Abstract

Several previous studies have raised controversy over the functional role of neuroglobin (Ngb) in the retina. Certain studies indicate a significant impact of Ngb on retinal physiology, whereas others are conflicting. The present is an observational study that tested the effect of Ngb deficiency on gene expression in dark- and light-adapted mouse retinas. Large-scale gene expression profiling was performed using GeneChip® Mouse Exon 1.0 ST arrays and the results were compared to publicly available data sets. The lack of Ngb was found to have a minor effect on the light-induced retinal gene expression response. In addition, there was no increase in the expression of marker genes associated with hypoxia, endoplasmic reticulum-stress and oxidative stress in the Ngb-deficient retina. By contrast, several genes were identified that appeared to be differentially expressed between the genotypes when the effect of light was ignored. The present study indicates that Ngb deficiency does not lead to major alternations in light-dependent gene expression response, but leads to subtle systemic differences of a currently unknown functional significance.

Keywords: neuroglobin, retina, microarray, knockout, gene expression

Introduction

The retina is one of the most metabolically active tissues (1,2). The oxygen consumption rate in the dark-adapted retina is considerably higher compared to the light-adapted condition (3,4). Empirical evidence indicates that in part, oxygen tension in the retina can fall close to 0 mm Hg making these sections hypoxic (3,4). Unlike the muscles in which a high concentration of myoglobin secures an oxygen reservoir, the retina was believed to depend solely on oxygen diffusion from the choroid. In 2000, a third member of the hemoglobin family was discovered and shown to be expressed in the mouse brain (5). Due to the neuronal expression, the globin was named neuroglobin (Ngb). Ngb is a monomeric hemoglobin capable of reversibly binding oxygen in vitro (5,6). Ngb was highly expressed in the majority of layers in the mouse retina, including the photoreceptors (7). The high concentration of Ngb was thought to indicate a role in the retinal oxygen supply. Another study showed an overlap between Ngb expression and areas with the highest number of mitochondria supporting a respiratory function of Ngb (8). Previously, several studies have implicated a neuroprotective function of Ngb in retinal diseases (9–12). Furthermore, transgenic mice overexpressing Ngb were found to be resistant to retinal ischemia (13) and in vivo knockdown of Ngb using small interfering RNA (siRNA) induced the degradation of retina ganglion cells and behavioral effects associated with compromised visual performance (14). In contrast to these studies, we recently showed limited Ngb immunoreactivity in the retina and no effect of Ngb deficiency on neuronal survival using genetically Ngb-deficient (Ngb-null) mice (15). This is in line with studies showing no adverse effect of Ngb deficiency on neuronal survival in the brain of mice exposed to hypoxia or ischemia (16,17). Therefore, the function of Ngb in the retina and brain remains unresolved. In the present study, microarrays were used to investigate the effect of Ngb deficiency on retinal gene expression. The affect of Ngb deficiency on retinal gene expression response to light was investigated, as well as whether there was differential expression of marker genes associated with oxygen availability, oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-stress in Ngb-deficient retina.

Materials and methods

Ngb-null mice

The Ngb-null mouse model was created by GenOway (Lyon, France) as described previously (17,18).

Animals

A total of 15 wild-type (wt) c57BL6 and 15 Ngb-null female mice (12–16 weeks old) were used in the experiment. The animals were maintained in a 12/12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Five mice of each genotype were euthanized by decapitation either in darkness (t0) or after exposure to 1.5 or 5 h of light. The retinas were rapidly dissected out on ice, snap-frozen on dry-ice and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. Animal care and all experimental procedures were conducted in accordance to the principles of Laboratory Animal Care (Law on Animal Experiments in Denmark, publication 1306, November 23, 2007) and approved by the Faculty of Health, University of Copenhagen (Copenhagen, Denmark).

