Abstract

The Krüppel like factor 6 (KLF6) gene encodes multiple protein isoforms derived from alternative mRNA splicing, most of which are intimately involved in hepatocarcinogenesis and tumor progression. Recent bioinformatics analysis shows that alternative mRNA splicing of the KLF6 gene produces around 16 alternatively spliced variants with divergent or even opposing functions. Intriguingly, the full-length KLF6 (KLF6-FL) is a tumor suppressor gene frequently inactivated in liver cancer, whereas KLF6 splice variant 1 (KLF6-SV1) is an oncogenic isoform with antagonistic function against KLF6-FL. Compelling evidence indicates that miRNA, the small endogenous non-coding RNA (ncRNA), acts as a vital player in modulating a variety of cellular biological processes through targeting different mRNA regions of protein-coding genes. To identify the potential miRNAs specifically targeting KLF6-FL, we utilized bioinformatics analysis in combination with the luciferase reporter assays and screened out two miRNAs, namely miR-210 and miR-1301, specifically targeted the tumor suppressive KLF6-FL rather than the oncogenic KLF6-SV1. Our in vitro experiments demonstrated that stable expression of KLF6-FL inhibited cell proliferation, migration and angiogenesis while overexpression of miR-1301 promoted cell migration and angiogenesis. Further experiments demonstrated that miR-1301 was highly expressed in liver cancer cell lines as well as clinical specimens and we also identified the potential methylation and histone acetylation for miR-1301 gene. To sum up, our findings unveiled a novel molecular mechanism that specific miRNAs promoted tumorigenesis by targeting the tumor suppressive isoform KLF6-FL rather than its oncogenic isoform KLF6-SV1.

Keywords: Alternative splicing, KLF6, miRNA

Introduction

The Krüppel like factor 6 (KLF6), a member of Sp1/KLF family with three C2H2 zinc fingers in its C-terminal, directly binds to target sites in human genome through interacting with GC-rich element or CACCC motif in responsive promoter region.1-3 KLF6 is ubiquitously expressed in a variety of human tissues and orchestrated multiple cellular events such as cell cycle arrest,4-7 vascular remodeling,8,9 adipogenesis10 and programmed cell death.11,12 This general role is partially through its regulation of various target genes, including p21, iNOS, Keratins-4 and -12, MDM2, MMP-9, TGFβ1, Dlk1, Types I and II TGFβ receptors, PPARα, c-Myc and E-cadherin.1,2,7,8 Mounting evidence also identified KLF6 as a tumor suppressive gene that is frequently inactivated in multiple types of human cancer due to somatic mutation,13-17 loss of heterozygosity13-17 and promoter hypermethylation.18,19

Recently, three alternatively spliced KLF6 variants termed SV1, SV2, and SV3 were identified in a large-scale study of prostate cancer patients. Full-length KLF6 and KLF-SV3 predominately localizes to the nucleus because of the retention of nuclear localization signal (NLS) in exon 2, whereas spliced variants KLF6-SV1 and KLF6-SV2 are mainly mislocalized to the cytoplasm due to the absence of NLS, resulting in reduced p21 expression and enhanced cell proliferation.20 The functional role of KLF6-SV1 in tumorigenesis is most well documented among the three KLF6 spliced variants since it is frequently highly expressed in multiple types of human malignant cancer and its elevated expression has been associated with poor prognosis and reduced survival in cancer patients.16,21-24 Growing evidence showed that elevated expression of KLF-SV1 variant accelerated cancer metastasis, progression and mortality partially through its antagonistic function against KLF6-FL. Furthermore, an increased KLF6-SV1/KLF6-FL mRNA ratio has been verified in liver cancer samples.16,21,25 Recent studies unveiled that the Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and its downstream PI3K/Akt signaling pathway play a role in controlling KLF6 splicing selection.21,25 However, knowledge about KLF6 alternative splicing selection remains elusive in a large number of tumors, particularly in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

In the past decades, encouraging evidence verified that most human protein-coding genes could encode at least two mRNA isoforms through alternative mRNA splicing, an intriguing biological process by which functionally diverse even opposing protein isoforms can be modulated through different regulatory mechanisms. Dysfunction of alternative mRNA splicing may result in a variety of human diseases, including metabolic disorder, neurodegenerative disease and cancer.26,27 Although recent advances in high-throughput DNA sequencing technologies28 have shed light on the molecular mechanism for human alternative mRNA splicing and encouraging progress has been achieved, however, the detailed mechanism in alternative mRNA splicing remains obscure.

Over the past decade, miRNAs, a group of small but functional non-coding RNA, emerged as a novel player in gene regulation. MiRNAs belong to a class of phylogenetically conserved ncRNAs coordinating diverse cellular activities through translational inhibition or mRNA destabilization through mutual interaction with the protein-coding genes.29,30 Considerable studies indicated that alternations of miRNA network may lead to the initiation and progression of HCC.31,32 Indeed, intensive studies have provided novel insights into the functional role of miRNAs in hepatocarcinogenesis and the application of miRNA expression profiling in cancer research significantly extended our knowledge about the molecular mechanism of HCC. Unfortunately, the missing link between miRNA and KLF6 alternative splicing selection has not yet been well defined. Attempts have been made to identify the miRNAs that potentially regulate KLF6 gene expression, however, these studies mainly focused on the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) of KLF6 but not the protein-coding region with splice sites.33,34 Hence, the regulatory role of miRNA in KLF6 alternative splicing selection need further elucidation by taking advantage of new molecular approaches.

In this study, we developed a novel approach using bioinformatics prediction in conjunction with the luciferase reporter assays and screened out two miRNAs targeting tumor suppressive KLF6-FL but not oncogenic spliced variants KLF6-SV1. Among the newly identified candidate miRNAs, miR-1301 was chosen for further investigation because of its undefined role in hepatocarcinogenesis. With in vitro model, the functional impacts of miR-1301 in tumorigenesis and the underlying molecular mechanisms were assessed. To sum up, this study describes a novel mechanism by which miRNA contributes to hepatocarcinogenesis though targeting the tumor suppressive isoform rather than the oncogenic spliced variants.

