Abstract

Background

Prior reports have linked both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke to use of sympathomimetic drugs including phenylephrine.

Objective

To describe the first case, to our knowledge, of intracerebral hemorrhage following oral use of phenylephrine and to systematically review the literature on phenylephrine and acute stroke.

Methods

A case report and review of the literature.

Results

A 59-year-old female presented with thunderclap headache, right hemiparesis, aphasia, and left gaze deviation. Head CT showed a left frontal intracerebral hemorrhage with intraventricular and subarachnoid extension. She had no significant past medical history. For the previous thirty days, the patient was taking multiple common cold remedies containing phenylephrine to treat sinusitis. CT and MR angiography showed no causative vascular abnormality. Catheter cerebral angiography supported reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Phenylephrine was determined to be the most likely etiology for her hemorrhage.

A review of the literature, found 7 cases describing phenylephrine use with acute stroke occurrence: female 5/7 (71%); route of administration: nasal (n=3); ophthalmic (n=2); intravenous (n=1); intracorporeal injection (n=1). Stroke types were: subarachnoid hemorrhage (n=5); ICH (n=4); ischemic (n=1). One case reported reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome after phenylephrine use.

Conclusion

It is scientifically plausible that phenylephrine may cause strokes, consistent with the pharmacological properties and adverse event profiles of similar amphetamine-like sympathomimetics. As reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome has been well-described in association with over-the-counter sympathomimetics, a likely, although not definitive, causal relationship between phenylephrine and intracerebral hemorrhage is proposed.

Keywords: hemorrhagic stroke, phenylephrine, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, sympathomimetics

Introduction

Over the past 45 years, there have been a large number of case reports, case series, autopsies, and epidemiological studies associating stroke and cerebrovascular disease with use of both illicit and over-the-counter (OTC) sympathomimetic drugs, including phenylephrine (PHE).1,2

Sympathomimetic drugs, such as PHE, are commonly used as a decongestant and are main components in OTC cold medications. The mechanism by which PHE and other sympathomimetic drugs used as decongestants produce their biological effect is through activation of selected alpha-adrenergic receptors found on very small blood vessels of the nasal mucosa.3 The receptors may be activated via direct binding of the sympathomimetic agents to the binding site of the receptor, or by enhanced release of norepinephrine, producing vasoconstriction.3,4 When PHE and other alpha-adrenergic agonists are taken systemically in doses sufficient to constrict blood vessels in the nasal mucosa, they can also have similar effects on blood vessels in other parts of the body as well. Oral decongestants have been demonstrated to affect the cardiovascular, urinary, central nervous and endocrine systems.5 Both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes have been reported, occurring from early childhood into the elderly, and in both males and females.1,6,7

Prior reports have linked both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke to parenteral, nasal spray and topical ocular use of PHE. To our knowledge, we report the first case of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) occurring after oral administration of PHE.

