Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) is a global disease with increase in concern with growing morbidity and mortality after drug resistance and co-infection with HIV. Mother to neonatal transmission of disease is well known. Current recommendations regarding management of newborns of mothers with tuberculosis are variable in different countries and have large gaps in the knowledge and practices. We compare and summarize here current recommendations on management of infants born to mothers with tuberculosis. Congenital tuberculosis is diagnosed by Cantwell criteria and treatment includes three or four anti-tubercular drug regimen. Prophylaxis with isoniazid (3-6 months) is recommended in neonates born to mother with TB who are infectious. Breastfeeding should be continued in these neonates and isolation is recommended only till mother is infectious, has multidrug resistant tuberculosis or non adherent to treatment. BCG vaccine is recommended at birth or after completion of prophylaxis (3-6 months) in all neonates.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, congenital tuberculosis, perinatal transmission, prophylaxis, recommendations, therapy

Tuberculosis (TB) is a global public health problem, India and China together account for almost 40 per cent of the world's TB1. Congenital infection by vertical transmission is rare with only 358 cases reported till 1995 and another 18 cases reported from 2001 to 20052. High neonatal mortality (up to 60%) and morbidity warrant early diagnosis and treatment of newborns suffering from TB. Existing guidelines for management of the newborns delivered to mothers with TB are variable and have no uniform consensus. An electronic search was carried out at PubMed and Google search engine. The search was limited to literature published in the last 10 yr in English language only. The reference lists of all retrieved articles and guidelines were searched to further identify relevant articles. The key words used were “perinatal, neonatal, congenital, children, childhood, pregnancy, tuberculosis, management, treatment, guidelines” either singly or in different combinations. A manual search was done at both PubMed and Google for guidelines on tuberculosis by eminent organizations like World Health Organization (WHO), Centres for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP), Merck Manual, and national guidelines in countries like Britain National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), New Zealand (NZ), Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP) and Directly Observed Treatment Short course (DOTS) India, Southern African Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases (SASPID) and Malaysian Thoracic Society (MTS) to have worldwide representation. Relevant articles which provided reasonable information regarding the concerned questions were also included.

Mother to infant transmission of TB

Congenital infection by vertical transmission of TB is described by transplacental transmission through umbilical veins to the foetal liver and lungs; or aspiration and swallowing of infected amniotic fluid in utero or intrapartum causing primary infection of foetal lungs and gut. Transplacental infection occurs late in pregnancy and aspiration from amniotic fluid occurs in the perinatal period. The diagnostic criteria used for congenital tuberculosis were as described by Beitzke in 19353 and revised by Cantwell et al in 19944. Cantwell et al proposed diagnosis of congenital tuberculosis in the presence of proven tuberculous disease and at least one of the following; (i) lesions in the newborn baby during the first week of life; (ii) a primary hepatic complex or caseating hepatic granulomata; (iii) tuberculous infection of the placenta or the maternal genital tract; and (iv) exclusion of the possibility of postnatal transmission by investigation of contacts, including hospital staff. In newborns diagnosed of TB, a horizontal spread in the postpartum period by droplet or ingestion from mother or undiagnosed family member is most commonly suggested. Transmission of tuberculosis through breast milk does not occur5.

Clinical manifestations of congenital tuberculosis

Infertility, poor reproductive performance, recurrent abortions, stillbirths, premature rupture of membranes and preterm labour are known effects of tuberculosis in pregnancy. The foetus may have intrauterine growth retardation, low birth weight, and has increased risk of mortality. The median age of presentation of congenital TB is 24 days (range, 1 to 84 days)4. Clinical manifestations are non specific and include poor feeding (100%), fever (100%), irritability (100%), failure to thrive (100%), cough (88.9%), and respiratory distress (66.7%). Examination reveals hepatosplenomegaly (100%), splenomegaly (77.8%), and abdominal distension (77.8%)6. Lymphadenopathy (38%) lethargy (21%), meningitis, septicaemia, unresolving or recurrent pneumonia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, jaundice, ascitis, otitis media with or without mastoiditis (21%), parotitis, osteomyelitis, paravertebral abscess, cold abscess, and papular or pustular skin lesions (14%) are other known features7. Apnoea, vomiting, cyanosis, jaundice, seizures and petechiae have been reported in less than 10 per cent of cases8.

