Abstract

Objective

The current study examined the relationship between facets of mindfulness, partner-specific anger management, and female perpetrated dating violence. In addition, we examined whether anger management mediated the relation between mindfulness and psychological and physical aggression perpetration.

Method

Female undergraduate students (N = 481) completed self-report measures of mindfulness, partner-specific anger management, and dating violence perpetration.

Results

The mindfulness facets of nonreactivity, act with awareness, and nonjudging, as well as anger management, were associated with dating violence perpetration. After controlling for dating violence victimization, structural equation modeling (SEM) demonstrated that anger management fully mediated the relation between nonreactivity and act with awareness and psychological and physical aggression perpetration. Moreover, specific anger management components (escalating strategies and negative attributions) were largely responsible for the mediation findings.

Conclusions

This is one of the first studies to demonstrate a relation between mindfulness and aggression perpetration, and the first to examine theoretically proposed mechanisms responsible for this relationship. Dating violence prevention programs may benefit from including mindfulness-based interventions to improve anger management and reduce aggressive behavior.

Keywords: Dating violence, intimate partner violence, anger, anger management, mindfulness

Each year approximately 80% of dating college students will perpetrate or be victimized by psychological aggression and 20-30% will perpetrate or be victimized by physical aggression in their dating relationships (Shorey, Cornelius, & Bell, 2008; Taft, Schumm, Orazem, Meis, & Pinto, 2010). It is generally agreed upon that male perpetrated violence is often more severe and has a greater potential to cause physical injuries to female victims (Archer, 2000). In addition, male perpetrated physical and psychological dating violence can result in a number of mental health consequences for female victims (Prospero, 2007). Still, research with college students has demonstrated that females perpetrate as much, if not more, psychological and physical aggression than their male counterparts (Hines & Saudino, 2003; Straus, 2008). Moreover, male victims of dating violence experience a number of negative health consequences, such as depression (Simonelli & Ingram, 1998), substance use (Shorey, Stuart, & Cornelius, 2011), and posttraumatic stress symptoms (Hines, 2007). It should be noted that females also perpetrate dating violence against other females (e.g., Freedner, Freed, Yang, & Austin, 2002), although there is considerably less research on violence among same-sex couples.

Research has also demonstrated that it is more common to find dating college couples in which the female is exclusively violent or to find mutually violent couples, relative to male-only violent couples (Orcutt, Garcia, & Pickett, 2005; Rapoza & Baker, 2008). Research also suggests that males and females may perpetrate dating violence for different reasons, with females more motivated by retaliation and using violence to express feelings (Follingstad, Wright, Lloyd, & Sebastian, 1991; Shorey, Meltzer, & Cornelius, 2010). Moreover, females are more likely to initiate aggression than males in young adulthood (Capaldi, Kim, & Shortt, 2004). Unfortunately, there is minimal research on risk and protective factors for college females’ perpetration of dating violence. Therefore, the current study examined the relation between mindfulness, anger management, and psychological and physical aggression perpetration within a sample of dating female undergraduate students.

Mindfulness

The most well known definition of mindfulness is: “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” (Kabat-Zinn, 1994, p. 4). In essence, mindfulness is a way of “being;” it allows individuals to be more open to experience all thoughts, feelings, and behaviors non-judgmentally and non-defensively (Heppner et al., 2008). Mindfulness helps individuals to regulate their attention in the present moment, decreasing rumination and worry, allowing experiences to naturally come and go without trying to remove any unpleasant emotion or engaging in reactive behavior (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002). It is assumed that mindfulness is a skill or way of being that can be enhanced with appropriate training and practice, which has been supported by a number of studies (see Baer, 2003).

In the current study, we conceptualized mindfulness as containing five distinct facets, first proposed by Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, and Toney (2006). These facets include (1) describing: the ability to put words to one’s thoughts and feelings; (2) act with awareness: the ability to make deliberate and conscious decisions, as opposed to automaticity of behavior without thought or reflection; (3) nonjudging: the ability to accept one’s thoughts and feelings and not judge them as right or wrong; (4) nonreactivity: the ability to view and process emotional stimuli without automatically reacting to the stimuli; and (5) observing: the ability to be aware of and observe stimuli in one’s environments and inner experiences. Previous research has supported the use of these five facets across a variety of samples, including college students (Baer et al., 2009). Research has demonstrated that these facets are unique and certain facets are more strongly associated with specific outcomes. The act with awareness and nonreactivity facets, both characterized by automatic and emotionally-driven behavior, are more strongly associated with destructive behaviors such as alcohol use and impulsivity (Fernandez, Wood, Stein, & Rossi, 2010; Peters, Erisman, Upton, Baer, & Roemer, 2011), whereas the nonjudging facet has been shown to be associated with decreased rumination (Lykins & Baer, 2009).

It should be noted that, empirically, capturing mindfulness has proven difficult, largely due to various definitions in the literature and a disagreement about whether mindfulness is a unidimensional or multidimensional construct (e.g., Brown & Ryan, 2003). However, it is unlikely that a unidimensional approach to conceptualizing and measuring mindfulness will adequately capture this complex construct (Baer, Walsh, & Lykins, 2009). Thus, a multidimensional approach to assessing mindfulness, as used in the current study, may help to disentangle the various aspects of mindfulness that are related to psychological processes.

