Abstract

Objectives

To introduce a comprehensive and reliable scoring system for the assessment of whole-knee joint synovitis based on contrast-enhanced (CE) MRI.

Methods

Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST) is a cohort study of people with, or at high risk of, knee osteoarthritis (OA). Subjects are an unselected subset of MOST who volunteered for CE-MRI. Synovitis was assessed at 11 sites of the joint. Synovial thickness was scored semiquantitatively: grade 0 (<2 mm), grade 1 (2–4 mm) and grade 2 (>4 mm) at each site. Two musculoskeletal radiologists performed the readings and inter- and intrareader reliability was evaluated. Whole-knee synovitis was assessed by summing the scores from all sites. The association of Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Index pain score with this summed score and with the maximum synovitis grade for each site was assessed.

Results

400 subjects were included (mean age 58.8±7.0 years, body mass index 29.5±4.9 kg/m2, 46% women). For individual sites, intrareader reliability (weighted κ) was 0.67–1.00 for reader 1 and 0.60–1.00 for reader 2. Inter-reader agreement (κ) was 0.67–0.92. For the summed synovitis scores, intrareader reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)) was 0.98 and 0.96 for each reader and inter-reader agreement (ICC) was 0.94. Moderate to severe synovitis in the parapatellar subregion was associated with the higher maximum pain score (adjusted OR (95% CI), 2.8 (1.4 to 5.4) and 3.1 (1.2 to 7.9), respectively).

Conclusions

A comprehensive semiquantitative scoring system for the assessment of whole-knee synovitis is proposed. It is reliable and identifies knees with pain, and thus is a potentially powerful tool for synovitis assessment in epidemiological OA studies.

INTRODUCTION

Synovitis is defined as inflammation of the synovial membrane and is characterised on MRI by thickening and enhancement after administration of intravenous contrast agent. To date, semiquantitative (SQ) assessment of synovitis in large epidemiological studies of osteoarthritis (OA), a disease which is becoming increasingly prevalent,1,2 has usually been performed on MRI without enhancement.3–5 Signal alterations in Hoffa’s fat pad are commonly applied as a surrogate for whole-knee synovitis.6,7 However, an increasing amount of evidence is emerging through recent OA studies showing that the presence and severity of synovitis are ideally assessed with contrast-enhanced (CE) MRI.7–14

In a head-to-head comparison between non-CE and CE-MRI for synovitis assessment,12 agreement between these was only fair to moderate and signal changes in Hoffa’s fat pad on non-CE images did not always represent synovitis, leading to a low specificity of non-CE-MRI compared with CE-MRI as the reference. Furthermore, findings of previous studies by other research groups showed that synovitis scoring based on CE-MRI is associated with synovitis histology9 and pain severity.8

In the past two decades, researchers have developed various quantitative and SQ scoring systems to measure synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis and OA. While quantitative assessment is often preferred for its accuracy and sensitivity to change, it is laborious and time consuming.15 Delineation of synovial tissue is often impaired owing to partial volume averaging and other technical challenges encountered at segmentation.15 Moreover, volume approaches may only reflect the whole-joint synovitis load but usually do not specify the anatomical distribution of synovitis. Current SQ scoring systems commonly grade synovitis at a limited number (between four and six) of locations using axial9,10 or sagittal scans.8 As anatomical distribution of synovitis seems to be heterogeneous,14 a scoring system addressing a larger number of locations is desirable in order to cover the whole joint. Also, the use of a comprehensive approach including all locations of synovitis would permit a more accurate assessment than previous selective approaches of the relation of synovitis with knee pain. It would also allow an examination of whether certain locations of synovitis were more likely than others to be related to pain.

Thus, the objectives were (1) to introduce a comprehensive SQ scoring system for assessment of whole-joint synovitis on CE-MRI covering a wide range of anatomical sites; (2) to demonstrate the reliability of such a scoring system and (3) to test its validity for synovitis severity and knee pain in subjects who have, or are at high risk of, knee OA using two different definitions of synovitis severity.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design and subjects

Subjects were participants in the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST), a prospective study of 3026 people aged 50–79 years with a goal of identifying risk factors for incident and progressive knee OA in a sample either with OA or at high risk of developing disease. Subjects were recruited from two US communities, Birmingham, Alabama and Iowa City, Iowa. Details of subject inclusion, exclusion and recruitment have been described previously.16,17 The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Iowa, University of Alabama, Birmingham, University of California, San Francisco and Boston University Medical Campus, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

For this study, an unselected subset of MOST subjects who volunteered to undergo a 1.5 T CE-MRI of one knee at the 30-month follow-up clinic visit was studied. CE-MRI scans were obtained on one knee only. To choose the knee to study, radiographs were read and the knee with the lower Kellgren–Lawrence (KL) grade was selected to avoid knees with severe OA and likely co-occurrence in these knees of structural features associated with pain. If the grade was the same for both knees, the dominant leg was chosen. The CE-MRI was performed on the same day or within 30 days of non-CE-MRI scans obtained in all MRI eligible subjects in the parent study. For subjects with renal disease, diabetes or over the age of 65, serum creatinine was determined and the glomerular filtration rate calculated before intravenous gadolinium administration. Those subjects with renal insufficiency (glomerular filtration rate <30 ml/min) were excluded from the study.

