Abstract

Bestatin, a specific inhibitor of metalloaminopeptidases, inhibits the growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis. To identify its target enzyme, a library of fluorescent substrates was used but no metalloaminopeptidase activity was found. All aminopeptidase activity of P. gingivalis was bestatin-insensitive and directed exclusively toward N-terminal arginine and lysine substrates. Class-specific inhibitors and gingipain-null mutants showed that gingipains were the only enzymes responsible for this activity. The kinetic constants obtained for Rgps were comparable to those of human aminopeptidases but Kgp aminopeptidase activity was weaker. This finding reveals a new role for gingipains as aminopeptidases in degradation of proteins and peptides P. gingivalis.

Periodontitis is one of the most prevalent bacteria-driven, chronic inflammatory disease in humans and is a major cause of tooth loss. Further, a growing body of evidence shows a clinical link between periodontitis and systemic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease (Humphrey et al., 2008), rheumatoid arthritis (de Pablo et al., 2009), premature birth, diabetes, and Alzheimer disease (Kamer et al., 2008a; Kamer et al., 2008b). Among the 500 bacteria species detected in periodontal plaque, Porphyromonas gingivalis is considered to be one of the main etiologic agents responsible for the development and/or progression of the disease (Paster and Dewhirst, 2009; Socransky et al., 1998). This Gram-negative, anaerobic bacterium produces a variety of virulence factors including an array of proteolytic enzymes (Lamont and Jenkinson, 1998). These enzymes control important physiological functions in P. gingivalis and play multiple roles in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Such proteases act to hydrolyse a variety of serum and structural proteins of the host which contributes to neutralisation of the host immune response and tissue destruction (Guo et al., 2010).

At least 85% of the total proteolytic activity exerted by various strains of P. gingivalis is attributable to three cysteine proteases, collectively referred to as gingipains: two arginine-specific gingipains of low and high molecular weight, RgpB and HRgpA, respectively; and a lysine-specific gingipain, Kgp (Potempa et al., 1997). The remaining 15% of the total proteolytic activity is related to a large array of proteases, including collagenase, streptopain-like enzymes, oligopeptidase, various di- and tri-peptidyl aminopeptidases and carboxypeptidase (Lamont and Jenkinson, 1998). Interestingly, bestatin, isolated from Actinomycetes, is a specific inhibitor of metalloaminopeptidases and has been shown to inhibit the growth of P. gingivalis (Grenier and Michaud, 1994). However, its target enzyme, which is apparently essential for P. gingivalis proliferation is unknown.

A collection of fluorogenic substrates was used to detect and initially characterize the aminopeptidases produced by P. gingivalis. This extensive, 82-member library is composed of 19 proteinogenic and 63 non-proteinogenic moieties coupled to the fluorophore 7-amino-4-carbamoylmethylcoumarin (ACC), using solid phase chemistry (the complete composition of the library and its synthesis is described in (Drag et al., 2010; Zervoudi et al., 2011)). They range in size and the diversity of synthetic compounds within this collection represents a large majority of possible substrate specificities of aminopeptidase enzymes.

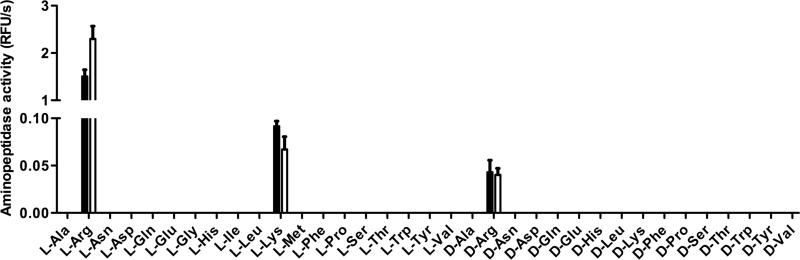

The library was screened using P. gingivalis W83 strain. Whole culture and cell extracts prepared by sonication were examined to identify potential extracellular, cytosolic, membrane-associated or soluble forms. Among the 82 substrates screened, only three were hydrolysed, indicating a narrow specificity of P. gingivalis aminopeptidase activity (Figure 1). The predominant proteolytic hydrolysis observed was for substrate L-Arg-ACC, whereas hydrolysis of D-Arg-ACC and L-Lys-ACC was approximately 30 times weaker. Interestingly, the level of aminopeptidase activity in the whole culture with intact cells was found to be similar to the level of activity in the cell membrane fraction, suggesting that the implicated enzyme(s) was associated with the outer-membrane and cell surface. In order to characterise the enzyme(s) responsible for hydrolysis of the three identified substrates, a protease inhibitor profile was obtained using a combination of class-specific proteases inhibitors.