Investigations

Conventional methods: Diagnosis of TB in the newborn depends upon detailed history of maternal infection and high index of suspicion. Antenatal history by gynaecologists and trained nurses is beneficial in early diagnosis and determining neonatal outcome. Morphological and histological examination of placenta in suspected cases at the time of delivery is helpful. Screening of household contacts may yield source of infection. Clinical manifestations in neonates masquerade sepsis, prematurity, viral infections or other acute or chronic intrauterine infections and hence diagnosis is difficult and may be missed. Therefore, in the setting of poor response to antibiotics and supportive therapy, and negative results of microbiological evaluation and serological tests for acute and chronic intrauterine infections, TB should be suspected. Specimens from the neonate suitable for microscopy and culture include gastric aspirates, sputum (induced), tracheal aspirates (if mechanically ventilated), skin lesions, ear discharge, ascitic fluid, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and, pleural fluid (if present) for acid fast bacilli and cultured on standard egg based media for 12 wk)8,9,10. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is an important investigation and detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in BAL fluid by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is diagnostic in newborn11. Liver or lymph node biopsy may be undertaken for histology and culture. Postmortem biopsies (e.g. liver, lung, nodes, and skin lesions) can also be done. Conventional light microscopy (Ziehl-Neelsen or Kinyoun stain) or fluorescence microscopy (auramine stain) are used for detection of Mycobacterium. Chest radiography and computed tomography may show the presence of scattered infiltrates, bronchopneumonia, consolidation or periportal hypodensity which are non specific. Mantoux test if positive, is supportive evidence, but negative results do not rule out disease. Multiple and repeated investigations may be done in view of high suspicion5

Newer methods: Slow and tedious conventional methods have been recently replaced by quicker methods. The WHO has accredited LED (light emitting diode) flourescence microscopy and liquid based mycobacteria growth indicator tube (MGIT) in developed countries for fast results12. Indirect methods include rapid interferon gamma assays, QuantiFERON-TB Gold assay and T-SPOT using antigens ESAT-6, CFP-10 and TB7 but have shown inconsistent results in newborns13,14. Large trials using Gene Xpert (real time PCR) in children have been useful for rapid diagnosis in communities with a high burden of TB including multiple drug resistant (MDR) tuberculosis15. Other mycobacteriophage-based assays like Fast Plaque TB-Rif, molecular line probe assays (LPAs) such as GenoType MTBDR plus assay and the Inno-LiPA Rif TB assay are costly and with only a few studies in newborns16,17.

