Abstract

Background:

Nonmedical sedative use is emerging as a serious problem in India. However, there is paucity of literature on the patterns of use in the population.

Aim:

The aim of the present analysis was to explore sedative use patterns in an urban metropolis.

Materials and Methods:

Data for the present analysis come from the parent study on nonmedical prescription drug use in Bengaluru, India. Participants (n = 717) were recruited using a mall-intercept approach, wherein they were intercepted in five randomly selected shopping malls, and administered an interview on their use of prescription drugs.

Results:

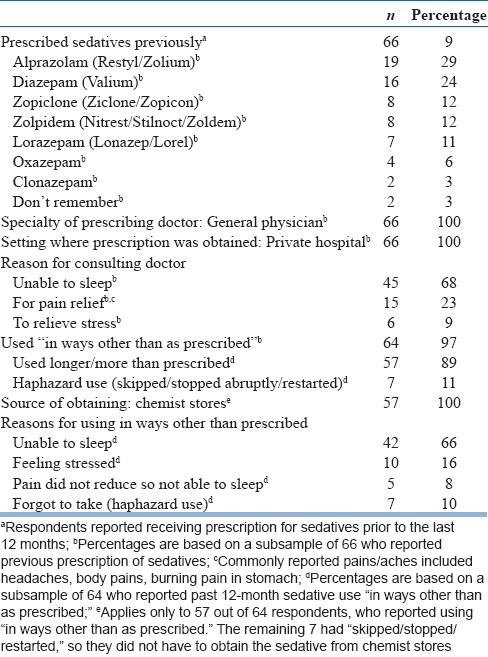

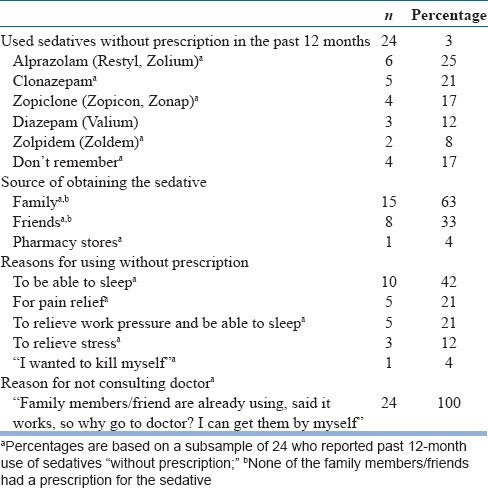

Past 12-month nonmedical sedative use was reported by 12%, benzodiazepines being the commonest. Reasons cited for nonmedical use included “sleeplessness, pain relief, stress.” A majority (73%) reported sedative use “in ways other than as prescribed,” compared to “use without prescription” (27%). All prescriptions were issued by general physicians in private hospitals. About 11% among those who used “in ways other than as prescribed,” and 100% of nonprescribed users, reported irregular use (skipping doses/stopping/restarting).

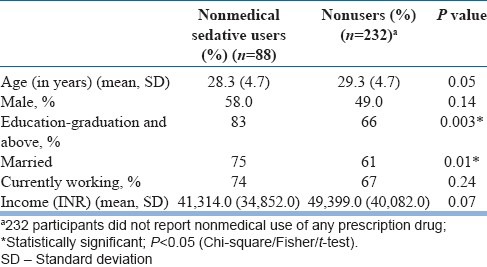

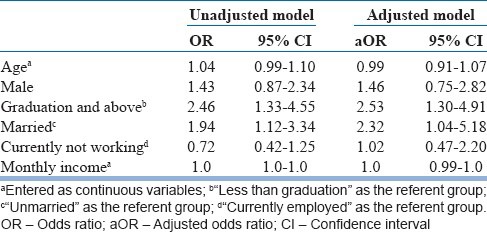

Among those who used “in ways other than prescribed,” pharmacy stores were the source of obtaining the sedatives. Among “nonprescribed users,” family/friends were the main source. Three-percent reported using sedatives and alcohol together in the same use episode. In multivariate logistic regression analyses, nonmedical sedative use was significantly associated with graduation-level education or above (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 2.53, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.30-4.91), and married status (aOR: 2.32, 95% CI: 1.04-5.18).

