Abstract

Catastrophizing about pain is related to elevated pain severity and poor adjustment among chronic pain patients, but few physiological mechanisms by which pain catastrophizing maintains and exacerbates pain have been explored. We hypothesized that resting levels of lower paraspinal muscle tension and/or lower paraspinal and cardiovascular reactivity to emotional arousal may: (a) mediate links between pain catastrophizing and chronic pain intensity; (b) moderate these links such that only patients described by certain combinations of pain catastrophizing and physiological indexes would report pronounced chronic pain. Chronic low back pain patients (N = 97) participated in anger recall and sadness recall interviews while lower paraspinal and trapezius EMG and systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and heart rate (HR) were recorded. Mediation models were not supported. However, pain catastrophizing significantly interacted with resting lower paraspinal muscle tension to predict pain severity such that high catastrophizers with high resting lower paraspinal tension reported the greatest pain. Pain catastrophizing also interacted with SBP, DBP and HR reactivity to affect pain such that high catastrophizers who showed low cardiovascular reactivity to the interviews reported the greatest pain. Results support a multi-variable profile approach to identifying pain catastrophizers at greatest risk for pain severity by virtue of resting muscle tension and cardiovascular stress function.

Keywords: Pain catastrophizing, Chronic pain severity, Lower paraspinal muscle tension, Cardiovascular reactivity, Profile approach

Catastrophizing about pain is linked to elevated pain severity and poor adjustment among chronic pain patients (Sullivan et al. 1995). It is defined as a tendency to rumi-nate, magnify and feel helpless about pain (Sullivan et al. 1995), and as a negative automatic appraisal of painful stimuli rooted in activation of maladaptive beliefs or pain schemas (Michael and Burns 2004; Spanos et al. 1979; Sullivan et al. 2001). Irrespective of theoretical conceptualization, only a few physiological mechanisms by which pain catastrophizing maintains and exacerbates chronic pain intensity have been explored (e.g., Edwards and Fillingim 2005).

Physical and psychological stress may lead to frequent and intense, or low level but sustained muscular contractions (Sjegaard et al. 2000). This muscle activity can increase pain through ischemia and hypoxia (Fields 1987), and through changes in mechanoreceptor sensitivity (Mense 1993). Flor and colleagues (Flor et al. 1985, 1991, 1992) proposed a “symptom-specificity” model of chronic pain, which proposes that patients with certain kinds of musculoskeletal disorders can be distinguished from patients with other kinds of musculoskeletal disorders by substantial stress-induced tension in muscles near the site of pain or injury. Thus, chronic low back pain patients can be expected to show aberrant stress-induced muscular responses specific to the disorder; that is, exaggerated contraction of muscles in the low back (i.e., lower paraspinals). Findings support symptom-specificity models among low back pain patients (Arena et al. 1991; Burns 2006a; Flor et al. 1991, 1992) and those with neck and shoulder pain (Lundberg et al. 1994, 1999), and suggest that frequent or sustained stress-induced tension of muscles specific to a disorder may maintain and aggravate existing chronic pain.

Burns and colleagues (Burns 2006a; Burns et al. 1997) found that lower paraspinal reactivity to psychological stress was related to reports of day-to-day chronic pain severity among chronic low back pain patients, whereas trapezius tension (muscles distal from the source of pain) was not. Lundberg (1994, 1999) found that people with trapezius myalgia and substantial neck/shoulder pain evinced higher levels of trapezius muscle tension during work than people without. To the extent that pain catastrophizers are vulnerable to anxiety, anger and so forth (Hirsh et al. 2007), such symptom-specific muscle tension reactivity may link pain catastrophizing to chronic pain intensity. For low back pain patients, pain catastrophizing may be related to chronic pain severity through heightened tension in lower paraspinal muscles during negative emotions, as opposed to reactivity in muscles distant from pain (e.g., trapezius). Thus, pain catastrophizing may lead to relatively high levels of emotion-induced lower paraspinal reactivity, which in turn affects chronic pain severity. Findings also indicate that pain catastrophizers are characterized by a propensity to direct attention to the most negative affectively charged elements of pain (Michael and Burns 2004). Increased vigilance for any sign of a potentially overwhelming and tragic event—pain—may underlie high levels of resting muscle tension; a factor also linked to pain aggravation (Burns 2006b). Thus, for chronic low back pain patients, catastrophizing about pain may affect chronic pain severity to the extent that catastrophizing leads to amplified lower paraspinal muscle tension even at rest.

In addition to lower paraspinal muscle tension acting as a mediator between pain catastrophizing and chronic pain, it may also moderate these relationships. Rather than considering pain catastrophizing and muscle tension separately (as in main effect models) or in tandem (as in mediator models), factors exacerbating chronic pain severity may best be determined through a multi-variable profile approach. Thus, for instance, the relationship between pain catastrophizing and pain severity may further depend on whether a chronic low back pain patient exhibits high levels of resting lower paraspinal muscle tension and/ or high levels of lower paraspinal reactivity during emotional arousal. Results support this kind of multi-variable approach. Burns et al. (1997) found that the significant but modest main effect between depressed mood and chronic pain severity was moderated by stress-induced lower paraspinal reactivity, such that the highest chronic pain was reported by chronic low back pain patients with high levels of depressed mood and who showed high levels of lower paraspinal reactivity. Patients with high depressed mood but who were not strong lower paraspinal muscle reactors reported pain comparable to patients with low depressed mood. Consistent with these findings, it may be the case that patients exhibiting a certain profile of risk factors—namely, high pain catastrophizing and high levels of resting lower paraspinal tension and/or high levels of lower paraspinal reactivity—may be at greatest risk for high pain severity.

