Abstract

Family caregiving is a significant rite of passage experienced by family caregivers of individuals with protracted illness or injury. In an integrative review of 26 studies, we characterized family caregiving from the sociocultural perspective of liminality and explored associated psychosocial implications. Analysis of published evidence on this dynamic and formative transition produced a range of themes. While role ambiguity resolved for most, for others, uncertainty and suffering continued. The process of becoming a caregiver was transformative and can be viewed as a rebirth that is largely socially and culturally driven. The transition to family caregiving model produced by this review provides a holistic perspective on this phenomenon and draws attention to aspects of the experience previously underappreciated.

Keywords: integrative review, family caregiving, chronic illness, liminality, rite of passage, qualitative

Approximately 65.7 million adult family caregivers in the United States provide services valued at $450 billion per year (Feinberg, Reinhard, Houser, & Choula, 2011; NAC, 2009). These individuals are considered “informal” caregivers, as opposed to formal, paid caregivers such as nurses. Most large-scale studies of informal caregivers focus on caregiving for the elderly and those with dementia. However, informal caregivers care for diverse populations, including children with chronic illness and disability, cancer survivors, and veterans of the armed forces who suffer visible and invisible wounds of war (Adelman, Tmanova, Delgado, Dion, & Lachs, 2014; NAC, 2009; Tanielian et al., 2013). Family caregivers often love the person they choose to care for, are in a marriage or partnership with that individual, or have a symbiotic attachment to the care recipient that gives them the inspiration to provide necessary help for what is frequently an indeterminate and prolonged period of time.

Family caregiving is recognized as a significant public health problem. While informal caregivers report benefits associated with caregiving (S. L. Brown et al., 2009; Harmell, Chattillion, Roepke, & Mausbach, 2011), the effects of the stress and burden of caregiving on physical, emotional, spiritual, and financial well-being are significant (Feinberg et al., 2011; Stenberg, Ruland, & Miaskowski, 2010; Vitaliano, Zhang, & Scanlan, 2003). Whether the illness course is smooth or rocky, family caregivers for persons facing long-term impact of significant illness or disabling injury are confronted with an altered life course of their own. This experience is characterized by ambivalence and uncertainty. One’s old identity and social status are threatened and a new set of norms, beliefs, and nascent self must be considered.

From a sociocultural perspective, a margin or threshold when an individual has lost one identity and is in the process of reconstructing a new identity that is meaningful to them and to their community is known as liminality (Turner, 1994; van Gennep, Vizedon, & Caffee, 1961). The term has been used in anthropology to describe the experience of tribal members during initiation rites, when the initiate goes through a social transition in a time that is free of typical social structure (Turner, 1994). According to the rite of passage framework proposed by van Gennep (1961), any transition begins with a preliminal period of separation from ordinary or previous social life, followed by a liminal period of undefined duration, and concludes with postliminal period characterized by a re-aggregation to a new state of being. The liminal period is structurally and physically invisible, and the liminal persona is a transitional being, in the process of being initiated into a very different state of life (e.g. married life, adulthood). During the liminal time, the individual exists in a state in which the past is left behind but the future state has yet to emerge.

The lens of liminality has been used to describe the experience of individuals facing critical or life-threatening illness or injury (Blows, Bird, Seymour, & Cox, 2012; Bruce et al., 2014; Johnston, 2011; Mwaria, 1990). Johnston (2011) used the theory of liminality to describe the ambiguity experienced by a single patient recovering from a critical illness who felt marginalized living in a stressful, uncertain space where one cannot plan for the future. Blows et al. (2012), in a narrative review of ten studies of cancer patients, concluded that liminality accurately described the experience of the cancer trajectory. Mwaria (1990) used case study methodology to examine the experience of a comatose patient and family through the perspective of liminality. Mwaria described their experience of feeling socially isolated and ambiguous, as the family lacked a clear understanding of who they were and where they fit into the social structure. Bruce et al. (2014) examined the liminal experiences of 32 individuals living with life-threatening illness (i.e., cancer, kidney disease and HIV/AIDS) and concluded that being present in a liminal space, the “in between,” was pervasive. The experiences described in these four publications are congruent with the “betwixt and between” liminal period described by Turner (1994), when individuals have shed their old identities but have not yet incorporated a new way of being.

While the experience of individuals undergoing the transition into the sick role has been examined as a liminal experience in a very limited way, only one case study mentioned caregivers (Mwaria, 1990), and no reports were found specifically on liminality in the transition into the caregiver role. Cultural influences combine with psychological responses as an individual going through a life change works to construct a new identity. While a great deal of published literature has focused on caregiver burden and distress, the process of assuming the role of a caregiver is not necessarily characterized by long-term suffering. Some caregivers may experience benefits from helping others that may be protective to their health (Littrell, Boris, Brown, Hill, & Macintyre, 2011). A better appreciation of what transitioning family caregivers undergo is needed in order to improve coping and adjustment for those individuals who are suffering as a result of their caregiving experience and to allow for targeted interventions to assist them in maximizing the benefits and minimizing the burden of caregiving.

To extend our understanding of the experience of family caregivers during this time, we considered the anthropologic concept of liminality as a useful framework for exploring the experience of informal caregivers of those with long-term chronic illness and disability. The purpose of this integrative literature review was to synthesize the qualitative literature regarding the transition into the caregiving role as a liminal experience, using Van Gennep’s rite of passage model (1961) and Turner’s definition of liminality (1969) as guides to identify, organize and examine the existing literature.

Methods

An integrative review of the literature, involving synthesis of empirical reports (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005), was conducted to capture a range of evidence on the liminal aspects of the caregiver rite of passage and extend our understanding of liminality as a relevant theoretical framework for the experience of caregiving. Experts in synthesis recommend an overarching theoretical model to organize and integrate data on a particular topic (Cooper, 1998; Patton, 1999). Van Gennep’s (1961) rite of passage schema is the organizing framework for this review. An iterative process was used to reduce, display, and compare data, identifying patterns, themes, and relationships within rite of passage categories and other emergent variables.

