Abstract

Objective

This study was designed to propose a classification scheme for platforms of surgical delivery in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and to review the literature documenting their effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, sustainability, and role in training. Approximately 28 % of the global burden of disease is surgical. In LMICs, much of this burden is borne by a rapidly growing international charitable sector, in fragmented platforms ranging from short-term trips to specialized hospitals. Systematic reviews of these platforms, across regions and across disease conditions, have not been performed.

Methods

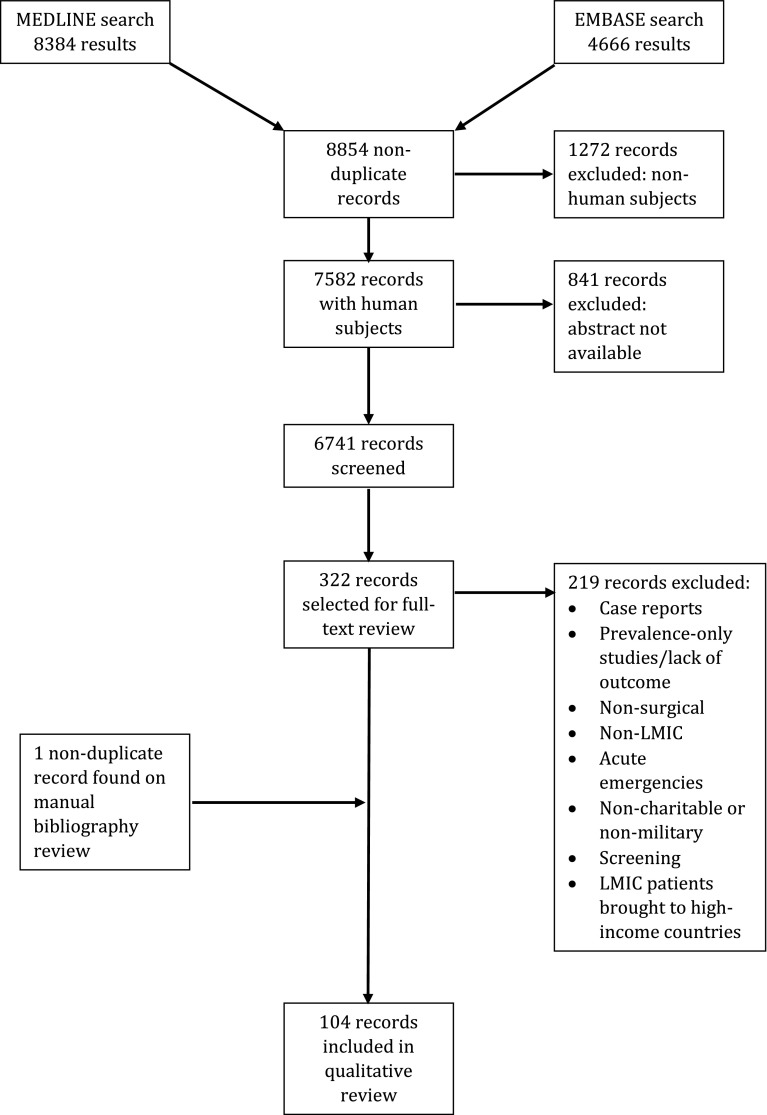

A systematic review of MEDLINE and EMBASE databases was performed from 1960 to 2013. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined a priori. Bibliographies of retrieved studies were searched by hand. Of the 8,854 publications retrieved, 104 were included.

Results

Surgery by international charitable organizations is delivered under two, specialized hospitals and temporary platforms. Among the latter, short-term surgical missions were the most common and appeared beneficial when no other option was available. Compared to other platforms, however, worse results and a lack of cost-effectiveness curtailed their role. Self-contained temporary platforms that did not rely on local infrastructure showed promise, based on very few studies. Specialized hospitals provided effective treatment and appeared sustainable; cost-effectiveness evidence was limited.

Conclusions

Because the charitable sector delivers surgery in vastly divergent ways, systematic review of these platforms has been difficult. This paper provides a framework from which to study these platforms for surgery in LMICs. Given the available evidence, self-contained temporary platforms and specialized surgical centers appear to provide more effective and cost-effective care than short-term surgical mission trips, except when no other delivery platform exists.

Introduction

Approximately 28 % of the global burden of disease is amenable to surgical intervention, a proportion that is higher in the developing world (author calculations, using the 2010 Global Burden of Disease survey [1]. Because of difficulties in access to care [2–5], at least part of this burden is borne by the international charitable sector. Historically, local hospitals in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have treated conditions associated with a low disability-adjusted life year (DALY) burden and have done so with a high loss to follow-up, especially as the complexity and upfront cost of surgeries increase [3]. Meanwhile, the charitable sector is large; in the United States, this sector, which includes many international surgical organizations, has grown at a pace exceeding GDP by 20 % [6]. This review will focus on the role of charitable organizations in surgical delivery in LMICs.

Any attempt to examine nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) must necessarily define these platforms. This is a daunting task—an entire galaxy of NGOs provides surgical care, few of which easily fit into any single categorization. Additionally, although the literature currently focuses on the conditions each organization treats, this focus masks salient similarities and differences among platforms, and, in doing so, may actually promote fragmentation in delivery.

This review, instead, will accomplish two goals: first, propose a classification scheme for charitable surgical delivery, focusing on the method of delivery, as opposed to the diseases treated. Using this new framework, this review will then compare NGO platforms along metrics of effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, sustainability, and their role in training. Focusing on the platform of care, rather than on disease-specific organizations, allows for benefits common to each platform to emerge, distinct from the diseases treated and the organizations that treat them.

We have limited our study only to charitable (or partly charitable) organizations and have evaluated them along only four domains: effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, sustainability, and their role in training. This is not to suggest that these are the only metrics by which these organizations should be evaluated. Ethical considerations are not, for example, explicitly considered, although they are arguably as important as the included domains [7–10].