Microarray analysis

RNA was extracted using the InviTrap Spin Universal RNA mini kit (STRATEC Molecular GmbH, Berlin, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, homogenized retinas were transferred to the lysis buffer for inactivation of RNases. After 2 min centrifugation at 12,851 × g the supernatant was transferred to a new tube containing 96% pure ethanol and mixed. The mixture was subsequently applied to a spin filter tube and centrifuged for 2 min at 12,851 × g and the flow through was discarded. The filter tube was washed with wash buffer solution followed by centrifugation and RNA was eluted with elution buffer. Eluted RNA was stored at −80°C until use. The gene expression profiling was performed with GeneChip® Mouse Exon 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 50 ng total RNA from each sample was amplified using the Ovation Pico WTA system V2 (NuGEN Technologies, Inc., San Carlos, CA, USA). Fragmentation and biotin labeling was performed using the Encore-Ovation cDNA Biotin Module (NuGEN Technologies). The labeled samples were hybridized to the GeneChip® Mouse Exon 1.0 ST array (Affymetrix). The arrays were washed and stained with phycoerytrin-conjugated streptavidin using the Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450 and the arrays were scanned in the Affymetrix GeneArray® 3000 scanner to generate fluorescent images, as described in the Affymetrix GeneChip® instructions. The cell-intensity files were generated in the GeneChip® Command Console software (Affymetrix).

Differential expression analysis

Differential gene expression analysis was performed with DEMI (in-house designed software) (19) as implemented in the R package (www.r-project.org; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/demi. Accessed September 5, 2014). Gene expression data from Bedolla and Torre (20) (GEO: GSE29299) and Porterfield et al (21) (GEO: GSE6904) was downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus. A gene was termed differentially expressed when the corresponding false discovery rate (FDR) was <0.01 and the ratio of differentially expressed on-target probes was >0.5 (i.e. >50% of the gene-specific probes were differentially expressed in the same direction). Gene set enrichment analysis was performed separately for differentially up and downregulated genes using g:Profiler (http://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/. Accessed September 5, 2014) (22).

Estimating overlap between the different microarray experiments

The overlap of the differentially expressed genes between the different experiments was estimated with Fisher’s exact test in R. P-values were corrected using the FDR procedure (23) and enrichments with FDR<0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. In order to compare differentially expressed genes between mouse and rat datasets, an annotation table was retrieved that linked rat gene identifiers to mouse orthologs from Ensembl (release 75) using R (package biomaRt).

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

First strand cDNA was synthesized with random hexamers (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) and SuperScript® III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies) from 500 ng total RNA. RT-qPCR was performed using TaqMan® (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) gene expression assays (Table I). The expression of hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (Table I) was used as internal reference. PCR was performed in 4 parallel reactions for each sample. RT-qPCR reactions were run on the ABI PRISM 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system machine (Applied Biosystems) and quantified with the ABI PRISM 7900 SDS 2.2.2 software. For each assay, an average of 4 technical replicates was used as the endpoint. Expression levels were calculated using the ΔCt method (24), where the Ct of the gene of interest is normalized to a reference gene.

Table I.

TaqMan® assays used for reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction gene expression validation.

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Assay identity or sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Hif1α | Hypoxia inducible factor 1α | Mm00468879_g |

| Bnip3 | BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3 | Mm01275601_g |

| Gstz1 | Glutatione S-transferase | Mm01296880_m1 |

| Gsr | Glutatione reductase | Mm00439154_m1 |

| Xbp1 | X-box binding protein 1 | Mm00457357_m1 |

| Nfe2l2 (Nrf2) | Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 | Mm00477784_m1 |

| Egr1 | Early growth response protein 1 | Mm00656724_m1 |

| Fos | FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene | Mm00487425_m1 |

| Akap6 | A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 6 | Mm01292745_m1 |

| Atp8a2 | ATPase, aminophospholipid transporter, class I, type 8A, member 2 | Mm00443740_m1 |

| Entpd4 | Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 4 | Mm00491888_m1 |

| Hprt1 | Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 | F 5′-GCAGTACAGCCCCAAAATGG-3′, R 5′-AACAAA GTCTGGCCTGTATCCAA-3′, probe (VIC) 5′-VIC-AAGCTTGCTGGTGAAAAGGACCTCTCG-3′ |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Results

