Abstract

Objective

Condom use is critical for the health of sexually active adolescents, and yet many adolescents fail to use condoms consistently. One interpersonal factor that may be key to condom use is sexual communication between sexual partners; however, the association between communication and condom use has varied considerably in prior studies of youth. The purpose of this meta-analysis was to synthesize the growing body of research linking adolescents’ sexual communication to condom use, and to examine several moderators of this association.

Methods

A total of 41 independent effect sizes from 34 studies with 15,046 adolescent participants (Mage=16.8, age range=12–23) were meta-analyzed.

Results

Results revealed a weighted mean effect size of the sexual communication-condom use relationship of r = .24, which was statistically heterogeneous (Q=618.86, p<.001, I2 =93.54). Effect sizes did not differ significantly by gender, age, recruitment setting, country of study, or condom measurement timeframe; however, communication topic and communication format were statistically significant moderators (p<.001). Larger effect sizes were found for communication about condom use (r = .34) than communication about sexual history (r = .15) or general safer sex topics (r = .14). Effect sizes were also larger for communication behavior formats (r = .27) and self-efficacy formats (r = .28), than for fear/concern (r = .18), future intention (r = .15), or communication comfort (r = −.15) formats.

Conclusions

Results highlight the urgency of emphasizing communication skills, particularly about condom use, in HIV/STI prevention work for youth. Implications for the future study of sexual communication are discussed.

Keywords: adolescent sexual health, sexual communication, sexual negotiation, assertiveness, condom use, safer sex

Consistent condom use among sexually active adolescents and young adults is of paramount importance for sexual health. Condoms are the most effective method to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV for sexually active youth, and condoms can also prevent unwanted pregnancy (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010; Holmes, Levine, & Weaver, 2004). While new prevention options and strategies for curbing HIV have advanced, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (Baeten et al., 2012) and treatment as prevention (Cohen et al., 2011), condoms remain a critical, cost-effective, and accessible HIV/AIDS prevention tool, particularly for adolescents who engage in multiple short-term sexual relationships. Despite the risk of STIs, HIV, and unwanted pregnancy, nearly half of sexually active youth in the U.S. do not use condoms consistently (CDC, 2010). Such risk behavior results in serious health consequences: There are currently over 9 million STIs and 8,300 new cases of HIV among adolescents and young adults each year (CDC, 2013).

Identifying those factors that are proximally associated with condom use and potentially modifiable has been a top priority for research and prevention efforts seeking to improve adolescent health (House, Bates, Markham, & Lesesne, 2010). Increasingly, one factor that has been associated with safer sexual behavior is sexual communication, defined as the ability to discuss and negotiate safer sex with a partner (Noar, 2007). The link between communication and condom use is understandable given the interpersonal nature of sexual activity and the need for sexual partners – particularly girls – to negotiate safer sexual practices if they are to occur (Amaro, 1995). Yet, open communication about sexual health topics often does not take place during sexual encounters (DiClemente, 1991; Ryan, Franzetta, Manlove, & Holcombe, 2007).

Conversations about sexual health are sensitive and potentially embarrassing for adolescents who are still learning to develop and maintain intimate relationships and are often negotiating intimate experiences for the first time (Collins, Welsh, & Furman, 2009; Diamond & Savin-Williams, 2009). Discussing sexual health topics also may violate cultural norms for indirectness around sexual behavior, especially for adolescent girls who are not socialized to assert their sexual desires or preferences in relationships (Lear, 1995; Metts & Spitzberg, 1996; Tolman, 2005). Further, compared to adults, adolescents are in a developmental period during which immaturity in the prefrontal cortex contributes to heightened impulsivity and a lower likelihood to plan ahead and consider the future consequences of risky behavior (Steinberg, 2007, 2008). For these reasons, it is perhaps no surprise that many adolescents – more than half in some studies (DiClemente, 1991; Ryan et al., 2007; Welch Cline, Johnson, & Freeman, 1992) – report that they have not discussed condoms or other safer sex topics with their sexual partners.

Sexual communication has been increasingly recognized in health behavior theories that explain condom use behavior (for review, see Noar, 2007). Historically, condom use has pushed the limits of behavioral theories because, unlike most health behaviors that are enacted by individuals, condom use requires the cooperation of two people. In some cases, new theories have been developed that include a dyadic communication component, such as the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model (Fisher & Fisher, 1992), which posits that both perceived and actual sexual communication skills are key behavioral skills required for condom use. Other theories, such as the Reasoned Action Model (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2009) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT; Bandura, 1999), have been expanded to incorporate the role of sexual communication as an intervening variable that can account for the roles of other, more distal predictors of condom use, such as condom attitudes and intentions (Bryan, Fisher, & Fisher, 2002; Widman, Golin, & Noar, 2013; Zimmerman, Noar, Feist-Price, Dekthar, Cupp, Anderman, & Lock, 2007).

Among adults, the empirical literature largely supports the theoretical proposition that partner sexual communication is associated with condom use (Allen, Emmers-Sommer, & Crowell, 2002; Noar, Carlyle, & Cole, 2006; Sheeran, Abraham, & Orbell, 1999). A meta-analysis of over 40 psychosocial predictors of condom use found that sexual communication between partners was the most robust indicator of condom use (Sheeran et al., 1999). A second, more recent meta-analysis confirmed the significant overall association between communication and condom use and found several factors moderated this relationship, including communication topic and format (Noar, Carlyle, & Cole, 2006). Specifically, the strongest relationship between communication and condom use was found in studies that specifically assessed communication about condoms as well as those that assessed communication behaviors, rather than communication self-efficacy or intentions to communicate.

While the results in largely adult populations are promising, prior reviews have included only a small subset of studies of adolescents and these studies were not analyzed separately; thus, it is not clear if sexual communication is equally as likely – or perhaps more or less likely – to influence condom use among youth. It is known, however, that adolescents’ patterns of both communication and sexual risk behaviors differ from those patterns shown in adults. For example, adolescents are less likely to be sexually active than adults, but their sexual practices are often riskier. Condom use is typically sporadic, and the transient nature of adolescent relationships can result in multiple sexual partnerships over short periods of time (CDC, 2010). Additionally, youth often lack the appropriate skills and prior experience needed to successfully negotiate safer sexual behavior (Metts & Spitzberg, 1996), and as noted previously, they may also lack the appropriate brain maturity to make deliberate, rational choices that will impact their long term sexual health (Steinberg, 2007, 2008). This brain immaturity may result in less thoughtful planning around sexual activity and less communication with partners, as compared to adults.

When it comes to the link between adolescent sexual communication and condom use, there is some inconsistency in the literature. Whereas many studies of youth find strong positive associations between communication and condom use (Brown et al., 2008; Grossman, Hadley, Brown, Houck, Peters, & Tolou-Shams, 2008; Harrison et al., 2012), others report no significant relationships (Maxwell, Bastani, & Yan, 1995; Roye, 1998), or even negative relationships (Deardorff, Tschann, Flores, & Ozer, 2010; Hart & Heimberg, 2005). For example, in an ethnically diverse sample of over 1,200 youth, Brown et al. (2008) found that sexual communication was associated with a greater likelihood of condom use at last sex; whereas in a sample of 839 Latino youth, Deardorff et al. (2010) found that comfort with sexual communication was associated with significantly less consistent condom use in the past month. Despite this inconsistency, the sexual communication field is burgeoning and scores of sexual health intervention programs for youth have been targeting communication skill building as key program components (DiClemente et al., 2009; Tortolero, Markham, Peskin, Shegog, Addy, Escobar-Chaves, & Baumler, 2010). The lack of a systematic meta-analysis of adolescent communication is a key gap in the literature; such a synthesis could provide much needed guidance to future intervention efforts as well as health behavior theories that are specific to adolescent condom use.