Conclusions:

Findings underscore the need for considering various contextual factors in tailoring preventive interventions for reducing nonmedical sedative use.

Keywords: Nonmedical sedative use, prescription drug misuse, sedative abuse, sedative misuse

INTRODUCTION

Nonmedical use of prescription medicines (operationalized as use “in ways other than as prescribed,” or “when not prescribed”) in developing countries is not a new phenomenon - it is as old as the advent of medications itself. However, it has also been one of the most under-studied issues in the arena of licit and illicit substance use. Although nonmedical use of pharmaceutical drugs has been steadily rising in the last decade across countries of South Asia, documented literature has been scarce, with prescription drugs being traditionally excluded from national drug use surveys.[1] The issue has not, by and large, caught the attention of mental health professionals as well - the assertion appears to be that there are more serious issues to focus on, such as alcohol and tobaccco use, or injection drug use. A nondata based report was released recently by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), that contained inputs from experts/policy makers to assess the nature and extent of the problem of pharmaceutical drug use in South Asia.[1] The report reiterated the magnitude of the problem, despite the absence of related baseline data.

In its report,[1] the UNODC has identified sedatives as one of the classes of prescription drugs subject to nonmedical use in South Asia. Recent literature has implicated the use of sedatives in incidents of poisoning.[2,3,4] In fact, Maharashtra State in India had announced a change in the schedule of sedative drugs in 2011, from H to XH, making triplicate prescription compulsory for their sale, meaning that the doctor, chemist, and patient will have to keep one copy each of the prescription with them.[5]

A glimpse at community studies from developed nations such as the United States for example, reveals sedative use rates of 4.1% to 56.8%.[6,7,8] However, the problem of nonmedical sedative use in developing countries needs to be viewed keeping various other contextual factors in mind, such as changing lifestyles, lack of access to quality health care, and poor legislation, all of which impact nonmedical use of prescription drugs, which is already rampant.

Against this background, an urban community survey on nonmedical use of prescription drugs was carried out using a mall-intercept approach in Bengaluru, South India. The current report presents some information on the nonmedical use of sedatives from this study. One reason for including sedatives in the present survey was that they are potentially dangerous drugs when used inappropriately. Sedative compounds interact with gamma amino butyric acid receptors in the brain, thereby inhibiting neuronal activity. Using sedatives in increased amounts can potentiate their effects on the central nervous system, and can result in life-threatening effects such as respiratory depression and apnea.[9] Although nonmedical sedative use is associated with potentially fatal effects, empirical data on the patterns of this behavior is lacking in developing countries.

Thus, another important reason for including sedatives in the survey was that today, nonmedical use of sedatives is an ongoing problem in India, and yet this is a statement that is based more on anecdotal information, than recent empirical data. Despite legislative regulation (under Schedule H of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940), reports on the use of sedatives have continued to appear in newspapers and internet.[10,11,12] There also seems to be a mistaken notion among the public that these medicines “used for sleeping or to calm mind” may not be very dangerous, a notion that can especially be true for benzodiazepines like alprazolam (marketed as Restyl, Trika in India). However, the limited empirical data on nonmedical sedative use in India comes from surveys undertaken on drug use in general more than a decade ago,[13,14] with no detailed information focusing on the nonmedical use of sedatives.