Other physiological mechanisms also need to be considered as potential mediators or moderators of relations between catastrophizing and chronic pain severity. For example, pain catastrophizing is associated with elevated negative affect (Hirsh et al. 2007), which in turn is often associated with heightened cardiovascular stress reactivity (Burns 1995; Feldman et al. 1999; Kamarck et al. 1998; Prkachin et al. 1999). Prior work indicates that elevations in systolic blood pressure trigger endogenous analgesic mechanisms through functional links between the cardiovascular and pain regulatory systems (e.g., Bruehl and Chung 2004; Edwards et al. 2001, 2003; Ghione 1996; Rau and Elbert 2001). In this context, a mediation model would predict that catastrophizing would be associated with lower pain intensity through activation of blood pressure-related analgesia. This mediation model appears unlikely given that pain catastrophizing is typically associated with greater pain severity (Sullivan et al. 2001). Instead, a moderation model may apply. Pain catastrophizing may be linked to elevated pain intensity most strongly in concert with another risk factor for exaggerated pain responsiveness; namely, inadequate triggering of blood pressure-related endogenous analgesic systems resulting from low blood pressure reactivity. That is, people characterized both by the tendency to make catastrophic appraisals of painful stimuli and who exhibit low stress-induced blood pressure reactivity (therefore triggering little blood pressure-related analgesia) may experience greater pain than catastrophizers who exhibit high stress-induced blood pressure reactivity (and greater blood pressure-related analgesia)—as well as people who are not prone to catastrophize.

For this study, additional analyses of data presented in Burns (2006b) were performed. In Burns (2006b), chronic low back pain patients participated in anger- and sadness-recall interviews while lower paraspinal and trapezius EMG, and systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and heart rate (HR) were recorded. Here, we tested mediation and moderation models by which pain catastrophizing may be related to pain severity among chronic low back pain patients. If pain catastrophizing is related to chronic pain severity through the tendencies to exhibit high resting levels of lower paraspinal muscle tension, or to show high levels of lower paraspinal reactivity during emotional arousal, then these factors should substantially account for the association between the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (Sullivan et al. 1995) scores and a scale assessing everyday chronic pain severity. Moreover, resting muscle tension and/or muscle tension and blood pressure reactivity during emotional arousal may moderate links between pain catastrophizing and chronic pain severity. If so, then high pain catastrophizers who exhibit high levels of resting lower paraspinal muscle tension and/ or show high levels of lower paraspinal reactivity should report higher chronic pain severity than high catastrophizers who exhibit low lower paraspinal resting levels and/or reactivity. Finally, high pain catastrophizers who exhibit lower blood pressure reactivity should report higher chronic pain severity than high catastrophizers who exhibit higher blood pressure reactivity.

Finally, we considered the possibility that pain catastrophizing, which overlaps empirically and conceptually with depressed mood (Sullivan and D'Eon 1990), was serving only as a proxy for depression. To examine whether pain catastrophizing functioned as a unique factor in mediation and moderation models, all significant analyses were conducted again with Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al. 1961) scores statistically controlled.

Method

Participants

Participants were 97 chronic low back pain patients recruited through advertisements and postings at pain clinics. They were paid $40. Exclusion criteria were: (a) any current cardiovascular disorder; (b) current use of medications that affect cardiovascular function (i.e., beta blockers); (c) chronic pain stemming from malignant conditions (i.e., cancer); (d) current alcohol or substance abuse problems; (e) a history of psychotic or bipolar disorders; (f) daily use of narcotic analgesic medication; and (g) inability to understand and speak English well enough to participate in the anger and sadness recall interviews. Inclusion criteria were: (a) musculoskeletal pain of the lower back stemming from degenerative processes, muscular or ligamentous strain, or disc herniation as determined by a neurosurgeon or neurologist; and (b) pain duration of at least 6 months.

For patients who reported using opioid-based analgesics, they were asked not to take these medications on the morning of their appointments. Physiological data from three participants were lost due to equipment failure, and so the final sample was 94 patients. Women comprised 53.2% (n = 50) of the sample. Descriptive information appears in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 94)

| Variables | Statistics |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | % | n | |

| Age (years) | 46.2 | 14.5 | ||

| At least 12-years of education | 90.4 | 85 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 66.0 | 62 | ||

| Hispanic | 4.3 | 4 | ||

| African American | 27.7 | 26 | ||

| Asian | 1.0 | 1 | ||

| Pain duration (mos) | 48.6 | 45.4 | ||

| Opioid-based medication | 22.3 | 21 | ||

| Nonsteroidal | 56.4 | 53 | ||

| Anti-inflammatory | ||||

| Muscle relaxants | 9.6 | 9 | ||

| Antidepressants | 7.4 | 7 | ||

Design overview

The original study (Burns 2006b) used a within-subjects design in which participants underwent both anger- and sadness-recall interviews (see below), with interview order counterbalanced. Trapezius and lower paraspinal muscle tension, and SBP, DBP and HR were assessed during baselines and interviews.

Measures

Recording EMG

EMG activity was recorded from left and right lower paraspinals (L2–L4), and left and right trapezius muscles. Silver/silver chloride 8 mm electrodes were spaced 15 mm apart for bipolar recording, as recommended by Fridlund and Cacioppo (1986). Sites were prepared with vigorous alcohol abrasion. Inter-electrode impedance was kept below 10 kiloohms. Isolated bioamplifiers with bandpass filters (Coulbourn Instruments) were used to record EMG. Raw EMG signals were amplified by a factor of 100,000. The sampling rate was 10/s, and signals were passed through narrow bandpass filters (100–250 Hz). A narrow bandpass was used to increase the specificity of signals from target muscles. Signals were integrated and “smoothed” with contour-following and cumulative integrators (Coulbourn Instruments). Following recommendations by Fridlund and Cacioppo (1986), the time constant for integration was 100 ms. Data were collected by a dedicated computer through analog/digital conversion using Wingraph software.