Literature Search

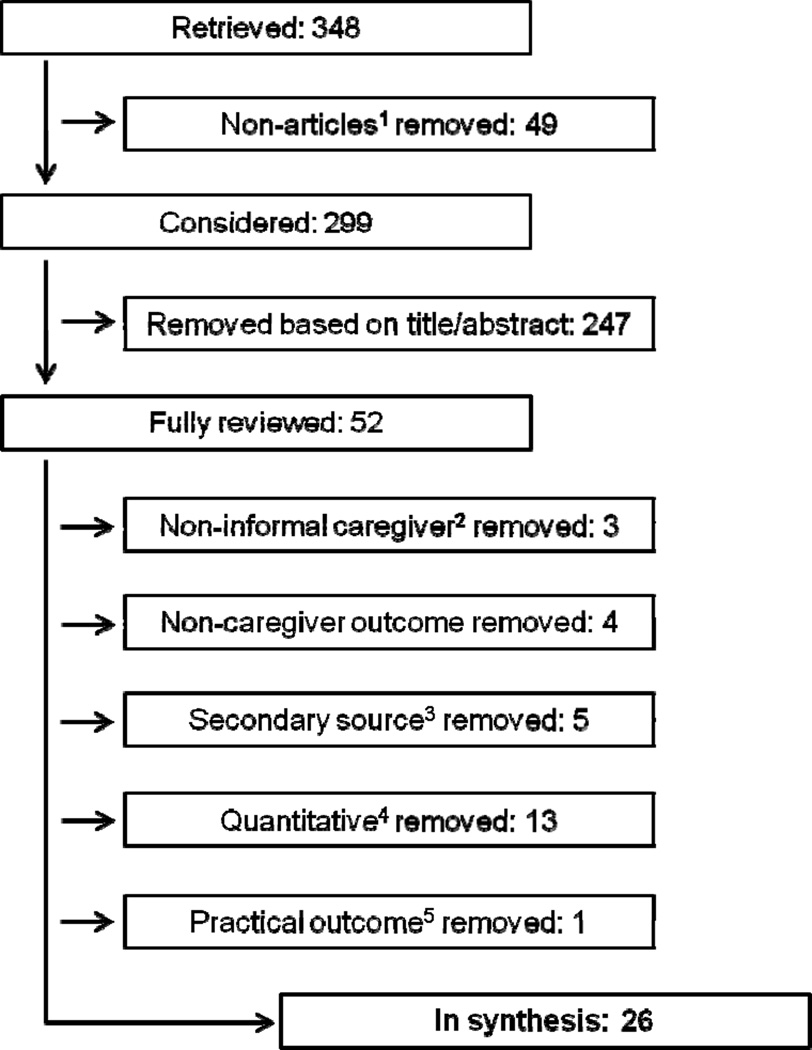

Literature searches were conducted with the assistance of a clinical informationist, using keywords to develop search algorithms in the following databases: National Library of Medicine (PubMed), Scopus ®, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Excerpta Medical Database (EMBASE). Search terms included words for the change the new caregiver experiences (i.e. liminality, rite of passage, uncertainty, life change, ambiguity, transition, and trajectory) and for caregiver (i.e. caregivers, caregiving, caregiver burden) that were connected with AND. PubMed, Scopus®, CINAHL, and EMBASE were searched, and 299 papers remained after duplicates and non-empiric papers were removed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search results for integrative review of liminality in family caregiving.

1 Case reports, commentaries, editorials

2 dissertations/theses, abstracts

3 reviews, summaries

4 interventions

5 educational and process

The researchers limited the sample to qualitative studies because these studies provided the most richness and depth of the caregiving experience. A report was retained for possible inclusion if the focus was on informal caregivers of care recipients suffering protracted illness or injury and if it involved an assessment of the caregivers’ experience. A report was excluded if was a quantitative study, if it was a mixed methods study where the qualitative portion could not be easily separated out, if the focus of the caregiver experience did not involve an informal caregiver, if the focus was exclusively on a specific patient transition (e.g. hospital to home), if the focus was on palliative end of life care, or if it was not published in the English language. In addition, dissertations and theses were excluded. No publication date restrictions were set. The sampling frame was kept narrow and the research designs similar in order to focus narrowly on the liminal experience from the perspective of the caregiver.

Titles and abstracts were reviewed by all team members for adequacy and relevance. Of the 299 articles retrieved, 52 were retained for full article review. Reference lists were not searched because the data retrieved using the search procedure above was adequate to reach saturation of themes and sub-themes.

Data Quality Evaluation

As recommended by Whittemore & Knafl (2005), authors evaluated the quality of the final sample. Because the quality of each study was appraised with the intent to be inclusive rather than exclusive, a standardized mechanism for appraising qualitative studies was not applied (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2006). Two reviewers judged each report’s internal validity using two broad criteria: methodological or theoretical rigor and data relevance. Study quality was judged as acceptable if study findings were rich and complex, as reflected in a higher level of descriptive and interpretive detail regarding the phenomenon of interest (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2006). Studies were deemed relevant if they focused on understanding the experience of the new initiate, the liminal caregiver, and the liminal period – described as uncertainty, ambiguity or changes in boundaries relative to social structure – was easily identified. Of the 52 studies selected for evaluation of the full report based on title and abstract review, 26 were excluded; the 26 remaining reports fulfilled these two criteria.

Data Analysis

Analysis involved classifying and reducing data to a single-page spreadsheet for each source, using comparisons and contrasts to distinguish patterns, themes, variations, and relationships (Glaser & Strauss, 1966; Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). Each report was treated as a unit of analysis, so patterns and relationships within and across data sources could be visualized during interpretation. Patterns, themes and relationships of importance to the liminal caregiver experience, within the context of their rite of passage, were identified and described by evaluating similarities and differences between study findings. Bi-monthly meetings were conducted to discuss articles, extract data, and refine thematic descriptions and interpretations.

Authors returned to Turner’s (1994) and van Gennep’s (1961) descriptions of the phenomena of interest as well as theoretical papers to assist with further interpretation and integration of concepts. Table 1 presents the conceptual and operational definitions of van Gennep’s (1961) rite of passage phases that were developed by the reviewers and used as conceptual classification categories.

Table 1.

Definitions of Phases of a Caregiver’s Rite of Passage (van Gennep, 1960) used in Analysis

| Phase | Conceptual Definition | Operational Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-liminal | A separation from ordinary or previous social life occurs. | This period is marked by entering a life transition with a loved one, partner, friend, or acquaintance that begins with an illness crisis or a disease process that results in the individual assuming a caregiver role for the sick person. |

| Liminal | An unstructured and invisible period when the person is transitional and in the process of being initiated into a very different state of life. | This period is defined by the caregiver’s loss of social connectedness and loss of future while navigating an uncertain and ambiguous illness trajectory. |

| Post-liminal | A period during which an individual experiences a re-aggregation or reincorporation into a new state of being. | During this time, the past and present are integrated to create a new future (a new normal) in spite of the care recipient’s illness. The caregiver’s identity is re-established which may lead to personal growth, seen as self-transcendence and create new meaning and purpose in life. |

Conclusions and Verification

Conclusions were drawn through isolating subgroups of articles, identifying patterns and processes, and relating these to the integrative review findings as a whole. Thematic dimensions were included to adequately describe ranges of these characteristics and provide depth of understanding of the rite of passage experience and the liminal period for new caregivers. Accuracy and confirmability of review results were ensured through maintenance of an audit trail and reviewer consensus (Cooper, 1998; Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

Results

Twenty-six studies were included in this review (Table 2), with a total sample of 635 caregivers (398 females, 237 males). Studies were conducted in a variety of countries: United Kingdom (5), United States (9), with one Korean American Immigrant sample), Australia, (1), Sweden (4), Finland (1), Canada (1), Iran (1), Brazil (1), Italy (1), and Taiwan (2). The illness or event that created the caregiving demand included diagnoses that were made suddenly such as stroke and others that developed insidiously such as Alzheimer’s disease. Other illnesses and events that were represented in the included studies were chronic disease such as, cancer, mental illness, HIV, multiple sclerosis, asthma, and disability along with complex treatments such as heart transplant and bone marrow transplantation.

Table 2.

