Abstract

Objective

Pediatricians are frequently asked to address parents’ behavioral concerns. Time out (TO) is one of the few discipline strategies with empirical support and is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. However, correctly performed, TO can be a complex procedure requiring training difficult to provide in clinic due to time and cost constraints. The Internet may be a resource for parents to supplement information provided by pediatricians. The present study included evaluation of information on TO contained in websites frequently accessed by parents. It was hypothesized that significant differences exist between the empirically supported parameters of TO and website-based information.

Methods

Predefined search terms were entered into commonly used search engines. The information contained in each webpage (n = 102) was evaluated for completeness and accuracy based on research on TO. Data were also collected on the consistency of information about TO on the Internet.

Results

None of the pages reviewed included accurate information about all empirically supported TO parameters. Only 1 parameter was accurately recommended by a majority of webpages. Inconsistent information was found within 29% of the pages. The use of TO to decrease problem behavior was inaccurately portrayed as possibly or wholly ineffective on 30% of webpages.

Conclusions

A parent searching for information about TO on the Internet will find largely incomplete, inaccurate, and inconsistent information. Since nonadherence to any 1 parameter will decrease the efficacy of TO, it is not recommended that pediatricians suggest the Internet as a resource for supplemental information on TO. Alternative recommendations for pediatricians are provided.

Keywords: child discipline, parenting, internet, time out, behavior problems

Survey data indicate that 90% of pediatricians provide information on child discipline all or most of the time when conducting anticipatory guidance.[1] In addition, previous studies have found that behavioral issues are raised in 15% to 24% of all pediatric primary care visits,[2] with oppositionality the most common of all behavioral concerns.[3] Time out (TO) is a behavior change technique used to decrease undesired behavior by briefly removing an individual from a reinforcing environment and placing the individual into a less reinforcing environment for a period of time. It is used in several evidence-based manualized parent management training programs, including Parent-Management Training Oregon,[4] Parent–Child Interaction Therapy,[5] Helping the Noncompliant Child,[6] Defiant Children,[7] the Incredible Years Program,[8] and Triple P-Positive Parenting Program.[9] Furthermore, TO is one of the few discipline strategies recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). The AAP promotes TO through both their practice guidelines and website directed toward parents (healthychildren.org). In addition to AAP’s embrace of TO, TO has been widely used by the lay public, with 45% to 85% of parents report having used TO with their children.[10,11]

Time out has been a focus of research in behavioral psychology for 5 decades and has been found to reduce many types of problem behavior, including noncompliance, oppositionality, verbal and physical aggression, property destruction, yelling, and inappropriate sexual behavior.[12–15] The punishing effects of TO have been demonstrated for children of all ages, not only for those with nonclinical levels of disruptive behavior [16] but also for those with psychological disorders, developmental disabilities, mental retardation, severe emotional problems, and psychosis.[17–19] The voluminous data indicating the efficacy of TO in decreasing problem behavior suggest that it is a relatively robust procedure. However, TO does not consist of one discreet strategy but a set of multiple procedural components, several of which with multiple variations but the same underlying mechanisms of change. To date, there remains a dearth of research identifying the specific variables or set of variables, including child age, that impact TO effectiveness. Nevertheless, several parameters have been empirically demonstrated to impact the efficacy of TO, including regular provision of an enriched, positive environment for the child (when he/she is not in TO); providing 1 (and only 1) verbal warning to the child; delivering TO immediately following misbehavior; locating TO in a space with little reinforcement, activities, or stimuli available; enforcing TO with a “backup” consequence if a child escapes TO; releasing child from TO when the child is calm; having an adult release the child from TO; delivering TO contingent on target behaviors with consistency; and, when TO is due to noncompliance, requiring the child to comply with the original command immediately following release from TO.

When considering parameters for TO effectiveness, the nature of the environments in and out of TO must first be considered. The term “Time In” refers to the provision of a regular environment that is dense with reinforcement (e.g., high ratio of positive to negative interaction, physical affection, and activities of interest to the child). This availability of reinforcers in the child’s natural environment facilitates necessary creation of contrast in the child’s environment between when the child is placed in TO for misbehavior. The differential effectiveness of TO in reducing inappropriate behavior when the child’s natural environment is enriched with reinforcement versus largely void of reinforcement has been demonstrated.[18,20] With respect to the TO environment, research investigating differing degrees to which sources of reinforcement are available in TO has shown that TO effectiveness is clearly impacted by the amount of stimuli and activity available to the child during TO.[21] The more social interaction (e.g., someone looking at or talking with the child), visual and/or auditory stimuli (e.g., sight/sound of a television or children playing in the same room), or sensory stimuli (e.g., items within reach) that are available to the child during TO, the more interesting, and thus less effective, TO becomes.

