Abstract

The tongue-hold maneuver is a widely used clinical technique designed to increase posterior pharyngeal wall movement in individuals with dysphagia. It is hypothesized that the tongue-hold maneuver results in increased contraction of the superior pharyngeal constrictor. However, an electromyographic study of the pharynx and tongue during the tongue-hold is still needed to understand whether and how swallow muscle activity and pressure may change with this maneuver. We tested eight healthy young participants using simultaneous intramuscular electromyography with high-resolution manometry during three task conditions including (a) saliva swallow without maneuver, (b) saliva swallow with the tongue tip at the lip, and (c) saliva swallow during the tongue-hold maneuver. We tested the hypothesis that tongue and pharyngeal muscle activity would increase during the experimental tasks, but that pharyngeal pressure would remain relatively unchanged. We found that the pre-swallow magnitude of tongue, pharyngeal constrictor, and cricopharyngeus muscle activity increased. During the swallow, the magnitude and duration of tongue and pharyngeal constrictor muscle activity each increased. However, manometric pressures and durations remained unchanged. These results suggest that increased superior pharyngeal constrictor activity may serve to maintain relatively stable pharyngeal pressures in the absence of posterior tongue movement. Thus, the tongue-hold maneuver may be a relatively simple but robust example of how the medullary swallow center is equipped to dynamically coordinate actions between tongue and pharynx. Our findings emphasize the need for combined modality swallow assessment to include high-resolution manometry and intramuscular electromyography to evaluate the potential benefit of the tongue-hold maneuver for clinical populations.

Keywords: Deglutition, Masako, Maneuver, Pressure, Muscle, EMG, Therapy, Deglutition disorders

Background

The tongue-hold maneuver was developed as a therapeutic swallow maneuver to restrain retraction of the tongue and to isolate movement of the posterior pharyngeal wall. To perform the tongue-hold maneuver, instructions are to “protrude the tongue maximally but comfortably, holding it between the central incisors” and to maintain this position during a saliva swallow [1]. Given the anatomical interconnection between the muscles of the tongue and the upper posterior pharyngeal wall [2–5], the “anterior bulge” observed during the tongue-hold maneuver may result from increased contraction of the superior pharyngeal constrictor and anterior tongue movement may also pull the pharyngeal wall forward. However, whether there is increased contraction of the superior pharyngeal constrictor during the tongue-hold maneuver remains unknown.

Although the muscles of the superior pharyngeal constrictor and the muscles of the tongue each receive a relatively distinct pattern of motor innervation [4], each set of muscles may work in a coordinated fashion to regulate pressure within the pharynx. For example, the muscles of the tongue are innervated by the hypoglossal nerve, and the superior pharyngeal constrictor is innervated by the pharyngeal plexus of the vagus nerve [4]. However, shared interneurons within the medullary swallow area may serve to coordinate the motor neuron pools that innervate the tongue and pharyngeal wall [6, 7]. In addition, the superior pharyngeal constrictor interdigitates with fibers from the glossopharyngeus muscle [5] and may be important to coordinate the interplay between the superior pharyngeal constrictor and tongue movements. It is important to note that sensory feedback from oropharyngeal receptors to the medullary swallow center may be important to regulate intrapharyngeal swallow pressure in response to the altered tongue position [8, 9]. Therefore, the medullary swallow center is equipped to dynamically coordinate actions between muscle groups. These neuromuscular mechanisms may account for the hypothesized increase in superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle activity in the presence of the tongue-hold maneuver. This view is reasonable based on the principle of motor equivalence [10, 11], such that pharyngeal aperture and pharyngeal pressure for swallow may be maintained in the presence of different but complimentary movement patterns. The tongue-hold maneuver provides an interesting paradigm to examine these principles during the swallow.

In clinical studies, reduced or absent ability to retract the tongue due to surgical resection of the oral tongue was associated with compensatory increases in pharyngeal wall movement during the swallow [12]. In addition, increased pharyngeal pressure during the tongue-hold maneuver was observed with 3 ml liquid swallows by participants following surgical and radiotherapy treatment for laryngeal cancer, each of whom had mild dysphagia [13]. As a potential rehabilitation technique, recent evidence in healthy control participants demonstrates that the tongue-hold maneuver is associated with increased submental muscle activity and may serve as a resistance exercise to muscles of the tongue including the genioglossus [14]. However, whether the tongue-hold maneuver yields a potential exercise benefit for the genioglossus muscle and/or the superior pharyngeal constrictor is unknown. Therefore, it would be of benefit to examine these specific muscles and the associated manometric pressures during the maneuver.

