Abstract

Background

The R2R3-MYB genes comprise one of the largest transcription factor gene families in plants, playing regulatory roles in plant-specific developmental processes, metabolite accumulation and defense responses. Although genome-wide analysis of this gene family has been carried out in some species, the R2R3-MYB genes in Beta vulgaris ssp. vulgaris (sugar beet) as the first sequenced member of the order Caryophyllales, have not been analysed heretofore.

Results

We present a comprehensive, genome-wide analysis of the MYB genes from Beta vulgaris ssp. vulgaris (sugar beet) which is the first species of the order Caryophyllales with a sequenced genome. A total of 70 R2R3-MYB genes as well as genes encoding three other classes of MYB proteins containing multiple MYB repeats were identified and characterised with respect to structure and chromosomal organisation. Also, organ specific expression patterns were determined from RNA-seq data. The R2R3-MYB genes were functionally categorised which led to the identification of a sugar beet-specific clade with an atypical amino acid composition in the R3 domain, putatively encoding betalain regulators. The functional classification was verified by experimental confirmation of the prediction that the R2R3-MYB gene Bv_iogq encodes a flavonol regulator.

Conclusions

This study provides the first step towards cloning and functional dissection of the role of MYB transcription factor genes in the nutritionally and evolutionarily interesting species B. vulgaris. In addition, it describes the flavonol regulator BvMYB12, being the first sugar beet R2R3-MYB with an experimentally proven function.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12870-014-0249-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Beta vulgaris, Caryophyllales, R2R3-MYB, Transcription factor, Gene family, Flavonol regulator

Background

Transcriptional control of gene expression influences almost all biological processes in eukaryotic cells or organisms. Transcription factors perform this function, alone or complexed with other proteins, by activating or repressing (or both) the recruitment of RNA polymerase to specific genes. The large number and diversity of transcription factors is related to their substantial regulatory complexity [1].

MYB proteins are widely distributed in all eukaryotic organisms and constitute one of the largest transcription factor families in the plant kingdom. MYB proteins are defined by a highly conserved MYB DNA-binding domain, mostly located at the N-terminus, generally consisting of up to four imperfect amino acid sequence repeats (R) of about 52 amino acids, each forming three alpha–helices [2]. The second and third helices of each repeat build a helix–turn–helix (HTH) structure with three regularly spaced tryptophan (or hydrophobic) residues, forming a hydrophobic core [3]. The third helix of each repeat is the DNA recognition helix that makes direct contact with DNA [4]. During DNA contact, two MYB repeats are closely packed in the major groove, so that the two recognition helices bind cooperatively to the specific DNA recognition sequence motif.

MYB proteins can be divided into different classes depending on the number of adjacent repeats (one, two, three or four). The three repeats of the prototypic MYB protein c-Myb [5] are referred to as R1, R2 and R3, and repeats from other MYB proteins are named according to their similarity. Plant R1R2R3-type MYB (MYB3R) proteins have been proposed to play divergent roles in cell cycle control [6,7], similar to the functions of their animal homologs.

Most plant MYB genes encode R2R3-MYB class proteins, containing two repeats [2,8], which are thought to have evolved from an R1R2R3-MYB gene ancestor, by the loss of the sequences encoding the R1 repeat and subsequent expansion of the gene family [9-11]. R2R3-MYB transcription factors have a modular structure, with the N-terminal MYB domain as DNA-binding domain and an activation or repression domain usually located at the highly variable C-terminus. Components for the establishment of protein-protein interactions with other components of the eukaryotic transcriptional machinery have been detected in the N-terminal module [12-14].

Based on the conservation of the MYB domain and of common amino acid motifs in the C-terminal domains, R2R3-MYB proteins have been divided into several subgroups which often group proteins with functional relationship. The reliability of the subgroups defined on the basis of phylogenetic analysis is also supported by additional criteria, such as the gene structure and the presence and position of introns [15]. Most of these subgroups, defined first for the proteins of A. thaliana [2,16,17], are also present, and are sometimes expanded, in other higher plants. Comparative phylogenetic studies have identified new R2R3-MYB subgroups in other plant species for which there are no representatives in A. thaliana (e.g. in rice, poplar and grapevine), suggesting that these proteins might have specialised functions which were either lost in A. thaliana or were acquired after divergence from the last common ancestor [18-20].

As initially described in the first plant MYB gene family review [21], the expansion of the plant-specific R2R3-MYB gene family is thought to be correlated with the increase in complexity of plants, particularly in Angiosperms. Consequently, the functions of R2R3-MYB genes are likely associated with regulating plant-specific processes including primary and secondary metabolism, developmental processes, cell fate and identity and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses [2,17,21].

With the growing number of fully sequenced plant genomes, the identification of R2R3-MYB genes has increased in recent times. Based on their well conserved MYB domains, R2R3-MYB gene families have been annotated genome-wide in A. thaliana (126 members) [17], Zea mays (157 members) [22], Oryza sativa (102 members) [23], Vitis vinifera (117 members) [19], Populus trichocarpa (192 members) [20], Glycine max (244 members) [15], Cucumis sativus (55 members) [24] and Malus x domestica (222 members) [25]. Given the potential roles of R2R3-MYB proteins in the regulation of gene expression, secondary metabolism, and responses to environmental stresses, and that Beta vulgaris ssp. vulgaris (order Caryophyllales) is the first non-rosid, non-asterid eudicot for which the genome has been sequenced [26], it is of interest to achieve a complete identification and classification of MYB genes in this species with respect to the number, chromosome locations, phylogenetic relationships, conserved motifs as well as expression patterns. Particularly, since sugar beet is an important crop of the temperate climates as a source for bioethanol as well as animal feed and provides nearly 30% of the worlds annual sugar production [26].

In the present study, we describe the R2R3-MYB gene family by means of in silico analysis of the B. vulgaris genome sequence, in order to predict protein domain architectures, and to assess the extent of conservation and divergence between B. vulgaris and A. thaliana gene families, thus leading to a functional classification of the sugar beet MYB genes on the basis of phylogenetic analyses. Furthermore, RNA-seq data was used to analyse expression in different B. vulgaris organs and to compare expression patterns of closely grouped co-orthologs. To validate the functional classification, a candidate gene was chosen for cDNA isolation and subsequent functional analysis by transient transactivation assays and complementation of an orthologous A. thaliana mutant. We identified the R2R3-MYB gene Bv_iogq activating two flavonol biosynthesis enzyme promoters and complementing the flavonol-deficient myb11 myb12 myb111 mutant, and thus encoding a functional flavonol biosynthesis regulator. Our findings provide the first step towards further investigations on the biological and molecular functions of MYB transcription factors in the economically and evolutionarily interesting species B. vulgaris.

Results and discussion

The annotated genome sequence of B. vulgaris has recently become available. It has been obtained from the double haploid breeding line KWS2320 [26]. The sequence has been assigned to nine chromosomes and B. vulgaris was predicted to contain 27,421 protein-coding genes (RefBeet) in 567 Mb from which 85% are chromosomally assigned.

Identification and genomic distribution of B. vulgaris R2R3-MYB genes

MYB protein coding genes in B. vulgaris were identified using a consensus R2R3-MYB DNA binding domain sequence as protein query in TBLASTN searches on the RefBeet genome sequence. The putative MYB sequences were manually analysed for the presence of an intact MYB domain to ensure that the gene models contained two or more (multiple) MYB repeats, and that they mapped to unique loci in the genome. We identified six B. vulgaris MYB (BvMYB) genes which had been missed in the automatic annotation [26] and two which had been annotated with incomplete open reading frames. We created a primary data set of 70 R2R3-MYB proteins and three types of atypical multiple repeat MYB proteins distantly related to the typical R2R3-MYB proteins: three R1R2R3-MYB (MYB3R) proteins, one MYB4R protein and one CDC5-like protein from the B. vulgaris genome (Table 1). The number of atypical multiple repeat MYB genes identified in B. vulgaris is in the same range as those reported for other plant species, with for example up to six MYB3R and up to two MYB4R and CDC5-like genes. However, the number of R2R3-MYB genes is one of the smallest among the species that have been studied (ranging from 55 in C. sativus to in 244 G. max). As discussed below, this is probably due to the absence of recent genome duplication events in B. vulgaris.

Table 1.

List of annotated MYB genes with two or more repeats in the B. vulgaris ssp. vulgaris (KWS2320) genome

| Gene ID | Gene code | Chr. | Position on pseudochr. | Clade (subgroup) | Landmark MYB in clade | Functional assignment | Protein length [aa] | Exon nr. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iquc | Bv1g001230_iquc | 1 | 1,379,505 | 1,381,156 | C14 (S4) | AtMYB4, HvMYB5 | Metabolism | 341 | 3 |

| owzx | Bv1g001750_owzx | 1 | 1,903,239 | 1,898,047 | C8 (S3) | AtMYB58, AtMYB63 | Metabolism | 316 | 3 |

| dwki | Bv1g002800_dwki | 1 | 3,065,434 | 3,067,536 | C18 (S5) | VvMYBPA | Metabolism | 335 | 2 |

| qxpi | Bv1g006050_qxpi | 1 | 6,597,147 | 6,601,421 | C3 | AtLMI2 | Development | 303 | 3 |

| ksfi | Bv1g014750_ksfi | 1 | 32,690,615 | 32,692,641 | C12 (S14) | SlBLIND, AtRAX1 | Development | 363 | 3 |

| zqor | Bv1ug018140_zqor | 1un | 38,330,908 | 38,328,715 | C28 (S18) | HvGAMYB, AtDUO1 | Development | 303 | 3 |

| jxgt | Bv1ug021520_jxgt | 1un | 45,201,741 | 45,199,866 | C36 (S21) | AtLOF1, AtMYB52 | Devel., metab. | 350 | 2 |

| uksi | Bv2g023560_uksi | 2 | 127,507 | 126,341 | C35 (S23) | 253 | 1 | ||

| wdyc | Bv2g024650_wdyc | 2 | 1,373,912 | 1,378,227 | C35 (S23) | 416 | 2 | ||

| ihfg | Bv2g027580_ihfg | 2 | 4,418,041 | 4,424,427 | C15 | FaMYB1 | Metabolism | 199 | 3 |

| jkkr | Bv2g027795_jkkr | 2 | 4,723,639 | 4,720,911 | C21 | (metabolism) | 224 | 3 | |