Case Report

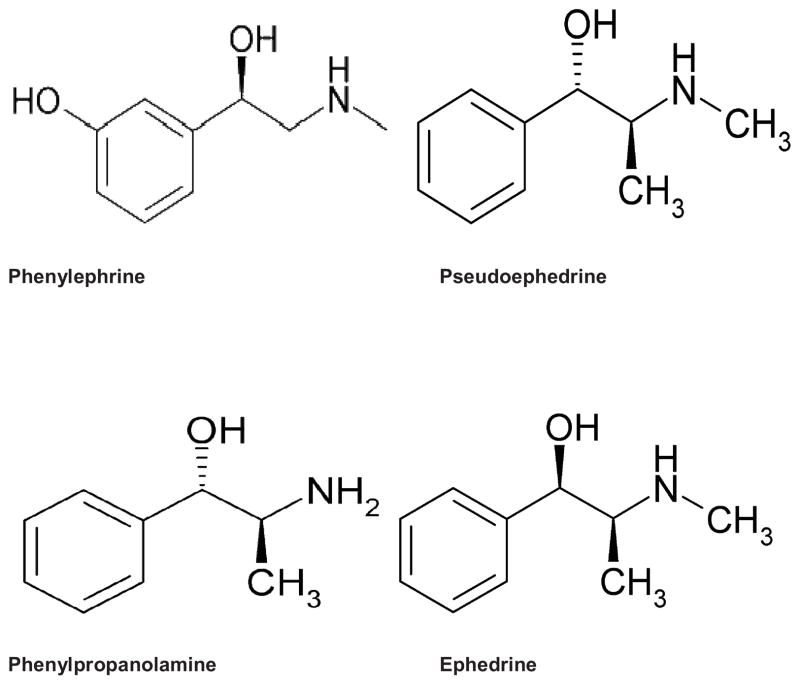

A 59 year-old female presented to her primary care physician complaining of a severe headache, which started the day before and progressively worsened. During the clinic visit, she developed right-sided hemiparesis, aphasia, and left gaze deviation. She was transferred to the Emergency Department where a non-contrast CT scan of the brain showed a left hemispheric ICH with intraventricular and subarachnoid extension (Figure 1). Her blood pressure on admission was 149/69 mmHg and her oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. The results of blood counts, aPTT, PT and INR, and serum electrolytes, were all normal, except for a potassium of 2.8 mmol/L. The patient had no significant past medical history, specifically, no hypertension, diabetes, smoking or documented brain vascular malformations. For the previous thirty days, the patient was taking multiple oral OTC common cold remedies to treat chronic sinus headache. For 4 days leading up to her hospitalization she only took cold medications that contained PHE as its decongestant. Most of the cold medications also contained acetaminophen, dextromethorphan, and chlorpheniramine as active ingredients. She did report that she took an oral decongestant containing pseudoephedrine (PE) within thirty days of the stroke, but with very limited use. She reported that she never took more than the maximum recommended dose and usually used small doses when treating her sinusitis with oral decongestants. The patient was not taking any prescription medications on a regular basis. She had no history of alcohol or illicit drug abuse.

Figure 1.

Head CT displaying fronto-parietal ICH with intraventricular involvement.

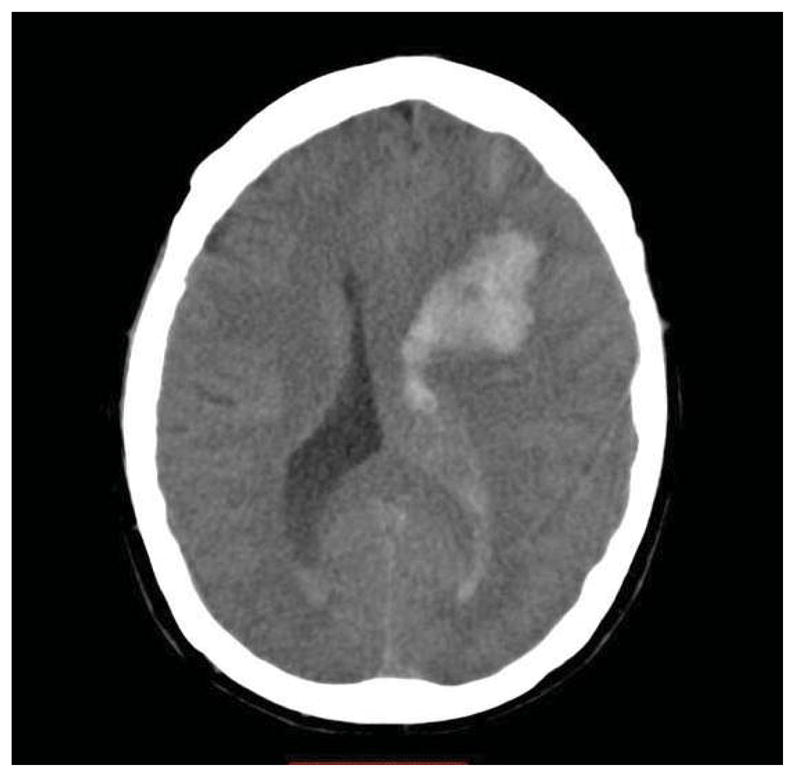

Initial CT and MR angiography showed no causative vascular abnormality. Catheter cerebral angiography suggested reversible cerebral vasoconstrictive syndrome (RCVS) based on the finding of multiple subtle segmental areas of narrowing in distal arteries (Figure 2). Brain biopsy at the time of surgical evacuation of the ICH showed no cerebral amyloid angiopathy, vascular malformation, or vasculitis. Laboratory tests, including measurements of ESR and antinuclear antibodies (ANA) were normal. Follow-up CT angiograms were performed twice during her admission and were both normal, without vasospasm or narrowing, thus supporting the diagnosis of a transient vasculopathy.

Figure 2.

Lateral view cerebral angiogram showing diffuse segmental vasoconstriction.