Recording cardiovascular indexes

Systolic blood pressure (SBP), DBP and HR were measured with a Dinamap 1846 SX Monitor (Johnson and Johnson Medical Inc.). This instrument assesses blood pressure with the oscillometric technique. Readings were obtained about every 60-s during baselines and interviews. Data were collected by a dedicated computer through analog/digital conversion using Wingraph software.

Pain catastrophizing

Patients completed the 13-item Pain Catastrophizing Scale (Sullivan et al. 1995). Items tap three core dimensions of pain catastrophizing: rumination (e.g., “I keep thinking about how badly I want the pain to stop”), helplessness (e.g., “I feel I can't go on”), and magnification (e.g., “I wonder whether something serious may happen. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale possesses strong reliability and validity (Sullivan et al. 1995).

Depressed mood

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al. 1961) was used to tap patient depressed mood. The BDI is a widely used, psychometrically sound instrument for the assessment of current depressive symptoms. We used BDI scores to assess whether degree of depressed mood accounted for links between pain catastrophizing and pain severity.

Chronic pain severity

Patients also completed the Pain Severity scale of the Multidimensional Pain Inventory (Kerns et al. 1985) to give ratings of everyday chronic pain severity.

Emotion-induction interviews

Participants engaged in 5-min semi-structured interviews during which they described recent events that had elicited anger or sadness. The Anger Recall Interview and the Sadness Recall Interview were intended to evoke the target emotions. The procedure was adapted from Dimsdale et al. (1988). The anger and sadness recall procedures elicit significant muscle tension, SBP, DBP and HR reactivity (Burns et al. 1997; Burns 2006b). Moreover, findings tell that both anger and sadness recall interviews elicit self-reported valence and arousal in expected directions (Burns et al. 2003; Neumann and Waldstein 2001).

Details of the procedures can be found in Burns (2006b). In brief, the experimenter asked a participant to recall a recent event in their life during which they experienced the relevant emotion. The participant was told to describe the event in detail, and to focus on angry or sad thoughts and feelings. The experimenter used requests for clarification, probes, and reflections to encourage the participant to focus on the most emotionally arousing aspects of the event. The experimenter was never hostile, avoided badgering, and did not raise questions that might implicate participant's character in contributing to his or her misfortune.

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two interview orders: anger recall/sadness recall or sadness recall/ anger recall. Upon arriving at the laboratory, the participant signed an informed consent form, was seated upright in a comfortable chair, and the electrodes and blood pressure cuff were attached. A 10-min baseline followed, during which resting EMG, SBP, DBP and HR readings were obtained. Instructions were then given for the first recall interview (either anger or sadness), and the interview commenced. After 5 min, the participant was stopped. Another 10-min resting baseline began, followed by the remaining recall interview (either anger or sadness). After 5 min, the participant was stopped, the electrodes and cuff were removed, and the participant was debriefed.

Data reduction and analyses

Lower paraspinal and trapezius EMG readings from left and right sites were summed and averaged. First and second baseline values for EMG, SBP, DBP and HR values were defined as the mean of readings taken during the last 3 min of each 10-min baseline, and values from these two baseline periods were summed and averaged to provide single indexes of lower paraspinal, trapezius, SBP, DBP and HR baseline levels. Anger Recall Interview and Sadness Recall Interview values were defined as the mean of readings taken during the 5-min interviews. We do not offer hypotheses regarding effects of pain catastrophizing on chronic pain through arousal of anger specifically as opposed to arousal of sadness specifically. Instead, we expect that catastrophizing may affect pain through responses to the arousal of negative affect in general. Therefore, values from the two interview periods were summed and averaged to provide single indexes of lower paraspinal, trapezius, SBP, DBP and HR levels during arousal of negative emotions.

Analyses were conducted to insure that interview physiological values (averaged across the anger and sadness recall interviews) increased significantly from baseline. Residualized change scores were then computed by regressing baseline values on respective interview values. Zero-order correlations were computed among these change scores, baseline values, Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores and Pain Severity values to ascertain whether preconditions for testing mediation were met (see Baron and Kenny 1986). Hierarchical regressions would then be conducted to test whether the relationship between Pain Catastrophizing Scale and Pain Severity scores was significantly attenuated by controlling for mediators [e.g., whether the relationship between these scale scores was significantly reduced (according to a Sobel test) with resting levels and/or reactivity scores controlled].

Moderation models were also evaluated with hierarchical regressions. Interaction terms were computed by multiplying Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores by relevant resting and reactivity values. Testing whether resting lower paraspinal levels moderate the link between Pain Castro-phizing Scale and Pain Severity scores will be used to illustrate the procedure. With Pain Severity scores as the dependent variable, the main effect terms were entered in the first step (Pain Catastrophing Scale scores, resting lower paraspinal levels), followed by the interaction term in the second step (Pain Catastrophizing Scale × resting lower paraspinal levels). A significant increment in R2 for the interaction term denoted a significant interaction. To depict a significant interaction, regression equations were solved for hypothetical Pain Catastrophizing Scale values (±1 SD from the mean), and hypothetical physiological variable values (±1 SD from the mean), and the resulting predicted Pain Severity values were then graphed (see Aiken and West 1991).