The present analysis explores the use of sedatives nonmedically in urban Bengaluru, using a mall-intercept approach. This information, although preliminary, provides recent empirical data (past 12-month), which can help to renew the discussion on the continuing problem of nonmedical sedative use, and aid in developing preventive strategies and raising public awareness about the potential risks associated with such use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

Data were collected as part of the parent study on nonmedical prescription drug use in Bengaluru. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. Participants were recruited using a mall-intercept approach,[15] wherein they were intercepted in five randomly selected shopping malls in Bengaluru (one each from the East, West, North, South, and Central Zones), explained that a research study on prescription drug use is being conducted, and asked if they might consider participating. For those who responded positively, initial screening was done to ascertain if: (a) They were aged between 18 and 40 years; (b) currently residing in Bengaluru. Eligible respondents were explained about the study in more detail; those who consented to participate further were administered written informed consent. At the end of the interview, respondents were offered a gift coupon for Rs. 200 (5 USD) for the redemption in the mall where the data was collected, as compensation for their time. They were also given a pamphlet (in English/regional language) containing health information about the dangers of nonmedical prescription drug use.

All interviews were carried out by two project staff with graduate-level education who were trained on the study protocols. They were then observed during the 1st week when administering the interview to respondents in the mall. Subsequently, the first author observed at least 10% of the interviews every month, and provided regular feedback to the staff to ensure consistency and quality of the data obtained.

With regard to sample size calculation, based on anecdotal information,[16] with an expected percentage of prevalence of about 20% of prescription drugs use in the study population, the sample size was estimated to be 683, with 95% confidence interval of 6% target width.[17] Accordingly, the sample size for the present study was fixed at 700.

Nonmedical use of sedatives in the past 12-month

Past 12-month nonmedical sedative use was assessed by asking respondents: (a) In the last 365 days, did you use sleeping pills/sedatives in ways other than as prescribed (e.g. using more number/longer duration than indicated? (b) In the last 365 days, did you use any of these sleeping pills/sedatives that were not prescribed? Different sedatives (including popular brand names), were read out to the respondents, to enable recall of past 12-month use. Accordingly, two mutually exclusive categories of nonmedical use were identified: (i) Use of sedatives “in ways other than prescribed” (ii) use of sedatives “when not prescribed.”

Measures

Information was obtained using an instrument adapted from the Washington University Risk Behavior Assessment for Prescription Drugs, and the Substance Abuse Module for Prescription Drugs. Both instruments have good test-retest reliability.[18,19] In this study, the adapted instrument was content-validated by faculty members at National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences experienced in treating patients with substance use disorders. The instrument was also translated into regional language and back-translated using standard procedures. It was then beta-tested on 15 individuals shopping in a local super market (not included in the main study), before being used for the main study.

Data analysis

Chi-square/t-test was used to compare past 12-month nonmedical users and nonusers, by baseline variables. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify correlates of past 12-month nonmedical sedative use. All variables that showed a significant level of P < 0.10 in univariate analysis were included (educational level, marital status) along with other relevant variables (age, gender, employment status). These variables were selected based on prior literature suggesting their association with nonmedical prescription medication use.[20,21] Analyses were conducted using SAS© version 9.2.

RESULTS

Description of the sample

Mean age of the participants (n = 717) was 28.0 years (standard deviation [SD]: 5.0). Forty-nine percent was female, 70% had graduate-level education or above, 62% was married, and participants reported mean monthly income of Rs. 42,306.0 (equivalent to 660 USD)(SD: 35,604.0). Two-percent reported suffering accident/injury in the past, 9% reported receiving a prescription for sedatives prior to last 12 months (reasons for a consulting doctor being “for sleep/pain relief/stress relief).” None reported receiving treatment for any medical problem in the past 12 months.

Past 12-month nonmedical use of sedatives

Past 12-month nonmedical sedative use was reported by 88 (12%) respondents, with the majority of these (n = 64; 73%) reporting “use in ways other than as prescribed” (using for longer duration or quantity/haphazard use [skipping doses/stopping abruptly and restarting]). The remaining 24 respondents (27%) reported past 12-month use of sedatives “without prescription.” All the “nonprescribed users” reported that they had used the sedatives haphazardly, meaning they had used them, stopped for a while, started again, etc. Mean age at onset of nonmedical use was 27.0 years (SD: 5.0).

