Abstract

Certain groups of physically linked genes remain linked over long periods of evolutionary time. The general view is that such evolutionary conservation confers ‘fitness’ to the species. Why gene order confers ‘fitness’ to the species is incompletely understood. For example, linkage of IL26 and IFNG is preserved over evolutionary time yet Th17 lineages express IL26 and Th1 lineages express IFNG. We considered the hypothesis that distal enhancer elements may be shared between adjacent genes, which would require linkage be maintained in evolution. We test this hypothesis using a bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic model with deletions of specific conserved non-coding sequences. We identify one enhancer element uniquely required for IL26 expression but not IFNG expression. We identify a second enhancer element positioned between IL26 and IFNG required for both IL26 and IFNG expression. One function of this enhancer is to facilitate recruitment of RNA polymerase II to promoters of both genes. Thus, sharing of distal enhancers between adjacent genes may contribute to evolutionary preservation of gene order.

Introduction

In response to antigen stimulation, CD4+ helper T cells differentiate into distinct lineages defined by the cytokines they produce in response to secondary antigen challenge. Lineages include Th1 cells that produce IFN-γ, Th2 cells that produce IL-4, IL-13, IL-5 and IL-10, and Th17 cells that produce IL-17a, IL-17f, IL-22 and IL-26. These distinctions are not absolute as certain cytokines, such as IL-10, are produced by multiple lineages, including distinct lineages such as T regulatory cells. Similarly, IFN-γ and IL-17 display both highly restricted patterns of expression by T cells but these cytokines can also be co-expressed by certain T cell populations. Nevertheless, proper regulation of cytokine gene expression is critical to a successful adaptive immune response.1–16

Proper regulation of cytokine gene expression may depend in part upon their order in the eukaryotic genome. For example, IL4, IL5 and IL13 are located on human chromosome 5 spanning approximately 150 kb and this order is conserved across multiple vertebrate species expressing these genes. A locus control region within this area is critical for expression of these lineage specific genes.17 Similarly, IL17A and IL17F genes are positioned adjacent to one another on human chromosome 6 and this gene order is also preserved across multiple vertebrate species. In contrast, order of IFNG, IL26, and IL22 genes is also preserved across multiple vertebrate species from zebrafish and chickens to humans and evidence does not support the notion that these three genes are co-expressed suggesting there may be additional evolutionary reasons to preserve gene order.18–21

Although order of IFNG, IL26, and IL22 genes is conserved across multiple species, the IL26 gene is deleted in rodents.22 In general, cell-type specific expression and transcriptional regulation of neighboring IFNG and IL22 appears relatively similar in humans and rodents, suggesting that deletion of IL26 does not have a great impact upon these processes. However, absence of IL26 from rodent genomes has clearly hindered progress towards understanding its role in immunity. While IL-26 has a unique receptor, rodents may functionally compensate for the loss of IL-26 through another protein which signals through STAT3, such as IL-22.23

In eukaryotic genomes, preservation of gene order is greater than expected by chance suggesting the existence of selective or evolutionary pressure to preserve gene order.24, 25 Different arguments have been put forth to account for preservation of gene order. For example, gene families, such as the Th2 gene family, the beta-globin gene family, or the growth hormone gene family are expressed in a coordinated fashion and this may be aided by preservation of gene order. Similarly, preservation of order of genes exhibiting a common feature, such as high rates of transcription, tissue-specific transcription, or genes that encode proteins that participate in a common pathway, e.g. specific metabolic pathways, may provide evolutionary advantages.26–31 However, these explanations probably do not account for the majority of determinants of conservation of gene order in eukaryotic genomes.

Genes are not the only genetic elements whose order is conserved in vertebrate genomes. The order of evolutionarily conserved non-coding sequences (CNS) is also preserved in vertebrate genomes. For example, the order of CNS across the IL26-IFNG genomic region is absolutely conserved between mice and humans.32–35 The general view of CNS is that evolutionary conservation of DNA sequence implies functional importance and CNS are known to function as promoters, enhancers, repressors, boundary elements, and locus control regions to regulate gene transcription.36–40 In this light, we considered the possibility that IL26 and IFNG may share common CNS regulatory elements and this may contribute to conservation of gene order across vertebrate species. To test this hypothesis, we determined expression levels of IFNG and IL26 from transgenic mice containing a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) encompassing both IFNG, IL26 and flanking genomic regions with or without specific CNS deletions.41, 42 Our results identify CNS that are required for IL26 expression but not IFNG expression and CNS that are shared between IL26 and IFNG and required for expression of both genes. This general notion that CNS can be functionally shared between adjacent genes may contribute evolutionary pressure to preserve not only gene and CNS order but also genomic distance between genes.

Results

IL26 expression in transgenic mice

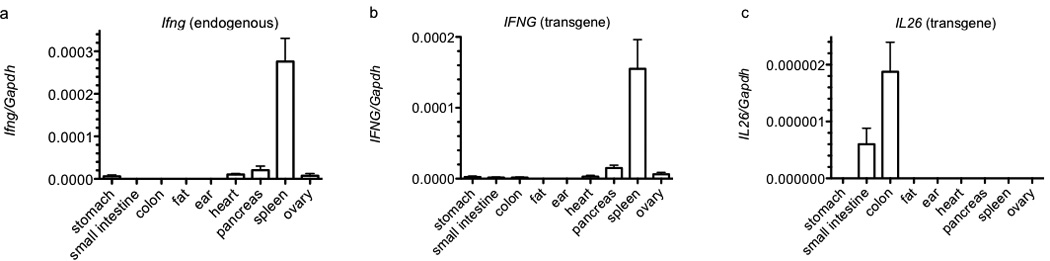

We analyzed expression levels of IFNG, IL26 and IL22 by quantitative RT-PCR in different organs from mice with a 190 kb human BAC transgene containing full-length human IFNG and IL26 genes. The 3’ end of the human IL22 gene is truncated in this BAC transgene. For comparison, we determined levels of endogenous Ifng transcripts. Of the organs examined, expression of Ifng was highest in spleen (Figure 1a). Similarly, expression of transgenic IFNG was highest in spleen (Figure 1b). Quantitative expression levels of murine Ifng and human IFNG in spleen were of similar magnitude. In contrast, expression levels of transgenic IL26 were highest in colon and small intestine and were undetectable in other organs including spleen (Figure 1c). Expression levels of IL26 in colon were approximately 100-fold lower than expression levels of either Ifng or IFNG in spleen. Nevertheless, IL26 expression in colon was higher than Ifng or IFNG expression in colon. We did not detect human IL22 expression in any tissue in transgenic animals. Thus, we conclude that IL26 expression from the BAC transgene exhibits an organ specific pattern in mice.

Figure 1.