Thus, the primary purpose of the current study was to conduct a meta-analysis that synthesizes the current evidence to determine the degree to which sexual communication between adolescent partners is associated with condom use. Given the heterogeneity in effects of communication observed in the literature, a second goal was to examine the possible influence of several potential moderators. These included gender, age, recruitment setting, study location, topic of communication (i.e., communication about condoms specifically, partner sexual history, or safer sex more generally), and format for communication measurement (i.e., behavior, self-efficacy, intentions, fear, or comfort). Finally, due to the variability in the way in which condom use has been assessed in past studies (for a discussion of this issue, see Noar, Cole, & Carlyle, 2006), we also examined the timeframe of condom use as an additional moderator.

Method

Search Strategy

A detailed search for published studies was undertaken to locate studies applicable to this meta-analysis. Comprehensive searches of Medline, PsycINFO, and Communication & Mass Media Complete databases were conducted through April 2013 using the following combination of key words, with asterisks used as “wild cards” to find multiple variations of each word: (adolescen* OR teen* OR youth OR middle school OR high school) AND (communicat* OR discuss* OR negotiat* OR assert* OR talk OR influence OR compliance gain) AND (condom* OR contracept* OR unprotected sex OR safe* sex OR sex* risk). Additional studies of potential relevance were located by examining review articles and meta-analyses related to sexual communication (Allen et al., 2002; Bastien, Kajula, & Muhwezi, 2011; Casey, Timmermann, Allen, Krahn, & Turkiewicz, 2009; Commendador, 2010; DiIorio, Pluhar, & Belcher, 2003; East, Jackson, O’Brien, & Peters, 2007; Guilamo-Ramos, Bouris, Lee, McCarthy, Michael, Pitt-Barnes, & Dittus, 2012; Jaccard, Dodge, & Dittus, 2002; Kotchick, Shaffer, & Forehand, 2001; Miller, Benson, & Galbraith, 2001; Noar, Carlyle, & Cole, 2006; Sheeran et al., 1999). This search produced an initial 4,611 scientific articles.

Selection Criteria

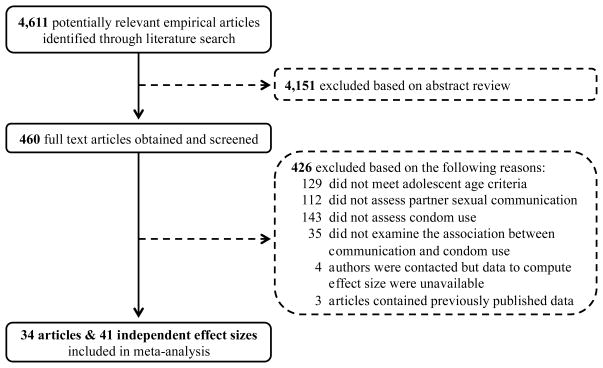

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: 1) sampled adolescents, defined as a mean sample age of 18 or younger and no participants over 24 years of age; 2) measured partner sexual communication (studies of only parent or friend communication were excluded); 3) measured condom use or unprotected sex (studies that measured condom intentions or other sexual health outcomes such as use of contraception were excluded); and 4) were published in English. These selection criteria resulted in a final sample of 34 articles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram

In most cases, studies assessed sexual communication using a single measure. However, in five studies (Crosby, DiClemente, Wingood, Salazar, Harrington, Davies, & Oh, 2003; Donald, Lucke, Dunne, O’Toole, & Raphael, 1994; Overby & Kegeles, 1994; Tschann, Flores, de Groat, Deardorff, & Wibbelsman, 2010; Wilson, Kastrinakis, D’Angelo, & Getson, 1994), more than one sexual communication measure was assessed and reported. Given that each study could only contribute one effect size to the meta-analysis, a random number generator was used to select one communication measure from each study to include in analyses. Similarly, four studies provided data for both the frequency of condom use and condom use at last sex (Brown et al., 2008; Crosby et al., 2002; Crosby, DiClemente, Wingood, Salazar, Head, Rose, & McDermott-Sales, 2008; Overby & Kegeles, 1994). In these cases, the frequency variable was used to calculate effect sizes, as this outcome is likely to be more representative of the overall pattern of condom use (Noar, Cole, & Carlyle, 2006). Finally, seven articles reported analyses separately for boys and girls (Bryan et al., 2002; Deardorff et al., 2010; Donald et al., 1994; Gallupe, Boyce, & Fergus, 2009; Gutiérrez, Oh, & Gillmore, 2000; Harrison et al., 2012; Troth & Peterson, 2000). Effect sizes were calculated separately by gender in these cases, resulting in a total of 41 independent effect sizes for analyses from 15,046 participants.

Data Extraction

Two of the authors independently coded the primary studies. The following data were abstracted: (a) demographic and sample characteristics, (b) sexual communication measurement characteristics (i.e., topic, format), and (c) condom use measurement (i.e., timeframe of assessment). Communication topic was coded into one of three categories, using the definitions provided by Noar, Carlyle, and Cole (2006): 1) condom use (i.e., communication specifically about condom use); 2) sexual history (i.e., communication about sexual history, including the items related to past sexual experience, number of sexual partners, STIs, and HIV); and 3) safer sex topics (i.e., communication about general safer sex issues, which could include a variety of items related to condom use, sexual history, STIs, HIV, sex, and safer sex). Additionally, communication format was coded into one of five categories, also using definitions similar to those provided by Noar, Carlyle, and Cole (2006): 1) past behavior (i.e., extent to which one had communicated or insisted on safer sex with a sexual partner); 2) self-efficacy (i.e., perceived ability to communicate about or insist on safer sex with a sexual partner); 3) intention (i.e., extent to which one planned on communicating about or insisting on safer sex with a sexual partner); 4) fear/concern (i.e., perceived fear, concern, or stress over communicating with a partner); and 5) communication comfort (i.e., perceived comfort communicating with a partner). The mean percentage agreement across all coding categories was 94%. Discrepancies between coders were resolved through discussion with the research team (i.e., all authors).

Calculation of Effect Sizes

The Pearson correlation coefficient, r, was used as the indicator of effect size (range = −1.0 to +1.0; Rosenthal, 1991). According to Cohen (1992), effect sizes based on correlations can be interpreted as small (.10), medium (.25), or large (.40). When rs were reported in an article, they were directly extracted. If rs were not reported, other statistics that could be converted to rs (e.g., t test, summary statistics) were converted using appropriate formulas (Rosenthal, 1991). When none of the statistics in the study could be converted to an r, the authors were contacted and appropriate data were requested. To keep effect sizes consistent and interpretable, higher values always indicate a positive relation between communication and condom use.

Once study characteristics were coded and effect sizes were extracted, a Fisher r to z transformation was performed (Rosenthal, 1991). These values then were weighted by their inverse variance and combined. We used random effects meta-analytic procedures for the primary analyses (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Once analyses were complete, the effect sizes and confidence intervals were transformed back to r’s for presentation. The Q statistic and I2 were used to examine whether significant heterogeneity existed among the effect sizes. Effect sizes for hypothesized moderators were calculated along with their 95% confidence intervals, and those effect sizes were statistically compared using the Qb statistic. For these analyses, mixed effects models were utilized to allow for the possibility of differing variances across subgroups (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). In addition, in the case of continuous (i.e., interval level) moderator variables, correlations were calculated between particular moderator variables and the effect size. All analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, Version 2.2.046, and SPSS Version 19.