Three (3%) out of the 88 nonmedical sedative users reported that they had used sedatives and alcohol together in the same use episode in the past 12 months. No specific reason was cited for this (“simply/I had a bottle with me, so I used”).

Source of obtaining

“Chemist shops” were the source of obtaining the sedatives in 100% of past 12-month users who had used the sedative “in ways other than prescribed.” Only three of these respondents reported that the pharmacy attendant questioned them, however, they stated that he dispensed the sedative when told “doctor said I can continue same medicine if needed/if I cannot sleep.” These respondents further said that “we know him (the pharmacy attendant) well, he will give us the medicine.”

Among those who reported using sedatives “without prescription,” family/friends were the major source of obtaining the drugs.

Reasons cited for nonmedical use

“Unable to sleep” was the most commonly cited reason for using sedatives nonmedically (60%), followed by “stress relief” (15%). Other cited reasons included “relief from pain, work pressure.” Individuals reporting haphazard use said “they had forgotten to use as prescribed, hence they stopped/skipped/restarted whenever they remembered.” Further details of reasons for nonmedical use among those who used “in ways other than as prescribed” and among “nonprescribed users” are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Patterns of past 12-month use of sedatives “in ways other than as prescribed” (n=717)

Table 2.

Patterns of past 12-month use of sedatives “without prescription” (n=717)

Correlates of past-12-month nonmedical use of sedatives

Bivariate and multivariate associations between sociodemographics and nonmedical use showed that those with graduate-level education or above, and those who were married, were significantly more likely to report past 12-month nonmedical use of sedatives [Tables 3 and 4].

Table 3.

Comparison of past 12-month nonmedical sedative users with those who did not report use, by demographics (n=717)

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression predicting past 12-month nonmedical use of sedatives (n=717)

DISCUSSION

This is the first known study to provide information regarding the various patterns of nonmedical sedative use in an Indian population. The study provides recent data (past 12-month) on nonmedical sedative use in an urban community sample (n = 717) recruited through mall-intercept approach. It is sobering to note that 12% of the sample reported nonmedical sedative use in the past 12 months, considering that the sample comprised of young, apparently healthy individuals shopping in malls. Majority reported use “in ways other than as prescribed,” as opposed to “use without a prescription.”

It is also important to note that 89% of those who had prior prescription for sedatives (57 out of 66 respondents) had used the sedative “for longer duration/higher quantity than prescribed” in the last 12-month [Table 1]. It thus appears that the presence of a prescription was important in contributing to the nonmedical use of sedatives, possibly due to increased opportunity to procure the sedative. Equally important to note is that the prescription, albeit an outdated one, seemed to be an easier route to obtain the sedatives from a legal source – the pharmacy outlets – and that the pharmacy attendants either did not question, or seemed satisfied when the customers, who are presumably “well known to them,” said that “the doctor told them to continue the same medicine if required.” On the other hand, those who reported using sedatives “without prescription” did not approach pharmacy stores, but obtained the sedative from family/friends (who did not have a prescription as well). This finding indicates that information about, as well as the sedatives themselves, seem to have been passed around loosely among friends and family members who had also used them without a prescription.

The above findings are similar to a prior report by the first author, comparing heavy users and less heavy users of sedatives in an urban community sample in St. Louis, USA.[8] The study had shown that heavy users of sedatives were significantly more likely to report “using in ways other than as prescribed,” compared to “use without a prescription.” Other studies have also emphasized the misuse of prescribed sedatives.[22,23] Furthermore, literature from other countries also alludes to inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions,[24] and insufficient advice provided to individuals who are prescribed benzodiazepines.[25]