Finally, other methods of delivering surgery in LMICs are not discussed: telemedicine [11] and cancer screening [12] are not included. Many individual surgeons organize their own trips to LMICs; none have produced peer-reviewed publications. Mobile surgical platforms sent from in-country hospitals [13], and surgical outreaches in humanitarian emergencies (as performed by organizations, such as Médecins Sans Frontières and the Red Cross) operate under different mandates, with currently limited (but positive) data, and are similarly excluded [14, 15]. Finally, teams that aim to establish residency or training programs have yet to publish enough of their outcomes to be evaluated. The few papers that have been published are, however, promising [16, 17].

Methodology

A systematic review of the literature was performed to assess the cost, effectiveness, sustainability, and role in training of various surgical platforms. Guidelines and methods for systematic review have been standardized and reported elsewhere [18]. These guidelines, as they apply to observational studies, were followed in this paper. The MEDLINE search strategy is given in Box 1.

Box 1.

MEDLINE search strategy

| (Surgical Procedures, Operative[MeSH Terms] OR surgery[tiab] OR surgeries[tiab] OR surgical[tiab] OR operative[tiab] OR operating room[tiab] OR operation[tiab] OR cleft lip[tiab] OR cleft palate[tiab] OR eye[tiab] OR congenital[tiab] OR heart[tiab] OR cardiac[tiab] OR vesicovaginal[tiab] OR obstetric fistula[tiab] OR genital fistula[tiab] OR trauma[tiab]) |

| AND |

| (Medical Missions, Official[MeSH Terms] OR Missions and Missionaries[MeSH Terms] OR Mobile Health Units[MeSH Terms] OR Relief Work[MeSH Terms] OR Voluntary Workers[MeSH Terms] OR humanitarian[tiab] OR surgical mission*[tiab] OR missionary[tiab] OR resource limited[tiab] OR low income countr*[tiab] OR middle income countr*[tiab] OR developing countr*[tiab] OR LMIC[tiab]) |

| NOT “case reports”[publication type] |

This search strategy (with appropriate language) also was used for EmBASE

Bibliographies of the retrieved studies were searched for other relevant publications. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were decided on a priori. Only published, peer-reviewed articles were included. The search was not limited to articles in English. Data were extracted using piloted forms and performed by all three authors. Because of a high risk of heterogeneity in studies across multiple disease conditions, countries, and platforms of delivery, no mathematical summary measure was calculated.

Of 8,854 records retrieved, 6,741 were screened by title and abstract; one additional article was found on bibliographic review, and the full text of 322 was screened. From these, 104 articles were selected inclusion. The review process, as well as the previously determined exclusion criteria are listed in the PRISMA diagram found in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram, documenting the search strategy results, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and final records included in this qualitative systematic review

A note on terminology: although some NGOs providing surgery in LMICs are faith-based, not all are. The word mission in this review does not refer only to faith-based organizations; it is used more broadly of all temporary delivery platforms. Similarly, the word humanitarian is limited to missions that operate under the setting of acute emergencies, and the word charitable to organizations that are, at least in part, funded by private donations.

Results

A taxonomy of specialized surgical platforms

The literature suggests that charitable organizations delivery surgery in two basic ways: by establishing specialty surgical hospitals, or by focusing on more temporary platforms:

- Temporary surgical platforms By far the most common, this near-ubiquitous model of surgical delivery can be informatively broken down further:

- Short-term surgical trips This platform sends surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, and/or supporting staff—along with, at times, surgical instrumentation and technology—into LMIC hospitals and clinics for short periods. Often, these NGOs perform a restricted set of surgeries, relying on local physicians for followup. Organizations such as Operation Smile [19–23], numerous orthopedic organizations [24], and many others fit this model.

- Self-contained surgical platforms Significantly rarer, these NGOs often spend longer in-country than the short-term trips (months to years) but, importantly, carry their infrastructure with them. Self-contained on ships, airplanes, and other modes of transportation, these organizations tend not to leave behind any physical structure. Organizations such as Mercy Ships [25, 26] and CinterAndes fit this model.

Specialty surgical hospitals Another common model for surgical delivery by NGOs, these platforms establish an entire physical plant, either de novo or within an existing structure, dedicated to the treatment of one or a few related surgical conditions. Organizations such as the Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital or the Aravind Eye Hospital fit this model.

This classification scheme allows conclusions to be drawn about effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, sustainability, and the role in training of broad platforms of charitable surgical delivery in LMICs, separate from the individual conditions treated.

Temporary surgical platforms

Short-term surgical trips

Short-term, disease-specific surgical missions are myriad [27]: from “eye camps” in India [28–33] to “ear camps” in Namibia [34]; from organizations focused on facial clefting [19–23] to those focused on hernias [35], cardiac surgery [36], and endemic goiter [37]—services rendered, lengths of surgical trips, and resultant efficacies vary.

Underpinning these platforms, however, is a uniting model: surgical teams are flown into regions with high burdens of specific diseases, where they operate for short stints, often on the order of 1 to 2 weeks [38], and often in partnership with in-country physicians, to whom is left all but the most immediate of follow-up care. These missions, also called safaris [39] or blitzes [40], frequently carry their own equipment with them [38, 41], often return to the same region in subsequent years [24, 42–44], and strive toward close partnership with local hospitals and ministries of health [45, 46].

Despite the plethora of organizations that adopt this short-term model, evaluations of its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness are few. In part, this is due to a difficulty with follow-up. Of 4,100 operations for cleft lip and palate by 1 organization in 40 simultaneous sites, for example, only 703 patients (17 %) returned for a 6- to 9-month postoperative visit [19]. Similarly, in a Spanish-African cooperation program for the repair of hernias, follow-up was 21 % [16].

Effectiveness

A survey of 99 international surgical organizations found that the majority provided fewer than 500 operations per year [27]. Strong evidence exists for an association between surgical volume and outcomes in North America [47], with a stronger impact by hospital volume than by surgeon volume, especially for higher-complexity procedures [48, 49]. This seems to be maintained in the short-term platform; these organizations tend to suffer from higher mortality and complication rates while producing mixed results. In an evaluation of more than 17,000 operations performed in sub-Saharan Africa more than 114 surgical missions in two decades, an overall mortality of 3.3 % was achieved [50]. The majority of these operations were for hernias, for which a mortality as high as 1 % was observed—20 times higher than in high-income countries [51].