Phenylephrine was determined to be the most likely etiology for her ICH given the close temporal relationship between ingestion and onset of symptoms. She was discharged twenty-two days after admission to a rehabilitation center with bowel and urinary incontinence, ataxia, right sided weakness, and expressive aphasia. Her symptoms improved and she was discharged to home after seventy-two days. After twenty-seven months, her symptoms continue to improve, but still maintains residual ataxia, right sided weakness, and expressive aphasia.

Discussion

Published literature support a causal relationship between use of sympathomimetic drugs and the occurrence of both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.1 Cases, such as this one, where there is a close temporal relationship between ingestion and onset of symptoms and where other probable etiologies are excluded, are particularly suggestive.

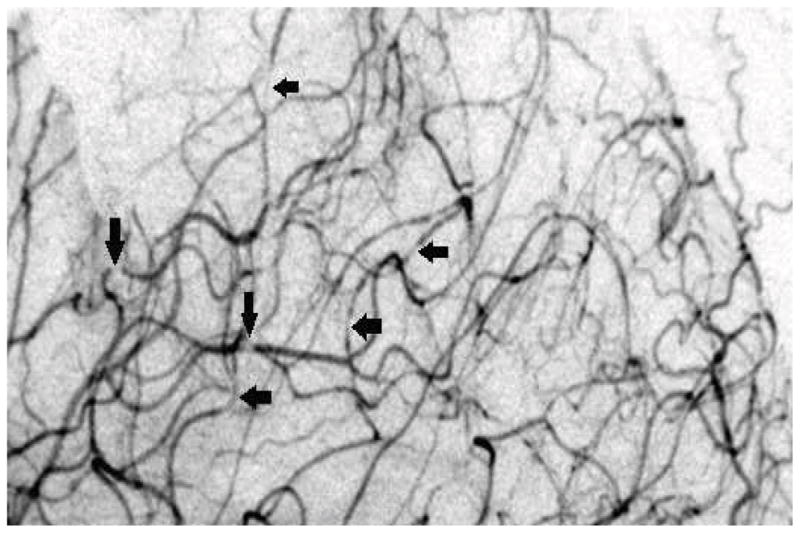

Oral decongestants including phenylpropanolamine (PPA) and PE have been linked to anecdotal cases of stroke,1 but there have been no prior reports of oral PHE associated with stroke.

In the absence of other possible etiologies and given the chronic and concurrent use of cold remedies all containing PHE, we propose that PHE was the cause of ICH in our case. Over-the-counter sympathomimetics are associated with reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS).8–11 Our case had angiographic evidence of RCVS further supporting the etiology of her ICH from PHE-induced RCVS.

Phenylephrine (Figure 3) has similar pharmacologic characteristics and side effects to other adrenaline-like sympathomimetics4 and prior published case reports1,12–17 and animal studies18,19 suggest a relationship between administration - IV, intranasal and topical - and occurrence of stroke.

Figure 3.

Systematic literature review

We performed a review of the literature to identify cases of stroke attributed to PHE use. We performed a PUBMED search (current as of October 15, 2013), using the terms: “Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstrictive Syndrome”, “Phenylephrine”, “Sympathomimetics”, and “Over-The-Counter Cold Medications” matched together with the following terms: “Stroke”, and “Hemorrhage”. We reviewed all abstracts and reviewed the full articles of all case descriptions. We reviewed all references from these articles. We found 7 cases (summarized in table 1).

Table 1.

Published cases of stroke and RCVS related to PHE

| Authors (year) | Population (age, yrs.) | Route of Administration | Type of Stroke/RCVS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cantu (2003) | Male (57) | Nasal spray taken daily TID for 4 months | ICH and SAH, and occipital infarct. |

| Chartier (1997) | Female (30) | Nasal spray daily for one week | SAH |

| Genonceaux (2011) | Female (45) | Nasal spray | SAH |

| Cass (1979) | Female (49) | Opthalmic 1 drop of 10% in each eye | Rupture of a cerebral aneurysm, SAH |

| Weisberg (1993) | Female (72) | Opthalmic 1 drop of 2.5% in each eye | ICH |

| Davila (2008) | Male (23) | Intracorporeal injection | SAH |

| Ranasinghe (2008) | Female (35) | Intravenous injection | ICH |

| Abruzzo (2012) | Female (1) | Intravenous injection | RCVS |

ICH = intracerebral hemorrhage

SAH = subarachnoid hemorrhage

RCVS= Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstrictive Syndrome;