Radiographs

All subjects underwent weight bearing posteroanterior fixed flexion knee radiography using the protocol by Peterfy et al18 and a plexiglass positioning frame (SynaFlexer) at the 30-month follow-up. A musculoskeletal radiologist (a non-author) and a rheumatologist (DTF), blinded to clinical data, graded radiographs according to the KL grade,19 followed by an adjudication process (by two non-authors and DTF).

MRI acquisition

In the MOST parent study, MR imaging was performed using a 1.0 T extremity-based OrthOne scanner (Oni Inc, Wilmington, Massachusetts, USA) but CE scans were not advisable. Images were acquired using a circumferential extremity coil using fat-suppressed, fast spin echo, proton density-weighted sequence in two planes, sagittal (TR=4800 ms, TE=35 ms, 3.0 mm slice thickness, 0 mm interslice gap, FOV 14×14 cm, matrix 288×192, NEX2); and axial (TR=4700 ms, TE=13.2 ms, 3.0 mm slice thickness, 0 mm interslice gap, FOV 14 cm, matrix 288×192, NEX2) and a short τ inversion recovery sequence in the coronal plane (TR=7820 ms, TE=14 ms, TI=100 ms, 3.0 mm slice thickness, 0 mm interslice gap, FOV 14 cm, matrix 256×256, NEX2).

For the purpose of this study, CE-MRI scans were obtained with 1.5 T system (Siemens MAGNEOM Symphony, Malvern, Pennsylvania, USA) with a circumferential extremity coil. Axial and sagittal fat-suppressed T1-weighted CE sequences were acquired (TR=600 ms, TE=13 ms, 3.0 mm slice thickness, 0.3 mm interslice gap, FOV 16×16 cm, matrix 512×512, ETL 1). Intravenous gadolinium (Magnevist (gadopentetate dimeglumine; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany) or Omniscan (gadodiamide; GE Healthcare, New Jersey, USA)) was administered at a dose of 0.2 ml (0.1 mmol)/kg body weight. Two minutes after completing the injection of the gadolinium, sagittal sequences were obtained followed by the axial sequences. The timing of scanning (2 min after injection) was chosen so that we could visualise the maximal synovial enhancement, and also complete acquisition of images before blurring of the synovitis/effusion borderline occurred owing to effusion enhancement from the periphery.20

MRI interpretation

MRI readings were performed independently by two musculo-skeletal radiologists (AG, FWR), with 9 and 7 years of experience, respectively, in SQ MR assessment of knee OA, after an initial session of training and calibration with 20 test cases that were randomly selected. Synovitis was scored using the axial and sagittal CE-MRI sequence, while effusion and bone marrow lesions were scored using the non-CE-MRI sequences of the parent study. MR images were assessed using eFilm software (version 2.0.0, Merge Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA). Readers were blinded to the subjects’ pain status.