The existing literature on mindfulness-based interventions has demonstrated its effectiveness for improving health outcomes for individuals with a range mental health and physical illnesses (see reviews by Baer, 2003 and Keng, Smoski, & Robins, 2011). Theoretically, mindfulness-based interventions are believed to promote psychological health by increasing adaptive emotion regulation, self-awareness and acceptance (Baer, 2003). Researchers have also theorized that mindfulness-based interventions would be highly effective for increasing adaptive responses to anger (Borders, Earleywine, & Jajodia, 2010; Wright, Day, & Howells, 2009). Mindfulness interventions may help individuals reduce emotional reactivity, redirect attention to the present moment, and extinguish maladaptive responses previously elicited by anger (Borders et al., 2010; Wright et al., 2009), consistent with the theorized effects of mindfulness on negative emotions in general (Farb et al., 2010).

Mindfulness and Aggression

Only a handful of studies have examined whether mindfulness is associated with aggressive behavior. Heppner and colleagues (2008) found that greater levels of mindfulness were negatively associated with verbal, but not physical, aggression perpetration among male and female college students. Borders and colleagues (2010) demonstrated that mindfulness was negatively associated with both verbal and physical aggression perpetration among college students. Both of the above studies did not distinguish with whom the aggression was perpetrated against. Finally, Gallagher, Hudepohl, and Parrott (2010) found that increased mindfulness was negatively associated with sexual aggression perpetration against a dating partner within a sample of male college students. All of the above studies assessed mindfulness unidimensionally.

In the only study to date that has examined the relation between mindfulness facets and female perpetrated dating violence, Shorey, Larson, and Cornelius and colleagues (In press), using a subsample of the women investigated in the current study, found that the nonreactivity and act with awareness mindfulness facets were negatively correlated with psychological aggression. The nonreactivity facet was also negatively correlated with physical aggression. The mindfulness facets of observing, describing, and nonjudging were not associated with aggression. Theoretically, these findings are consistent with the impulsive and automatic behavior postulated to result from deficits in the nonreactivity and act with awareness mindfulness facets (Baer et al., 2006). However, this study only examined basic associations between mindfulness and aggression (i.e., correlations), and it is possible that deficits in mindfulness lead to other factors that are more strongly associated with dating violence. That is, it is possible that there are factors that may mediate the relation between mindfulness and perpetration. Based on theoretical conceptualizations of mindfulness and likely mechanisms of action in mindfulness-based interventions, as well as existing research on dating violence, anger management may mediate the mindfulness-dating violence relation.

Dating Violence and Anger Management

The existing literature suggests an association between anger and female perpetrated dating violence. Shorey, Cornelius, and Idema (2011) demonstrated that trait anger (a person’s general predisposition to be angry) was positively associated with female perpetrated psychological aggression in dating relationships. Taft and colleagues (2010) found that trait anger was significantly associated with increased psychological and physical aggression perpetration using a combined sample of male and female college students. Moreover, when female college students are asked to report their motivations for perpetrating psychological or physical aggression against their dating partners, state anger (the intensity of anger at a specific moment) is often the most commonly endorsed motive (e.g., Follingstad et al., 1991; Shorey, Febres, Brasfield, & Stuart, 2011).

However, not all individuals who become angry perpetrate dating violence, and it is important to understand the specific anger management deficits that may be responsible for anger escalating into aggression. Toward this end, Stith and Hamby (2002) examined the relation between four types of partner-specific anger management and dating violence among male and female undergraduate students. The four types of anger management they examined were: escalating strategies (behaviors that increase one’s anger toward a partner, such as retaliatory behavior), negative attributions (cognitions of blame and negative intentions attributed to a partner), calming strategies (adaptive strategies for reducing anger, including taking a “time out”), and self-awareness (being aware of the physiological changes produced by anger). Results demonstrated that greater escalating strategies and negative attributions were positively associated with psychological and physical aggression perpetration, whereas greater self-awareness was associated with less aggression perpetration.

Theoretically it is possible that deficits in anger management, including the specific anger management components of escalating strategies and negative attributions, may be a mechanism through which mindfulness is associated with perpetration. It is believed that mindfulness would lead to decreased reactivity to anger eliciting situations (e.g., Wright et al., 2009), which may help to de-escalate conflicts between partners that produce feelings of anger (reduce escalating strategies). The nonjudgmental, present-moment awareness of mindfulness may help to reduce assigning blame or criticizing one’s partner for their faults and mistakes (reduce negative partner attributions). Research has shown that higher levels of mindfulness predict decreased anger and hostility between couples (Barnes et al., 2007) and mindfulness is cross-sectionally associated with reduced anger (e.g., Borders et al., 2010). Moreover, research that has employed mindfulness-based interventions or interventions with mindfulness components, including Dialectical Behavior Therapy, has demonstrated reductions in anger (e.g., Linehan, McDavid, Brown, Sayrs, & Gallop, 2008). Thus, theoretical and empirical evidence provide support for a relation between mindfulness and anger.

Current Study

Based on the theoretical conceptualizations of mindfulness and anger management identified earlier, we examined whether anger management mediated the relation between mindfulness and female dating violence perpetration. It was hypothesized that (1) deficits in the mindfulness, specifically nonreactivity and act with awareness, would be associated with increased psychological and physical aggression perpetration; (2) that partner-specific anger management would be positively associated with mindfulness facets and negatively associated with aggression perpetration; and (3) that anger management, specifically escalating strategies and negative attributions, would mediate the relation between nonreactivity and act with awareness mindfulness and dating violence perpetration.

Method

Participants

A total of 555 female students from introductory psychology classes at a large Midwestern university were recruited for participation. Inclusion criteria for the study required that participants be 18 years of age or older and report at least one dating relationship at some point in their lifetime. Only individuals in a current dating relationship were included in analyses, making the final sample size 481. The average length of participants current relationship was 16.23 months (SD = 15.83) and age was 18.58 years (SD = 1.28). Most participants were freshman at the time of the study (87.7%). The sample was comprised of individuals from the following ethnic backgrounds: 86.2% Caucasian, 6.7% African American, and 7 % “Other” (e.g., Hispanic). The majority of the sample indicated they were heterosexual (94.4%), followed by bisexual (1.9%) and homosexual (1.2%). For those with a bisexual orientation, all indicated their current partner was male. Thus, a very small portion of the sample had the possibility for female-to-female violence. A few participants did not indicate their sexual orientation.

