Abstract

Inhibitory processes are highly relevant to behavioral control affecting decisions made daily. The Go/NoGo task is a common task used to tap basic inhibitory processes important in higher order executive functioning. The present study assessed neural correlates of response inhibition during performance of a Go/NoGo task in which NoGo signals or tests of inhibitory control consisted of images of beer bottles. Group comparisons were conducted between 21 heavy and 20 light drinkers, ranging in age from 18 to 22. Behaviorally, overall performance assessed with d-prime was significantly better among the lighter drinkers. On a neural level, the heavy drinkers showed significantly greater activity in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, medial frontal cortex and cingulate relative to the light drinkers during the NoGo trials. These regions are implicated in reflective or control processing of information. Further, heavy drinkers showed significantly greater activity in the insula relative to light drinkers during NoGo trials, a neural region implicated in habit circuitry and tied to cue induced urges and emotional memories of physical effects of drugs. These results suggest that the heavier drinkers may have experienced increased working memory demand and control efforts to withhold a response due to poorer inhibitory control from enhanced salience of alcohol cues on the beer NoGo trials, which also engaged insula mediated effects.

Keywords: Go/NoGo task, alcohol, dorsolateral prefrontal, insula, associative processes, fMRI, habit, beer-cued NoGo trials, response inhibition

1. Introduction

Alcohol is the most widely used substance in Western society and around the world. It is widely used across most age groups, across socioeconomic status, and is the substance most frequently abused on college campuses. Eighteen to 22 year-olds exhibit some of the highest rates of alcohol use, with full-time college students being more likely to drink heavily (~14%) and to binge drink (~40%) than peers not in college full time [1]. While some youth transition out of heavy alcohol use after about age 18, other youth maintain or increase hazardous levels of use that continue into young adulthood and beyond. Frequent heavy drinkers may be especially susceptible to the consolidation of resistant alcohol habits and the possible impairment of protective executive control functions [2]. Some researchers have shown that maturational changes and associated excutive functions that regulate behavior occur in the brain until the late teens, with some lesser continued development into the early twenties; [3–5]. Certain behaviors like binge drinking or excessive alcohol use prior to relatively complete maturation may impair development in inhibitory functions [2, 5].

1.1 Inhibitory control processes

Frontal and prefrontal mediated inhibitory processes and decision-making are highly relevant to behavioral regulation [6]. Inhibitory control functions are an important, specific aspect of higher order executive control functioning [7] and can be quite protective when risks are encountered such as temptations to drink excessively at a party. Adaptive inhibitory functioning reflects the ability to actively stop a pre-potent behavioral response such as drinking in excess once the behavior has been triggered [8]. Further, such inhibitory control processes are most relevant when there is a need for inhibition of the behavioral tendency or impulse and such tendencies do not generally surface continuously but are activated primarily by antecedent cues [9]. Inhibition then becomes highly relevant in the face of cues associated with a behavior. A history of repetitive alcohol use may result in inhibitory control processes being overridden or overwhelmed by habit-related neural processes, with behavior coming more under cue control and less under executive/voluntary control [10, 11]. An imbalance of executive control and habit-based neural systems can lead to deficits in behavioral regulation that may exacerbate risk behaviors such as hazardous drinking. This imbalance can be exacerbated by urges triggered by cues, or by withdrawal from a substance, and such urges can be mediated through the insular cortex [12].

1.2 Alcohol use and Go/NoGo findings relevant to drinkers

The Go/NoGo task is one of the most common tasks used to tap basic inhibitory control (i.e., the ability to withhold a pre-potent response) that also involves decision-making processes (see, Eagle, Bari Robbins [13]). The task measures suppression of an ongoing response and has been used extensively among varied populations ranging from youth to adults [14]. Several researchers have evaluated acute effects of alcohol on behavioral control with variations of the Go/NoGo task [15]. Among adults, Go/NoGo task performance has been found to correlate with deficits in inhibitory control among abstinent alcohol dependent individuals, [16] and in young drinkers with lower working memory capacity [17]. More generally, chronic heavy alcohol use has been associated with impairments in (non-specific) executive functions, other cognitive deficits, and self-regulation [18].

Behaviorally, several studies have evaluated various drinking and substance using populations and the effects of alcohol verses non-alcohol related stimuli on inhibitory control on Go/NoGo tasks [19–21] as well as a Stop Signal task [22] with varied findings. For instance, on an adapted Go/NoGo comparing alcohol stimuli to non-alcohol stimuli, Noel et al., [20] found detoxified alcohol abusers showed response inhibition deficits relative to the control group and they made more commission errors when presented with alcohol-related stimuli. Alternatively, on a Stop Signal task, Nederkoorn et al., [22] found no significant differences between heavy and light drinkers with respect to inhibitory errors using alcohol-related stimuli. Further, on a Go/NoGo task, Rose and Duka [22] found no significant effect of alcohol stimuli on response inhibition in a study among a group of participants preloaded with alcohol and another group administered a placebo. However, response latency was slowed when alcohol-related stimuli were presented compared to non-alcohol related stimuli. On an adapted Go/NoGo task involving attentional bias and behavioral activation with the use of alcohol cues, Weafer and Filmore [23] found an increase in inhibitory errors following exposure to alcohol images relative to neutral images in beer drinking adults. Overall, it appears that among drinkers, alcohol-related cues can often have some important effects on inhibitory processes, at least as revealed in some Go/NoGo studies.