Several factors are important to consider with respect to initiation and release from TO. The delay between inappropriate behavior and initiation of TO should be very short. Although this has yet to be directly demonstrated specifically with TO, suppression of behavior has consistently been shown to have an inverse relationship with the length of time punishment is delayed.[22–24] Providing children with 1 brief, unemotional warning such as, “If you do not do as I say, you will go to TO,” does not appear to decrease the efficacy of TO, and providing such a statement has been found to actually reduce the number of TOs necessary to reduce problem behavior.[25] However, providing more than 1 warning actually decreases the effectiveness of TO and does not reduce the number of TOs administered because TO is delivered with less immediacy.[26] With respect to who determines when the child can leave TO, evidence indicates that TO is significantly less effective when children are allowed to determine when TO ends (e.g., when they are “ready to leave”) compared to when an adult determines when TO is over.[27] Research on the criteria for leaving TO indicates that contingent release (i.e., releasing a child from TO only after a short period of quiet and calm behavior) is more effective in reducing disruptive behaviors during TO [17,28,29] and decreasing noncompliance in the natural environment[28,29] compared to noncontingent release (e.g., releasing a child after a period of time has elapsed regardless of behavior at the time of release).

A final parameter of release from TO relates to when a child is placed in TO for noncompliance. It is important that the original command is reissued and the child is required to comply after TO has ended. This TO requirement leads to greater decreases in noncompliance.[30] In theory, TO may often be ineffective in decreasing inappropriate behavior if the TO is a way for the child to escape or avoid aversive tasks.[20] For example, a child may refuse to comply with a parents’ command to pick up his or her toys because he or she finds the task to be unpleasant. If the child is placed in TO and is then not required to pick up the toys, noncompliance may be more likely in the future.

Another important parameter to TO is its enforcement when a child escapes TO. Several backup procedures have been suggested to enforce TO, including spanking, erecting barriers (e.g., a plywood board in front of a doorway), physically holding the child (e.g., a basket hold), response cost (e.g., removal of a previously earned item or privilege such as a small toy or extra screen time), repeatedly returning the child to TO, and applying additional consequences (e.g., no television or videogames, grounding, no dessert).[6,20,31] While anecdotal clinical experience suggests that response cost, repeated returns, and adding consequences are effective in reducing escape from TO, no empirical evidence exists as to the effectiveness of these strategies. The relative effectiveness of spanking, barriers, and holding has been examined empirically. Spanking and erecting barriers have been found to be equally effective in decreasing noncompliance and the number of escape attempts from TO, and both require a similar number of TO administrations to reduce noncompliance.[31–33] Spank and barrier procedures appear to be superior to holding the child in the TO chair in terms of the number of TOs necessary to reduce noncompliance to a criterion level,[31] perhaps because of their inherent aversiveness. Of course, physical means of discipline and control (such as spanking and holding the child in the TO chair) may be effective in the short term, but the negative side effects and long-term consequences may outweigh the short-term benefits. For example, physical discipline is itself associated with conduct problems[34] and has been demonstrated to actually reduce noncompliance to parental commands.[35] In addition, physical intervention may result in unintentional injury of the parent or child, becomes increasingly difficult as the child grows larger and stronger, and tends to become less effective with repeated use. These factors should be considered when selecting a TO enforcement procedure as well.

