Abstract

To evaluate the association between economic indicators (unemployment and mortgage foreclosure rates) and volume of investigated and substantiated cases of child maltreatment at the county level from 1990 to 2010 in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. County-level investigated reports of child maltreatment and proportion of investigated cases substantiated by child protective services in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania were compared with county-level unemployment rates from 1990 to 2010, and with county-level mortgage foreclosure rates from 2000 to 2010. We employed fixed-effects Poisson regression modeling to estimate the association between volume of investigated and substantiated cases of maltreatment, and current and prior levels of local economic indicators adjusting for temporal trend. Across Pennsylvania, annual rate of investigated maltreatment reports decreased through the 1990s and rose in the early 2000s before reaching a peak of 9.21 investigated reports per 1,000 children in 2008, during the recent economic recessionary period. The proportion of investigated cases substantiated, however, decreased statewide from 33 % in 1991 to 15 % in 2010. Within counties, current unemployment rate, and current and prior-year foreclosure rates were positively associated with volume of both investigated and substantiated child maltreatment incidents (p < 0.05). Despite recent increases in investigations, the proportion of investigated cases substantiated decreased by more than half from 1990 to 2010 in Pennsylvania. This trend suggests significant changes in substantiation standards and practices during the period of study. Economic indicators demonstrated strong association with investigated and substantiated maltreatment, underscoring the urgent need for directing important prophylactic efforts and resources to communities experiencing economic hardship.

Keywords: Child safety, Child maltreatment, Child abuse, Unemployment, Foreclosure

Background

During the past two decades, America experienced three economic recessions (July 1990–March 1991; March– November 2001; December 2007–June 2009) [1] and a housing foreclosure crisis of unprecedented magnitude. In the most recent recession alone, 6.6 million Americans joined the ranks of the unemployed, and over 6 million homeowners lost or were at serious risk of losing their homes [2, 3]. The stress endured by families during these times of economic hardship raised concern that increased numbers of children may have been at risk for child maltreatment.

A strong association between measures of family socioeconomic status and child maltreatment risk has been well established in the literature, even with evidence of a causal effect documented [4–9]. A relationship between community-level economic stressors and child maltreatment has also been demonstrated [10–16]. In analysis of neighborhood characteristics, level of poverty was the only factor consistently related to maltreatment risk among both African–American children and white counterparts [17]. The strong association between child maltreatment and poverty at the levels of the family and community might lead us to believe that rates of child maltreatment would rise during periods of economic downturns. Contrary to this expectation, however, increases in rates of child maltreatment during periods of economic recession have not been observed. In fact, data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) suggest the opposite trend. Between 1990 and 2010, a period during which the country experienced three recessions, national rates of substantiated child physical abuse and child sexual abuse declined by over 50 %, with a smaller decrease observed in cases of neglect [18, 19]. The drop in rates of child maltreatment incidences investigated and confirmed by child protective services (CPS) during periods of economic recession has raised questions about the nature of the association between changes in the economy and child maltreatment rates.

Longitudinal research supporting a clear relationship between trends in local economic indices, particularly unemployment and foreclosure rates, and changes in child maltreatment rates is scarce [20–22]. Cohort studies of the relationship between changes in local unemployment and child maltreatment rates over time presented mixed results. Two older studies reported that increase in unemployment rates in communities was associated with higher child abuse rates, but another study found that at least in one community, rise in unemployment coincided with decrease in child abuse rates [23–25]. A more recent study of the effect of unemployment rates, labor force participation, and food stamp usage on child maltreatment incidence in seven US states did not find a strong relationship between these economic indices and volume of child maltreatment incidents, as measured by aggregate number of screened-in reports at the state level [22]. Two studies on a smaller scale did describe increased occurrence of a specific type of child abuse, abusive head trauma (AHT), during the most recent economic recession, in comparison to the pre-recession period [21, 26]. One of these studies examined but could not establish a statistically significant relationship between increase in unemployment rates during the recessionary period and observed rise in AHT rates [21]. Much less is known about the relationship between home foreclosure rates and child maltreatment rates, although a single study did report significant association between admissions for physical abuse to pediatric hospitals and local home foreclosure rates [20].