Gene expression analysis in dark- and light-adapted mouse retinas

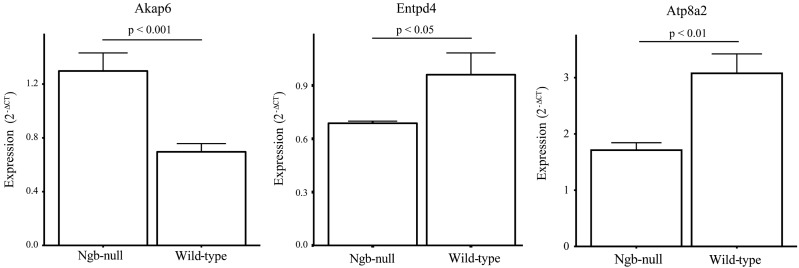

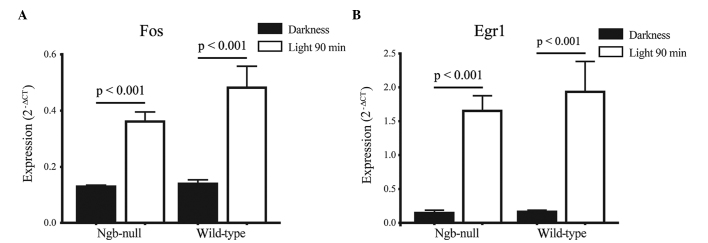

Transcriptome-wide gene expression analysis was performed using retinas of dark- and light-adapted (1.5 and 5 h) Ngb-null mice and their wt littermates. The differences in expression were studied using DEMI, a recently published non-parametric methodology, which estimates differential expression from probe-level data (19). The effect of light on gene expression was more substantial than the effect of genotype, as reflected in the numbers of differentially expressed genes (Table II). Differential expression of Fos and Egr1, which are established light-responsive genes (25), was confirmed by RT-qPCR in the genotypes after 1.5 h light pulse (Fig. 1). To further confirm that the effect of light was similar to the expected effect, the data from two previously published studies were reanalyzed, which made raw expression data publicly available. In the first study, ex vivo retinas collected from adult Long Evans rats, were exposed to light (1000 lux for 3 or 6 h) or remained in the dark as a control (20). The second study collected expression data from mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the main target of retinohypothalamic tract, after 0.5-h light pulse and a sham-light pulse (21). A statistically significant overlap of differentially expressed genes between the studies was believed to cross-validate results obtained under the distinct experimental setups. As expected, there was a significant overlap of differentially expressed genes between the corresponding treatments in the present study and the two independent datasets (Table III). Specifically, there was a significant overlap between the upregulated genes in the mouse retina after 1.5-h light pulse and in the mouse SCN after 0.5-h light pulse. In addition, there was a significant overlap between the upregulated genes in the mouse retina after 5-h light pulse and rat retina exposed to 6-h light pulse ex vivo. A significant overlap between the downregulated genes was not observed in the corresponding treatments from the different experiments, indicating that the light-specific response is mostly associated with upregulation of gene expression. No significant overlap was found between the corresponding treatments when the gene sets of opposite differential expression direction were compared, serving as a negative control. As the pattern of gene set enrichment FDR values was similar, irrespective of the genotype, it was concluded that the gene expression response to light is largely intact in Ngb-deficient retina.

Table II.

Counts of differentially expressed genes in the retina (false discovery rate <0.01).

| Differential expressiona | Ngb-deficient arraysb | Wild-type arraysb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Variables | Up | Down | Up | Down | Up | Down |

| Light pulse, h | ||||||

| 0 | 7 | 6 | - | - | - | - |

| 1.5 | 23 | 27 | 5 | 36 | 28 | 11 |

| 5 | 9 | 11 | 21 | 29 | 323 | 283 |

No. of differentially expressed genes in neuroglobin (Ngb)-deficient retina in reference to wild-types;

no. of differentially expressed genes after light pulse. Differential expression was estimated in regards to the dark-adapted retina of the same genotype.

Figure 1.