Figure 1. Screening of P. gingivalis aminopeptidase activity using a fluorogenic substrate library.

The presence of aminopeptidase activity in P. gingivalis was assayed using a collection of 82 fluorogenic substrates as previously described (Drag et al., 2010; Zervoudi et al., 2011). P. gingivalis strain W83 was grown in enriched trypticase soy broth medium (eTSB) at 37°C, in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, USA) with an atmosphere of 90% N2, 5% CO2 and 5% H2. Aminopeptidase activity in whole culture (black bars): A 20 μl aliquot of bacteria culture, collected at early stationary phase and adjusted to an OD600 of 1.5, was incubated 10 min at 37°C, in 50 mM Phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, in a 96-well plate (Nunc A/S, Roskilde, Denmark). Aminopeptidase substrate was then added (50 μM) and the fluorescence release (λexc = 380 nm; λem = 460 nm) was followed using a spectrofluorimeter plate-reader, SpectraMax M5 (Molecular Devices). Aminopeptidase activity in cellular fraction (white bars): Bacteria were collected from 10 ml of early stationary phase culture adjusted to an OD600 of 1.5 by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 10 min). The cell pellet was washed once with PBS, resuspended in 10 ml of 50 mM Phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and ultrasonicated in an ice-water bath using 10 × 5-sec pulses (17 W per pulse) with a 2-sec rest between each pulse. A 20 μl aliquot was used to determine proteolytic activity, as described previously. For clarity, only results obtained for natural L- and D- amino-acid derived substrates are shown. No activity was observed for the other substrates tested. N=3 +/- SD

To screen for metalloaminopeptidase activity, metal-chelating reagents were used. Treatment with 1,10-phenanthroline reduced the enzymatic turnover of the three identified substrates; but even at a concentration as high as 10 mM, the rate of hydrolysis was still high. Treatment with EDTA slightly diminished the activities of enzymes specific for substrates L- and D-Arg-ACC (Table I) only. Accordingly, the metalloaminopeptidase inhibitors bestatin, amastatin, and apstatin showed no effect on activity. Likewise, aspartate-protease inhibitor pepstatin and serine-protease inhibitor AEBSF did not affect cleavage of the substrates. By contrast, broad-spectrum cysteine-protease inhibitors E-64 (1 mM) and TLCK (10 μM) exerted a strong inhibitory effect on aminopeptidase activity, independent of the substrate used. Interestingly, leupeptin, which selectively inhibits Rgps, but does not affect Kgp activity (Pike et al., 1994), totally inhibited hydrolysis of L- and D-Arg-ACC, but failed to block proteolysis of L-Lys-ACC. Based on this inhibition profile and the high specificity for arginine and lysine, it was hypothesised that the gingipains were responsible for the hydrolysis of the three identified aminopeptidase substrates.

Table I.

Characterization of the aminopeptidase activity of P. gingivalis

| Residual activity (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitors | Concentration | L-Arg-ACC | L-Lys-ACC | D-Arg-ACC |

| EDTA | 10 mM | 48 | 100 | 36 |

| 1 mM | 96 | 102 | 74 | |

| 1, 10-Phenanthroline | 10 mM | 5 | 30 | 60 |

| 1 mM | 103 | 88 | 81 | |

| Bestatin | 1 mM | 94 | 102 | 93 |

| 0.1 mM | 97 | 100 | - | |

| Amastatin | 0.1 mM | 92 | 99 | 95 |

| 0.01 mM | 91 | - | - | |

| Apstatin | 0.1 mM | 97 | 102 | 96 |

| 0.01 mM | 92 | - | - | |

| E-64 | 1 mM | 0.1 | 15 | 21 |

| 0.1 mM | 57 | 93 | 97 | |

| TLCK | 0.1 mM | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.01 mM | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Leupeptin | 0.1 mM | 0 | 67 | 0 |