1.3 Neural correlates of the Go/NoGo task

A meta-analysis evaluating fMRI studies found that response inhibition, assessed with Go/NoGo tasks, consistently revealed frontal lobe activation; however, localization of activation varied as a function of task design (simple vs. complex) [14]. Concurrent activation in several brain regions across studies during Go/NoGo task performance included (1) frontal and prefrontal regions, namely the inferior/middle frontal cortex, rostral supplementary motor are (pre-SMA), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), premotor cortex, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; (2) regions that are part of the striatum (e.g., putamen); and (3) regions that include or are adjacent to the insula, namely the inferior parietal regions (IPC) and the right insula [14, 24–27]. Most of this activity was observed in the right hemisphere although some bilateral activity has been observed [28]. Imaging studies have shown that regional brain activity that correlates with task performance (e.g., reaction time/and or accuracy) on the Go/NoGo becomes increasingly more focal with age and ability [29]. Increased NoGo trial activation found in a meta-analysis among complex relative to simple designs across numerous studies showed engagement of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferior frontal gyrus, and pre-SMA. It is thought that this neural activity may be part of a more general cognitive control-processing network that involves both attention and working memory [28].

With respect to alcohol use, Wetherhill et al., [30] found in a longitudinal investigation of adolescents that relative to non-drinkers, those youth who transitioned into heavy drinking showed an increase in activity during NoGo trials in the pre-supplementary motor area, and parietal and temporal regions while at baseline less activity in these regions was observed [30]. In a three-wave prospective study evaluating connectivity in control and emotion-processing systems while imaging a Go/GoNo task that used alcohol images and non-alcohol-related images among 11 older adolescents transitioning into college, Beltz et al., [31] found the greatest differences in a cognitive control network (i.e., bilateral DLPFC, right ACC and dorsal ACC) during the first semester transition into college (wave 2 of the study). As participants’ self-reported exposure to alcohol and consequences of alcohol use increased during the first semester in college, greater connectivity between neural populations implicated in the cognitive control network was observed. Alternatively, less connectivity in the emotion-processing network (i.e., bilateral orbitofrontal, bilateral amygdala) was observed in response to the alcohol cues. Beltz et al., [31] suggest that the recruitment of cognitive control regions occurred in order to inhibit responding to alcohol cues on Go trials of the task (respond alcohol > fixation) when compared to neutral cues (respond neutral > fixation). Participants had slower response times when responding to alcohol images than to neutral images. In an fMRI study of another appetitive/rewarding behavior (i.e., food) with some neural response commonalities to alcohol, Batterink et al., [32] evaluated visual food cues on a Go/NoGo among adolescent girls ranging from lean to overweight. Appetizing desserts served as NoGo signals on the task. Batterink and colleagues found that relative to lean girls, the overweight girls showed less recruitment of neural regions responsible for inhibitory control during NoGo trials. Further, the insula and operculum showed increased activity that positively correlated with body mass index (BMI).

The goal of this study was to investigate the relationship between alcohol use and behavioral inhibition during a Go/NoGo task that included alcohol images as NoGo stimuli. As addictive behaviors progress (i.e., toward a pattern of heavy alcohol use) and become increasingly more cue dependent with less voluntary control, [33] we expect that alcohol cues as NoGo signals will lead to more inhibitory errors (i.e., difficulty withholding a response). Thus, these errors should be greater among heavier drinkers relative to the lighter drinkers. This is consistent with some behavioral studies reviewed above [20, 23] where the alcohol cues are highly salient for the heavy drinkers and less so for lighter drinkers or controls. At the neural level, we expect that greater difficulty of heavier drinkers (relative to lighter drinkers) in withholding a response to an alcohol cue will be manifested in increased activity in neural regions implicated in cognitive control and decision-making processes during NoGo trials. Further, and consistent with findings from Batterink et al., [32] we would expect that responses to beer cues during NoGo trials to recruit some neural areas implicated in reward and habit-based circuitry [32]. Thus, we anticipate increased activity in regions of the striatum, a substrate for habit learning, and the insula, emerging as a substrate that converts urges into habits [12], during the beer-cued NoGo signals. This is also consistent with meta-analytic findings [14, 28].

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants included 41 healthy and normal emerging adults ranging in age from 18–22. There was no significant difference in the proportion of females in each group. Twenty-one participants were heavy drinkers (52% female) and 20 were light drinkers (65% female). Fifteen (75%) light drinkers were Non-Latino White, 2 (10%) were Latino, 2 (10%) were Black, and 1 (5%) reported other ethnicity; 17 (81%) of heavy drinkers were Non-Latino White, 2 (9.5%) were Latino, and 2 (9.5%) were Black. There were no significant differences between groups with respect to gender (p=.42) or ethnicity (p=.71). Drinking groups were defined as follows:

Heavy drinkers

Male heavy drinkers recruited into the study had to currently consume 15 or more drinks during the week; female heavy drinkers had to currently consume 8 or more drinks during the week (see [34]). All heavy drinkers reported binging behavior at least twice weekly. A binge for males consisted of 5 or more drinks at one setting, and a binge for females consisted of 4 or more drinks at one setting (see [35]). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) scores were expected to be 8 or above for heavy drinkers. One heavy drinking participant self-reported lower problems with drinking on the AUDIT; however, this individual reported heavy drinking and binging behavior and was thus retained in the analysis and in the heavy drinking group.