Management of neonate born to mother with tuberculosis

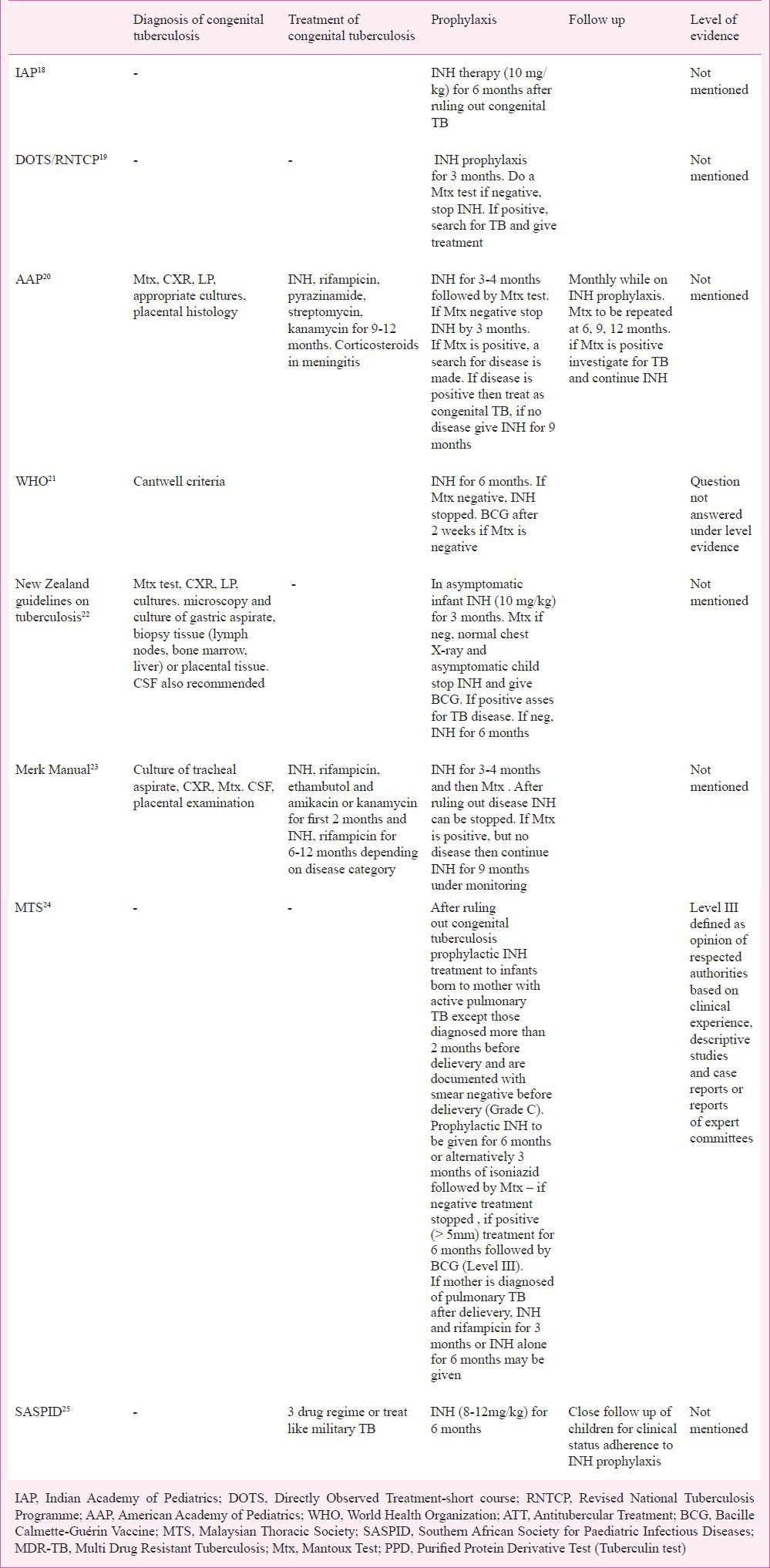

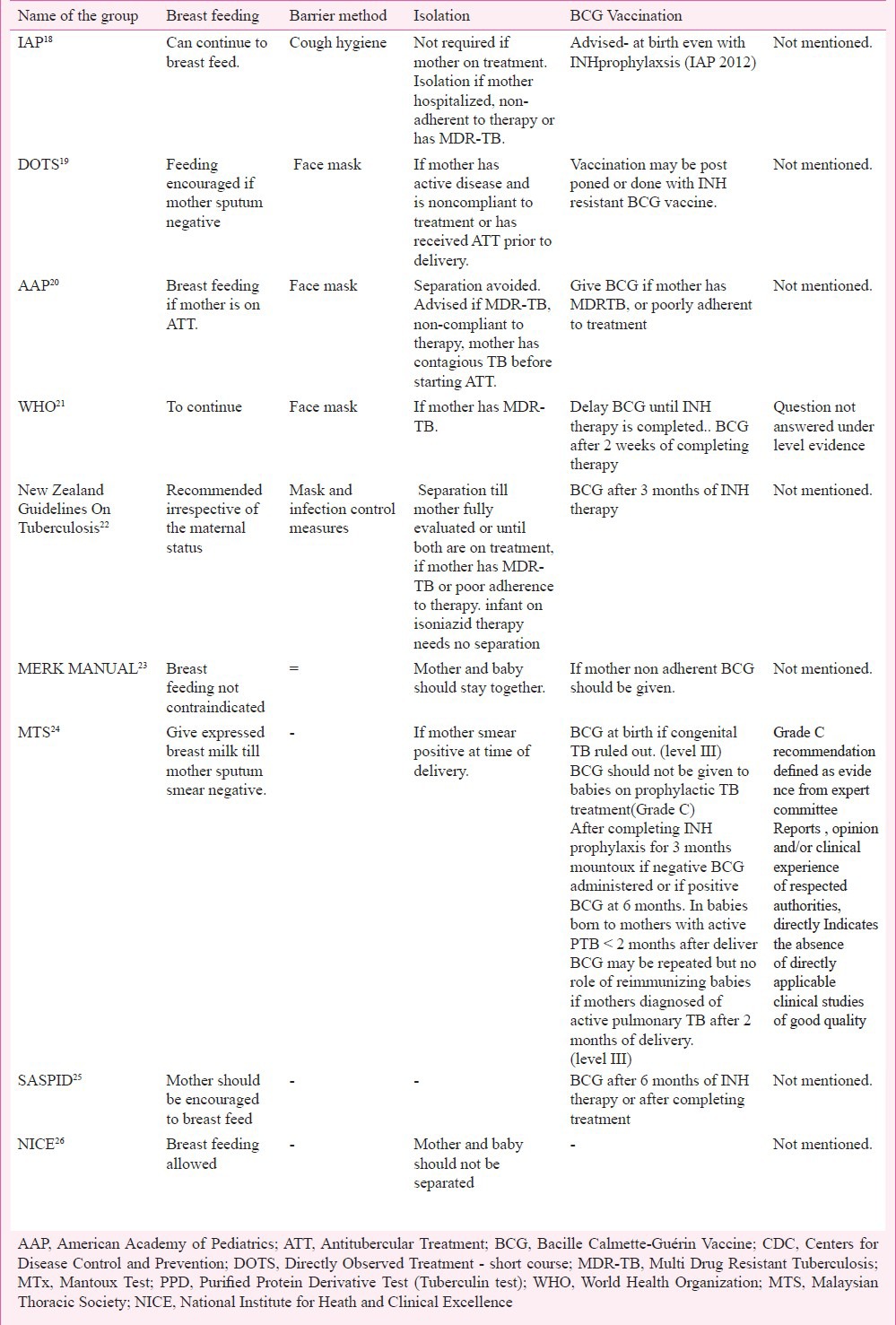

When a woman suffering from tuberculosis gives birth, the aim is to ensure TB free survival of her newborn infant. It involves diagnosing active tubercular lesion including congenital tuberculosis, and treatment of the neonate or prevention of transmission of tubercular infection to the neonate from the mother. There is no uniformity as is evident from the recommendations of the eminent societies of different countries across the globe (Tables I and II).

Table I.

Comparison of recommendations on prophylaxis, diagnosis and treatment guidelines by different groups

Table II.

Comparison of recommendations on isolation, breast-feeding and vaccination by different groups

(i) Prevention of transmission

(A) Maternal disease and therapy- Extrapulmonary, miliary and meningeal TB in mother are high risk factors for congenital TB in neonates27. Vertical transmission from mothers with tubercular pleural effusion or generalized adenopathy does not occur5. However, there is a lack of scientific literature regarding increased risk of congenital TB if mothers have resistant TB or concurrent HIV infection. Mothers who have completed antitubercular treatment (ATT) before delivery or have received ATT for at least two weeks duration before delivery are less likely to transmit the disease to the newborn as compared to untreated mothers. Antitubercular drugs are found to be safe in pregnancy except streptomycin in the first trimester. No literature is available regarding the safety of second line antitubercular drugs used for resistant TB in pregnancy28.

(B) Prophylaxis - The decision to start isoniazid (INH) prophylaxis to the neonate depends on a number of factors including the history of detection and duration of maternal disease (before or during or after pregnancy), type of tuberculosis (pulmonary or extrapulmonary), and maternal compliance of treatment (regular or irregular). INH prophylaxis is recommended in the neonate if the mother has received treatment for <2 wk, or those who are on therapy for >2 wk but are sputum smear positive. In all other situations there is no need of therapy. American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends INH prophylaxis to all neonates of mothers who are diagnosed with tuberculosis in the postpartum period and/or after the commencement of breastfeeding has started as these newborns are considered potentially infected20. Duration of prophylaxis is guided by skin testing by Mantoux test at three months in New Zealand22 and by WHO21, MERCK Manual23 and AAP20 or at 6 months in Malaysia and South Africa24,25. If Mantoux test is negative, prophylaxis is stopped. However, if Mantoux test is positive and evidence of disease is found, ATT is started. If there is no evidence of disease in Mantoux positive neonates, then INH may be given for six months20,22 or 9 months23. IAP does not comment on maternal treatment or Mantoux test and suggests isoniazid therapy to all newborns for at least 6-9 months or a minimum for three months until mother is culture negative18. There is also a variation in the dose recommended for prophylaxis with 5 mg/kg24, 15 mg/kg25, and 10 mg/kg20,23.

(C) Nutrition and breastfeeding - Support for breastfeeding is crucial for the survival of the newborn. Human milk in addition to providing nutrition has immunological benefits and all efforts to continue breastfeeding in newborns with mothers having tuberculosis should be made. In case of maternal sickness or if mother is smear positive at the time of delivery or mothers with MDR TB, when breastfeeding may not be possible, expressed breast milk feeding is an alternative, with personal hygiene. AAP recommends continued feeding with expressed milk in mothers with pulmonary TB who are contagious, untreated or treated (< 3 wk) with isolation20. WHO recommends feeding under all circumstances, however, close contact with the baby should be reduced21. Malaysian Thoracic Society recommends that if mother is contagious, efforts should be made to use expressed maternal milk for feeding24. There is a paucity of scientific literature on the increased risk of neonatal transmission by breastfeeding in the presence of factors such as infection with resistant organisms (multiple or extensive drug resistance or co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus. First line ATT is secreted in milk in small quantity and causes no adverse effect on the child29.