Description of Studies Included in Integrative Review

| Authors, Year (Country) |

Qualitative Design and Methods |

Purpose | Participants | N | Ages (Minimum- maximum) |

Female (%) |

Data Collection | Themes Supporteda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Adams et al., 2006 (US) |

Descriptive phenomenology Grounded theory |

Describe early experiences with caregiving for someone with mild CI or AD. |

Caregivers of individuals newly diagnosed with mild CI or AD. |

20 | NR | 50 | Semi-structured audio-taped interviews. |

1–7 |

|

Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991 (US) |

Descriptive Grounded theory |

Explore and describe the experience of family members caring for persons with AIDS at home. |

Lovers, spouses, parents of adults, children, siblings, friends with AIDS. |

53 | 22–65 | 34 | Interviews, audio-taped. |

1–7 |

|

Bulley, Shiels, Wilkie & Salisbury, 2010 (US) |

Secondary data analysis Interpretive phenomenology |

Better understand the caregiver’s experience of stroke. |

Spousal caregivers of persons with stroke. |

9 | 50–74 | 44 | Semi-structured questionnaire; interview by neurologic physiotherapist. |

1–6 |

|

Burman, 2001 (US) |

Longitudinal Grounded theory |

Explore phases and management of trajectory of rural stroke survivors and their families. |

Adults 5–6 months after moderate to severe stroke and adult family members most involved in their care. |

13 | 28–85 | 61.5 | Interviews at three separate times. |

1–5, 7 |

|

Buschenfeld, Morris, & Lockwood 2009 (U.K.) |

Longitudinal Interpretive phenomenology |

Investigate experiences of partners of young stroke survivors (under 60 years old) 2–7 years post-stroke. |

Partners of young stroke survivors. |

7 | 49–62 | 43 | Semi-structured interviews |

1–7 |

|

Donnelly, 2001 (Korean-American) |

Descriptive psychological phenomenology (Giorgi) with cultural focus |

Describe and interpret Korean American families’ caregiving experience for mentally ill grown children. |

First-generation Korean-American parent caregivers. |

7 | 42–73 | 71 | In depth tape- recorded interviews conducted in Korean language. |

1–7 |

| Donorfio & Kellet, 2008 (US) |

Descriptive Grounded theory |

Examine filial expectations of caregiving daughters and their frail widowed mothers. |

Mother daughter dyads. | 11 | NR | 100 | Semi-structured individual interviews; theoretical sampling in 2nd half of study. |

1–3, 5,6 |

|

Engstrom & Soderberg, 2011 (Sweden) |

Interpretive descriptive |

Describe transitions experienced by close relatives of people with TBI. |

Female relatives who lived close to a person with TBI. |

5 | 36–76 | 100 | Interviews in the home. |

2,3,5 |

|

Frankowska & Wiechula, 2011 (Australia) |

Descriptive Gadamerian hermeneutics |

To investigate the lived experience of women entering transition into caregiving for their partners. |

Women caregivers to men with physically limiting conditions and illness. |

8 | NR | 100 | Unstructured interviews, textual analysis. |

1–4, 6 |

|

Galvin, Todres & Richarson, 2005 (U.K.) |

Single case study Hermeneutic phenomenology |

Develop insight into how intimate caregiver’s journey can benefit other caregivers facing similar challenges. |

One caregiver of person with AD. |

1 | NR | 0 | A series of interview with this individual. |

1–7 |

|

Greenwood, Mackenzi, Wilson, & Cloud, 2009 (U.K.) |

Descriptive ethnography Longitudinal |

Investigate experiences of informal caregivers of stroke survivors. |

Family caregivers of stroke survivors from one acute and two rehabilitation units. |

31 | NR | 71 | Audio-taped in- depth interviews at discharge, 1 month and 3 months post- discharge. |

1–7 |

|

Harrow, Wells, Barbour, & Cable, 2008 (U.K.) |

Descriptive interpretive |

Explore experiences of male partners of women who had completed treatment for breast cancer. |

Men of wives with non- metastatic breast cancer. |

26 | 30–77 | 0 | One-on-one informal conversational interviews. |

1–7 |

|

Huang & Peng, 2010 (Taiwan) |

Descriptive Grounded theory |

Explore role adaptation process for family caregivers of ventilator dependent patients. |

Caregivers of ventilator dependent family members. |

15 | 22–84 | 60 | One-on-one in- depth interviews. |

2–6 |

|

Liedstrom, Isaksson, & Ahlstrom, 2010 (Sweden) |

Mixed methods Descriptive correlational Content analysis |

Describe quality of life of the next of kin of patients with multiple sclerosis. |

Next of kin of patients with multiple sclerosis.. |

44 | 19–70 | 55 | Interviews and subjective quality of life questionnaire. |

2–7 |

|

Lin, Lin, Lee, & Lee, 2013 (Taiwan) |

Descriptive Content analysis |

Explore lived experience of male spouses of females with breast cancer. |

Male spouses of women with breast cancer |

9 | 31–78 | 0 | Audio-taped and transcribed interviews and field notes. |

2, 4–7 |

|

Murray, Kendall, Boyd, Grant, Highet, & Sheikh, 2010 (U.K.) |

Secondary data analysis Content analysis |

Determine similarities in patterns of social, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing and distress of family caregivers and patients with lung cancer from diagnosis to death. |

Patients with lung cancer and their family caregivers. |

19 | NR | 58 | Data from interviews and field notes, mapped over time from diagnosis to death of patient. |

1–6 |

|

Navab, Negarandeh, & Hamid, 2011 (Iran) |

Descriptive phenomenology |

Understand the experience of family caregivers of persons with AD. |

Iranian caregivers of persons with AD. |

8 | 25–67 | 87.5 | Audio-taped and transcribed interviews |

2–6 |

|

Plank, Mazzoni, & Cavada, 2012 (Italy) |

Descriptive phenomenology |

Explore and understand experience of new informal caregivers during the transition from hospital to home. |

Informal caregivers in Italy. |

18 | 32–76 | 67 | Individual interviews and focus groups. |

2–6 |

|

Rydstrom, Dalheim-Englund, Segesten, & Rasmussen, 2004 (Sweden) |

Descriptive Grounded theory |

Identify influences and characteristics of family relations in families of a child with asthma. |

Mothers of children with asthma aged between 6 and 16 years. |

17 | NR | 100 | Audio-taped in- depth interviews. |

2, 4,5 |

| Sadala, Stolf, Bocchi, & Bicudo, 2003 (Brazil) |

Descriptive phenomenology |

Understand the experience of primary caregivers of heart transplant recipients. |

Caregivers of heart transplant family members. |

11 | 27–55 | 90 | Audio-taped interviews transcribed verbatim. |

1–5 |

|

Sanden & Soderhamn, 2009 (Sweden) |

Single case study Narrative analysis |

Describe and elucidate narrated experiences of a partner of patient with testicular cancer. |

A young woman whose partner had testicular cancer with metastases. |

1 | 21 | 100 | Conversational interview using semi-structured guide with open- ended questions. |

1–6 |

|

Sawatzky & Fowler-Kerry, 2003 (Canada) |

Descriptive Grounded theory |

Describe and classify effects of caregiving on health and wellbeing of urban women who were informal caregivers. |

Female informal caregiverss from a mid- western Canadian city. |

11 | 35–76 | 100 | Two in-depth semi-structured interviews. |

1–7 |

|

Stone & Jones, 2009 (US) |

Descriptive Grounded theory |

Identify sources of uncertainty for adult children of parents with possible AD. |