To better understand the association at the local level between economic indicators and incidence of child maltreatment during a period punctuated by significant macroeconomic pressures, we examined the relationship between trends in local unemployment and home foreclosures rates, and frequency of child maltreatment incidents in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, a large mid-Atlantic state with urban and rural counties, over a 21-year period. The objectives of this study were: (1) to describe trends in investigated reports and substantiated cases of child maltreatment in Pennsylvania counties from 1990 to 2011; and (2) to examine the association of unemployment and mortgage foreclosure rates with volume of both investigated and substantiated cases of child maltreatment within these counties over the same period.

Methods

Data Sources

The targets of analysis in this study were the 67 counties of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania between 1990 and 2010. County-level analysis was pursued in recognition of the impact of local area effects and contextual heterogeneity on the relationship between the selected economic indicators and child maltreatment incidence. Limiting analysis to a single state helped to ensure a uniform definition of child maltreatment and consistency in standards of intake and screening of alleged abuse across counties for the period of study. This approach also permitted study of aggregate associations of socioeconomic measures with child maltreatment in a geographically heterogeneous setting which included rural locations, as most of the existing research is focused on urban settings. Child protective services (CPS) law in Pennsylvania, unlike in other states, separates lower risk maltreatment, such as neglect and truancy, from physical and sexual abuse at the time a report is made, minimizing the confounding effect of poverty-associated neglect in the relationship between economic indicators and child maltreatment.

Data on investigated reports and substantiated cases of child maltreatment in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania were obtained from the Pennsylvania Department of Public Welfare’s annual Child Abuse Reports. Reports of suspected child maltreatment are managed through the Pennsylvania Department of Public Welfare’s ChildLine and Abuse Registry, which serves as the Commonwealth’s central clearinghouse for child abuse reports. Reports of suspected child abuse received by ChildLine and county hotlines are screened, and cases with allegations of non-accidental injury, sexual abuse, or serious neglect are referred to county CPS agencies for investigation. Pennsylvania Child Protective Services Law (23 PA CS § 6,303; 55 PA Code §3,490.4) distinguishes CPS reports from general protective services (GPS) reports, which include reports of lower risk maltreatment, such as chronic truancy, neglect, and poor parental supervision. Reports for which investigations confirm the allegation of abuse are referred to as “substantiated.” Total CPS reports accepted for investigation, number of substantiated CPS investigations, and population data for children <18 years old were obtained for each Pennsylvania county for each year between 1990 and 2010.

Information on county- and state-level unemployment rates for each year of the study period was collected from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Local Area Unemployment Statistics Database [27]. County-level mortgage foreclosure data were sourced from CoreLogic, Inc. (McLean, VA), a real estate data and analytics company that collects property address-level data from public records at county recorders’ offices, courthouse filings, tax assessors, sheriffs’ offices, newspaper filings, proprietary sources and selected vendors for the number of new and outstanding unique notices of default, and for notices of trustee sales. CoreLogic’s broad coverage includes over 140 million properties and 99 % of the U.S. population [28].

This study analyzed county-level data without identifiers and did not meet the definition of human subjects research or require Institutional Review Board oversight.

Study Measures

The unit of analysis employed was the county-year. The primary study outcomes were the annual counts of maltreatment reports investigated and the annual count of investigations substantiated by the CPS in each county. The primary predictor variables were current and prior-year rates of unemployment and mortgage foreclosure for each county-year.