| 0.01 mM | 0 | 76 | 0 | |

| Pepstatin | 1 mM | 90 | 87 | 95 |

| 0.1 mM | 104 | 92 | - | |

| AEBSF | 1 mM | 75 | 71 | 90 |

| 0.1 mM | 88 | 76 | - | |

P. gingivalis strain W83 were grown in anaerobic conditions as described in Figure 1. Bacteria at early stationary phase were adjusted to an OD600 of 1.5 and 20 μl of the whole culture were incubated with the inhibitors in 50 mM Phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 in a 96-well plate. After 15 min at 37°C, L-Arg-ACC, D-Arg-ACC or L-Lys-ACC were added to 0.05 mM and the fluorescence released was recorded using a spectrofluorimeter plate-reader SpectraMax M5 (λexc = 380 nm ; λem = 460 nm). Results are expressed as the percentage of activity compared to the control without inhibitor (N = 3; SD < 15 %).

Origin of the products: Bestatin, Amastatin, Apstatin, Leupeptin, Pepstatin, 1, 10-Phenanthroline, trans-Epoxysucciny-L-leucyl-amido(4-guanidino)butane (E-64) and Tosyl-lysine-chloromethyl ketone (TLCK) are from Sigma (San Louis, MI, USA). Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) is from USB Corporation (Cleveland, OH, USA) and 4-(2-Aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF) is from Calbiochem.

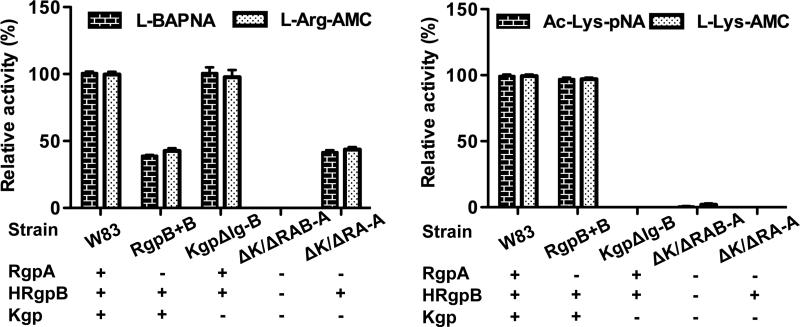

To confirm this hypothesis, P. gingivalis mutants with one, two or all three gingipain genes deleted (Popadiak et al., 2007) were analysed for aminopeptidase activity. The Arg- and Lys-specific aminopeptidase activities in the mutant strains were determined using commercially available fluorogenic substrates, L-arginine-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (L-Arg-AMC) and L-lysine-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (L- Lys-AMC; Sigma, San Louis, USA) and compared to the endopeptidase activity of Rgps and Kgp using the chromogenic substrates benzoyl-L-arginine-para-nitroanilide (Bz-L-Arg-pNA) and acetyl-L-lysine-para-nitroanilide (Ac-L-Lys-pNA), respectively. Compared to the wild-type W83 strain, Kgp-null mutants (Δkgp) showed no activity with either L-Lys-AMC or Ac-L-Lys-pNA (Figure 2B). Similarly, the deletion of both rgpB and rgpA genes (ΔrgpAΔrgpB) suppressed the aminopeptidase activity for the substrate L-Arg-AMC, whereas the mutant lacking only the rgpB gene (ΔrgpB) lost only half of this activity (Figure 2A). These results, similar to those obtained with Bz-L-Arg-pNA, indicated that RgpA and RgpB equally contribute to the Arg-specific aminopeptidase activity in P. gingivalis. Together, these data demonstrate that in addition to their endopeptidase activity, gingipains are responsible for all of the P. gingivalis aminopeptidase activity detected using the three identified fluorogenic substrates.

Figure 2. Effect of gingipain gene-deletion on aminopeptidase activity of P. gingivalis.