| mxck | Bv2g027990_mxck | 2 | 4,981,898 | 4,984,692 | C29 | 286 | 4 | ||

| xprd | Bv2g029260_xprd | 2 | 6,275,539 | 6,272,224 | C27 | EgMYB2, PtMYB4 | Metabolism | 422 | 2 |

| ralf | Bv2g030925_ralf | 2 | 8,431,718 | 8,435,595 | C21 | (metabolism) | 237 | 3 | |

| ghua | Bv2g031800_ghua | 2 | 9,813,407 | 9,800,544 | C37 (MYB3R) | AtMYB3R1 | Cell cycle | 1050 | 11 |

| huqy | Bv2g039110_huqy | 2 | 27,806,443 | 27,798,295 | C26 | AtMYB26 | Development | 329 | 2 |

| dcmm | Bv2g040720_dcmm | 2 | 33,641,162 | 33,643,072 | C1 (S9) | AmMIXTA, AtNOK | differentiation | 454 | 3 |

| mxwz | Bv2g041120_mxwz | 2 | 34,717,448 | 34,719,429 | C11 | AtTDF1 | Development | 331 | 3 |

| nqis | Bv2ug047120_nqis | 2un | 45,488,410 | 45,491,366 | C4 (S1) | AtMYB30 | Defense | 344 | 3 |

| urrg | Bv3g049510_urrg | 3 | 1,126,350 | 1,124,818 | C9 (S2) | NtMYB1, AtMYB13 | Defense | 288 | 3 |

| hwcc | Bv3g050090_hwcc | 3 | 1,847,195 | 1,845,526 | C6 (S24) | 360 | 3 | ||

| cwtt | Bv3ug070140_cwtt | 3un | 35,695,445 | 35,697,294 | C29 | 242 | 3 | ||

| cjuq | Bv4g071740_cjuq | 4 | 221,407 | 222,747 | C19 | VvMYB5a | Metabolism | 306 | 2 |

| yruo | Bv4g073190_yruo | 4 | 1,667,414 | 1,671,378 | C27 | EgMYB2, PtMYB4 | Metabolism | 397 | 2 |

| ygxg | Bv4g074860_ygxg | 4 | 3,396,314 | 3,392,041 | C28 (S18) | HvGAMYB, AtDUO1 | Development | 556 | 3 |

| skuh | Bv4g078900_skuh | 4 | 7,533,943 | 7,547,807 | C42 (MYB4R) | AtMYB4R1 | 919 | 12 | |

| zfig | Bv4g079610_zfig | 4 | 8,546,454 | 8,544,269 | C25 (S13) | AtMYB61 | Metabolism | 449 | 3 |

| oref | Bv4g079670_oref | 4 | 8,669,284 | 8,678,138 | C41 (CDC5) | AtCDC5 | Cell cycle | 991 | 4 |

| josh | Bv4g083815_josh | 4 | 16,552,338 | 16,566,035 | 209 | 3 | |||

| rwwj | Bv4g084340_rwwj | 4 | 18,292,096 | 18,285,979 | C14 (S4) | AtMYB4, HvMYB5 | Metabolism | 322 | 3 |

| xwne | Bv4g091510_xwne | 4 | 32,888,798 | 32,889,966 | C11 | AtTDF1 | Development | 316 | 3 |

| jofq | Bv5g098940_jofq | 5 | 834,523 | 837,220 | C10 | 294 | 2 | ||

| sskd | Bv5g100530_sskd | 5 | 2,767,018 | 2,770,045 | C23 | AtMYB103 | Development | 378 | 3 |

| mhxh | Bv5g101320_mhxh | 5 | 3,800,529 | 3,804,868 | C37 (MYB3R) | AtMYB3R1 | Cell cycle | 525 | 7 |

| zkef | Bv5g107260_zkef | 5 | 14,451,259 | 14,465,332 | 272 | 2 | |||

| ztyd | Bv5g110930_ztyd | 5 | 25,553,310 | 25,538,334 | C32 (S19) | AtMYB21 | Development | 231 | 3 |

| udmh | Bv5g110960_udmh | 5 | 25,780,619 | 25,782,807 | C4 (S1) | AtMYB30 | Defense | 293 | 3 |

| tcwd | Bv5g112510_tcwd | 5 | 31,754,754 | 31,740,788 | C37 (MYB3R) | AtMYB3R1 | Cell cycle | 549 | 7 |

| nmrg | Bv5g115970_nmrg | 5 | 42,841,475 | 42,839,260 | C4 (S1) | AtMYB30 | Defense | 334 | 3 |

| oaxt | Bv5g116880_oaxt | 5 | 44,348,080 | 44,350,042 | C11 | AtTDF1 | Development | 356 | 3 |

| tfkh | Bv5g118200_tfkh | 5 | 46,474,363 | 46,471,416 | C38 (S25) | AtPGA37 | Development | 501 | 3 |

| ahtj | Bv5g118320_ahtj | 5 | 46,667,594 | 46,670,167 | C38 (S25) | AtPGA37 | Development | 456 | 3 |

| cfqe | Bv5g118940_cfqe | 5 | 47,478,672 | 47,484,506 | 354 | 3 | |||

| roao | Bv5g122000_roao | 5 | 50,845,046 | 50,849,238 | C9 (S2) | NtMYB1, AtMYB13 | Defense | 304 | 3 |

| iogq | Bv5g122370_iogq | 5 | 51,297,529 | 51,287,534 | C13 (S7) | ZmP, AtPFG1 | Metabolism | 387 | 3 |

| ijmc | Bv5g123335_ijmc | 5 | 52,180,596 | 52,182,338 | C33 (S20) | TaPIMP1, AtBOS1 | Def., devel. | 313 | 3 |

| ohkk | Bv5ug126300_ohkk | 5un | 58,923,676 | 58,920,132 | C39 | AmPHAN, AtAS1 | Development | 369 | 1 |

| knac | Bv5ug126380_knac | 5un | 59,366,406 | 59,371,048 | C36 (S21) | AtLOF1, AtMYB52 | Devel., metab. | 354 | 3 |

| qcwx | Bv5ug126530_qcwx | 5un | 60,109,952 | 60,111,819 | C7 (S11) | AtMYB102 | Defense | 334 | 2 |

| such | Bv6g128620_such | 6 | 508,583 | 510,104 | C34 (S22) | AtMYB44 | Def., devel. | 313 | 1 |

| hwmt | Bv6g129790_hwmt | 6 | 2,064,496 | 2,062,852 | C12 (S14) | SlBLIND, AtRAX1 | Development | 321 | 3 |

| oypc | Bv6g136060_oypc | 6 | 9,418,772 | 9,413,559 | C6 (S24) | 326 | 3 | ||

| usyi | Bv6g142590_usyi | 6 | 24,870,820 | 24,874,245 | C33 (S20) | TaPIMP1, AtBOS1 | Def., devel. | 275 | 3 |

| qttn | Bv6g154730_qttn | 6 | 58,819,129 | 58,822,997 | C36 (S21) | AtLOF1, AtMYB52 | Devel., metab. | 461 | 3 |

| zeqy | Bv6g155340_zeqy | 6 | 59,766,073 | 59,770,527 | C40 | AtFLP | Differentiation | 445 | 12 |

| yejr | Bv7g162730_yejr | 7 | 7,720,067 | 7,722,320 | C12 (S14) | SlBLIND, AtRAX1 | Development | 380 | 3 |

| ahzs | Bv7g172570_ahzs | 7 | 37,491,045 | 37,494,304 | C26 | AtMYB26 | Development | 405 | 3 |

| eztu | Bv7g172590_eztu | 7 | 37,594,009 | 37,596,132 | C26 | AtMYB26 | Development | 417 | 3 |

| qzms | Bv7g174540_qzms | 7 | 40,066,216 | 40,070,163 | C38 (S25) | AtPGA37 | Development | 481 | 3 |

| ksge | Bv7g176420_ksge | 7 | 42,070,277 | 42,071,595 | C30 | AtMYB59 | Development | 249 | 3 |

| qzfy | Bv7ug180860_qzfy | 7un | 49,349,681 | 49,351,461 | C31 | 264 | 3 | ||

| dxny | Bv8g183050_dxny | 8 | 719,286 | 716,855 | C7 (S11) | AtMYB102 | Defense | 409 | 3 |

| zguf | Bv8g183060_zguf | 8 | 734,446 | 721,513 | C7 (S11) | AtMYB102 | Defense | 396 | 3 |

| jona | Bv8g199535_jona | 8 | 37,703,170 | 37,704,769 | C12 (S14) | SlBLIND, AtRAX1 | Development | 271 | 3 |

| khqq | Bv8g200250_khqq | 8 | 38,542,747 | 38,540,562 | C12 (S14) | SlBLIND, AtRAX1 | Development | 368 | 3 |

| gjwr | Bv9g216350_gjwr | 9 | 33,882,588 | 33,884,593 | C14 (S4) | AtMYB4, HvMYB5 | Metabolism | 276 | 2 |

| krez | Bv9g225930_krez | 9 | 44,634,979 | 44,633,906 | C34 (S22) | AtMYB44 | Def., devel. | 253 | 1 |

| ezhe | Bvg229250_ezhe | rnd0020 | 411,935 | 416,451 | C28 (S18) | HvGAMYB, AtDUO1 | Development | 410 | 3 |

| crae | Bvg229400_crae | rnd0039 | 39,535 | 40,725 | C17 (S5) | AtTT2 | Metabolism | 282 | 3 |

| entg | Bvg229850_entg | rnd0043 | 141,170 | 143,052 | C33 (S20) | TaPIMP1, AtBOS1 | Def., devel. | 310 | 3 |

| swwi | Bvg235150_swwi | rnd0157 | 176,581 | 179,181 | 191 | 3 | |||

| oyjz | Bvg238960_oyjz | rnd0254 | 47,161 | 49,928 | C3 | AtLMI2 | Development | 239 | 3 |

| dani | Bvg239075_dani | rnd0254 | 156,586 | 162,101 | C24 (S16) | AtLAF1 | Development | 285 | 3 |

| sjwa | Bvg239080_sjwa | rnd0254 | 178,734 | 182,264 | C24 (S16) | AtLAF1 | Development | 278 | 3 |

| pgya | Bvg243050_pgya | rnd0446 | 12,407 | 14,214 | 326 | 3 | |||

The genes are ordered by RefBeet pseudochromosomes, from north to south. The unique, immutable four-letter identifier (gene ID) is given in the first column. The modifiable, annotation-version-specific gene code describing the chromosomal assignment and position on pseudochromosomes is given in the second column. "un" indicates the assignment to a chromosome without position and "rnd" indicates scaffolds without chromosomal assignment. Clade classification and functional assignment is based on the NJ tree presented in Figure 3.

