Abstract

Purpose

In order to develop a theoretical framework for person-centered care models for children with epilepsy and their parents, we conducted a qualitative study to explore and understand parents’ needs, values, and preferences to ultimately reduce barriers that may be impeding parents from accessing and obtaining help for the child’s co-occurring problems.

Methods

A qualitative grounded theory study design was utilized to understand parents’ perspectives. The participants were 22 parents of children with epilepsy who ranged in age from 31-53 years. Interviews were conducted using open ended semi-structured questions to facilitate conversation. Transcripts were analyzed using grounded theory guidelines.

Results

In order to understand the different perspectives parents had about their child, we devised a theory composed of three zones (Zones 1, 2, 3) that can be used to conceptualize parents’ viewpoints. Zone location was based on parents’ perspectives of their child’s comorbidities in the context of epilepsy. These zones were developed to help identify distinctions between parents’ perspectives and to provide a framework within which to understand parents’ readiness to access and implement interventions to address the child’s struggles. These zones of understanding describe parents’ perspectives of their child’s struggles at a particular point in time. This is the perspective from which parents address their child’s needs. This theoretical perspective provides a structure in which to discuss parents’ perspectives on conceptualizing or comprehending the child’s struggles in the context of epilepsy. The zones are based on how the parents a) describe their concerns about the child’s struggles, b) their understanding of the struggles, and c) the parent’s view of the child’s future.

Conclusions

Clinicians working with individuals and families with epilepsy are aware that epilepsy is a complex and unpredictable disorder. The zones help clinicians conceptualize and build a framework within which to understand how parents view their child’s struggles, which influences the parents’ ability to understand and act on clinician feedback and recommendations. Zones allow for increased understanding of the parent at a particular time and provide a structure within which a clinician can provide guidance and feedback to meet parents’ needs, values and preferences. This theory allows clinicians to meet the parents where they are and address their needs in a way that benefits the parents, family and child.

Keywords: pediatric epilepsy, parents, person-centered care, qualitative study

1. Introduction

Many parents, who have a child with epilepsy, willingly provide stories of daily struggles. When queried, parents often discuss how they are adjusting to the diagnosis of epilepsy in their child. When the seizures are reduced by medications, parents are grateful for good seizure control. However, parents continue to report ongoing struggles related to learning problems, social difficulties, attention problems, organizational problems, irritability, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. In a study of children with recent onset epilepsy, rates of Axis I disorders were reported as high as 69% [1]. Additionally, a number of studies have shown that when a child with epilepsy has a co-occurring condition like anxiety, depression, ADHD, or an intellectual disability parents experience higher rates of stress [2-6]. Importantly, parents frequently report that they are unable to access the appropriate services or are unable to receive guidance regarding the child’s co-occurring problems. Parents are often dismayed and seem at a loss regarding what steps to take to address problems [7].

As part of a recent pilot intervention study designed to address some of the problems parents were reporting [8], it was unexpectedly difficult to recruit for the study, and this recruitment problem was in significant contrast to the request for assistance that had been put forth when talking with parents prior to study implementation. We were puzzled by this difficulty because parents were asking for assistance and guidance, but surprisingly few parents were taking advantage of an opportunity to get help. We looked to the literature to provide insight into what we were experiencing. Wu et al. [9] indicated that parents were well aware of their child’s co-occurring behavior problems, but only 1/3 of children received treatment for the comorbid conditions [10]. Roeder et al. [11] reported a similar experience where parents were informed of their child’s diagnosis of depression, but only a third of those children received treatment. It appeared as though there was a disconnection between parents describing the child’s problems and accessing help to address those problems. Research creates its own barriers to participation, but the nonresponses we were experiencing appeared incongruent compared to what parents were reporting as struggles and their repeated requests for help.

As is well documented, epilepsy is commonly accompanied by psychological, cognitive, social and physical complications. It is important for clinicians to provide information and assistance to the individual and family that will promote well-being and enhance quality of life [12]. As a result, it is important for individuals with epilepsy and families to have patient-centered care that has a coordinated and comprehensive approach to meet the needs of each person and family [12]. Patient-centered care is often defined as care that addresses the needs, preferences and values of the individual and family. The IOM report [12] also challenged clinicians to provide individuals and families with appropriate and accurate information regarding the co-occurring problems that frequently accompany epilepsy. Additionally, it is important that clinicians provide information to individuals and families that is approachable and understandable. However, very little information is available regarding how clinicians can begin to develop patient-centered approaches to meet the individual needs and values of each family. How do clinicians conceptualize and understand the needs, values, and preferences of a family? Are there any tools that can assist a clinician in the process? What can parents tell us to help us understand their needs and perspectives?