Measures

Dating Violence

The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) was used to assess aggression. In the present study, only the Psychological Aggression (e.g., “Insulted or swore at my partner”) and Physical Assault (e.g., “Pushed or shoved my partner”) perpetration/victimization subscales were examined. Participants were asked to answer questions using a 7-point scale (0 = never; 6 = more than 20 times in the past year). Total scores for each subscale were calculated by adding the midpoint for each item response (e.g., a “4” for the response “3-5 times”), with higher scores representing more frequent aggression. The CTS2 is the most commonly used scale for assessing dating violence and has demonstrated good reliability (e.g., α = .79 to .86) and validity across numerous studies (Straus, 2008). Internal consistency estimates for the current study were .74 (psychological perpetration), .76 (psychological victimization), .79 (physical perpetration), and .81 (physical victimization).

Mindfulness

The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006) was used to examine mindfulness. The FFMQ consists of five subscales: Observation of Experience (“Observe;” e.g., “When I’m walking, I deliberately notice the sensations of my body moving”), Describing with Words (“Describe;” e.g., “I can usually describe how I feel at the moment in considerable detail”), Acting with Awareness (“Act;” e.g., “It seems I am running on ‘automatic pilot’ without much awareness of what I’m doing”), Nonjudging of Experience (“Nonjuding;” e.g., “I make judgments about whether my thoughts are good or bad”), and Nonreactivity to Experience (“Nonreactivity;” e.g., “I watch my feelings without getting lost in them”). Participants were asked to indicate their opinion of how true each item was of themselves (1 = never or very rarely true; 5 = very often or always true). This 39-item measure was developed based on a factor analysis of mindfulness questionnaires and has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Fernandez et al., 2010). Previous studies have demonstrated the internal consistency of the FFMQ to range from .75 (nonreactivity) to .91 (describing) and has supported the factor structure of each facet with undergraduate students (e.g., Baer et al., 2006). The internal consistencies for each facet in the current study were as follows: Observe (α = .82), Describe (α = .88), Act (α =.88), Nonjudging (α = .89), and Nonreactivity (α = .76).

Anger Management

The Anger Management Scale (AMS; Stith & Hamby, 2002) was used to assess the ability to handle anger constructively in participants’ dating relationships. This 36-item scale consists of four subscales: Escalating Strategies (cognitive and behavioral escalating responses to conflict; “When arguing with my partner, I often raise my voice”), Negative Attributions (negative cognitions such as blame or harmful intentions attributed to one’s partner; “It is my partner’s fault when I get mad”), Self-Awareness (level of awareness of changes representing increased anger; “I can usually tell when I am about to lose my temper at my partner”) and Calming Strategies (use of strategies to calm down and deescalate when angry; “I take a deep breath and try to relax when I’m angry at my partner”). Participants were instructed to think of their current dating partner when responding to each item and indicate how much they agreed with each item (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). A total anger management score is calculated by combining the subscales, with a higher total score representing a greater ability to manage anger. The AMS has demonstrated good validity and reliability (e.g., α = .67 to .85) across multiple studies (Lundeberg, Stith, Penn & Ward, 2004; Stith & Hamby 2002). The Self-Awareness subscale has demonstrated lower internal consistency estimates than the other subscales in previous research (Lundeberg et al., 2004; Stith & Hamby, 2002). In the current study, the internal consistencies for the AMS subscales were .89 (Escalating Strategies), .77 (Negative Attributions), .63 (Self-Awareness), and .74 (Calming Strategies).

Procedure

Eligible participants completed all measures through a secure online surveying system that uses encryption to protect the confidentiality of responses. Participants also completed an informed consent prior to study participation, and were awarded “enrichment” credits in their psychology courses for participation. Standardized instructions for all measures were provided, and participants were asked to complete the measures when they were alone and when they had approximately one-hour available. Upon completion, participants were provided with a debriefing form and a list of local resources for domestic violence and mental health.

Data Analytic Strategy

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was conducted using Mplus Version 5.0 to examine the proposed mediation model. The path models were estimated using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIMLE), which does not exclude observations with missing data and uses all available data to estimate parameters (Kline, 2010). In the current study, we had less than 5% missing data, which is an acceptable amount of missing data for FIMLE (Graham, 2003). In addition, robust maximum likelihood estimation was used due to study variables being non-normally distributed (i.e., aggression), as this estimate employs maximum likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors and a chi-square statistic that are all robust to issues of non-normality (Kline, 2010). To test the significance of mediated paths, we employed the bias-corrected bootstrap method. As detailed by MacKinnon, Lockwood, and Williams (2004), the bias-corrected bootstrap method provides a more optimal balance between Type I and Type II error when compared to other methods for testing the significance of mediated paths. Specifically, 500 bootstrap samples and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) were used.