Both the success of an operative mission and its complication rates, however, vary by surgical procedure. Simpler procedures, such as tonsillectomy, appear safe when performed by short-term surgical missions [52]. Others less so: Maine et al [53]. Reported a rate oronasal fistula after cleft palate repair, which is more than 20-fold higher in surgical missions than in high-income countries. In their study, cases performed by experienced Ecuadorean and North American surgeons on a mission to Ecuador were compared with cases performed by similar surgeons at an American tertiary hospital. All surgeons showed this 20-fold increase in complication rates; no difference was found between Ecuadorean and North American surgeons. Although there are obviously patient-level factors that confound this increased complication rate, this finding lends further credence to an assertion that mission volume has potentially more impact than surgeon experience [53]. De Buys Roessingh et al. [42] similarly report relatively poor functional results in the repair of cleft palates on short-term surgical missions; the inherent difficulty of establishing a multidisciplinary approach in short-term surgical missions may contribute to these outcomes [54].

Results from cataract surgeries performed in eye camps are equally variable: Some report good vision outcomes [31], others poor [55]. Variability also is seen in otologic surgery; in surgical camps in Greenland [56, 57] and in mobile surgical units in Thailand [58], low complication rates and good results were found for chronic ear disease. Other authors, however, report success tied very strongly to either pathologic diagnosis [59] or the age of the surgical mission, with better results occurring a few years after the mission’s establishment [60].

Acceptable results have been found in cardiac surgery [36, 61], although some results come from very small surveys. Similar good results are reported in goiter missions, especially as they are repeated [37]. However, for the repair of burn contractures, Kim et al. found complications rates higher on surgical missions than in high-income countries [62], and, in orthopedics, Cousins et al. report success rates ranging from 28 to 75 %. Among the largest group of patients—those with lower limb trauma—47 % experienced complications [24]. Young et al. [63, 64] similarly document a not insignificant, postoperative infection rate after intramedullary nailing.

Overall, a pattern emerges in a review of the effectiveness of the short-term platform; for the condition most commonly treated by the charitable sector, the more complex the surgery, the more unsatisfactory the results. Both Marck et al [65]. and Huijing et al [66]. find this pattern, which combined with Maine’s findings above [53], leads them to recommend against short-term surgical missions for any but the simplest conditions [65, 66].

Cost-effectiveness

With a caveat to be discussed below, the few cost-effectiveness analyses that have been performed on surgical missions point to a beneficial cost-effectiveness ratio: cleft lip and palate repair costs anywhere from $52/DALY averted [67] to $1,827/DALY averted [23], or approximately $40 per patient [41], and benefit-cost analyses are similarly positive [68]. Orthopedic surgeries, at $340-$360/DALY averted, are slightly more expensive buys [38, 69].

These findings, however, must be interpreted with extreme caution, especially because they do not square with the assertion short-term surgical missions tend toward unsatisfactory outcomes. The apparent cost-effectiveness of surgical missions is an artifact of the way in which the analyses were conducted; almost all of the cited studies assume uncomplicated repairs, and all assumed that, without the mission, no surgery occurred. These assumptions will systematically result in a small cost-effectiveness ratio, biasing the analysis toward the charitable organization. As a result, an interpretation of these findings must be very narrow: only when no other platform treats the condition do these results imply that a surgical mission may be cost-effective. If the condition can be treated by other platforms—which, in many cases, it can—these cost-effectiveness results lose validity. This caveat should be combined with the fact that results of these cost-effectiveness studies depend on how the studies were conducted [70].

One cost-effectiveness analysis compared short-term platforms with other platforms for the treatment of one condition; Singh et al [55]. examined cataract surgeries performed at specialized eye camps, NGO hospitals, and the state medical college. Although not the worst value—that distinction fell to the state medical college—short-term eye camps were much less cost-effective than nongovernmental hospitals.

Sustainability and training

Many authors laud the salutary role that short-term surgical missions have in the education of surgical trainees in high-income countries [43, 71–85]. While this role is not to be dismissed, it cannot come at the cost of delivery of unsatisfactory care in LMICs [9, 86]. Besides one study, which documented an increase in laparoscopic surgeries after repeated training missions [17], no other evidence was found for the role of short-term missions in training.

Short-term surgical missions, however, have been put forward as a method to alleviate disease burden in LMICs. Unfortunately, the sustainability of this platform unclear. It is not altogether unlikely, for example, that these surgical camps treat the same conditions that are otherwise treated in local hospitals, and fragmentation in delivery contributes to an inability to meet the large burden of unmet need [87, 88]. The structure of the short-term medical mission itself may be detrimental to sustainability; patients are identified before the surgical team’s arrival, and the large volume of cases performed often disrupts local infrastructure, even after the team’s departure [40, 89].

Finally, although these platforms create awareness of surgery in the communities that they serve [90, 91], this awareness often can have counterintuitively detrimental effects on local infrastructure: when outcomes are consistently good, awareness influences positive health-seeking behavior in patients. Even the most sporadic bad outcomes, however, seem to discourage care-seeking outright [92].

Despite its ubiquity, the short-term surgical safari appears to have a relatively limited role in the delivery of surgical care. Given potentially unsatisfactory results, detrimental effects on health-seeking behavior, and stress on the local infrastructure, the short-term stand-alone surgical mission, when other options exist, is likely to be inefficient [93].

Self-contained surgical platforms

The fact that complex procedures performed by short-term missions can yield unsatisfactory results [65, 66], combined with the fact that most local hospitals also are unable to provide this care consistently [3, 5, 94], leads to an obvious question. While LMICs improve their local infrastructure, how can the interim need be best met? Are specialized surgical hospitals (to be discussed next) the most effective and efficient method, or can a different temporary model, better structured than the short-term mission, provide effective surgical care?