Children of a parents with possible AD. |

33 | 36–67 | 90 | Semi-structured interviews. |

2–5 |

|

Valimaki, Vehilainen-Julkunen, Pietila, & Koivisto, 2012 (Finland) |

Descriptive Content analysis Longitudinal |

Describe family caregivers’ life orientation during first year after the diagnosis of AD. |

Family caregivers of persons recently diagnosed with AD. |

83 | 41–85 | 73 | Study participant diary over a two- week period and field notes by family members. |

1–7 |

|

Williams, 2007 (US) |

Descriptive Narratives |

Describe dynamics of commitment, expectations, and negotiation for caregivers of patients undergoing BMT. |

Caregivers of patients undergoing BMT. |

40 | NR | 53 | Audiotaped dialogues with open-ended interview questions. |

1–7 |

|

Williams & Bakitas, 2012 (US) |

Descriptive phenomenology |

Explore lived experience of being caregiver for adult with lung or colon cancer. |

Caregivers of adults with lung or colon cancer. |

135 | 18–84 | 67 | Interviews, audio-recorded and transcribed. |

1–7 |

Note. NR, not reported; AD, Alzheimer’s Disease; AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; CI, cognitive impairment; TBI, traumatic brain injury; BMT, blood and marrow transplantation.

- Pivotal event

- Commitment to the care recipient

- Role ambiguity

- Social changes

- Uncertainty regarding future goals and aspirations

- Suffering as a way of life

- Reincorporation and the new normal

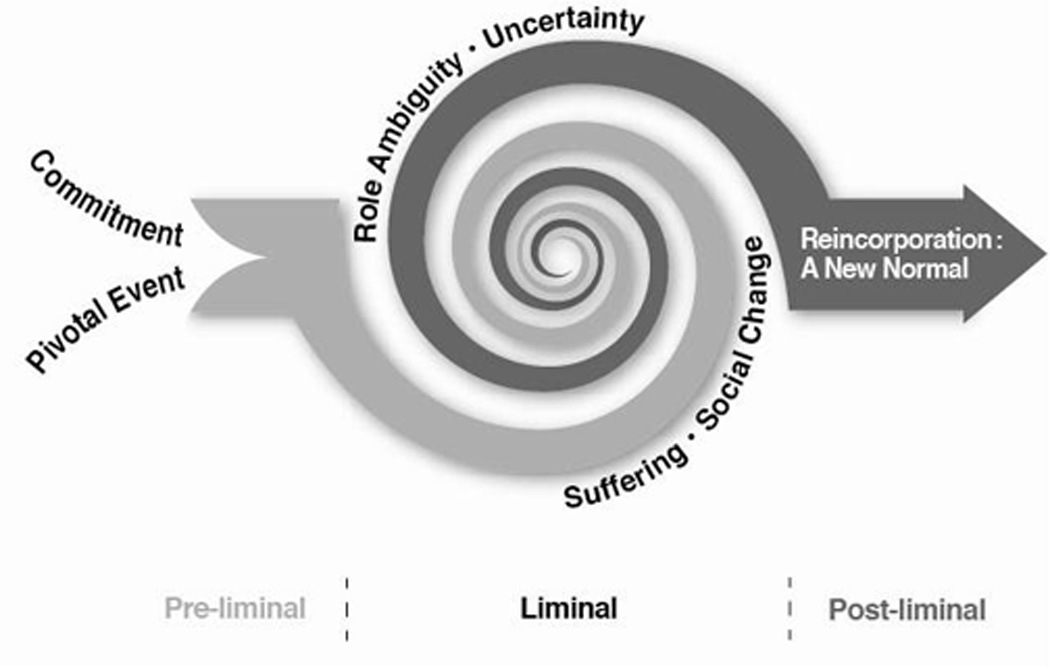

The rite of passage of transition to caregiving is represented in Figure 2. The themes and subthemes of the experience of the caregiver rite of passage for each critical liminal or transitional time are depicted in Table 3 and described below.

Figure 2.

Table 3.

Taxonomy of Categories and Themes Depicting Rite of Passage into Caregiver Role

| Phase | Theme | Sub-Theme (dimensions) |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-liminal | (1) Pivotal event | (a) Recognition of illness or health crisis in a “family” member (Insidious versus abrupt) |

| (2) Commitment to the care recipient | (b) Dedication to a sick “family” member (obligation versus closeness/love) | |

| Liminal | (3) Role ambiguity | (c) Redefining relationship with care recipient (losing a partner versus gaining a role) |

| (d) Redefining relationships with others (being seen as a couple, reconstruct role in the family) | ||

| (e) Possible experience of stigma (perceptions of discrimination) | ||

| (4) Social changes | (f) Taking on new responsibilities (new routines) | |

| (g) Interfacing with health care system (alone or with assistance) | ||

| (h) Reduced participation in life (isolation) | ||

| (5) Uncertainty regarding future goals and aspirations | (i) Unpredictable illness trajectory (i.e. treatment response, recovery, acute changes) | |

| (j) Motivation for caregiving (self-efficacy/empowerment versus lack of enthusiasm) | ||

| (k) Uncertain prognosis (roller coaster of chronic illness versus death) | ||

| (6) Suffering as a way of life | (l) Stress and burden of caring (emotional pain, grief, guilt that leads to negative adaptation) | |

| (m) Makes life “sweeter”, when life is good (positive adaptation, hope, constructing a positive recovery for care recipient) | ||

| (n) Spirituality and self-reflection (finding peace) | ||

| Post-liminal | (7) Reincorporation and the new normal | (o) Role delineation (can change again with institutionalization or death) |

| (p) Uncertainty may continue indefinitely (increases, stays the same, or decreases) | ||

| (q) Suffering may continue indefinitely (burden/stress versus growth/meaning/purpose and transcendence) |

Pre-liminal Phase

Almost all authors addressed the time when participants entered the caregiver role because their loved one, partner, or friend experienced an illness or injury. Two characteristics of the pre-liminal phase were identified: 1) Pivotal event, defined as a significant illness or injury event, and 2) Commitment to the care recipient.

Pivotal event

Caregivers reported an initial sense of shock associated with the recognition of a serious illness state or disability in someone close to them. Moving from the end of one period into another was described by caregivers in metaphorical terms, such as a shattered life (Galvin, Todres, & Richardson, 2005; Sanden & Soderhamn, 2009; A. L. Williams, Bakitas, & McCorkle, 2012). Caregivers reported their lives were turned upside down, and they experienced a sense of turmoil and powerlessness (Adams, 2006; Bulley, Shiels, Wilkie, & Salisbury, 2010; Burman, 2001; Plank, Mazzoni, & Cavada, 2012; Sanden & Soderhamn, 2009). Caregivers recognized the point at which their social position changed (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Bulley et al., 2010; Buschenfeld, Morris, & Lockwood, 2009), and acknowledged a threat to identity and disruption of the familiar status quo as a role change “beyond their control” that was “foisted upon them” (Frankowska & Wiechula, 2011). In diseases with a slow onset, such as Alzheimer’s, the transition might occur as a moment of growing realization that something was terribly wrong (Adams, 2006; Galvin et al., 2005). The actual diagnosis of dementia was described by Valimaki et al. as “blunt…felt terrible.” Regardless of whether the role was thrust upon them or was a chosen path, or whether the family member experienced a disease process of insidious onset or an abrupt injury or health crisis, caregivers embarked on a journey that they remembered well (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Galvin, et al., 2005).