Light drinkers

Light drinkers were expected to currently drink less than 3 times during the week and consume 2 or less drinks during any drinking episode, with no reported binging behavior. AUDIT scores were expected to be less than 7 (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics.)

Table 1.

Population Descriptive Statistics

| Light Drinkers N=20 |

Heavy Drinkers N=21 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (sd) | Range | Mean (sd) | Range | P | |

| Age | 20.75(1.07) | 18–22 | 20.19 (1.4) | 18–22 | .16 |

| AUDIT scorea | 3.9 (1.94) | 1–7 | 12.98(5.29) | 5–28 | <.0001 |

| Current drinking days per week | 2.35 (1.04) | 1–5 | 4.10 (1.33) | 3–7 | <.0001 |

| Number of drinks when drinking in past 30 days | 3.00 (.97) | 2–5 | 6.10 (1.26) | 4–8 | <.0001 |

| Self-reported binging | None | 5–20 | 100% | 5–20 | <.0001 |

| Post scan AUQ scoreb | 8.60 (3.07) | 33–42 | 9.76 (3.96) | 25–42 | .30 |

| Operation Span scores | 39.0 (2.97) | Range | 38.05(5.21) | Range | .51 |

Note:

AUDIT score = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test score;

AUQ = Alcohol Urge Questionnaire score

The mean age of the heavy drinkers was 20.19 (sd=1.4) and the mean age of the light drinkers was 20.75 (sd=1.07). All participants were right-handed and native English speakers. Participants were recruited through flyers on the campus of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, California and at sorority and fraternity houses.

Individuals with any history of psychiatric or neurological disorders or use of medications that affect the central nervous system were excluded from the study during recruitment. The groups were matched on age, ethnicity, and lifetime other drug use.

2.2 Measures Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)

Severity and frequency of past year alcohol consumption was assessed with the AUDIT [36]. Binge-drinking behavior was assessed with Questions 2 and 3 on the AUDIT. The AUDIT has been validated across a wide range of populations [37–39], including a young adult sample, with good sensitivity and specificity [40], and good internal consistency (alpha range, 0.75 to 0.94; [36, 41]). Test-retest reliabilities yield a median coefficient alpha of 0.83 (range 0.75 to 0.97; (see [39]) assessed across diverse timeframes.

Alcohol Urge Questionnaire (AUQ)

Subjective craving/urge was assessed after scans with an 8-item, self-report measure that assesses current urges to drink. Response options range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The AUQ has demonstrated significant positive correlations with an individual’s alcohol use severity and has been validated for assessing alcohol cravings in laboratory settings. The scale has very high internal consistency (alpha=.91) and good test–retest reliability (0.82) (see [42, 43]).

Operation Span Task (OSPAN)

Working memory capacity was assessed as a proxy measure for fluid intelligence with a validated, automated operation span task (alpha=.78; test-retest reliability r=.83) [44]. The task measures capacity to learn and maintain information in an active state in the presence of interference and demands controlled attention [45].

2.3 fMRI Go/NoGo paradigm

The alcohol Go/NoGo task was presented with a rapid event-related design format to the participants while their brain activity was monitored with BOLD fMRI. In each trial, participants were presented with one of the following pictures: a bottle of coke, a bottle of water or a bottle of beer. Participants were instructed to press a response button on the MRI-compatible keypad as soon as they saw the pictures of coke or water (i.e. “Go” signals) but to withhold their response when the beer bottle was presented to them (i.e. “NoGo” signals). Subjects were encouraged to respond as rapidly as possible to a target while on the screen without making errors. There were 160 “Go” trials and 40 “NoGo” trials or four times as many Go trials as NoGo trials to ensure individuals developed a pre-potent behavioral tendency. The duration of the trials ranged from 1.5s to 4.5s (i.e. mean duration was 2.1s). Duration of trials was jittered to enhance the sensitivity of BOLD signal detection. The order of the trials was randomized with the Optseq2 program (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/optseq/) to further optimize the efficiency of the design.

Along with scans, we also assessed individual’s performance on the task using signal detection analyses as follows: calculation of the parameter d-prime which is equal to the proportion of “hits” minus the proportion of “false alarms”. An increased number of responses to the NoGo trials (or false alarms) is indicative of problems with impulsivity. Individuals with inhibitory disorders typically show more inhibition failures to NoGo signals than controls. A “hit” occurs when a subject accurately responds to a Go signal with a button press, and a “false alarm” occurs when a subject fails to withhold a response to NoGo signal [46].