Given the role of the tongue and posterior pharynx to generate swallow related pressure, and the potential for the tongue-hold maneuver in swallow rehabilitation, it is of interest to examine how muscle contraction and manometric pressure may change during the tongue-hold maneuver. Although recent evidence suggests reduced pharyngeal swallow pressure during the tongue-hold maneuver [15, 16], the relative contribution of the superior pharyngeal constrictor and genioglossus to pharyngeal pressure remain unknown. The tongue-hold maneuver provides an interesting paradigm to examine whether the pharynx can maintain pressure production when the contribution of the tongue is reduced and the contribution of the superior pharyngeal constrictor is increased. The ability of the pharynx to maintain pressure under different patterns of movement would be an interesting example of motor equivalence for human swallow function [10, 11]. Therefore, we employed intramuscular electromyography with high-resolution manometry mto test whether and how muscle activity and pressure may change with the tongue-hold maneuver. We hypothesized that tongue and pharyngeal muscle activity would increase, and that pharyngeal pressure would remain relatively unchanged.

Methods

Participant

Eight participants (6 male), between 20–27 years old, without history of swallowing, respiratory, or neurological deficits participated in the study. Each participant provided informed consent, and the protocol was approved by the local Institutional Review Board. Participants were instructed to refrain from eating for 4 hours and from drinking for 2 hours before testing to avoid potential effect of satiety.

High-Resolution Manometry and Electromyography

We previously described the instrumentation and procedures [17–19], and will briefly review the methodology below. Pressure was recorded using a solid-state high-resolution manometer (ManoScan360 High-Resolution Manometry System, Sierra Scientific Instruments, Los Angeles, CA). The manometric catheter has an outer diameter of 2.75 mm with 36 circumferential pressure sensors, each spanning 2.5 mm, spaced 1 cm apart. Each sensor receives input from 12 circumferential sectors that are averaged to yield the mean pressure detected by that sensor. The system is calibrated to record pressure between −20 and 600 mmHg, with fidelity of 2 mmHg. The pressure from each sensor was recorded at a sampling rate of 50 Hz (ManoScan Data Acquisition, Sierra Scientific Instruments). The catheter was calibrated before use with each participant according to manufacturer specifications. Topical 2 % viscous lidocaine hydrochloride was applied to the nasal passages and to the manometric catheter as a topical anesthetic and lubricant to ease passage of the catheter through the nasal cavity and pharynx. Based on our previous experiments and the small quantity of viscous lidocaine used (less than 1 cc), the effects on the swallow were negligible [17–19].

Bipolar hook-wire intramuscular electrodes (50-micron diameter, MicroProbes, Gaithersburg, MD) were inserted into the genioglossus, cricopharyngeus, and superior pharyngeal constrictor muscles using a 27-gauge needle. Side of electrode insertion was counterbalanced across participants. Prior to cricopharyngeus (CP) electrode insertion, 1 cc of 1 % lidocaine hydrochloride with epinephrine (1:100,000) was subcutaneously injected into the neck through a 30-gauge needle. The characteristic CP pattern of quiescence during a swallow followed by post-swallow burst of activity was consistent with accurate placement [19, 20]. Bilateral surface electromyography electrodes were placed in the submental region between the mandible and the hyoid bone, each at 1 cm from midline, and a surface ground electrode (A10058-SRT, Vermed, Bellows Falls, VT) was placed on the forehead. Electromyographic signals were amplified, band-pass filtered from 100 Hz to 6KHz (Model 15LT, Grass Technologies, Warwick, RI) and digitized at 20 kHz (LabChart version 6.1.3, ADIn-struments, Colorado Springs, CO) [21, 22].