Results

Ectopic KLF6 expression represses in vitro growth of liver cancer cells

To further manifest the biological implication of KLF6-FL in cell growth, we generated KLF6 stable transfectants in HepG2 and PLC/PRF/5 hepatoma cells by retroviral transduction and the KLF6-FL overexpression was confirmed by RT-PCR and western blot analysis (Fig. S1). In parallel, two control stable transfectants were established through retroviral infection with the empty vector. The anti-proliferative function of KLF6 was assessed in these stable transfectants by XTT proliferation assays, colony formation assays, flow cytometry as well as soft agar assays. All generated HepG2-KLF6 and PLC5-KLF6 stable cell lines proliferated substantially slower than their respective control stable transfectants (Fig. 1A and 1B). Conversely, loss of function assays verified that reduced expression of KLF6 increased cell proliferation (Fig. S2 and S3). Given that ectopic KLF6 expression suppressed liver cancer cell growth and it has been well established that KLF6 inhibited G1 to S phase transition via upregulation of p21 and perturbation of Cyclin D1/CDK4 complexes,4-6 we next monitored the status of cell cycle progression using flow cytometry. And noticeable cell cycle arrest in PLC5-KLF6 and HepG2-KLF6 stable transfectants were observed (Fig. 1C and 1D). To further elucidate the impact of KLF6 in cell cycle progression, RT-PCR was conducted and significant upregulation of p21 was observed but other G1/S phase marker genes remained unchanged (Fig. S4). Soft agar assays for the assessment of anchorage-independent growth demonstrated that KLF6 stable transfectants formed less and smaller colonies as compared with those formed by their parallel stable transfectants overexpressing KLF6 (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1. Ectopic KLF6 expression impaired in vitro growth of liver cancer cells. (A) Equal numbers of KLF6 and vector-transfected stable cells were seeded into 96 well plates and cell growth was quantified by XTT assays for 4 d. Reduced cell proliferation was observed in KLF6 stable transfectants. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (B) KLF6 stable transfectants and respective parental cells were plated in 6 well plate and colonies were stained by crystal violet after 10 d. Impaired colony formation ability was found in KLF6 stable transfectants. **P < 0.01. (C&D) After serum starvation treatment, KLF6 stable transfectants and respective parental cells were harvested and subjected to cell cycle analysis. Repression on G1/S phase transition was observed in PLC/PRF/5-KLF6 and HepG2-KLF6 cells. ***P < 0.001. (E) To monitor anchorage-independent growth of liver cancer cells, low intensity of KLF6 stable transfectants and respective parental cells were seeded into soft agar and visualized by crystal violet staining. The representative PLC/PRF/5-KLF6 and HepG2-KLF6 cells formed significantly less colonies in soft agar, as compared with parental cells. **P < 0.01 ***P < 0.001.

To gain insights into the function of KLF6 in apoptosis, Caspase 3 and PARP, the effectors of apoptosis, were evaluated in KLF6-overexpressing stable cell lines using western blot. However, no significant change was observed in the results from western blot (Fig. S5A). We next monitored whether KLF6 could sensitize these two cell lines to chemotherapeutic drugs. However, after treatment with chemotherapeutic drugs 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) and Cisplatin, no significant change was displayed in KLF6 stable transfectants and their corresponding control transfectants in XTT assays (data not shown). Furthermore, we evaluated the expression of Caspase 3 and PARP in these two cell lines. However, western blot did not present significant change in KLF6 stable transfectants and their corresponding control transfectants (Fig.. S5B and 5C). Given that KLF6-FL and KLF6-SV1 have opposing roles in regulating epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), we also analyzed the mRNA levels of several EMT relevant marker genes using RT-PCR. Consistent with previous reported findings, overexpression of KLF6-SV1 significantly promoted the expression of mesenchymal marker genes such as Vimentin, ZEB1, ZEB2 and Snail1, whereas ectopic expression of KLF6-FL suppressed epithelial marker gene E-cadherin (Fig. S6).

Ectopic KLF6 expression attenuates angiogenesis and cell motility

Previous study reported that ovarian carcinoma SKOV-3 cells stably expressing siRNA against KLF6 altered the expression and secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a critical angiogentic factor.35 However, current knowledge is limited about the correlation between KLF6 and angiogenesis. Therefore, we examined the angiogentic ability of KLF6 in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC) transiently overexpressing KLF6. As revealed in the tube formation assays, overexpression of KLF6 profoundly impaired angiogenesis in HUVEC cells (Fig. 2A). In further support of tube formation assays, a panel of angiogenesis-related genes, including VEGF, Angiopoietin-2 (ANG2), Tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin-like and EGF-like domains 1 (Tie1), Tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin-like and EGF-like domains 2 (Tie2) and Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2) were all profoundly downregulated in KLF6-overexpressing cell lines (Fig. 2B and 2C). The wound-healing assays demonstrated that KLF6-overexpressing stable transfectants exhibited retarded migration toward the wound as compared with the control groups (Fig. 2D and 2E).

Figure 2. Ectopic KLF6 expression inhibited tube formation and cell motility. (A) Equal numbers of KLF6 and vector-transfected HUVEC cells were seeded into 96 well plates and the ability of endothelial cell tube formation was quantified by measuring the length of the capillary-like structures by Image J. Impaired tube formation was observed in HUVEC cells after overexpression of KLF6. *P < 0.05. (B&C) Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the expression profiles of angiogenesis marker genes. Reduced expression of angiogenesis marker genes was observed in PLC/PRF/5-KLF6 (B) and HepG2-KLF6 (C) cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (D&E) Cell motility was assessed by wound healing assays. KLF6 stable transfectants migrated slower toward the central as compared with the parental cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Identification of miRNAs that specifically target tumor suppressive KLF6

Given that the KLF6-SV1 is the most commonly presented KLF6 spliced variant in sporadic prostate cancer patients and it accounts for cancer metastasis and tumor progression,16,21-25 BLAST analysis was utilized to align the mRNA sequences between KLF6-FL and KLF6-SV1. According to the alignment analysis, KLF6-SV1 lacked 154bp compared with KLF6-FL, which encodes the zinc finger DNA binding domain (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. A screening assay identified potential miRNAs that target KLF6-FL rather than its spliced variant KLF6-SV1. (A) Schematic diagrams of the full-length KLF6-FL (4 679 bp) and spliced variant KLF6-SV1 (4 525 bp). KLF6-SV1 was generated by alternative 5′ splice sites and it lacked 154bp in the terminal of exon 2 when compared with KLF6-FL. (B) Bioinformatics prediction screened out some potential miRNAs that specifically targeted the 154bp region. (C) HEK293 cells were co-transfected with miRNAs listed above and pmirGLO Dual-luciferase carrying the specific 154bp region. Luciferase reporter assays showed that miR-210 and miR-1301 profoundly repressed the luciferase reporter activity. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

It has been well established that miRNAs guide the miRISCs (miRNA-induced silencing complexes) to specific sites preponderantly within the 3′-UTR region of target mRNAs and subsequently induced mRNA destabilization or translational repression.36 Nevertheless, little is known about the mutual interaction between miRNAs and coding region of mRNA. Here we hypothesized one potential mechanism that miRNA may influence alternative mRNA splicing through targeting specific coding region of mRNA. To support this hypothesis, we first scanned the full-length of KLF6 for putative sites complementary to seed region of known miRNAs using the online RegRNA program,37 which is designed to identify potential miRNA binding sites within input RNA sequences. Using RegRNA software, we successfully screened out five miRNAs predicted to specifically target the aforementioned 154bp region, the locus of interest (Fig. 3B). We subsequently synthesized the mature miRNA mimics and performed the luciferase reporter assays. Analysis of luciferase reporter assays revealed a profound repression in luciferase activity after ectopic introduction of miR-1301 and miR-210 (Fig. 3C).