2.4 Imaging parameters and data pre-processing

Functional BOLD images and anatomical images were acquired with a Siemens 3T Magnetom Tim/Trio MR scanner located at the Dornsife Cognitive Neuroscience Imaging Center at the University of Southern California. Head coil arrays were used for parallel imaging to minimize signal loss and image distortion in the orbitofrontal cortex. Participants’ responses were collected online using a MRI-compatible keypad. The Go/NoGo paradigm was programmed in Matlab using the Psychophysics Toolbox extensions [47]. To synchronize the paradigm with the image acquisition, the onset of the Go/NoGo paradigm was initiated by a TR trigger from the scanner. The visual stimuli were back projected onto a screen through a mirror attached onto the head coil. Whole brain functional images were acquired using a z-shim gradient, single-shot T2*-weighted echo EPI sequence with PACE (prospective acquisition correction). The specific sequence is dedicated to reduce signal loss in the prefrontal and orbitofrontal areas. Scanning parameters were as follows: TR = 2000 ms; TE = 25 ms; flip angle =90°; 64 × 64 matrix size with resolution 3 × 3 mm2. Forty-one 2.5 mm axial slices were acquired to cover the cerebrum and most of the cerebellum with no gap. An anatomical T1-weighted structural scan was acquired using an MPRAGE sequence (TR = 1950 ms; TE = 2.26 ms; flip angle 7; 176 sagittal slices; 224 × 256 matrix size with spatial resolution as 1×1×1mm3).

The functional images were realigned with a least square rigid body transformation to correct for head movement. The anatomical image was co-registered to the mean functional image created in the realignment process. The grey matter of the co-registered anatomical image was segmented based on the modified ICBM tissue probability maps and normalized to the standardized MNI template. The normalization parameters determined in the segmentation process were applied to the functional images which were then spatially smoothed with an 8 mm full-width half-maximum Gaussian filter.

2.5 Data analysis

Analyses of behavioral measures were carried out using SAS® software Version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., 2011). Differences between groups on demographics, alcohol use frequency and severity, other drug use, working memory capacity, and Go/NoGo response were evaluated using t tests. With respect to heavy and light drinking groups, there were no significant differences between drinking groups with respect to age, post-scan alcohol urges, or working memory capacity (see Table 1). Correlations were estimated among individual scores on the AUDIT, AUQ, and task-related neural response. Behavioral measures on reaction times for hits and false alarms were used to calculate d-prime to provide information about cognitive processes of selective attention and inhibitory control.

Whole brain analyses of the functional images were performed using SPM8 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). The preprocessed functional images were analyzed statistically using a two-level generalized linear model approach [48]. The “Go”, “NoGo” and false alarms trials were modeled separately with the hemodynamic response function (HRF). Individual contrast images of the “Go” and “NoGo” trials were then entered into a second level (random effect) analysis and compared between the heavy and light drinker groups with a 2-sample t-test model. Activation maps of the heavy and light drinker groups and the subtraction results were presented by overlaying the statistical maps onto the standardized MNI anatomical image with a threshold of p<0.001 (uncorrected) and cluster size ≥ 10 voxels. This threshold is equivalent to p corrected < 0.05 based on Monte Carlo simulations to approximate signal to noise (AlphaSim; B.Ward;http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni/docpdf/ALPHASim.pdf).

3. Results

3.1 Behavioral Results

Behaviorally on the alcohol Go/NoGo task, the light drinkers made significantly more correct responses than the heavier drinkers (p<.03) and overall performance assessed with d-prime (z(Hit) minus z(FA)) was significantly better among the lighter drinkers (p<.004). Although not statistically significant, heavy drinkers made more inhibitory errors during the NoGo trials than the lighter drinkers (p<.106). Further, the heavy drinkers were faster to respond to the next trial following a beer-cued NoGo trial than the lighter drinkers (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Beer NoGo cued task by drinking status

| Heavy | Light | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P | |

| Mean proportion False Alarm across trials | 0.110 (.013) | 0.085 (.015) | 0.106 |

| Mean proportion Hit rate across trials | .978 (.003) | .988 (.004) | 0.030 |

| D’a | 3.399 (.117) | 3.858 (.117) | 0.004 |

| Mean reaction time Go Trials | 431.98 (9.36) | 446.07 (11.71) | 0.176 |

| Post Beer Image Reaction time | 440.25 (11.45) | 469.08 (12.06) | 0.045 |

Note:

D’= proportion of hits minus the proportion of false alarms ((z(Hit) minus z(FA)).

