Abstract

Background: Strategies to improve influenza vaccine protection among elderly individuals are an important research priority. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and exercise have been shown to affect aspects of immune function in some populations. We hypothesized that influenza vaccine responses may be enhanced with meditation or exercise training as compared with controls.

Results: No differences in vaccine responses were found comparing control to MBSR or exercise. Individuals achieving seroprotective levels of influenza antibody ≥160 units had higher optimism, less anxiety, and lower perceived stress than the nonresponders. Age correlated with influenza antibody responses, but not with IFNγ or IL-10 production.

Conclusion: The MBSR and exercise training evaluated in this study failed to enhance immune responses to influenza vaccine. However, optimism, perceived stress, and anxiety were correlated in the expected directions with antibody responses to influenza vaccine.

Methods: Healthy individuals ≥50 y were randomly assigned to exercise (n = 47) or MBSR (n = 51) training or a waitlist control condition (n = 51). Each participant received trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine after 6 weeks, and had blood draws prior to and 3 and 12 weeks after immunization. Serum influenza antibody, nasal immunoglobulin A, and peripheral blood mononuclear cell interferon-γ (IFNγ) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) concentrations were measured. Measures of optimism, perceived stress, and anxiety were obtained over the course of the study. Seroprotection was defined as an influenza antibody concentration ≥160 units. Vaccine responses were compared using ANOVA, t tests, and Kruskal–Wallis tests. The correlation between vaccine responses and age was examined with the Pearson test.

Keywords: aging, antibody, body mass index, cytokine, exercise, influenza vaccine, interferon-γ, interleukin-10, meditation, positive emotion, stress

Introduction

Influenza is a common acute respiratory illness with substantial morbidity and mortality, particularly among older adults.1 The seasonal influenza vaccine is effective for the prevention of infection in younger adults, but may promote inadequate defense in up to 1/3 of the elderly, especially the frail in nursing homes.2 Strategies to improve protection provided by immunization continue to be a high research and public health priority. Seroprotection is traditionally defined as an antibody concentration at least 40 hemagglutination units (HAU) following influenza vaccination.3 However, this concentration of antibody confers protection from infection at a rate of about 50%. Protection from infection improves with higher antibody responses,4-7 although little further clinical benefit results from concentrations higher than 150 HAU.8 For this study, we used a HAU of 160 as the criterion of seroprotection where protection levels may reach 95%.8

Both antibody and cell-mediated immunity are important for conferring protection from influenza virus infection.9 Immune mechanisms involved in these pathways have been reported to be modulated by several psychological domains, including stress and depression10-15 and declines in immunity are commonly found with aging once past 60 y of age.16,17 In addition, during the 2009 influenza H1N1 pandemic, obesity was identified as another risk factor for influenza morbidity and mortality.18 The high prevalence of obesity in the United States prompts questions regarding its influence on immune responses to influenza vaccines, and also the potential benefits of exercise regimens.

Our study evaluated two interventions targeted toward these psychological and life style domains, with the goal of determining their potential value for improving the response to influenza vaccine in older individuals. Preliminary evidence from other reports had indicated that both meditation, including the method of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) employed in our project, and moderate intensity exercise may be at least partially effective in enhancing immunity following immunization.14,15,19-21 Most previous projects, however, had not been able to rigorously compare two interventions with random assignment. Using the controlled methods of a randomized design, we compared the antibody responses following training in MBSR or exercise to the responses generated by age- and gender-matched community controls who were assigned to an observational waitlist. We also examined age, body mass index, and psychological characteristics of the study participants as predictors of antibody and cytokine responses to influenza vaccine.

Results

One-hundred fifty-four healthy individuals were enrolled in the study and 149 completed the entire study. Demographic measures were similar across all three groups (Table 1). Follow-up for both cohorts continued through May 2010. The participants were quite healthy. Similar numbers of participants in each group received an influenza vaccine the prior season. The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-12) scores were high compared with the national norms for individuals of this age.22

Table 1. Participant demographics for the 3 arms of the MEPARI trial.

| Control | Meditation | Exercise | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject number | 51 | 51 | 47 |

| Male (%) | 10 (20%) | 9 (18%) | 8 (17%) |

| Influenza vaccine last season (%) | 37 (73%) | 33 (65%) | 26 (55%) |

| SF-12 physical (SD) | 50.0 (9.3) | 50.7 (9.4) | 50.9 (9.3) |

| SF-12 mental (SD) | 51.1 (7.8) | 50.9 (8.6) | 52.3 (6.6) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 58.8 (6.8) | 60.0 (6.5) | 59.0 (6.6) |