Tasks

Once the catheter and electrodes were inserted, participants rested for approximately 5 minutes to adjust to the catheter and electrodes prior to performing the experimental tasks. During the experiment, each participant sat comfortably in an exam chair and looked straight ahead with the chin in a neutral position. The tasks included: a) Saliva swallow without maneuver (Fig. 1a); b) Saliva swallow with tongue tip at the lip (Fig. 1b); and c) Saliva swallow with tonguehold maneuver (Fig. 1c). A transparent plastic ruler was used to measure the distance (cm) between the tongue tip and lower lip for the tongue tip at lip task (distance was zero) and for the tongue-hold maneuver task (distance was 1 cm or greater). Figure 2 displays the distance between the tongue tip and lower lip for each of these two experimental tasks. Figure 3 displays submental electromyography for each task. Fifteen trials (five for each of three tasks) were collected and analyzed for each participant. Task order was randomized across participants.

Fig. 1.

Tongue position during swallow. No maneuver (a), tongue tip at lower lip (b), tongue-hold maneuver (c)

Fig. 2.

Tongue tip position from lip. Tongue tip at lip: The tongue tip was zero centimeters from the lower lip. Tongue-hold maneuver: The tongue tip was protruded about 1–2 cm from the lower lip

Fig. 3.

Submental electromyography (EMG). No maneuver (gray), tongue tip at lip (white), and tongue-hold maneuver (black). Note the task-related increase in EMG amplitude at baseline (before solid line), during the swallow (starting at solid line), and after the return to baseline (starting at first dashed line for gray, and at second dashed line for white and black)

Data Analysis

Pressure and electromyography data were analyzed using a customized MATLAB program (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA) [17–19]. Electromyography signals were rectified and normalized so that data could be pooled across participants. The highest peak from the rectified signal for a given muscle and participant was set to equal 1 (see Fig. 3). Therefore, all other data points were computed to be between 0 and 1. Task differences were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) using a criterion significance level of α = 0.05 and the Tukey-Test for pair-wise comparisons. We hypothesized that the amplitude and duration of submental, genioglossus, superior pharyngeal constrictor, and cricopharyngeal muscle activity would increase during the experimental tasks, but that the amplitude and duration of pharyngeal pressure would remain relatively unchanged.

