Abstract

It has been suggested that a key function of music during its development and spread amongst human populations was its capacity to create and strengthen social bonds amongst interacting group members. However, the mechanisms by which this occurs have not been fully discussed. In this paper we review evidence supporting two thus far independently investigated mechanisms for this social bonding effect: self-other merging as a consequence of inter-personal synchrony, and the release of endorphins during exertive rhythmic activities including musical interaction. In general, self-other merging has been experimentally investigated using dyads, which provide limited insight into large-scale musical activities. Given that music can provide an external rhythmic framework that facilitates synchrony, explanations of social bonding during group musical activities should include reference to endorphins, which are released during synchronized exertive movements. Endorphins (and the endogenous opioid system (EOS) in general) are involved in social bonding across primate species, and are associated with a number of human social behaviors (e.g., laughter, synchronized sports), as well as musical activities (e.g., singing and dancing). Furthermore, passively listening to music engages the EOS, so here we suggest that both self-other merging and the EOS are important in the social bonding effects of music. In order to investigate possible interactions between these two mechanisms, future experiments should recreate ecologically valid examples of musical activities.

Keywords: music, rhythm, social bonding, endorphins, self-other merging, synchrony

INTRODUCTION

Music-making, and movement to music, are activities central to ritual, courtship, identity, and human expression cross-culturally. Based on this ubiquity, it is argued that music has played an important role during our evolutionary history (Cross, 2001; Huron, 2001; McDermott, 2008; Dunbar, 2012b; although see, Pinker, 1997 for an alternative perspective).Whilst sexual selection and courtship are proposed as partial explanations for the widespread appreciation and aptitude for music (Brown, 2000; Merker, 2000; Miller, 2000 for a critique), there are other suggestions regarding its positive role for human societies. In this review we focus on the fact that in almost all cultures globally, and throughout history, music is a social activity (Nettl, 1983, 2000) that involves movement to rhythmic sound and plays a significant role both in creating social bonds (Roederer, 1984; McNeill, 1995; Freeman, 2000; Dunbar, 2004) and indicating coalition strength (Hagen and Bryant, 2003). This effect of musical activity on “social bonding” (the psychological experience of increased social closeness, reflected in prosocial behaviors) may be responsible for the widespread occurrence of musical activities and may have played an important role in the evolution of human sociality (Dunbar, 2012a,b).

While there has been much interest in the relationship between music and social bonding, there is as yet no consensus about the mechanisms by which this might occur. Many aspects of music-making which make people feel socially close are not specific to music-based activities, such as sharing attention with co-actors (e.g., Reddy, 2003), working toward similar goals (e.g., Tomasello et al., 2005), and experiencing a sense of positivity after successful co-engagement (e.g., Isen, 1970). An important feature that distinguishes musical activities from other social behavior is the importance of shared rhythms, and the externalization of predictable rhythms that allow synchronization to occur between two or more people (e.g., Bispham, 2006; Merker et al., 2009). Furthermore, people attribute movement and human agency to musical sound (e.g., Cross, 2001), which influences how synchronization occurs (Launay et al., 2013, 2014) as well as impacting upon affective experience (e.g., Fritz et al., 2013a). Here we focus on two proposed mechanisms of social bonding: self-other merging as a consequence of interpersonal synchrony, and the release of endorphins during synchronized exertive movements. We bring together evidence that both pathways from music-making to social bonding are relevant, highlight connections between the two, and suggest that both should be included in any account of how people form and maintain social bonds through music-making.

Firstly, performing movements simultaneously with someone else, (i.e., synchronizing), is believed to cause some blurring of self and other via neural pathways that code for both action and perception (Overy and Molnar-Szakacs, 2009). Secondly, it has been argued that group music-making leads to social bonding due to the release of neurohormones, specifically oxytocin (e.g., Freeman, 2000; Huron, 2001; Grape et al., 2003). The oxytocin account relies on its action as a social neurohormone in a range of mammals (e.g., Insel, 2010), and the suggestion that music-making (which involves sensory overload, physical activity, strong emotional arousal and social behavior) is particularly conducive to oxytocin release (e.g., Freeman, 2000). Whilst elevated oxytocin levels has been linked to increased trust (Kosfeld et al., 2005; Zak et al., 2005), eye contact (Guastella et al., 2008), face memory (Savaskan et al., 2008), generosity (Zak et al., 2007), empathy and the ability to infer the mental state of others (Domes et al., 2007), the causal link between music-related physical experience and oxytocin described by Freeman is tenuous. Here we review the evidence that the endogenous opioid system (EOS), and particularly endorphins, play a central role in the maintenance of non-sexual, non-kinship social bonds (Machin and Dunbar, 2011) that are characteristic of group musical activities. Given that endorphins are argued to mediate the pleasure experienced when listening to music (e.g., Huron, 2006; Koelsch, 2010) and recent evidence demonstrates that endorphins are released during synchronized and exertive activity (Cohen et al., 2010; Sullivan and Rickers, 2013; Sullivan et al., 2014), we argue that this particular peptide is an important candidate for the neurohormonal underpinnings of social bonding during group musical activities.

To begin, we will explore the evidence linking synchronization and social bonding, and subsequently the particular role of self-other merging, which may occur via shared neural pathways for action and perception. Following this we review evidence of the EOS’s role in social bonding, and discuss the case for this mechanism in musical activities. Finally we highlight the importance of using ecologically valid musical contexts in future investigation into the possible relationship between the two mechanisms that underpin the relationship between music and social bonding.

SYNCHRONIZATION AND SOCIAL BONDING

Synchronization is often cited as an important mechanism by which social bonding can occur (Hove and Risen, 2009; Wiltermuth and Heath, 2009; Valdesolo and Desteno, 2011; Launay et al., 2013). This proposition builds in part on an identified relationship between mimicry (i.e., making a similar movement to another individual) and positive social behavior, such as self-reported rapport between two individuals (e.g., LaFrance and Broadbent, 1976; LaFrance, 1979). Mimicry improves rapport between people (Chartrand and Bargh, 1999; Lakin and Chartrand, 2003), which in turn influences the amount of mimicry that people perform (Van Baaren et al., 2004; Stel et al., 2010), thereby causing a positive feedback loop in which people can become increasingly socially close to one another through making similar movements, and more inclined to continue making similar movements once social closeness is established. Synchrony, like mimicry, involves simultaneous movements with another individual, with the additional element of rhythmically matched timing, which requires the prediction of movements of co-actors. Consequently, synchronization is likely to have similar or more pronounced effects on social bonding than mimicry.

People tend to spontaneously and unintentionally synchronize movements with one another, even to some extent when instructed not to do so (Issartel et al., 2007; Oullier et al., 2008; van Ulzen et al., 2008). Those with pro-social tendencies exhibit more spontaneous synchronization than those with pro-self tendencies (Lumsden et al., 2012), and the desirability of a partner can influence whether synchrony occurs (Miles et al., 2010, 2011), suggesting that this is a social behavior, rather than an automatic motor process. Perception of synchrony is also interpreted as a signal of rapport for both basic sounds (e.g., sound of people walking together: Miles et al., 2009; Lakens and Stel, 2011), and more complex musical stimuli (Hagen and Bryant, 2003).

More importantly, there is evidence that synchronization between people can influence their subsequent positive social feelings toward one another. This has been demonstrated in a number of experimental studies, involving participants tapping synchronously with an experimenter (Hove and Risen, 2009; Valdesolo and Desteno, 2011), walking in time with other people (Wiltermuth and Heath, 2009; Wiltermuth, 2012), dancing together (Reddish et al., 2013), and even when people have no visual access to one another but are synchronizing with the sounds of another person (Kokal et al., 2011; Launay et al., 2014).