Commitment to the care recipient

Caregivers came to the caregiving experience with a pre-existing relationship with the patient. In a number of the studies, there was a sense of commitment to the patient that was not questioned. These “initiates” dedicated themselves to the care of their family members without a clear understanding of the implications of that commitment (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Donorfio & Kellett, 2006; Sawatzky & Fowler-Kerry, 2003), although the belief or hope remained that they might renegotiate this commitment at some point in the future (Sawatzky & Fowler-Kerry, 2003). Caregivers prioritized the needs of the patient over their own, as exemplified by one participant who said, “You become less important… you start not caring for yourself” (Buschenfeld et al., 2009). Another participant said, “I found my normal life slipping away, but not in a complaining way, just that’s what was happening… I don’t know what normal life is right now. My focus is him” (L. A. Williams, 2007).They viewed the caregiving responsibility as enduring for however long it took (L. A. Williams, 2007). This sense of commitment was experienced regardless of whether the caregiver felt a close or loving relationship to the patient (L. A. Williams, 2007).

Liminal Phase

Most of the authors identified a period of flux when a participant was moving into the caregiver role. Four themes were identified in the liminal phase: 1) role ambiguity, 2) social changes, 3) uncertainty and 4) suffering.

Role ambiguity

Role ambiguity referred to losing one’s identity but not yet incorporating a new identity. Caregivers were challenged to redefine relationships with care recipients as well as others (e.g. family, friends, health care providers), while being “responsible for everything,” often including aspects of the care recipient’s role (Plank et al., 2012). Some caregivers also struggled with the perception of stigma that resulted from caring for someone with an infectious disease like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or an inheritable disorder like Alzheimer’s disease (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Engstrom & Soderberg, 2011; Stone & Jones, 2009). Role ambiguity revolved around being caught between the private world of chronic illness or disability and the public world (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Engstrom & Soderberg, 2011; Galvin et al., 2005; Harrow, Wells, Barbour, & Cable, 2008; Navab, Negarandeh, & Peyrovi, 2012; Stone & Jones, 2009).

Frankowska et al. (2011) found that study participants hesitated to disclose their caregiving role to others, because metaphorically this indicated they had “lost a partner.” By contrast, caregivers who identified themselves as partners, and as a couple, in both their private lives and with health care professionals, were strengthened by this bond and developed a more positive self-concept (Donnelly, 2001; Galvin et al., 2005; Greenwood, Mackenzie, Wilson, & Cloud, 2009; Harrow, et al., 2008; Liedstrom, Isaksson, & Ahlstrom, 2010; Lin, Lin, Lee, & Lin, 2013; Sadala, Stolf, Bocchi, & Bicudo, 2013).

Although many caregivers had difficulty understanding and accepting the changes in their lives (Bulley et al., 2010), others were able to “learn new ways of being in the world” and recognize the need to see their identity in relation to the person they were caring for (Valimaki, Vehvilainen-Julkunen, Pietila, & Koivisto, 2012). Reshaping relations with the care recipient in a way that was mutually gratifying and beneficial resulted in a positive new identity for some (Donorfio & Kellett, 2006; Galvin et al., 2005).

Social changes

The informal caregiver rite of passage led to a change in daily routines, a need to interface with a complex health system, and decreased participation in life (Adams, 2006; Bulley et al., 2010; Burman, 2001; Buschenfeld, et al., 2009; Donorfio & Kellett, 2006; Engstrom & Soderberg, 2011; Frankowska & Wiechula, 2011; Galvin et al., 2005; Plank et al., 2012). Adopting routines enabled a sense of control and predictability that was calming to caregivers, who in turn felt more confident.

Liminal caregivers experienced a reduced participation in life and neglected themselves as they focused on “becoming” (Bulley et al., 2010; Buschenfeld et al., 2009; Donnelly, 2001; Galvin et al., 2005; Liedstrom et al., 2010; Navab et al., 2012; Rydstrom, Dalheim-Englund, Segesten, & Rasmussen, 2004; Sadala et al., 2013). Loss of social connections led to feeling “like a prisoner in your own home” (Valimaki et al., 2012), A reduction in participation in life was dissatisfying for many, who strove to adapt and learn to navigate the “roller coaster” or uncertainty of a chronic illness trajectory (Donorfio & Kellett, 2006; Liedstrom, et al., 2010; Rydstrom, et al., 2004). The challenges inherent in chronic illness care made it necessary to depend on others for guidance and instructions (Galvin et al., 2005; Harrow et al., 2008; Huang & Peng, 2010; A. L. Williams et al., 2012).

Uncertainty

The theme of uncertainty was present in almost every report, as caregivers associated this time with feeling they had no clear future and being unable to plan ahead (Adams, 2006; Burman, 2001; Frankowska & Wiechula, 2011; Galvin et al., 2005; Huang & Peng, 2010; Lin et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2010; Plank et al., 2012; Stone & Jones, 2009). This uncertainty stemmed from their perceptions of the care recipient’s health status, including the illness trajectory as well as prognosis (e.g., risk of death).

However, many caregivers found ways to overcome their perceptions and interpretations (Valimaki, et al., 2012). Embracing uncertainty in chronic illness care, by learning to flow with it and grow with it, was enhanced by previous caregiver experiences and an individual’s motivation to acquire necessary knowledge, skills, and personal or professional help to do the best they could for the care recipient. As one participant noted,

…So I don’t necessarily feel 100% about everything I’m doing, but I have to do it… I’m not 100% positive, 100% sure, … I want to emphasize that you can’t learn what the boundary is, because the boundary of today is not gonna be the boundary of tomorrow. What you’ve got to learn is how to have an antenna. (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991)

Caregivers felt self-assured in their role when they were depended on and had the knowledge and skills to provide necessary care, but they felt less confident when the care recipients’ health declined (Galvin et al., 2005; Greenwood et al., 2009; Liedstrom et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2010). Because of the unpredictable illness trajectory and uncertain prognosis, worried caregivers often recognized the need to “maintain a positive veneer” and, in essence, faked enthusiasm in order to be cheerleaders for their ill family members (Harrow et al., 2008; Liedstrom et al., 2010; A. L. Williams, et al., 2012; L. A. Williams, 2007).

Suffering

Suffering was a theme for most of the caregivers, as the time was characterized by a great deal of psychological pain and upheaval. Caregivers struggled with stress, anxiety, depression and loneliness (Bulley et al., 2010; Donnelly, 2001; Galvin et al., 2005; Murray et al., 2010; Sawatzky & Fowler-Kerry, 2003). Emotional support was in particularly short supply, as caregivers lost touch with friends and the greater community, and in many instances felt as if they no longer could turn to their sick loved ones (Bulley et al., 2010; Buschenfeld et al., 2009; Frankowska & Wiechula, 2011; Galvin et al., 2005; Sadala et al., 2013; Valimaki et al., 2012; A. L. Williams et al., 2012). During this time, there was grief about the loss of their previous life and guilt over attempts to take care of themselves (Donnelly, 2001; Galvin, et al., 2005). Some care recipients’ suffering and symptomatology added to their caregivers’ suffering (Lin et al., 2013; Plank et al., 2012). A participant described a difficult care recipient: “They explained to me that the damage to the brain… was making him do these things… he was so nasty he had me in tears every day” (Bulley et al., 2010).