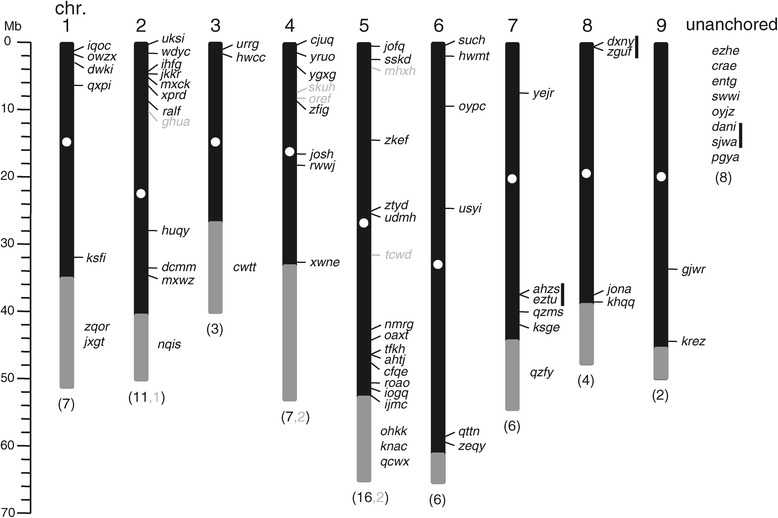

A keyword search in the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) revealed three previously annotated B. vulgaris MYB proteins from different sugar beet cultivars: AET43456 and AET43457, both corresponding to BvR2R3-MYB Bv_jkkr in this work and AEL12216, corresponding to Bv_nqis in this work. The identified 75 BvMYB genes, constituting approximately 0.27% of the 27,421 predicted protein-coding B. vulgaris genes and 5.9% of the 1271 putative B. vulgaris transcription factor genes [26], were subjected for further analyses. Similar to all other genes in the annotated B. vulgaris genome (RefBeet), a unique, immutable four-letter identifier (ID) was assigned to each BvMYB gene (Table 1). This immutable ID is part of the gene designator used in the B. vulgaris nomenclature system and should be stable, in contrast to the designator elements describing the chromosomal assignment and position on pseudochromosomes which may change when currently unassigned or unanchored scaffolds are integrated into the pseudochromosomes. Hereafter the four-letter-ID is used to name individual BvMYB genes and the deduced proteins. On the basis of RefBeet, 67 of the 75 BvMYB genes could be assigned to the nine chromosomes. On average, one R2R3-MYB gene was present every 10.5 Mb. The chromosomal distribution of BvMYB genes on the pseudochromosomes is shown in Figure 1 and revealed that B. vulgaris MYB genes were distributed throughout all chromosomes. Although each of the nine B. vulgaris chromosomes contained MYB genes, the distribution appeared to be uneven (Figure 1). The BvMYB gene density per chromosome was patchy, with only two BvR2R3-MYB genes present on chromosome 9, while 16 were found on chromosome 5. In general, the central sections of chromosomes including the centromeres and the pericentromere regions, lack MYB genes. Relatively high densities of BvMYB genes were observed at the chromosome ends, with highest densities observed at the top of chromosome 2 and at the bottom of chromosome 5 (Figure 1). This uneven distribution was previously observed for Z. mays, G. max and M. x domestica R2R3-MYB genes [15,22,25].

Figure 1.

Chromosomal distribution of BvMYB genes. R2R3-MYB genes are present on all nine chromosomes in the B. vulgaris genome. Each broad vertical bar represents one chromosome drawn to scale. The black parts indicate concatenated scaffolds and grey parts mark scaffolds assigned to a chromosome without detailed position. The positions of centromeres (white dots) are roughly estimated from repeats distribution data. The chromosomal positions of the MYB genes (given in four-letter-ID) are indicated by horizontal lines. R2R3-MYB genes are given in black letters and other MYB genes are given in grey letters. The bracketed numbers below the chromosomes show the number of MYB genes on this chromosome. Eight R2R3-MYB genes could not be localised to a specific chromosome (unanchored). Vertical black lines indicate R2R3-MYB genes which are located in close proximity (sister gene pairs).

The total number of identified MYB genes was, compared to other plant species, low in B. vulgaris. Even if some MYB genes may have been missed due to gaps in the reference sequence, this does not adequately explain the small number. High numbers of MYB genes in a species are mainly attributed to ancestral whole genome duplication events as known for A. thaliana, O. sativa, P. trichocarpa, G. max and M. x domestica [27-31]. The absence of a recent lineage-specific whole genome duplication event in B. vulgaris [32] is further substantiated by the detection of only 70 R2R3-MYB genes, because a lack of this duplication event can easily explain the small number of MYB genes in this species. This interpretation is in accordance with the findings in cucumber, where the number of R2R3-MYB genes has been reported to be 55 [24].

We further determined physically linked sister BvMYB gene pairs along the nine chromosomes (Figure 1, marked with vertical black bars), which form clusters and may have evolved from local intrachromosomal duplication events that result in tandem arrangement of the duplicated gene. Three gene pairs have been identified: one on chromosome 7 consisting of the closely related genes Bv_ahzu and Bv_eztu, a second on the top of chromosome 8 with Bv_dxny and Bv_zguf and a third on an unlinked scaffold (0254.scaffold00675) constituted of Bv_dani and Bv_sjwa. The BvMYB genes of the two latter pairs were physically located near to each other without intervening annotated genes between. In total, about 5% (6 of 75) of BvMYBs were involved in tandem duplication, which is the same value as reported for MYB genes in soybean [15]. Moreover, an incomplete gene pair was observed on chromosome 2, where a solitary typically R2R3-MYB "third exon" containing sequences encoding a part of a R3 repeat and the C-terminal region was found about 18.7 kb downstream of Bv_jkkr showing 88% identity on cDNA- and 82% identity on deduced protein level to the third exon of the near Bv_jkkr.

Gene structure analysis revealed that most BvR2R3-MYB genes (53 of 70, 76%) follow the previously reported rule of having two introns and three exons, and display the highly conserved splicing arrangement that has also been reported for other plant species [15,22,24]. Eleven BvR2R3-MYB genes (16%) have one intron and two exons and four (6%) were one exon genes. Only two BvR2R3-MYB genes have more than three exons: Bv_mxck with four exons and Bv_zeqy with twelve exons (Table 1). The complex exon-intron structure of Bv_zeqy is known from its A. thaliana orthologs AtMYB88 and AtMYB124/FOUR LIPS (FLP) containing ten and eleven exons, respectively, and more than the typically zero to two introns in the MYB domain coding sequences [18,19]. This supports their close evolutionary relationship, but also indicates the conservation of this intron pattern in evolution since the split of the Caryophyllales from the precursor of rosids and asterids.

Sequence features of the MYB domains

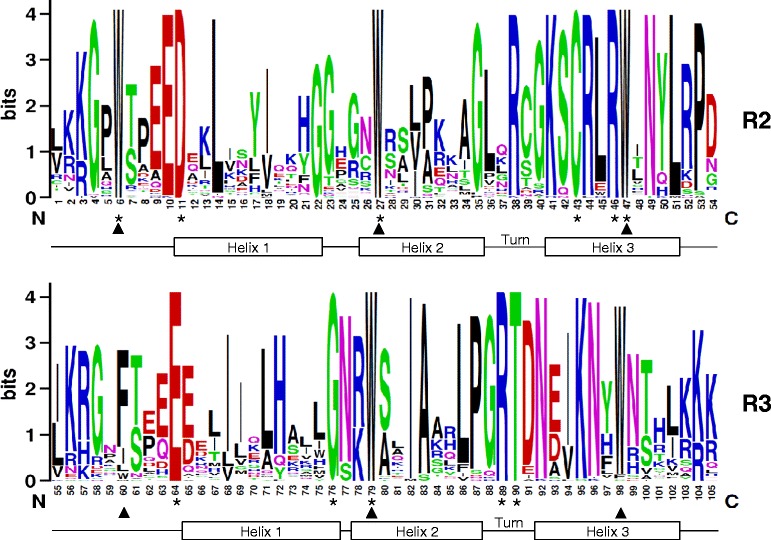

To investigate the R2R3-MYB domain sequence features, and the frequencies of the most prevalent amino acids at each position within each repeat of the B. vulgaris R2R3-MYB domain, sequence logos were produced through multiple alignment analysis (ClustalW) using the 70 deduced amino acid sequences of R2 and R3 repeats, respectively. In general, the two MYB repeats covered about 104 amino acid residues (including the linker region), with rare deletions or insertions (Additional file 1). As shown in Figure 2, the distribution of conserved amino acids among the B. vulgaris MYB domain was very similar to those of A. thaliana, Z. mays, O. sativa, V. vinifera, P. trichocarpa, G. max and C. sativus. The R2 and R3 MYB repeats of the B. vulgaris R2R3-MYB family contained characteristic amino acids, including the most prominent series of regularly spaced and highly conserved tryptophan (W) residues, which are known to play a key role in sequence-specific DNA binding, serving as landmarks of plant MYB proteins. As known from orthologs in other plant species, the first conserved tryptophan residue in the R3 repeat (position 60, W60) could be replaced by F or less frequently by isoleucine (I), leucine (L) or tyrosine (Y). Interestingly, the position 98 of the MYB repeat, which contains the last of the conserved tryptophan residues (W98), is not completely conserved in the B. vulgaris R2R3-MYBs (Figure 2, Additional file 1). A phenylalanine (F) residue, found in Bv_ralf and Bv_zeqy, has been reported very rarely at this position (e.g. in ZmMYB29) [22], but an atypical cysteine (C) at this important position, as found in Bv_jkkr, has not been described yet. This makes the R2R3-MYB protein Bv_jkkr interesting for further analyses in respect to DNA-binding and target sequence specificities.

Figure 2.