3.2 Imaging Results

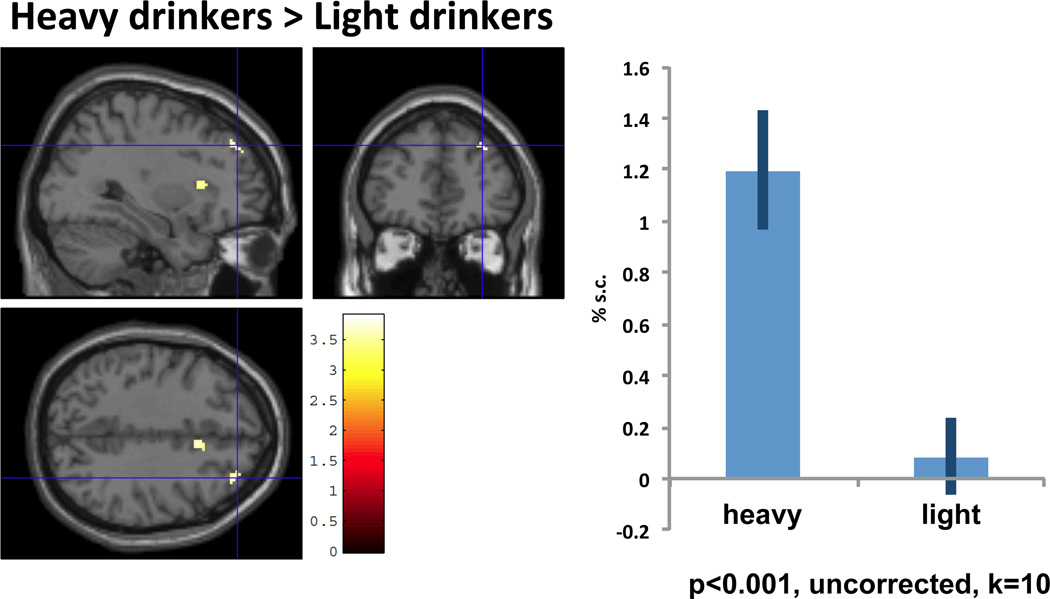

Heavy drinkers elicited significantly stronger activation in the right dorsolateral prefrontal (DLPFC) and anterior/mid cingulate, relative to light drinkers (p<0.001, uncorrected, k=10, see Figures 2 and 3). This DLPFC region of the brain has been implicated in working memory capacity and the ability to learn and maintain information in an active state, as well as the ability to control attentional processes [45, 49]. In addition, decision-making and inhibitory control functions are also linked to regions of the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and adjacent areas within the medial prefrontal cortex. The anterior/mid cingulate is often implicated in Go/NoGo tasks [14, 28].

Figure 2. Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal (32, 44, 38).

Percent signal change and activation of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (32, 44, 38): Sagittal and coronal views (t=3.89, p<.001, uncorrected, voxels >10) showed significant activation during NoGo trials among heavy drinkers relative to light drinkers. Graph provides the plots of % signal change for the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Error bars denote within-subject error.

Figure 3. Medial Frontal/Cingulate (8,16, 38).

Percent signal change and activation of medial frontal/anterior cingulate (8, 16, 38). Sagittal and coronal views (t=3.8, p<.001, uncorrected, voxels >10) showed significant activation during NoGo trials among heavy drinkers relative to light drinkers. Graph provides the plots of % signal change for the medial frontal/cingulate cortex.

We also observed significantly greater activity in heavy drinkers in the right anterior insula during exposure to the beer cues during NoGo trials relative to light drinkers (p<0.001, uncorrected, k=10, see Figure 4). The insula has been implicated in habit circuitry and is believed to mediate cue-induced urges [50], with the anterior insula also thought to translate interoceptive signals into self-awareness of subjective feelings and perhaps playing more of a role in decision-making processes [51, 52].

Figure 4. Right Anterior Insula (32, 18, 10).

Percent signal change and activation of insula (32, 18, 10). Sagittal and coronal views (t=3.66, p<.001, uncorrected, voxels >10) showed significant activation during NoGo trials among heavy drinkers relative to light drinkers. Graph provides the plots of % signal change for the anterior insula.

We observed no significantly greater neural activity in light drinkers, relative to heavy drinkers, during No/Go trials. No other contrasts between heavy and light drinkers were significant at p<.001. Finally, we observed no significant correlations between AUDIT or alcohol urge scores and BOLD response on the Go or NoGo trials.

4. Discussion

Adaptive behavior involves the ability to inhibit or override pre-potent responding when necessary, especially when encountering cue-triggered habitual behaviors. This study investigated behavioral performance and neural correlates of a Go/NoGo task with alcohol-related NoGo stimuli in heavy and light college age drinkers to determine effects of inhibitory processes and to investigate the role of cues on alcohol habit and control processes. This age group is particularly relevant to the study of neural systems since the confounds of brain maturational effects of decision-making processes have leveled off, allowing for clearer inferences about neural mechanisms. Behaviorally, the findings were consistent with some research findings using alcohol images as cues on Go/NoGo tasks [20, 23]. Overall, the heavier drinkers made more errors on the task during Go trials and when signal detection d-prime was used as an estimate of performance. However, commission errors were not statistically significantly different between the groups, consistent with Nederkorn et al. [22].

Imaging results revealed a number of important differences. First, the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) was significantly more active in heavy drinkers relative to light drinkers during NoGo trials. This finding diverges from those of Batterink et al. [32] on a food-specific Go/NoGo, which showed reduced activity within the brain regions implicated in inhibitory control processes among girls who were overweight relative to leaner girls during NoGo trials. This divergence should be interpreted with caution and not to imply that our findings are contradictory to those of Batterink et al. [32]. Generally, weakened inhibitory control is reflected by decreased frontal activity (e.g. reduction in DLPFC activity), but the increased incentive value or salience of the beer cues during NoGo trials for heavy drinkers may have served as an attentional bias cue resulting in greater effort needed to withhold a response [20, 23]. Indeed, the issue of whether increased activity of a given brain region should reflect a stronger efficiency of the associated function remains debatable (see [53]). Hence the key, and most important finding, is the engagement of the same brain regions by the Go/NoGo tasks, regardless of the direction of the brain activity. We interpret our current findings that the heavy drinkers would have stronger associations with alcohol-related cues as a result of repetitive alcohol use experiences, and therefore have more difficulty inhibiting their response when presented with a beer bottle as a NoGo signal. The observed activation in the DLPFC during NoGo beer trials can be interpreted as increased demand in task difficulty/decision-making for the heavy alcohol users given the potential salience of the cues. While we did not manipulate task difficulty, working memory capacity was assessed and no significant differences between groups were found. Therefore, we can at least rule out potential differences in working memory capacity as an explanation for differences in DLPFC activity in our sample. Findings from meta-analyses of Go/NoGo tasks report similar activation in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex across various complex Go/NoGo designs during No-Go signals [14, 28].