Results

Study Characteristics

Table 1 provides a summary of the 34 studies included in the meta-analysis, including sample characteristics, potential moderator variables, and effect sizes. Participants (cumulative N = 15,046) ranged in age from 12–23, with a mean age of 16.77 (SD = 1.41) years across studies. Samples were drawn from schools (k = 15), health clinics (k = 12), jails/detention centers (k = 4), community settings (k = 3), or other/mixed sites (k = 7). Many studies used combined samples of boys and girls (k =16); however, other studies analyzed data from boys (k = 10) and girls (k = 15) independently. The majority of studies were conducted in the United States (k = 30); 11 studies used non-U.S. samples.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics and Effect Sizes Included in Meta-Analysis

| Study | Sample Characteristics | Communication | Condom Use | Effect Size | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % girls | Age M | Age Range | Population | Location | Topic | Format | Timeframe | r | |

| Abraham et al. (1992) mix | 351 | 55 | 17.1 | 16–18 | Community | Scotland | History | Intent | Not Specified | 0.010 |

| Baele et al. (2001) mix | 163 | 61 | 17.0 | nr | School | Belgium | Condoms | Self-Eff | Not Specified | 0.400 |

| Barthlow et al. (1995) mix | 328 | 16 | nr | 12–19 | Incarcerated | U.S. | History | Behavior | Not Specified | 0.162 |

| Basen-Engquist et al. (1999) mix | 1718 | nr | nr | 14–18 | School | U.S. | Condoms | Self-Eff | 3 month | 0.225 |

| Brown et al. (2008) mix | 1218 | 57 | nr | 15–21 | Other/Mix | U.S. | Condoms | Behavior | 3 month | 0.334 |

| Bryan et al. (2002) boys | 170 | 0 | 15.0 | 13–19 | School | U.S. | Condoms | Behavior | 1 month | 0.710 |

| Bryan et al. (2002) girls | 123 | 100 | 15.0 | 13–19 | School | U.S. | Condoms | Behavior | 1 month | 0.780 |

| Crosby et al. (2002) girls | 522 | 100 | 16.0 | 14–18 | Other/Mix | U.S. | Safe Sex | Behavior | Other | 0.102 |

| Crosby et al. (2003) girls | 144 | 100 | 17.8 | 14–20 | Clinic | U.S. | Safe Sex | Behavior | 1 month | 0.218 |

| Crosby et al. (2008) girls | 566 | 100 | 17.8 | 15–21 | Clinic | U.S. | Condoms | Low Fear | 2 month | 0.175 |

| Deardorff et al. (2010) boys | 377 | 0 | 18.8 | 16–22 | Clinic | U.S. | Safe Sex | Comfort | 1 month | −0.150 |

| Deardorff et al. (2010) girls | 462 | 100 | 18.3 | 16–22 | Clinic | U.S. | Safe Sex | Comfort | 1 month | −0.140 |

| Depadilla et al. (2011) mix | 701 | 100 | 17.6 | 14–20 | Clinic | U.S. | Safe Sex | Mix | Other | 0.535 |

| DiClemente (1991) mix | 79 | 23 | nr | 14–21 | Incarcerated | U.S. | Safe Sex | Behavior | Not Specified | 0.418 |

| DiClemente et al. (1996) mix | 116 | 51 | nr | 12–21 | Community | U.S. | Condoms | Self-Eff | 6 month | 0.311 |

| DiIorio et al. (2001) mix | 116 | 44 | 13.9 | 13–15 | Community | U.S. | History | Self-Eff | Not Specified | 0.177 |

| Donald et al. (1994) boys | 395 | 0 | 16.8 | 13–20 | School | Australia | Safe Sex | Behavior | Last Sex | 0.054 |

| Donald et al. (1994) girls | 505 | 100 | 16.8 | 14–20 | School | Australia | Safe Sex | Behavior | Last Sex | 0.098 |

| Gallupe et al. (2009) boys | 863 | 0 | 15.8 | 13–21 | School | Canada | Condoms | Intent | Last Sex | 0.112 |

| Gallupe et al. (2009) girls | 1143 | 100 | 15.8 | 13–21 | School | Canada | Condoms | Intent | Last Sex | 0.298 |

| Grossman et al. (2008) mix | 446 | 62 | 18.2 | 15–21 | Other/Mix | U.S. | Condoms | Behavior | 3 month | 0.498 |

| Gutiérrez et al. (2000) boys | 148 | 0 | 16.0 | 14–19 | Other/Mix | U.S. | Condoms | Self-Eff | 3 month | 0.140 |

| Gutiérrez et al. (2000) girls | 185 | 100 | 16.0 | 14–19 | Other/Mix | U.S. | Condoms | Self-Eff | 3 month | 0.290 |

| Guzmán et al. (2003) mix | 34 | 52 | 13.3 | 11–17 | School | U.S. | Safe Sex | Comfort | Not Specified | −0.334 |

| Harrison et al. (2012) boys | 91 | 0 | 15.4 | 14–17 | School | South Africa | Condoms | Self-Eff | Last Sex | 0.491 |

| Harrison et al. (2012) girls | 64 | 100 | 15.4 | 14–17 | School | South Africa | Condoms | Self-Eff | Last Sex | 0.377 |

| Hart & Heimberg (2005) boys | 100 | 0 | 18.8 | 16–21 | Other/Mix | U.S. | Condoms | Behavior | 6 month | −0.070 |

| Magura et al. (1994) boys | 421 | 0 | 17.8 | 16–19 | Incarcerated | U.S. | Condoms | Behavior | Not Specified | 0.400 |

| Maxwell et al. (1995) mix | 100 | 56 | 18.5 | 14–19 | Clinic | U.S. | Safe Sex | Behavior | Past Year | 0.000 |

| Overby & Kegeles (1994) girls | 60 | 100 | 16.9 | 13–19 | Clinic | U.S. | Condoms | Behavior | Not Specified | 0.414 |

| Rickman et al. (1994) mix | 1439 | 15 | nr | 12–17 | Incarcerated | U.S. | History | Behavior | Not Specified | 0.226 |

| Roye (1998) girls | 452 | 100 | 18.0 | 12–21 | Clinic | U.S. | Safe Sex | Self-Eff | 1 month | 0.000 |

| Shoop & Davidson (1994) mix | 45 | 50 | nr | 15–18 | Other/Mix | U.S. | Safe Sex | Self-Eff | Past Year | 0.514 |

| Shrier et al. (1999) girls | 22 | 100 | 17.2 | 14–22 | Clinic | U.S. | Condoms | Self-Eff | Last Sex | 0.492 |

| Small et al. (2010) girls | 189 | 100 | 18.0 | 13–23 | Clinic | U.S. | Safe Sex | Behavior | Last Sex | 0.329 |

| Troth & Peterson (2000) boys | 26 | 0 | 17.5 | 16–19 | School | Australia | Safe Sex | Low Fear | Not Specified | 0.280 |

| Troth & Peterson (2000) girls | 50 | 100 | 17.5 | 16–19 | School | Australia | Safe Sex | Low Fear | Not Specified | 0.230 |

| Tschann et al. (2010) mix | 393 | 61 | 18.5 | 16–22 | Clinic | U.S. | Condoms | Behavior | 1 month | 0.068 |

| van Empelen et al. (2006) mix | 108 | 34 | 15.0 | 14–16 | School | Netherlands | Condoms | Behavior | Past Year | 0.070 |

| Whitaker et al. (1999) mix | 372 | nr | nr | 14–17 | School | U.S. | Safe Sex | Behavior | Last Sex | 0.077 |

| Wilson et al. (1994) boys | 241 | 0 | 16.2 | 13–19 | Clinic | U.S. | Safe Sex | Behavior | Not Specified | 0.012 |

Note. N = sample size used in analysis; nr = not reported; Effect Size r = correlation coded from study; Self-Eff = self-efficacy; mix = mixed gender sample; boys = all male sample or subsample; girls = all female sample or subsample.