The likely importance of social bonding via synchrony in music-based activities draws on the observation that beyond a tendency to synchronize with one another, humans have a culturally ubiquitous aptitude for entrainment to rhythmic beats (Clayton et al., 2005; Brown and Jordania, 2011), particularly those embedded in music (e.g., Demos et al., 2012). However, the source and context associated with those rhythms are paramount. For example, Kirschner and Tomasello (2009) demonstrated that children’s synchronization with a beat is improved in the presence of a person compared to when interacting solely with an isochronously beating drum. This suggests that from a young age, the awareness of agency related to perceived sound (and belief that the sound is produced by the intentional movements of another person) encourages synchronization with that sound, thereby likely influencing the social bonding effects of musical activities. Agent-driven sounds, and the associated perception of movement of another person, engage motor regions in the listener’s brain, potentially resulting in “self-other merging,” which has been argued to arise when individuals experience their movement simultaneously with another’s.

SELF-OTHER MERGING AND SOCIAL BONDING

When moving at the same time as others we experience some co-activation of neural networks that relate to movement of self (as action), and other (as perception; e.g., Overy and Molnar-Szakacs, 2009). There is much recent research investigating the relationship between perception and action (Buccino et al., 2001; Fadiga et al., 2002; Rizzolatti, 2005; Caetano et al., 2007), which has identified “mirror neurons” in macaques (Gallese et al., 1996; Rizzolatti et al., 1996) that selectively respond to the macaque’s own movement and perception of the goal-directed movement of others. While there is no evidence for neurons with equivalent selectivity in humans (Hickok, 2009), this research led to much interest into how perception of goal-directed movement can engage regions of the brain related to making similar movements (Rizzolatti, 2005). Importantly it is now well recognized that perceiving the actions of another person can lead to activation of the same neural motor networks involved in making those actions oneself (e.g., Fadiga et al., 1995).

When our own actions match those of another’s, it is possible that the intrinsic and extrinsic engagement of neural action-perception networks make it difficult to distinguish between self and perceived other, thus creating at least a transient bond between the two (Decety and Sommerville, 2003; Sebanz et al., 2006; Sommerville and Decety, 2006; Knoblich and Sebanz, 2008; Marsh et al., 2009; Overy and Molnar-Szakacs, 2009). A well replicated experimental example of this is the rubber hand illusion (Botvinick and Cohen, 1998). In this paradigm, a participant’s arm is hidden from sight, and a replacement rubber arm is visible where their own arm is expected. While they view the rubber hand being touched with a paintbrush, their own (hidden) hand is simultaneously touched with a paintbrush, with synchronized strokes. This matching of visual and tactile input leads to an increased subjective sense that the rubber hand is part of the participant’s body. The effect disappears when the two inputs are not synchronized. This provides evidence that self-other blurring is possible even with an inanimate object, and some aspects of this are likely to apply to human–human synchronized interaction. Indeed, behavioral synchrony has also been demonstrated to induce common neural signatures between interacting agents (Oullier et al., 2005; Tognoli et al., 2007; Lindenberger et al., 2009; Dumas et al., 2010). However, evidence for common neural signatures during synchronization should be interpreted with caution, as it can only indicate that similar cortical networks are involved in making the same movements for different people.

Researchers who argue that self-other merging is an important part of the bonding effects of synchronization primarily draw support from dyadic experiments in which participants’ actions are perceived to occur at the same time as one another. Theoretically, dyads are capable of achieving synchrony with relative ease simply because there is only one other person to keep track of. As such, synchrony is reasonably attainable, and associated self-other merging (and bonding) effects are likely to be achieved fairly easily.

Musical activities, on the other hand, are not limited to one-on-one interactions, and have historically involved groups (Nettl, 1983, 2000). With large numbers of people, it is difficult to simultaneously observe the movements of all the other participants, making self-other merging a less likely prospect. Rhythm provides an external, predictable scaffolding that can facilitate synchrony with both the music, and by extension, aids synchrony between individuals engaging in the same musical experience. A recent experiment involved people rocking on rocking chairs with one another, while music played in the room or did not (Demos et al., 2012). While self-reported rapport between co-actors correlated with synchronization achieved with the music, rapport did not correlate with synchronization that occurred between co-actors. This implies that externalizing the target of synchrony (e.g., to music) allows bonding with other people present, in the absence of explicit synchrony between those people. This finding has important implications given that group musical activities often involve non-identical movements between people (making self-other merging an unlikely prospect).

Given that the self-other merging account of social bonding relies on simultaneous, similar movements, it is likely that this mechanism does not provide a complete account for the bonding that arises in large group situations. Additional mechanisms need to be considered, in particular mechanisms that underpin the social bonding associated with musical activities. One likely mechanism involves the EOS, and particularly endorphins, which are released through synchronous and exertive activities, and during passive engagement with music, and play a central role in social bonding among primate species (e.g., Keverne et al., 1989).

ENDORPHINS AND SOCIAL BONDING

Investigation into the neuropeptide underpinnings of social bonding have implicated neurohormonal cascades involving oxytocin and vasopressin (e.g., Carter, 1998), dopamine and serotonin (e.g., Depue and Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005), and endorphins released by the EOS (Curley and Keverne, 2005; Dunbar, 2010). Recently, oxytocin has been promoted as the social neurohormone (Bartz et al., 2011; Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2011), largely due to evidence from pair-bonding and mother-infant bonding (e.g., Atzil et al., 2011; Feldman, 2012). However, despite apparent interactions between opioids (specifically endorphins) in the bonding activity of oxytocin (e.g., Depue and Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005), and evidence of the EOS’s role in primate pair-bonding (Ragen et al., 2013), maternal care (Martel et al., 1993), as well as empirical evidence that increased opioid levels are associated with social grooming and affiliative behaviors in non-sexual, non-kin related conspecifics (Keverne et al., 1989; Schino and Troisi, 1992; Martel et al., 1995), the role of the EOS in social bonding remains relatively underexplored, possibly due to the difficulties in measuring endorphin titres directly (Dearman and Francis, 1983).

The EOS consists of opioid receptors and associated ligands distributed throughout the central nervous system and peripheral tissues, such as the nucleus accumbens (Fields, 2007; Trigo et al., 2010). The EOS is central in opioid-mediated reward (Koob, 1992; Olmstead and Franklin, 1997; Comings et al., 1999), social motivation (Chelnokova et al., 2014), and pleasure and pain perception (Janal et al., 1984; Leknes and Tracey, 2008). Elevated opioid levels are correlated with feelings of euphoria (Boecker et al., 2008), and Koepp et al. (2009) report activation of general opioid receptors in the hippocampus and amygdala in response to positive affect. Deactivation of certain opioid receptor sites has been associated with negative affect (Zubieta et al., 2003).

The possible role of the EOS in social bonding is formalized in the brain opioid theory of social attachment (BOTSA). BOTSA is based on evidence of behavioral and emotional similarities between those in intense relationships, and those addicted to narcotics (Insel, 2003). Furthermore, endogenous opioids, particularly endorphins, are related to social bonding in many non-human animals such as rhesus macaques (Schino and Troisi, 1992; Graves et al., 2002), other monkeys (Keverne et al., 1989; Martel et al., 1995; Ragen et al., 2013), voles (Resendez et al., 2013), puppies, rats and chicks (Panksepp et al., 1980), and mammals generally (Broad et al., 2006). Given the role of endorphins in bonding in other species, it is plausible that the EOS may also underpin human social bonds (Matthes et al., 1996; Moles et al., 2004; Depue and Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005; Dunbar, 2010).