Basal IFNG and IL26 expression in organs from BAC transgenic mice. Single cell suspensions were prepared from the indicated organs by mechanical disruption or collagenase digestion. Synthesis of cDNA was from purified total RNA. Transcript levels were determined using Taqman assays. Transcript levels of (a) Ifng, (b) IFNG, and (c) IL26 are expressed relative to Gapdh. Error bars are S.D.

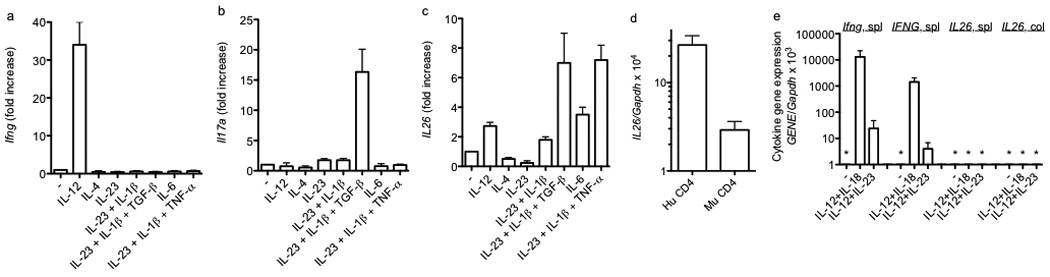

We next analyzed changes in expression of IL26 in CD4+ T cell cultures. Commercially available anti-human IL-26 antibodies produced uniform, non-specific staining in mouse lymphocytes and tissues from both BAC transgenic and non-transgenic mice. We were also not able to obtain pairs of antibodies suitable for ELISA. Therefore, we focused on transcript measurements. Transgenic T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 under Th1, Th2, and Th17 polarizing conditions. After 5 days, cell cultures were harvested and re-stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 5 hours. As is well-established, IL-12 was the dominant cytokine polarizing T cells to become Ifng-expressers (Figure 2a) and the combination of IL-23, IL-1β and TGF-β were the dominant cytokines polarizing T cells to become Il17a-expressers (Figure 2b). In contrast to these results, polarization of T cells into IL26-expressors exhibited significantly more flexibility (Figure 2c). Specifically, the combination of IL-23, IL-1β and TGF-β was as effective as the combination of IL-23, IL-1β and TNF-α at driving T cells to differentiate into IL26 producers, while IL-6 alone was somewhat less effective at driving this differentiation process. Even IL-12 alone or the combination of IL-23 and IL-1β were somewhat efficient at driving T cells to differentiate into IL26 producers. Further, we did not detect increased IL26 expression in T cells during the primary five-day culture period. Increased IL26 expression required secondary stimulation of differentiated T cells with either anti-CD3 or PMA and ionomycin. In contrast, stimulation of differentiated T cells with IL-12 and IL-18 did not increase expression of IL26.

Figure 2.

Polarizing cytokine requirements for expression of Ifng, Il17a, and IL26 by effector CD4 T cells. CD4 T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 in the presence of the indicated cytokines. After 5 days, cultures were harvested and restimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 6 hrs. Cultures were harvested and transcript levels of (a) Ifng, (b) Il17a, and (c) IL26 were determined as described in Figure 1. Results are expressed relative to cultures stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 in the absence of additional cytokines. (d) Human CD4+ Th1 cells (Hu CD4) or murine BAC-transgenic CD4+ Th1 cells (Mu CD4) were stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin. Cultures were harvested and IL26 transcript levels determined as in Figure 1. (e) Murine BAC-transgenic splenic or colonic NK cells (DX5+) were stimulated for 48 hr. Transcript levels of Ifng, IFNG, and IL26 were determined as described in Figure 1. Results are expressed relative to Gapdh transcript levels. Error bars are S.D. * = not detected.

We next compared IL26 transcript levels in transgenic mouse T cells to human T cells. We isolated peripheral CD4+ T cells from healthy human donors or splenic mouse CD4+ T cells and cultured cells under Th1 polarizing conditions for five days. At day five, cells were stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin and IL26 transcript levels were determined by quantitative PCR. IL26 transcript levels in mouse CD4+ T cells produced from the BAC transgene were about 10-fold lower than IL26 transcripts in human CD4+ T cells produced from the endogenous gene (Figure 2d). We also determined IL26 expression in NK cells, either unstimulated or stimulated with IL-12 + IL-18 or IL-12 + IL-23. We isolated BAC transgenic splenic or colon mucosa derived DX5+ NK cells. In contrast to expression in human and mouse CD4+ T cells, we did not observe IL26 transcripts in mouse DX5+ NK cells (Figure 2e). As such, we concluded that the BAC transgene displayed organ-specific expression of IL26 and, during in vitro culture, T cell expression of IL26. Therefore, we employed the BAC transgenic system to examine regulation of IL26 transcription in T cells.

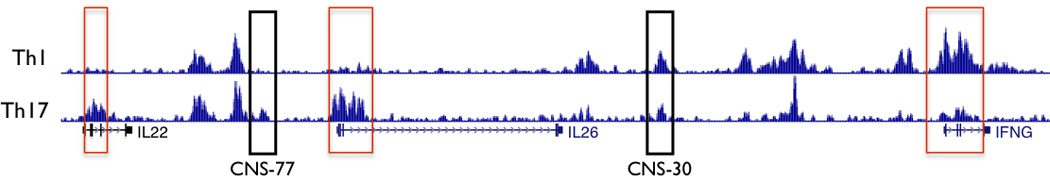

H3K27Ac marks at CNS across the IL22-IL26-IFNG locus in Th1 and Th17 effector cells

Histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27Ac) is primarily associated with active promoters and enhancers.39, 40 We compared H3K27Ac ChIP-seq data from human peripheral CD4+ CD25− IL-17+ (Th17) and IL-17− cells (Th1) cells stimulated with PMA and ionomycin obtained from the Roadmap Encode project.43, 44 H3K27Ac marks were present at the promoters of IL26 and IL22 in Th17 cells but not Th1 cells and at the promoter of IFNG in Th1 cells but not Th17 cells (Figure 3). In contrast, distal CNS displayed a different pattern of H3K27Ac. For example, H3K27Ac selectively marked CNS-77 (located −77 kb from IFNG) in effector Th17 cells but not effector Th1 cells. In contrast, H3K27Ac marked CNS-30 in both effector Th17 and effector Th1 cells. A CNS region from about −15 kb to −20kb from the IFNG promoter exhibited Th1 selective H3K27Ac marks. Given prevailing theories ascribing function associated with specific histone marks, a testable hypothesis would be that CNS-77 is an enhancer for Th17-dependent IL22 or IL26 transcription, CNS-30 is a dual function enhancer participating in both Th17-dependent IL26 transcription and Th1-dependent transcription of IFNG, and that CNS-15–20 contributes only to Th1-dependent IFNG transcription.

Figure 3.