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction verification of light-inducible genes. Gene expression in the retina of neuroglobin (Ngb)-deficient (Ngb-null) and wild-type (wt) mice after a 1.5-h light stimulation. There was a significant induction (P<0.05, t-test) of (A) Fos and (B) Egr1 in the Ngb-null and wt mice when compared to the dark-adapted controls. No differential expression was detected between wt and Ngb-null mice. Expression was normalized to hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 as the internal reference (n=5 in each group).

Table III.

Similarity of the gene expression responses in the present study and associated datasets.

| Present Ngb-null and wild-type pooled | Present Ngb-null | Present wild-type | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| 1.5 h | 5 h | 1.5 h | 5 h | 1.5 h | 5 h | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Light pulse, h | Diff. expression | Up | Down | Up | Down | Up | Down | Up | Down | Up | Down | Up | Down | |

| Mouse SCN | ||||||||||||||

| (Bedolla et al 2011) | 0.5 | Up | 1.84e-04a | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 1.14e-04a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.02e-05a | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Down | 1 | 1 | 0.49 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.85 | 1 | ||

| Rat retina | ||||||||||||||

| (Porterfield et al 2007) | 3 | Up | 1 | 1 | 0.49 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 | 1 |

| Down | 1 | 0.77 | 1 | 0.49 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.85 | ||

| 6 | Up | 0.83 | 1 | 7.42e-07a | 1 | 0.18 | 1 | 1.14e-04a | 1 | 0.85 | 1 | 2.02e-05a | 1 | |

| Down | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.82 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.68 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

Significant overlap of differentially (diff.) expressed genes between the studies (FDR<0.001, hypergeometric probability distribution). The table lists FDR-values for the enrichment of differentially expressed genes between the present study and selected public data. In order to reveal genotype-dependent effects in the present study, differential expression in light-exposed vs. dark-adapted retina was estimated in 3 different subsets of the arrays.

Ngb, neuroglobin; Ngb-null, Ngb-deficient; FDR, false discovery rate.