Results

Changes from baseline to interview

Results of within-subject ANOVAs showed that lower paraspinal, trapezius, SBP, DBP and HR values increased significantly from (composite) baseline [averaged across first and second baselines (see above)] to (composite) interview [averaged across the ARI and SRI (see above)] [F's(1.93) > 32.0; P's < .01; η2 `s > .256]. Values are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means (SDs) of EMG and cardiovascular values during combined anger recall and sadness recall interviews

| Variable and status | Period |

|

|---|---|---|

| BL | Interviews | |

| Lower paraspinal values (microvolts) | 3.97 (2.5) | 4.96 (2.8) |

| Trapezius values (microvolts) | 3.81 (2.9) | 4.12 (3.0) |

| SBP values (mm/Hg) | 115.56 (16.0) | 128.04 (19.5) |

| DBP values (mm/Hg) | 73.14 (9.7) | 82.27 (9.7) |

| HR values (bpm) | 68.90 (11.4) | 75.46 (11.7) |

Note: BL = mean of baseline values preceding the two interviews; Interviews = mean of Anger Recall and Sadness Recall Interview values

Zero-order correlations

Residualized change scores were computed by regressing baseline values on interview values. Zero-order correlations were then computed among all variables. Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores were correlated significantly with Pain Severity scores (r = .39; P < .01), as were BDI scores (r = .25; P < .02). However, neither Pain Catastrophizing Scale nor Pain Severity scores were correlated significantly with any physiological variable resting value (r's < .19; P's > .08). Pain Severity scores were correlated negatively and significantly with residualized change scores (i.e., baseline-corrected reactivity) for SBP (r = –.23; P < .05) and DBP (r = –.23; P < .05), but not with lower paraspinal or trapezius muscle tension residualized change scores (r's < .13; P's > .10). Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores were not correlated significantly with the blood pressure change scores (r's < .06; P's > .10), or with the muscle tension change scores (r's < .14; P's > .10). Thus, preconditions for further tests of mediation were unmet.

Tests of moderation

Pain catastrophizing scale scores × resting muscle tension levels

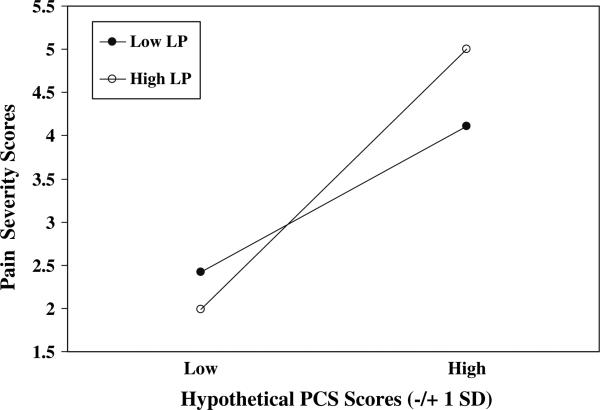

A series of hierarchical regressions were performed to determine whether the link between Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores and Pain Severity scores was moderated by resting levels of muscle tension. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale · lower paraspinal (resting levels) interaction was significant (P < .05; see Table 3). Regression equations were then solved for four combinations of Pain Catastrophizing Scale (±1 SD) and lower paraspinal (±1 SD) values. Predicted Pain Severity values for these hypothetical scores are depicted in Fig. 1. Results underscore the positive association between Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores and Pain Severity scores, but also suggest that patients with high pain catastrophizing (approximately 1 SD above the mean and greater) who also exhibit high resting levels of lower paraspinal muscle tension (approximately 1 SD above the mean and greater) reported the highest chronic pain severity of all patients.

Table 3.

Summary of hierarchical regressions

| Variable and measure | B | SEB | R2 | Change in R2 of step | P-value for R2 change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain severity | |||||

| Step 1: | |||||

| PCS | .63 | .16 | |||

| LP (resting) | –.01 | .06 | .151 | .151 | <.001 |

| Step 2: | |||||

| PCS × LP (resting) | .16 | .07 | .198 | .047 | <.03 |

| Pain severity | |||||

| Step 1: | |||||

| PCS | .57 | .16 | |||

| SBP Δ | –.23 | .15 | .174 | .174 | <.001 |

| Step 2: | |||||

| PCS × SBP Δ | –.516 | .16 | .271 | .097 | <.001 |

| Pain severity | |||||

| Step 1: | |||||

| PCS | .39 | .12 | |||

| DBP Δ | –.27 | .13 | .163 | .163 | <.001 |

| Step 2: | |||||

| PCS × DBP Δ | –.286 | .15 | .200 | .038 | <.05 |

| Pain severity | |||||

| Step 1: | |||||

| PCS | .64 | .16 | |||

| HR Δ | –.28 | .19 | .173 | .173 | <.001 |

| Step 2: | |||||

| PCS × HR Δ | –.561 | .21 | .239 | .066 | <.01 |

Note. PCS = Pain Catastrophizing Scale; LP (resting) = mean of lower paraspinal baseline values preceding Anger Recall and Sadness Recall Interviews; SBP Δ = residualized change score for SBP values; DBP Δ = residualized change score for DBP values; HR Δ = residualized change score for HR values

Fig. 1.