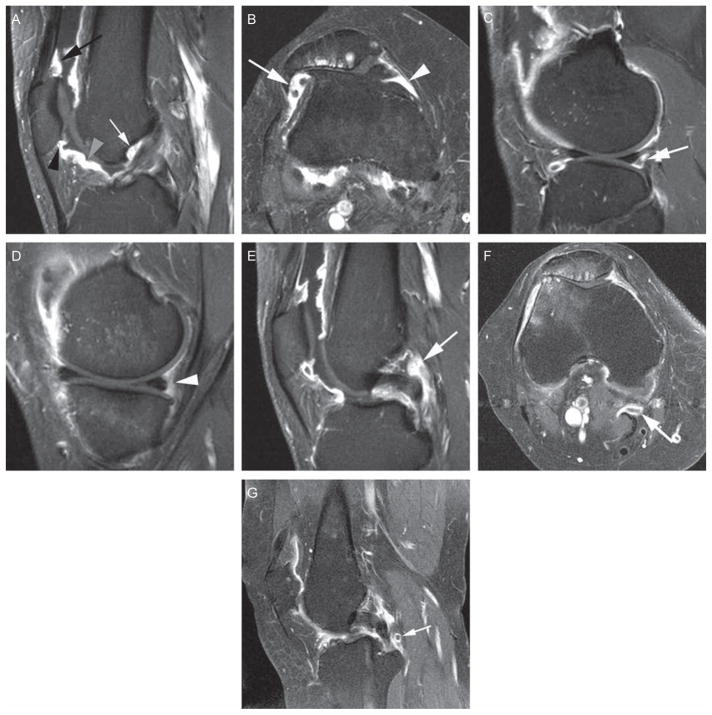

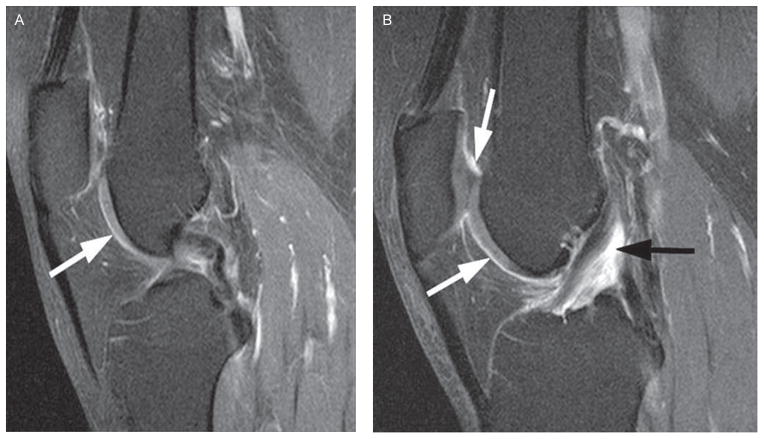

Synovitis was defined as enhancing thickened synovium (>2 mm) and was evaluated at nine sites of the joint—that is, the medial and lateral parapatellar recess, suprapatellar, infrapatellar, intercondylar, medial and lateral perimeniscal, and adjacent to the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (ACL/PCL) in all subjects (figure 1). If knees presented with Baker’s cysts or loose bodies, these two sites were scored in addition. Synovial thickness was scored semiquantitatively based on the maximal thickness in any slice at each site as follows: grade 0 if <2 mm, grade 1 if 2–4 mm and grade 2 if >4 mm (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Eleven anatomical sites evaluated in the proposed scoring system. (A) Sagittal T1-weighted contrast-enhanced (CE) image at the location of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Definition of the suprapatellar site: 0.5–1 cm cranial to the superior patellar pole (black arrow). Definition of infrapatellar site: directly adjacent to the inferior patellar pole (black arrowhead). Definition of the intercondylar site: at the surface of Hoffa’s fat pad 1.5–2 cm distal to inferior patellar pole (grey arrowhead). Definition of ‘adjacent to the ACL’ site: directly anterior to the ACL close to its femoral attachment (white arrow). (B) Axial T1-weighted CE image at the location of the maximum medial-lateral patellar diameter. Definition of the medial parapatellar site: 0.5–1 cm posterior to the medial patellar pole. Definition of the lateral parapatellar site: 0.5–1 cm posterior to the lateral patellar pole. (C) Sagittal T1-weighted CE image at the location of the tibiofibular joint. Definition of the lateral parameniscal site: directly adjacent posterior to the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus (white arrow). (D) Sagittal T1-weighted CE image at the location of the tibial semimembranosus attachment. Definition of the medial parameniscal site: directly adjacent to the posterior horn of the medial meniscus (white arrowhead). (E) Sagittal T1-weighted CE image at the location of the femoral posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) attachment. Definition of ‘adjacent to the PCL’ site: Directly adjacent to the PCL at its mid-portion (white arrow). (F) Axial T1-weighted CE image at the location of the Baker cyst with peripheral enhancement indicating synovitis (white arrow). (G) Sagittal T1-weighted CE image showing a loose body (white arrow), located posteriorly to the PCL, surrounded by enhancing synovitis.

Figure 2.

Semiquantitative synovitis scoring. (A) Grade 0—normal enhancement (<2 mm) of the intercondylar synovium (arrow). (B) Grade 1—enhancement of the suprapatellar and intercondylar synovium (white arrows) and grade 2 enhancement around the anterior cruciate ligament (black arrow).

Knee pain assessment

The 3.0 Likert version of the Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Index(WOMAC)was administered at the 30-month clinic visit. For each of five pain questions subjects rated their pain from 0 (no pain) to 4 (extreme pain). For each subject’s knee, we used their worst pain score on any of the five WOMAC questions as their pain severity. Also at the 30-month clinic visit participants were asked a knee-specific question about frequent knee pain, as follows: “During the past 30 days, have you had pain, aching or stiffness in your knee on most days?”. Positive responses to this question for the knee that had had CE-MRI were considered to indicate presence of frequent knee pain.

