Abstract

Previous research has shown that neonatal rats can adapt their stepping behavior in response to sensory feedback in real-time. The current study examined real-time and persistent effects of ROM (range of motion) restriction on stepping in P1 and P10 rats. On the day of testing, rat pups were suspended in a sling. After a 5-min baseline, they were treated with the serotonergic receptor agonist quipazine (3.0 mg/kg) or saline (vehicle control). Half of the pups had a Plexiglas plate placed beneath them at 50 percent of limb length to induce a period of ROM restriction during stepping. The entire test session included a 5-min baseline, 15-min ROM restriction, and 15-min post-ROM restriction periods. Following treatment with quipazine, there was an increase in both fore- and hindlimb total movement and alternated steps in P1 pups and P10 pups. P10 pups also showed more synchronized steps than P1 pups. During the ROM restriction period, there was a suppression of forelimb movement and synchronized steps. We did not find evidence of persistent effects of ROM restriction on the amount of stepping. However, real-time and persistent changes in intralimb coordination occurred. Developmental differences also were seen in the time course of stepping between P1 and P10 pups, with P10 subjects showing show less stepping than younger pups. These results suggest that sensory feedback modulates locomotor activity during the period of development in which the neural mechanisms of locomotion are undergoing rapid development.

Keywords: development, locomotion, motor coordination, serotonin, sensory feedback

1. Introduction

Locomotion is the use of coordinated motor patterns to move from one place to another. It requires animals to perform not only limb movements or motor patterns involved in locomotion, but to adapt to changes in the environment and maintain equilibrium [1]. While precocial animals (e.g., horses and lambs) can perform, to some extent, all the above criteria for locomotion at birth, altricial animals (e.g., rats and humans) typically do not. This is not to say that altricial animals cannot show any locomotor behaviors at birth. On the contrary, research with rats has shown that many aspects of locomotion are already forming before birth. For example, beginning around embryonic day 16 (E16) of the rat’s 22-day gestation period, spontaneous movements are observed. By E20, these movements begin to show interlimb coordination [2], including antiphase/alternated limb coordination [3]. This spontaneous activity is important because it has been shown to play an organizational role in synapse and motor unit formation and reorganization [4].

The locomotor system of rats, much like humans, continues to undergo rapid change during the postnatal period, as necessary postural and neural mechanisms continue to develop [5]. This development generally proceeds in a rostrocaudal-proximodistal gradient. For instance, the shoulders and forelimbs begin to support the body around the end of the first week and the hindlimbs begin to draw under the body during the second half of the second week [6]. The ontogeny of locomotor behavior follows a similar pattern. One of the first action patterns to emerge is pivoting. Pivoting in its early stage occurs as early as postnatal day 2 (P2) with the forelimbs abducted and acting like paddles with the hindlimbs passive [6]. Crawling, where all limbs participate in propelling the body with the hindlimbs extended away from the body, emerges by P4-5 [5, 7]. By P8-10 rats can show short bouts of quadrupedal walking with their trunks lifted from the ground; however, their movement patterns are slow and irregular and the head still touches the ground [5, 6, 8, 9]. At around P15-16, their eyes open and more smooth and skillful locomotion is seen.

Thus locomotor behavior is very immature during the early newborn period and is expressed gradually during the postnatal period. One reason for this is due to weak muscles and poor postural control [6]. To experimentally examine their locomotor behavior then, infant rats are often suspended off the ground in a sling to alleviate gravitational constraints. Sensory or pharmacological stimulation then can be used to induce locomotor behavior. This paradigm is referred to as air-stepping. Common methods for evoking air-stepping in developing rats in vivo include presentation of olfactory stimuli, tail pinch, or treatment with pharmacological agents such as quipazine [10-14]. Quipazine is a 5-HT receptor agonist that has been shown to induce locomotor behavior in prenatal [15] and postnatal rats [11, 12, 16]. It is thought to act at 5-HT2A receptors [17]. More specifically, quipazine is thought to act at receptors in the lower thoracic and lumbar regions of the spinal cord, since a mid-thoracic spinal cord transection causes a reduction of forelimb stepping but not a loss of hindlimb stepping [12, 15].

There is ample research on the role of sensory feedback in the development of sensory systems (e.g., the visual, auditory, and somatosensory systems). However, few studies have investigated the role of sensory feedback on motor behavior, particularly locomotion, during early development. Some methods used to investigate the effects of sensory feedback during early motor development include: limb weighting [18-26], interlimb yoking [19, 27, 28], treadmill training [25, 29], and responses to different substrates [16]. Together, these studies provide compelling evidence that early motor systems can adapt to sensory changes both during the sensory experience (real-time) and after the stimulus is removed (persistent effects).

Despite tremendous strides in our understanding of how sensory feedback influences developmental processes, our understanding of how locomotor behavior is regulated by sensory feedback during early development remains unclear. Sensory processing undergoes rapid development during this period, including changes in cutaneous and reflex thresholds, the growth and integration of primary afferent terminals in the dorsal horn, changes in dorsal horn receptive field properties, and changes in neurotransmitter regulation of sensorimotor circuits (for review see [30]). Therefore it is important to explore differences in sensory regulation of motor behavior across development. Thus the current study examined developmental changes in the sensory regulation of locomotor behavior using the air-stepping paradigm. Quipazine-induced stepping was examined in postnatal day 1 (P1; 24 hours after birth) and P10 rats during and after a period of altered sensory feedback using ROM (range of motion) restriction. ROM restriction was enforced by placing a stiff substrate (Plexiglas plate) at a distance of 50% of limb length from the body [31], thus limiting the range of motion available during quipazine-induced stepping behavior. Persistent effects of the ROM restriction were investigated here to see if the perturbation produced a change in subsequent motor behavior, after the ROM restriction was removed. Thus, this study looked at the response to altered sensory input during locomotor activity at two different developmental ages, it employed a novel sensory perturbation (ROM restriction), and it examined both the real-time and persistent effects of this perturbation on locomotor behavior.

We expected that both P1 and P10 rats would show real-time and lasting changes in limb activity and limb trajectories since previous studies looking at interlimb yoking have shown that perinatal rats adapt their hindlimb movements during and after yoke training [32]. We also expected rat pups at the different ages to show differing degrees of real-time and persistent adaptations to the perturbation, due to differences in neural development. For example, the corticospinal pathway reaches the lumbar enlargement around P6 in rats [33] and thus may influence the adaptation to the perturbation in P10 pups. In addition, we expected P10 pups to show greater and longer lasting effects to the perturbation, due to the observation that persistent effects are often not seen in young infants in response to a perturbation but are reliably seen in older infants and adults [29].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Subjects

Subjects were 64 P1 or P10 male Sprague-Dawley rats. Pups were allowed to stay in their home cage until the time of testing. Adult animals were obtained from Simonson Laboratories and bred in the Animal Care Facility at Idaho State University. Pregnant females were pairhoused until a couple of days before birth, when they were housed individually. All animals were maintained in accordance with guidelines on animal care and use as established by the National Institutes of Health and by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee [34]. Animals were kept on a 12-hour light:dark cycle with food and water ad libitum.

2.2 Design

Each subject was tested on either P1 or P10, treated with quipazine or saline, and experienced ROM restriction or no ROM restriction. A total of 8 subjects was tested in each group. Each subject was tested in only one condition and at only one age. Litters were culled to 8 pups shortly after birth. Litters with fewer than 8 pups were excluded. Each subject within a group was selected from different dams to avoid litter effects. Only males were used to avoid confounding group differences with sex effects.

2.3 Behavioral Testing

Subjects were individually tested in an infant incubator that controlled temperature and humidity. They were tested at a thermoneutral temperature: 35°C on P1, and 30°C on P10. All pups showed evidence of recent feeding as evident by the presence of a milk band, and no indication of injury or bruising. Before testing, subjects were stimulated in the anogenital area with a soft paintbrush until urination and/or defecation occurred. They were acclimated to incubator conditions with up to two other littermates 30 min prior to testing.