Statistical Analyses

Trends in rates of investigated CPS reports and substantiated CPS investigations per 1,000 child population were described using median-spline plots. We calculated Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients between annual unemployment rates (current and prior-year), and rates of CPS investigations and substantiations per 1,000 children at the state level. We repeated these analyses substituting unemployment rates with foreclosure rates. Then, using total number of investigated reports as outcome and child population as offset, we estimated within-county association of change in volume of investigations with change in levels of economic indicators by means of fixed-effects Poisson regression. The regression model included year and county-year unemployment rate as independent variables in order to test the association between investigated reports of maltreatment and this economic indicator, controlling for temporal trends. Similar models were repeated with addition of squared and square root variants of year to also test for non-linear associations of the dependent variable with time. This model was re-computed substituting foreclosure rate for unemployment rate. Sensitivity analyses explored the association between investigated CPS reports and unemployment and foreclosure rates of the prior year (first lag). All analyses were then repeated using count of substantiated CPS investigations as the outcome. Standard errors for coefficients were computed using the sandwich estimator and adjusted for clustering within counties. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Study Population

During the 21-year study period from 1990 to 2010, we observed an average of 2,858,216 children under 18 years of age residing in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania each year. Statewide, child population rose from 2.81 million in 1990 to a peak of 2.92 million in 2000, before dropping by 6.2 % to 2.74 million in 2010.

Trends in Investigated and Substantiated Reports of Child Maltreatment Over Time

A total of 500,896 reports were investigated by CPS agencies of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties over the study period (annual mean: 23,876). An average of 8.4 CPS investigations per 1,000 children were launched each year. 116,939 (23.3 %) investigations were substantiated, for an annual average of 1.9 substantiations per 1,000 children.

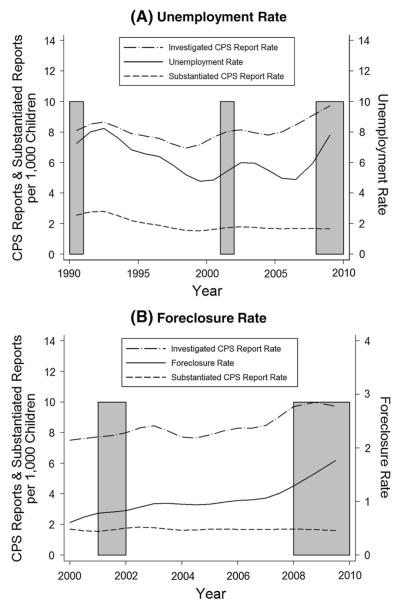

The volume of CPS investigations varied across and within counties over time. In the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, unadjusted rate of CPS investigations demonstrated a quadratic trend over time (p < 0.001), decreasing by 10.3 % from 8.7 investigations per 1,000 children in 1990 to a low of 7.8 in 2000, and rising to a peak of 9.2 in 2008. This peak, which occurred during the recent economic recession, represented 18 % increase over the rate in year 2000 (Fig. 1). At the county level, average annual CPS investigations per 1,000 children were highest in both urban (Philadelphia, 13.3) and non-urban (McKean, 17.5; Venango, 14.1; Forest, 13.7) counties. The lowest CPS investigation rates were observed in urban Montgomery (mean of 4.2 investigations per 1,000 children per year), Beaver (5.1) and Bucks (5.2) counties, and in non-urban Franklin (4.8) and Elk (4.9) counties as well. Within each county, we observed variation in annual rates of CPS investigations during the 21 years of study. Mean range (difference between maximum and minimum levels) of annual CPS investigations per 1,000 children among counties was 6.9, and the maximum range was 22.5 observed in Forest County, where the rate increased more than four-fold from a minimum of 6.2 investigations per 1,000 children in 1998 to a maximum of 28.7 in 2008.

Fig. 1.

Trends in child maltreatment incidence and substantiation and economic indicators for Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (1990–2010). Median-spline plots of aggregate rates of child maltreatment and relevant economic measures are presented. The shaded boxes show years of nationwide recession (1990, 2001, 2008 and 2009) characterized by ≥2 business cycle contractionary quarters, as determined by announcements of the National Bureau of Economic Research [1]