Few examples of an intermediate model for surgical delivery exist, but those that do are promising. Mercy Ships, for example, maintains hospital ships, carrying an entire infrastructure (including pathology and radiology [26]), allowing them to provide ophthalmologic, reconstructive, general, orthopedic, and obstetric fistula surgeries [25, 95]. The few studies on the effectiveness of surgical procedures performed by this platform indicate outcomes comparable with those seen in high-income centers [25]. Military organizations adopt a similar model: the U.S. Navy maintains two hospital ships, which report mortality and complication rates that are equivalent to, if not better than, those found in high-income, country hospitals [96–98]. In addition, complex craniofacial surgeries, for which the short-term platform appears ill-suited, appear to be successfully performed by this platform [99]. There have been no cost-effectiveness evaluations of self-contained delivery platforms to date.

Specialty surgical hospitals

Demand and supply constraints

Specialized surgical hospitals are myriad (see Box 2); many evolved from temporary surgical platforms. Cataract surgeries in India, for example, were initially performed in makeshift facilities before their care transferred to specialized hospitals. A population-based study, however, estimates that patients accessing short-term “eye camps” represent a mere 7 % of those in need [100], and current estimates put resource utilization of eye care facilities at 25 % [101].

Box 2.

Examples of surgical specialty hospitals working in LMICs

| Example surgical specialty hospitals working in low-resource settings |

|---|

| Cardiac |

| Salam Center, Khartoum, Sudan |

| Narayana Hrudayalaya Hospitals, Bangalore, India |

| Innova Children’s Heart Hospital, Hyderabad, India |

| Ophthalmic |

| ORBIS |

| Aravind Eye Hospitals, Tamilnadu, India |

| LRBT Eye Hospitals, Pakistan |

| Obstetric fistula |

| Babbar Ruga Hospital, Katsina, Nigeria |

| Hamlin Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia |

| Danja Fistula Center, Danja, Niger |

| Maternity services |

| Life Spring Hospitals, India |

| Cancer: Adayar Cancer Hospital, Chennai, India |

| Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India |

Research by Browning and Patel, in the setting of obstetric fistula [93], similarly indicates that less than 1 % of surgical need for fistula repair is being met [93]. In Ethiopia alone, an estimated 9,000 women develop an obstetric fistula each year [102, 103]. Similar statements can be made about the unmet need for cardiac surgery, maternity services, and cancer care.

Effectiveness

Data for specialized surgical hospitals come primarily from ophthalmologic, fistula, and cancer centers [104, 105]. Although publications from specialized surgical hospitals treating other conditions exist, none include objective outcome measures [106, 107].

Evidence for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of specialty ophthalmologic hospitals has been presented above [55]; overall, they appear able to deliver high volumes of ophthalmologic surgery effectively [108]. A single publication from an eye hospital in Nigeria, however, reported poor postoperative vision outcomes [109]. Similarly, laparoscopic radical hysterectomy, other obstetric services, and repair of congenital anomalies can both be performed in LMIC specialized hospitals with outcomes similar to those found in the United States [105, 110–113].

Repair of obstetric fistulae is complex. Fistula surgeons are not considered expert until they have performed 300 cases, which may take years in short-term missions or local hospitals [114]. Even expert surgeons deliver closure and continence to only 85 % of patients. Both the Addis Ababa (a charitable organization) and Babbar Ruga (an initiative of the Nigerian government with some external funding) centers, however, report rates of successful fistula closure and return to continence of more than 90 % [115, 116].

Finally, complex surgical conditions, such as obstetric fistula and facial clefting, place specific design demands on the physical facility and require rehabilitative services [102]. While the local or district hospital may meet some of these needs, it must prioritize more life-threatening surgical conditions, making complex repair less likely [117]. In keeping with these findings, a recent expert elicitation study concluded that complicated obstetric fistulae are likely best repaired at high-volume, specialized surgical hospitals [118].

Cost-effectiveness

The single published, cross-platform comparison demonstrates the superior cost-effectiveness of permanent NGO hospitals in cataract surgery [55]. One other cost-effectiveness study published on surgery performed in the larger context of a mission hospital showed a beneficial cost-benefit ratio [119].

Sustainability and training

The Babbar Ruga fistula hospital reports having trained more than 600 fistula surgeons nurses worldwide [116]. Consistent with the above estimates [93], the experience of one author (AS) demonstrates the level of sustainability required for fistula training: the training of two Eritrean fistula surgeons required at least 5 years before competency levels and adequate case numbers were met. This is only possible in specialized platforms.

Discussion

Surgical conditions constitute up to 28 % of the global burden of disease, and the current surgical infrastructure in many low-income countries cannot meet all of it. Access to surgical care is low [93, 101, 120], and most hospitals in LMICs do not treat high-DALY conditions [3]. Simultaneously, a rapidly growing, often fragmented charitable sector has stepped in to meet surgical need—a sector that has not been systematically evaluated [87].

Unfortunately, what evaluations have been done may actually promote fragmentation—examining surgical missions in isolation prevents informative similarities and differences from becoming explicit. We propose, instead, structuring evaluations around platforms for the delivery, not around disease types or individual missions. Doing so highlights the relative impact of models that underpin charitable surgery.

The overall findings from this systematic review are presented in Table 1. The literature suggests that NGOs deliver surgery by either establishing permanent surgical hospitals or in more temporary platforms—which themselves can be self-contained or can rely on local infrastructure.

Table 1.