In order to develop a framework for person -centered care models for children with epilepsy and their parents, we conducted a qualitative study [13] to explore and understand parents’ needs, values, and preferences to ultimately reduce barriers that may be impeding parents from accessing and obtaining help for the child’s co-occurring problems. This study aimed to develop a theoretical framework to aide clinicians and researchers to more effectively work with parents to address the child’s needs, utilizing a person-and family-centered care model.

2. Methods

2.1 Data Analysis

We utilized a grounded theory approach to analyze the relationship between concepts as related to parents understanding of epilepsy in the context of their child [14]. Grounded theory was utilized because little is known about the interview results, and we wished to avoid restricting ourselves to current hypotheses or inferences from prior knowledge or studies. The research team coded the data, and the team consisted of six researchers, which included the 2 interviewers, as well as a qualitative study research facilitator (MKT). Transcripts were coded across incidents, allowing us to see how seemingly dissimilar events shared a common core. As part of the deductive process and to verify our substantive coding, we looked at the problem as it was conceptualized by the parents. For example, we looked at all incidents related to how the parents grappled with the struggles. Our research team compared the data constantly modifying and sharpening the growing understanding of the parents’ concerns. As we progressed, axial coding was used by putting the first group of 10 transcripts into categories to examine emerging ways parents conceptualized their concerns. During the selective coding process, we sought to identify the core explanation for the parents’ behavior in resolving what they thought was the main concern about the child. After identifying the core categories, we theoretically sampled the rest of the dataset ensuring our connections between parents’ concerns continued to make sense in the emerging hypothesis. Our aim was not for the “absolute truth” but rather trying to conceptualize what was occurring from the parental perspectives. Theoretical codes emerged from constantly comparing the data across field notes and memos; we integrated fractured concepts into a hypothesis that worked to explain the main concerns of the participants [14]. Memos assisted the research team in theorizing the write up of ideas that came from our substantive and theoretical coding. Our team used memoing to analyze data and to look at the relationship of ideas, and how these concepts compared across categories to ensure our hypothesis was more than just a superficial understanding of the parents’ main concerns.

Theoretical sampling was utilized to analyze the data in order to produce a theory. We coded the first half of the data and sampled the second portion of the dataset to determine if the coding structure was maintained. In terms of saturation, our main goal was to gather enough data until no new categories were emerging within the theory. Our goal focused on the amount of descriptive data more than on the number of people to recruit and was saturated once we started connecting the theoretical model to our qualitative methodologies. This included ethnographic field notes, memos across team members and discussions over an 18 month period with a variety of clinicians working in the field including senior experts in epilepsy to scrutinize our theoretical model to ensure we had reached saturation.

Triangulation was utilized to increase the reliability of the data by using investigator triangulation. We had investigators from different disciplines including an epilepsy clinician-researcher (JEJ), pediatric neuropsychological clinician (AKJ), and a secondary and post-secondary educator (MKT) that served as evaluators. Additionally, experts in the field of epilepsy, psychiatry, education, and psychology were utilized in the peer debriefing process in order to enhance the validity of the emerging grounded theory. An iterative process was used in order to ensure that parents’ perspectives were not placed in stages, hierarchies, or on a continuum. We examined many theoretical models outside the field of epilepsy to ensure that our emerging theory was additive and distinctive in nature in explaining parents’ understanding. Reflexivity was utilized throughout the research process. Pre-conceptions and assumptions were continually discussed as part of the formulation process. Memo writing was part of our reflexive process allowing for analytical insight to help the research team have purposeful conversations around the emerging theory [15].

2.2 Interview

Research approval was obtained from the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. Written informed consent was obtained from the parent participants.