During the 21-year study period, the aggregate trend of substantiated investigations per 1,000 children across the 67 counties was generally declining (p < 0.001). Similar to the trend in investigated CPS reports, the statewide rate of substantiated investigations decreased from 2.8 substantiations per 1,000 children in 1990 to 1.7 in 2000. Unlike with CPS investigations, however, the rate of substantiations continued to decline after year 2000, reaching a low of 1.3 substantiated investigations per 1,000 children in 2010 (Fig. 1). The proportion of investigated CPS reports that were substantiated decreased from 32.6 % in 1990 to 21.9 % in 2000 to 14.9 % in 2010 (Fig. 2). Over the study period, urban Philadelphia (4.1) and non-urban Forest (5.5), McKean (4.2), Tioga (3.8) and Northumberland (3.6) counties had the highest mean annual substantiation rates per 1,000 children, while urban Bucks (0.7), Montgomery (0.7), Chester (0.9), Delaware (1.1), Butler (1.1) and non-urban Franklin (1.1) counties had the lowest rates of substantiated CPS investigations.

Fig. 2.

Aggregate trend of child abuse incidence substantiation rates in Pennsylvania, 1990–2010. Annual aggregate proportions of CPS reports substantiated in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania are presented

Association Between Unemployment Rate and Volume of Investigated and Substantiated Reports of Maltreatment Within Counties

Annual statewide unemployment rate ranged from 4.2 % in 2000 to 8.7 % in 2010. Within counties, unemployment rates also varied with time: between 2008 and 2009 alone, the median change in unemployment rate per county was 3.0 percentage-points (range: −0.2 to 8.3). Coefficient of correlation between unemployment rate and CPS investigations per 1,000 children was positive and significant (ρ = 0.27; 95 % CI 0.22, 0.32). We computed similar correlation between unemployment rate of the previous year and current rate of CPS investigations per 1,000 children (ρ = 0.22; 95 % CI 0.17, 0.27). Coefficients of correlation of current and prior-year unemployment rates with substantiated investigations per 1,000 children were 0.34 (95 % CI 0.29, 0.38) and 0.35 (95 % CI 0.31, 0.40) respectively.

Within counties, 1 percentage-point increase in the current rate of unemployment was associated with 2.0 % (p < 0.001) increase in the count of CPS investigations, and 2.4 % (p = 0.009) increase in substantiated CPS investigations, controlling for temporal effects (Table 1). The association of prior-year unemployment rate with number of CPS investigations (incidence rate ratio, IRR = 1.01, p = 0.12) or substantiations was not significant (IRR = 1.01, p = 0.51).

Table 1.

Association between economic indicators and maltreatment incidence

| Investigated CPS reports | Substantiated CPS reports | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current unemployment rate | 1.99 % (95 % CI 1.10–2.88 %) | p < 0.001 | 2.42 % (95 % CI 0.59–4.29 %) | p = 0.009 |

| Current foreclosure rate | 3.94 % (95 % CI 0.22–7.79 %) | p = 0.038 | 4.49 % (95 % CI 1.14–7.94 %) | p = 0.008 |

| Lagged (1-year) unemployment rate | 1.04 % (95 % CI −0.27–2.37 %) | p = 0.120 | 0.91 % (95 % CI −1.78–3.67 %) | p = 0.512 |

| Lagged (1-year) foreclosure rate | 6.34 % (95 % CI 2.25–10.59 %) | p = 0.002 | 7.30 % (95 % CI 1.89–13.00 %) | p = 0.008 |

Estimates from fixed-effects Poisson regression of counts of child maltreatment reports and substantiations on current and prior-year unemployment and foreclosure rates are presented, representing change in investigated CPS reports/substantiated CPS reports given 1 percentage-point increase in respective economic indicator and adjusted for temporal trend

The estimated 2.4 % increase in count of substantiated investigations for each 1 percentage-point change in the unemployment rate from the prior year translates to 7.2 % increase in substantiated investigations for a county experiencing 3.0 percentage-point increase in unemployment rate (median for 2008–2009). For a county experiencing 8.3 percentage-point increase in unemployment rate (maximum observed), this model predicts 19.9 % increase in substantiated investigations.