| Range | 50–76 | 50–72 | 50–73 |

| Body mass index (mean ± SD) | |||

| Baseline | 29.8 ± 6.8 | 29.0 ± 6.0 | 29.0 ± 6.9 |

| 3 weeks post-immunization | 29.8 ± 6.7 | 28.3 ± 7.2 | 29.0 ± 6.7 |

| 3 mo post-immunization | 29.8 ± 6.8 | 28.4 ± 7.3 | 29.1 ± 6.9 |

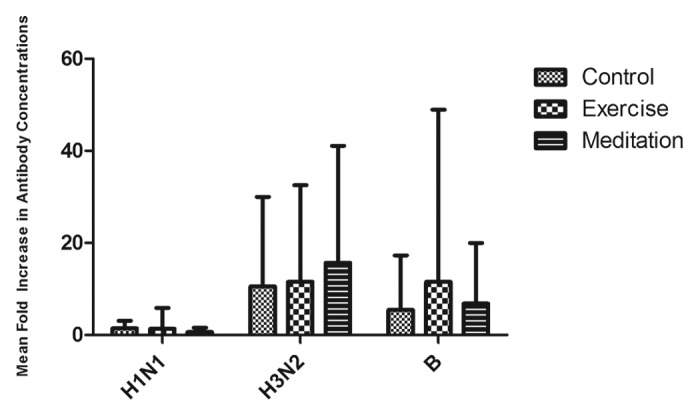

Influenza antibody responses were high in all three groups, and no significant improvement was found due to exercise or MBSR training (Fig. 1; Table 2). The overall seroprotection and seroconversion rates, defined as response to any single virus in the vaccine, were 96% and 74%, respectively, across all groups. Similar numbers of individuals had pre-immunization antibody concentrations that were below detection. We found no significant between-group differences in nasal IgA concentrations or cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from the vaccinated individuals.

Figure 1. Mean-fold (± SD) increase in antibody concentrations following influenza vaccination. There were no significant group differences in the antibody responses of individuals randomly assigned to control, MBSR or exercise conditions.

Table 2. Immune responses following influenza immunization.

| Control | Meditation | Exercise | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 51 | 51 | 47 | |

| Mean fold increase (change from baseline to 3 weeks post; SD) | ||||

| A/Brisbane H1N1 | 1.43 (1.67) | 1.34 (4.55) | 0.65 (0.95) | 0.36 |

| A/Brisbane H3N2 | 10.54 (19.41) | 11.51 (21.00) | 15.70 (25.38) | 0.47 |

| B/Brisbane | 5.44 (11.85) | 11.53 (37.41) | 6.84 (13.14) | 0.41 |

| Geometric mean titer baseline | ||||

| A/Brisbane H1N1 | 22.7 (40.0) | 20.3 (40.0) | 25.7 (40.0) | 0.40 |

| A/Brisbane H3N2 | 37.1 (56.6) | 30.9 (56.6) | 31.0 (40.0) | 0.62 |

| B/Brisbane | 16.2 (10.0) | 14.3 (10.0) | 14.8 (10.0) | 0.57 |

| Geometric mean titer 3 weeks post | ||||

| A/Brisbane H1N1 | 68.7 (26.2) | 67.8 (30.0) | 84.0 (33.4) | 0.64 |

| A/Brisbane H3N2 | 211.1 (40.0) | 155.6 (38.6) | 215.6 (41.1) | 0.41 |

| B/Brisbane | 53.5 (26.4) | 50.3 (32.0) | 55.8 (28.3) | 0.94 |

| Geometric mean titer 3 mo post | ||||

| A/Brisbane H1N1 | 61.1 (27.4) | 60.2 (28.3) | 62.3 (27.9) | 0.98 |

| A/Brisbane H3N2 | 149.3 (39.5) | 122.1 (35.1) | 152.4 (38.6) | 0.65 |

| B/Brisbane | 47.2 (28.5) | 39.5 (30.7) | 46.6 (26.9) | 0.64 |

| Seroprotection (antibody titer ≥ 1:40) | ||||

| A/Brisbane H1N1 | 43/51 (84%) | 39/51 (76%) | 38/47 (81%) | 0.61 |

| A/Brisbane H3N2 | 45/47 (96%) | 44/51 (86%) | 47/51 (92%) | 0.24 |

| B/Brisbane | 31/47 (66%) | 32/51 (63%) | 31/47 (73%) | 0.56 |

| Seroconversion (4 fold increase in antibody titer) | ||||

| A/Brisbane H1N1 | 22/51 (43%) | 21/51 (41%) | 21/47 (45%) | 0.94 |

| A/Brisbane H3N2 | 32/51 (63%) | 29/51 (57%) | 32/47 (68%) | 0.52 |

| B/Brisbane | 23/51 (45%) | 19/51 (37%) | 20/47 (43%) | 0.72 |

| Seroprotection | ||||

| 1 virus | 50/51 (98%) | 47/51 (92%) | 46/47 (98%) | 0.23 |

| 2 viruses | 46/51 (90%) | 40/51 (78%) | 39/47 (83%) | 0.27 |

| 3 viruses | 31/51 (61%) | 28/51 (55%) | 29/47 (62%) | 0.76 |

| Seroconversion | ||||

| 1 virus | 39/51 (76%) | 33/51 (65%) | 38/47 (81%) | 0.17 |

| 2 viruses | 25/51 (49%) | 24/51 (47%) | 24/47 (51%) | 0.92 |

| 3 viruses | 13/51 (25%) | 12/51 (24%) | 11/47 (23%) | 0.96 |

| IgA from nasal wash 3 weeks; milliunits/ng total IgA (IQR*) | 1.3 (2.2) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.6 (2.5) | 0.26 |

| Interferonγ production 3 weeks post; median (IQR*) pg/ml | ||||

| A/Brisbane H1N1 | 489 (2013) | 492 (1968) | 934 (1809) | 0.96 |

| A/Brisbane H3N2 | 6 (189) | 58 (169) | 1 (253) | 0.99 |

| B/Brisbane | 593 (2975) | 613 (2500) | 1153 (2926) | 0.91 |

| Interleukin-10 production; median (IQR) pg/ml | ||||

| A/Brisbane H1N1 | 62 (249) | 72 (224) | 65 (113) | 0.79 |

| A/Brisbane H3N2 | 1 (34) | 1 (47) | 1 (20) | 0.14 |

| B/Brisbane | 81 (140) | 98 (132) | 93 (132) | 0.75 |

*IQR, interquartile range.