Sequence conservation of the R2R3-MYB domain. The R2 and R3 MYB repeats are highly conserved across all BvR2R3-MYB proteins. The logos base on alignments of all R2 and R3 MYB repeats of BvR2R3-MYBs. The overall height of each stack indicates the conservation of the sequence at the given position within the repeat, while the height of symbols within the stack indicates the relative frequency of each amino acid at that position. The asterisks indicate positions of the conserved amino acids that are identical among all 70 B. vulgaris R2R3-MYB proteins. Arrowheads indicate the typical, conserved tryptophan residues (W) in the MYB domain.

In addition to the highly conserved tryptophan residues, we observed amino acid residues that are conserved in all B. vulgaris R2R3-MYBs: D11, C43, R46 in the R2 repeat and E64, G76, R89 and T90 in the R3 repeat. Further highly conserved residues of the B. vulgaris R2R3-MYB domains are: G4, E10, L14, G35, R38, K41, R44, N49, L51 and P53 in the R2 repeat and I82, A83, N92, K95 and N96 in the R3 repeat (Figure 2). These highly conserved amino acid residues are mainly located in the third helix and the turn of the helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif, which is in good accordance with the findings in other plant species.

Phylogenetic analysis of the B. vulgaris MYB family

To explore the putative function of the predicted B. vulgaris MYBs, we assigned them to functional clades known from A. thaliana, which was chosen because most of our knowledge about plant MYB genes has been obtained from studies of this major plant model. As known from similar studies, most MYB proteins sharing similar functions cluster in the same phylogenetic clades, suggesting that most closely-related MYBs could recognise similar target genes and possess redundant, overlapping, and/or cooperative functions.

We performed a phylogeny reconstruction of 75 BvMYBs, the complete A. thaliana MYB family (133 members, including 126 R2R3-MYB, five MYB3R, one MYB4R and one CDC5-MYB) and 51 well-characterised landmark R2R3-MYBs from other plant species, using the neighbour-joining (NJ) method (Figure 3) and the maximum parsimony (MP) method (Additional file 2) in MEGA5 [33]. With the exception of some inner nodes with low bootstrap support values, the phylogenetic trees derived from each method displayed very similar topologies. We took this as an indication of reliability of our clade- and subgroup designations. The phylogenetic tree topology allowed us to classify the analysed MYB proteins into 42 clades (C1 to C42) (Figure 3). In our classification of the MYB genes, we also considered the subgroup (S) categories from A. thaliana [2,17]. Our classification resulted in the same clusters as those presented in previous studies for grape and soybean [15,19]. As shown in Figure 3, 34 out of 42 clades were present both in B. vulgaris and A. thaliana. Thus, it is likely that the appearance of most MYB genes in these two species predates the branch-off of Caryophyllales before the separation of asterids and rosids [26].

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic Neighbor Joining (NJ) tree (1000 bootstraps) with MYB proteins from Beta vulgaris (Bv), Arabidopsis thaliana (At) and landmark MYBs from other plant species built with MEGA5.2. Clades (and Subgroups) are labeled with different alternating tones of grey background. Functional annotation of clade members are given. The numbers at the branches give bootstrap support values from 1000 replications.

We also observed species-specific clades and clades containing B. vulgaris or A. thaliana MYB proteins together with landmark MYBs from other species. It should be noted that we use the term "species-specific" in the context of the current set of species with sequenced genomes. Significantly more genome sequences would be required to resolve the presence and absence of genes or clades at the genus or family level. As indicated also from other studies, the observation of species-specific clades may be taken as a hint that MYB genes may have been acquired or been lost in a single species, during the following divergence from the most recent common ancestor. For example, members of the clade C2 (subgroup S12, with HIGH ALIPHATIC GLUCOSINOLATE1 (AtHAG1), HIGH INDOLIC GLUCOSINOLATE1 (AtHIG1), ALTERED TRYPTOPHAN REGULATION1 (AtATR1)) have been identified as glucosinolate biosynthesis regulators [34-37]. No BvMYBs were grouped within this clade, containing members which are predominantly present in plants of the glucosinolate compounds accumulating Brassicaceae family. A previous study indicated that this clade was derived from a duplication event before Arabidopsis diverged from Brassica [23]. Another MYB clade without B. vulgaris orthologs was C20 (S15), that include the landmark R2R3-MYBs AtMYB0/GLABRA1 and AtMYB66/WEREWOLF (Figure 3), which are known to be involved in epidermal cell development leading to the formation of trichomes and root hairs [38-40]. Similar observations have been made in the non-rosids maize and soybean [15,22], both not containing C20 (S15) orthologs, while the rosids grape and poplar do [19,20]. As GLABRA1-like MYB genes have been hypothesised to have been acquired in rosids after the rosid-asterids division [41,42], the absence of BvMYBs in this clade is consistent with this hypothesis, since Caryophyllales branched off before the separation of asterids and rosids. Trichome formation in B. vulgaris thus could be regulated by genes of the evolutionary older MIXTA clade C1 (S9) [41] whose members are also known to play a role in multicellular trichome formation [43]. Therefore, Bv_dcmm as the only sugar beet gene in this clade, is a candidate to encode a trichome development regulator. Further clades without BvMYBs are C5 (S10) containing the A. thaliana proteins AtMYB9, AtMYB107 with unknown functional assignment, C16 (S5) containing R2R3-MYB landmark anthocyanin regulators from monocots and C22 (S6) including the landmark R2R3-MYB factors PRODUCTION OF ANTHOCYANIN PIGMENT1 (AtPAP1), ANTHOCYANIN2 (PhAN2) and ROSEA1 (AmROSEA1), which are known to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in many species [44-47]. The lack of BvMYBs in the two latter clades fits to the observation, that plants of the genus Beta do not produce anthocyanin pigments [48]. The Caryophyllales is the single order in the plant kingdom that contains taxa that have replaced anthocyanins with chemically distinct but functionally identical red and yellow pigments - the indole-derived betalains, named from Beta vulgaris, from which betalains were first extracted [49]. Although betalains have functions analogous to those of anthocyanins as pigments, anthocyanins and betalains are mutually exclusive pigments in plants [50].

Three clades do not contain any A. thaliana MYB (Figure 3). Two of them contain landmark MYBs and B. vulgaris MYBs: C18 (S5) and C15, functionally assigned to proanthocyanidin regulation and repression of flavonoid biosynthesis, respectively. One clade contains only BvMYBs. Clade C21, constituted of the two BvMYBs (Bv_ralf and Bv_jkkr), was found close to the "anthocyanin" regulator representing clade C22 (S6) in the phylogenetic trees (Figure 3, Additional file 3). This clade could be described as a lineage-specific expansion in B. vulgaris, reflecting a species-specific adaptation. Two classical, linked beet pigment loci, RED (R) and YELLOW (Y) [51,52], are known to influence the production of betalains in beet. Recently, the R locus was shown to encode a cytochrome P450 (CYP76AD1, Bv_ucyh in KWS2320) [53]. It has been hypothesised that the betalain pathway may have co-opted the anthocyanin regulators because both pigment types are produced in a similar temporal and spatial pattern [53]. Thus, a R2R3-MYB-type transcriptional activator, homologues to the anthocyanin pigment regulators, is thought to control betalain biosynthesis through regulation of the biosynthetic enzymes R (CYP76AD1) and DODA (4,5-DOPA-dioxygenase) [53,54]. The two C21 BvMYB genes Bv_jkkr and Bv_ralf are both located on chromosome 2 close to the R locus, as indicated by the chromosome-based gene designations (Bv2g027795_jkkr, Bv2g029890_ucyh, Bv2g030925_ralf). As the R and Y loci are known to be linked at a genetically distance of about 7.5 cM [51,52], this makes the R2R3-MYB genes Bv_ralf and Bv_jkkr candidates for encoding the Y regulator. A closer inspection of the MYB domains of Bv_ralf and Bv_jkkr, and comparison to anthocyanin regulator MYBs, revealed some interesting features of C21 clade MYBs which could cause the separation of C21 and C22 MYBs (Figure 3). C21 MYBs do not contain the bHLH-binding consensus motif [D/E]Lx2[R/K]x3Lx6Lx3R [13] found in all bHLH-interacting R2R3-MYBs, suggesting that Bv_ralf and Bv_jkkr, in contrast to the C22 anthocyanin regulator MYBs, do not interact with bHLH proteins. A key amino acid residue in the R3 repeat, identified by Heppel et al. [55] in separating anthocyanin regulators (A89) from proanthocyanidin regulators (G89), is represented by isoleucine (I89) in C21 MYBs. Furthermore, one of the amino acid residues in the third helix of R2 repeat, known to be directly involved in DNA binding (position 44), differs from those found at this position in anthocyanin regulators (Additional file 1), maybe indicating a different target promoter specificity. In this direction also the atypical cysteine at the highly conserved position 98 in the MYB domain of Bv_jkkr may be important as discussed below.

A motif search in the BvMYB proteins for the above mentioned bHLH-interaction motif [13] identified seven BvMYBs containing this motif and thus putatively interacting with bHLH proteins. These seven BvMYBs were all functionally assigned to clades containing (potentially) known bHLH-interacting R2R3-MYBs: Bv_crae, Bv_swwi and Bv_dwki were assigned to the proanthocyanidin regulator clade C17 (S5), Bv_ihfg to clade C15 containing the negative flavonoid regulator FaMYB1 [56], Bv_cjuq to clade C19 containing the general phenylpropanoid pathway regulator VvMYB5a [57] and Bv_gjwr and Bv_iquc to the "repressors" clade C14 (S4).

Six B. vulgaris MYB proteins, Bv_uksi, Bv_josh, Bv_cfqe Bv_ijmc, Bv_swwi and Bv_pgya did not cluster in any of the identified clades or subgroups or showed ambiguous placements between the different phylogenetic trees, implying that these BvMYB proteins may have specialised roles that were acquired or expanded in B. vulgaris during the process of genome evolution.

Basically, higher numbers of AtMYBs than their BvMYB orthologs were found in most clades, indicating that they were duplicated after the divergence of the two lineages. For example, the phylogeny for C28 (S18) and C36 (S21) included only three BvMYBs and eight AtMYBs, or C25 (S13) with one BvMYB and four AtMYBs. By contrast, three BvMYBs and two AtMYB were found in clade C26. As mentioned above, the higher number of MYB genes in A. thaliana is presumably mainly due to an ancestral duplication of the entire genome and subsequent rearrangements, followed by gene loss and extensive local gene duplications taken place in the evolution of Arabidopsis [27].