Theoretically, with respect to habit, cues constitute fundamental triggers of habit and play an important role in automatic reactivity. Inhibitory control processes are relevant primarily when there is the need to exert control or inhibition of a pre-potent behavioral tendency or impulse, usually in the face of such cues. These tendencies do not surface continuously but are activated primarily by antecedent cues that trigger the behavior. The ability to inhibit or override such pre-potent responding, then, becomes most relevant in the face of these cues. Given the role of the DLPFC in working memory and attentional processes, our interpretation of the imaging results, although speculative, is that the heavy drinkers required increased working memory demand and cognitive control efforts to withhold a response due to poorer inhibitory control from enhanced salience of alcohol cues, and this was reflected in the increased activity in the DLPFC. Additional research is needed to provide further empirical confirmation of this explanation. It is possible that compensatory increases in prefrontal activities may only be observed in heavy drinkers and not in alcohol dependent individuals. This may imply that these individuals still have adaptive prefrontal, inhibitory control systems that attempt to compensate, but perhaps are overwhelmed by strong well-learned associations that drive more habitual behavior. In contrast, individuals suffering from alcohol dependence and/or poly-substance abuse would not show these signs of compensatory increases in brain activity, thus reflecting potential impairment in inhibitory control systems.

Additionally, during NoGo trials we observed significantly greater activity among the heavy drinkers in the anterior/mid cingulate. This region is commonly activated on this task when processing NoGo trials [28, 54] and is important for cognitive/inhibitory control [6, 55–57]. Further, this region has been implicated in decision processes based on learning from reinforcement [58–61].

Finally, we observed significantly greater activity in heavy drinkers in the right anterior insula during exposure to alcohol-related cues during NoGo trials relative to light drinkers. The insula has been implicated in habit circuitry and tied to cue induced urges and emotional memories of physical effects of drugs [12, 50]. The insula also has been implicated in other habit forming or addictive behaviors, including dietary and smoking cue reactivity studies [62]. Recent neuroanatomical and neurological evidence suggests that the insular cortex plays a key role in translating interoceptive signals such as those generated by salient cues (e.g., alcohol-related cues) into what one subjectively experiences as a feeling of desire, anticipation, or urge [50, 51, 63]. Although we assessed urge, self-reported alcohol urges were not correlated with neural activity in the insula. This is not surprising though since assessment of urges occurred outside the scanner and some time after task performance. Other studies also have observed insula activation, spanning food and smoking cue reactivity studies, with no significant correlation with self-reported urges/craving (for meta analysis, see Tang et al. [62]). It is possible that among the heavy drinkers in this study, exposure to beer NoGo cues elicited automatic activation of emotional memories or representations of alcohol experiences, reflected in insula activation. This region is regularly activated during Go/NoGo tasks and has also been implicated in mediating response inhibition [54].

4.1 Limitations

Functional imaging studies provide insight into neural activation of cognitive processes associated with task performance. However, the findings are correlational and other variables may have affected our findings. Although the present study was one of the first neural evaluations of alcohol cues as NoGo images in a Go/NoGo task in heavy and light drinkers, we did not vary the beer bottle NoGo cues or assess individual preferences in alcohol, which might have attentuated our findings. Further, we did not switch NoGo beer trials with Go trials and evaluate neural response. More research is needed to evaluate cue effects on inhibitory processes at a neural level and to help parse general cognitive control processes from cue-induced habit-related reactivity on the task. Additionally, our binge-drinking variable did not include a time limit for consuming 4 (or 5 for males) drinks in approximately a 2-hour period, per the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) definition of binging [35]. Inclusion of such a time limit during recruitment and assessment may have helped to improve differentiation of drinking groups important to ensure the detection of neural effects from alcohol use. This is a consideration for future research in this arena. The binge-drinking behavior measure used in the study analyses included binge items from the validated AUDIT scale, used to verify heavy drinking when coupled with a high frequency of weekly use. Thus, the heavy drinker group was populated with participants who were reasonably classified.

Lastly, different networks mediate inhibitory processes and activation of these networks seem to vary by task. Given that the conditions that engage these different regions are still understudy [14, 28] it is not clear that the neural activity elicited on the beer NoGo trials was specific to response inhibition per se. Alternatively, it could also be attributed to attentional processes and interference from detection of salient task-related cues among the heavy drinkers.

5. Conclusion

In sum, the findings from this work help to increase our understanding of the neural substrates of control processes over alcohol use and the effects of cues in addictive behaviors, extending findings derived through behavioral research. Although varieties of Go/NoGo tasks have been investigated in the scanner, this is one of the first fMRI investigations of performance of an alcohol-cued Go/NoGo task in college age drinkers. This work demonstrates the sensitivity of neural measures and their ability to detect inhibitory control differences among heavy and light drinkers. Better understanding of distinct mediators of appetitive behaviors like alcohol use, and the neural effects of salient cues on regulatory processes can help inform intervention components designed to prevent or treat alcohol abuse.

Figure 1. Temporal layout of task.

