Abstract

We describe the first report of the generation of 6,7-dehydrobenzofuran (6,7-benzofuranyne) from 6,7-dihalobenzofurans via metal-halogen exchange and elimination, in a manner similar to our previous work with 6,7-indole arynes. This benzofuranyne undergoes highly regioselective Diels-Alder cycloadditions with 2-substituted furans.

The existence of the benzyne reactive intermediate 1 has been known since 1953 (Figure 1).1 Since that initial landmark account, several other metastable benzenoid arynes have appeared in the literature, including the naphthalynes 2a-b and the pyridynes 3a-b.2 Over the last several years our group first3a-f followed by the Garg laboratory4a-f published numerous reports involving arynes derived from the three benzenoid positions of the ubiquitous indole nucleus (i.e., indolynes, 4a-c, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Benzyne and other common and recent arynes.

Indolynes have already demonstrated their value in the synthesis of complex natural products,3b,d,4e and have also been used recently in the construction of unique polycyclic indole libraries.3f The regioselectivity within various indolyne reaction manifolds has also been explored by our group and others.3,4 Our investigations in particular revealed, inter alia, that 6,7-indolynes show remarkable regioselectivity in Diels-Alder cycloadditions with 2-substituted furans (Scheme 1).3c,e

Scheme 1.

Regioselectivity in 6,7-indolyne cycloadditions.

The observed contrasteric regioselectivity has been rationalized in terms of the highly polarized nature of the 6,7-indolyne which imparts substantial asynchronous elctrophilic character to the initial bond-forming step in the cycloaddition reaction.3e

Surprisingly, arynes derived from the common heterocycle benzofuran are apparently unknown. Just as the indole nucleus appears in many natural products and commercial drugs,5 the related benzofuran moiety is also present in many natural products6 and therapeutically useful entities including the antiarrhythmia drug dronedarone (marketed in the United States by Sanofi-Aventis as Multaq).7 Benzofuran derived arynes would offer a rapid entry into novel functionalized and annulated benzofurans. We are pleased to report the first generation of 6,7-benzofuran arynes (6,7-benzofuranynes) and their regioselective cycloaddition with 2-substituted furans.

In our earlier work with indolynes, we chose to generate the reactive intermediate via metal-halogen exchange, utilizing o-dihalo substituted indoles.3 Based on our success with this general method, we attempted to prepare the 6,7-benzofuranyne in the same manner. Our intial objective was the synthesis of 6,7-dichlorobenzofuran (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 6,7-dichlorobenzofuran.

Commercially available 2,3-dichlorophenol was alkylated with bromoacetaldehyde diethyl acetal with Cs2CO3 in DMSO to give 8 in 93% yield.8 Many conditions were investigated to effect the cyclocondensation to give 6,7-dichlorobenzofuran. After much experimentation optimal results were achieved using polyphosphoric acid under Dean-Stark conditions to give the desired product 9 in 32% yield.9

Since the metal-halogen exchange of o-dichloroindoles required the use of excess t-BuLi, we also sought the synthesis of the corresponding 6,7-dibromobenzofuran (Scheme 3) which would be amenable to more facile aryne formation via n-BuLi. Thus, commercially available 3- bromophenol was first protected as its carbamate 11 with N,N-diethylcarbamoyl chloride in pyridine in quantitative yield.10 The ortho bromine was then introduced with 1,2-dibromoethane via directed ortho metallation (DoM)11 using LiTMP to afford the desired o-dibromobenzene 12 in 75% yield.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 6,7-dibromobenzofuran.

The carbamate was hydrolyzed in ethanolic sodium hydroxide to give 2,3-dibromophenol 13 in 90% yield. Alkylation with bromoacetaldehyde diethyl acetal as described above produced the desired intermediate 14 in 90% yield. Cyclocondensation was achieved in this case with Amberlyst-15 resin under the same conditions to give 6,7-dibromobenzofuran 15 in 22% yield.12 Attempts to optimize the yield with various other conditions (e.g., PPA as before) unfortunately gave no improvement. We attribute the modest yields in both cyclocondensation reactions to the slow reaction kinetics coupled with a self-condensation reaction that dominates the product distribution with increased but necessary reaction times. This cyclocondensation is the subject of continuing investigations.