Consistency is another important parameter for TO effectiveness. It is important that TO be delivered once the procedure has been initiated. That is, when the parent has told the child that he or she must go to TO, the child must not be allowed to escape TO by suddenly agreeing to comply, running away, arguing, pleading, and so on because escape will serve to reinforce inappropriate behaviors and delays in compliance.[36]

An additional aspect of TO that is important to consider, though parameters are not clear in the research, is duration. TOs of moderate duration (approximately 4–5 minutes) are generally more effective than TOs of shorter duration and are generally as effective as longer duration TOs,[37] although the child’s age may influence this recommendation. Four-minute TOs have been shown to be more effective than TOs that were 1 minute or less in nonclinical 4- to 6-year-old children,[16] and 5- and 10-minute TOs were more effective than 1-minute TOs with hospitalized 4 to 12 year olds.[38] TOs of 5, 10, and 15 minutes have been shown to reduce inappropriate behavior to similar levels,[18,38] although it is usually recommended that moderate length TOs be used to allow the child more reinforcement opportunities for appropriate behavior in the natural environment[38] and to minimize the stress the parent may experience. Some Parent Management Training programs suggest that a child spend 1 to 2 minutes in TO per year of their age 7 despite a lack of consistent evidence that longer TOs are required as children age.[18,38]

Without adequate guidance on accurate implementation of effective TO procedures, parents of children with behavior problems may conclude that TO is ineffective and resort to harsh methods of discipline, such as yelling or spanking, which are strongly associated with externalizing and internalizing symptoms in children.[39] Given the importance of accurate, evidence-based information regarding implementation if TO, more time is often required than allowed during typical office visits to provide parents with adequate education regarding effective TO procedures. In addition, it is not cost-effective given that visits involving behavioral concerns are reimbursed at a significantly lower rate than are visits involving only medical concerns.[40] The Internet may be a cost- and time-efficient resource to supplement information usually provided by pediatricians regarding effective discipline. In fact, it is likely that parents refer to the Internet, including social media, for guidance on behavior management strategies before ever seeking help from a pediatrician. However, the accuracy and completeness of information on TO that is included in websites targeted toward the lay public is unknown. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the accuracy and completeness of information on TO provided on webpages frequently accessed by parents conducting a general search for guidance regarding TO implementation. We hypothesize that significant differences exist between the empirical definition of TO and the information parents would likely obtain from searching the Internet.

METHODS

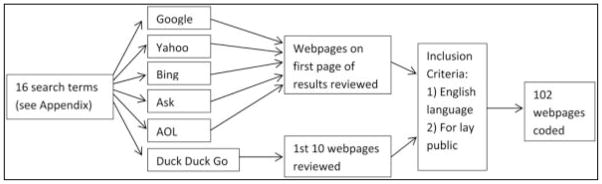

Internet searches were conducted by 2 of the authors. The search and review processes are summarized in Figure 1. Sixteen predetermined search terms were used by both authors (see Appendix A, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JDBP/A59). Boolean operators were not used to better approximate searches conducted by parents. The first 5 search engines listed in Figure 1 were used because research indicates that 99.82% of searches conducted in the United Stated during May 2012 used these sites.[41] Duck Duck Go was used to ensure that the search histories on the computers used during the study did not influence search results and to screen out sites that might be viewed frequently by parents. The number of results reviewed was limited as research suggests that the average seeker of health information visits 2 to 5 sites during a search.[42]

Figure 1.

Search and Review Methods

The information contained in each webpage was evaluated for completeness and accuracy based on several parameters identified as empirically demonstrated to impact the efficacy of time out (TO) by a thorough review of literature, as outlined in the introduction. These parameters include the following:

Reinforcing regular environment (i.e., “Time In”): includes a statement that the regular environment and/or caregiver-child relationship must be reinforcing.

Immediacy: includes a statement that TO is implemented immediately after a misbehavior or following 1 repeat of the command, or 1 (and only 1) verbal warning.

Consistency: includes a statement about the importance of consistency.

Location: includes a statement that very little social, sensory, or material reinforcement should be available.

Access to activities: indicates that no activities or stimuli are available to the child during TO.

Enforcement: states that the child receives a consequence for escape from TO or is returned to TO.

TO ends when child is calm: indicates that the child is released when he/she is calm (whether or not a certain amount of time has passed).

Adult ends TO: states that the parent, not the child, determines when the child can be released from TO.

Follow-through with the original command: statement indicating that when a child is placed in TO for noncompliance, the command must be reissued/the child must be required to comply with the original command after TO has ended.