Opioids are released in response to low levels of muscular and psychological stress (Howlett et al., 1984), for example during exercise (Harbach et al., 2000). Positron emission tomography (PET) scans have confirmed the euphoric state that follows exercise (termed “runner’s high”) is due to endogenous opioids (Boecker et al., 2008). Further to the effect on mood, opioids have an analgesic effect (Van Ree et al., 2000), and much evidence suggests that endorphins are central in the pain management system (D’Amato and Pavone, 1993; Benedetti, 1996; Zubieta et al., 2001; Fields, 2007; Bodnar, 2008; Dishman and O’Connor, 2009; Mueller et al., 2010). Given that direct measures of endogenous opioids are costly and invasive (Dearman and Francis, 1983), pain threshold is a commonly used proxy measure of endorphin release, and this has been operationalised using the length of time holding a hand in ice water (Dunbar et al., 2012a,b), a ski exercise (maintaining a squat position with legs at right angles: Dunbar et al., 2012a), an electrocutaneous simulator (Jamner and Leigh, 1999), pressure produced using a blood pressure cuff (Cogan et al., 1987; Cohen et al., 2010; Dunbar et al., 2012a,b), and the amount of pain medication requested by patients (Zillmann et al., 1993).

According to pain threshold assays, various exertive human social bonding activities, such as laughter (Dezecache and Dunbar, 2012; Dunbar et al., 2012a), group synchronized sport (Cohen et al., 2010; Sullivan and Rickers, 2013), and singing and dance (Dunbar et al., 2012b), trigger endorphin release. Specifically, synchronized exertive activity (such as rowing) elevates pain thresholds significantly more than non-synchronized exertion (Sullivan and Rickers, 2013; Sullivan et al., 2014), suggesting that rhythmic, music-based activities may similarly facilitate endorphin release.

ENDORPHINS AND MUSIC

Based on the association between exertion and endorphin release, a number of studies have investigated the effect of active engagement in musical activities (i.e., involving overt movement) and the EOS (see Table 1). For example, sufficiently vigorous singing, dancing, and drumming trigger a significantly larger increase in pain threshold and positive affect compared to listening to music and engaging in low energy musical activities (Dunbar et al., 2012b). In a recent set of studies, exercise machines were linked to musical output software such that individuals “created” music as they exerted themselves (Fritz et al., 2013a,b). These experiments demonstrated that when movement (during group exercise) results in musical feedback, participants perceived exertion to be lower (Fritz et al., 2013b), reported enhanced mood, and felt a greater desire to exert themselves further (Fritz et al., 2013a), in comparison to when they were exercising whilst listening (passively) to independently provided music. As such, perception of agency in a musical setting is associated with greater endorphin activation and may therefore lead to greater effects in terms of mood and ability to withstand strenuous exercise.

Table 1.

Summary of studies providing evidence for the role of EOS in music-related activities.

| Passive listening | Active engagement | |

|---|---|---|

| Pain threshold, pain management | Post-operative pain: Koch et al. (1998), Allen et al. (2001), Good et al. (2001), Lepage et al. (2001), Nilsson et al. (2001, 2003), Nilsson (2008), Bernatzky et al. (2011) for a review see Cepeda et al. (2006) | Singing, drumming, dance: Dunbar et al. (2012b) |

| Brain activation regions | EOS, pleasure, and reward circuits: Blood and Zatorre (2001), Stefano et al. (2004), Menon and Levitin (2005) Nucleus accumbens and pleasure states: Koelsch (2014) |

|

| Emotions and mood | Techno-music: Gerra et al. (1998) Emotional effects of music: Koelsch (2010) Positive affect: Huron (2006) |

Increased positive affect: Dunbar et al. (2012b) Enhanced mood: Fritz et al. (2013a) |

| Health | Lower blood pressure and relaxation: Chiu and Kumar (2003), Stefano et al. (2004) Anxiolytic music: McKinney et al. (1997b) |

|

| Other | Musical “thrills”: Goldstein (1980), Panksepp (1995), Menon and Levitin (2005) | Perception of exertion and desire to exert oneself: Fritz et al. (2013b) |

However, activation of the EOS through music is not limited exclusively to situations involving exertion (see Table 1). Listening to music reportedly helps to manage pre-operative hypertension and psychological stress (Allen et al., 2001), reduces sedative requirements during spinal anesthesia (Lepage et al., 2001) and other surgical procedures (Koch et al., 1998), decreases perception of pain (Good et al., 2001; Nilsson et al., 2003) thereby diminishing the need for opioid agonists following operative care (Cepeda et al., 2006; Bernatzky et al., 2011), and improves post-operative recovery (Nilsson et al., 2001). Many of the experiments in this area directly attribute these results to the EOS, and given the strong role of opioid receptor activation in analgesia (Leknes and Tracey, 2008), the body of work linking music and pain may generally be considered convincing evidence of the role of opioid activation.

Positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) research also provide evidence that passive listening to music activates the EOS and brain areas associated with pleasure and reward (Blood and Zatorre, 2001; Stefano et al., 2004). For example, recent evidence that music listening is associated with activation in areas such as the nucleus accumbens (Brown et al., 2004; Menon and Levitin, 2005; Koelsch, 2014), the high number of opioid receptors in this region (Fields, 2007; Trigo et al., 2010) and the role of opioids in mood and pleasure states (Berridge and Kringelbach, 2008) provide support for the theory that the EOS is involved in music listening.

The importance of the EOS in regulating affective experiences in response to music (Zubieta et al., 2003) is further supported by evidence linking music induced “thrills” to endorphin activation (Goldstein, 1980), and the EOS’s association with reward circuits (Menon and Levitin, 2005). In addition, the sense of elation that arises when engaging in musical activities has been attributed to endorphin release (Chiu and Kumar, 2003; Huron, 2006; Dunbar, 2009). Calming music is thought to act via the EOS by buffering the effect of stressful events (see McKinney et al., 1997b for a review), and relaxation following music listening is also linked to the EOS (Stefano et al., 2004). Gerra et al. (1998) report that listening to techno-music significantly changes emotional states (and increases beta-endorphin levels), due to its strong rhythmic beat and engagement of motor regions of the brain. Activation of the EOS, and its role in various affective, calming and analgesic effects, is therefore evident in cases of passive music listening, although a systematic investigation of this effect is still lacking.

It is important to note that there is also some evidence indicating that neurohormones other than endorphins are involved during music-based activities (e.g., Grape et al., 2003; Bachner-Melman et al., 2005; Chanda and Levitin, 2013). In a recent review, Chanda and Levitin (2013) highlight evidence suggesting that stress and arousal effects associated with music-based activities can be linked to cortisol, corticotrophin-releasing hormone and adrenocorticotropic hormone (e.g., McKinney et al., 1997a; Gerra et al., 1998). Various immunity benefits of music have been attributed to, inter alia, cortisol (e.g., Beck et al., 2000; Kuhn, 2002), cytokinin (e.g., Stefano et al., 2004), and growth hormones (e.g., Gerra et al., 1998). Finally, dopamine is key in reward and motivation circuits during musical activities (e.g., Salimpoor et al., 2011), which are likely to interact synergistically with the EOS in mediating the pleasure states associated with music (Chanda and Levitin, 2013). While we argue for further investigation of the EOS as a potential mediator of the positive social effects of musical engagement, it may be difficult to separate out the role of this hormone from other neurochemicals involved in these experiences.