PCS scores × Lower Paraspinal (resting) Values. PCS = Pain Catastrophizing Scale; Hypothetical PCS scores = ±1 SD from mean; Low LP = Low (–1 SD from mean) lower paraspinal values at resting baseline; High LP = High (+1 SD from mean) lower paraspinal values at resting baseline

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale × Trapezius (resting levels) interaction did not significantly predict Pain Severity scores. Taken together, results suggest that the inclination to catastrophize about pain predicted chronic pain severity in concert with resting muscle tension levels near the site of pain or injury (i.e., lower paraspinal muscles among these chronic low back pain patients), whereas resting tension of muscles distal from the site did not.

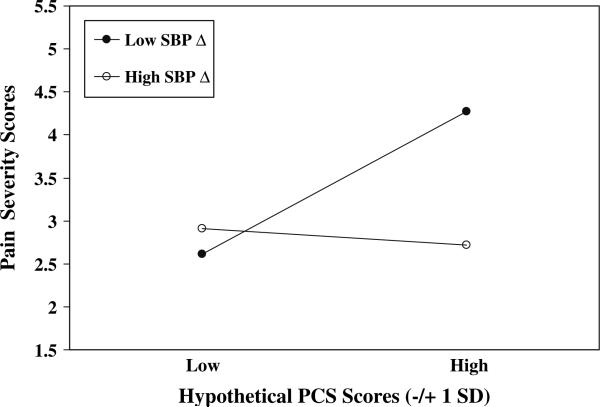

Pain catastrophizing scale scores × residualized change scores

A series of hierarchical regressions were performed to determine whether the link between Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores and Pain Severity scores was moderated by muscle tension, blood pressure or HR reactivity (residualized change scores). The Pain Catastrophizing Scale × SBP Reactivity interaction was significant (P < .01; see Table 3). Regression equations were then solved for four combinations of Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores (±1 SD) and SBP reactivity scores (±1 SD). Predicted Pain Severity values for these hypothetical scores are depicted in Fig. 2. Results suggest that the positive association between Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores and Pain Severity scores applies most strongly to patients who also exhibit low SBP reactivity, such that patients with high pain catastrophizing (approximately 1 SD above the mean and greater) and low SBP reactivity (approximately 1 SD below the mean and less) reported the highest chronic pain severity of all patients.

Fig. 2.

PCS scores × SBP Reactivity. PCS = Pain Catastrophizing Scale; Hypothetical PCS scores = ±1 SD from mean; Low SBP Δ = Low (–1 SD from mean) SBP residualized change scores; High SBP Δ = High (+1 SD from mean) SBP residualized change scores

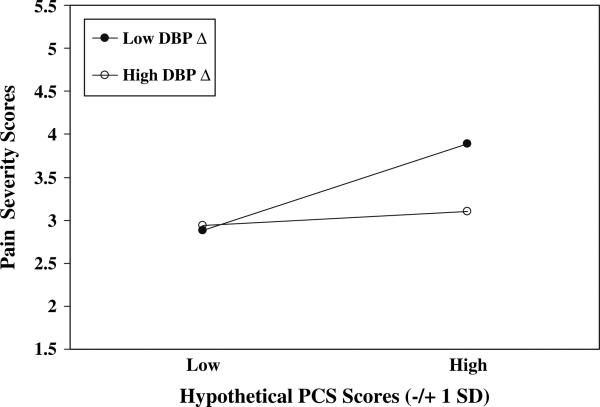

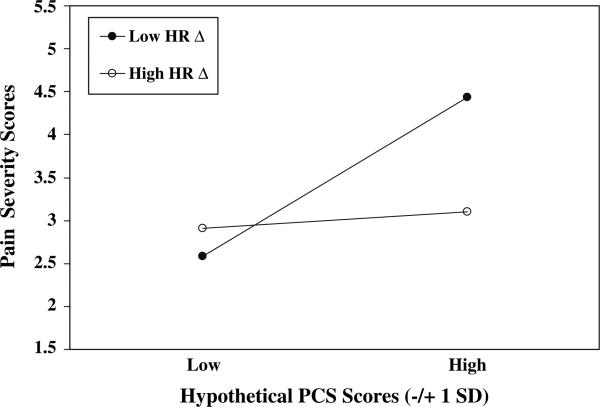

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale × DBP Reactivity and Pain Catastrophizing Scale × HR Reactivity interactions were also significant (P's < .05; see Table 3). The procedure described above was used to illustrate these interactive effects. Results parallel those for SBP reactivity (see Figs. 3 and 4) in that patients with high pain catastrophizing (approximately 1 SD above the mean and greater) and low DBP reactivity or low HR reactivity (approximately 1 SD below the respective means and less) appeared to report the highest chronic pain severity of all patients.

Fig. 3.

PCS scores × DBP Reactivity. PCS = Pain Catastrophizing Scale; Hypothetical PCS scores = ±1 SD from mean; Low DBP Δ = Low (–1 SD from mean) DBP residualized change scores; High DBP Δ = High (+1 SD from mean) DBP residualized change scores

Fig. 4.

PCS scores × HR Reactivity. PCS = Pain Catastrophizing Scale; Hypothetical PCS scores = ±1 SD from mean; Low HR Δ = Low (–1 SD from mean) HR residualized change scores; High HR ΔD = High (+ 1 SD from mean) HR residualized change scores

Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores did not interact significantly with lower paraspinal and trapezius reactivity scores to predict Pain Severity scores.

Results and inspection of predicted Pain Severity values in Figs. 2–4 imply that the highest chronic pain severity was reported by patients who were characterized by both high pain catastrophizing and low blood pressure and HR reactivity during arousal of negative emotions. Indeed, high catatrophizers who exhibited high blood pressure and HR reactivity reported levels of pain approximately equivalent to those reported by low catastrophizing patients.