The trajectory of the suffering was not linear in nature (Harrow et al., 2008); rather, caregivers described the suffering in fluid terms, such as ebbing and flowing (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Bulley et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2010; Rydstrom et al., 2004; Sadala et al., 2013). Adjusting to these swings and finding a balance became a task that had to be mastered (Buschenfeld et al., 2009; Frankowska & Wiechula, 2011).

As suffering became a way of life, many caregivers adapted by recognizing and appreciating when life was good (Valimaki et al., 2012). Positive adaptation strategies included spirituality, self-reflection, and sometimes religiosity as a means to cope (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Donnelly, 2001; Frankowska & Wiechula, 2011; Greenwood et al., 2009; Harrow et al., 2008; Huang & Peng, 2010; Liedstrom et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2010; Navab et al., 2012; Valimaki et al., 2012). Despite the psychological pain and disappointment inherent in chronic illness care, many of the caregivers viewed caregiving as a spiritual time (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Donnelly, 2001; Sadala et al., 2013) that led to new ways of considering themselves, their relationships, and their lives, paving the way for personal growth (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Buschenfeld et al., 2009; Galvin et al., 2005; Greenwood et al., 2009; Sadala et al., 2013).

Variations in the experience of suffering were noted. These included the influence of culture on the expression of suffering in the caregiver-care recipient dyad (Donnelly, 2001; Lin et al., 2013; Navab et al., 2012; Valimaki et al., 2012). Despite their suffering, an altruistic filial commitment was ingrained in some caregivers whose sense of obligation that stemmed from their culturally rooted belief systems (Donnelly, 2001; Donorfio & Kellett, 2006; Lin et al., 2013; Navab et al., 2012; Van Pelt et al., 2007). Other sources of variation in caregivers’ stress and coping included care recipients’ degree of incapacitation due to chronic illness or disability, caregivers’ amount of prior caregiving experience, and the availability and utilization of personal and professional support (Greenwood et al., 2009).

Post-liminal Phase

The post-liminal phase was characterized by Reincorporation – A new normal. Sub-themes included role delineation, the persistence of uncertainty and suffering, and transcendence.

Reincorporation – A new normal

As caregivers passed through the stages of assuming a new identity and social role, they traversed boundaries, “moving backwards and forwards” until they were settled into a “new normal” (Adams, 2006; M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Bulley et al., 2010; Burman, 2001; Donorfio & Kellett, 2006; Harrow et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2013; Navab et al., 2012; Rydstrom et al., 2004; Sadala et al., 2013). Caregivers integrated the past and present in order to move forward in spite of an unpredictable illness trajectory. When normalcy was reached, the disease, such as Alzheimer’s or dementia, “becomes a family member,” incorporated into their sense of self and into their lives (Valimaki, et al., 2012).

Ways in which caregivers were sustained in the caregiver role and successfully coped with chronic uncertainty included “living in the moment”, “retaining a sense of humor”, “remaining hopeful” and “leaving everything up to God” (Huang & Peng, 2010; Van Pelt, et al., 2007). Some caregivers learned to find meaning in the events and their experience, and viewed the world differently (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Buschenfeld et al., 2009; Galvin et al., 2005; Greenwood et al., 2009; Sadala et al., 2013). Acceptance and transcendence were evident in some reports, as one participant shared: “You couldn’t return to where you were… people think that getting better is getting back as you were. She got better but in a different way. We evolved our life in a different way” (Buschenfeld, et al., 2009). Donnelly (2001) found that caregivers transcended their pain in a unique way because an enhanced meaning was attributed to their daily experiences of suffering.

Despite reincorporation, in the course of chronic illness/disability care, the constant threat remained that role delineation in caregiving could change again, due to divorce, institutionalization, or disease recurrence (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Galvin et al., 2005; Murray et al., 2010; Sawatzky & Fowler-Kerry, 2003). In chronic illness care, uncertainty pervaded the entire experience. Although it varied over time, uncertainty (and possibly suffering) might never completely go away (M. A. Brown & Powell-Cope, 1991; Greenwood et al., 2009; Harrow et al., 2008; Murray et al., 2010; Navab et al., 2012; Valimaki et al., 2012).

Discussion

In this integrative review, the transition to family caregiving was characterized as a liminal experience occurring in the phases of a rite of passage (van Gennep et al., 1961). Caregivers universally experienced an event that resulted in the need to respond with a commitment to care for their loved one (pre-liminal phase), followed by a period of transition when life as they previously experienced it, including social roles and relationships; had changed (liminal phase); this period was steeped in uncertainty and suffering. Eventually, caregivers reincorporated the disease or disability into their lives (post-liminal phase), and some even experienced growth and found meaning. These findings add to evidence that caregiving has positive aspects for caregivers that can extend throughout the caregiving trajectory and across populations (Kulhara, Kate, Grover, & Nehra, 2012; Li & Loke, 2013; Mackenzie & Greenwood, 2012), but the model resulting from this analysis also provides a holistic perspective that draws our attention to critical aspects of the experience previously unaddressed in research and clinical practice.

A good deal of quantitative research has focused on the burden and distress of caregiving, and researchers have offered practical, often global, solutions to relieving these (Northouse, Katapodi, Song, Zhang, & Mood, 2010; Thinnes & Padilla, 2011), as opposed to viewing the initiation into caregiving as a life transition with potential for personal and spiritual growth. While interventions and coping strategies have been reported to help informal caregivers with the physical, psychological, and economic stress of transitioning into the role, assessing and assisting with the deeper issue of redefining oneself in the context of a new life trajectory has received little attention to date (Ferrell & Baird, 2012). However, Penrod, Hupcey, Shipley, Loeb, & Baney (2012), in a study of caregiving at the end of life, identified a basic process of “seeking normal” used by caregivers to aim for a steady state in their lives during transitions in the illness of care recipients.

Although this review did not touch upon the intricacies of sacrifices caregivers made that led to burden or stress, it did indicate that most caregivers eventually reincorporated by accepting and adapting to their roles and responsibilities despite the uncertainty and suffering that could continue indefinitely. Some even experienced growth, meaning, and a sense of purpose that led to transcendence, greater wellbeing, and a more fulfilling life (Kulhara, et al., 2012; Quinn, Clare, & Woods, 2010).

it is possible that the liminal time provides health care personnel with teachable moments that are an opportunity to mold the caring experience for both the caregiver and the care recipient by being sensitive to and knowledgeable about the rite of passage caregivers traverse. The liminal phase is a fluid and dynamic time, during which family caregivers are redefining, reconnecting, and trying to navigate a health situation that is foreign to them and is often accompanied by the care recipient’s pain and suffering. That suffering directly influences caregivers’ emotional experiences and may also lead to physical illness. Monin and Schulz (2009) found that watching a sick loved one caused cardiovascular responses that may explain the increased risk of cardiovascular disease in caregiving populations.

Because caregivers may outwardly appear to be functioning well, it is up to nurses and other health care workers to assess coping abilities, ask direct questions, and encourage caregivers to share when they are feeling overwhelmed and need a break from care. Because caregivers may experience guilt about sharing such feelings, it is imperative that, at a minimum, they are told about the universality of their experience and the importance of maintaining their own physical and emotional health, even if it is for the sole purpose of taking better care of their sick or disabled loved ones. Emotional expression is potentially healing; caregivers who spoke using emotion processing words had lower cardiac reactivity than those who used cognitive processing words (Monin, Schulz, Lemay, & Cook, 2012).