A) The arginine-aminopeptidase activity of P. gingivalis strain W83 deletion mutants, including single (ΔrgpA and Δkgp), double (ΔrgpAΔkgp), and triple (ΔrgpAΔrgpBΔkgp) gingipain gene knockouts (Popadiak et al., 2007) was determined using L-Arg-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (L-Arg-AMC). A 20 μl aliquot of bacteria culture at early stationary phase adjusted to an OD600 of 1.5, was incubated 10 min at 37°C in gingipain assay buffer (200 mM Tris, 5 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.02% NaN3, pH 7.6) supplemented with 10 mM L-cysteine. After 10 min at 37°C, fluorogenic substrates were added (50 μM) and the fluorescence release (λexc = 380 nm; λem = 460 nm) was recorded using a spectrofluorimeter plate-reader, SpectraMax M5. As a control, the arginine-endopeptidase activity of each mutant was determined under the same conditions using the chromogenic substrate Nα-benzoyl-L-arginine-pnitroanilide hydrochloride (Bz-L-Arg-pNA ; λ = 405 nm). B) Following the same protocol, lysine-aminopeptidase activity of the P. gingivalis deletion mutants was determined for L-Lys-AMC substrate. As a control, the lysine-endopeptidase activity was measured using the chromogenic substrate N-α-acetyl-L-lysine-p-nitroanilide (Ac-L-Lys-pNA; λ = 405 nm). Results are expressed as relative residual activity compared to the activity of native P. gingivalis W83 (N=3; SD < 15 %).

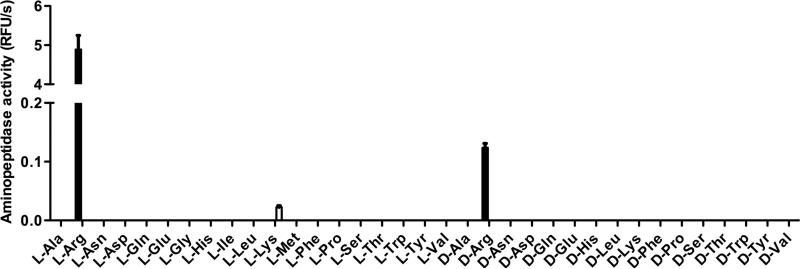

The aminopeptidase specificity of purified gingipains was then determined using the fluorogenic substrates library (Figure 3). Whereas Kgp activity was strictly limited to L-Lys-ACC substrate, RgpB and HRgpA hydrolysed both L- and D-Arg-ACC substrates (data not shown), though the latter was cleaved with rather low velocity. These results corroborate the strict selectivity observed for the S1 pocket of the gingipain catalytic site characterised with endopeptidase substrates (Pike et al., 1994).

Figure 3. Specificity of purified RgpB and Kgp aminopeptidase activity.

Kgp and HRgpA were purified from cell-free medium of P. gingivalis HG66, as previously described (Potempa and Nguyen, 2007; Skottrup et al., 2011). RgpB with a C-terminal His-tag was purified from P. gingivalis W83 strain bearing the modified rgpB gene (Skottrup et al., 2011). Specificities of the amino-peptidase activity of purified RgpB (black bars) and Kgp (empty bars) were investigated using a library of 82 fluorogenic substrates. RgpB and Kgp (100 nM) were incubated in assay buffer (200 mM Tris, 5 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.02% NaN3, pH 7.6) supplemented with 10 mM L-cysteine. After 10 min at 37 °C, fluorogenic substrate was added (50 μM) and the fluorescence release (λexc = 380 nm; λem = 460 nm) was recorded using a spectrofluorimeter plate-reader, SpectraMax M5. For clarity, only results obtained for natural L- and D- amino-acid derived substrates are represented. No activity was observed for the other substrates tested. N=3 +/− SD

The kinetic constants for L-Arg-AMC hydrolysis by RgpB and HRgpA were determined and compared to those obtained for the endopeptidase substrate Carbozybenzoyl-L-arginine-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Z-Arg-AMC; Sigma, San Louis, USA). The comparison revealed that aminopeptidase activities of arginine-specific gingipains were weaker than their endopeptidase activities, with a specificity constant kcat/Km about 100-times lower for L-Arg-AMC than for Z-L-Arg-AMC (Table II). Similarly, affinity for L-Arg-AMC was found to be 30-times lower than for Z-L-Arg-AMC as indicated by Km values, primarily contribute to the decreased enzymatic efficiency of Rgps at the exopeptidase . The catalytic constant kcat is only three times lower for hydrolysis of L-Arg-AMC cleavage sitein comparison to Z-L-Arg-AMC. In accordance with the relative activity observed for P. gingivalis extracts, the capacity of gingipains to hydrolyse D-Arg-AMC (HRgpA/RgpB) and L-Lys-AMC (Kgp) is even weaker, with a kcat/Km less than 1 mM−1s−1 (data not shown). These low enzyme activity values may bring into question the physiological relevance of the aminopeptidase activity of gingipains, in particular, the hydrolysis of D-Arg by RgpB and HRgpA, as well as L-Lys by Kgp. Therefore, it was interesting to compare the L-arginine aminopeptidase activity of gingipains to those of well-characterised eukaryotic aminopeptidases. From this comparison, it is clear that human cathepsin H, aminopeptidase B and aminopeptidase N cleave fluorogenic substrates with kinetic constants similar to those observed for the arginine-specific gingipain catalysed hydrolysis of Z-Arg-AMC (Table II).