Model fit was evaluated using the chi-square statistic (χ2), the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The chi-square fit index establishes the discrepancy between the sample and the fitted covariance matrices. The chi-square fit index is calculated by dividing the chi-square estimate by the degrees of freedom, with values of less than 2.0 indicative of good fit. The RMSEA is an indicator of model error per degrees of freedom, with values less than .08 indicating that the model fit the data well. The CFI contrasts the estimated model’s fit to that of the null, or “independence” model, with a value of .95 or higher indicative of good fit. The TLI compares a proposed model’s fit to a null or nested baseline model, with values of .90 or greater indicating good fit. Finally, the SRMR is an absolute measure of model fit, which is defined as the difference between the observed and predicted correlations, with values of less than .08 indicating good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). We chose these set of fit indices to examine model fit because they are the most sensitive to models with misspecified factor covariances and loadings (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables. Results demonstrated that psychological aggression perpetration was negatively associated with the mindfulness facets of describing, nonjudging, nonreactivity, and act with awareness. Physical aggression perpetration was negatively associated with the facets of nonreactivity and act with awareness. Psychological and physical aggression were negatively associated with the total anger management score and positively associated with the specific anger management components of escalating strategies and negative attributions. The total anger management score was positively associated with all five mindfulness facets. From the total sample, 81.3% perpetrated psychological aggression and 32.1% perpetrated physical aggression in the previous year.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Psychological Perpetration | --- | .57** | −.05 | −.11* | −.12* | −.19** | −.23** | −.60** | .69** | .51** | .03 | −.12** |

| 2. Physical Perpetration | --- | .05 | −.04 | −.08 | −.09* | −.10* | −.35** | .39** | .33** | −.00 | −.07 | |

| 3. FFMQ Observe | --- | .28** | −.23** | .46** | −.12** | .19** | −.08 | −.03 | .15** | .32** | ||

| 4. FFMQ Describe | --- | .30** | .37** | .32** | .24** | −.17** | −.17** | .07 | .25** | |||

| 5. FFMQ Nonjudging | --- | .00 | .51** | .19** | −.26** | −.22** | −.09* | −.06 | ||||

| 6. FFMQ Nonreactivity | --- | .04 | .37** | −.28** | −.19** | .14** | .39** | |||||

| 7. FFMQ Act with awareness | --- | .22** | −.32** | −.32** | −.18** | −.01 | ||||||

| 8. AMS Total | --- | −.85** | −.65** | .38** | .57** | |||||||

| 9. AMS Escalating strategies | --- | .62** | .05 | −.19** | ||||||||

| 10. AMS Negative attributions | --- | .11* | −.16** | |||||||||

| 11. AMS Calming strategies | --- | 49** | ||||||||||

| 12. AMS Self-awareness | --- | |||||||||||

| Mean (M) | 11.32 | 2.61 | 24.70 | 27.37 | 28.82 | 20.63 | 27.33 | 101.73 | 33.64 | 8.90 | 20.51 | 18.66 |

| Standard Deviation (SD) | 17.69 | 10.28 | 6.24 | 6.25 | 6.61 | 4.73 | 6.27 | 12.59 | 8.48 | 3.14 | 4.30 | 3.04 |

Note: FFMQ = Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; AMS = Anger Management Scale

p < .05

p < .01

Path Models

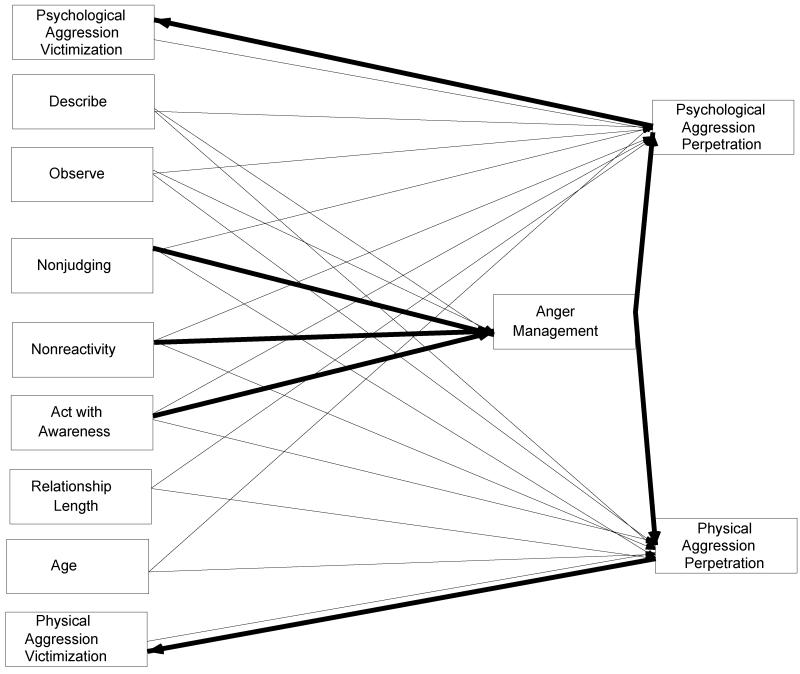

First, we examined the proposed mediation model of mindfulness, anger management, and dating violence perpetration. We controlled for age, relationship length, and dating violence victimization in all models. Victimization was regressed on perpetration, and perpetration regressed on victimization, in the models to account for the bi-directionality of dating violence. We first examined the total anger management score as a mediator of the relation between mindfulness and dating violence. This model is displayed in Figure 1 and the model fit the data well (see Table 2). Covariances and disturbances were included in the model but are not presented in the figure for clarity. Table 3 presents the standardized path coefficients for this model. Findings demonstrated that none of the mindfulness facets were associated with psychological and physical aggression perpetration. However, anger management was negatively and significantly associated with both forms of aggression perpetration. In addition, the nonjudging, nonreactivity, and act with awareness mindfulness facets were associated with anger management. Victimization, age, and relationship length were not related to perpetration.

Figure 1.

The mediating effect of anger management on the relationship between mindfulness facets and dating violence perpetration. Bolded paths were significant at p < .05.