Uncertainty and suffering were predominant during the liminal period. In many spiritual and religious traditions, suffering can bring clarity, and its acceptance can bring peace. For example, Buddhists address the concept of “dukkha” or suffering, and modern meditation teachers often paraphrase Buddhist teachings by saying that while pain in life is inevitable, suffering is optional (Kornfield, 2008). Although the pain of watching one’s sick loved one struggle cannot be controlled, the resulting suffering and its negative emotional and physical sequelae can be minimized and possibly prevented. Clearly, many caregivers do adapt and maintain a sense of hope, optimism, and resiliency (Harmell et al., 2011). Caregivers who are struggling should be made aware of resources such as support groups and supportive psychotherapy that may lesson social isolation, anxiety and depression, and of cognitive therapies that encourage reframing of their suffering and improve emotional health.

Like suffering, uncertainty is prevalent in the literature on caregivers’ experience. One caregiver rite of passage involves learning to live with uncertainty, which can be hard to accept, take a long time, and be quite difficult for some. Penrod (2007) determined that uncertainty in illness stemmed from individual meanings and perceptions of the care recipient’s health status, and that it was possible to overcome these perceptions and interpretations. If this is true, perhaps cognitive strategies may also help to reframe caregivers’ perceptions and interpretations of uncertainty and may help them emerge in the post-liminal period functioning at the same, or perhaps a higher level than when they entered into the caregiving role.

Caregivers in the studies examined for this review wanted to be seen not only as integral to the care recipients’ personal lives but as partners in treating and trying to conquer a significant health problem. This desire for partnership may explain the popularity and success of educational interventions for caregivers (Northouse et al., 2010). By helping caregivers learn skills for caring for their family members and by validating this dual role and important partnership, health care workers can facilitate caregivers’ role delineation during the liminal time, helping to lay the groundwork for personal mastery, self-efficacy, and ultimately self-esteem. Problem-focused coping is another means to increase resiliency and empowerment and should be instituted during this formative period (Harmell et al., 2011).

The liminal state is dynamic, fluid, and without clear direction but creates an opportunity for significant growth and personal development (Kelly, 2008; Thompson, 2007). For some, the process of becoming an informal caregiver is transformative and can be viewed as a rebirth that is largely socially and culturally driven (Acton & Wright, 2000; Turner, 1994; van Gennep et al., 1961). Ideally, a return to normalcy is accompanied by psychological well-being and social connectedness that allows life to go on for these caregivers who have adopted a new social status and identity.

While most caregivers move through the experience unscathed, some individuals adopt a new identity that seems plagued by unending uncertainty and suffering. These caregivers are vulnerable if and when another event (e.g., the care recipient’s death or institutionalization) launches a new liminal experience, an occurrence not uncommon in chronic disease or disability. Thus, it is important to identify individuals who are struggling and assist them in identifying and using strategies to find peace in the midst of the chaos. In addition to supportive and cognitive therapies and problem solving interventions, many caregivers found solace in spirituality and religion. Mindfulness strategies such as yoga and meditation may help relieve stress and encourage self-reflection and may help them to find brief respites of peace in the midst of the worry and uncertainty that can extend indefinitely. In some instances, these approaches can provide entry to social communities (e.g. church, yoga groups, etc.) that can provide additional social support.

Seeking social support and engaging in pleasant activities and hobbies are essential to building the resiliency needed to overcome the challenges of long term caregiving (Harmell et al., 2011). Nonetheless, caregivers struggle to participate in programs (Cressman, Ploeg, Kirkpatrick, Kaasalainen, & McAiney, 2013; Robertson et al., 2011), and there may be ethnic and cultural differences in receptivity to spiritual interventions. Future studies are needed to understand the influence of culture and religious beliefs on the caregiving rite of passage.

Limitations

The authors acknowledge that bias and error are potential risks when conducting an integrative review and that relevant studies may have been omitted, affecting the quality of the review and ultimately the presentation of the evidence (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). Additionally, in a qualitative research review, there are gaps between the original study participants’ experiences, the epistemologic stance of the primary study researchers, and the reviewer’s interpretation (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2006). The theoretical orientation of the review informed the decisions made in identifying and combining qualitative studies to achieve the goals of this review.

Conclusion

The caregiving experience is consuming for caregivers, whose life expectations often change dramatically as they progress through the rites of passage. The goal for caregivers during this rite of passage is to minimize stress and burden and maximize personal growth and wellbeing in order to move through the liminal stage and attain a sense of reincorporation and reintegration that is characterized by health and ideally a transcendent position within their group.

The transition to family caregiving model developed in this review provides a unique framework for guiding interactions with caregivers in clinical practice and for developing interventions in research. Nurses can validate caregivers by respecting their contributions and recognizing the valuable contributions they offer their loved ones as well as our society. Nurses and other trusted professionals are positioned to influence and empower caregivers by offering them the permission and resources to care for themselves (Gallup, 2012). By listening to their voices and involving this vulnerable group in action research, we can draw necessary attention to their needs and eventually implement policy change.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Carolyn Bevans, whose scholarly work on van Gennep’s Rite of Passage model and Turner’s liminality concept served as the inspiration for this inquiry, and Stephen Klagholz, for manuscript support and organization.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of the Defense, or the United States government.

Contributor Information

Susanne W. Gibbons, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD.

Alyson Ross, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, Bethesda, MD.

Margaret Bevans, Email: mbevans@cc.nih.gov, National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, 10 Center Drive MSC 1151, Bethesda, MD 20892.

References

- Acton GJ, Wright KB. Self-transcendence and family caregivers of adults with dementia. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2000;18:143–158. doi: 10.1177/089801010001800206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KB. The transition to caregiving: The experience of family members embarking on the dementia caregiving career. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2006;47:3–29. doi: 10.1300/J083v47n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:1052–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blows E, Bird L, Seymour J, Cox K. Liminality as a framework for understanding the experience of cancer survivorship: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2012;68:2155–2164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MA, Powell-Cope GM. AIDS family caregiving: Transitions through uncertainty. Nursing Research. 1991;40:338–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Smith DM, Schulz R, Kabeto MU, Ubel PA, Poulin M, Langa K/M. Caregiving behavior is associated with decreased mortality risk. Psychological Science. 2009;20:488–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce A, Sheilds L, Molzahn A, Beuthin R, Schick-Makaroff K, Shermak S. Stories of liminality: Living with life-threatening illness. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2014;32:35–43. doi: 10.1177/0898010113498823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulley C, Shiels J, Wilkie K, Salisbury L. Carer experiences of life after stroke - A qualitative analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2010;32:1406–1413. doi: 10.3109/09638280903531238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman ME. Family caregiver expectations and management of the stroke trajectory. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2001;26(3):94–99. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2001.tb02212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschenfeld K, Morris R, Lockwood S. The experience of partners of young stroke survivors. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2009;31:1643–1651. doi: 10.1080/09638280902736338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H. Synthesizing research: A guide for literature reviews. 3 ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cressman G, Ploeg J, Kirkpatrick H, Kaasalainen S, McAiney C. Uncertainty and alternate level of care: A narrative study of the older patient and family caregiver experience. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 2013;45(4):12–29. doi: 10.1177/084456211304500403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly PL. Korean American family experiences of caregiving for their mentally ill adult children: An interpretive inquiry. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2001;12:292–301. doi: 10.1177/104365960101200404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donorfio LKM, Kellett K. Filial responsibility and transitions involved: A qualitative exploration of caregiving daughters and frail mothers. Journal of Adult Development. 2006;13:158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Engstrom A, Soderberg S. Transition as experienced by close relatives of people with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2011;43:253–260. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e318227ef9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg L, Reinhard S, Houser A, Choula R. Valuing the invaluable: 2011 update- The growing contributions and costs of family caregiving. AARP Public Policy Institute; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/relationships/caregiving/info-07-2011/valuing-the-invaluable.html. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, Baird P. Deriving meaning and faith in caregiving. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2012;28:256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.008. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankowska D, Wiechula R. Women’s experience of becoming caregivers to their ill partners: Gadamerian hermeneutics. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2011;17(1):48–53. doi: 10.1071/PY10038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup. Honesty/ethics in professions. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/1654/honesty-ethics-professions.aspx.