Parents were interviewed by research assistants who were unfamiliar with the participants from the intervention pilot study that served as a pool from which participants were recruited. The open ended semi-structured interview questions were written especially for this study and questions were utilized to facilitate discussion (Appendix A). We started with semi-structured interviews and refined our methods to focus in on the landscape of what parents were sharing with us including observational notes, clinical reports, ethnographic field notes and team discussions [15]. Every attempt was made to make the questions as neutral as possible, and language labeling the child’s behavior as negative or problematic was intentionally avoided (e.g., “Tell me about your child” and “Do you have any concerns about your child?”). Interviews were between 45 and 120 minutes in length. We conducted 22 individual interviews with 11 parents who participated in the intervention pilot study [8] and 11 parents who were contacted for recruitment into the intervention pilot study but did not participate in the pilot study. Seventeen interviews were conducted in person and three were conducted over the phone. Two interviews were conducted but accidentally deleted. One interview was removed from the sample because the child was in college and outside the age range of the other children.

All interviews were transcribed by individuals who were naive to the study. All quotes utilized in the Results section have been de-identified and any potentially identifying information has been deleted from quotes. All of the children’s names utilized in the Results were picked at random and have no connection to the child’s true identity.

3. Results

3.1 Demographics

There were no significant differences between the parents based on age and education (Table 1). Participants were 17 mothers and 5 fathers who ranged in age from 31 and 53 (M = 40.5, SD = 6.4). Most parents had more than a high school education (n= 19; 86%) with 10 having some college education and 9 having a college degree or graduate education. Their children ranged in age between 9 and 18 years with a mean age of 12.52 (SD = 2.5). There were 11 girls and 11 boys. All the children had epilepsy and were diagnosed and followed in a tertiary care center by pediatric neurologists. All children were currently well controlled with 1 to several seizures (less frequent than monthly) per year (Table 2). Fourteen (64%) of the children had generalized seizures and 8 (36%) had focal seizures. Most of the children were taking one medication (64%). Five (23%) children were not on medication, and 3 (13%) children were taking more than one medication. The average number of years since receiving their epilepsy diagnosis was 5.57 years (SD = 3.36).

Table 1.

Parent Demographics

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 17 | 77.27% |

| Male | 5 | 22.73% | |

| Race | Asian | 1 | 4.55% |

| Black/African American | 1 | 4.55% | |

| White | 19 | 86.36% | |

| More than one race | 1 | 4.55% | |

| Education | Less than high school | 1 | 4.55% |

| High school | 2 | 9.1% | |

| Associate’s Degree/Trade School | 5 | 22.73% | |

| Some college | 5 | 22.73% | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 5 | 22.73% | |

| Master’s Degree | 4 | 18.18% | |

| Marital Status | Married | 16 | 72.73% |

| Divorced | 3 | 13.64% | |

| Widowed | 1 | 4.55% | |

| Cohabitating | 2 | 9.1% | |

| Community Size | Urban | 3 | 13.64% |

| Suburban | 4 | 18.18% | |

| Rural | 15 | 68.18% | |

| Health Insurance | Private, Employer Supported | 13 | 59.1% |

| Public, State Supported | 9 | 40.9% | |

Table 2.

Child Demographics

| Mean | (SD) | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 12.52 | 2.5 | |||

| Gender | Males | 11 | 50% | ||

| Females | 11 | 50% | |||

| Epilepsy | Focal Seizures | 8 | 36.4% | ||

| Generalized Seizures | 14 | 63.6% | |||

| One Medication | 14 | 63.6% | |||

| Years since Diagnosis | 5.57 | 3.36 | |||

Interestingly, parents in all three zones were participants in the pilot study. However, the distribution was not equal across zones (Zone 1: 2 = pilot study and 4 = not in pilot study; Zone 2: 4 = pilot study and 4 = not in pilot study; Zone 3: 5 = pilot study and 0 = not in pilot study). It should be noted that during the analysis of the transcripts, participation in the pilot study was not considered or accounted for during the grounded theory iterative process. In fact, the primary coders were not part of the pilot study.

3.1 Zones of Understanding

All parents described their concerns for their child’s struggles. It was clear that all parents knew their child very well and could describe the child’s strengths and weaknesses in detail. Each parent was interested in improving the quality of all aspects of the child’s life. Parents described significant sacrifices that were made often by the entire family. All expressed a willingness to do whatever was necessary to help their child. It also became clear that parents had variable levels of understanding of their child’s struggles, and their attempts to address their child’s challenges had variable levels of success.