Summary of results (see text for further details)

| Domain | Platform | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporary, short-term | Temporary, self-contained | Surgical specialty hospital | |

| Effectiveness | Poor results for complex procedures; effective for simple procedures | Potentially equivalent to developed-world outcomes | Equivalent to developed-world outcomes |

| Cost-effectiveness | Cost-effective if serving as the only platform for surgery; unlikely cost-effective otherwise | No data | Most cost-effective of the competing choices |

| Sustainability | Unlikely sustainable; may have a detrimental impact on health-seeking behaviour | No data | Platform suitable for sustainability |

| Training | Effective for training of developed-world surgeons. Little data on training of LMIC surgeons | Platform available for training | Definite role for training of LMIC surgeons |

Sparse data on this platform limit the certainty of these conclusions

The available evidence suggests that, despite its ubiquity, the short-term temporary surgical mission’s role should be limited to areas and conditions for which no other surgical delivery platform is available. In these settings, it delivers care efficiently. In settings in which alternative delivery systems exist, however, it appears much less effective [88]: short-term missions may not reach patients with unmet need [93]; risk delivering unsatisfactory results, especially around complex reconstructions [53, 65, 66]; often stress the local surgical infrastructure [40]; and may discourage health-seeking behavior [92], all of which undermine its sustainability.

In most cost-effectiveness analyses, short-term missions are compared against not providing any surgery and are assumed to be without complication [23, 38, 41, 67]. This overestimates their marginal effectiveness, systematically biasing analyses toward the surgical mission. In analyses in which the short-term platform is compared with other platforms, it becomes less cost-effective [55].

Self-contained temporary platforms are rare, but fit in the negative space between the short-term mission and the specialty hospital. They offer services usually not found in the short-term mission and are able to deliver care comparable to that found specialty hospitals in both LMICs and high-income countries [25, 26]. Cost-effectiveness studies have yet to be performed on this platform of delivery.

Finally, the literature suggests that specialized surgical centers might be effective in providing a high volume of care with good outcomes [115, 116]. Simultaneously, these permanent platforms are able to provide for some of the unique needs faced by patients with more complex conditions [102, 117, 121], and do so sustainably. One cost-effectiveness analysis demonstrates their increased efficiency over short-term camps [55], but further cost-effectiveness analyses are necessary.

This review is the first to attempt a broad, systematic evaluation of charitable surgical delivery in LMICs, distinct from the conditions treated and the individual organizations that treat them. As such, it has certain limitations. It should be noted, for example, that any taxonomy is leaky. Some organizations that establish hospitals and send short-term missions trips to other countries, some of the self-contained organizations have themselves established hospitals. That no classification system can adequately characterize any NGO does not, however, mean that research into these organizations must remain fragmented. This taxonomy, leaky though it may be, proposes a structure for future research into a large sector of the health system.

The peer-reviewed literature in this area is small, all outcomes studies are case series, and nearly all the cost-effectiveness are predicated on relatively heroic assumptions. In addition, although some studies do show less-than-optimal results, publication bias very likely exists. More importantly, a lack of evidence does not imply evidence of a lack. Many surgeons in LMICs, in addition to surgeons who work with these charitable organizations, have little time to devote to producing peer-reviewed publications. As such, a dearth of evidence exists as to the comparative effectiveness of NGO platforms and local hospitals within the same setting. This dearth highlights the need for further investigation into the effectiveness of surgery as delivered in these settings, as well as the potential role other research methods—such as realist synthesis—in the study of surgical delivery by charities in low- and middle-income countries.

Finally, of the domains along which delivery platforms were evaluated (cost-effectiveness, effectiveness, sustainability, and training), the former is controversial, especially given the various platforms used. Some organizations, for example, work entirely with volunteer staff; others pay. As such, these studies must be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the classification scheme in this review allows for the first systematic evaluation of disparate charitable organizations. The charitable sector is large and spends a significant amount of donor money [6]. Limitations in the literature highlight the obvious need for more, and larger, evaluations of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of this sector’s role in the delivery of surgical care in LMICs. Determining the most effective platform for surgery stands to benefit patients, for whom this is often the only affordable avenue of care, while determining the most cost-effective platform stands also to align donor interests with those of the patients they seek to help. Finally, structuring future research around surgical delivery platforms will help in decreasing the fragmentation found in the nongovernmental world [3].

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Dr. Peggy Lai, Sweta Adhikari, and Dr. Vittoria Lutje for help in the literature search.

Conflicts of interest and sources of funding

TR is the director of operations of the Aravind Eye Care System. No other financial conflicts of interest are declared.