With the necessary aryne precursors in hand, the generation of the 6,7-dehydrobenzofuran via metal-halogen exchange and elimination was attempted. Thus, the reaction of o-dichlorobenzofuran 9 in the presence of excess 2-t-butylfuran and 2.5 equivalents of t-BuLi in ether at −78 °C gave an 11.5:1 mixture of cycloadducts 16ab albeit in only 18% isolated yield (Scheme 4). Changing the reaction solvent to THF decreased the yield to just 5% but without affecting the regioisomeric ratio.

Scheme 4.

Generation of 6,7-dehydrobenzofuran and trapping with 2-t-butylfuran.

We previously found that with 6,7-indole arynes, the presence of excess t-BuLi yielded primarily regioselective and exoselective ring-opened cycloadducts in high yield (Scheme 5).3c Interestingly, no analogous ring-opened products were detected with the putative 6,7-dehydrobenzofuran cycloadducts.

Scheme 5.

Ring opening of the 6,7-indole aryne cycloadduct with t-BuLi.

We also found that 6,7-indolynes could be prepared from the corresponding 6,7-dibromoindole in consistenly much higher yield and without concomitant ring opening using a slight excess of n-BuLi.

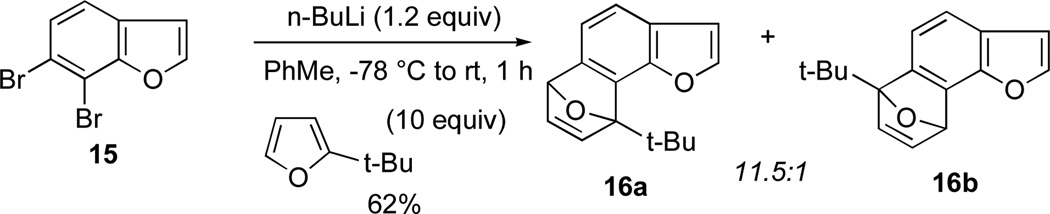

In accordance with this observation, 6,7-dibromobenzofuran was subjected to aryne generation and trapping as before with 1.2 equivalents of n-BuLi in ether or toluene (Scheme 6). Gratifyingly this gave a much improved 62% yield of cycloadducts, again as an 11.5:1 mixture of regioisomers. The nature of the regiochemical outcome is that the contrasteric product 16a dominates.

Scheme 6.

Generation and trapping of 6,7-dehydrobenzofuran from 6,7-dibromobenzofuran.

This experimental observation can be explained by our aforementioned hypothesis that polarized arynes of this type, similar to the 6,7-indolyne, imparts substantial asynchronous electrophilic character to the initial bond forming step with asymmetrically substituted dienes.3e

In a previous report we described the calculated free energies of activation in Diels-Alder cycloadditions with indolynes, benzofuranynes, and benzothiophenynes with 2-substituted furans.3e Low barriers to reaction are predicted in either gas phase or continuum solution leading to the contrasteric product with 2-tert-butylfuran in these three systems. The benzofuran case was predicted to have the lowest energies of activation by a small margin as expected given the greater electrophilicity of this heterocycle. This prediction is now confirmed in the case of 6,7-benzofuranyne by the experimental results presented here.

The previously reported regiochemical outcome of 6,7-indolyne Diels-Alder reactions with various 2-substituted furans was compared to the similar reaction with 6,7-benzofuranyne (Table 1). As is shown, the results parallel those seen in the 6,7-indolyne case except that it was generally found that the regioisomeric ratios were lower across the board with 6,7-benzofuranyne.

Table 1.

Regioselective Diesl-Alder cycloadditions between 6,7-dehydrobenzofuran and 2-substituted furans.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | furan, R | 16a | 16b | Yield, % |

| 1 | Me | 65 | 35 | 72 |

| 2 | Et | 78 | 22 | 85 |

| 3 | n-Pr | 73 | 27 | 83 |

| 4 | n-Bu | 75 | 25 | 60 |

| 5 | t-Bu | 92 | 8 | 62 |

| 6 | Ph | >99 | <1 | 63 |

| 7 | SO2Ph | <1 | >99 | 72 |

The exceptions were entries 6 and 7 in which 2-phenylfuran gave only the contrasteric isomer, and 2-phenylsulfonylfuran gave only the opposite isomer, respectively. These results are consistent with the view that electron-donating groups favor the more sterically crowded product while electron-withdrawing groups give the opposite regioisomer.