Although duration is an important parameter, we did not include it as a parameter by which websites were evaluated due to the lack of clear guidelines in the literature for TO duration with consideration of varying ages and developmental levels. A parameter was coded as “accurate” when the webpage contained at least 1 sentence consistent with the empirically based parameter definition. A parameter was coded as “inaccurate” when the webpage contained a sentence about a parameter that conflicted with the definition of the parameter. For example, if a webpage included a specific example in which TO is given for noncompliance and is allowed to leave TO without the instruction being reissued, the “follow-through with the original command” parameter was coded as “inaccurate.” If a parameter was not mentioned at all on a webpage, it was coded as “no information.”

Data were also collected on consistency of information and whether TO was accurately portrayed as effective in decreasing problem behavior. When inconsistent information about a parameter was found within the same page, the item was coded as inaccurate. See Table 1 for the variables and how each was coded. “Webpage” refers to a document accessed through a search engine. “Website” refers to a collection of pages. For example, www.Wikipedia.org is a website, and the Wikipedia entry on TO is a webpage.

Table 1.

Coding Parameters and Variables

| Coding Options | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Reinforcing regular environment20,43 | Accurate/inaccurate/no information |

| Immediate or after 1 warning22–26 | Accurate/inaccurate/no information | |

| TO location20,43 | Accurate/inaccurate/no information | |

| Access to activites20,43 | Accurate/inaccurate/no information | |

| Consequence for escape27 | Accurate/inaccurate/no information | |

| TO ends when child is calm17,28,29 | Accurate/inaccurate/no information | |

| Adult ends TO27 | Accurate/inaccurate/no information | |

| TO delivered consistently36,37 | Accurate/inaccurate/no information | |

| Follow-through with command28 | Accurate/inaccurate/no information | |

| Variables | Inconsistencies w/in webpage | Present/absent |

| Effectiveness of TO is debatable w/in webpage | Yes/no | |

| TO is portrayed as harmful and or ineffective | Yes/no | |

| Inconsistencies on different webpages w/in a webpage | Present/absent |

TO, time out

Interrater reliability was assessed by having a second observer code 30% of webpages. The pages coded were randomly selected. For the variables with percent agreement lower than 80% initially, one of the original coders recoded the webpages and a third independent observer coded the webpages. Both kappa and percent agreement were calculated as measures of reliability because kappa is a highly conservative measure of reliability, and percent agreement is liberal. The kappa coefficient takes into account the possibility that raters agree or disagree by chance and ranges between 1 (perfect agreement) and 0 (agreement equivalent to chance).

RESULTS

Interrater Reliability

Kappa coefficients ranged from 0.38 to 1. Percent agreement ranged from 67% to 97% initially. When the 3 variables with percent agreement lower than 80% were recoded by an original coder and independently coded by a third observer, the percent agreement ranged from 82% to 100%. Kappas and percent agreement are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Interrater Reliability

| Parameter | Kappa | Interpretation of Kappa | Percent Agreement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reinforcing regular environment | a | Almost perfect | 97 |

| TO location | 0.56 (1.00) | Perfect | 73 (100) |

| Access to activities | 0.71 | Substantial | 82 |

| TO ends when child is calm | 0.44 (1.00) | Perfect | 67 (100) |

| Adult ends TO | 0.40 (0.84) | Almost perfect | 70 (91) |

| Consequence for escape | 0.72 | Substantial | 82 |

| Immediate or after 1 warning | 0.67 | Substantial | 85 |

| TO delivered consistently | 0.68 | Substantial | 85 |

| Follow-through with command | 0.38 | Fair | 91 |

Values in parentheses were calculated using a third coder.

Kappa could not be calculated due to near-perfect agreement. TO, time out.

Descriptive Analysis of Webpages Reviewed

Table 3 summarizes the types of webpages reviewed for the study. The majority of pages (64%) were in article format. Only 24% of pages included the credentials of the author(s), defined as stating at least the writers’ occupation(s). The page was considered to include credentials when the credentials appeared on the page or the author’s name was a hyperlink to the information. Only 6% of pages included references to primary resources.

Table 3.

Description of Pages Reviewed

| Type of Page | % of Pages Reviewed |

|---|---|

| Article | 64 |

| Discussion board | 20 |

| Blog | 11 |

| Video | 3 |

| Poll | 2 |

| Definition | 1 |

Accuracy and Completeness of Information on the Empirically Supported Parameters of Time Out

As reviewed in the Methods section, several elements must be present to increase the likelihood of the effectiveness of time out (TO). Table 4 summarizes the empirical elements critical to implementation of TO and the percentage of webpages that accurately reflect each parameter. Information is also provided on the percentage of webpages that provide inaccurate or no information.