Controlling for depressed mood

The hierarchical regressions testing Pain Catastrophizing Scale × lower paraspinal (resting levels), Pain Catastrophizing Scale × SBP reactivity, Pain Catastrophizing Scale × DBP reactivity and Pain Catastrophizing Scale × HR reactivity interaction effects were rerun with BDI scores entered in the first step. Although BDI scores were related significantly to Pain Severity scores, results were not altered appreciably by controlling for depressed mood.

Discussion

Pain catastrophizing is reliably related to chronic pain severity and poor psychosocial adjustment. However, few physiological mechanisms by which such catastrophic appraisals actually influence pain have been explored. Here, we proposed that symptom-specific lower paraspinal muscle tension reactivity to negative emotional arousal, as well as resting levels of lower paraspinal muscle tension, may mediate links between pain catastrophizing and chronic pain severity. In addition, we evaluated multivariable profile (i.e., moderator) approaches in which risk factors (i.e., low blood pressure reactivity) for pain intensity were examined in combination to identify particularly problematic “groups” of patients. Although hypotheses for mediation models were not supported, several significant moderation effects emerged, supporting the broad notion that the link between pain catastrophizing and chronic pain severity depends on certain physiological parameters.

Plausible pathways by which pain catastrophizing may aggravate chronic pain are through symptom-specific resting muscle tension and/or reactivity levels. For chronic low back pain patients, high levels of resting lower paraspinal muscle tension or large increases in lower paraspinal tension during emotional arousal appear to impact chronic pain severity (Burns et al. 2003; Burns 2006b). However, Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores were not correlated significantly with resting muscle tension or with reactivity, and so further tests of mediation were inappropriate. Thus, pain catastrophizing did not appear to influence chronic pain severity through the mechanism of symptom-specific lower paraspinal muscle tension at rest or in response to emotional arousal.

Instead, we found that Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores interacted with resting lower paraspinal levels to predict chronic pain severity. Although pain catastrophizing was related significantly to pain severity as a main effect, inspection of predicted chronic pain severity values in Fig. 1 suggested that this relationship was magnified among patients who also exhibited high levels of lower paraspinal muscle tension. Overall, patients high in catastrophizing tended to report greater pain than patients with low catastrophizing, but high catastrophizers who also showed high resting lower paraspinal tension appeared to report even greater pain than high catastrophizers displaying low resting tension. Judging from the R2 increment for the interaction term, this effect was no more than modest. Still, results suggest that considering both pain catastrophizing and a symptom-specific physiological parameter jointly may predict chronic pain severity levels to a greater extent than taking each factor into account separately. Here, we identified a subset of chronic low back pain patients who tend to be on guard for potentially overwhelming bouts with pain, who interpret actual painful stimuli as awful and unbearable, but who also may brace or affect postural changes to protect the affected area, thus increasing resting lower paraspinal muscle tension. Moreover, findings support a symptom-specific moderator model in that the link between pain catastrophizing and pain severity among chronic low back pain patients did not further depend on resting tension of trapezius muscles, that is, on muscles at a site distant from the pain or injury.

Functional interactions between the cardiovascular and pain regulatory systems may represent another pathway by which pain catastrophizing affects chronic pain severity. In this case, a mediation model did not seem plausible because we expected the link between emotion-induced blood pressure reactivity and chronic pain severity to be negative—as we did indeed find—and the link between Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores and blood pressure reactivity to be positive Bruehl which was the case (although effects were nonsignificant). Instead, a moderation model allowed examination of pain severity levels among “groups” of patients described by profiles of varying levels of two risk factors for heightened pain: catastrophizing about pain and blood pressure reactivity. We found that low blood pressure and low HR reactivity during arousal of negative emotions in the lab in combination with high levels of self-reported pain catastrophizing predicted the highest levels of daily chronic pain severity. The hyperalgesic effects of this profile can be interpreted in light of literature regarding blood pressure-related analgesia. Elevated resting blood pressure is reliably associated with reduced acute pain responsiveness (Bruehl et al. 1992;1994; Ghione 1996), and evidence suggests that transient increases in systolic blood pressure also elicit hypoalgesia (Edwards et al. 2001; 2003). Individuals who are prone to catastrophize about pain who also exhibit low stress-induced cardiovascular reactivity may experience greater daily chronic pain intensity due to automatic negative appraisals of pain stimuli in combination with limited activation of blood pressure-related antinociceptive mechanisms. Thus, the combination of two risk factors for heightened pain severity identified a particularly vulnerable subset of chronic low back pain patients. Similar findings for blood pressure and HR reactivity in this study may reflect the contribution of HR increases to the blood pressure increases that were observed.

Inspection of the patterns of predicted pain severity values depicted in Figs. 2–4 allows for additional speculation about pain catastrophizing, cardiovascular reactivity and pain. Results suggest that the often-reported positive association between pain catastrophizing and chronic pain severity may only be present among patients who also show low emotion-induced cardiovascular reactivity. High pain catastrophizers who also exhibited high cardiovascular reactivity—implying adequate blood pressure-related analgesia—reported low levels of pain severity comparable to the low levels of pain reported by low catastrophizers. Thus, the frequently cited main effect for catastrophizing on pain severity may be somewhat misleading because especially high levels of chronic pain severity may be experienced only by pain catastrophizers characterized by an additional—physiological—risk factor. Alternatively, we can say that the main effects for SBP and DBP reactivity on pain severity were also misleading because only among high catastrophizers were the effects strongly negative. Indeed, the other three “groups” appeared to report comparable—and rather low—levels of pain severity. These findings suggest that high blood pressure reactivity may have ameliorated some of the detrimental effects of catastrophic appraisals on pain severity for high catastrophizers, that low catastrophizers appeared not to benefit from also exhibiting high reactivity, and that low catastrophizing may have nullified in some way the hyperalgesic effects of low cardiovascular reactivity. Our moderation effects appear to open a number of intriguing avenues of inquiry, and suggest that considering the interplay of cognitive appraisal and physiological factors may prove quite fruitful in understanding determinants of pain severity. Additional research is surely needed to uncover the processes by which low cardiovascular reactivity may magnify effects on pain severity of making catastrophic appraisals of potential and actual pain.