Statistical analysis

For assessment of whole-knee synovitis the scores of the 11 sites were summed and categorised: 0–4 normal or equivocal synovitis; 5–8 mild synovitis; 9–12 moderate synovitis and ≥13 severe synovitis. To assess the reliability of the proposed scoring system, inter- and intraobserver reliability for each individual site was calculated using weighted κ statistics on a set of 50 randomly selected MR examinations. Also, the intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated from the same subset of MRI scans to assess inter- and intraobserver reliability for the summed synovitis score.

The association of the summed synovitis scores with the maximum score of five WOMAC knee pain items was assessed using ordinal logistic regression, adjusting for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), MRI bone marrow lesions, MRI effusions and whole-knee radiographic OA status. Knees with no synovitis or equivocal synovitis as defined by the summed scores were used as the reference.

Three different articular anatomical subregions were defined by combining five parapatellar sites (parapatellar subregion), two sites around the ACL and PCL (periligamentous subregion) and two sites around the medial or lateral menisci (perimeniscal subregion), respectively. For these subregions, we did not include the relatively uncommon synovitis within Baker’s cysts and other rare locations. We assessed synovitis severity in two ways: the summed score and the maximum grade in each of these three subregions. For each of these definitions of synovitis severity, we evaluated its association with pain severity defined as the maximum score of five WOMAC knee pain items adjusting for age, sex, BMI, radiographic OA status, MRI bone marrow lesions, MRI effusions and the presence of synovitis in other subregions to account for knees in which synovitis is present in more than one subregion.

In addition, owing to the potential confounding influence of drugs used for pain, separate analyses were carried out for all pain-related analyses excluding subjects (n=96, 24%) taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or other drugs for pain. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 400 subjects were included. The mean age was 58.8±7.0 years, mean BMI 29.5±4.9 kg/m2 and 46% were women. Baker’s cysts were observed in 137 knees, and 45 knees showed evidence of loose bodies.

The weighted κ coefficient of interobserver reliability for the KL readings of the radiograph was 0.79. For MRI readings, intraobserver reliability was excellent for both readers. The weighted κ values for the individual sites were 0.67–1.00 for reader 1 and 0.60–1.00 for reader 2. Interobserver reliability (κ) for the individual sites ranged from 0.67 to 0.92 (table 1). The intraclass correlation coefficient of summed synovitis scores from 11 sites for intrareader reliability was 0.98 (95% CI 0.97 to 0.99) for reader 1, 0.96 (0.91 to 0.98) for reader 2 and the inter-reader reliability was 0.94 (0.88 to 0.97).

Table 1.

Inter- and intrareader agreement for synovitis scoring at individual sites

| Location | Intrareader 1 w-κ (95% CI) |

Intrareader 2 w-κ (95% CI) |

Inter-reader w-κ (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medial parapatellar recess | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 0.70 (0.48 to 0.92) | 0.80 (0.62 to 0.98) |

| Lateral parapatellar recess | 0.80 (0.60 to 0.99) | 0.93 (0.81 to 1.00) | 0.81 (0.63 to 0.99) |

| Suprapatellar | 0.92 (0.81 to 1.00) | 0.63 (0.41 to 0.86) | 0.83 (0.69 to 0.97) |

| Infrapatellar | 0.83 (0.69 to 0.97) | 0.81 (0.60 to 1.00) | 0.78 (0.62 to 0.93) |

| Intercondylar | 0.80 (0.64 to 0.96) | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 0.67 (0.50 to 0.85) |

| Adjacent to PCL | 0.83 (0.69 to 0.97) | 0.60 (0.34 to 0.86) | 0.70 (0.55 to 0.86) |

| Adjacent to ACL | 0.76 (0.53 to 0.96) | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.00) | 0.69 (0.51 to 0.88) |

| Medial perimeniscal | 0.94 (0.84 to 1.00) | 0.74 (0.57 to 0.91) | 0.91 (0.79 to 1.00) |

| Lateral perimeniscal | 0.78 (0.61 to 0.94) | 0.75 (0.53 to 0.96) | 0.67 (0.49 to 0.85) |

| Adjacent to loose bodies | 0.67 (0.10 to 1.00) | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00)* | 0.73 (0.31 to 1.00) |

| Within Baker’s cyst | 0.85 (0.56 to 1.00) | 0.74 (0.26 to 1.00) | 0.92 (0.77 to 1.00) |

Only a few knees scored by reader 2.

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; PCL, posterior cruciate ligament; w-κ, weighted κ.