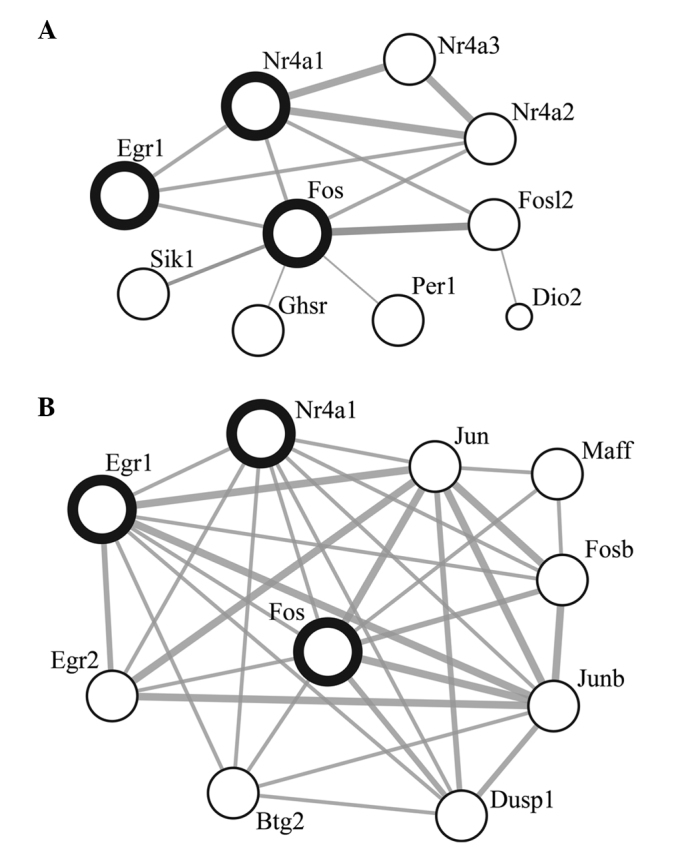

Exposure to 1.5-h light pulse revealed three gene ontology categories with weakly significant enrichment. The set of upregulated genes included several early response genes, such as Egr1, Fos, Fosl2, Per1 and Nr4a1-3, indicating effectiveness of the light pulse (Fig. 2). Of these, Nr41a, Per1, Fos, Fosl2 and Nr4a2 have also been confirmed in the study by Araki et al (25), as light inducible transcripts in the SCN, which is a light responsive brain area directly innervated by the eye. Similarly, the reanalysis of data from the study by Porterfield et al (21) indicated the upregulation of Nr4a1, Egr1 and Fos in SCN after 0.5-h light pulse. Functional annotation analysis of genes upregulated in response to 5-h light pulse revealed numerous significantly enriched categories associated with translation, RNA-splicing and visual perception. Gene ontology categories enriched among downregulated genes were mostly correlated with the term ‘G-protein coupled receptor activity’. Closer inspection of the downregulated gene set revealed a high proportion of olfactory and vomeronasal receptor genes, which were dismissed as uninformative and therefore, not deserving further investigation. In our previous studies, we have observed similar, and most likely nonspecific, induction of the olfactory and vomeronasal receptor genes in the brain in response to various stimuli (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Known and predicted protein interactions between light-induced genes in the retina and the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). The circles depict the genes that were upregulated in response to light. Connecting lines indicate protein interaction information as retrieved from STRING (40). (A) Genes induced by 1.5-h light pulse (neuroglobin-deficient and wild-type arrays were pooled). (B) Genes induced in the mouse SCN by 0.5-h light pulse, data published by (21). Thicker or thinner lines show more or less evidence of interactions between the proteins, respectively. The genes overlapping in the datasets are presented with accentuated circles.

Despite the overall similarity of light-induced gene expression responses between Ngb-null mice and wt, the present study aimed to investigate whether there are systemic genotype-related differences in the retina. Specifically, the aim was to identify the genes that are differentially expressed when the effect of light is ignored. Samples with identical genotypes (n=15) were pooled and it was found that there were several differentially expressed genes between the pools (Table IV). The three main differential expression estimates from the array study were confirmed by RT-qPCR (Fig. 3).

Table IV.

Differences in the retinal gene expression between neuroglobin (Ngb)-deficient and wild-type mice when light exposure is ignored.

| Direction | FDR | Gene symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up | 1.10e-23 | Akap6 | A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 6 |

| Up | 6.76e-22 | Tmem229b | Transmembrane protein 229B |

| Up | 2.60e-22 | Serpina3n | Serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 3N |

| Up | 1.28e-13 | Gdpd3 | Glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase domain containing 3 |

| Up | 1.28e-13 | Ccdc115 | Coiled-coil domain containing 115 |

| Down | 7.56e-36 | Entpd4 | Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 4 |

| Down | 2.39e-31 | Atp8a2 | ATPase, aminophospholipid transporter-like, class I, type 8A, member 2 |

| Down | 5.10e-18 | Snapc1 | Small nuclear RNA activating complex, polypeptide 1 |

| Down | 2.20e-16 | Heatr5a | HEAT repeat containing 5A |

| Down | 2.37e-13 | Lcmt2 | Leucine carboxyl methyltransferase 2 |

Five most significant differentially upregulated and downregulated genes between Ngb-deficient and wild-type arrays. FDR, false discovery rate.

Figure 3.

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction verification of the differentially expressed genes between Ngb-null and wild-type mice. Expression was normalized to hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (Htpr1) as the internal reference (n=9–10 in each group). Differential expression significance was estimated with one-tailed t-test to confirm the direction of expression dynamics reported by the microarray.