Magnitude and Direction of Effects

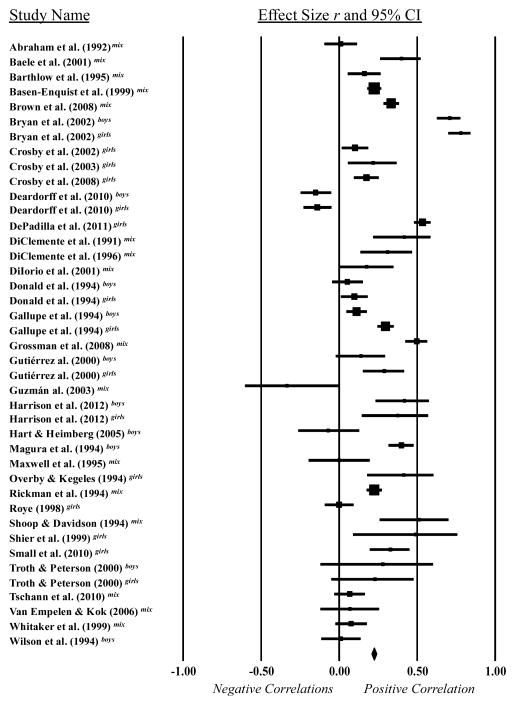

While individual study effect sizes ranged from −.35 to .78, the overall weighted mean effect size for the sexual communication-condom use relationship was r = .24 (95% CI = 0.17–0.30). This overall effect size indicates that sexual communication has a statistically significant association with condom use behavior among youth (see Figure 1). In order to examine the possibility of publication bias, a fail-safe N value was calculated and the trim and fill procedure was applied (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Orwin’s method (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001) to calculate fail-safe N indicated that 423 studies with non-significant findings would need to exist to reduce the r = .24 effect to a trivial effect size of r = .02. Also, funnel plots of the effect sizes were symmetrical, and the trim and fill analysis suggested no adjustment to the mean effect size (Duval & Tweedie, 2000). In sum, there appeared to be no evidence of publication bias in this literature.

Heterogeneity and Effect Size Moderators

Next, we examined heterogeneity of effect sizes. Statistical testing indicated significant heterogeneity among the studies with regard to the condom use outcome (Q = 618.86, p < .001, I2 = 93.54). Thus, we examined the potential impact of several moderating variables on sexual communication and condom use.

Demographic moderators were examined first (Table 2). Across studies, correlations between condom use effect size and gender (% girls) [r (24) = 0.19, p = 0.38] and age [r (34) = −0.07, p = 0.71] failed to reach significance. The trends, however, suggested larger effects for girls and for those of younger age. Effect sizes for sexual communication were somewhat larger in studies of girls (r = .29) than for studies of boys (r = .21). Effect sizes also were somewhat larger for studies of younger teens (r = .25) than for studies of older teens (r = .20); however, none of these differences were statistically significant. Further, as shown in Table 2, no significant differences were found by recruitment setting (e.g., school, clinic, incarcerated) or study location (i.e., U.S. samples, non-U.S. samples).

Table 2.

Weighted Mean Effect Sizes By Categorical Moderator Variables

| Between groups

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | k | r | 95% CI | p | QB | p |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 5,188 | 15 | .29 | [0.16, 0.41] | .000 | ||

| Male | 2,832 | 10 | .21 | [0.03, 0.37] | .019 | ||

| Total | 8,020 | 25 | -- | -- | -- | 0.61 | ns |

| Age | |||||||

| Sample mean age < 17 | 6,579 | 18 | .25 | [0.16, 0.34] | .000 | ||

| Sample mean age ≥ 17 | 4,963 | 17 | .20 | [0.06, 0.32] | .004 | ||

| Total | 11,542 | 35 | -- | -- | -- | 0.44 | ns |

| Recruitment Setting | |||||||

| School | 5,825 | 15 | .29 | [0.18, 0.39] | .000 | ||

| Clinic | 3,707 | 12 | .16 | [0.00, 0.31] | .051 | ||

| Incarcerated | 2,267 | 4 | .29 | [0.17, 0.40] | .000 | ||

| Community | 583 | 3 | .16 | [−0.03, 0.34] | .106 | ||

| Mixed/Other | 2,664 | 7 | .27 | [0.12, 0.40] | .000 | ||

| Total | 15,046 | 41 | -- | -- | -- | 3.32 | ns |

| Study Location | |||||||

| U.S. | 11,287 | 30 | .25 | [0.17, 0.33] | .000 | ||

| Outside U.S. | 3,759 | 11 | .20 | [0.11, 0.29] | .000 | ||

| Total | 15,046 | 41 | -- | -- | -- | 0.64 | ns |

| Communication Topic | |||||||

| Condom Use | 8,118 | 20 | .34 | [0.25, 0.41] | .000 | ||

| Sexual History | 2,234 | 4 | .15 | [0.04, 0.25] | .008 | ||

| Safer Sex | 4,694 | 17 | .14 | [0.01, 0.26] | .030 | ||

| Total | 15,046 | 41 | -- | -- | -- | 11.21 | .004 |

| Communication Format | |||||||

| Past Behavior | 7,353 | 20 | .27 | [0.17, 0.35] | .000 | ||

| Self-Efficacy | 3,120 | 11 | .28 | [0.19, 0.36] | .000 | ||

| Intention | 2,357 | 3 | .15 | [−0.02, 0.31] | .091 | ||

| Fear/Concern | 642 | 3 | .18 | [0.11, 0.26] | .000 | ||

| Comfort | 873 | 3 | −.15 | [−0.22, −0.09] | .000 | ||

| Total | 14,345 | 40 | -- | -- | -- | 85.84 | .000 |

| Condom Use Timeframe | |||||||

| No Time Specified | 3,308 | 12 | .21 | [0.12, 0.31] | .000 | ||

| Past Year | 253 | 3 | .19 | [−0.10, 0.45] | .203 | ||

| Past 6 Months | 216 | 2 | .13 | [−0.25, 0.47] | .515 | ||

| Past 3 Months | 3,715 | 5 | .31 | [0.20, 0.41] | .000 | ||

| Past 1 Month | 2,121 | 7 | .26 | [−0.02, 0.51] | .070 | ||

| Last Sex | 3,644 | 9 | .22 | [0.12, 0.30] | .000 | ||

| Total | 13,257 | 38 | -- | -- | -- | 2.58 | ns |

Note. N = sample size; k = number of studies; r = weighted mean effect size; CI = confidence interval; ns = not significant. Mixed effects models are presented for moderator analyses.