The paradigm consisted of 160 Go trials and 40 No/Go trials (4:1 ratio). Go trials consisted of 80 coke bottles and 80 water bottles while NoGo trials consisted of 40 beer bottles. A fixation point (plus symbol) was presented before and after each image. Cue exposure occurred for a maximum of 1.5 seconds, and mean exposure for fixation was 2 seconds. Total trial duration was between 1.5 – 4.5 seconds.

Highlights.

Behaviorally, light drinkers made more correct responses than heavy drinkers

Performance assessed with d-prime was better among light drinkers

Heavy drinkers responded faster to trials following beer-cued NoGo trials

Heavy drinkers elicited stronger activation in right DLPFC and anterior/mid cingulate, relative to light drinkers

Relative to light drinkers, heavy drinkers elicited greater activity in the right anterior insula during beer-cued NoGo trials.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA017996), National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA024772, DA023368, DA024659) and the National Cancer Institute (CA152062).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no financial support or compensation has been received from any individual or corporate entity over the past three years for research or professional services and there are no personal financial holdings that could be perceived as constituting a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. 2012 NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4713. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spear LP. The adolescent brain and the college drinker: Biological basis of propensity to use and misuse alcohol. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;(SUPPL14):71–81. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, Hayashi KM, Greenstein D, Vaituzis AC, Nugent TF, III, Herman DH, Clasen LS, Toga AW, Rapoport JL, Thompson PM. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8174–8179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giedd JN, Lalonde FM, Celano MJ, White SL, Wallace GL, Lee NR, Lenroot RK. Anatomical brain magnetic resonance imaging of typically developing children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48:465–470. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819f2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crews FT, Boettiger CA. Impulsivity, frontal lobes and risk for addiction. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2009;93:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bechara A, Van Der Linden M. Decision-making and impulse control after frontal lobe injuries. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:734–739. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000194141.56429.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winstanley CA, Eagle DM, Robbins TW. Behavioral models of impulsivity in relation to ADHD: Translation between clinical and preclinical studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:379–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braver TS, Ruge H. Functional neuroimaging of executive functions. In: Cabeza R, Kingstone A, editors. Handbook of functional neuroimaging of cognition. 2nd edition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press; 2006. pp. 307–348. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood W, Neal DT. A new look at habits and the habit-goal interface. Psychol Rev. 2007;114:843–863. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.843. doi: 2007-13558-001 [pii] 10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bechara A, Noel X, Crone EA. Loss of willpower: Abnormal neural mechanisms of impulse control and decision-making in addiction. In: Wiers RW, Stacy AW, editors. Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: SAGE Publications; 2006. pp. 215–232. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stacy AW, Ames SL, Knowlton BJ. Neurologically plausible distinctions in cognition relevant to drug use etiology and prevention. Subst Use Misuse. 2004;39:1571–1623. doi: 10.1081/ja-200033204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noel X, Brevers D, Bechara A. A neurocognitive approach to understanding the neurobiology of addiction. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23:632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eagle DM, Bari A, Robbins TW. The neuropsychopharmacology of action inhibition: cross-species translation of the stop-signal and go/no-go tasks. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:439–456. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simmonds DJ, Pekar JJ, Mostofsky SH. Meta-analysis of Go/No-go tasks demonstrating that fMRI activation associated with response inhibition is task-dependent. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.07.015. doi: S0028-3932(07)00268-0 [pii] 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fillmore MT, Ostling EW, Martin CA, Kelly TH. Acute effects of alcohol on inhibitory control and information processing in high and low sensation-seekers. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2009;100:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dom G, D‘haene P, Hulstijn W, Sabbe B. Impulsivity in abstinent early - and late - onset alcoholics: differences in self - report measures and a discounting task. Addiction. 2006;101:50–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finn PR, Justus A, Mazas C, Steinmetz JE. Working memory, executive processes and the effects of alcohol on Go/No-Go learning: Testing a model of behavioral regulation and impulsivity. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:465–472. doi: 10.1007/pl00005492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowden SC, Crews FT, Bates ME, Fals-Stewart W, Ambrose ML. Neurotoxicity and neurocognitive impairments with alcohol and drug-use disorders: Potential roles in addiction and recovery. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:317–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noel X, Van der Linden M, D‘Acremont M, Colmant M, Hanak C, Pelc I, Verbanck P, Bechara A. Cognitive biases toward alcohol - related words and executive deficits in polysubstance abusers with alcoholism. Addiction. 2005;100:1302–1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noel X, Van der Linden M, D‘Acremont M, Bechara A, Dan B, Hanak C, Verbanck P. Alcohol cues increase cognitive impulsivity in individuals with alcoholism. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;192:291–298. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0695-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose AK, Duka T. Effects of alcohol on inhibitory processes. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:284–291. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328308f1b2. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328308f1b2 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nederkoorn C, Baltus M, Guerrieri R, Wiers RW. Heavy drinking is associated with deficient response inhibition in women but not in men. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weafer J, Fillmore MT. Alcohol-related stimuli reduce inhibitory control of behavior in drinkers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;222:489–498. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2667-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aron AR, Fletcher PC, Bullmore ET, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Stop-signal inhibition disrupted by damage to right inferior frontal gyrus in humans. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:115–116. doi: 10.1038/nn1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aron AR, Robbins TW, Poldrack RA. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends Cog Sci. 2004;8:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garavan H, Ross TJ, Stein EA. Right hemispheric dominance of inhibitory control: an event-related functional MRI study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8301–8306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wager TD, Sylvester CC, Lacey SC, Nee DE, Franklin M, Jonides J. Common and unique components of response inhibition revealed by fMRI. Neuroimage. 2005;27:323–340. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Criaud M, Boulinguez P. Have we been asking the right questions when assessing response inhibition in go/no-go tasks with fMRI? A meta-analysis and critical review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durston S, Casey BJ. What have we learned about cognitive development from neuroimaging? Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:2149–2157. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.10.010. doi: S0028-3932(05)00339-8 [pii] 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.10.010 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wetherill RR, Squeglia LM, Yang TT, Tapert SF. A longitudinal examination of adolescent response inhibition: neural differences before and after the initiation of heavy drinking. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;230:663–671. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3198-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beltz AM, Gates KM, Engels AS, Molenaar PCM, Pulido C, Turrisi R, Berenbaum SA, Gilmore RO, Wilson SJ. Changes in alcohol-related brain networks across the first year of college: A prospective pilot study using fMRI effective connectivity mapping. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2052–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Batterink L, Yokum S, Stice E. Body mass correlates inversely with inhibitory control in response to food among adolescent girls: An fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2010;52:1696–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Everitt BJ, Robbins T. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CDC Vital Signs: Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;41 [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA Council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA newsletter. 2004;3:3. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M. The alcohol use disorder identification test: Guidelines for use in primary health care. 1992 WHO Publication No. 92.4.