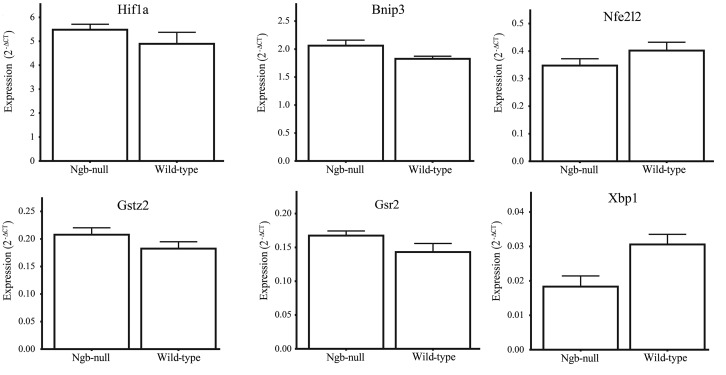

Several studies have indicating a role of Ngb in scavenging reactive oxygen species. A recent study showed that Ngb regulates Hif1α and Nrf2 (Nfe2l2) expression and antioxidant levels in cells exposed to hypoxia (26). Therefore, the following genes were chosen for differential expression analysis using RT-qPCR in the dark-adapted retina: Hif1α, the Hif1α target gene Bnip3 (27), the glutathione system genes Gsr and Gstz1, the master regulator of oxidative stress responsive genes Nfe2l2 (28) and the unfolded protein response regulator Xbp1 (29). None of the genes exhibited evidence of differential expression between the genotypes, indicating that there was no apparent elevation of ER-stress, oxidative stress or hypoxia response in the Ngb-null retina (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction of hypoxia (Hif1α, Bnip3), oxidative stress (Nfe2l2, Gstz2, Gsr2) and unfolded protein response (Xbp1) marker genes in dark-adapted retina. No differential expression was detected between the genotypes (t-test). Expression was normalized to hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 as the internal reference (n=4–5 in each group). Ngb, neuroglobin; Ngb-null, Ngb-deficient.

Discussion

A number of studies have reported high levels of Ngb in the retina and adverse effects of Ngb knockdown on neuronal survival, leading the hypothesis that Ngb is important for retinal oxygen homeostasis and neuronal survival (7–14,30–32). Recently, Chan et al (13) found that transgenic overexpression of Ngb conferred protection against retinal ischemia via a decrease in oxidative stress levels. Similarly, Lechauve et al (14) showed that siRNA knockdown of Ngb reduced mitochondrial activity, induced cell death and had an adverse effect on visual performance. In the present study, genome-wide transcriptional profiling was used to study the effect of Ngb deficiency on gene expression in the eye under various light conditions. Based on a number of studies indicating an involvement of Ngb in retinal respiration, it was thought that Ngb-null retina would exhibit an altered expression of genes associated with hypoxic and oxidative stress response. Furthermore, an effect for whether Ngb deficiency on gene expression response to light is required for normal retinal function was expected.

In the present study, functional annotation of differentially expressed genes in the dark-adapted retina showed no evidence for the enrichment of the gene sets associated with oxidative metabolism or cellular stress. Similarly, RT-qPCR analysis of the marker genes for hypoxia, oxidative stress and ER-stress did not indicate differential expression between the genotypes. These results suggest that Ngb deficiency does not lead to an altered light response or expressional changes indicative of cellular stress. In addition, these results are in line with our previous study, suggesting low and limited expression of Ngb in the retina (15), as well as with the study by Fago et al (33) that suggested the low O2 affinity of Ngb appears to be incompatible with a physiological role in mitochondrial O2 supply at the low O2 tensions. The current results are also supported by the apparently normal circadian rhythm and the induction of light-responsive genes in the SCN of Ngb-null mice (18).

The study of systemic gene expression differences when the effect of light was ignored revealed several differentially expressed genes between Ngb-null mice and wt. The three genes showing the most significant differential expression were Akap6, Entpd4 and Atp8a2. The only gene of the three that was upregulated, Akap6, lies within 35 Mbp from the Ngb locus and its differential expression may be due to the congenic footprint (34). Entpd4 is responsible for cleaving nucleotide tri- and diphosphates and is believed to be involved in the rescue of nucleotides from the lysosomal/autophagic vacuole lumen (35). To the best of our knowledge, we are not aware of any previous studies indicating a functional coupling between Ngb and Entpd4. Atp8a2 is highly expressed in testes, spinal cord, brain and retina (36–38) and is an adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent lipid flippase that translocates aminophospholipids from the exoplasmic to cytoplasmic leaflets of membranes (39). A straightforward functional association between Atp8a2 and Ngb is unclear as the former is essential for the correct functioning of photoreceptor cells (39), which do not appear to express Ngb (15). As Atp8a2 consumes a notable amount of cellular ATP in the photoreceptor cells (37), it could be hypothesized that if Ngb is involved in oxygen delivery in the retina then a lack of Ngb may lead to a reduced capacity for oxidative phosphorylation resulting in a lower rate for Atp8a2 expression. Of note, Atp8a2 deficiency leads to the decline in visual perception and auditory failure (39).