- Galvin K, Todres L, Richardson M. The intimate mediator: A carer’s experience of Alzheimer’s. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2005;19:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The purpose and credibility of qualitative research. Nursing Research. 1966;15:56–61. doi: 10.1097/00006199-196601510-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood N, Mackenzie A, Wilson N, Cloud G. Managing uncertainty in life after stroke: A qualitative study of the experiences of established and new informal carers in the first 3 months after discharge. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009;46:1122–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmell AL, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, Mausbach BT. A review of the psychobiology of dementia caregiving: A focus on resilience factors. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2011;13:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow A, Wells M, Barbour RS, Cable S. Ambiguity and uncertainty: The ongoing concerns of male partners of women treated for breast cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2008;12:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang TT, Peng JM. Role adaptation of family caregivers for ventilator-dependent patients: Transition from respiratory care ward to home. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19:1686–1694. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LB. Surviving critical illness: A case study in ambiguity. Journal of Social Work in End of Life and Palliative Care. 2011;7:363–382. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2011.623471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A. Living loss: An exploration of the internal space of liminality. Mortality. 2008;13:335–350. [Google Scholar]

- Kornfield J. The wise heart: A guide to the universal teachings of Buddhist psychology. New York, NY: Bantam Random House; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kulhara P, Kate N, Grover S, Nehra R. Positive aspects of caregiving in schizophrenia: A review. World Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;2(3):43–48. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v2.i3.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Loke AY. The positive aspects of caregiving for cancer patients: A critical review of the literature and directions for future research. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2399–2407. doi: 10.1002/pon.3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedstrom E, Isaksson AK, Ahlstrom G. Quality of life in spite of an unpredictable future: The next of kin of patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2010;42:331–341. doi: 10.1097/jnn.0b013e3181f8a5b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HC, Lin WC, Lee TY, Lin HR. Living experiences of male spouses of patients with metastatic cancer in Taiwan. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2013;14:255–259. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littrell M, Boris NW, Brown L, Hill M, Macintyre K. The influence of orphan care and other household shocks on health status over time: A longitudinal study of children’s caregivers in rural Malawi. AIDS Care. 2011;23:1551–1561. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.582079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie A, Greenwood N. Positive experiences of caregiving in stroke: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2012;34:1413–1422. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.650307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monin JK, Schulz R, Lemay EP, Cook TB. Linguistic markers of emotion regulation and cardiovascular reactivity among older caregiving spouses. Psychology and Aging. 2012;27:903–911. doi: 10.1037/a0027418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Grant L, Highet G, Sheikh A. Archetypal trajectories of social, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing and distress in family care givers of patients with lung cancer: Secondary analysis of serial qualitative interviews. BMJ (Online) 2010;340(7761):1401. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwaria CB. The concept of self in the context of crisis: A study of families of the severely brain-injured. Social Science & Medicine. 1990;30:889–893. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90216-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAC. National Alliance for Caregiving. Caregiving in the U.S.; 2009. Retrieved from http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregiving_in_the_US_2009_full_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Navab E, Negarandeh R, Peyrovi H. Lived experiences of Iranian family member caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: Caring as ‘captured in the whirlpool of time’. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012;21:1078–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2010;60:317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research. 1999;34:1189–1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod J. Living with uncertainty: Concept advancement. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;57:658–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod J, Hupcey JE, Shipley PZ, Loeb SJ, Baney A model of caring through end of life: Seeking normal. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2012;34:174–193. doi: 10.1177/0193945911400920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plank A, Mazzoni V, Cavada L. Becoming a caregiver: New family carers’ experience during the transition from hospital to home. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012;21:2072–2082. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.04025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C, Clare L, Woods RT. The impact of motivations and meanings on the wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics. 2010;22:43–55. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J, Hatton C, Wells E, Collins M, Langer S, Welch V, Emerson E. The impacts of short break provision on families with a disabled child: An international literature review. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2011;19:337–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydstrom I, Dalheim-Englund AC, Segesten K, Rasmussen BH. Relations governed by uncertainty: Part of life of families of a child with asthma. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2004;19(2):85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0882-5963(03)00140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadala MLA, Stolf NG, Bocchi EA, Bicudo MAV. Caring for heart transplant recipients: The lived experience of primary caregivers. Heart and Lung: Journal of Acute and Critical Care. 2013;42:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sanden I, Soderhamn O. Experiences of living in a disrupted situation as partner to a man with testicular cancer. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2009;3:126–133. doi: 10.1177/1557988307311289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawatzky JE, Fowler-Kerry S. Impact of caregiving: Listening to the voice of informal caregivers. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2003;10:277–286. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19:1013–1025. doi: 10.1002/pon.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AM, Jones CL. Sources of uncertainty: Experiences of Alzheimer’s disease. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30:677–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian T, Ramchand R, Fisher M, Sims C, Harris R, Harrell M. Military caregivers: Cornerstones of support for our nation’s wounded, ill, and injured veterans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thinnes A, Padilla R. Effect of educational and supportive strategies on the ability of caregivers of people with dementia to maintain participation in that role. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011;65:541–549. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2011.002634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K. Liminality as a descriptor for the cancer experience. Illness, Crisis, & Loss. 2007;15:333–351. [Google Scholar]

- Turner V. Betwixt and between: The liminal period in rites of passage. In: Mahdi L, Foster S, Little M, editors. Betwixt and between: Patterns of masculine and feminine initiation. Peru, Illinois: Open Court Publishing Company; 1994. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Valimaki T, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K, Pietila AM, Koivisto A. Life orientation in Finnish family caregivers’ of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: A diary study. Nursing and Health Science. 2012;14:480–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2012.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gennep A, Vizedon M, Caffee G. The rites of passage. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Van Pelt DC, Milbrandt EB, Qin L, Weissfeld LA, Rotondi AJ, Schulz R, Pinsky MR. Informal caregiver burden among survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2007;175:167–173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-493OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:946–972. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;52:546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AL, Bakitas M, McCorkle R. Cancer family caregivers: A new direction for interventions. Psycho-Oncology. 2012;21:64–65. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LA. Whatever it takes: Informal caregiving dynamics in blood and marrow transplantation. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2007;34:379–387. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.379-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]