However, there were consistent and significant differences in the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), Life Orientation Test (LOT), Spielberger’s State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-1 State and STAI-1 Trait) scores between those who mounted a seroprotective response of at least 160 HAU to at least one viral antigen and those who did not (Table 3). We found only a few and inconsistent correlations between cytokine production and optimism or perceived stress. Interferon-γ (IFNγ) production at 3 weeks post-vaccine was weakly correlated with optimism (r = −0.19, P = 0.025) and perceived stress (r = 0.17, P = 0.043) at baseline, but in different directions. In addition, IFNγ production at 3 weeks also correlated with optimism at the same time point (r = −0.18, P = 0.03). No significant correlations between psychological traits and IgA were found. The only significant correlation identified with specific antibody levels was an association between H1N1 antibody at baseline and the optimism score at 3 mo (r = −0.17, P = 0.039).

Table 3. Seroprotection at least 160 HAU and measures of well-being.

| Seroprotection (160 to at least one virus) n = 106 |

No seroprotection (160 to at least one virus) n = 43 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOT Baseline | 27.86 + 3.73 | 26.63 + 3.38 | 0.063 |

| LOT 3 weeks | 28.88 + 4.16 | 27.44 + 3.22 | 0.044 |

| LOT 3 mo | 28.94 + 3.98 | 27.30 + 4.70 | 0.032 |

| PSS Baseline | 11.27 + 5.23 | 13.36 + 5.62 | 0.032 |

| PSS 3 weeks | 9.63 + 5.77 | 12.35 + 6.16 | 0.012 |

| PSS 3 mo | 10.35 + 6.27 | 12.37 + 6.81 | 0.084 |

| MAAS 3 weeks | 4.66 + 0.66 | 4.39 + 0.82 | 0.036 |

| STAI Y-1 State Baseline | 29.98 + 7.50 | 33.14 + 9.29 | 0.031 |

| STAI Y-1 Trait Baseline | 32.73 + 7.48 | 36.15 + 8.15 | 0.015 |

| STAI Y-1 Trait 3 weeks | 30.14 + 13.44 | 34.81 + 9.64 | 0.040 |

| STAI Y-1 Trait 3 mo | 32.17 + 8.81 | 35.21 + 10.29 | 0.071 |

| SF12 Physical Baseline | 50.77 + 9.24 | 49.88 + 9.53 | 0.60 |

| SF12 Physical 3 weeks | 51.37 + 9.03 | 49.48 + 8.27 | 0.24 |

| SF12 Physical 3 mo | 50.06 + 16.49 | 49.86 + 9.42 | 0.97 |

| SF12 Mental Baseline | 51.95 + 7.62 | 50.16 + 7.86 | 0.20 |

| SF12 Mental 3 weeks | 51.93 + 7.79 | 50.36 + 9.09 | 0.29 |

| SF12 Mental 3 mo | 47.98 + 16.80 | 47.55 + 8.95 | 0.87 |

Means + standard deviations; two sided t tests; SPSS V20. Seroprotection defined as an antibody response attaining at least 160 hemagglutination units (HAU)