Results

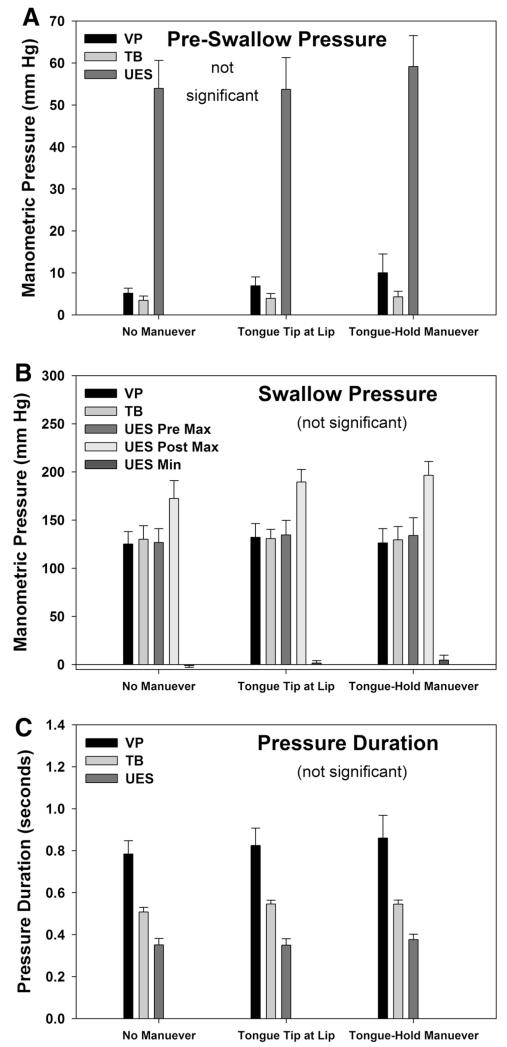

Our findings for electromyographic amplitude and swallow duration are displayed in Fig. 4. Before the swallow, there was a significant main effect of task as the amplitude of submental [F(7,2) = 14, p < 0.001, ], genioglossus [F(7,2) = 8, p = 0.005, , superior pharyngeal constrictor [F(7,2) = 6, p = 0.012, , and cricopharyngeus [F(7,2) = 13, p < 0.001, muscle activity increased. During the swallow, there was a significant main effect of task as the amplitude of submental [F(7,2) = 15, p < 0.001, , genioglossus [F(7,2) = 4, p = 0.038, , and superior pharyngeal pharyngeal constrictor [F(7,2) = 37, p < 0.001, muscle activity, as well as on the duration of submental [F(7,2) = 24, p < 0.001, , genioglossus [F(7,2) = 9, p = 0.003, , and superior pharyngeal pharyngeal constrictor [F(7,2) = 4.5, p = 0.030, muscle activity increased. Amplitude and duration of cricopharyngeus muscle electromyographic activity were unchanged during the swallow (p > 0.05). Our findings for manometric measures of pressure and swallow duration are displayed in Fig. 5. Before the swallow, manometric pressures remained unchanged; during the swallow, pressure magnitude and duration also remained unchanged (p > 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Electromyographic (EMG) Data. Pre-Swallow EMG amplitude (a), Swallow EMG amplitude (b), and Swallow duration (c) for genioglossus (GG), submental (SM), superior pharyngeal constrictor (SPC), and cricopharyngeus (CP) muscles. Bar height represents the mean (standard error). *p < 0.05, ns not significant compared with no maneuver (within the same muscle)

Fig. 5.

Manometric Pressure Data. Pre-Swallow pressure amplitude (a), Swallow pressure amplitude (b), and Swallow duration (c) for pressure sensors located within the pharynx at the level of the velopharynx (VP) and tongue base (TB), or within the upper esophageal sphincter (UES). Swallow related UES pressures (b) are displayed for maximum pressure immediately before the swallow (pre), immediately after the swallow (post), or for the minimum (min) pressure during the swallow. Bar height represents the mean (standard error). No significant changes were observed

Discussion

The tongue-hold maneuver has been recommended as a clinical technique to increase posterior pharyngeal wall movement in individuals with dysphagia [1, 12, 13]. However, an electromyographic study of the pharynx and tongue during the tongue-hold was still needed to understand whether and how swallow muscle activity and pressure may change with this maneuver. Therefore, we employed simultaneous intramuscular electromyography with high-resolution manometry during three task conditions including (a) saliva swallow without maneuver, (b) saliva swallow with the tongue tip at the lip, and (c) saliva swallow during the tongue-hold maneuver. We tested the hypothesis that tongue and pharyngeal muscle activity would increase during the experimental tasks, but that pharyngeal pressure would remain relatively unchanged. Our findings generally supported our hypotheses. For muscle activity, we found that the pre-swallow magnitude of submental, genioglossus, superior pharyngeal constrictor, and cricopharyngeus electromyography signals increased. During the swallow, the magnitude and duration of submental, genioglossus, and superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle activity each increased. However, the magnitude and duration of cricopharyngeus muscle activity were unchanged during the swallow. As hypothesized, the pre-swallow pressures and the swallow pressures and durations remained unchanged. Our results suggest that the tongue-hold maneuver may result in increased tongue and pharyngeal muscle activity, with relatively stable pharyngeal pressures.

We would suggest that the relatively stable pressures across tasks in these healthy participants may result from increased activity of the superior pharyngeal constrictor to maintain similar pharyngeal pressures in the absence of posterior tongue movement. Our data and this view are consistent with previous studies of swallow neurophysiology and clinical studies of the tongue-hold maneuver [1, 12, 13]. It is likely that oropharyngeal sensory receptors respond to the altered tongue position to provide medullary swallow interneurons with feedback needed to coordinate the movement and position of the superior pharyngeal constrictor and tongue [8, 9, 23–26]. These neuromuscular mechanisms may account for the observed increase in superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle activity in the presence of the tongue-hold maneuver. The finding that pharyngeal pressure remained constant during the tongue-hold maneuver is consistent with the principle of motor equivalence. Specific to the tongue-hold maneuver, pharyngeal swallow pressure was maintained in the presence of different movement patterns. Therefore, the tongue-hold maneuver may be a relatively simple but robust example of how the medullary swallow center is equipped to dynamically coordinate actions between muscle groups. Although our study excluded direct visualization of pharyngeal wall movement or pharyngeal aperture, our manometric and electromyographic data confirm that the tongue-hold maneuver provides an interesting paradigm to examine these principles during the swallow.