References

- 1.(2012) Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease, 2010

- 2.Chao TE, Burdic M, Ganjawalla K, et al. Survey of surgery and anesthesia infrastructure in Ethiopia. World J Surg. 2012;36:2545–2553. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1729-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ilbawi AM, Einterz EM, Nkusu D. Obstacles to surgical services in a rural cameroonian district hospital. World J Surg. 2013;37:1208–1215. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1977-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowlton LM, Chackungal S, Dahn B, LeBrun D, Nickerson J, McQueen K. Liberian surgical and anesthesia infrastructure: a survey of county hospitals. World J Surg. 2013;37:721–729. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1903-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linden AF, Sekidde FS, Galukande M, Knowlton LM, Chackungal S, McQueen KA. Challenges of surgery in developing countries: a survey of surgical and anesthesia capacity in Uganda’s public hospitals. World J Surg. 2012;36:1056–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1482-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casey KM. The global impact of surgical volunteerism. Surg Clin N Am. 2007;87:949–960. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isaacson G, Drum ET, Cohen MS. Surgical missions to developing countries: Ethical conflicts. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143:476–479. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ott BB, Olson RM. Ethical issues of medical missions: the clinicians’ view. HEC Forum. 2011;23:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s10730-011-9154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wall LL. Ethical concerns regarding operations by volunteer surgeons on vulnerable patient groups: the case of women with obstetric fistulas. HEC Forum. 2011;23:115–127. doi: 10.1007/s10730-011-9153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider WJ, Migliori MR, Gosain AK, Gregory G, Flick R. Volunteers in plastic surgery guidelines for providing surgical care for children in the less developed world: part II. Ethical considerations. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:216e–222e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822213b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai VT, Murali V, Kim R, Srivatsa SK. Teleophthalmology-based rural eye care in India. Telemed J E-Health. 2007;13:313–321. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailie R. An economic appraisal of a mobile cervical cytology screening service. South Afr Med J. 1996;86:1179–1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodas E, Vicuna A, Merrell RC. Intermittent and mobile surgical services: logistics and outcomes. World J Surg. 2005;29:1335–1339. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7632-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu KM, Ford N, Trelles M. Operative mortality in resource-limited settings: the experience of Medecins Sans Frontieres in 13 countries. Arch Surg (Chicago, Ill: 1960) 2010;145:721–725. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nickerson JW, Chackungal S, Knowlton L, McQueen K, Burkle FM. Surgical care during humanitarian crises: a systematic review of published surgical caseload data from foreign medical teams. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2012;27:184–189. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X12000556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gil J, Rodriguez JM, Hernandez Q, et al. Do hernia operations in international cooperation programmes provide good quality? World J Surg. 2012;36:2795–2801. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1768-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vargas G, Price RR, Sergelen O, Lkhagvabayar B, Batcholuun P, Enkhamagan T. A successful model for laparoscopic training in Mongolia. Int Surg. 2012;97:363–371. doi: 10.9738/CC103.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Int Med. 2009;151:264–269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bermudez L, Carter V, Magee W, Jr, Sherman R, Ayala R. Surgical outcomes auditing systems in humanitarian organizations. World J Surg. 2010;34:403–410. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0253-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bermudez L, Trost K, Ayala R. Investing in a surgical outcomes auditing system. Plast Surg Int. 2013;2013:671786. doi: 10.1155/2013/671786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magee WP., Jr Evolution of a sustainable surgical delivery model. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:1321–1326. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181ef2a6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magee WP, Raimondi HM, Beers M, Koech MC. Effectiveness of international surgical program model to build local sustainability. Plast Surg Int. 2012;2012:185725. doi: 10.1155/2012/185725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magee WP, Jr, Vander Burg R, Hatcher KW. Cleft lip and palate as a cost-effective health care treatment in the developing world. World J Surg. 2010;34:420–427. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0333-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cousins GR, Obolensky L, McAllen C, Acharya V, Beebeejaun A. The Kenya orthopaedic project: surgical outcomes of a travelling multidisciplinary team. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:1591–1594. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B12.29920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng LH, McColl L, Parker G. Thyroid surgery in the UK and on board the Mercy Ships. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50:592–596. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris RD. Radiology on the Africa Mercy, the largest private floating hospital ship in the world. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:W124–W129. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McQueen KA, Hyder JA, Taira BR, Semer N, Burkle FM, Jr, Casey KM. The provision of surgical care by international organizations in developing countries: a preliminary report. World J Surg. 2010;34:397–402. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balent LC, Narendrum K, Patel S, Kar S, Patterson DA. High-volume sutureless intraocular lens surgery in a rural eye camp in India. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2001;32:446–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Civerchia L, Apoorvananda SW, Natchiar G, Balent A, Ramakrishnan R, Green D. Intraocular lens implantation in rural India. Ophthalmic Surg. 1993;24:648–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Civerchia L, Ravindran RD, Apoorvananda SW, et al. High-volume intraocular lens surgery in a rural eye camp in India. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1996;27:200–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kapoor H, Chatterjee A, Daniel R, Foster A. Evaluation of visual outcome of cataract surgery in an Indian eye camp. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:343–346. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.3.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Hoek J. Three months follow-up of IOL implantation in remote eye camps in Nepal. Int Ophthalmol. 1997;21:195–197. doi: 10.1023/a:1016010915622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venkataswamy G. Massive eye relief project in India. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;79:135–140. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90471-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehnerdt G, van Delden A, Lautermann J. Management of an “Ear Camp” for children in Namibia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:663–668. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders DL, Kingsnorth AN. Operation hernia: humanitarian hernia repairs in Ghana. Hernia. 2007;11:389–391. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0238-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tefuarani N, Vince J, Hawker R, et al. Operation open heart in PNG, 1993-2006. Heart Lung Circ. 2007;16:373–377. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rumstadt B, Klein B, Kirr H, Kaltenbach N, Homenu W, Schilling D. Thyroid surgery in Burkina Faso, West Africa: experience from a surgical help program. World J Surg. 2008;32:2627–2630. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9775-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gosselin RA, Gialamas G, Atkin DM. Comparing the cost-effectiveness of short orthopedic missions in elective and relief situations in developing countries. World J Surg. 2011;35:951–955. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0947-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frampton MC. Otological relief work in Romania. J Laryngal Otol. 1993;107:1185–1189. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100125630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nthumba PM. “Blitz surgery”: redefining surgical needs, training, and practice in sub-Saharan Africa. World J Surg. 2010;34:433–437. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hodges AM, Hodges SC. A rural cleft project in Uganda. Br J Plast Surg. 2000;53:7–11. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Buys Roessingh AS, Dolci M, Zbinden-Trichet C, Bossou R, Meyrat BJ, Hohlfeld J. Success and failure for children born with facial clefts in Africa: a 15-year follow-up. World J Surg. 2012;36:1963–1969. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1607-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haskell A, Rovinsky D, Brown HK, Coughlin RR. The University of California at San Francisco international orthopaedic elective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;396:12–18. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruiz-Razura A, Cronin ED, Navarro CE. Creating long-term benefits in cleft lip and palate volunteer missions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:195–201. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200001000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wright IG, Walker IA, Yacoub MH. Specialist surgery in the developing world: luxury or necessity? Anaesthesia. 2007;62(Suppl 1):84–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeow VK, Lee ST, Lambrecht TJ, et al. International task force on volunteer cleft missions. J Craniofac Surg. 2002;13:18–25. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennberg DE. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117–2127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eskander A. Volume-outcome relationships in the surgical management of head and neck cancer in Ontario. Toronto: Harvard School of Public Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poilleux J, Lobry P. Surgical humanitarian missions. An experience over 18 years. Chirurgie. 1991;117:602–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodgers A, Walker N, Schug S, et al. Reduction of postoperative mortality and morbidity with epidural or spinal anaesthesia: results from overview of randomised trials. BMJ. 2000;321:1493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7275.