Association Between County Foreclosure Rate and Volume of Investigated and Substantiated Reports of Maltreatment Within Counties

Data on county foreclosure rates was available for only 11 years (2000–2010). The variation in annual statewide foreclosure rates for these years was smaller than for unemployment rate (ranging from 0.76 % in 2000–2.12 % in 2010). Coefficient of correlation between current foreclosure rate and CPS investigations per 1,000 children was 0.36 (95 % CI 0.29, 0.42). Correlation between foreclosure rate of the previous year and current rate of CPS investigations per 1,000 children was 0.37 (95 % CI 0.30, 0.43). Correlations of current and prior-year foreclosure rates with current substantiation rates per 1,000 children were 0.18 (95 % CI 0.11, 0.25) and 0.22 (95 % CI 0.15, 0.29).

Within counties, 1 percentage-point increase in current foreclosure rate was associated with 3.9 % increase (p = 0.04) in CPS investigations, controlling for temporal effects. Similarly, 1 percentage-point increase in the prior-year foreclosure rate was associated with 6.3 % increase (p = 0.002) in current CPS investigations (Table 1). 1 percentage-point increase in current foreclosure rate was associated with 4.5 % (p = 0.01) increase in substantiated investigations, and 1 percentage-point increase in the prior-year foreclosure rate was associated with 7.3 % increase in substantiations (p = 0.01).

Discussion

During a period in which substantiated maltreatment reports were generally declining across the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, this study revealed that county-level unemployment rates and mortgage foreclosure rates remained positively associated with the number of investigated and substantiated reports of maltreatment. These findings are consistent with literature indicating significant positive associations of unemployment [15, 29–31] and foreclosure [20] rates with incidence of child abuse and neglect.

It could be surmised that the observed relationship of economic indicators to maltreatment reports might be related to an increase in poverty-related neglect reports that were later unsubstantiated due to failure to indicate bodily harm. This study, however, includes reports of non-accidental physical injury, sexual abuse, or serious neglect only. Cases of chronic truancy, neglect, and poor parental supervision are excluded. Hence, the trends in child abuse investigations presented are not explained simply by the increased poverty-related neglect expected during this period of extremely high unemployment [15]. To envision a pathway by which economic stress and poverty would lead to increase in investigated spurious reports of inflicted injury, intentional neglect, or sexual abuse may be difficult. Therefore, it is plausible that the rise in investigated child abuse reports observed in Pennsylvania in 2009 may indicate increasing incidence of child abuse within the Commonwealth.

Despite the increase in investigated reports, our analysis indicates steady decline in child abuse substantiations over the last two decades, mirroring national data over the interval [18, 32, 33]. Closer examination of the Pennsylvania trend revealed that the proportion of investigations that were substantiated declined over time, so that increasing numbers of cases of reported child maltreatment were not substantiated after investigation. In fact, substantiations were at their lowest levels during the recent recession, despite child maltreatment investigations peaking during the same period. Recent changes in practice in some localities intended to focus CPS efforts on children with present or impending safety risks and to divert other lower risk cases to alternative less intrusive services, as well to reduce the number of children in foster care and residential facilities, may have contributed to the downward trend of CPS substantiations in Pennsylvania in the face of escalation in investigations. States are not formally required to measure or report on repeat contacts for children who are diverted to alternative service responses. As thresholds for substantiation of child abuse cases in child welfare systems evolve, it remains unknown if the growing gap between investigated reports and substantiated cases has placed some children at risk.

Our study has several important limitations. Due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, we cannot infer causality. Unemployment rates, foreclosure rates, and maltreatment cases may have increased simultaneously for unrelated reasons, and the reasons for observed increases in child abuse reports may have varied over time. We selected unemployment as a primary independent variable for our analysis because its relationship to other poor health outcomes has been examined more extensively than any other economic indicator. Unemployment statistics, however, do not include underemployed or discouraged workers who stop looking for a job and may not accurately measure economic hardship due to job loss [21]. Furthermore, because this study was focused on economic analysis, we did not consider other important factors that may influence community-level dynamics of child maltreatment, including cultural, religious or other social structural factors. Finally, the CPS administrative data employed for analysis may not fully capture the actual level of child maltreatment incidence [34]. In particular, not all events of maltreatment reports are ever reported, investigated or subsequently substantiated [35, 36]. Moreover, investigation rates may vary over time and among counties due to modifications of CPS protocol and, possibly, fiscal constraints on professional sources of maltreatment reports and investigating agencies [37].