Next, we examined communication topic and format as potential moderators (Table 2). The relationship between sexual communication and condom use significantly differed by the communication topic discussed [QB (2) = 11.21, p = 0.004], with larger effect sizes for communication about condom use (r = .34) than communication about sexual history (r = .15) or general safer sex (r = .14). Similarly, the relationship between sexual communication and condom use significantly differed by the communication format that was used [QB (4) = 85.84, p < 0.001], with the largest effects found for behavioral (r = .27) and self-efficacy formats (r = .28), compared to fear/concern (r = .18), future intention (r = .15), and communication comfort formats (r = −.15). Of note, greater comfort with communicating about sexual topics was associated with less condom use among sexually active youth.

Finally, we examined the timeframe of condom use measurement as a potential moderator (Table 2). We found the relationships between sexual communication and condom use did not significantly differ depending on the timeframe that was used to assess condom use [QB (5) = 2.58, p = 0.77]; however, trends suggest a somewhat larger effect size when condom use was assessed in the past 3 months (r = .31) than when it was assessed in the past year (r = .19), 6 months (r = .13), 1 month (r = .26), last sex (r = .22), or with no specified timeframe (r = .21).

Discussion

In the U.S., youth under the age of 24 represent 25% of the sexually experienced population, yet they acquire a full 50% of STIs (CDC, 2013). The ability to communicate and negotiate with a sexual partner about sexual health has received attention as one critical protective factor that may be associated with more consistent condom use (Noar, Carlyle, & Cole, 2006); however, until now, the body of evidence on sexual communication among adolescents had yet to be synthesized. Results support the conclusion that communication is important for youth: pooling data from just over 15,000 adolescents and 41 effect sizes, results demonstrated a medium-size association between communication and condom use, with youth who engaged in more sexual communication with their dating partners reporting more condom use in their sexual encounters. This effect is consistent with prior reviews in primarily adult populations (Allen et al., 2002; Noar, Carlyle, & Cole, 2006; Sheeran et al., 1999), and suggests that communicating with a sexual partner is a critical determinant of safer sexual behavior across the lifespan. Importantly, the significant link between communication and condom use was evident for boys and girls, younger and older adolescents, within U.S. and international samples, and across a variety of timeframes for assessing condom use, providing strong evidence for the robustness of this effect.

While the communication-condom use link was generally consistent across groups, there were two moderators of this association that warrant significant attention and further consideration in future research in this area. First, across studies, the relationship between sexual communication and condom use was moderated by the communication topic that was discussed, with the greatest effect found for communication that specifically focused on condom use, and weaker effects noted for communication about sexual history or other more general sexual topics. While general sexual communication may still be important for other aspects of relationship development, such as enhancing sexual or relationship satisfaction (Byers & Demmons, 1999; MacNeil & Byers, 2005; Widman, Welsh, McNulty, & Little, 2006), the current results suggest that a specific focus on condom negotiation and assertiveness may prove most beneficial for consistent condom use over time. Thus, while interventionists may spend some time helping youth develop skills for communicating about sexual health more generally, these results suggest that youth would be best served by training that is specific to talking about condoms. This might include discussion of how to bring up the topic of condoms, when to introduce the topic, and what condom negotiation strategies may be most successful (Noar, Morokoff, & Harlow, 2002), including strategies used in response to pressure not to use condoms (Oncale & King, 2001).

Second, we found the association between sexual communication and condom use significantly differed depending on the way communication was operationalized and measured (i.e., communication format). The strongest effects were noted when communication was assessed with a behavioral format (i.e., asking about actual communication practices) or a self-efficacy format (i.e., asking how confident individuals felt about communication), compared to when the assessment captured communication intentions, fear/concern, or the degree of comfort with communication. The importance of both self-efficacy and the behavioral enactment of communication – as opposed to communication intentions or comfort – fits nicely with recent advances in health behavior theory that emphasize the importance of preparatory behaviors for safer sex (Bryan et al., 2002; de Vet, Gebhardt, Sinnige, Van Puffelen, Van Lettow, & de Wit, 2011; Zimmerman et al., 2007). These preparatory behaviors may include purchasing and carrying condoms, as well as openly and confidently talking with a partner about one’s desires to practice safer sex. The current results support these new theoretical frameworks and suggest additional attention to both self-efficacy and communication behaviors in theories of adolescent sexual decision-making are warranted.

It is worth noting that perceived comfort with sexual communication was significantly negatively associated with condom use, such that adolescents who were more comfortable communicators reported less condom use than youth who were not as comfortable communicating about sex with their partners (Deardorff et al., 2010; Guzman et al., 2003). The reason for this seemingly counterintuitive and perhaps concerning finding is not immediately clear, though it is possible that this effect can be partially explained by the duration and/or quality of the relationship. Specifically, it is possible that adolescents may feel more comfortable about communicating in more committed or established relationships (Herold & Way, 1988), and perhaps the negative relationship between communication comfort and condom use reflects the fact that condoms are used less frequently in established relationships than in new relationships (Katz, Fortenberry, Zimet, Blythe, & Orr, 2000; Ku, Sonenstein, & Pleck, 1994). These results highlight the importance of focusing on the broader relationship context when examining interpersonal aspects of sexual decision-making. Researchers should carefully consider the specific content and operationalization of communication when constructing measures of sexual communication, as these factors may substantially impact the outcome of investigation.

Implications for Intervention Efforts

Results of this study confirm that a focus on sexual communication is justified in future intervention efforts with youth. By its very nature, condom use requires some level of cooperation or agreement between partners. This is particularly true for adolescent girls who may wish to initiate condom use but have less direct behavioral control over condoms than boys and are thus more reliant on verbal negotiation strategies (Amaro, 1995; Amaro & Raj, 2000). Effective interventions that increase adolescent girls’ sexual agency and assertiveness, and counteract those socialization forces that may serve to silence their voices in relationships, remain urgently needed. However, it would be wise to maintain an emphasis on communication and negotiation skills in future intervention efforts with all youth – not just girls. In fact, these interpersonal skills may be a major factor that distinguishes successful from unsuccessful intervention work (Johnson, Carey, Marsh, Levin, & Scott-Sheldon, 2003; Pedlow & Carey, 2004). The intervention literature would benefit from more systematic attention to communication skills, including the utilization of experimental designs that examine the incremental validity of adding communication components to an intervention (Kalichman et al., 2005). This literature would also benefit from additional attention to the various ways that communication skills could best be imparted to youth (Edgar, Noar, & Murphy, 2008). For example, studies should examine the relative efficacy of interpersonal formats such as role-plays, versus eHealth strategies such as online, computer-tailored, virtual decision-making, and mobile interventions (Noar, Pierce, & Black, 2010; Noar & Willoughby, 2012).