H3K27 acetylation across the IL22-IL26-IFNG gene region in human effector Th1 and Th17 cells. H3K7Ac Chip-Seq data from the ROADMAP ENCODE project were obtained from the U.C.S.C. genome browser. Rectangles in red identify promoter regions. Black rectangles identify two CNS, CNS-77 and CNS-30.

CNS-77 is necessary for IL26 expression

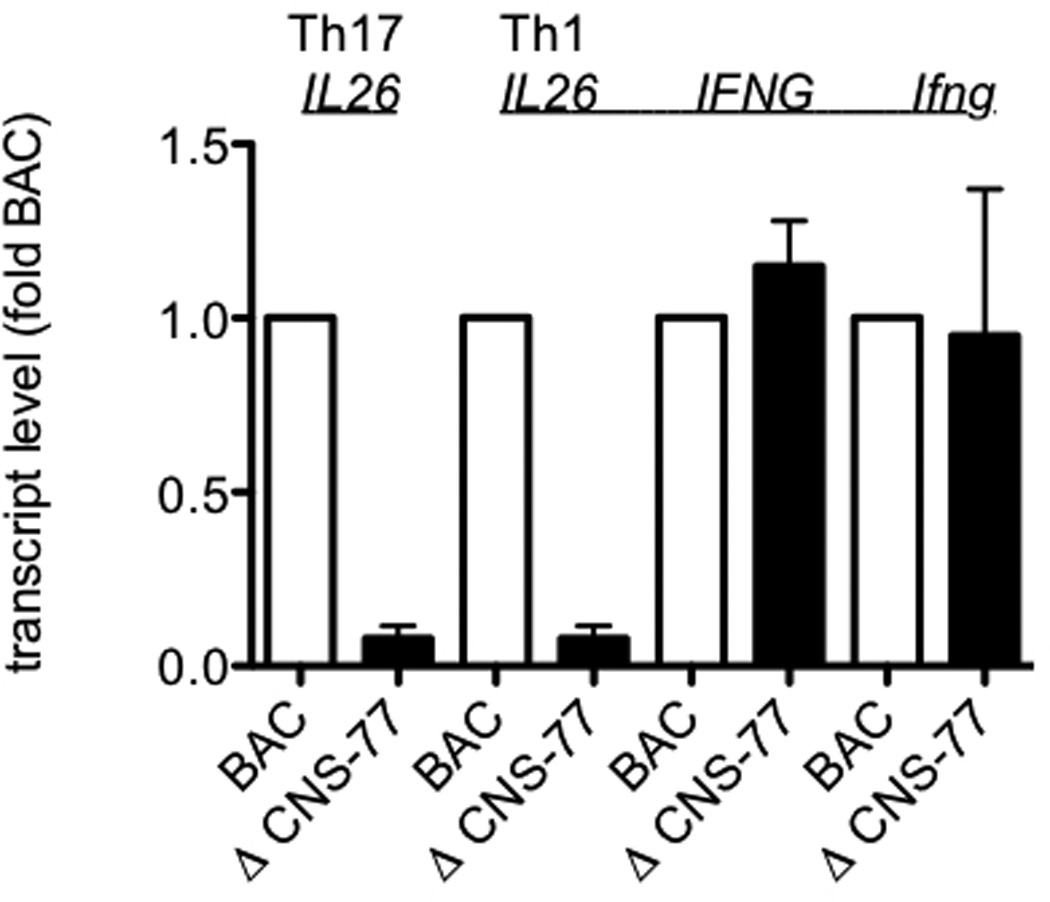

To assess functional requirements of distal CNS for IFNG expression, we have analyzed IFNG expression from BAC transgenes with and without deletions of specific CNS.41, 42 Therefore, we employed this same system to determine if distal CNS were also required for IL26 expression. We first analyzed CNS-77 positioned 77 kb upstream of the IFNG transcriptional start site and ~ 12 kb upstream of the IL26 transcriptional start site, ΔCNS-77. Transgenic BAC WT and ΔCNS-77 CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 under Th1 or Th17 polarizing conditions for 5 days. Cultures were harvested and restimulated for 6 hrs with PMA and ionomycin. After restimulation, cells were harvested and Ifng, IFNG, and IL26 transcript levels were determined by PCR. Transcript levels were normalized to those expressed by WT BAC T cells. We found that CNS-77 was required for IL26 expression by T cells differentiated under Th17 polarizing conditions (Figure 4). In ΔCNS-77 transgenic T cell cultures polarized under Th17 conditions, IL26 expression levels were reduced by approximately 90% relative to WT BAC T cell cultures. Similarly, in ΔCNS-77 transgenic T cell cultures polarized under Th1 conditions, IL26 expression levels were reduced by ~ 90% relative to WT BAC T cell cultures. In contrast, IFNG and Ifng expression levels were equivalent in ΔCNS-77 and WT BAC T cell cultures polarized under Th1 conditions. We conclude that CNS-77 is necessary for IL26 expression by T cells polarized under Th17 or Th1 conditions but is unnecessary for IFNG expression by T cells polarized under Th1 conditions.

Figure 4.

CNS-77 is required for IL26 expression but not IFNG expression. WT and ΔCNS-77 CD4 T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 under Th1 and Th17 polarizing conditions. After 5 days, cultures were harvested and restimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 6 hrs. Transcript levels of IL26, IFNG, and Ifng were determined as described in figure 1. Results are expressed relative to WT BAC levels. Error bars are S.D.