In conclusion, the present study indicates that Ngb deficiency does not lead to major alternations in light-dependent gene expression response, but leads to subtle systemic differences of currently unknown functional significance. Further studies are required to ascertain whether Atp8a2 and Entpd4 are functionally coupled to Ngb.

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by the Lundbeck Foundation (grant no. R44-A4267), the NOVO-Nordisk Foundation, the Foundation for Providing Medical Research, the Hartmann Foundation, the Estonian Ministry of Science and Education (grant nos. SF0180125s08 and GARFS0120P), the Estonian Science Foundation (grant no. PUT120) and the European Regional Development Fund. H.L. was supported by the Estonian Science Foundation (grant no. ETF9099). S.I. was supported by the European Social Fund’s Doctoral Studies Internationalization Program DoRa, carried out by Archimedes. The authors are most grateful to Professors Eero Vasar and Jan Fahrenkrug for providing excellent working facilities.

References

- 1.Anderson B, Jr, Saltzman HA. Retinal oxygen utilization measured by hyperbaric blackout. Arch Ophthalmol. 1964;72:792–795. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1964.00970020794009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ames A., III Energy requirements of CNS cells as related to their function and to their vulnerability to ischemia: a commentary based on studies on retina. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992;70(Suppl):S158–S164. doi: 10.1139/y92-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed J, Braun RD, Dunn R, Jr, Linsenmeier RA. Oxygen distribution in the macaque retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:516–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linsenmeier RA. Effects of light and darkness on oxygen distribution and consumption in the cat retina. J Gen Physiol. 1986;88:521–542. doi: 10.1085/jgp.88.4.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burmester T, Weich B, Reinhardt S, Hankeln T. A vertebrate globin expressed in the brain. Nature. 2000;407:520–523. doi: 10.1038/35035093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewilde S, Kiger L, Burmester T, et al. Biochemical characterization and ligand binding properties of neuroglobin, a novel member of the globin family. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38949–38955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt M, Giessl A, Laufs T, Hankeln T, Wolfrum U, Burmester T. How does the eye breathe? Evidence for neuroglobin-mediated oxygen supply in the mammalian retina. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1932–1935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bentmann A, Schmidt M, Reuss S, Wolfrum U, Hankeln T, Burmester T. Divergent distribution in vascular and avascular mammalian retinae links neuroglobin to cellular respiration. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20660–20665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501338200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei X, Yu Z, Cho KS, et al. Neuroglobin is an endogenous neuroprotectant for retinal ganglion cells against glaucomatous damage. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2788–2797. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi SY, Feng XM, Li Y, Li X, Chen XL. Expression of neuroglobin in ocular hypertension induced acute hypoxic-ischemic retinal injury in rats. Int J Ophthalmol. 2011;4:393–395. doi: 10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2011.04.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lechauve C, Rezaei H, Celier C, et al. Neuroglobin and prion cellular localization: investigation of a potential interaction. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:968–977. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajendram R, Rao NA. Neuroglobin in normal retina and retina from eyes with advanced glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:663–666. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.093930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan AS, Saraswathy S, Rehak M, Ueki M, Rao NA. Neuroglobin protection in retinal ischemia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:704–711. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lechauve C, Augustin S, Cwerman-Thibault H, et al. Neuroglobin involvement in respiratory chain function and retinal ganglion cell integrity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 18232012:2261–2273. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hundahl CA, Fahrenkrug J, Luuk H, Hay-Schmidt A, Hannibal J. Restricted expression of neuroglobin in the mouse retina and co-localization with melanopsin and tyrosine hydroxylase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;425:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raida Z, Hundahl CA, Kelsen J, Nyengaard JR, Hay-Schmidt A. Reduced infarct size in neuroglobin-null mice after experimental stroke in vivo. Exp Transl Stroke Med. 2012;4:15. doi: 10.1186/2040-7378-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hundahl CA, Luuk H, Ilmjarv S, et al. Neuroglobin-deficiency exacerbates Hif1A and c-FOS response, but does not affect neuronal survival during severe hypoxia in vivo. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hundahl CA, Fahrenkrug J, Hay-Schmidt A, Georg B, Faltoft B, Hannibal J. Circadian behaviour in neuroglobin deficient mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilmjarv S, Hundahl CA, Reimets R, et al. Estimating differential expression from multiple indicators. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e72. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bedolla DE, Torre V. A component of retinal light adaptation mediated by the thyroid hormone cascade. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porterfield VM, Piontkivska H, Mintz EM. Identification of novel light-induced genes in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. BMC Neurosci. 2007;8:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-8-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reimand J, Arak T, Vilo J. g:Profiler - a web server for functional interpretation of gene lists (2011 update) Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W307–W315. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Araki R, Nakahara M, Fukumura R, et al. Identification of genes that express in response to light exposure and express rhythmically in a circadian manner in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res. 2006;1098:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hota KB, Hota SK, Srivastava RB, Singh SB. Neuroglobin regulates hypoxic response of neuronal cells through Hif-1α- and Nrf2-mediated mechanism. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1046–1060. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendez O, Zavadil J, Esencay M, et al. Knock down of HIF-1alpha in glioma cells reduces migration in vitro and invasion in vivo and impairs their ability to form tumor spheres. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:133. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linker RA, Lee DH, Ryan S, et al. Fumaric acid esters exert neuroprotective effects in neuroinflammation via activation of the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway. Brain. 2011;134:678–692. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwakoshi NN, Lee AH, Vallabhajosyula P, Otipoby KL, Rajewsky K, Glimcher LH. Plasma cell differentiation and the unfolded protein response intersect at the transcription factor XBP-1. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:321–329. doi: 10.1038/ni907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostojic J, Grozdanic SD, Syed NA, et al. Patterns of distribution of oxygen-binding globins, neuroglobin and cytoglobin in human retina. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1530–1536. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.11.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostojic J, Sakaguchi DS, de Lathouder Y, et al. Neuroglobin and cytoglobin: oxygen-binding proteins in retinal neurons. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1016–1023. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidt M, Laufs T, Reuss S, Hankeln T, Burmester T. Divergent distribution of cytoglobin and neuroglobin in the murine eye. Neurosci Lett. 2005;374:207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fago A, Hundahl C, Malte H, Weber RE. Functional properties of neuroglobin and cytoglobin. Insights into the ancestral physiological roles of globins. IUBMB Life. 2004;56:689–696. doi: 10.1080/15216540500037299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schalkwyk LC, Fernandes C, Nash MW, Kurrikoff K, Vasar E, Koks S. Interpretation of knockout experiments: the congenic footprint. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:299–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biederbick A, Rose S, Elsasser HP. A human intracellular apyrase-like protein, LALP70, localizes to lysosomal/autophagic vacuoles. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2473–2484. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.15.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cacciagli P, Haddad MR, Mignon-Ravix C, et al. Disruption of the ATP8A2 gene in a patient with a t(10;13) de novo balanced translocation and a severe neurological phenotype. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:1360–1363. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coleman JA, Kwok MC, Molday RS. Localization, purification, and functional reconstitution of the P4-ATPase Atp8a2, a phosphatidylserine flippase in photoreceptor disc membranes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32670–32679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu X, Libby RT, de Vries WN, et al. Mutations in a P-type ATPase gene cause axonal degeneration. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coleman JA, Zhu X, Djajadi HR, et al. Phospholipid flippase ATP8A2 is required for normal visual and auditory function and photoreceptor and spiral ganglion cell survival. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:1138–1149. doi: 10.1242/jcs.145052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, et al. STRING v9.1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D808–D815. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]