Table 2.

Model fit statistics for mediational models

Table 3.

Standardized path coefficients for the mediating effect of anger management (total score).

| Violence Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Observe ➝ Mediator |

Describe ➝ Mediator |

Nonjudging ➝ Mediator |

Nonreactivity ➝ Mediator |

Act ➝ Mediator |

Psychological Aggression |

Physical Aggression |

|

| Mediator | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| AMS Total | .07 (.11) | .02 (.11) | .14 (.13)* | .33 (.15)*** | .12 (.12)* | −.63 (.29)** | −.29 (.11)* |

|

| |||||||

| Predictor Variables | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| FFMQ Observe | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | .08 (.17) | .08 (.08) |

| FFMQ Describe | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | .05 (.16) | .06 (.08) |

| FFMQ Nonjuding | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | .07 (.18) | −.03 (.09) |

| FFMQ Nonreactivity | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | −.04 (.21) | .00 (.09) |

| FFMQ Act | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | −.09 (.17) | .01 (.08) |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. AMS = anger management scale; FFMQ = five facet mindfulness questionnaire; Act = act with awareness. Standardized coefficients for control variables (age, relationship length, and victimization) are not presented for clarity.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Examination of the indirect effects of mindfulness on psychological aggression perpetration demonstrated that anger management fully mediated the pathway from the nonreactivity, B = −.76, 95% CI [−1.89, −.41], and act with awareness, B = −.22, 95% CI [−.59, −.05] mindfulness facets to psychological aggression perpetration. For physical aggression perpetration, inspection of the indirect effects demonstrated that anger management fully mediated the relation between the nonreactivity, B = −.21, 95% CI [−.63, −.08], act with awareness, B = −.06, 95% CI [−.23, −.02], and nonjudging, B = −.06, 95% CI [−.28, −.01] mindfulness facets and physical aggression perpetration. Although the nonjudging mindfulness facet was not significantly associated with physical aggression at the bivariate level, due to the combined influence of an independent variable and a mediator variable having a different relationship to a dependent variable than either of their individual relations to the dependent variable, it is statistically correct to interpret this mediated path as significant (Hayes, 2009).

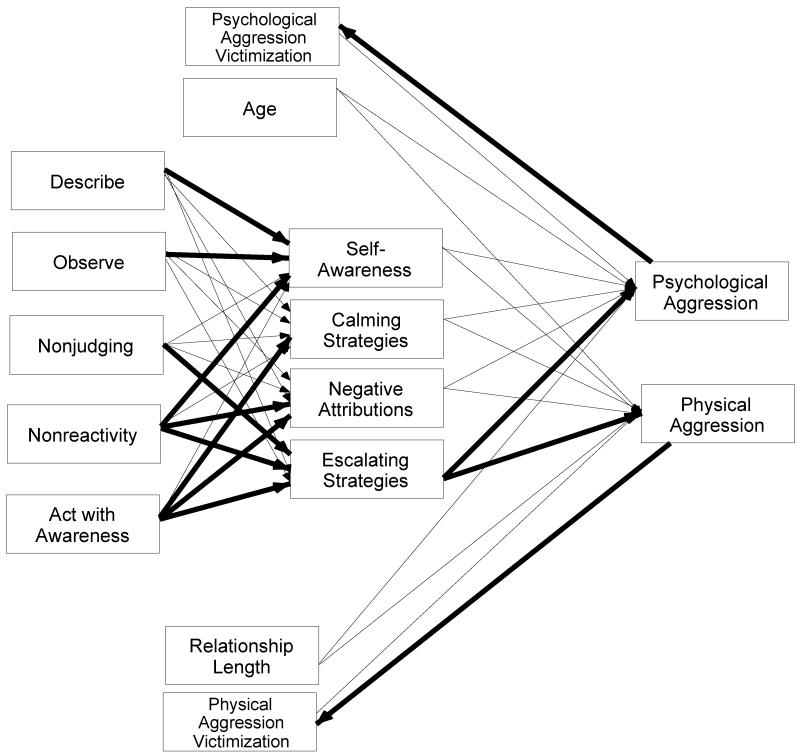

We next examined whether specific anger management components mediated the relation between mindfulness and dating violence. This model is displayed in Figure 2. Covariances and disturbances were included in the model but are not included in the figure for clarity. Results showed that this model fit the data well (Table 2). Table 4 presents the standardized path coefficients for this model. For psychological aggression, mediation analyses demonstrated that the escalating strategies mediated the relation between nonjudging, B = −.27, 95% CI [−.62, −.06], nonreactivity, B = −.57, 95% CI [−1.13, −.31], and act with awareness, B = −.36, 95% CI [−.68, −.19] and perpetration. The negative attributions subscale mediated the relation between nonreactivity, B = −.11, 95% CI [−.39, −.02], and act with awareness, B = −.14, 95% CI [−.46, −.03] and psychological aggression perpetration. For physical aggression, escalating strategies mediated the relation between nonjudging, B = −.06, 95% CI [−.19, −.02], nonreactivity, B = −.12, 95% CI [−.29, −.05], and act with awareness, B = −.08, 95% CI [−.18, −.03] and perpetration. In addition, negative attributions mediated the relation between nonreactivity, B = −.05, 95% CI [−.30, −.01], and act with awareness, B = −.06, 95% CI [−.29, −.01] and physical perpetration. Self-awareness mediated the relation between observe, B = .02, 95% CI [.00, .06], and describe, B = .02, 95% CI [.00, .05] and physical perpetration. It should be noted that although a few predictors were not associated with aggression in the model (i.e., self-awareness; negative attributions), due to the combined influence of an independent variable and a mediator variable having a different relationship to a dependent variable than either of their individual relations to the dependent variable, it is statistically correct to interpret these mediated paths as significant (Hayes, 2009).