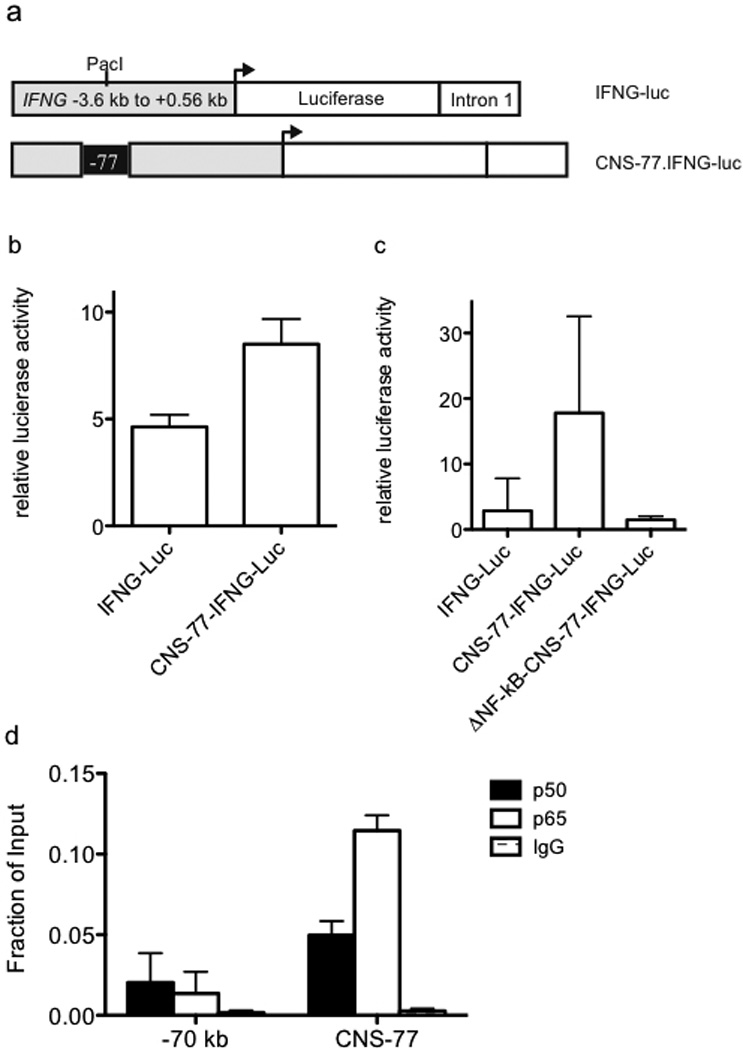

Distal activating sequences/enhancers stimulate transcription in reporter assays when placed next to heterologous promoters and this methodology has been employed to validate enhancer activity of DNA elements.40, 45–48 To validate CNS-77 as an enhancer we cloned the CNS-77 element into a non-conserved Pac1 site in a well-characterized IFNG-luciferase vector (Figure 5a).49, 50 While our data did not support CNS-77 as an IFNG regulatory element, the IFNG-luciferase vector was chosen because it is selectively expressed in T cells thus making it possible to test enhancer activity of CNS-77. Further, the Pac1 cloning site did not interfere with any IFNG regulatory site. We transfected the IFNG-luciferase vector with or without the CNS-77 element into primary BALB/C splenocytes cultured with anti-CD3/CD28 for three days and measured luciferase activity after restimulation by PMA/Ionomycin. Inclusion of CNS-77 resulted in a relative increase in luciferase activity demonstrating the presence of enhancer function (Figure 5b). Next, we identified two potential NF-κB binding sites within the CNS-77 element. To test for the function of these potential NF-κB response elements, we deleted one of these binding sites and prepared a new construct, ΔNF-κB-CNS-77 IFNG-luciferase. We transfected Jurkat T cells with the three different luciferase constructs and, after recovery, restimulated with PMA/ionomycin. Deletion of one NF-κB site abrogated enhancer function (Figure 5c). We conclude from these experiments that CNS-77 is an enhancer element. Our results also support the notion that CNS-77 is an NF-κB-response element.

Figure 5.

Transcriptional enhancer activity of CNS-77. (a) Schematic of the IFNG-luciferase reporter construct with and without CNS-77 inserted into the Pac1 cloning site. (b) Purified CD4+ T cells were transfected with IFNG-luciferase reporter constructs. After 24 hrs, transfected cells were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for an additional 24 hrs. Luciferase activity in cell lysates was determined and results are expressed as relative luciferase activity. (c) Purified Jurkat T cells were nucleofected with the indicated reporter constructs and cultured and stimulated as in (b). Luciferase activity in cell lysates was determined and results are expressed as relative luciferase activity. (d) Peripheral human CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 4 hours and NF-κB binding to CNS-77 was determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. Error bars are S.D.

Finally, we determined if CNS-77 binds NF-κB in vivo. To do so, human CD4+ cells were isolated from PBMC, stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin for four hours and processed for chromatin immunoprecipitation assay with antibodies to either the NF-κB p50 subunit, NF-κB p65 subunit or an IgG isotype control (Figure 5d). We observed binding of both p50 and p65 to CNS-77. As a control, we measured NF-κB binding to a neighboring genomic position located −70 kb from the IFNG promoter that was not marked by H3K27Ac. We found that p50 and p65 subunits of NF-κB were not bound to these sites. Thus, we conclude that NF-κB binds to CNS-77, in vivo, and CNS-77 possesses transcriptional enhancer activity in reporter assays.

Enhancer function of CNS-30 is shared between IL26 and IFNG

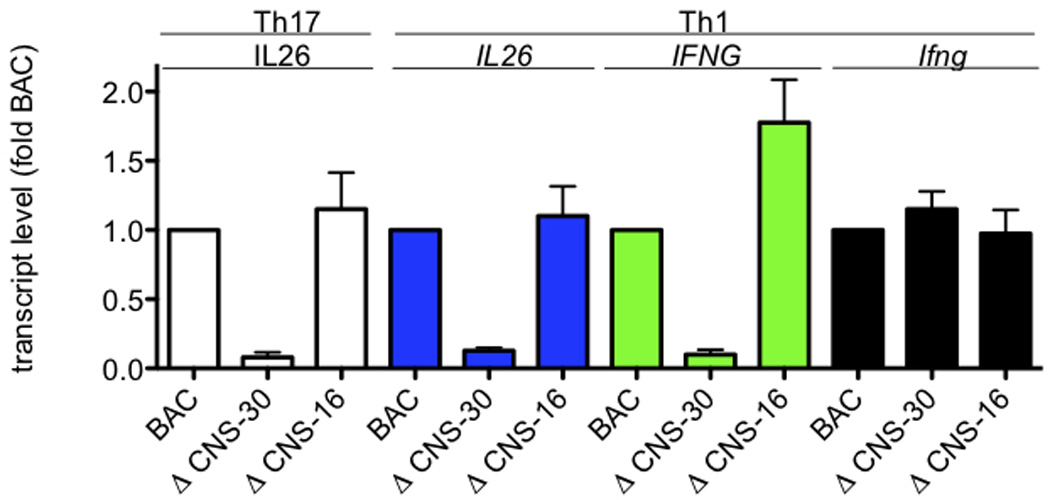

CNS-30 is necessary for IFNG expression by T cells cultured under primary Th1 polarizing conditions (no TCR restimulation) and by differentiated effector Th1 cells.41 In contrast, CNS-16 has a repressor function and deletion of CNS-16 results in a marked increase in IFNG expression under Th2 polarizing conditions.42 Therefore, we determined if CNS-30 or CNS-16 were necessary for IL26 expression under either Th17 or Th1 polarizing conditions. T cells from BAC WT, ΔCNS-30 or ΔCNS-16 transgenic mice were cultured under Th17 or Th1 polarizing conditions for 5 days. After harvest, cells were restimulated with PMA and ionomycin. Transcript levels of IL26, IFNG and Ifng were determined by PCR and normalized to transcript levels present in BAC WT transgenic cultures. We found that expression of transgenic IL26 in either Th17 polarized cultures or Th1 polarized cultures was largely abrogated by deletion of CNS-30 (Figure 6). In contrast, IL26 expression was not dependent upon the presence of CNS-16. CNS-30 was required to achieve IFNG expression by Th1 polarized cultures. Expression of the endogenous Ifng gene was not affected by the presence of any of the transgenes. We conclude from these experiments that CNS-30 plays an equally important enhancer role to regulate both IFNG and IL26 transcription.