Based on the summed synovitis scores from 11 sites, 264 (66%) subjects exhibited normal/equivocal synovial enhancement, 76 (19%) had mild synovitis, 38 (10%) had moderate synovitis and 22 (6%) had severe synovitis. Thirty-eight (14%) subjects with no or equivocal synovitis had radiographic OA (KL grade ≥2). Conversely, any synovitis was present in 89 (22%) subjects with no radiographic OA (KL grade ≤1), including nine subjects with severe synovitis (table 2). A linear trend of increasing synovitis grades with higher KL grade was observed (mean score test, p<0.0001).

Table 2.

Association of summed synovitis scores from 11 sites and Kellgren–Lawrence grade of the knee radiograph*

| Whole knee synovitis category (summed score) | Knees, N (%) | Kellgren–Lawrence grade, N (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Normal/equivocal* (0–4) | 264 (66) | 182 (69) | 44 (17) | 21 (8) | 16 (6) | 1 (0) |

| Mild* (5–8) | 76 (19) | 44 (58) | 15 (20) | 9 (12) | 7 (9) | 1 (1) |

| Moderate* (9–12) | 38 (10) | 15 (40) | 6 (16) | 6 (16) | 8 (21) | 3 (8) |

| Severe* (≥13) | 22 (6) | 5 (23) | 4 (18) | 4 (18) | 6 (27) | 3 (14) |

p Value from the mean score test <0.0001, indicating that the more severe the synovitis, the more likely the knees have higher Kellgren–Lawrence grades.

Moderate and severe synovitis showed a significant association with the maximum WOMAC pain score compared with knees with no or equivocal synovitis in the adjusted model (adjusted OR (aOR) for moderate synovitis = 2.8 (95% CI 1.4 to 5.4) and for severe synovitis = 3.1 (1.2 to 7.9)). After excluding subjects taking pain medication, the aOR for moderate synovitis became 2.5 (1.2 to 5.4) and for severe synovitis 2.7 (0.9 to 7.8) (table 3). There was a statistically significant trend between the severity of synovitis and severity of pain, irrespectively of pain medication status.

Table 3.

Association of summed synovitis scores from 11 sites with maximum score of five WOMAC pain items, assessed by ordinal logistic regression model

| Severity of synovitis (summed scores from 11 sites) | Knees, N | Knees with pain, n (%)

|

Adjusted model,* OR (95% CI)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max WOMAC score

|

All subjects (N=400) | Excluding subjects taking pain medicine (N=304) | Subjects taking pain medicine (N=96) | ||||

| 0 (no pain) | 1 (mild) | 2–4 (mod-ext) | |||||

| Normal/equivocal (0–4) | 264 | 130 (49) | 79 (30) | 55 (21) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| Mild (5–8) | 76 | 34 (45) | 25 (33) | 17 (22) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.4) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.5) | 1.2 (0.4 to 3.5) |

| Moderate (9–12) | 38 | 8 (21) | 14 (37) | 16 (42) | 2.8 (1.4 to 5.4) | 2.5 (1.2 to 5.4) | 5.4 (0.9 to 30.7) |

| Severe (≥13) | 22 | 2 (9) | 8 (36) | 12 (55) | 3.1 (1.2 to 7.9) | 2.7 (0.9 to 7.8) | 12.2 (1.2 to 121.1) |

| p Value for trend | – | – | – | – | 0.0076 | 0.036 | 0.023 |

Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, radiographic osteoarthritis status, MRI bone marrow lesions and effusions.

ext, extreme; mod, moderate; ref, reference; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Index.

For the summed synovitis score in the three anatomical subregions, an increased risk of pain was observed for any synovitis (summed score ≥1) in the parapatellar subregion that further increased with more severe synovitis (aOR for mild synovitis = 1.8 (1.1 to 2.9) and for moderate to severe synovitis = 4.9 (2.0 to 12.0), table 4). After excluding subjects taking pain medication, aOR for mild synovitis became 1.7 (1.0 to 3.0) and for moderate to severe synovitis 3.9 (1.4 to 10.8). The same trend was seen in subjects taking pain medication. For the maximum synovitis grade, only grade 2 synovitis in the parapatellar subregion was associated with pain (aOR=4.0 (2.0 to 8.0)), irrespective of pain medication intake. Any synovitis (defined by either summed score or maximum synovitis grade) in periligamentous or perimeniscal subregions was not associated with pain regardless of pain medication status.

Table 4.