Table 4.

Accuracy and Completeness of Information About Time Out

| Empirically Supported Parameters of TO | % of Webpages with Accurate Information | % of Webpages with Inaccurate Information | % of Webpages with No Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent decides when TO is over | 58 | 16 | 26 |

| Consequence for escape from TO | 41 | 12 | 47 |

| TO in location w/o sensory stimulation | 32 | 28 | 39 |

| TO is immediate or only 1 warning | 37 | 5 | 58 |

| Consistency is important | 34 | 3 | 62 |

| Child not allowed to engage in activities | 33 | 23 | 43 |

| TO terminated when child is calm | 24 | 52 | 25 |

| Child must comply with command after TO | 6 | 4 | 90 |

| Reinforcing regular environment/time in | 4 | 0 | 96 |

TO, time out.

Overall, most webpages lacked accurate information on the empirical foundation of TO. Notable inaccuracies included use of a TO location in which a high level of reinforcement is available (28%), allowing the child to engage in reinforcing activities (23%), holding or talking to the child after an “escape” from TO (12%), and allowing the child to decide when they are ready to leave TO (16%).

Absence of information was also characteristic of the webpages reviewed. The majority of webpages (58%) lacked guidance on duration of time between the inappropriate behavior and implementation of TO. In addition, 47% of webpages did not include information on what to do when a child leaves TO prematurely, which discussion boards indicated is one of the most common challenges with the technique.

Time out is most effective if the child is not released until he or she is calm, and the child is made to comply with the original command immediately following TO. Only 24% of webpages mentioned that the child must be calm before TO ends. A greater proportion of webpages (52%) stated that the TO ends after a specific period of time has elapsed, regardless of the child’s behavior in TO. Twenty-five percent of webpages did not include information on how TO should end. Notably, 90% of webpages did not mention that the child must comply with the original command following TO if the TO was issued due to noncompliance. Without this requirement, noncompliance may actually increase if the child prefers going to TO over completing the task he or she was instructed to do (e.g., picking up toys, setting the table).

Consistency of Information About Time Out on the Internet

Inconsistent information on 1 or more empirically supported TO parameters was found within 29% of the pages reviewed. Seventeen percent of pages portrayed the effectiveness of TO in decreasing problem behavior to be controversial (i.e., mention of TO as a harmful/ineffective and an effective discipline strategy within the same webpage). An additional 13% of pages simply stated that time out is ineffective for decreasing problem behavior. On 12 occasions, multiple pages from the same website (e.g., entries for Child Discipline and Time Out on Wikipedia.org) appeared in the search results. Of those 12 websites, 9 (75%) contained contradictory information on different pages. This indicates that the accuracy of information a parent obtains regarding TO can vary widely depending on which pages, even within the same website, that a parent happens to view.

DISCUSSION

Given the frequency with which pediatricians are asked by families to address behavior problems, it is imperative that pediatricians have strategies to handle these concerns. Time out (TO) is a behavior management strategy with strong empirical support that is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and used broadly by the lay public. Current evidence suggests that training enhances precision in use of the technique as well as parental acceptance; however, financial and time constraints may not allow pediatricians to provide parents with adequate guidance regarding the often complex implementation of this procedure. Results demonstrate that the Internet does not serve as a reliable supplement to information provided to parents on child discipline due to the high prevalence of incomplete and inaccurate information. The finding that information about TO on the Internet is of low quality is consistent with the conclusions of the majority of previous studies examining the quality of health information on the Internet.[44]