Expression profiles for B. vulgaris MYB genes in different developmental stages

In large transcription factor families functional redundancy is not unusual. Thus, a particular transcription factor has often to be studied and characterised in the context of the whole family. In this context, the gene expression pattern can provide important clues for gene function. We used genome-mapped global RNA-seq Illumina reads from the B. vulgaris reference genotype KWS2320 [26] to analyse the expression of the 75 BvMYB genes in different organs and developmental stages: seedlings, taproot (conical white fleshy root), young and old leaves, inflorescences and seeds. Filtered RNA-seq reads were aligned to the genome reference sequence and the number of mapped reads per annotated transcript were quantified and statistically compared across the analysed samples giving normalised RNA-seq read values which are given in Additional file 3. In common with other transcription factor genes, many of the BvMYBs exhibited low transcript abundance levels, as determined by the RNA-seq analysis.

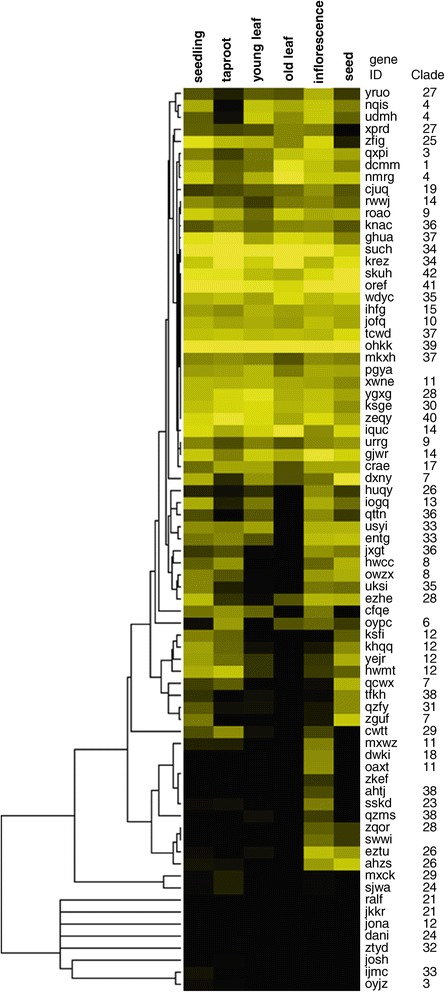

Our expression analysis revealed that B. vulgaris MYBs have a variety of expression patterns in different organs. We undertook hierarchical clustering of the profiles to identify similar transcript abundance patterns and generated an expression heatmap in order to visualise the different expression profiles of the BvMYBs (Figure 4). The highest number of BvMYB genes (66; corresponding to 88%) are expressed in inflorescences, followed by seedlings (62; 83%), taproot (58; 77%), seeds (55; 73%) and young leaves (51; 68%). The fewest BvMYB genes are expressed in old leaves (35; 47%). 70 BvMYBs (93%) are expressed in at least one of the analysed samples, although the transcript abundance of some genes was very low. 33 BvMYB genes (44%) were expressed in all samples analysed, which suggested that these BvMYBs play regulatory roles at multiple developmental stages. Five genes lacked expression information in any of the analysed samples, possibly indicating that these genes are expressed in other organs (e.g. root, stem), specific cells, at specific developmental stages, under special conditions or being pseudogenes. Some BvMYB genes are expressed in all analysed samples at similar levels (e.g. R2R3-MYB Bv_ohkk and MYB3R-type Bv_tcwd), while other show variance in transcript abundance with high levels in one or several organs and low (no) levels in others. For example, Bv_hwcc, Bv_owzx and Bv_jxgt are expressed in seedlings, taproot, inflorescence and seed, but not in leaves (neither young nor old leaves). Only four BvMYB genes, Bv_oaxt, Bv_ahtj, Bv_zkef and Bv_ijmc, three of them functionally assigned to development, show organ-specific expression and were only detected in inflorescences or seedlings. This result suggests that the corresponding BvMYB regulators are limited to discrete organs, tissues, cells or conditions.

Figure 4.

Hierachical clustered heatmap showing the expression of BvMYB genes in different B. vulgaris (KWS2320) organs . Normalised RNA-seq data was used to generate this heatmap. Expression values are indicated by intensity of yellow colour. Black indicates no detected expression. The hierachical clustering was performed using Cluster 3.0 software; for visualisation Java TreeView was used. Clade assignment of the BvMYBs is given at the right.

Some clustered BvMYB genes (Figure 1), which are often considered as paralogs (created by a duplication event within the genome), showed similar expression profiles, while other clustered BvMYB genes did not. Bv_ahzs and Bv_eztu (both in the development-related clade 26), are mainly expressed in inflorescences and seeds with only low (or no) expression in the other analysed organs. The two clustered genes Bv_dxny and Bv_zguf (both in the defence-related clade 7) showed different expression profiles with Bv_zguf mainly expressed in seedlings and seeds and Bv_dxny further expressed in leaves. These results indicate, that Bv_ahzs and Bv_eztu could be functionally redundant genes, while Bv_dxny and Bv_zguf could be (partly) involved in various aspects of defence processes.

Functional analysis of the R2R3-MYB gene Bv_iogq

In the context of functional analysis we selected Bv_iogq to start with. Bv_iogq is the only BvMYB in clade C13 (S7) clustering together with landmark MYBs having been implicated as flavonol- and phlobaphene-specific activators of flavonoid biosynthesis during plant development. This especially includes the Z. mays factor ZmP, controlling the accumulation of red phlobaphene pigments in pericarps [58], the V. vinifera flavonol regulator VvMYBF1 [59] and the A. thaliana PRODUCTION OF FLAVONOL GLYCOSIDES (PFG) family constituted of AtMYB12/AtPFG1, AtMYB11/AtPFG2 and AtMYB111/AtPFG3 [60]. AtMYB12 was shown to regulate CHALCONE SYNTHASE (CHS) expression by binding the MYB-recognition element MRECHS [61]. The three A. thaliana PFG-family factors were further found to have overlapping functions in flavonol pathway-specific gene regulation but to play organ-specific roles. Concordantly, A. thaliana seedlings of the pfg triple mutant (myb11 myb12 myb111) do not form flavonols under standard growth conditions, whereas the accumulation of other flavonoids is not affected [60].

We tested if Bv_iogq codes for a functional flavonol regulator. The Bv_iogq open reading frame (ORF) encodes a predicted protein with 387 amino acid residues, with a calculated molecular mass of 43.6 kD. Analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence revealed that Bv_iogq contains both motifs which have been described to be characteristic for flavonol regulators. The subgroup S7 motif (GRTxRSxMK) [17] was found to be present in the C-terminus of Bv_iogq with one amino acid substitution (GRTSRWAMQ), and the SG7-2 motif ([W/x][L/x]LS; [59]) was found at the very C-terminal end of Bv_iogq.

Since flavonol glycosides are known to accumulate in B. vulgaris leaves [62,63], and our expression data indicated Bv_iogq to be expressed in young leaves (Figure 4), this organ was chosen as source to clone the cDNA of the putative flavonol biosynthesis regulator Bv_iogq.

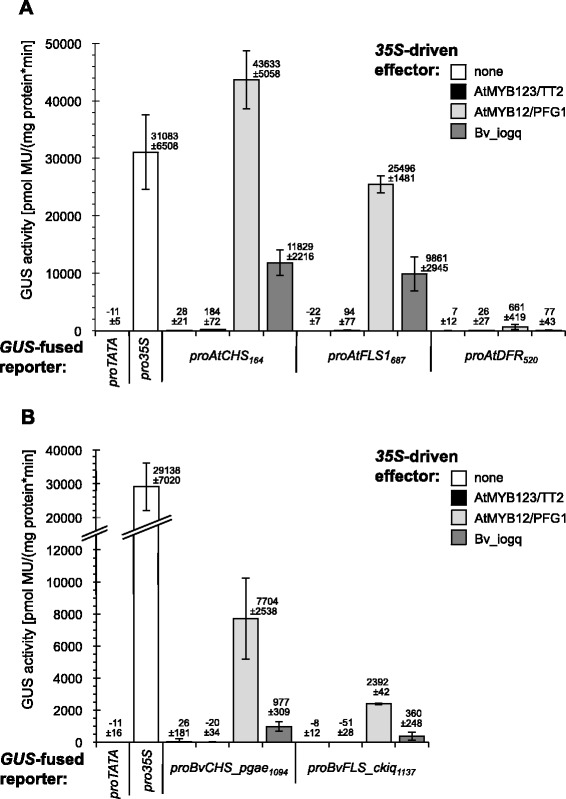

Bv_iogq activates promoters of the flavonoid pathway structural genes

A transient A. thaliana At7 protoplast reporter gene assay system was used to analyse the activation potential of Bv_iogq on promoters of A. thaliana flavonoid biosynthesis enzymes. Figure 5A summarises the results and shows that Bv_iogq is able to activate the promoters of AtCHS, the initial enzyme in the flavonoid pathway, and AtFLAVONOL SYNTHASE1 (AtFLS1), the enzyme catalysing the final step leading to the formation of flavonols. The promoter of the anthocyanidin branch gene AtDIHYDROFLAVONOL REDUCTASE (AtDFR), whose product directly competes with FLS for the same substrate (dihydroflavonols), is not activated by Bv_iogq. In further experiments we tested the potential of Bv_iogq to activate the B. vulgaris CHS_phae and FLS_ckiq promoters in At7 protoplasts. The results of the transfection assays (Figure 5B) show that AtMYB12 activates both tested flavonoid B. vulgaris promoters, even though to a lower extent than the A. thaliana homologs. Furthermore, Bv_iogq is able to activate the promoters of BvCHS_phae and BvFLS_ckiq to some extend. We therefore claim Bv_iogq a functional flavonoid regulator, also in consideration of the heterologous assay system. These results revealed substantial functional similarities between the R2R3-MYB transcription factors AtMYB12 and Bv_iogq, as predicted by structural similarities (Figure 2). AtMYB12 was previously shown to activate a subset of flavonoid pathway genes without the need of a bHLH cofactor [61]. Bv_iogq also lacks the bHLH interaction motif in the R2R3 domain, thereby activating a subset of flavonoid pathway genes without the need of a cofactor (Figure 5), confirming that flavonol synthesis does not depend on bHLH cofactors in A. thaliana and B. vulgaris. The results of the transactivation assay suggest Bv_iogq to be a specific regulator of flavonol biosynthesis potentially regulating the early biosynthesis genes directing flavonoid precursors to flavonol formation in B. vulgaris.