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sykes KJ, Le PT, Sale KA, Nicklaus PJ. A 7-year review of the safety of tonsillectomy during short-term medical mission trips. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:752–756. doi: 10.1177/0194599812437317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maine RG, Hoffman WY, Palacios-Martinez JH, Corlew DS, Gregory GA. Comparison of fistula rates after palatoplasty for international and local surgeons on surgical missions in Ecuador with rates at a craniofacial center in the United States. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:319e–326e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31823aea7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Furr MC, Larkin E, Blakeley R, Albert TW, Tsugawa L, Weber SM. Extending multidisciplinary management of cleft palate to the developing world. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.06.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh AJ, Garner P, Floyd K. Cost-effectiveness of public-funded options for cataract surgery in Mysore, India. Lancet. 2000;355:180–184. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07430-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Homoe P, Nikoghosyan G, Siim C, Bretlau P. Hearing outcomes after mobile ear surgery for chronic otitis media in Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67:452–460. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v67i5.18352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Homoe P, Siim C, Bretlau P. Outcome of mobile ear surgery for chronic otitis media in remote areas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Snidvongs K, Vatanasapt P, Thanaviratananich S, Pothaporn M, Sannikorn P, Supiyaphun P. Outcome of mobile ear surgery units in Thailand. J Laryngal Otol. 2010;124:382–386. doi: 10.1017/S0022215109991836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Horlbeck D, Boston M, Balough B, et al. Humanitarian otologic missions: long-term surgical results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barrs DM, Muller SP, Worrndell DB, Weidmann EW. Results of a humanitarian otologic and audiologic project performed outside of the United States: lessons learned from the “Oye, Amigos!” project. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:722–727. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.110959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adams C, Kiefer P, Ryan K, et al. Humanitarian cardiac care in Arequipa, Peru: experiences of a multidisciplinary Canadian cardiovascular team. Can J Surg. 2012;55:171–176. doi: 10.1503/cjs.029910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim FS, Tran HH, Sinha I, et al. Experience with corrective surgery for postburn contractures in Mumbai, India. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:e120–e126. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182335a00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Young S, Lie SA, Hallan G, Zirkle LG, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Low infection rates after 34,361 intramedullary nail operations in 55 low- and middle-income countries: Validation of the Surgical Implant Generation Network (SIGN) Online Surgical Database. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:737–743. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.636680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Young S, Lie SA, Hallan G, Zirkle LG, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Risk factors for infection after 46,113 intramedullary nail operations in low- and middle-income countries. World J Surg. 2013;37:349–355. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marck R, Huijing M, Vest D, Eshete M, Marck K, McGurk M. Early outcome of facial reconstructive surgery abroad: a comparative study. Eur J Plast Surg. 2010;33:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s00238-010-0409-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huijing MA, Marck KW, Combes J, et al. Facial reconstruction in the developing world: a complicated matter. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;49:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2009.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moon W, Perry H, Baek RM. Is international volunteer surgery for cleft lip and cleft palate a cost-effective and justifiable intervention? A case study from East Asia. World J Surg. 2012;36:2819–2830. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1761-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hughes CD, Babigian A, McCormack S, et al. The clinical and economic impact of a sustained program in global plastic surgery: valuing cleft care in resource-poor settings. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:87e–94e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318254b2a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen AT, Pedtke A, Kobs JK, Edwards GS, Jr, Coughlin RR, Gosselin RA. Volunteer orthopedic surgical trips in Nicaragua: a cost-effectiveness evaluation. World J Surg. 2012;36:2802–2808. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1702-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lansingh VC, Carter MJ, Martens M. Global cost-effectiveness of cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1670–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alterman DM, Goldman MH. International volunteerism during general surgical residency: a resident’s experience. J Surg Educ. 2008;65:378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aziz SR, Ziccardi VB, Chuang SK. Survey of residents who have participated in humanitarian medical missions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:e147–e157. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Belyansky I, Williams KB, Gashti M, Heitmiller RF. Surgical relief work in Haiti: a practical resident learning experience. J Surg Educ. 2011;68:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Boyd NH, Cruz RM. The importance of international medical rotations in selection of an otolaryngology residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3:414–416. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00185.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cameron BH, Rambaran M, Sharma DP, Taylor RH. International surgery: the development of postgraduate surgical training in Guyana. Can J Surg. 2010;53:11–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Campbell A, Sherman R, Magee WP. The role of humanitarian missions in modern surgical training. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:295–302. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181dab618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Campbell A, Sullivan M, Sherman R, Magee WP. The medical mission and modern cultural competency training. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Henry JA, Groen RS, Price RR, et al. The benefits of international rotations to resource-limited settings for U.S. surgery residents. Surgery. 2013;153:445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hughes C, Wong A, McCormack S, et al. International efforts in plastic surgery: the Hartford Hospital, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center and University of Connecticut experience in Ecuador. Connecticut Med. 2012;76:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hughes C, Zani S, O’Connell B, Daoud I. International surgery and the University of Connecticut experience: lessons from a short-term surgical mission. Connecticut Med. 2010;74:157–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jarman BT, Cogbill TH, Kitowski NJ. Development of an international elective in a general surgery residency. J Surg Educ. 2009;66:222–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee DK, Weinstein S. International public health in third world country medical missions: when small legs walk, we all stand a little taller. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2009;99:371–376. doi: 10.7547/0980371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Matar WY, Trottier DC, Balaa F, Fairful-Smith R, Moroz P. Surgical residency training and international volunteerism: a national survey of residents from 2 surgical specialties. Can J Surg. 2012;55:S191–S199. doi: 10.1503/cjs.005411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ozgediz D, Roayaie K, Debas H, Schechter WS, Farmer D. Surgery in developing countries: essential training in residency. Arch Surg (Chicago, Ill: 1960) 2005;140:795–800. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.8.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ozgediz D, Wang J, Jayaraman S, et al. Surgical training and global health: initial results of a 5-year partnership with a surgical training program in a low-income country. Arch Surg (Chicago, Ill: 1960) 2008;143:860–865. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.9.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Riviello R, Lipnick M, Ozgediz D. Medical missions, surgical education, and capacity building. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:572–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.06.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Butler MW. Fragmented international volunteerism: need for a global pediatric surgery network. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cam C, Karateke A, Ozdemir A, et al. Fistula campaigns–are they of any benefit? Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;49:291–296. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(10)60063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mitchell KB, Balumuka D, Kotecha V, Said SA, Chandika A. Short-term surgical missions: joining hands with local providers to ensure sustainability. South Afr J Surg. 2012;50:2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Donkor P, Bankas DO, Agbenorku P, Plange-Rhule G, Ansah SK. Cleft lip and palate surgery in Kumasi, Ghana: 2001-2005. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1376–1379. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000246504.09593.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Uetani M, Jimba M, Niimi T, et al. Effects of a long-term volunteer surgical program in a developing country: the case in Vietnam from 1993 to 2003. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43:616–619. doi: 10.1597/05-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fletcher A, Donoghue M, Devavaram J, et al. Low uptake of eye services in rural India: a challenge for programs of blindness prevention. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1393–1399. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.10.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Browning A, Patel TL. FIGO initiative for the prevention and treatment of vaginal fistula. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;86:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hsia RY, Mbembati NA, Macfarlane S, Kruk ME. Access to emergency and surgical care in sub-Saharan Africa: the infrastructure gap. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:234–244. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lewis G, de Bernis L (2006) Obstetric fistula: guiding principles for clinical management and programme development. Periodical [serial online]. World Health Organization. Accessed 7 July 2013