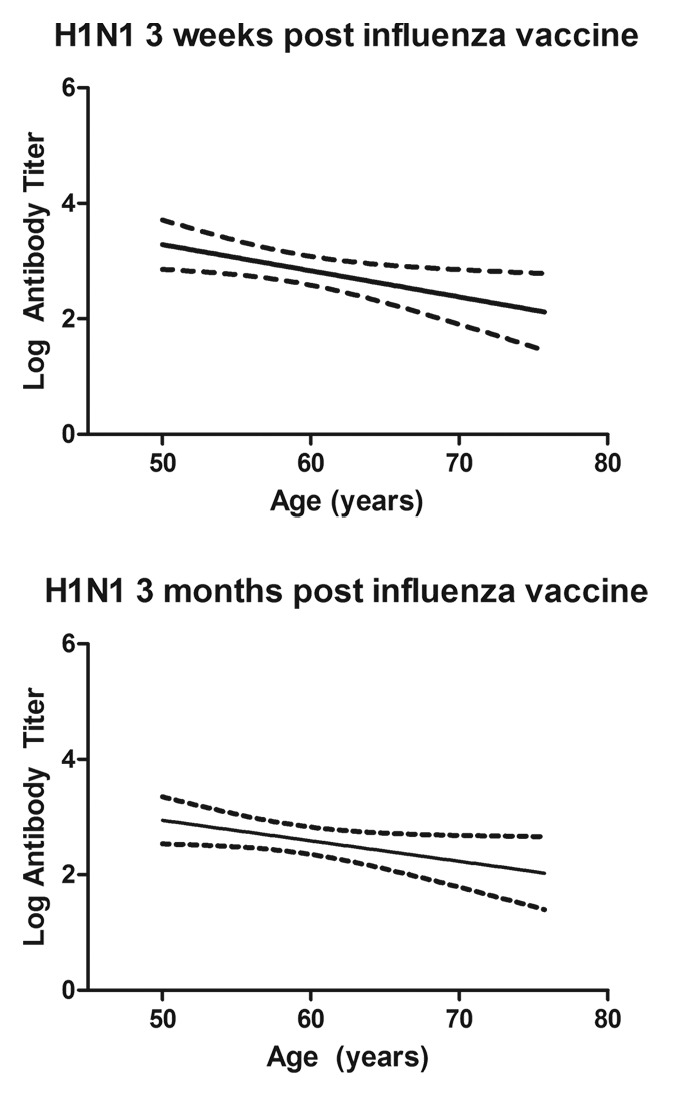

Increasing age was generally correlated with smaller antibody responses in this study population. However, the observed decline in antibody with age was subtle and not statistically significant for all viral antigens and time points examined. Nevertheless, even the correlations that did not reach the traditional P ≤ 0.05 for statistical significance all trended in the predicted direction (Fig. 2; Table 4). Increasing age also influenced the peak IgA concentrations found in nasal washes following immunization. However, the correlation at the 3-mo time point was not statistically significant. No significant correlations between age and vaccine-specific cytokine production were identified.

Figure 2. Influenza antibody responses post-immunization were negatively correlated with increasing age of participants. The relationship was generally consistent for the three antigens in the trivalent vaccine. However, this figure shows just the correlations between age and antibody to A/H1N1 influenza antigen at 3 weeks and 3 mo following vaccination.

Table 4. Pearson tests of age correlation with antibody response to influenza vaccination at 3 and 12 weeks post-immunization.

| Correlation coefficient | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| A/H1N1 3 weeks | −0.20 | <0.020 |

| A/H1N1 12 weeks | −0.16 | 0.054 |

| A/H3N2 3 weeks | −0.13 | 0.10 |

| A/H3N2 12 weeks | −0.05 | 0.52 |

| B 3 weeks | −0.30 | <0.0005 |

| B 12 weeks | −0.22 | <0.01 |

| Normalized IgA 3 weeks | −0.17 | 0.044 |

| Normalized IgA 12 weeks | −0.013 | 0.88 |

BMI did not change after either intervention condition, despite the 2-mo period of exercise training. Therefore, BMI at baseline was used for comparison with vaccine responses. BMI was not significantly correlated with any of the immune parameters, including HIA following immunization (data not shown).

Discussion

Perhaps in part because of the robust immunization responses shown by most participants to this very effective trivalent vaccine, none of the immune measures we assessed were further improved by training in exercise or MBSR. Neither virus-specific antibody responses (IgG, IgA) nor PBMC cytokine responses (IFNγ, IL-10) were statistically different among the three groups. The similarity in the measured immune responses among the groups is noteworthy. The parent study, from which the current data were derived, showed that both exercise and MBSR reduced the number of days sick from all-cause acute respiratory infection (ARI) illness.23 The incidence, duration and global severity of ARI illness episodes were decreased by 33–35% and 31–60%, among those assigned to MBSR and exercise training as compared with control. Nevertheless, the influenza vaccine generated similar, and what would be considered protective and clinically effective responses in most participants in this study cohort. Only two cases of pandemic influenza A/H1N1, a viral strain not included in the seasonal vaccine, were detected. Both of these influenza infections were in the control group.23 Because the rather dramatic reduction in ARI illness induced by the behavioral interventions was not accompanied by clear differences in adaptive immune responses to vaccination, we hypothesize that the main preventative benefits of the training likely occurred because of innate immune processes, or may be due to other changes in acquired immunity that we did not measure. Unfortunately, our assay strategy did not focus on those pathways. In addition, many of the ARI illnesses were caused by other common respiratory pathogens, including rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, adenoviruses, metapneumovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus.23 One limitation of our study protocol was that we did not include a good measure of adherence to meditation practice beyond attendance at the meditation classes. The participants randomized to the exercise group showed increases in IPAQ scores.

Antibody responses to influenza vaccine have been shown to correlate with protection against disease and mortality in large studies of vaccine efficacy.5,7,24,25 However, the specific immune mediators of protection are less well understood. A complex cascade of immune responses is likely to be required to control virus replication, including early memory T-cell responses along with antibody production interacting with innate immune components, such as natural killer cells and immunomodulatory signaling from interferons. Infection with influenza virus is largely localized to the respiratory mucosa where the activity of antibody and interferon, as well as other cellular activity within tissue may look different than the systemic responses measured by our assays.

Although our investigation did not replicate reports that meditation and exercise can improve responses to vaccines, several of the found associations between the participants’ psychological status and antibody responses are consistent with previous reports.10,14 In our study, those who mounted seroprotection responses of at least 160 HAU reported less perceived stress, were more optimistic, and had lower anxiety. Although the magnitude of these between-group differences were small, the likely validity and strength of these findings is enhanced by the remarkable consistency at all three times that psychological status was evaluated across the follow-up period (Table 3). The LOT, PSS-10, and STAI are not intended for clinical use so no benchmarks can be directly linked with diagnosis or pathology.26-29 The psychological status of the vaccine low-responders was not markedly deviant or out of the normal range, thus indicating that the influence of cognitive and emotional factors does not require an older individual be clinically depressed or in a chronically stressful situation. In this way our study is different from other research looking for immune suppression in the elderly, which often focuses on chronic stress such as being a caregiver for a spouse with dementia.30 Similar relationships between psychological factors and immune markers have also been reported by Kohut et al. and Costanzo et al., although their participants were older and reported less optimism and more perceived stress.10,14,15 Our findings add to this research pointing toward important influences of stress, optimism, and anxiety on vaccine responses. Our findings are not fully explanatory, however, as surprisingly few differences or changes in optimism or perceived stress were induced by training in exercise or MBSR.23 The lack of a more salubrious impact may reflect our strict inclusion criteria, which required that the participants not have exercised regularly or engaged in any meditative practice prior to the study, and further that they were randomly assigned to the interventions rather than self-selecting a regimen of personal interest. It is known that belief in the value of an intervention or therapy can enhance its effectiveness.