Overall, the most striking finding is that no webpage included accurate information on all evidence-based TO parameters. In other words, the likelihood that a parent would find complete and accurate information about TO by turning to the Internet is near zero. This is a significant finding because, as mentioned above, nonadherence to any one of the empirically supported TO parameters will decrease the efficacy of TO. The only parameter accurately recommended by a majority of webpages was parent-initiated release from TO. The majority of webpages failed to include information consistent with the empirical standards in all other domains. Most crucially, almost all webpages failed to discuss that TO cannot be effective unless the procedure creates a contrast in the child’s environment, such that good (or neutral) behavior is reinforced and problem behaviors result in lost access to that reinforcement-dense environment. If a child is not naturally surrounded by positive or stimulating activities, or is assigned numerous household responsibilities, then sitting in a quiet corner away from the family may be seen by the child as a neutral or pleasant experience, and TO will not be effective. A child who rarely receives attention for good or neutral/expected behavior may use problem behaviors to evoke interaction with a parent, including TO or other disciplinary tactics. Only 4% of webpages mentioned that the child’s regular environment must be reinforcing. The TO environment may be perceived as a neutral or pleasant experience (and thereby less effective) if the child can listen to music, hear the TV, watch their siblings play, have access to blankets, toys, books, etc., or sit with or talk to others during TO. Only 32% of webpages mentioned that TO must be located in a boring place, and only 33% mentioned that a child should not have access to any activities during TO. Of note, websites targeted toward the lay public provided by the AAP, National Institutes of Health, and National Institute of Mental Health, as well as descriptions on the web by behavioral psychologists, contained incomplete and/or inaccurate information about TO. For example, one webpage provided by the AAP through healthychildren.org describes several evidence-based parameters for TO, including provision of only 1 warning before TO, the need for TO to be boring, and providing a consequence for escape from TO (in this instance, holding); however, the webpage does not mention the importance of a reinforcement-rich regular environment or the need to reissue a command after TO ends when the TO was due to noncompliance.

Another significant finding of this study is the relatively high proportion of webpages (30%) that portrayed the TO as either harmful or ineffective in decreasing problem behavior. An abundance of evidence demonstrates that TO is effective, as reviewed above. The prevalence of assertions on the Internet that TO may be ineffective is unfortunate as this may discourage some parents from use of one of the few effective, noncorporal discipline strategies. However, in light of the findings in the current study regarding the abundance of incomplete and/or inaccurate information regarding TO parameters readily available to parents on the Internet, it is not surprising that TO is believed by many as an ineffective discipline strategy.

The primary limitation of this study is the inexhaustive nature of the search for information about TO. Given the fast paced, dynamic nature of the Internet, an exhaustive search is impossible. The decision was made to include “time out” in all search terms to limit the scope of the study, but searches for more general information on child discipline or childrearing may produce different results. Also, the number of responses to questions posted on discussion boards that were reviewed was limited due to the high number of responses on some webpages. It is possible that parents looking for information about TO on discussion boards would read more posts than we reviewed and therefore receive different information. Finally, as illustrated by the data obtained in this study, the fact that the term TO is used frequently by many professionals and lay people with vastly differing definitions and connotations makes the broad assertion of TO effectiveness a difficult one to make without specific consideration and qualification of implementation parameters, target problems, and populations.

If the Internet is not a source of accurate information about TO for parents, what is a pediatrician to do when time is short and the patient has hit their parent 5 times, ripped up the magazines in your office, and stuck a Cheerio in the little brother’s nose during the visit (i.e., behavior problems are of concern)? One option is to offer parent management training programs that include TO within the primary care setting. Empirically supported parent training programs that include time out have been provided in primary care settings and led to significantly reduced problem behavior.[45,46] Training for office providers can be found on the American Psychological Association’s Society of Clinical & Adolescent Psychology website at www.effectivechildtherapy.com. If the provision of evidence-based guidance and material does not lead to sufficient behavior change, and the child’s behavior is distressing to the parent or impacts family functioning, a referral to a behavioral health professional may be in order. Informing the parent that behavioral intervention will be time limited (possibly as few as 1–2 sessions) and focused on teaching a highly effective discipline strategy may increase the likelihood that the parent will accept the referral. When making referrals, it is important to recognize that not all behavioral health professionals have knowledge of empirically supported TO procedures. The person to whom you refer parents for assistance with TO should meet at least one of the following criteria: (1) behavioral in theoretical orientation, (2) board certified in behavior analysis, and/or (3) experienced in conducting a treatment known as Parent Management Training (PMT) or Parent Training. One common type of PMT is Parent-Child Interaction Therapy.