As indicated by the evidence reviewed above, the way that we experience music, whether during passive listening or active engagement, appears to involve the EOS, and endorphins specifically. In the following section we discuss how both self-other merging and the EOS mechanisms might underpin our musical experiences.

FROM MUSIC TO SOCIAL BONDING

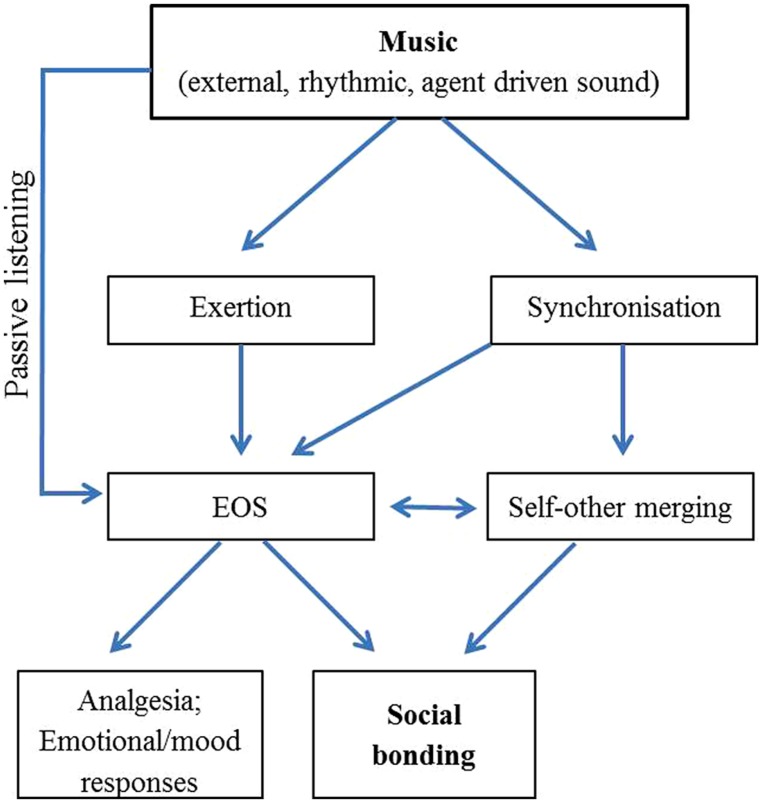

Both self-other merging and the EOS help explain the subjective experience of social bonding that can arise during musical activities, as illustrated by Figure 1. However, as these two mechanisms have thus far been independently investigated, the interplay between them remains unclear.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating possible direction of causality, and relationship between, mechanisms behind the social bonding effects of music.

As mentioned previously, dyads are capable of achieving synchrony with relative ease (even without music), while in larger groups, synchrony is facilitated via rhythmic scaffolding. Additionally, as music encourages movement (Janata and Grafton, 2003; Madison, 2006; Madison et al., 2011; Janata et al., 2012) by engaging motor regions of the brain (Levitin and Menon, 2003), we might expect engagement with musical sounds to be more exertive than with non-musical sounds. The combination of larger movements and the externalization of the target of synchrony likely facilitates synchronization.

Exertive movements cause affiliative sentiments and behaviors (e.g., Mueller et al., 2003), have effects on mood and emotion (e.g., Karageorghis and Terry, 2009), and, in combination with synchrony, can elevate pain thresholds (e.g., Cohen et al., 2010). These phenomena are all strongly associated with the EOS (e.g., Dishman and O’Connor, 2009). Accordingly, we propose that self-other matching and activation of the EOS are interconnected in explaining the bonding effects that arise during active engagement in group music-based activities, with a possibility that the EOS underpins the psychological experience of self-other merging.

In terms of passive listening to music, the literature reviewed here suggests that the EOS is likely to play a role also in the absence of explicit movement and self-other merging during synchrony. Dynamic attending theory (e.g., Jones and Boltz, 1989) suggests that through monitoring of events occurring with predictable temporal patterns we can become entrained to those events. This rhythmic predictability has been suggested to play a key role in the pleasure experienced when listening to music, which may be mediated by the release of endorphins (Huron, 2006; Margulis, 2013). The effect of tempo on arousal (Husain et al., 2002) and the strong ability for music to alter mood (Thayer et al., 1994) and motivational states (Frijda and Zeelenberg, 2001) are both congruous with evidence that EOS activation occurs in the brain when listening and entraining to music (Blood and Zatorre, 2001; Stefano et al., 2004; Menon and Levitin, 2005). Sievers et al. (2013) demonstrate that movement and music are processed cross-modally, as are the emotions expressed through movement and music. Elements of music significantly affect various dimensions of imagery relating to motion (Eitan and Granot, 2006), and listening to music may itself induce thoughts about movement, whether conscious or subconscious (Chen et al., 2008; Levitin and Tirovolas, 2009; Clarke, 2011). Through activation of motor regions of the brain during music listening (Levitin and Menon, 2003), passive engagement with music likely triggers the same neural pathways involved in active engagement (i.e. movement) to music, including pathways implicating the EOS. This activity in motor regions of the brain during music perception is likely to underlie the self-reported experience of “embodied movement” even when listening and not moving to music (e.g., Peters, 2010).

CONCLUSION

While most accounts of the relationship between music and social bonding have focused separately on self-other merging via synchrony or neurohormonal mechanisms, here we suggest that associations between the two need to be considered, especially when assessing large-scale musical activities. Future work should be directed toward ecologically valid musical experiences involving groups of people interacting with one another rather than dyadic interaction, exertive movements rather than small movements, and movements that are temporally co-ordinated rather than synchronized per se. Using these forms of musical activity it will become possible to explore the relative importance of self-other matching and EOS in music-based activities (including passive listening). Given that humans have significantly larger and more complex social networks than our primate cousins, research in this field will elucidate the means by which our species has the capacity to bond with large groups of conspecifics at the same time. It is likely that some combination of endorphin release and self-other merging lead to the social bonding effects of music, although the relationship between the two mechanisms remains to be sufficiently explored.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the European Research Council (Grant Number 295663) for its funding support during the writing of this article, and Cole Robertson for commenting on a draft of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Allen K., Golden L. H., Izzo J. L., Ching M. I., Forrest A., Niles C. R., et al. (2001). Normalization of hypertensive responses during ambulatory surgical stress by perioperative music. Psychosom. Med. 63 487–492 10.1097/00006842-200105000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzil S., Hendler T., Feldman R. (2011). Specifying the neurobiological basis of human attachment: brain, hormones, and behavior in synchronous and intrusive mothers. Neuropsychopharmacology 36 2603–2615 10.1038/npp.2011.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachner-Melman R., Dina C., Zohar A. H., Constantini N., Lerer E., Hoch S., et al. (2005). AVPR1a and SLC6A4 gene polymorphisms are associated with creative dance performance. PLoS Genet. 1:e42 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartz J. A., Simeon D., Hamilton H., Kim S., Crystal S., Braun A., et al. (2011). Oxytocin can hinder trust and cooperation in borderline personality disorder. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 6 556–563 10.1093/scan/nsq085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck R. J., Cesario T. C., Yousefi A., Enamoto H. (2000). Choral singing, performance perception, and immune system changes in alivary immunoglobulin a and cortisol. Music Percept. Interdiscip. J. 18 87–106 10.2307/40285902 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti F. (1996). The opposite effects of the opiate antagonist naloxone and the cholecystokinin antagonist proglumide on placebo analgesia. Pain 64 535–543 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00179-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernatzky G., Presch M., Anderson M., Panksepp J. (2011). Emotional foundations of music as a non-pharmacological pain management tool in modern medicine. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35 1989–1999 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge K. C., Kringelbach M. L. (2008). Affective neuroscience of pleasure: reward in humans and animals. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 199 457–480 10.1007/s00213-008-1099-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bispham J. (2006). Rhythm in music: what is it? Who has it? And why? Music Percept. 24 125–134 10.1525/mp.2006.24.2.125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blood A. J., Zatorre R. J. (2001). Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 11818–11823 10.1073/pnas.191355898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar R. J. (2008). Endogenous opiates and behavior: 2007. Peptides 29 2292–2375 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boecker H., Sprenger T., Spilker M. E., Henriksen G., Koppenhoefer M., Wagner K. J., et al. (2008). The runner’s high: opioidergic mechanisms in the human brain. Cereb. Cortex 18 2523–2531 10.1093/cercor/bhn013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick M., Cohen J. (1998). Rubber hands “feel” touch that eyes see. Nature 391:756 10.1038/35784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broad K. D., Curley J. P., Keverne E. B. (2006). Mother-infant bonding and the evolution of mammalian social relationships. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 361 2199–2214 10.1098/rstb.2006.1940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. (2000). “Evolutionary models of music: from sexual selection to group selection,” in Perspectives in Ethology eds Tonneau F., Thompson N. S. (New York: Plenum; ) 221–281 [Google Scholar]