To start the test session, subjects were secured in the prone posture to a vinyl-coated horizontal bar using a jacket with adjustable straps across the neck and abdomen [16]. The jacket was fitted so that it did not impede limb movement. Following a 5-min baseline, subjects were given an intraperitoneal injection of either quipazine (3.0 mg/kg) or 0.9% (wt/vol) saline (vehicle control). Volume of injection was based on body weight (i.e., 25 μl/5 g). Quipazine is a 5-HT receptor agonist that has been shown in previous studies to induce stepping behavior in fetal and newborn rats [12, 15], at the dose used in this study (3.0 mg/kg) [11, 15, 16]. Immediately following the injection, a 15-min ROM (range of motion) restriction was imposed for half of the subjects. To induce ROM restriction, a piece of Plexiglas was placed beneath the subject’s limbs at 50% of limb length when the limbs were fully extended [31]. The Plexiglas plate was supported by a clamp attached to an adjacent vertical bar. For the remaining half of the subjects, no ROM restriction was imposed (there was nothing placed beneath their limbs). After the 15-min period of ROM restriction, the Plexiglas was removed and the subject was recorded for a 15-min post-ROM restriction period. In the no ROM restriction condition, subjects continued to be recorded for the 15-min post-ROM restriction period.

The entire 35-min test session (5-min baseline, 15-min ROM restriction, and 15-min post-ROM restriction) was recorded using microcameras placed lateral and underneath the subject so that all limbs were visible. All sessions were recorded onto DVD for later behavioral scoring.

2.4 Behavioral Scoring

2.4.1 Limb Activity and Stepping Behavior

Scoring of limb activity and stepping behavior was done during DVD playback of the underneath camera view, using the software program JWatcher™ which records the category of behavior and time of entry (± 0.01s). Frequencies of alternated, synchronized, and non-stepping limb movements (e.g., twitches and unilateral steps) were scored. Alternated steps were defined as occurring when the pup’s homologous limbs exhibited sequential extension and flexion in one limb immediately followed by sequential extension and flexion in the other limb [15, 16]. Synchronized steps were defined as occurring when the pup’s homologous limbs exhibited simultaneous flexion and extension in both legs. Forelimbs and hindlimbs were scored in separate viewing passes. The scorer was blind to drug condition. Intra- and interreliability for scoring was > 90%. Scoring reliability was achieved via comparison to a previously scored stepping video file.

2.4.2 Limb Trajectories

Scoring of limb trajectories was done during DVD playback of the lateral camera view. The right forelimb and hindlimb were scored for each subject. First, maximum limb length was determined from the baseline or post-ROM restriction period. For maximum forelimb length, the ventrum of the subject and the tip of the toenail of the longest digit when the limb was fully extended were used as proximal and distal points, respectively. For the hindlimb, the base of the tail on the ventral side and the tip of the toenail of the longest digit when the limb was fully extended were used as proximal and distal points, respectively. Next, a semicircle was made using the maximum length as the radius, with the center of the circle being placed on the appropriate proximal point (i.e., ventrum for forelimb or base of tail for hindlimb). An inner semicircle was then drawn within the semicircle, with a radius equal to two-thirds the maximum length to create two dorsal-ventral limb trajectory areas: proximal (2/3 the distance of maximum limb length) and distal (outer 1/3 distance of maximum limb length). To create three rostral-caudal limb trajectory areas, two lines were drawn from the appropriate proximal point (i.e., ventrum or base of tail) at 60- and 120-degrees of the entire 180-degree semicircle, creating a front (0-60 degrees), center (60-120 degrees) and back (120-180 degrees) trajectory area. Thus, the dorsal-ventral trajectory space was divided into a proximal and distal area, wheras the rostral-caudal trajectory space was divided into a front, center and back area; these were calculated separately for the forelimb and hindlimb and for each subject.

Due to the time-consuming nature of this scoring and preplanned comparisons, only specific 1-min sections were scored: the last minute of baseline (T4), start of ROM restriction (T5), middle of ROM restriction (T12), end of ROM restriction (T19), start of the post-ROM restriction period (T20), middle of post-ROM restriction (T27), and end of the post-ROM restriction (T34). Total time spent in each trajectory area per 1-min section was scored. The scorer was blind to drug condition.

2.5 Data Analysis

2.5.1 Limb Activity and Stepping Behavior

Alternated and synchronized steps and total movements (all steps + non-stepping limb movements) of the forelimbs and hindlimbs were compared during the 35-min test session. Frequencies of total movements, alternated steps, synchronized steps, and the percentage of alternated and synchronized steps (calculated as a function of total limb movements) were summarized into 5-min time bins. Data were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA, with age, drug, and ROM condition as between subjects variables and time as the within subjects (repeated measure) variable. Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software. A significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted. Post hoc tests used Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference.

2.5.2 Limb Trajectories

Total time in each trajectory area (proximal, distal, front, center and back) per 1-min section (as described above) was scored for the forelimbs and hindlimbs. Data were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA, with age, drug, and ROM restriction condition as between subjects variables and time as a within subjects (repeated measure) variable. Preplanned comparisons examined differences between baseline trajectories (T4) and those seen at the start of ROM restriction (T5), end of ROM restriction (T19), after removal of ROM restriction (T20), and end of post-ROM restriction (T34). Additionally, comparison of sections within the ROM restriction period (T5, T12 and T19) was conducted to determine real-time changes due to the perturbation. The time bin preceding (T19) and following (T20) post-ROM restriction were compared to determine immediate adaptations to removal of the perturbation. Comparison of time bins during the post-ROM restriction period (T20, T27, and T34) was performed to look for persistent changes. Forelimb and hindlimb data were analyzed separately.

3. Results

3.1 Limb Activity and Stepping Behavior

3.1.1 Total Forelimb Movements

A four-way repeated measures ANOVA (2 age × 2 drug × 2 ROM restriction × 7 time bins) for total forelimb movements revealed main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 79.71, p < .001], drug [F(1, 56) = 167.19, p < .001], ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 10.28, p = .002], and time [F(6, 336) = 38.22, p < .001]. There were 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 8.62, p < .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 59.91, p < .001], ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 7.05, p < .001], and age and drug [F(1, 56) = 29.06, p < .001]. There also were 3-way interactions between age, drug and time [F(6, 336) = 11.24, p< .001], and age, drug, and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 4.02, p = .05]. On P1, quipazine-treated subjects showed significantly more forelimb movements than saline-treated subjects at all time points following baseline (T5-T30) (Figure 1A). On P10, significantly more forelimb movements were shown by quipazine-treated subjects compared to saline-treated subjects, from T5-T15 (Figure 1B). For quipazine-treated subjects, significantly fewer movements were seen on P10 compared to on P1, at baseline and from T10-T30. For P10 saline-treated subjects, there were significantly fewer total movements at all times except T20. Thus, while P1 quipazine-treated subjects showed more movements after baseline than P10 subjects and continued to show a high frequency of total forelimb movements throughout the test session, quipazine-treated P10 subjects only maintained a high frequency of total forelimb movements during the first 15 minutes following injection. On P1, quipazine-treated subjects exposed to ROM restriction approached significantly fewer total forelimb movements compared to non-restricted subjects (p=0.06). On P10, saline-treated subjects exposed to ROM restriction expressed significantly fewer total forelimb movements when compared to non-restricted subjects (Figure 1B). No significant differences were seen in P1 saline-treated subjects or P10 quipazine-treated subjects that received ROM restriction.

Figure 1.

Frequency of total forelimb movements for P1 (A) and P10 rats (B) by drug and ROM restriction condition. For all graphs, the shaded gray region reflects the period of ROM restriction. Points show means; vertical lines are SEM.

3.1.2 Alternated Forelimb Steps

For frequency of alternated forelimb steps there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 34.65, p < .001], drug [F(1, 56) = 246.84, p < .001], and time [F(6, 336) = 50.51, p < .001). There were 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 10.15, p < .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 53.51, p < .001], age and drug [F(1, 56) = 33.09, p < .001], and ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 2.32, p = .03]. As can be seen in Figure 2A, a reduction in forelimb steps happened during the ROM restriction period for ROM-restricted subjects. Also, there was a 3-way interaction between age, drug, and time [F(6, 336) = 11.08, p < .001]. On P1 and P10, there was a significant increase in alternated forelimb steps following baseline in quipazine-treated subjects when compared to saline-treated subjects. For quipazine-treated subjects, fewer alternated steps were seen on P10 compared to on P1, from T10-T30 (Figure 2A and B). For saline-treated subjects, there was no difference in the amount of steps between the two ages. As can be seen in Figure 2A and 2B, although both P1 and P10 quipazine-treated subjects showed a higher frequency of alternated forelimb steps after treatment with quipazine, the difference between the quipazine and saline groups became markedly smaller later in the test session for P10s. Further, P1 quipazine-treated subjects showed significantly more alternated steps than P10 subjects 5-min after baseline.