Positive and negative emotional states and traits, including stress, anxiety, and optimism have been linked to biological health states, including immunity and respiratory infection.26,31-33 For example, the PSS-10 was used in an induced influenza A study, and was shown to predict symptom scores, mucus weight, IL-6 from nasal wash.34 As a clinical syndrome, anxiety is prevalent, leading to substantial public health impact and is associated with several illness states, including the common cold.35 To assess anxiety, the Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Scale28 has been used in numerous studies.36-38 The randomized trial of mindfulness meditation by Davidson et al. found improvement in Spielberger anxiety scores at the end of 8 weeks of MBSR training and 4 mo afterwards (P < 0.01), as well as an increase in IgG response to influenza vaccines.19 The Life-Orientation Test (LOT) is a brief measure of optimism which has demonstrated reasonable predictive and discriminant validity.27 Scheier and Carver have reported data showing independent associations to several health measures, relationships that exist even after controlling for these 2 more negative psychological dimensions.

Despite these reported associations, few prospective clinical studies have shown that mind-body practices aimed at stress and anxiety can influence the immune system response to reduce disease. Elderly individuals trained in Tai Chi Chih, a westernized version of Tai Chi that incorporates exercise, relaxation, and meditation into a single behavioral intervention, had improved responses to a varicella zoster vaccine as measured by T-cell responses.39 That study showed a health benefit from a combination of interventions, and the authors hypothesized that Tai Chi Chih could also augment immune responses to other vaccines in the elderly. In combination with our study, the results indicate that psychological status does contribute to immune vigor and vitality in older individuals.

Current evidence suggests that cell-mediated immune mechanisms may be as important as antibody concentrations in protection from influenza, and that these pathways may undergo senescence or become dysregulated with aging.9,17,40-44 For example, a recent study by McElhaney et al. reported that the ratio of IFN-γ to IL-10 measured in stimulated peripheral mononuclear blood cells predicted laboratory-confirmed influenza infection in immunized elderly individuals (vaccine failure), whereas levels of antibody specific to the vaccine antigens did not.9 Both IFN-γ and IL-10 have been associated with markers of psychological well-being in a small population of individuals in the same age range as the participants in this study.13 Our study of quite healthy individuals failed to make these associations. Cytokine production by older individuals who are repeatedly immunized has been shown to be lower,45 and this may explain our relatively low IFNγ and IL-10 responses to the H3N2 virus which was carried over from the previous season. Although the importance of cell-mediated mechanisms in protection from influenza is not disputed, we were unable to change cytokine production with either exercise or MBSR. We hypothesize that other measures of cell-mediated immunity may be more sensitive to these interventions.

A consistent relationship between increasing age and lower antibody concentrations was also identified in this cohort of older adults. These findings reaffirm the view that immunization strategies should be aimed toward the elderly, with protocols designed to enhance responses in the immunosenescent individual. The recently licensed, high dose, inactivated influenza vaccine could be an important contribution.46 However, until effectiveness data for that vaccine are available, the benefits of inducing even higher antibody concentrations for protection remain unknown. In animal models of aging and vaccination, it has also been shown that a dual immunization regimen could offer an alternative approach for enhancing antibody response to influenza vaccine in the aged host.47 Given that old age can also differentially affect the synthesis of the four primary IgG subsets, it is possible that we might have detected more of an influence of the interventions if we had assayed each IgG subset individually.48

The antibody responses of this community sample of older adults, which included many overweight individuals, also did not confirm recently reported associations between a high BMI and peak influenza antibody concentrations.49 But it should be noted that even in the published reports, BMI was not correlated with antibody levels at 3 mo post-immunization, only later at one year when a differential decline was detected by Sheridan et al.49 Our findings appear to concur with another study that also investigated the 2009–10 influenza vaccine, which failed to find a correlation between antibody responses and BMI.50 Similarly, we were unable to detect a correlation between obesity and virus-specific cytokine production.49

Most significantly, our study did not replicate the findings of Davidson and colleagues, who reported positive effects of MBSR on the incremental rise in IgG to influenza vaccination from month 1 to month 2.5 However, it should be emphasized that our community participants were very different than that study population, which was recruited from a local biotechnology company and included many younger adults. In addition, the actual differences in antibody responses reported in that paper were quite small, and were associated more with individual differences in brain activity and positive affect. The differences in study cohort and experimental design may explain why we failed to detect a similar benefit of meditation training in our randomized trial.19

Our clinical trial has several strengths and weaknesses. While other studies have compared either MBSR or exercise to control,15,19,20 this is the first randomized trial to assess the effects of both MBSR and exercise vs. control on the immune responses to influenza vaccine. The sample size of our study is both a strength and limitation. While about twice as large as previous studies,14,15,19-21 the statistical power to detect small differences between groups was still limited. Nevertheless, we can be reasonably confident that (1) the reported associations are real, and (2) that no between-group differences in immune biomarkers greater than 20% can be attributed to the MBSR or exercise interventions, as compared with control.