In order to understand the different perspectives parents had about their child, we devised three descriptive zones (Zones 1, 2, 3) in which to conceptualize parents’ viewpoints. These zones were developed to help identify distinctions between parents’ perspectives and to provide a framework within which to understand parents’ readiness to access information and implement interventions to address the child’s struggles. Zones were not designed to pejoratively label parents in any way, but rather to provide insight for clinicians to address individual family needs in a person- or family-centered care model.

Data from this study led us to conclude that parents inhabit zones of understanding. These zones describe parents’ perspectives of their child’s struggles at a particular point in time. This is the perspective from which parents address their child’s needs or help their child. Although there are a number of overlapping features found across zones, there are distinctive characteristics unique to parents in each zone.

For the purposes of this study, zone location was based on parents’ perspectives of their child’s comorbidities in the context of epilepsy. The zones provide a structure in which to discuss parents’ perspectives on conceptualizing or comprehending the child’s struggles in the context of epilepsy. In the following paragraphs we will describe three zones and share vignettes that portray themes commonly expressed by parents in each zone. The zone location is based on how the parents describe: a) their concerns about the child’s struggles, b) their understanding of the struggles, and c) the parent’s view of the child’s future.

3.1. 1 Zone 1

Parents in Zone 1 are acutely aware of the child’s struggles, and they are able to describe them in specific detail. However, parents in Zone 1 often do not label the struggles as a problem. Parents’ understanding of the struggles are characterized by seeking out every day explanations to normalize the child’s behavior or parents may go to significant lengths to accommodate or adapt the environment or family to the child’s issue or struggle. When thinking about the future, parents’ comments often reflected a desire and hope that the struggles would go away or they would get better over time, which led to a passive conceptualization of their own role in changing the outcomes related to the child’s future. Seeking professional assistance is difficult for parents in Zone 1 because parents are less likely to initiate a conversation about the behavior, or parents want a quick fix to the problem. Parents follow clinical recommendations, but often do so in a passive manner with the hopes that this will result in a quick resolution or the disappearance of the problem.

For example, Liz is a ten year old girl with a seven year history of generalized seizures currently well controlled on valproic acid with one or two breakthrough seizures per year. She is doing well academically. However, she has significant symptoms related to depression that impact her functional ability to maintain friendships and family relationships. Mom describes the severity of her depressive symptoms and expresses concern about these symptoms: “[Liz] takes on all the emotions of a situation and feels like she can’t breathe. And she wants to die. And it’s very worrisome because you can feel that she wants to die. She’s told me mom, “I want to die, I want to die.”

When discussing where Mom believes the depressive symptoms originate she indicates that seizures are a potential cause. While there are indicators that there is a relationship between epilepsy and depression, Liz’s mom hopes that if the seizures resolve so too will the depression: “We pray and hope and pray and just cross our fingers that she doesn’t have another seizure. Because we feel in the back of our minds that if she gets off the valproic acid and if she out grows these seizures, we feel we are going to see a change. That Liz is going to release this emotional burden that she’s carrying.” Mom currently has a narrowly focused understanding of her child’s struggle with depressive symptoms stating, “We find that if we have something for Liz to look forward to she feels better. And so hugging helps. Getting her mind off things. Sometimes if we tell funny stories, that helps. Cause we don’t know how to help her and what we’ve tried hasn’t worked.” This quote implies an underestimation and normalization of the severity of Liz’s depressive symptoms by describing responses appropriate for a child with brief episodes of sadness.

3.1.2 Zone 2

By contrast, parents in Zone 2 were consistently more likely to label the child’s struggles as problematic, and as a result, seek out and respond more actively to identify interventions. Parents in Zone 2 demonstrate awareness that the struggles are more permanent and will not resolve without assistance. However, the interventions may be short term or unfocused due to the fact that the parents in Zone 2 are more reactive to the current problem of the day and lack a long term view as part of the problem solving process.

Christopher is a 15 year old boy with seizures that began in the third grade with a remission period of one year, and he was recently restarted on seizure medication due to recurrence. Christopher also has a number of other conditions including a sleep disorder, anxiety disorder, and mild intellectual disability. Dad provides many examples of executive dysfunction and academic issues present before seizure onset. When reflecting on Christopher’s disabilities and struggles, Dad appears to incorporate these problems into his understanding of his child when he indicates, “That’s just Christopher. That’s all.” Dad also reports a plethora of examples of ways in which the parents and school attempted to address these problems. However, there are ongoing issues with academics despite all of the formal services and parent involvement: “He does struggle with organizational skills and he gets work done [but] a lot of times he doesn’t even turn it in. He forgets to or lays it aside and forgets where he puts it. I guess that’s been the biggest struggle.”