Although our findings are of interest from clinical and physiologic perspectives, important limitations remain that will be important to address in future work. We acknowledge that this study was limited to a relatively modest sample of healthy young adults. Therefore, the next steps will be to examine the tongue-hold maneuver in larger cohorts of older healthy adults, and in participants with clinical dysphagia. The combined manometric-electromyographic approach will be particularly valuable when integrated with imaging modalities including videofluoroscopy or endoscopy. We also acknowledge that our findings may differ to some degree from earlier manometric studies. However, it is important to note that we employed high-resolution manometry using 36 circumferential sensors, with 12 sensing sectors at each sensory location. Earlier studies utilized fewer manometric sensors with only a single sector at each sensor location [13, 16]. The advent of 3-dimensional high resolution manometry may provide additional information to advance our understanding of the posterior and lateral pharyngeal movements during the tongue-hold maneuver [27]. Previous studies employed hands-on cursor measurements or studied participants who were reclined in a supine position [28]. We utilized validated computerized analysis routines and each study participant was in an upright seated position [17–19]. Given such methodological differences, it is critical for the clinical and scientific community to carefully observe these details when reading the literature and when planning future studies. Finally, we acknowledge that at this time we are unable to determine whether the tongue-hold maneuver would serve well as a resistance exercise for tongue or pharyngeal muscles as we simply examined each participant during a single test session. Our findings suggest that there is a reasonable physiological rationale on which to base future clinical studies. However, such a study must carefully examine what exercise schedule may be of clinical benefit to specific individuals with dysphagia and should include manometric, electromyographic, and imaging modalities. Such a study is needed, but has yet to be reported in the literature.