(D) Isolation and barrier nursing – Isolation is recommended when mother is sick, non adherent to therapy or has resistant TB18,20,21 or received ATT four less than 2 wk19,24 or three weeks before starting ATT20. Barrier nursing using face mask (20-22) and appropriate cough hygiene18 has been advised for the mothers who are breastfeeding. Hand washing, disinfecting nasal secretions and baby wipes are recommended by AAP20.

(ii) Diagnosis, treatment and follow up

(A) Mantoux test - Utility of Mantoux test in neonates is poor due to low reactogenicity and poor helper T cell responses. In a study by Hageman et al30 only two of the 14 infants with congenital TB had positive tuberculin tests. Current recommendations support use of Mantoux test after three months19,20,22 or six months24. Exact cut-off (> 5, 5-10 and >10 mm) and strength of purified protein derivative (PPD) (1 or 5 or 10 TU18,31) in newborns. IAP in the recent recommendations has decreased the strength of PPD for skin testing to 2 TU32.

(B) Treatment – No specific treatment regimens for congenital tuberculosis are advised. Treatment includes isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and kanamycin or amikacin for the first two months followed by isoniazid and rifampicin for 6-12 months23 or similar to miliary tuberculosis25 or isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide along with streptomycin and kanamycin for 9 to 12 months20.

(C) Follow up - Neonates diagnosed and treated for congenital tuberculosis should be monitored while on therapy21, but no details regarding the timing or the modes of monitoring exist. DOTS19 recommends chest X-ray at the end of treatment. American Academy of Pedaitrics suggested that infants receiving prophylaxis should have clinical surveillance20. In a study periodic X-ray and Mantoux test have been advised at 6, 12 and 24 wk28.

(iii) Long term protection

Bacillus Calmettee Guerin (BCG) vaccination protects against the dissemination of tuberculosis and severe disease. In neonates with congenital tuberculosis there is no utility of BCG vaccine. In neonates receiving INH prophylaxis, BCG vaccine (timing not specified) is recommended18,19. WHO recommends BCG vaccine until completion of INH therapy21. AAP has advised BCG vaccine after completion of chemoprophylaxis at six months or at birth along with isoniazid if follow up cannot be ensured20. The New Zealand guidelines22 recommend BCG after three months of prophylaxis while in South Africa SASPID recommends it after six months of prophylaxis. MTS24 recommends BCG vaccination after ruling out congenital TB and again after the INH prophylaxis if scar is absent. Indian Academy of Pedaitrics advises BCG vaccination at birth to all neonates after excluding congenital tuberculosis even if chemoprophylaxis is planned32. Hence it is evident that there is no consensus on the number, timing and interpretation of BCG vaccination in infants born to women with TB. In countries with significant number of TB patients in the community children are vulnerable to get TB infection early in life: Therefore, BCG vaccination as early as possible preferably after stopping of INH prophylaxis should be followed. There is an urgent need to conduct more studies to evaluate immunogenicity of BCG vaccine in infants receiving INH prophylaxis.