Figure 2.

Frequency and percentage of forelimb steps for P1 and P10 rats by drug and ROM restriction condition. The frequency of alternated forelimb steps (A,B), percent forelimb steps (C,D), frequency of synchronized forelimb steps (E,F), and percent synchronized forelimb steps (G,H) is shown for P1 and P10 rats, respectively. Points show means; vertical lines are SEM.

Because pups may differ in their amounts of overall limb activity, the percentage of alternated steps as a function of total movements was examined. For percent alternated forelimb steps there were main effects of drug [F(1, 56) = 309.13, p < .001] and time [F(6, 336) = 64.88, p < .001], 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 3.94, p = .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 58.44, p < .001]), and age and drug [F(1, 56) = 5.76, p = .02], and a 3-way interaction between age, drug, and time [F(6, 336) = 4.59, p < .001]. On P1 and P10, quipazine-treated subjects showed significantly higher percentages of alternated forelimb steps from T5-T30 compared to saline-treated subjects (Figure 2C and 2D). For quipazine-treated subjects, there was a significantly lower percentage of alternated steps on P10 compared to on P1, from T10-T30. For saline-treated subjects, there was no difference between the two ages. Thus, quipazine-treated subjects at both ages showed a significant increase in percent alternated forelimb steps after treatment with quipazine. Further, P1 quipazine-treated subjects showed a significantly higher percentage of alternated steps than P10 subjects after T10.

3.1.3 Synchronized Forelimb Steps

For synchronized forelimb steps there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 5.60, p = .02], drug [F(1, 56) = 20.50, p < .001], ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 16.03, p < .001], and time [F(6, 336) = 7.79, p < .001]. There were 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 2.38, p = .03], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 4.76, p < .001], ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 6.58, p < .001], age and drug [F(1, 56) = 12.44, p = .001] and drug and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 10.20, p = .002], and a 3-way interaction between drug, ROM condition, and time [F(6, 336) = 2.44, p = .03]. Quipazine-treated subjects that experienced ROM restriction showed significantly fewer synchronized forelimb steps during the ROM restriction period (T5-T15), compared to non-restricted subjects (Figure 2E and 3F). Also, more synchronized steps were seen at T20 in quipazine-treated subjects that did not experience ROM restriction. For saline-treated subjects in the ROM restriction condition, there was a significant decrease in synchronized steps during the ROM restriction period (T5-T15). Thus, ROM restriction suppressed synchronized forelimb steps in both drug conditions during the period in which it was implemented.

For percent synchronized forelimb steps there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 17.54, p < .001], drug [F(1, 56) = 6.69, p = .01], ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 11.16, p = .001] and time [F(6, 336) = 7.36, p < .001]. There were 2-way interactions between ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 4.88, p < .001], age and drug [F(1, 56) = 17.48, p < .001], age and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 3.90, p = .05], and drug and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 5.12, p = .03]. There also was a 3-way interaction between drug, ROM condition, and time [F(6, 336) = 2.11, p = .05] and a 4-way interaction between all factors [F(6, 336) = 2.19, p = .04]. On P1, quipazine-treated subjects exposed to ROM restriction showed a significantly lower percentage of synchronized forelimb steps at T15 compared to subjects that did not receive ROM restriction (Figure 2G). For P1 saline-treated subjects, those that received ROM restriction showed a significantly lower percentage of synchronized steps from T10 to T15 compared to non-restricted subjects. They also showed a significantly higher percent of synchronized steps at baseline. On P10, quipazine-treated subjects exposed to ROM restriction showed a lower percentage of synchronized steps at T5 and T10 compared to saline-treated subjects (Figure 2H). Also, a significantly lower percentage of synchronized steps was shown by subjects that did not receive ROM restriction at T20. Thus, lower percentages of synchronized forelimb steps were seen in quipazine-treated subjects and for P1 subjects treated with saline that received ROM restriction, during the ROM restriction period.

3.1.4 Forelimb Activity and Stepping Behavior Summary

Following treatment with quipazine, there were more total forelimb movements and alternated steps on P1 compared to on P10. Although P1 and P10 pups expressed a different number of alternated steps, pups at both ages showed a fairly high percentage of alternated steps. There were more synchronized steps and a higher percentage of synchronized steps on P10 compared to on P1. For pups that experienced ROM restriction, significant decreases were seen in total forelimb movements, the frequency of synchronized steps and percent synchronized steps. This effect was only significant during the ROM restriction period (T5-T15).

3.1.5 Total Hindlimb Movements

For total hindlimb movements there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 52.96, p < .001], drug [F(1, 56) = 113.68, p < .001], and time [F(6, 336) = 40.78, p < .001]. There were 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 22.77, p < .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 44.51, p < .001], ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 3.25, p = .004], and age and drug [F(1, 56) = 34.77, p < .001]. There also was a 3-way interaction between age, drug, and time [F(6, 336) = 22.48, p < .001]. On P1, quipazine-treated subjects expressed significantly more total hindlimb movements than saline-treated subjects at all time points except baseline (Figure 3A). On P10, quipazine-treated subjects showed significantly more total movements from T5-T15, but significantly fewer movements at T30, compared to saline-treated subjects (Figure 3B). In quipazine-treated subjects, significantly fewer total movements were seen on P10 compared to on P1, from T15-T30. No significant differences were seen between saline-treated subjects. Thus, at both ages, quipazine-treated subjects showed an increase in total hindlimb movements after baseline, but this increase was only temporary (T5-T15) on P10. Fewer total movements were seen at P10, compared to at P1, 15 minutes after treatment with quipazine.

Figure 3.

Frequency of total hindlimb movements for P1 (A) and P10 rats (B) by drug and ROM restriction condition. Points show means; vertical lines are SEM.

3.1.6 Alternated Hindlimb Steps

For alternated hindlimb steps there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 38.52, p < .001], drug [F(6, 336) = 174.70, p < .001] and time [F(6, 336) = 46.99, p < .001], 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 26.12, p < .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 38.89, p < .001], and age and drug [F(1, 56) = 39.68, p < .001], and a 3-way interaction between age, drug and time [F(6, 336) = 24.87, p < .001]. On P1, significantly more alternated hindlimb steps occurred in quipazine-treated subjects after baseline (T5-T30) compared to saline-treated subjects (Figure 4A). On P10, quipazine-treated subjects showed significantly higher frequencies of alternated steps from T5-T25 compared to saline-treated subjects (Figure 4B). Significantly more alternated steps were seen in quipazine-treated subjects on P1 compared to on P10, from T15-T30. Thus, while P1 quipazine-treated subjects continued to show a high frequency of alternated hindlimb steps after baseline, quipazine-treated P10 subjects only maintained a high frequency of total hindlimb movements during the 25 minutes following baseline. Further, P1 quipazine-treated subjects showed significantly more alternated steps than P10 subjects after T15.

Figure 4.

Frequency and percentage of hindlimb steps for P1 and P10 rats by drug and ROM restriction condition. The frequency of alternated hindlimb steps (A,B), percent hindlimb steps (C,D), frequency of synchronized hindlimb steps (E,F), and percent synchronized hindlimb steps (G,H) is shown for P1 and P10 rats, respectively. Points show means; vertical lines are SEM.

For percent alternated hindlimb steps there were main effects of drug [F(1, 56) = 395.84, p < .001] and time [F(6, 336) = 83.88, p < .001], 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 14.99, p < .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 46.65, p < .001], and age and drug [F(1, 56) = 9.49, p = .003], and a 3-way interaction between age, drug, and time [F(6, 336) = 8.44, p < .001]. On P1 and P10, quipazine-treated subjects showed a significantly higher percentage of alternated hindlimb steps following baseline (T5-T30), compared to saline-treated subjects (Figure 4C and 4D). For quipazine-treated subjects, significantly lower percentages of alternated steps occurred on P10 compared to on P1, from T15-T30. For saline-treated subjects, there was a higher percentage of alternated steps at T5 on P10 compared to on P1. Thus, quipazine-treated subjects showed significantly higher percentages of alternated steps following baseline at both ages. Further, P1 quipazine-treated subjects showed higher percentages of alternated steps after T15 compared to P10 quipazine-treated subjects.