Limitations and Future Directions

Future work might address a number of issues that are not currently well addressed in the literature. Two notable limitations of current research on adolescent communication and condom use is that this body of work is relatively small – only 34 independent studies could be located, many with sample sizes less than 300 – and entirely cross-sectional; no studies included a longitudinal examination of sexual health communication and condom use. The small samples may have limited the power in this meta-analysis, although we believe this limitation was offset by the many significant findings, as well as the use of a fail-safe N (i.e., an additional 423 non-significant findings would be needed to reduce the observed correlation between communication and condom use to a trivial level). Yet, it remains possible that some of the non-significant moderating effects (for example, the timeframe during which condom use was measured or the type of population that was sampled) would have been significant had we had more power to detect such effects. Additionally, while the correlational results of this meta-analysis suggest that adolescents’ sexual communication may serve a health protective role by promoting or facilitating the use of condoms, it also is possible that using condoms increases adolescents’ likelihood of communicating about sex, or that third variables (e.g., safer sex self-efficacy, parental attitudes, characteristics of the sexual relationship) contribute to both sexual communication and condom use. While the results of this meta-analysis are a necessary first step in understanding the strength of the association between adolescents’ sexual communication and condom use (as well as moderators of this association), longitudinal designs will be necessary to unpack the directionality of the communication-condom use link. Following adolescent relationships over time can be difficult because these relationships are often short-lived; even still, attempts to use prospective designs and uncover patterns of communication and condom use over time and across various types of relationships would significantly advance the field. Event-level analyses, common to the study of alcohol and sexual risk behavior (Kiene, Barta, Tennen, & Armeli, 2009; Leigh, 2002), have been infrequently applied to sexual communication but also could be fruitful in offering a much more nuanced understanding of the way in which adolescents negotiate sexual situations.

In addition to helping address the issues raised above, event-level analyses could shed light on the instances in which sexual communication is not associated with condom use. Although sexual communication accounts for significant variance in condom use, the relationship between communication and condom use is far from perfect. Perhaps in some cases communication fails, whereas in other cases sexual communication is, in fact, an attempt to persuade partners not to use condoms (Oncale & King, 2001). In still other instances, communication may lead adolescents to feel more safe and secure in having unprotected intercourse, for example if the partners have discussed sexual history or HIV/STI testing and determined the risk of current infection to be low (Civic, 2000). More nuanced assessments – both quantitative and qualitative – are needed to better understand those instances when communication about sexual health is not positively related to safer sexual behavior.

Additionally, with the advent of cell phones and social media, it is clear that adolescent communication is increasingly mediated through technology (Uhls, Espinoza, Greenfield, Subrahmanyam, & Šmahel, 2011); yet, the empirical literature on sexual communication has not kept pace. More work is needed to understand if and how youth use technology to discuss sexual health issues with their partners, and whether this form of communication influences their sexual decision making processes (Widman, Nesi, Choukas-Bradley, & Prinstein, 2014). Finally, future research might consider additional moderators of the communication-condom use relationship that were not examined in the current group of studies. These could include individual characteristics, such as level of communication competence or personality traits (Noar, Zimmerman, Palmgreen, Lustria, & Horosewski, 2006), as well as relationship dynamics, such as the sexual experiences of the dyad, relationship trust or conflict, and the balance of relationship power (Amaro & Raj, 2000; Manning, Flanigan, Giordano, & Longmore, 2009; Tschann, Adler, Millstein, Gurvey, & Ellen, 2002).

When interpreting results of this meta-analysis, it should also be noted that the primary focus was on communication between adolescent partners and condom use. A broader literature also exists on communication between youth and their parents and peers/friends (Commendador, 2010; DiIorio et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2001; Short, Yates, Biro, & Rosenthal, 2005; Widman, Choukas-Bradley, Helms, Golin, Prinstein, 2014). This literature generally shows communication is positively associated with youth condom use, regardless of the source of communication (Aspy, Vesely, Oman, Rodine, Marshall, & McLeroy, 2007; DiIorio, Kelley, & Hockenberry-Eaton, 1999; Guzmán et al., 2003; Henrich, Brookmeyer, Shrier, & Shahar, 2006; Hutchinson & Montgomery, 2007), though there is some inconsistency across studies (Busse, Fishbein, Bleakley, & Hennessy, 2010; Hovell et al., 1994; L’Engle & Jackson, 2008). Additional empirical reviews that synthesize the literature on sexual communication between youth and their parents and/or friends would be a nice complement to the current study and enhance our understanding of the interpersonal factors that contribute to adolescent sexual decision-making. Additionally, our focus on condom use was chosen because condoms are the most effective means of reducing STIs among sexually active youth and they also offer protection from pregnancy (Holmes et al., 2004). However, there are a number of studies that have examined the associations between sexual communication and other forms of contraceptive use (Manlove, Ryan, & Franzetta, 2003, 2004; Stone & Ingham, 2002; Widman et al., 2006). It remains to be determined if communication has a similar impact on hormonal birth control use or dual-method use.

Figure 2.

Forest plot displaying effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals. mix = mixed gender sample; boys = all male sample/subsample; girls = all female sample/subsample. The size of marker in the forest plot indicates the weight of the study. The diamond indicates the overall weighted mean effect size (r = .24).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants K99 HD075654 and K24 HD069204. Additionally, this research was supported by the Social and Behavioral Science Core of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410). We sincerely wish to thank Marissa Esber for her help with the literature search and article coding.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

- *.Abraham C, Sheeran P, Spears R, Abrams D. Health beliefs and promotion of HIV-preventive intentions among teenagers: A Scottish perspective. Health Psychology. 1992;11:363–370. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.11.6.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M, Emmers-Sommer TM, Crowell TL. Couples negotiating safer sex behaviors: A meta-analysis of the impact of conversation and gender. In: Allen M, Preiss RW, Gayle BM, Burrell NA, editors. Interpersonal communication research: Advances through meta-analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H. Love, sex, and power: Considering women’s realities in HIV prevention. American Psychologist. 1995;50:437–447. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.50.6.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, Raj A. On the margin: Power and women’s HIV risk reduction strategies. Sex Roles. 2000;42:723–750. doi: 10.1023/A:1007059708789. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aspy CB, Vesely SK, Oman RF, Rodine S, Marshall L, McLeroy K. Parental communication and youth sexual behaviour. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:449–466. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Baele J, Dusseldorp E, Maes S. Condom use self-efficacy: Effect on intended and actual condom use in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28:421–431. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi JW, Celum C. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of personality. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- *.Barthlow DJ, Horan PF, DiClemente RJ, Lanier MM. Correlates of condom use among incarcerated adolescents in a rural state. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1995;22:295–306. doi: 10.1177/0093854895022003007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Basen-Engquist K, Mâsse LC, Coyle K, Kirby D, Parcel GS, Banspach S, Nodora J. Validity of scales measuring the psychosocial determinants of HIV/STD-related risk behavior in adolescents. Health Education Research. 1999;14:25–38. doi: 10.1093/her/14.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien S, Kajula LJ, Muhwezi WW. A review of studies of parent-child communication about sexuality and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Reproductive Health. 2011;8:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brown LK, DiClemente R, Crosby R, Fernandez MI, Pugatch D, Lescano C, Schlenger WE. Condom use among high-risk adolescents: Anticipation of partner disapproval and less pleasure associated with not using condoms. Public Health Reports. 2008;123:601–607. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Bryan A, Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Tests of the mediational role of preparatory safer sexual behavior in the context of the theory of planned behavior. Health Psychology. 2002;21:71–80. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse P, Fishbein M, Bleakley A, Hennessy M. The role of communication with friends in sexual initiation. Communication Research. 2010;37:239–255. doi: 10.1177/0093650209356393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers ES, Demmons S. Sexual satisfaction and sexual self-disclosure within dating relationships. Journal of Sex Research. 1999;36:180–189. doi: 10.1080/00224499909551983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casey MK, Timmermann L, Allen M, Krahn S, Turkiewicz KL. Response and self-efficacy of condom use: A meta-analysis of this important element of AIDS education and Prevention. Southern Communication Journal. 2009;74:57–78. doi: 10.1080/10417940802335953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010:59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2012. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Civic D. College students’ reasons for nonuse of condoms within dating relationships. Journal of Sexual and Marital Therapy. 2000;26:95–105. doi: 10.1080/009262300278678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Fleming TR. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commendador KA. Parental influences on adolescent decision making and contraceptive use. Pediatric Nursing. 2010;36:147–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Cobb BK, Harrington K, Davies SL, Oh MK. Condom use and correlates of African American adolescent females’ infrequent communication with sex partners about preventing sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy. Health Education & Behavior. 2002;29:219–231. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Salazar LF, Harrington K, Davies SL, Oh MK. Identification of strategies for promoting condom use: A prospective analysis of high-risk African American female teens. Prevention Science. 2003;4:263–270. doi: 10.1023/A:1026020332309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Salazar LF, Head S, Rose E, McDermott-Sales J. Sexual agency versus relational factors: A study of condom use antecedents among high-risk young African American women. Sexual Health. 2008;5:41–47. doi: 10.1071/sh07046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Deardorff J, Tschann JM, Flores E, Ozer EJ. Sexual values and risky sexual behaviors among Latino youths. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;42:23–32. doi: 10.1363/4202310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vet E, Gebhardt WA, Sinnige J, Van Puffelen A, Van Lettow B, de Wit JBF. Implementation intentions for buying, carrying, discussing and using condoms: The role of the quality of plans. Health Education Research. 2011;26:443–455. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.DePadilla L, Windle M, Wingood G, Cooper H, DiClemente R. Condom use among young women: Modeling the theory of gender and power. Health Psychology. 2011;30:310–319. doi: 10.1037/a0022871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L, Savin-Williams RC. Adolescent sexuality. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent sexuality. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2009. pp. 479–523. [Google Scholar]