For milder behavioral concerns, a handout on conducting an effective TO may be helpful. The authors provide a handout outlining one variation of empirically based TO strategies (written at a fifth grade reading level) in the appendix to serve as a potentially helpful resource (see Appendix B, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JDBP/A60). Alternatively, parents may be referred to books that include instruction on child discipline, including age-appropriate TO procedures. Recommendations for parents of younger children include: Parenting the Strong-Willed Child, Parenting that Works: Building Skills That Last a Lifetime, and Your Defiant Child: Eight Steps to Better Behavior.[47–49] For parents of teenagers, Your Defiant Teen: Ten Steps to Resolve Conflict and Rebuild Your Relationship is recommended.[50]

Time out is an effective procedure that requires training to be successfully implemented. Future research should focus on strategies to increase the accuracy of information available in readily accessible formats that would augment guidance provided in clinic settings. Such projects may include websites with video training of TO procedures or mobile applications that outline parameters needed for effective TO. Such techniques may yield reduced clinic visit time and result in more effective discipline strategies used in the home. Future research should also focus on what pediatricians and behavioral health providers know about TO and how it is perceived because this may impact the frequency of use and effectiveness of TO when conducted by the public.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jeremy Albright, PhD, for his assistance with data analysis, Heather Burrows, MD, PhD, for her thoughtful comments on a previous version of this article, and Natalie Morris for assistance with initial data acquisition.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.McCormick KF. Attitudes of primary care physicians toward corporal punishment. JAMA. 1992;267:3161–3165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper S, Valleley R, Polaha J, et al. Running out of time: physician management of behavioral health concerns in rural pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e132–e138. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arndorfer RE, Allen KD, Aljazireh L. Behavioral health needs in pediatric medicine and the acceptability of behavioral solutions: implications for behavioral psychologists. Behav Ther. 1999;30:137–148. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson GR. The next generation of PMTO models. Behav Ther. 2005;28:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNeil CB, Hembree-Kigin TL. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. 2. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMahon RJ, Forehand RL. Helping the Noncompliant Child: Family-Based Treatment for Oppositional Behavior. 2. New York, NY: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barkley RA. Defiant Children. 2. New York, NY: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ. The Incredible Years parents, teachers, and children training series: a multifaceted treatment approach for young children with conduct problems. In: Kazdin AE, Weisz JR, editors. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford; 2003. pp. 224–240. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders MR. The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program as a public health approach to strengthening parenting. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22:506–517. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barkin S, Schendlin B, Ip EH, et al. Determinants of parental discipline practices: a national sample from primary care practices. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2007;46:64–69. doi: 10.1177/0009922806292644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caughy MO, Miller TL, Genevro JL, et al. The effects of healthy steps on discipline strategies of young children. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2003;24:517–534. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones RN, Sloane HN, Roberts MW. Limitations of “don’t” instructional control. Behav Ther. 1992;23:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendall PC, Nay WR, Jefers J. Timeout duration and contrast effects: a systematic evaluation of a successive treatment design. Behav Ther. 1975;6:609–615. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sachs DA. The efficacy of time-out procedures in a variety of behavior problems. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1973;4:237–242. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scarboro ME, Forehand R. Effects of two types of response-contingent time-out on compliance and oppositional behavior of children. J Exp Child Psychol. 1975;19:252–264. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(75)90089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobbs SA, Forehand R, Murray RG. Effects of various durations of timeout on the noncompliant behavior of children. Behav Ther. 1978;9:652–656. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mace FC, Page TJ, Ivancic MT, et al. Effectiveness of brief time-out with and without contingent delay: a comparative analysis. J Appl Behav Anal. 1986;19:79–86. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1986.19-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Jr, Manos MJ, et al. An evaluation of three time-out procedures for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behav Ther. 2004;35:449–469. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones RN, Downing RH. Assessment of the use of timeout in an inpatient child psychiatry treatment unit. Behav Interv. 1991;6:219–230. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solnick JV, Rincover A, Peterson CR. Some determinants of the reinforcing and punishing effects of timeout. J Appl Behav Anal. 1977;10:415–424. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1977.10-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brantner JP, Doherty MA. A review of timeout: a conceptual and methodological analysis. In: Axelrod S, Apsche J, editors. The Effects of Punishment on Human Behavior. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 87–132. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abramowitz AJ, O’Leary SG. Effectiveness of delayed punishment in an applied setting. Behav Ther. 1990;21:231–239. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camp DS, Raymond GA, Church RM. Temporal relationship between response and punishment. J Exp Psychol. 1967;74:114–123. doi: 10.1037/h0024518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trenholme IA, Baron A. Immediate and delayed punishment of human behavior by loss of reinforcement. Learn Motiv. 1975;6:62–79. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts MW. The effects of warned versus unwarned time-out procedures on child noncompliance. Child Fam Behav Ther. 1982;4:37–53. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Twyman JS, Johnson H, Buie JD, et al. The use of a warning procedure to signal a more intrusive timeout contingency. Behav Disord. 1994;19:243–253. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bean AW, Roberts MW. The effect of time-out release contingencies on changes in child noncompliance. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1981;9:95–105. doi: 10.1007/BF00917860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erford BT. A modified time-out procedure for children with noncompliant or defiant behaviors. Prof Sch Couns. 1999;2:205–210. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hobbs SA, Forehand R. Effects of differential release from time-out on children’s deviant behavior. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1975;6:256–257. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Everett GE, Olmi DJ, Edwards RP, et al. An empirical investigation of time-out with and without escape extinction to treat escape-maintained noncompliance. Behav Modif. 2007;31:412–434. doi: 10.1177/0145445506297725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts MW, Powers SW. Adjusting chair timeout enforcement procedures for oppositional children. Behav Ther. 1990;21:257–271. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Day DE, Roberts MW. An analysis of the physical punishment component of a parent training program. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1983;11:141–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00912184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts MW. Enforcing chair timeouts with room timeouts. Behav Modif. 1988;12:353–370. doi: 10.1177/01454455880123003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKee L, Roland E, Coffelt N, et al. Harsh discipline and child problem behaviors: the roles of positive parenting and gender. J Fam Violence. 2007;22:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lytton H. Disciplinary encounters between young boys and their mothers and fathers: is there a contingency system? Dev Psychol. 1979;15:256–258. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reitman D, Drabman RS. Read my fingertips: a procedure for enhancing the effectiveness of time-out with argumentative children. Child Fam Behav Ther. 1996;18:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forehand R. Time-out. In: Bellack AS, Hersen M, editors. Dictionary of Behavior Therapy Techniques. New York, NY: Pergamon Press; 1985. pp. 222–224. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGuffin PW. The effect of timeout duration on the frequency of aggression in hospitalized children with conduct disorders. Behav Interv. 1991;6:279–288. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bayer JK, Ukoumunne OC, Lucas N, et al. Risk factors for childhood mental health symptoms: national longitudinal study of Australian children. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e865–e879. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meadows T, Valleley R, Haack MK, et al. Physician “costs” in providing behavioral health in primary care. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2011;50:447–455. doi: 10.1177/0009922810390676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.StatCounter©. Top 5 search engines in the United States on May 2012. [Accessed July 18, 2012];Stat Counter Global Stats Web site. Available at: gs.statcounter.com/#search_engine-US-monthly-201205-201205-bar.