PHE = Phenylephrine

Three cases reported stroke after nasal use. Cantu et al1 previously described a case of a 57-year-old man using PHE intranasal spray daily for 4 months developing a hypertensive crisis (240/110 mmHg) 3 hours before the onset of stroke symptoms. Neuroimaging showed evidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), ICH and an occipital infarct. A 30-year-old woman developed pyramidal tract signs and cerebral arterial beading nineteen days postpartum, having taken nasal pulverization of PHE for one week prior.12 A 45-year-old normotensive heavy smoker used nasal PHE extensively for weeks for cold symptoms and complained of sudden severe headache. CT showed SAH and CTA showed an intracerebral aneurysm.13

Two cases of stroke were reported after topical ocular use. A rupture of a cerebral aneurysm causing fatal SAH has been described 45 minutes after 1 drop of 10% ophthalmic PHE in each eye.14 Weisberg15 reported a case of ICH 30 minutes following PHE topical administration (1 drop of 2.5% in each eye). Systemic effects of topical ocular PHE (10%) have been reported to include severe hypertension, “cerebrovascular accident”, severe headache, tonic convulsion, and SAH among others (cardiac arrhythmias/arrest) and can occur after a single exposure within minutes.20

One case of stroke after intracorporeal injection was also reported. Subarachnoid hemorrhage was described shortly following intracorporeal injection of PHE for priapism in a young person with sickle cell disease.16

One case of stroke following intravenous use was reported. A 35-year-old female developed hypertension within 2 minutes of PHE administration and complained of a severe headache with head CT showing an ICH in the external capsule.17

Phenylephrine infusion in rabbits can increase cerebral blood flow and blood pressure, increasing vascular resistance and may rupture weak vessels in premature infants.18 In newborn beagle puppies, intravenous PHE caused increases in systemic blood pressure, intraventricular hemorrhage, and subependymal hemorrhage.19

Only until recently has PHE been more commonly used as an OTC decongestant because of its inability to be converted in to methamphetamine4 and with PPA taken off the market because of its ICH risk.21

Oral PHE has very poor bioavailability of 38%22,23 compared to the 90% of pseudoephedrine22 due to extensive first pass metabolism. Pharmacodynamic studies have shown a threshold of around 45 mg of oral PHE to cause significant systemic cardiovascular effects,24,25 but these studies define cardiovascular effects by changes in blood pressure and heart rate. These studies have only looked at the effects on short term use and did look at possible side effects of chronic ingestion. The FDA approved its use with 10 mg doses. Recent evidence suggests that acetaminophen can increase phenylephrine blood levels significantly26 with relevance to our case who took over 600mg of acetaminophen with the phenylephrine.

There is very limited data in the literature linking PHE specifically to RCVS. In our case report there was evidence of RCVS based on the findings on cerebral angiogram. The patient presented with severe headache and imaging showed multifocal diffuse narrowing of the cerebral arteries that was believed to be related to a PHE vasoconstrictive effect. Only one case27 documented RCVS after PHE IV use. Among the 62 cases studied by Ducros et al,10 OTC vasoactive nasal decongestants were one of the 3 most common vasoactive substances associated with RCVS. This syndrome can occur suddenly, especially in middle-aged women, with more than half the cases occurring after exposure to a vasoactive drug or postpartum.28 RCVS may occur after single dose of a vasoactive drug or after long-term exposure of normal or excessive doses.10 Intracerebral hemorrhage occurs in 14–25% of RCVS in literature reviews and retrospective series.10 In our case the patient was taking PHE contained decongestants for numerous months and daily for four days prior to the stroke with her last dose taken on the day of her hospital admission.