MiR-1301 and miR-210 specifically target the tumor suppressive KLF6-FL isoform but not the oncogenic KLF6-SV1 isoform

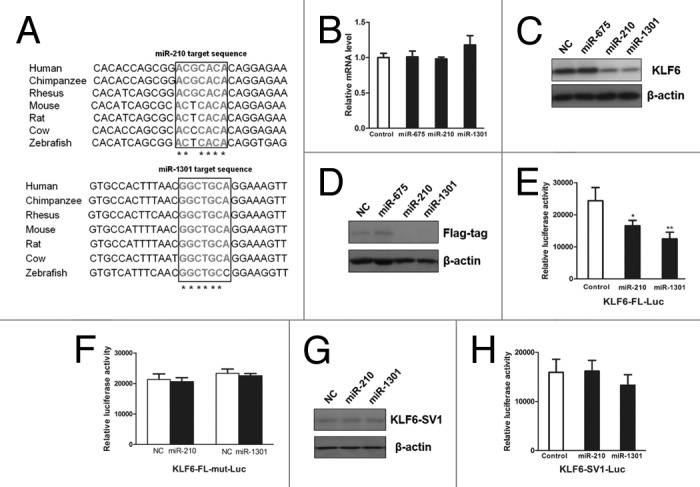

To further testify aforementioned findings, we employed computational algorithms to align the target sites for miR-1301 and miR-210. Comparing the target sequence of human with that of interspecies homology such as chimpanzee, mouse and zebrafish, we found that the miR-1301 and miR-210 target sequences were highly conserved among seven species (Fig. 4A). Next, we conducted RT-PCR to explore the impact of miRNA in regulating mRNA expression. And we used miR-675 as another negative control, which was predicted not to target the protein-coding region of KLF6 by online RegRNA program.37 Unexpectedly, neither miR-1301 nor miR-210 altered the mRNA level of KLF6 (Fig. 4B). Given the possibility that miRNAs may induce translational inhibition in previous study,36 the effect of miR-1301 and miR-210 on endogenous expression of KLF6 was subsequently examined. Consistent with the above-mentioned luciferase reporter assays (Fig. 3C), both miR-1301 and miR-210 induced an obvious reduction of KLF6 protein in HepG2 cells (Fig. 4C). To reinforce this conclusion, we co-transfected miR-1301 and miR-210 with the pCMV-Tag2 vector expressing a FLAG-tagged KLF6 protein. After overexpression of miR-1301 and miR-210, notable repression on KLF6 protein level was observed in the immunoblotting results (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. MiR-210 and miR-1301 regulated KLF6-FL protein expression through interaction with its protein coding region. (A) Schematic diagrams of miRNA binding sites on KLF6-FL. Two miR-210 and miR-1301 binding sites in the protein-coding region of KLF6-FL were highly conserved across different species. Upper panel showed sequence alignment of the miR-210 binding sites across seven different species. Lower panel presented sequence alignment of the miR-1301 binding sites across seven different species. (B) RT-PCR analysis showed the relative expression of KLF6-FL after ectopic expression of miR-675, miR-210 or miR-1301. No significant change in mRNA level was observed after transfection with these miRNAs. (C) Immunoblotting of KLF6 in HepG2 cells transfected with miRNA mimics or negative control. MiR-210 and miR-1301 significantly suppressed KLF6-FL expression in protein level. (D) HEK293 cells were co-transfected with miRNA mimics together with Flag-KLF6-FL. Cell extracts were subjected to immunoblotting analysis to detect Flag tag. Western blot showed that both miR-210 and miR-1301 significantly attenuated the protein expression of KLF6-FL with Flag tag. (E) HEK293 cells were co-transfected with miRNA mimics combined with plasmid harboring the coding region of KLF6-FL. Luciferase reporter assays presented the repression of miR-210 and miR-1301 on the activity of luciferase reporter harboring KLF6-FL in HEK-293 cells. The Firefly luciferase activities were normalized to β-Galactosidase activity. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (F) Site-directed mutagenesis of the binding sites for miR-210 and miR-1301 abolished the suppressive effect. (G) Immunoblotting of KLF6 in HepG2 cells transfected with miRNA mimics or negative control. Ectopic expression of miR-210 and miR-1301 did not affect KLF6-SV1 protein expression. (H) HEK293 cells were co-transfected with miRNA mimics combined with plasmid harboring coding region of KLF6-SV1. No significant change on luciferase activity was presented after ectopic expression of miR-210 and miR-1301.

Following the immunoblotting analysis, we next constructed a luciferase reporter plasmid harboring the coding region of KLF6-FL. In parallel, we generated a second reporter construct by deleting the aforementioned 154bp region, the final sequence of which is equal to the coding region of KLF-SV1. As expected, significant repression on the luciferase activity was observed in the construct with coding region of KLF6-FL (Fig. 4E) while the site-directed mutagenesis for the binding sites within luciferase reporter abolished aforementioned suppressive effects (Fig. 4F). To further verify the specificity of miR-210 and miR-1301 in the regulation of KLF6-FL, we next evaluated the effect of miR-210 and miR-1301 on KLF6-SV1. As expected, overexpression of miR-210 and miR-1301 did not affect the KLF6-SV1 protein expression (Fig. 4G) as well as the luciferase activity of the luciferase reporter harboring the coding region of KLF6-SV1 (Fig. 4H). Collectively, these findings confirmed that both miR-1301 and miR-210 specifically target the tumor suppressive KLF6-FL but not the oncogenic KLF6-SV1 isoform.