These issues are longstanding and parents worked extensively with the school to address them as depicted in the following quote: “There’s nothing more really that we can do that I can see to bring his grades up. He has everything in place, he has great modifications, one on one help. He has after school tutoring. What more can you do? There’s nothing more really available for him.” In spite of the fact that there are numerous interventions, they do not appear to be addressing any long term goals for a child with mild intellectual disability and lack direction. “I think he’s been as successful as he can be in a school setting…and I don’t know what more we would do to keep him in a regular ed[ucation] classroom. I don’t know what more we’d do to help him be more successful at school. I really don’t have any idea.” This example portrays a parent’s frustration after working diligently to arrange services for his child, but unfortunately, without a long term goal or a future focus, the interventions may be misaligned.

3.1.3 Zone 3

Parents in Zone 3 are able to describe the child’s struggles in great detail and are able to conceptualize the struggles as problematic requiring intervention. Parents access interventions in a more solution focused manner while attempting to address short term and long term goals simultaneously. Parents have a proactive and future focused perspective allowing them to address multiple goals across more than one domain or environment. Parents in Zone 3 demonstrated awareness that action must be taken in order for success to occur in the future. Rather than being reactive, they are proactively working to improve circumstances for the child now and in the long-term.

Clara is currently in seventh grade and only recently qualified for special education services to address her ADHD. She has had problems with inattention and hyperactivity since kindergarten.

Her seizures were diagnosed in second grade after a teacher noticed staring episodes. She has absence seizures with periodic tonic-clonic seizures that are well controlled on medications. Like many children with ADHD, Clara has difficulty interacting with peers and siblings. As typified by parents in Zone 3, Clara’s mother identified and conceptualized her daughter’s problems early and requested assistance as is clearly demonstrated in the following quote: “I remember very vividly having a conversation even with her kindergarten teacher about…a referral for special ed[ucation]. Because there’s just something going on.”

After battling with the school for nearly 7 years to obtain services for her daughter, Mom is concerned about future supports in high school, “I don’t foresee Clara being really successful in a high school environment, and so I’m very worried. [She is] still in middle school; it’s still easier to provide services in that setting.” Additionally, mom is concerned about Clara’s low self-esteem because “Clara says she’s not smart enough to go to college…and she thinks because she gets extra help in school that she is not smart.”

In addition to working to keep her daughter seizure free, Mom is actively teaching her daughter how to manage and cope with her ADHD symptoms by implementing a behavioral modification program in order to prepare her for adulthood. Simultaneously, mom is working to help Clara become successful in all of her academic endeavors as demonstrated in this quote: “for me her career right now is being a student and being successful and that’s the foundation for adulthood…That was the biggest thing for me to put my heart and soul into is to get her help in the schools.”

3.1.4 Looking across Zones

Despite the distinct differences observed between zones, there were many similarities that were seen across zones. All the parents in this study could describe their child’s strengths and weaknesses in great detail. They all worked to improve the lives of their children and made significant sacrifices to that end. Each parent interviewed was an advocate for their child, and each asked for some level of assistance or guidance. It is important to note that these factors do not differentiate parents into zones.

Numerous comorbidities were represented in each zone including anxiety, depression, ADHD, autism, intellectual disability, and learning disability.

There were many other factors that did not predict placement in a particular zone, including child’s age, parents’ age, age of seizure onset, degree of seizure control, medication, parent education level, child’s academic success, or parent’s marital status. The intuitive notion that parents who had been coping with their child’s epilepsy for a longer period of time would have greater acceptance and understanding of the disorder did not hold true.