3.1.7 Synchronized Hindlimb Steps

For synchronized hindlimb steps there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 24.52, p < .001] and time [F(6, 336) = 4.68, p < .001]. There were 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 5.32, p < .001] and drug and time [F(6, 336) = 5.02, p < .001], and a 3-way interaction between age, drug and time [F(6, 336) = 3.22, p = .004]. On P1 and P10, quipazine-treated subjects showed significantly more synchronized hindlimb steps at T5 and significantly fewer synchronized steps at baseline and T30, compared to saline-treated subjects (Figure 4E and 4F).

For percent synchronized hindlimb steps there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 45.57, p < .001], drug [F(1, 56) = 6.38, p = .01] and time [F(6, 336) = 4.42, p < .001], and a 2-way interaction between age and time [F(6, 336) = 6.05, p < .001]. Follow-up analyses of the main effects showed that P10 subjects showed a higher percentage of synchronized steps compared to P1 subjects, that saline-treated subjects showed a higher percentage of synchronized steps than quipazine-treated subjects, and that the percent of synchronized steps increased after baseline. Follow-up analysis of the 2-way interaction between time and age showed a significantly higher percentage of synchronized steps on P10 following baseline (T5-T30) compared to on P1. These effects are shown in Figure 4G and 4H.

3.1.8 Hindlimb Activity and Stepping Behavior Summary

Following treatment with quipazine, more total hindlimb movements and alternated steps were shown on P1 compared to on P10. Quipazine-treated P10 subjects showed a decrease in activity beginning at T15 that was not characteristic of P1 subjects. However, P1 and P10 subjects showed fairly high percentages of alternated steps. Also, there were more synchronized steps and a higher percentage of synchronized steps on P10 versus P1.

3.2 Limb Trajectories

3.2.1 Forelimb Trajectories

First we analyzed time spent in the dorsal-ventral limb trajectory space. Since the limb can occupy only the proximal area (within 2/3 distance of limb extension) or the distal area (outer 1/3 distance of limb extension) at any given moment, we only analyzed time spent in the distal area. For time spent in the distal area, there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 20.77, p < .001], ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 7.94, p = .007], and time [F(6, 336) = 10.40, p < .001]. There were 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 5.45, p < .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 4.82, p < .001], and ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 4.95, p < .001], and a 3-way interaction between drug, ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 2.99, p = .007]. Data are shown in Figure 5. For the main effect of age, subjects showed significantly more time in the distal area on P10 compared to on P1. For saline-treated subjects, those that experienced ROM restriction spent less time in the distal area during the ROM restriction period (T5-T19), compared to subjects that did not receive ROM restriction (Figure 5C and 5G). This makes sense, given that the perturbation blocks much of the distal area. Also, saline-treated subjects that received ROM restriction showed less time in the distal area at T5 and T19 than quipazine-treated subjects that received ROM restriction. There was no difference in dorsal-ventral limb trajectories for quipazine-treated subjects. Thus, ROM restriction changed the pattern of dorsal-ventral forelimb trajectories during ROM restriction in saline-treated subjects only.

Figure 5.

Dorsal-ventral forelimb trajectories for P1 and P10 rats by drug and ROM restriction condition. Graphs show duration of time spent in the distal and proximal trajectory areas for 1-min sections during baseline, ROM restriction period, and the post-ROM restriction period. In the top half of the figure, data are shown for quipazine-treated (A,B) and saline-treated (C,D) rats on P1 that experienced ROM restriction or were non-restricted, respectively. In the bottom half of the figure, data are shown for quipazine-treated (E,F) and saline-treated (G,H) rats on P10 that experienced ROM restriction or were non-restricted, respectively. Points show means; vertical lines are SEM.

The rostral-caudal trajectory space was divided into front, center, and back areas. For time spent in the front with the forelimbs there were main effects of drug [F(1, 56) = 38.08, p < .001], ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 26.61, p < .001], and time [F(6, 336) = 60.49, p < .001], 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 7.98, p < .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 19.92, p < .001], ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 53.97, p < .001], age and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 3.98, p = .05], and drug and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 9.08, p = .03]. Also, there were 3-way interactions between age, ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 3.93, p = .001] and drug, ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 4.14, p = .001], and a 4-way interaction between age, drug, ROM condition and time that approached significance [F(6, 336) = 2.01, p = .06]. Quipazine-treated subjects spent significantly more time in the front area with the forelimbs compared to saline-treated subjects, subjects that experienced ROM restriction showed more time in the front area compared to non-restricted subjects, and time in the front area increased significantly after baseline. P1 and P10 subjects that received ROM restriction showed more time in the front area from T5-T19 (Figure 6A, 6C, 6E, and 6G) compared to subjects that did not receive ROM restriction (Figure 6B, 6D, 6F, and 6H). P10 subjects that experienced ROM restriction showed significantly less time at T4 and significantly more time from T12-T20 in the front area, than P1 subjects that received ROM restriction. For P10 subjects that did not experience ROM restriction, significantly less time was spent in the front area at T4. Thus, for subjects at both ages that received ROM restriction, less time was spent in the front area during the ROM restriction period compared to subjects that were not ROM restricted. This can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Rostral-caudal forelimb trajectories for P1 and P10 rats by drug and ROM restriction condition. Graphs show duration of time spent in the front, center, and back trajectory areas for 1-min sections during baseline, ROM restriction period, and the post-ROM restriction period. In the top half of the figure, data are shown for quipazine-treated (A,B) and saline-treated (C,D) rats on P1 that experienced ROM restriction or were non-restricted, respectively. In the bottom half of the figure, data are shown for quipazine-treated (E,F) and saline-treated (G,H) rats on P10 that experienced ROM restriction or were non-restricted, respectively. Points show means; vertical lines are SEM.

For time spent in the center area with the forelimbs there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 8.55, p = .005], drug [F(1, 56) = 137.28, p < .001], ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 79.44, p < .001] and time [F(6, 336) = 86.65, p < .001], and 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 7.63, p < .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 29.58, p < .001], ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 58.23, p < .001], age and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 3.94, p = .05] and drug and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 14.71, p < .001]. There also were 3-way interactions between age, drug and time [F(6, 336) = 2.31, p = .03], age, ROM and time [F(6, 336) = 5.74, p < .001], and drug, ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 7.45, p < .001]. In general, P1 subjects spent less time in the center area with the forelimbs than P10 subjects, quipazine-treated subjects spent less time in the center than saline-treated subjects, subjects that received ROM restriction showed less time in the center compared to non-restricted subjects, and time in center decreased after baseline. On P1, quipazine-treated subjects spent significantly less time in the center area from T12-T34 compared to saline-treated subjects (Figure 6A and 6C). On P10, quipazine-treated subjects spent less time in center at T12 and from T20-34 compared to saline-treated subjects, with T19 approaching significance (p = .06) (Figure 6E and 6G). On P10, subjects in both drug conditions showed significantly more time in center at T4, T27 and T34 compared to P1 subjects. P10 subjects treated with saline also showed an increase in the center at T20 compared to P1 saline-treated subjects. Significantly less time was spent in the center area during ROM restriction (T5-T19) on both P1 and P10 for subjects that received ROM restriction (Figure 6A, 6C, 6E, and 6G) compared to subjects that did not receive restriction (Figure 6B, 6D, 6F, and 6H). This was the case for quipazine- and saline-treated subjects. Also, saline-treated subjects spent less time in center at T20. Thus, experience with ROM restriction decreased the time spent in the center area with forelimbs for both drug conditions, during the time ROM restriction was imposed. Less time in center also was seen at the beginning of the post-ROM restriction period in saline-treated subjects.