Despite these limitations, our results hold important implications for future research. Although significant work has been devoted to macro-level factors associated with rates of maltreatment, we posit that it is equally important to understand individual-level factors that influence observed trends in investigated and substantiated maltreatment and to study how the effects of these factors may vary with personal and familial demographics. More importantly, these findings underscore the urgent need to direct child maltreatment prevention efforts, support and resources to communities in periods of economic hardship.

Conclusion

We observe a dramatic decline in the proportion of investigated cases of child maltreatment that are substantiated over the past two decades in Pennsylvania. This temporal trend partially masks a strong association between volume of investigated and substantiated cases of child abuse and measures of economic stress. This relationship suggests that during recent periods of economic stress, there has been an inevitable tension between ensuring child safety and implementing child welfare practice changes. Whether some children may have been placed at increased safety risk in this dynamic environment remains an open question for which there is little empiric data. At the least, these results also highlight the difficulty in utilizing rates of substantiated rates of child maltreatment to accurately capture trends in child maltreatment and safety and the need for more robust and consistent measures of child maltreatment incidence that are not dependent on changes in CPS practices and protocols.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Joanne Wood’s institution has received payment for expert witness court testimony that Dr. Wood has provided in cases of suspected child abuse when subpoenaed to testify. Dr. Wood has received salary funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant: 1K23HD071967-01).

Abbreviations

- AHT

Abusive head trauma

- CPS

Child protective services

- NCANDS

National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System

Contributor Information

Sarah Frioux, Tripler Army Medical Center, Honolulu, HI, USA.

Joanne N. Wood, PolicyLab, Division of General Pediatrics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; Department of Pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Oludolapo Fakeye, PolicyLab, Division of General Pediatrics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

Xianqun Luan, PolicyLab, Division of General Pediatrics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

Russell Localio, PolicyLab, Division of General Pediatrics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

David M. Rubin, PolicyLab, Division of General Pediatrics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; Department of Pediatrics, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