3.1.5 Nuances of Zones

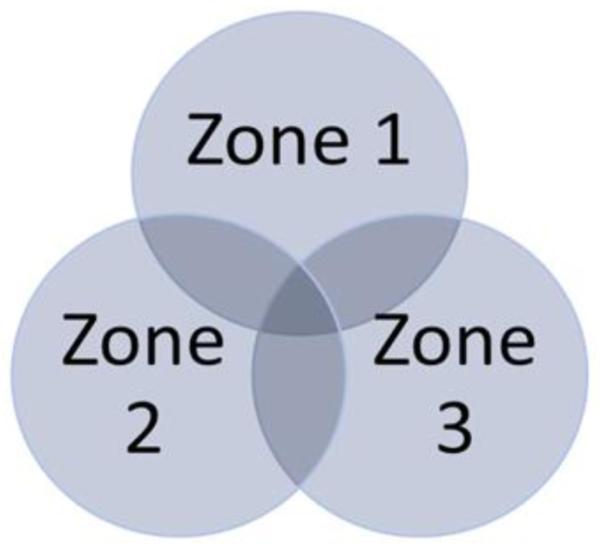

As demonstrated in (Figure 1), parents can inhabit more than one zone at a time. This typically occurs when a parent is in a zone about one problem and inhabits another zone when it comes to coping with a different problem the child is experiencing. For instance, Richard’s seizures were difficult to control when they first appeared at age 4. Due to family circumstances, Richard visited a number of medical centers before his seizures were correctly treated. This required an extraordinary effort on the part of his mother. Like many parents in Zone 3, she was goal directed and actively worked to reach the ultimate outcome of a correct diagnosis and seizure control. However, when it comes to Richard’s cognitive difficulties, his mother falls into Zone 1 when she expresses a wish “for him to start seeing the big picture and doing [it] himself” despite the fact that he received a diagnosis of autism and has an intellectual disability and is unable to complete most activities without supervision. When parents inhabit different zones for different problems this can lead to confusion and misunderstanding among clinicians, particularly when a parent expresses Zone 3 responses for the primary medical condition but has significant difficulty coping with the co-occurring problems associated with epilepsy.

Figure 1.

Zones of Understanding

This Venn diagram illustrates that parents may be in different Zones for different clinical issues. For example, a parent can be in Zone 3 for the child’s epilepsy, but may also be in Zone 1 for the child’s comorbid depression.

Finally, zones can be somewhat permeable depending on life stressors and parents’ coping mechanisms, meaning that parents may move between zones depending on other factors in their lives. For example, we also identified parents who moved from Zone 2 to Zone 1 due to life stressors like divorce. It was apparent that movement from one zone to another was likely related to additional psychosocial stressors for the parent.

4. Discussion

There will always be multiple concerns that parents will need to juggle, and this is especially true for parents of children with epilepsy. Parents are concerned about their child’s seizures, and the co-existing behavior, emotional, or learning difficulties that their child is experiencing. Clinicians are acutely aware that parents are the gatekeepers for initiating and sustaining interventions to address issues. Any experienced clinician has seen parents that are ready to follow through with clinical recommendations, integrate clinician feedback into their understanding of their child, and incorporate suggestions into daily life, as well as parents who are less able to do so.

We developed the zone theory to help clinicians conceptualize and build a framework within which to understand how parents view their child’s struggles, which influences their ability to hear, understand and act on clinician feedback and recommendations. Labels such as stage or levels were intentionally avoided to reduce the possibility of implying a fixed hierarchy or developmental process that parents must proceed through before any change can be made or help is accessed. We felt that the term zone provided a description of a potentially variable and plastic process within which parents’ levels of understanding change overtime as part of life circumstances.

4.1 Clinical Implications of Zones

Zones allow for increased understanding of the parent at a particular time and provide a structure within which a clinician can provide guidance and feedback to a parent. This allows the clinician to meet the parent where they are and address their needs in a way that benefits the parent and child. It is common for clinicians to have strong emotional reactions when their recommendations are not followed; using zones to understand how parents view their child’s struggles will help clinicians manage their own frustration or disappointment with parents’ responses, and instead conceptualize this as a parent addressing the child’s needs to the best of their current level of understanding.

Any clinician working with individuals with epilepsy is aware that this is a complex and unpredictable disorder. Clinicians can use these zones to help prioritize and focus on the issue with the highest potential to be beneficial to the child and family. For example, if a parent believes seizures are the root cause of their child’s problems, they may be less likely to follow through with recommendations that are not directly linked to seizure control.

It is important to note that all parents need some degree of help, assistance, and guidance from their clinicians, regardless of the child’s health issues, no matter how savvy or educated the parent is, or how “put together” the parent appears. These zones can help clinicians anticipate what may be concerning to a parent given the zone they currently occupy for a particular problem. For example, a parent in Zone 3 may feel their child’s daily struggles are well managed, but may nonetheless need reassurance about the future or have questions about long-term implications of their child’s condition or treatments.