Figure 5.

Co-transfection analysis in At7 protoplasts indicate in vivo regulatory potential of Bv_iogq on A. thaliana and B.vulgaris CHS and FLS promoters. Results from co-transfection experiments in A. thaliana protoplasts. Promoter fragments of the (A) A. thaliana AtCHS, AtFLS1 and AtDFR genes, and (B) B. vulgaris BvCHS_phae and BvFLS_ckiq genes (reporters) were assayed for their responsiveness to the effectors AtMYB12/PFG1, AtMYB123/TT2 and Bv_iogq expressed under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. Subscripted numbers indicate promoter fragment length. The figure shows mean GUS activity resulting from the influence of tested effector proteins on different reporters. Data from a set of four replicates are presented.

Complementation of the flavonol-deficient phenotype of A. thaliana multiple pfg mutant

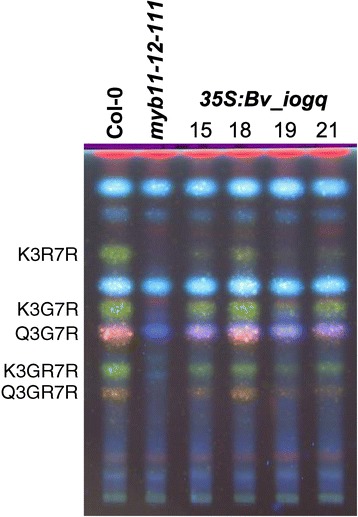

To confirm the function of Bv_iogq as a regulator of flavonol synthesis, the Bv_iogq ORF was expressed under the control of the constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (2x35S:Bv_iogq) in the A. thaliana myb11 myb12 myb111 triple mutant. Whereas seedlings of the mutant showed flavonol-deficient phenotype, several, independent stable transgenic myb11 myb12 myb111::2×35S:Bv_iogq lines showed flavonol accumulation, as visualised by diphenylboric acid-2-aminoethylester (DPBA) staining of high performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) separated flavonols (Figure 6). This result clearly shows that Bv_iogq is able to complement the A. thaliana myb11 myb12 myb111 mutant deficient in flavonol synthesis. Therefore, Bv_iogq from B. vulgaris is a functional R2R3-MYB transcription factor involved in the regulation of flavonol biosynthesis. To indicate this function, we named Bv_iogq according to the A. thaliana ortholog: BvMYB12 (BvPFG1).

Figure 6.

35S:Bv_iogq complements the flavonol-deficient A. thaliana myb11-12-111 mutant. HPTLC of methanolic extracts of T2 seedlings of independent transgenic A. thaliana lines (15, 18, 19, 21) containing T-DNA insertions with a 35S:Bv_iogq construct in the flavonol-deficient myb11-12-111 background. Flavonol glycosides were detected by DPBA staining and visualisation under UV illumination, indicating kaempferol derivatives (green) and quercetin derivatives (orange). K3R7R, kaempferol-3-O-rhamnoside-7-O-rhamnoside; K3G7R, kaempferol-3-O-glucoside-7-O-rhamnoside; Q3G7R, quercetin-3-O-glucoside-7-O-rhamnoside; K3GR7R, kaempferol-3-O- glucorhamnosid-7-O-rhamnoside; Q3GR7R, quercetin-3-O- glucorhamnosid-7-O-rhamnoside.

Conclusions

The genome-wide identification, chromosomal organisation, functional classification and expression analyses of B. vulgaris MYB genes provide an overall insight into this transcription factor-encoding gene family and their potential involvement in growth and development processes. This study provides the first step towards cloning and functional dissection to uncover the role of MYB genes in this economically and evolutionarily interesting species, as representative for the order Caryophyllales. The functional classification was successfully verified by experimental confirmation of the prediction that the R2R3-MYB gene Bv_iogq encodes a flavonol regulator, thus making BvMYB12 the first sugar beet R2R3-MYB with an experimentally proven function.

Methods

Database search for MYB protein coding genes in the B. vulgaris genome

An initial search for MYB protein coding genes in B. vulgaris was performed using a consensus R2R3-MYB DNA binding domain sequence [19] as protein query in TBLASTN [64] searches on the beet genome sequence (RefBeet, http://www.genomforschung.uni-bielefeld.de/en/projects/annobeet). To confirm the obtained amino acid sequences, the putative MYB sequences were manually analysed for the presence of an intact MYB domain. All B. vulgaris MYB proteins were inspected to ensure that the putative gene models contained two or more (multiple) MYB repeats, and that the gene models mapped to unique loci in the genome. Redundant sequences were discarded from the data set to obtain unique BvMYB genes. The identified BvMYB genes were matched with the automatically annotated MYB genes from the study of Dohm et al. ([26]). The open reading frames of the identified BvMYB have been verified by mapping, visualisation and manually inspection of combined RNA-seq data. Additionally, manually identified BvMYB genes received a unique immutable four-letter-ID and a gene code describing the position on pseudochromosomes or unanchored scaffolds. Multiple FASTA files with protein sequences used in this work, CDS and CDSi (CDS plus introns) sequences of BvMYBs are found as Additional files 4, 5 and 6.

Sequence conservation analysis

To analyse the sequence features of the MYB domain of B. vulgaris R2R3-MYB proteins, the sequences of R2 and R3 MYB repeats of 70 BvR2R3-MYB proteins were aligned with ClustalOmega (1.2.0) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) using the default parameters. The sequence logos for R2 and R3 MYB repeats were produced from the multiple alignment files by the web based application WebLogo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi) [65] using default settings.

Phylogenetic analyses

133 A. thaliana MYB protein sequences were obtained from TAIR (http://www.arabidopsis.org/). 51 well-known landmark plant R2R3-MYB protein sequences were collected from GenBank at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). We additionally considered atypical multiple MYB-repeat proteins from A. thaliana in the phylogenetic analysis to determine orthologs in the B. vulgaris genome: AtCDC5, AtMYB4R1 and five AtMYB3R. Phylogenetic trees were constructed from ClustalW aligned full-length MYB proteins (75 BvMYBs, 133 AtMYBs and 51 plant landmark MYBs) using MEGA5.2 [33] with full-length proteins and default settings. Two statistical methods were used for tree generation: (i) neighbor-joining (NJ) method with poison correction and bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates, (ii) maximum parsimony (MP) method with 1000 bootstrap replications. Classification of the B. vulgaris MYBs was performed according to their phylogenetic relationships with their corresponding A. thaliana and landmark MYB proteins.

Expression analysis from RNA-sequencing data

RNA-seq raw data from inflorescences, taproots, old leaves, seeds and seedlings of the B. vulgaris double haploid reference line KWS2320 have been produced in the work of Dohm et al. [26] and are deposited at the NCBI Short Read Archive (SRA) under the accession numbers SRX287608-SRX287615. RNA-seq raw data from RNA isolated from young leaves (third and forth leaf without midrip) have been generated by paired-end sequencing (2× 101 bases) on an Illumina HiSeq1500 instrument and are deposited together with a detailed documentation at the SRA under the accession number SRX647324. Raw RNA-seq reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic-0.22 [66] and the options ILLUMINACLIP, LEADING:3, TRAILING:3, SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 as well as MINLEN:36. For Tophat [67] mappings versus the RefBeet sequence, only trimmed paired reads generated by Trimmomatic-0.22 were used (Additional file 7). For mapping of long read sets (>55 bases read length) and short read sets (≤55 bases read length) the mate inner distance was set to 175 and 150, respectively and the option solexa1.3-quals was switched on. Mapping results are displayed in Additional file 7. Resulting BAM files were quality filtered according a minimum mapping quality of five and converted using SAMtools [68]. SAM files were sorted afterwards (Unix command sort -s -k 1,1). Reads per gene were counted based on manually corrected gene structures stored in gff3 format and the sorted SAM files by htseq-count (option t = CDS) that is part of HTSeq version 0.5.4 (http://www-huber.embl.de/users/anders/HTSeq/doc/overview.html). Single count tables for each organ created by HTSeq were joined using a customised Perl script and subsequently imported in R by means of the DESeq package [69]. Data design, sample assignment and normalisation were performed as described previously [69]. The correction factors of different data sets were computed as 4.02, 1.25, 3.53, 0.11, 1.47, 0.41 for seedling, taproot, young leaf, old leaf, inflorescence and seed, respectively.

Hierachical clustering and heatmap visualisation of RNA-seq data

Centroid-linkage hierachical clustering of log2 transformed normalised RNA-seq data was performed using Cluster 3.0 software [70] (http://bonsai.hgc.jp/~mdehoon/software/cluster/software.htm). The hierachical clustering results were visualised using Java TreeView [71] (http://jtreeview.sourceforge.net).

Plant material and growth conditions

B. vulgaris KWS2320 seeds were surface-sterilised with 70% ethanol and sown on sterile, wet cotton wool in a covered plastic beaker. Seedlings were grown for one week at 22°C giving 16 hours light per day. All other plant material was harvested from greenhouse/soil-grown B. vulgaris plants.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

RNA was isolated from 50 mg plant material using the NucleoSpin®RNA Plant kit (Macherey-Nagel) according to the manufacturers instruction. cDNA was generated from 1 μg total RNA as described previously [60].

cDNA cloning

A cDNA fragment corresponding to the full-length ORF of Bv_iogq (1164 bp) was obtained by PCR using attB recombination sites containing sense RS1050 (5'-attB1-ccATGGGGAGAGCACCGTGTTGCGAAAAG-3') and antisense RS1051 (5'-attB2-gTTATGAAAGTAGCCAATCAAGCATAGC-3') primers with Phusion® polymerase (New England BioLabs) on cDNAs prepared from B. vulgaris KWS2320 young leaves as template. The resulting PCR product was introduced into the GATEWAY® vector pDONRzeo using BP clonase (Invitrogen), giving a Bv_iogq entry clone (RSt810). The Bv_iogq cDNA sequence was submitted to EMBL/GenBank; accession number KJ707238.