Figure 2.

The mediating effect of specific anger management components on the relationship between mindfulness facets and dating violence perpetration. Bolded paths were significant at p < .05.

Table 4.

Standardized path coefficients for the mediating effect of specific anger management components.

| Violence Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Observe ➝ Mediator |

Describe ➝ Mediator |

Nonjudging ➝ Mediator |

Nonreactivity ➝ Mediator |

Act ➝ Mediator |

Psychological Aggression |

Physical Aggression |

|

| Mediators | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| AMS Escalating Strategies | −.05 (.07) | .06 (.07) | −.18 (.08)** | −.26 (.09)*** | −.23 (.08)*** | .57 (.25)*** | .21 (.09)* |

| AMS Negative Attributions | −.01 (.03) | .01 (.03) | −.09 (.03) | −.17 (.04)** | −.28 (.03)*** | .17 (.66) | .13 (.39) |

| AMS Calming-Strategies | .05 (.04) | .09 (.04) | −.02 (.04) | .11 (.06) | −.19 (.04)** | −.05 (.19) | −.11 (.17) |

| AMS Self-Awareness | .13 (.03)* | .13 (.02)* | −.07 (.02) | .28 (.04)*** | −.02 (.03) | .05 (.29) | .08 (.16) |

|

| |||||||

| Predictor Variables | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| FFMQ Observe | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | .07 (.15) | .06 (.08) |

| FFMQ Describe | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | −.00 (.14) | .04 (.09) |

| FFMQ Nonjuding | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | .10 (.16) | −.02 (.08) |

| FFMQ Nonreactivity | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | −.06 (.19) | −.02 (.11) |

| FFMQ Act | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | .01 (.16) | .04 (.09) |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. AMS = anger management scale; FFMQ = five facet mindfulness questionnaire; Act = act with awareness. Standardized coefficients for control variables (age, relationship length, and victimization) are not presented for clarity.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Discussion

A dearth of research has examined the relation between mindfulness and dating violence, with no known studies examining the potential mechanisms behind this relation. The current study examined the relation between mindfulness, anger management, and dating violence perpetration within a sample of female undergraduate students in current dating relationships. We also examined whether partner-specific anger management mediated the relation between mindfulness and dating violence perpetration. Controlling for dating violence victimization, age, and relationship length, findings supported our hypotheses that anger management would mediate the relationship between mindfulness and dating violence.

Consistent with our first hypothesis, findings demonstrated that the mindfulness facets of nonreactivity and act with awareness were negatively associated with aggression perpetration. The describing and nonjudging facets of mindfulness were also negatively associated with psychological aggression perpetration. Theoretically it makes sense that the nonreactivity facet, which refers to one’s ability to view and process emotional stimuli without reacting to the stimuli, and the act with awareness facet, which refers to one’s ability to make deliberate and conscious decisions, as opposed to automaticity of behavior without thought or reflection (Baer et al., 2006), would be associated with perpetration. When one is reactive and acts without awareness, their behavior is likely to be impulsive and based on negative emotions, correlates of violence perpetration (Shorey, Febres, et al., 2011).

Describing and nonjudging were associated with less psychological aggression, but not physical aggression perpetration. If one has a reduced ability to put their thoughts and feelings into words (i.e., the describing facet) they may be more likely to use aggression as a way to express these internal experiences. This would be consistent with research that has demonstrated female perpetrators of psychological aggression report an inability to express their feelings in words (Shorey, Febres et al., 2011). A similar process may be occurring for the nonjudging facet, which may increase anger due to negative judgments about the self, leading to the expression of emotion through verbally aggressive behavior. Thus, it may be that psychological aggression is influenced more heavily by broad deficits in mindfulness. Because psychological aggression occurs frequently, it is plausible that there are more risk factors for this type of aggression.

Mediation analyses demonstrated that partner-specific anger management fully mediated the relation between a number of mindfulness facets and psychological and physical aggression perpetration, consistent with our second hypothesis. That is, mindfulness deficits were associated with deficits in anger management which, in turn, was associated with increased perpetration. Moreover, the escalating strategies and negative attributions anger management subscales showed a prominent role in the relation between mindfulness and aggression, as these subscales mediated the relation between nonreactivity, nonjudging, and act with awareness on physical and psychological aggression perpetration. These anger management components represent cognitive and behavioral processes that increase the level of anger one experiences, which includes ruminating about one’s anger (escalating strategies) and assigning blame and negative intentions to one’s partner (negative attributions). These findings are consistent with the theoretically proposed mechanisms through which mindfulness is believed to influence mental health and behavior, namely through emotion and self-regulation (see Baer, 2003). Although preliminary until replicated, these findings may prove to hold important implications for future research and clinical interventions for dating violence.

It is interesting to note that calming strategies component of anger management was not associated with perpetration, although one adaptive anger management component, self-awareness, did mediate the relation between observing and describing mindfulness facets and physical perpetration. Although adaptive, it is possible that the calming strategies subscale was unrelated to aggression due to individuals scoring high on this component having greater anger tendencies, thus needing to manage their anger more often (Stith & Hamby, 2002). Inspection of the calming strategies items (e.g., “I prefer to get out of the way when my partner hassles me”) may also suggest subtle levels of avoidance of partner conflict. It is possible that these specific calming strategies may have served to avoid aggression in the short-term, but may not have lead to long-term conflict resolution between partners. Additional research is needed to further explore why calming strategies may be unrelated to aggression.