Table II.

Comparison of the kinetic constants of arginine-specific gingipains toward amino- and endo-peptidase substrates

| Enzymes | Substrates | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (mM−1s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RgpB | L-Arg-AMC | 2.32 +/− 0.19 | 255 +/− 21 | 9.1 |

| RgpB | Ac-L-Arg-AMC | 7.88 +/− 0.2 | 9,244 +/− 0.6 | 1295 |

| HRgpA | L-Arg-AMC | 0.86 +/− 0.07 | 94 +/− 11 | 9.4 |

| HRgpA | Ac-L-Arg-AMC | 2.65 +/− 0.3 | 2.84 +/− 0.4 | 933 |

| Aminopeptidase N | L-Arg-AMC | 2.36 (a) | 160 (a) | 14.8 (a) |

| Aminopeptidase B | L-Arg-pNA | 2.3 (b) | 300 (b) | 7 7 (b) |

| Cathepsin H | L-Arg-AMC | 2.54 (c) | 150 (c) | 16.9 (c) |

RgpB and HRgpA (1-10 nM) were incubated in assay buffer (200 mM Tris, 5 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.02% NaN3, pH 7.6) supplemented with 10 mM L-cysteine. After 10 min at 37°C, fluorogenic substrates were added at various concentrations (0-500 μM) and the fluorescence released (λexc = 380 nm; λem = 460 nm) was recorded using a spectrofluorimeter plate-reader SpectraMax M5. kcat and Km were obtained by non-linear regression using Graphpad Prism software version 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, USA). N=3 +/− SD

from (Huang et al., 1997)

from (Nagata et al., 1991)

from (Schwartz and Barrett, 1980)

To conclude, despite the large spectrum of specificities represented in the fluorogenic substrates library, no metalloaminopeptidase activity was identified in the P. gingivalis extract. This observation seems to be controversial considering the presence of several ORFs encoding putative metalloaminopeptidases in the P. gingivalis genome (MEROPS The peptidase database, (Rawlings et al., 2008)), and the inhibitory effect of bestatin on P. gingivalis growth. Total inhibition of growth of several P. gingivalis strains, including W83 was exerted at 2.5 μg/ml of bestatin. On the other hand, bestatin had no effect on the growth of other bacterial species (Grenier and Michaud, 1994). Taking into account bestatin specificity as the metalloaminopeptidase inhibitor, it is likely that it targets a peptidase unique for P. gingivalis, which is essential for the growth of this bacterium. Nevertheless, in our assay conditions, no such activity was detected in P. gingivalis. This could be due to low concentration of the unknown enzyme, its unique specificity and/or special requirements (pH, bivalent cation, pI, etc.) at which the enzyme is active. Instead, using a collection of class-specific protease inhibitors and gingipain-null mutant strains, we demonstrated that gingipains are solely responsible for the aminopeptidase activities detected in P. gingivalis. Whereas Kgp aminopeptidase activity is weak, the kinetic constants obtained for RgpB and HRgpA are comparable to those of human aminopeptidases. Cumulatively, this finding may contribute to a better understanding of the role of gingipains in the pathological mechanism of the onset, development, and progression of periodontitis, and may help to elucidate the association of periodontitis with systemic diseases.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by grants from: the National Institutes of Health (Grant DE 09761, USA), National Science Center (2011/01/B/NZ6/00268, Kraków, Poland), the European Community (FP7-HEALTH-2010-261460 “Gums&Joints”), and the Foundation for Polish Science (TEAM project DPS/424-329/10) (to J.P.). The Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology of the Jagiellonian University is a beneficiary of structural funds from the European Union (POIG.02.01.00-12-064/08). The Drag laboratory is supported by the Foundation for Polish Science and the State for Scientific Research Grant N N401 042838 in Poland. Marcin Poręba is supported by the European Union Human Capital National Cohesion Strategy.