Complementation experiments with Bv_iogq

The Bv_iogq entry clone was recombined by LR-reaction (Invitrogen) into the binary destination vector pLEELA [72] giving a 2×35S:Bv_iogq construct (RSt815). The resulting plasmid was used in a complementation experiment transforming the flavonol-deficient A. thaliana triple mutant myb11 myb12 myb111 (NASC N9815) via Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101::pM90RK) [73] according to the floral dip protocol. Flavonol-containing methanolic extracts of T2 seedlings of different transgenic lines were analysed by high performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) and diphenylboric acid 2-aminoethyl ester (DPBA)-staining as described elsewhere [60].

Transient protoplast assays

Growth of A. thaliana At7 cell culture, protoplast isolation and transfection experiments for the detection of transient expression were performed as described by Mehrtens et al. [61]. In the co-transfection experiments, a total of 25 μg of pre-mixed plasmid DNA was transfected, consisting of 10 μg of reporter plasmid (transcriptional GUS fusion), 10 μg of effector plasmid and 5 μg of the luciferase (LUC) transfection control (4xproUBI:LUC) [74]. Protoplasts were incubated for 20 h at 26°C in the dark before LUC and GUS enzyme activities were measured. Specific GUS activity is given in pmol 4-methylumbelliferone (MU) per mg protein per min. The error bars indicate the standard deviation of four GUS values determined for the respective reporter/effector combination. The 35S:Bv_iogq effector plasmid (RSt816) was generated by LR-reaction (Invitrogen) of the Bv_iogq Entry clone (RSt810) with the destination vector pBTdest [75]. A 1064 bp promoter fragment of proBvCHS_phae was obtained by PCR on genomic B. vulgaris KWS2320 DNA using attB recombination sites containing primers BP60 (5'-attB1-CCACAAGAACATCTTGTAAGAGC-3') and BP55 (5'-attB2-CAACTCGTGAGTATGAAGAAATATG-3'). The 1137 bp promoter fragment of proBvFLS_ckiq was gained with the attB primers RS1128 (5'-attB1-TATACCTTGTAATATCACTTAAATCT-3') and RS1129 (5'-attB2-CCATTGAATATCAACTCAGGATTTTC-3'). The resulting PCR products were introduced via BP and LR reactions into the GATEWAY® destination vector pDISCO [76] giving the proBvCHS_phae-GUS (DH33) and proBvFLS_ckiq-GUS (RSt830) reporter constructs. The other effector- and reporter constructs have been described elsewere [13,61,77].

Availability of supporting data

Phylogenetic data (trees and the data used to generate them) have been deposited in TreeBASE respository and is available under the URL http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S16360.

RNA-seq data from inflorescences, taproots, young leaves, old leaves, seeds and seedlings of the B. vulgaris line KWS2320 are deposited at the NCBI Short Read Archive (SRA; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) under the accession numbers SRX287608-SRX287615 and SRX647324.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Melanie Kuhlmann for excellent technical assistance. We thank Sebastian Packheiser who contributed to cloning and plant transformation. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science (BMBF) grant “AnnoBeet: Annotation des Genoms der Zuckerrübe unter Berücksichtigung von Genfunktionen und struktureller Variabilität für Nutzung von Genomdaten in der Pflanzenbiotechnologie" (FKZ 0315962 A). A further "thanks" to our industrial partners KWS Saat AG and Syngenta Seeds GmbH. We acknowledge support for the Article Processing Charge by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Fund of Bielefeld University Library.

Additional files

Multiple alignment of MYB domains of 70 B. vulgaris R2R3-MYB proteins. ClustalW amino acid sequence alignment. The black arrowheads at the top indicate the conserved, regulary spaced tryptophan (W) or phenylalanine (F) residues. Position numbers at the top correspond to those given in Figure 2.

Phylogenetic Maximal Parsimony (MP) tree (1000 bootstraps) with MYB proteins from B. vulgaris (Bv), A. thaliana (At) and landmark MYBs from other plants built with MEGA5.2. Bootstrap measures are given at the branches. Clades (and Subgroups) are labelled and indicated by different shades of grey.

Expression of BvMYB genes in organs of the B. vulgaris reference line KWS2320, deduced from RNA-seq data from the study of Dohm et al. ([ 26 ]). Reads per gene were counted based on BvMYB gene structures. Single count tables for each organ were transformed to normalised data according to the method of Anders and Huber (2010), using correction factors for the different data sets which have been computed as 4.02, 1.25, 3.53, 0.11, 1.47, 0.41 for seedlings, taproot, young leaf, old leaf, inflorescence, seed, respectively.

Multiple FASTA file with protein sequences used in this work.

Multiple FASTA file with CDS sequences of BvMYBs .

Multiple FASTA file with CDSi (CDS plus introns) sequences of BvMYBs .

Trimming and mapping of RNA-seq reads. (A) Trimming of RNA-seq raw reads using Trimmomatic. SRA: Sequence read archive. (B) Mapping of RNA-seq reads to RefBeet after applying Tophat.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RS and BW conceived and designed research. RS and BP conducted experiments. RS, DH, JS and TRS analysed and interpreted the data. RS and BW wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Ralf Stracke, Email: ralf.stracke@uni-bielefeld.de.

Daniela Holtgräwe, Email: dholtgra@cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de.

Jessica Schneider, Email: jschneid@cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de.

Boas Pucker, Email: boas.pucker@uni-bielefeld.de.

Thomas Rosleff Sörensen, Email: rosleff@cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de.

Bernd Weisshaar, Email: bernd.weisshaar@uni-bielefeld.de.