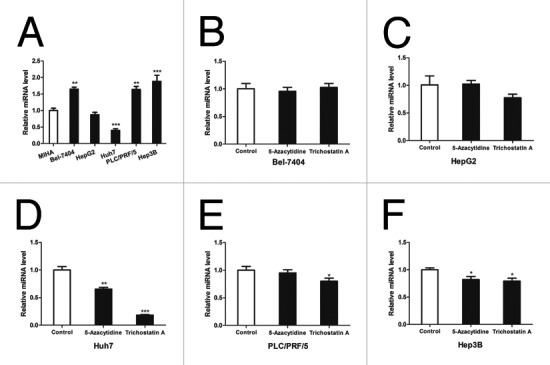

Elevated expression of miR-1301 in HCC cell lines

In the view of the fact that miR-210 has been intensively investigated in preceding reports38 and the biological importance of miR-1301 remains elusive, we next selected miR-1301 for further studies. Five hepatoma cell lines were chosen to evaluate the expression level of miR-1301 using quantitative RT-PCR as compared with the normal immortalized hepatocytes MIHA cells. Marked increase of miR-1301 was found in part of hepatoma cell lines namely Bel-7404, PLC/PRF/5 and Hep3B (Fig. 5A). To test whether the evaluated expression of miR-1301 in HCC cell lines is correlated with DNA methylation or histone deacetylation, these HCC cells were treated with 5-Azacytidine and Trichostatin A, two well-characterized pharmacologic inhibitors for DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) and histone deacetylase (HDAC), respectively. We found that treatment with Trichostatin A remarkably repressed miR-1301 expression in Huh7, PLC/PRF/5 and Hep3B cells while 5-Azacytidine treatment just induced a slight reduction of miR-1301 expression in Huh7 cells and Hep3B cells (Fig. 5B-F). These findings indicate that DNA methylation and histone deacetylation may marginally mediate the dysregulation of miR-1301 in HCC cell lines. Furthermore, it’s known that these two inhibitors can re-activate the expression of tumor suppressor genes by reversing existing suppressive chromatin modification. As miR-1301 is a putative oncogene in this study, it is likely that 5-Azacytidine and Trichostatin A restore the expression of one or more than one tumor suppressor genes, which eventually leads to the inhibition on miR-1301 expression.

Figure 5. Upregulation of miR-1301 was observed in human hepatoma cell lines. (A) Quantitative RT–PCR analysis of mature miR-1301 in serial human hepatoma cell lines. Elevated miR-1301 expression was observed in part of human hepatoma cell lines. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (B to F) Representative RT–PCR results showed relative miR-1301 expression levels in several liver cancer cell lines after treatments with DNMTs inhibitor 5-Azacytidine and HDACs inhibitor Trichostatin A. 5-Azacytidine and Trichostatin A decreased the miR-1301 expression in part of liver cancer cells. MiR-1301 expression level was normalized to housekeeping gene U6 and calculated using 2−ΔΔCt. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Overexpression of miR-1301 promotes angiogenesis cell migration

Given that the function of miR-1301 in tumorigenesis remains largely unknown, we next investigated whether miR-1301 could contribute to angiogenesis and cell migration in liver cancer cells. As revealed in tube formation assays, transient silencing of KLF6 profoundly potentiated angiogenesis in HUVEC cells (Fig. 6A). Similar effect could be achieved by ectopic introduction of miR-1301 into HUVEC cells (Fig. 6B), indicating that miR-1301 may potentiate angiogenesis partially by targeting KLF6-FL. Further experiments demonstrated that ectopic expression of miR-1301 significantly promoted tube formation in HUVEC cells. Furthermore, the wound-healing assays demonstrated that reduction of KLF6 by siRNA or miR-1301 exhibited enhanced migration toward the wound as compared with that of control groups (Fig. 6C and 6D).

Figure 6. Re-expression of miR-1301 or silence of KLF6 promoted tube formation and cell migration. (A&B) Equal numbers of miR-1301 or siKLF6-transfected HUVEC cells were seeded into 96 well plates and the tube formation capacity is quantified by measuring the length of the capillary-like structures. Enhanced tube formation capacity was observed in HUVEC cells with overexpression of miR-1301 (A) or silence of KLF6 (B). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (C&D) Cell migration was assessed by wound healing assays. Overexpression of miR-1301 or silence of KLF6 promoted liver cancer cell motility. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

MiR-1301 was frequently upregulated in HCC specimens

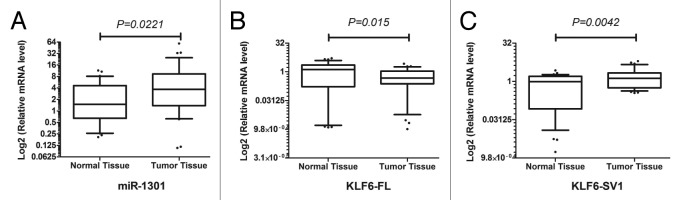

In terms of the biological implication of miR-1301 in tumorigenesis in HCC, we next examined the mRNA expression of miR-1301 in 35 primary liver cancer tissues and their corresponding adjacent normal tissues. MiR-1301 expression was significantly upregulated in tumor tissues as compared with adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 7A; P = 0.0221), suggesting its potential oncogenic characteristics in HCC. On the other hand, we also monitored the expression levels of KLF6-FL and KLF6-SV1 in paired HCC and adjacent non-tumor liver tissues. KLF6-FL displayed significant downregulation in cancerous tissues (Fig. 7B; P = 0.015) while opposing results for KLF6-SV1 were observed in cancerous tissues (Fig. 7C; P = 0.0042), indicating putative antagonistic biological functions for these two isoforms.

Figure 7. Expression analysis of miR-1301 and KLF6 isoforms in paired HCC and adjacent normal tissues by RT-PCR. (A) Elevated expression of miR-1301 was observed in 35 paired HCC specimens. (B&C) Downregulation of KLF6-FL (B) and upregulation of KLF6-SV1 (C) were displayed in in HCC specimens.

Discussion

Despite that overwhelming evidence has highlighted the clinical significance and prognostic implication of aberrant expression of KLF6 spliced variants in multiple cancer types, the molecular mechanisms underlying alternative splicing in HCC remains elusive. In the present study, we propose a novel role played by miRNAs in coordinating the expression of KLF6 spliced variants in hepatoma cells. And we first provide evidence that the tumor suppressive KLF6-FL rather than oncogenic KLF6-SV1 isoform is a bona fide target for miR-210 and miR-1301 in HCC. Following by the observation that elevated expression of miR-1301 is observed in HCC cells and specimens, we demonstrate that overexpression of miR-1301 is correlated with increased cell motility and angiogenesis. Hence, we conclude that one of the molecular mechanisms by which miR-1301 potentiates cell migration and angiogenesis is through the negative regulation of the tumor suppressor KLF6-FL.