Figure 6.

Both IL26 and IFNG share requirements for CNS-30 for efficient expression. Transgenic IFNG-BAC WT, ΔCNS-30, and ΔCNS-16 CD4 T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 under Th1 or Th17 polarizing conditions. After 5 days, cultures were harvested and restimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 6 hrs. Cultures were harvested and transcript levels of IL26, IFNG, and Ifng were determined as described in Figure 1. Results are expressed relative to WT BAC levels. Error bars are S.D.

CNS-30 is required for Pol II binding to the IFNG/IL26 locus

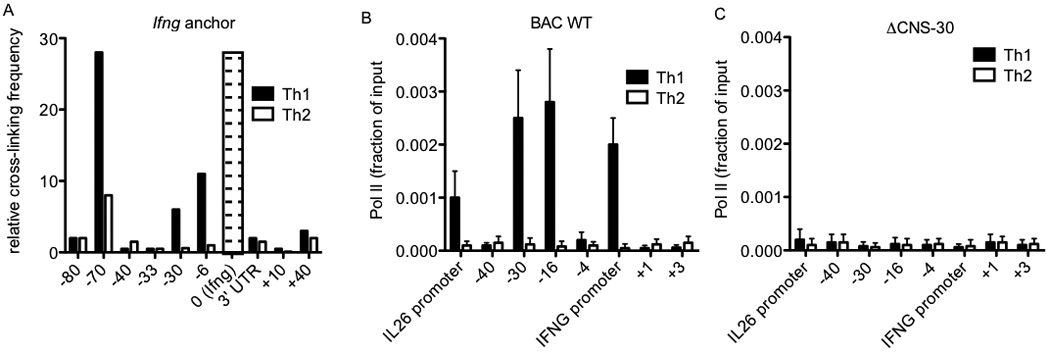

Above results indicate that CNS-30 is a necessary enhancer for both IFNG and IL26 transcription. Previous reports have described CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) and T-bet dependent looping between the first mouse Ifng intron and two distal CTCF binding sites upon Th1 differentiation, one positioned −70 kb upstream of Ifng.51, 52 The −70 CTCF site is orthologous to the beginning of the first intron of human IL26, which also loops into IFNG upon Th1 differentiation. These results have been interpreted to mean that these two CTCF binding sites demarcate a Th1-specific domain to insulate Ifng and its enhancers. However, an additional hypothesis is that looping is a conserved genomic feature that allows CNS-30 to act as an enhancer of both IFNG and IL26. To confirm Th1 specific looping between CNS-30, Ifng and the mouse Il26 pseudogene, we cultured CD4+ T cells under Th1 and Th2 polarizing conditions for three days, isolated and processed nuclei for chromatin conformation capture (3-C) assay. Using Ifng as an anchor, we were able to detect Th1-specific interactions between Ifng and both the mouse CNS-30 ortholog and the Il26 pseudgoene (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

RNA polymerase II occupancy across the IL26-IFNG genomic region is dependent upon CNS-30. (a) Average crosslinking frequency between Ifng (indicated by the open bar with dashes) and the indicated genomic positions in nuclei from effector Th1 and Th2 cells. (b & c) RNA pol II recruitment to the indicated genomic positions in (b) BAC WT and (c) ΔCNS-30 transgenic Th1 and Th2 cells determined by ChIP assay. Results are expressed as fraction of input. Error bars are S.D.

Using a BAC transgenic model, we previously demonstrated that CNS-30 is required for RNA polymerase II (Pol II) binding to the IFNG locus in Th1 cells.41 Given the Th1-specific looping between CNS-30 and both IFNG and IL26, we next determined if CNS-30 was required for Pol II binding to IL26 in our BAC transgenic model. Transgenic BAC WT and ΔCNS-30 CD4+ T cells were cultured for three days under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions and processed for chromatin immunoprecipitation with antibodies for Polymerase II or an IgG control. We observed Th1-specific binding of Pol II to CNS-30, CNS-16 and the IFNG promoter across BAC transgene (Figure 7b). We also observed Th1-specific Pol II binding to the IL26 promoter, which is consistent with our expression data. In contrast, we did not detect binding of Pol II to either the IFNG promoter or the IL26 promoter in ΔCNS-30 cultures (Figure 7c). As such, CNS-30 is required for both expression of IFNG and IL26, as well as Pol II binding to promoters of IFNG and IL26.

Discussion

The general view is that evolutionary conservation of DNA sequence in coding and non-coding regions of the genome implies functional value. Similarly, evolutionary conservation of gene order in the genome is thought to have functional value. An example of this synteny is the conservation of gene order among the Th1 gene, IFNG, and the two Th17 genes, IL26 and IL22 from Xenopus and zebrafish to chickens and humans.19, 20 Further, genomic order of CNS across this region is also evolutionarily preserved. In human Th1 cells, the IL26 gene loops close into the IFNG gene51, and in murine Th1 cells, the Il26 psuedogene loops into the Ifng gene.52 However, many of the features commonly associated with syntenic genes, e.g. co-expression, tissue-specific expression, level of expression, genes encoding proteins involved in common biological processes, gene families, or gene duplications, do not readily explain IFNG-IL26-IL22 conservation of gene order. Therefore, we considered an alternate hypothesis that IFNG and IL26 genes share common CNS necessary for their transcription and, as such, preservation of gene order and distance and CNS order and distance is essential to maintain cell-type specific expression of both genes in lineage-specific manners.

We have produced transgenic murine lines with human BACs containing the complete IFNG and IL26 coding sequences with additional 5’ and 3’ genomic sequence or with deletions of specific CNS.41, 42 Our analyses of IL26 expression demonstrate tissue-specific expression in colon and small intestine but not spleen, and expression under both Th1 and Th17 polarizing conditions, in vitro. Further, cytokines required to polarize T cells to produce IL26 were much less restrictive than those required defined to induce Th1 or Th17 polarization and a number of different combinations of cytokines were capable of driving T cells to differentiate into IL26-producers. At this point, reasons behind this are not entirely clear. Since IL26 is deleted from rodent genomes, this cytokine and its regulation have been examined in far less detail than many other cytokines and less restricted regulation may be a general property of this cytokine gene. Alternatively, since IL26 is produced from a human BAC transgene in this model, additional regulatory elements missing from the BAC transgene may be necessary to achieve proper regulation of the IL26 gene. However, the low levels of IL26 transcript levels relative to IFNG transcript levels seen in this transgenic model are consistent with those seen in human lymphocytes. Nevertheless, our results demonstrate tissue specific expression and some degree of lineage specific expression of IL26 from the BAC transgene.