Another important finding from the present report was the “reasons” cited by the respondents for using sedatives nonmedically (“to sleep, stress relief, work pressures, pain relief [headache, backache”]). Similar findings were reported in St. Louis, USA, where motives such as “stress relief, for sleep, to change the mood or be happy, to get high,” were reported by more than 60% of the sample of nonmedical sedative users.[8] This was further reiterated by other authors describing the misuse of benzodiazepines for their therapeutic indication such as relief from anxiety.[26] It thus appears that despite the vast differences in culture and value systems between a developing country like India and an advanced nation like the US, the findings point to some commonalities in terms of nonmedical sedative use, notably the presence of a prescription, and specific reasons cited for using nonmedically. The findings of the present report thus have several important implications for the field.

Firstly, they inform practicing physicians to exercise caution when prescribing sedatives [9% of the present sample had received prior prescription for sedatives, issued by general physicians in private hospitals Table 1]. Local experts in addiction psychiatry caution that majority of treatment-seekers for prescription drug use are first exposed to the substance in question when it is prescribed to them for a genuine medical condition.[1] Because of the potential risk for dependence with the use of sedatives,[27] it is also important to review the patient's past use of medicines, both sedatives, as well as other prescription drugs.

Two points need special mention in the context of providing health information to patients. One, individuals reporting nonmedical sedative use may also use them in a haphazard manner, and be unaware of the potential harmful effects that can occur with such use (e.g. withdrawal seizures). Haphazard use had occurred in the present sample as well: Eleven percent of those who had used “in ways other than prescribed,” and 100% of those who used “without prescription,” reported haphazard use. Next, simultaneous use of sedatives with other drugs can also occur in individuals who use sedatives nonmedically, either intentionally or by chance, which can result in serious interactions between the two drugs. Although the numbers are very small in this sample, it is still worth noting that these behaviors can occur, and larger samples might reveal further information. At this point, it would suffice to say that doctors need to include information about haphazard use, and simultaneous use of sedatives and alcohol/other drugs, when they educate patients about the potential hazards of nonmedical sedative use.

Secondly, pharmacist/pharmacist attendant practices need to be addressed. In India, pharmacy attendants generally refuse to dispense sedative agents without prescription. But in the present study, it appears that the pharmacists/attendants had relaxed the norms and dispensed them if there was an initial prescription. Pharmacist training and sensitization regarding the rational use of sedatives is thus important, accompanied by strict disciplinary action by the Drug Controller in cases of irresponsible dispensing.

Thirdly, the present findings indicate the need for mental health professionals to address the reasons cited by the respondents for using sedatives nonmedically (“to sleep, for stress relief, pain relief” – in the present report). Such reasons need further exploration as they can reflect work pressures/fatigue, or underlying emotional issues, especially in the light of the fact that these reasons were expressed by healthy shoppers who had no major health problem in the past (except for accident/injury reported by 2%). In that context, interventions provided by mental health professionals would essentially focus on providing individuals with required health information, and helping them to weigh the pros and cons of using/not using prescription medicines, and choose safer alternatives to deal with life problems. Such strategies should essentially be integrated with health information regarding the dangers of misusing licit and illicit drugs, including prescription drugs. In the long run, these measures can foster adaptive coping and prevent habitual “pill-popping” behaviors or tendencies to look for quick fixes/solutions to problems.

Fourthly, public awareness should be raised using media which have the potential for reaching out to a large number of people (such as television, documentaries). A pragmatic measure would be to integrate this education with health information provided about the ill effects of alcohol/tobacco. This is important because, although the television and other media in developing countries are attempting to convey health warnings about the harmful effects of alcohol/tobacco, there is practically no message provided about the dangers of using pharmaceutical products indiscriminately.

More importantly, in terms of raising awareness, mental health care professionals have a unique role to play. For instance, at mental health care centers, when they impart psychoeducation to those who have an alcohol/illicit drug use problem, they need to incorporate the dangers of nonmedical prescription drug use into this education. At the community level, mental health professionals can play a major role in sensitizing doctors serving at peripheral health centers about providing information to patients/families regarding the dangers of using prescription drugs nonmedically, as well as imparting this information in local social institutions such as schools, colleges, women's clubs, and so on.