References

- de Pablo P, Chapple IL, Buckley CD, Dietrich T. Periodontitis in systemic rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2009;5:218–224. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drag M, Bogyo M, Ellman JA, Salvesen GS. Aminopeptidase fingerprints, an integrated approach for identification of good substrates and optimal inhibitors. J. Biol Chem. 2010;285:3310–3318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.060418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier D, Michaud J. Selective growth inhibition of Porphyromonas gingivalis by bestatin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1994;123:193–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Nguyen KA, Potempa J. Dichotomy of gingipains action as virulence factors: from cleaving substrates with the precision of a surgeon's knife to a meat chopper-like brutal degradation of proteins. Periodontol. 2000. 2010;54:15–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K, Takahara S, Kinouchi T, Takeyama M, Ishida T, Ueyama H, Nishi K, Ohkubo I. Alanyl aminopeptidase from human seminal plasma: purification, characterization, and immunohistochemical localization in the male genital tract. J. Biochem. 1997;122:779–787. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey LL, Fu R, Buckley DI, Freeman M, Helfand M. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008;23:2079–2086. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0787-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamer AR, Craig RG, Dasanayake AP, Brys M, Glodzik-Sobanska L, de Leon MJ. Inflammation and Alzheimer's disease: possible role of periodontal diseases. Alzheimers. Dement. 2008a;4:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamer AR, Dasanayake AP, Craig RG, Glodzik-Sobanska L, Bry M, de Leon MJ. Alzheimer's disease and peripheral infections: the possible contribution from periodontal infections, model and hypothesis. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2008b;13:437–449. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-13408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont RJ, Jenkinson HF. Life below the gum line: pathogenic mechanisms of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998;62:1244–1263. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1244-1263.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata Y, Mizutani S, Nomura S, Kurauchi O, Kasugai M, Tomoda Y. Purification and properties of human placental aminopeptidase B. Enzyme. 1991;45:165–173. doi: 10.1159/000468885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paster BJ, Dewhirst FE. Molecular microbial diagnosis. Periodontol. 2000. 2009;51:38–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike R, McGraw W, Potempa J, Travis J. Lysine-and arginine-specific proteinases from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Isolation, characterization, and evidence for the existence of complexes with hemagglutinins. J Biol. Chem. 1994;269:406–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popadiak K, Potempa J, Riesbeck K, Blom AM. Biphasic effect of gingipains from Porphyromonas gingivalis on the human complement system. J. Immunol. 2007;178:7242–7250. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potempa J, Nguyen KA. Purification and characterization of gingipains. Curr. Protoc. Protein. Sci. 2007 doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps2120s49. Chapter 21, Unit 21 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potempa J, Pike R, Travis J. Titration and mapping of the active site of cysteine proteinases from Porphyromonas gingivalis (gingipains) using peptidyl chloromethanes. Biol. Chem. 1997;378:223–230. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1997.378.3-4.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings ND, Morton FR, Kok CY, Kong J, Barrett AJ. MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2008;36:D320–325. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz WN, Barrett AJ. Human cathepsin H. Biochem. J. 1980;191:487–497. doi: 10.1042/bj1910487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skottrup PD, Leonard P, Kaczmarek JZ, Veillard F, Enghild JJ, O'Kennedy R, Sroka A, Clausen RP, Potempa J, Riise E. Diagnostic evaluation of a nanobody with picomolar affinity toward the protease RgpB from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Anal. Biochem. 2011;415:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL., Jr. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1998;25:134–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervoudi E, Papakyriakou A, Georgiadou D, Evnouchidou I, Gajda A, Poreba M, Salvesen GS, Drag M, Hattori A, Swevers L, Vourloumis D, Stratikos E. Probing the S1 specificity pocket of the aminopeptidases that generate antigenic peptides. Biochem. J. 2011;435:411–420. doi: 10.1042/BJ20102049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]