Association of maximal scores of five WOMAC pain items and sum of synovitis scores in three subregions on MRI, assessed by ordinal logistic regression model

| Summed synovitis scores in each subregion | Knees, N | Knees with pain, n (%)

|

Multi-adjusted model,§ OR (95% CI)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max WOMAC score

|

All subjects (N=400) | Excluding subjects taking pain medicine (N=304) | Subjects taking pain medicine (N=96) | |||||

| 0 (no pain) | 1 (mild) | 2–4 (mod-ext) | ||||||

| Parapatellar (5 sites) | 0 | 197 | 109 (55) | 50 (25) | 38 (19) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| 1–4† | 158 | 60 (58) | 58 (37) | 40 (25) | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.9)* | 1.7 (1.0 to 3.0) | 1.9 (0.6 to 5.6) | |

| 5–10‡ | 45 | 5 (11) | 18 (40) | 22 (49) | 4.9 (2.0 to 12.0)** | 3.9 (1.4 to 10.8)*** | 16.2 (2.1 to 125.0)**** | |

| Peri-ligamentous (2 sites) | 0 | 157 | 80 (51) | 47 (30) | 30 (19) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| 1–2† | 119 | 51 (43) | 33 (28) | 35 (29) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.5) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.7) | 1.0 (0.3 to 3.0) | |

| 3–4‡ | 124 | 43 (35) | 46 (37) | 35 (28) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.2) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.4) | 0.8 (0.2 to 3.6) | |

| Peri-meniscal (2 sites) | 0 | 256 | 122 (48) | 76 (30) | 58 (23) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| 1–2† | 109 | 45 (41) | 36 (33) | 28 (26) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.0) | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.4) | |

| 3–4‡ | 35 | 7 (20) | 14 (40) | 14 (40) | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.7) | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.7) | 1.7 (0.1 to 23.2) | |

Prepatellar subregion = summed synovitis scores in five sites.

Periligamentous subregion = summed synovitis scores in two sites around ACL and PCL.

Perimeniscal subregion = summed synovitis scores in two sites around medial and lateral menisci.

p=0.021;

p=0.0005;

p=0.0098;

p=0.0077.

Mild synovitis as defined by the summed synovitis score at each subregion.

Moderate to severe synovitis as defined by the summed synovitis score at each subregion.

Multi-adjusted model: summed synovitis in three regions adjusting for each other, also adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, radiographic osteoarthritis status, MRI bone marrow lesions and effusions.

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ext, extreme; mod, moderate; PCL, posterior cruciate ligament; ref, reference; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Index.

DISCUSSION

We introduced a comprehensive SQ scoring system of knee OA covering 11 anatomical sites of the knee joint to improve understanding of the anatomical distribution of synovitis. Other scoring schemes have focused on more limited anatomical coverage of the knee. Excellent inter- and intraobserver reliability was demonstrated, supporting the potential applicability in trials or clinical studies by trained readers. A linear association of the summed synovitis scores with radiographic OA severity was observed for the first time. Results tying synovitis scores with pain suggest that some anatomical sites may be more relevant than others, especially the parapatellar subregion.

To date most SQ scoring systems of synovitis in knee OA have scored synovitis on non-CE images. The WORMS system incorporates synovitis assessment with a combined score of joint effusion and synovitis based on the distension of the synovial cavity.4 The Boston Leeds Osteoarthritis Knee Score uses a surrogate of signal changes in Hoffa’s fat pad to assess severity of synovitis, which has shown good validity for correlations with pain5 but seems to be a non-specific measure when using CE-MRI as the reference.12 A recent report comparing non-CE and CE-MRI with histology showed that only CE-MRI exhibited significant associations with histological features of inflammation.9 Thus, ideally, synovitis in OA should be assessed by CE-MRI, allowing evaluation of synovial enhancement and thickening as well as differentiation of synovium from effusion.14

For rheumatoid arthritis, a comprehensive SQ scoring system for the wrist and the hand synovitis assessment using CE-MRI is available.21 The RAMRIS system is a reliable and validated scoring tool, which describes the core set of specific imaging sequences to be acquired before and after contrast administration, the criteria for scoring of lesions and the standard dose of the contrast agent.21,22

For OA, Rhodes et al10 introduced a SQ system based on CE-MRI assessing synovitis at five parapatellar sites and one site behind the femoral condyles, showing good correlation with more laborious manual segmentation. Although their system is comprehensive, it only scores one site outside the parapatellar region. Although alternative and more time-efficient semiautomated approaches for synovial volume measurements have been suggested, none of them are generally used to differentiate anatomical sites.15 A patchy distribution of synovitis has been reported and this needs to be accommodated by comprehensive SQ assessments.11,14