- 37.Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, Babor T. A Review of Research on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kokotailo PK, Egan J, Gangnon R, Brown D, Mundt M, Fleming M. Validity of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test in College Students. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:914–920. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128239.87611.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reinert DF, Allen JP. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: An Update of Research Findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:185–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fleming MF, Barry KL, MacDonald R. The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in a college sample. Int J Addict. 1991;26:1173–1185. doi: 10.3109/10826089109062153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Puente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Screening Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–8004. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bohn MJ, Krahn DD, Staehler BA. Development and initial validation of a measure of drinking urges in abstinent alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:600–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drummond DC, Phillips TS. Alcohol urges in alcohol - dependent drinkers: further validation of the Alcohol Urge Questionnaire in an untreated community clinical population. Addiction. 2002;97:1465–1472. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Unsworth N, Heitz RP, Schrock JC, Engle RW. An automated version of the operation span task. Behav Res Methods. 2005;37:498–505. doi: 10.3758/bf03192720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kane MJ, Engle RW. The role of prefrontal cortex in working-memory capacity, executive attention, and general fluid intelligence: An individual-differences perspective. Psychon B Rev. 2002;9:637–671. doi: 10.3758/bf03196323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saunders B, Farag N, Vincent AS, Collins FL, Jr, Sorocco KH, Lovallo WR. Impulsive errors on a go-nogo reaction time task: Disinhibitory traits in relation to a family history of alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:888–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brainard DH. The psychophysics toolbox. Spat Vis. 1997;10:433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Worsley KJ, Poline JP, Frith CD, Frackowiak RSJ. Statistical parametric maps in functional imaging: A general linear approach. Hum Brain Mapp. 1995;2:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Engle RW. Role of working-memory capacity in cognitive control. Curr Anthropol. 2010;51:S17–S26. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naqvi NH, Bechara A. The hidden island of addiction: the insula. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Craig AD. How do you feel—now? the anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paulus MP, Rogalsky C, Simmons A, Feinstein JS, Stein MB. Increased activation in the right insula during risk-taking decision making is related to harm avoidance and neuroticism. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1439–1448. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kanai R, Rees G. The structural basis of inter-individual differences in human behaviour and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:231–242. doi: 10.1038/nrn3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swick D, Ashley V, Turken U. Are the neural correlates of stopping and not going identical? Quantitative meta-analysis of two response inhibition tasks. Neuroimage. 2011;56:1655–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Botvinick MM. Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: An update. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Botvinick MM. Conflict monitoring and decision making: Reconciling two perspectives on anterior cingulated function. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2007;7:356–366. doi: 10.3758/cabn.7.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldstein RZ, Tomasi D, Rajaram S, Cottone LA, Zhang L, Maloney T, Telang F, Alia-Klein N, Volkow ND. Role of the anterior cingulate and medial orbitofrontal cortex in processing drug cues in cocaine addiction. Neuroscience. 2007;144:1153–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown JW, Braver TS. Learned predictions of error likelihood in the anterior cingulate cortex. Science. 2005;307:1118–1121. doi: 10.1126/science.1105783. doi: 307/5712/1118 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shima K, Tanji J. Role for cingulate motor area cells in voluntary movement selection based on reward. Science. 1998;282:1335–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kennerley SW, Walton ME, Behrens TE, Buckley MJ, Rushworth MF. Optimal decision making and the anterior cingulate cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:940–947. doi: 10.1038/nn1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Walton ME, Croxson PL, Behrens TE, Kennerley SW, Rushworth MF. Adaptive decision making and value in the anterior cingulate cortex. Neuroimage. 2007;36:T142–T154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tang DW, Fellows L, Small D, Dagher A. Food and drug cues activate similar brain regions: a meta-analysis of functional MRI studies. Physiol Behav. 2012;106:317. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Naqvi NH, Rudrauf D, Damasio H, Bechara A. Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking. Science. 2007;315:531–534. doi: 10.1126/science.1135926. doi: 315/5811/531 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]