References

- 1.(WHO/HTM/TB/2012) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. Global Tuberculosis Report. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassang G, Qureshi W, Kadri SM. Congenital tuberculosis. JK Sci. 2006;8:193–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beitzke H. About congenital Tuberculosis infection. Ergeb Ges Tuberk Forsch. 1935;7:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantwell MF, Shehab ZM, Costello AM, Sands L, Green WF, Ewing EP, et al. Brief report: congenital tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1051–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404143301505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adhikari M, Jeena P, Bobat R, Archary M, Naidoo K, Coutsoudis A, et al. HIV-associated tuberculosis in the newborn and young infant. Int J Pediatr 2011. 2011:354208. doi: 10.1155/2011/354208. doi:10.1155/2011/354208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chotpitayasunondh T, Sangtawesin V. Congenital tuberculosis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86(Suppl 3):S689–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vallejo J G, Ong LT, Starke JR. Clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in infants. Pediatrics. 1994;94:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bate TW, Sinclair RE, Robinson MJ. Neonatal tuberculosis. Arch Dis Child. 1986;61:512–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.61.5.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zar HJ, Hanslo D, Apolles P, Swingler G, Hussey G. Induced sputum versus gastric lavage for microbiological confirmation of pulmonary tuberculosis in infants and young children: a prospective study. Lancet. 2005;365:130–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17702-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snider DE, Jr, Bloch AB. Congenital tuberculosis. Tubercle. 1984;65:81–2. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(84)90057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parakh A, Saxena R, Thapa R, Sethi GR, Jain S. Perinatal tuberculosis: four cases and use of broncho-alveolar lavage. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2011;31:75–80. doi: 10.1179/146532811X12925735813841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Policy statement. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Fluorescent light emitting diode (LED) microscopy for diagnosis of tuberculosis. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazurek GH, Villarino ME. CDC Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON --TB test for diagnosing latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:15–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quezada CM, Kamanzi E, Mukamutara J, De Rijk P, Rigouts L, Portaels F, et al. Implementation validation performed in Rawanda to determine whether the INNO-LiPA Rif. TB line probe assay can be used for detection of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in low-resource countries. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3111–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00590-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossau R, Traore H, De Beenhouwer H, Mijs W, Jannes G, De Rijk P, et al. Evaluation of the INNO-LiPA Rif. TB assay, a reverse hybridization assay for the simultaneous detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and its resistance to rifampin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2093–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Traore H, Fissette K, Bastian I, Devleeschouwer M, Portaels F. Detection of rifampicin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from diverse countries by a commercial line probe assay as an initial indicator of multidrug resistance. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4:481–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viveiros M, Leandro C, Rodrigues L, Almeida J, Bettencourt R, Couto L, et al. Direct application of the INNO -LiPA Rif.TB line-probe assay for rapid identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains and detection of rifampin resistance in 360 smear-positive respiratory specimens from an area of high incidence of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4880–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4880-4884.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar A, Gupta D, Nagaraja SB, Singh V, Sethi GR, Prasad J. Updated national guidelines for pediatric tuberculosis in India, 2012. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:301–6. doi: 10.1007/s13312-013-0085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.New Delhi: Central TB Division, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare; 2010. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare India. Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme: DOTS-Plus Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Academy of Pediatrics. Tuberculosis. In: Pickering LK, editor. Red book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012. pp. 736–56. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. 4th ed. Geneva: who; 2009. Treatment of tuberculosis guidelines. WHO/HTB/TB/2009.420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guidelines for tuberculosis control in New Zealand 2010. Wellington: MOH; 2010. Ministry of Health New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caserta MT. Perinatal tuberculosis. In: Porter RS, Kaplan JL, editors. The Merck Manual for health care professionals 2004. N.J., U.S.A: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.3rd ed. Putrajaya, Malaysia: 2012: Malaysia Health Technology Assessment Section (MaHTAS), Medical Development Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia; [accessed on April 18, 2014]. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Clinical practice guidelines: Management of tuberculosis. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.my . [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore DP, Schaaf HS, Nuttall J, Marais BJ. Childhood tuberculosis guidelines of the Southern African Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases. South Afr J Epidemiol Infect. 2009;24:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. London: National Institute for Health & Clinical Excellence; 2011. Clinical diagnosis and management of Tuberculosis and measures for its prevention and control. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruchfeld J, Aderaye G, Palme IB, Britton S, Feleke Y, et al. Evaluation of outpatients with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis in a high HIV prevalence setting in Ethiopia: clinical, diagnostic and epidemiological characteristics. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34:331–7. doi: 10.1080/00365540110080025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loto OM, Awowole I. Tuberculosis in pregnancy: a review. J Preg. 2012. Available from www,gubdiwu,cin/journals/jp/2012/379271 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Lamounier JA, Moulin ZS, Xavier CC. Recommendations for breastfeeding during maternal infections. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2004;80(5 suppl):S181–8. doi: 10.2223/1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hageman J, Shulman S, Schreiber M, Luck S, Yogev R. Congenital tuberculosis:critical reappraisal of clinical findings and diagnostic procedures. Pediatrics. 1980;66:980–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh D, Sutton C, Woodcock A. Tuberculin test measurement: variability due to the time of reading. Chest. 2002;122:1299–301. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.4.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Working Group on Tuberculosis, Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) Consensus statement on childhood tuberculosis. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:41–54. doi: 10.1007/s13312-010-0008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]