The scoring system we present is more comprehensive than the method presented by Rhodes et al because it includes five sites in the parapatellar subregion and six sites outside the para-patellar region, enabling assessment of the whole knee joint. Synovitis was present across the five parapatellar sites in all knees, and all sites contributed to the association of pain and synovitis. For each of the parapatellar sites, synovitis scores were higher for knees with pain than for knees without pain. Furthermore, we examined Spearman rank correlation coefficients for the sites and found that they ranged from 0.41 to 0.58 (p<0.0001 at all sites), suggesting that positive scores across these sites were not collinear—that is, that they were each providing information that was independent of the other parapatellar sites. Thus, no parapatellar site was redundant in our analysis, and we believe it is necessary to include all five sites in the proposed scoring system. Given the absence of relation between pain and synovitis other than parapatellar subregions, users of our proposed system may choose to ignore synovitis in other subregions. However, we discourage such a strategy because comprehensive assessment of synovitis covering all areas of the knee is important. For example, there may be consequences for synovitis around the ACL/PCL or menisci that are not yet identified. Moreover, those areas might have potential significance in evaluating reactivity to change and thus have significance in controlled studies. Further studies are needed to evaluate this.

It is also a reliable tool in the hands of trained expert readers. Whether the same reliability can be achieved for non-radiologist readers needs to be shown in additional comparative exercises.

A potential limitation of the proposed scoring system is that a knee can be classified as normal/equivocal (summed score 0–4) according to the summed synovitis score from 11 sites, despite having grade 2 synovitis at one or two individual sites. In this study, such cases were seen in 32/264 (12%) knees. Such knees are certainly not normal and thus should be interpreted as having ‘equivocal whole-knee synovitis’.

Synovial inflammation is regarded as a secondary phenomenon in the OA disease process. It is thought to be triggered by release of detritus from joint structures, including cartilage.23 To phagocytose and eliminate this detritus, macrophages in the synovial lining proliferate, producing a tissue whose lining develops inflammatory features and thickens. In moderate to advanced OA, ligamentous injury, meniscal tears, loose bodies or hyaline cartilage deterioration cause synovial activation. The strong linear association with radiographic OA severity that we observed seems to support this hypothesis as more severe damage to intraarticular structures will be expected with higher grades of radiographic OA.

Synovial inflammation is believed to contribute to pain in patients with knee OA, even though nociceptive fibres are inconsistently present within the synovium.24 Hill et al7 showed that changes over time in Hoffa’s fat pad signal alterations on nonCE-MRI were modestly and directly correlated with changes in knee pain, but not with structural degeneration. Interestingly, the effect of these signal alterations on pain was independent of changes in joint effusion. In a cross-sectional study, the same group found that these alterations were far more common in subjects with knee pain and radiographic OA than those with radiographic OA without pain.6 Our findings suggest an association of synovitis severity with pain based both on the summed and the maximum synovitis scores in the parapatellar subregion.

Our findings provide potential insights into the locations of synovitis which may cause pain in knee OA. Although synovitis around the ACL/PCL is common, synovitis in these locations was not associated with knee pain. Only moderate to severe synovitis in the parapatellar subregions was associated with a higher pain score. In our sample, the most common painful activity generating those scores was climbing stairs, which may be uniquely related to parapatellar inflammation.

A recent study by Baker et al,8 also from the MOST study, examined the relation of synovitis with pain using the scoring system proposed by Rhodes et al10 and found a generally stronger relation with pain than reported here. We believe this difference may be due to the focus of the Rhodes system on parapatellar synovitis, where we found the strongest association with pain.

In summary, we described a comprehensive SQ scoring system for the whole-knee synovitis assessment using CE-MRI. The system suggests scoring of synovitis at 11 anatomical sites, including additional regions of potential relevance that have not been incorporated in other systems. The proposed system shows validity for associations with pain and is highly reliable in the hands of expert readers, making it potentially applicable in large studies including CE-MRI.

Acknowledgments

Funding The MOST Study is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants from the National Institute on Aging to Drs Torner (U01-AG-18832), Nevitt (U01-AG-19069) and Felson (U01-AG-18820). NIH grants AR053161 and K23AR053855.

Footnotes

Competing interests AG is the president of Boston Imaging Core Lab, LLC (BICL), Boston, Massachusetts, a company providing radiological image assessment services. He is a shareholder of Synarc, Inc. and is a consultant to MerckSerono, Facet Solutions and Stryker. FWR, MDC and MDM are shareholders of BICL. None of the other authors have declared any possible conflict of interest.