- Brown S., Jordania J. (2011). Universals in the world’s musics. Psychol. Music 41 229–248 10.1177/0305735611425896 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S., Martinez M. J., Parsons L. M. (2004). Passive music listening spontaneously engages limbic and paralimbic systems. Neuroreport 15 2033–2037 10.1097/00001756-200409150-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccino G., Binkofski F., Fink G. R., Fadiga L., Fogassi L., Gallese V., et al. (2001). Action observation activates premotor and parietal areas in a somatotopic manner: an fMRI study. Eur. J. Neurosci. 13 400–404 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2001.01385.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano G., Jousmäki V., Hari R. (2007). Actor’s and observer’s primary motor cortices stabilize similarly after seen or heard motor actions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 9058–9062 10.1073/pnas.0702453104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter C. S. (1998). Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love. Psychoneuroendocrinology 23 779–818 10.1016/S0306-4530(98)00055-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda M. S., Carr D. B., Lau J., Alvarez H. (2006). Music for pain relief (review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD004843 10.1002/14651858.CD004843.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda M. L., Levitin D. J. (2013). The neurochemistry of music. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17 179–193 10.1016/j.tics.2013.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand T. L., Bargh J. (1999). The chameleon effect: the perception-behavior link and social interaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 76 893–910 10.1037/0022-3514.76.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelnokova O., Laeng B., Eikemo M., Riegels J., Løseth G., Maurud H., et al. (2014). Rewards of beauty: the opioid system mediates social motivation in humans. Mol. Psychiatry 19 746–747 10.1038/mp.2014.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. L., Penhune V. B., Zatorre R. J. (2008). Listening to musical rhythms recruits motor regions of the brain. Cereb. Cortex 18 2844–2854 10.1093/cercor/bhn042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu P., Kumar A. (2003). Music therapy: loud noise or soothing notes. Int. Pediatr. 18 204–208 [Google Scholar]

- Clarke E. F. (2011). “Music perception and musical consciousness,” in Music and Consciousness: Philosophical, Psychological, and Cultural Perspectives, eds Clarke D., Clarke E. F. (New York: Oxford University Press; ), 193–213 [Google Scholar]

- Clayton M., Sager R., Will U. (2005). In time with the music: the concept of entrainment and its significance for ethnomusicology. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 11 3–142 [Google Scholar]

- Cogan R., Cogan D., Waltz W., McCue M. (1987). Effects of laughter and relaxation on discomfort thresholds. J. Behav. Med. 10 139–144 10.1007/BF00846422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E. E. A., Ejsmond-Frey R., Knight N., Dunbar R. I. M. (2010). Rowers’ high: behavioural synchrony is correlated with elevated pain thresholds. Biol. Lett. 6 106–108 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comings D. E., Blake H., Dietz G., Gade-Andavolu R., Legro R. S., Saucier G., et al. (1999). The proenkephalin gene (PENK) and opioid dependence. Neuroreport 10 1133–1135 10.1097/00001756-199904060-00042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross I. (2001). Music, cognition, culture, and evolution. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 930 28–42 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05723.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley J. P., Keverne E. B. (2005). Genes, brains and mammalian social bonds. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20 561–567 10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato F. R., Pavone F. (1993). Endogenous opioids: a proximate reward mechanism for kin selection? Behav. Neural Biol. 60 79–83 10.1016/0163-1047(93)90768-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearman J., Francis K. T. (1983). Plasma levels of catecholamines, cortisol, and beta-endorphins in male athletes after running 26.2, 6, and 2 miles. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 23 30–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J., Sommerville J. A. (2003). Shared representations between self and other: a social cognitive neuroscience view. Trends Cogn. Sci. 7 527–533 10.1016/j.tics.2003.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demos A. P., Chaffin R., Begosh K. T., Daniels J. R., Marsh K. L. (2012). Rocking to the beat: effects of music and partner’s movements on spontaneous interpersonal coordination. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 141 49–53 10.1037/a0023843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue R. A., Morrone-Strupinsky J. V. (2005). A neurobehavioral model of affiliative bonding: implications for conceptualizing a human trait of affiliation. Behav. Brain Sci. 28 313–395 10.1017/S0140525X05000063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dezecache G., Dunbar R. I. M. (2012). Sharing the joke: the size of natural laughter groups. Evol. Hum. Behav. 33 775–779 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2012.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dishman R. K., O’Connor P. J. (2009). Lessons in exercise neurobiology: the case of endorphins. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2 4–9 10.1016/j.mhpa.2009.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domes G., Heinrichs M., Michel A., Berger C., Herpertz S. C. (2007). Oxytocin improves “mind-reading” in humans. Biol. Psychiatry 61 731–733 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas G., Nadel J., Soussignan R., Martinerie J., Garnero L. (2010). Inter-brain synchronization during social interaction. PLoS ONE 5:e12166 10.1371/journal.pone.0012166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar R. I. M. (2004). “Language, music, and laughter in evolutionary perspective,” in Evolution of Communication Systems: A Comparative Approach, eds Oller D. K., Griebel U. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; ) 257–274 [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar R. I. M. (2009). “Mind the bonding gap: constraints on the evolution of hominin societies,” in Pattern and Process in Cultural Evolution ed.Shennan S. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; ) 223–234 [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar R. I. M. (2010). The social role of touch in humans and primates: behavioural function and neurobiological mechanisms. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 34 260–268 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar R. I. M. (2012a). Bridging the bonding gap: the transition from primates to humans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367 1837–1846 10.1098/rstb.2011.0217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar R. I. M. (2012b). “On the evolutionary function of song and dance,” in Music, Language and Human Evolution, eds Bannan N., Mithen S. (Oxford: Oxford University Press; ) 201–214 [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar R. I. M., Baron R., Frangou A., Pearce E., Van Leeuwen E. J. C., Stow J., et al. (2012a). Social laughter is correlated with an elevated pain threshold. Proc. Biol. Sci. 279 1161–1167 10.1098/rspb.2011.1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar R. I. M., Kaskatis K., MacDonald I., Barra V. (2012b). Performance of music elevates pain threshold and positive affect: implications for the evolutionary function of music. Evol. Psychol. 10 688–702 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitan Z., Granot R. Y. (2006). How music moves. Music Percept. 23 221–248 10.1525/mp.2006.23.3.221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fadiga L., Craighero L., Buccino G., Rizzolatti G. (2002). Speech listening specifically modulates the excitability of tongue muscles: a TMS study. Eur. J. Neurosci. 15 399–402 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01874.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadiga L., Fogassi L., Pavesi G., Rizzolatti G. (1995). Motor facilitation during action observation: a magnetic stimulation study. J. Neurophysiol. 73 2608–2611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R. (2012). Oxytocin and social affiliation in humans. Horm. Behav. 61 380–391 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields H. L. (2007). Understanding how opioids contribute to reward and analgesia. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 32 242–246 10.1016/j.rapm.2007.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman W. J., III. (2000). “A neurobiological role of music in social bonding,” in The Origins of Music, eds Wallin N., Merkur B., Brown S. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; ) 411–424 [Google Scholar]