Conclusion

The ability of PHE to cause strokes is scientifically plausible - consistent with the pharmacological properties and adverse event profiles of similar amphetamine-like sympathomimetics. As RCVS has been well-described in association with OTC sympathomimetics, these lines of evidence support a likely, although not definitive, causal relationship between PHE and ICH. Further surveillance monitoring and research are needed to confirm this potentially deleterious effect of PHE.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by: NIH grants R01HL096944, U10NS077378, and U10NS080377. Dr. Balucani was supported by The American Heart Association FDA Summer 2012 Postdoctoral Fellowship 13POST14770052, Founders Affiliate and the 2013 Lawrence M. Brass Stroke Research Postdoctoral Fellowship sponsored by the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association and the American Brain Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cantu C, Arrauz A, Murillo-Bonilla LM, Lopez M, Barinagarrementeria F. Stroke associated with sympathomimetics contained in over-the-counter cough and cold drugs. Stroke. 2003;34:1667–1673. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000075293.45936.FA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haller CA, Benowitz NL. Adverse cardiovascular and central nervous system events associated with dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1833–1838. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012213432502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dollery C. Therapeutic Drugs. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eccles R. Substitution of phenylephrine for pseudoephedrine as a nasal decongestant. An illogical way to control methamphetamine abuse. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2007;63:10–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson DA, Hricik JG. The pharmacology of α-adrenergic decongestants. Pharmacotherapy. 1993;13:110S–115S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton RS, Sharieff G. Phenylpropanolamine-associated intracranial hemorrhage in an infant. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;8:343–345. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(00)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoessl AJ, Young GB, Feasby TE. Intracerebral hemorrhage and angiographic beading following ingestion of catecholaminergics. Stroke. 1985;16:734–737. doi: 10.1161/01.str.16.4.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bousser MG, Good J, Kittner SJ, Silberstein SD. Wolff’s Headache and Other Head Pain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. Headache associated with vascular disorders; pp. 349–392. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calabrese LH, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Singhal AB. Narrative review: reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:34–44. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-1-200701020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ducros A, Boukobza M, Porcher R, Sarov M, Walade D, Bousser M-G. The clinical and radiological spectrum of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. A prospective series of 67 patients. Brain. 2007;130:3091–2101. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singhal AB. Cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2004;11:16. doi: 10.1310/ATK7-QTP7-7NE2-5G8X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chartier JP, Bousigue JY, Teisseyre A, Morel C, Delpuech-Formosa F. Postpartum cerebral angiopathy of iatrogenic origin. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1997;153:212–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genonceaux S, Cosnard G, Van De Wyngaert F, Hantson P. Early ischemic lesions following subarachnoid hemorrhage: common cold remedy as precipitating factor? Acta Neurol Belg. 2011;111:59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cass E, Kadar D, Stein HA. Hazards of phenylephrine topical medication in persons taking propranolol. CMA Journal. 1979;120:1261–1262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisberg LA. Intracerebral hemorrhage after topical administration of mydriatic agents. Southern Medical Journal. 1993;86:1064–1066. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199309000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davila HH, Parker J, Webster JC, Lockhart JL, Carrion RE. Subarachnoid hemorrhage as complication of phenylephrine injection for the treatment of ischemic priapism in a sickle cell disease patient. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1025–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ranasinghe JS, Kafi S, Oppenheimer J, Birnbach DJ. Hemorrhagic stroke following elective cesarean delivery. International J Obstet Anesthesia. 2008;17:271–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koyama K, Mito T, Suzuki S. Effects of phenylephrine and dopamine on cerebral blood flow, blood volume, and oxygenation in young rabbits. Pediatr Neurol. 1990;6:87–90. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(90)90039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goddard J, Lewis RM, Armstrong DL, Zeller RS. Moderate, rapidly induced hypertension as a cause of intraventricular hemorrhage in the newborn beagle model. J Pediatr. 1980;96:1057–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(80)80641-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraunfelder FW, Fraunfelder FT, Jensvold B. Adverse systemic effects from pledgets of topical ocular phenylephrine 10% Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:624–625. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01591-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, et al. Phenylpropanolamine and the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1826–1832. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012213432501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanfer I, Dowse R, Vuma V. Pharmacokinetics of oral decongestants. Pharmacotherapy. 1993;13(6 pt 2):116S–28S. 143S–6S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hengstmann JH, Goronzy J. Pharmacokinetics of 3H-phenylephrine in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1982;21:335–341. doi: 10.1007/BF00637623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chua SS, Benrimoj SI. Non-prescription sympathomimetic agents and hypertension. Med Toxicol. 1988;3:387–417. doi: 10.1007/BF03259892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keys A, Violante A. The cardio-circulatory effects in man of neo-synephrin. J Clin Invest. 1942;21:1–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI101270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atkinson H, Anderson B. Increased Phenylephrine Plasma Levels with Administration of Acetaminophen. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1171–1172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1313942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abruzzo T, Patino M, Leach J, Rahme R, Geller J. Cerebral vasoconstriction triggered by sympathomimetic drugs during intra-arterial chemotherapy. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;48:139–142. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ducros A. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. The Lancet Neurology. 2012;11:906–917. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]