A biological function for miR-1301 in tumorigenesis has recently been proposed but the underlying mechanism remains largely unknown. Very recently, a small number of reports have shown varied expression in different cancer types and clinical specimens. Overexpression of miR-1301 was observed in squamous cell carcinomas and colorectal cancer with liver metastasis.39,40 In agreement with this finding, our results revealed elevated miR-1301 expression in HCC cell lines as compared with that of MIHA cells, a normal immortalized liver cell line. However, conversely, another finding showed that miR-1301 expression was reduced in the HepG2 cells when compared with that of QSG-7701 cells, an immortalized normal hepatocyte line.41 One potential explanation for these contradictory results may be due to the fact that different normal liver cells were used for the comparison. Another putative reason for this discrepancy is that the expression of miR-1301 may be merely a passenger during hepatocarcinogenesis due to incidental activation or repression by other unknown transcription factors and hence varied expression status was observed in divergent systems. However, from our study on clinical HCC specimens, elevated miR-1301 expression was observed in liver cancer tissues, indicating a potential oncogenic characteristics for miR-1301 in HCC.

Altered expression profiles of KLF6 and its splice variants KLF6-SV1 have been observed in multiple cancer types.1 Remarkable overexpression of KLF6-SV1, a dominant-negative spliced isoform with antagonistic function against KLF6-FL, has been identified in liver cancer,16,21 lung cancer,22 prostate cancer,20,23,42-44 breast cancer24,45-47 with reduced survival and unfavorable outcome. Conversely, siRNA-mediated inhibition of KLF6-SV1 attenuated the cancer cell proliferation both in vivo and in vitro.35,48 In spite of the fact that inspiring results have been achieved and attempts have been made to elucidate the underlying mechanism about the function of other KLF6 spliced variants,49-51 the expression profiling and the biological implication of the other variants in HCC samples remains obscure.

With the recognition that alteration of miRNA plays a vital role in cancer progression, the mechanisms exploited by miRNA to either potentiate or attenuate cellular transformation are being progressively elucidated.52-54 Furthermore, our knowledge about how miRNA involved in cancer development and progression is expanding. In the past decade, serial evidence revealed that miRNA mediated mRNA degradation or translational repression via targeting not only the 3′UTR region but also the protein-coding region.55-57 In spite of the emerging biological importance of miRNA, however, little is known about the function of miRNA-mediated alternative splicing.58

Taken together, we developed a novel approach to unveil the role of miRNA in KLF6 alternative splicing. With the help of bioinformatics analysis combined with luciferase reporter assays, we successfully identified two miRNAs, miR-1301 and miR-210, targeted tumor suppressive KLF6-FL but not oncogenic KLF6-SV1 isoform. We also further demonstrated the elevated miR-1301 expression in HCC cell lines as well as HCC specimens, suggesting its previously unidentified role as a potential regulator of liver cancer. Though several studies highlighted the importance of miRNA in coordinating the balance of gene networks and the discordance of miRNA expression may disrupt cellular homeostasis, nevertheless, further investigations are deemed necessary to delineate the unknown missing links between miRNA and alternative splicing.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture condition

MIHA, Bel-7404, HepG2, Huh7, PLC/PRF/5, Hep3B and HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with fetal bovine serum plus penicillin and streptomycin. HUVEC cells were grown in Medium 199 containing fetal bovine serum, bFGF, heparin and penicillin as well as streptomycin.

RNA interference and cell transfection

The miRNA mimics and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were synthesized by Genepharma (Shanghai, China). Oligonucleotide and plasmid transfection were conducted using the Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Target sequences for siRNAs were shown in Table 1. The cells were harvested and subjected to further investigations after transfection.

Table 1. Details for qRT-PCR primer. Below are the sequences of all qRT-PCR primers used in this study.

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| KLF6-FL-F | CGGACGCACACAGGAGAAAA |