Although seeking and maintaining control of seizures is of utmost importance, the severity of the child’s epilepsy is not always the largest issue for the child and family. Parents’ concerns do not dissipate when the seizures are well controlled; on the contrary, this is often when the focus can shift to the surrounding comorbid concerns. In addition, parents may continue to worry about seizure recurrence and worry about how a future seizure will impact the child.

All parents were able to describe their child’s behaviors in great detail, but not all parents conceptualized those behaviors as concerning. It is important for clinicians to understand that a parent’s ability to describe symptoms of clinical conditions does not necessarily mean that the parent understands the clinical implications of those symptoms. For example, we met a few parents that described classic symptom presentations of anxiety and depressive disorders, yet did not conceptualize their children as having depression or anxiety. They were reluctant to use the label, and had many questions indicating that they felt their children’s “symptoms” were age appropriate or within normal limits.

We have devised Table 3 to provide clinicians with pertinent examples of parents in a particular zone for common areas of concern in children with epilepsy to help clinicians identify parents in particular zones in order to modify discussions in a person- and family-centered manner.

Table 3.

Zone Descriptions

| ZONE 1 | ZONE 2 | ZONE 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEIZURES | View seizures as the cause and solution to co-occurring psychiatric, cognitive, and social problems. |

Seizures are seen as a part of the child that complicates cooccurring problems but does not account for them. |

Seizures are one of many complex issues the child has. |

| COMORBID SYMPTOMS OR PROBLEMS |

Normalizes psychiatric, cognitive, social difficulties and problematic behaviors. |

Able to identify psychiatric, cognitive and social difficulties as problematic requiring attention. |

Able to identify psychiatric, cognitive and social problematic behaviors as creating difficulties and implications on multiple aspects of the child’s life. |

| INTERVENTIONS | Accommodate child’s psychiatric, cognitive and social problems rather than address the issue. Looking for a quick fix |

Lacks focus. Lacks long term direction. Putting out fires. |

Short term and long term goals. Comprehensive focus. Is able to see the big picture. |

| OVERALL APPROACH |

Passive | Reactive | Proactive |

| GOALS | Cure the epilepsy and other issues will be resolved. Action is not necessary only optional. Time will be curative. |

Short term or misaligned with child’s needs. Action lacks direction. |

Simultaneous short term and long term goals. Action is required. |

4.2 Recommendations for Clinicians by Zone

Parents in Zone 1 are likely to be overly focused on their child’s seizures. They are likely to blame the medicine or the seizures for all the child’s difficulties. They may feel that “waiting for seizure control” is the best course of action. They may view the child’s struggles as a temporary result of this medical condition. Clinicians may need to provide extra education about realistic side effects of medication and what types of behaviors may or may not change with seizure control. Parents may be reluctant to discuss concerns about the child’s daily functioning. Clinicians are encouraged to initiate conversations with parents about co-occurring problems regarding school, social functioning, attention, behavior problems, or emotional regulation, and simply asking if a particular domain (like sleep) is a problem will be insufficient, since parents in Zone 1 may not identify notable changes in sleep as problematic. Open ended questions like “tell me about your child’s sleep” or “what is your child’s sleep routine?” may result in additional and useful information about sleep.

Parents in Zone 2 are more willing and able to talk about co-occurring problems as well as seizures; however, clinicians will need to help them integrate these concerns in order to identify treatment goals for both issues simultaneously. Parents in Zone 2 are likely working to address their child’s needs, although their energy may be unfocused. Clinicians may need to facilitate discussion of long term expectations and goals for the child, and identify a course of action to accomplish those goals. Parents in Zone 2 may require guidance to recognize appropriate goals and expectations for their child.

Parents in Zone 3 may need help from clinicians to re-focus their efforts to achieve small, short-term goals since they are more likely than parents in Zone 1 or Zone 2 to become overwhelmed by long term goals such as driving, living independently, attending college, or finding employment. Clinicians can also work with parents in Zone 3 to identify tangible steps to make progress towards the long term goals. Most parents in Zone 3 continue to need guidance, information and feedback to assist them in meeting the needs of their child.