Conclusion

The trivalent influenza vaccine used during the 2009–2010 season was found to be very immunogenic, even in older adults. Training in MBSR or exercise for 2 mo did not further enhance vaccine responses, as indexed by several immune parameters. However, a novel finding from this study is that the participants’ self-reported optimism, perceived stress and anxiety at baseline were correlated in the expected directions with seroprotection at 160 HAU to influenza vaccine. In addition, as anticipated, older age was associated with lower antibody concentrations. Body weight did not appear to influence the measured immune responses, but it should be emphasized that morbidly obese individuals were not included. Although our behavioral interventions did not markedly improve adaptive immune response to influenza immunization, further research still needs to be done to explain the significant reductions in ARI illness seen after both interventions, which suggests that exercise and MBSR are effective ways to promote population health.

Patients and Methods

The design of this randomized trial with 3 experimental arms has been described in detail elsewhere.23 Briefly, healthy individuals aged 50 y and older were screened with a run-in phase and randomly assigned to exercise training or MBSR, or served as wait-list controls after giving their informed consent. The exercise and MBSR training programs were 8 weeks in length. The meditation intervention was derived from work by Jon Kabat-Zinn and others at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, where MBSR was developed. The standardized 8-week course includes weekly 2.5-hour group sessions and 45 min of daily at-home practice.51 The exercise program was designed and led by senior Exercise Physiology staff at the UW Health Sports Medicine Center, and was matched to the meditation program in terms of duration (8 weeks), contact time (weekly 2.5 hour group sessions), home practice (45 min per day), and location. Borg’s Rating of Perceived Exertion was used to guide participants toward moderate intensity, sustained exercise, with a target rating of 12 to 16 points on the 6-to-20 point scale.52

Trivalent, inactivated influenza vaccine (Sanofi-Pasteur, #U3197AB) was administered during week 6 of the training and prior to significant influenza activity in the area.53 Blood was drawn for baseline antibody concentrations and cytokine production at the time of randomization. Antibody concentrations and cytokine production were determined again at 3 and 12 weeks after immunization.

Influenza antibody concentrations were measured by hemagglutination inhibition assay (HIA) in samples taken at baseline and at 3 and 12 weeks after immunization. The laboratory staff performing the HIA used the standard microtiter techniques and was blinded to participant status. Briefly, the HIA detects influenza antibody present in human sera by quantifying the inhibition of virus-induced agglutination of guinea pig red blood cells (rbc). Titrated influenza antigen is incubated with serially diluted sera for 30 min. Guinea pig rbc are added and incubated for 45 min. The dilution of serum that no longer inhibits hemagglutination is used as an index of antibody titer. Antibody concentrations below the lower limit of detection (<1:10) were assigned a value of 1:1.54

IgA concentrations were measured by ELISA in nasal wash fluid collected prior to immunization in the second cohort, and at 3 and 12 weeks after immunization in both cohorts. Influenza-specific IgA (IB79250; IBL International) was normalized to total IgA (E80-102; Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.) in order to account for differences in wash volume.

To examine IFNγ and IL-10 production, PBMC were incubated in media (complete RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS). The cells were cultured at 106 cells per mL, and stimulated with viral antigens contained in the 2009–10 influenza vaccine (4 hemagglutination inhibition units of each virus: A/Brisbane/59/2007 [H1N1]-like, A/Brisbane/10/2007 [H3N2]-like, and B/Brisbane/60/2008-like; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) for 96 h. Cytokine in the supernatant was measured using ELISA (OptEIA Sets #55142 and #55157; PharMingen) (CV < 10%) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All ELISAs were done in duplicate and readings taken at 450 nm using SkanIt software for Thermo Multiskan Spectrum microplate readers (version 2.4.4). A standard curve was generated from the measured absorbance for the standards. For values above the curve, supernatant was diluted and re-assayed. Concentrations below the level of detection were assigned a value of 1 pg/mL.

Overall health was rated with the SF-12, a 12-item version of the SF-36, which provides algorithm-weighted physical and mental health scores.55 Stress, which has been linked previously to viral infection and symptoms, including influenza, was evaluated with a 10 item version of the PSS-10.26 The participants’ cognitive outlook and negative emotionality were assessed with the 6 item LOT27 and STAI, respectively.28 The SF-12 and PSS-10 were administered at baseline, 1 week post-intervention and monthly thereafter. The STAI and LOT were scored at baseline, 1 week post-intervention, and then again 3 months later.

Statistical Methods

The main study objective was to measure differences in antibody responses due to training in MBSR or exercise. Mean-fold increase in HIA was used as the primary outcome variable. Antibody responses were assessed with Analyses of Variance (ANOVA). A protective antibody response (seroprotection) to influenza vaccine is considered an antibody titer of at least 1:40. Because of the protective effect conferred by antibody concentrations up to 160 HAU, we also used a more stringent definition of seroprotection of >160 HAU.4-8 Seroconversion following influenza immunization implies at least a 4 fold increase in antibody concentrations.56,57 Seroprotection and seroconversion rates were compared using chi square tests. The sample size of 50 individuals per group provided in more than 90% power to detect a 25% difference in antibody responses between groups and 65% power to detect 20% difference in seroprotection between groups. The measures of psychological well-being were compared between the seroprotection and poor responder groups using unpaired t tests. Cytokine production was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis tests. The correlation between age and antibody production was evaluated using the Pearson test. Antibody responses between 4 BMI categories of underweight (<18.5), recommended weight (18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9), and obese (>30) were compared using ANOVA and Pearson correlations. SPSS V.20 was used for these statistical analyses.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Coe C, Muller D, Obasi CN, Barrett B, Ewers T and Backonja U have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Hayney M is a member of speakers’ bureau for Merck Vaccines.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an award from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM, 1R01AT004313) to Barrett B. Each of the co-authors contributed to the successful conduct of the MEPARI trial.