| KLF6-FL-R | CGGTGTGCTTTCGGAAGTG |

| CDK2-F | ATGGAGAACTTCCAAAAGGTGGA |

| CDK2-R | CAGGCGGATTTTCTTAAGCG |

| CDK4-F | TTGCATCGTTCACCGAGATC |

| CDK4-R | CTGGTAGCTGTAGATTCTGGCCA |

| CDK6-F | TGCACAGTGTCACGAACAGA |

| CDK6-R | ACCTCGGAGAAGCTGAAACA |

| CDKN2A-F | ATGGAGCCTTCGGCTGACT |

| CDKN2A-R | GTAACTATTCGGTGCGTTGGG |

| CDC25A-F | ACAGCTCCTCTCGTCATGAGAAC |

| CDC25A-R | GGTCTCTTCAACACTGACCGAGT |

| Cyclin E1-F | CAGATTGCAGAGCTGTTGGA |

| Cyclin E1-R | TCCCCGTCTCCCTTATAACC |

| VEGFR2-F | TGATGTGGTTCTGAGTCCGT |

| VEGFR2-R | AGACTGGGTTTTTAGGTCTCGG |

| Tie1-F | TGGCTGCTCTTGTGGATCTG |

| Tie1-R | TCTCACAGTGCACTCCATGC |

| Tie2-F | TTCACCAGGCTGATAGTCCG |

| Tie2-R | ACACGTCCTTCCCATAAACCC |

| Ang2-F | CTGGGAAGGGAATGAGGCTT |

| Ang2-R | CATGCATCAAACCACCAGCC |

| VEGF-F | CTACCTCCACCATGCCAAGT |

| VEGF-R | GCAGTAGCTGCGCTGATAGA |

| p21-F | TGTCCGTCAGAACCCATGC |

| p21-R | AAAGTCGAAGTTCCATCGCTC |

| RPLPO-F | CCGGATATGAGGCAGCAGTT |

| RPLPO-R | GAAGGCTGTGGTGCTGATGG |

| U6 | CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA |

| miR-1301 | TTGCAGCTGCCTGGGAGTGACTTC |

| miR-210 | CTGTGCGTGTGACAGCGGCTGA |

| Primers for plasmid constructs | |

| KLF6-CDS-luc-F | AGCTTTGTTTAAACATGGACGTGCTCCCCATGTG |

| KLF6-CDS-luc-R | GCTCTAGATCAGAGGTGCCTCTTCATGT |

| KLF6–184bp-luc-F | ACACGAGCTCTGCGCAGCGGGACTTCGG |

| KLF6–184bp-luc-R | GCTCTAGACCTTCCCATGAGCATCTGTA |

| KLF6-Deletion-R1 | TAAGGCTTTTCTCCTTCCCTGGCGAGG |

| KLF6-Deletion-F2 | CGCCAGGGAAGGAGAAAAGCCTTACAG |

| siRNA sequence | |

| siKLF6-sense | GCAGGAAAGUUUACACCAAtt |

| siKLF6-antisense | UUGGUGUAAACUUUCCUGCtt |

Part of the above primer sequences were obtained from the PrimerBank and the reference for which is: Spandidos, A., Wang, X., Wang, H. and Seed, B. PrimerBank: a resource of human and mouse PCR primer pairs for gene expression detection and quantification. Nucleic Acids Res 38, D792–799 (2010)

Retroviral transduction

Virus particles were harvested 48 h after pBABE-puro-KLF6 co-transfection with the pCL-Ampho packaging vector (a kind gift from Yiu Loon Chui, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong) into HEK293 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). The HepG2 and PLC/PRF/5 cells were then infected with recombinant retrovirus particles plus Polybrene (Sigma, USA). Two days post-infection with pBabe-KLF6 or pBabe retroviruses, puromycin (Sigma, USA) was added to HepG2 and PLC/PRF/5 cells for antibiotics selection. Polyclonal pools of retrovirus-infected cell lines were collected, and KLF6 expression was examined by quantitative Real-time PCR and western blot analysis.

XTT assays and colony formation assays

Cell growth was determined using the XTT colorimetric assays (Promega, USA) following the manufacturer's protocols. Liver cancer cells from two KLF6 stable transfectants were seeded into 96 well plates and incubated with colorimetric reagents XTT. Cell proliferation at different time points was monitored by measurement at the wavelength of 490 nm using the ELISA plate reader (Bio-Rad, USA). For colony formation assays, low cell density of HepG2 and PLC/PRF/5 cells stably transfected with KLF6 or control vector were seeded into 6 well plates. Colonies were allowed to generate for 10 d and subjected to crystal violet staining. The images were taken and colonies were counted by the Image J software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Flow cytometry

Stable KLF6 polyclonal pools and parental cells were cultured to 70% confluence and subsequently harvested for fixation as well as Propidium iodide (PI) staining. After PI staining, the cells were subjected to cell cycle progression analysis using LSR Fortessa and FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences, USA).

Soft agar assays

Cells were cultured in 0.35% upper agar layer on 6 well plates pre-coated with 0.5% basal agar layer. After 10-d culture, cells were stained with crystal violet. Photos of stained colonies were taken and counted with software Image J (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Wound healing assays

HepG2 and PLC/PRF/5 cells stably transfected with KLF6 or control vector were grown to 100% confluence and the monolayer cells were subsequently wounded across the well with pipette tips. The open area of cell-free region was recorded and calculated using the software Image J (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Tube formation assays

HUVEC cells were seeded into a 96-well plate pre-coated with matrigel. After incubation, the cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet. Images were taken and the length of formed tubes in HUVEC cells was quantified by Image J software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

DNA methylation and histone deacetylation inhibitors treatment

For epigenetic modification status in HCC cells, cultured hepatoma cells were treated with DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-Azacytidine and histone deacetylase inhibitor Trichostatin A. The cells were collected and then subjected to further experiments.

Western blot

Protein samples were extracted with RIPA lysis buffer. Cellular protein was separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to the PVDF membrane. For western blot analysis on KLF6, nuclear extracts were prepared and subjected to immunoblotting. The following antibodies were used to incubate with the membrane: KLF6 (Santa Cruz, USA), KLF6 SV1(clone 9A2, Life Technologies), Flag (Stratagene, USA), PARP (Cell Signaling Technology, USA), Caspase 3 (Cell Signaling Technology, USA), GAPDH (Santa Cruz, USA) and β-actin (Sigma, USA). The band intensity of immunoblots was detected on Super RX X-ray film (Fujifilm, Japan).

RNA extraction and quantitative Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and reversely transcribed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) or One Step Primer Script miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Japan). The quantitative RT–PCR was conducted by using the Fast start Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche) in Viia 7 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. Primers for transfection and PCR are shown in Table 1. The Ribosomal Phosphoprotein Large PO (RPLPO) and spliceosomal RNA U6 were used as internal controls for mRNA and miRNA quantification, respectively.

Plasmid constructions

The constructions of human KLF6-FL in pBABE-puro vector (a kind gift of Prof. Scott L. Friedman, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, USA) and Flag-tagged human KLF6-FL in the pCMV-Tag2 vector (a kind gift from Dr. Bin Guo, North Dakota State University, USA) have been previously described.11,21 The 154bp fragment with 3′ flanking region as well as the coding regions of KLF6-FL subcloned from pBABE-puro-KLF6 and the spliced variant KLF6-SV1 generated from overlapping PCR were inserted into the pmirGLO Dual-luciferase miRNA Target Expression Vector (Promega, USA). Primer sequences for plasmid construction are listed in Table 1.

Luciferase assays

HEK293 cells were cultured in 24 well plates and co-transfected with luciferase reporter plasmid and miRNA mimics as well as pRSV-β-Galactosidase vector as internal control as previous reported.59 The luciferase activity was measured with luciferase reporter gene assays kit (Roche, USA) using the Gloxmax 20/20 Luminometer (Promega, USA). The β-Galactosidase activity was measured with an o-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (ONPG) colorimetric assays at the wavelength of 415 nm by using the ELISA plate reader (Bio-Rad, USA).

HCC clinical Specimens

As described in previous report,60 35 paired primary HCC specimens and corresponding adjacent non-tumor liver tissues were collected after surgical resection in the Prince of Wales Hospital from the Chinese University of Hong Kong (Hong Kong, China). And this study was performed under the guideline from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee at The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Statistical data analysis

All results were presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis of data were performed using Student's independent t test and differences were considered to be statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Scott L. Friedman, Prof. Yiu Loon Chui and Prof. Bin Guo for kindly providing pBabe-KLF6 vector, pCMV-KLF6 vector as well as pCL-Ampho packaging vector, respectively. We thank Prof. Weng Onn Lui (Karolinska Institutet, Sweden) for the helpful comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81201699; 81372450) and the Croucher Foundation.