- *.DiClemente RJ. Predictors of HIV-preventative sexual behavior in a high-risk adolescent population: The influence of perceived peer norms and sexual communication on incarcerated adolescents’ consistent use of condoms. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12:385–390. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(91)90052-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.DiClemente RJ, Lodico M, Grinstead OA, Harper G, Rickman RL, Evans PE, Coates TJ. African-American adolescents residing in high-risk urban environments do use condoms: Correlates and predictors of condom use among adolescents in public housing developments. Pediatrics. 1996;98:269–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Rose ES, Sales JM, Long DL, Caliendo AM, Crosby RA. Efficacy of sexually transmitted disease/human immunodeficiency virus sexual risk–reduction intervention for African American adolescent females seeking sexual health services: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:1112–1121. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.DiIorio C, Dudley WN, Kelly M, Soet JE, Mbwara J, Sharpe Potter J. Social cognitive correlates of sexual experience and condom use among 13- through 15-year-old adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29:208–216. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, Kelley M, Hockenberry-Eaton M. Communication about sexual issues: Mothers, fathers, and friends. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24:181–189. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, Pluhar E, Belcher L. Parent-child communication about sexuality: A review of the literature from 1980–2002. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention & Education for Adolescents and Children. 2003;5:7–32. doi: 10.1300/J129v05n03_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Donald M, Lucke J, Dunne M, O’Toole B, Raphael B. Determinants of condom use by Australian secondary school students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1994;15:503–510. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)90499-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East L, Jackson D, O’Brien L, Peters K. Use of the male condom by heterosexual adolescents and young people: literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;59:103–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar T, Noar SM, Murphy B. Communication skills training in HIV prevention interventions. In: Edgar T, Noar SM, Freimuth VS, editors. Communication perspectives on HIV/AIDS for the 21st century. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates/Taylor & Francis Group; 2008. pp. 29–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Gallupe O, Boyce WF, Fergus S. Non-use of condoms at last intercourse among Canadian youth: Influence of sexual partners and social expectations. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2009;18:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- *.Grossman C, Hadley W, Brown LK, Houck CD, Peters A, Tolou-Shams M. Adolescent sexual risk: Factors predicting condom use across the stages of change. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:913–922. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9396-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Lee J, McCarthy K, Michael SL, Pitt-Barnes S, Dittus P. Paternal influences on adolescent sexual risk behaviors: A structured literature review. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e1313–1325. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Gutiérrez L, Oh HJ, Gillmore MR. Toward an understanding of (em)power(ment) for HIV/AIDS prevention with adolescent women. Sex Roles. 2000;42:581–611. doi: 10.1023/A:1007047306063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Guzmán BL, Schlehofer-Sutton MM, Villanueva CM, Dello Stritto ME, Casad BJ, Feria A. Let’s talk about sex: How comfortable discussions about sex impact teen sexual behavior. Journal of Health Communication. 2003;8:583–598. doi: 10.1080/10810730390250425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Harrison A, Smit J, Hoffman S, Nzama T, Leu CS, Mantell J, Exner T. Gender, peer and partner influences on adolescent HIV risk in rural South Africa. Sexual Health. 2012;9:178–186. doi: 10.1071/SH10150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hart TA, Heimberg RG. Social anxiety as a risk factor for unprotected intercourse among gay and bisexual male youth. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9:505–512. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold ES, Way L. Self-disclosure among university women. Journal of Sex Research. 1988;24:1–24. doi: 10.1080/00224498809551394. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30042960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich CC, Brookmeyer KA, Shrier LA, Shahar G. Supportive relationships and sexual risk behavior in adolescence: An ecological-transactional approach. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:286–297. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes K, Levine R, Weaver M. Effectiveness of condoms in preventing sexually transmitted infections. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82:454–461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House LD, Bates J, Markham CM, Lesesne C. Competence as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:S7–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovell MF, Hillman ER, Blumberg E, Sipan C, Atkins C, Hofstetter CR, Myers CA. A behavioral-ecological model of adolescent sexual development: A template for AIDS prevention. Journal of Sex Research. 1994;31:267–281. doi: 10.1080/00224499409551762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MK, Montgomery AJ. Parent communication and sexual risk among African Americans. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2007;29:691–707. doi: 10.1177/0193945906297374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dodge T, Dittus P. Parent-adolescent communication about sex and birth control: A conceptual framework. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2002;97:9–41. doi: 10.1002/cd.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Carey MP, Marsh KL, Levin KD, Scott-Sheldon LA. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for the human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents, 1985–2000. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:381–388. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Cain D, Weinhardt L, Benotsch E, Presser K, Zweben A, Swain GR. Experimental components analysis of brief theory-based HIV/AIDS risk-reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection patients. Health Psychology. 2005;24:198–208. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz BP, Fortenberry JD, Zimet GD, Blythe MJ, Orr DP. Partner-specific relationship characteristics and condom use among young people with sexually transmitted diseases. Journal of Sex Research. 2000;37:69–75. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3813372. [Google Scholar]