- Frijda N., Zeelenberg M. (2001). “Appraisal: what is the dependent?” in Appraisal Processes in Emotion, eds Davidson R. J., Ekman P., Scherer K. R. (Oxford: Oxford University Press; ) 141–155 [Google Scholar]

- Fritz T. H., Halfpaap J., Grahl S., Kirkland A., Villringer A. (2013a). Musical feedback during exercise machine workout enhances mood. Front. Psychol. 4:921 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz T. H., Hardikar S., Demoucron M., Niessen M., Demey M., Giot O., et al. (2013b). Musical agency reduces perceived exertion during strenuous physical performance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 17784–17789 10.1073/pnas.1217252110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallese V., Fadiga L., Fogassi L., Rizzolatti G. (1996). Action recognition in the premotor cortex. Brain 119(Pt 2) 593–609 10.1093/brain/119.2.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerra G., Zaimovic A., Franchini D., Palladino M., Giucastro G., Reali N., et al. (1998). Neuroendocrine responses of healthy volunteers to “techno-music”: relationships with personality traits and emotional state. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 28 99–111 10.1016/S0167-8760(97)00071-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein A. (1980). Thrills in response to music and other stimuli. Physiol. Psychol. 8 126–129 10.3758/BF03326460 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Good M., Stanton-Hicks M., Grass J. A., Anderson G. C., Lai H. L., Roykulcharoen V., et al. (2001). Relaxation and music to reduce postsurgical pain. J. Adv. Nurs. 33 208–215 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01655.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grape C., Sandgren M., Hansson L.-O., Ericson M., Theorell T. (2003). Does singing promote well-being?: an empirical study of professional and amateur singers during a singing lesson. Integr. Physiol. Behav. Sci. 38 65–74 10.1007/BF02734261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves F. C., Wallen K., Maestripieri D. (2002). Opioids and attachment in rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) abusive mothers. Behav. Neurosci. 116 489–493 10.1037//0735-7044.116.3.489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastella A. J., Mitchell P. B., Dadds M. R. (2008). Oxytocin increases gaze to the eye region of human faces. Biol. Psychiatry 63 3–5 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen E. H., Bryant G. A. (2003). Music and dance as a coalition signalling system. Hum. Nat. 14 21–51 10.1007/s12110-003-1015-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbach H., Hell K., Gramsch C., Katz N., Hempelmann G., Teschemacher H. (2000). Beta-endorphin (1-31) in the plasma of male volunteers undergoing physical exercise. Psychoneuroendocrinology 25 551–562 10.1016/S0306-4530(00)00009-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G. (2009). Eight problems for the mirror neuron theory of action understanding in monkeys and humans. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21 1229–1243 10.1162/jocn.2009.21189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hove M. J., Risen J. L. (2009). It’s all in the timing: interpersonal synchrony increases affiliation. Soc. Cogn. 27 949–961 10.1521/soco.2009.27.6.949 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett T. A., Tomlin S., Ngahfoong L., Rees L. H., Bullen B. A., Skrinar G. S., et al. (1984). Release of beta endorphin and met-enkephalin during exercise in normal women: response to training. Br. Med. J. 288 1950–1952 10.1136/bmj.288.6435.1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huron D. (2001). Is music an evolutionary adaptation? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 930 43–61 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05724.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huron D. (2006). Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press [Google Scholar]

- Husain G., Thompson W. F., Schellenberg E. G. (2002). Effects of musical tempo and mode on arousal, mood, and spatial abilities. Music Percept. 20 151–171 10.1525/mp.2002.20.2.151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T. R. (2003). Is social attachment an addictive disorder? Physiol. Behav. 79 351–357 10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00148-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T. R. (2010). The challenge of translation in social neuroscience: a review of oxytocin, vasopressin, and affiliative behavior. Neuron 65 768–779 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isen A. M. (1970). Success, failure, attention, and reaction to others: the warm glow of success. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 15 294–301 10.1037/h0029610 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Issartel J., Marin L., Cadopi M. (2007). Unintended interpersonal co-ordination: “can we march to the beat of our own drum?” Neurosci. Lett. 411 174–179 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.09.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamner L. D., Leigh H. (1999). Repressive/defensive coping, endogenous opioids and health: how a life so perfect can make you sick. Psychiatry Res. 85 17–31 10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00134-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janal M. N., Colt E. W., Clark W. C., Glusman M. (1984). Pain sensitivity, mood and plasma endocrine levels in man following long-distance running: effects of naloxone. Pain 19 13–25 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90061-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janata P., Grafton S. T. (2003). Swinging in the brain: shared neural substrates for behaviors related to sequencing and music. Nat. Neurosci. 6 682–687 10.1038/nn1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janata P., Tomic S. T., Haberman J. M. (2012). Sensorimotor coupling in music and the psychology of the groove. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 141 54–75 10.1037/a0024208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. R., Boltz M. (1989). Dynamic attending and responses to time. Psychol. Rev. 96 459–491 10.1037/0033-295X.96.3.459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karageorghis C. I., Terry P. C. (2009). “The psychological, psychophysical, and ergogenic effects of music in sport: a review and synthesis,” in Sporting Sounds: Relationships Between Sport and Music, eds Bateman A., Bale J. (London: Routeledge; ) 13–36 [Google Scholar]