4.3 Limitations

This was a small study with a limited range of parents. All children had well controlled epilepsy with only occasional break through seizures. The majority of participants were on 1 seizure medication. Their presentation and clinical issues may be different than children with uncontrolled epilepsy. The children of these parent participants were known to have co-occurring problems; children with clean histories or a lack of comorbidities were not invited to participate. As such, the transferability is limited to children with well controlled epilepsy and comorbid cognitive, social, attention, or psychiatric problems.

4.4 Future Research

Children with epilepsy and no diagnosable psychiatric, learning, or attention disorder are still likely to have age-typical behavior or learning challenges. It is unclear if the parents of these children fit into the zone framework outlined above. Additionally, it will be important to study the extent to which this zone framework is helpful to clinicians in understanding parent perspectives. Anecdotally, several of the authors on this paper have used the zones to inform our clinical work with parents of children with epilepsy. Finally, we would also like to investigate clinical outcomes by zone to see if there is a difference between levels of success in seizure control and treatment of the comorbidities. We would like to explore recommendation compliance by zone to see if this is a barrier to following through with referrals or treating the co-occurring problems.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Understanding parents’ perspectives will enhance communication between parents and clinicians.

Understanding parents’ perspectives helps clinicians provide improved patient-centered care.

Zones of understanding provide a structure for clinicians to provide guidance and feedback to parents.

Acknowledgements

We would like to sincerely thank all of the parents who participated in this study. The parents were willing to take time out of their busy lives to describe to us what it is like to have a child with epilepsy. We appreciate all of their efforts, and we are working hard to apply what we learned to make us better clinicians and researchers. This study was supported by in part by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427 (JEJ) and People Against Childhood Epilepsy (PACE) (JEJ).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

6. Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Statement We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We further confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us.

We confirm that we have given due consideration to the protection of intellectual property associated with this work and that there are no impediments to publication, including the timing of publication, with respect to intellectual property. In so doing we confirm that we have followed the regulations of our institutions concerning intellectual property.

We further confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved human participants has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies and that such approvals are acknowledged within the manuscript.

We understand that the Corresponding Author is the sole contact for the Editorial process (including Editorial Manager and direct communications with the office). Jana E. Jones PhD is responsible for communicating with the other authors about progress, submissions of revisions and final approval of proofs. We confirm that we have provided a current, correct email address which is accessible by the Corresponding Author.

7. References

- [1].Jones JE, Watson R, Sheth R, Caplan R, Koehn M, Seidenberg M, Hermann B. Psychiatric comorbidity in children with new onset epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49:493–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Buelow JM, McNelis A, Shore CP, Austin JK. Stressors of parents of children with epilepsy and intellectual disability. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006;38:147–54. 176. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200606000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ferro MA, Speechley KN. Depressive symptoms among mothers of children with epilepsy: a review of prevalence, associated factors, and impact on children. Epilepsia. 2009;50:2344–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lv R, Wu L, Jin L, Lu Q, Wang M, Qu Y, Liu H. Depression, anxiety and quality of life in parents of children with epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009;120:335–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mu PF. Paternal reactions to a child with epilepsy: uncertainty, coping strategies, and depression. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:367–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wood LJ, Sherman EM, Hamiwka LD, Blackman MA, Wirrell EC. Maternal depression: the cost of caring for a child with intractable epilepsy. Pediatr Neurol. 2008;39:418–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Duffy LV. Parental coping and childhood epilepsy: the need for future research. J Neurosci Nurs. 2011;43:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Blocher JB, Fujikawa M, Sung C, Jackson DC, Jones JE. Computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy for children with epilepsy and anxiety: a pilot study. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;27:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wu KN, Lieber E, Siddarth P, Smith K, Sankar R, Caplan R. Dealing with epilepsy: parents speak up. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13:131–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ott D, Caplan R, Guthrie D, Siddarth P, Komo S, Shields WD, Sankar R, Kornblum H, Chayasirisobhon S. Measures of psychopathology in children with complex partial seizures and primary generalized epilepsy with absence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:907–14. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Roeder R, Roeder K, Asano E, Chugani HT. Depression and mental health help-seeking behaviors in a predominantly African American population of children and adolescents with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1943–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].IOM (Instituted of Medicine) Epilepsy across the spectrum: Promoting health and understanding. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:42–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6996.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. SAGE Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.