A simple model of T helper cell lineage differentiation is that Th1 cells express IFN-γ while Th17 cells express IL-17, IL-22 and IL-26. However, there are also common cellular sources of IL-26, IFN-γ and IL-22. For example, all three cytokines can be expressed by “T helper 22” cells.53 Moreover, recent evidence indicates that human Th17 cells, polarized in vivo, are capable of producing IFN-γ.54 In addition to Th17 cells and Th22 cells, there is a specialized gut homing innate lymphoid cell, once thought to be a natural killer cell subset, which produces IL-26, IL-22 and IFN-γ.55 It is likely that these triple positive subsets share IFNG, IL22 and IL26 cis regulatory elements for co-expression of all three genes. As such, in future work, we will determine how the IL26/IL22/IFNG locus is distinguished among Th subsets that selectively express only IL26, IL22 or IFNG or co-express two or more of these linked genes.

Our analysis demonstrates there is hierarchy of distal CNS usage to achieve proper IFNG transcriptional control.41, 42 The CNS-30 element is necessary for IFNG expression by T cells under all conditions examined. The CNS-4 element is required for IFNG expression by effector Th1 cells and memory Th1 cells in response to secondary TCR stimulation. In contrast, the CNS+19–20 element is only required for IFNG expression by memory Th1 cells. On the other hand, NKT cells require CNS-30 and CNS+19–20 elements but not the CNS-4 element. Usage of distal CNS by NK cells is markedly different and NK cells exhibit a partial need for CNS-4, CNS-16 and CNS+19–20 but exhibit no obligatory requirement for any single CNS. Thus, each distal CNS contributes very diverse functions to the final regulation of IFNG transcription.

The IL26 transcriptional start site is positioned ~66 kb from the IFNG transcriptional start site and the IL26 3’ end is ~ 41 kb from the IFNG transcriptional start site. A distal CNS, CNS-77, with characteristics of a NF-κB response element is necessary for IL26 expression but is dispensable for IFNG expression. Thus, similar to IFNG, IL26 transcription also requires distal CNS elements. Our results also clearly demonstrate that IL26 and IFNG share usage of distinct distal regulatory CNS. Thus CNS-30 is required for both IL26 and IFNG expression. Given that genomic regions containing IL26 and IFNG loop together, at least under Th1 differentiation conditions, it is reasonable to speculate that this looping also brings CNS-30 in close proximity to both IL26 and IFNG and contributes to transcriptional activation of both genes in either effector Th1 cells or to IL26 transcriptional activation in effector Th17 cells. In contrast, CNS-16, which plays a role in repression of IFNG transcription in effector Th2 cells, does not appear to play a role in repression or activation of IL26 transcription. At this point, we do not yet know if IL26 utilizes additional CNS with diverse functions to achieve proper lineage-specific expression similar to that seen for IFNG.

The dynamic nature of transcriptional regulation is becoming increasingly evident. Dynamic movement of genes into and out of ‘transcription factories’ is associated with active transcription.56, 57 Alterations in intra-chromosomal and inter-chromosomal conformations are associated with gene activation and gene repression.58–60 Establishing histone marks across a genomic region were once thought to represent permanent modifications are now recognized as highly dynamic as specific enzymes have been identified that both write and erase the ‘histone code’ and diverse developmental processes are associated with dynamic changes in how the histone code is written and erased at specific gene loci.40 Further, studies of transcription factor occupancy at specific response elements demonstrate very rapid on and off rates, occupancy by multiple trans-acting factors and it is highly likely that these interactions are also highly dynamic.61, 62 Our results demonstrate that CNS enhancer elements are also functionally highly dynamic and may be conformationally highly dynamic capable of moving between two adjacent genes to drive their transcription.

Findings presented here represent a specific case of the shared usage of distinct distal CNS by two genes. Although both genes encode cytokines, IL-26 and IFN-γ perform unique, non-overlapping functions in the innate and adaptive immune systems and display unique expression patterns. For several decades, chromosomal rearrangements were thought to occur at random sites during evolution.63 However, with the advent of fine-scale genome sequencing and advanced computational analysis, it is now appreciated that individual conserved gene loci are resistant to synteny disruptions.64 The IFNG/IL26/IL22 locus represents a conserved locus with shared usage of distinct distal regulatory elements. In mice, the coding potential of Il26, but not the order of surrounding CNS and genes, is disrupted. Our model is thus consistent with the hypothesis that genomic order within loci is conserved because of the obligate requirement for CNS to regulate transcription. Alternatively, translocations and gene disruptions may free genes from their obligate enhancers and allow them to develop independent expression patterns or independent functions. Examples of these classes include duplications of gdf to gdf6a and gdf6b genes and pax6 to pax6a and pax6b genes in zebrafish resulting in divergence of distal regulatory CNS and emergence of new developmentally regulated gene expression patterns.65, 66 Future studies of the interferon gamma and interleukin 26 locus in mice and other rodents will reveal the evolutionary requirements for distal regulatory element conservation once a co-regulated gene, IL26, is removed from the genome.

Materials and methods

Mice and preparation of transgenic reporter lines

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), housed in the Vanderbilt University animal facilities, and used between 4–5 weeks of age. Preparation of human IFNG-BAC transgenic lines was described previously.42 The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Vanderbilt University approved all animal studies.

Cell purification and cultures

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were purified from splenocytes by positive selection per instructions by the manufacturer (Miltenyi Biotec) and cultured with plate bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 as previously described under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions. IL-12 (5 ng/ml) and anti-IL-4 (11B11: ATCC) were added to generate Th1 cultures, IL-4 (10 ng/ml) and anti-IFN-γ (10 µg/ml R4-642: ATCC) were added to generate Th2 cultures and IL-1β (20ng/ml) IL-23 (10 ng/ml) TGF-β (1 ng/ml) and anti-IFN-γ (10 µg/ml R4-642: ATCC) were added to generate Th17 cultures. Where indicated IL-6 (20 ng/ml) or TNF-α (10 ng/ml) were added. Natural killer cells were purified via DX5+ positive selection as per manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was purified from restimulated Th1, Th2 and Th17 cultures and cDNA was synthesized using Super Script III First-strand synthesis, as per manufacture’s instructions (Invitrogen). Specific transcripts were quantified using TaqMan pre-made assays as per manufacture’s instructions (Applied Biosystems). Relative changes in transcript levels were determined using the delta Ct method.

Transient transfection assays

The IFNG-luciferase plasmid was obtained from Addgene, plasmid number 17598. A detailed plasmid map is available at Addgene’s website. CNS-77 or ΔNF-κB CNS-77 was PCR amplified from RPCI11-444B24 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and moved into a Pac I site of the IFNG-luciferase plasmid. Jurkat cells were transfected with 5 µg plasmid by electroporation. After an overnight rest, cells were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 24 hours. Primary splenocytes were transfected with 2.5 µg of luciferase plasmids using Amaxa mouse T cell nucleofector kits (Lonza). Cells were rested 3 hr and stimulated over night with 2 µg/ml plate-bound anti-CD3, 2 µg/ml anti-CD28, 10 ng/ml IL-12 and IL-2.