- Kiene SM, Barta WD, Tennen H, Armeli S. Alcohol, helping young adults to have unprotected sex with casual partners: Findings from a daily diary study of alcohol use and sexual behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, Shaffer A, Forehand R. Adolescent sexual risk behavior: A multi-system perspective. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:493–519. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku L, Sonenstein FL, Pleck JH. The dynamics of young men’s condom use during and across relationships. Family Planning Perspectives. 1994;26:246–251. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2135889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L’Engle KL, Jackson C. Socialization influences on early dolescents’ cognitive susceptibility and transition to sexual intercourse. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18:353–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00563.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lear D. Sexual communication in the age of AIDS: The construction of risk and trust among young adults. Social Science and Medicine. 1995;41:1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC. Alcohol and condom use: A meta-analysis of event-level studies. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29:476–482. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil S, Byers ES. Dyadic assessment of sexual self-disclosure and sexual satisfaction in heterosexual dating couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2005;22:169–181. doi: 10.1177/0265407505050942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Magura S, Shapiro JL, Kang SY. Condom use among criminally-involved adolescents. AIDS Care. 1994;6:595–603. doi: 10.1080/09540129408258673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manlove J, Ryan KM, Franzetta K. Patterns of contraceptive use within teenagers’ first sexual relationships. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2003;35:246–255. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.246.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manlove J, Ryan KM, Franzetta K. Contraceptive use and consistency in U.S. teenagers’ most recent sexual relationships. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36:265–275. doi: 10.1363/3626504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Flanigan CM, Giordano PC, Longmore MA. Relationship dynamics and consistency of condom use among adolescents. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2009;41:181–190. doi: 10.1363/4118109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Yan KX. AIDS risk behaviours and correlates in teenagers attending sexually transmitted diseases clinics in Los Angeles. Genitourin Medicine. 1995;71:82–87. doi: 10.1136/sti.71.2.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metts S, Spitzberg BH. Sexual communication in interpersonal contexts: A script-based approach. In: Burleson BR, editor. Communication yearbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1996. pp. 49–91. [Google Scholar]

- Miller BC, Benson B, Galbraith KA. Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: A research synthesis. Developmental Review. 2001;21:1–38. doi: 10.1006/drev.2000.0513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM. An interventionist’s guide to AIDS behavioral theories. AIDS Care. 2007;19:392–402. doi: 10.1080/09540120600708469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Carlyle K, Cole C. Why communication is crucial: Meta-analysis of the relationship between safer sexual communication and condom use. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11:365–390. doi: 10.1080/10810730600671862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Cole C, Carlyle K. Condom use measurement in 56 studies of sexual risk behavior: Review and recommendations. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35:327–345. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Morokoff PJ, Harlow LL. Condom negotiation in heterosexually active men and women: Development and validation of a condom influence strategy questionnaire. Psychology & Health. 2002;17:711–735. doi: 10.1080/0887044021000030580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Pierce LB, Black HG. Can computer-mediated interventions change theoretical mediators of safer sex? A Meta-Analysis. Human Communication Research. 2010;36:261–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01376.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Willoughby JF. eHealth interventions for HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2012;24:945–952. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.668167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Zimmerman RS, Palmgreen P, Lustria M, Horosewski ML. Integrating personality and psychosocial theoretical approaches to understanding safer sexual behavior: Implications for message design. Health Communication. 2006;19:165–174. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1902_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncale RM, King BM. Comparison of men’s and women’s attempts to dissuade sexual partners from the couple using condoms. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2001;30:379–391. doi: 10.1023/A:1010209331697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Overby KJ, Kegeles SM. The impact of AIDS on an urban population of high-risk female minority adolescents: Implications for intervention. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1994;15:216–227. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)90507-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedlow CT, Carey MP. Developmentally appropriate sexual risk reduction interventions for adolescents: Rationale, review of interventions, and recommendations for research and practice. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:172–184. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2703_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Rickman RL, Lodico M, DiClemente RJ, Morris R, Baker C, Huscroft S. Sexual communication is associated with condom use by sexually active incarcerated adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1994;15:383–388. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)90261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- *.Roye CF. Condom use by Hispanic and African-American adolescent girls who use hormonal contraception. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;23:205–211. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S, Franzetta K, Manlove J, Holcombe E. Adolescents’ discussions about contraception or STDs with partners before first sex. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2007;39:149–157. doi: 10.1363/3914907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P, Abraham C, Orbell S. Psychosocial correlates of heterosexual condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:90–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Shoop DM, Davidson PM. AIDS and adolescents: The relation of parent and partner communication to adolescent condom use. Journal of Adolescence. 1994;17:137–148. doi: 10.1006/jado.1994.1014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Short MB, Yates JK, Biro F, Rosenthal SL. Parents and partners: Enhancing participation in contraception use. Journal of Pediatric Adolescent Gynecology. 2005;18:379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Shrier LA, Goodman E, Emans J. Partner condom use among adolescent girls with sexually transmitted diseases. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24:357–361. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Small E, Weinman ML, Buzi RS, Smith PB. Explaining condom use disparity among Black and Hispanic female adolescents. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2010;27:365–376. doi: 10.1007/s10560-010-0207-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Risk taking in adolescence: New perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:55–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00475.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review. 2008;28:78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone N, Ingham R. Factors affecting British teenagers’ contraceptive use at first intercourse: The importance of partner communication. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2002;34:191–197. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3097729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL. Dilemmas of desire: Teenage girls talk about sexuality. Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tortolero SR, Markham CM, Peskin MF, Shegog R, Addy RC, Escobar-Chaves SL, Baumler ER. It’s Your Game: Keep It Real: Delaying sexual behavior with an effective middle school program. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Troth A, Peterson CC. Factors predicting safe-sex talk and condom use in early sexual relationships. Health Communication. 2000;12:195–218. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1202_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschann JM, Adler NE, Millstein SG, Gurvey JE, Ellen JM. Relative power between sexual partners and condom use among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:17–25. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Tschann JM, Flores E, de Groat CL, Deardorff J, Wibbelsman CJ. Condom negotiation strategies and actual condom use among Latino youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhls YT, Espinoza G, Greenfield P, Subrahmanyam K, Šmahel D. Internet and other electronic media. In: Brown BB, Prinstein MJ, editors. Encyclopedia of adolescence. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2011. pp. 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- *.van Empelen P, Kok G. Condom use in steady and casual sexual relationships: Planning, preparation and willingness to take risks among adolescents. Psychology & Health. 2006;21:165–181. doi: 10.1080/14768320500229898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch Cline RJ, Johnson SJ, Freeman KE. Talk among sexual partners about AIDS: Interpersonal communication for risk reduction or risk enhancement? Health Communication. 1992;4:39–56. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc0401_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *.Whitaker DJ, Miller KS, May DC, Levin ML. Teenage partners’ communication about sexual risk and condom use: The importance of parent-teenager discussions. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;31:117–121. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2991693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Helms SW, Golin CE, Prinstein MP. Sexual communication between early adolescents and their dating partners, parents, and best friends. Journal of Sex Research. 2014 doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.843148. Online First. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Nesi J, Choukas-Bradley S, Prinstein MP. Safe Sext: Adolescents’ use of technology to communicate about sexual health with dating partners. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;54:612–614. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Golin CE, Noar SM. When do condom use intentions lead to actions? Examining the role of sexual communication on safer sexual behavior among people living with HIV. Journal of Health Psychology. 2013;18:507–517. doi: 10.1177/1359105312446769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L, Welsh DP, McNulty JK, Little KC. Sexual communication and contraceptive use in adolescent dating couples. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:893–899. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Wilson MD, Kastrinakis M, D’Angelo LJ, Getson P. Attitudes, knowledge, and behavior regarding condom use in urban Black adolescent males. Adolescence. 1994;29:13–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman RS, Noar SM, Feist-Price S, Dekthar O, Cupp PK, Anderman E, Lock S. Longitudinal test of a multiple domain model of adolescent condom use. Journal of Sex Research. 2007;44:380–394. doi: 10.1080/00224490701629506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]