Some limitations should be delineated. First, although negative emotions were induced in the laboratory, the design of this study was still essentially cross-sectional. All questionnaire measures and pain severity were recorded on the same day as the interview manipulations, and so the effects reported were not derived from a longitudinal design. Our design limits the validity of drawing causal connections. Second, the interpretations of the moderation models given above assume that high resting levels of lower paraspinal tension shown in the lab are comparable to those patients would show in everyday life, and, similarly, that low cardiovascular reactivity to emotional arousal in the lab would similarly be observed in response to naturalistic stressors in the individuals’ daily environment. Third, the interviews were designed to elicit anger and sadness, for purposes described in Burns (2006b), without necessarily focusing on issues related to the chronic pain condition. From a “person × situation” perspective, it perhaps may have been more appropriate to examine links between pain catastrophizing and chronic pain using interviews probing for difficulties adjusting to pain, interference with social and work functioning, issues of loss and so forth. The ability to test whether catastrophizing affects pain through physiological reactivity may have been limited because of the unrestricted topics patients could describe in the interviews.

Finally, although prior work suggests that blood pressure-related analgesia may be impaired in chronic pain patients (Bragdon et al. 2002; Bruehl et al. 2002; Bruehl and Chung 2004), the current findings indicate that some patients do exhibit effective blood pressure-related anal-gesia. These contrasting findings could reflect key methodological differences across these studies. While the current study examined these issues specifically in the context of heightened emotional arousal, prior work suggesting impaired blood pressure-related analgesia in chronic pain patients was conducted in the absence of any specific emotional or arousal manipulation. It is possible that elevated emotional arousal may have activated blood pressure-related analgesia in chronic pain patients that would otherwise have been absent.

Pain catastrophizing is clearly an important psychosocial factor linked to high levels of pain and poor adjustment among people suffering from chronic pain conditions. Uncovering the physiological mechanisms that may translate the tendency to appraise painful episodes as overpowering disasters into increased pain perception and disability will permit greater understanding of what makes catastrophizing so detrimental. Although we focused attention on muscle tension and blood pressure reactivity, other pathways including genetic (George et al. in press) and cortical response factors (Seminowicz and Davis 2006) need be considered in future studies. Our results did not support the existence of mechanistic pathways by which pain catastrophizing leads to increased pain severity through its effects on resting levels of muscle tension and/or muscle tension and cardiovascular reactivity. Instead, moderator models pointed to certain profiles that combined a cognitive appraisal variable with physiological variables to describe individuals at pronounced risk for heightened chronic pain severity. Such multi-variable approaches have advantages over considering risk factors one at a time. Such approaches can help to understand how cognitive and physiological “levels” of explanation interconnect to affect pain, and may also allow numerous opportunities to craft and employ therapeutic techniques informed by awareness that catas trophizing is not the only factor at issue that needs clinical attention, but, for instance, a patient's deficits in baroreflex—mediated analgesia may need to be addressed as well.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by Grants NS37164 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and MH071260 from the National Institute of Mental Health (John W. Burns, Ph.D.), and NS046694 and NS050578 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (Stephen Bruehl, Ph.D. and Ok Y. Chung, M.D., M.B.A.).The authors gratefully acknowledge the generosity, help and cooperation of the staff at the Pain & Rehabilitation Clinic of Chicago, without which this study would not have been possible.

Contributor Information

Brandy Wolff, Department of Psychology, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, 3333 Green Bay Rd, North Chicago IL 60064, USA.

John W. Burns, Department of Psychology, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, 3333 Green Bay Rd, North Chicago IL 60064, USA

Phillip J. Quartana, Department of Psychology, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, 3333 Green Bay Rd, North Chicago IL 60064, USA

Kenneth Lofland, Pain & Rehabilitation Clinic of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Stephen Bruehl, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA.