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01057771)

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BMI

body mass index

- HAI

hemagglutination inhibition assay

- HAU

hemagglutination inhibition units

- IL-10

interleukin-10

- IFNγ

interferon gamma

- LOT

Life Orientation Test

- SF-36

Medical Outcomes Study Short Form

- MBSR

mindfulness-based stress reduction

- PSS-10

Perceived Stress Scale

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- STAI

Speilberger’s State Trait Anxiety Inventory

References

- 1.Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, Finelli L, Euler GL, Singleton JA, Iskander JK, Wortley PM, Shay DK, Bresee JS, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-8):1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belongia EA, Kieke BA, Donahue JG, Coleman LA, Irving SA, Meece JK, Vandermause M, Lindstrom S, Gargiullo P, Shay DK. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in Wisconsin during the 2007-08 season: comparison of interim and final results. Vaccine. 2011;29:6558–63. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Guidance for Industry: clinical data needed to support the licensure of seasonal inactivated influenza vaccines 2007. http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/Vaccines/ucm074794.htm

- 4.Hannan SE, May JJ, Pratt DS, Richtsmeier WJ, Bertino JS., Jr. The effect of whole virus influenza vaccination on theophylline pharmacokinetics. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:903–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.4.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hobson D, Curry RL, Beare AS, Ward-Gardner A. The role of serum haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody in protection against challenge infection with influenza A2 and B viruses. J Hyg (Lond) 1972;70:767–77. doi: 10.1017/S0022172400022610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potter JM, O’Donnel B, Carman WF, Roberts MA, Stott DJ. Serological response to influenza vaccination and nutritional and functional status of patients in geriatric medical long-term care. Age Ageing. 1999;28:141–5. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao X, Hamilton RG, Weng NP, Xue Q-L, Bream JH, Li H, Tian J, Yeh SH, Resnick B, Xu X, et al. Frailty is associated with impairment of vaccine-induced antibody response and increase in post-vaccination influenza infection in community-dwelling older adults. Vaccine. 2011;29:5015–21. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coudeville L, Bailleux F, Riche BM. Francoise, Andre P, Ecohard R. Relationship between haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody titres and clinical protection against influenza: development and application of bayesian random-effects model. MBC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McElhaney JE, Xie D, Hager WD, Barry MB, Wang Y, Kleppinger A, Ewen C, Kane KP, Bleackley RC. T cell responses are better correlates of vaccine protection in the elderly. J Immunol. 2006;176:6333–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costanzo ES, Lutgendorf SK, Kohut ML, Nisly N, Rozeboom K, Spooner S, Benda J, McElhaney JE. Mood and cytokine response to influenza virus in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:1328–33. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.12.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fondell E, Lagerros YT, Sundberg CJ, Lekander M, Bälter O, Rothman KJ, Bälter K. Physical activity, stress, and self-reported upper respiratory tract infection. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:272–9. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181edf108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glaser R, Sheridan J, Malarkey WB, MacCallum RC, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Chronic stress modulates the immune response to a pneumococcal pneumonia vaccine. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:804–7. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200011000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayney MS, Love GD, Buck JM, Ryff CD, Singer B, Muller D. The association between psychosocial factors and vaccine-induced cytokine production. Vaccine. 2003;21:2428–32. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohut ML, Cooper MM, Nickolaus MS, Russell DR, Cunnick JE. Exercise and psychosocial factors modulate immunity to influenza vaccine in elderly individuals. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M557–62. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.9.M557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohut ML, Lee W, Martin A, Arnston B, Russell DW, Ekkekakis P, Yoon KJ, Bishop A, Cunnick JE. The exercise-induced enhancement of influenza immunity is mediated in part by improvements in psychosocial factors in older adults. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:357–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernstein E, Kaye D, Abrutyn E, Gross P, Dorfman M, Murasko DM. Immune response to influenza vaccination in a large healthy elderly population. Vaccine. 1999;17:82–94. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(98)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar R, Burns EA. Age-related decline in immunity: implications for vaccine responsiveness. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7:467–79. doi: 10.1586/14760584.7.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Intensive-care patients with severe novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection - Michigan, June 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:749–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidson RJ, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, Rosenkranz M, Muller D, Santorelli SF, Urbanowski F, Harrington A, Bonus K, Sheridan JF. Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:564–70. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000077505.67574.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohut ML, Arntson BA, Lee W, Rozeboom K, Yoon K-J, Cunnick JE, McElhaney J. Moderate exercise improves antibody response to influenza immunization in older adults. Vaccine. 2004;22:2298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vedhara K, Cox NK, Wilcock GK, Perks P, Hunt M, Anderson S, Lightman SL, Shanks NM. Chronic stress in elderly carers of dementia patients and antibody response to influenza vaccination. Lancet. 1999;353:627–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06098-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware J, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowke D, Gandek B. User's Manual for the SF-12v2 Health Survey. Boston: QualityMetric, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrett B, Hayney MS, Muller D, Rakel D, Ward A, Obasi CN, Brown R, Zhang Z, Zgierska A, Gern J, et al. Meditation or exercise for preventing acute respiratory infection: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:337–46. doi: 10.1370/afm.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hannoun C, Megas F, Piercy J. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of influenza vaccination. Virus Res. 2004;103:133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Potter CW, Oxford JS. Determinants of immunity to influenza infection in man. Br Med Bull. 1979;35:69–75. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen S, Tyrrell DAJ, Smith AP. Psychological stress and susceptibility to the common cold. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:606–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108293250903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–78. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodgues WF, Spielberger CD. An indicant of trait or state anxiety? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1969;33:430–4. doi: 10.1037/h0027813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D. Who's stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009. J Appl Psychol. 2012;42:1320–34. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, Malarkey WB, Sheridan J. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3043–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen S, Alper CM, Doyle WJ, Treanor JJ, Turner RB. Positive emotional style predicts resistance to illness after experimental exposure to rhinovirus or influenza a virus. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:809–15. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000245867.92364.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doyle WJ, Gentile DA, Cohen S. Emotional style, nasal cytokines, and illness expression after experimental rhinovirus exposure. Brain Behav Immun. 2006;20:175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-associated immune modulation: relevance to viral infections and chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Med. 1998;105(3A):35S–42S. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(98)00160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP. Psychological stress, cytokine production, and severity of upper respiratory illness. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:175–80. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adam Y, Meinlschmidt G, Lieb R. Associations between mental disorders and the common cold in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher PL, Durham RC. Recovery rates in generalized anxiety disorder following psychological therapy: an analysis of clinically significant change in the STAI-T across outcome studies since 1990. Psychol Med. 1999;29:1425–34. doi: 10.1017/S0033291799001336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quek KF, Low WY, Razack AH, Loh CS, Chua CB, KF Q Reliability and validity of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) among urological patients: a Malaysian study. Med J Malaysia. 2004;59:258–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vautier S, S V. A longitudinal SEM approach to STAI data:two comprehensive multitrait-multistate models. J Pers Assess. 2004;83:167–79. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8302_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Oxman MN. Augmenting immune responses to varicella zoster virus in older adults: a randomized, controlled trial of Tai Chi. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:511–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernstein ED, Gardner EM, Abrutyn E, Gross P, Murasko DM. Cytokine production after influenza vaccination in a healthy elderly population. Vaccine. 1998;16:1722–31. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(98)00140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McElhaney JE, Upshaw CM, Hooton JW, Lechelt KE, Meneilly GS. Responses to influenza vaccination in different T-cell subsets: a comparison of healthy young and older adults. Vaccine. 1998;16:1742–7. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(98)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Myśliwska J, Trzonkowski P, Szmit E, Brydak LB, Machała M, Myśliwski A. Immunomodulating effect of influenza vaccination in the elderly differing in health status. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1447–58. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar R, Burns EA. Age-related decline in immunity: implications for vaccine responsiveness. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7:467–79. doi: 10.1586/14760584.7.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burns EA. Effects of aging on immune function. J Nutr Health Aging. 2004;8:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang KS, Lee N, Shin MS, Kim SD, Yu Y, Mohanty S, Belshe RB, Montgomery RR, Shaw AC, Kang I. An altered relationship of influenza vaccine-specific IgG responses with T cell immunity occurs with aging in humans. Clin Immunol. 2013;147:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Falsey AR, Treanor JJ, Tornieporth N, Capellan J, Gorse GJ. Randomized, double-blind controlled phase 3 trial comparing the immunogenicity of high-dose and standard-dose influenza vaccine in adults 65 years of age and older. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:172–80. doi: 10.1086/599790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coe CL, Lubach GR, Kinnard J. Immune senescence in old and very old rhesus monkeys: reduced antibody response to influenza vaccination. Age (Dordr) 2012;34:1169–77. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9356-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stepanova L, Naykhin A, Kolmskog C, Jonson G, Barantceva I, Bichurina M, Kubar O, Linde A. The humoral response to live and inactivated influenza vaccines administered alone and in combination to young adults and elderly. J Clin Virol. 2002;24:193–201. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(01)00246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheridan PA, Paich HA, Handy J, Karlsson EA, Hudgens MG, Sammon AB, Holland LA, Weir S, Noah TL, Beck MA. Obesity is associated with impaired immune response to influenza vaccination in humans. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012;36:1072–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Talbot HK, Coleman LA, Crimin K, Zhu Y, Rock MT, Meece J, Shay DK, Belongia EA, Griffin MR. Association between obesity and vulnerability and serologic response to influenza vaccination in older adults. Vaccine. 2012;30:3937–43. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10:144–56. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borg G, Linderholm H. Perceived exertion and pulse rte during graded exercise in various age groups. Acta Med Scand. 1970;472:194–206. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1970.tb02901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update: influenza activity - United States, August 30, 2009-March 27, 2010, and composition of the 2010-11 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:423–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Centers for Disease Control. Advanced Laboratory Techniques for Influenza Diagnosis. Atlanta, BA: Public Health Service, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheak-Zamora NC, Wyrwich KW, McBride TD. Reliability and validity of the SF-12v2 in the medical expenditure panel survey. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:727–35. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levine M, Beattie BL, McLean DM, Corman D. Characterization of the immune response to trivalent influenza vaccine in elderly men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35:609–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1987.tb04335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phair J, Kauffman CA, Bjornson A, Adams L, Linnemann C., Jr. Failure to respond to influenza vaccine in the aged: correlation with B-cell number and function. J Lab Clin Med. 1978;92:822–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]