For time spent in the back area with the forelimbs there were significant effects of age [F(1, 56) = 20.83, p < .001], drug [F(1, 56) = 7.74, p = .007], and time [F(6, 336) = 9.03, p < .001]. There were 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 3.90, p = .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 2.99, p = .007], and age and drug [F(1, 56) = 5.44, p = .02], 3-way interactions between age, drug and time [F(6, 336) = 4.81, p < .001], age, ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 2.12, p = .05], and drug, ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 2.20, p = .04], and a 4-way interaction between all factors [F(6, 336) = 2.12, p = .05]. In general, more time was spent in the back with the forelimbs on P1 than on P10, quipazine-treated subjects showed more time in the back area than saline subjects, and time in the back area increased after baseline. On P1, quipazine-treated subjects spent significantly more time in back at T5 and from T27-T34 compared to saline-treated subjects. On P10, quipazine-treated subjects spent significantly more time in back at T20 and T34 compared to saline subjects. For quipazine-treated subjects, significantly more time was spent in back with the forelimbs from T5-T34 on P1 (Figure 6A and 6B) compared to on P10 (Figure 6E and 6F). Further, for saline-treated subjects, significantly more time was spent in the back at T12, T20, and T34 on P1 (Figure 6C and 6D) than on P10 (Figure 6G and 6H). Thus, quipazine-treated subjects at both ages spent more time in the back area compared to saline-treated subjects during the post-ROM restriction period. For P1 saline-treated subjects, experience with ROM restriction increased the amount of time spent in the back at T20 compared to non-restricted subjects. For P1 quipazine-treated subjects, an increase in the back area approached significance at T34 (p = .06) for subjects that experienced ROM restriction compared to subjects that did not receive ROM restriction.

Summary. During the ROM restriction period (T5-T19), restricted subjects spent less time in the distal and center areas with the forelimbs. Saline-treated subjects that experienced ROM restriction also showed a decrease in center at T20. Consequently, there was an increase in the front area during the ROM restriction period (T5-T19) for P1 saline-treated subjects and P10 quipazine-treated subjects. For P1 quipazine-treated subjects there was an increase in the front area from T5-T12. For P10 subjects treated with saline, there was an increase in the front area from T5-T20 and at T34, and an increase in the back area at T20.

3.2.2 Forelimb Trajectories, Preplanned Comparisons

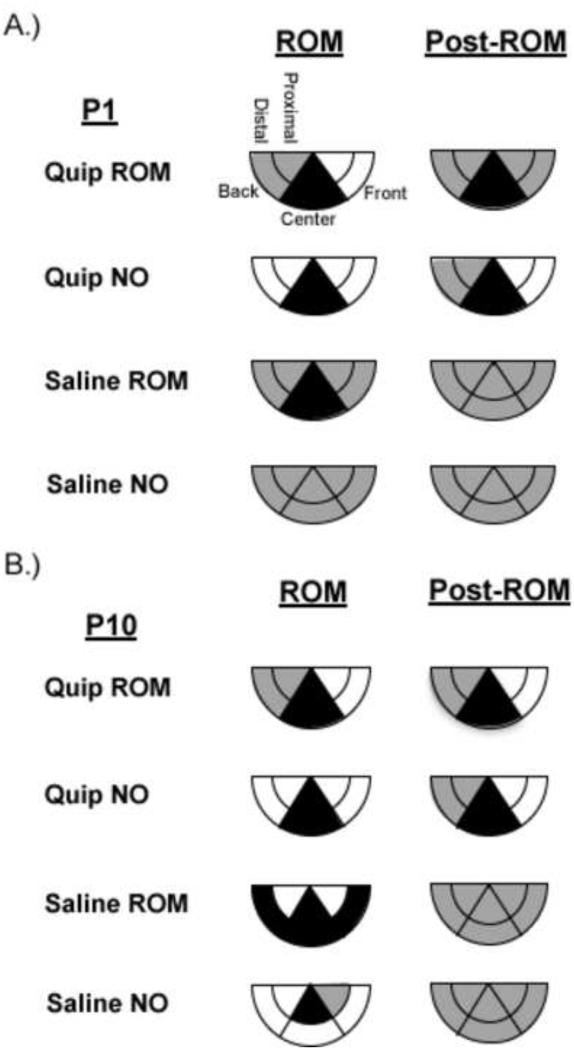

Because presentation of preplanned comparisons for all groups is space prohibitive, here we focus our analysis on only the ROM-restricted groups. However, a summary of preplanned comparisons for all groups are shown in Figure 7. On P1 and P10, quipazine-treated subjects exposed to ROM restriction showed significant decreases in the center area with forelimbs between baseline (T4) and the following times: beginning and end of ROM restriction (T5 and T19), and beginning and end of post-ROM restriction (T20 and T34). For P1 saline-treated subjects receiving ROM restriction there was a significant decrease in the center area with forelimbs between baseline and the beginning of ROM restriction. For P10 saline-treated subjects that received ROM restriction there were significant decreases in the distal and center areas and increases in front area between the baseline and the beginning and end of ROM restriction. There was a significant decrease in center and increase in front between the end of ROM restriction (T19) and the beginning of the post-ROM restriction period (T20). There also was an increase in the back area between the baseline and the beginning of ROM restriction (T5), and a decrease in the back area between the beginning and end of ROM restriction (T5 and T19).

Figure 7.

Summary of changes in forelimb trajectories for P1 and P10 rats. Changes in forelimb trajectories are shown for subjects in each drug-ROM restriction condition, at P1 (A) and P10 (B). The shaded regions reflect an increase (white), maintenance (gray), or decrease (black) from baseline within that trajectory area during the designated time period.

3.2.3 Hindlimb Trajectories

For time spent in the distal area with the hindlimbs there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 9.57, p = .003], drug [F(1, 56) = 22.64, p < .001], ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 70.69, p < .001] and time [F(6, 336) = 104.21, p < .001], 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 2.10, p = .05], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 15.791, p < .001], ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 59.5, p < .001], age and drug [F(1, 56) = 4.22, p = .05] and drug and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 17.93, p < .001], and 3-way interactions between age, drug and time [F(6, 336) = 3.96, p = .001], and drug, ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 9.08, p < .001]. P1 subjects showed less time in the distal area than P10 subjects, quipazine-treated subjects showed less time in the distal area than saline-treated subjects, subjects that received ROM restriction showed less time in the distal area than non-restricted subjects, and time in the distal area decreased after baseline. These effects can be seen in Figure 8. On P1and P10, subjects treated with quipazine spent significantly less time in the distal area with the hindlimbs from T20-T34 compared to saline-treated subjects. Thus, quipazine-treated subjects at both ages showed less time in the distal area during the last 15 minutes of the test session. Quipazine-treated subjects showed more time in the distal area at T5, T12 and T34 on P10 compared to on P1. Saline-treated subjects showed significantly more time in the distal area at T4 on P10 compared to on P1. Furthermore, quipazine-treated subjects that experienced ROM restriction showed less time in the distal area during the ROM restriction period (T5-T19) (Figure 8A and 8E) than non-restricted subjects (Figure 8B and 8F). Saline-treated subjects that experienced ROM restriction showed less time in the distal area during the ROM restriction period (T5-T19) and at T20 and T34 (Figure 8C and 8G). Thus, in both drug groups, subjects that had ROM restriction spent significantly less time in the distal area during the ROM restriction period compared to subjects without ROM restriction. Decreases in the time spent in the distal area also were seen during the post-ROM restriction period in saline subjects that experienced ROM restriction.

Figure 8.

Dorsal-ventral hindlimb trajectories for P1 and P10 rats by drug and ROM restriction condition. Graphs show duration of time spent in the distal and proximal trajectory areas for 1-min sections during baseline, ROM restriction period, and the post-ROM restriction period. In the top half of the figure, data are shown for quipazine-treated (A,B) and saline-treated (C,D) rats on P1 that experienced ROM restriction or were non-restricted, respectively. In the bottom half of the figure, data are shown for quipazine-treated (E,F) and saline-treated (G,H) rats on P10 that experienced ROM restriction or were non-restricted, respectively. Points show means; vertical lines are SEM.