Ok Y. Chung, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA

References

- Arena JG, Sherman RA, Bruno GM, Young TR. Electromyographic recordings of low back pain subjects and non-pain control is six different positions: Effects of pain levels. Pain. 1991;45:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90160-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragdon EE, Light KC, Costello NL, Sigurdsson A, Bunting S, Bhalang K, Maixner W. Group differences in pain modulation: Pain-free women compared to pain-free men and to women with TMD. Pain. 2002;96:227–237. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00451-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl S, Carlson CR, McCubbin JA. The relationship between pain sensitivity and blood pressure in normotensives. Pain. 1992;48:463–467. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90099-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl S, Chung OY. Interactions between the cardiovascular and pain regulatory systems: An updated review of mechanisms and possible alterations in chronic pain. Neuro-science and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2004;28:395–414. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl S, Chung OY, Ward P, Johnson B, McCubbin JA. The relationship between resting blood pressure and acute pain sensitivity in healthy normotensives and chronic back pain sufferers: The effects of opioid blockade. Pain. 2002;100:191–201. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehl S, McCubbin JA, Wilson JF. Coping styles, opioid blockade, and cardiovascular response to stress. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;17:25–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01856880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW. Interactive effects of traits, states, and gender on cardiovascular reactivity during different situations. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1995;18:279–303. doi: 10.1007/BF01857874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW. The role of attentional strategies in moderating links between acute pain induction and subsequent emotional stress: Evidence for symptom specific reactivity among chronic pain patients versus healthy nonpatients. Emotion. 2006a;6:180–192. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW. Arousal of negative emotions and symptom-specific reactivity in chronic low back pain patients. Emotion. 2006b;6:309–319. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Bruehl S, Quartana PJ. Anger management style and hostility among patients with chronic pain: Effects on symptom-specific physiological reactivity during anger- and sadness-recall interviews. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:786–793. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000238211.89198.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Kubilus A, Bruehl S. Emotion induction moderates effects of anger. Management style on acute pain sensitivity. Pain. 2003;106:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JW, Wiegner S, Derleth M. Linking symptom-specific physiological reactivity to pain severity in chronic low back pain patients: A test of mediation and moderation models. Health Psychology. 1997;16:319–326. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimsdale JE, Stern MJ, Dillon E. The stress interview as a tool for examining physiological reactivity. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1988;50:64–71. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198801000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards L, McIntyre D, Carroll D, Ring C, France CR, Martin U. Effects of artificial and natural baroreceptor stimulation on nociceptive responding and pain. Psychophysiolgy. 2003;40:762–769. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards L, Ring C, McIntyre D, Carroll D. Modulation of the human nociceptive flexion reflex across the cardiac cycle. Psychophysiology. 2001;38:712–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Styles of pain coping predict cardiovascular functioning following a cold pressor test. Pain Research and Management. 2005;10:219–222. doi: 10.1155/2005/216481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman PJ, Cohen S, Lepore SJ, Matthews KA, Kamarck TW, Marsland AL. Negative emotions and acute physiological responses to stress. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1999;21:216–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02884836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL. Pain. Raven; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Flor H, Birbaumer N, Schugens MM, Lutzenberger W. Symptom- specific psychophysiological responses in chronic pain patients. Psychophysiology. 1992;29:452–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1992.tb01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor H, Birbaumer N, Schulte W, Roos R. Stress-related electromyographic responses in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain. Pain. 1991;46:145–152. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90069-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor H, Turk DC, Birbaumer N. Assessment of stress-related psychophysiological reactions in chronic back pain patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:354–364. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridlund AJ, Cacioppo JT. Guidelines for human electromyographic research. Psychophysiology. 1986;23:567–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SZ, Wallace MR, Wright TW, Moser MW, Greenfield WH, 3rd, Sack BK, Herbstman DM, Fillingim RB. Evidence for a biopsychosocial influence on shoulder pain: Pain catastrophizing and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) diplotype predict clinical pain ratings. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.019. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghione S. Hypertension-associated hypalgesia: Evidence in experimental animals and humans, pathophysiological mechanisms, and potential clinical consequences. Hypertension. 1996;28:494–504. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh AT, George SZ, Riley JL. An evaluation of the measurement of pain catastrophizing by the coping strategies questionnaire. European Journal of Pain. 2007;11:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamarck TW, Shiffman SM, Smithline L, Goodie JL, Paty JA, Gnys M, Jong JY. Effects of task strain, social conflict, and emotional activation on ambulatory cardiovascular activity: Daily life consequences of recurring stress in a multiethnic adult sample. Health Psychology. 1998;17:17–29. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns RD, Turk DC, Rudy TE. The west Haven-Yale multidimensional pain inventory (WHYMPI). Pain. 1985;23:345–356. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg U, Dohns IE, Melin B, Sandsjo L, Palmeund G, Kadefors R, Ekstron M, Parr D. Psychophysiological stress responses, muscle tension, and neck and shoulder pain among supermarket cashiers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 1999;4:245–255. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.4.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg U, Kadefors R, Melin B, Palmeund G, Hassmen P, Engstrom M, Dohns IE. Psychophysiological stress and EMG activity of the trapezius muscle. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;1:354–370. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0104_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mense S. Nociception from skeletal muscle in relation to clinical muscle pain. Pain. 1993;54:241–289. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90027-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael ES, Burns JW. Catastrophizing and pain sensitivity among chronic pain patients: Moderating effects of sensory and affect focus. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:185–194. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2703_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann SA, Waldstein SR. Similar patterns of cardiovascular response during emotional activation as a function of affective valence and arousal and gender. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2001;50:245–253. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prkachin KM, Williams-Avery RM, Zwaal C, Mills DE. Cardiovascular changes during induced emotion: An application of Lang's theory of emotional imagery. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1999;47:255–267. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau H, Elbert T. Psychophysiology of arterial baroreceptors and the etiology of hypertension. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;57:179–201. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(01)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seminowicz DA, Davis KD. Cortical responses to pain in healthy individuals depends on pain catastrophizing. Pain. 2006;120:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjegaard G, Lundberg U, Kudefors R. The role of muscle activity and mental load in the development of pain and degenerative processes of the muscle cell level during computer work. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2000;83:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s004210000285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanos NP, Radtke-Bodorik L, Ferguson JD, Jones B. The effects of hypnotic susceptibility suggestions for analgesia, and the utilization of cognitive strategies on the reduction of pain. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1979;3:282–292. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.88.3.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJL, Bishop S, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: Development and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:524–532. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJL, D'Eon JL. Relation between catastrophizing and depression in chronic pain patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:260–264. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJL, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, Lefebvre JC. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2001;17:52–64. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]