In conclusion we have provided the first example of an aryne derived from 6,7-dihalobenzofuran, namely, 6,7-dehydrobenzofuran (6,7-benzofuranyne), via metal-halogen exchange and elimination. As predicted, this aryne also exhibits remarkable regioselectivity in reactions with 2-substituted furans. Further investigations into this aryne and the related 6,7-dehydrobenzothiophene are in progress and the results will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge support of this work by the National Institutes of Health, Grant R01 GM069711 (KRB). We also acknowledge additional support of this work by the National Institutes of Health, the University of Kansas Chemical Methodologies and Library Development Center of Excellence (KU-CMLD), NIGMS Grant P50 GM069663. We thank Mr. Ben Neuenswander (KUCMLD) for providing select high-resolution mass spectral data. This paper is warmly dedicated to Professor Michael E. Jung on the occasion of his 65th birthday.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Material

A general experimental procedure for the generation and Diels-Alder trapping of 6,7-dehydrobenzofuran and select HRMS and NMR data can be found under supplementary material as a PDF document.

References

- 1.(a) Roberts JD, Simmons HE, Jr, Carlsmith LA, Vaughan CW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953;75:3290–3291. [Google Scholar]; (b) Roberts JD, Semenow DA, Simmons HE, Jr, Carlsmith LA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956;78:601–611. [Google Scholar]

- 2.For a review of arynes, see: Gampe CM, Carreira EM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:3766–3778. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107485. Hoffmann RW. Dehydrobenzene and Cycloalkynes. New York: Academic; 1967. Pellissier H, Santelli M. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:701–730. Wenk HH, Winkler M, Sander W. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:502–528. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390151. Reinecke MG. Tetrahedron. 1982;38:427–498.. Pyridynes: Kauffmann T, Boettcher FP. Angew. Chem. 1961;73:65–66. Martens RJ, den Hertog HJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1962:643–645.. Naphthalynes: Bunnett JF, Brotherton TK. J. Org. Chem. 1958;23:904–906. Huisgen R, Zirngibl L. Chem. Ber. 1958;91:1438–1452..

- 3.(a) Buszek KR, Luo D, Kondrashov M, Brown N, VanderVelde D. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4135–4137. doi: 10.1021/ol701595n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Buszek KR, Brown N, Luo D. Org. Lett. 2009;11:201–204. doi: 10.1021/ol802425m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Brown N, Luo D, VanderVelde D, Yang S, Brassfield A, Buszek KR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:63–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.10.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Brown N, Luo D, Decapo JA, Buszek KR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:7113–7115. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.09.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Garr AN, Luo D, Brown N, Cramer CJ, Buszek KR, VanderVelde D. Org. Lett. 2010;12:96–99. doi: 10.1021/ol902415s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Thornton PD, Brown N, Hill D, Neuenswander B, Lushington GH, Santini C, Buszek KR. ACS Comb. Sci. 2011;13:443–448. doi: 10.1021/co2000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Bronner SM, Bahnck KB, Garg NK. Org Lett. 2009;11:1007–1010. doi: 10.1021/ol802958a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tian X, Huters AD, Douglas CJ, Garg NK. Org. Lett. 2009;11:2349–2351. doi: 10.1021/ol9007684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cheong PHY, Paton RS, Bronner SM, Im G-YJ, Garg NK, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1267–1269. doi: 10.1021/ja9098643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Im G-YJ, Bronner SM, Goetz AE, Paton RS, Cheong PHY, Houk KN, Garg NK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17933–17944. doi: 10.1021/ja1086485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Bronner SM, Goetz AE, Garg NK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:3832–3835. doi: 10.1021/ja200437g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Goetz AE, Bronner SM, Cisneros JD, Melamed JM, Paton RS, Houk KN, Garg NK. Angew. Chem. 2012;124:2812–2816. [Google Scholar]

- 5.For a recent review see: Kochanowska-Karamyan AJ, Hamann MT. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:4489–4497. doi: 10.1021/cr900211p..

- 6.McCallion GD. Curr. Org. Chem. 1999:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoy SM, Keam SJ. Drugs. 2009;69:1647–1663. doi: 10.2165/11200820-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei L, Jianchang L, DeVincentis D, Mansour TS. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:7871–7876. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker P, Finke P, Thompson K. Synth. Commun. 1989;19:257–265. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dallaire C, Kolber I, Gingras M. Org. Synth. 2002;78:42–50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.For a review of DoM see: Snieckus V. Chem. Rev. 1990;90:879–933..

- 12.Dixit M, Sharon A, Maulik PR, Goel A. Synlett. 2006:1497–1502. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.