCLs (upper panel) and relative mRNA expression level for OPG (lower panel). *, P < .05 and **, P < .01 when compared with the alternative genotype at the same concentration of E2.

Discussion

Osteoporosis and bone fractures associated with osteoporosis represent a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide (30). There is a direct relationship between serum estrogen concentrations and risk for osteoporosis (2). AI therapy decreases estrogen levels in postmenopausal women by more than 98% (31). As a result, the occurrence of bone fracture represents a significant side effect of the use of AIs to treat ER-positive breast cancer patients (10). In the present study, we took advantage of a unique opportunity presented by DNA samples from patients enrolled in MA.27, the largest adjuvant AI breast cancer trial available, to perform a case-cohort discovery GWAS to identify possible biomarkers for AI treatment-associated bone fractures and then to validate those signals functionally. Specifically, we preselected a series of criteria designed to make it practically possible to focus our attention on potential true positive GWAS signals, with the understanding that taking this approach meant that we might miss meaningful signals. We started with a total of 20 SNP signals. After moving through the validation criteria shown graphically in Figure 2, we identified 3 SNP signals and 6 genes that met all of the criteria listed in the figure. Each of those genes, CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E, TRAM2-TMEM14A, and MAP4K4, displayed E2-dependent induction of mRNA expression (Figure 3), and when we knocked down their mRNA, expression of genes in pathways associated with osteoporosis risk and/or bone biology was altered (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure 2). Furthermore, the expression of these 6 genes was correlated with the expression of genes identified during previous osteoporosis GWAS (Tables 3 and 4). Finally, and most important, the E2 induction of these 6 genes was SNP dependent and paralleled the E2-dependent induction of the osteoporosis-related gene encoding OPG, even though the SNPs were in or near the genes identified during our AI fracture GWAS (Figure 5). The approach applied here is similar to a strategy that we applied previously, in which we used a GWAS to identify genes and SNPs associated with severe musculoskeletal pain during AI therapy to identify a SNP signal near the TCL1A gene that led to the identification of a novel estrogen-dependent and SNP-dependent mechanism for the regulation of cytokine and chemokine expression (12–14).

Specifically, we began by linking the candidate genes identified during the GWAS to the effect of AI treatment by studying possible estrogen effect on the mRNA expression of the genes (Figure 3). We then determined a possible relationship of the expression of the candidate genes to the expression of genes known to be involved in bone physiology or osteoporosis biology (Figure 4 and Table), thus linking the genes to the clinical phenotype, bone fracture. Finally, we linked the SNP genotypes in the GWAS signals to the SNP-dependent, estrogen-dependent induction of expression of the candidate genes and, in parallel, of the osteoporosis-related gene OPG, presumably “downstream” of the induction of our candidate genes (Figure 5).

It was encouraging that one of the genes identified during our GWAS, CTSZ, cathepsin Z, a member of cysteine proteinase family, had already been associated with bone remodeling in osteoclasts (32–37), although the mechanism is not well understood. At present, mechanisms for the possible relationship of the remaining genes, SLMO2, ATP5E, TMEM14A, TRAM2, and MAP4K4, to AI-dependent bone fracture risk remain unclear. However, TRAM2 is a known target for Runt-related transcription factor 2, the “master” osteoblast differentiation transcription factor for bone morphogenetic protein signaling in the control of the α1(I) collagen promoter, leading to low bone mass and spontaneous bone fractures when Runt-related transcription factor 2 is overexpressed (38). MAP4K4 positively regulates TNFα and nuclear factor κB signaling pathways, both of which play important roles in osteoporosis (39, 40). We should point out that none of the genes that we observed and functionally validated have been identified during previous osteoporosis risk GWAS. We should also emphasize that bone fracture during 5 years of AI therapy represents a phenotype that differs from postmenopausal osteoporosis, because AI treatment decreases circulating estrogen concentrations in these postmenopausal women to levels that are significantly lower than those observed in the absence of drug therapy (4). In addition, most osteoporosis risk GWASs have used BMD as a phenotype, with only a few using fracture risk as a phenotype (20).