- 42.Fox S, Rainie L. Vital decisions: how Internet users decide what information to trust when they or their loved ones are sick. [Accessed July 18, 2012];Pew Internet & American Life Project Web site. 2002 Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2002/PIP_Vital_Decisions_May2002.pdf.

- 43.Shriver MD, Allen KD. The time-out grid: a guide to effective discipline. Sch Psychol Quart. 1996;11:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eysenbach G, Powell J, Kuss O, et al. Empirical studies assessing the quality of information for consumers on the world wide web: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;287:2691–2700. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.20.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lavigne JV, LeBailly SA, Gouze KR, et al. Treating oppositional defiant disorder in primary care: a comparison of three models. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:449–461. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner KMT, Sanders MR. Help when it’s needed first: a controlled evaluation of brief, preventative behavioral family intervention in a primary care setting. Behav Ther. 2006;37:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forehand R, Long N. Parenting the Strong-Willed Child. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Christophersen ER, Mortweet SL. Parenting That Works: Building Skills That Last a Lifetime. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barkley RA, Benton CM. Your Defiant Child: Eight Steps to Better Behavior. New York, NY: Guilford; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barkley RA, Robin AL. Your Defiant Teen: Ten Steps to Resolve Conflict and Rebuild Your Relationship. New York, NY: Guilford; 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.