For time spent in the front area for the hindlimbs there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 55.06, p < .001], ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 24.83, p < .001] and time [F(6, 336) = 18.54, p < .001]. There were 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 6.93, p < .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 5.30, p < .001], ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 13.81, p < .001], age and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 4.44, p = .04] and drug and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 19.69, p < .001], and 3-way interactions between age, ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 2.53, p = .02], drug, ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 7.70, p < .001], and age, drug and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 5.22, p = .02]. P1 subjects spent more time in front with the hindlimbs compared to P10 subjects, subjects that received ROM restriction showed more time in front than non-restricted subjects, and time in front increased after baseline. On P1, subjects that received ROM restriction (Figure 9A and 9C) spent more time in the front area with the hindlimbs from T12-T20 and approached significance at T5 (p = .06), compared to subjects that did not receive restriction (Figure 9B and 9D). On P10, subjects that received ROM restriction spent more time in the front area at T12 and T19 (Figure 9E and 9G) compared to non-restricted subjects (Figure 9F and 9H). Additionally, subjects in both ROM conditions showed significantly more time in the front area from T5-T34 on P1 compared to on P10. Thus, subjects at both ages that received ROM restriction showed more time in the front area during the ROM restriction period. More time in the front area also was seen in P1 subjects at the beginning of the post-ROM restriction period. Saline-treated subjects with ROM restriction spent more time in the front area with the hindlimbs from T5-T20 than non-restricted subjects. For quipazine-treated subjects that experienced ROM restriction, more time in the front area with the hindlimbs approached significance at T19 (p = .06) compared to subjects that did not receive restriction. Thus, experience with ROM restriction increased the time saline-treated subjects spent in the front area for the hindlimbs during the ROM restriction and the beginning of the post ROM restriction period (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Rostral-caudal hindlimb trajectories for P1 and P10 rats by drug and ROM restriction condition. Graphs show duration of time spent in the front, center, and back trajectory areas for 1-min sections during baseline, ROM restriction period, and the post-ROM restriction period. In the top half of the figure, data are shown for quipazine-treated (A,B) and saline-treated (C,D) rats on P1 that experienced ROM restriction or were non-restricted, respectively. In the bottom half of the figure, data are shown for quipazine-treated (E,F) and saline-treated (G,H) rats on P10 that experienced ROM restriction or were non-restricted, respectively. Points show means; vertical lines are SEM.

For time spent in the center area there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 9.78, p = .003], drug [F(1, 56) = 8.67, p = .005], ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 32.52, p < .001], and time [F(6, 336) = 37.26, p < .001]. There were 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 3.99, p = .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 4.31, p < .001], ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 17.31, p < .001], and drug and ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 13.21, p = .001], and 3-way interactions between age, drug and time [F(6, 336) = 2.65, p = .02], and drug, ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 7.59, p < .001]. P1 subjects spent less time in the center area compared to P10 subjects, quipazine-treated subjects spent less time in center compared to saline subjects, subjects that received ROM restriction showed less time in center compared to non-restricted subjects, and time in center decreased after baseline. On P1, quipazine-treated subjects spent less time in the center at T27 and T34, compared to saline-treated subjects. On P10, quipazine-treated subjects spent less time in center at T12 and from T20-T34, compared to saline subjects. Thus, at both ages quipazine-treated subjects showed significantly less time in the center area with the hindlimbs during the second half of the test session, compared to saline subjects. For saline-treated subjects that experienced ROM restriction, subjects spent less time in the center area during ROM restriction (T5-T19) and at the beginning of the post-ROM restriction period (T20) compared to quipazine-treated subjects that received ROM restriction. Data are shown in Figure 9.

For time spent in the back area with the hindlimbs there were main effects of age [F(1, 56) = 12.50, p = .001], drug [F(1, 56) = 31.72, p < .001], ROM condition [F(1, 56) = 5.95, p < .001], and time [F(6, 336) = 15.55, p < .001], 2-way interactions between age and time [F(6, 336) = 6.88, p < .001], drug and time [F(6, 336) = 7.87, p < .001], and ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 3.02, p = .007], and 3-way interactions between age, drug and time [F(6, 336) = 2.83, p = .01], and age, ROM condition and time [F(6, 336) = 3.92, p = .001]. P10 subjects spent more time in the back area with the hindlimbs compared to P1 subjects, quipazine-treated subjects spent more time in the back compared to saline-treated subjects, subjects exposed to ROM restriction spent more time in the back compared to non-restricted subjects, and time in back increased after baseline. On P1, quipazine-treated subjects spent more time in the back area from T5-T34, compared to saline-treated subjects. On P10, quipazine-treated subjects spent more time in the back from T12-T34, compared to saline subjects. Thus, subjects treated with quipazine at both ages (Figure 9A, 9B, 9E, and 9F) showed more time in the back area with the hindlimbs than saline-treated subjects (Figure 9C, 9D, 9G, and 9H), following T12. On P10, subjects that received ROM restriction spent more time in the back area at T5 and approached significance at T12 (p = .06) compared to subjects that did not receive restriction. Also, P10 subjects that received ROM showed significantly more time in the back area at T5 and T12 than P1 subjects that received ROM restriction. No differences were seen between ROM conditions for P1 subjects.

Summary. During the ROM restriction period (T5-T19), experience with ROM restriction decreased the time subjects spent in the distal and center areas. Further, saline-treated subjects that experienced ROM restriction showed an increase in the front area and a decrease in the center area from T5-T20. On P1, subjects that experienced ROM restriction showed an increase in the front area from T12-T20. On P10, subjects that experienced ROM restriction showed an increase in the back area at T5 and an increase in the front area from T12-T19.

3.2.4 Hindlimb Trajectories, Preplanned Comparisons

A summary of changes in hindlimb trajectories are shown in Figure 10. On P1, quipazine-treated subjects that experienced ROM restriction showed significant decreases in distal and center areas with the hindlimbs between baseline (T4) and the following times: beginning and end of ROM restriction (T5 and T19), and the beginning and end of post-ROM restriction (T20 and T34). There was an increase in the distal area between the end of the ROM restriction period and the beginning of the post-ROM restriction period. There also was an increase in the front area between baseline and the end of ROM restriction. On P10, quipazine-treated subjects that experienced ROM restriction showed significant decreases in the distal area with the hindlimbs between baseline and the beginning and end of ROM restriction (T5 and T19). There was a significant decrease for time in the back area between the second and third time points of the ROM restriction period (T12 and T19).

Figure 10.

Summary of changes in hindlimb trajectories for P1 and P10 rats. Changes in hindlimb trajectories are shown for subjects in each drug-ROM restriction condition, at P1 (A) and P10 (B). The shaded regions reflect an increase (white), maintenance (gray), or decrease (black) from baseline within that trajectory area during the designated time period.

On P1, saline-treated subjects that received ROM restriction showed significant decreases in the distal and center areas and increases in the front areas between baseline and the beginning and end of ROM restriction. There was a significant increase in the distal area between the end of ROM restriction and the beginning of the post-ROM restriction period. On P10, saline-treated subjects that received ROM restriction showed significant decreases in the distal area between the baseline and the beginning of ROM restriction, end of ROM restriction, and the beginning of the post-ROM restriction period. There was a significant increase in the center and back areas between the end of ROM restriction and the beginning of the post-ROM restriction period. There were significant decreases in the center area between baseline and the beginning of ROM restriction (T5) and end of ROM restriction (T19).

4. Discussion

The present study showed that developing rats adapted their motor behavior to altered sensory feedback (i.e., ROM restriction). Real-time effects of ROM restriction were seen for frequency of forelimb stepping and limb trajectories in both P1 and P10 pups. The real-time effects seen in response to ROM restriction in the forelimbs is similar to a previous study which showed that newborn rats adapt to a stiff, Plexiglas substrate by altering (i.e., suppressing) forelimb movement during the peak of quipazine-induced stepping behavior [16]. In that study, the Plexiglas plate was placed at a distance of 80% of limb length. Since pups could easily avoid the substrate in that study, ROM restriction was not imposed. Furthermore, that study did not evaluate the possibility of persistent effects of the sensory perturbation, or developmental changes in behavior. Both real-time and persistent effects were observed in limb trajectories for P1 and P10 pups that received ROM restriction. This coincides with research in young humans and animals that shows that immature locomotor systems can adapt intralimb coordination to sensory feedback both during and after training [22, 29, 31, 32].

4.1 Developmental Differences in Quipazine-Induced Stepping for P1 and P10 Rats

Both P1 and P10 pups showed an increase in coordinated movement (i.e., alternated and synchronized steps) as a result of treatment with the 5-HT2 agonist quipazine, which has been shown in previous research with perinatal and adult rats to primarily increase alternated stepping [11, 12, 15, 16, 31]. Interestingly, a difference was found in the number and time course of quipazine-induced steps between P1 and P10, with P10 pups showing fewer steps and only maintaining a high frequency of steps during the first 15 minutes following treatment with quipazine, compared to P1 pups.