In summary, our case-cohort discovery GWAS has identified SNPs in or close to CTSZ-SLMO2-ATP5E, TMEM14A-TRAM2, and MAP4K4 that were associated with risk for bone fracture in postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with AIs for 5 years. The effect of these SNPs may be related to SNP-dependent, estrogen-dependent regulation of the expression of these genes and the possible downstream regulation of the expression of RANK-RANKL-OPG and other genes related to osteoporosis. Our results may not only provide information with regard to the pathophysiology of and biomarkers for AI treatment-associated bone fractures in postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with AIs, but they may also, based on the results of appropriate follow-up studies, provide insight into novel biological mechanisms related to estrogen effect in bone biology and pathophysiology.

Acknowledgments

We thank the contributions of the women who participated in MA.27 and provided DNA and consent for its use in genetic studies.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants U19 GM61388 (The Pharmacogenomics Research Network), U01 HG005137, R01 CA138461, R01 CA133049, and P50 CA166201 (Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence); a Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America Foundation Center of Excellence in Clinical Pharmacology award; the Mayo Center for Individualized Medicine; and the Rikagaku Kenkyūsho Center for Integrative Medical Science and the Biobank Japan Project funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, and Technology, Japan. P.E.G. is supported in part by the Avon Foundation, New York; ClinicalTrials.gov study NCT00283608.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AA

- African-American

- AI

- aromatase inhibitor

- ATP5E

- ATP synthase, H+ transporting mitochondrial F1 complex, Epsilon Subunit

- BMD

- bone mineral density

- CI

- confidence interval

- CTSZ

- cathepsin Z

- E2

- estradiol

- EA

- European-American

- ECOG

- Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- GWAS

- genome-wide association study

- hFOB

- human fetal osteoblast

- LCL

- lymphoblastoid cell line

- MAF

- minor allele frequency

- MAP4K4

- MAPK kinase kinase kinase 4

- MS-AE

- musculoskeletal adverse event

- OPG

- osteoprotegerin

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- RANK

- receptor activator of nuclear factor κB

- RANKL

- RANK ligand

- SLMO2

- Slowmo Homolog 2 (Drosophila)

- SNP

- single nucleotide polymorphism

- TH1L

- Trihydrophobin 1

- TMEM14A

- transmembrane protein 14A

- TRAM2

- Translational associated membrane protein 2

- WT

- wild type.