The study also found that past 12-month nonmedical sedative use was significantly associated with graduation-level education or above, and being married. Associations between nonmedical use of sedatives and various demographic variables have been found in the literature from the West such as gender, education, income.[28,29] Baseline data on demographic trends among nonmedical sedative users is lacking in India, however, these were noticed in the present sample, and need to be clarified further in expanded samples, in view of the scanty literature available on prescription drug use and its correlates in general.

The findings of the study need to be interpreted with caution since the study involves cross-sectional data, and does not support the inferring of any causal relationships. Furthermore, the sample was restricted to individuals who were largely between 18 and 33 years who were mall goers, and were educated and relatively affluent, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, this is the first known analysis focusing exclusively on the nonmedical use of sedatives in a young, healthy, urban community sample. This is in contrast to a recent report of anxiolytic use from Pakistan among patients attending an outpatient clinic, where 36% reported using benzodiazepines, majority of them suffering from cardiovascular problems.[30]

There is a pressing need to explore nonmedical sedative use as well as other prescription medicines in this part of the world – something that needs to be done systematically, with the aim of understanding all associated problems inextricably linked to prescription drug use. For instance, what is the legitimate requirement for sedatives in this country? On what basis are prescriptions for benzodiazepines issued [majority of nonmedical sedative users in this report had obtained a legitimate prescription from private practitioners, the primary reason for consultation being “not being able to sleep” Table 1]. The present data is preliminary, but is recent, and found that 12% of healthy, young shoppers reported using sedatives nonmedically in the past 12-month. The data can thus be a preliminary step for a larger epidemiologic study exploring the various facets of nonmedical sedative use, and prescription drug use.

Finally, a note is made that the present study attempted to provide this recent data using a mall-intercept approach. This venue-based recruitment employed in other countries for gathering information on matters of public health,[31,32] has not been reported so far for community studies in India. Despite some inconveniences faced (e.g. obtaining permission, lack of space/privacy for administering the interview), it is felt that this approach is worth exploring in future research for obtaining health-related information from the public.

CONCLUSION

The present study has provided some recent data regarding the nonmedical use of sedatives in an urban metropolis, which can aid the development of preventive efforts to curtail the same.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The study is funded by Fogarty International Center, USA (Advanced In-Country Research Grant No. TW05811-08; PI: Linda B. Cottler)

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) New Delhi: UNODC; 2002. [Last accessed on 2014 June 15]. Misuse of prescription drugs: A South Asia Perspective [monograph on the internet] Available from: http://www.unodc.org/documents/southasia//reports/Misuse_of_Prescription_Drugs_-_A_South_Asia_Perspective_UNODC_2011.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramesha KN, Rao KB, Kumar GS. Pattern and outcome of acute poisoning cases in a tertiary care hospital in Karnataka, India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2009;13:152–5. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.58541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anthony L, Kulkarni C. Patterns of poisoning and drug overdosage and their outcome among in-patients admitted to the emergency medicine department of a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2012;16:130–5. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.102070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raizada A, Kalra OP, Khaira A, Yadav A. Profile of hospital admissions following acute poisoning from a major teaching hospital in North India. Trop Doct. 2012;42:70–3. doi: 10.1258/td.2011.110398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DNA e-paper. [Last accessed on 2011 Apr 23]. Available from: http://www.dnaindia.com/mumbai/1535150/report-maharashtra-announces-measures-to-curb-sedative-misuse .