One explanation for this finding could be that there is a difference in drug turnover between the two ages. Thus, the frequency of steps may be lower in P10 pups because the drug wears off sooner at this age. However, this is unlikely since the drug induced fairly high percentages of coordinated movement throughout the test period at both ages (about 70% of total movements were alternated steps). This suggests then that the decrease in stepping for older pups is simply due to depressed movement overall (but not quipazine-induced interlimb coordination). Evidence of this is seen when the graphs for total movements (Figures 1 and 3) are compared to the graphs for alternated stepping (Figures 2 and 4).

Differences in overall movement frequency between younger and older pups perhaps may be explained by differences in supraspinal regulation of limb activity. Between P1 and P10, the spinal cord is greatly changing. For example, P1 pups lack input from the corticospinal tract to the cervical and lumbar spinal cord, and have fewer functional inputs from other supraspinal tracts as well, compared to P10 pups [8, 33, 35]. These supraspinal inputs may serve, in part, to inhibit activity. For example, rats show little to no descending inhibition to dorsal horn cells until P9-10 [36]. Also, there is a change in the regulation of spontaneous limb movements during the early postnatal period that is concurrent with the rapid descent of supraspinal inputs to the spinal cord [37, 38]. Thus, older pups may have more inhibitory signals from supraspinal inputs that may have affected the amount of overall movement seen in the present study. Future studies should examine the possible role of the spinal cord and supraspinal mechanisms in the regulation of sensory feedback during early development.

4.2 Effects of ROM Restriction on Stepping

Effects of ROM restriction were found on forelimb stepping during the period of restriction. In general, experience with ROM restriction depressed the frequency of forelimb steps during the period in which it was imposed for P1 and P10 subjects. This replicates a previous study, which showed that P1 subjects decreased their forelimb stepping behavior while suspended over a Plexiglas substrate [16], and a recent study showing that spinal cord transected P10 rats (low thoracic spinal cord transection happened at P1) decrease their stepping behavior as well [31].

Exactly why ROM restriction appears to reduce the frequency of stepping is unclear. In fact, one might expect that phasic feedback from the limbs would help to entrain the locomotor rhythm and increase alternated stepping [i.e., 39, 40]. But that was not observed; instead ROM restriction decreased stepping. Perhaps ROM restriction may be interfering with interlimb coordination first by interfering with intralimb coordination. That is, pups that experienced ROM restriction were forced to make adaptations to the perturbation by changing how individual limbs used the available movement space. In making such intralimb adaptations to the ROM restriction, interlimb coordination may have been compromised. Perhaps if the period of exposure to the ROM restriction were increased, we might find first a reduction in stepping, followed by an increase or plateau as the subject gradually adapts to the perturbation.

There was not strong evidence for persistent effects of ROM restriction on step frequency in this study. A persistent effect of the perturbation on forelimb stepping was seen only immediately after the ROM restriction period for synchronized steps and percent synchronized steps. This effect appears to be due to time, rather than to ROM restriction per se, considering that it was only seen in the non-ROM restricted group. Also, given that there was considerable variability for synchronized stepping, particularly within the non-ROM restricted group, it is unclear whether this effect would replicate.

Research with human infants has shown that young infants show real-time adaptations during stepping on a treadmill, but do not demonstrate reliable persistent adaptations until around 9 months of age [29]. Thus, the age of pups in this study may be too young to show reliable lasting effects of the perturbation on locomotor activity. Research that has looked at translating age across species equates our P1-10 rat pups with second-trimester human fetuses in terms of brain development [41], and with 9-10 month old human infants in terms of locomotor development [42]. However, other studies have shown lasting effects of sensorimotor perturbations on interlimb coordination in perinatal rats [11, 28, 32]. So another possibility for the lack of persistent effects in the current study may be due to the short (15-min) ROM restriction period. If the pups were allowed more time to experience the ROM restriction, persistent effects of the ROM restriction may have emerged. In limb yoking studies with perinatal rats, exposure time to the interlimb yoke is typically 30 minutes [28, 32]. In the present study, we chose to evaluate the real-time and persistent effects of ROM restriction during the peak of quipazine-induced stepping. Thirty minutes after treatment with quipazine, stepping behavior starts to decline [16], thus making changes in behavior during more prolonged testing sessions more difficult to interpret.

4.3 Real-Time and Persistent Effects of ROM Restriction on Limb Trajectories

During ROM restriction, the perturbation blocked part of the center and distal limb trajectory areas. Thus at P1 and P10, ROM-restricted subjects produced fewer limb movements in the center and distal limb trajectory areas. As a consequence, pups tended to move their forelimbs mostly to the front area and their hindlimbs more-or-less equally to the front and back areas, during ROM restriction. Hindlimb adaptations appeared a little more drastic compared to forelimb adaptations (i.e., much less time was spent in center and distal areas), on P1 compared to on P10. Thus, the ROM restriction perturbation imposed a period of altered intralimb movement strategies. As noted above, these intralimb adaptations may have interfered with interlimb coordination. Persistent effects of ROM restriction mostly were seen immediately after the ROM restriction was removed in both forelimbs and hindlimbs, but often did not persist to the end of the test session. If this was due to the age of the subjects or duration of exposure to ROM restriction remains to be determined.

One reason the limbs adapted by mainly moving to the front of the subject may be related to the differential effect of serotonergic stimulation on flexor and extensor motor output. Quipazine has been shown to preferentially increase flexor motor output in spinal adult rats [43], whereas serotonin depletion increases limb extension [44]. In the present study the limbs could be flexed and remain in front of the subject, but to move the limbs to the back would entail significant extensor activity. Hence moving the limbs more to the front trajectory space may be due to a stronger effect of quipazine on flexor activity relative to extensor activity (quipazine-treated subjects). Additionally, some changes in limb trajectories from baseline also were observed to occur in quipazine-treated pups that did not experience ROM restriction. Specifically, these pups showed a decrease in the center and distal areas as well. This likely happened because quipazine increased the amount of stepping that these pups engaged in. Stepping involves alternated limb flexion and extension, with the limbs typically making large limb excursions. Thus, it should be expected that quipazine-treated subjects would utilize their movement space differently from baseline.

4.4 Implications

Findings from this study suggest that sensory feedback modulates locomotor activity during the period of development in which the neural mechanisms of locomotion are undergoing rapid development. We found effects of ROM restriction on interlimb and intralimb coordination, in a relatively brief experimental session (35 minutes). However, under normal circumstances, newborn rats likely experience conditions similar to ROM restriction in the nest environment. For instance, if pups are in a prone, resting posture on a surface, their weak muscles and poor postural control will likely prevent them from making large limb excursions, just as the ROM restriction perturbation prevented certain limb excursions from happening. Also, pups would likely experience some kind of ROM restriction in a nest environment where their body is pressed next to siblings, or during nursing when the dam is lying on top of them. Thus, normally occurring sensorimotor feedback and experiences may shape locomotor activity and mechanisms during typical development.

Whether or not an increase in sensory feedback would accelerate locomotor development may depend on the type of sensory feedback. For example, the current study saw a decrease in locomotor activity during a session of increased sensory feedback (i.e., ROM restriction). Brumley et al. (2012) [16] showed similar decreases to a stiff substrate, but also observed increases in locomotor activity during experience with an elastic substrate. Studies in human infants with developmental motor delays and individuals with spinal cord injuries have been shown to increase their locomotor behaviors in response to treadmill training [45, 46]. Therefore, the type of sensory feedback also may be important for shaping later locomotor behaviors. This may be an important consideration when choosing the most appropriate therapeutic intervention for an individual with motor dysfunction. More research needs to be done to better understand the sensory mechanisms involved in facilitation or suppression of locomotor behavior. In order to understand locomotion acquisition and maintenance, it is essential that we understand the role of early sensory experience on locomotor development.

Highlights.

We examined ROM (range of motion) restriction on stepping in neonatal rats.

Stepping in P1 and P10 rats was induced with the 5-HT agonist quipazine.

Stepping and limb trajectories were altered during the period of ROM restriction.

Persistent effects of ROM restriction was found for intralimb movement trajectories.

5. Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH grant Nos. 1R15HD062980-01, P20 RR016454, and P20 GM103408.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Muir GD. Early ontogeny of locomotor behavior: A comparison between altricial and precocial animals. Brain Research Bulletin. 2000;53(5):719–26. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kleven GA, Lane MS, Robinson SR. Development of interlimb movement synchrony in the rat fetus. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2004;118(4):835–44. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.4.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bekoff A, Lau B. Interlimb coordination in 20-day-old rat fetuses. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 1980;214:173–5. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402140207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Narayanan CH, Fox MW, Hamburger V. Prenatal development of spontaneous and evoked activity in the rat (rattus norvegigus albinus) Behaviour. 1971;40(1):100–33. doi: 10.1163/156853971x00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gramsbergen A. Posture and locomotion in the rat: Independent or interdependent development? Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 1998;22(4):547–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Altman J, Sudarshan K. Postnatal development of locomotion in the laboratory rat. Animal Behavior. 1975;23:896–920. doi: 10.1016/0003-3472(75)90114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jamon M, Clarac F. Early walking in the neonatal rat: A kinematic study. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1998;112(5):1218–28. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.5.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Geisler HC, Westerga J, Gramsbergen A. Development of posture in the rat. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis. 1993;53:517–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Westerga J, Gramsbergen A. Development of locomotion in the rat: The significance of early movement. Early Human Development. 1993;34:89–100. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(93)90044-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fady JC, Jamon M, Clarac F. Early olfactory-induced rhythmic limb activity in the newborn rat. Developmental Brain Research. 1998;108:111–23. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Brumley MR, Robinson SR. Experience in the perinatal development of action systems. In: Blumberg MS, Freeman JH, Robinson SR, editors. Oxford Handbook of Developmental Behavioral Neuroscience. Oxford University Press; New York: 2010. pp. 181–209. [Google Scholar]

- [12].McEwen ML, Van Hartesveldt C, Stehouwer DJ. L-DOPA and quipazine elicit air-stepping in neonatal rats with spinal cord transections. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1997;111(4):825–33. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.4.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].McEwen ML, Van Hartesveldt C, Stehouwer DJ. A kinematic comparison of L-DOPA-induced air-stepping and swimming in developing rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 1997;30:313–27. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(199705)30:4<313::aid-dev5>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Meisel RL, Rakerd B. Induction of hindlimb stepping movements in rats spinally transected as adults or as neonates. Brain Research. 1982;240:353–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brumley MR, Robinson SR. The serotonergic agonists quipazine, CGS-12066A, and α-methylserotonin alter motor activity and induce hindlimb stepping in the intact and spinal rat fetus. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119(3):821–33. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.3.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brumley MR, Roberto ME, Strain MM. Sensory feedback modulates quipazine-induced behavior in the newborn rat. Behavioral Brain Research. 2012;229:257–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ung RV, Landry ES, Rouleau P, Lapointe NP, Rouillard C, Guertin PA. Role of spinal 5-HT2 receptor subtypes in quipazine-induced hindlimb movements after a low-thoracic spinal cord transection. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:2231–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vaal J, van Soest AJ, Hopkins B. Spontaneous kicking behavior in infants: Age-related effects of unilateral weighting. Developmental Psychobiology. 2000;36:111–22. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(200003)36:2<111::aid-dev3>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Thelen E. Three-month-old infants can learn task-specific patterns interlimb coordination. Psychological Science. 1994;5(5):280–4. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ulrich BD, Ulrich DA, Angulo-Kinzler R, Chapman DD. Sensitivity of infants with and without down syndrome to intrinsic dynamics. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 1997;68:10–9. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1997.10608862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Thelen E. Three-month-old infants can learn task-specific patterns of interlimb coordination. Psychological Science. 1987;5:280–5. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lam T, Wolstenhome C, Yang JF. How do infants adapt to loading of the limb during the swing phase of stepping? Journal of Neurophysiology. 2003;89:1920–8. doi: 10.1152/jn.01030.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Brumley MR, Robsinson SR. Sensory feedback alters spontaneous limb movements in newborn rats: Effects of unilateral forelimb weighting. Developmental Psychobiology. 2013;55(4):323–33. doi: 10.1002/dev.21031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Stephens MJ, Yang JF. Loading during the stance phase of walking in humans increases the extensor EMG amplitude but does not change the duration of the step cycle. Experimental Brain Research. 1999;124:363–70. doi: 10.1007/s002210050633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yang JF, Lamont EV, Pang MYC. Split-belt treadmill stepping in infants suggests autonomous pattern generators for the left and right leg in humans. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:6869–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1765-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bradley NS, Sebelski C. Ankle restraint modifies motility at E12 in chick embryos. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;83:431–40. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Blaszczyk JW, Dobrzecka C. Alteration in the pattern of locomotion following a partial movement restraint in puppies. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis. 1989;49:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Robinson SR. Conjugate limb coordination after experience with an interlimb yoke: Evidence for motor learning in the rat fetus. Developmental Psychobiology. 2005;47:328–44. doi: 10.1002/dev.20103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Pang MYC, Lam T, Yang JF. Infants adapt their stepping to repeated trip-inducing stimuli. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2003;90:2731–40. doi: 10.1152/jn.00407.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fitzgerald M, Jennings E. The postnatal development of spinal sensory processing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999;96:7719–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Strain MM, Kauer SD, Kao T, Brumley MR. Inter- and intralimb adaptations to a sensory perturbation during activation of the serotonin system after a low spinal cord transection in neonatal rats. Frontiers in Neural Circuits. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00080. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Robinson SR, Kleven GA, Brumley MR. Prenatal development of interlimb motor learning in the rat fetus. Infancy. 2008;13:204–28. doi: 10.1080/15250000802004288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Clarac F, Vinay L, Cazalets JR, Fady JC, Jamon M. Role of gravity in the development of posture and locomotion in the neonatal rat. Brain Research Reviews. 1998;28:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Institute for Laboratory Animal Research . Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th The National Academic Press; Washington DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Vinay L, Brocard F, Clarac F, Norreel JC, Pearlstein E, Pflieger JF. Development of posture and locomotion: An interplay of endogenously generated activities and neurotrophic action by descending pathways. Brain Research Reviews. 2002;40:118–29. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00195-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fitzgerald M, Koltzenburg M. The functional development of descending inhibitory pathways in the dorsolateral funiculus of the newborn rat spinal cord. Developmental Brain Research. 1986;24:261–70. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(86)90194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Karlsson KA, Gall AJ, Mohns EJ, Seelke AM, Blumberg MS. The neural substrates of infant sleep in rats. PLOS Biology. 2005;3:e143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kreider JC, Blumberg MS. Mesopontine contribution to the expression of active “twitch” sleep in decerebrated week-old rats. Brain Research. 2000;875:149–59. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02518-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pearson KG. Generating the walking gait: role of sensory feedback. Progress in Brain Research. 2004;143:123–9. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)43012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Saltiel P, Rossignol S. Critical points in the forelimb fictive locomotor cycle and motor coordination: effects of phasic retractions and protractions of the shoulder in the cat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;92:1342–56. doi: 10.1152/jn.00564.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Clancy B, Darlington RB, Finay BL. Translating developmental time across mammalian species. Neuroscience. 2001;105(1):7–17. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Vinay L, Ben-Mabrouk F, Brocard F, Clarac F, Jean-Xavier C, Pearlstein E, Pflieger JF. Perinatal development of the motor systems involved in postural control. Neural Plasticity. 2005;12:131–9. doi: 10.1155/NP.2005.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chopek JW, MacDonell CW, Power KE, Gardiner K, Gardiner PF. Removal of supraspinal input reveals a difference in the flexor and extensor monosynaptic reflex response to quipazine independent of motoneuron excitation. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2013;109:2056–63. doi: 10.1152/jn.00405.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Pflieger JF, Clarac F, Vinay L. Postural modifications and neuronal excitability changes induced by a short-term serotonin depletion during neonatal development in the rat. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:5108–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05108.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Teulier C, Smith BA, Kubo M, Chang CL, Moerchen V, Murazko K, Ulrich BD. Stepping responses of infants with myelomeningocele when supported on a motorized treadmill. Physical Therapy. 2009;89(1):60–72. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ulrich DA, Lloyd MC, Tiernan CW, Looper JE, Angulo-Barroso RM. Effects of intensity of treadmill training on developmental outcomes and stepping in infants with Down syndrome: A randomized trial. Physical Therapy. 2008;88:114–22. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]