Chromosome conformation capture (3-C) and Chip assays

The 3-C assay was performed exactly as previously described using effector Th1 and Th2 cells as chromatin sources.59 Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed according to Millipore’s online protocol with minor variations: cells were harvested by centrifugation; each protein A agarose-Ab/chromatin wash was performed twice for 10 min each and DNA was isolated by phenol-chloroform extraction. Immunoprecipitations were performed using antibodies to RNAP II (sc-899×; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), p50 and p65 subunits of NF-κB, or normal rabbit IgG control. Sequences of primers used have been previously published.41, 42

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health; RO1 AI44924 and training grant T32 HL069765. The Vanderbilt Transgenic/Embryonic Stem Cell Shared Resource is supported in part by NIH grant CA68485.

Abbreviations

- BAC

Bacterial artificial chromosome

- CNS

Conserved noncoding sequence

Footnotes

Author contributions: TMA and PLC conceived and designed the project. PLC and MAH prepared BAC constructs with deletions for transgenesis and maintained the mouse colony. PLC performed experiments. TMA and PLC wrote the manuscript with input from MAH.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Boniface K, Blumenschein WM, Brovont-Porth K, McGeachy MJ, Basham B, Desai B, et al. Human Th17 cells comprise heterogeneous subsets including IFN-gamma-producing cells with distinct properties from the Th1 lineage. J Immunol. 2010;185(1):679–687. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cella M, Fuchs A, Vermi W, Facchetti F, Otero K, Lennerz JK, et al. A human natural killer cell subset provides an innate source of IL-22 for mucosal immunity. Nature. 2009;457(7230):722–725. doi: 10.1038/nature07537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang SH, Dong C. Signaling of interleukin-17 family cytokines in immunity and inflammation. Cell Signal. 2011;23(7):1069–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Commins S, Steinke JW, Borish L. The extended IL-10 superfamily: IL-10, IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-24, IL-26, IL-28, and IL-29. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(5):1108–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lohr J, Knoechel B, Caretto D, Abbas AK. Balance of Th1 and Th17 effector and peripheral regulatory T cells. Microbes Infect. 2009;11(5):589–593. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manel N, Unutmaz D, Littman DR. The differentiation of human T(H)-17 cells requires transforming growth factor-beta and induction of the nuclear receptor RORgammat. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(6):641–649. doi: 10.1038/ni.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pene J, Chevalier S, Preisser L, Venereau E, Guilleux MH, Ghannam S, et al. Chronically inflamed human tissues are infiltrated by highly differentiated Th17 lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180(11):7423–7430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romagnani S, Maggi E, Liotta F, Cosmi L, Annunziato F. Properties and origin of human Th17 cells. Mol Immunol. 2009;47(1):3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reiner SL. Development in motion: helper T cells at work. Cell. 2007;129(1):33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weaver CT, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Harrington LE. IL-17 family cytokines and the expanding diversity of effector T cell lineages. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:821–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson NJ, Boniface K, Chan JR, McKenzie BS, Blumenschein WM, Mattson JD, et al. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(9):950–957. doi: 10.1038/ni1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou L, Chong MM, Littman DR. Plasticity of CD4+ T cell lineage differentiation. Immunity. 2009;30(5):646–655. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu J, Paul WE. Peripheral CD4+ T-cell differentiation regulated by networks of cytokines and transcription factors. Immunol Rev. 2010;238(1):247–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu J, Paul WE. Heterogeneity and plasticity of T helper cells. Cell Res. 2010;20(1):4–12. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations (*) Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:445–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee GR, Fields PE, Griffin TJ, Flavell RA. Regulation of the Th2 cytokine locus by a locus control region. Immunity. 2003;19(1):145–153. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutfalla G, Roest Crollius H, Stange-Thomann N, Jaillon O, Mogensen K, Monneron D. Comparative genomic analysis reveals independent expansion of a lineage-specific gene family in vertebrates: the class II cytokine receptors and their ligands in mammals and fish. BMC Genomics. 2003;4(1):29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-4-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Igawa D, Sakai M, Savan R. An unexpected discovery of two interferon gamma-like genes along with interleukin (IL)-22 and -26 from teleost: IL-22 and -26 genes have been described for the first time outside mammals. Mol Immunol. 2006;43(7):999–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qi ZT, Nie P. Comparative study and expression analysis of the interferon gamma gene locus cytokines in Xenopus tropicalis. Immunogenetics. 2008;60(11):699–710. doi: 10.1007/s00251-008-0326-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sequence and comparative analysis of the chicken genome provide unique perspectives on vertebrate evolution. Nature. 2004;432(7018):695–716. doi: 10.1038/nature03154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dumoutier L, Van Roost E, Ameye G, Michaux L, Renauld JC. IL-TIF/IL-22: genomic organization and mapping of the human and mouse genes. Genes Immun. 2000;1(8):488–494. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheikh F, Baurin VV, Lewis-Antes A, Shah NK, Smirnov SV, Anantha S, et al. Cutting edge: IL-26 signals through a novel receptor complex composed of IL-20 receptor 1 and IL-10 receptor 2. J Immunol. 2004;172(4):2006–2010. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavalier-Smith T. Evolution of the eukaryotic genome. In: Broda P, Oliver S, Sims P, editors. The Eukaryotic Genome: Organization and Regulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993. pp. 333–385. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maynard-Smith J. Evolutionary Genetics. 2nd Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lercher MJ, Urrutia AO, Hurst LD. Clustering of housekeeping genes provides a unified model of gene order in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2002;31(2):180–183. doi: 10.1038/ng887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lercher MJ, Urrutia AO, Pavlicek A, Hurst LD. A unification of mosaic structures in the human genome. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(19):2411–2415. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Versteeg R, van Schaik BD, van Batenburg MF, Roos M, Monajemi R, Caron H, et al. The human transcriptome map reveals extremes in gene density, intron length, GC content, and repeat pattern for domains of highly and weakly expressed genes. Genome Res. 2003;13(9):1998–2004. doi: 10.1101/gr.1649303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurst LD, Pal C, Lercher MJ. The evolutionary dynamics of eukaryotic gene order. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5(4):299–310. doi: 10.1038/nrg1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poyatos JF, Hurst LD. The determinants of gene order conservation in yeasts. Genome Biol. 2007;8(11):R233. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurst LD. Fundamental concepts in genetics: genetics and the understanding of selection. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(2):83–93. doi: 10.1038/nrg2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou W, Chang S, Aune TM. Long-range histone acetylation of the Ifng gene is an essential feature of T cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(8):2440–2445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306002101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang S, Aune TM. Histone hyperacetylated domains across the Ifng gene region in natural killer cells and T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(47):17095–1100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502129102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aune TM, Collins PL, Chang S. Epigenetics and T helper 1 differentiation. Immunology. 