- 6.Huang B, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Ruan WJ, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of nonmedical prescription drug use and drug use disorders in the United States: Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1062–73. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCabe SE, Cranford JA, West BT. Trends in prescription drug abuse and dependence, co-occurrence with other substance use disorders, and treatment utilization: Results from two national surveys. Addict Behav. 2008;33:1297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nattala P, Leung KS, Abdallah AB, Cottler LB. Heavy use versus less heavy use of sedatives among non-medical sedative users: Characteristics and correlates. Addict Behav. 2011;36:103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caplan JP, Epstein LA, Quinn DK, Stevens JR, Stern TA. Neuropsychiatric effects of prescription drug abuse. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17:363–80. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.India Today. [Last accessed on 2008 Apr 24]. Available from: http://www.menshealth.intoday.in/story/Are-you-your-own-doc/0/373.html .

- 11.Times of India. [Last accessed on 2012 Dec 12]. Available from: http://www.articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2012-12-2/visakhapatnam/35772938_1_drug-users-drug-overdose-ketamine .

- 12.George NC. Prescription drugs sold over the counter. Deccan Herald News. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 07]. Available from: http://www.deccanherald.com/content/179505/prescription-drugs-sold-over-counter.htm .

- 13.Kumar MS. New Delhi: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Regional Office for South Asia (ROSA); 2001. Rapid Assessment Survey of Drug Abuse in India. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srivastava A, Pal HR, Dwivedi SN, Pandey A. National Household Survey of Drug Abuse in India. Report Submitted to the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India, and the United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Remafedi G, Jurek AM, Oakes JM. Sexual identity and tobacco use in a venue-based sample of adolescents and young adults. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(6 Suppl):S463–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NDTV Report. Abuse of prescription drugs on the rise. [Last accessed on 2014 June 15]. Available from: http://www.doctor.ndtv.com/storypage/ndtv/id/4179/type/news/Abuse_of_prescription_drugs_on_the_rise.html .

- 17.Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: Comparison of seven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17:857–72. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::aid-sim777>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leung KS, Ben Abdallah A, Copeland J, Cottler LB. Modifiable risk factors of ecstasy use: Risk perception, current dependence, perceived control, and depression. Addict Behav. 2010;35:201–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shacham E, Cottler LB. Sexual behaviors among club drug users: Prevalence and reliability. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39:1331–41. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9539-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dineshkumar B, Raghuram TC, Radhaiah G, Krishnaswamy K. Profile of drug use in urban and rural India. Pharmacoeconomics. 1995;7:332–46. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199507040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma R, Verma U, Sharma CL, Kapoor B. Self-medication among urban population of Jammu city. Indian J Pharmacol. 2005;37:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon GE, Ludman EJ. Outcome of new benzodiazepine prescriptions to older adults in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:374–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kokkevi A, Fotiou A, Arapaki A, Richardson C. Prevalence, patterns, and correlates of tranquilizer and sedative use among European adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:584–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashton H. The diagnosis and management of benzodiazepine dependence. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005;18:249–55. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000165594.60434.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhahan PS, Mir R. The benzodiazepine problem in primary care: The seriousness and solutions. Qual Prim Care. 2005;13:221–4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fatséas M, Lavie E, Denis C, Auriacombe M. Self-perceived motivation for benzodiazepine use and behavior related to benzodiazepine use among opiate-dependent patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37:407–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de las Cuevas C, Sanz E, de la Fuente J. Benzodiazepines: More “behavioural” addiction than dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;167:297–303. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodwin RD, Hasin DS. Sedative use and misuse in the United States. Addiction. 2002;97:555–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kassam A, Patten SB. Hypnotic use in a population-based sample of over thirty-five thousand interviewed Canadians. Popul Health Metr. 2006;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel MJ, Ahmer S, Khan F, Qureshi AW, Shehzad MF, Muzaffar S. Benzodiazepine use in medical out-patient clinics: A study from a developing country. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63:717–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC. HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:442–7. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cottler LB, Striley CW, Lasopa SO. Assessing prescription stimulant use, misuse, and diversion among youth 10-18 years of age. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26:511–9. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283642cb6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]