Clinical and Policy Implications

Dating violence prevention programming have had only minimal success at reducing aggressive behavior (Cornelius & Resseguie, 2007). One potential explanation for this minimal success is that a majority of these programs have failed to implement skill-building components into their interventions (e.g., emotion regulation), which may provide participants with the long-term skills needed to remain violence free (Cornelius & Resseguie, 2007). Thus, enhancing specific skills that participants can use across time (i.e., emotion regulation) has been advocated as a new avenue for intervention programs (Shorey, Cornelius et al., 2011). Findings from this study suggest that mindfulness and anger management skills could be targeted in these programs.

There is a wealth of research demonstrating the beneficial effects of mindfulness-based interventions across a wide range of clinical problems and symptoms (see reviews by Baer, 2003 and Keng et al., 2011). However, to date, no studies have examined whether mindfulness-based interventions are associated with reduced aggressive behavior, specifically dating violence. Thus, in light of the current findings and others (e.g., Borders et al., 2010; Gallagher et al., 2010; Heppner et al., 2008), research should determine whether mindfulness-based interventions are effective in reducing dating violence. Prevention programs could follow the outline of the mindfulness based stress reduction program (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 1990) and determine whether this approach reduces aggression, or mindfulness programs could be developed that are specific to dating violence. MBSR has been modified for a number of disorders and problem behaviors, and it seems plausible that researchers could follow these guidelines to develop mindfulness-based dating violence prevention programs.

The current study also lends further support to the notion that anger is an important component of dating violence, suggesting that anger management skills training is also needed in dating violence prevention. The anger management components of escalating strategies, negative attributions, and self-awareness appear to be specific components that would benefit from targeted interventions. Mindfulness-based interventions could be beneficial in reducing anger and/or in regulating anger responses. Wright and colleagues (2009) discuss how mindfulness could be used to reduce anger problems, and that mindfulness may reduce the emotional reactivity produced by anger due to an enhanced ability to sustain non-judgmental, present moment attention and awareness. However, other approaches to increasing anger management skills could also be implemented, including cognitive-behavioral interventions that have shown effectiveness in reducing anger (see review by Del Vecchio & O’Leary, 2004).

Research Implications

The current study is an initial step toward understanding the potential mechanisms through which mindfulness may be associated with dating violence perpetration. Continued research is needed to further explore the mindfulness-dating violence link and potential mediating and moderating variables of this relation. Because mindfulness is theoretically proposed to lead to an increased ability to regulate emotions and tolerate distress (Baer, 2003), it is plausible that emotion regulation and/or distress tolerance, broadly defined, could also mediate the relation between mindfulness and dating violence.

Similarly, specific mental health problems, such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder, which are both associated with increased aggressive behavior (e.g., Taft et al., 2010), may also help to explain the association between mindfulness, anger management, and aggression. Research has demonstrated that alcohol use and mindfulness interact to predict male perpetrated sexual aggression (Gallagher et al., 2010), and research could examine whether alcohol use, a robust correlate of dating violence perpetration, interacts with mindfulness to predict female aggression. Mindfulness has also been conceptualized by researchers in number of ways, including as a single facet, as including two facets, and five. Future investigations should examine whether the conceptualization of mindfulness as a single, dual, or multiple facet construct impacts its relation to dating violence.

Our use of a college student sample of females raises the possibility that our findings may be unique to this stage of development. That is, our sample of primarily first year college students represents a population that has frequent shifts in dating partners, which may impact their risk for dating violence and motivations for it differently than populations with more stable relationships. Thus, future research should examine how developmental factors influence the relation between mindfulness, anger management, and aggression. In addition, research should examine the relation between mindfulness and aggression in samples of men and treatment seeking populations. Finally, researchers could consider the possibility of developing randomized clinical trials of mindfulness interventions for dating violence, evaluating whether mindfulness may be an effective treatment for reducing aggression.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to the current study. The cross-sectional design limits the determination of causality among variables. Our use of a sample of undergraduate females who were primarily non-Hispanic Caucasian in ethnicity limits the generalizability of study findings, and future research should employ more diverse samples, including men. The CTS2 is the most widely used measure for assessing dating violence, although there are numerous measures of mindfulness in addition to the FFMQ. Future research should determine whether findings with mindfulness, anger management, and dating violence vary depending on the specific facets and measures of mindfulness examined. The internal consistency for the AMS Self-Awareness subscale was low, consistent with previous research. Finally, social desirability may have affected responses due to the sensitive nature of study questions.

Conclusions

Findings from the current study demonstrated that anger management fully mediated the relation between the nonreactivity and act with awareness mindfulness facets and psychological and physical dating violence perpetration, as well as the relation between the nonjudging mindfulness facet and physical perpetration. This is the first study to examine the potential mechanisms between mindfulness and female perpetrated dating violence, and these findings may have important implications for female dating violence prevention. Focusing on mindfulness in dating violence prevention programming may help improve anger management and other self-regulation processes, reducing the risk of aggression.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by grant F31AA020131 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) awarded to the first author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:125–143. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/bpg015. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13:27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Walsh E, Lykins ELB. Assessment of mindfulness. In: Didonna F, editor. Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness. Springer; New York: 2009. pp. 153–171. [Google Scholar]