References

- 1.DiFeo A, Martignetti JA, Narla G. The role of KLF6 and its splice variants in cancer therapy. Drug Resist Updat. 2009;12:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McConnell BB, Yang VW. Mammalian Krüppel-like factors in health and diseases. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1337–81. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00058.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bureau C, Hanoun N, Torrisani J, Vinel JP, Buscail L, Cordelier P. Expression and Function of Kruppel Like-Factors (KLF) in Carcinogenesis. Curr Genomics. 2009;10:353–60. doi: 10.2174/138920209788921010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benzeno S, Narla G, Allina J, Cheng GZ, Reeves HL, Banck MS, Odin JA, Diehl JA, Germain D, Friedman SL. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibition by the KLF6 tumor suppressor protein through interaction with cyclin D1. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3885–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimmelman AC, Qiao RF, Narla G, Banno A, Lau N, Bos PD, Nuñez Rodriguez N, Liang BC, Guha A, Martignetti JA, et al. Suppression of glioblastoma tumorigenicity by the Kruppel-like transcription factor KLF6. Oncogene. 2004;23:5077–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narla G, Kremer-Tal S, Matsumoto N, Zhao X, Yao S, Kelley K, Tarocchi M, Friedman SL. In vivo regulation of p21 by the Kruppel-like factor 6 tumor-suppressor gene in mouse liver and human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2007;26:4428–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarocchi M, Hannivoort R, Hoshida Y, Lee UE, Vetter D, Narla G, Villanueva A, Oren M, Llovet JM, Friedman SL. Carcinogen-induced hepatic tumors in KLF6+/- mice recapitulate aggressive human hepatocellular carcinoma associated with p53 pathway deregulation. Hepatology. 2011;54:522–31. doi: 10.1002/hep.24413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Botella LM, Sánchez-Elsner T, Sanz-Rodriguez F, Kojima S, Shimada J, Guerrero-Esteo M, Cooreman MP, Ratziu V, Langa C, Vary CP, et al. Transcriptional activation of endoglin and transforming growth factor-beta signaling components by cooperative interaction between Sp1 and KLF6: their potential role in the response to vascular injury. Blood. 2002;100:4001–10. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.12.4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrido-Martín EM, Blanco FJ, Roquè M, Novensà L, Tarocchi M, Lang UE, Suzuki T, Friedman SL, Botella LM, Bernabéu C. Vascular injury triggers Krüppel-like factor 6 mobilization and cooperation with specificity protein 1 to promote endothelial activation through upregulation of the activin receptor-like kinase 1 gene. Circ Res. 2013;112:113–27. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.275586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li D, Yea S, Li S, Chen Z, Narla G, Banck M, Laborda J, Tan S, Friedman JM, Friedman SL, et al. Krüppel-like factor-6 promotes preadipocyte differentiation through histone deacetylase 3-dependent repression of DLK1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26941–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang X, Li X, Guo B. KLF6 induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells through up-regulation of ATF3. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29795–801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802515200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito G, Uchiyama M, Kondo M, Mori S, Usami N, Maeda O, Kawabe T, Hasegawa Y, Shimokata K, Sekido Y. Krüppel-like factor 6 is frequently down-regulated and induces apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3838–43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeves HL, Narla G, Ogunbiyi O, Haq AI, Katz A, Benzeno S, Hod E, Harpaz N, Goldberg S, Tal-Kremer S, et al. Kruppel-like factor 6 (KLF6) is a tumor-suppressor gene frequently inactivated in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1090–103. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeng YM, Hsu HC. KLF6, a putative tumor suppressor gene, is mutated in astrocytic gliomas. Int J Cancer. 2003;105:625–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kremer-Tal S, Reeves HL, Narla G, Thung SN, Schwartz M, Difeo A, Katz A, Bruix J, Bioulac-Sage P, Martignetti JA, et al. Frequent inactivation of the tumor suppressor Kruppel-like factor 6 (KLF6) in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2004;40:1047–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.20460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kremer-Tal S, Narla G, Chen Y, Hod E, DiFeo A, Yea S, Lee JS, Schwartz M, Thung SN, Fiel IM, et al. Downregulation of KLF6 is an early event in hepatocarcinogenesis, and stimulates proliferation while reducing differentiation. J Hepatol. 2007;46:645–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camacho-Vanegas O, Narla G, Teixeira MS, DiFeo A, Misra A, Singh G, Chan AM, Friedman SL, Feuerstein BG, Martignetti JA. Functional inactivation of the KLF6 tumor suppressor gene by loss of heterozygosity and increased alternative splicing in glioblastoma. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1390–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamashita K, Upadhyay S, Osada M, Hoque MO, Xiao Y, Mori M, Sato F, Meltzer SJ, Sidransky D. Pharmacologic unmasking of epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor genes in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:485–95. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirasawa Y, Arai M, Imazeki F, Tada M, Mikata R, Fukai K, Miyazaki M, Ochiai T, Saisho H, Yokosuka O. Methylation status of genes upregulated by demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2006;71:77–85. doi: 10.1159/000100475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narla G, Difeo A, Reeves HL, Schaid DJ, Hirshfeld J, Hod E, Katz A, Isaacs WB, Hebbring S, Komiya A, et al. A germline DNA polymorphism enhances alternative splicing of the KLF6 tumor suppressor gene and is associated with increased prostate cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1213–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yea S, Narla G, Zhao X, Garg R, Tal-Kremer S, Hod E, Villanueva A, Loke J, Tarocchi M, Akita K, et al. Ras promotes growth by alternative splicing-mediated inactivation of the KLF6 tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1521–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiFeo A, Feld L, Rodriguez E, Wang C, Beer DG, Martignetti JA, Narla G. A functional role for KLF6-SV1 in lung adenocarcinoma prognosis and chemotherapy response. Cancer Res. 2008;68:965–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narla G, DiFeo A, Fernandez Y, Dhanasekaran S, Huang F, Sangodkar J, Hod E, Leake D, Friedman SL, Hall SJ, et al. KLF6-SV1 overexpression accelerates human and mouse prostate cancer progression and metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2711–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI34780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatami R, Sieuwerts AM, Izadmehr S, Yao Z, Qiao RF, Papa L, Look MP, Smid M, Ohlssen J, Levine AC, et al. KLF6-SV1 drives breast cancer metastasis and is associated with poor survival. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:69ra12. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muñoz Ú, Puche JE, Hannivoort R, Lang UE, Cohen-Naftaly M, Friedman SL. Hepatocyte growth factor enhances alternative splicing of the Kruppel-like factor 6 (KLF6) tumor suppressor to promote growth through SRSF1. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:1216–27. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faustino NA, Cooper TA. Pre-mRNA splicing and human disease. Genes Dev. 2003;17:419–37. doi: 10.1101/gad.1048803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pagani F, Baralle FE. Genomic variants in exons and introns: identifying the splicing spoilers. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:389–96. doi: 10.1038/nrg1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, Blencowe BJ. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1413–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inui M, Martello G, Piccolo S. MicroRNA control of signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:252–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qi W, Liang W, Jiang H, Miuyee Waye M. The function of miRNA in hepatic cancer stem cell. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:358902. doi: 10.1155/2013/358902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang S, He X. The role of microRNAs in liver cancer progression. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:235–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X, Nie Y, Du Y, Cao J, Shen B, Li Y. MicroRNA-181a promotes gastric cancer by negatively regulating tumor suppressor KLF6. Tumour Biol. 2012;33:1589–97. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0414-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai WC, Hsu SD, Hsu CS, Lai TC, Chen SJ, Shen R, Huang Y, Chen HC, Lee CH, Tsai TF, et al. MicroRNA-122 plays a critical role in liver homeostasis and hepatocarcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2884–97. doi: 10.1172/JCI63455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DiFeo A, Narla G, Hirshfeld J, Camacho-Vanegas O, Narla J, Rose SL, Kalir T, Yao S, Levine A, Birrer MJ, et al. Roles of KLF6 and KLF6-SV1 in ovarian cancer progression and intraperitoneal dissemination. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3730–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fabian MR, Sonenberg N, Filipowicz W. Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:351–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang HY, Chien CH, Jen KH, Huang HD. RegRNA: an integrated web server for identifying regulatory RNA motifs and elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W429-34. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang X, Le QT, Giaccia AJ. MiR-210--micromanager of the hypoxia pathway. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:230–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rentoft M, Fahlén J, Coates PJ, Laurell G, Sjöström B, Rydén P, Nylander K. miRNA analysis of formalin-fixed squamous cell carcinomas of the tongue is affected by age of the samples. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:61–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, He X, Liu Y, Ye Y, Zhang H, He P, Zhang Q, Dong L, Liu Y, Dong J. microRNA-320a inhibits tumor invasion by targeting neuropilin 1 and is associated with liver metastasis in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:685–94. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fang L, Yang N, Ma J, Fu Y, Yang GS. microRNA-1301-mediated inhibition of tumorigenesis. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:929–34. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Narla G, Heath KE, Reeves HL, Li D, Giono LE, Kimmelman AC, Glucksman MJ, Narla J, Eng FJ, Chan AM, et al. KLF6, a candidate tumor suppressor gene mutated in prostate cancer. Science. 2001;294:2563–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1066326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calderon MR, Verway M, An BS, DiFeo A, Bismar TA, Ann DK, Martignetti JA, Shalom-Barak T, White JH. Ligand-dependent corepressor (LCoR) recruitment by Kruppel-like factor 6 (KLF6) regulates expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor CDKN1A gene. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:8662–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.311605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gong M, Yu W, Pei F, You J, Cui X, McNutt MA, Li G, Zheng J. KLF6/Sp1 initiates transcription of the tmsg-1 gene in human prostate carcinoma cells: an exon involved mechanism. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:329–39. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu J, Du T, Yuan Y, He Y, Tan Z, Liu Z. KLF6 inhibits estrogen receptor-mediated cell growth in breast cancer via a c-Src-mediated pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;335:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gehrau RC, D’Astolfo DS, Dumur CI, Bocco JL, Koritschoner NP. Nuclear expression of KLF6 tumor suppressor factor is highly associated with overexpression of ERBB2 oncoprotein in ductal breast carcinomas. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozdemir F, Koksal M, Ozmen V, Aydin I, Buyru N. Mutations and Krüppel-like factor 6 (KLF6) expression levels in breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1678-6. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Narla G, DiFeo A, Yao S, Banno A, Hod E, Reeves HL, Qiao RF, Camacho-Vanegas O, Levine A, Kirschenbaum A, et al. Targeted inhibition of the KLF6 splice variant, KLF6 SV1, suppresses prostate cancer cell growth and spread. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5761–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hanoun N, Bureau C, Diab T, Gayet O, Dusetti N, Selves J, Vinel JP, Buscail L, Cordelier P, Torrisani J. The SV2 variant of KLF6 is down-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and displays anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic functions. J Hepatol. 2010;53:880–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu X, Gomez-Pinillos A, Loder C, Carrillo-de Santa Pau E, Qiao R, Unger PD, Kurek R, Oddoux C, Melamed J, Gallagher RE, et al. KLF6 loss of function in human prostate cancer progression is implicated in resistance to androgen deprivation. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:1007–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Urtasun R, Cubero FJ, Nieto N. Oxidative stress modulates KLF6Full and its splice variants. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:1851–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cho WC. OncomiRs: the discovery and progress of microRNAs in cancers. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:60. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruan K, Fang X, Ouyang G. MicroRNAs: novel regulators in the hallmarks of human cancer. Cancer Lett. 2009;285:116–26. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rinn JL, Chang HY. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:145–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duursma AM, Kedde M, Schrier M, le Sage C, Agami R. miR-148 targets human DNMT3b protein coding region. RNA. 2008;14:872–7. doi: 10.1261/rna.972008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tay Y, Zhang J, Thomson AM, Lim B, Rigoutsos I. MicroRNAs to Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 coding regions modulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:1124–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang S, Wu S, Ding J, Lin J, Wei L, Gu J, He X. MicroRNA-181a modulates gene expression of zinc finger family members by directly targeting their coding regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7211–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manni I, Artuso S, Careccia S, Rizzo MG, Baserga R, Piaggio G, Sacchi A. The microRNA miR-92 increases proliferation of myeloid cells and by targeting p63 modulates the abundance of its isoforms. FASEB J. 2009;23:3957–66. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-131847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liang WC, Wang Y, Wan DC, Yeung VS, Waye MM. Characterization of miR-210 in 3T3-L1 adipogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:2699–707. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang JF, He ML, Fu WM, Wang H, Chen LZ, Zhu X, Chen Y, Xie D, Lai P, Chen G, et al. Primate-specific microRNA-637 inhibits tumorigenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma by disrupting signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling. Hepatology. 2011;54:2137–48. doi: 10.1002/hep.24595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.