- Keverne E. B., Martensz N. D., Tuite B. (1989). Beta-endorphin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid of monkeys are influenced by grooming relationships. Psychoneuroendocrinology 14 155–161 10.1016/0306-4530(89)90065-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner S., Tomasello M. (2009). Joint drumming: social context facilitates synchronization in preschool children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 102 299–314 10.1016/j.jecp.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblich G., Sebanz N. (2008). Evolving intentions for social interaction: from entrainment to joint action. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363 2021–2031 10.1098/rstb.2008.0006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M. E., Kain Z. N., Ayoub C., Rosenbaum S. H. (1998). The sedative and analgesic sparing effect of music. Anesthesiology 89 300–306 10.1097/00000542-199808000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S. (2010). Towards a neural basis of music-evoked emotions. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14 131–137 10.1016/j.tics.2010.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelsch S. (2014). Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15 170–180 10.1038/nrn3666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepp M. J., Hammers A., Lawrence A. D., Asselin M. C., Grasby P. M., Bench C. J. (2009). Evidence for endogenous opioid release in the amygdala during positive emotion. Neuroimage 44 252–256 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokal I., Engel A., Kirschner S., Keysers C. (2011). Synchronized drumming enhances activity in the caudate and facilitates prosocial commitment-if the rhythm comes easily. PLoS ONE 6:e27272 10.1371/journal.pone.0027272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob G. F. (1992). Drugs of abuse: anatomy, pharmacology and function of reward pathways. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 13 177–184 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90060-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosfeld M., Heinrichs M., Zak P. J., Fischbacher U., Fehr E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature 435 673–676 10.1038/nature03701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn D. (2002). The effects of active and passive participation in musical activity on the immune system as measured by salivary immunoglobulin a (siga). J. Music Ther. 39 30–39 10.1093/jmt/39.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFrance M. (1979). Nonverbal synchrony and rapport: analysis by the cross-lag panel technique. Soc. Psychol. Q. 42 66–70 10.2307/3033875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LaFrance M., Broadbent M. (1976). Group rapport: posture sharing as a nonverbal indicator. Group Organ. Stud. 1 328–333 10.1177/105960117600100307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lakens D., Stel M. (2011). If they move in sync, they must feel in sync: movement synchrony leads to attributions of rapport and entitativity. Soc. Cogn. 29 1–14 10.1521/soco.2011.29.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lakin J. L., Chartrand T. L. (2003). Using nonconscious behavioral mimicry to create affiliation and rapport. Psychol. Sci. 14 334–339 10.1111/1467-9280.14481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launay J., Dean R. T., Bailes F. (2013). Synchronization can influence trust following virtual interaction. Exp. Psychol. 60 53–63 10.1027/1618-3169/a000173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launay J., Dean R. T., Bailes F. (2014). Synchronising movements with the sounds of a virtual partner enhances partner likeability. Cogn. Process. 10.1007/s10339-014-0618-0 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leknes S., Tracey I. (2008). A common neurobiology for pain and pleasure. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9 314–320 10.1038/nrn2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage C., Drolet P., Girard M., Grenier Y., De Gagné R. (2001). Music decreases sedative requirements during spinal anesthesia. Anesth. Analg. 93 912–916 10.1097/00000539-200110000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitin D. J., Menon V. (2003). Musical structure is processed in “language” areas of the brain: a possible role for Brodmann Area 47 in temporal coherence. Neuroimage 20 2142–2152 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitin D. J., Tirovolas A. K. (2009). Current advances in the cognitive neuroscience of music. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1156 211–231 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04417.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger U., Li S.-C., Gruber W., Müller V. (2009). Brains swinging in concert: cortical phase synchronization while playing guitar. BMC Neurosci. 10:22 10.1186/1471-2202-10-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden J., Miles L. K., Richardson M. J., Smith C. A., Macrae C. N. (2012). Who syncs? Social motives and interpersonal coordination. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48 746–751 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.12.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Machin A. J., Dunbar R. I. M. (2011). The brain opioid theory of social attachment: a review of the evidence. Behaviour 148 985–1025 10.1163/000579511X596624 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madison G. S. (2006). Experiencing groove induced by music: consistency and phenomenology. Music Percept. Interdiscip. J. 24 201–208 10.1525/mp.2006.24.2.201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madison G. S., Gouyon F., Ullén F., Hörnström K. (2011). Modeling the tendency for music to induce movement in humans: first correlations with low-level audio descriptors across music genres. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 37 1578–1594 10.1037/a0024323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulis E. H. (2013). On Repeat: How Music Plays the Mind. New York: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Marsh K. L., Richardson M. J., Schmidt R. C. (2009). Social connection through joint action and interpersonal coordination. Top. Cogn. Sci. 1 320–339 10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01022.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel F. L., Nevison C. M., Rayment D., Simpson M. J., Keverne E. B. (1993). Opioid receptor blockade reduces maternal affect and social grooming in rheses monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology 18 307–321 10.1016/0306-4530(93)90027-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel F. L., Nevison C. M., Simpson M. J., Keverne E. B. (1995). Effects of opioid receptor blockade on the social behavior of rhesus monkeys living in large family groups. Dev. Psychobiol. 28 71–84 10.1002/dev.420280202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes H. W. D., Maldonado R., Simonin F., Valverde O., Slowe S., Kitchen I., et al. (1996). Loss of morphine-induced analgesia, reward effect and withdrawal symptoms in mice lacking the mu-opioid-receptor gene. Nature 383 819–823 10.1038/383819a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott J. (2008). The evolution of music. Nature 453 287–288 10.1038/453287a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney C. H., Antoni M. H., Kumar M., Rims F. C., McCabe P. M. (1997a). Effects of guided imagery and music (GIM) therapy on mood and cortisol in healthy adults. Health Psychol. 16 390–400 10.1037/0278-6133.16.4.390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney C. H., Tims F. C., Kumar A. M., Kumar M. (1997b). The effect of selected classical music and spontaneous imagery on plasma beta-endorphin. J. Behav. Med. 20 85–99 10.1023/A:1025543330939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill W. H. (1995). Keeping Together in Time. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- Menon V., Levitin D. J. (2005). The rewards of music listening: response and physiological connectivity of the mesolimbic system. Neuroimage 28 175–184 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.05.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merker B. (2000). “Synchronous chorusing and human origins,” in The Origins of Music eds Wallin N., Merker B. H., Brown S. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; ) 315–327 [Google Scholar]

- Merker B., Madison G. S., Eckerdal P. (2009). On the role and origin of isochrony in human rhythmic entrainment. Cortex 45 4–17 10.1016/j.cortex.2008.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A., Domes G., Kirsch P., Heinrichs M. (2011). Oxytocin and vasopressin in the human brain: social neuropeptides for translational medicine. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 524–538 10.1038/nrn3044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles L. K., Griffiths J. L., Richardson M. J., Macrae C. N. (2010). Too late to coordinate: contextual influences on behavioral synchrony. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 40 52–60 10.1002/ejsp.721 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miles L. K., Lumsden J., Richardson M. J., Neil Macrae C. (2011). Do birds of a feather move together? Group membership and behavioral synchrony. Exp. Brain Res. 211 495–503 10.1007/s00221-011-2641-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles L. K., Nind L. K., Macrae C. N. (2009). The rhythm of rapport: interpersonal synchrony and social perception. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 45 585–589 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. F. (2000). The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of the Human Nature. New York, NY: Random House Inc [Google Scholar]

- Moles A., Kieffer B. L., D’Amato F. R. (2004). Deficit in attachment behavior in mice lacking the mu-opioid receptor gene. Science 304 1983–1986 10.1126/science.1095943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller C., Klega A., Buchholz H.-G., Rolke R., Magerl W., Schirrmacher R., et al. (2010). Basal opioid receptor binding is associated with differences in sensory perception in healthy human subjects: a [18F]diprenorphine PET study. Neuroimage 49 731–737 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller F., Agamanolis S., Picard R. (2003). “Exertion interfaces: sports over a distance for social bonding and fun,” in Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Lauderdale, FL [Google Scholar]

- Nettl B. (1983). The Study of Ethnomusicology: Twenty-Nine Issues and Concepts. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press [Google Scholar]