In conclusion, this study was the first to evaluate the tongue-hold maneuver using simultaneous high-resolution manometry and intramuscular electromyography. We found that tongue and pharyngeal muscle activity increased during with the tongue-hold maneuver, but that pharyngeal pressure remained relatively unchanged. Our findings are generally consistent with previous studies, and suggest that the tongue-hold maneuver may be an example of the medullary swallow center’s ability to dynamically coordinate actions between muscle groups. Our findings emphasize the need for combined modality assessment of swallow physiology to include high-resolution manometry, intramuscular electromyography, and videofluoroscopic or endoscopic imaging, with important implications for future study of the tongue-hold maneuver in clinical populations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant DC011130, UW Department of Surgery pilot grant, and the UW Shapiro Summer Research Program. Dr. Hammer is also supported through National Institutes of Health Grants DC010900 and RR025012.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fujiu M, Logemann JA. Effect of a tongue-holding maneuver on posterior pharyngeal wall movement during deglutition. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1996;5:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kokawa T, Saigusa H, Aino I, Matsuoka C, Nakamura T, Tanuma K, Yamashita K, Niimi S. Physiological studies of retrusive movements of the human tongue. J Voice. 2006;20:414–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2005.08.004. doi:10.1016/j. jvoice.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saigusa H, Yamashita K, Tanuma K, Saigusa M, Niimi S. Morphological studies for retrusive movement of the human adult tongue. Clin Anat. 2004;17:93–8. doi: 10.1002/ca.10156. doi:10.1002/ca.10156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zemlin WR. Speech and hearing science: anatomy and physiology. 3rd ed. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takemoto H. Morphological analyses of the human tongue musculature for three-dimensional modeling. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2001;44:95–107. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amri M, Car A. Projections from the medullary swallowing center to the hypoglossal motor nucleus: a neuroanatomical and electrophysiological study in sheep. Brain Res. 1988;441:119–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91389-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amri M, Car A, Roman C. Axonal branching of medullary swallowing neurons projecting on the trigeminal and hypoglossal motor nuclei: demonstration by electrophysiological and fluorescent double labeling techniques. Exp Brain Res. 1990;81:384–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00228130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jean A. Brainstem organization of the swallowing network. Brain Behav Evol. 1984;25:109–16. doi: 10.1159/000118856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jean A. Control of the central swallowing program by inputs from the peripheral receptors. a review. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1984;10:225–33. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(84)90017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunner J, Ghosh S, Hoole P, Matthies M, Tiede M, Perkell J. The influence of auditory acuity on acoustic variability and the use of motor equivalence during adaptation to a perturbation. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2011;54:727–39. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0256). doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perkell JS, Matthies ML, Svirsky MA, Jordan MI. Trading relations between tongue-body raising and lip rounding in production of the vowel /u/: a pilot “motor equivalence” study. J Acoust Soc Am. 1993;93:2948–61. doi: 10.1121/1.405814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujiu M, Logemann JA, Pauloski BR. Increased postoperative posterior pharyngeal wall movement in patients with anterior oral cancer: preliminary findings and possible implications for treatment. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1995;4:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazarus C, Logemann JA, Song CW, Rademaker AW, Kahrilas PJ. Effects of voluntary maneuvers on tongue base function for swallowing. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2002;54:171–6. doi: 10.1159/000063192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujiu-Kurachi M, Fujiwara S, Tamine KI, Kondo J, Minagi Y, Maeda Y, Hori K, Ono T. Tongue pressure generation during tongue-hold swallows in young healthy adults measured with different tongue positions. Dysphagia. 2014;29:13–7. doi: 10.1007/s00455-013-9471-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doeltgen SH, Macrae P, Huckabee ML. Pharyngeal pressure generation during tongue-hold swallows across age groups. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2011;20:124–30. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0067). doi:10.1044/1058-0360 (2011/10-0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doeltgen SH, Witte U, Gumbley F, Huckabee ML. Evaluation of manometric measures during tongue-hold swallows. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2009;18:65–73. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2008/06-0061). doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2008/06-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman MR, Mielens JD, Ciucci MR, Jones CA, Jiang JJ, McCulloch TM. High-resolution manometry of pharyngeal swallow pressure events associated with effortful swallow and the Mendelsohn maneuver. Dysphagia. 2012;27:418–26. doi: 10.1007/s00455-011-9385-6. doi:10. 1007/s00455-011-9385-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mielens JD, Hoffman MR, Ciucci MR, Jiang JJ, McCulloch TM. Automated analysis of pharyngeal pressure data obtained with high-resolution manometry. Dysphagia. 2011;26:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s00455-010-9320-2. doi:10. 1007/s00455-010-9320-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones CA, Hammer MJ, Hoffman MR, McCulloch TM. Quantifying contributions of the cricopharyngeus to upper esophageal sphincter pressure changes by means of intramuscular electromyography and high-resolution manometry. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2014;123:174–82. doi: 10.1177/0003489414522975. doi:10.1177/0003489414522975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doty RW, Bosma JF. An electromyographic analysis of reflex deglutition. J Neurophysiol. 1956;19:44–60. doi: 10.1152/jn.1956.19.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ertekin C, Pehlivan M, Aydogdu I, Ertas M, Uludag B, Celebi G, Colakoglu Z, Sagduyu A, Yuceyar N. An electrophysiological investigation of deglutition in man. Muscle Nerve. 1995;18:1177–86. doi: 10.1002/mus.880181014. doi:10.1002/mus.880181014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ertekin C, Aydogdu I. Electromyography of human cricopharyngeal muscle of the upper esophageal sphincter. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26:729–39. doi: 10.1002/mus.10267. doi:10.1002/mus.10267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jean A. Brain stem control of swallowing: neuronal network and cellular mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:929–69. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amri M, Car A, Jean A. Medullary control of the pontine swallowing neurones in sheep. Exp Brain Res. 1984;55:105–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00240503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jean A, Car A. Inputs to the swallowing medullary neurons from the peripheral afferent fibers and the swallowing cortical area. Brain Res. 1979;178:567–72. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90715-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Car A, Jean A, Roman C. A pontine primary relay for ascending projections of the superior laryngeal nerve. Exp Brain Res. 1975;22:197–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00237689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geng Z, Hoffman MR, Jones CA, McCulloch TM, Jiang JJ. Three-dimensional analysis of pharyngeal high-resolution manometry data. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1746–53. doi: 10.1002/lary.23987. doi:10.1002/lary.23987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umeki H, Takasaki K, Enatsu K, Tanaka F, Kumagami H, Takahashi H. Effects of a tongue-holding maneuver during swallowing evaluated by high-resolution manometry. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:119–22. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.01.025. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]