References

- 1.Riechmann JL, Heard J, Martin G, Reuber L, Jiang CZ, Keddie J, Adam L, Pineda O, Ratcliffe OJ, Samaha RR, Creelman R, Pilgrim M, Broun P, Zhang JZ, Ghandehari D, Sherman BK, Yu CL. Arabidopsis transcription factors: Genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science. 2000;290(5499):2105–2110. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubos C, Stracke R, Grotewold E, Weisshaar B, Martin C, Lepiniec L. MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogata K, Kanei-Ishii C, Sasaki M, Hatanaka H, Nagadoi A, Enari M, Nakamura H, Nishimura Y, Ishii S, Sarai A. The cavity in the hydrophobic core of Myb DNA-binding domain is reserved for DNA recognition and trans-activation. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3(2):178–187. doi: 10.1038/nsb0296-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia L, Clegg MT, Jiang T. Evolutionary dynamics of the DNA-binding domains in putative R2R3-MYB genes identified from rice subspecies indica and japonica genomes. Plant Physiol. 2004;134(2):575–585. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.027201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klempnauer KH, Gonda TJ, Bishop JM. Nucleotide sequence of the retroviral leukemia gene v-myb and its cellular progenitor c-myb: the architecture of a transduced oncogene. Cell. 1982;31:453–463. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito M. Conservation and diversification of three-repeat Myb transcription factors in plants. J Plant Res. 2005;118(1):61–69. doi: 10.1007/s10265-005-0192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haga N, Kato K, Murase M, Araki S, Kubo M, Demura T, Suzuki K, Muller I, Voss U, Jurgens G, Ito M. R1R2R3-Myb proteins positively regulate cytokinesis through activation of KNOLLE transcription in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2007;134(6):1101–1110. doi: 10.1242/dev.02801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin H, Martin C. Multifunctionality and diversity within the plant MYB-gene family. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;41(5):577–585. doi: 10.1023/A:1006319732410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosinski JA, Atchley WR. Molecular evolution of the Myb family of transcription factors: evidence for polyphyletic origin. J Mol Evol. 1998;46(1):74–83. doi: 10.1007/PL00006285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun EL, Grotewold E. Newly discovered plant c-myb-like genes rewrite the evolution of the plant myb gene family. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:21–24. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kranz H, Scholz K, Weisshaar B. c-MYB oncogene-like genes encoding three MYB repeats occur in all major plant lineages. Plant J. 2000;21(2):231–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dias AP, Braun EL, McMullen MD, Grotewold E. Recently duplicated maize R2R3 Myb genes provide evidence for distinct mechanisms of evolutionary divergence after duplication. Plant Physiol. 2003;131(2):610–620. doi: 10.1104/pp.012047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmermann IM, Heim MA, Weisshaar B, Uhrig JF. Comprehensive identification of Arabidopsis thaliana MYB transcription factors interacting with R/B-like BHLH proteins. Plant J. 2004;40:22–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song S, Qi T, Huang H, Ren Q, Wu D, Chang C, Peng W, Liu Y, Peng J, Xie D. The Jasmonate-ZIM domain proteins interact with the R2R3-MYB transcription factors MYB21 and MYB24 to affect Jasmonate-regulated stamen development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011;23(3):1000–1013. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.083089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du H, Yang SS, Liang Z, Feng BR, Liu L, Huang YB, Tang YX. Genome-wide analysis of the MYB transcription factor superfamily in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12(106):106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kranz HD, Denekamp M, Greco R, Jin H, Leyva A, Meissner RC, Petroni K, Urzainqui A, Bevan M, Martin C, Smeekens S, Tonelli C, Paz-Ares J, Weisshaar B. Towards functional characterisation of the members of the R2R3-MYB gene family from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:263–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stracke R, Werber M, Weisshaar B. The R2R3-MYB gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;4:447–456. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang C, Gu X, Peterson T. Identification of conserved gene structures and carboxy-terminal motifs in the Myb gene family of Arabidopsis and Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica. Genome Biol. 2004;5(7):R46. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-7-r46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matus JT, Aquea F, Arce-Johnson P: Analysis of the grape MYB R2R3 subfamily reveals expanded wine quality-related clades and conserved gene structure organization across Vitis and Arabidopsis genomes.BMC Plant Biol 2008, 8(83). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Wilkins O, Nahal H, Foong J, Provart NJ, Campbell MM. Expansion and diversification of the Populus R2R3-MYB family of transcription factors. Plant Physiol. 2009;149(2):981–993. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.132795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin C, Paz-Ares J. MYB transcription factors in plants. Trends Genet. 1997;13(2):67–73. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(96)10049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du H, Feng BR, Yang SS, Huang YB, Tang YX. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor gene family in maize. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e37463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanhui C, Xiaoyuan Y, Kun H, Meihua L, Jigang L, Zhaofeng G, Zhiqiang L, Yunfei Z, Xiaoxiao W, Xiaoming Q, Yunping S, Li Z, Xiaohui D, Jingchu L, Xing-Wang D, Zhangliang C, Hongya G, Li-Jia Q. The MYB transcription factor superfamily of Arabidopsis: expression analysis and phylogenetic comparison with the rice MYB family. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;60(1):107–124. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2910-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Q, Zhang C, Li J, Wang L, Ren Z. Genome-wide identification and characterization of R2R3MYB family in Cucumis sativus. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao ZH, Zhang SZ, Wang RK, Zhang RF, Hao YJ. Genome wide analysis of the apple MYB transcription factor family allows the identification of MdoMYB121 gene confering abiotic stress tolerance in plants. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69955. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dohm JC, Minoche AE, Holtgrawe D, Capella-Gutierrez S, Zakrzewski F, Tafer H, Rupp O, Sorensen TR, Stracke R, Reinhardt R, Goesmann A, Kraft T, Schulz B, Stadler PF, Schmidt T, Gabaldon T, Lehrach H, Weisshaar B, Himmelbauer H. The genome of the recently domesticated crop plant sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) Nature. 2014;505(7484):546–549. doi: 10.1038/nature12817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Arabidopsis Genome Initiative Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000;408(6814):796–815. doi: 10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goff SA, Ricke D, Lan T-H, Presting G, Wang R, Dunn M, Glazebrook J, Sessions A, Oeller P, Varma H, Hadley D, Hutchison D, Martin C, Katagiri F, Lange BM, Moughamer T, Xia Y, Budworth P, Zhong J, Miguel T, Paszkowski U, Zhang S, Colbert M, Sun W-l, Chen L, Cooper B, Park S, Wood TC, Mao L, Quail P, et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica) Science. 2002;296(5565):92–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuskan GA, Difazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, Putnam N, Ralph S, Rombauts S, Salamov A, Schein J, Sterck L, Aerts A, Bhalerao RR, Bhalerao RP, Blaudez D, Boerjan W, Brun A, Brunner A, Busov V, Campbell M, Carlson J, Chalot M, Chapman J, Chen GL, Cooper D, Coutinho PM, Couturier J, Covert S, Cronk Q, et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray) Science. 2006;313(5793):1596–1604. doi: 10.1126/science.1128691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmutz J, Cannon SB, Schlueter J, Ma J, Mitros T, Nelson W, Hyten DL, Song Q, Thelen JJ, Cheng J, Xu D, Hellsten U, May GD, Yu Y, Sakurai T, Umezawa T, Bhattacharyya MK, Sandhu D, Valliyodan B, Lindquist E, Peto M, Grant D, Shu S, Goodstein D, Barry K, Futrell-Griggs M, Abernathy B, Du J, Tian Z, Zhu L, et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature. 2010;463(7278):178–183. doi: 10.1038/nature08670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velasco R, Zharkikh A, Affourtit J, Dhingra A, Cestaro A, Kalyanaraman A, Fontana P, Bhatnagar SK, Troggio M, Pruss D, Salvi S, Pindo M, Baldi P, Castelletti S, Cavaiuolo M, Coppola G, Costa F, Cova V, Dal Ri A, Goremykin V, Komjanc M, Longhi S, Magnago P, Malacarne G, Malnoy M, Micheletti D, Moretto M, Perazzolli M, Si-Ammour A, Vezzulli S, et al. The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus x domestica Borkh.) Nature Genetics. 2010;42(10):833–839. doi: 10.1038/ng.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dohm JC, Lange C, Holtgräwe D, Sörensen TR, Borchardt D, Schulz B, Lehrach H, Weisshaar B, Himmelbauer H. Palaeohexaploid ancestry for Caryophyllales inferred from extensive gene-based physical and genetic mapping of the sugar beet genome (Beta vulgaris) Plant J. 2012;70(3):528–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Celenza JL, Quiel JA, Smolen GA, Merrikh H, Silvestro AR, Normanly J, Bender J. The Arabidopsis ATR1 Myb transcription factor controls indolic glucosinolate homeostasis. Plant Physiol. 2005;137(1):253–262. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.054395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sonderby IE, Hansen BG, Bjarnholt N, Ticconi C, Halkier BA, Kliebenstein DJ. A systems biology approach identifies a R2R3 MYB gene subfamily with distinct and overlapping functions in regulation of aliphatic glucosinolates. PLoS One. 2007;2(12):e1322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gigolashvili T, Berger B, Mock HP, Muller C, Weisshaar B, Flugge UI. The transcription factor HIG1/MYB51 regulates indolic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2007;50(5):886–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gigolashvili T, Engqvist M, Yatusevich R, Muller C, Flugge UI. HAG2/MYB76 and HAG3/MYB29 exert a specific and coordinated control on the regulation of aliphatic glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2008;177(3):627–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oppenheimer DG, Herman PL, Sivakumaran S, Esch J, Marks MD. A myb gene required for leaf trichome differentiation in Arabidopsis is expressed in stipules. Cell. 1991;67:483–493. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee MM, Schiefelbein J. WEREWOLF, a MYB-related protein in Arabidopsis, is a position-dependent regulator of epidermal cell patterning. Cell. 1999;24(5):473–483. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81536-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirik V, Lee MM, Wester K, Herrmann U, Zheng Z, Oppenheimer D, Schiefelbein J, Hulskamp M. Functional diversification of MYB23 and GL1 genes in trichome morphogenesis and initiation. Development. 2005;132(7):1477–1485. doi: 10.1242/dev.01708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serna L, Martin C. Trichomes: different regulatory networks lead to convergent structures. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11(6):274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brockington SF, Alvarez-Fernandez R, Landis JB, Alcorn K, Walker RH, Thomas MM, Hileman LC, Glover BJ. Evolutionary analysis of the MIXTA gene family highlights potential targets for the study of cellular differentiation. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(3):526–540. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perez-Rodriguez M, Jaffe FW, Butelli E, Glover BJ, Martin C. Development of three different cell types is associated with the activity of a specific MYB transcription factor in the ventral petal of Antirrhinum majus flowers. Development. 2005;132(2):359–370. doi: 10.1242/dev.01584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quattrocchio F, Wing J, van der Woude K, Souer E, De Vetten N, Mol J, Koes R. Molecular analysis of the anthocyanin2 gene of Petunia and its role in the evolution of flower color. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1433–1444. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.8.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borevitz JO, Xia YJ, Blount J, Dixon RA, Lamb C. Activation tagging identifies a conserved MYB regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2000;12(12):2383–2393. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwinn K, Venail J, Shang Y, Mackay S, Alm V, Butelli E, Oyama R, Bailey P, Davies K, Martin C. A small family of MYB-regulatory genes controls floral pigmentation intensity and patterning in the genus Antirrhinum. Plant Cell. 2006;18(4):831–851. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez A, Zhao M, Leavitt JM, Lloyd AM. Regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway by the TTG1/bHLH/Myb transcriptional complex in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant J. 2008;53(5):814–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kimler L, Mears J, Mabry TJ, Rösler H. On the question of the mutual exclusiveness of batalains and anthocyanins. Taxon. 1970;19(6):875–878. doi: 10.2307/1218301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt OT, Schönleben W. Zur Kenntnis der Farbstoffe der Roten Rübe, II. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung. 1957;12b:262–263. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stafford HA. Anthocyanins and betalains: evolution of the mutually exclusive pathways. Plant Sci. 1994;101:91–98. doi: 10.1016/0168-9452(94)90244-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keller W. Inheritance of some major color types in beets. J Agric Res. 1936;52:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldman IL, Austin D. Linkage among the R, Y and BI loci in table beet. Theor Appl Genet. 2000;100:337–343. doi: 10.1007/s001220050044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hatlestad GJ, Sunnadeniya RM, Akhavan NA, Gonzalez A, Goldman IL, McGrath JM, Lloyd AM. The beet R locus encodes a new cytochrome P450 required for red betalain production. Nat Genet. 2012;44(7):816–820. doi: 10.1038/ng.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Christinet L, Burdet FX, Zaiko M, Hinz UZ, Zrÿd JP. Characterization and functional identification of a novel plant 4,5-extradiol dioxygenase involved in betalain pigment biosynthesis in Portulaca grandiflora. Plant Physiol. 2004;134(1):265–274. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.031914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heppel SC, Jaffé FW, Takos AM, Schellmann S, Rausch T, Walker AR, Bogs J. Identification of key amino acids for the evolution of promoter target specificity of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin regulating MYB factors. Plant Mol Biol. 2013;82(4–5):457–471. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aharoni A, De Vos CHR, Wein M, Sun Z, Greco R, Kroon A, Mol JNM, O'Connell AP. The strawberry FaMYB1 transcription factor suppresses anthocyanin and flavonol accumulation in transgenic tobacco. Plant J. 2001;28(3):319–332. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deluc L, Barrieu F, Marchive C, Lauvergeat V, Decendit A, Richard T, Carde JP, Merillon JM, Hamdi S. Characterization of a grapevine R2R3-MYB transcription factor that regulates the phenylpropanoid pathway. Plant Physiol. 2006;140(2):499–511. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.067231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grotewold E, Drummond BJ, Bowen B, Peterson T. The myb-homologous P gene controls phlobaphene pigmentation in maize floral organs by directly activating a flavonoid biosynthetic gene subset. Cell. 1994;76(3):543–553. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Czemmel S, Stracke R, Weisshaar B, Cordon N, Harris NN, Walker AR, Robinson SP, Bogs J. The grapevine R2R3-MYB transcription factor VvMYBF1 regulates flavonol synthesis in developing grape berries. Plant Physiol. 2009;151(3):1513–1530. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.142059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stracke R, Ishihara H, Huep G, Barsch A, Mehrtens F, Niehaus K, Weisshaar B. Differential regulation of closely related R2R3-MYB transcription factors controls flavonol accumulation in different parts of the Arabidopsis thaliana seedling. Plant J. 2007;50(4):660–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mehrtens F, Kranz H, Bednarek P, Weisshaar B. The Arabidopsis transcription factor MYB12 is a flavonol-specific regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2005;138(2):1083–1096. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.058032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gardner RL, Kerst AF, Wilson DM, Payne MG. Beta vulgaris L.: The characterization of three polyphenols isolated from the leaves. Phytochemistry. 1967;6:417–422. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)86299-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]