- 96.Troup L. The USNS Mercy’s Southeast Asia humanitarian cruise: the perioperative experience. AORN J. 2007;86:781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Walk RM, Donahue TF, Sharpe RP, Safford SD. Three phases of disaster relief in Haiti–pediatric surgical care on board the United States Naval Ship Comfort. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:1978–1984. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Walk RM, Glaser J, Marmon LM, Donahue TF, Bastien J, Safford SD. Continuing promise 2009—assessment of a recent pediatric surgical humanitarian mission. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ray JM, Lindsay RW, Kumar AR. Treatment of earthquake-related craniofacial injuries aboard the USNS Comfort during Operation Unified Response. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:2102–2108. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f5272d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fletcher A, Vijaykumar V, Selvaraj S, Thulasiraj RD, Ellwein LB. The Madurai Intraocular Lens Study. III: Visual functioning and quality of life outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:26–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.World Health Organization (2005) State of the world’s sight: VISION 2020: the right to sight 1999-2005. Periodical [serial online]. Accessed 7 July 2013

- 102.Hamlin EC, Muleta M, Kennedy RC. Providing an obstetric fistula service. Br J Urol Int. 2002;89:50–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1465-5101.2001.129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Muleta M, Rasmussen S, Kiserud T. Obstetric fistula in 14,928 Ethiopian women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:945–951. doi: 10.3109/00016341003801698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Frajzyngier V, Ruminjo J, Barone MA. Factors influencing urinary fistula repair outcomes in developing countries: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pareja R, Nick AM, Schmeler KM, et al. Quality of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy in developing countries: a comparison of surgical and oncologic outcomes between a comprehensive cancer center in the United States and a cancer center in Colombia. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:326–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Reddy SG, Reddy LV, Reddy RR. Developing and standardizing a center to treat cleft and craniofacial anomalies in a developing country like India. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:1664–1667. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181b2d6c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Youssef A, Harrison WJ. Establishing a children’s orthopedic hospital for Malawi: an assessment after 5 years. Malawi Med J. 2010;22:75–78. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v22i3.62192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Venkatesh R, Muralikrishnan R, Balent LC, Prakash SK, Prajna NV. Outcomes of high volume cataract surgeries in a developing country. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1079–1083. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.063479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ezegwui IR, Ajewole J. Monitoring cataract surgical outcome in a Nigerian mission hospital. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29:7–9. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Del Rossi C, Attanasio A, Del Curto S, D’Agostino S, De Castro R. Treatment of vaginal atresia at a missionary hospital in Bangladesh: results and followup of 20 cases. J Urol. 2003;170:864–866. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000081425.66782.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Del Rossi C, Attanasio A, Domenichelli V, De Castro R. Treatment of the Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome in Bangladesh: results of 10 total vaginal replacements with sigmoid colon at a missionary hospital. J Urol. 1999;162:1138–1139. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)68099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Del Rossi C, Fontechiari S, Casolari E, Fainardi V, Caravaggi F, Lombardi L. Treatment of congenital anomalies in a missionary hospital in Bangladesh: results of 17 paediatric surgical missions. Acta Bio Med. 2008;79:260–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Vogel JP, Betran AP, Widmer M, et al. Role of faith-based and nongovernment organizations in the provision of obstetric services in 3 African countries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:e491–e497. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2011) Global competency-based fistula surgery training manual. Periodical [serial online]. Accessed 7 July 2013

- 115.Muleta M. Obstetric fistulae: a retrospective study of 1210 cases at the Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;17:68–70. doi: 10.1080/01443619750114194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Waaldijk K (2008) Obstetric fistula surgery: art and science: basics. Waaldijk

- 117.Wall LL. Where should obstetric vesico-vaginal fistulas be repaired: At the district general hospital or a specialized fistula center? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:S28–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Colson A, Adhikari S, Sleemi A, Laxminarayan R (2013) Quantifying uncertainty in intervention effectiveness: an application in obstetric fistula [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 119.Gosselin R, Thind A, Bellardinelli A. Cost/DALY averted in a small hospital in Sierra Leone: what is the relative contribution of different services? World J Surg. 2006;30:505–511. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0609-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Brilliant LB, Pokrel RP, Grasset NC, et al. Epidemiology of blindness in Nepal. Bull World Health Organ. 1985;63:375–386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wall LL, Arrowsmith SD, Lassey AT, Danso K. Humanitarian ventures or ‘fistula tourism?’: the ethical perils of pelvic surgery in the developing world. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:559–562. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-0056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]