References

- 1. Lewiecki EM, Binkley N. Evidence-based medicine, clinical practice guidelines, and common sense in the management of osteoporosis. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:573–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mendoza N, Quereda F, Presa J, et al. Estrogen-related genes and postmenopausal osteoporosis risk. Climacteric. 2012;15:587–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grimm SW, Dyroff MC. Inhibition of human drug metabolizing cytochromes P450 by anastrozole, a potent and selective inhibitor of aromatase. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:598–602 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brueggemeier RW. Aromatase, aromatase inhibitors, and breast cancer. Am J Ther. 2001;8:333–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Confavreux CB, Fontana A, Guastalla JP, Munoz F, Brun J, Delmas PD. Estrogen-dependent increase in bone turnover and bone loss in postmenopausal women with breast cancer treated with anastrozole. Prevention with bisphosphonates. Bone. 2007;41:346–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coleman RE, Banks LM, Girgis SI, et al. Skeletal effects of exemestane on bone-mineral density, bone biomarkers, and fracture incidence in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer participating in the Intergroup Exemestane Study (IES): a randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ingle JN. Overview of adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors in early breast cancer. Steroids. 2011;76:765–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M, et al. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1135–1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rabaglio M, Sun Z, Price KN, et al. Bone fractures among postmenopausal patients with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer treated with 5 years of letrozole or tamoxifen in the BIG 1-98 trial. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1489–1498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amir E, Seruga B, Niraula S, Carlsson L, Ocaña A. Toxicity of adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1299–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goss PE, Ingle JN, Pritchard KI, et al. Exemestane versus anastrozole in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: NCIC CTG MA.27-a randomized controlled phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1398–1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ingle JN, Schaid DJ, Goss PE, et al. Genome-wide associations and functional genomic studies of musculoskeletal adverse events in women receiving aromatase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4674–4682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu M, Wang L, Bongartz T, et al. Aromatase inhibitors, estrogens and musculoskeletal pain: estrogen-dependent T-cell leukemia 1A (TCL1A) gene-mediated regulation of cytokine expression. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ho MF, Liu M, Wang L, Weinshilboum R, Bongartz T. Aromatase inhibitor treatment and musculoskeletal adverse events: SNP modulated, estrogen-dependent variation in CCR6/CCL20 expression. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(suppl 2):34923361084 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Estrada K, Styrkarsdottir U, Evangelou E, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 56 bone mineral density loci and reveals 14 loci associated with risk of fracture. Nat Genet. 2012;44:491–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li L, Wang H, Yang ES, Arteaga CL, Xia F. Erlotinib attenuates homologous recombinational repair of chromosomal breaks in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9141–9146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Niu N, Qin Y, Fridley BL, et al. Radiation pharmacogenomics: a genome-wide association approach to identify radiation response biomarkers using human lymphoblastoid cell lines. Genome Res. 2010;20:1482–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pei H, Li L, Fridley BL, et al. FKBP51 affects cancer cell response to chemotherapy by negatively regulating Akt. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:259–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ingle JN, Liu M, Wickerham DL, et al. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and pharmacogenomic variation in ZNF423 regulation of BRCA1 expression: individualized breast cancer prevention. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:812–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richards JB, Zheng HF, Spector TD. Genetics of osteoporosis from genome-wide association studies: advances and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:576–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu M, Ingle JN, Fridley BL, et al. TSPYL5 SNPs: association with plasma estradiol concentrations and aromatase expression. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27:657–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang L, McLeod HL, Weinshilboum RM. Genomics and drug response. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1144–1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Therneau TM, Li H. Computing the Cox model for case cohort designs. Lifetime Data Anal. 1999;5:99–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harris SA, Tau KR, Enger RJ, Toft DO, Riggs BL, Spelsberg TC. Estrogen response in the hFOB 1.19 human fetal osteoblastic cell line stably transfected with the human estrogen receptor gene. J Cell Biochem. 1995;59:193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boyce BF, Xing L. Biology of RANK, RANKL, and osteoprotegerin. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(suppl 1):S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Deng FY, Zhao LJ, Pei YF, et al. Genome-wide copy number variation association study suggested VPS13B gene for osteoporosis in Caucasians. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:579–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marie P, Halbout P. [OPG/RANKL: role and therapeutic target in osteoporosis]. Med Sci (Paris). 2008;24:105–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cree MW, Juby AG, Carriere KC. Mortality and morbidity associated with osteoporosis drug treatment following hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:722–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goss P, Bondarenko IN, Manikhas GN, et al. Phase III, double-blind, controlled trial of atamestane plus toremifene compared with letrozole in postmenopausal women with advanced receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4961–4966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Holzer G, Noske H, Lang T, Holzer L, Willinger U. Soluble cathepsin K: a novel marker for the prediction of nontraumatic fractures? J Lab Clin Med. 2005;146:13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lang TH, Willinger U, Holzer G. Soluble cathepsin-L: a marker of bone resorption and bone density? J Lab Clin Med. 2004;144:163–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kneissel M, Luong-Nguyen NH, Baptist M, et al. Everolimus suppresses cancellous bone loss, bone resorption, and cathepsin K expression by osteoclasts. Bone. 2004;35:1144–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Han SH, Chae SW, Choi JY, Kim EC, Chae HJ, Kim HR. Acidic pH environments increase the expression of cathepsin B in osteoblasts: the significance of ER stress in bone physiology. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2009;31:428–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wilson TJ, Nannuru KC, Singh RK. Cathepsin G-mediated activation of pro-matrix metalloproteinase 9 at the tumor-bone interface promotes transforming growth factor-β signaling and bone destruction. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1224–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vakulenko VI, Sapargel'dyev NB, Golub GB. [The protein content and cathepsin D activity of the mandibular bone in rats during fracture healing]. Stomatologiia (Mosk). 1990;69:9–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Geoffroy V, Kneissel M, Fournier B, Boyde A, Matthias P. High bone resorption in adult aging transgenic mice overexpressing cbfa1/runx2 in cells of the osteoblastic lineage. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6222–6233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang M, Amano SU, Flach RJ, Chawla A, Aouadi M, Czech MP. Identification of Map4k4 as a novel suppressor of skeletal muscle differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:678–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bouzakri K, Zierath JR. MAP4K4 gene silencing in human skeletal muscle prevents tumor necrosis factor-α-induced insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7783–7789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]