- Nettl B. (2000). “An ethnomusicologist contemplates universals in musical sound and musical culture,” in The Origins of Music, eds Wallin N. L., Merker B., Brown S. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; ) 463–472 [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson U. (2008). Effects of music interventions: a systematic review. AORN J. 87 780–807 10.1016/j.aorn.2007.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson U., Rawal N., Enqvist B., Unosson M. (2003). Analgesia following music and therapeutic suggestions in the PACU in ambulatory surgery; a randomized controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 47 278–283 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson U., Rawal N., Uneståhl L. E., Zetterberg C., Unosson M. (2001). Improved recovery after music and therapeutic suggestions during general anaesthesia: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 45 812–817 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.045007812.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead M. C., Franklin K. B. (1997). The development of a conditioned place preference to morphine: effects of lesions of various CNS sites. Behav. Neurosci. 111 1313–1323 10.1037/0735-7044.111.6.1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oullier O., De Guzman G. C., Jantzen K. J., Lagarde J., Kelso J. A S. (2008). Social coordination dynamics: measuring human bonding. Soc. Neurosci. 3 178–192 10.1080/17470910701563392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oullier O., Jantzen K. J., Steinberg F. L., Kelso J. A S. (2005). Neural substrates of real and imagined sensorimotor coordination. Cereb. Cortex 15 975–985 10.1093/cercor/bhh198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overy K., Molnar-Szakacs I. (2009). Being together in time: musical experience and the mirror neuron system. Music Percept. 26 489–504 10.1525/mp.2009.26.5.489 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J. (1995). The emotional sources of “chills” induced by music. Music Percept. Interdiscip. J. 13 171–207 10.2307/40285693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J., Herman B. H., Vilberg T., Bishop P., De Eskinazi F. G. (1980). Endogenous opioids and social behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 4 473–487 10.1016/0149-7634(80)90036-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters D. (2010). Enactment in listening: intermedial dance in EGM sonic scenarios and the bodily grounding of the listening experience. Perform. Res. 15:3 10.1080/13528165.2010.527211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinker S. (1997). How the Mind Works. New York: Norton; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragen B. J., Maninger N., Mendoza S. P., Jarcho M. R., Bales K. L. (2013). Presence of a pair-mate regulates the behavioral and physiological effects of opioid manipulation in the monogamous titi monkey (Callicebus cupreus). Psychoneuroendocrinology 38 2448–2461 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddish P., Fischer R., Bulbulia J. (2013). Let’s dance together: synchrony, shared intentionality and cooperation. PLoS ONE 8:e71182 10.1371/journal.pone.0071182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy V. (2003). On being the object of attention: implications for self-other consciousness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 7 397–402 10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00191-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resendez S. L., Dome M., Gormley G., Franco D., Nevárez N., Hamid A. A., et al. (2013). μ-Opioid receptors within subregions of the striatum mediate pair bond formation through parallel yet distinct reward mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 33 9140–9149 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4123-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G. (2005). The mirror neuron system and its function in humans. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 210 419–421 10.1007/s00429-005-0039-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G., Fadiga L., Gallese V., Fogassi L. (1996). Premotor cortex and the recognition of motor actions. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 3 131–141 10.1016/0926-6410(95)00038-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roederer J. G. (1984). The search for a survival value of music. Music Percept. 1 350–356 10.2307/40285265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salimpoor V. N., Benovoy M., Larcher K., Dagher A., Zatorre R. J. (2011). Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nat. Neurosci. 14 257–262 10.1038/nn.2726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaskan E., Ehrhardt R., Schulz A., Walter M., Schächinger H. (2008). Post-learning intranasal oxytocin modulates human memory for facial identity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33 368–374 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schino G., Troisi A. (1992). Opiate receptor blockade in juvenile macaques: effect on affiliative interactions with their mothers and group companions. Brain Res. 576 125–130 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90617-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebanz N., Bekkering H., Knoblich G. (2006). Joint action: bodies and minds moving together. Trends Cogn. Sci. 10 70–76 10.1016/j.tics.2005.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers B., Polansky L., Casey M., Wheatley T. (2013). Music and movement share a dynamic structure that supports universal expressions of emotion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 70–75 10.1073/pnas.1209023110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville J. A., Decety J. (2006). Weaving the fabric of social interaction: articulating developmental psychology and cognitive neuroscience in the domain of motor cognition. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 13 179–200 10.3758/BF03193831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano G. B., Zhu W., Cadet P., Salamon E., Mantione K. J. (2004). Music alters constitutively expressed opiate and cytokine processes in listeners. Med. Sci. Monit. 10 MS18–MS27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stel M., Blascovich J., Mccall C., Mastop J., Van baaren R. B., Vonk R. (2010). Mimicking disliked others: effects of a priori liking on the mimicry-liking link. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 40 867–880 10.1002/ejsp.655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P., Rickers K. (2013). The effect of behavioral synchrony in groups of teammates and strangers. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 11 286–291 10.1080/1612197X.2013.750139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P. J., Rickers K., Gammage K. L. (2014). The effect of different phases of synchrony on pain threshold. Gr. Dyn. 18 122–128 10.1037/gdn0000001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer R. E., Newman J. R., Mcclain T. M. (1994). Self-regulation self-regulation of mood: strategies for changing a bad mood, raising energy, and reducing tension search. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 64 910–925 10.1037/0022-3514.67.5.910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tognoli E., Lagarde J., De Guzman G. C., Kelso J. A S. (2007). The phi complex as a neuromarker of human social coordination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 8190–8195 10.1073/pnas.0611453104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M., Carpenter M., Call J., Behne T., Moll H. (2005). Understanding and sharing intentions: the origins of cultural cognition. Behav. Brain Sci. 28 675–691; discussion 691–735 10.1017/S0140525X05000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trigo J. M., Martin-García E., Berrendero F., Robledo P., Maldonado R. (2010). The endogenous opioid system: a common substrate in drug addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 108 183–194 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdesolo P., Desteno D. (2011). Synchrony and the social tuning of compassion. Emotion 11 262–266 10.1037/a0021302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Baaren R. B., Holland R. W., Kawakami K., Van Knippenberg A. (2004). Mimicry and prosocial behavior. Psychol. Sci. 15 71–74 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01501012.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ree J. M., Niesink R. J., Van Wolfswinkel L., Ramsey N. F., Kornet M. M., Van Furth W. R., et al. (2000). Endogenous opioids and reward. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 405 89–101 10.1016/S0014-2999(00)00544-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ulzen N. R., Lamoth C. J. C., Daffertshofer A., Semin G. R., Beek P. J. (2008). Characteristics of instructed and uninstructed interpersonal coordination while walking side-by-side. Neurosci. Lett. 432 88–93 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.11.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltermuth S. S. (2012). Synchronous activity boosts compliance with requests to aggress. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48 453–456 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.10.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltermuth S. S., Heath C. (2009). Synchrony and cooperation. Psychol. Sci. 20 1–5 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zak P. J., Kurzban R., Matzner W. T. (2005). Oxytocin is associated with human trustworthiness. Horm. Behav. 48 522–527 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zak P. J., Stanton A. A., Ahmadi S. (2007). Oxytocin increases generosity in humans. PLoS ONE 2:e1128 10.1371/journal.pone.0001128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zillmann D., Rockwell S., Schweitzer K., Sundar S. S. (1993). Does humor facilitate coping with physical discomfort? Motiv. Emot. 17 1–21 10.1007/BF00995204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta J.-K., Ketter T. A., Bueller J. A., Xu Y., Kilbourn M. R., Young E. A., et al. (2003). Regulation of human affective responses by anterior cingulate and limbic mu-opioid neurotransmission. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60 1145–1153 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta J. K., Smith Y. R., Bueller J. A., Xu Y., Kilbourn M. R., Jewett D. M., et al. (2001). Regional mu opioid receptor regulation of sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Science 293 311–315 10.1126/science.1060952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]