- Baker CR, Stith SM. Factors predicting dating violence perpetration among male and female college students. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma. 2008;17:227–244. doi: 10.1080/10926770802344836. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S, Brown KW, Krusemark E, Campbell WK, Rogge RD. The role of mindfulness in romantic relationship satisfaction and responses to relationship stress. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2007;33:482–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00033.x. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders A, Earleywine M, Jajodia A. Could mindfulness decrease anger, hostility, and aggression by decreasing rumination? Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36:28–44. doi: 10.1002/ab.20327. doi: 10.1002/ab.20327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Shortt JW. Women’s involvement in aggression in young adult romantic relationships: A developmental systems model. In: Putallaz M, Bierman KL, editors. Aggression, Antisocial Behavior, and Violence Among Girls: A Developmental Perspective. Guilford Publications; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 223–241. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius TL, Resseguie N. Primary and secondary prevention programs for dating violence: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2007;12:364–375. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2006.09.006. [Google Scholar]

- Del Vecchio T, O’Leary KD. Effectiveness of anger treatments for specific anger problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:15–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.006. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farb NA, Anderson AK, Mayberg H, Bean J, McKeon D, Segal ZV. Minding one’s emotions: mindfulness training alters the neural expression of sadness. Emotion. 2010;10:25–33. doi: 10.1037/a0017151. doi:10.1037/a0017151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez AC, Wood MD, Stein LAR, Rossi JS. Measuring mindfulness and examining its relationship with alcohol use and negative consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:608–616. doi: 10.1037/a0021742. doi: 10.1037/a0021742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad DR, Wright S, Lloyd S, Sebastian JA. Sex differences in motivations and effects in dating violence. Family Relations. 1991;40:51–57. doi:10.2307/585658. [Google Scholar]

- Freedner N, Freed LH, Yang W, Austin SB. Dating violence among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: Results from a community survey. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:469–474. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00407-x. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00407-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher KE, Huderpohl AD, Parrott DJ. Power of being present: The role of mindfulness on the relation between men’s alcohol use and sexual aggression toward intimate partners. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36:405–413. doi: 10.1002/ab.20351. doi: 10.1002/ab.20351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW. Adding missing-data-relevant variables to FIML-based structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2003;10:80–100. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM1001_4. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation in the new millennium. Communicaiton Monographs. 2009;76:408–420. doi:10.1080/03637750903310360. [Google Scholar]

- Heppner WL, Kernis MH, Lakey CE, Campbell WK, Goldman BM, Davis PJ, Cascio EV. Mindfulness as a means of reducing aggressive behavior: Dispositional and situational evidence. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34:486–496. doi: 10.1002/ab.20258. doi: 10.1002/ab.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA. Posttraumatic stress symptoms among men who sustain partner violence: An international multisite study of university students. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2007;8:225–239. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.8.4.225. [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA, Saudino KJ. Gender differences in psychological, physical, and sexual aggression among college students using the revised conflict tactics scales. Violence and Victims. 2003;18:197–217. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.2.197. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling – A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of your Mind to Face Stress, Pain and Illness. Dell Publishing; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go, there you are. Hyperion; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Keng S, Smoski MJ, Robins CJ. Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: A review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:1041–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, McDavid JD, Brown MZ, Sayrs JH, Gallop RJ. Olanzapine plus dialectical behavior therapy for women with high irritability who meet criteria for borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:999–1005. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundeberg K, Stith SM, Penn CE, Ward DB. A comparison of nonviolent, psychologically violent, and physically violent male college daters. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:1191–1200. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269096. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykins ELB, Baer RA. Psychological functioning in a sample of long-term practitioners of mindfulness meditation. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;23:226–241. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.23.3.226. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt HK, Garcia M, Pickett SM. Female-perpetrated intimate partner violence and romantic attachment style in a college student sample. Violence Victims. 2005;20:287–302. doi: 10.1891/vivi.20.3.287. doi:10.1891/vivi.20.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JR, Erisman SM, Upton BT, Baer RA, Roemer L. A preliminary investigation to the relationships between dispensational mindfulness and impulsivity. Mindfulness. 2011;2:228–235. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0065-2. [Google Scholar]

- Prospero M. Mental health symptoms among male victims of partner violence. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2007:1. doi: 10.1177/1557988306297794. doi: 10.1177/1557988306297794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoza KA, Baker AT. Attachment styles, alcohol, and childhood experiences of abuse: An analysis of physical violence in dating couples. Violence and Victims. 2008;23:52–65. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.1.52. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.23.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonelli CJ, Ingram KM. Psychological distress among men experiencing physical and emotional abuse in heterosexual dating relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1998;13:667–681. doi: 10.1177/088626098013006001. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Brasfield H, Febres J, Stuart GL. An examination of the association between difficulties with emotion regulation and dating violence perpetration. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2011;20:870–885. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2011.629342. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2011.629342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Cornelius TL, Bell KM. A critical review of theoretical frameworks for dating violence: Comparing the dating and marital fields. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.003. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Cornelius TL, Idema C. Trait anger as a mediator of difficulties with emotion regulation and female-perpetrated psychological aggression. Violence and Victims. 2011;26:271–282. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.26.3.271. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.26.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Larson EE, Cornelius TL. An initial investigation of the relation between mindfulness and female perpetrated dating violence. Partner Abuse. doi: 10.1037/a0033658. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Meltzer C, Cornelius TL. Motivations for self-defensive aggression in dating relationships. Violence and Victims. 2010;25:662–676. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.662. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Stuart GL, Cornelius TL. Dating violence and substance abuse in college students: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2011;16:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2011.08.003. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Hamby SL. The anger management scale: Development and preliminary psychometric properties. Violence and Victims. 2002;17:383–402. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.4.383.33683. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.4.383.33683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:252–275. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.10.004. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Schumm J, Orazem RJ, Meis L, Pinto LA. Examining the link between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and dating aggression perpetration. Violence and Victims. 2010;25:456–469. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.4.456. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.4.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S, Day A, Howells K. Mindfulness and the treatment of anger problems. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2009.06.008. [Google Scholar]