References

- 1.US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013. http://www.nber.org/cycles.html#announcements. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garr E. The landscape of recession: Unemployment and safety net services across Urban and Surburban America. The Brookings Institution; 2011. http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2011/3/31%20recession%20garr/0331_recession_garr.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bocian D, Li W, Reid C. Lost Ground, 2011: Disparities in mortgage lending and foreclosures. Center for Responsible Lending; 2011. http://www.responsiblelending.org/mort gage-lending/research-analysis/Lost-Ground-2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger LM. Income, family structure, and child mal-treatment risk. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26(8):725–748. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancian M, Slack KS, Yang MY. The effect of family income on risk of child maltreatment. Institute for Research on Poverty; 2010. http://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/dps/pdfs/dp138510.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mersky JP, Berger LM, Reynolds AJ, Gromoske AN. Risk factors for child and adolescent maltreatment: a longitudinal investigation of a cohort of inner-city youth. Child Maltreatment. 2009;14(1):73–88. doi: 10.1177/1077559508318399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sedlak AJ, Broadhurst DD. Third national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS-3) National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect; 1996. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/statsinfo/nis3.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Greene A, Li S. Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS-4): Report to congress. National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect; 2010. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/nis4_report_congress_full_pdf_jan2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelles RJ. Poverty and violence toward children. American Behavioral Scientist. 1992;35(3):258. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuravin SJ. Residential density and urban child mal-treatment: An aggregate analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1986;1(4):307–322. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young G, Gately T. Neighborhood impoverishment and child maltreatment: An analysis from the ecological perspective. Journal of Family Issues. 1988;9(2):240–254. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deccio G, Horner WC, Wilson D. High-risk neighborhoods and high-risk families: Replication research related to the human ecology of child maltreatment. Journal of Social Service Research. 1994;18(3–4):123–137. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coulton CJ, Korbin JE, Su M, Chow J. Community level factors and child maltreatment rates. Child Development. 1995;66(5):1262–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drake B, Pandey S. Understanding the relationship between neighborhood poverty and specific types of child mal-treatment. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1996;20(11):1003–1018. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillham B, Tanner G, Cheyne B, Freeman I, Rooney M, Lambie A. Unemployment rates, single parent density, and indices of child poverty: Their relationship to different categories of child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1998;22(2):79–90. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coulton CJ, Korbin JE, Su M. Neighborhoods and child maltreatment: A multi-level study. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1999;23(11):1019–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freisthler B, Bruce E, Needell B. Understanding the geospatial relationship of neighborhood characteristics and rates of maltreatment for black, Hispanic, and white children. Social Work. 2007;52(1):7–16. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R, Hamby SL. Trends in childhood violence and abuse exposure: Evidence from 2 national surveys. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164(3):238–242. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finkelhor D, Jones L, Shattuck A. Updated trends in child maltreatment. Crimes Against Children Research Center. 20102011 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood JN, Medina SP, Feudtner C, Luan X, Localio R, Fieldston ES, et al. Local macroeconomic trends and hospital admissions for child abuse, 2000–2009. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):e358–e364. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berger RP, Fromkin JB, Stutz H, Makoroff K, Scribano PV, Feldman K, et al. Abusive head trauma during a time of increased unemployment: A multicenter analysis. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):637–643. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millett L, Lanier P, Drake B. Are economic trends associated with child maltreatment? Preliminary results from the recent recession using state level data. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(7):1280–1287. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krugman RD, Lenherr M, Betz L, Fryer GE. The relationship between unemployment and physical abuse of children. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1986;10(3):415–418. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(86)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinberg LD, Catalano R, Dooley D. Economic antecedents of child abuse and neglect. Child Development. 1981;52(3):975–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pare J. Unemployment and child abuse in a rural community: A diverse relationship. In 8th National symposium on child victimization; Washington, DC. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang MI, O’Riordan MA, Fitzenrider E, McDavid L, Cohen AR, Robinson S. Increased incidence of nonaccidental head trauma in infants associated with the economic recession. Journal of Neurosurgery Pediatrics. 2011;8(2):171–176. doi: 10.3171/2011.5.PEDS1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Local area unemployment statistics database. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2010. http://www.bls.gov/lau/#data. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kan J. Sources of foreclosure data. Mortgage Bankers Association; 2008. http://www.mortgagebankers.org/files/Research/July2008SourcesofForeclosureData.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slack KS, Holl JL, McDaniel M, Yoo J, Bolger K. Understanding the risks of child neglect: an exploration of poverty and parenting characteristics. Child Maltreatment. 2004;9(4):395–408. doi: 10.1177/1077559504269193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freisthler B. A spatial analysis of social disorganization, alcohol access, and rates of child maltreatment in neighborhoods. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26(9):803–819. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnan V, Morrison KB. An ecological model of child maltreatment in a Canadian province. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1995;19(1):101–113. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)00101-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leventhal JM, Larson IA, Abdoo D, Singaracharlu S, Takizawa C, Miller C, et al. Are abusive fractures in young children becoming less common? Changes over 24 years. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2007;31(3):311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almeida J, Cohen AP, Subramanian SV, Molnar BE. Are increased worker caseloads in state child protective service agencies a potential explanation for the decline in child sexual abuse? A multilevel analysis. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2008;32(3):367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fallon B, Trocmé N, Fluke J, MacLaurin B, Tonmyr L, Yuan YY. Methodological challenges in measuring child maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2010;34(1):70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunn VL, Hickson GB, Cooper WO. Factors affecting pediatricians’ reporting of suspected child maltreatment. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2005;5(2):96–101. doi: 10.1367/A04-094R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flaherty EG, Sege RD, Griffith J, Price LL, Wasserman R, Slora E, et al. From suspicion of physical child abuse to reporting: Primary care clinician decision-making. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):611–619. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephens-Davidowitz S. Essays Using Google Data. Harvard University; 2013. Unreported victims of an economic downturn; pp. 64–95. http://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/10984881/Ste phensDavidowitz_gsas.harvard_0084L_11016.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]