2009;126(3):299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoenborn JR, Dorschner MO, Sekimata M, Santer DM, Shnyreva M, Fitzpatrick DR, et al. Comprehensive epigenetic profiling identifies multiple distal regulatory elements directing transcription of the gene encoding interferon-gamma. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(7):732–742. doi: 10.1038/ni1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maston GA, Evans SK, Green MR. Transcriptional regulatory elements in the human genome. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:29–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visel A, Rubin EM, Pennacchio LA. Genomic views of distant-acting enhancers. Nature. 2009;461(7261):199–205. doi: 10.1038/nature08451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Visel A, Akiyama JA, Shoukry M, Afzal V, Rubin EM, Pennacchio LA. Functional autonomy of distant-acting human enhancers. Genomics. 2009;93(6):509–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Visel A, Blow MJ, Li Z, Zhang T, Akiyama JA, Holt A, et al. ChIP-seq accurately predicts tissue-specific activity of enhancers. Nature. 2009;457(7231):854–858. doi: 10.1038/nature07730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heintzman ND, Hon GC, Hawkins RD, Kheradpour P, Stark A, Harp LF, et al. Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global cell-type-specific gene expression. Nature. 2009;459(7243):108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature07829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins PL, Chang S, Henderson M, Soutto M, Davis GM, McLoed AG, et al. Distal regions of the human IFNG locus direct cell type-specific expression. J Immunol. 2010;185(3):1492–1501. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collins PL, Henderson MA, Aune TM. Diverse Functions of Distal Regulatory Elements at the IFNG Locus. J Immunol. 2012;188(4):1726–1733. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ernst J, Kheradpour P, Mikkelsen TS, Shoresh N, Ward LD, Epstein CB, et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 2011;473(7345):43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature09906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenbloom KR, Dreszer TR, Long JC, Malladi VS, Sloan CA, Raney BJ, et al. ENCODE whole-genome data in the UCSC Genome Browser: update 2012. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D912–D917. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kong S, Bohl D, Li C, Tuan D. Transcription of the HS2 enhancer toward a cis-linked gene is independent of the orientation, position, and distance of the enhancer relative to the gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(7):3955–3965. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gillies SD, Morrison SL, Oi VT, Tonegawa S. A tissue-specific transcription enhancer element is located in the major intron of a rearranged immunoglobulin heavy chain gene. Cell. 1983;33(3):717–728. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banerji J, Olson L, Schaffner W. A lymphocyte-specific cellular enhancer is located downstream of the joining region in immunoglobulin heavy chain genes. Cell. 1983;33(3):729–740. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banerji J, Rusconi S, Schaffner W. Expression of a beta-globin gene is enhanced by remote SV40 DNA sequences. Cell. 1981;27(2 Pt 1):299–308. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ciccarone VC, Chrivia J, Hardy KJ, Young HA. Identification of enhancer-like elements in human IFN-gamma genomic DNA. J Immunol. 1990;144(2):725–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonsky R, Deem RL, Bream JH, Lee DH, Young HA, Targan SR. Mucosa-specific targets for regulation of IFN-gamma expression: lamina propria T cells use different cis-elements than peripheral blood T cells to regulate transactivation of IFN-gamma expression. J Immunol. 2000;164(3):1399–1407. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hadjur S, Williams LM, Ryan NK, Cobb BS, Sexton T, Fraser P, et al. Cohesins form chromosomal cis-interactions at the developmentally regulated IFNG locus. Nature. 2009;460(7253):410–413. doi: 10.1038/nature08079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sekimata M, Perez-Melgosa M, Miller SA, Weinmann AS, Sabo PJ, Sandstrom R, et al. CCCTC-binding factor and the transcription factor T-bet orchestrate T helper 1 cell-specific structure and function at the interferon-gamma locus. Immunity. 2009;31(4):551–564. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eyerich S, Eyerich K, Pennino D, Carbone T, Nasorri F, Pallotta S, et al. Th22 cells represent a distinct human T cell subset involved in epidermal immunity and remodeling. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(12):3573–3585. doi: 10.1172/JCI40202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zielinski CE, Mele F, Aschenbrenner D, Jarrossay D, Ronchi F, Gattorno M, et al. Pathogen-induced human T(H)17 cells produce IFN-γ or IL-10 and are regulated by IL-1β. Nature. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature10957. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Geremia A, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Fleming MP, Rust N, Singh B, Mortensen NJ, et al. IL-23-responsive innate lymphoid cells are increased in inflammatory bowel disease. J Exp Med. 2011;208(6):1127–1133. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eskiw CH, Cope NF, Clay I, Schoenfelder S, Nagano T, Fraser P. Transcription factories and nuclear organization of the genome. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2010;75:501–506. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2010.75.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osborne CS, Chakalova L, Brown KE, Carter D, Horton A, Debrand E, et al. Active genes dynamically colocalize to shared sites of ongoing transcription. Nat Genet. 2004;36(10):1065–1071. doi: 10.1038/ng1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spilianakis CG, Lalioti MD, Town T, Lee GR, Flavell RA. Interchromosomal associations between alternatively expressed loci. Nature. 2005;435(7042):637–645. doi: 10.1038/nature03574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eivazova ER, Aune TM. Dynamic alterations in the conformation of the Ifng gene region during T helper cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(1):251–256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303919101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295(5558):1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Voss TC, Schiltz RL, Sung MH, Yen PM, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Biddie SC, et al. Dynamic exchange at regulatory elements during chromatin remodeling underlies assisted loading mechanism. Cell. 2011;146(4):544–554. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hakim O, Sung MH, Voss TC, Splinter E, John S, Sabo PJ, et al. Diverse gene reprogramming events occur in the same spatial clusters of distal regulatory elements. Genome Res. 2011;21(5):697–706. doi: 10.1101/gr.111153.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Waterston RH, Lindblad-Toh K, Birney E, Rogers J, Abril JF, Agarwal P, et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420(6915):520–562. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pevzner P, Tesler G. Human and mouse genomic sequences reveal extensive breakpoint reuse in mammalian evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(13):7672–7677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1330369100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kleinjan DA, Bancewicz RM, Gautier P, Dahm R, Schonthaler HB, Damante G, et al. Subfunctionalization of duplicated zebrafish pax6 genes by cis-regulatory divergence. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(2):e29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reed NP, Mortlock DP. Identification of a distant cis-regulatory element controlling pharyngeal arch-specific expression of zebrafish gdf6a/radar. Dev Dyn. 2010;239(4):1047–1060. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]