- Guarantor of integrity of the entire study: AG, FWR, DTF

- Study concepts and design: AG, FWR, DH, JN, YZ, DTF

- Literature research: AG, FWR, DH, MDC, MDM, AK

- Data collection and interpretation: AG, FWR, MDC, MDM

- Statistical analysis: JN, YZ

- Manuscript preparation: AG, FWR, DH, AK

- Manuscript editing: AG, FWR, DH, MDC, JN, YZ, MDM, AK, JAL, GYE-K, KB, LBH, MCN, DTF

- Final approval of manuscript: AG, FWR, DH, MDC, JN, YZ, MDM, AK, JAL, GYE-K, KB, LBH, MCN, DTF

Ethics approval This study was conducted with the approval of the institutional review board at Boston University School of Medicine.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778–99. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<778::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornaat PR, Ceulemans RY, Kroon HM, et al. MRI assessment of knee osteoarthritis: Knee Osteoarthritis Scoring System (KOSS)–inter-observer and intra-observer reproducibility of a compartment-based scoring system. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:95–102. doi: 10.1007/s00256-004-0828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterfy CG, Guermazi A, Zaim S, et al. Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score (WORMS) of the knee in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2004;12:177–90. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunter DJ, Lo GH, Gale D, et al. The reliability of a new scoring system for knee osteoarthritis MRI and the validity of bone marrow lesion assessment: BLOKS (Boston Leeds Osteoarthritis Knee Score) Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:206–11. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill CL, Gale DG, Chaisson CE, et al. Knee effusions, popliteal cysts, and synovial thickening: association with knee pain in osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1330–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill CL, Hunter DJ, Niu J, et al. Synovitis detected on magnetic resonance imaging and its relation to pain and cartilage loss in knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1599–603. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.067470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker K, Grainger A, Niu J, et al. Relation of synovitis to knee pain using contrast-enhanced MRIs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1779–83. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.121426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loeuille D, Rat AC, Goebel JC, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in osteoarthritis: which method best reflects synovial membrane inflammation? Correlations with clinical, macroscopic and microscopic features. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2009;17:1186–92. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhodes LA, Grainger AJ, Keenan AM, et al. The validation of simple scoring methods for evaluating compartment-specific synovitis detected by MRI in knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:1569–73. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loeuille D, Chary-Valckenaere I, Champigneulle J, et al. Macroscopic and microscopic features of synovial membrane inflammation in the osteoarthritic knee: correlating magnetic resonance imaging findings with disease severity. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3492–501. doi: 10.1002/art.21373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roemer FW, Guermazi A, Zhang Y, et al. Hoffa’s Fat Pad: Evaluation on Unenhanced MR Images as a Measure of Patellofemoral Synovitis in Osteoarthritis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1696–700. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Crema MD, et al. Whole-knee synovitis semiquantitatively assessed on T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI is associated with radiographic tibiofemoral osteoarthritis and severe meniscal damage: the MOST study (abstract) Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(Suppl 1):S211. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roemer FW, Javaid MK, Guermazi A, et al. Anatomical distribution of synovitis in knee osteoarthritis and its association with joint effusion assessed on contrast-enhanced MRI (abstract) Arthritis Rheum. 2009;59(Suppl):S72. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fotinos-Hoyer AK, Guermazi A, Jara H, et al. Assessment of synovitis in the osteoarthritic knee: Comparison between manual segmentation, semiautomated segmentation, and semiquantitative assessment using contrast-enhanced fat-suppressed T1-weighted MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:604–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felson DT, Niu J, Guermazi A, et al. Correlation of the development of knee pain with enlarging bone marrow lesions on magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2986–92. doi: 10.1002/art.22851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roemer FW, Zhang Y, Niu J, et al. Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study Investigators. Tibiofemoral joint osteoarthritis: risk factors for MR-depicted fast cartilage loss over a 30-month period in the multicenter osteoarthritis study. Radiology. 2009;252:772–80. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2523082197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterfy CG, Guermazi A, Zaim PF. Non-fluoroscopic method for flexed radiography of the knee that allows reproducible joint-space width measurement (abstract) Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(Suppl):S361. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteoarthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Østergaard M, Klarlund M. Importance of timing of post-contrast MRI in rheumatoid arthritis: what happens during the first 60 minutes after IV gadolinium-DTPA? Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:1050–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.11.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lassere M, McQueen F, Østergaard M, et al. OMERACT Rheumatoid Arthritis Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies. Exercise 3: an international multicenter reliability study using the RA-MRI Score. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1366–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Østergaard M, Edmonds J, McQueen F, et al. An introduction to the EULAR-OMERACT rheumatoid arthritis MRI reference image atlas. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 1):i3–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.031773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aigner T, Sachse A, Gebhard PM, et al. Osteoarthritis: pathobiology-targets and ways for therapeutic intervention. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:128–49. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dye SF, Vaupel GL, Dye CC. Conscious neurosensory mapping of the internal structures of the human knee without intraarticular anesthesia. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:773–7. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260060601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]